| HRW Documents on Saudi Arabia | FREE Join the HRW Mailing List |

|

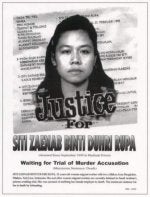

The Case of Siti Zaenab binti Duhri Rupa |

CIMW told Human Rights Watch that it was informed by the Indonesian foreign ministry that Siti Zaenab was accompanied only by an Indonesian translator for a trial before a three-judge court in May 2000. He was a post-graduate student in Medina and this reportedly was his first interpreting assignment. The court sentenced Siti Zaenab to death, although it remains unclear if this was her first trial or an appearance before a higher tribunal. The Saudi foreign ministry informed Indonesian consular officials on July 18, 2000 that their scheduled visit to the prisoner the next day had been postponed, with no reasons provided. Possibly fearing yet another secret execution of an Indonesian citizen, three Indonesian consular officials remained in Medina from July 19-21, monitoring the site near a mosque where beheadings were said to be carried out on Thursdays and Fridays. <1> According to CIMW, Siti Zaenab's family received a letter from the Indonesian government, dated August 3, 2000, informing them that her execution had been postponed as a result of a personal conversation between King Fahd and Indonesia's then-president Abdurrahman Wahid. Since that time, CIMW and the family have been unsuccessful in their repeated and copiously documented efforts to secure additional information about the case or a visa to Saudi Arabia to visit Siti Zaenab in Medina prison and obtain first-hand information from her. At a meeting with Mohamed Ibrahim al-Utaibi of the Saudi embassy in Jakarta on January 18, 2001, CIMW was informed that the embassy could not grant a visa to the organization and Siti Zaenab's family because of "regulations," which he declined to identify. Mr. Utaibi added that the embassy was not aware of Siti Zaenab's case and could only grant a visa with the permission of the kingdom's foreign affairs ministry. Saudi authorities have made little information publicly available about the trial other than to state that Siti Zaenab confessed to the killing. On March 29, 2001, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, Asma Jahangir, sent an urgent appeal to the government of Saudi Arabia about the case, noting that she reportedly was tried without any legal assistance and that the former Indonesian ambassador nor his lawyer were allowed to visit her in detention. The Special Rapporteur received a reply from the Saudi government on November 20, 2001, the contents of which she summarized as follows: "[O]n 11 September 2000, [Siti Zaenab] was sentenced to death for murdering her employer after a trial during which she expressly confessed to the murder. It was brought to the Special Rapporteur's attention that the sentence had not been carried out, pending attainment of the age of majority by the murdered woman's eldest child so that it could be ascertained whether the heir wished to accept a stipulated financial compensation, pardon the offender or demand enforcement of the death penalty. The Government pointed out that the judicial authorities would endeavor to persuade the child to accept the financial compensation, in which case the State or charitable associations would help to provide the requisite sum. It was further reported that the judiciary is bound by any legal settlement reached, i.e. if the victim's heirs relinquish their right to retribution either before or after the judgment, the accused is reportedly not liable to the death penalty." <2> <1>In June 2000, Warni Samiran Audi, another Indonesian domestic worker, was executed for allegedly killing the wife of her Saudi employer. The Indonesian embassy in Riyadh was not officially notified of the execution, according to Din Syamsuddin, then-director general for labor in the Manpower Ministry, although Indonesian officials had followed Warni's case for three years, seeking her release or a reduced sentence. The secret execution drew criticism from Indonesian government officials and caused an uproar among Indonesian nongovernmental organizations. <2> United Nations Economic and Social Council, Commission on Human Rights, 58th session, Agenda item 11(b), Civil and Political Rights, Including Questions of: Disappearances and Summary Executions, Report of the Special Rapporteur, Ms. Asma Jahangir, submitted pursuant to Commission resolution 2001/45, Addendum, May 8, 2002, E/CN.4/2002/74/add.2, Paragraph 537. |