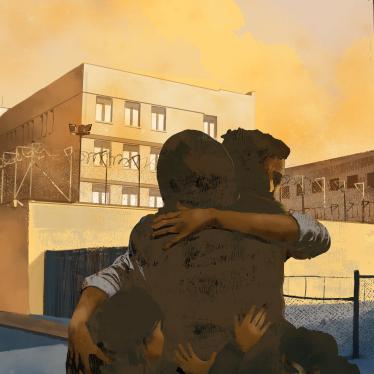

The US Supreme Court should uphold the right of non-citizen detainees to challenge the lawfulness of their detention through habeas corpus, and military commission prosecutions should be transferred to federal court, Human Rights Watch said today.

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court and the Guantanamo military commissions will each hear arguments on crucial issues concerning Guantanamo detainees.

“In the almost six years since Guantanamo opened, only one person has been convicted of any crime and that was by plea agreement,” said Jennifer Daskal, senior counsel on counterterrorism for Human Rights Watch. “It’s time to shut the door on this system of lawless detention and restore the place of the federal courts in reviewing executive detentions and bringing suspected terrorists to justice.”

In the twin cases of Boumediene v. Bush and Al Odah v. United States, the Supreme Court will hear challenges from Guantanamo Bay detainees to laws that prohibit them – and all other non-citizens the president declares to be “enemy combatants” – from seeking judicial review of their detention via the age-old writ of habeas corpus.

On the same day, a military commission judge will hear arguments as to whether Salim Hamdan, the 36-year-old Yemeni who successfully challenged – via habeas – the legitimacy of the initial military commissions authorized by President Bush in 2001, can be tried by the military commissions approved by Congress in 2006.

The Supreme Court Case

Boumediene v. Bush and Al Odah v. the United States will mark the second time that the Supreme Court considers whether Guantanamo detainees have a right to bring habeas challenges to the legality of their detention. On June 28, 2004, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in Rasul v. Bush that the federal courts had habeas jurisdiction over Guantanamo.

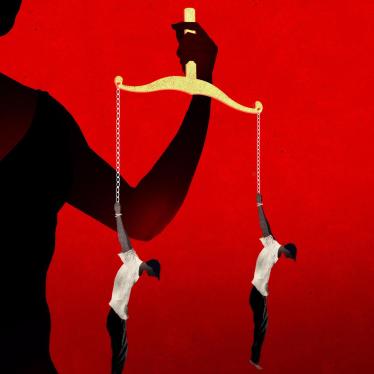

The impact of that case was undermined, however, by Congress’s December 2005 passage of the Detainee Treatment Act, which barred Guantanamo detainees from bringing new statutory habeas claims. The following year, Congress expanded these restrictions in the Military Commissions Act of 2006, which prevents any non-citizen that the president determines to be an “enemy combatant,” including any of the 11.6 million legal permanent residents in the United States, from challenging his or her detention via habeas corpus.

Congress also made the stripping of habeas retroactive, resulting in the dismissal of already pending cases.

As an ostensible substitute for habeas, Congress provided extremely limited federal court review of the Pentagon-created and Pentagon-run administrative review process – called Combatant Status Review Tribunals, or CSRTs – initiated days after the Rasul decision to ascertain detainees’ “enemy combatant” status. Under the law, federal court review is limited to the question of whether the CSRT process is lawful and whether the Pentagon followed the rules and regulations that it wrote in creating the CSRTs.

The question now before the Supreme Court is two-fold: Are these habeas-stripping provisions constitutional? And is federal court review of CSRTs an adequate and effective substitute for habeas? Human Rights Watch said that the court should uphold habeas, the most fundamental of rights protecting individuals from the overreach of governmental power.

“Over 300 men who have never been charged with any crime remain locked up in Guantanamo,” said Daskal. “It’s high time for the Supreme Court to step in and provide an independent and meaningful review of the decision to detain.”

The administration claims that these are wartime detentions that should not be subject to habeas oversight. But despite being labeled “enemy combatants,” many of the detainees were picked up far from any battlefield. Hundreds were sold to the United States by bounty hunters, often for thousands of dollars. Several US military and counterterrorism experts have now acknowledged that errors were made about those taken into custody.

The administration also claims that even if the Supreme Court concludes that the Constitution requires habeas, the alternative congressionally-created CSRT review is a sufficient substitute. The Supreme Court should reject this argument, Human Rights Watch said.

The CSRTs are under the chain of command of the president, who has already publicly announced that all Guantanamo detainees are enemy combatants. Detainees are not told anything but the most cursory summaries of the evidence against them – making it near impossible to refute. Moreover, detainees are not provided legal counsel, but rather a “personal representative” who also works under the command of the executive. Detainees have been prevented from bringing in any outside (non-Guantanamo-based) witnesses to contest the claims against them, and the CSRTs allow reliance on evidence even if obtained through torture.

Stephen Abraham, an Army lieutenant colonel who worked for six months at the Pentagon that ran the CSRTs, filed a sworn statement with the Supreme Court exposing the defects of the CSRT process. He stated that the evidence relied on by the CSRTs was often outdated, generic, and cursory, that requests for additional information were often denied, and that agencies supplying the information refused to certify that all exculpatory information had been provided. Abraham said that after one of his panels concluded that a detainee should be cleared of the “enemy combatant” designation, his superiors questioned the finding’s validity and ordered the panel to “reopen” the hearing. His panel stuck with its original conclusion, and Abraham was never assigned to a CSRT panel again.

“Past practice demonstrates that there is no way that review by the deeply flawed Combatant Status Review Tribunals can serve as an adequate substitute for habeas,” Daskal said.

Dozens of former diplomats, military officers, and federal judges have weighed in with the Supreme Court, urging the justices to restore meaningful court review of the basis of detention decisions. Human Rights Watch, along with a bipartisan coalition of human rights and civil liberties groups, has filed a brief with the court warning of the dangers of unchecked executive power and urging the same.

The Supreme Court originally declined to hear the Boumediene and Al Odah cases, but reversed course in June 2007 in a highly unusual move. Whereas only four of the nine Supreme Court justices need to agree to take the case in the normal course of business, reversal requires a five-justice majority.

The Military Commission Hearing

Salim Hamdan will appear before a military commission on Wednesday, December 5, in what will be the government’s third attempt to bring a case against him.

“The United States should give up its failed attempts at an alternative form of Guantanamo justice and simply try these men in federal courts. The courts are perfectly capable of hearing terrorism cases,” said Daskal.

Hamdan’s first prosecution was halted in November 2004, when a federal district court judge ruled that the commission proceedings were unlawful – a conclusion that was ultimately confirmed by the Supreme Court in a June 2006 ruling, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld.

Congress responded by authorizing a new set of commissions (part of the same Military Commissions Act that stripped away habeas rights), with jurisdiction over any non-citizen found to be an “unlawful enemy combatant.” But in June 2007 a military commission judge determined that no competent body had ever made this determination, and dismissed the case. Although a Combatant Status Review Tribunal had determined that Hamdan was an enemy combatant, it had never labeled him an “unlawful” enemy combatant.

In September 2007, a military commissions appellate court reversed an analogous ruling in another case, and Hamdan’s judge is now reconsidering his dismissal. He has ordered the parties to present evidence as to Hamdan’s “unlawful enemy combatant” status.

The commission is expected to decide Hamdan’s status at the hearing that begins on Wednesday – marking the first time that a military commission will determine whether a Guantanamo detainee can be qualified as an “unlawful enemy combatant.”

Hamdan, who has admitted to working as a driver for Osama bin Laden prior to October 2001, is accused of providing material support to terrorism, and of conspiracy to commit terrorism. He has argued that he must be considered a prisoner of war unless and until the government proves otherwise beyond a reasonable doubt.

Background

Of the 305 detainees still being held at Guantanamo, only three are currently subject to military commission charges. In addition to the case against Hamdan, the government has charged Omar Khadr, a 21-year-old Canadian who has been in US detention since he was 15, and Mohammad Jawad, a 22-year-old Afghan who has been in US custody since he was 17.

Khadr’s trial is scheduled for May 2008. When Khadr was arraigned in November, the military commission judge presumed Khadr qualified as an “unlawful enemy combatant” without hearing evidence to support that status. The case against Jawad has not yet been formally referred for trial and therefore he has not yet appeared before a commission.

The only person to be convicted by the military commissions – David Hicks – pleaded guilty in April 2007 to providing material support to terrorism and is now finishing the last weeks of his nine-month sentence in his native Australia.

The sentencing of Jose Padilla – who was labeled an “enemy combatant” and held without charge in military custody for more than three years before being transferred to federal court, charged, and convicted – is also scheduled for December 5.

Join an online discussion of this issue in the "Rights Watchers" forum, hosted by Human Rights Watch and the Washington Post