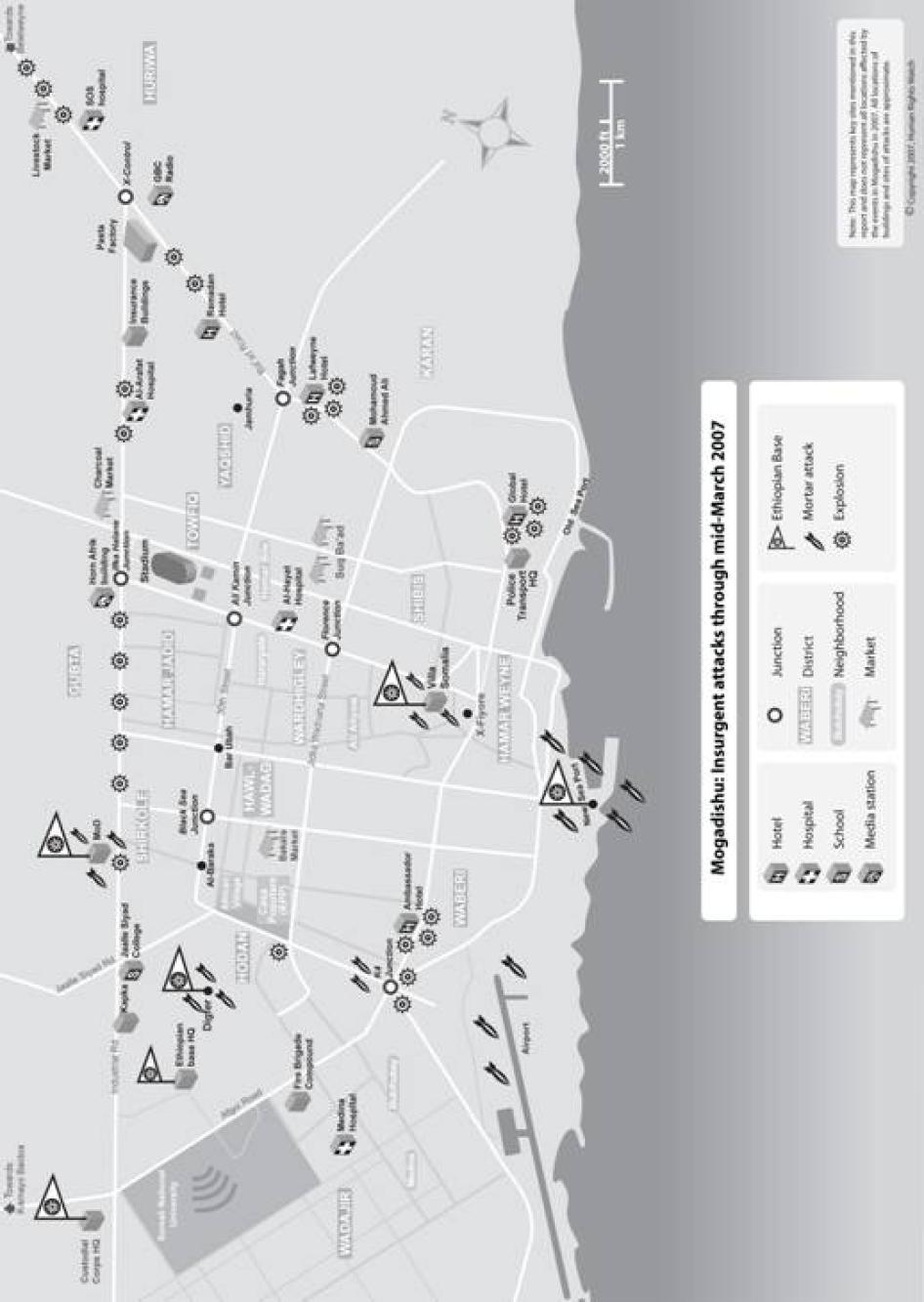

Map 1: Mogadishu: Insurgent attacks through mid-March 2007

Map 2: Mogadishu: Ethiopian offensives in March and April 2007

I. Summary

The year 2007 brought little respite to hundreds of thousands of Somalis suffering from 16 years of unremitting violence. Instead, successive political and military upheavals generated a human rights and humanitarian crisis on a scale not seen since the early 1990s.

Since January 2007, residents of Mogadishu, the Somali capital, have been gripped by a terrifying campaign of violence that has killed and injured hundreds of civilians, provoked the largest and most rapid displacement of a civilian population for many years, and shattered the lives, homes, and livelihoods of thousands of people. Although overlooked by much of the world, it is a conflict whose human cost is matched by its regional and international significance.

The conflict in Mogadishu in 2007 involves Ethiopian and Somali government forces against a coalition of insurgent groups. It is a conflict that has been marked by numerous violations of international humanitarian law that have been met with a shameful silence and inaction on the part of key foreign governments and international institutions.

Violations of the laws of war documented in this report include the deployment of insurgent forces in densely populated neighborhoods and the widespread, indiscriminate bombardment of these areas by Ethiopian forces. The deliberate nature of these bombardments, evidence of criminal intent, strongly suggests the commission of war crimes.

Underpinning the developments in Somalia is the striking rise to power and rapid collapse of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), a movement based on a coalition of sharia courts, in Mogadishu in mid-2006. The Islamic Courts were credited with bringing unprecedented stability to a city plagued by lawlessness and extreme violence. Speculation about whether early indicators of extreme and repressive action by the ICU would evolve into more moderate policy was cut short by the events that followed.

The presence of some radical and militant Islamist elements within the ICU and their belligerent statements stoked fears within and outside the region. The ICU's dominance also threatened the Somali Transitional Federal Government (TFG), which had little international support and minimal popular legitimacy, particularly in Mogadishu. In December 2006 Somalia's historic rival Ethiopia intervened in Somalia in support of the TFG and with the backing of the United States government, and ousted the ICU in a matter of days. Although the campaign was conducted in the name of fighting international terrorism, Ethiopia's actions were rooted in its own regional and national security interests, namely a proxy war with Eritrea and concern over Ethiopian armed opposition movements supported by Eritrea and the ICU.

Following the establishment of Ethiopian and TFG troops in Mogadishu in January 2007, residents of Mogadishu witnessed a steady spiral of attacks by insurgent forces aimed at Ethiopian and TFG military forces and TFG officials. Increasingly, Ethiopian forces launched mortars, rockets, and artillery fire in response. A failed March 21 and 22 disarmament operation by the TFG resulted in the capture of TFG troops and-in scenes evocative of the deaths of US soldiers in 1993-the mutilation of their bodies in Mogadishu's streets.

In late March Ethiopian forces launched their first offensive to capture Mogadishu's stadium and other locations, which met with resistance from a widening coalition of insurgent groups. Ethiopian forces used sustained rocket bombardment and shelling of entire neighborhoods as their main strategy to dislodge the mobile insurgency and then occupy strategic locations. Hundreds of civilians died trying to flee or while trapped in their homes as the rockets and shells landed. Tens of thousands of people fled the city.

Four days of intense bombardment and fighting was ended by a brief ceasefire negotiated by the Ethiopian military and Hawiye clan elders. The ceasefire faltered and then broke in late April, when Ethiopian forces launched their second major offensive to capture additional areas of north Mogadishu. Again, heavy shelling and rocket barrages were used against insurgents in densely populated civilian neighborhoods. Hundreds more people died or were wounded. On April 26 the TFG, which played a nominal role supporting the Ethiopian military campaign, declared victory. Within days, insurgent attacks resumed, increasingly based on targeting Ethiopian and TFG forces with remote-controlled explosive devices.

Based on dozens of eyewitness accounts gathered by Human Rights Watch in a six-week research mission to Kenya and Somalia in April and May 2007, plus subsequent interviews and research in June and July, this report documents the illegal means and methods of warfare used by all of the warring parties and the resulting catastrophic toll on civilians in Mogadishu.

The insurgency routinely deployed their forces in densely populated civilian areas and often launched mortar rounds in "hit-and-run" tactics that placed civilians at unnecessary risk. The insurgency possibly used civilians to purposefully shield themselves from attack. They fired weapons, particularly mortars, in a manner that did not discriminate between civilians and military objectives, and they targeted TFG civilian officials for attack. In at least one instance, insurgent forces executed captured combatants in their custody, and subjected the bodies to degrading treatment.

Ethiopian forces failed to take all feasible precautions to avoid incidental loss of civilian life and property, such as by failing to verify that targets were military objectives. Ethiopian commanders and troops used both means of warfare (firing inherently indiscriminate "Katyusha" rockets in urban areas) and methods of warfare (using mortars and other indirect weapons without guidance in urban areas) that violated international humanitarian law. They routinely and repeatedly fired rockets, mortars, and artillery in a manner that did not discriminate between civilian and military objectives or that caused civilian loss that exceeded the expected military gain. The use of area bombardments in populated areas and the failure to cancel attacks once the harm to civilians became known is evidence of criminal intent necessary to demonstrate the commission of war crimes. The Ethiopian forces also appeared to conduct deliberate attacks on civilians, particularly attacks on hospitals. They committed pillaging and looting of civilian property, including of medical equipment from hospitals.

The Transitional Federal Government forces failed to provide effective warnings when alerting civilians of impending military operations, committed widespread pillaging and looting of civilian property, and interfered with the delivery of humanitarian assistance. TFG security forces committed mass arrests and have mistreated persons in custody.

Reaction to these serious international crimes has been muted to the point of silence. Despite the scale and gravity of the abuses in Mogadishu in 2007, there has been no serious condemnation by key governments or institutions. The human rights crisis that has permeated Somalia for years, now significantly amplified in the past six months, has yet to even reach the agenda of many international actors. Easing the suffering of Somali civilians and building a stable state cannot be accomplished in a human rights vacuum.

Key governments and international institutions such as the United States, the European Union and its members, the African Union, the Arab League, and the United Nations Security Council must recognize the urgent need for human rights protection and accountability in Somalia.

International donors and actors must take immediate action to condemn the appalling crimes that have been perpetrated and senda clear signal to all the warring parties that impunity for these crimes willnot be tolerated. The United States and the European Union provide significant financial, technical, and other assistance to both Ethiopia and the Somali Transitional Federal Government and should use their leverage to press for respect for human rights and international humanitarian law.

Independent human rights monitoring and reporting must be increased and international donors should encourage, assist, and finance efforts to make those responsible for abuses accountable for Somalia's latest cycle of violence.

II. Key Recommendations

To the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia (TFG)

- Immediately issue clear public orders to all TFG security forces to cease attacks on and mistreatment of civilians and looting of civilian property, and ensure that detainees have access to family members, legal counsel, and adequate medical care while in detention.

- Ensure humanitarian assistance to all civilians in need, including by facilitating the access of humanitarian agencies to all displaced persons in and around Mogadishu.

- Investigate allegations of abuses by TFG forces and hold accountable the members of the TFG forces, whatever their rank, who have been implicated in abuses.

- Take all necessary steps to build a competent, independent, and impartial judiciary that can provide trials that meet international fair trial standards. Abolish the death penalty as an inherently cruel form of punishment.

- Invite the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to increase the number of staff monitoring and reporting on human rights abuses in Somalia and request technical support for the judiciary and the establishment of an independent national human rights commission.

To the groups comprising the insurgency

- Cease all attacks on civilians and civilian objects, including government officials and employees not directly participating in the hostilities. Cease all attacks that cause indiscriminate or disproportionate harm to civilians or civilian objects, including attacks in crowded civilian areas, such as busy roads, village or city streets, markets, or other public gathering places.

- Avoid locating, to the extent feasible, insurgent forces within or near densely populated areas, and where possible remove civilians from the vicinity of such forces. Avoid using populated areas to launch attacks and cease threatening civilians who protest the use of their neighborhoods as launching sites. Never purposefully use civilians to shield insurgent forces from attack.

- Publicly commit to abide by international humanitarian law, including prohibitions against targeting civilians, using indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks, and using civilians as "human shields."

To the government of Ethiopia

- Cease all attacks that deliberately target civilians and cease using means and methods of combat that cannot discriminate between civilians and military objectives. Civilian objects such as schools, hospitals, and homes must not be attacked unless currently being used for military purposes.

- Cease all indiscriminate attacks and attacks in which the expected civilian harm is excessive compared to the concrete and direct military gain anticipated. In particular, cease the use of area bombardments of populated areas of Mogadishu.

- Issue clear public orders to all forces that they must uphold fundamental principles of international humanitarian law and provide clear guidelines and training to all commanders and fighters to ensure compliance with international humanitarian law.

- Investigate and discipline or prosecute as appropriate military personnel, regardless of rank, who are responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law including those who may be held accountable as a matter of command responsibility.

To the European Union and its member states, the European Commission, the United Nations Security Council, the African Union, the Arab League, and the government of the United States

- Publicly condemn the serious abuses of international human rights and humanitarian law committed by all parties to the conflict in Mogadishu in 2007, and call on the Ethiopian government and the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia to take all necessary steps, including public action, to ensure that their forces cease abuses against civilians.

- Support measures to promote accountability and end impunity for serious crimes in Somalia, including through the establishment of an independent United Nations panel of experts to investigate and map serious crimes and recommend further measures to improve accountability.

- Publicly promote and financially support civil society efforts to provide humanitarian assistance, services such as education, monitoring of the human rights situation, and efforts to promote national solidarity. Promote and support TFG efforts to improve the functioning of the judicial system and to establish a national human rights commission. Provide voluntary contributions to support an expanded OHCHR field operation in Somalia.

III. Background

The continuing crisis in Somalia is multifaceted, with roots that can be traced back to the 21-year rule of President Mohamed Siad Barre (19691991).[1] Barre's military coup in 1969 ended Somalia's first post-independence experiment with democratic civilian government (1960-69), a period which in later years became marked by corruption, inefficient governance, and increasingly fragmentary politics centered around clan-based political parties and patronage.[2]

When Siad Barre took power in 1969, he sought and obtained support from the Soviet Union and embraced "scientific socialism" for Somalia. Among his first steps were to abolish Somalia's clan and patronage system as counter-revolutionary: a national campaign (olole) against "tribalism, corruption, nepotism, and misrule" was launched and even informal references to clan alliances were outlawed.[3] A new intelligence agency, the National Security Service (NSS), was established in 1970 to monitor "security" offenses that included nepotism and tribalism.

Barre's early rule did have some positive aspects, such as his establishment of the first written script for the Somali language, a nationwide literacy campaign (1973-75), and the empowerment of women through fairer marriage, divorce, and inheritance laws. However, his government soon degenerated into increasing dictatorship, repression, and a personality cult focused around the "Holy Trinity" of Marx, Lenin, and "the Beneficent Leader" Barre, who established an increasingly repressive and authoritarian security state, placing himself in control of all facets of state power.[4]

Barre's government suffered a serious blow when he launched an unsuccessful military invasion of the ethnic Somali Ogaden region of Ethiopia in 1977. Barre's invasion accelerated the Soviet Union's decision to support the Marxist Ethiopian regime and to abandon support for Somalia, leading to a military defeat for Barre in 1978. This set in motion an economic and political crisis of legitimacy that ultimately led to the collapse of the Barre dictatorship.[5] After breaking with the Soviet Union,[6] Barre abandoned "scientific socialism," allied himself with the West, and sought refuge increasingly in the support of his Darod clan.[7]

The increasing clan basis of Barre's regime led to the formation of opposition fronts that were similarly clan-focused, as non-Darod clans felt excluded from power.[8] One of the first setbacks to Barre came in 1981 when his attempts to undermine the economic and political power of the Isaaq clan led to the formation of the Isaaq-dominated Somali National Movement (SNM).[9] The SNM soon began launching small-scale attacks against government and military posts inside Somalia.

Barre responded to the SNM with what Human Rights Watch described as "savage counterinsurgency tactics," ordering massive bombardments of northern towns and villages that killed tens of thousands of Somali civilians and led to the internal displacement of some 500,000 northerners, with another 500,000 seeking refuge in Ethiopia.[10]

Following his 1978 break with the Soviet Union, Barre had enjoyed substantial support from the West, particularly the United States[11]-allowing Barre to expand his army from an estimated 3,000 at the time of independence to a "suffocating" 120,000 by 1982.[12] Reports from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the press about the atrocities being committed by the Barre regime led, however, to a sharp reduction in US and western aid by late 1989.

The Fall of the Barre Regime and the Outbreak of Clan Fighting

President Barre was overthrown in January 1991 by a coalition of insurgency movements including the Isaaq-dominated SNM, Gen. Mohamed Farah Aideed's largely Hawiye clan-based United Somali Congers (USC) fighting in the south-central regions, and the Ogaden clan-dominated Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM) that was based in southern Somalia.[13]

The removal of the Siad Barre government spurred new conflict among and within the clan-based opposition movements. The USC split into two factions, one supporting General Aideed and a second supporting a Hawiye businessman from the Abgal sub-clan, Ali Mahdi Mohammed. Mohammed was appointed as interim president by a group of politicians and influential elders from the Hawiye clan within two days of Barre's ouster.[14]

By late 1991 increasing numbers of individuals and armed groups competed for power in the vacuum left by Siad Barre's departure. The early 1990s saw some of Mogadishu's worst fighting as militia mobilized by General Aideed fought with those of Ali Mahdi to impose their control over the capital and the rest of the country.[15]

The war divided the capital city into two zones separated by a "green line,"[16] displaced tens of thousands of people, and cost thousands of civilians in Mogadishu and south-central Somalia their lives. The fighting in Mogadishu and subsequent clan-based conflict further south also severely affected the local harvest, creating an unprecedented famine in fertile southern Somalia.[17] Humanitarian organizations estimated that between February 1991 and December 1992, 300,000 people may have lost their lives.[18]

Between 1991 and 1993, as people died of starvation and related illnesses in their tens of thousands, freelance and clan-based militia obstructed aid efforts and looted relief. A 1992 United Nations (UN)-negotiated ceasefire failed and prompted the first UN military intervention to protect relief access and aid workers-the operation known as the United Nations Operation for Somalia (UNOSOM). In December 1992 UNOSOM's failure to end the fighting led the United States to overcome its initial reluctance and to send troops, under US command, to the UN Task Force on Somalia (known as UNITAF and codenamed "Operation Restore Hope"). In May 1993 UNOSOM and UNITAF were replaced by UNOSOM II, which had a more robust mandate under Chapter VII of the UN Charter and more than 30,000 troops from various countries.[19]US troops withdrew in 1994 after they became embroiled in conflict with General Aideed.[20] UNOSOM II left Somalia in March 1995 without achieving a breakthrough towards long-term political stability for Somalia, initially a key objective of the mission.[21]

The civil war and the successive US and UN military interventions in the early 1990s left several legacies, including a dramatic increase in the number of Somali factions and armed groups (none of which shared any common political platform or national vision), the empowerment of individual warlords, and a deep reluctance on the part of powerful states such as the United States to intervene in Somalia.[22]

Successive Failed Peace Processes: 19912004

Peace initiatives began as early as 1991. After UNOSOM withdrew in 1995, diplomatic responsibility for Somalia was left to regional governments. Egypt, Djibouti, Yemen, Ethiopia, and Kenya took turns hosting peace conferences to end the violence and reestablish a Somali state.[23] Of more than a dozen peace conferences, two were noteworthy for an understanding of current events.

The first of these was in May 2000 in Arta, a town in neighboring Djibouti.[24] During the negotiations Djibouti tried to create an atmosphere that limited the role and influence of the warlords in the conference, instead emphasizing the role of civil society groups and clan elders. The conference resulted in the first Transitional National Government (TNG) led by Abdulkasim Salad Hassan, a controversial and long-time minister under Siad Barre.[25]

The Djibouti conference also created a 245-member parliament and approved the appointment of Ali Khalif Gallaydh as prime minister. It set up a power-sharing system based on the so-called 4.5 system-meaning an equal number of representatives for the four major clans and half of a major clan's share for all the minority clans together.

Key players such as the United States, the European Union, and the African Union (then the Organization of African States, OAS) were hesitant to make any firm commitment to Somalia, given the numerous previous failed peace processes, and provided little support to the TNG.[26] But the biggest setback came from local warlords who refused to recognize and collaborate with the new administration and instead formed a Somali Reconciliation and Restoration Council (SRRC) in Ethiopia in 2001 to challenge the legitimacy of the new government.[27]

By 2002 it was clear the TNG had failed to establish any credible administration and its mandate was running out. It lacked authority on the ground and could not prevail against the opposition of powerful warlords. Kenya offered to host both sides, the TNG and SRRC, for European Commission-financed talks in Eldoret in October 2002. After two years of difficult negotiations, in 2004 Kenya brokered a power-sharing agreement through the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD, a regional umbrella group which comprises Ethiopia, Kenya, Djibouti, Sudan, Somalia, Uganda; Eritrea withdrew from membership this year in protest of IGAD's view on Ethiopia's role in Somalia).[28] The result of this process was the establishment of the current Transitional Federal Institutions: a Transitional Federal Charter, a Transitional Federal Government (TFG) and a Transitional Federal Parliament (TFP) consisting of 275 members.

In October 2004 the TFP elected Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed, a leading member of the SRRC group, as president of the TFG, who in turn appointed Ali Mohammed Gedi as prime minister.[29] Following pressure from Kenya to relocate and establish a government in Somalia, in May 2005 the TFG tried to establish itself within Somalia, but immediately split, with some members moving to Jowhar and some to Baidoa.[30]

The Ethiopian Factor

Recent events in Somalia are closely linked to regional developments. Ethiopia and Somalia are historically, socially, and politically intertwined, with several episodes of religious and territorial disputes over the Somali region of eastern Ethiopia known as the Ogaden, most recently in 1964 and 1977.[31] Ethiopian concerns over continuing Somali nationalist sentiments towards the ethnic Somali Ogaden region remains a key element in Ethiopian foreign policy decision-making.[32]

Successive Ethiopian governments have supported Somali opposition leaders and movements and the Ethiopian government led by Prime Minister Meles Zenawi has been closely involved in the various Somali peace processes. Several of the current leading figures in Somalia's military and political landscape have either received longstanding support from-in the case of Abdullahi Yusuf-or had antagonistic relations with-in the case of Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys, a former deputy leader of the militant Islamist group Al-Itihaad Al-Islaami-the Ethiopian government.

Ethiopian mistrust of Sheikh Aweys stems from his connection to Al-Itihaad Al-Islaami, originally a Salafi religious movement that evolved into a militant Islamist organization. Sheikh Aweys was actively involved in forming Al-Itihaad's military wing in the early 1990s, which fought against Ethiopia and then-militia leader and current TFG President Abdullahi Yusuf's faction in Puntland.[33] Al-Itihaad was allegedly responsible for several bombings in Ethiopia in the mid-1990s that led to its designation on a US sanctions list of individuals and organizations after the September 11, 2001 attacks.[34] In 1998, following Ethiopia's defeat of Al-Itihaad in southwestern Somalia, Sheikh Aweys returned to Mogadishu and helped found one of the clan-based Islamic Courts.

Ethiopian involvement in Somalia remains a divisive and politically charged issue for Somalis, many of whom view Ethiopian motives in Somalia with deep distrust.[35] Some Somalis blame Ethiopia for the inability of the TNG, the predecessor to the current TFG, to establish an enduring government.[36]

Ethiopian interests in Somalia are also closely linked to Ethiopia's relations with Eritrea. Although there has been little active fighting since their bloody 1998-2000 border war ended, Eritrea and Ethiopia remain bitter rivals and both governments have engaged in a form of proxy war in Somalia dating back to the late 1990s.[37]Eritrea has provided military aid and training to a variety of Ethiopian insurgent groups based in the Ogaden and Somalia, and Ethiopia has supported the TFG.[38]

The Rise of the Islamic Courts in 2006

In June 2006 the Somali political scene was shaken by the emergence of an alliance of sharia (Islamic law) courts, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU). The ICU, with Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys among its leaders, drove the warlords from Mogadishu.[39] Although the appearance of the Islamic Courts as a potent political movement was a surprise to many observers, the courts had longstanding roots in Mogadishu.[40]

In December 2004, just two months after the formation of the TFG, a group of clan-based courts that had been operating in Mogadishu for years joined to launch the ICU.[41] Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, a schoolteacher from Mogadishu, was appointed chair of the alliance.[42] By 2005 there were 11 Islamic Courts from different clans operating in Mogadishu under sharia.[43]

The increasing influence of the Islamic Courts came against the backdrop of growing US concern over the presence of alleged terrorism suspects in Somalia.[44] The US had claimed for several years that several individuals linked to al Qaeda and the 1998 bombing of the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania were being sheltered by radical Islamists in Mogadishu.[45] The US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) initially tried to capture the individuals by paying warlords in Mogadishu to abduct the men and transfer them to CIA custody. Three of the individuals most wanted by the US were Fazul Abdullah Mohamed, a national of the ComorosIslands, Abu Talha al-Sudani, a Sudanese national, and Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan, a Kenyan.[46]

Reports of a growing jihadi network in Somalia strengthened fears that the ICU would encourage Somalia to become a breeding ground for terrorism in the Horn of Africa.[47] On February 18, 2006, a few key warlords in Mogadishu formed a new alliance called the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism (ARPCT), with US backing.[48] Its aim was to capture the individuals linked to the east Africa bombings.[49]

Instead, US support for the notorious warlords who formed the APRCT backfired, generating further popular support for the ICU,[50] which extended its territorial control over a large part of central and southern Somalia and ultimately defeated the APRCT in bitter fighting in Mogadishu in June 2006.[51]

As the ICU fought the US-backed warlords in early 2006, the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia was struggling to establish itself in Somalia.[52] It set up temporary bases, initially in Jowhar town and later on in Baidoa, 250 kilometers northwest of Mogadishu, but received little international support.[53] It was only when the ICU emerged as a powerful political actor in southern Somalia that regional and international actors turned to the TFG as a more palatable form of Somali leadership.[54]

Within a matter of four months, between June and October 2006, the ICU was in control of seven of the ten regions in south-central Somalia. The Islamic Courts had restructured into the Council of Somali Islamic Courts (CSIC), with the formation of a consultative council headed by Sheikh Aweys and an executive body headed by Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed.[55] The appointment of Sheikh Aweys as one of the main leaders of the CSIC further alarmed both Ethiopia and the US, which had already placed Sheikh Aweys on a sanctions list in 2001 for his alleged links to terrorism.[56]

A June 30, 2006 video message from Osama Bin Laden urged Somalis to support the ICU and build an Islamic state, and threatened to fight the US if it intervened in Somalia.[57]

Nationalist statements from some of the ICU leadership further fuelled Ethiopian fears that the ICU hoped to unite ethnic Somali communities in neighboring northern Kenya and Ethiopia's Ogaden with Somalia. Ethiopia was also concerned by the potential impact on Ethiopia's own large Muslim and Somali population of the Islamic Courts' effort to establish political Islam in Somalia.[58]

The emergence of the ICU as a military threat in 2006 prompted the Ethiopian government to strengthen its political and military support to the TFG.[59]Ethiopia was the primary supplier of arms to the TFG and some individual warlords, but Uganda and Yemen also contributed arms and other supplies.[60]

On the other side, UN experts monitoring Somalia's utterly ineffective arms embargo in 2006 documented arms flows and supply of military materiel and training to the Islamic Courts from seven states: Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Iran, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.[61]

Following the ICU's victory over the warlords in June 2006, Ethiopia moved increasing amounts of troops and military materiel into Baidoa, the TFG stronghold, to protect it from any ICU attack.[62] The US government supported its ally Ethiopia.[63]

Peace Talks Fail: JuneDecember 2006

The rise of the Islamic Courts narrowed down the rival groups in Somalia to two: the Transitional Federal Government and the Islamic Courts Union. Appeals for peace talks mounted in an effort to combine the political legitimacy of the TFG and the stability restored to many parts of southern Somalia by the Islamic Courts.

Sudan agreed to host negotiations and on June 22, 2006, the two sides agreed on mutual recognition and further talks in Khartoum. A second round of talks under Arab League auspices in September 2006 made further apparent progress, with agreement on integrated security forces and a commitment to discuss power sharing arrangements. A third round of negotiations was scheduled for October 30, 2006, but was forestalled by Somalia's first suicide bombing on September 18, an assassination attempt on President Abdullahi Yusuf.[64] ICU leaders denied responsibility for the attack.[65]

Throughout the negotiations both the ICU and the TFG/Ethiopia continued to bolster their military preparations. In the run-up to the third round, the ICU also continued its territorial expansion, taking the strategic southern town of Kismayo in late September 2006, allegedly with a coalition of forces including advisors from Eritrea and fighters from the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) and the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF).[66]

The TFG, Ethiopia, and international government backers viewed this development with alarm, interpreting it as a prelude to an ICU attack on Baidoa, the only TFG stronghold in south-central Somalia. The Ethiopian military moved to bolster its presence not only in Baidoa, but also in Puntland and other areas of Somalia.[67]

By the time the third round of talks began in Khartoum in October 2006, the situation was at an impasse. The ICU insisted that Ethiopian troops leave Somalia and that IGAD should not have a mediating role in the talks. The TFG took the opposite position, calling for IGAD involvement and the ICU's withdrawal from recently captured areas. The talks ended in deadlock and Somalia entered a new round of hostility.[68]

The Fall of the Islamic Courts

November and December saw rising tensions between the ICU and the TFG/Ethiopians and increasing military preparations on the ground by both sides.[69] The UN Security Council on December 6 passed resolution 1725 authorizing a regional military intervention in Somalia, a development long desired by the TFG. The US-led resolution did little to reduce the tensions and in fact may have increased them.[70] Although the final resolution specified that troops from bordering countries should not be included in IGASOM, the proposed IGAD deployment in Somalia, it made no mention of the existing Ethiopian presence in Somalia and contained enough elements to be viewed as pro-TFG by the Islamic Courts and independent analysts.[71]

The ICU saw the Security Council resolution as blatant support for the Ethiopian presence. On December 12, 2006, the ICU's defense chief, Sheikh Yusuf Mohamed Siyad Indha'adde, gave the Ethiopian military in Somalia a week to withdraw or face forcible expulsion.[72] The day after the deadline passed, December 20, fighting started around Baidoa. Although the Ethiopian military were actively defending the town, they denied involvement for several days and only publicly acknowledged their role four days later.[73]

Ethiopian and TFG forces went on the offensive (TFG militia included forces from Puntland-the President's home region, the Sa'ad subclan of the Hawiye, and Rahanweyn clan militias) and quickly drove the ICU from Mogadishu and its other urban positions.[74] The resistance apparently dissolved after several battles south and east of Baidoa and in the central regions of Somalia just south of Galkayo town. Hundreds of Islamic Courts militia members and some foreign fighters who supported what they viewed as jihad[75] reportedly died under Ethiopia's superior firepower, particularly its aerial capacity.[76]

The Islamic Courts leadership left Mogadishu on December 26 as the Ethiopian forces advanced on the capital, moving south towards Kismayo and the JubaValley while many of their Somali supporters merged back into the civilian population.[77] Kismayo fell to the Ethiopians on January 1, 2007, forcing the Islamic Courts leadership and supporters further south. The outflux included dozens of foreigners who supported the Islamic Courts, some of whom had been living in Mogadishu with their wives and children.[78] Fazul Mohammed and several other individuals on the US wanted list were apparently among the exodus from Mogadishu.[79]

The US became overtly involved in the military campaign when it launched several airstrikes from AC-130 gunships in southern Somalia on January 7 and 8,[80] apparently targeting these fleeing individuals, and sent a limited number of special forces across the border.[81] The US had previously made cautious public statements supporting the Ethiopian offensive, but left the military ground operations to its Ethiopian ally. In mid- and late January, Ethiopian, US, and Kenyan security forces cooperated in a coordinated pincer operation. While Ethiopian troops pushed the fleeing Islamists and their supporters towards Ras Kamboni, at the very tip of Somalia on the Kenyan border, US navy ships positioned off the Somali coast cut off potential escapes by sea across the Gulf of Aden.[82]

As hundreds of people fleeing the conflict arrived at border crossings or in Kenya, Kenyan security forces closed the border and arrested dozens of Somali and foreigners suspected of affiliation with the Islamic Courts or with men wanted by the US (see above).[83]

Meanwhile, as the Ethiopian and US forces pursued supporters of the Islamic Courts south towards Kismayo, other Ethiopian units and TFG forces settled into military bases and buildings in Mogadishu in the first days of January 2007. These sites included strategic locations such as the new seaport, the airport, Somalia's former Presidential Palace (also known as Villa Somalia), and other strategic buildings including the former Ministry of Defense and the former headquarters of the Custodial Corps.[84] The Ethiopian military also occupied three former Somali military bases situated on the two main highways that link Mogadishu to the southern and central regions.[85]

IV. Mogadishu Under Siege: JanuaryApril 2007

By the end of January 2007 three main actors emerged in the looming military confrontation: the insurgency, the Ethiopian armed forces, and the forces supporting the Transitional Federal Government.[86]

The Ethiopian government has closely guarded details of the number of troops deployed in Somalia and statistics of casualties incurred in the fighting, but credible sources told Human Rights Watch that by early 2007 Ethiopia may have had as many as 30,000 troops in Somalia.[87] In 2006 Ethiopian military convoys carrying troops and military materiel came into Somalia regularly from Ethiopia, passing through Beletweyne town, in Somalia's Hiran region.[88] Ethiopian forces deployed in Mogadishu in early 2007 included infantry and air support.

The Ethiopians provided the backbone of the military power on the side of the TFG, which itself brought an estimated 5,000 fighters into Mogadishu. The bulk of the TFG forces consist of militias from President Yusuf's home region, Puntland, and members of the Rahanweyn Resistance Army.[89] Most of these militia forces had basic military training by the Ethiopians in Manaas and Daynuunay former military barracks in Bay region in 2006.[90] Ethiopian military officers also gave up to 3,000 newly recruited Somali government militias a few weeks of training at Balidogle airport early in 2007.[91]

While much remains unknown about its organization, membership, and leadership, it is widely believed that the insurgency consists of three groups:[92]

The first group is comprised of members of Al-Shabaab, a well-trained militia and the core of the group that led the Islamic Courts to victory during their rise to power in mid-2006. Many observers believe that Al-Shabaab consisted of between 500 and 700 fighters, largely from the Hawiye and Ogaden clans. Sheikh Hassan Turki is reportedly their spiritual leader while their operational commander is Adan Hashi Ayrow.[93]

The second group consists of members of the Hawiye clan militia who loathed the presence of the TFG leadership and the Ethiopian military in Mogadishu. These comprised perhaps the largest group in terms of numbers within the insurgency; the leadership and organizational structure of these militia is unclear.

The third group consists of disgruntled fighters and nationalists who opposed Ethiopian involvement in Somalia's affairs. It too has no known leadership.[94]

Although Hawiye fighters constituted the largest group in terms of numbers, some analysts believe that Al-Shabaab members are the backbone of the insurgency and provided discipline and strategy for all groups.[95] All the groups seem to have respected the brief ceasefires negotiated on their behalf by the Hawiye elders (see below).

Initially, many of the Somali media reports referred to the insurgency as "unidentified groups."[96] The international media described the armed groups in Mogadishu as "insurgents" or "remnants of the ICU," while by February 2007 many residents of Mogadishu referred to them as Muqaawama [the Resistance].[97]

A witness told Human Rights Watch, "The fighters were a mixture of the ICU, Al-Itihaad, Al-Shabaab, but the majority were Hawiye clan fighters. They had defenses in the areas where they fought against the government, hiding behind concrete walls. They were firing weapons-they would fire and then leave the area. They would come to the people and say, "This is our jihad, come out and join us."[98]

Hurtling Toward Conflict

Somali Prime Minister Ali Mohammed Gedi arrived in Mogadishu on December 29, 2006, the first senior TFG official to return to the capital.[99] Among his first public statements was a request to clan elders to surrender the three men wanted by the US as alleged al Qaeda affiliates.[100] In another exercise to signal the government's arrival, on January 1, 2007, he ordered that all weapons be handed over to TFG forces within three days or Mogadishu residents would face forced disarmament.[101] The order did not go down well with some of the clans in Mogadishu.[102]

Within a week of the TFG and Ethiopian army's arrival in Mogadishu the first insurgent attacks began.[103] Ethiopian and TFG forces responded by sealing off areas around the attack sites and conducting house-to-house searches.[104] The TFG also passed a three-month emergency law in parliament on January 13, 2007.[105] The provisions of the emergency law gave the TFG much wider powers and allowed President Yusuf to rule by decree.[106]

Between January and March 2007 insurgent attacks took several forms: assassinations of government officials; attacks on military convoys; and rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) or mortar attacks on police stations, TFG and Ethiopian military bases, or other locations or individuals deemed by the insurgency to be political or military targets. For instance, several hotels known to accommodate TFG officials, such as the Ambassador, Global, and Lafweyne Hotels, were repeatedly hit with RPGs and mortar rounds and were the site of attempted assassinations of TFG officials (see Map 1).[107]

The insurgency was mobile, often using hit-and-run tactics in its attacks or setting up and launching mortar rounds within minutes, then melting back into the civilian population. After an insurgent attack on a convoy or other mobile target, Ethiopian and TFG forces typically sealed off the area and conducted house-to-house searches of the area. The Ethiopian and TFG response to mortar attacks increasingly included the return firing of mortars and rockets in the direction of origin of insurgency fire.

On March 1 President Yusuf announced plans to hold a National Reconciliation Congress (NRC) on April 16,[108] but also maintained that it would not negotiate with those responsible for the attacks in the capital.[109] Many of Mogadishu's residents distrusted the TFG's capacity to implement genuine and effective reconciliation, feared potential reprisals, and were concerned about the Ethiopian presence and agenda in Somalia.[110]As insurgent attacks escalated, the government made further security announcements to the effect that the capital would be a safe venue for the meeting[111]: Deputy Defense Minister Salad Ali Jelle announced that Mogadishu would be secured in 30 days.[112] Media reports indicated that Mogadishu residents were nervous and concerned after the government's announcements. In the words of one resident, "There is fear that it will lead to more violence and more displacement if not properly handled."[113]

Many Somalis talked about the possibility of the Mogadishu situation reviving clan-based hostilities. For instance, many in Mogadishu who belong to the Hawiye clan distrusted the president, a member of the Darod clan. The Hawiye elders who later arranged ceasefire agreements with the Ethiopian military claimed in several statements that the president was instigating the hostility in Mogadishu in order to exact revenge on the Hawiye, who had been responsible for many abuses against the Darod during the civil war of the early 1990s.[114] Many Hawiye felt the security operations were aimed at disarming them, one of the biggest reasons they were opposed to the security operation announced by the deputy defense minister.[115]

The attacks and counter-attacks between the insurgency and the Ethiopian and TFG forces steadily escalated in March 2007. Insurgent tactics took a new twist when they also resorted to suicide bombings.[116]

The 1,500-member African Union force of Ugandan troops deployed in Mogadishu in early March had a limited mandate and did not become directly involved in the hostilities, although the troops occupied key positions at the airport and the TFG base at Villa Somalia.[117]

On March 21 and 22, 2007, the TFG launched its first major disarmament operation. Insurgent groups ambushed an Ethiopian and TFG convoy near the Ministry of Defense and fighting spread to several neighborhoods. At least 200 wounded people were brought to Mogadishu's hospitals.[118] More than 20 TFG militiamen were captured by the insurgency. The insurgents summarily executed several of the captured fighters and dragged their burned bodies through the streets.

A March 26 suicide attack on an Ethiopian base just outside Mogadishu, and the Ethiopian army's apparent determination to occupy more strategic locations in the city appear to have been among the catalysts for a serious escalation in the fighting.[119]

March 29 marked the start of the first round of major fighting between the insurgency and the Ethiopian forces. In the period from March 29 to April 1, several districts of Mogadishu that were either perceived to be insurgent strongholds or were located in strategic areas received the full brunt of Ethiopian offensives and bombardment (see Map 2).

Neighborhoods like Casa Populare (KPP) in the south, Towfiq and Ali Kamin around the Stadium, all along Industrial Road, and the road from the Stadium to Villa Somalia were heavily shelled or repeatedly hit by Ethiopian BM-21 multiple-rocket-launcher and mortar rounds.[120] The Ethiopian military objective appeared to be to capture the Stadium and control the main roads leading to it from the Ministry of Defense and Villa Somalia. During the course of the bombardment, the insurgency continued to use neighborhoods around the Stadium to fight and shell Ethiopian and TFG targets, and to ambush Ethiopian convoys, particularly during the battle for the Stadium.

The impact of the fighting on the civilian population was devastating. Reports from local human rights groups claimed that nearly 400 civilians were killed in the first round of fighting, although these figures could not be corroborated.[121] Local Hawiye clan elders and the Ethiopians negotiated a brief ceasefire beginning April 2, 2007, to collect the dead,[122] but shooting and sporadic rocket exchanges continued. Tens of thousands of people used the brief respite in the bombardment to flee the city.[123]

On April 18, amid spiraling conflict and tension, particularly following another suicide bombing aimed at an Ethiopian barrack, the second round of fighting began.[124] Ethiopian forces resumed heavy artillery shelling and rocket barrages, which expanded to new areas of the city, such as in the northeast around the Ramadan Hotel and the Pasta Factory. The Ethiopian aim in this offensive was clearly to take the Pasta Factory, which was thought to be an insurgent base and a strategic junction.

The second round of fighting ended abruptly on April 26 when the insurgency apparently and unexpectedly dissipated and the TFG announced victory.[125] The second bout of fighting was alleged to have claimed at least 300 civilian lives, again a figure that could not be independently verified. Although the shelling was described as even heavier than in the first round (March 29 to April 2), civilian casualties in the second round were estimated to be fewer because many people had already fled the city.

By late April the UN estimated that at least 365,000 people had fled the city.[126] In the days and weeks during and following the end of the fighting on April 26, humanitarian agencies trying to reach the displaced around Mogadishu were obstructed by TFG restrictions that included onerous limitations on aid convoys and on movement into Mogadishu. This prompted key governments such as the US and the EU to issue several statements and condemnations in late April.

Since May 2007 it has been increasingly apparent that the March and April fighting did not stem the insurgency. Roadside bombings and assassination attempts targeting TFG officials resumed in May and have continued on an almost daily basis. Attempts to convene the reconciliation conference were postponed by the TFG, first until mid-June, and then to mid-July.[127]

Many details about the specific events, intent, and acts of the warring parties remain murky. However, what is abundantly clear in reviewing the events of January to June 2007 in Mogadishu is that none of the three main warring parties-the insurgency, the Ethiopian forces, and the forces of the transitional Somali government-have made any meaningful efforts to protect civilians. On the contrary, the military strategies used by all parties during the events in Mogadishu demonstrate a wanton disregard for civilian life and property in violation of international humanitarian law. When committed with criminal intent-evident for instance in the Ethiopian area bombardments of populated neighborhoods-such violations amounted to war crimes.

Regional and international actors likewise did little to help protect the civilian population: the African Union peacekeeping mission was constrained by its mandate and was apparently unwilling to act on behalf of civilians during Mogadishu's worst fighting in 15 years, despite having some 1,500 troops on the ground. Key players with strategic involvement in the region like the US and the EU failed even to condemn the abuses as they were happening, remarking only on obstruction to humanitarian relief. As has been the case for more than a decade, the suffering of hundreds of thousands of Somali civilians was met with almost total silence.

V. International Humanitarian Law and the Armed Conflict in Somalia

International humanitarian law (the laws of war) imposes upon parties to an armed conflict legal obligations to reduce unnecessary suffering and to protect civilians and other non-combatants. It is applicable to all situations of armed conflict, without regard to whether the conflict itself is legal or illegal under international or domestic law, and whether those fighting are regular armies or non-state armed groups. All armed groups involved in a conflict must abide by international humanitarian law, and any individuals who violate humanitarian law with criminal intent can be prosecuted in domestic or international courts for war crimes.[128]

International humanitarian law does not regulate whether states and armed groups can engage in hostilities, but rather how states and armed groups engage in hostilities. Insurgency itself is not a violation of international humanitarian law. The laws of war do not prohibit the existence of insurgent groups or their attacks on legitimate military targets. Rather, they restrict the means and method of warfare and impose upon insurgent forces and regular armies alike a duty to protect civilians and other non-combatants and minimize harm to civilians during military operations.[129]

VI. Patterns of Abuses by Parties to the Conflict in Mogadishu

Indiscriminate or Disproportionate Attacks

Early in the morning of the first day, bullets started flying between the insurgents and the government; we could not even leave our homes. The militia [insurgents] that were fighting were behind our compound, I don't know if they were Al-Shaabab or Hawiye fighters. They were firing mortars and then running away. They were firing the mortars at the TFG and the Ethiopians, at the Presidential Palace and at the Ministry of Defense where the Ethiopians were based. Whenever the insurgents fired mortars at the Ethiopians, the Ethiopians responded with shells, but the Ethiopians shot them untargeted, they killed many civilians and even our animals.

-42-year-old woman from Towfiq neighborhood, describing the events of March 29, 2007[130]

While the laws of war do not prohibit fighting in urban areas, combat in Mogadishu has been conducted with little or no regard for the safety of the civilian population, resulting in massive and unnecessary loss of civilian life. All parties to the Somalia conflict have committed serious violations of international humanitarian law by using weapons in Mogadishu without discriminating between military objectives and civilians. Ethiopian forces conducted area bombardments in populated areas and failed to call off attacks that disproportionately harmed civilians. Commanders who order indiscriminate attacks knowingly or recklessly are responsible for war crimes. Casualties have been further heightened by the deployment of insurgent forces in densely populated areas and the launching of attacks from such areas. None of the parties has taken-as international law requires-all feasible precautions to spare the civilian population from the effects of attacks.

The human cost

The appalling consequences of indiscriminate attacks, the deployment of forces in densely populated areas, and the failure of all warring parties generally to take steps to minimize civilian harm is reflected in the thousands of civilians who died or whose lives were shattered by the injuries they sustained or by the loss of family members. It is also reflected in the staggering numbers of people who fled Mogadishu in March and April 2007 and in the scale of the destruction of homes, hospitals, schools, mosques, and other infrastructure in Mogadishu.

Local human rights groups and Hawiye clan elders estimated that the numbers of civilians killed in the first round of fighting in March 2007 alone ranged from nearly 400 to 1,000, with more than 4,000 others wounded.[131] Hawiye elders estimated that the second round of fighting resulted in the deaths of almost 300 civilians and wounded 587 more.[132] It is not possible to give more precise mortality figures at this stage for several reasons.

The intensity of the fighting and bombardment in late-March restricted civilian movement in and around conflict areas. As the fighting escalated on March 29, many of the dead were left in their homes, in other buildings, or even on the streets where they had been killed because it was too dangerous to collect and bury the bodies.[133] By April 2, when Ethiopian forces and Hawiye clan elders negotiated a ceasefire to collect and bury the dead, some bodies had already seriously decomposed in the heat, making identification difficult.

On April 4 and 6 the ceasefire committee of Ethiopian officials, Hawiye elders, and Red Crescent staff toured parts of the affected areas. A group of Somali Red Crescent volunteers tried to collect bodies around Ali Kamin junction and Al-HayatHospital, just south of the Stadium, which had been one of the frontlines in the previous days, but were unable to move beyond the main road into the affected neighborhoods and assess the situation more closely.[134] A credible source said that on April 4 and 6 the Somali Red Cross collected at least 24 bodies from one small section of the neighborhood around Al-Hayat, the vast majority of them civilians.[135]

According to members of the ceasefire committee interviewed by Human Rights Watch, although some of the dead were not recognizable, others were clearly identified as civilians. For instance, one body was identified by committee members as that of a "madman" who was known in the area, another was a woman who died with a prescription in her hand, and a third was a watchman who was shot while guarding private vehicles. A journalist who joined the ceasefire committee recalled a haunting sight: "I saw a mother and a child, apparently trying to flee the fighting, were caught by bullets and fell in front of their house, dead. They were holding hands."[136]

The volatile situation along the frontlines did not permit further attempts to continue collecting bodies and the operations came to a halt. The Hawiye elders estimated on April 10 that based on battlefield assessment, talking to civilians, and hospital records, more than 1,000 people had been killed in the first round of fighting alone.[137]

Given the scale of the displacement from Mogadishu and the dispersal of families across the country, it is almost impossible to methodically gather and corroborate information about dead or missing family members. In addition, many of the people who died on the spot, or were severely injured and died of their wounds before they were able to access medical care, were not registered in medical facilities or by independent sources. As one medical professional told Human Rights Watch:

Most patients die when wounded, and the worst of it is that patients can't make it to the hospital after being wounded. Most of the people who arrived at the hospital survived-less than 5 percent died once they reached the hospital. But no one can count how many people died-some just disappeared [were blown apart].[138]

Access to medical care was particularly difficult during the periods of intense fighting between March 29 and April 1 and in late-April. In addition to the constant rockets, shelling, and mortar fire, both the insurgency and the Ethiopian and TFG forces closed the roads. Thus, many wounded people had to wait until the following days to even try to access hospitals, sometimes in wheelbarrows, on donkey carts, or carried by family, friends, and neighbors.

Al-Hayat and Al-Arafat hospitals, both of which are located in the frontline areas, were also bombarded in the first days of the offensive (see below, "Attacks on Medical Facilities.") Most of the staff fled and the hospitals stopped functioning, which meant that many civilians had to undertake dangerous journeys through the city to get to functioning facilities further away, such as Medina and Kaysanay. Several Somali doctors working in the hospitals made public appeals to all parties to permit wounded civilians to access medical care, as did the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), but no one heeded these appeals.[139]

Even though an unknown number of people died from their injuries or were unable to access medical care, Mogadishu's hospitals were still inundated as the fighting escalated. The types of injuries treated in the city's medical facilities illustrate the change in the means of warfare to more destructive forms of weaponry. Gunshot wounds, by far the most common type of violence-related trauma injury in Mogadishu in the first months of the year (and in prior years), were rapidly outnumbered by shrapnel wounds as the conflict escalated.

As one medical staff member noted:

The injuries and profile of the injured are different from the usual violence in Mogadishu, which is usually injuries of individuals from light weapons. Different weapons are being used than before. At the hospitals you see injuries from tank shells, mortars, Katyusha rockets. It's urban warfare in the middle of the cityYou see whole families at the hospitals, because the shells are landing on homes. The scenes at the hospital are horrible: children with legs and arms amputated, people with intestines coming out and with head injuries.[140]

Types of weaponry used in Mogadishu

Ethiopian forces, TFG forces, and the insurgency have used weaponry without sufficient precision to minimize or avoid civilian casualties in an urban setting such as Mogadishu. Some weapons, particularly the BM-21 multiple-rocket-launchers (firing "Katyusha" rockets) used by Ethiopian armed forces, are inherently indiscriminate weapons that should never be deployed in a populated urban environment. Other indirect-fire weapons, such as mortars, can be very accurate weapons when used with spotters or other guidance systems; however, Human Rights Watch's research found no evidence of the systematic use of spotters or other guidance for the mortar rounds fired by the insurgency or Ethiopian forces, making such indirect fire attacks indiscriminate. The result was hundreds of civilian casualties in a very short period.

According to photograph and video evidence and eyewitness accounts obtained by Human Rights Watch, insurgent groups in Somalia are armed with 60, 80, 81, or 82 millimeter (mm) mortars,[141]rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), B-10 recoilless rifles, Zu-23 and Zu-50 anti aircraft guns, and various other small arms.[142] Anti-aircraft artillery mounted on the back of pickup trucks (known as "technicals") have also been a typical feature of the Somali conflict.

In 2006 the UN Panel of Experts monitoring the porous arms embargo on Somalia documented the supply to the ICU by Eritrea of large quantities of DShK (heavy machine guns), 82 and 120 mm mortars, B-10 recoilless rifles, RPGs, ZU-23 anti-aircraft ammunition, as well as large quantities of PKM machine guns and AK-47 and FAL assault rifles.[143] The November 2006 UN report also noted that "new and more sophisticated weapons are also coming into Somalia, including man-portable surface-to-air missiles such as the Strela-2 and 2M, also known as the SA-7a and 7b 'Grail,' and the SA-6 'Gainful' low-to-medium altitude surface-to-air missile."[144]

While the ICU no doubt used some of this weaponry during fighting with the Ethiopian forces in December 2006, it is very likely that much of it was left in Mogadishu when the ICU fled. The ICU had confiscated many arms from Mogadishu militia when it took control in June 2006, but clan elders apparently demanded that the ICU return confiscated arms when the Ethiopians were approaching.[145] The insurgency would also have had access to independent arms traders in Mogadishu's Bakara market in the early months of 2006.[146]

By January 7, within 10 days of the arrival of Ethiopian and TFG forces in Mogadishu, armed groups began attacking them with small arms, mortars, and other weaponry. By late March the attacks expanded to include suicide bombings and, in later months, the use of remotely-controlled explosive devices.

The Ethiopian armed forces have used BM-21 multiple barrel rocket launchers firing Katyusha-type rockets, 120 mm mortars, T-55 tanks firing 100mm shells, and M-30 and D-30 artillery in the course of their attacks.[147] The Ethiopian military also used Mi-24 helicopter gunships in the first two days of the March offensive, which fired into neighborhoods of Mogadishu. Human Rights Watch's research has not been able to verify what types of weapons were used on the helicopter gunships, but these gunships have an internal 12.7 machine gun and also likely used 57 or 80 mm rockets. The Ethiopian army ceased using the helicopters after insurgents shot one down on March 30.[148]

Human Rights Watch was often able to determine the weapons used in a particular attack because civilians in Mogadishu became expert at identifying different weaponry by their specific characteristics. Dozens of eyewitnesses consistently named specific weapons that were used, and accurately described to Human Rights Watch the sound or sight of different types of weaponry even when they were unable to name the exact type of weapon. For instance, individuals repeatedly named BM-21 rockets or Katyushas, which they called "Bii-em" or described as "whistling" due to the sound they made when launched and the loud noise upon impact.[149]

Numerous eyewitnesses accurately told Human Rights Watch that mortars, by contrast, were silent in their flight. As one person noted, "Katyushas, you know the sound, it sounds like 'whooooo,' and then a thud. But with mortars you don't hear anything."[150]

Indiscriminate attacks by Ethiopian forces

When the insurgency launched rocket or mortar attacks, the Ethiopians responded with barrages of rockets, artillery, and mortar shelling of areas of Mogadishu perceived to be the areas of origin of the attack or strongholds of the insurgency. Eyewitnesses to the fighting in March repeatedly told Human Rights Watch that the Ethiopian barrages came from Ethiopian bases located in the former Ministry of Defense building, Villa Somalia, the Custodial Corps headquarters, Kabka (a former repairs factory for the Somali military), and, in April, from the Mohamoud Ahmed Ali Secondary School and the former headquarters of the Somali Police Transport (see Map 2). Many of these locations are two or more kilometers from the neighborhoods they were targeting, distances that would require a spotter in the air or on the ground for mortar shelling to be used with any degree of precision.

The Ethiopian rockets were inherently unable to target specific military objectives. Residents of Mogadishu described patterns of rocket barrages that match the use of BM-21 multiple barrel rocket launchers. The use of BM-21s by the Ethiopian forces was confirmed not only by eyewitness descriptions of the weapons by name but also by description of the sounds they made when fired.

There is strong evidence that the indiscriminate bombardment of populated neighborhoods by Ethiopian forces was intentional. Commanders who knowingly or recklessly order indiscriminate attacks are responsible for war crimes. In Towfiq, Hamar Jadid, and Bar Ubah neighborhoods, eyewitnesses reported that the Ethiopian BM-21 rockets and heavy artillery often landed in systematic patterns, equidistantly, and at regularly spaced time intervals. In Towfiq, for instance, Ethiopian rockets landed 10-20 meters apart, while in Hamar Jadid they were sometimes 40 meters apart.[151] One man with a military background told Human Rights Watch, "The Ethiopians would shell on a line-start with one area and move to the next, and the next day they started all over again, the same way."[152] Another man observed, "The shells were coming in a sustained format: each shell fell 40 meters from the other. In some areas, you would find 10 houses next to each other destroyed."[153]

According to military experts this type of shelling is typical of area shelling where troops move the coordinates from one target to the next, going down a grid pattern. Area bombardment is fundamentally inappropriate as a strategy to target a mobile insurgency in a densely populated civilian setting. It constitutes an indiscriminate attack, which is a serious violation of international humanitarian law. This type of attack on populated neighborhoods is indicative of criminal intent to blanket an entire area rather than hit specific military objects-evidence of a war crime.

Indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks by the insurgency

Although the insurgency generally targeted military objectives such as Ethiopian and TFG military units and convoys, there frequently were civilian casualties. Human Rights Watch conducted an analysis of some of the reported attacks by the insurgency between January and March 2007. The numbers presented here are rough estimates based on media and other reports, and are not a conclusive analysis of the impact of insurgent attacks on civilians, and Human Rights Watch was not able to investigate and confirm details of many of the attacks. However, these estimates provide a preliminary basis for assessing the impact of such attacks on civilians. Our analysis covered more than 80 attacks that appeared to target Ethiopian and TFG forces, police and police stations, and military objectives such as the airport and seaport where Ethiopian and TFG forces were located. In the period of January to March, approximately 50 civilians died and up to 100 were injured from the attacks; 20 attacks generated the majority of the deaths. In terms of the impact on civilians, one of the clear conclusions is that the insurgency's attacks, particularly its use of mortars, have at times been indiscriminate or caused disproportionate civilian casualties compared to the expected military gain.

Insurgency attacks on military targets such as military convoys or bases in crowded civilian areas were sometimes conducted without any apparent effort to minimize the effects of such attacks on civilians. While Ethiopian or TFG forces may themselves have failed to take all feasible steps to minimize the risks to the civilian population, such as by establishing bases in crowded civilian neighborhoods, this did not relieve insurgent forces of the obligation to minimize civilian harm when conducting attacks. (See also below, "Deployment in populated areas.")

Many mortar attacks launched at military targets appear to have been poorly targeted because spotters were not used. These mortar attacks failed to hit military objectives, frequently killing and injuring civilians instead. Photo and video evidence of mortar fire by the insurgency confirms that the weapons were typically fired without guidance. A few examples demonstrate these types of attacks:

- On February 7, 2007, suspected insurgents fired a mortar shell that struck a Qur'anic school in south Mogadishu. Medical officers recorded seven deaths.

- On February 14 insurgents fired at least five mortar rounds at or in the direction of Ethiopian forces based in Hodan (possibly DigferHospital), the seaport, and Bakara market. A shell apparently aimed at the seaport landed near a group of children who were swimming. One child died and six were wounded. In total, the five shells killed at least four civilians and wounded 17 people, all of whom are believed to be civilians.[154]

- On March 8 insurgents targeted an African Union convoy with a rocket propelled grenade but missed as it passed a busy junction, two days after Ugandan AU troops arrived in the city. According to press reports, 10 civilians died from the explosion and subsequent gunfight.[155]

- On March 18 the insurgency launched more than 10 simultaneous mortar attacks on the seaport and former intelligence headquarters. The mortar attack on the seaport hit a restaurant, killing one person and wounding at least three other civilians.[156]

As the fighting intensified in late-March, so did the bombardment of neighborhoods like X-Fiyore, just behind Villa Somalia. A resident of X-Fiyore told Human Rights Watch,

The first madfa' [Somali word for artillery that Somalis often use to describe a weapon making a loud noise] that hit the area came during the Stadium fighting. Four madfa' landed; it was the second day of the fighting [March 30] around 1 p.m. One man was injured. His name was Dalab, around 65 [years old]. He was taken to Medina hospital. [Others who] died during the stadium battle in Sheikh Sufi neighborhood were two children, age seven and eight years. Both of them were boys. [The children's aunt] who was visiting the family was injured. This happened on Monday, April 2, 2007. It happened when a mortar hit their house. The missiles that were landing in the area continued. On Thursday, April 5, 2007, three mortars landed in the neighborhood, wounding two sisters [Halimo and Amina Hussein, age around 34 and 35]. Amina's six-day-old baby girl was killed in the same incident. This happened around 2 p.m. On the same day, two other mortars landed on a house-one in the house and the other just beside it. The house belonged to a friend, Mohamoud Abshir Shiine. Eight people were injured in this incident. Just the day before we left, another mortar landed in front of the former national museum. A prominent elder in the area-Sheikh Ali, around 55 [years old], who lived in the museum, was killed. He just came back from prayers at the mosque, around 3 p.m., and was sitting outside when the mortar landed near him. The shell cut him to pieces. Another elder ran towards him in order to help but a second mortar landed and cut off both of his legs. They had both came back from Sheikh Abdilqadir Mosque. You could only see dust and shrapnel at the scene.[157]

Human Rights Watch cannot confirm which group was responsible for these attacks.However, the area is close to Somalia's Presidential Palace which has been a constant target for the insurgent groups.

One eyewitness who lived close to the Ambassador Hotel described to Human Rights Watch attacks that may have violated the prohibition against indiscriminate or disproportionate attacks:

I could not tell the type of weapons used but our area was a constant target for bombings. One of the explosions went off around 100 meters from the Ambassador Hotel. Two people were killed in this attack. It happened between 4 and 6 p.m., I can't remember the exact date. Another explosion followed another day at around 7 p.m., killing one man instantly; a second man died of his wounds. Both men were civilians. These explosions seemed to have been targeting a Corolla car transporting a government official.[158]

Deployment in Populated Areas

International humanitarian law requires that all warring parties must to the extent feasible avoid locating their forces within or near densely populated areas, and must remove civilians under their control from the vicinity of military objectives. They must never intentionally use civilians to shield themselves from attack or to carry out attacks.

The insurgency groups regularly used several populated neighborhoods to launch mortar and other attacks. Residents of several of these areas described to Human Rights Watch the nature of attacks and counter-attacks in the period leading up to the first round of fighting in late-March 2007.

A 33-year-old woman who lived in Laba-dhagax neighborhood, near the Stadium, told Human Rights Watch that insurgent groups had been using her neighborhood to launch attacks and that the Ethiopians responded with BM rockets:

The Muqaawama used to bring their madfa' in sacks and reassemble [them] on the scene. When the Muqaawama arrived, they used to give orders to people to close their doors and put hands over their ears. They used to come in the evening. They used to launch up to 20 rounds of madfa' at a time. Sometimes they used to fire madfa' just opposite my house; they have done this around six times. When this happened we used to vacate the house and take refuge in a concrete building nearby. Sometimes the Muqaawama fired up to 16 madfa' and the Ethiopians responded with six rounds of BM missiles.[159]

A 45-year-old woman living in the Arwo Itko area between Hamar Jadid and Bar Ubah also described insurgency fighters firing mortars from the area. She noted that on the night the Presidential Palace was first targeted on January 19, nine rounds were fired from the area. Ten rockets came in by return fire.[160]

A resident of the Bar Ubah neighborhood in Hawlwadag district explained the tactics used by the insurgency when firing mortar and artillery shells from within the residential areas:

They used to fire madfa' from the area and then run away. They have done this continuously throughout [the conflict]. We saw them hiding themselves. They had their eyes and mouth masked. They would come, fire a single madfa' and run away immediately. They would go somewhere else in the neighborhood and do the same.[161]

Ethiopian and TFG forces may also have violated the prohibition on deploying a military asset near a densely populated civilian area by placing one of their central bases in Villa Somalia. Action should have been taken to transfer civilians from the vicinity of the base.

Insurgency abuses in response to civilian protests

In some neighborhoods, local residents tried to stop the insurgency from using their areas as locations to launch mortar rounds or stage other attacks. A resident of Wardhigley district said, "They were just 20 people without cars, moving around. They would tell the people there that they come to fight so we could choose to leave. Some elders tried to speak to them to tell them to stop fighting in the area, but they didn't respect them, saying it was their duty to fight the Ethiopians."[162]

By late February, some neighborhoods set up vigilante squads to resist insurgent attempts to use the areas as launch sites for attacks. The underlying motive was to deter Ethiopian and TFG counter-attacks or reprisals on the neighborhoods. According to news reports, some of the areas that applied this strategy included Tawakal in Yaqshid district, Gubta, Hamar Jadid and Wardhigley districts, and NBC neighborhood in Hodan district.[163]

In a few cases investigated by Human Rights Watch, the insurgency apparently summarily executed individuals who resisted the use of their neighborhoods as launch sites or who were suspected of being informers. A photograph taken on April 24, 2007, appears to show two insurgent fighters in the process of shooting an unarmed man lying on the ground who was suspected of being an informer.[164]

The February 21 killing of Abdi Omar Googooye, the deputy commissioner of Wadajir District (see below, "Deliberate killings of public officials"), was allegedly due to his involvement in a campaign to set up neighborhood guards and stop the area from being used by the insurgency to launch attacks.[165] In Bar Ubah neighborhood of Hawlwadag district, a resident said the "Muqaawama" murdered four members of the neighborhood guards-two who were killed in Bar Ubah and two others killed in the Black Sea area. She could not remember the dates or other details of the killings, and Human Rights Watch could not independently confirm the information.[166] A woman living in the Arwo Itko area between Hamar Jadid and Bar Ubah told Human Rights Watch that when a local vigilante group in Hamar Jadid tried to confront the armed insurgency, the latter summarily executed six of them.[167] Human Rights Watch learned of these cases in two independent interviews, but was unable to obtain further details of either allegation.

Attacks on Medical Facilities

The Ethiopian military bombardment in March and April hit several hospitals during the course of the fighting in Mogadishu, causing some hospitals to suspend their provision of medical care at a time when this care was desperately needed by hundreds of people. The protection of hospitals and other medical facilities is a bedrock principle of international humanitarian law. The Second Additional Protocol of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol II), on the protection of medical units and transports, which is reflective of customary international law, states,

1. Medical units and transports shall be respected and protected at all times and shall not be the object of attack.

2. The protection to which medical units and transports are entitled shall not cease unless they are used to commit hostile acts, outside their humanitarian function. Protection may, however, cease only after a warning has been given setting, whenever appropriate, a reasonable time-limit, and after such warning has remained unheeded.[168]