Sold to be Soldiers

The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

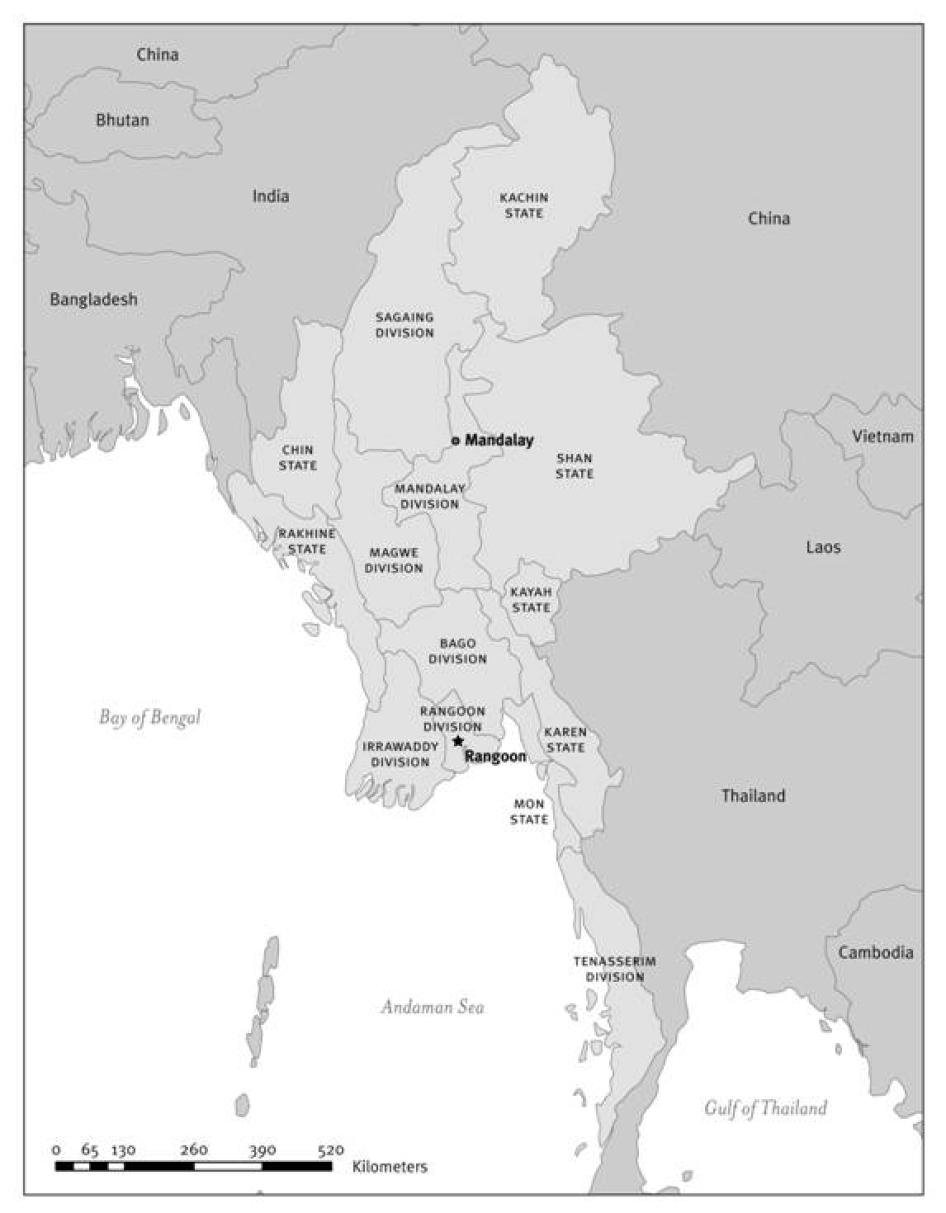

Map of Burma

Terminology and Abbreviations

In this report "child" means any person under the age of 18 years.

In 1989 the English name of the country was changed from Burma to Myanmar by the ruling State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC, now called the State Peace and Development Council, SPDC). English versions of place names were changed to Burmanized versions at the same time: for example, Rangoon became Yangon. The National League for Democracy, which won elections in 1990 that were subsequently rejected by the military government, does not recognize these name changes, and ethnic groups that are not ethnic Burman regard them as part of an effort to Burmanize national culture. Human Rights Watch uses the term "Burma." The adjective "Burmese" is used to describe anything related to the country and language, and "Burman" is used to describe the ethnicity of the country's dominant group.

Tatmadaw translates literally as "armed forces," and is made up of the Army (Tatmadaw Kyi), Air Force (Tatmadaw Lay), and Navy (Tatmadaw Ye). In English we have used the term "Burma army" for the Tatmadaw Kyi.

This report uses the term "non-state armed groups" to refer to all armed groups in Burma that are not under the full and direct control of the regime. These include groups that have surrendered to the government but retain soldiers and arms, groups that have ceasefire agreements with the SPDC (and which vary in the extent of their cooperation with the regime), militias that have effectively been created by the SPDC and act as proxy armies at least partially under SPDC control, and armed groups that have no ceasefire agreements (sometimes referred to as "resistance groups" or "resistance armies").

Unless otherwise specified, "recruitment" is used in this report to encompass all forms of gaining recruits by armed forces or groups, including voluntary, coerced, and forced recruitment.

The value of the kyat, the Burmese currency, is officially pegged at between five and six kyat to one US dollar. However, most exchange occurs on the black market where one US dollar is presently worth over 1,300 kyat to the dollar. Day laborers in Burma commonly earn several hundred kyat per day. A Burma army private's salary is presently 15,000 kyat per month, compared to only 4,500 kyat per month prior to April 2006. This report also makes reference to the Thai baht, which presently exchanges at about 33 to the US dollar.

Some terms, acronyms, and other abbreviations that appear in this report are listed below. Please note that this list is not intended to be exhaustive.

Burma Army

SPDCState Peace and Development Council, ruling military junta

SLORCState Law and Order Restoration Council, former name of the SPDC until 1997

MOCMilitary Operations Command

NCONon-commissioned officers: lance corporals, corporals, and sergeants

Pyitthu Sit"People's Army": militia formed and controlled by the Burma army

Su Saun YayRecruiting center and holding camp for new recruits into the Burma army

Ye Nyunt"Brave Sprouts": a network of camps for boys within Burma army camps, previously used as a way to channel young boys into the Burma army

Other Armed Groups

ABSDFAll-Burma Students' Democratic Front

CPBCommunist Party of Burma

DKBADemocratic Karen Buddhist Army

KDAKachin Defense Army

KIO/KIAKachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army

KNDOKaren National Defense Organization (militia of the KNLA)

KNPLFKarenni Nationalities People's Liberation Front

KNPP/KAKarenni National Progressive Party/Karenni Army

KNU/KNLAKaren National Union/Karen National Liberation Army

NDA-KNew Democratic ArmyKachinland

NMSP/MNLANew Mon State Party/Mon National Liberation Army

RCSSRestoration Council of Shan State (umbrella organization for SSA-S)

SSA-SShanState ArmySouth

SNPLO/SNPLAShan Nationalities People's Liberation Organization/Shan Nationalities People's Liberation Army

UWSAUnited Wa State Army

I. Summary

By the time he was 16, Maung Zaw Oo had been forcibly recruited into Burma's national army not once, but twice. First recruited at age 14 in 2004, he escaped, only to be recruited again the following year. He learned that the corporal who recruited him had received 20,000 kyat,[1] a sack of rice, and a big tin of cooking oil in exchange for the new recruit. "The corporal sold me," he said. The battalion that "bought" him then delivered him to a recruitment center for an even higher sum-50,000 kyat.

When his aunt learned that Maung Zaw Oo had been recruited a second time, she and his grandmother made a long trip to his battalion camp to try to gain his release. The captain of the battalion company offered to let Maung Zaw Oo go, but only in exchange for five new recruits. Maung Zaw Oo said, "I told my aunt, 'Don't do this. I don't want five others to face this, it's very bad here. I'll just stay and face it myself.'"

By age 16 Maung Zaw Oo seemed resigned to his fate. When his unit went on patrol, he would volunteer for the most dangerous positions, walking either "point" at the front of the column, or last at the back. He said, "In the army, my life was worthless, so I chose it that way."[2]

In Burma, boys like Maung Zaw Oo have become a commodity, literally bought and sold by military recruiters who are desperate to meet recruitment quotas imposed by their superiors. Declining morale in the army, high desertion rates, and a shortage of willing volunteers have created such high demand for new recruits that many boys, some as young as ten, are targeted in massive recruitment drives and forced to become soldiers in Burma's national army, the Tatmadaw Kyi.

For over a decade, consistent reports from the United Nations (UN) and independent sources have documented widespread recruitment and use of children as soldiers in Burma.[3] At the beginning of 2004 the ruling military junta, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), responded to international criticism of its child recruitment practices by establishing a high-level Committee for Prevention of Military Recruitment of Underage Children. However, close scrutiny reveals that the Committee has taken no significant action to redress the issue. Instead, the Committee's primary role appears to be to denounce accounts of child recruitment as false.

Child soldiers are also present in the majority of Burma's 30 or more non-state armed groups, though in far smaller numbers. Some of these groups have taken effective measures to reduce the number of child soldiers among their forces, but other groups continue to recruit children and use them in their ranks.

The UN secretary-general has identified Burma's armed forces as a consistent violator of international standards prohibiting the recruitment and use of child soldiers, listing the Tatmadaw Kyi in four consecutive reports since 2003. Several armed opposition groups have also been listed for recruiting and using child soldiers. The UN Security Council has stated repeatedly that it will consider targeted sanctions, including embargoes of arms and other military assistance, against parties on the secretary-general's list that refuse to end their use of children as soldiers, but so far has taken no action in the case of Burma. Given the abysmal record of the SPDC and some non-state armed groups in this regard, such action is clearly warranted.

The Government of Burma's Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw

The Burmese government claims that its national armed forces, the Tatmadaw, is an all-volunteer force, and that the minimum age for recruitment is 18.[4] However, Tatmadaw soldiers, officers, and other witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch consistently testified that the majority of new recruits are conscripts, and that a large proportion of them are children. Since the early 1990s the number of voluntary recruits has been far from sufficient to staff the rapidly expanding Tatmadaw. At the same time the Tatmadaw has been plagued by high rates of desertion. To offset high rates of attrition and to staff new regiments, specialized recruitment units have been established throughout the country, and regular army battalions have also been ordered to fill recruitment quotas. In mid-2006 a senior general called for the recruitment of 7,000 new soldiers a month, four times the actual recruitment rate of a year earlier. Battalion commanders failing to meet their recruiting quotas are subject to a range of disciplinary action including the loss of their command posting.

The unrelenting pressure to meet recruitment quotas has placed boys at constant risk of forced or coerced recruitment. Battalions and recruiting centers offer cash and other inducements[5] to their own soldiers to bring in recruits, but are also willing to "buy" recruits from civilian brokers and the police. In 2005 the going rate for new recruits ranged from 25,000 to 50,000 kayt-representing one-and-a-half to over three times the monthly salary of an army private. Would-be recruiters watch train stations, bus stations, markets, and other public places, looking for "targets"-the easiest being young adolescent boys on their own. The boys are then induced with promises of money, clothing, status, a job and a free education, or threatened with arrest for loitering or not being in possession of an identity card and offered military service as the alternative, or they may be otherwise intimidated, coerced, or if necessary beaten into "volunteering" for the army. Some boys interviewed by Human Rights Watch told how they and others had been detained in cells, handcuffed, beaten, bought and sold from one recruiter or battalion to another, and eventually taken to the recruitment centers. As this report was going to press in October 2007, Human Rights Watch continued to receive eyewitness accounts of army units recruiting children and transporting them to training centers.

The government's deployment of the army in September 2007 to attack Buddhist monks and other peaceful protesters may increase the vulnerability of children to recruitment even further. Even before the crackdown, young men were often reluctant to join the military, because of its low pay, difficult conditions, and the poor treatment of enlisted soldiers. The use of the army in attacks, killings, and detentions of protesters may further discourage voluntary enlistment, and prompt recruiters to seek out even greater numbers of child recruits.

At the time of enlistment, all recruits are required to provide documentary evidence that they are over 18 years old. According to the testimonies collected by Human Rights Watch, such proof is rarely requested and recruitment officers appear to consistently register underage recruits as being 18, even when the child states otherwise. Any reluctance on the part of the recruitment officers to register boys who are particularly young is usually remedied by a bribe, so that the procurer of the recruit can receive his incentive payout. One boy recruited at age 11 told Human Rights Watch that he failed his recruitment medical because he was only four feet three inches (1.3 meters) tall and weighed only 70 pounds (31 kilograms), but that his recruiter bribed the medical officer to ensure his recruitment regardless. Some soldiers interviewed noted that as the demand for new recruits grows, adherence to minimum guidelines on physical, medical, educational, and age standards has become increasingly lax.

Child recruits are held as virtual prisoners until sent for 18 weeks of basic military training, where they are forced to do heavy physical work and are punished if they fail in their training exercises. Recruits who attempt escape, including children, are punished, often severely. Human Rights Watch has received consistent reports of soldiers who desert from training being beaten with sticks by as many as 200 or more trainees; injuries sustained from such punishment sometimes leave them disabled for weeks.

After training, child soldiers are deployed to battalions, where they are subject to physical abuse by officers and are sometimes forced to participate in human rights abuses such as burning villages and using civilians for forced labor. Some battalions keep their younger children away from combat, but in others, child soldiers may be sent into combat zones within a few days to a month of their arrival; most of those interviewed for this report had seen combat and violent death. Leave is rarely granted, and discharge is usually conditioned on bringing in several new recruits.

Those who desert the army are often caught when they return home and imprisoned or re-recruited. Several of those interviewed had escaped only to be recaptured and forced to join the army a second time while still a child. Than Myint Oo, for example, was first recruited at 14, escaped the army, but was captured and sentenced to six months' imprisonment for desertion at age 15. He escaped from prison, was captured and re-recruited to the army, and eventually deserted again and reached Thailand. Now 19, he no longer dares return home.

All of the former soldiers interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported the presence of children in their training companies. Of the 20 interviewed, all but one estimated that at least 30 percent of their fellow trainees were under age 18. The prevalence of child soldiers in army battalions varies significantly. In some infantry battalions child soldiers comprise less than 5 percent of total staffing, while former child soldiers reported that in some newly created battalions, up to 50 to 60 percent of all privates were below age 18. Given these variations and the difficulty of estimating overall staffing levels within the Tatmadaw, this report makes no attempt to estimate the total number of children in Burma's army.

Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment

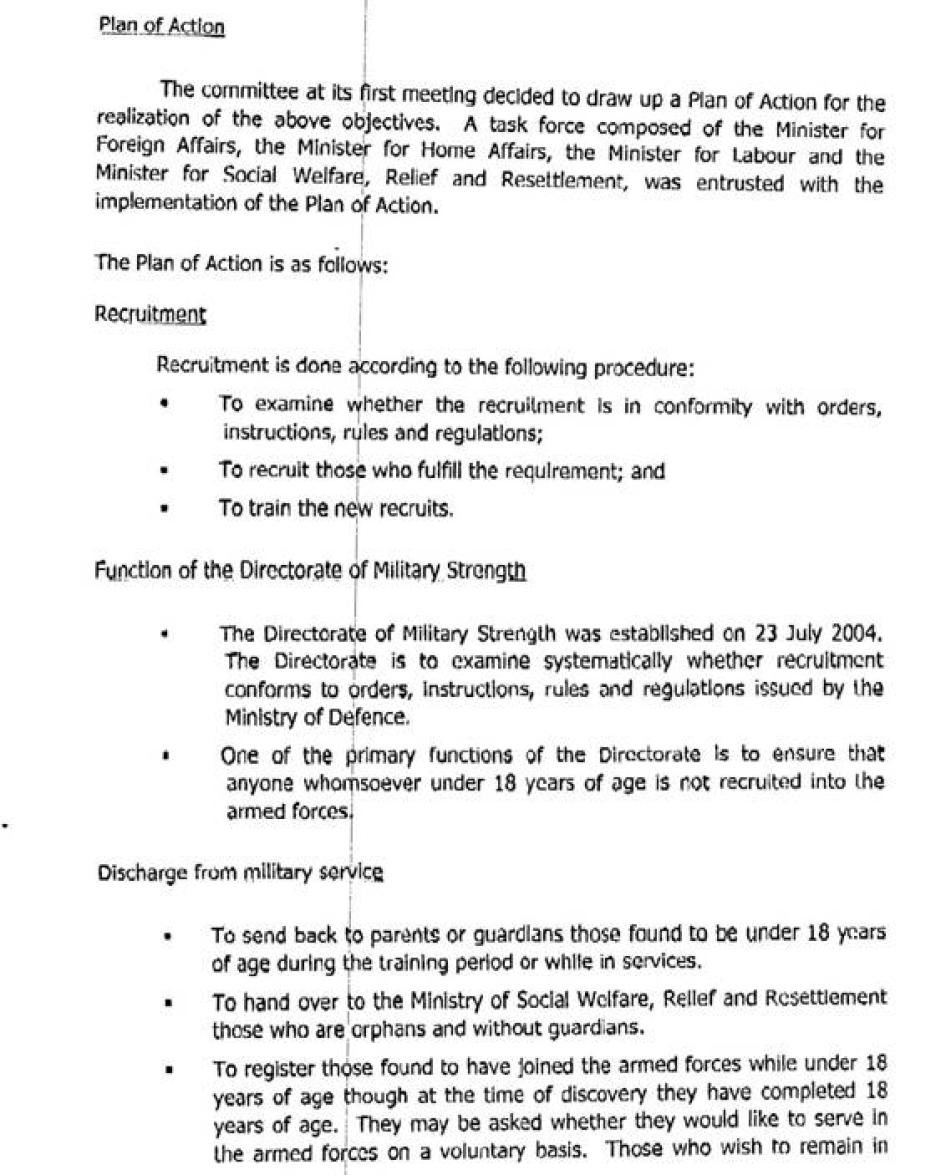

The SPDC has consistently denied the presence of any child soldiers in the Tatmadaw, and has failed to take substantive action to end the army's institutionalized and pervasive recruitment of children. The Committee for Prevention of Military Recruitment of Underage Children has a Plan of Action to address the issue, but in practice this body has done little to implement the steps outlined therein.

The Committee's Plan of Action calls for public awareness efforts regarding child recruitment, but Human Rights Watch found very little evidence of government-led awareness raising initiatives either within the armed forces, or among the public. None of the current or former soldiers interviewed by Human Rights Watch, including battalion commanders and a clerk in a military operations command headquarters, were aware of any military directives concerning child recruitment. Human Rights Watch found no evidence of public education efforts through various media, as outlined in the Plan of Action. To the contrary, the principal public awareness raising function of the Committee (in fact, its principal effort overall) seems to be to disavow any child recruitment by the Tatmadaw. The state-run media has asserted that such reports are "slanderous accusations," and as recently as September 2007 declared that the government was working with UN agencies "to reveal that accusation concerning child soldiers is totally untrue."[6]

According to figures released by the SPDC, only 122 child soldiers have been released from the army since 2004-an annual rate that is significantly lower than the number of child soldiers reportedly released in the years immediately preceding the Committee's creation. Some parents who have lodged protests with international organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) have succeeded in having their sons released from the army after these organizations petitioned the government. In other cases, however, the government has refused to accept documentation of claims, or has offered parents money or goods to dissuade them from making formal reports. Human Rights Watch also received numerous reports that military officials had demanded that parents or guardians pay them bribes to secure the release of their children. At the same time, the army continues to arrest child soldiers who desert, to prosecute them, and incarcerate them in prison facilities for adults.

The SPDC claims to have taken disciplinary action against child recruiters in at least 30 cases since 2002. However, it has not made public any information regarding the sanctions imposed, and its own reports indicate that no child recruiters were disciplined in 2005 or 2006. Impunity for child recruiters is the norm. Testimony collected for this report demonstrates that not only do Tatmadaw officials tolerate the recruitment of children, but many are complicit by falsifying age records or paying out money and goods for recruits who are clearly underage.

The SPDC has taken no positive action over the past five years that is likely to seriously affect the continued recruitment and use of child soldiers in their forces. To the contrary, unsustainable recruitment quotas, and systematic disregard for national and international laws prohibiting child recruitment suggest that the practice is only likely to continue. Any promises of future action, should be taken seriously only if followed by effective action with demonstrable results, and independent verification through unrestricted monitoring.

Non-state Armed Groups

This report does not attempt to document the use of child soldiers by all non-state armed groups in Burma, but rather discusses 12 groups as examples, including most of the larger groups. Most of Burma's non-state armed groups have at least some child soldiers in their ranks, but they differ greatly in how these children are recruited and treated, and in their willingness and efforts to stop using child soldiers. These groups are much smaller in troop strength than the Tatmadaw, and as a whole have far fewer child soldiers than the Tatmadaw.

Many child recruits volunteer to serve in these groups, either because their families cannot support them or because they wish to participate in the armed struggle or to defend their families and villages against the Burma army's human rights abuses. Some armed groups impose recruit quotas requiring villages or households to supply a recruit. In such cases a family often sends a child under 18 so that it can retain the older, more productive family members for the household, or because they have no children over 18.

Many non-state groups have only recently begun seeing child recruitment as an issue. Human Rights Watch found that while some groups, like the Karenni Army and the Karen National Liberation Army, have taken steps to address child recruitment, other groups persist in the practice, including the United Wa State Army, the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army, and the Karenni Nationalities People's Liberation Front. Many are wary of engaging the international community on this issue: for example, the Shan State ArmySouth, which appears to have taken some measures on its own but is reluctant to allow outside monitoring, and the Kachin Independence Army, which considers accepting children into non-combat roles in the army as a form of foster care for vulnerable children, and prefers to deal with the issue without outside involvement.

Both the Karenni Army and the Karen National Liberation Army have taken measures to try to bring their practices into line with international standards, including the recent signing by both groups of Deeds of Commitment promising to end child recruitment, demobilize children in their forces, and allow outsiders to independently monitor their compliance. Although previous Human Rights Watch research found children present in the Karenni Army, our current investigation found no evidence of recruitment or use of child soldiers by the group.

Based on the evidence gathered for this report, Human Rights Watch recommends that the Karenni Army (KA) be removed from the secretary-general's list of parties to armed conflict in violation of international norms prohibiting the recruitment and use of child soldiers, but that the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army and the Karenni Nationalities People's Liberation Front (KNPLF) should be among groups considered for addition to the list.

The Local and International Response

The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the International Labour Organization, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and some nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), have attempted to address issues related to child soldiers in a variety of ways in recent years. These efforts include case work aimed at securing the release of specific children who have been recruited, and broader preventive initiatives to keep children in school, improve birth registration procedures, raise public awareness, and engage the government, the military, and non-state armed groups on child rights issues.

In some cases, international and local organizations have been able to successfully intervene to have child soldiers released, although their efforts in others are obstructed. Broader initiatives in Burma have met with limited success because they address the issue indirectly. Efforts to register births and keep children in school are undermined by poverty, economic mismanagement, and governmental corruption.

In neighboring countries, local and international NGOs have attempted to improve protection and to reintegrate escaped Tatmadaw child soldiers, who are extremely vulnerable. Although these initiatives have helped some children, they are severely hindered by governmental restrictions imposed on refugees and the organizations that help them. Tatmadaw deserters dare not return to Burma, may be vulnerable within refugee camps, but are in danger of refoulement if they are living outside of refugee camps. In many cases resettlement to a third country is the most viable solution for former child soldiers, but the Thai government, as host to the largest refugee population from Burma, is now blocking this option for most of them as well.

Other initiatives include teaching child rights to refugees and displaced villagers; establishing accelerated schools for adolescent children who have never had any education, in order to decrease their vulnerability to recruitment; and training officers in non-state armed groups about child rights. These initiatives have been successful in reducing child recruitment in some areas, but they tend to be under-resourced. A greater political will to engage non-state armed groups on this issue, combined with more resources, would probably yield positive results.

II. Recommendations

To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC)

- Immediately end all recruitment of children under the age of 18, and demobilize children under the age of 18 from the armed forces.

- Offer the option of an honorable discharge to any soldier now over the age of 18 but who was recruited as a child.

- Ensure that all recruits to the military are at least 18 years of age. To this end, enforce the requirement (already stated in recruitment brochures) that all recruits to the military must provide documentary proof that they are 18 years of age or over, and enact a system for monitoring that such documents have been received and verified.

- Implement comprehensive birth registration and ensure that all children have proof of age.

- Develop and impose effective and appropriate sanctions against individuals found to be recruiting children under 18 into the armed forces, and publicize information about these sanctions within the military and publicly. Sanctions including potential conviction and imprisonment must apply to anyone who recruits children for the military, including military recruiters, police, members of groups such as the fire brigades, and civilians in general.

- Eliminate all incentives, including monetary compensation, promotions, or military discharge for soldiers who recruit children.

- Seek international cooperation with relevant agencies in order to verify recruitment practices. As part of this, allow monitoring of recruitment and training centers by independent outside bodies.

- Establish a system for recruits, their families, or concerned parties to inquire whether a particular child has been recruited, and if so to petition for that child's release, without fear of retaliation against the child or the petitioner. This could be set up in conjunction with international organizations or as an independent office, monitored by outside organizations. Publicize this system nationwide.

- Ensure that children and soldiers recruited as children who run away from the armed forces are not treated as deserters or subject to punishment. Immediately release all children or those recruited as children who are detained or imprisoned for desertion.

- Create a mechanism to assist former child soldiers, including children from the Ye Nyunt, to reunite with their families without fear of state punishment or retaliation.

- Cooperate with international nongovernmental organizations, UNICEF, and UNHCR to reunite former child soldiers with their families, and facilitate their rehabilitation and social reintegration, including appropriate educational and vocational opportunities.

- Sign and ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflicts, and consistent with existing national law, deposit a binding declaration establishing a minimum age of voluntary recruitment of at least 18.

- Ratify the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (International Labour Organization Convention No. 182), which defines the forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict as one of the worst forms of child labor.

- Ratify the Rome Statute for the International Criminal Court, which includes the recruitment or use of children under the age of 15 in its definition of war crimes.

- Conduct public education campaigns through the media and elsewhere to inform children and parents of the rights of children, including their right not to be recruited into armed forces or groups, in accordance with the Plan of Action of the Committee for Prevention of Military Recruitment of Underage Children.

- Increase information sharing with international organizations regarding the work of the Committee for Prevention of Military Recruitment of Underage Children, and work with UNICEF to amend the Committee's Plan of Action to reflect international standards, UN Security Council resolutions 1539 and 1612, and the Paris Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups.

- In cooperation with the International Committee of the Red Cross, UNICEF, and nongovernmental organizations, conduct trainings in international humanitarian law and the rights of children for all soldiers, including officers and recruiters.

- Remove restrictions on humanitarian access by international organizations, and cooperate with these organizations in ending all recruitment and use of child soldiers.

- Allow Burmese civil society organizations to report and act on cases of child recruitment without threat of reprisals.

- Ensure that all children have access to free and compulsory quality primary education, and work towards the progressive introduction of free secondary education. Waive school fees and other associated costs of education, including costs for books and uniforms, or develop fee assistance programs for children whose families are unable to afford them.

- Ensure that any educational programs for children run by or in conjunction with the armed forces meet internationally accepted standards of education. Ensure that participation in such programs is voluntary, with the informed consent of the child's parents or guardian, and that students are not members of the armed forces or used for any military activities.

- Ensure that all children enrolled in educational programs run by the armed forces have regular contact, including visits, with their families.

- Ensure that orphans and abandoned children have access to mainstream (non-military) schools, and receive adequate care.

- Ensure that educational opportunities offered to orphans, displaced, or other children are not conditioned on military service either during or after completion.

- Where the government has relations with non-state armed groups (such as "ceasefire groups"), press these groups to comply with international standards relating to the recruitment and use of children as soldiers, and provide or refer them to outside technical support when necessary to help them do so.

As short-term interim measures until all children have been demobilized from the military:

- Ensure that children in the armed forces receive regular leave and are allowed to communicate regularly with their families.

- Immediately end all physical and psychological abuse of child soldiers.

To AllNon-state Armed Groups

- Immediately end all recruitment of children under the age of 18 and demobilize children under age 18 from armed groups.

- Offer the option of an honorable discharge to any soldier now over the age of 18 but who was recruited as a child.

- Formalize a commitment to end all child recruitment, demobilize children in the armed forces, and allow outside monitoring, for example, by signing a Deed of Commitment like those already signed by the Karenni Army and Karen National Liberation Army and reproduced in this report.

- Develop and enforce clear policies, if they do not already exist, to prohibit the recruitment of children under the age of 18. Ensure that such policies are widely communicated to members of the armed forces and to civilians within the group's area of influence.

- Develop reliable systems to verify the age of individuals recruited into the armed group, and ensure that all such recruits are at least 18 years old.

- Develop and impose systematic sanctions against individuals found to be recruiting children under 18.

- Ensure that children under age 18 who desert SPDC forces or are captured are not recruited as soldiers into opposition forces.

- Seek international cooperation with relevant agencies in order to independently verify recruitment practices.

- Conduct public education campaigns to inform children and parents within the group's area of influence of the rights of children, including their right not to be recruited into armed forces or groups.

- In cooperation with the International Committee of the Red Cross, UNICEF, and nongovernmental organizations, conduct trainings in international humanitarian law and the rights of children for all soldiers, including officers and recruiters.

- Wherever possible, establish educational programs and vocational training, and encourage children and their families to utilize such opportunities.

- Ensure that educational opportunities offered to orphans, displaced, or other children are not conditioned on military service either during or after completion.

To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China

- Notify UNHCR and relevant nongovernmental organizations when children who have deserted SPDC forces or individuals who may have been child soldiers are taken into custody, to allow access and a determination of their status.

- Ensure that such children and individuals receive special protection and that they are not refouled. To this end, rescind and repudiate any refoulement agreement for former child soldiers.

To the Government of Thailand

- Rescind the agreement of the Joint Border Cooperation Committee which specifies that deserters from SPDC forces found on Thai soil will be handed over to Burmese authorities.

- Allow UNHCR, UNICEF, the ICRC, and nongovernmental organizations to establish protection and support mechanisms for former child soldiers both in and outside of existing refugee camps.

- Allow UNHCR, UNICEF, the ICRC, and nongovernmental organizations to conduct workshops and other initiatives on child rights to prevent recruitment of children into armed groups from refugee camps or other locations in Thailand.

To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- In refugee status determinations, take into account the special circumstances of children recruited before the age of 18 (even in cases where the applicant is now over the age of 18), including the possibility of extrajudicial execution if they are returned to Burma.

- Fully apply the "UNHCR Guidelines on Policies and Procedures in dealing with Unaccompanied Children Seeking Asylum" and the "UNHCR Guidelines on Protection and Care of Refugee Children," especially those sections relating to procedures and criteria for refugee status determination for unaccompanied minors.

- Amend the "Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status" to provide guidance on considering the claims of unaccompanied children, and in particular former child soldiers, that is consistent with other UNHCR policies and guidelines and that fully takes into account the fact that the recruitment of children under the age of 18 is internationally considered to be a human rights violation.

- Investigate cases of deserters, including child deserters, being detained for possible deportation by authorities in Thailand and in Burma's other neighboring countries.

- Provide technical support and material assistance for initiatives aimed at preventing child recruitment and reintegrating former child soldiers in refugee camps and other locations in Burma's neighboring countries.

- Provide technical and material assistance to civil society and non-state armed groups charged with the care and protection of child deserters from any armed force who reach a neighboring country.

To UNICEF

- Continue to advocate with the SPDC for an immediate end to all recruitment of child soldiers and demobilization of those already in the armed forces.

- Work with the SPDC to establish mechanisms to demobilize children from the armed forces, and establish programs to facilitate the rehabilitation and social reintegration of former child soldiers, including appropriate educational and vocational opportunities.

- Help to reunite former child soldiers with their families.

- Reestablish contact with non-state armed groups, including those still in armed conflict with the Tatmadaw, and resume discussions and initiatives with these groups to address the issue of child soldiers.

- Provide technical support and material assistance for initiatives aimed at preventing child recruitment and reintegrating former child soldiers in non-state armed groups as well as the Tatmadaw; this should include support for projects such as "accelerated schools" in refugee camps and related projects in refugee camps, areas controlled by non-state groups, and areas controlled by the state.

- Provide technical and material assistance to civil society and non-state armed groups charged with the care and protection of child deserters from any armed force. Assistance should not be biased in favor of actors linked to or at peace with the state, as this is a violation of humanitarian neutrality; therefore assistance for disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration programs offered to the SPDC should also be offered in appropriate proportion to non-state groups who are expected to abide by the same standards.

- In line with the above, offer technical assistance to improve birth registration in areas controlled by non-state groups similar to that which is being offered to the SPDC in areas that it controls.

To the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict

- Continue direct contact with the SPDC and non-state groups and actively monitor whether their commitments are implemented effectively.

- Engage with civil society actors inside and outside Burma, including those outside the UN system, who can help monitor the situation and who can provide advice on ways forward.

- Immediately establish contact with the non-state armed groups on the secretary-general's list of groups using child soldiers, both formally and informally, regarding their compliance with international standards.

- Remove the Karenni Army from the list of armed groups using child soldiers to be included in the secretary-general's next report to the Security Council on children and armed conflict, and consider adding groups for which strong evidence exists that they are significant abusers of child soldiers, including the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA) and the Karenni Nationalities People's Liberation Front (KNPLF).

To Member States of the United Nations

- In accordance with Security Council resolution 1379 on children and armed conflict (November 20, 2001), paragraph 9, use all legal, political, diplomatic, financial, and material measures to ensure respect for international norms for the protection of children by parties to armed conflict. In particular, states should unequivocally condemn the recruitment and use of children as soldiers by the SPDC and other armed groups, and withhold any financial, political, or military support to these forces or groups until they end all child recruitment and release all children in their ranks.

- Use diplomatic and other appropriate means to press the governments of Burma's neighboring countries to protect and not refoule escaped and prospective child soldiers, and to allow civil society initiatives to assist and protect these children.

To the UN Security Council

- In accordance with Security Council resolutions 1539 (paragraph 5) and 1612 (paragraph 9) on children and armed conflict, adopt targeted measures to address the failure of the SPDC to end the recruitment and use of child soldiers. Consider measures recommended by the secretary-general, including the imposition of travel restrictions on leaders, a ban on the supply of small arms, a ban on military assistance, and restriction on the flow of financial resources.

To the International Labour Organization

- From the Rangoon office, continue accepting and pursuing cases of the reported recruitment of child soldiers through the ILO mechanism for reports of forced labor. Where the government refuses to act on a case despite documentary evidence provided by the ILO, press further for action on these cases and raise them with the higher levels of the ILO itself.

To the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar

- Continue to research and report on the recruitment and use of child soldiers by the Burma army and other armed groups, and include relevant findings on this subject whenever presenting information to the General Assembly or the Human Rights Council.

III. Methodology

This report is based on research conducted by Human Rights Watch in border areas of Burma, Thailand and China, between July and September 2007. During the course of the investigation, Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews with current and former soldiers, including 20 current or former Tatmadaw soldiers and officers and more than 30 current or former soldiers and officers with armed opposition groups. Interviews were also conducted with more than 12 senior officials of various armed opposition groups or their political parties.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed health workers and other civilians living and/or working in regions of Burma where the Tatmadaw and non-state armed groups are active; representatives of several humanitarian organizations based in Thailand and Burma, including nongovernmental organizations; the United Nations resident coordinator for Burma and other representatives of UN bodies in Burma and Thailand including UNICEF, UNHCR, and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); local human rights researchers in the Burma-Thailand border area; independent Burma analysts; and others. SPDC representatives were asked for information by letter and responded in writing, but declined to provide any of the information requested (see Appendix C).

Of the 20 active duty and former Tatmadaw soldiers and officers interviewed, one had served in the navy (recruited at 18) and the remainder were serving or had served in the army. Army personnel included three command-level officers holding the rank of captain or major, one lieutenant, and five non-commissioned officers (four sergeants and one corporal), and ten privates. In total, 12 of the 19 in the army were recruited as children. All of them remained as privates during their entire time in the army except for the longest-serving, who eventually made corporal, and a second who was recruited into the DefenseServicesAcademy at age 16.

Of the 13 former Tatmadaw soldiers who were recruited as children, all but two were recruited between 2000 and 2006. At least three of them escaped the army while still children, only to be forcibly recruited a second time. Their length of army service ranged from several months to 13 years.

Soldiers interviewed for this report originated from several states and divisions in Burma, and served in army units in Rakhine, Kachin, Shan, Karen, and Mon states, and Pegu, Rangoon, Tenasserim and Sagaing divisions. They underwent training at various military training camps located throughout the country. Most were then posted to infantry and light infantry battalions. Most escaped the army in 2005 and 2006.

The non-state soldiers and officers interviewed are presently serving or have previously served in the Kachin Independence Army, Karen National Liberation Army, Democratic Karen Buddhist Army, Karenni Army, Shan State ArmySouth, KNU-KNLA Peace Council, and the All-Burma Students' Democratic Front. Only two, from the KNU-KNLA Peace Council, were judged by Human Rights Watch to be child soldiers. To supplement this information, interviews were conducted with health workers, community leaders, civilian witnesses, and humanitarian workers active in the areas where non-state armed groups operate.

Most interviews lasted between one-and-a-half and three hours, with the assistance of independent translators selected by Human Rights Watch as required. Interviews were conducted in private, and interviewees were assured that their names would not be published. Each interviewee was asked detailed questions regarding their recruitment, training, and deployment, the ages and treatment of fellow soldiers with whom they served, and whatever they knew about policies within the groups they served.

The names of all present and former soldiers quoted in this report have been changed. In some cases officials and spokespersons of armed opposition groups gave permission for their names to be used, and these have been included. Some opposition group and nongovernmental and intergovernmental agency representatives requested that they or their organizations not be identified, in order to protect themselves from reprisals by government and military authorities, so identifying information has been omitted accordingly.

IV. Background

Burma is the largest country in mainland Southeast Asia, lying strategically between India, China, Bangladesh, Laos, and Thailand. Over the past three millennia various peoples have migrated into what is now Burma from other parts of East Asia, creating a diverse ethnic mix. The present population is generally estimated to be approximately 50 million, though no reliable census data exists; this is made up of Burmans and approximately 15 other major ethnicities, each of which has subgroups. While the military junta presently ruling Burma claims that 67 to 70 percent of the population is ethnically Burman, this is based on skewed data from an old census in which anyone with a Burmese-language name was listed as Burman. By contrast, non-Burman groups set the figure at 70 percent non-Burman and 30 percent Burman. Other estimates range between these two extremes.[7]

Enmities between certain ethnic groups go back hundreds of years, dating from the times that Burman, Mon-Khmer, and Rakhine kingdoms fought each other, while more peaceable peoples were driven into remote areas. The end result was a central plain dominated by Burmans, encircled by various non-Burman populations who form the majority in the outlying and more rugged regions of the country. Most of the ethnic groups are concentrated within a particular region, which has been a central factor in the formation of ethnicity-based armed groups, each based in their home region and drawing support from the local population.

In the 19th century the British took over what is now Burma and formed it into a single entity under the Indian colonial administration. The Japanese occupied Burma during the Second World War but were driven out by British Empire forces as the war drew to an end. However, by that time Burmese nationalism was already too strong for the British, who negotiated with Burmese General Aung San and granted Burma independence in 1948. Although Aung San had negotiated agreements with some non-Burman groups, he was assassinated in 1947 and none of those agreements was ever honored. Instead, the new Burmese government refused any autonomy to non-Burman ethnic regions. Facing a communist insurgency from the beginning, the government soon found itself also facing an increasing number of armed ethnicity-based resistance groups all over the country, most of which were seeking their own independence.

In 1962 the head of the Burma army, General Ne Win, overthrew the civilian government and established the military rule that has continued to this day. He progressively stepped up the civil war against the dozen or more resistance and insurgent groups he was already facing, and his xenophobic economic policies and repression of the civilian population gradually dragged the country down into poverty. In 1988 civilian anger exploded into mass nationwide peaceful demonstrations led by students and Buddhist monks. The army responded by attacking the crowds with machine-gun fire and bayonets, and as many as 3,000 are estimated to have been killed. The government reformed itself into a military junta, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), and imposed martial law, curfews, and other restrictions, while thousands of dissidents fled to the large territories controlled by ethnic and communist armed groups, there to form their own additional political and armed groups. In 1990 the SLORC held an election in most parts of the country, but when the opposition National League for Democracy won a landslide victory the junta refused to concede power.

Since that time restrictions on human rights and freedoms have intensified throughout the country, and human rights abuses have grown much worse especially in the non-Burman regions. In ceasefire areas, human rights violations have decreased as a result of cessation of open warfare and the government's emphasis on infrastructure and aid projects, and its business interests. Nevertheless, human rights violations such as forced labor, land confiscations, and militarization by the Burmese army continue in a culture of impunity.

In 1997 the SLORC changed its name to the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), but this was not accompanied by any political liberalization. The state military or Tatmadaw, which had fewer than 200,000 men before 1988, announced a program to expand its strength to 500,000, and began much more intensive attacks throughout the country. This was facilitated by a mutiny in 1989 that caused the dissolution of the Communist Party of Burma, the country's largest opposition armed group. The SLORC was quick to approach the United Wa State Army, which had been formed from the remnants of the communist soldiers, and negotiated a ceasefire with it that still stands. Through the 1990s non-state armed groups found that they could no longer withstand the intensified attacks of the greatly expanded Burma army, and one by one the majority of them also entered into various forms of armistice agreements. These agreements do not address any political aspirations or human rights concerns of the non-state groups, but allow them to retain arms and partial control over small parts of their former areas. They are given freedom to conduct businesses including resource extraction and transportation services, and many of these groups have now become primarily money-making armies using their arms to protect their business interests and extort resources from local populations.

Some groups have continued to fight. Since 1995 the Burma army has been successful in capturing most of the former territories of these armies and in exploiting splits and factionalism within them, to the point where none of the remaining groups without ceasefires any longer controls significant territories and they primarily operate in small guerrilla units. These units harass local Burma army units but seldom leave their home areas. The main groups that are still fighting the Tatmadaw include the Shan State Army South (SSA-S), the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), and the Karenni Army (KA), none of which has more than 5,000 or 6,000 troops. Most of these groups gave up the objective of independence after 1988 and have instead been pursuing the objective of a democratic federal union. At present they are not a military threat to the SPDC's hold on power, but they continue to retain de facto control over some areas and defend some areas of refuge for displaced villagers.

The Burma army's expansion is ongoing, and Burma army camps are in abundance throughout Burma, even in areas far from any armed conflict. Where there is no fighting, the troops work to restrict the activities and movements of the civilian population and make demands on them for forced labor and money. In areas where there is still armed conflict, the army attempts to undermine the opposition by destroying civilian villages and food supplies and retaliating against the local civilian population every time fighting occurs. Civilians in these areas are routinely forced to work as porters, guides, and unarmed sentries for Burma army units on military operations, and even walk in front of troops in areas suspected of landmine contamination (atrocity demining). Many of them are children, and many are wounded or killed in the process. This direct use of civilian children for military functions has been documented widely by Human Rights Watch and other organizations, and is not covered in detail in this report.

In September 2007 the regime deployed the army to violently repress nationwide peaceful demonstrations led by Buddhist monks. The monks began peaceful processions to protest the hardships brought on the population by a 400 percent fuel price hike imposed by the SPDC on August 15. After violent incidents in which monks were teargassed and some were beaten, the protests grew and processions of monks were joined by thousands of civilians in sites across the country. From September 26 to 28, the Army responded by violently attacking the processions, arresting civilian political activists, and raiding and sacking monasteries at night, during which monks were beaten and many were detained and taken away by soldiers; many have not yet been released, though exact numbers are still unknown.An official statement by the SPDC admitted that almost 3,000 people had been detained.[8] Official statements have placed the number of peaceful protesters killed at around 10, but other estimates are much higher and many people have disappeared.As a result, anti-military sentiment among the civilian population and the monkhood appears to be at an all-time high. It is probable, though unconfirmed, that child soldiers were among those forced to attack and violently abuse the monks, a spiritual crime almost without equal in Buddhism. In addition, the present popular antipathy toward the armed forces is likely to make it even more difficult to obtain voluntary recruits, so recruitment units may resort to even more forced recruitment of children in order to meet their quotas.

This report updates the information presented in the comprehensive report "'My Gun Was As Tall As Me': Child Soldiers in Burma," published by Human Rights Watch in 2002.[9] The next chapter examines in detail the recruitment and treatment of child soldiers in the Tatmadaw, followed by an examination of the SPDC's claims and initiatives regarding child soldiers since 2002. Later in the report, several of the non-state armed groups are also examined in detail regarding the same issues. Finally, the report discusses initiatives since 2002 by local and international actors to respond to the recruitment and deployment of child soldiers in Burma, and looks at applicable domestic and international legal standards.

V. The Tatmadaw: The State Military

The Tatmadaw, Burma's armed forces, is composed of three branches, the Tatmadaw Kyi (Army), the Tatmadaw Lei (Air Force), and Tatmadaw Yei (Navy). The government also relies upon a complex array of paramilitary organizations and militias spread throughout the country to enforce its rule. This report focuses on the army, which is by far the largest branch of the Tatmadaw and which recruits and deploys child soldiers in the greatest numbers.

The Tatmadaw's Staffing Crisis

Following the suppression of nationwide democracy demonstrations in 1988, the ruling military council initiated a dramatic effort to modernize and expand the armed forces.Over the subsequent 19 years, billions of dollars in arms and military goods were procured-defense expenditures in some years came to comprise as much as 50 percent of central government expenditures.[10]

To tighten its control over the populace, the Tatmadaw also instituted a dramatic expansion of military regiments and bases throughout the country. Infantry and light infantry battalions tripled in number from 168 to 504.[11] The navy and air force also expanded dramatically, although they continued to comprise a much smaller part of the Tatmadaw.

This dramatic expansion of operational units necessitated a dramatic expansion in armed forces personnel. In 1988 the Tatmadaw comprised fewer than 200,000 soldiers.[12] In the 1990s Burma army doctrine prescribed infantry battalion staffing of 750 personnel; this number was subsequently increased to 826. The army's 504 infantry battalions therefore require over 410,000 soldiers to be fully staffed. The army's numerous auxiliary units such as artillery, armored, signals, engineering, and supply battalions require many tens of thousands more personnel. Statements by senior military personnel in the mid-1990s announcing a targeted expansion of the Tatmadaw to 500,000 soldiers reflect these staffing needs.[13]

In practice, however, the Tatmadaw has been challenged to meet these demands for new staff. Service in the armed forces is a dangerous and grueling existence subjecting enlisted men to combat, mistreatment by superior officers, low pay, and poor living conditions. Although military salaries have been adjusted on three occasions since 1988, double-digit inflation has rapidly eroded the purchasing power of army salaries. The minutes of a high-level SPDC meeting in September 2006 reported by Jane's Defense Weekly suggest that while reported recruitment rates appeared to rapidly increase between 2005 and 2006, average battalion strength had declined to only 140-150 per battalion, largely because of increasing desertion rates and soldiers going absent without leave.[14] The document reported a loss of 9,497 soldiers during a single four-month period in 2006, many due to desertions. In response, Adjutant General Thein Sein called for the army to recruit 7,000 soldiers per month, four times the actual monthly recruitment rate reported for mid-2005 and double the actual rate reported for mid-2006.[15] The staffing crisis has been exacerbated by the army's continued expansion: in the past five years, for example, the army has established at least seven new artillery divisions and several more armoured divisions.

Human Rights Watch interviews with soldiers who had recently served in the Burma army corroborate these reports. Soldiers consistently reported that battalions typically had 220 to 350 or more men prior to 2002, but that in the past five years staffing levels are more commonly 120 to 220 soldiers in a battalion. Noting that his light infantry battalion in Kayah State had only 150-170 men in 2006 because those who went on leave never returned, Htun Myint added that "I heard that other battalions also have fewer and fewer soldiers because people getting leave don't return, and because new battalions are always being created and the existing battalions have to give some of their soldiers to those battalions."[16]

Former Tatmadaw soldiers also told Human Rights Watch that many infantry battalions are extremely "top-heavy," with more officers and non-commissioned officers than privates. Some of them said there were 20 to 50 amputees still held in their battalion to keep up the numbers.[17] They also stated that discharges are never granted even after 10 or 20 years of service unless the applicant can bring in three to five new recruits to replace himself. In one extreme case, a former soldier said that in 2004-05 his infantry battalion had 200 soldiers, but of these 50 were amputees and only 20 were privates: "For example, in Column 2 in the frontline we were only four privates out of two companies, so we were always very tired. Column 2 headquarters had 25 soldiers, including officers and other ranks."[18]

Current staffing levels are unknown. In 2002 the SPDC informed Human Rights Watch that the army, navy, and air force numbered 350,000 men.[19] Independent sources cite similar numbers,[20] although the SPDC's statistics may substantially overstate current staffing levels.[21] The continued creation of new battalions coupled with steady attrition has led to falsified reporting within the army such as under-reporting desertion rates and inflating recruitment figures. What is beyond doubt is that the army is under constant pressure to increase recruiting to fill out new units and offset its high rates of attrition. This results in intense recruitment pressures on officers and units throughout the army and increasing rewards for anyone who can bring in new recruits.

Recruitment

The high ranking officers realized that recruitment by recruiting offices alone was insufficient, so they issued orders that recruitment should also be done as part of each battalion's operations. We had a quota system: we recruit for our battalion and also for other units like the Regional Command. Our battalion was ordered to recruit 12 people every four months. We couldn't meet this quota, so at every meeting they scolded the battalion officers. To solve the problem, battalion officers pressured their junior officers to recruit. We set a rule that soldiers who wanted their 30 days' annual leave must guarantee that they will return with at least one recruit. Any soldier who wanted a discharge after 10 years of service had to get four new recruits for the battalion before we would approve his discharge. That's why there is a problem of child soldiers.

-A former battalion commander[22]

When we reached Toungoo railway station a lance corporal approached me. He asked for my ID card and I told him I had a pass letter. He said no, an ID card is required, otherwise you'll go to prison. I was afraid so I said, "I'll give you money." He said, "I don't want money." I said, "I'll call my mother and she can vouch for me." He said, "I don't want to see your mother or father and I don't want money. I want you to join the army." I said no but he dragged me to a cell at the police station and told the police, "Detain him for a while" but without any charge. I think they had connections.

-Myin Win, describing being recruited for the second time in 2003, at age 14[23]

The Conscription Act of 1959 states that conscription to the Burma army for a period of six months to two years is allowable for men ages 18 to 35 and women ages 18 to 27.[24] In practice, neither women nor girls are recruited into the armed forces. Despite the Conscription Act, the SPDC maintains that "[t]he Myanmar Tatmadaw (Armed Forces) is an all volunteer army," and that "the minimum age for recruitment into the armed forces is 18 years."[25]

Key Factors in Child Recruitment

After the army's violent crushing of the 1988 pro-democracy demonstrations, the ensuing program of rapid army expansion was at odds with a dramatic drop in the number of volunteers. Rather than employing the Conscription Act to secure new soldiers, recruiters began using intimidation, coercion, and physical violence to gain new recruits and maintain the appearance of a volunteer army.

According to a former Tatmadaw battalion commander, "Those who volunteered were people who'd failed their school exams, or had financial or family problems. Volunteers probably account for only 5 percent of recruits, but even among those many don't want to fight, they just joined because of personal problems."[26] Most of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch were forced to join the army, and made similar estimates that no more than 5 or 10 percent of army recruits are volunteers.

A former Tatmadaw officer who had worked on recruitment matters at the War Office, the Tatmadaw's command headquarters in Rangoon, told Human Rights Watch that in 1996-1998 the army recruited 10,000-15,000 soldiers per year nationwide. Adjutant General Thein Sein's order in September 2006-reflecting the Tatmadawstaffing crisis discussed above-to recruit 7,000 soldiers per month, if implemented over the subsequent one-year period, would have resulted in rates of recruitment six times greater than rates in the previous decade.

These staffing trends are a major factor behind the army's recruitment of children, as noted by former soldiers who were interviewed for this report. Kyo Myint, who was forced into the army at age 14 in 1992 and remained a soldier until 2005, said his battalion was often in combat and had a high attrition rate so they received 10 to 30 new recruits every six months. Over time he noticed a steady increase in the prevalence of children among new recruits; eventually children comprised more than half of all new recruits arriving at the battalion.[27]

When asked his opinion on recent SPDC promises to stop recruiting children, a former Tatmadaw battalion commander told Human Rights Watch,

Even if there are orders [to demobilize children], battalion commanders will keep the children but hide them in the battalion compound or battalion farms, but they'll keep them because they don't have enough soldiers. When I was in the army we always felt we had too many officers and not enough soldiers.[28]

Poverty as a factor in children's vulnerability to recruitment

Prevailing social conditions often work to the advantage of recruiters. Burma's economy suffers from rapid inflation in basic commodity prices, a steadily declining currency, extremely poor infrastructure, and regular shortages in basic needs. Most analysts attribute these problems to economic mismanagement, rampant corruption, and the diversion of much of the country's finances and resources to the support of the military, while very little is spent on social services.[29] The World Food Programme reports that 32 percent of children under five are malnourished and lists among the main causes for this the restrictions on the movement of commodities, regional production disparities, and weak infrastructure.[30] School fees and expenses for school materials, even at primary level, are more than many families can afford, causing most children to be pulled out of school before completion so that they can work to support their family.[31]

This social and economic environment leads many children to leave their families, either because they feel like a burden on their parents or due to family fights or their involvement in petty crime activity. Out of school and looking for work, children are alone, exposed, and vulnerable to recruiters. Lacking knowledge about the law and their right not to be conscripted into the military, many are ill-equipped to resist recruiters' threats and coercion.

Myin Win, who was recruited twice as a child, before finally escaping in 2005, described the first time he was taken into the army at age 11:

I come from a very poor family. My father died when I was very young, and my mother is unemployed. I'm the youngest of 10 brothers and sisters.... I never went to school, and at age seven or nine I started working, tending herds of buffalos and cattle. I was born in 1989, and in 2000 I went to Rangoon to sell some garden produce like ginger. On the way I lost my travel pass from the Ward leader, and at Bago railway station some soldiers came on board and asked everyone for ID cards. I realized I'd lost my recommendation letter, and they took me. The same day they sent me to the Mingaladon Su Saun Yay in handcuffs.[32]

Recruiter quotas and incentives

The Tatmadaw operates specialized recruitment units throughout the country that are headquartered in Rangoon, Mandalay, Magwe, and Shwebo.[33] These command units oversee smaller detachments that are spread throughout the country. The No. 1 Tatmadaw Recruitment Command based in Da Nyein Gone, for example, has over 100 subordinate units located across lower Burma.[34] These units are tasked with obtaining recruits directly, as well as collecting recruits obtained by other armed forces units in their areas of jurisdiction. Recruitment detachments, which are often attached to regular Tatmadaw units, act as feeder units that transfer conscripts to one of the four main recruitment holding centers.

In addition to the pressure on recruitment units to fill new battalions and replace soldiers lost through desertion and attrition, the army has assigned recruitment quotas to other army units stationed throughout the country.[35] A former sergeant who served as clerk of his battalion in Rakhine state in 2004-05 explained,

The Defense Ministry imposes a quota. Each battalion had to recruit eight new soldiers every four months. For example, if someone requests leave, we'd tell him that if he brings back a new soldier he'll get paid 50,000 kyat,[36] no matter how you recruit him. That money is supposed to be for the recruit but really goes to the recruiter, and maybe he only gives the recruit 10,000 of it. Sometimes it came from the battalion budget, sometimes the battalion commander himself had to put in his own money, because if he didn't send 24 recruits a year he'd be summoned by the regional commander and he worried about that. That is why children are recruited. Sometimes we went to the recruiting centers and bought recruits from them.[37]

Another soldier who worked as a clerk in the headquarters of a military operations command (MOC) in 2004-05 stated that the MOC's 10 subordinate battalions were ordered to recruit soldiers:

Every battalion has to recruit at least two people, so that's 20 from the whole MOC, over a period of one or more months as specified by the orders from above. We sent them to the Su Saun Yay [recruit gathering center] in Mingaladon. They recruit them in various ways-they tell people they can get money or food, or they catch them in train stations or on the streets at night. When they're really desperate they just grab any beggar or any children they see. Also criminals who have been arrested, they tell them "the case is closed" but then take them to join the military.[38]

Army battalions and recruiting centers use various methods to reach their recruitment quotas. Commonly one or more non-commissioned officers are assigned to find recruits and are rewarded with cash and food for each recruit they obtain. Soldiers are also required to gain new recruits in order to obtain leave or a service discharge. A former sergeant who served as clerk of his battalion in Rakhine state in 2004-05 condemned the most common methods used: "This way to recruit is illegal, but it's still accepted [T]here are ways that the recruiting centers get children, for example by approaching them in train stations, asking for their ID and intimidating them, or saying they'll take care of them."[39]

Battalions may also issue orders to nearby villages to supply them with recruits. According to a health worker from Rakhine state, "Now they have two ways of recruiting: they come to the village and demand a certain number of recruits, or they demand [forced labor] porters and later keep them as recruits. When children go as porters and don't come back, people know they've been forced into the army."[40] Aung Moe, a former Tatmadaw soldier from Rakhine state, added that in recent years SPDC units in Kyauk Phyu township had imposed recruit quotas on local villages. Recent reports from Kachin state indicate that Burma army battalions based there have ordered village heads and other local authorities, including local fire brigades, to supply recruits, and that illegal teak traders have been forced to obtain recruits if they want to remain in business.[41] A resident of Kachin state told us that in her town a local government official notified households that on August 3, 2007 a government order had specified that each town quarter must provide two recruits.

Human Rights Watch has also received reports (which we have been unable to confirm) that some non-state armed groups operating in Shan state under ceasefire agreements with the SPDC have received requests from SPDC battalions to obtain recruits from the areas that these groups control.[42]

The majority of forced recruitment, however, is still done by soldiers either on recruiting duty or seeking incentives from their battalions. As noted by Htun Myint, who served as a child soldier until 2006, "When battalions return from the frontline they change into mufti [military jargon for civilian clothing], go to the train and bus stations and catch young people to send to the recruiting center. If they recruit one soldier they can get 30,000 kyat and a sack of rice as reward from the battalion officers. Also, if you want to transfer to another battalion or leave the army you have to get three or four recruits."[43] In 2006 Maung Zaw Oo, 16 at the time, was ordered to accompany his battalion's recruiting sergeant to Yezagyo town to get recruits. He says they rented a hotel room for five days for 10,000 kyat and the sergeant went to the train station every morning looking for recruits:

The targets are usually bottle and bag collectors. Sergeant Tin Htun would grab a couple of them, take them to a teashop and buy them lots of food, then show them lots of money. Then he'd say, "You need some education. Join the army and they'll send you to training school and you'll get more uniforms and clothes than you can even carry, and after training you'll get one stripe [lance corporal rank] and lots of money." The sergeant has links with the police. He said there are two types of targets: if they were wearing good clothes, he'd get the police to ask them for ID cards and threaten them. If they were wearing poor clothes, he'd approach them directly and flash money in front of them. He got four people, one was 60 years old and the others were about 20, scrap collectors. He sold the 60 year old to another recruiter for four-and-a-half bottles [slang for 45,000 kyat]. The other recruiter paid that much because he was a sergeant who's planning to retire from the army so he needs to bring in recruits. Sergeant Tin Htun took the other three back to the battalion and for each recruit he received 20,000 kyat cash, a sack of rice, and a tin of cooking oil.[44]

Htun Myint related an extreme case of a recruiter forcibly enlisting an active duty soldier:

One soldier got leave to visit his family but wasn't sure of the way home. A recruiter in the train station stopped him, offered him food and then tried to recruit him. When he showed his soldier papers the recruiter tore them up and took him to the recruiting center anyway. This happened to someone in our neighboring battalion, I heard it from a senior officer.[45]

Recruiters target public places, including markets and bus stations, looking for unemployed and vulnerable adolescents and young men. Adolescents traveling alone or with other young men by train are particularly vulnerable to recruitment, as train stations have become the favorite hunting grounds of recruiters.

A 16-year-old volunteer recruit, Ko Ko Aung, described the scene on his arrival at Mingaladon Su Saun Yay (recruit holding centre) in April 2006:

There were many, and most had been forced to come. They'd been brought by soldiers who filled up their forms, gave them to the officer, and then went to a room to get their money. The police had caught those people and then called the soldiers from the Su Saun Yay who went and brought them back. After filling out my form and getting his money, the Su Saun Yay soldier went out to the bus station to catch more people.[46]

A common tactic is to demand to see people's national registration cards (NRC), knowing that most adolescents do not carry them. If the adolescent presents a student identity card, he or she may be told it is an unacceptable form of identification. Typically the recruiter then offers a choice of joining the army, or a long prison term for failure to carry a card. Although minors cannot be legally imprisoned for failing to carry an NRC, many adolescents are unaware of this and can be easily intimidated into believing it.

According to Burmese law, children can get a "temporary" card once they reach age 10, which they can convert to a permanent card at age 18.[47] Most children interviewed by Human Rights Watch were unaware of this and believed that registration cards are only available to those over 18. Maung Zaw Oo had been aware of the rule but was denied a card when he tried to apply for one: "My aunt and I had gone to register and they said I'm underage so they wouldn't give it. My brother applied when he was about 15 and had to pay 35,000 [kyat] for his, but when I went they said I would have to renew it again anyway when I reach 18 so they said I should just wait until then."[48] Rather than pay the expensive card issuance fee twice, many families opt to wait until the children reach 18. Even those who have cards at a younger age are unlikely to carry them on a daily basis, because the card is very expensive to replace if it is lost. At present the SPDC is reportedly pressing local officials to ensure that all adults over 18 register for NRC cards, probably in anticipation of a constitutional referendum and census which the SPDC has stated will be held by 2009. This has made it even harder for children under 18 to get cards: with adults prioritized in the queue, minors reportedly have to wait up to several months now to be issued an NRC.

A resident of a town in Kachin state described to Human Rights Watch being notified that anyone found on the streets after 8:30 p.m. would be recruited and would not be released even if they paid a fine or bribe. She reported that some men and boys were conscripted on leaving a cinema at 9 p.m. one night.[49] Similarly, a community leader from Myitkyina stated that youth leaving a cinema in Alam at 9 p.m. had been arrested by Myitkyina police offers for "lurking in dark places" and offered the choice of a jail term or army enlistment; in at least one case a parent was able to bribe police officials to release her son.[50] Htun Myint's recruitment in 2001 took place in similar circumstances:

I was about 11 years old and a student in Fifth Standard. When I was returning from watching videos one night, it was dark and there are no lights along the road to my house. I met two soldiers and they arrested me for "hiding in the dark." They took me to the local Su Saun Yay unit at their army camp and asked me, "Do you want to join the army or go to jail?" I was afraid of jail so I said I'd join the army. They asked about my parents' names and my family members and they filled in a paper. They asked my age so I told them the truth, but they wrote 18.[51]

Human Rights Watch continued to receive accounts of child recruitment as this report went to press in October 2007. One eyewitness told Human Rights Watch that while traveling by train in early September 2007, he saw many new recruits who appeared to be between age 14 and 17 among a group of approximately 140 new recruits being transported on the train from Rangoon to Yemethin, near Mandalay.[52]

Children as Commodities: The Recruit Market

The officers are corrupt and the battalions have to get recruits, so there's a business. The battalions bribe the recruiting officers to get recruits for them. These are mostly underage recruits but the recruiting officers fill out the forms for them and say they're 18.

-Than Myint Oo, forcibly recruited twice as a child[53]

The pressure to obtain recruits, and the money and power incentives available to those who do so, have turned recruits into commodities that are bought and sold with impunity. The former sergeant who served as clerk of his battalion in Rakhine state in 2004-05 said that at that time the going price was 30,000 to 50,000 kyat per recruit, paid to the recruiting center officers so they would credit the recruit toward the battalion's quota.[54] A battalion commander recounted the following complex transactions:

In 2005 in Mingaladon [a major recruitment holding facility] the price of a new soldier was 25-35,000 kyat, which must be paid [to the recruiting officers] if the battalion couldn't recruit enough itself. Battalions have to find this money to buy recruits. We buy them from civilian brokers and also from soldier brokers in Mingaladon. We also negotiated with the Su Saun Yay units [holding camps for new recruits], because they could reject our recruits if they were underage or underweight, so we had to bribe them. Now the prices are getting higher. It's like a marketplace between the battalions and the Su Saun Yays. The battalions recruit and then receive a receipt from the recruitment unit, and then we've done our job. If we want them back after the training we request that with another form. All types of battalions have these quotas.[55]