It is an iron law of American government that institutions created to meet a temporary contingency are almost impossible to dismantle once the contingency has passed. If not for the Soviet threat, for example, the United States hardly would have established multiple intelligence agencies, military bases in Germany or a massive nuclear weapons complex. Yet 20 years after the Berlin Wall fell, these elements of the Cold War national security state are still with us.

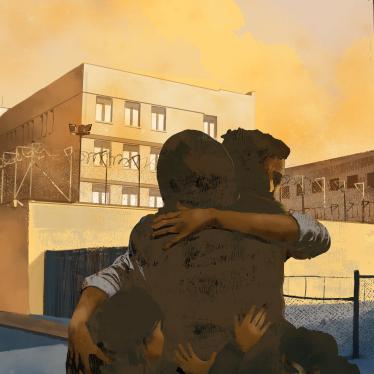

The institutions cobbled together after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks may be just as resistant to change, as President Obama is finding in his struggle to close the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay.

In 2008, presidential candidates Obama and John McCain promised to close Guantanamo. (McCain said he would move all the prisoners to Fort Leavenworth, Kan., on his first day in office.) But last year, Robert Gates's Pentagon fought to preserve the facility's military commissions. Then, Congress restricted transfers of prisoners to the United States for detention or trial. Last week, White House press secretary Robert Gibbs said that closing Guantanamo would "depend on the Republicans' willingness to work with the administration," which, if true, is a nice way of saying "never."

Now Obama is reportedly weighing an executive order to clarify the rules for detaining some four dozen Guantanamo prisoners whom his administration deems too dangerous to release but who cannot be tried. These men pose a unique problem left over from the Bush administration, when evidence was poorly maintained, some detainees were tortured and others radicalized by their years in prison. If Obama's order gives them better process, it will be a step forward.

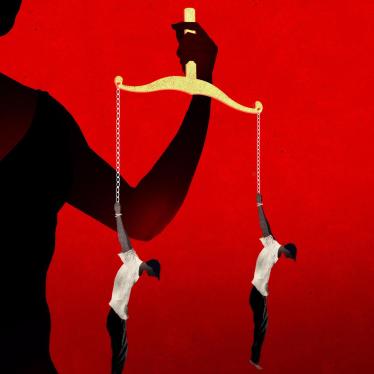

Some, however, are urging Obama to take a more fateful step: to issue an order covering not just the hard cases he inherited in Guantanamo but also allowing detention without trial of any terrorism suspect who may be apprehended in the future, even if far from a battlefield. Such an order could transform the Guantanamo system from an unfortunate, improvised response to Sept. 11 into a permanent feature of our legal landscape.

Proponents, including The Post's editorial board, argue that in places such as Yemen and Somalia, the United States will inevitably capture terrorism suspects who must be held but cannot be prosecuted, so it needs a process for detaining them without trial. Some have charged that the government must now be killing such men or letting them go, because it has no place to put them.

In fact, the "impossible to prosecute but too dangerous to release" problem is the legacy of a period in 2002 and 2003 when hundreds of alleged low-ranking militants were brought to Guantanamo with no legal process. From 2004 on, the Bush administration brought only 18 terrorism suspects who were detained beyond the Iraqi and Afghan war zones into long-term U.S. custody. These men were all accused of significant involvement in terrorism and would have been excellent candidates for prosecution had the Bush administration wanted to try them. During the Obama administration, there has also been no reported case of a terrorism suspect captured or targeted abroad whom the government deemed worthy of long-term detention but who could not be prosecuted in U.S. courts.

A new system of indefinite detention without trial is therefore not needed. But if one were established, the government would always be tempted to use it. Criminal trials may provide certainty and legitimacy in the long term, but why go to the trouble if you can hold people without charge instead?

And even if Osama bin Laden were killed or captured and the current "war on terror" deemed won, there would still be people who threaten America's security. Would any future president voluntarily relinquish the power to detain them indefinitely if Obama, with his liberal bona fides, felt it was consistent with America's traditions? Would future presidents always use this power responsibly - and only against real terrorists? Ask presidential hopeful Newt Gingrich about Julian Assange and WikiLeaks, and you'll see how almost anyone considered dangerous can be labeled an "enemy combatant."

Of course, if Obama sticks to his beliefs and brings terrorists to justice in U.S. courts, his enemies will vilify him and his friends won't necessarily defend him. When it comes to national security, one side employs the politics of fear; the other suffers from a fear of politics. The White House and its allies have been reluctant to engage in the political contest required to defend the counterterrorism policies they believe are in the country's best interest.

But even as he untangles George Bush's legacy, Obama must be careful not to leave a worse one. He wants to be the president who closed Guantanamo. A permanent system of detention without trial would normalize it. That is an outcome worth fighting to avert.