Dignity on Trial

India’s Need for Sound Standards for Conducting and Interpreting Forensic Examinations of Rape Survivors

I. Summary and Recommendations

The clerk told me a male doctor will conduct the test [forensic examination] and asked me whether that was ok. I said “yes.” But other than that, I did not know what they were going to do. I was so scared and nervous and praying all the time: “God, let this be over and let me get out of here fast.” I did not even know it was going to be like a delivery examination [an internal gynecological examination].

—Sandhya S. (name changed), adult rape survivor, Mumbai, August 2, 2010.

For decades, survivors of sexual violence in India have endured criminal justice and health care systems that pay scant attention to their needs and rights. But in December 2009, the Indian government—spurred by the Indian women’s rights movement, as well as by children’s and health rights activists—initiated a process to review and change the laws governing sexual violence, an important first step toward protecting the rights of survivors of such abuse. Of critical importance will be ensuring that any new laws or amendments build on good practices from both inside and outside the country, adhere to international standards and laws, and bring about changes in a transparent and consultative manner. Changes in laws alone will not ease the path to justice for survivors of sexual violence. Once laws and policies have been put in place, the Indian central and state governments must also ensure that these laws are adequately resourced and implemented.

Part of this should involve reforming and standardizing the way that health care providers manage cases of sexual assault. Health providers have a dual role when it comes to responding to sexual violence. They must provide therapeutic care to survivors—including addressing their sexual, reproductive, and mental health problems—and also play a critical role in the response of the criminal justice system, by collecting forensic evidence for use during any criminal investigation and prosecution. However, according to Indian health rights activists who have assisted survivors and studied their treatment in the health care system, doctors usually prioritize the collection of forensic evidence, and often insist on filing a police complaint as soon as survivors approach them for medical care, which can intimidate survivors and discourage them from pursuing treatment. Health providers often spend little, if any, time on essential therapeutic care.

There is an urgent need for a holistic policy and program that directs health providers’ attention to the needs of survivors after an assault. Services geared toward survivors require structural changes so that it is easier to register complaints or access services. In the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada, crisis intervention centers staffed by professionals provide integrated services with a special focus on the therapeutic needs of survivors. Similar centers are necessary in India.

The Finger Test

Sexual violence is, disturbingly, a growing trend in India. Between 1990 and 2008, reported rapes soared by 112 percent nationwide, according to the National Crime Records Bureau, while cases of molestation and sexual harassment also increased between 2001 and 2008 (the latest year for which data is available). Such figures likely understate the problem. Many survivors of sexual violence do not report attacks because they fear ridicule or retribution, as well as assumptions that victims of sexual assault are “bad,” “loose,” or otherwise responsible for the attack. Survivors and their families may also be reluctant to subject themselves to the criminal justice system, which offers no victim and witness support and protection program, and which may inflict additional trauma.

Not least of the disincentives for reporting abuse is the prospect of undergoing a forensic examination. Evidence collection techniques are by no means standardized and are frequently difficult. Too often, survivors must make grueling trips from one hospital or ward to another, and receive multiple examinations at each stop. Medical workers frequently collect evidence inadequately or insensitively, and it may then be lost, poorly stored, or subject to processing delays, rendering it unusable. At trial, judges often lack adequate information to interpret the medical evidence.

Indian criminal law does not require corroboration by forensic evidence to secure a conviction for rape, yet in practice, such evidence plays a critical role. Lawyers and activists say that the seriousness with which police investigate a complaint of rape usually depends on the manner in which a doctor collects and reports forensic evidence, and judges frequently give this evidence significant weight. A rape survivor who endured considerable indignity to provide evidence may see the perpetrator walk free if the evidence was improperly collected, stored, or reported.

This report does not present the whole range of problems that survivors of sexual violence encounter in their interactions with the Indian criminal justice and health care systems. Nor does it address all the problems inherent in collecting forensic evidence. Instead, it discusses the problems posed by one of the most archaic forensic procedures still in use: the finger test—a practice where the examining doctor notes the presence or absence of the hymen and the size and so-called laxity of the vagina of the rape survivor. The finger test is supposed to assess whether girls and women are “virgins” or “habituated to sexual intercourse.” Yet it does none of this.

Contrary to common misconceptions, the hymen is a flexible membrane that partly covers the vaginal opening and does not seal it like a door. Hence the notion that there was no rape if there is no “broken” hymen is false. Conversely, a hymen can have an “old tear” and its orifice may vary in size for many reasons unrelated to sex, so examining it provides no evidence for drawing conclusions about “habituation to sexual intercourse.” Furthermore, the question of whether a woman has had any previous sexual experience has no bearing on whether she consented to the sexual act under consideration. And the finger test itself can result in further trauma to the survivor, whose dignity is generally ignored. In effect, it is a procedure that without informed consent would amount to sexual assault.

Unscientific, inhuman, and degrading, the finger test also has no forensic value, according to forensic and medical experts from India and outside the country. It is also legally irrelevant: the Indian Supreme Court, whose decisions are nationally binding, has ruled that finger test results cannot be used against a rape survivor, and that a survivor’s “habituation to sexual intercourse” is immaterial to the issue of consent at trial. Amendments to Indian law have also prohibited cross-examining survivors about their “general immoral character.” The number of finger test exams has fallen and courts have become less likely to draw conclusions about a survivor’s “habituation to sexual intercourse” as a result of these developments. Yet the finger test is still pervasive in many hospitals in India, and more needs to be done to reform India’s approach to sexual violence in general, and to eradicate finger testing in particular.

At least three leading government hospitals in Mumbai, including one where more than a thousand rape survivors are examined every year, continue to conduct the finger test. In 2010, the Delhi and Maharashtra governments introduced new forensic examination templates for rape survivors, which, among other things, seek details about the hymenal orifice size of the survivor. And anecdotal evidence suggests that the practice occurs elsewhere in India.

Since doctors tend to seek blanket consent for the forensic examination as a whole, and not to mention the finger test specifically, many survivors have little understanding of what the test entails; what information is collected for what ends; and the implications of refusing to undergo a forensic examination or any part of it—including the risk of appearing to hide information. Nonetheless, findings may be presented in court. Defense counsel may use the findings of the finger test to shake the morale of survivors, and challenge or discredit their testimony. In some cases, defense counsel even use the findings to claim that sexual intercourse was consensual. Many judges consider the results of the finger test at trial and appellate stages. In theory, an allegation that a rape survivor is “habituated to sexual intercourse” is not by itself grounds for an acquittal. But courts across the country have at times used this as evidence to assert that the rape survivor had “loose” or “lax” morals.

The common use of the finger test shows that many doctors, police officers, lawyers, judges, and others do not understand what constitutes rape, what elements could help establish that rape has occurred, and what facts are irrelevant to determining whether rape has occurred. It underscores the pressing need for uniform nationwide guidelines for forensic examinations that respect survivors’ rights to health, consent and dignity, and for scientific, relevant and accurate information to be presented in courts, rather than outdated material gleaned from textbooks or old-fashioned medical practices. Doctors, police, prosecutors, and judges should all work together to stop the finger test from being administered, and to standardize evidence collection to protect the rights of survivors.

India is party to several international treaties that obligate its government to ensure that all forensic procedures and criminal justice processes respect survivors’ physical and mental integrity and dignity. Guidelines issued by the World Health Organization (WHO) for examining survivors of sexual violence state that forensic examinations must be minimally invasive and that even a purely clinical procedure such as a bimanual examination[1] is rarely medically necessary after sexual assault. In the case of prepubescent girls and boys who are victims of sexual abuse, the WHO guidelines say that “most examinations” should be “non-invasive and should not cause pain,” and that “speculums or anoscopes and digital or bimanual examinations do not need to be used in child sexual abuse examinations unless medically indicated.” The guidelines further caution: “consider a digital rectal examination only if medically indicated, as the invasive examination may mimic the abuse.”

The Indian government should provide additional information to doctors, police officers, prosecutors, and judges. The government should issue uniform guidelines specifying how forensic evidence can be collected in a manner that respects survivors’ rights, and also what types of forensic evidence should be collected. In addition, the Indian government should use its law reform process to prohibit the finger test, as well as the inclusion of opinions about whether survivors are “habituated to sexual intercourse”, from all forensic examinations. Yet creating new laws and policies related to forensic examination is not enough. The Indian central and state governments must also ensure that they are adequately resourced and implemented.

As an important part of this, the government should conduct training and sensitization programs to familiarize doctors, police officers, prosecutors, and judges with the latest legal and scientific methods of evidence collection that respect survivors’ rights. Hospitals need multi-disciplinary centers, adequately equipped and staffed with trained and sensitive personnel, to provide integrated and comprehensive services for survivors of sexual assault.

To fulfill its obligations, the Indian government can draw on the experience of other countries, and also build on good domestic examples. For instance, South Africa provides specialized training for medical students on how to treat and examine survivors, while the United Kingdom provides detailed theoretical and on-the-job two-month training for all doctors who interact with, and examine, survivors of sexual violence. The United States and Canada also have forensic nurses who specialize in such examinations. In parts of the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada, there are also specialized sexual violence crisis intervention centers equipped and staffed with trained professionals drawn from various backgrounds and able to provide integrated services with a special focus on the therapeutic needs of survivors. Within India, the Mumbai-based nongovernmental organization Centre for Enquiry Into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT) has developed a detailed forensic examination protocol accompanied by an instruction manual, currently used in two Mumbai hospitals, that explicitly states that the two-finger test should not be conducted.

Recommendations

To the Indian Central and State Governments:

In order to ensure that the current review processes bring about concrete change in how the health and criminal justice systems approach survivors of sexual violence in general, and rape survivors in particular:

- Prohibit the finger test and its variants from all forensic examinations of female survivors, as it is an unscientific, inhuman, and degrading practice, and

- Instruct doctors not to comment on whether they believe any girl or woman is “habituated to sexual intercourse”.

- Instruct all senior police officials to ensure that police requisition letters for forensic examinations do not ask doctors to comment on whether a rape survivor is “habituated to sexual intercourse.”

- Communicate to trial and appellate court judges that finger test results and medical opinions about whether a survivor is “habituated to sexual intercourse” are unscientific, degrading, and legally irrelevant, and should not be presented in court proceedings related to sexual offences.

- Devise special guidelines for the forensic examination of child survivors of sexual abuse to minimize invasive procedures. Emphasize that tests that risk mimicking the abuse should be conducted only when absolutely medically necessary to determine if injuries need therapeutic intervention. Ensure that any test is only carried out with the fully informed consent of the child, to the extent that is possible, and the consent of the child’s parent or guardian, where appropriate.

- Develop, in a transparent manner and in consultation with Indian women’s, children’s, and health rights advocates, doctors, and lawyers, a protocol for the therapeutic treatment and forensic examination of survivors of sexual violence that adheres to:

- The procedural and evidentiary decisions pronounced by the Indian Supreme Court and international laws.

- Standards and ethics issued by the World Health Organization.

- Organize, in consultation with national and state judicial academies and experts on women’s, children’s, and health rights, special programs for trial and appellate court judges on proceedings related to rape and other sexual offenses, and on the rights of survivors.

- Organize, in consultation with state police academies, judges, and experts on women’s, children’s, and health rights, special programs for police related to investigating and prosecuting sexual offenses, and on the rights of survivors.

- Organize, in consultation with judicial and other officers in charge of prosecution services and experts on women’s, children’s, and health rights, special programs for prosecutors on proceedings related to rape and other sexual offenses, and on the rights of survivors.

- Develop, in consultation with women’s, children’s and health rights experts in India, multidisciplinary centers in at least one government hospital in every district of the country (or in an alternative appropriate population-to-distance norm), staffed with trained personnel and equipped to provide integrated, comprehensive, gender-sensitive treatment, forensic examinations, counseling, and rehabilitation for survivors of sexual violence.

- Develop and introduce, in consultation with lawyers and experts on women’s, children’s, and health rights, a mandatory gender-sensitive training module for medical students on treating and examining survivors of sexual violence.

- Form a committee to review, update, and revise medical jurisprudence textbooks to ensure the inclusion of the latest positions in Indian law on procedure and evidence related to sexual violence.

- Consult with women’s rights and children’s rights activists and lawyers to ensure that their concerns regarding forensic examinations in sexual violence cases are addressed in the final version of the Perspective Plan for Indian Forensics. Before finalizing the plan, the government should also study lessons learned from other jurisdictions about how integrated medical and forensic services are provided in a gender-sensitive and timely manner.

II. Methodology

This report is based on research that Human Rights Watch conducted between April 10 and August 10, 2010, in Delhi and Mumbai.

A researcher conducted interviews, both in person and on the phone, with 44 people, including doctors, health rights activists, women’s rights activists, prosecutors, other lawyers, judges who have served in criminal trial courts or on criminal appellate benches, and parents of survivors of sexual violence, in Mumbai and Delhi. Most of the health rights activists and doctors interviewed had studied health system responses to sexual violence and are advocating for a uniform gender-sensitive examination protocol for rape survivors, along with training for doctors involved in these examinations. The lawyers Human Rights Watch interviewed included some recommended by women’s rights and children’s rights activists, who have extensive experience in the prosecution of rape or child sexual abuse. Five of the forty-four interviewees were from parts of India outside Mumbai and Delhi, and were interviewed because they had experience working with survivors of sexual violence. Three of the interviewees were from countries other than India, namely South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The interviews were conducted in English or Hindi and lasted between 30 minutes and an hour. Human Rights Watch used pseudonyms where interviewees wished their identities to be protected.

Due to the difficulties involved in locating survivors willing to talk about their experiences, Human Rights Watch was able to speak with only one survivor, who had indicated to her lawyer that she was willing to talk to the researcher about her forensic examination and deposition to the police.

Mumbai and Delhi were chosen as investigation sites because they rank first and second among cities across the country in the number of registered cases of rape.[2] In addition, both Delhi city and Maharashtra state (the capital of which is Mumbai) have recently witnessed developments related to sexual violence. In June 2010 the Maharashtra state government issued a set of guidelines related to the forensic examination of rape survivors that reinstate questions about the hymen and the number of fingers that can be admitted into the hymenal orifice. Similarly, in early 2010 the office of the Director General of Health Services in Delhi introduced a template for the forensic examination of rape survivors at government hospitals that seeks information about the size of the hymenal orifice and asks doctors to comment on whether the survivor is “habituated to sexual intercourse.” Many health rights and women’s rights activists regard these as a setback to women’s rights.[3]

Mumbai and Delhi have also seen some positive developments related to the treatment and examination of rape survivors. For example, the Mumbai-based Center for Enquiry Into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT), together with doctors from across the country, has developed a detailed template and instruction manual for the forensic examination of survivors of sexual violence. The document clearly indicates to doctors what information is relevant for such an examination, outlines situations in which it is appropriate to note injuries to the hymen, and describes how these must be recorded—directives that show doctors how to conduct examinations in a manner that respects a survivor’s privacy and dignity. The instruction manual also explains that the two-finger test is no longer admissible in court, and that doctors should not use the test to assert findings or render medico-legal opinions.[4] In Delhi, the government is also slowly beginning to pay greater attention to the health needs of and forensic examination protocols for rape survivors: 2009 High Court guidelines, for example, outline what different actors, including police officers, prosecutors, and doctors, should do to assist survivors of sexual violence. The High Court has also formed a committee headed by Justice Gita Mittal to oversee the implementation of all guidelines related to sexual violence against adults and children.[5]

In April 2010 Human Rights Watch attended a Mumbai conference that gathered women’s rights activists from across India to discuss the proposed Criminal Law (Amendment) Bill, 2010, which seeks to introduce a new definition for “sexual assault” and also to amend certain procedural and evidentiary rules for related criminal trials. The women’s rights activists present prepared a set of recommendations to be shared with the government, including one that unanimously reiterated their longstanding demand for the prohibition of the finger test as part of forensic examinations of rape survivors.

Human Rights Watch also analyzed around 160 judgments—153 from High Courts across the country and seven Supreme Court judgments—rendered during the last five years in order to determine how medical opinions based on the finger test were used in courtroom proceedings on rape beyond Mumbai and Delhi.

Terminology and Scope

The phrase “sexual violence” is used in this report to refer to all forms of sexual violence, both penetrative and non-penetrative. In addition, since India does not have an overall definition of sexual violence, the terms “sexual offense,” “sexual violence,” “sexual assault,” and “rape” are used in this report interchangeably. India currently only defines four sexual offenses: rape (as penile penetration),[6] an “unnatural offence—carnal intercourse against the order of nature with man, woman, or animal,”[7] which in practice is also used to punish child sexual abuse, “outraging the modesty of women,” and “insulting the modesty of women,” which are used to punish non-penetrative sexual offences.[8] Indian law does not recognize the offence of marital rape, and a man cannot by law be prosecuted or punished for raping his wife.[9]

Boys, men, and transgender persons are also victims of sexual assault, and they face some similar and some different problems.[10] While this report discusses the need for specialized and sensitive procedures of examination for all children and adults who face sexual violence or abuse, it specifically focuses on female survivors of sexual violence.

The phrase “forensic examination” is used in this report to describe all parts of the medical examination that doctors conduct on survivors of sexual violence, including the internal gynecological examination, and “forensic evidence” or “medico-legal evidence” is used to describe all evidence generated by a forensic examination. “Medico-legal opinion” is a phrase commonly used in India to refer to the medical opinions written by doctors after examining a rape survivor, which have legal evidentiary value. “Prosecutrix” is a term used in India to refer to a survivor of sexual violence during trial.

Textbooks and doctors describe finger test findings using the terms “hymenal orifice,” “vaginal orifice,” and “vagina” interchangeably, and Human Rights Watch has reproduced them as such.

III. Background

Sexual violence is, disturbingly, a growing trend in India.[11] Between 1990 and 2008, reported rapes soared by 112 percent nationwide, according to the National Crime Records Bureau, while cases of molestation and sexual harassment also increased between 2001 and 2008 (the years for which data is available). Such figures likely understate the problem.[12] Many victims of sexual violence do not report attacks or follow through with prosecution due to fear of ridicule or retribution, pervasive myths about sexual violence,[13] and a criminal justice system that offers no protection or support to victims and witnesses.[14] The absence of a comprehensive definition of sexual violence in Indian law[15] has also hindered the prosecution of various sexual offences, resulting in acquittals or inadequate punishments for convicted criminals.[16]

Health care providers play a crucial dual role in the response to sexual violence. They provide therapeutic care after an assault and yet they also assist in any criminal investigation. On the one hand, they must provide medical treatment for any injuries suffered by the survivor, address any adverse psychological, sexual, and reproductive health consequences of the assault,[17] and can also provide referrals to legal and social welfare services.[18] On the other hand, doctors conduct forensic examinations of survivors seeking evidence of a crime, and may later interpret this evidence as witnesses in court. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that health care and forensic services be provided at the same time, and by the same person, to reduce the potential for duplicating questions and retraumatizing the survivor of assault. The WHO guidelines state that the health and welfare of a survivor of sexual violence is “the overriding priority” and that the provision of forensic services cannot take precedence over health needs.[19]

In countries such as Canada, South Africa, the United States, and the United Kingdom, one-stop multidisciplinary centers provide survivors of sexual violence with integrated services, including physical and psychological care. Staff members at such centers offer medical aid and psychological counseling using standard treatment and examination protocols. They are trained to be sensitive to the needs of assault survivors and to treat them without bias or prejudice. In some cases, survivors may even file a criminal complaint at the center, giving a statement in a manner that respects privacy and dignity in order to launch a criminal investigation. Many of these centers are also linked to other specialized support services, including social welfare and legal aid.[20] Such centers, governed by standard treatment and examination protocols, can play a key role in ensuring adequate standards of care and supporting the collection of forensic evidence for survivors of sexual violence. They can also serve as an educational resource for health care workers, police, lawyers, and judges.[21] While this report focuses on sexual violence, this kind of integrated service could also extend care to survivors of other gender-based violence, such as domestic violence and acid attacks.

India currently has no nationwide policy or guidelines to govern the medical treatment and forensic examination of survivors of sexual violence nor the provision of psychosocial support and other specialized services to them.[22] Women’s rights groups have urgently pressed for a sensitive, holistic approach to treating and examining survivors of sexual violence. Almost all the doctors who spoke with Human Rights Watch said that the Indian central and state governments need to introduce a program of therapeutic care for survivors of sexual violence and their families.[23] Doctors and activists who have analyzed medical responses to rape survivors in India say that the categorizing of such survivors as “medico-legal cases,” has led most doctors to treat them as “walking, talking crime scenes,” invariably focusing solely on forensic examination.[24]

The psychological and social consequences of sexual violence can play out in myriad and unexpected ways. A trial court judge told Human Rights Watch that rape survivors in her court often grapple with the psychological fallout of the violence without any support and some have become suicidal.[25] A lawyer assisting a 14-year-old survivor of gang rape reported that the girl’s father abandoned the family, blaming the mother for what had happened.[26] In another case, the parents of a six-year-old survivor of rape told Human Rights Watch that since the rape, their older daughter had dropped out of school and her fiancé had broken off their engagement; the girls’ father, unable to focus on his work, had quit his job.[27] Another lawyer helping a 15-year-old rape survivor said that the rape had left her pregnant, she had delivered a baby and now her father was trying to arrange for her to marry her rapist (not an uncommon practice in India).[28]

Despite the layers of trauma, many social workers and health rights activists who have assisted rape survivors told Human Rights Watch that police and hospital staff often treat survivors, especially older girls and adults, with little or no sensitivity, adding to their grief. For instance, Dr. Rajat Mitra of Swanchetan, a Delhi-based nongovernmental organization that provides emotional and psychological support to thousands of rape survivors in different parts of India, said:

In cases of very young girls—girls below [age] 12 or 13—they [police officers and hospital staff] believe it is a case of sexual abuse. But if they are older, then they believe that the girl is trying to falsely frame someone. Their belief changes the way they address the survivors. They are very rude and disrespectful. They will say things like, “Why are you crying?” “You have only been raped.” “You are not dead.” “Go sit over there.” And order them around.[29]

Recollecting what she had seen accompanying survivors to hospitals, another social worker said, “In one case, the doctor said something like, ‘You there! You are so dirty! Don’t sit on that chair!’ because she had come immediately after the assault, and had blood and soiled clothes.”[30] Discussing another of her cases, she said,

In another gang rape case, the survivor was made to sit for six hours after the medical examination inside the labor room without even being allowed to change out of her bloodied clothes and shower. When she saw me, she asked me if there was a way she could get some water so she could wash up. I ran from the labor ward to the emergency ward trying to get a bucket of water. You won’t imagine how hard it is to even get some water to wash up![31]

Summing up the overall experience of rape survivors in the health care and criminal justice systems, Dr. Mitra said,

Many of our rape survivors have told us how police and doctors treat them. The experience by and large is humiliating for all victims. It adds to their overall trauma after rape. Some of them just become numb. Others find the whole process entirely dehumanizing. The insensitive manner and distrust with which they are treated negates their very being.[32]

Women report specific difficulties with the ways they are treated during the process of forensic evidence collection. Police officers and doctors often send survivors from one hospital to another to take various tests, and often make them wait for hours, subject them to multiple uncomfortable examinations, and sometimes publicly identify them as “rape cases” in hospital corridors.[33] Some survivors are admitted to hospital for up to five days because certain doctors are not immediately available to examine them and aspects of the forensic examination take time. The hospital then charges the survivor’s family the costs of the hospital bed and examinations.[34] Overburdened gynecologists and other physicians are often reluctant to examine rape survivors because they want to avoid embroiling themselves in a complex and sensitive case that could eventually require them to testify in court. One Delhi-based forensic expert said, “They will be dragged out of their work in another ward to come and examine [the rape survivor], and this annoys them, and they take out that anger on rape survivors.”[35]

***

Women’s rights, children’s rights, and health rights activists have been strong advocates for changing criminal laws and health care and criminal justice practices for dealing with sexual violence. Though much remains to be done, some promising developments, including recent amendments to criminal laws, demonstrate the Indian government’s willingness to protect the rights of women and children who experience sexual violence.[36] In March 2010, the Indian central government publicized and invited response to a draft Criminal Law (Amendment) Bill that seeks to reform both substantive and procedural laws regarding sexual violence.[37] The government has also initiated drafting a separate law dealing with sexual offences against children. In response to Supreme Court orders, the National Commission for Women and the Ministry of Women and Child Development have drafted a proposal for the “relief and rehabilitation” of rape survivors.[38] Simultaneously, a “Perspective Plan for Indian Forensics,” which aims to reconsider the ways in which all forensic services are delivered, is under development.[39] This time of change presents a unique opportunity for reforming the approaches of the criminal justice and health care systems to survivors of sexual violence.

This report does not present the whole range of problems that survivors of sexual violence encounter in their interactions with the Indian criminal justice and health care systems. Instead, it discusses the problems posed by one of the most archaic forensic procedures still in use: the finger test—a practice where the examining doctor notes the presence or absence of the hymen and the size and so-called laxity of the vagina of the rape survivor and comments about whether she is “habituated to sexual intercourse.”[40]

The Role of Forensic Evidence in Sexual Violence Trials

Collection of forensic evidence is routine in sexual violence cases in India. Usually, after the police register a complaint of rape, police officers take the survivor to a government hospital to collect forensic evidence. A doctor examines the rape survivor and prepares a report (commonly known as a medico-legal certificate or MLC) that becomes part of the evidence. The doctor may also collect and seal samples (vaginal swabs, blood samples, nail clippings, and so on) and hand them over to the police officers, who take them for testing at a forensic laboratory, which also submits a report.[41] All the reports, along with the doctor’s opinion, are then used in court, along with the oral testimony of the doctor, if any.[42]

Under Indian criminal law, the prosecution can secure a conviction on a rape charge based solely on the testimony of the rape survivor, provided the testimony is cogent and consistent, inspiring confidence. The law does not require corroboration by forensic evidence to secure a conviction.[43] In theory, it is legally relevant but not essential. However, prosecutors and lawyers have told Human Rights Watch that in practice, judges and the police give significant weight to forensic evidence, and it can influence whether a conviction is secured.[44]

Forensic evidence plays a powerful role inside and outside the court. Several legal experts and activists interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that in their experience, it significantly influences the beliefs of both the police and doctors about whether a woman was in fact raped.[45] Maharukh Adenwala, a legal activist with many years of experience assisting rape and child sexual abuse survivors, said,

How sincerely and seriously the police investigate the case itself depends on what they see in the medico-legal report. They form an opinion about whether the woman was actually raped or not just based on what the doctor’s report says. So if the doctor’s report is written poorly, it does affect us [the prosecution], even though technically, medico-legal evidence is not required for conviction.[46]

Problems with Forensic Evidence and its Use in Rape Trials

Given the importance of medico-legal evidence, it is critical for such evidence to be properly collected, stored, tested, recorded, and presented in court. Yet for decades, problems have riddled Indian procedures for the collection and use of medico-legal evidence.

Delays in reporting rape and in gathering and processing forensic evidence pose a huge stumbling block for the prosecution. It is well documented that many rape survivors do not immediately lodge a police complaint because of the tremendous social stigma attached to the crime.[47] Yet the defense counsel often uses any reporting delay to discredit the survivor. Delays in reporting rape also lead to the loss of forensic evidence, which may weaken the survivor’s case in court.

When survivors of sexual violence decide to file a report, they often face unnecessary impediments.[48] Survivors who approach health care providers directly often find that doctors are reluctant to examine and treat them unless they have already registered a police complaint, which can discourage or delay them from pursuing treatment.[49] Even when forensic evidence is collected without delay, poor methods of collection, storage, and chain of custody of evidence, as well as processing delays, often either render it unusable or result in inconclusive information.[50]

Doctors’ evidence collection techniques are extremely uneven. In the past, Indian criminal law did not specify what types of information should be collected during a forensic examination of a rape survivor. In 2006, the law was amended to provide some clarity on this, but many activists feel that the new law has not been effectively implemented.[51] Further, the 2006 amendment still left a great deal of discretionary scope for individual hospitals or doctors to record what they considered relevant as “other material particulars in reasonable detail.”[52] The Indian Medical Association (IMA), a voluntary network of doctors across the country, has, with the help of the Indian Department of Women and Child Development, developed a standard template for the forensic examination of rape survivors.[53] Yet as neither the doctors nor the department have the power to implement it in hospitals, it is not followed nationally.[54] There have been localized initiatives. In early 2010, the office of the Delhi Director General of Health Services issued a template similar to that of the IMA, to be followed in all Delhi government hospitals.[55] In June 2010 the Maharashtra state government introduced state-wide guidelines to standardize a system in which many hospitals had their own templates, and where, in those that did not, doctors would write medical opinions on blank sheets of paper.[56] Health rights activists across the country have criticized all of these various templates as flawed, because they are either based on outdated medical jurisprudence textbooks or on medical practice passed down over the years that has ignored scientific developments, current legal trends, and survivors’ rights.[57]

In any event, forensic examination protocols or templates alone are not sufficient. Doctors repeatedly told Human Rights Watch that the Indian government should introduce training to demonstrate how to use protocols and develop medical opinions in an accurate and scientific manner without prejudices against survivors.[58] Dr. N. Jagadeesh, a forensic expert who has analyzed medico-legal responses to sexual violence, said that “there are inherent biases in the manner in which the doctor writes the reports. Some hospitals do it well. Many do a superficial, mechanical job.”[59] Based on his experience from accompanying hundreds of rape survivors for forensic examinations, Dr. Rajat Mitra said, “There is no informed, uniform, or sensitive procedure. What guides the testing is the personal belief of the police and the doctor.”[60]

Doctors who examine rape survivors receive little, if any, training on how to conduct a forensic examination and document evidence.[61] Unlike many other countries, India does not have a class of forensic nurses or specialized training programs in forensic examination for sexual offences for medical students.[62] Dr. Harish Pathak, a professor of forensic medicine who formerly headed the forensic medicine departments of leading government hospitals in Mumbai, explained doctors’ preparation:

At best, doctors will have some half-an-hour or one hour lecture on medical evidence every year. No training. Nothing at all for medical examination in rape cases. Compare this to SAFE—Sexual Assault Forensic Examination— programs in other countries like Canada and US. They have a dedicated cell where women can come and report sexual assault and be treated and examined by trained doctors.[63]

Forensic experts, lawyers, and health activists told Human Rights Watch that the absence of such training left doctors ill-equipped: most doctors do not know how to collect evidence and write consistent and accurate medico-legal opinions. A Delhi-based forensic medicine expert cited examples of medico-legal reports where the doctor had merely recorded that a rape survivor displayed no injury marks or bleeding, without noting that this might be because the survivor had delayed reporting the assault. He said that later the defense tried to take advantage of this to suggest that no rape had occurred.[64] He said, “There should be a simple format and doctors should be told how much to write and what is relevant. And ideally, when doctors are working to examine a victim, they should be able to consult with lawyers. We need some kind of inter-sectoral approach where everyone works together.” Adenwala, a legal activist who aids women and children survivors of sexual abuse, said that she finds that a poorly written medical opinion can often prejudice police officers and judges against a survivor and cause them to doubt the merits of her case.[65] Rebecca Mammen John, another leading criminal lawyer, reiterated the importance of training doctors to write medico-legal opinions, citing several examples of inconsistent and unclear documentation that led to confusion during trials.[66]

The Indian women’s movement has consistently noted that medico-legal opinions and their interpretations frequently perpetuate damaging stereotypes in the law. For instance, the assumption is to doubt whether a woman or girl was in fact raped if she does not show obvious signs of emotional distress, which are recorded in the medical report, or if she shows no visible physical sign of injury from her “resistance” to rape.[67] Flavia Agnes, a leading feminist lawyer in the country, has strongly condemned the “blatantly anti-women statements” in medical jurisprudence textbooks that are “disguised as neutrality,” and fail to “take into account the recent trends in medico-legal aspects of rape.”[68] The finger test, more commonly known as the two-finger test, is an example of an arcane test presented in many medical jurisprudence books and commonly practiced by doctors in many hospitals in India.

IV. The Use of the “Finger Test”

In the finger test, also known as the two-finger test, the examining doctor notes the presence or absence of the hymen and the size and so-called laxity of the vagina of the rape survivor.”[69] The finger test is widely used in efforts to assess whether unmarried girls and women are “habituated to sexual intercourse.”[70] Yet the state of the hymen offers little to answer this question. A hymen can have an “old tear” and its orifice may vary in size for many reasons unrelated to sex, so examining it provides no evidence for drawing conclusions about “habituation to sexual intercourse.”[71] Furthermore, the question of whether a woman has had any previous sexual experience has no bearing on whether she consented to the sexual act under consideration. The continued use of the finger test points to a gulf between Indian forensic and legal practice and current scientific knowledge and court decisions that recognize women’s rights.[72]

Archaic Theory in Practice

The origin of the test remains unclear. References to the test in Britain can be found as far back as the early 18th century,[73] and it appeared in a leading medical jurisprudence book in British India in the 1940s. At this stage, ironically, the finger test was used to dispel the myth that an “intact hymen” proved rape had not occurred. Mimicking penile penetration, doctors inserted two fingers through an intact hymenal orifice to show that it could stretch without tearing.[74] The test and prescriptions for its use continue to be found in textbooks currently assigned to medical students and often consulted by lawyers and judges, but now the test is described and used in the context of determining whether a rape survivor was “habituated to sexual intercourse,” as though that were possible or could help determine whether she had been raped.[75]

Over the years the test has been normalized in India and has entered widespread practice in many hospitals across the country. Although several lawyers feel that recent Supreme Court judgments and amendments to the Indian Evidence Act have deterred such testing and its use in court, the practice is far from being eliminated.[76]

At least three leading government hospitals in Mumbai, including one where at least a thousand rape survivors are examined every year, continue to conduct the finger test. These hospitals’ forensic examination template specifically asks doctors to state whether the “[h]ymenal orifice: admits: One/two fingers.”[77]

In Delhi, Dr. Rajat Mitra from Swanchetan, a nongovernmental organization that has worked with thousands of rape survivors from the city and other parts of the country, described the practice as “near universal.”[78] One judge who has served in trial courts across various districts of Delhi said that doctors routinely write results of the finger test into their medico-legal opinions, especially in the outer districts of Delhi, and this allows defense counsel to use them as evidence in court.[79] Khadijah Faruqui, a Delhi-based lawyer and human rights activist who works with Jagori, a feminist resource center, has assisted hundreds of rape survivors, and said that doctors have been receptive to concerns about the two-finger test in New Delhi (one district of Delhi), but it continues to be used commonly in other parts of the city. She said: “In cases where activists go with the victims and say it should not be conducted, doctors do not conduct it. That is about 20 to 30 percent of the cases. In others, they conduct it.”[80]

The practice is not just confined to Mumbai and Delhi. Anecdotal evidence suggests that it is even more prevalent outside the big cities. For instance, Dr. Indrajit Khandekar, a forensic expert from rural Maharashtra who authored a report analyzing the problems with forensic evidence collection there, said that he has seen many medico-legal opinions that include finger test results.[81] A gynecologist from Chandigarh in northern India said that the practice was common there too.[82] Neelam Singh, a gynecologist who conducts trainings for medical officers in Uttar Pradesh state, said that she had seen doctors use this test.[83] Shazneen Limjerwala, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on rape in the state of Gujarat, said the practice occurs there too.[84] Even the Indian Medical Association (IMA) protocol for the forensic examination of rape survivors, which has been disseminated in regional workshops across the country,[85] seeks information about the “hymenal size,” whether the vaginal opening is “narrow” or “roomy” and has “old tears,” whether injuries to the hymen are “fresh/recent/old,” and asks the doctor to give an opinion as to whether the medical evidence suggests “habitual sexual intercourse.”[86]

Seventeen nongovernmental organizations and 51 activists and lawyers from across the country wrote in a January 2010 open letter to Minister of Law and Justice Veerappa Moily that the “finger test continue[s] to be used … allow[ing] doctors to state whether a woman [is] ‘habituated’ to sex. This test allows character evidence to disqualify a victim’s testimony.” The activists continued: “Change in the structure of humiliation which typifies rape trials is not possible unless medical jurisprudence textbooks and procedures are changed.”[87] They reiterated this demand in a letter to the Indian government in June 2010.[88]

Human Rights Watch examined 153 High Court judgments in rape cases across the country that referred to the finger test, all issued since 2005, and some as recently as 2009 and 2010.[89] This analysis shows that defense counsel and courts throughout India continue to invoke finger test findings in proceedings in rape cases.[90]

Doctors and activists say that the most common descriptions of findings from finger tests in medico-legal reports are: “two fingers admitted,” “two fingers easily admitted,” or “two fingers not easily admitted.”[91] In some reports these types of comments are combined with observations about whether the hymenal tear is “old.” Some doctors describe the vagina using different phrases such as “patulous vagina” or “distended vagina.” These findings are then used to give opinions about whether the rape survivor was “habituated,” “used to,” or “accustomed to” sexual intercourse.[92] The complete illogic of these findings is illustrated by cases where an examining doctor deposed that a survivor who reported gang rape was “habituated to sexual intercourse.” In some of these cases, judges pointed out that the gang rape itself could have caused the doctor to conclude that the girl or woman was “habituated” to sex.[93]

Some doctors continue to administer the test to very young children who have been raped. Human Rights Watch spoke to a Mumbai-based mother of a six-year-old girl who was raped, and whose 2010 medico-legal report included the words, “tip of finger admitted.”[94] Similarly, judgments show that doctors have conducted finger tests on children as young as age six, and these findings have subsequently been used as evidence that penetration did or did not take place.[95] For instance, in the case of Mohammed Jaffar, who was charged with raping a six-year-old girl, the doctor stated that “the hymen orifice admitted tip of little finger … and the vaginal orifice admits one finger with difficulty.”[96] The court used this as evidence that there was no penile penetration, ordered that rape charges be dropped, and reduced the sentence to an offense of attempt to rape.[97] Children’s rights groups across India have expressed concerns about the lack of a clear and sensitive protocol for forensic examination of sexually abused children, both boys and girls.

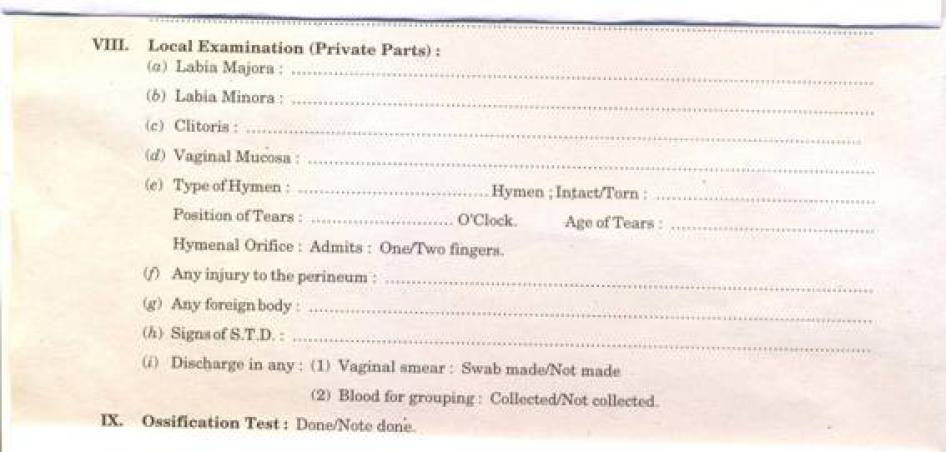

Where hospitals have medical forms for doctors to record their findings, doctors record the results against columns that are either marked “per vaginum digital examination,” or “fingers admitted,” or state their finding against a column that asks whether the vagina is “narrow/ roomy.”[98] For instance, the June 2010 guidelines issued by the Maharashtra government carries a section that seeks the following information from the examining doctor: the “type of hymen,” whether the hymen is “intact/ torn,” “age of tears,” and whether the “[h]ymenal orifice: admits: one/ two fingers.”[99]

Similarly, the IMA protocol and the 2010 Delhi protocol ask doctors to furnish information on whether the hymen injury is “fresh,” “recent,” or “old,” the “size of the hymenal orifice,” and whether the vagina is “narrow,” “roomy,” or has “old tears.”[100] Both protocols also ask the examining doctor to give an opinion on the following lines:

After performing the above mentioned clinical examination, I am of the considered opinion that the findings are ……………………………… consistent / not consistent with …………………… recent / old / habitual sexual intercourse.[101]

Doctors who do not use any templates for their medico-legal reports generally include a line that reads “P/V” or “PV” (for “per vaginum” examination) and state how many fingers passed or just say whether the survivor was “habituated to sexual intercourse.”[102]

Doctors alone cannot shoulder the responsibility of changing how medico-legal opinions are written and presented in court. There is evidence to suggest that in some cases police officers ask doctors to conduct the finger test. Dr. Indrajit Khandekar, who is an assistant professor of forensic evidence at the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences in Wardha, said, “I have seen many requisition letters [to doctors requesting forensic examinations] by the police which ask the question ‘Is the girl “habituated” to sex?’”[103] Some doctors said they felt compelled to use the finger test to render an opinion about whether a rape survivor was “habituated to sexual intercourse,” either because hospital protocols include this information, or because they feared that either defense counsel or judges would ask them why they omitted the test and failed to provide an opinion.[104] Confirming their fears, one former sessions judge said that if doctors do not conduct the test, “Judges will ask doctors ‘Why was this test not conducted?’ ‘Is this woman habituated to sexual intercourse?’ They will have to give an opinion.”[105]

Perpetuating Damaging Stereotypes through Medico-Legal Interpretations

A medico-legal report that identifies an unmarried girl or woman as allegedly “habituated to sexual intercourse” attaches extreme stigma to her, compounding the considerable stigma unmarried women already face when reporting rape, and adding to a general stereotype about sexually active women.[106] Police officers, prosecutors, other lawyers, and judges may have a conception that a “bad” woman of “loose morals” may try to press a false charge of sexual assault against an innocent man. For instance, one former public prosecutor who spoke with Human Rights Watch said, “I find that in most cases where the man is not known to the woman, then it is definitely rape, but where the man is known to the woman, it is usually not rape, and it is a case of false charge.”[107]

Lawyers told Human Rights Watch that usually no acquittal or conviction rests completely on the findings of the finger test, but the defense uses these findings to break the morale of the survivor while she is testifying in court, to question her character and credibility, or to dispute her consent to the sexual act under consideration.[108]

Undermining the Confidence, Character, and Credibility of Rape Survivors

Especially in the case of an unmarried woman or girl, being identified as “habituated to sex” can make it a harrowing experience for her to aid the investigation and prosecution. A 2003 amendment to the Indian Evidence Act says that the defense cannot cross-examine the prosecutrix about her “general immoral character.”[109] Several legal experts said this amendment had provided some relief to survivors.[110]

But questions about character have not been stamped out of trial court practice because the extent to which such questions are allowed or disallowed is dependent on the sensitivity and personal beliefs of the presiding judge. For instance, lawyer and human rights activist Khadijah Faruqui said that in her experience, the Patiala House Court (trial court complex) located in central Delhi is more sensitive to the problems of the finger test, but that judges in other parts of Delhi often accept arguments based on finger test findings.[111] Similarly, lawyer Rebecca Mammen John explained that “archaic” finger test findings give an “unfair advantage” to the defense, which uses the findings to influence the judge.[112] She said,

As long as the two-finger test remains, it will provide the defense with a ready-made line of argument. And rape trials in India will be dependent on the individual sensitivity of judges, prosecutors, and defense counsels. Why should that be the case? It is an archaic procedure and needs to go.[113]

One judge who has overseen rape trials for nearly two decades said that many defense lawyers used the “habituated to sex” opinion to shake the confidence of survivors testifying in court, and judges respond unevenly. The judge said,

The defense will try to beat the morale of the victim by raising questions about her character. They know these are irrelevant and cannot be asked of the victim. Even if the judge disallows the question, they [defense] will say, “You disallow my question but put it on record.” It takes a long time—putting it on record, disallowing the question—these things take time. So they will simply try to tire the victim in court. They will ask a hundred irrelevant questions and one relevant question. It is an art or strategy—to ask questions about her character. And even if it is disallowed, the damage is done—it has affected the victim psychologically. And this is where some judges get overawed by the defense and then stop intervening to control them. And it takes many hours or even days for the testimony of the victim to be recorded. And at the end of a harrowing day, victims break down in court. That is what questions about character are for—it plays a huge role in demolishing the strength of the victim in court.[114]

Courts have at times made comments about the “character” of the rape survivor based on the finger test results. For example, in a 2009 rape case in which Musauddin Ahmed was the defendant, the Supreme Court (in spite of its own previous judgment) stated that “the prosecutrix appears to be a lady used to sexual intercourse and a dissolute lady.” And further, that “she had no objection in mixing up and having free movement with any of her known person, for enjoyment. Thus, she appeared to be a woman of easy virtues.”[115]

In the case of Hare Krishna Das, who was also accused of rape, the Patna High Court placed great weight on the doctor’s opinion that the survivor was “habituated to sex.” Acquitting the accused for lack of medical evidence, the court reasoned that the testimony of the rape prosecutrix was not reliable:

Though the girl was aged about 20 to 23 years and was unmarried but she was found to be “habituated to intercourse.” This makes her to be of doubtful character.[116]

Alternatively, judges interpreted pain, blood, or fresh hymenal tears during a forensic examination to mean the rape survivor was not loose or that it was her “first” experience of sexual intercourse. For example, in Suresh Kumar’s case, the High Court of Chhattisgarh evaluated the medical evidence and held:

She was complaining pain and the vagina was admitting 1½ finger [sic] ….

From the medical report it is clear that the prosecutrix was not a girl of lax moral and she was not “habituated to sexual intercourse” and most probably, that was her first experience as the doctor has observed reddishness on her vagina and blood secretion and pain on touching the vagina.[117]

In another case, the court looked at medical evidence that showed the doctor had inserted two fingers “with difficulty,” and further, that “when the fingers were inserted there was bleeding.” Based on this, the court concluded that the survivor was not “habituated to sex,” and her “virginity was violated for the first time.”[118]

Especially in cases where a doctor has noted that hymenal tears are not fresh and two fingers passed easily, courts have used the information against rape survivors. In Gokul’s case, the court acquitted the accused and observed that:

The prosecution has also failed to show that the rupture of vagina was fresh. On the contrary, the evidence is that two fingers could easily enter in the vagina.… If [a] version given by the prosecutrix was unsupported by any medical evidence or whole surrounding circumstances were improbable and belief [sic] the case sent up by the prosecutrix, the Court should not act on the solitary evidence of the prosecutrix.[119]

Even where medico-legal reports show that two fingers have not easily passed, lawyers have used this in favor of the accused. For instance, one former public prosecutor said,

If the prosecutrix says she is raped and then it comes in medical evidence that two fingers have not passed, then it goes towards positive evidence for the accused. It is a critical piece of evidence for the defense. If there is penetration, then two fingers should pass.[120]

Similarly, medico-legal reports showing that even one finger passes with difficulty during the finger test have been taken as evidence that there was in fact no penetration.[121] Yet the finger test is not a reliable indicator of whether prior penetration has ever taken place.[122] Furthermore, the use of medico-legal findings against the prosecutrix run contrary to the Supreme Court decisions holding that penetration under the law does not require full penetration of the vagina and penetration to any degree is sufficient to prove a charge of rape.[123]

Defense Arguing Survivors’ Consent

Where medico-legal reports record findings such as “old tear” or “two fingers easily passed,” the defense has used them to argue that the girl or woman, who was “habituated to sex,” likely gave her consent and was not raped.[124] One former public prosecutor said,

Where the defense takes the line that there was consent [to sexual intercourse], usually they also look to medical evidence for support. And if the medical report says anything about the two-finger test, then they draw it out in court—saying she was “habituated” so consented and is falsely implicating the accused.[125]

Another former public prosecutor said,

The finger test is relevant for the defense especially if the prosecutrix case is that the woman is unmarried [as opposed to a married woman who is assumed to be “habituated to sex”]. Then if the medical report says that two fingers have passed, the defense can show that she is habituated. This shakes the testimony of the prosecutrix.[126]

One former trial court and high court judge, who has adjudged many rape trials and appeals, stated that whether a woman was “habituated to sex” was irrelevant but said that the benefit of doubt was given to the accused in “borderline cases.” She said,

Every rape case is unique, so it is difficult to say whether generally the two-finger test will be relevant. But “admits two fingers” shows that the woman is used to sexual intercourse—it does not show anything else. But in borderline cases, the defense will get some benefit of doubt if it is shown that the woman is “habituated [to sexual intercourse].”[127]

Human Rights Watch found that many trial and appellate proceedings across the country have used this line of argument and courts have interpreted this in different ways.[128] In some cases, the courts accepted this argument, but eventually held that even though there might have been consent, it is irrelevant because the survivor was aged under 16 years at the time of the incident, which constitutes statutory rape (also known as “technical rape”) under Indian law.[129]

Medico-Legal Findings a Scientific Myth

Medico-legal opinion based on the finger test has no scientific value. Many forensic experts, gynecologists, and doctors in India have rejected it, saying that the finger test and related assessments are completely baseless, unscientific, and do not generate any reliable or valid information.

Indian courtroom proceedings related to rape routinely discuss the state of the girl’s or woman’s hymen.[130] A common misconception underlying these proceedings is that the hymen is like a closed door sealing the vaginal opening, which is necessarily “broken” on “first intercourse.” The hymen is actually just a collar of tissue around the vaginal opening that does not cover it fully. Especially in pubertal and post-pubertal girls and women, it becomes elastic. Contrary to the medico-legal significance attached to the hymen in Indian rape trials, the international consensus is that the examination of a woman’s or girl’s hymen cannot indicate definitively whether she is a “virgin” or is “sexually active.”[131] “Old tears” or “laxity” of the hymen and vagina do not prove that a girl or woman is “habituated to sex,” because they can be caused by exercise, physical activity, or the insertion of tampons or fingers, among other events not related to sexual intercourse.It is precisely for these reasons that the WHO guidelines state that specialized training is required for doctors to conduct genito-anal examinations, and understand and interpret findings accurately in the case of all survivors under age 18.[132] In any event, whether a woman or girl has had consensual sex in the past has no bearing on whether she consented to the sexual activity under investigation.[133]

The head of the department of forensic medicine in a leading Delhi hospital said,

It [two-finger test] is all a myth. Nothing—no scientific evidence to show that if two fingers pass or don’t pass it has anything to do with being “habituated [to sexual intercourse]” or penetration at all. Now this myth is being used in courts.[134]

Similarly, Dr. Amar Jesani, a general physician and leading health and human rights activist in the country, said, “There is no scientific evidence to show that this test is correct. It is high time that the government revised its old textbooks from the 19th and 20th century.”[135]

Even if the presence of the hymen and size of the vagina did reliably answer questions about a girl or woman’s sexual experience—which they do not—the results of the test would still be arbitrary and unscientific because they vary depending on the size of the examiner’s fingers and his or her subjective assessments. Dr. Harish Pathak, a professor of forensic medicine, explained how the finger test violates the basic principle of objectivity in science:

The two-finger test is not scientific. What is scientific? Scientific evidence is that which is objective, and when the test is repeated by anyone, then the same results will be achieved. The two-finger test is a subjective test. There are many variables—the test results will be different depending on the size of the doctor’s fingers. If someone like Dara Singh [a big-built Indian wrestler] is the doctor conducting the test, then the results will be different than when I conduct it. Then the doctor has to say “whether one or two fingers passed easily,”– what is easily? What is easy for one person may not seem like it is easy for another.[136]

Raising similar concerns, Dr. N. Jagadeesh, another leading forensic expert, said, “Whose fingers are we talking about? And what is easy? This is not science.”[137]

Dr. Khandekar, an assistant professor of forensic medicine, said,

The finger test needs to go. Doctors have been conducting this because old textbooks have been recommending this, and there is no clear pro forma [format] for conducting medical tests and developing medico-legal reports in rape cases. Different hospitals use different formats or some doctors just write a medico-legal report however they want to. The test has no relevance at all when assessing whether the victim was raped.[138]

Anecdotal evidence from actual courtroom examples highlights the arbitrariness and subjectivity inherent to the finger test. For example, doctors have testified that women and girls are “habituated to sex” even where the vagina admits “two fingers with difficulty” [139] or “one finger.”[140] In one case, a 12- or 13-year-old girl who was raped was subjected to two forensic examinations. One doctor deposed: “vagina admitted one finger with difficulty. Victim felt pain on introduction of finger in vagina.” The second doctor who examined her deposed: “vagina admits two fingers tightly.” The defense counsel sought to take advantage of this discrepancy in doctors’ depositions and argued that there was no rape, but the judge rejected the argument.[141] No one suggested that the doctors’ varying opinions showed their subjectivity, and thus rendered the test invalid.

Denouncing the test categorically and saying it was “unprofessional, unscientific, and generated no reliable evidence” about anything, one judge strongly advocated excluding it from forensic examinations of rape survivors.[142]

In fact, the Indian Supreme Court, whose decisions are binding across the country, has itself observed that “the factum of admission of two fingers could not be held to be averse to the prosecutrix,” and described finger-test assessments as “hypothetical and opinionative,” implying recognition for the inherently subjective, arbitrary, and unscientific nature of the test and related opinions.[143]

Judges and lawyers told Human Rights Watch that medical and legal professionals must be made more aware of the unscientific nature of this test if it is to be eliminated from medico-legal opinions, courtroom proceedings, and judgments.[144] The WHO guidelines for medico-legal care for survivors of sexual violence clearly states that even a purely clinical procedure such as a bimanual examination is rarely justified following sexual assault.[145]

Finger Test Results in Repeated Trauma

Inserting fingers into the vaginal or anal orifice of an adult or child survivor of sexual violence can cause additional trauma, as it not only mimics penile penetration but can also be painful. In their June 2010 letter to the Indian government, Indian women’s rights activists drew the government’s attention “to the existence of tests like the two-finger test, which further aggravate women’s experience of assault.”[146]

Anecdotal evidence suggests that some doctors in India conduct the two-finger test with little or no regard for a survivor’s experience of pain or trauma during such examinations. For instance, in one case, a gynecologist examined the survivor, found that she had a vaginal injury that was 6.4 centimeters long, sutured the wound, and referred her to a “medical jurist”— a doctor assigned to handle medico-legal cases. The second doctor proceeded to conduct her own examination, and found that the hymen was absent, noticed the stitched wound, and nevertheless inserted two fingers, recording: “vagina admitted two fingers and blood was coming out of the stitches.”[147] In yet another case, a doctor noted that the hymen was ruptured, inflamed, and vagina lacerated; and conducted the finger test and deposed: “vagina of the prosecutrix admits two fingers with difficulty and painfully.”[148] Similarly, another doctor reported that when he inserted one finger into the vagina of a 13-year-old rape survivor, it was “very painful.”[149] The WHO guidelines recognize that while some pain may be unavoidable given the nature of the examination, but recommend that an examining doctor should take steps to minimize pain either by conducting a limited examination or by administering analgesics.[150]

Pratiksha Baxi, a leading Indian feminist sociologist, has condemned the finger test as a technique that “rests on the precarious desexualisation of a clinical practice.” She points out that inserting fingers into a woman’s vagina without her consent constitutes a sexual assault, yet the two-finger test is conducted under the rubric of a professional investigation, and doctors obtain blanket uninformed consent for the forensic examination in advance.[151]

In India, health care workers ask adult survivors of sexual violence and guardians of child victims to consent to a forensic examination without providing detailed information or ensuring that they understand the procedure in a meaningful way. Indian law and WHO recommendations both say that a rape survivor must give her consent for a forensic examination.[152] The WHO guidelines state that the examining doctor should explain every step of the examination procedure to a survivor, giving her an opportunity to refuse any part of it.[153] Activists who accompany rape survivors to forensic examinations and lawyers who prosecute rape told Human Rights Watch that doctors generally seek blanket consent for any and all medical procedures to be conducted as part of the forensic examination, but seek no specific consent for the finger test, whose details and potential impact rape survivors generally do not understand at all.[154]

One adult survivor told Human Rights Watch,

The clerk told me a male doctor will conduct the test [forensic examination] and asked me whether that was ok. I said “yes.” But other than that, I did not know what they were going to do. I was so scared and nervous and praying all the time: “God, let this be over and let me get out of here fast.” I don’t know what information they collected. I did not even know it was going to be like a delivery examination [internal gynecological examination]. They used some machine and checked the place I urinate from. Took some blood, urine. That’s all.[155]

One parent of a six-year old child who had been raped said,

The check-up happened in the delivery room. I was not allowed inside with my daughter when she was examined. She went in with a lady police officer. I only know that they collected blood and urine because they gave it to me in dibbey [containers] and asked me to take it to the police station. I do not know what else they did during the examination.[156]

She showed Human Rights Watch a photocopy of her child’s medico-legal report, which stated that the “tip of finger passed” into the “hymenal orifice.” She did not know the significance or the meaning of this test, or how this information would be used during the trial.[157]

Survivors of rape seldom have a real opportunity to refuse consent for medical procedures. One social worker said,

It is very rare that women can say, “I don’t want this part of the examination,” or ask questions about what is being done. Even with social workers present, it is very difficult. In all the cases that we have dealt with, I know of only two cases where women have been able to say what they want. In one case, the woman stated clearly that she did not want an internal vaginal examination because the man had only tried to rape her and had not succeeded, so it was not necessary. In another case, the victim said she wanted to mull over whether she wanted the examination and to give her some time.[158]

Another human rights activist said,

In one or two cases I have seen doctors force the victim to go through all the tests. In one case, the victim only wanted a STD/HIV test to be done. She was menstruating and she was not comfortable. But basically the doctor told her she has to take the exam and she said ok.[159]

Several leading criminal lawyers said that rape survivors face adverse consequences if they refuse consent to the full forensic examination. If a rape survivor refuses to go through the entire test, the police may consider her uncooperative, reducing their commitment to the investigation, and if the case eventually goes to court, the defense may argue that she had something to hide.[160]

Lawyer Rebecca Mammen John noted a case when her client was damaged by a doctor’s note that she was “very uncooperative.” In the medical certificate, the examining doctor had noted the presence of internal injuries and had observed in writing that the victim had difficulty walking. The doctor also noted in the medico-legal report that the victim was “very uncooperative,” which the defense sought to exploit in court. She continued:

When we found out why the doctor had written “very un-cooperative” in the report, we found that it was because she [the rape survivor] had refused to undergo this two-finger test. She had pressed her legs together and refused to allow the doctor to examine her any more. She obviously did that because she was in tremendous pain. We are talking of someone who has just been raped and in pain … And I don’t understand the need for this [finger test] because the doctor had already recorded that there was a tear in the posterior fourchette [part of the vagina] and she had difficulty in walking. The two-finger test should go. It is an archaic procedure that adds to the trauma of rape victims and actually compounds their suffering.[161]

“Habituation to Sexual Intercourse” Legally Untenable

Over time, Indian medico-legal practice has become disconnected from legal developments.

The Indian Supreme Court made two important pronouncements that render the finger test untenable. First, the court has held that two-finger test results cannot be used against the prosecutrix.[162] Second, it has clearly and repeatedly held that showing that a survivor is “habituated to sexual intercourse” is immaterial to the issue of consent in a rape trial.

In State of Uttar Pradesh v. Pappu, the Indian Supreme Court held that the prosecutrix’s “habituation to sexual intercourse” was irrelevant. In this case, while hearing the appeal against the trial court’s judgment, the Allahabad High Court acquitted the accused, accepting the defense argument that the prosecutrix was a “girl of easy virtues,” and that medical evidence showed she was “habituated to sexual intercourse” and displayed no physical injuries. The prosecutrix was known to the accused, and the defense counsel had argued that “the prosecutrix was not having a good character and since her house was in front of his house, he and his family members asked them to leave that place and hence the false case was foisted.”[163] Reversing the judgment of the Allahabad High Court, the Supreme Court held,

Even assuming that the victim was previously accustomed [to] sexual intercourse, that is not a determinative question. On the contrary, the question which was required to be adjudicated was did the accused commit rape on the victim on the occasion complained of. Even if it is hypothetically accepted that the victim had lost her virginity earlier, it did not and cannot in law give licence [sic] to any person to rape her. It is the accused who was on trial and not the victim. Even if the victim in a given case has been promiscuous in her sexual behavior earlier, she has a right to refuse to submit herself to sexual intercourse to anyone and everyone because she is not a vulnerable object or prey for being sexually assaulted by anyone and everyone.[164]

The Supreme Court reaffirmed its decision in the case of State of Uttar Pradesh v. Munshi, where the Allahabad High Court acquitted the accused on grounds that the survivor did not display physical injuries and was “habituated to sexual intercourse.” Setting aside the order of the Allahabad High Court, the Supreme Court pointed out that being “habituated to sexual intercourse” was not relevant.[165]