(San Francisco) – Indefinite detention of asylum-seeking mothers and their children in the United States takes a severe psychological toll, Human Rights Watch said today. Mothers from 25 detained families, including 10 who had been locked up for 8 to 10 months, described to Human Rights Watch their family’s trauma, depression, and suicidal thoughts.

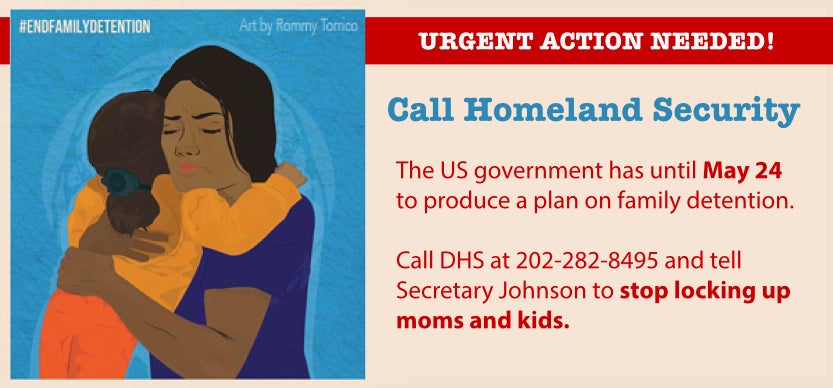

The Obama administration has until May 24, 2015, to propose a plan in response to a federal judge’s preliminary ruling that family detention violates a binding settlement on the rights of migrant children. US authorities should immediately release migrant families detained after entering the United States to seek asylum, Human Rights Watch said.

“The Obama administration has now kept traumatized children and their mothers locked up for nearly a year,” said Clara Long, US researcher at Human Rights Watch. “They have no idea when they will be released, and they are terrified to be deported back to places where they could be killed, raped, or otherwise harmed.”

US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which has responsibility for immigration detention centers, announced on May 13 that it would create new oversight mechanisms for family detention. It said that it would no longer make the argument in individual cases that it can detain families to deter future migrants and would review every 60 days the custody status of families detained more than three months.

The US started detaining large numbers of migrant mothers and their children in July 2014 as part of what Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson called an “aggressive deterrence strategy” aimed at Central American unauthorized border crossers, among them many asylum seekers.

More than 1,000 mothers and children are locked up in three facilities in Texas and Pennsylvania. The government is constructing space to detain another 2,000 people in families, most in a new facility in Dilley, Texas, which is expected to have capacity to hold 2,400 people in families upon its completion in late May 2015. This facility will be largest immigration detention center in the United States.

“The government should not be searching for new oversight mechanisms for family detention,” Long said. “What’s needed is for the government to simply end family detention.”

Though some asylum-seeking families are released on bond in a matter of weeks, others are either considered ineligible for bond because they have previously been deported or are unable to pay bonds that regularly top $7,500, lawyers working with the families said. Families are provided no information as to when their confinement might end. Human Rights Watch spoke with two women who have been detained with their children since July 2014, over 10 months ago.

Considering families ineligible for release because of a previous deportation does not take into account the validity of their claims for asylum, Human Rights Watch said. Previous Human Rights Watch research found that many of those deported in fast-track procedures had no reasonable opportunity to make an asylum claim.

In late April 2015, US District Court Judge Dolly Gee in California issued a preliminary ruling that the family detention system violates an 18-year-old settlement agreement obligating the US government to favor release of migrant children to their families, or, if not possible, to hold them in the least restrictive environment. She gave the government and lawyers for the detained children until May 24 to negotiate an agreement on compliance. In response, Justice Department lawyers have threatened to release the children while leaving their mothers detained.

International law prohibits detention of asylum seekers except as a measure of last resort and only for reasons such as concerns about danger to the public. Family detention is inconsistent with international standards, particularly the fundamental principle that the “best interest of the child” should control the government’s actions toward children. Instead of detaining families with children, the US should create community-based supervision or other alternatives to detention, where necessary, allowing families out of custody while immigration courts weigh their asylum claims.

“Indefinite detention takes an especially damaging psychological toll on those who had been forced to flee their homes,” Long said. “Children are asking their mothers, ‘When will we be able to leave?’ and these mothers have no reply.”

For details of interviews with detained families, please see below.

Asylum-Seeking Mothers and Children in US Detention

In early May, Human Rights Watch interviewed 25 mothers with children in detention at the South Texas Residential Center in Dilley, Texas and the Karnes County Residential Center in Karnes City, Texas.

Mothers Describe Effects of Detention

Several mothers told Human Rights Watch that their children were exhibiting signs of depression, which they attributed to being detained. Ana (all names have been changed, except where indicated), a 32-year-old woman from Central America who has been detained for eight months in southern Texas with her 14-year-old daughter told Human Rights Watch that she worries constantly that her daughter will hurt herself. “She told me she wanted to hang herself,” Ana said. “‘I’m going to kill myself,’ she tells me. It hurts my heart.”

Compounding these feelings is the fact that many of the women and children suffered serious harm before coming to the United States.

Carolina said her 15-year-old daughter was the victim of severe sexual assault in Honduras when she was 9. “My daughter tells me she can’t bear being locked up anymore,” said Carolina, who has been detained with her daughter for three months. “She told me she wanted to take her own life.”

Beatriz said her 11-year-old son was threatened with forced recruitment by gangs in Honduras. She fled with him to the United States where they have been locked up together since September 2014. “He just sleeps and sleeps,” she said. “He says, ‘Mom, I just want to sleep so that when I wake up we’ll be free.’”

The mothers reported serious distress over their situation. “As a mother, I feel powerless,” said Beatriz. “I don’t want my son to see me so I go into the bathroom to cry and cry. He starts knocking on the door saying, ‘Mom, Mom, are you coming out?’”

“I’m very depressed,” said Carla, who is detained with her 10-year-old son. “We’ve been here for 10 months. I don’t want to see my son suffering anymore.”

After more than eight months in detention, Melida (her real name), who is afraid to go back to Guatemala after gang members murdered her sister-in-law, has been diagnosed in detention with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), adjustment disorder with anxiety, and a major depressive episode. Her 4-year-old daughter, Estrella, has spent nearly 20 percent of her life behind bars and during that time was hospitalized for acute bronchitis and also suffered from acute pharyngitis, ear aches, fevers, diarrhea, and vomiting. More than 22,000 people have signed a petition organized by the American Immigration Lawyers Association calling for their release.

Long-Term Detention

Locking up migrant families while immigration courts consider their asylum claims used to be extremely rare in the United States. However, as the Obama administration chose to expand family detention in 2014, immigration officers implemented a “no-release” policy, saying that it was denying release of families specifically to deter migrants from coming to the US. In February, a US District Court judge in Washington, DC required Immigration and Customs and Enforcement (ICE) to begin individually evaluating asylum-seeking families for release and setting bond where appropriate. ICE is appealing.

Dozens of mothers and children have been released within weeks of their detention if they are found to have a provisionally legitimate asylum claim and can post bond. Many families, however, cannot afford to pay bond, which often starts at $7,500. Lawyers for detained families reported that $15,000 bonds are not uncommon.

However, ICE contends that others with valid applications for humanitarian protection in the United States are not eligible for release or bond because they previously tried to enter the US and had been deported, and that the deportation order is “reinstated” when they re-enter the country.

Twelve of the women Human Rights Watch interviewed are considered ineligible for release because of a previous deportation, their lawyers said. Lawyers working with detained families told Human Rights Watch that these “reinstatement” cases now make up the bulk of families detained for over six months.

The notion that people who were previously inside the US and deported are less worthy of bond is illogical because their claims to protection are no less valid, Human Rights Watch said.

Paola has been in family detention with her 5-year-old son since last September because she had previously been inside the US. She filed an appeal to the reinstatement of her deportation order in May, claiming protection from an abusive husband who beat and raped her, a valid ground for asylum under US law.

“Appeals take a long time,” she said. “But I’m doing it because I can’t go back there.”

Because of ICE’s position that she is not eligible for release on bond, she and her son are to be detained for as long as it takes for the Board of Immigration Appeals to decide her case. If the board turns down the appeal, she may then appeal to federal court, where her case could be pending for years.

Nancy told Human Rights Watch that she was detained with her 8-year-old son for five months before she got a lawyer. This week they won their claim for humanitarian protection after being detained for over nine months.

As Human Rights Watch has previously documented, detained asylum seekers in the US – including detained families – face serious impediments to securing legal representation, without which their claims are at a severe disadvantage.

Failure to Hear Asylum Claims

Of the 12 women Human Rights Watch interviewed whom ICE finds ineligible for release because of a prior deportation, 7 said they had previously been deported from the US without a chance to make a claim for asylum. Human Rights Watch has previously documented that many migrants are summarily deported because Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers fail to ask questions about protection needs or to accurately capture responses to such questions, denying them a chance ever to seek asylum.

“When I crossed before they didn’t ask me if I was afraid, they just deported me,” said Paola, who fled domestic violence. “Then he started abusing me again, and I got my son and left.”

An indigenous Guatemalan woman who suffered severe sexual violence also fell into this category, her attorney told Human Rights Watch. She fled to the US and was rapidly deported twice – in January and April of 2014 – back to Guatemala where she was raped again. She fled for a third time with her 8-year-old son. They were held for six months before winning protection from deportation before an immigration judge.

When the government uses prior border deportations as a justification for denying families release, it punishes the victims – and their children – of abusive border screenings, Human Rights Watch said.