Always on the Run

The Vicious Cycle of Displacement in Eastern Congo

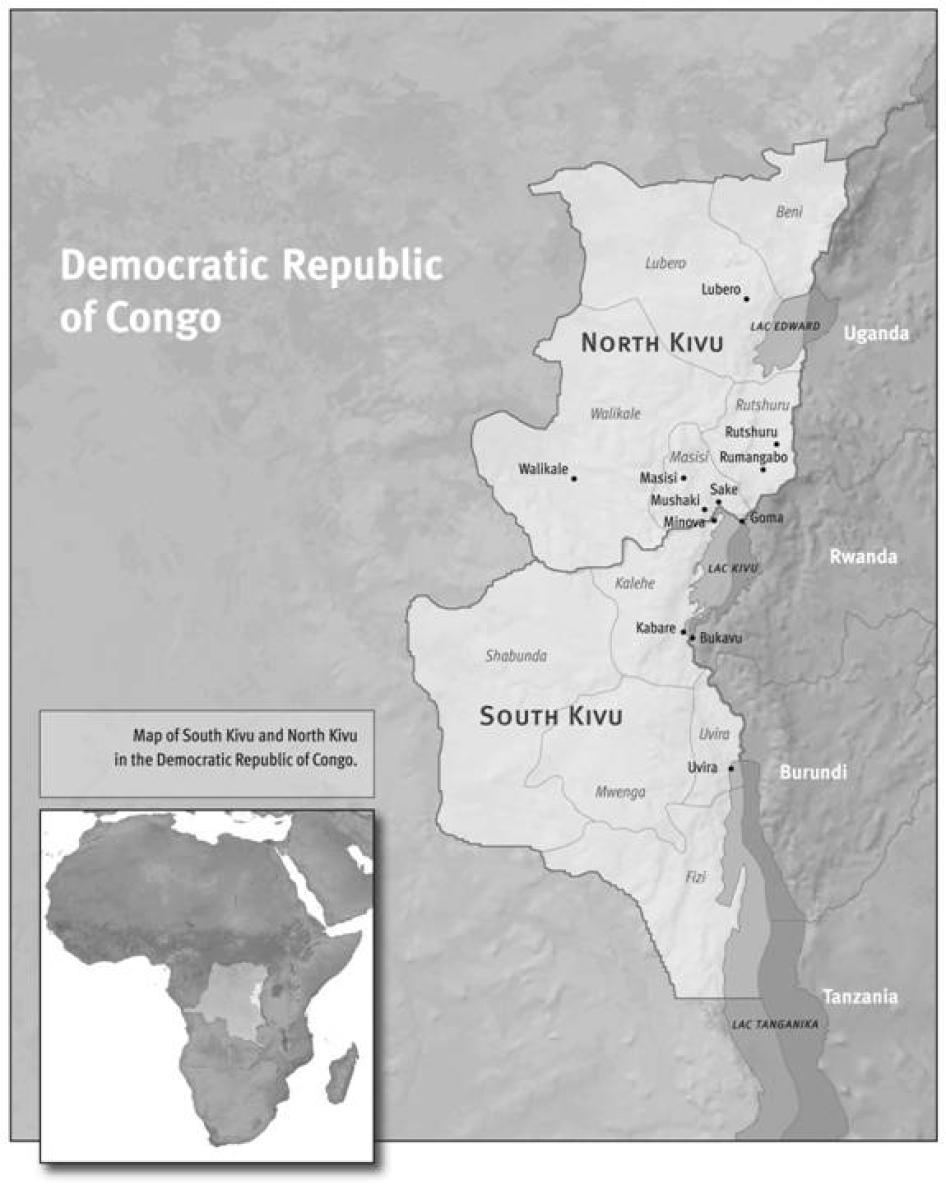

Map of the Democratic Republic of Congo

© 2009 Human Rights Watch

Glossary of Acronyms

CCCM Camp Coordination and Camp Management

CNDP National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple)

CPM Commission for Population Movements

DRC Democratic Republic of Congo

FARDC Congolese Armed Forces (Forces armées de la République démocratique du Congo)

FDLR Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces démocratiques de libérartion du Rwanda)

IDP Internally displaced person

IRC International Rescue Committee

JPT Joint Protection Team

MONUC United Nations Peacekeeping Mission in Congo

MONUSCO United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo

MSF Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières)

NFI Non-food item

NGO Nongovernmental organization

NRC Norwegian Refugee Council

OCHA United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

PARECO Coalition of Congolese Patriotic Resistance

PEAR Program of Expanded Assistance to Returnees

RRC Return and Reintegration Cluster

RRM Rapid Response Mechanism

RRMP Rapid Response to the Movement of Populations

UN United Nations

UNHCR Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

UNOPS United Nations Office for Project Services

WASH Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene

WFP World Food Program

Who’s Who

Congolese Armed Forces (Forces armées de la République démocratique du Congo, FARDC): The Congolese national army, created in 2003, has an estimated strengthof 120,000 soldiers, many from former rebel groups that incorporated followingvarious peace deals. About half of the Congolese army is deployed in eastern Congo.Since 2006 the government has twice attempted, and failed, to integrate the 6,000-strong rebelCNDP. In early 2009 a third attempt was made to incorporate theCNDP and remaining rebel groups in a process known as “fast track acceleratedintegration.” However, many of those who agreed to integrate remained loyal to former rebelcommanders, raising serious doubts about the sustainability of the process.

National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, CNDP): The CNDP is a Rwandan-backed rebel group launched in July 2006 by the renegade Tutsi general, Laurent Nkunda, to defend, protect, and ensure political representation for the several hundred thousand Congolese Tutsi living in eastern Congo and some 44,000 Congolese refugees, most of them Tutsi, living in Rwanda. It has an estimated 6,000 combatants, including a significant number recruited in Rwanda. Many of its officers are Tutsi. On January 5, 2009, Nkunda was ousted as leader by his military chief of staff, Bosco Ntaganda, and subsequently detained in Rwanda. Ntaganda, wanted on an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court, abandoned the three-year insurgency and integrated the CNDP’s troops into the government army. On April 26, 2009, the CNDP established itself as a political party.

Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces démocratiques de liberation du Rwanda, FDLR): The FDLR is a predominantly Rwandan Hutu militia group based in eastern Congo, some ofthe leaders of which participated in the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. It seeks to overthrow the Rwandan government and promote greater political representation of Hutus. Despite successive military operations against the group in 2009 and into 2010, the FDLR still has an estimated 3,200 combatants and controls significant areas of North and South Kivu, including some key mining areas. The FDLR’s president andsupreme commander, Ignace Murwanashyaka, based in Germany, was arrested by German authorities onNovember 17, 2009, on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The group’smilitary commander in eastern Congo is General Sylvester Mudacumura. The Congolesegovernment often supported, or tolerated, the FDLR until early2009, when its policy changed and the government launched military operations againstthe armed group.

Mai Mai militia: The Mai Mai militia groups are local defense groups often organized on an ethnic basis. They have traditionally fought alongside the government army against “foreign invaders,” including the CNDP and other Rwandan-backed rebel groups. In 2009 there were over 22 Mai Mai groups, ranging in size and effectiveness, in both North and South Kivu. Some joined the Congolese army as part of the rapid integration process in early 2009, while others refused, angry at the perceived preferential treatment given to the CNDP and unwilling to join the army unless they were able to stay in their communities. The various Mai Mai groups are estimated to have some 8,000 to 12,000 combatants.

Coalition of Congolese Patriotic Resistance (Coalition des patriotes résistants congolais, PARECO): PARECO is the largest Mai Mai group, created in March 2007 by the joining of various ethnic-based Mai Mai militias, including from Congolese Hutu, Hunde, and Nande ethnic groups. Throughout 2007 and 2008 PARECO collaborated closely with the FDLR and received substantial support from the Congolese army, especially in its battles against the CNDP. In 2009 many PARECO combatants, particularly the Hutu, joined the Congolese army. Its military commander, Mugabu Baguma, was made a colonel. The Nande PARECO commander, La Fontaine, remained outside the integration process, along with most Nande combatants, until February 28, 2010, when he committed to integrate with 10 of his cadres. A breakaway, largely Hunde PARECO faction, led by General Janvier Buingo Karairi and known as the Patriotic Alliance for a Free and Sovereign Congo (Alliance des patriotes pour un Congo libre et souverain, APCLS), remains outside the integration process. The APCLS is allied with the FDLR and refuses to integrate into the Congolese army without guarantees it will be deployed in its home region and that newly integrated CNDP soldiers will leave.

Summary

The scale of internal displacement in eastern Congo, and the disruption and dislocation it causes to people’s lives, is colossal. As of April 2010 at least 1.8 million people were displaced—the fourth largest internal displacement in the world—1.4 million of whom were in the volatile provinces of North and South Kivu bordering Rwanda. As people have fled, they have lost possessions, homes, land, and livelihoods; as well as family, friends, neighbors, and the economic and social support associated with them. Internally displaced persons (IDPs) have been the victims of deliberate attacks perpetrated by virtually all warring factions in the area—government forces and armed groups alike. Moreoever, IDPs are often among the civilians most vulnerable to further abuse, hunger, and disease, yet they have limited access to services such as health care and education. Many have been displaced two or three times, sometimes more. For some, the years since 1993 can be characterized as being “always on the run.”

This report mainly focuses on the displacement from late 2008 through mid-2010 and especially the first half of 2009. At least 1.2 million IDPs were forced to flee their homes during three successive military operations that began in January 2009; others had fled during earlier waves of displacement. At the same time, over 1.1 million others returned—or tried to return—to their homes between January 2009 and March 2010. Despite these attempts, over 1.4 million people remained displaced in North and South Kivu by April 2010.

This report does not provide a comprehensive history of displacement. Rather, focusing on North and South Kivu, it documents how warring parties have abused IDPs in all phases of displacement: during the attacks that uprooted them, following displacement, and after authorities decided it was time they return home. It outlines the causes of dislocation, including punishment for suspected collaboration with enemy groups and retaliation for military losses, and details the search for refuge that many IDPs undertake in forests, official camps, spontaneous sites, and host families—which are themselves often stretched to capacity. Throughout, IDPs face assault, robbery, forced labor, and rape: for example, witnesses told Human Rights Watch of women being raped in their own houses and in forests; of villagers—including children as young as six—being killed with machetes and hoes and burned to death when soldiers torched houses; and of civilians being beaten and killed for refusing to carry soldiers’ belongings.

Many IDPs try to stay as close as possible to their homes and farms so they can continue to work the land, gather food, and reassert ownership of their property if the situation improves. This report examines the dangerous return trips that many IDPs make to look for food or tend their fields and the barriers that exist to their more permanent return, including the seizure or destruction of their land by armed groups or locals. It also highlights two particular instances when authorities—the government and now-allied CNDP—were so interested in clearing IDPs from camps for political reasons that they compromised the safety of at least some of the tens of thousands of people whose homes, fields, and villages had been appropriated by locals or armed groups or whose return home otherwise remained perilous. Finally, the report outlines the official steps that have been taken to protect IDPs in Eastern Congo, including a recent initiative to combine existing displacement-focused and return-focused programs with a new emergency response strategy that instead focuses on the needs of the most vulnerable.

It notes that while the new response strategy is theoretically more flexible and adapted to the needs of eastern Congo, more assistance needs to reach the estimated one million IDPs living, as of March 2010, with host families throughout North and South Kivu. Until it does, IDPs will continue to return to insecure home areas to find food; live in dire conditions in their places of displacement; and take other risks, including fleeing their villages at the last possible moment.

Political and Military Context

The newest phase of displacement in eastern Congo began in late 2008, coinciding with a dramatic regional shift in alliances.

In December 2008 the previously antagonistic neighboring countries of Rwanda and Congo announced a joint military operation against the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Les Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda, FDLR), a predominantly Rwandan Hutu armed group operating in eastern DRC, and its allies. Shortly after, the Rwandan-backed Congolese-Tutsi armed group, the National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, CNDP), announced its integration into the Congolese army, following the arrest of the group’s leader, Laurent Nkunda, in Rwanda. Other smaller rebel groups quickly followed suit. New CNDP leader Bosco Ntaganda, wanted on an arrest warrant by the International Criminal Court (ICC), was made a general and the de factodeputy commander of the Congolese army’s military operations in the east. This heralded a series of three military operations pitting the Congolese army against the FDLR: the first, in conjunction with the Rwandese, starting in January 2009; the second, starting in March 2009, together with the UN Peacekeeping Mission in Congo (MONUC); and the third, and most recent, also backed by UN peacekeepers, starting in January 2010, was ongoing at time of writing.

Government and rebel forces carried out widespread and vicious attacks on civilians during these operations, triggering renewed and massive displacement. In December 2009, Human Rights Watch reported that at least 1,400 civilians were killed between January and September 2009 and over 7,000 women and girls raped—numbers that no doubt represent only a fraction of the actual total. Government forces and FDLR also abducted and pressed thousands of civilians into forced labor, including carrying weapons and supplies, as they moved about. Since January 2010, following a new round of military operations against the FDLR, civilians in many parts of North and South Kivu continue to endure forced labor, arbitrary arrests, illegal taxation, looting, sexual violence, and excessive restrictions on movement.

Improved Security since 2009?

Although military operations continue, Congolese government officials and UN planners have begun to plan and implement stabilization and post-conflict reconstruction programs. The government is ultimately responsible for providing protection for its citizens, including those who are internally displaced. It has stated repeatedly that the security situation in eastern Congo has vastly improved and it wishes to see displaced populations return home. Officials have incorporated displacement concerns in the rebuilding program for eastern Congo, the Stabilization and Reconstruction Plan for Areas Emerging from Armed Conflict (STAREC), to be jointly implemented by the government, the UN, and international donors.

The Congolese government’s view that civilian protection in eastern Congo is much improved has been challenged by Congolese civil society groups, national and provincial parliamentarians, and human rights and humanitarian groups. For example, in 2010 South Kivu members of Congo’s National Assembly wrote a letter of protest to the prime minister, Adolphe Muzito, saying, “We find it sadistic and irresponsible that your government declares without embarrassment that there is peace throughout [Congo] with only a few residual pockets of resistance in our province…. In nearly all territories [of South Kivu] insecurity continues.” The authors questioned whether the prime minister “lives in the same country as us” and called for UN peacekeepers to stay until the security situation improved.

One challenge in building a professional army and enhancing security for Congo’s IDPs and other citizens is integrating the numerous armed groups that previously fought the government and repeatedly targeted civilians. For example, after the CNDP agreed to integrate with the army, it was effectively allowed to maintain a parallel chain of command and to retain considerable control over areas it occupied. CNDP officers were awarded senior ranks in the army and the CNDP was given a leading role in the joint Congolese-Rwandan military operation—Umoja Wetu (“Our Unity” in Kiswahili) — launched against the FDLR in January 2009. The operation was marred by serious abuses against civilians by all sides, prompting renewed internal displacement.

In February 2009 Rwandan army soldiers officially withdrew from eastern Congo after five weeks of military operations. The FDLR militias had been forced from some of their military bases in North Kivu province and some had been disarmed, but they had not been defeated.

In March 2009 the Congolese army supported by MONUC peacekeepers launched a second military campaign in North and South Kivu against the FDLR. Operation Kimia II (“Quiet” in Kiswahili) produced a human rights and humanitarian catastrophe as tens of thousands of civilians fled their homes, sometimes for displacement camps around Goma, the capital of North Kivu province. By September 2009 Congolese authorities deemed that some areas of North Kivu, where it claimed to have removed the FDLR militia, were safe for the population to return. Five official IDP camps around Goma, housing some 60,000 IDPs, were closed and emptied almost overnight in what UN officials, diplomats, and others welcomed as a “spontaneous return.”

The reality was more complex. IDPs were put under official pressure to leave as the authorities sought to demonstrate that the Kimia II had created security conditions conducive to return—for both IDPs and Congolese refugees who had been in Rwanda since 1996. As people were leaving, armed police and bandits of youth raided the camps, looting belongings left behind, destroying latrines and other camp structures, and wounding numerous IDPs who had not yet packed up and left. It remains unclear how many IDPs actually returned home and were able to stay or instead joined the vast majority of their displaced compatriots staying with host families or in informal IDP settlements.

In late December 2009 Kimia II was suspended amid criticism of its disastrous humanitarian and human rights consequences. It was followed in January 201o by Amani Leo (“Peace Today” in Kiswahili), a MONUC-supported military operation. Unlike Kimia II, this aimed to target FDLR command bases, rather than broad-based operations. MONUC officials attempted to ensure that the Congolese army units it backed respected international humanitarian law and were not commanded by known human rights abusers. Still, many of the most abusive military officers continue to play important roles in eastern Congo, even if they are not directly involved in operations supported by UN peacekeepers. At least 115,000 more people fled their homes in the first three months of 2010 due to military operations and insecurity in the Kivus.

Protecting and Assisting the Displaced

The UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement set out rights and guarantees relevant to protecting and assisting IDPs during displacement, return, resettlement, and reintegration.

However, Congolese authorities have often proved unable, or unwilling, to follow these principles and have a poor track record when it comes to protecting IDPs. Since January 2009 specifically, the often-abusive behavior of Congolese army units has seriously hindered the government and the army’s abilities to effectively protect the population. Moreover, in the absence of state institutions and resources to assist eastern Congo’s war-ravaged population, the government has often relied on UN agencies and international and national humanitarian organizations for humanitarian assistance. These include the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO)—previously known as MONUC—a 20,000-strong force with a strong UN Security Council mandate to protect civilians “under imminent threat of physical violence” and to “assist in the voluntary return of … internally displaced persons.”

Focused in eastern Congo, MONUSCO has developed some innovative ways to enhance civilian protection, such as the development of a civilian protection strategy and the deployment of Joint Protection Teams (JPTs) to mediate disputes between non-integrated armed groups and the Congolese army or local population and to separate children from armed groups. However, like other organizations, MONUSCO suffers financial, security, and logistical constraints of its own, especially given Congo’s vast size and the shifting alliances of numerous armed factions. Other initiatives to help IDPs have also faced difficulties. In early 2009 international donors and UN agencies agreed that IDPs and their host families should receive assistance if needed. However, it has proved hard to ensure aid reaches most people in this situation. As a result, the challenge of protecting citizens remains immense.

Until September 2009 much assistance was channeled to UN agencies and NGOs working in the seven official IDP camps in Goma and the four official camps in Masisi. Some also went to agencies working with the estimated 135,000 IDPs living (as of late January 2010) in spontaneous sites. With five of the seven official camps in Goma now closed, aid is set to increase to IDPs in spontaneous sites; UNHCR’s camp management strategy has formalized management of and assistance to such locations. Keen to see the UN peacekeeping mission in Congo shrink in size and refocus on reconstruction, stabilization, and peace building, Congolese government officials, together with UN planners, have also begun to plan and implement stabilization and post-conflict reconstruction programs—even as military operations continue. This includes the Stabilization and Reconstruction Plan for Areas Emerging from Armed Conflict (STAREC)—the rebuilding program for eastern Congo that the UN, government, and international donors are due to implement jointly.

Protecting civilians, including IDPs, must remain of paramount concern in the coming months, as the government seeks to emphasize stabilization and reconstruction. The government must take all necessary measures to ensure that its security forces help protect IDPs fleeing to safety and are not themselves part of the problem. The UN and donors need to be vigilant that MONUSCO’s protection role does not diminish over time in the absence of credible alternatives. Moreover, IDPs should only be encouraged to return when they can return voluntarily in safety and dignity. However, as long as ongoing security problems continue to drive civilians from their homes, it is crucial that UN agencies, NGOs, and donors ensure that emergency humanitarian assistance programs are prioritized and receive sufficient resources and that assistance programs in return areas do not contribute to pushing IDPs home before it is safe for them to go.

Recommendations

To the Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo

- Immediately halt forced returns of IDPs and ensure that all returns are voluntary and fully comply with the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement.

- Take all measures necessary to end Congolese army abuses against IDPs at every stage of their displacement. Ensure the “zero tolerance” policy is fully applied when government soldiers commit human rights abuses.

- Ensure the Congolese army provides protection to IDPs, particularly when they are in insecure areas and seeking safety. Engage with UNHCR, OCHA, other UN agencies, and nongovernmental organizations willing to develop the government’s capacity to assist and protect IDPs under the UN’s protection policy.

- Ensure that IDP protection needs are a central part of the STAREC program and that the program is adequately financed and staffed.

To the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- Ensure full implementation of the UN System-Wide Strategy for the Protection of Civilians in the Democratic Republic of Congo, launched in January 2010 and co-led by UNHCR.

- Ensure that newly and previously displaced IDPs, returning refugees and IDPs, and communities hosting IDPs receive assistance based on vulnerability; ensure that assistance programs in return areas do not manipulate or force displaced people to return to home villages before it is safe; improve monitoring and analysis of the push and pull factors that keep IDPs in their site of displacement or encourage them to return home (or go elsewhere), so that the return process can be planned and managed in a way that ensures returnees receive the greatest protection possible.

- Improve monitoring of where displaced people go after they leave camps and other displacement sites to better understand whether they have returned to their home villages, other durable return areas, or secondary displacement sites.

- Improve the quality of the protection work of the UNHCR-chaired North Kivu Protection Cluster by:

- Urgently deploying a new Senior Protection Officer dedicated exclusively to coordinating the work of the Protection Cluster;

- Identifying more focused protection priorities on a regular basis;

- Expanding recent initiatives in North Kivu that follow the Congolese NGO-driven protection information system used in South Kivu, to ensure local residents provide agencies with a continuous flow of protection-related information;

- Producing quarterly reports that draw on NRC’s flash protection reports and other documents analyzing protection challenges that identify patterns of armed group activity leading to protection threats and that set out good and bad “lessons learned” guidance on agency responses to protection threats; and

- Ensuring that the protection cluster’s monitoring reports not only advocate for MONUSCO presence or specific actions in certain areas, but also request that humanitarian agencies undertake specific actions to strengthen protection.

To MONUSCO

- Help IDPs move to areas where they feel more secure and can access humanitarian assistance.

- Ensure full implementation of the UN System-Wide Strategy for the Protection of Civilians in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in particular, that MONUSCO addresses the specific protection needs and vulnerabilities of IDPs, including IDPs living in host families.

- Ensure that MONUSCO field base commanders maintain regular contact with displaced person representatives to ensure that IDP protection needs are identified and addressed.

- Ensure that MONUSCO peacekeepers carry out regular foot and vehicle patrols in the areas most at risk in their area of responsibility and provide escorts for civilians and, in particular, displaced persons fleeing violence or returning to home villages along roads or paths where they may face attack.

- Ensure all illegal roadblocks are removed in their area of responsibility.

- Ensure that Joint Protection Teams (JPTs) monitor areas to which IDPs are returning and make recommendations as to how MONUSCO can best help secure such areas.

To International Donors

- Ensure emergency humanitarian assistance programs receive sufficient resources and priority; urgently fill the UN’s funding gap for humanitarian programs; install a funding channel, reporting structure, and prioritization strategy that is independent of Congolese-government-led development and stabilization programs in eastern Congo.

- Ensure that assistance for newly and previously displaced IDPs, returning refugees and IDPs, and communities hosting IDPs, is based on vulnerability and that assistance programs in return areas—or encouragement by donors for agencies to launch programs in return areas—do not contribute to manipulating or forcing displaced people to return to their villages of origin before it is safe for them to do so.

- Significantly increase support for IDPs living with host families by funding agencies assisting IDPs in host communities, as well as their hosts.

- Fund shelter assistance for IDPs staying with host families to help minimize the need for IDPs to create spontaneous sites or to flee to official camps.

Methodology

This report is based primarily on research conducted in eastern Congo from April through mid-May 2009, with follow-up research carried out from June 2009 through April 2010.

Human Rights Watch conducted in-depth interviews with 146 internally displaced persons (IDPs) (71 women and 75 men) living with host families, in spontaneous sites, and in official camps in North and South Kivu. The vast majority had fled their homes during the previous 12 months and had been previously displaced an average of three to four times over many years.

Two researchers identified interviewees by explaining to representatives of internally displaced communities the broad type of information they were seeking. Locations were selected according to a number of criteria, including places that had recently seen an influx of IDPs and places where IDPs had lived in camps or host communities for some time.

In Goma, the center for humanitarian operations in the region, Human Rights Watch conducted a further 57 interviews with staff from United Nations agencies, national and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), donors, and local administrative authorities.

Where individuals or agencies requested that their interviews not be attributed to them, Human Rights Watch has withheld identifying those individuals or their agencies. For their safety, Human Rights Watch has also not published the names of any internally displaced persons or the people hosting them.

I. Conflict and Displacement in Eastern Congo

Our family fled our village in 2004, and we haven’t been able to go back since. We have lived in Kiwanja, but in three different places. For two years we were in a church because there was no assistance anywhere else. Then we moved to a camp for two years, but the CNDP came and destroyed it. Then we fled to live outside the MONUC camp. Now the local people want to close the camp, so then where should we go?

–A displaced woman, 33, Kiwanja, May 13, 2009

Recent Conflict in Eastern DRC

Buffeted by war, for the past 15 years the people of eastern Congo have endured widespread human rights abuses and the recurring displacement of millions of civilians. In recent years, the main fighting protagonists have been the Congolese army (Forces armées de la République démocratique du Congo, FARDC) and two rebel armed groups: a predominately Rwandan Hutu militia called the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda, FDLR), and the Congolese Tutsi-led National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, CNDP). Many smaller groups have also been involved in a maze of shifting alliances. At different times, both major armed groups have been either allies or enemies of the Congolese government, depending on the state of relations between the Congolese and Rwandan governments.

The FDLR—which the UN estimated in early 2010 to be about 3,200-strong— claims to be seeking greater political representation for ethnic Hutus in Rwanda.[1] The CNDP is the most recent of three different Rwanda-backed Congolese rebel groups (and sometimes splinter factions) that have agreed to fight the FDLR and other Rwandan Hutu militias, but which have all also sought to overthrow the Congolese government in Kinshasa.Until January 2009 the CNDP was led by a former Congolese Tutsi general, Laurent Nkunda, whose 4,000 to 7,000 fighters controlled large swathes of North Kivu.[2]

Throughout 2008 hundreds of thousands of people were displaced by clashes between the CNDP and a loose coalition comprising the Congolese army, the FDLR, the Coalition of Congolese Patriotic Resistance (Coalition des patriotes résistants congolais, PARECO), and other Mai Mai militia groups. By October 2008 the CNDP had taken over almost a third of North Kivu, killing and raping civilians as they advanced.[3]

In a dramatic shift of alliances, the Congolese and Rwandan governments on December 5, 2008, announced the start of joint military operations against the FDLR. One month later, Bosco Ntaganda, the CNDP’s chief of staff, removed Nkunda as leader. The International Criminal Court (ICC) has issued an arrest warrant for Ntaganda for crimes he is alleged to have committed in Ituri, northeastern Congo, between 2002 and 2004. Shortly after Rwandan authorities removed and detained Nkunda in Gisenyi, Rwanda, Ntaganda signed a cessation of hostilities agreement together with nine other senior CNDP officers, integrating the CNDP into the Congolese army to join operations against the FDLR.[4] Ntaganda was made a general in the Congolese army and served as de factodeputy military operations commander in the east.

On January 20, 2009, at least 4,000 Rwandan troops crossed the border into eastern Congo to fight the FDLR, the start of Operation Umoja Wetu (“Our Unity” in Kiswahili). The Rwandan troops, sometimes together with former CNDP troops, attacked a main FDLR base at Kibua, in Masisi territory (North Kivu), and other FDLR positions around Nyamilima, Nyabiondo, Pinga, and Ntoto (North Kivu). While there were some military confrontations, FDLR combatants often retreated into the surrounding hills and forests. On February 25, 2009, after 35 days of operations, the Rwandan army withdrew from Congo, in what was likely an agreed timeframe between Presidents Joseph Kabila of the DRC and Paul Kagame of Rwanda.[5] The military campaign was marred by serious abuses against civilians by all parties.[6]

Government representatives from both Rwanda and Congo emphasized that the mission was not complete and pressed MONUC to join forces with the Congolese army to conclusively defeat the FDLR. On March 2, 2009, the Congolese army, with the support of MONUC peacekeepers, launched the second phase of military operations, operation Kimia II (“Quiet” in Kiswahili).[7] While MONUC officials emphasized that Kimia II operations should respect international humanitarian and human rights law, it was not clear how this could be ensured or under what circumstances MONUC would withdraw its support if violations occurred. It was only in June 2009 that a policy establishing conditions for support began to be developed and it took until November 2009 to suspend support to one abusive Congolese unit. Congolese army officers allegedly responsible for war crimes and other serious international humanitarian law violations remained in positions of command.[8]

The Congolese government and MONUC announced the end of Kimia II in late December 2009, following heavy criticism of the operation’s disastrous humanitarian and human rights consequences. A new MONUC-supported Congolese army operation, Amani Leo (“Peace Today” in Kiswahili), was launched in January 2010. MONUC made an important effort to implement a new conditionality policy and to ensure that known human rights abusers do not command Congolese army units participating in jointly planned military operations. Nevertheless, many of the most abusive senior military officers have remained in operational command in North and South Kivu, even if they may not be involved directly in the MONUC-supported operations. Many operations have been carried out “unilaterally” by Congolese army units that do not get MONUC (or, as of July 1, MONUSCO) support.

Congolese armed forces continue to engage in serious abuses, including rape, summary executions, forced labor, and arbitrary arrests. As in previous military operations, soldiers have targeted and arbitrarily arrested civilians they accused of collaborating or sympathizing with the enemy. Civilians have also been forced to carry soldiers’ belongings; those who refused have been beaten or even killed.

The fighting and rampant abuses forced large numbers of civilians to flee their homes. In July 2009 the UN’s department for humanitarian operations concluded that “the humanitarian situation in North Kivu has continued to deteriorate since the beginning of 2009” as a result of Congolese army operations against the FDLR that were “causing massive displacement.”[9] The trend continued in the second half of the year. In January 2010 the UN concluded that the security situation in the east “remains very volatile and the humanitarian situation has deteriorated.”[10] During a visit to the DRC in late April 2010, John Holmes, United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, expressed his grave concern about the lack of protection of civilians and emphasized the continuing strong need for humanitarian assistance and humanitarian access. “Civilians continue to suffer enormously and disproportionately in this armed conflict,” he said after visiting IDPs in Mwenga, South Kivu. “While some have been able to return home, others are still being displaced, and armed groups are in many cases still preventing any return to normality.”[11]

Although the CNDP is now officially militarily and politically integrated, it maintains parallel military and administrative structures in much of the area it controlled as a rebel force, and there are continued reports of abuses by former CNDP combatants integrated into the Congolese army. This contributes to ongoing displacement and fear of returning to what are effectively CNDP-controlled areas. Civilians also continue to endure attacks from other elements of the Congolese army, as well as from a number of armed groups that have not yet integrated or have abandoned the integration process and some newly formed armed groups.

All parties to the conflict are bound by international humanitarian law (the laws of war). Both national armed forces and non-state armed groups are obligated to abide by article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, the Second Additional Protocol of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol II), and relevant customary international law.[12]

International humanitarian law requires the humane treatment of civilians and other persons no longer taking part in the hostilities, including wounded or captured combatants. It prohibits summary executions, torture and other ill-treatment, rape, and the recruitment of children as soldiers.

Humanitarian law also provides rules on the conduct of hostilities to minimize unnecessary civilian casualties and destruction of property. This includes prohibiting attacks directed at civilians that do not discriminate between civilians and military targets—and that cause civilian harm disproportionate to the expected military gain—or deploying forces that place civilians at unnecessary risk. There are also requirements relating to humanitarian access to provide relief to civilians.

Displacement in North and South Kivu

Since 1994 several provinces in eastern Congo have seen widespread displacement of civilians, who have fled dozens of armed groups spreading terror as they seek to extend economic, political, and military control over territory and resources. By mid-1994 there were about 500,000 IDPs in eastern Congo. That figure dropped to around 100,000 by the end of 1997, only to reach an all-time high of around 3.4 million IDPs in 2003, following five years of conflict. In 2006 this number fell to just over 1.5 million.[13] Throughout 2007 and 2008 clashes between the Congolese army, the CNDP, and other armed groups kept the number of IDPs—most of whom were in the Kivus—at about this same level.[14]

In the last few months of 2008 an estimated 250,000 people were displaced during fighting between the CNDP and the Congolese army.[15] Military operations in 2009 displaced another 1.1 million people in North and South Kivu.[16] In the first three months of 2010 a further 115,000 people fled their homes in the Kivus due to military operations and insecurity.[17] By April 2010 OCHA estimated that more than 1.1 million IDPs had returned—or tried to return—to their homes between January 2009 and March 2010.[18] Despite these attempted returns, over 1.4 million people remained displaced in North and South Kivu provinces by April 2010.[19]

Although these numbers broadly indicate the extent of displacement, they are estimates. The Congolese authorities and international agencies have been unable to collect reliable IDP statistics.[20] Registration challenges are greatest for IDPs living with host families.

Sanctuary

The UN estimates that of as May 25, 2010, 86 percent of IDPs in North Kivu lived with host families (often friends or relatives, but also strangers).[21] This figure is broadly consistent with general estimates of the percentage of IDPs in eastern Congo who live with hosts.[22]

Until 2007 almost all IDPs lived with host families and only a small number sought refuge in what aid agencies call “spontaneous sites” (locations where IDPs spontaneously settle such as churches, mosques, schools, or open fields near towns, villages, or MONUC bases). In mid-2007 increased fighting and longer-term territorial gains by armed groups put new pressures on host families and led more IDPs to seek refuge in spontaneous sites where, access permitting, aid agencies were able to provide some assistance.[23]

Starting in mid-2007, UNHCR brought some spontaneous sites within its Camp Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM) strategy, turning some into official displaced person camps and setting up new camps in anticipation of new IDP arrivals.[24] By late July 2009 seven official camps near Goma sheltered 67,480 IDPs (down from around 100,000 in January 2009).[25] In September 2009 five of the Goma camps were closed after UNHCR announced that all but a few of the tens of thousands of IDPs still living there in August had decided to return home (see below).[26] As of early February 2010 four camps in Masisi and Lushebere towns (70 kilometers from Goma), recognized as official camps since early 2008, continued to shelter 7,562 IDPs.[27]

In June 2009 UNHCR began the process of bringing more spontaneous sites within its IDP camp coordination response. Before June 2009, registration of assistance for IDPs in such sites was sporadic and limited. By March 2010 UNHCR had registered 117,051 IDPs in 46 spontaneous sites in North Kivu and 17,409 IDPs in camps and sites in South Kivu but had not yet extended its activities to cover them.[28]

Patterns of Displacement

In many conflict situations around the world, IDPs flee their homes and seek refuge in one location—including IDP camps where they can receive assistance for years—and then return home when fighting ends.[29] However, this is not the case in eastern Congo. As a result, national authorities and international agencies face huge protection and assistance challenges as they grapple with at least four main patterns of IDP displacement: remaining close to home; moving back and forth between villages and displacement sites; returning home for significant periods when violence subsides, only to flee again when it flares; and occupying abandoned property.

First, many IDPs in eastern Congo are anxious to remain near their homes so they can cultivate their fields. As a result, many risk their lives and properties by staying for weeks and even months in nearby forests or with host families in towns and villages– unsafe areas that lie beyond the reach of humanitarian agencies.[30]

Second, the need to find food and the desire to check on property drive many IDPs to move back and forth—sometimes even daily— between their displacement site and unsafe home villages. Nights may be spent, for example, in one place (usually a town or village), while the day is spent somewhere else (usually in fields near their homes). Aid agencies have struggled to devise effective protection and assistance in the face of such movement.[31]

Third, lulls in violence have allowed civilians to return home for months or even years before they have to flee again. In addition, once displaced, many IDPs move from one displacement site to the next, or even back and forth between different displacement sites, usually in a bid to escape insecurity or because limited or absent assistance leads them to try their luck elsewhere.[32] This multiple displacement also creates huge challenges for agencies that naturally find it easier to provide assistance to IDPs who stay over time in one location.[33]

Fourth, in some locations, IDPs seek refuge in previously abandoned villages and occupy land and houses, leading to inevitable tensions and to renewed displacement—either for the new occupiers or for the previous owners when the latter return home. The same happens when returning IDPs find their property occupied by fellow villagers who never left.[34] Often such land occupation flows from long-running land disputes and causes new disputes.[35]

The Particular Experience of IDPs

Eastern DRC’s conflict has affected the entire civilian population. For years Congolese and international agencies, including Human Rights Watch, have reported appalling levels of international human rights and humanitarian law violations against displaced and non-displaced civilians alike. These include killings, sexual violence, torture, beatings, abductions, and looting.[36]

However, IDPs in eastern DRC are often in circumstances that can make them especially vulnerable to rights abuses and create specific protection and assistance needs. These circumstances include complete isolation while displaced in the forest; encounters with armed groups while on the move, or in spontaneous sites and camps; and prolonged periods without livelihoods, shelter, and humanitarian aid, while displaced and after returning to insecure villages with limited state presence and rule of law.

In July 2008 the UN Secretary-General noted that victims of rape in North Kivu between March and June 2008 were “primarily” IDPs, while in January 2010 the UN highlighted the specific risks IDPs—especially displaced children— face in spontaneous IDP settlements and official camps.[37]An International Rescue Committee (IRC) study on mortality in the DRC found that between August 1998 and April 2007, 5.4 million people in Congo died from preventable and treatable conditions (such as malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia, and malnutrition) arising from “social and economic disturbances caused by conflict, including … displacement.”[38]

In addition, the Congolese army has in many areas been a source of insecurity for civilians, including IDPs, by attacking them instead of providing protection. Human Rights Watch previously reported how the UN peacekeeping mission in Congo, MONUC, struggled to implement its broad civilian protection mandate.[39] Its most recent civilian protection initiatives have focused primarily on preventing attacks on civilians in general, rather than IDPs in particular. This makes sense in a context where only a small proportion of IDPs live in settlements distinct from the wider population.

Despite the tens of millions of dollars that international donors have given programs assisting IDPs, little aid has reached the vast majority of IDPs who live with host families. These host families themselves have often been displaced in the past and live in poverty and constant fear. Much of the assistance has been channeled to agencies working in the seven official IDP camps in Goma that opened in late 2007 (until five of them closed in September 2009) and the four official camps in Masisi. Some has also gone to agencies working with IDPs in spontaneous sites, which, as of June 2009, started to be recognized as official IDP camps.

II. Abuses against IDPs

Causes of Displacement

Before the January 2009 launch of joint Congolese-Rwandan military operations against them, FDLR members lived and mixed with the Congolese population in numerous towns and villages across North and South Kivu. While relative harmony prevailed in some locations, the relationship was more violent in other areas, where the FDLR abused civilians as control of the zones by various warring parties moved back and forth.

One woman told Human Rights Watch, for example, that she fled her village in September 2008 because the FDLR soldiers were raping women in the fields during the day and in the houses at night. She fled from place to place, escaping the shifting front line:

My older sister was raped in her house that month [September 2008]. We fled to the fields, but the FDLR followed us there and so we fled to Kirumba. We went back in November but the same thing happened again and we fled again in January, to Bingi. We tried to go back in March [2009] but then we heard the Congolese army was coming and we were afraid the FDLR would punish us so we fled again, back to Kirumba.[40]

The rapprochement between Rwanda and Congo, realignment of military alliances, and subsequent military operations changed previously peaceful relationships between the FDLR and local Congolese communities. A significant cause of displacement in early 2009 was an FDLR strategy of unlawful retaliatory attacks against the civilian population to punish people for the government’s new policy and their perceived “betrayal.”[41] According to one man, when the FDLR learned that the Congolese-Rwandan forces were nearing Tembo village in March 2009, the rebels turned on the villagers and accused them of having called “the Tutsi” to attack the FDLR. The victims included four of the man’s children, aged between 12 and 18, whom the FDLR killed in broad daylight with machetes and hoes.[42]

Local authorities and health workers who had lived near FDLR positions for many years and knew the group well told Human Rights Watch they believed FDLR attacks on civilians may have been intended to cause a humanitarian disaster—including large-scale displacement—so that the Congolese government would be forced to call off military operations. This belief appears to be supported by a number of FDLR combatants who have left the group since January 2009 and entered the UN’s demobilization program.[43] The fighters told UN officials they were ordered to create a humanitarian catastrophe to press the international community to call off its support for the military operations against them.[44]

Human Rights Watch spoke to numerous IDPs in North Kivu who said they had fled from February to April 2009, when the FDLR burned down all or part of their villages before the imminent arrival of Congolese and Rwandan forces. A 46-year-old woman said,

At the end of March [2009], we heard the FDLR had burnt Biriko, Bongu, Katoyi, Katahunda, Kipopo, Nyakabasa, and Rambo villages and told the villagers it was because the Congolese army was coming, so we fled into the forest. On April 1 they [the FDLR] came and burned many houses in our village, including mine. My family had nothing left and we fled to the forest and then to Minova.[45]

In some cases, local Mai Mai fighters fought against the FDLR during the Congolese-Rwandan advance. When the FDLR returned, they took revenge against suspected Mai Mai. A 24-year-old man said,

After the army had left, the FDLR came back and accused us of being Mai Mai fighters, burned some of the village, and looted the remaining houses. We fled to the forest for a few days to see if things would calm down, but they came back three days later and burned more houses, so we fled to Minova.[46]

In June 2009 the FDLR were continuing to punish civilians for alleged “collaboration” with the Congolese army against the FDLR in North Kivu, including in southwest Masisi and Walikale territories and in South Kivu.[47]

Human Rights Watch also received reports that the FLDR prevented civilians from leaving their villages, as Congolese and Rwandan troops advanced, in order to use them as “human shields.”[48] For example, in early February 2009 the FDLR blocked people from fleeing Oninga village in northern Walikale territory. A displaced person from Oninga who managed to escape described what happened:

After the operations in Fatua, the FDLR came back to Oninga. But they knew the Congolese soldiers would come to chase them out, so they blocked all the paths into the village to keep the villagers there as human shields. The lucky ones managed to escape, but the majority of the population couldn’t leave.[49]

In April 2009 MONUC reported that territorial administrators and local NGOs had confirmed that the FDLR had surrounded villages and was holding civilians as human shields in Chibinda village (Kalonge area, Kalehe territory), Kasinda village (Ninja area, Kabare territory), and in Idunga village (Mumbili area, Shabunda territory).[50]

Attacks by the FDLR and other armed groups, sometimes allied with the FDLR, continued in 2010 after the launch of Amani Leo military operations, causing further civilian displacement in North and South Kivu. In early May 2010, armed elements attacked and killed seven people in Omate, Walikale territory, forcing the population to flee towards the towns of Mubi and Ndjingala.[51] Also, in early May 2010, FDLR combatants burned approximately 50 houses in Lubero Territory, North Kivu.[52]

The Congolese army and its allies have also perpetrated attacks on civilians resulting in displacement. Between January and September 2009, as newly integrated CNDP troops moved into territory previously controlled by the FDLR, many civilians fled their villages to escape serious abuses by Congolese and Rwandan soldiers accusing them of having supported the FDLR.[53] Such abuses by Congolese forces violate fundamental protections of international human rights and humanitarian law.[54] They also violate the DRC’s obligation under the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons to “ensure respect for … international law, including human rights and humanitarian law, so as to prevent and avoid conditions that might lead to arbitrary displacement.”[55]

Government soldiers and their allies destroyed homes and villages as they advanced, not only rendering vast numbers homeless, but killing or traumatizing them as well. A woman from Lukweti, whom Congolese army soldiers burned out of her home in March 2009, told Human Rights Watch that her six-year-old child was burned to death, and that she witnessed other civilians from her village being shot as they tried to flee. “The soldiers set fire to our house, and my son burned to death inside. They burned four other houses, and another baby boy burned to death inside one of them as well.”[56]

On February 14, 2009, coalition soldiers, retreating from a frontline position and reportedly angry that they had failed to find FDLR members, attacked the three neighboring villages of Lushoa, Mashuta, and Numoo, near the border of Walikale and Lubero territories, to “punish” the civilian population for having collaborated or lived with the FDLR. They burned 97 houses and a health center in Lushoa, 63 houses and three classrooms in Mashuta, and 13 houses in Numoo.[57] The next day, on February 15, coalition soldiers burned another 170 houses, a health center, two classrooms, and a school office in Bushalingwa village and 135 houses in neighboring Kishonja village.[58] The destruction of health facilities and schools violates laws of war prohibitions on the destruction of civilian objects, has increased the health risks to the population, and sharply curtailed children’s education.[59]

In March 2009 MONUC reported that IDPs had fled their villages in south Lubero territory, North Kivu, to escape the Congolese army’s so-called “Fast Integrated Brigades,” made up of former CNDP and PARECO forces.[60] Human Rights Watch spoke to numerous IDPs who had lived for years in areas under FDLR control who said they fled because Congolese and Rwandan forces treated them as if they were either active FDLR members or collaborators with the group. A 40-year-old man who fled his village after the Congolese army burned it down said, “They told us our daughters had married FDLR soldiers and that all of us were FDLR accomplices and had to be punished.”[61]

A man who had lived for many years in a village under FDLR control said that his village changed hands several times between January and March 2009 during fighting between the Congolese army and the FDLR. On March 8, Congolese soldiers burned down his village in retaliation for their losses at the hands of the FDLR:

The next day Congolese soldiers came to the forest and told me they had burned our village because the FDLR had killed a senior Congolese army officer and because the villagers supported the FDLR. I fled with my family to Kanyabayonga.[62]

Congolese army attacks on civilians, accompanied by horrific human rights abuses, have been a major cause of displacement, even where homes and properties have not been destroyed. For example, a Human Rights Watch researcher traveling along a 10-kilometer stretch of road between Nyabiondo and Lwibo in Masisi territory in October 2009, found all the villages between these towns completely deserted. This followed the Congolese army killing at least 83 civilians and raping numerous women and girls in the same area.[63]

In 2010 civilians continued to flee their homes following the launch of a new round of military operations against the FDLR and other armed groups, known as Amani Leo. As in previous military operations, soldiers have targeted and arbitrarily arrested civilians they accused of collaborating or sympathizing with the enemy. Civilians have also been forced to carry soldiers’ belongings and have been beaten or killed for refusing. On May 4, 2010, for example, Congolese army soldiers burned more than 20 houses on the road between Bunyatenge and Fatua, in the western part of Lubero Territory, North Kivu, reportedly because civilians in the area had refused to transport their military assets.[64]

Abuses during Flight

The Congolese army stopped us on the road near NyabIondo and said, “Why are you fleeing? We are coming to save you.” Then they stole all our things.

—A 30-year-old woman who lost everything as she fled her village in April 2009

IDPs remain seriously at risk when in flight. As in previous years, all parties have attacked IDPs as they fled, although often the exact identities of the perpetrators have not been clear to the victims. For example, around January 27, 2009, uniformed soldiers, who may have been Congolese coalition or Rwandan army soldiers, beat to death a 25-year-old man and his four-year-old daughter from Masiza village, near Bibwe, as they fled fighting. A witness said,

We were fleeing... we saw the soldiers just ahead of us. They told us to stop. I ran immediately into the forest. It was a big group of soldiers. They were wearing tache tache [camouflage] uniforms with little flags. The soldiers had radios with big antennas. We were a group of five civilians. My friend and his daughter were captured by the soldiers ... They asked my friend, “Where are the FDLR?” He replied that they had already fled. Then another soldier said, “No, this one here is an FDLR. We should kill him.” So they killed my friend and his daughter by beating them to death with a large stick covered with nails.[65]

Human Rights Watch also spoke with a number of people who witnessed the FDLR killing IDPs and raping women as they fled their villages.A woman whose relatives were killed, and who was raped while fleeing an attack in Manje village in July 2009, told Human Rights Watch what happened:

It was night when the bullets were flying in our village. We fled to the forest, but the FDLR found us on the path and accused us of being Mai Mai. Then they killed my father and my two brothers and raped me and my mother. My mother cried and then they shot her in the vagina and she died. They continued to rape me, and then they shot in the air and left.[66]

A woman interviewed by Human Rights Watch was raped and abducted by the FDLR while trying to flee an FDLR attack on Manje village (Walikale) in July 2009. She lost her mother, father, grandmother, and cousin during the attack, as well as 15 of her neighbors. She said,

They attacked at night, locked people in their houses, and then burned them with their homes. The bandits [FDLR] spoke Kinyarwanda and wore uniforms and found me while I was trying to flee and took me and other women into the forest to rape us. I was raped by at least four men, but then I lost consciousness and couldn't count them. I got pregnant because of the rape. They held me and nine other women and girls in the forest for one week.[67]

An 85-year-old woman was raped by five FDLR combatants in Bunje (Ufumandu) on July 2, 2009. Talking to a rape counselor, she said,

They found us on the path while we were running away from the bullets. We said we were fleeing and were tired and asked them to pardon us. Then one of them told me to put down everything I had and get on the ground. I said, “I'm like your grandmother, how can you do this?” They responded, “Our grandmothers stayed in Rwanda.” Then they beat me, dragged me to the forest by my legs and started to rape me, all five of them. Then they left and some of the passers-by helped me.[68]

Meanwhile, many IDPs told Human Rights Watch that the Congolese army had forcibly stopped their flight and forced them to carry soldiers’ belongings. For example, a 23-year-old woman who fled her village three times in nine months explained what happened during the third displacement in March 2009:

The Congolese army stopped us very close to Kasiki village. They said, “You are the Mai Mai who fought with the FDLR against us. Come with us and carry our bags.” Then they forced my husband and two other men to carry their bags. None of us have seen our husbands since.[69]

A 35-year-old man told Human Rights Watch that he fled his village on February 8, 2009, when he heard the Congolese army was on its way to fight the FDLR. The army stopped him and others on the way to Luofu village. Those able to pay a bribe were allowed to continue, but others, like him, who had no money, were forced to carry the soldiers’ belongings.[70]

Robbery of IDPs in flight has been extensive, perpetrated by the Congolese army, its allies, and the FDLR.[71] Dozens of IDPs told Human Rights Watch they fled their villages for safer places by going through the forest to avoid meeting Congolese soldiers on the main roads. Those who did flee on main roads often lost everything. For example, a 36-year-old man explained how, in April 2009, Congolese soldiers stopped his fleeing group, questioned their loyalty, and then robbed them:

Just before we reached Kanyabayonga a few days ago, the Congolese army stopped my family and many others and asked us for our electoral cards. When they saw we came from Walikale they said we were with the FDLR. We said we were citizens of Congo and that we were there before the FDLR came to the area. Then the soldiers told all the men to take all their clothes off, except for their trousers, to put all our belongings on the ground, and leave.[72]

IDP representatives in Kanyabayonga said that only months earlier in January 2009, the Congolese army had similarly, and systematically, robbed hundreds of fleeing families.[73]

On April 13, 2009, four FLDR combatants stopped a group of villagers from Kalevia (southern Lubero) as they fled combat in their villages towards Luofu. One villager said,

After we fled for the second time, we met the FDLR on the road to Luofu. They stopped us and said, “Where are you going? Who told you to leave? How do you know the enemy is coming? Are you in communication with them?” Then they told us to leave all of our baggage and give them all our money. They said they would kill anyone who didn't have money. So we gave them our baggage and money, and those of us who didn't have money asked for credit from a neighbor. We were a very large group: men, women, children, and old people.[74]

Meanwhile, Congolese army troops in the area were behaving similarly. One man, 47, told Human Rights Watch that Congolese soldiers stopped him and others as they fled, shot in the air, and stole all their belongings. Two days later, the same soldiers sold the stolen goods back to them in the market in Luofu village.[75]

III. The Search for Refuge

The FDLR came to the forest and raped some of the women, but I stayed because I was afraid to leave my field. I knew it would be hard to find food if I left my field.

–A 35-year-old woman fleeing her home in February 2009

The Protocol on the Protection and Assistance to Internally Displaced Persons, endorsed by the governments of the Great Lakes region, commits the Congolese government to ensuring that IDPs can remain in “safe locations away from armed conflict and danger.”[76] However, in reality most IDPs in eastern DRC face constant insecurity wherever they flee, whether they go to forests near their villages, host families in nearby towns, or far-flung camps.

Many IDPs brave significant risks to stay in their homes for as long as possible before fleeing. Some told Human Rights Watch they did so because they knew from past experience, or from previously displaced relatives, that they were unlikely to receive any food or other assistance once displaced. One 40-year-old man from Miriki told Human Rights Watch,

When the Congolese army came, the FDLR told us to leave, but we stayed. We were afraid of the fighting, but we also feared hunger and sickness if we left our fields and village. We knew how hard it is to get help when you leave your village. It’s only when the FLDR started beating us with sticks that we fled.[77]

A 35-year-old woman from Nyabiondo explained how she had risked attacks to avoid leaving her village:

The Congolese army came in early February [2009], and the FDLR fled. Other villagers who went to the fields nearby told me the FARDC and FDLR raped women there. I was afraid and wanted to leave, but I was displaced in 2003 and did not get help. I knew life would be tough, so I stayed at home for as long as I could. When my food ran out I had no choice, and I left the village.[78]

A 37-year-old man explained to Human Rights Watch that his decision to stay in the forest near his fields was because of a long history of hunger and inadequate humanitarian assistance for IDPs:

When I went back for a few days to find food I spoke to villagers who had stayed in the forest near our village and didn’t flee to Kanyabayonga like the rest of us. They told me they remembered their suffering between 1999 and 2004 when they fled the FDLR and came to Kanyabayonga but received no help from the government or organizations. They said it was better to stay near the fields than risk hunger and illness again.[79]

The Forest

Many IDPs have found themselves constantly on the move after fleeing, trying to avoid the shifting front line while staying as close as possible to homes and livelihoods. Most told Human Rights Watch they first took refuge in surrounding fields or forests—even though they risked attack and life-threatening conditions there—because they were close to home and food sources. Some said they were forced to stay in the forest because it was too dangerous to use the roads between their village and the next place of relative safety.

Entire villages have often been forced to survive for days or weeks in the forest. During the first week of February 2009, for example, 90 percent of the 10,000 people living in the Oninga area, 150-kilometers west of Pinga in Walikale territory, fled to the forest after clashes between the Congolese army and the FDLR.[80] In March 2009 MONUC reported that much of the population of Miriki village in south Lubero, including children, fled to the forest where they spent days trying to survive in dire conditions after Congolese army soldiers burned down 150 houses in their village.[81]

Many IDPs said that attacks or threats eventually forced them to flee further afield. A 21-year-old woman with two children and a baby, who fled to the forest in early March 2009 to escape FDLR forces, said,

We heard life in Luofu [on the other side of the front line] was bad for people who had fled there, with lots of hunger and sickness, so we stayed in the forest close to our field. We only fled when the FDLR followed us to the forest.[82]

A 54-year-old man in Kirumba related what happened to his daughter, who fled to the forest in February 2009 when the Congolese army came:

She wanted to be close to her field and feared her children would not eat if they left. But after three weeks, two of her children fell sick and died. One was about 18-months-old and the other about six-months-old.[83]

Refuge with Host Families, in Spontaneous Sites, and in Official Camps

During fighting in 2009, displaced persons fleeing their villages or the forest sought shelter in three kinds of locations: host families, spontaneous sites, and official camps.[84]

IDPs have generally preferred to live with host families close to their villages because they can regularly return to their fields and check on property, as previously described. They also often feel more physically and emotionally protected with host families than in sites or camps, even though host families are themselves often impoverished after years of conflict.[85] In south Lubero territory the average family said it had hosted IDPs on three or four occasions, each time for around three months, and that the number of people in the house almost doubled (from around 8 to 14 persons) during such periods.[86] In some locations, host families have hosted up to six IDP families for months at a time.[87] In many cases, the most vulnerable IDPs, especially the elderly, flee no farther than 10 to 15 kilometers from home.[88] Some IDPs told Human Rights Watch they preferred to live with host families because they had heard that children were not safe in the camps.[89]

However, in 2007, when the conflict in North Kivu intensified and armed groups held territory for longer periods, many IDPs were forced to seek refuge further from home. Brief home visits became more difficult or impossible. The extended stays of IDPs living with families sometimes caused tensions with their hosts. Consequently, many IDPs told Human Rights Watch they left for spontaneous sites or official camps. New IDPs began to go directly to spontaneous sites or camps as host families reached saturation.

Tensions between IDPs and host families often arise due to lack of resources and services, such as firewood, water, and sanitation facilities.[90] Sometimes the source of tension is even more basic—too many mouths to feed. A 51-year-old woman living in one Masisi camp said,

I fled with ten children—my own and my sisters’—and lived in a small room for one month. My hand was injured during our escape so I could not work in the fields. The family looking after us didn’t have enough food for all of us, so we argued. We had no choice and went to live in one of the camps.[91]

A large number of IDPs live in appalling circumstances, often in small ramshackle huts made of sticks that provide no shelter from the rain.[92] Many told Human Rights Watch that they lived and slept in extremely cramped conditions due to lack of space in the host family’s home. A 42-year-old man from Mahanga said,

For three months I have lived with my wife and 11 children in a single room, and we can hardly sleep because we don’t have the room to all lie down.[93]

A 45-year-old married man with five children from Nyabiondo reported,

When we arrived in Masisi we lived with a host family, but they complained about the pressure, so we left after three weeks. We wanted to go to the camps but the NGOs said they had no plastic sheeting, so I found some land and built a small hut which lets the rain through. My children are always sick and the land owner is trying to chase me away.[94]

Because of the burdens of hosting, host families often become just as economically vulnerable as their IDP guests.[95] A 45-year-old man from Lushoa with 10 members in his immediate family said,

For two months I have also looked after the families of two of my daughters, so we are now 18 people. Even before they came to live with us we were struggling to eat enough, but now all of us, including my children, eat less and even miss meals so we can all manage.[96]

A parish priest from Kaina said that in a culture in which visitors always eat first, followed by the host families’ adults and then children, many host family children often end up with no food.[97]

A 40-year-old man hosting different groups of displaced people in Minova since March 2008 said that he has received no help, despite hosting IDP families for weeks or months at a time:

It is bad. All we have now is a little manioc [staple food], which I use to feed my wife and six children. When we have food, our [IDP] guests eat. When we don’t, they don’t, and we all go to sleep hungry.[98]

Many IDPs who would try to survive without host families cannot do so because of an absence of material support. In 2009 local authorities in Masisi and Lushebere said that many IDPs had first sought refuge in the camps and had only opted for host families when they found no space or assistance there.[99] IDPs living with host families in Masisi and Lushebere confirmed this, saying they wanted to move to the camps but could not because agencies told them there was no plastic sheeting for new shelters.[100] Some aid agencies report that because of an absence of non-food-item (NFI) assistance—including plastic sheeting for hut roofing—IDPs who want, but cannot afford, to build their own shelter are forced to move in with host families.[101] In mid-2009 many IDPs in Minova, 40 kilometers west of Goma in South Kivu, were building temporary shelters in villages close to the camps while they waited for space to become available, rather than living with host families.[102]

A number of other factors influence IDPs’ decisions about where to live. Many IDPs “follow” others, so that when key people such as community leaders head for camps or create spontaneous sites, hundreds and sometimes thousands of others will follow.[103] In other cases, increased awareness of a predictable and consistent flow of aid in UNHCR-coordinated camps—in contrast to unpredictable or completely absent assistance in other locations—has led some IDPs to choose camps over other options.[104] Finally, in Masisi and Lushebere towns, an ethnic dimension has affected IDPs choices: as of May 2009 Hutus were seeking to live in camps while people from the Hunde ethnic group were choosing to live with host families, the vast majority of whom were also Hunde.[105]

In 2010 the vast majority of new IDPs again chose to live with host families. By May 25, 2010, about 86 percent of IDPs in North Kivu lived with host families. Twelve percent lived in camps, while the others lived in spontaneous sites. The most commonly cited cause of displacement in 2010 was armed attacks. In May 2010 OCHA estimated that 78 percent of the IDPs in North Kivu fled because of armed attacks, while others fled preventatively or for unknown reasons.[106]

IDPs Spontaneously Settling Next to MONUC Bases

In a number of places in North Kivu, including Kiwanja, Nyabiondo, Tongo, and Ngungu towns, IDPs have sought refuge right next to MONUC bases.

In one striking example, approximately 10,000 IDPs sought refuge in early November 2008 outside the MONUC base in Kiwanja after the CNDP (then still fighting the government) destroyed six IDP camps and public sites sheltering 27,000 IDPs in a crude attempt to destroy perceived pockets of opposition and to assert that CNDP-controlled territory was safe for IDPs to return home.[107] IDPs who fled to the MONUC base included those who had been in camps destroyed by the CNDP and who could not afford to pay rent to host families in Kiwanja.[108] They also included families from among the approximately 25,000 IDPs already living with host families whose houses had been attacked by the CNDP.[109] As of early February 2010 the site housed 3,330 IDPs, down from 12,000 when the camp was first formed in late October 2008.[110] In Nyabiondo, Masisi territory, many IDPs living with host families in March and April 2009 were so afraid of nocturnal Congolese army attacks and looting they began sleeping next to the MONUC base under the open sky.[111]

Temporary IDP Transit Sites

Many IDPs told Human Rights Watch they had left their first displacement site and moved closer to their villages for brief periods due to lack of assistance or because there were indications that security had improved in their home areas. In March and April 2009, for example, hundreds of IDP families left official IDP camps in Masisi and Lushebere due to a lack of help. However, continued insecurity meant they could not return home, and so they chose to instead live in small towns, such as Muheto, Nyakariba, and Nyamitaba, where they said they felt there was at least a minimum of security.[112] Around the same time, many IDPs facing assistance problems in the town of Kiwanja ended up displaced again in villages or towns such as Busanza and Jomba or on main roads near their original villages that remained inaccessible due to insecurity.[113]

The Risky Search for Food

We are like thieves in our own fields.

—Displaced man, Luofu, April 16, 2009.

According to IDP testimony and surveys carried out by aid agencies, many IDPs who receive no assistance are compelled to eat less and sometimes not at all—often for days at a time.[114] A 44-year-old woman living with 13 relatives in a host family said that everyone ate only once a day and that her children were constantly sick with diarrhea.[115] A 46-year-old woman with two children said,

I have been in Luofu for two months and received no help. When I am lucky I work for a full day in a local person’s field and get two handfuls of sweet potatoes for me and my children. But if I can’t find work, we don’t eat.[116]

The limited assistance available to most IDPs leads them to take desperate measures to survive. Many told Human Rights Watch that the lack of food meant they had little choice but to return for days or weeks to unsafe villages or forests near their fields. Some IDPs said they were so desperate they still went to such areas, despite specific threats against them. Many said they spent nights in the forest and briefly went to their fields by day, braving the constant threat of discovery by armed groups. Many humanitarian agencies also report that most IDPs’ main source of food and income is their own fields in insecure areas.[117]

In April 2009 IDPs and their representatives in Masisi and Lushebere towns and camps, Masisi territory, told Human Rights Watch that IDPs were returning to insecure villages, such as Butare, Kahira, Kanzenze, Muheto, and Nyamitaba, where many CNDP fighters had refused to integrate into the Congolese army because they had received no assistance for months and were desperate for food.[118] This was occurring even though local authorities said they were “not authorizing or encouraging” such returns because of ongoing insecurity in IDPs’ home villages.[119] IDPs and aid agencies reported the same practice elsewhere.[120]

Desperate to feed her six children, a pregnant 34-year-old woman told Human Rights Watch in April 2009 how she went back and forth to her village as the tide of fighting shifted:

In the last two months I fled my village twice. In February we fled to Luofu to escape the Congolese army fighting the FDLR. But life in Luofu was too difficult. I had almost no food. After five weeks I went back home for two weeks, even though the FDLR had come back and the Congolese army were close by. I fled again when I heard the army was coming back to the village.[121]

A 30-year-old man from Kinyana said he returned despite his fear of the CNDP:

I went back to my village in April [2009] for three days to find food. I saw others who had come back and slept at night in the forest. They said they feared the integrated CNDP who they said came at night to the village and stole peoples’ food, beat them, and accused them of collaborating with the government because they had fled to government towns. But the villagers said they preferred to sleep in the forest, looking for food by day and risking problems with the CNDP rather than starving in the camps in Masisi.[122]