On February 5, after minimal public discussion, Angola's new constitution entered into force. It was approved in late January by parliament, which has been dominated by the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA ) since 2008. The constitution consolidates the president's de facto powers over state institutions and prescribes a parliament-based model of electing the president, rather than separate elections.

In April parliament passed a law to curb Angola's endemic corruption, following the president's new "zero-tolerance" anti-corruption discourse. The law has not yet been implemented.

Fundamental rights such as freedom of expression and information became more curtailed in 2010, despite strong guarantees in the new constitution. The environment for human rights defenders remains restricted. Several human rights organizations have continued to struggle with unresolved lawsuits against banning orders, administrative registration obstacles, threats, and intimidation. In Cabinda province, two prominent human rights defenders were sentenced to prison on trumped-up charges following politically motivated proceedings.

Arbitrary Detentions in Cabinda

An intermittent armed conflict with a separatist movement has persisted in Cabinda since 1975, despite a peace agreement signed in 2006. The authorities have long used the conflict to justify restrictions on the rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and association in this oil-rich enclave. The government has not responded to calls for an independent investigation into allegations of torture and other serious human rights violations committed by the Angolan Armed Forces in Cabinda for many years. Perpetrators of torture there have not been prosecuted.

In 2010 the authorities used an armed attack on the Togolese football team on January 8, which killed two Togolese and injured nine others, as a pretext to arrest and convict prominent Cabindan intellectuals and government critics. The Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda, a separatist guerrilla group, claimed responsibility for the attack. The government has not carried out a credible investigation into the incident.

Only two of the nine men arrested between January 8 and April 11 were formally charged with direct involvement in the attack, and at this writing they are awaiting trial. Six others were formally charged and tried between June and September for unspecified "other crimes" against the security of the state, under article 26 of the 1978 law on crimes against the security of the state. This legal provision contradicts international human rights law because it is overbroad and does not specify the crimes for which the authorities may impose prison penalties.

Those convicted include: a Chevron worker who was arrested on January 8 and sentenced to three years of imprisonment in June; two prominent human rights defenders-Raúl Tati, a Catholic priest, and Francisco Luemba, a lawyer-who were arrested in January and sentenced to five years' imprisonment in August; and civic activist and university professor Belchior Lanso Tati and a former policeman who were also arrested in January and sentenced to six and three years, respectively, of imprisonment in the same trial. In September a former activist of the civic association Mpalabanda, arrested in January 2010, was tried and acquitted.

Another former Mpalabanda activist, António Paca Panzo Pemba, was arbitrarily arrested in April on suspicion of having organized a public demonstration in solidarity with these political detainees, together with two Angolan human rights organizations. In November, charges against him were dropped for lack of evidence. Five other activists were briefly detained and released provisionally in April for wearing and allegedly distributing t-shirts with the faces of political detainees printed on them. In November, two teachers were arrested and convicted to prison sentences for "inciting to civil disobedience." They had authored and distributed leaflets calling on the population to abstain from Angola's independence celebration on November 11.

Defense lawyers in August appealed to the Constitutional Court seeking revocation of article 26 of the 1978 state crime law. In September the Angolan Bar Association also filed a request regarding the same legal provision at the Constitutional Court. At this writing the Constitutional Court's decision is pending, and despite the approval of a revised law on crimes against the security of the state, the convicted persons remain in prison.

Media Freedom

The media environment in Angola remains restrictive, and the government continues to limit access to information, despite the emergence of a number of new media outlets over the past two years. The ruling party imposes a strong political bias in the state media. Authorities routinely limit the access of private media to official information and have curtailed space for open political debate on state and private radio stations, particularly in the provinces. They have also obstructed media coverage of politically sensitive events such as forced evictions. On November 4 the parliament passed a revised law on crimes against the security of the state, which contains provisions that restrict freedom of expression, for example by declaring "insult" of the president a criminal offense.

In September and October two journalists of the Luanda-based Radio Despertar, a radio station close to the opposition party UNITA, were attacked by unknown men. On September 5 the Radio Despertar journalist Alberto Tchakussanga was shot dead in his home. On October 22 the radio satirist António Manuel Jojó was stabbed in the street but survived. Both ran popular programs critical of the government and had previously received anonymous death threats. At this writing police investigations remain inconclusive.

Defamation remains a criminal offense in the new press law. Other offenses, such as "abuse of press freedom," are vague and thus open to political manipulation. No new defamation charges against journalists were reported in 2010, but a number of previous proceedings against journalists of the weekly newspapers Folha 8, A Capital, and Novo Jornal remain pending at this writing. Such litigation, in an increasingly difficult economic environment for the private media, perpetuates a widespread culture of self-censorship that restricts the public's access to independent information.

A new press law was enacted in May 2006 but the additional legislation required to implement crucial parts of the law, which would improve the legal protection of freedom of expression and access to information, have still not passed at this writing. Independent private radio stations cannot broadcast nationwide, while the government's licensing practices have favored new radio and television stations linked with the ruling MPLA and the presidency. The 2006 press law contains provisions that prevent the establishment of media monopolies and require disclosure of shareholders of media corporations. Yet, the real shareholders of companies registered as owners of several media corporations established since 2008, which are reportedly linked to the presidential entourage, have not been disclosed. In June a company reportedly linked to the president bought three of the most popular weekly newspapers known for their government criticism, Semánario Angolense, A Capital, and 40 percent of Novo Jornal.

Freedom of Assembly and Demonstration

The new constitution guarantees freedom of assembly and peaceful demonstration, and Angolan laws explicitly allow public demonstrations without the need to obtain government authorization. However, in 2010 the authorities arbitrarily banned two public demonstrations organized by civil society organizations, publicly threatened demonstrators, and deployed security forces to prevent the demonstrations. In November the police also temporarily detained peaceful demonstrators and opposition party activists in Luanda who were peacefully distributing leaflets.

In March a demonstration against mass forced evictions and demolition of houses in Huila, organized by the human rights organization Omunga, was banned by the governor of Benguela province. The governor deployed hundreds of police agents and publicly rejected "any responsibility" for the resulting physical damage or harm to the protesters. The demonstration later took place on April 10 following local and international pressure. In May the governor of Cabinda banned a public demonstration organized by civil society groups in solidarity with civilians jailed on suspicion of state security crimes after the January 8 guerilla attack. The governor deployed police and military to prevent the demonstration from taking place on May 22. The military and police also surrounded the organizers' houses on the day of the demonstration, despite the demonstration being called off by its organizers.

Housing Rights and Forced Evictions

Angola's laws do not give adequate protection against forced eviction, nor do they enshrine the right to adequate housing. In 2010 the government continued to carry out mass forced evictions and house demolitions in areas that it claims to be reserved for public construction in Luanda and increasingly also in provincial towns. This has occurred without adequate prior notice or compensation in several documented cases.

Between March and October an estimated 25,000 residents were forcibly evicted from their homes in Huila, without compensation or adequate prior notice, and resettled in peripheral areas without any infrastructure, driving many of the evicted into extreme poverty. In March the government ordered the destruction of at least 3,000 residences in Lubango, Huila province to clear railway lines. Demolitions have proceeded despite massive public criticism of the evictions by civil society organizations, the Catholic Church, opposition parties, the parliament, and a public apology by the Minister of Territorial Administration. In September and October the government has demolished at least 1,500 houses and annexes at the riverside in Lubango to make way for an urban beautification project.

Key International Actors

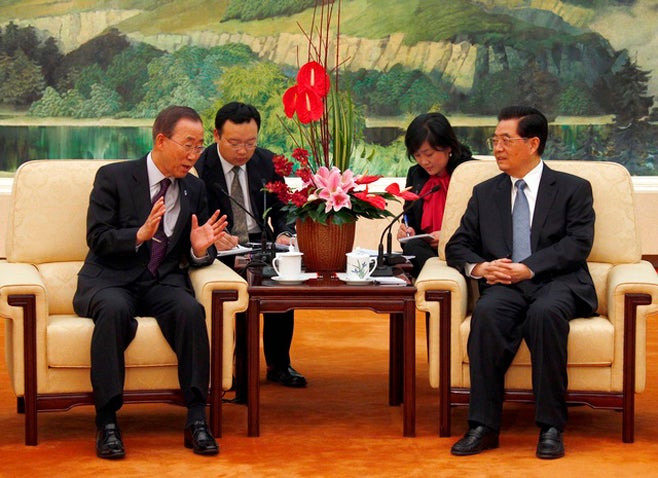

Angola remains one of Africa's largest oil producers and is China's second most important source of oil and most important commercial partner in Africa. This oil wealth, and Angola's regional military power, has greatly limited leverage of other governments and international organizations pushing for good governance and human rights. Trade partners remain reluctant to criticize the government, to protect their economic interests. Since 2009 falling oil and diamond prices and the global economic crisis have forced the government to invest more efforts to seek support from international partners, including the International Monetary Fund with which Angola signed a Stand-by-Arangement in November 2009.

In February Angola underwent the Universal Periodic Review at the United Nations Human Rights Council. Angola adopted a number of important recommendations from member states. However, it did not issue a standing invitation to all UN special rapporteurs, as requested by a number of member states as well as local and international human rights organizations. In May Angola was re-elected as a member of the Council and reiterated its pledge to sign or ratify all major international human rights instruments. However, none of the pending signings or ratifications has taken place despite a previous pledge in 2007.