Detained Without Trial

Abuse of Internal Security Act Detainees in Malaysia

I. Summary

On December 9, 2004, . . . I stepped out of my cell without violating any orders. I was handcuffed in the front, my head was forced to bow as low as waist-length, and then I was hauled towards the back of the [cell block]. I was beaten, spat on, and kicked several times. After reaching the back of [that block], I was ordered to sit facing the wall, while handcuffed, and my head was pushed down. There I was insulted, continuously kicked from behind and clubbed on the head with a baton. . . .

We were then taken to [another cell block]. On the way from [a cell block] to [another block] I was handcuffed with my hands at the back and my head was pushed down to waist level. My head was struck with a baton and my eye was hit, injuring it. When I reached room seven of [the cell block], I was continuously beaten and then forced to strip naked, ordered to crawl while entering the room and then my buttocks were kicked and that was how I stumbled inside, naked. My t-shirt and pants were outside the room, which were returned to me later by [the] warden. . . . My left eye continuously bled. I only received eye wash treatment on Sunday, December 12, 2004.

-Statement of Mohamad Faiq bin Hafidh describing events on December 9, 2004, in KamuntingDetentionCenter.

Held without charge or trial under Malaysia's draconian Internal Security Act (ISA), Mohamad Faiq bin Hafidh is one of more than twenty-five detainees beaten by prison guards in KamuntingDetentionCenter on December 8 and 9, 2004. The beatings occurred after detainees in one cell block resisted the unannounced search of their cells on the morning of December 8, and extended to detainees in cell blocks that did not resist the inspection. The spot check was part of an effort by the new director of Kamunting, where most ISA detainees are held, to impose a more rigid disciplinary regime on the detainees.

The government later stated that the search uncovered foldable knives, scissors, metal rods, and badminton rackets turned into weapons and suggested that force was necessary to overcome violent and threatening detainees. According to Deputy Minister of Internal Security Datuk Noh Omar, eight prison guards on December 8 suffered injuries as well. After the detainees were subdued, the guards attacked them in that cell block and, the next day, in other cell blocks. Detainees acknowledge that some detainees resisted the spot checks on December 8, but say that the violence on December 9 was initiated by the guards. They claim that they had no weapons and that the items listed by the government were for handicraft work and all had been approved for possession by detainees.

Eyewitness accounts from the detainees-presented here for the first time-describe prison guards, armed with batons, shields, and riot gear, beating and abusing handcuffed detainees. The physical abuse allegedly extended to detainees who did not resist the search of their cells. Detainees said they were denied immediate medical assistance, although several suffered broken bones and open wounds. In some cases, prison authorities waited until the bruises had healed before they were provided medical assistance. Some detainees and their wives also described being humiliated.

The mistreatment of Kamunting detainees highlights the legal purgatory in which ISA detainees exist. They are detained and treated as criminals, but without ever being charged or convicted. They are stripped of many rights, but have virtually no recourse to the law or court system to show that they do not belong in detention. As documented by Malaysian and international human rights organizations and Malaysian lawyers, ISA detainees have long suffered physical and mental abuse, sexual humiliation, and public vilification without access to a serious complaint mechanism or having the opportunity to defend themselves. Some ISA detainees have been in detention for over four years without any way of knowing how much longer they will remain in custody.

Under the ISA, the government may hold anyone suspected of threatening national security or a number of other vague categories of proscribed activities without charge or trial. Most of the 112 people detained under the ISA are accused of associating with militant Islamist groups; though the government has expanded its use of the ISA to include individuals accused of counterfeiting and forging documents and has threatened to use it against practitioners of religious beliefs deemed "deviant" by the government's Religious Affairs Department.

The ISA is now forty-five years old. Its provisions violate fundamental international human rights standards, including prohibitions on arbitrary detention, guarantees of the right to due process, and the right to a prompt and impartial trial. It turns the internationally recognized presumption of innocence on its head. The Malaysian government's consistent misuse of the ISA demonstrates how an unchecked executive system of detention becomes a means of oppression.

Since 1960 the Act has been used by the Malaysian government to silence critics and political opponents of the ruling United Malay National Organization (UMNO). More than ten thousand people have been detained under the ISA, including the former Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim. The ISA has repeatedly been criticized by Malaysian human rights groups, the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, Suruhanjaya Hak Asasi Manusia Malaysia (commonly referred to as Suhakam), and international human rights groups. Until recently, foreign governments also criticized the ISA. Even some members of the government have recently advocated for the release of ISA detainees in detention for over two years.

Since September 11, 2001, and in view of the increasing use of the ISA against suspected Islamist militants, some ISA critics, notably the United States, are now silent on the use of the ISA. A cabinet minister told Human Rights Watch that the U.S. no longer criticizes Malaysia's use of the ISA because of U.S. detention practices at GuantnamoBay. Indeed, a senior State Department official, when questioned about the ISA, told Human Rights Watch in December 2003, "With what we're doing in Guantnamo, we're on thin ice to push on this." These sentiments and the U.S. practice of indefinite detention without trial of persons at GuantnamoBay and United Kingdom's Prevention of Terrorism Act of 2005, which allow for preventive detention are touted by government officials as a green light to continue to detain individuals indefinitely without charge.

The government admits that detention under the ISA is preventive and that it either cannot or chooses not to prosecute individuals. In October 2001 former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed said, "To bring these terrorists through normal court procedures would have entailed adducing proper evidence, which would have been difficult to obtain." This sentiment continues in the current government of Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. In July 2005, cabinet minister Datuk Mohamed Nazri told Human Rights Watch, "They [ISA detainees] have not committed any crime because ISA is preventive. You cannot, therefore, go to court."

Human Rights Watch recognizes the obligations of the Malaysian government to protect its population from terrorist attack and to bring those responsible for engaging in such attacks to justice.There are also serious and credible allegations that some of the September 11th hijackers used Malaysia as a transit point and that some of the alleged perpetrators of the bomb attacks in Bali and Jakarta spent considerable time in the country.

But the Malaysian government has yet to demonstrate that any of the individuals it has detained have actually engaged in any illegal activity. Notably, it has not shown that the investigation, arrest, and detention of alleged militants could not be handled through existing law enforcement capabilities and the criminal law, which would protect the rights of the accused. Without these safeguards, the Malaysian government cannot be sure that the men it has captured are in fact dangerous individuals planning to carry out attacks, or whether it has locked up men whose only crime was an interest in a small group of charismatic Muslim clerics.

Prime Minister Badawi has shown no sign of a change in the government's arbitrary and oppressive use of the ISA. The ISA is so widely feared that it is used not only for its stated purposesto fight terrorism and other national security threatsbut to chill speech, to stifle opposition political activity, and to put pressure on disfavored segments of Malaysian society. The government has thus far ignored recommendations from parliamentary and official government advisory groups and civil society to reign in or repeal the ISA. With a forty-five year history of misuse, it is time for the Malaysian government to repeal the ISA. Malaysia is a country with a developed legal and judicial system that no longer needs the crutch of an antiquated preventive detention system. If an individual has committed a crime the criminal law should be used to prosecute current ISA detainees; the others should be released, subject, of course, to ongoing criminal investigation to the extent that the evidence so warrants.

In 2004 Human Rights Watch published a lengthy report on the ISA, In the Name of Security: Counterterrorism and Human Rights Abuses Under Malaysia's Internal Security Act, which documented abuses against ISA detainees and identified ways in which the ISA violated international law.This is a follow-up report, based on statements of current ISA detainees provided to Human Rights Watch, interviews with family members of ISA detainees, lawyers, activists, and government officials.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report in Malaysia in July 2005 and subsequently through email and telephone from New York. We interviewed family members of current ISA detainees, their lawyers, members of SUHAKAM, a cabinet minister, and a member of the opposition Democratic Action Party (DAP). In June and July 2005 Human Rights Watch made official requests to visit KamuntingDetentionCenter, but these requests were refused. A follow-up request in August 2005 to interview the director of Kamunting, Mr. Yasuhimi bin Yusoff, or a government official knowledgeable about the events in December 2004 was unanswered. Consequently, the government's account of the events of December 2004 cited in this report are based on reports in the Malaysian press.

The statements by current ISA detainees, cited in this report and made public for the first time, were provided by the detainees' lawyer to Human Rights Watch. The statements were written soon after the events of December 8 and 9, 2004, and were given to the detainees' lawyer in June 2005. While we were unable to check these statements against government accounts for the above mentioned reasons, and while the statements are potentially self-serving in important respects, they closely overlap in description of many particulars. The wives of the detainees, who visited their husbands, shortly after the events of December 8 and 9, 2004, also gave similar accounts of what happened to their husbands in December 2004.

II. Background

The ISA was originally enacted by British colonial authorities in 1960 during a national state of emergency as a temporary measure to fight a communist rebellion. The ISA allows the police to detain any person for up to sixty days, without warrant or trial and without access to legal counsel, on suspicion that "he has acted or is about to act or is likely to act in any manner prejudicial to the security of Malaysia or any part thereof or to maintenance of essential services therein or to the economic life thereof."[1] After sixty days, the minister of internal security (formerly the minister of home affairs) a post currently held by the prime minister, can extend the period of detention without trial for up to two years, without submitting any evidence for review by the courts.[2] Such two-year detention orders are renewable indefinitely.While the ISA does allow for review of all detentions by a nominally independent Advisory Board, the recommendations of the board are non-binding. The Advisory Board is appointed by the Malaysian King on the advice of the prime minister, and its suggestions on individual cases are frequently ignored.[3]

Reports of torture and ill-treatment during the first sixty days of detention in Police Remand Centers (PRC) (pretrial detention centers) have been documented by the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, and Malaysian and international human rights groups.[4]In 2004, Human Rights Watch published In the Name of Security: Counterterrorism and Human Rights Abuses Under Malaysia's Internal Security Act, which documented the near-complete denial of due process rights to detainees in the first several weeks of detention, as well as physical and psychological abuse of ISA detainees who allegedly belong to Islamist militant groups. Attention to ISA abuses, coupled with the growing international revulsion against the abusive practices of U.S. forces at Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison, spurred the Malaysian government to respond. On May 29, 2004, it opened KamuntingDetentionCenter to the first tour by journalists since it opened in 1973. Although journalists were not allowed to speak to detainees directly, the media did report on the fact that detainees had told the Deputy Minister of Internal Security Datuk Noh Omar that they had been abused during the first few weeks of their detention in Police Remand Centers by Special Branch interrogators.[5] Under pressure, the government then announced that Suhakam could investigate these claims. In July 2004, Suhakam commissioners, accompanied by investigating officers from police headquarters visited a Police Remand Center in Kuala Lumpur, and were told by police officers that they do not torture ISA detainees.[6]

Allegations of torture and ill-treatment in Police Remand Centers were, however, acknowledged by the government-appointed Royal Commission to Enhance the Operation and Management of the Royal Malaysia Police.[7]The Commission expressed "concern" at the "sheer number" of complaints it received by detainees in police custody, including ISA detainees, alleging torture, inhuman, and degrading treatment by the police and Special Branch interrogators.[8]It recommended the police adopt a code of practice relating to the arrest and detention of persons, including under preventive detention laws, and recommended amending the Police Act to define the powers and activities of the Special Branch.[9] The Commission also recommended reducing the initial period of detention under the ISA from sixty to thirty days.[10] Shortening the period of initial detention, however, falls far short of the amendments necessary to conform with international standards of due process rights for detainees-including the right to challenge the legality of their detention. The Commission's findings and 125 recommendations, which at this writing were being reviewed by the government, were made public in May 2005; though it has thus far refused to place it on a government website free of charge making the report all but inaccessible to the Malaysian public.

ISA detainees continue to be subject to arbitrary detention, physical abuse, and ill-treatment, and without any effective judicial review on the merits of their detention. Despite a greater openness in his administration and willingness to engage with Malaysian rights advocates, there is no sign that Prime Minister Badawi intends to repeal the ISA and end its forty-five year history of abuse.

III. Current Detainees

As of September 2005, the Malaysian government holds 112 detainees under the ISA. Sixty-five of them are alleged members of Jemmah Islamiyah (JI), a militant group purportedly seeking to create an Islamic state encompassing Malaysia, Indonesia, and parts of the southern Philippines.[11] Nine are alleged members of Kumpulan Militia Malaysia (KMM or Malaysian Militant Group), which according to the Malaysian authorities wants to overthrow the government and set up an Islamic state.[12] Twenty-two are detained for counterfeiting currency and thirteen for document falsification.[13] One detainee allegedly worked with Pakistani scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan to sell nuclear secrets.[14]Two of the ISA detainees are women. One of them is Norawizah Lee Abdullah-the wife of Riduan Isamuddin, also known as Hambali, an alleged leader of JI and currently in U.S. custody at an unknown location. According to a lawyer for some of the ISA detainees, Norawizah Lee Abdullah is being detained because of her relationship with her husband.[15]

None of the detainees have been charged. The allegations listed herein have been publicized by the Malaysian government-none have been proved in any formal judicial proceeding.

In addition to Malaysian citizens, eleven Indonesians, three Singaporeans, two Filipinos, and one Sri Lankan are detained.[16] Most detainees are held in KamuntingDetentionCenter, but an unknown number of detainees, like Hambali's wife, are held in Police Remand Centers.

In 2005 the government threatened to expand the use of the ISA to include diesel fuel smugglers and religious groups whose practice the government deems "deviant."[17] The most recent ISA detentions, of nine persons allegedly involved in identification card fraud, occurred in February. In May the government announced that the ISA will be used against a new militant group, but later retracted the statement that such a group existed.[18]

In June 2005, according to a lawyer for some of the ISA detainees, the government returned three Indonesians to Indonesia. The three had been detained in Sabah, Borneo, in September 2003 for immigration violations and were subsequently detained under the ISA in December 2003 for being alleged members of JI.[19]

In March 2005 the government released six ISA detainees. These included five of the "Karachi 13," Malaysian students studying in Karachi arrested in 2003 for alleged training for future terrorist activities.[20] Their detention was supposed to expire in December 2005. Wan Min Wan Mat, an alleged financier of JI who was detained in September 2002 and whose detention was to expire in October 2006, was also released.[21] The Internal Security Minister no longer considered them a threat to national security and suspended their detention. The six, however, are under a Restricted Residence Order for two years. The students have to report to the local police every Monday and may not leave their homes from 8:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. Wan Min has similar restrictions, but has to report to the police daily.[22] Upon his release, Wan Min thanked the government for detaining him and said, in a widely reported statement, "The ISA is not cruel. It is necessary to tackle underground activities which are difficult to handle under the normal process."[23] It is not clear if this statement was made voluntarily or was the product of mistreatment or coercion. Wan Min has refused to speak to independent organizations or journalists since his release.

According to the government, it releases ISA security detainees after they have undergone "rehabilitation" and are no longer considered a threat to national security. According to Deputy Prime Minister Najib Razak, "They are put under ISA, they are given counseling and if we deem that they are no longer a threat to national security then we will release them. They are being watched very, very carefully."[24]

IV. Physical Abuse and Ill-Treatment of ISA Detainees in KamuntingDetentionCenter

The Malaysian government continues to bar international and Malaysian human rights groups from visiting Kamunting. Consequently, descriptions about conditions in Kamunting come from detainees, their families, detainees' lawyers, who have limited physical access to the facility, and the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, SUHAKAM.

According to the 2003 Suhakam report on conditions of detention under the ISA, most ISA detainees in Kamunting live in dormitory style blocks, which are surrounded by a grassy compound. The detainees are allowed to move within designated areas of the compound.[25]

Detainees accused of similar offenses are housed together. Each cell block is numbered. In 2003, detainees were allowed restricted access to newspapers and books.[26] They were allowed one visit a week from relatives lasting no more than thirty minutes and with no more than two persons at a time. The visiting rooms were divided with wire mesh barriers separating the detainee and the visitor. Visitors were allowed to bring in only fruit for the detainees and a certain number of books per visit.[27]

Suhakamrecommended amendment of the rules to enable detainees to spend more time with their families.[28]Suhakam recommended that detainees should not be physically separated from their families by a wire mesh barrier and that prison officials need not be present during family visits because ISA rules permit authorities to search visitors.[29]

In mid-2004, amid increased scrutiny of the treatment of ISA detainees in PoliceRemandCenters and growing pressure from detainees and their families, conditions in Kamunting were relaxed. Detainees' cell blocks, which normally were open from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m., would instead close at 10:00 p.m.[30] Detainees could visit different cell blocks.[31] Wire mesh partitions in visiting rooms were removed and detainees and their families were allowed physical contact and to visit for more than an hour. Families were also permitted to bring food for their husbands on special occasions. Detainees were also allowed to make handicrafts, which their families sold to the public.[32]

In early December 2004, a new director, Yasuhimi bin Yusoff, was appointed at Kamunting. According to detainees' families, the new director began to limit the detainees' new privileges, which had been negotiated with the previous director. Human Rights Watch recognizes that the inspection of detainee cells and the maintenance of security are legitimate procedures in any detention facility.

The December 2004 Incident at Kamunting

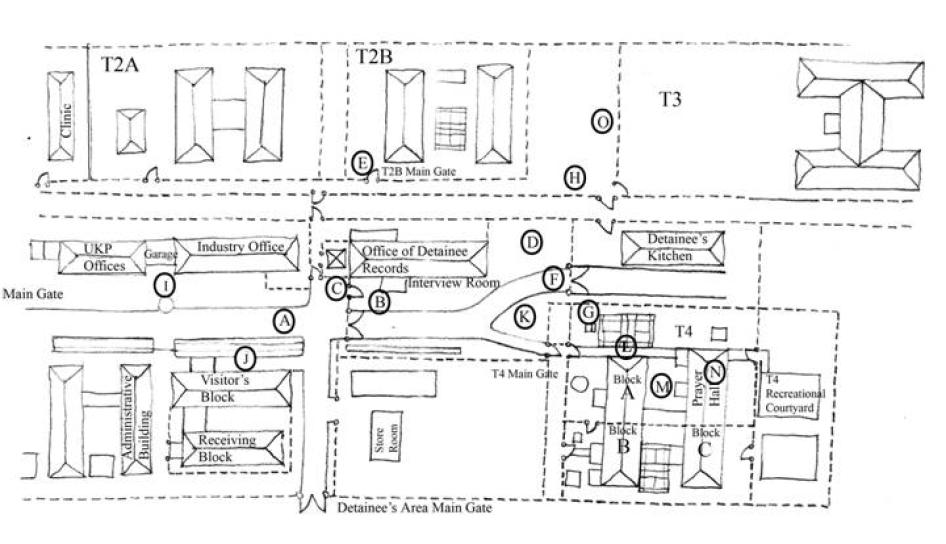

The events of December 8 and 9 involved detainees in cell blocks T2B and T4, which house detainees alleged to be members of Jemmah Islamiyah. (See the following page for a drawing of the facility by an ISA detainee at Kamunting Detention Center; the drawing identifies the location of cell blocks T1, T2, T3, and T4, and marks the locations of events on December 8 and 9, 2004. The map was re-drawn by Human Rights Watch for the purposes of formatting and translation. A copy of the original map in Malay is at Appendix A).

Drawing of KamuntingDetentionCenter by ISA Detainee Identifying

Location of Events (A-O) on December 8 and 9, 2004 (English Translation)

A.Location where handcuffed T2B detainees were beaten.

B.Location of Shukry Omar Talib [ISA detainee] during the beatings.

C.Location where Shukry Omar Talib discussed with Kamunting director after the incident at T2B.

D.Location where Shukry Omar Talib and Zid Sharani [ISA detainee] witnessed the T2B incident.

E.Location of 70+ UKP (Unit Keselmatan Penjara, prison security unit) officers before raid on T2B.

F.Location of Shukry Omar Talib's discussion with Ahmad Yani after Shukry's discussion with the Director.

G.Section of wall that was detached by T4 residents.

H.Chain-link fencing.

I.Federal Reserve Unit (FRU) gathered here.

J.UKP officers resting place after T2B operation.

K.Assembly of FRU & UKP officers before entering T4 on December 8, 2004.

L.Path where T4 detainees were beaten by the UKP and Kamunting officers.

M.Second body search performed here.

N.Block where T4 detainees were handcuffed, forced to sit on the floor, and beaten.

O.Several parts of wall removed to witness T2B incident.

The Raid at Cell Block T2B

On December 8, prison officials conducted an unannounced inspection of cell block T2B, which housed mainly Indonesians, Filipinos, and a few Malaysians. According to eyewitnesses, on December 8 at 9:00 a.m., fifty to sixty guards (Unit Keselmatan Penjara or UKP) (prison security unit) armed with shields, batons, and riot gear entered block T2B.[33] Deputy Internal Security Minister Datuk Noh Omar, as reported in the Malaysian press, claimed that detainees on December 8 tried to prevent spot checks of cells and set off a riot.[34] The minister said that detainees blocked the entrance of T2B and, when officers forced open the gate, threw stones and other objects at them.[35]

Detainees say that, through a hole in the wall separating block T2B and T4, they saw handcuffed detainees beaten by UKP officers as they were brought out from T2B.[36] Ahmed Yani bin Ismail, observing through the hole, later wrote, "I saw Sulaiman Suramin brought out of T2B handcuffed from behind by several UKP officers. He looked weak-limp. He was then followed by other residents of T2B. I saw Zulkifi [Deny Ofresio][37]and Ibrahim [Ibrahim Ali] with their clothes soaked with blood. I also saw a warden punching and kicking Zulkifli when he was taken, handcuffed from behind, by the UKP.[38]

Another detainee wrote, "Not long after the UKP officers stormed inside T2B I saw as many as twelve detainees brought out from T2B in a weak state, bleeding from their heads, their clothes dirtied, and handcuffed from behind."[39]

Mohamad Zamri Sukirman, another eyewitness to the events on December 8, wrote:

On December 8, 2004, around 10:40 a.m., several detainees and I were in the detainees' kitchen area. I was there to see more clearly what was happening to T2B residents with the UKP. I saw T2B residents brought out from their area handcuffed and escorted by two UKP officers. . . . I saw several UKP guards standing in [another block] head towards them. They began kicking and beating them.[40]

The detainees' lawyers, who saw their clients on December 28, told Human Rights Watch of several assaults. Zaini Zakaria, in detention since 2002, from cell block T2B, reportedly was handcuffed and hit on the back of his head with a metal rod by a guard, which resulted in him receiving twenty stitches.[41] Sulaiman Suramin, in detention since 2003, had some of his fingers broken after prison guards stepped on them. Ibrahim Ali, in detention since 2003 and released in July 2005, was beaten, which resulted in him receiving six stitches to his head. Zakaria bin Samad was kicked and beaten as well.[42]

Two other detainees from T2B suffered from broken bones-Abdullah Zaini, an Indonesian, had a broken hand, and Sofian Salih, a Filipino, had a fractured leg.[43]

In total, eight guards and twelve detainees were reportedly injured on December 8. It is difficult to assess the intensity of the fight, because no details regarding the injuries suffered by the guards have been made public. As noted above, Human Rights Watch request to interview Kamunting Detention Center Director Mr. Yasuhimi bin Yusoff or a Malaysian government official knowledgeable about the events of December 2004 was unanswered and requests to visit the detention center were denied.

Datuk Noh Omar announced that during spot check prison officials had found knives, scissors, metal rods, and badminton rackets sharpened into weapons.[44]The guards also allegedly discovered mobile phones, a charger, and a SIM card.[45]The government, as reported in the Malaysian press, claimed that lax security led to the acquisition of these items.[46]The detainees, however, contend that the knives, scissors, and badminton rackets had been approved by Kamunting authorities for use in fashioning arts and crafts or for use in exercise and that they been no reports of these items being misused prior to the confrontation.[47]

The Raid on Cell Block T4

After the raid on cell block T2B, prison personnel informed residents of the T4 cell blocks, which housed Malaysians, that their cells would be inspected on December 8. According to the detainees, they cooperated with the authorities and did not obstruct the inspection.[48] Prison officials seized metal spoons, can openers, scissors, paper cutters, cigarettes, wire, metal ladles, a garden hoe, shaving blades, badminton rackets, and a wooden mop and broom.[49]Detainees and their families contend that prison authorities had approved these items and allowed them to use knives and scissors to make handicrafts-pencil and jewelry cases and tissue boxes-which their families sold to the public.[50] The detainees said that badminton rackets were used by the detainees for recreation and had also been approved by Kamunting officials.[51]

The wives of three detainees beaten on December 9 claim that their husbands were targeted because they had been "vocal" about their rights in detention and had written to their attorneys, NGOs, Suhakam, and the press.[52] Others told Human Rights Watch that their husbands were targeted because they had told their attorneys and the press about torture and ill-treatment in Police Remand Centers, and had made comparisons to mistreatment of detainees in Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison.[53]

On December 9, according to T4 detainees, UKP officers equipped with shields and batons raided their cells for a second time on December 9 at 4:00 p.m. Twenty-three detainees were ordered out of their cells, handcuffed, and instructed to bend down to their waist and walk in a single file to the prayer room. Detainees consistently describe that despite their cooperation they were beaten, kicked, spat on, and verbally abused.

Mohidin bin Shari, detained since December 2002, wrote that even though he cooperated with the UKP, he was beaten:

My block was opened . . . and we were ordered to exit one by one for body searches. I was the first person to exit. . . . At that time I was inspected by as many as five UKP officers . . . one of the UKP officer snarled at me and said, "Don't fight. Follow my orders." I was shocked because I wasn't putting up a fight at all. My hands were then handcuffed as the UKP officer searched my entire body, groped me, and used a metal detector. After searching my body, two UKP officers whose faces I could not see because my head was bowed and I was handcuffed. . . . . They pressed my neck until I felt pain. I said, "Please don't press against my neck because it is painful," but the UKP officers ignored my words.

Throughout the trip towards [another cell block], the UKP that were standing along the path beat me with batons on my head and back. Some also kicked my private parts and punched my head. After reaching the [cell block], they searched my body again. A UKP officer spat in my face. After that, an officer grabbed my hair and said, "What's with this face of yours?"[54]

Abdul Rashid bin Anwarul, detained since January 2002, described how he was treated:

They conducted a body search on me by opening my trousers and inspecting my entire body. Afterwards, they handcuffed my hands and I was ordered to bend down. . . . I could not see in front of me as a result of the pressure they put on my neck and my head was hit hard every time I tried to look in front. . . . My back was hit hard . . . causing me to shout in pain. My buttocks were kicked three times nearly kicking my penis. My head and neck was hit and punched numerous times. My right shoulder was hit with a baton causing swelling in that area. My waist was punched which caused it to swell. I was verbally abused during the journey. My right leg was kicked in the shin.[55]

Ahmed Yani Ismail, detained since December 2001, was kicked, punched, and slapped. He wrote:

Several guards . . . kicked my buttocks eight times, kicked my stomach once, hit the back of my head several times, kicked my back four times, kicked my left thigh once and the area above my knee once. The warden . . . slapped my face in the eye area at least three times. . . . I experienced shortness of breath, nausea for four days, pain in my chest, bruising and pain throughout my body. . . . My mouth bled.[56]

Yazid Sufaat, detained since December 2001, was hit and spat on. He wrote:

One after the other we were handcuffed, hit with batons, spat on, punched, kicked, and trampled on while brought into the prayer hall. I was able to see this because I was the last person who was brought out. . . . I was handcuffed in the back, they spat on me, stepped on my toes, hit my head, and punched my ribs. I was hauled roughly to the prayer hall by one of the prison guards.[57]

Zainun Rasyhid, detained since December 2002, wrote:

I was handcuffed and one of them strongly pinched the nape of my neck from behind until it hurt. . . . I was spat on, hit, and punched in my head time and time again. My legs were kicked from behind. . . . While I was at the back of [a cell block], I was searched again and they pulled at my pants until my pants fell to the ground and I was exposed. In this state they forced me to enter [a cell] by kicking me . . . I was ordered to sit cross-legged with my head close to the wall. . . . Not long after two to three guards came and spat on my head, hit my hand, and kicked my back.[58]

Abdullah bin Mohamed Nor, detained since December 2002, wrote, "My legs were kicked and stepped on while the search was made . . . my back was kicked. . . . The UKP beat my head and body repeatedly with batons and ordered me not to look around . . . I was ordered to sit facing the wall. They pushed my head and it hit the wall. . . . We were treated like animals."[59]

Mat Sah bin Mohamad Satray, detained since April 2002, described his experience:

I was flung hard on the cement floor and they pressed their knees on the back of my neck until I felt immense pain, and until my left check was pressed against the dirty cement floor. I was then pulled back up and pushed roughly into the prayer hall while handcuffed. . . . My right ribs were flung hard on the floor until I felt short of breath and my cheek was on the floor. After that I was ordered to rise and the handcuffs were moved from the back to the front. I was ordered to sit cross-legged facing the wall and my head was hit against the wall.[60]

Some ISA detainees in Kamunting reported being humiliated. "I was forced to strip naked and ordered to crawl while returning to my cell," wrote Mohamad Faiq Hafidh, who has been detained since January 2002.[61] Yazid Sufaat says he was ordered to strip naked in front of guards and saw others similarly mistreated. He wrote, "Because I was one of the first people brought to T1, I could witness how some of my friends were beaten up . . . Abdul Nassir bin Anwarul was stripped naked and ordered to crawl and then was kicked in the buttocks."[62]

Abdul Murad bin Sudin, detained since October 2002, wrote,

I was roughly searched . . . by the wardens who hit and kicked me and finally I was stripped naked. While being stripped naked, I repeatedly begged that my underwear not be removed. After stripping and inspecting me, they ordered me inside the jail cell by crawling; while crawling in a nude state inside the cell, they then kicked me from behind until I fell, sprawled and the gate of the cell was locked.[63]

One detainee's wife told Human Rights Watch that when she visited her husband a few days after the incident she was harassed by Kamunting officials. "The officials showed me some bras and underwear. They claimed they found them in my husband's cell and asked me to identify which ones were mine. I was embarrassed. But this was just another way to humiliate us."[64]

Sixteen detainees from T4B were then locked inside two blocks for four days until December 13, 2004, and were given insufficient drinking water, no change of clothes, and no reading material except for a copy of the Quran.[65]

International law widely prohibits torture and all cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.States are obliged to investigate all credible reports of torture and inhuman treatment. Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights prohibits torture and other forms of mistreatment.[66]The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (the Convention against Torture) reaffirm this prohibition.[67] The ICCPR also mandates that persons in detention must "be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person."[68]Although Malaysia is not a party to the ICCPR or the Convention against Torture, the ban on torture and other mistreatment is a fundamental principle of customary international law that applies at all times and in all circumstances.

Denial of Immediate Medical Assistance and Access to Counsel

Detainees injured on December 8 and 9 were denied immediate medical assistance. Mohamad Faiq bin Hafidh whose left eye was bleeding due to injuries he suffered on December 9 wrote, "I only received eye wash treatment on Sunday, December 12, 2004. I was given full treatment on Monday, December 13, 2004."[69] Mohamad Faiq bin Hafidh's wife corroborated the eye injury and told Human Rights Watch, "I was shocked to see [him] on December 11. He had bruises on his face and his left eye was swollen and still bleeding. I put a small towel on his eye."[70]

Mat Sah bin Mohamad Satray had a fractured rib as the result of being beaten on December 9. He was not taken to the hospital until December 13, 2004.[71]

Abdul Murad Samad wrote that he was not given medical treatment until December 13, 2004, when he was taken to the medical assistant at the detention center, who then referred him to the TaipingHospital.[72] He wrote, "My injured eye was washed and I was given medication. My back was hurting and I was given painkillers and my ribs were x-rayed."[73]

In a letter signed by twenty-three detainees to the Internal Security Minister, detainees wrote, "The earliest any of us were brought to the hospital was on the third day of the incident, on Saturday afternoon. Some were also brought to the hospital on the eighth day. Many were taken to the hospital after the bruises and marks of abuse were gone."[74]

The wives of three detainees beaten on December 9 told Human Rights Watch that TaipingHospital, where their husbands were treated, refused to give them copies of their husbands' medical reports.[75]

The detainees' lawyers' requests to meet their clients on December 10 were denied by Kamunting officials on the grounds that Suhakam had scheduled a visit.[76] A subsequent request was granted and the lawyers met their clients on December 28, 2004.

Punishment

Twelve T2B detainees and eight of the T4B detainees were singled out and punished for the events on December 8-9, 2004. The T2B detainees are housed separately in Tempat Penerimaan (intake cells), which are used when detainees initially arrive at the camp, and also serve as punishment cells. As of September 2005, three of them remain in solitary confinement.[77] According to the detainees' lawyers, the detainees are allowed out of the cell only from 7:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. They are not provided a bed or mattress, but instead sleep on cement floors. The cells have no light, but only an air vent (1 x 2 feet) with metal bars.[78]

Eight detainees from T4 block are housed in individual cell blocks and not in a dormitory like the rest of the ISA detainees. According to the lawyers of the detainees, these eight are branded as the vocal group because they voiced their concerns to prison officers, lawyers, SUHAKAM, and the press.[79]They are handcuffed when taken to a medical assistant or when prison officials meet with them.[80]

Such punishment of the detainees violates the Internal Security Act (Detained Persons) Rules, which allow for punishment for five days for minor offenses and seven days for aggravated offenses and only upon a factual inquiry.[81] According to the lawyer for the detainees, no such inquiry was conducted before these detainees were punished.[82]

Restrictions on Family Visits Reimposed

A wife of a detainee, who has been in detention since 2003, told Human Rights Watch:

When we used to visit him before the incident, we, the children and I, could touch him, and sit together in the visiting room. When he was brought to the room, the children would run out and meet him in the corridor and he would come into the room with our son on his shoulders. That would make him happy, but now it's different.[83]

She continued that prison officials are now present in the visiting room and "monitor what my husband says to me."[84]

Another wife, whose husband has been detained since 2002, explained:

I was surprised when I first saw the visiting room in January 2005. There was a wire mesh and fiberglass partition separating us. Why should he be treated this way? We are no longer allowed to do salam (shake hands). My son is very upset that he can no longer hug his father. The only way to communicate is through a hole located at the bottom of the partition, which is 3-4 feet above ground level and is the size of a 50 sen coin. We have to bend down to talk through this hole. There is no intercom connecting the partitioned area. It is very difficult to hear what my husband says.[85]

In explaining the size of the holes in the partition, another ISA detainee's wife, whose husband has been detained since 2002, explained, "I can put my two fingers through the hole. I have to bend really low so I can talk through the hole. This is very difficult. I cannot hear my husband very clearly."[86]

Abdul Murad bin Sudin, who has been detained since October 2002, described his December 26, 2004, visit with his wife and children: "During the forty-five minute visit I was not allowed to directly meet them. The room was fenced with . . . wire and obstructed by fiberglass with holes as big as my index finger. I could only touch my children and wife through a finger that was thrust into that hole."[87]

A wife of a detainee, whose husband has been detained since 2001, told Human Rights Watch, "My husband does not know when he will be released. He and others tried hard to convince the officials to allow us better family visits. He was not asking for much. Now that too has been denied."[88]

The new restrictions have decreased the frequency that detainees' families, who have to travel long distances for visits, often at great expense, can visit. One detainee's wife who lives far from Kamunting and finds it expensive to travel complained that prior to December 2004 she was able to visit her husband two consecutive days a week, but now things have changed. "Before the riot I could visit my husband both Saturday and Sunday. Now if I visit on Saturday I cannot visit him on Sunday, but have to wait till the following weekend."[89]

Failure to Investigate

Wives of some of the detainees filed complaints with the police on December 11 and 18, 2004, with the Taiping Police Station, and filed a complaint with Suhakam on December 15, 2004. Detainees also filed complaints on December 21, 2004.[90] According to the lawyer for some of the detainees, the findings of any official investigation have not been made public and to date no personnel involved in the abuse of detainees have been disciplined or charged.[91]

The Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, Suhakam, reacted quickly, visiting Kamunting on December 11, 2004. However, for unspecified reasons, to date it has not published its findings. It is not clear if or how it communicated its findings to the government or if it has advocated for prosecutions or disciplinary action against those responsible for abuses.

V.No Judicial Review on the Grounds for Detention

It appears to offend the doctrine of separation of powers when the Executive is seen to be the judge of its own actions

-Former Chief Justice of Malaysia Tun Mohamed Dzaiddin Abdullah, September 30, 2003, referring to the absence of judicial review of detention orders.[92]

Malaysia's once-proud judiciary has been excluded from playing an effective role in ensuring that ISA detainees are treated according to Malaysian and international law.[93]In 1988, the government led by former Prime Minister Mahathir amended the ISA to explicitly limit the court from reviewing the merits of ISA detention. Section 8B of the ISA prevents courts from reviewing the merits of ISA detentions, thus leaving detainees without any effective recourse to challenge their detention.[94]Although the law leaves room for review of "procedural requirements," the deference granted by the courts to the government in ISA cases is so great that even this lone avenue of challenge has been of limited use.

Courts routinely dismiss habeas corpus petitions challenging procedural deficiencies in ISA detentions. In February 2005, the Federal Court affirmed the dismissal of habeas corpus petitions brought by eight alleged JI members, which were previously dismissed by the High Court in 2004. In the proceedings before the High Court, the prosecution justified the detention on the grounds that the detainees participated in meetings and training exercises for a holy war. The court found that the minister of internal security in reviewing the affidavit evidence had "objectively" considered facts which compelled him to "conclude subjectively that, [the detainees' acts] were 'prejudicial to the security of Malaysia or any part thereof.' It was those 'prejudicial' acts which the Minister sought 'to prevent.'"[95] In effect, the court rubber-stamped the allegations presented by the government, presuming them to be correct without any evidence offered in court and without any opportunity for the detainees to demonstrate otherwise.

Similarly, on July 25, 2005, the Federal Court affirmed the High Court's dismissal of the habeas corpus petitions of five ISA detainees, including Nik Adli, a Parti Islam Se Malaysia (PAS) member and son of senior PAS cleric Nik Aziz, finding no procedural inadequacies in the more than four-year detention of these detainees. The detainees argued that they were not served with a statement of the allegations under which the internal security minister extended their detention order for another two years, and that the minister did not consult the ISA Advisory Board when extending the detention order as required by the ISA.[96]A lower court dismissed their arguments, finding that service of the allegations is necessary only when a detention has been extended on wholly or partly different grounds than the original order of detention.[97] Since the allegations were the same for extending the detention order as the original order the minister need not serve detainees with another statement of allegation.[98] In effect, this reasoning would provide justification for a series of detention orders amounting to a life sentence, all based on the same original, untested, allegations that led to the original detention.

International human rights law requires that persons deprived of their liberty be allowed to challenge their detention before a court.The ICCPR mandates that "[a]nyone who is deprived of his liberty by arrest or detention shall be entitled to take proceedings before a court, in order that the court may decide without delay on the lawfulness of his detention and order his release if the detention is not lawful."[99]

The writ of habeas corpus has historically served as a remedy against unchecked power of the executive.This right is guaranteed in the Malaysian Federal Constitution: "Where complaint is made to a High court or any judge thereof that a person is being unlawfully detained the court shall inquire into the complaint and, unless satisfied that the detention is lawful, shall order him to be produced before the court and release him."[100]But in the context of the ISA, by amending the law in 1988 the government stripped the courts' jurisdiction from reviewing the legality of detention in violation of international law and the Malaysian Constitution.

Publicly, the Malaysian government maintains that ISA detainees are afforded due process. For instance, in the Malaysian government's initial report to the United Nations Counter Terrorism Committee, the ISA is presented as one of the main legislative provisions satisfying the requirements of Security Council Resolution 1373.[101]Resolution 1373 requires criminal, financial, and administrative measures aimed at individuals and entities considered supportive of or involved in terrorism. The government states that the ISA is "subject to the rule of law and the principles of natural justice, with the Legislative, Executive and Judicial branches of government acting as checks and balances.Further safeguards for due process are also enshrined in the Federal Constitution and incorporated into the relevant laws."[102]Contrary to this statement, ISA detainees have no right to contest the merits of their detention in court and the executive branch has unfettered discretion to detain and release persons for alleged security threats at its whim.

VI. The Malaysian Government's Defense of the ISA

Implementation and enforcement of the ISA, 1960, has always been undertaken in the most decent moral conduct and with careful detail, to curb any element who jeopardizes the security of the country. That is why the government only arrests someone under the ISA when there are solid reasons against the person, that they will endanger national security.

-Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi, June 28, 2005.[103]

Prime Minister Badawi's government firmly defends the ISA as an effective tool to maintain the security of Malaysia and continues to ignore the documented human rights violations of those detained under this draconian law.

Minister in the Prime Minister's Department Datuk Mohamed Nazri, responsible for parliamentary affairs and head of the Parliamentary Caucus on Human Rights, told Human Rights Watch that the ISA is needed to "promote racial harmony in the country" and that "the government is better equipped to evaluate whether an individual poses a threat to national security than anyone else."[104]He elaborated that, "They [ISA detainees] have not committed any crime because ISA is preventive. You cannot, therefore, go to court. The government has information that something will happen. We can't wait till it happens. Lives and property will be lost. So before it happens we detain them."[105]

Malaysian authorities, who once faced international criticism for use of the ISA for political purposes, now feel less pressure. For instance, Datuk Mohamed Nazri told Human Rights Watch that because of Guantnamo the United States no longer criticizes Malaysia's use of the ISA.[106]U.S. practice of indefinite detention without charge or trial of persons at GuantnamoBay and elsewhere has strengthened Malaysia's ability to justify its practice of preventive arbitrary detention. The Inspector General of Police, Tan Sri Mohamed Bakri Omar, voiced this sentiment when addressing the Conference on Democracy and Global Security in Istanbul, Turkey in June 2005. His statement, made available to Bernama, Malaysian National News Agency, asserted that governments have valid and substantial grounds to enact laws that restrict human rights. Citing the USA Patriot Act and the United Kingdom's Prevention of Terrorism Act of 2005, he argued that governments must check the excesses of individuals and their civil liberties if the state is to survive.[107]

Parliamentary Caucus Stance

Despite such rhetoric the ISA is not uniformly supported even within the governing party. Notably, some members of the government have advocated for the release of ISA detainees held for over two years. The Parliamentary Caucus on Human Rights, comprised of members from the ruling UMNO party and the opposition Democratic Action Party (DAP), visited KamuntingDetentionCenter on June 17, 2005. Shortly thereafter, the caucus issued a public statement calling for a number of improvements:

- the release of ISA detainees who had been in detention for more than two years;

- restoration of rights of detainees in T1 block and Tempat Penerimaan (intake/punishment cells);

- repatriation of foreigners detained under the ISA;

- removal of wire mesh and fiberglass board to allow detainees and their families physical contact; and

- provision of adequate social welfare support for needy family members of detainees.[108]

Deputy Internal Security Minister Chia Kwang Chye responded to the caucus' statement by saying that, "The review [of detention] is always on-going and [is] based on the reports from various authorities concerned whether they are still a threat to national security. If they are still a threat, then the detention will be extended."[109]

The Royal Commission's View

In April 2005 the Royal Commission to Enhance the Operation and Management of the Royal Malaysia Police issued its final report, with 125 recommendations that were made public in May 2005. The report was pathbreaking in many ways, but its recommendations on the ISA were modest. It recommended that by May 2006 the government should:

amend section 73 of the Internal Security Act to reduce the initial period of detention from sixty to thirty days;

present detainees before a magistrate within 24 hours of detention and allow them access to counsel at that time; and

if "good reason(s)" exist that detainees should not be allowed access to counsel when produced before a magistrate, allow them access to family members and lawyers as soon as possible or within seven days of arrest.[110]

The Commission, however, failed to recommend the repeal of the ISA, as urged by Suhakam and local and international human rights organizations. The Commission also abstained from critiquing section 8B of the ISA, which bars judicial review of detention on the ground that such a critique was beyond the terms of reference of the Commission, whose mandate was to review the conduct of the police.[111]

As of September 2005, the Malaysian government was reviewing the recommendations. Prime Minister Badawi has appointed five sub-committees to analyze the recommendations. In July 2005, in response to inquiries from members of parliament, he responded that the government is "in principle" committed to implementing all 125 recommendations, but that "implementation will be based on priority [and] suitability" taking into consideration "financial and legal implications."[112] He further noted that the recommendations will be implemented over a period of time ranging from six months to five years as suggested by the Commission.[113]

Even if the Malaysian government implements the Commission's modest recommendations, the ISA will still fail to meet international human rights standards. Prime Minister Badawi should break with the authoritarian governments of the past and declare an end to his country's practice of detaining suspects without trial. Those suspected of criminal or terrorist activities should be charged and must have their day in court.

VII. Recommendations

To the Malaysian Government

Abolish the ISA. All persons arrested in Malaysia should be promptly brought before a judge, informed of the charges against them, and have access to legal counsel and family members.They should be tried in conformity with international fair trial standards.

Immediately charge or release all individuals currently held under the ISA. Those charged should have prompt access to legal counsel and family members, and be tried in conformity with international fair trial standards.

In the interim, implement the recommendations of the Parliamentary Caucus on Human Rights and recommendations of the Royal Commission to Enhance the Operation and Management of the Royal Malaysia Police.

Set up an independent commission of inquiry into allegations of abuse in December 2004

Prosecute or subject to appropriate disciplinary action any police officers or prison officers found to have abused ISA detainees in KamuntingDetentionCenter in December 2004.

End the prolonged punishment of ISA detainees involved in the December 2004 incident.

Allow immediate and unfettered access to KamuntingDetentionCenter to both domestic and international human rights NGOs.Any individual detainee who wishes to speak to NGO representatives should be allowed to do so in private.

Sign and ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and begin the process of reforming all domestic law, including the ISA, to conform with these international instruments.

To SUHAKAM

- Conduct a public inquiry into the allegations of abuse in December 2004.

To the U.S.Government

- Renew the U.S. government's strong pre-September 11th criticism of the ISA, and push for all ISA detainees, including those held on allegations of association with terrorism, to be either tried or released.

To the U.K. Government

- Push for repeal of the ISA and urge the government to either try or release all ISA detainees, including those held on allegations of association with terrorism.

To the United Nations

To the Special Rapporteur on Torture

- Call on the Malaysian government to sign and ratify the Convention against Torture and begin an investigation of reports of torture and other mistreatment of ISA detainees.

To the Counterterrorism Committee of the United Nations

- Call on the Malaysian government to abide by its obligations under international human rights standards when engaging in counter-terror activity.

- Establish a long-term plan with Malaysia for developing mechanisms for combating terrorism while protecting human rights.

VIII. Acknowledgements

This report was written by Sahr MuhammedAlly, the Alan R. and Barbara D. Finberg fellow for Human Rights Watch. It is based on research conducted in Malaysia in July 2005 and subsequently via telephone and email. The report was edited by Brad Adams, executive director of the Asia Division and Sam Zia-Zarifi, deputy director of the Asia Division of Human Rights Watch. The report was also reviewed by Dinah PoKempner, general counselof Human Rights Watch, and Joe Saunders, deputy program director. Ranee Adipat, associate in the Children's Rights Division and Jo-Anne Prud'homme, associate in the Asia Division proofread and provided technical assistance. Production and further assistance was provided by Andrea Holley, Rafael Jiminez, Fitzroy Hepkins, and Jose Martinez. Mabel Cheah translated the detainees' statements.

Human Rights Watch would like to those who spoke to us for this report, some of whom, included family members, did so at personal risk. We are extremely grateful to Edmund Bon, attorney for many of the detainees, Chang Lih Kang and Syed Ibrahim Syed Noh from the Abolish ISA Movement; Elizabeth Wong of HAKAM; Cynthia Gabriel and Seah Li Ling of SUARAM; Latheefa Koya, attorney for some ISA detainees, and Dato Karam Chand Vohrah and Long Seh Lih of SUHAKAM, all of whom provided invaluable assistance and shared with us their insights. We would also like to thank Lim Kit Siang (DAP) and Datuk Mohamed Nazri (UMNO).

Appendix A

Copy of original drawing of KamuntingDetentionCenter by an ISA detainee identifying location of events (A-O) on December 8 and 9, 2004.

[1]Internal Security Act 1960, section 72.

[2] Ibid., section 8.

[3]Ibid., section 12. For example, in November and December 2002, the government ignored the recommendation of the Advisory Board to release five opposition party KeADILan activists-the Justice Party formed by Anwar Ibrahim's wife Dr. Wan Azizah Ismail-Tian Chua, Saari Sungib, Likman Noor Adam, Dr. Badrulamin Bahron, and Hishamuddin Rais. The activists were eventually released in June 2003 on the expiration of their two-year detention period because the government no longer considered them a threat to security. See P. Ramakrishnan, "Scrap the ISA Advisory Board," Aliran media statement, March 10, 2003 [online], http://www.aliran.com/ms/2003/0115.html (retrieved August 10, 2005).

[4] See Human Rights Watch, In the Name of Security: Counterterrorism and Human Rights Abuses Under Malaysia's Internal Security Act (May 2004); Human Rights Watch, Malaysia's Internal Security Act and Suppression of Political Dissent a Human Rights Watch Backgrounder (2002); Amnesty International, Human Rights Undermined: Restrictive Laws in a Parliamentary Democracy (1999); Nicole Fritz and Martin Flaherty, Unjust Order: Malaysia's Internal Security Act (New York: Joseph R. Crowley Program in International Human Rights, Fordham Law School 2003); Abolish ISA Movement, Torture Under the ISA, Memorandum Submitted to the Royal Commission to Enhance the Operation and Management of the Royal Malaysia Police (2004), Suaram, Malaysia Human Rights Reports2004 (2005).

[5] "Detained Islamic Militants Complain of Abuse by Malaysian Police," Agence France-Presse, May 29, 2004.

[6] Leong Kar Yen, "Cops Deny Torture of Detainees in Remand Centers," Malaysiakini, July 16, 2004.

[7] In December 2003, Prime Minister Badawi announced the establishment of a Royal Commission to study and recommend measures to develop the Royal Malaysia Police into a "credible force" to maintain law and order, to increase public confidence in the police, and to strengthen accountability of police personnel. The terms of reference for the commission were: to enquire into the role and responsibilities of the Royal Malaysia Police in enforcing the laws of the country; to enquire into the work ethics and operating procedures of the police force; to enquire into issues of human rights, including issues involving women, in connection with the work of the police; to enquire into the organizational structure and distribution of human resources; human resource development, including training and development; and to make recommendations to improve and modernize the Royal Malaysia Police. Report of the Royal Commission to Enhance the Operation and Management of the Royal Malaysia Police (Royal Commission Report), ch. 1, pp. 3-5.

[8] Ibid., ch. 4, challenge 4, para. 5.5.2(iii), and ch. 10, rec. 11.

[9] Ibid., recs. 9 and 11.

[10] Ibid., rec. 4.

[11] JI has been accused of carrying out the bombings in Bali andJakarta in Indonesia in 2002 and 2003, which killed more than two hundred people. The government has claimed that the JI detainees had engaged in military training in preparation for a strike against the government. Government investigations centered on a group called Persuatuan El Ehsan, which was registered with the government as a charity organization.Members of El Ehsan claimed that donations the group collected were used for refugee relief work in Ambon and Afghanistan, but the government has claimed in media statements that El Ehsan was involved in buying weapons for the Taliban in Afghanistan and for Muslim fighters in Ambon, Indonesia, the site of violent sectarian strife between Christian and Muslim groups. See Human Rights Watch, In the Name of Security, pp. 11-17 (citing Human Rights Watch interviews in Malaysia, December 2003).

[12]The Malaysian government has claimed that the KMM was founded by members of the Parti Islam Se Malaysia, or PAS, Malaysia's largest Islamist opposition party, in the 1980s.According to the government, the KMM was set up with the complementary goals of preparing for jihad and protecting PAS leaders from future attacks by government forces. LawrenceBartlett, "Arrests in Malaysia Highlight Fears of Abuse of War on Terror," Agence France-Presse, October 11, 2001.

[13] "Malaysian Police Detain Nine Over Illegal Issuance of ID Cards," BBC Monitoring Asia Pacific, February 15, 2005.

[14] "Malaysian PM says won't Hand Nuke Suspect to U.S.," Reuters, February 17, 2005.

[15] Email from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, August 26, 2005.

[16] Parliamentary Caucus on Human Rights Preliminary Report on Fact Finding Visit to Kamunting Detention Centre on June 17, 2005 (Parliamentary Caucus Statement), copy on file with Human Rights Watch. See also Aliran's ISA Watch [online], http://www.aliran.com/monthly/2001/3e.htm (retrieved on July 26, 2005).

[17] "Noh Omar Supports Suggestion to invoke the ISA for Diesel Thieves," Bernama, May 2, 2005.

[18] "Malaysia Announces Probe into Previously Unknown Islamic Militant Group," BBC Monitoring Asia Pacific, May 22, 2005; "Malaysian Official Denies New Militant Group Uncovered, Says He was Misquoted by Local Reporters," Associated Press, May 23, 2005.

[19] Email from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, August 8, 2005.

[20] For details on the Karachi detainees see Human Rights Watch, In the Name of Security.

[21] "Malaysia Releases Five Internal Security Act detainees from KamuntingDetentionCenter," BBC Monitoring Asia Pacific, July 17, 2004.

[22] "Bali bombing Suspect Freed in Malaysia: Official," Agence France-Presse, March 22, 2005.

[23] "Wan Min Urges Dr. Azhari and Nordin to Repent," Bernama, March 23, 2004.

[24] Mark Bendeich, "Malaysia Says Has Dismantled Islamic Terror Cells," Reuters, June 21, 2005.

[25]Suhakam, Report of the Public Inquiry into the Conditions of Detention Under the Internal Security Act 1960, (2003), pp. 25-26.

[26] Ibid., p. 26.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid., p. 37.

[29] Ibid., p. 38.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview with wives of detainees (names withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Memorandum of Protest of KEMTA's Excessive Use of Force Towards Detainees on December 8 and 9, 2004, to the Minister of Internal Security, dated December 22, 2004, signed by twenty-three detainees from block T4 (KEMTA Protest Letter), copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[34] Leslie Lau, "Weapons Cache in Detention Camp in Perak," The Strait Times, December 11, 2004.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] According to the attorney for some ISA detainees, Zulkifi is the Malay name for Deny Ofresio. Email correspondence from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, August 2, 2005.

[38] Handwritten statement of Ahmed Yani Bin Ismail, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[39] Handwritten statement of Mohamad Khidar bin Kadran, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[40]Handwritten statement of Mohamad Zamri Sukirman, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[41] Email from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, July 29, 2005.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Eddie Chua, "Family Members Claims ISA Detainees Assaulted," Sunday Malay Mail, December 12, 2004.

[45] Lau, "Weapons Cache in Detention Camp in Perak," The Strait Times.

[46] "Jemaah Islamiyah Detainees' Possession of Weapons Shows Lax Malaysian Security," BBC Monitoring Asia Pacific, December 12, 2004 (citing Malaysian newspaper Berita Harian web site in Malay, December 11, 2004).

[47] KEMTA Protest Letter.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid. Human Rights Watch interview with wives of detainees (names withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Human Rights Watch interview with wives of three detainees (names withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005, and July 5, 2005. The wives told Human Rights Watch that photographs of their husbands were circulated amongst the prison personnel prior to the December 8, 2005. Yazid Sufaat and Ahmad Yani Ismail similarly allege, in their handwritten statements, that their photographs were disseminated amongst the prison personnel prior to December 8. Handwritten statements of Ahmad Yani Ismail and Yazid Sufaat, copies on file with Human Rights Watch.

[53] Human Rights Watch interview with wives of two detainees (names withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[54] Handwritten statement of Mohidin bin Shari, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[55] Handwritten statement of Abdul Rashid bin Anwarul, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[56] Handwritten statement of Ahmad Yani Ismail, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[57]Handwritten statement of Yazid Sufaat, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[58] Handwritten statement of Zainun Rasyhid, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[59] Handwritten statement of Abdullah bin Mohamed Nor, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[60]Handwritten statement of Mat Sah bin Mohamad Satray, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[61] Handwritten statement by Mohamad Faiq bin Hafidh, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[62] Handwritten statement of Yazid Sufaat, copy on file with Human Rights Watch. These allegations are consistent with claims previously made by other ISA detainees. Detainees held in Police Remand Centers alleged that they were forced to strip naked before questioning began, forced to urinate in front of the interrogators, forced to masturbate, and asked questions about detainees' sex life and adequacy of their sexual performance. See Human Rights Watch, In the Name of Security, pp. 26-27.

[63] Handwritten statement of Abdul Murad bin Sudin, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[64] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[65] KEMTA Protest Letter.

[66]Universal Declaration of Human Rights, art. 5, U.N. General Assembly Resolution 217A (III), December 10, 1948.

[67] ICCPR, December 16, 1966, 999 U.N.T.S. 171, art. 7; Convention Against Torture, art. 3, December 10, 1984, 1465 U.N.T.S. 85. The United Nations Body of Principles for the Protection of all Persons Under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment similarly prohibits torture, cruel, inhuman degrading treatment of punishment. U.N. General Assembly Resolution 43/173 (1988), principle 6.

[68] ICCPR, art. 10.

[69] Handwritten statement of Mohamad Faiq Hafidh, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[70] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[71] Handwritten statement of Mat Sah bin Mohamad Satray, copy on file with Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch interview with family member of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[72] Handwritten statement of Abdul Murad bin Sudin, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[73] Ibid.

[74] KEMTA Protest Letter.

[75] Human Rights Watch interview with detainees' wives (names withheld), Kula Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[76] Email from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, August 5, 2005.

[77] Human Rights Watch interview with Edmund Bon, Kuala Lumpur, July 3, 2005.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Ibid.

[81]Internal Security Act (Detained Persons) Rules 1960, arts. 71-72.

[82] Email from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, August 8, 2005.

[83] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kula Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[86] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[87]Handwritten statement of Abdul Murad bin Sudin, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[88] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kula Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[89] Human Rights Watch interview with wife of detainee (name withheld), Kuala Lumpur, July 2, 2005.

[90] Letter from Shukry Omar Talib to Professor Hamdan Adnan, Suhakam, undated, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[91] Email from Edmund Bon to Human Rights Watch, August 9, 2005.

[92] "Courts can Review Powers of Police Under ISA, Says Ex-Chief Justice," Bernama, September 30, 2003 (referring to the absence of judicial review of detention orders under section 8B).

[93] The judiciary was subjected to a long campaign of intimidation and interference by former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed. In October 1987, Mahathir ordered the arrest of 106 people, including human rights activists and politicians from the Democratic Action Party (DAP), Parti Islam Se Malaysia, and UMNO.These arrests took place under the operational codename lalang, a type of weed. Malaysia's courts initially expressed a willingness to review the legality of his actions, as well as allegations of corruption against Mahathir. But Mahathir responded by removing five high court judges, including then-Chief Justice Tun Salleh Abbas, and introduced section 8B of the ISA, which forbids judicial review of ISA detentions, including those brought as habeas corpus petitions. For further details on the independence of the judiciary see Human Rights Watch, In the Name of Security; International Bar Association, Justice in Jeopardy: Malaysian in 2000 (2000).

[94] Section 8B provides: "There shall be no judicial review in any court of, and no court shall have or exercise any jurisdiction in respect of, any act done or decision made by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong [the Malaysian king] or the Minister in the exercise of their discretionary power in accordance with this Act, save in regard to any question on compliance with any procedural requirement in this Act governing such act or decision."

[95]Abdul Razak bin Baharudin et al. vs. Ketua Polis Negara, Dalam Mahkamah Tinggi Malaya Di Kuala Lumpur Permohonan Jenayah No: 44-66-2003, p. 26, May 17, 2004, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[96] "Habeas Corpus: Federal Court Dismisses Nik Adli's Application," Bernama,July 25, 2005.

[97]Nik Adli v. Ketua Polis Negara, High Court Malaysia, No: 44-41-04, September 1, 2004, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[98] Ibid.

[99] ICCPR, art. 9.

[100] Federal Constitution, art. 5(2).

[101] Security Council Resolution 1373, S/RES/1373 (2001), September 28, 2001.

[102]Letter dated January 4, 2002 from the Charg d'affaires of the Permanent Mission of Malaysia to the United Nations addressed to the Chairman of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1373 (2001) concerning counter-terrorism, S/2002/35, p. 2 [online], http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N02/226/57/PDF/N0222657.pdf?OpenElement (retrieved July 27, 2005).

[103] "ISA AND RRA Arrests are Not Harum-Scarum: PM," Bernama, June 28, 2005.

[104] Human Rights Watch interview with Datuk Mohamed Nazri, Minister in the Prime Minister's Department, July 8, 2005.

[105] Ibid.

[106] Ibid.

[107] "Preventive Laws Necessary for Governments Today," Bernama, June 14, 2005.

[108] Parliamentary Caucus on Human Rights, Preliminary Report on Fact Finding to KamuntingDetentionCenter on June 17, 2005, undated, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[109] Beh Lih Yi, "Government Rebuffs Call to Free ISA Detainees," Malaysiakini, June 29, 2005.

[110] Royal Commission to Enhance the Operation and Management of the Royal Malaysian Police, ch. 10, rec. 4. "Good reason" is not defined by the Commission.

[111] Ibid., ch. 10, para. 2.4.5.

[112] Beh Lih Yi, "Special Branch reform back on the agenda," Malaysiakini, July 5, 2005; "Proposals will be Implemented," The Sun, July 5, 2005.

[113] Ibid.