The May inauguration of President Goodluck Jonathan, following the death from natural causes of President Umaru Yar'Adua, brought hope for improvements in Nigeria's deeply entrenched human rights problems. Jonathan's removal of the attorney general, under whose watch impunity flourished, and his appointment of a respected academic to replace the discredited head of the electoral commission, who presided over phenomenally flawed elections, were widely viewed as positive first steps. Yet major challenges remain.

During the year, episodes of intercommunal violence claimed hundreds of lives, while widespread police abuses and the mismanagement and embezzlement of Nigeria's vast oil wealth continued unabated. Perpetrators of all classes of human rights violations enjoyed near-total impunity. A spate of politically motivated killings by Islamist militants in the north, and continued kidnappings and violence by Niger Delta militants - including the brazen Independence Day bombing in Abuja, the capital, for which they claimed responsibility -raised concern about stability in the run-up to planned 2011 general elections.

The National Assembly again failed to pass legislation to improve transparency, notably the Freedom of Information bill, but approved a watered-down version of an electoral reform bill. Nigeria's judiciary continues to exercise a degree of independence in electoral matters and has, since 2007, overturned more than one-third of the ruling People's Democratic Party (PDP) gubernatorial election victories on grounds of electoral malpractices and other irregularities. Meanwhile free speech and the independent press remained fairly robust. Foreign partners took some important steps to confront endemic corruption in Nigeria, but appeared reluctant to exert meaningful pressure on the government over its poor human rights record.

Intercommunal and Political Violence

Intercommunal, political, and sectarian violence has claimed the lives of more than 14,500 people since the end of military rule in 1999. During 2010, episodes of intercommunal violence in Plateau State, in central Nigeria, left over 900 dead. In January several hundred were killed in sectarian clashes in and around the state capital of Jos, including a massacre on January 19 that claimed the lives of more than 150 Muslims in the nearby town of Kuru Karama. Shortly thereafter, on March 7, at least 200 Christians were massacred in Dogo Nahawa and several other nearby villages. In the months that followed more than 100 people died in smaller-scale attacks and reprisal killings in Jos and surrounding communities. Meanwhile intercommunal clashes in Nassarawa, Niger, Adamawa, Gombe, Taraba, Ogun, Akwa Ibom, and Cross River states left more than 110 dead and hundreds more displaced. State and local government policies that discriminate against "non-indigenes"-people who cannot trace their ancestry to what are said to be the original inhabitants of an area-exacerbate intercommunal tensions.

Widespread poverty and poor governance in Nigeria have created an environment where militant groups thrive. In Bauchi State in December 2009, violent clashes between government security forces and rival factions of a militant Islamist group known as Kala Kato left several dozen dead, including more than 20 children. Between July and October 2010, suspected members of the Boko Haram Islamist group killed eight police officers, an Islamic cleric, a prominent politician, and several community leaders in the northern city of Maiduguri, and in September attacked a prison in Bauchi, freeing nearly 800 prisoners, including more than 100 suspected Boko Haram members.

Targeted killings and political violence increased ahead of the 2011 elections. In January 2010 Dipo Dina, an opposition candidate in the 2007 gubernatorial elections in Ogun State, was gunned down. In a series of attacks in Bauchi State in August, gunmen killed two of the state governor's aides and a security guard for an opposition candidate for governor, and injured several others. Meanwhile, the Nigerian government has still not held accountable those responsible for the 2007 election violence that left at least 300 dead.

Conduct of Security Forces

Again in 2010, members of the Nigeria Police Force were widely implicated in the extortion of money and the arbitrary arrest and torture of criminal suspects and others. They solicited bribes from victims of crimes to initiate investigations, and from suspects to drop investigations. They were also implicated in numerous extrajudicial killings of persons in custody. Meanwhile senior police officials embezzle and mismanage funds intended for basic police operations. They also enforce a perverse system of "returns," in which rank-and-file officers pay a share of the money extorted from the public up the chain of command.

The government lacked the will to reform the police force and hold officers accountable for these and other serious abuses. At this writing, none of the police officers responsible for the brazen execution of the Boko Haram leader, Mohammed Yusuf, and dozens of his suspected supporters in Maiduguri in July 2009 have been prosecuted. Similarly, the government has still not held members of the police and military accountable for their unlawful 2008 killing of more than 130 people during sectarian violence in Jos, or for the 2001 massacre by the military of more than 200 people in Benue State, and the military's complete destruction of the town of Odi, Bayelsa State, in 1999.

Government Corruption

Nigeria made limited progress with its anti-corruption campaign in 2010. The national Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) indicted more than a dozen politicians and senior government officials on corruption charges, including a former federal government minister, a former state governor, and a handful of state officials. However, the EFCC failed to indict other senior politicians implicated in the massive looting of the state treasury, including former Rivers State governor Peter Odili.

Key convictions included that of a powerful banker, sentenced to six months in prison in October, and a former head of the national anti-drug agency, sentenced to four years in prison in April for taking bribes from a criminal suspect, the longest sentence handed down to a government official to date. Meanwhile, the governing elite continues to squander and siphon off the country's tremendous oil wealth, leaving poverty, malnutrition, and mortality rates among the world's highest.

Targeted attacks against anti-corruption officials increased significantly in 2010. Gunmen in three separate incidents shot and killed anti-corruption personnel, including the head of the forensic unit and a former senior investigator. Still, Nuhu Ribadu, the former EFCC head, returned to Nigeria in June, after fleeing the country in 2009 following what he believed to be an assassination attempt.

Violence and Poverty in the Niger Delta

Following a lull in violence in the oil-rich Niger Delta, attacks increased, including kidnappings of schoolchildren, wealthy individuals, and oil workers, and car bombings in Delta State, Bayelsa State, and Abuja. The 2009 amnesty - in which a few thousand people, including top militant commanders, surrendered weapons in exchange for cash stipends - led to a reduction of attacks on oil facilities in 2010, but their disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration have been poorly planned and executed. The amnesty has further entrenched impunity, and the government has made little effort to address environmental degradation, endemic state and local government corruption, or political sponsorship of armed groups, which drive and underlie violence and poverty in the region.

Human Rights Concerns in the Context of Sharia

In northern Nigeria 12 state governments apply Sharia law as part of their criminal justice systems, which include sentences such as the death penalty, amputations, and floggings that amount to cruel, inhuman, and degrading punishment. Serious due process concerns also exist in Sharia proceedings, and evidentiary standards in the Sharia codes discriminate against women, particularly in adultery cases.

Death Penalty

There are about 870 inmates, including over 30 juvenile offenders, on death row in Nigeria. Although Nigeria has an informal moratorium on the use of the death penalty, state governors in 2010 announced plans to consider resuming executions to ease prison congestion.

Freedom of Expression and the Media

Civil society and the independent press openly criticize the government and its policies, allowing for robust public debate. Yet journalists are subject to intimidation and violence when reporting on issues implicating the political and economic elite. Edo Ugbagwu, a journalist with The Nation, one of Nigeria's largest newspapers, was gunned down at his Lagos home in April. In Jos two journalists with a local Christian newspaper were killed in sectarian clashes in April, while a Muslim journalist from Radio Nigeria was badly beaten in March, in an attack the journalist said was incited by a state government official.

Key International Actors

Because of Nigeria's role as a regional power, leading oil exporter, and major contributor of troops to United Nations peacekeeping missions, foreign governments-including the United States and the United Kingdom-have been reluctant to publicly criticize Nigeria's human rights record.

US government officials did speak out forcefully against the country's endemic government corruption and took an important first step to back up these words by revoking the visa of former attorney general Michael Aondoakaa. The UK government continued to play a leading role in international efforts to combat money laundering by corrupt Nigerian officials, demonstrated by the May arrest in Dubai of the powerful former Delta State governor, James Ibori, on an Interpol warrant from the UK, and the conviction of two of his associates in an English court in June for laundering his funds. However, in fiscal year 2010, the UK increased funding to £140 million (US$225 million) in aid to Nigeria, including security sector aid, without demanding accountability for Nigerian officials and members of the security forces implicated in corrupt practices and serious human rights abuses.

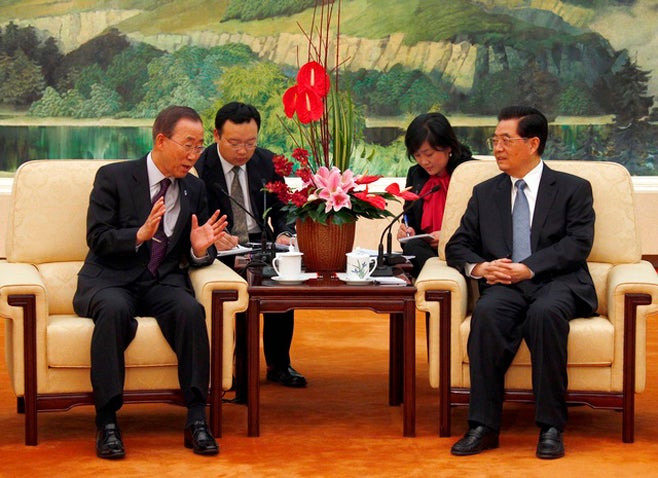

The UN secretary-general expressed his concern about the intercommunal violence in Jos, but at this writing a mission by his special adviser on the prevention of genocide is stalled due to resistance from the Nigerian government.