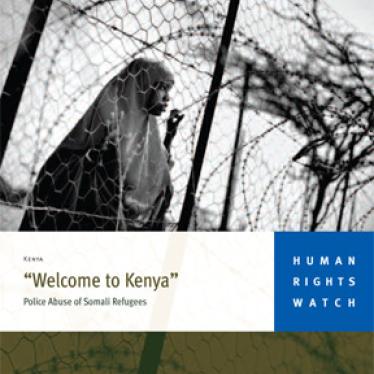

Shot at and raped. Arrested and beaten. Detained and deported. Extorted and robbed. Threatened and insulted. Ignored and shunned. The treatment of hardened criminals in some far-flung police state? The fate of political opponents by a repressive regime? Not quite. For Somali refugees - 80% of them women and children - this is their welcome to Kenya.

Kenya's welcoming committee for Somali refugees is a notoriously corrupt and abusive police force. For many of the newly arrived Somali refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch in the Dadaab refugee camps, "Karibuni Kenya" - "Welcome to Kenya" - sounds like this:

"Four [officers] beat and raped us. They kicked me in the stomach, back and head and held me in a choke position."

"For 10 minutes, the [officers] punched him in the head, kicked him and whipped him with a nyunyo [a thin rubber whip]. He lost consciousness."

"They pushed me into the cell full of people. I fell and people forced in behind me stepped on my back. A month later, I gave birth to a stillborn baby."

"They did not allow us to go to the toilet, so we used a corner of the cell where faeces and urine just piled up right next to where people had to sit all night long. Some of us vomited because of the stench."

"Four policemen stopped us [near the border] and said, 'Give us money or we will send you back.'"

These are fragments of a few stories, a reflection of what happens to some of the thousands of Somali asylum seekers intercepted by Kenyan police as they try to reach the Dadaab refugee camps, about 100km from Kenya's officially closed border.

As they cross, Somalis encounter the police, who demand money. Those who cannot pay - women with babies, children, entire families - face deportation, violent abuse, arbitrary arrest, unlawful detention in inhuman and degrading conditions, and wrongful prosecution for their "unlawful presence" in Kenya.

The police claim they are protecting Kenya from terrorists and enforcing immigration laws. But the fact that they extort Somalis to pay their way through checkpoints and out of police custody suggests they are more concerned with lining their pockets.

Once the refugees are in the camps - which sheltering almost 300,000 refugees instead of the 90,000 for which they were built - it is virtually impossible for them to leave, even temporarily. Inside, refugees face further police abuse and sexual violence by other refugees and local Kenyans, which the police fail to address. One woman told Human Rights Watch: "The police arrested one of the men [who tried to rape me, but] he paid money and was released. He told me: 'I have paid money and now I am a free man. Kenya is money.'"

To its credit, Kenya has provided asylum to refugees fleeing war-torn Somalia for almost two decades. No one doubts the weight of the burden. So far, 320,000 Somalis have registered as refugees in the country and the total is probably well in excess of half a million, as many don't register. Why, then, is Kenya - long considered a proper refugee host country - sinking so low in the international refugee protection ratings?

The country's three-year-old border closure and the related closure of a refugee transit centre at Liboi has forced asylum seekers to use smugglers to cross the border. The clandestine nature of their journey allows police to accuse the refugees of entering the country illegally or of being "terrorists" en route to Nairobi, and extorting money from them. Even with the border closed, both international and Kenyan law prohibit Kenya from blocking refugees who try to enter the country and guarantees their right to travel to the camps for screening and registration.

Kenya closed the border as a security measure, but, faced with the fact that hundreds of thousands of Somalis have crossed the border in the past three years, officials admit the policy has failed.

So what needs to be done? Opening a new refugee screening centre in Liboi is the most urgent and obvious step towards curbing the activities of corrupt police. An order to the police to respect and help - not attack - new arrivals should come next, closely followed by broader police reforms to shift a police culture that condones such abuses of power, both inside and outside the camps.

Finally, the authorities need to show far greater flexibility in allowing refugees to move freely in and out of the grossly overcrowded Dadaab refugee camps.