Summary

Being in isolation to me felt like I was on an island all alone[,] dying a slow death from the inside out.

—Letter from Kyle B. (pseudonym), from California to Human Rights Watch, May 3, 2012.

Every day, in jails and prisons across the United States, young people under the age of 18 are held in solitary confinement.[1] They spend 22 or more hours each day alone, usually in a small cell behind a solid steel door, completely isolated both physically and socially, often for days, weeks, or even months on end. Sometimes there is a window allowing natural light to enter or a view of the world outside cell walls. Sometimes it is possible to communicate by yelling to other inmates, with voices distorted, reverberating against concrete and metal. Occasionally, they get a book or bible, and if they are lucky, study materials. But inside this cramped space, few contours distinguish one hour, one day, week, or one month, from the next.

This bare social and physical existence makes many young people feel doomed and abandoned, or in some cases, suicidal, and can lead to serious physical and emotional consequences. Adolescents in solitary confinement describe cutting themselves with staples or razors, hallucinations, losing control of themselves, or losing touch with reality while isolated. They talk about only being allowed to exercise in small metal cages, alone, a few times a week; about being prevented from going to school or participating in any activity that promotes growth or change. Some say the hardest part is not being able to hug their mother or father.

The solitary confinement of adults can cause serious pain and suffering and can violate international human rights and US constitutional law. But the potential damage to young people, who do not have the maturity of an adult and are at a particularly vulnerable, formative stage of life, is much greater.

Experts assert that young people are psychologically unable to handle solitary confinement with the resilience of an adult. And, because they are still developing, traumatic experiences like solitary confinement may have a profound effect on their chance to rehabilitate and grow. Solitary confinement can exacerbate, or make more likely, short and long-term mental health problems. The most common deprivation that accompanies solitary confinement, denial of physical exercise, is physically harmful to adolescents’ health and well-being.

Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union estimate that in 2011, more than 95,000 youth were held in prisons and jails. A significant number of these facilities use solitary confinement—for days, weeks, months, or even years—to punish, protect, house, or treat some of the young people who are held there. Solitary confinement of youth is, today, a serious and widespread problem in the United States.

This situation is a relatively recent development. It has only been in the last 30 years that a majority of jurisdictions around the country have adopted various charging and sentencing laws and practices that have resulted in substantial numbers of adolescents serving time in adult jails and prisons. These laws and policies have largely ignored the need to treat young people charged and sentenced as if adults with special consideration for their age, development, and rehabilitative potential.

Young people can be guilty of horrible crimes with significant consequences for victims, their families, and their communities. The state has a duty to ensure accountability for serious crimes, and to protect the public. But states also have special responsibilities not to treat young people in ways that can permanently harm their development and rehabilitation, regardless of their culpability.

This report describes the needless suffering and misery that solitary confinement frequently inflicts on young people; examines the justifications that state and prison officials offer for using solitary confinement; and offers alternatives to solitary confinement in the housing and management of adolescents. The report draws on in-person interviews and correspondence with more than 125 individuals who were held in jails or prisons while under age 18 in 19 states, and with officials who manage jails or prisons in 10 states, as well as quantitative data and the advice of experts on the challenges of detaining and managing adolescents.

This report shows that the solitary confinement of adolescents in adult jails and prisons is not exceptional or transient. Specifically, the report finds that:

- Young people are subjected to solitary confinement in jails and prisons nationwide, and often for weeks and months.

- When subjected to solitary confinement, adolescents are frequently denied access to treatment, services, and programming adequate to meet their medical, psychological, developmental, social, and rehabilitative needs.

- Solitary confinement of young people often seriously harms their mental and physical health, as well as their development.

- Solitary confinement of adolescents is unnecessary. There are alternative ways to address the problems—whether disciplinary, administrative, protective, or medical—which officials typically cite as justifications for using solitary confinement, while taking into account the rights and special needs of adolescents.

Adult jails and prisons generally use solitary confinement in the same way for adolescents and adults. Young people are held in solitary confinement to punish them when they break the rules, such as those against talking back, possessing contraband, or fighting; they are held in solitary confinement to protect them from adults or from one another; they are held in solitary confinement because officials do not know how else to manage them; and sometimes, officials use solitary confinement to medically treat them.

There is no question that incarcerating teenagers who have been accused or found responsible for crimes can be extremely challenging. Adolescents can be defiant, and hurt themselves and others. Sometimes, facilities may need to use limited periods or forms of segregation and isolation to protect young people from other prisoners or themselves. But using solitary confinement harms young people in ways that are different, and more profound, than if they were adults.

Many adolescents reported being subjected to solitary confinement more than once while they were under age 18. Forty-nine individuals—more than a third—of the seventy-seven interviewed and fifty with whom we corresponded described spending a total of between one and six months in solitary confinement before their eighteenth birthday.

Adolescents spoke eloquently about solitary confinement, and how it compounded the stresses of being in jail or prison—often for the first time—without family support. They talked about the disorientation of finding themselves, and feeling, doubly alone.

Many described struggling with one or more serious mental health problems during their time in solitary confinement and of sometimes having difficulty accessing psychological services or support to cope with these difficulties. Some young people, particularly those with mental disabilities (sometimes called psychosocial disabilities or mental illness, and usually associated with long-term mental health problems), struggled more than others. Several young people talked about attempting suicide when in isolation.

Adolescents in solitary confinement also experienced direct physical and developmental harm, a consequence of being denied physical exercise or adequate nutrition. Thirty-eight of those interviewed said they had experienced at least one period in solitary confinement when they could not go outside. A few talked about losing weight and going to bed hungry.

The report finds that young people in solitary confinement are deprived of contact with their families, access to education and to programming, and other services necessary for their growth, development, and rehabilitation. Twenty-one of the young people interviewed said they could not visit with loved ones during at least one period of solitary confinement. Twenty-five said they spent at least one period of time in solitary confinement during which they were not provided any educational programming at all. Sixteen described sitting alone in their cell for days on end without even a book or magazine to read.

But as a number of jail and prison officials recognize, solitary confinement is costly, ineffective, and harmful. There are other means to handle the challenges of detaining and managing adolescents. Young people can be better managed in specialized facilities, designed to house them, staffed with specially trained personnel, and organized to encourage positive behaviors. Punitive schemes can be reorganized to stress immediate and proportionate interventions and to strictly limit and regulate short-term isolation as a rare exception.

Solitary confinement of youth is itself a serious human rights violation and can constitute cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment under international human rights law. In addition, the conditions that compound the harm of solitary confinement (such as lack of psychological care, physical exercise, family contact, and education) often constitute independent, concurrent, and serious human rights violations. Solitary confinement cannot be squared with the special status of adolescents under US constitutional law regarding crime and punishment. While not unusual, it turns the detention of young people in adult jails and prisons into an experience of unquestionable cruelty.

It is time for the United States to abolish the solitary confinement of young people. State and federal lawmakers, as well as other appropriate officials, should immediately embark on a review of the laws, policies, and practices that result in young people being held in solitary confinement, with the goal of definitively ending this practice. Rather than being banished to grow up locked down in isolation, incarcerated adolescents must be treated with humanity and dignity and guaranteed the ability to grow, to be rehabilitated, and to reenter society.

Key Recommendations

To the US Federal Government and/or State Governments

- Prohibit the solitary confinement of youth under age 18.

- Prohibit the housing of adolescents with adults, or in jails and prisons designed to house adults.

- Strictly limit and regulate all forms of segregation and isolation of young people.

- Monitor and report on the segregation and isolation of adolescents.

- Ratify human rights treaties protecting young people without reservations.

Methodology

This report is the product of a joint initiative—the Aryeh Neier fellowship—between Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union to strengthen respect for human rights in the United States.

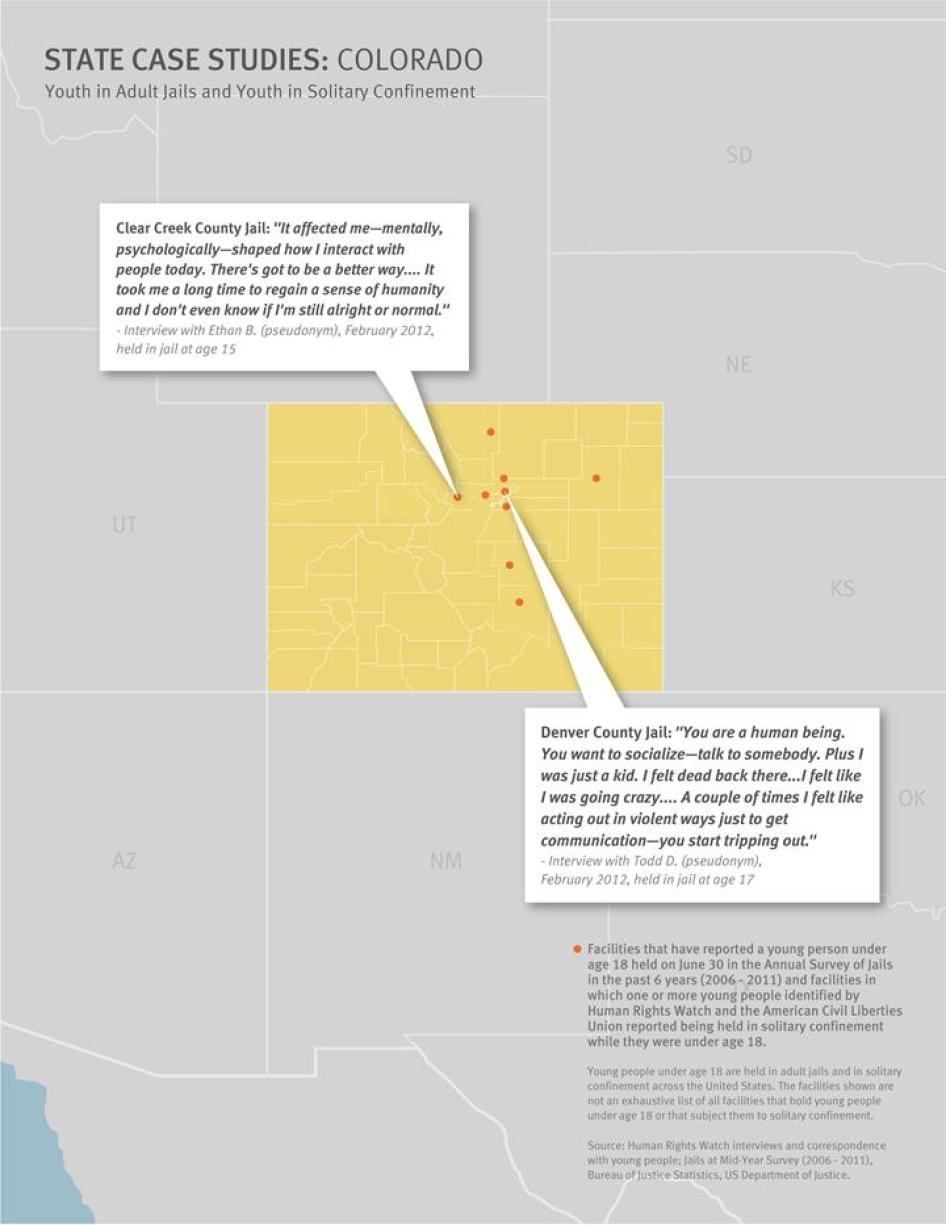

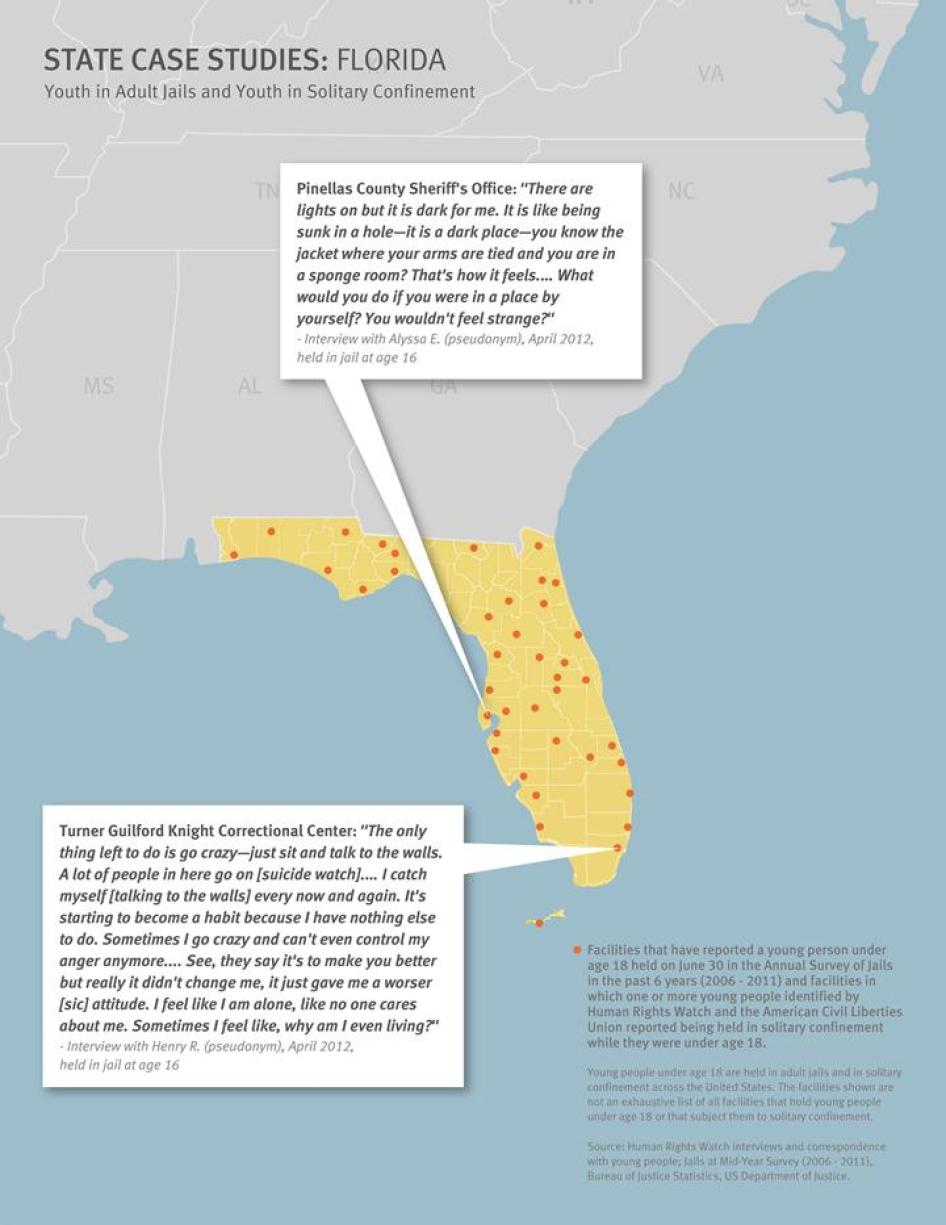

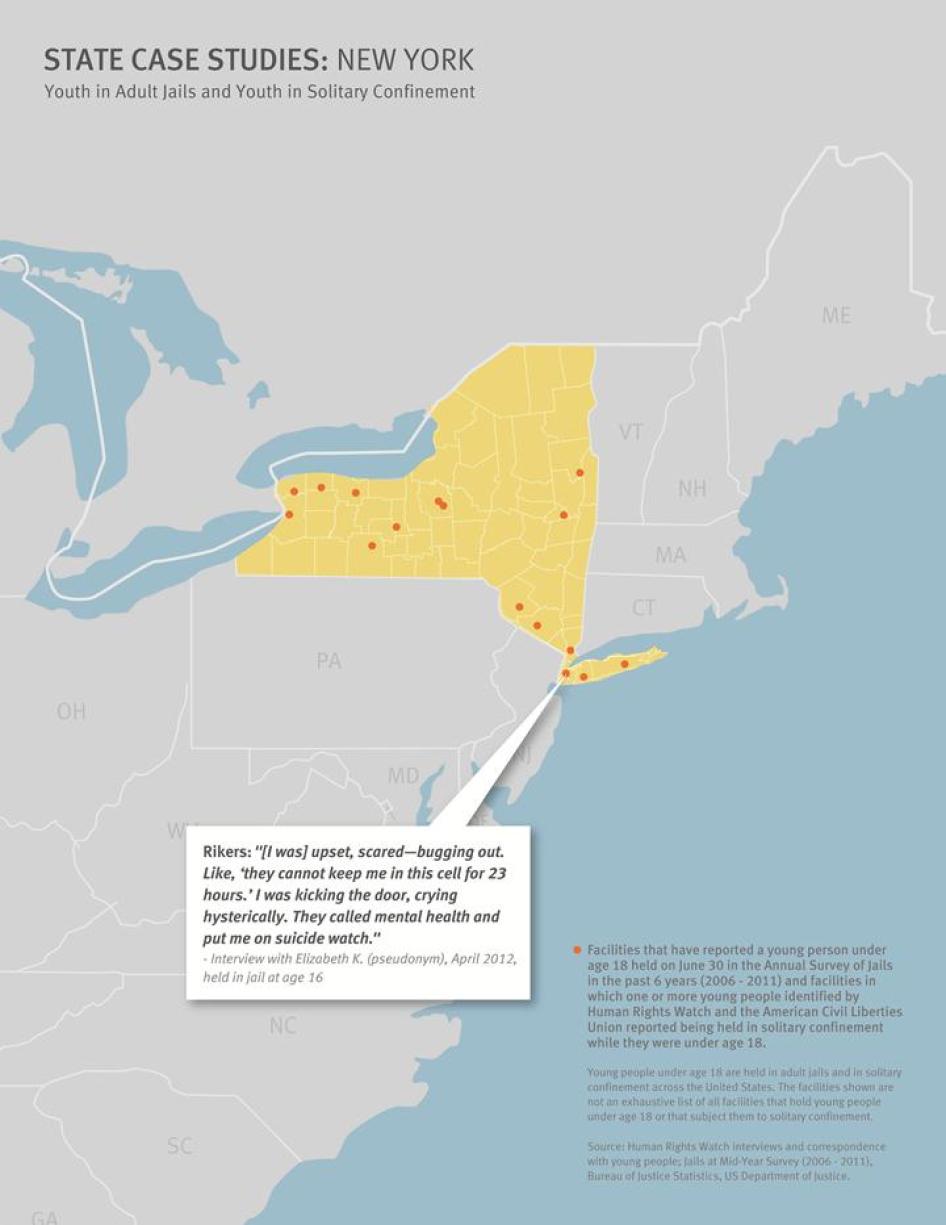

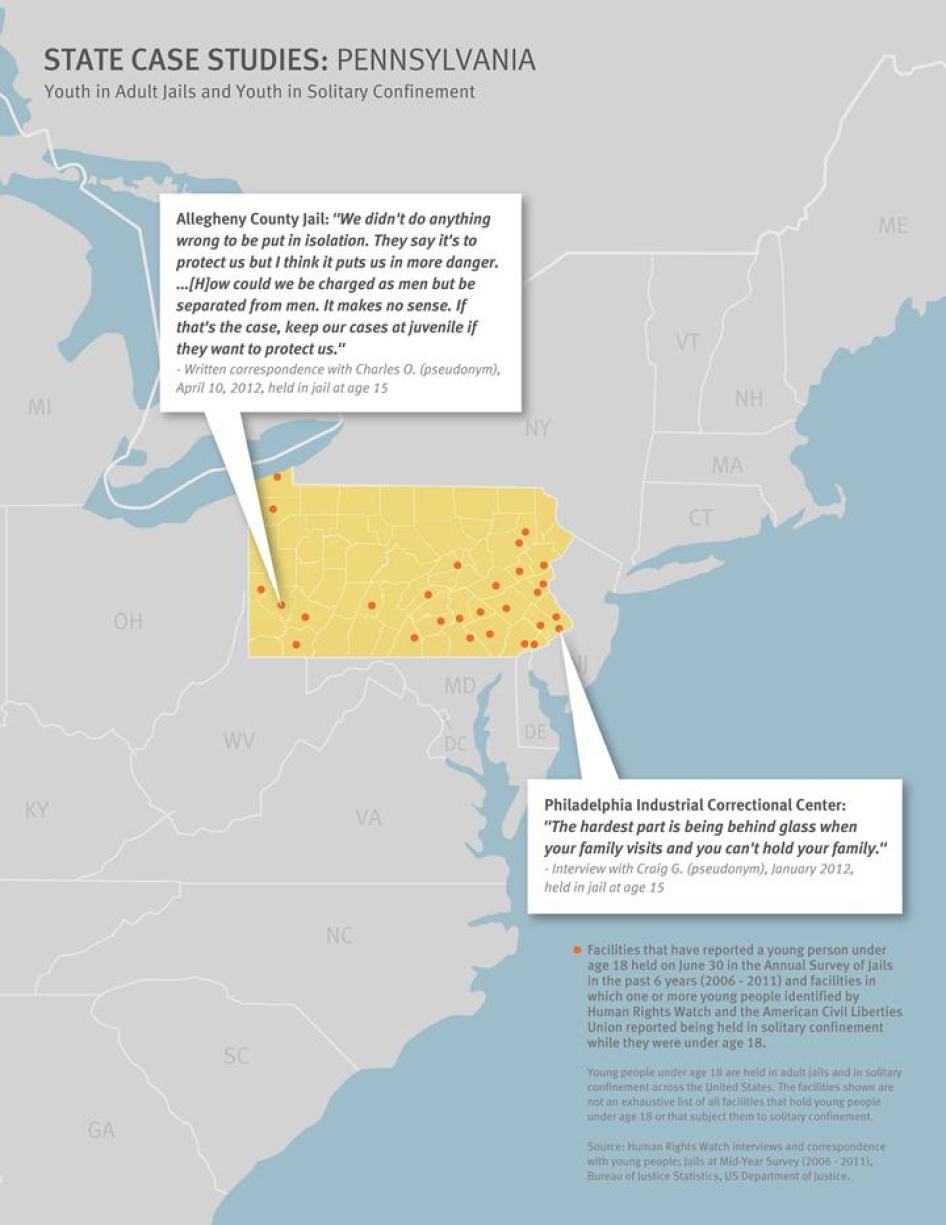

This report is based on interviews and correspondence undertaken between December 2011 and July 2012 with 127 individuals who were detained in jail or prison while under age 18 in Alabama, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, Wisconsin, and Virginia. Of those, Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union interviewed in person 77 individuals who, collectively, had been held at more than 50 jails and prisons in Colorado, Florida, Michigan, New York and Pennsylvania while under age 18. Of these, 66 were male and 11 were female; 57 of them were between 18 and 25 years old at the time of the interviews; 20 were under age 18. Of the 50 with whom Human Rights Watch corresponded, all were male; 24 were between the ages of 18 and 25, and 10 were under age 18.

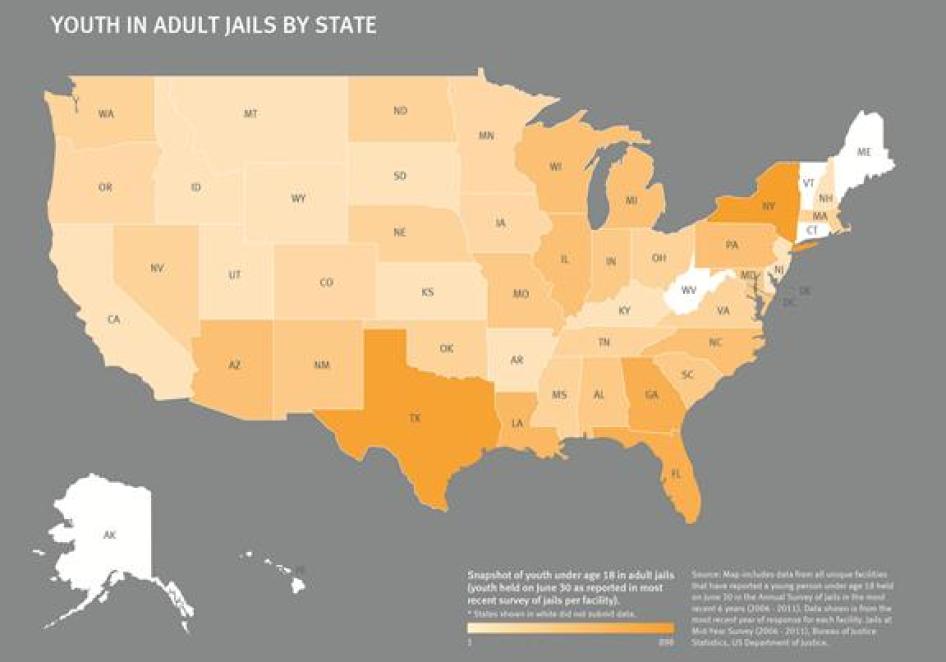

In selecting jurisdictions for focused research, Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union prioritized states that consistently report holding youth under age 18 in adult jails and prisons, and charging young people as if they are adults. Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union identified individuals who had been subjected to solitary confinement in those jurisdictions through outreach to family members; contact with defense attorneys and advocacy networks; and through an advertisement in Prison Legal News (which has broad circulation in jails and in prisons). Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union also identified some individuals by writing to or seeking to interview all adolescents under age 18 at a particular facility or within a particular Department of Rehabilitation or Correction; all young people convicted of certain offenses likely to be associated with isolation (such as battery by a prisoner, assault on a corrections officer, or throwing or expelling bodily fluids at or towards a public safety worker); or young people serving particularly long sentences, such as life without parole.

Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union were not able to conduct interviews in every state that confines adolescents in adult jails and prisons, nor in every county in the states visited. Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union did not seek individual administrative, disciplinary, or medical records for most individuals interviewed.

All individuals interviewed about their experience provided informed consent to participate in this research. Interviews in jails and prisons were conducted in private, with no jail or prison staff within earshot; interviews outside of jails and prisons were also conducted in private. For some of the interviews, the Human Rights Watch/American Civil Liberties Union researcher in charge of the project was accompanied by an attorney (including sometimes the individual’s defense attorney), social worker, or NGO partner whose presence as an observer was explained to the interviewee. When accompanied by others, the Human Rights Watch/American Civil Liberties Union researcher led the questioning, using substantially the same semi-structured questionnaire for all interviews with those who had been held in jail or prison. The researcher repeatedly assured interviewees that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any and all questions. Also, the researcher gave no incentives to interviewees and took great care to avoid re-traumatizing them. One individual declined to be interviewed, and one individual refused to allow his or her testimony to be used for this research.

Some interviewees asked that their names be used in this report so they could more directly participate in bringing attention to their personal experience. But due to concerns over the safety of the many interviewees who did not want their identity disclosed, Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union decided to use pseudonyms to disguise the identity of all interviewees who were held in jail or in prison, and of individuals whose cases Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union learned of through attorneys or family members. In most cases, Human Rights Watch has also withheld certain other identifying information to protect an individual’s privacy and safety.

Human Rights Watch sent surveys regarding the challenges of detaining and managing youth and the use of isolation to more than 590 county jail facilities and received responses from or interviewed, collectively, more than 98 county jail officials in Colorado, Florida, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Human Rights Watch also interviewed or corresponded with state prison officials in Colorado, Florida, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

The Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction refused Human Rights Watch’s request to interview young people under their care due to the department’s “long-standing practice not to provide media access to [the department’s] incarcerated juveniles” and because “there [were] legal concerns about whether the juveniles can consent to interviews.”[2] It also refused to allow us to privately interview inmates who had entered its care while under age 18 who were now adults, stating that it would only allow interviews of inmates who were screened “to determine if they are eligible and appropriate for participation” if “the Public Information Officer at [each] facility [were] to be present during th[ose] interviews.”[3] Following our standard research methodology in situations of confinement, we declined to submit to official monitoring or selection of interviews.

The Wisconsin Department of Corrections also denied Human Rights Watch’s request to interview individuals in their care. It cited concerns that interviewing young people identified through defense counsel and public records, “may introduce bias” in the results; that, if the intent was to obtain information about county facilities, interviews should be conducted “when the subject is in a county jail facility”; that the department would not permit questioning about experiences in county facilities without “written approval from the respective Jail Administration or Sheriff”; and that it would not permit interviews without prior approval of questions to be asked (about prolonged isolation) and any other “information necessary to take into account possible issues that could lead to any possible negative effects that the interview may have on the subject’s mental health status.”[4]

Human Rights Watch interviewed officials at the US Department of Justice and state officials charged with collecting data and monitoring compliance with federal law, such as the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act.

Finally, Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union interviewed dozens (and had background discussions with scores) of third parties with relevant expertise or experience dealing with the consequences of the solitary confinement of adolescents, including prisoner’s family members; victims of crime and their family members; attorneys; as well as medical, corrections, educational, and psychological experts.

This report, especially Appendix 1, contains substantial statistical data. Most of the descriptive statistics utilized in this report were extracted from three Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) data sources: the annual Prisoners in [Year] reports; the annual Jail Inmates at Midyear reports; and the raw Survey of Jails data files, which are used to generate the Jail Inmates at Midyear report. Further information on the statistical methodology used may be found in Appendix 1.

I. Background: Kids in an Adult System

[C]hildren are constitutionally different from adults … [J]uveniles have diminished culpability and greater prospects for reform … [and] are less deserving of the most severe punishments … [C]hildren have a lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility[;] … [c]hildren are more vulnerable . . . to negative influences and outside pressures[;] … [a]nd … a child’s character is not as well formed as an adult’s.

—Miller v. Alabama, United States Supreme Court, 2012 (No. 10 ‐ 9646, slip op. at 8 (2012)).

For much of the last century, people under the age of 18 who came into conflict with the law in the United States were detained (when necessary), tried or adjudicated, and held accountable in the juvenile justice system. In rare cases, and if in the best interests of the child and the public, juvenile court judges could waive a delinquency case into the adult criminal justice system. But this was far from common.[5]

Though they have since declined, in the late 1980s and through the mid-1990s, rates of some categories of juvenile crime, particularly serious violent crime, increased significantly.[6] Concern about this development led to a proliferation of new legal mechanisms for subjecting children to criminal trial and punishment as if they were adults.[7] The stated goal of most of these policies was deterrence through retributive punishment: “adult time for adult crime.”[8]

As a result, each year tens of thousands of adolescents are now treated as adults. How young people come to be charged, detained, and punished as adults, however, is a function of a complex thicket of state and federal law and policy. There is no single approach within or among states. Yet the consequences for young people treated the same as adults are profound.

Youth Charged as if Adults

Nationally, young people held in adult facilities are charged and convicted of offenses ranging from drug and property crimes to the most serious violent crimes. The most common mechanisms for imposing “adult time for adult crime” include offense-based exclusion from the juvenile justice system, prosecutorial “direct-file” of youth cases in the adult system, and “once an adult always an adult” laws.[9] For many young people, entering the adult criminal justice system is a path of no return, as not all states have mechanisms to transfer or waive jurisdiction back to the juvenile system, or to impose a blended sentence of punishments in both the juvenile and adult systems.[10] Yet some evidence suggests that many adolescents charged as if adults are not actually sentenced to time in prison.[11]

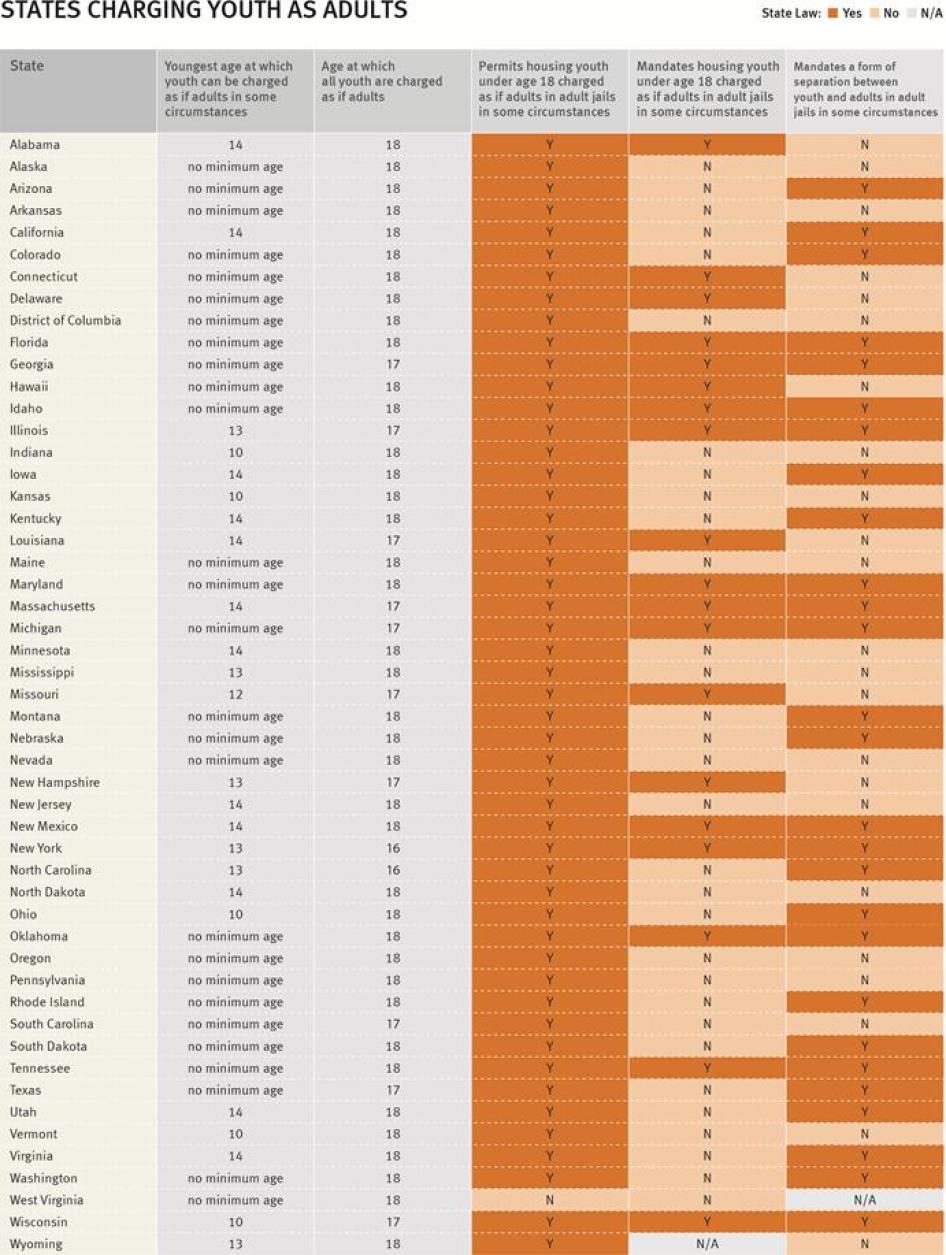

|

Racial and socioeconomic disparities are pervasive within the criminal justice system. As Human Rights Watch has documented, in California, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania, black adolescents are significantly more likely to be serving a sentence of life without parole than white adolescents.[12] Other studies have found that minority adolescents receive harsher treatment than similarly-situated white adolescents at every stage of the criminal justice system.[13] Within the juvenile and adult criminal justice systems, young people of color are disproportionately represented at every stage, from arrest to sentencing.[14] People with scant financial means are also often unable to afford bail, and as a result end up spending lengthy periods in pre-trial detention.[15] Consequently, economically disadvantaged adolescents, including those who are never convicted, can endure substantial adult jail time. These racial and socioeconomic disparities are interconnected: in New York City in 2010, blacks and Hispanics constituted 89 percent of all pretrial detainees held on bail of $1,000 or less.[16] |

Many of the young people interviewed for this report were accused, tried, or convicted for serious crimes, even homicide. Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union interviewed more than a dozen young people serving life without parole for murder or felony murder.[17] But Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union also interviewed young people arrested, tried, or convicted of non-violent offenses, drug, and property crimes. For example, of the 26 young people interviewed in Florida prisons, five were convicted of non-violent offenses, such as burglary or drug possession.[18]

Yet, regardless of their conduct, it is well established that adolescents have a potential for development and rehabilitation that is distinct from that of adults. In addition, adolescents deprived of their liberty have significant developmental needs and rights that are distinct from those of adults.

Youth Are Different

The cornerstone principle of the juvenile justice system in the United States is the idea that young people are different from adults. This is a reflection of psychological and physiological facts about how adolescents and their needs grow and change, as they become adults; it is also a principle of international and domestic law. The juvenile justice system seeks to rehabilitate young people and facilitate their development so that they may be reintegrated into society. The adult criminal justice system, with its focus on punishment, does not unequivocally prioritize rehabilitation, though the law of some states and international human rights law mandate it.[19]

Young people have needs that differ in nature and degree from those of adults because they are still developing physically and psychologically. These include specific physical needs for exercise and a balanced diet; as well as special psychological, social, and emotional needs. “As a transitional period,” reports one study, “adolescence is marked by rapid and dramatic [individual] change in the realms of biology, cognition, emotion, and interpersonal relationships and by equally impressive transformations in the major contexts in which children spend time.”[20]

Physiological Differences and Needs

During adolescence, the body changes significantly, including through the development of secondary sexual characteristics. Boys and girls gain height, weight, and muscle mass, as well as pubic and body hair; girls develop breasts and begin menstrual periods, and boys’ genitals grow and their voices change.[21] The American Academy of Pediatrics therefore recommends a spectrum of age-differentiated examinations and assessments for adolescents related to physical, dental, and vision care.[22] This includes developmental screenings (and health care needs) that differ from early, middle, to late adolescence.[23]

Psychological Differences: Impulsivity, Capacity for Change, and Developmental Needs

Recent scientific findings revealing that the human brain goes through dramatic structural growth during teen years have overturned earlier assumptions regarding the completion of brain development at early adolescence.[24] These findings have significant implications for our understanding of teenagers’ volition and culpability, their capacity to change and develop, and their psychological needs.

The most dramatic difference between the brains of teens and young adults is the development of the frontal lobe.[25] The frontal lobe is responsible for cognitive processing, such as planning, strategizing, and organizing thoughts and actions. Researchers have determined that one area of the frontal lobe, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, is among the last brain regions to mature, not reaching adult dimensions until a person is in his or her twenties.[26] This part of the brain is linked to “the ability to inhibit impulses, weigh consequences of decisions, prioritize, and strategize.”[27] As a result, teens’ decision-making processes are shaped by impulsivity, immaturity, and an under-developed ability to appreciate consequences and resist environmental pressures.

The malleability of an adolescents’ brain development implies that teens through their twenties may be particularly amenable to change and rehabilitation as they grow older and attain adult levels of development.[28] This malleability also raises questions about the effects of stress and trauma on adolescent development during this formative period.

As detailed in section II, the particular physical and psychological characteristics of adolescents make solitary confinement particularly detrimental to healthy development and rehabilitation.

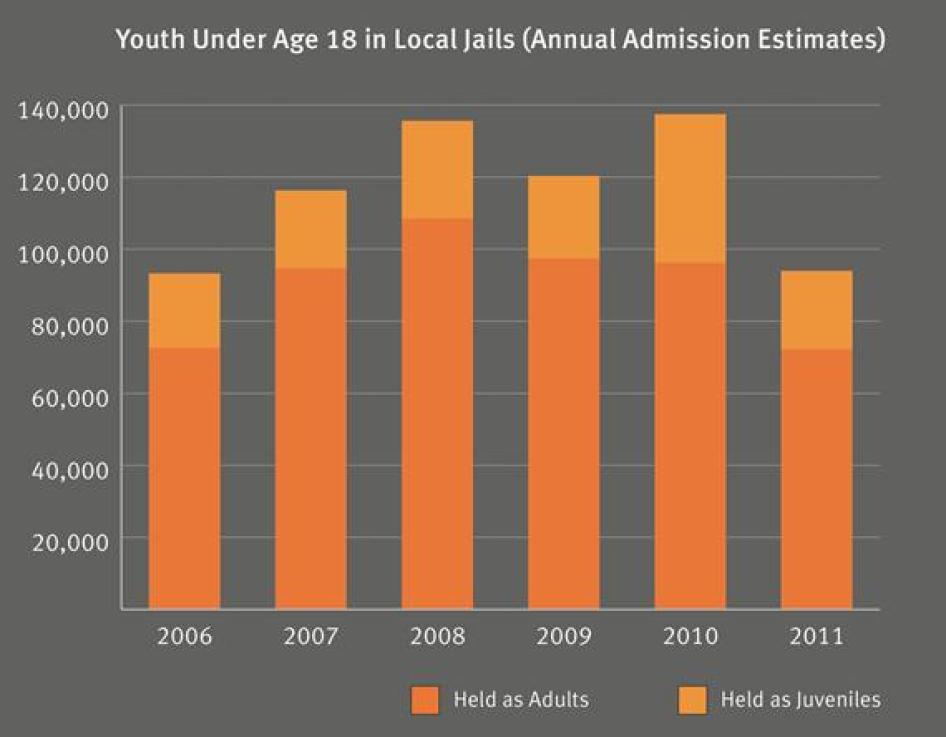

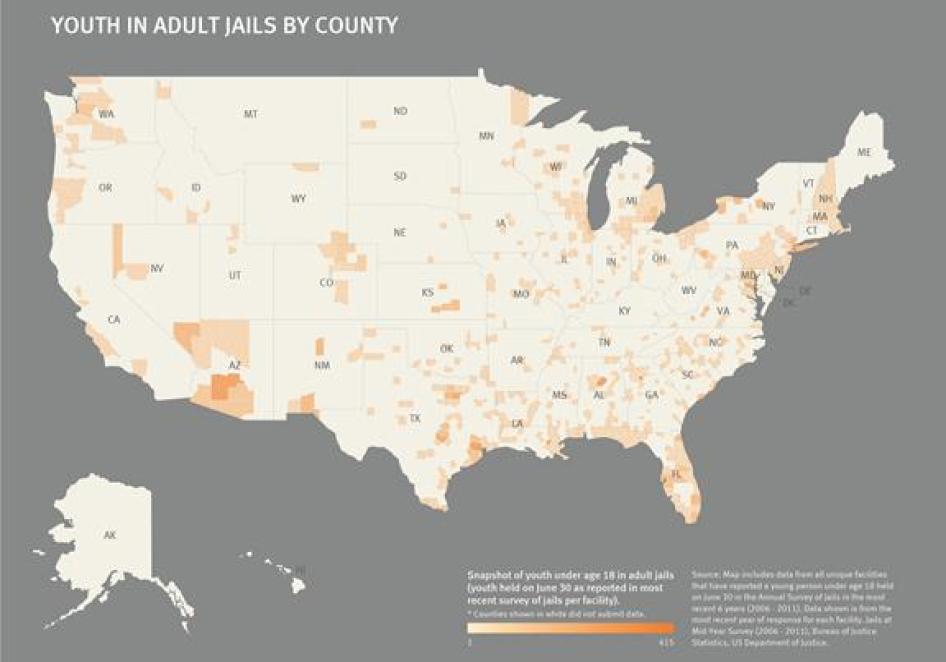

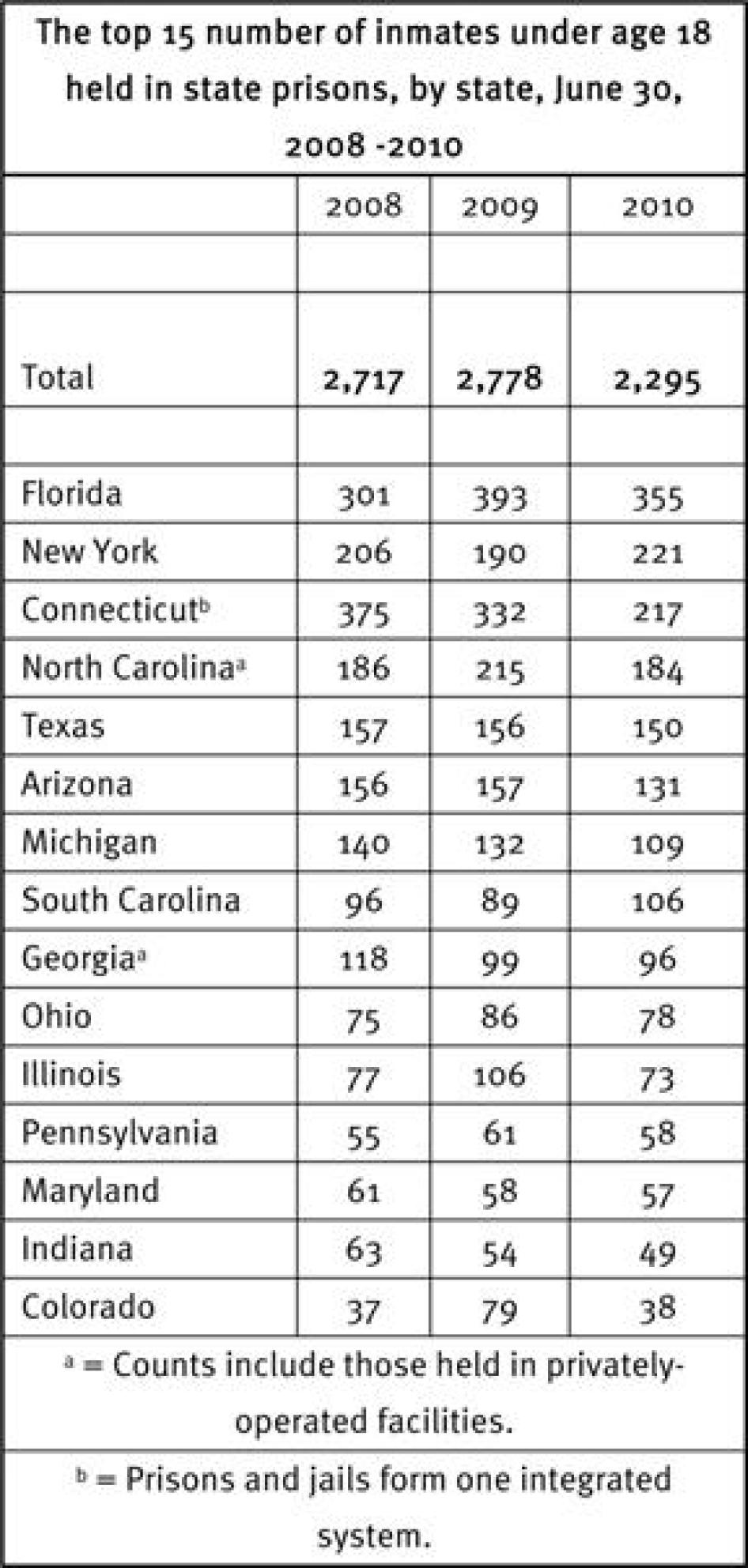

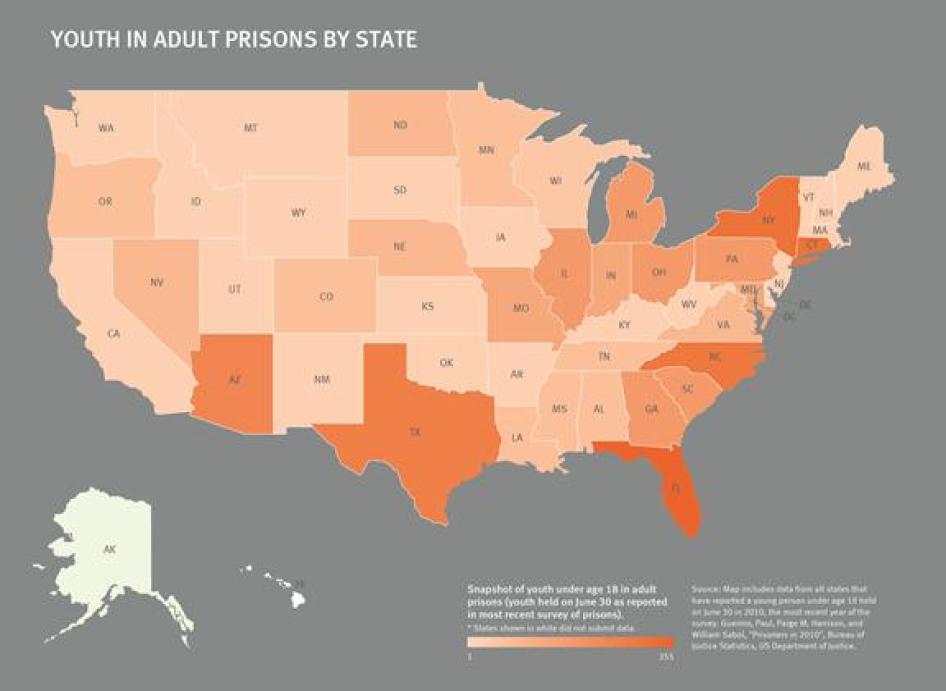

Adult Detention Regimes

In the United States, many of those accused or convicted of criminal offenses are held in jails or prisons. Prisons generally hold only those convicted of crimes and sentenced to more than a year of incarceration. Based on the available data, Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union estimate that in the last 5 years, more than 93,000 young people under age 18 were held in adult jails and that more than 2,200 young people under age 18 were held in adult prisons every year (see Appendix 1 for detailed information and additional numbers). While some young people turn 18 before they enter prison, others are not sentenced to spend time in prison, making the high numbers of young people held in jail particularly alarming.[29]

State Law and Practice - Jails

Once charged in the adult criminal justice system, adolescents in many states are taken to adult jails.[30] Some states, such as Wisconsin, mandate that all individuals charged in criminal court be detained in adult jail pre-trial.[31] Once detained in adult facilities, some states require that young people under 18 be kept separate from adults in pre-trial facilities (often mandating separation by “sight and sound”).[32] Other states leave it to individual facilities to sort out how and whether young people need to be protected. Some facilities separate young people of certain ages from adults. In some jails in Michigan (where 17 year olds are considered adults in the criminal justice system), for example, 16 year olds are generally separated from adults while 17 year olds are held with adults.[33]

Federal law—the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA)—creates financial incentives for states to treat young people differently from adults, including by diverting young people subject to the jurisdiction of the juvenile justice system (and certain categories of misdemeanants) from adult facilities. [34] Adolescents who are protected by the federal law must either never be held in adult facilities (in the case of status offenders [35] ) or be moved from adult facilities within 6 hours (and must be sight and sound separated from adult inmates while there). [36] However, this law is not currently interpreted to cover adolescents who are charged with felonies in the adult system, leaving youth protected only by state law. [37]

State Law and Practice - Prisons

In most states, young people who are convicted as if adults and sentenced to more than a year of incarceration are then sent to prison.[38] Some state prison systems have special “youthful offender” facilities that serve some proportion of the youth admitted to prison who are under a certain age (such as under the age of 22 in Pennsylvania).[39] In some states, such as Florida, judges and corrections officials can designate young people as “youthful offenders” for the purposes of admission to these specialized programs; in other states, young people convicted of some serious offenses are sometimes excluded from eligibility.[40] In some states, a portion of young people under age 18 in the prison system are held in the general adult population.

In some states, adult criminal courts have the authority to blend the sentences of young people convicted of crimes such that they begin their sentence in the state system designed to house juveniles, but can be transferred into adult prison in certain circumstances. The federal government, by contrast, makes arrangements to hold all adolescents post-conviction in facilities overseen by the relevant juvenile justice system.[41]

Risks and Harm to Youth in Adult Facilities

Doing time in jails and prisons is hard for anyone. Jails and prisons are often tense and overcrowded facilities in which all prisoners struggle to maintain their self-respect and emotional equilibrium in the face of violence, exploitation, extortion, and lack of privacy; stark limitations on family and community contacts; and few opportunities for meaningful education, work, or other productive activities. But doing time in jail or prison is particularly difficult for young people, who often constitute a very small proportion of the population.

Adult jails and prisons that house adolescents face significant obstacles to keeping adolescents safe and ensuring that they receive developmentally appropriate services—even the limited services that some states mandate by law—when using staff trained and facilities designed to manage adults. Jail and prison recreation yards are designed for adults; doctors and mental health professionals are rarely specialized to treat children. The lack of age-appropriate services and facilities is further compounded by the limited availability of education or rehabilitative programming available in jails and prisons.

Young people held in the same facility as adults face a very high risk of physical or sexual abuse.[42] Studies suggest that adolescents who enter adult prison while they are still below the age of 18 are “five times more likely to be sexually assaulted, twice as likely to be beaten by staff and fifty percent more likely to be attacked with a weapon than minors in juvenile facilities.”[43] Some have argued that the increased exposure of young people to violence in adult facilities may increase the likelihood that they will exhibit violent behavior upon release.[44] While causation is difficult to establish, some data suggests that recidivism rates are significantly higher when young people are held with adults. A report published by the Centers for Disease Control found that “[a]vailable evidence indicates that transfer to the adult criminal justice system typically increases rather than decreases rates of violence among transferred youth.”[45]

II. How Solitary Confinement Harms Youth

Jails and prisons across the United States commonly respond to prison or inmate management challenges by segregating individuals from the general population, often through prolonged physical and social isolation, for hours, days, weeks, or even years. Isolation for 22 hours per day or more, and for one or more days, fits the generally accepted definition of solitary confinement, and this term is used throughout this report.[46]

Solitary confinement is not a practice that jails and prisons restrict to adults; the solitary confinement of young people is not exceptional or transient. On the contrary, it is a serious and widespread problem.

Jail or prison officials frequently subject young people to solitary confinement to achieve one of three goals: to punish young people (this is often called disciplinary segregation); to manage them, either because their classification is deemed to require isolation (often called administrative segregation) or because they are considered particularly vulnerable to abuse (often called protective custody); or to treat inmates, such as after a threatened or attempted suicide (this is often called seclusion).

The conditions that inmates experience in solitary confinement vary little between different forms of segregation, and from county to county, prison to prison, or state to state. [47] The different forms of solitary confinement are discussed in more detail in section III.

Young people repeatedly described their experience in solitary confinement in the most haunting of terms, as in the case of one young woman in Michigan:

I think [the cell] would … look like any other cell. You know, a box. There was a bed—the slab. It was concrete.… There was a stainless steel toilet/sink combo…. The door was solid, without a food slot or window…. It looked like a basement because all I could see was brick walls. There was no window at all … I couldn’t see a clock … the only way I really associated any kind of time—I broke down time: morning, afternoon, evening. I broke it down: breakfast, lunch, and dinner.… [I felt] doomed, like I was being banished … like you have the plague or that you are the worst thing on earth. Like you are set apart [from] everything else. I guess [I wanted to] feel like I was part of the human race—not like some animal.[48]

Another, in Florida, said,

The only thing left to do is go crazy—just sit and talk to the walls.… I catch myself [talking to the walls] every now and again. It’s starting to become a habit because I have nothing else to do. I can’t read a book. I work out and try to make the best of it. But there is no best. Sometimes I go crazy and can’t even control my anger anymore.… I can’t even get [out of solitary confinement] early if I do better, so it is frustrating and I just lose it. Screaming, throwing stuff around.… I feel like I am alone, like no one cares about me—sometimes I feel like, why am I even living?[49]

|

While outside of the scope of this report, public and press reporting suggests facilities in the juvenile justice system also use a range of segregation and isolation practices to detain and manage adolescents, including solitary confinement.[50] Segregation and isolation practices in juvenile facilities are sometimes divided between short-term, immediate sanctions to interrupt what officials deem to be juveniles’ “acting out” behavior and longer-term, administrative or disciplinary isolation. All best practice standards for juvenile facilities propose maximum limits on various forms of isolation that are far below the durations of solitary confinement experienced by young people in adult jails and prisons interviewed by Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union.[51] Yet lengthy solitary confinement still occurs in juvenile facilities. An audit of one California Division of Juvenile Justice facility, completed in 2011, found that of 93 young people placed in restricted housing, 16 were held for a total of 78 days, during which they were only provided an average of 74 out-of-room minutes each day.[52] The segregation and isolation of young people in juvenile facilities, particularly when it constitutes solitary confinement, also raises serious human rights concerns.[53] |

Solitary confinement, and many of the deprivations that are typically associated with it, has a distinct and particularly profound impact on young people, often doing serious damage to their development and psychological and physical well-being. Because of the special vulnerability and needs of adolescents, solitary confinement can be a particularly cruel and harmful practice when applied to them.

While subjected to solitary confinement, young people reported to Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union that they were deprived of a significant level of access to: physical and mental health care services; recreation or physical exercise; education, reading, or writing materials; visits, calls, correspondence, or contact with family members and loved ones; and other rehabilitative and developmentally-appropriate programming. Young people reported very similar experiences regardless of the purpose for which solitary confinement was imposed.

Psychological Harm

The use of solitary confinement risks causing or exacerbating mental disabilities or other serious mental health problems in adolescents.[54]

Studies have found that numerous adults who have no history of mental health problems develop psychological symptoms in solitary confinement.[55] While many of those studies are open to questions about the mental health status of individuals before entering solitary confinement, there is agreement that solitary confinement can cause or exacerbate mental health problems.[56]

Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union are not aware of any studies that look specifically at the effects of prolonged solitary confinement on adolescents. But many experts on child and adolescent psychology said that prolonged isolation, including in conditions as restrictive as solitary confinement, can cause or exacerbate mental disabilities or other serious mental health problems.[57]

Solitary confinement is stressful.[58] It “engender[s] significant levels of anxiety and discomfort.”[59] And young people have fewer psychological resources than adults do to help them manage the stress, anxiety and discomfort they experience in solitary confinement.[60] For many adolescents in prison, developmental immaturity is compounded by mental disabilities and histories of trauma, abuse, and neglect. These factors, though experienced differently by different individuals, can exacerbate the mental health effects of solitary confinement.

Many of the young people interviewed spoke in harrowing detail about struggling with one or more of a range of serious mental health problems during their time in solitary. They talked about thoughts of suicide and self-harm; visual and auditory hallucinations; feelings of depression; acute anxiety; shifting sleep patterns; nightmares and traumatic memories; and uncontrollable anger or rage. Some young people, particularly those who reported having been identified as having a mental disability before entering solitary confinement, struggled more than others. Fifteen young people described cutting or harming themselves or thinking about or attempting suicide one or more times while in solitary confinement.

Not all young people reported experiencing significant mental health problems in solitary confinement. However, these accounts vividly portray the psychological pain and suffering that can be brought on by time in solitary confinement.

Trying to Cope

Many young people described wishing they could mentally escape from solitary confinement, and using a variety of mechanisms to dissociate from their experience. Some developed imaginary friends; some used make-believe or other imaginings to dissociate.

Alyssa E. spent four months in protective solitary confinement when she was sixteen. She said,

It may sound weird but I had a friend in there that I would talk to. She wasn’t there, but it was my mind. And I would talk to her and she would respond.… She [would tell] positive things to me. It was me, my mind, I knew, but it was telling me positive things.… It was a strange experience.[61]

Carter P., who entered prison at 14, described using make-believe and games to help himself through the first of many times he was held in punitive solitary confinement:

I felt like I was going mad. Nothing but a wall to stare at. This was my tenth wall to stare at in my detention. I started to see pictures in the little bumps in the walls. Eventually, I said the hell with it and started acting insane. [I] made little characters with my hands and acted out [video] games I used to play on the out[side]—Dragon Ball Z, Sonic, Zelda—stuff like that. The [corrections officers] would stare at me—looking at me like I’m crazy.… I started talking to myself and answering myself. Talking gibberish. I even made my own language—[corrections officers] didn’t know what I was talking about.[62]

Another common strategy to escape solitary confinement was sleep. Jordan E., who reported spending nearly a year in protective solitary confinement when he was 15, described his focus on trying to sleep:

I daydreamed, I slept a bunch. That’s how I would handle 20, 18 hours a day. If I wasn’t sleeping, I was in bed trying to sleep. Get up, eat, back to bed—lay there and lay there, trying to sleep.[63]

In spite of their best efforts, many felt that in the struggle to cope with solitary confinement, they faced a losing battle with themselves. As Marvin Q., who spent a week in protective solitary confinement when he was 17, described it,

I wish I had better words—I was really, really lonely.… I [would] try to put covers on my head—make … like it’s not there. Try to dissociate myself … I don’t think they should do that to a juvenile. It’s impossible for any person to cope with anything like that. I couldn’t help myself.[64]

Anxiety, Rage, and Insomnia

Young people described a variety of mental health problems associated with their solitary confinement. Some said they had their first anxiety attack in solitary confinement; others said they lost themselves to an uncontrollable rage. Several had trouble sleeping. For some, these problems were all experienced simultaneously. Phillip J., who spent approximately 113 days in solitary confinement (including a single period of 60 days) before his eighteenth birthday, said,

I was stressed. At first I would sleep all day. I would feel myself getting angry or aggressive. I would try to work out or do something, but I was literally going insane in that little spot. The claustrophobia set in and I would feel I was having anxiety attacks and would go over and get water and try and calm down. I would hear the slightest noise and be on guard.[65]

Another young person described mood swings while in solitary confinement. Rafael O. said, “I [would] get depressed, if anything, then have extreme anxiety and feel like I [was] hyper-active, and then get depressed again.”[66]

Parents explained that their loved ones’ struggle was visible during visits (when they were allowed). One woman described visiting her grandchild, whom she identified as having a mental disability, while he was in solitary confinement:

His mind is going and coming when he is locked up by himself all the time.… He is jumpy. He is startled when you talk to him.… He can’t be still—like a nervous person!… He [wa]s always biting on his hands and wrist the whole time I talked to him. Biting his fingers and wrists [and] both hands. He was also grinding his teeth. You can [sic] see his jaw constantly moving. He never did that before.[67]

Some youth experienced anger or rage that they could not control. As one said, “All I would want to do is fight.”[68] Another said, “I couldn’t sleep. I was having anger. My anger was crazy. I was having outbursts.”[69] And a third said, “It makes you worse. It really brings the beast out of you to be in there stressing. You start saying, ‘Fuck everything.’ … [It] makes you more wild; makes you feel like a lion in a cage.”[70] Kyle B. wrote,

The loneliness made me depressed and the depression caused me to be angry [sic], leading to a desire to displace the agony by hurting others. I felt an inner pain not of this world.… I allowed the pain that was inflicted upon [me] from [my] isolation placement build up while in isolation. And at the first opportunity of release (whether I was being released from isolation or receiving a cell-mate) I erupted like a volcano, directing violent forces at anyone in my path.[71]

|

Adolescents who had trouble coping or sleeping were sometimes identified by mental health staff and prescribed medication. A number of young people described being prescribed sleeping medication. Mason P., who had spent the four days before he was interviewed in administrative solitary confinement, said, I don’t sleep. They gave me sleeping pills ‘cause I can’t sleep. I worry a lot.... I started taking them three days ago. They asked if I felt like killing myself or hurting somebody, I said, “Naw,” but they told me if I was worrying they said they were going to give me something.[72] A Philadelphia County Prison Official observed that many youth held in solitary confinement in the county jail were prescribed sleeping aids and other prescription medications while in isolation: “It was a way [for them] to cope and reduce anxiety.”[73] But some experts question the practice of treating sleep problems directly. Dr. Cheryl Wills, a child psychiatrist who has diagnosed youth in juvenile and adult facilities, argues that poor sleep patterns are often indicative of another underlying problem: I am not a proponent of medicating sleep … the question is, what is it related to—a symptom of depression? Post-traumatic stress? ADHD? So you figure out what is going on and treat sleep as a part of the picture.… There are medications that help youth if they have issues, but you must treat it as a whole package, as part of a treatable diagnosis.… You don’t want to medicate a youth unless he or she really needs it.[74] Treating sleeplessness associated with mental health problems or disabilities is particularly complicated when those problems may themselves be caused or exacerbated by being held in solitary confinement. |

Being alone with their thoughts, and especially thoughts of home, made it difficult for them to sleep:

I don’t even want to sleep here because I can’t wait till I get home. Every night before I go to sleep I think about home and can’t sleep. I’m up until at least 5 a.m. which causes other outbursts because I’m just thinking.[75]

Inability to sleep can itself cause or exacerbate other mental health problems, and can also indicate an underlying mental disability.

Cutting and Self-Harm

In addition to the psychological pain and suffering that young people reported experiencing while in solitary confinement, some young people reported that they cut or otherwise physically harmed themselves. Among youth in jails and prisons, evidence suggests that this problem affects girls at an even higher rate than boys.[76] We found both young men and young women who reported harming themselves in solitary confinement. Melanie H., who spent three months in protective solitary confinement when she was fifteen years old, described how cutting helped her cope with feelings of loss she experienced when alone with her thoughts:

I became a cutter [in solitary confinement]. I like to take staples and carve letters and stuff in my arm. Each letter means something to me. It is something I had lost. Like the first one was a [letter], which is the first letter in my mother’s name. And every day I would apologize to her. I don’t know—I felt like I had a burden I couldn’t carry and it made me feel good.[77]

Other young women described using self-harm as a way to call for help or get the attention of officials. Alyssa E. said,

Me? I cut myself. I started doing it because it is the only release of my pain. I’d see the blood and I’d be happy.… I did it with staples, not razors. When I see the blood and it makes me want to keep going. I showed the officers and they didn’t do anything.… I wanted [the staff] to talk to me. I wanted them to understand what was going on with me.[78]

Psychological experts with experience monitoring health care in adult and juvenile facilities described self-harm as a typical reaction to isolation and an effort to force interaction with others. One psychological expert said,

I think the biggest detriment [in solitary confinement] is lack of interaction. So typically youth become desperate for any interaction. So you see the incidents of self-harm increase. They find ways to hurt themselves or hurt somebody else. Because it is more difficult to withstand longer periods of isolation than an adult … they are going to find ways to hurt themselves or somebody else or cause problems.[79]

Suicidal Thoughts and Attempts: “The death-oriented side of life”

Twelve young people told Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union in detail about times that they thought about or attempted suicide while in solitary confinement. Experts with experience advising jails and prisons on suicide prevention argue that it is uncontroversial that suicide and solitary confinement are correlated:

[N]o one disagrees that the suicide rate is higher for youth in both juvenile facilities, adult jails, and adult prisons.… I think it is safe to say that youth in an adult jail and prison are at higher risk for suicide and youth in isolation in those facilities would also be at higher risk.[80]

Paul K., who spent 60 days in protective solitary confinement when he was 14, described how he came to want to end his life:

The hardest thing about isolation is that you are trapped in such a small room by yourself. There is nothing to do so you start talking to yourself and getting lost in your own little world. It is crushing. You get depressed and wonder if it is even worth living. Your thoughts turn over to the more death-oriented side of life.… I want[ed] to kill myself.[81]

Twelve young people told Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union about having either thought about or attempted suicide while in solitary confinement; some had attempted suicide before they were in jail or prison; some described witnessing attempted or successful suicides. Luz M. said suicidal thoughts came immediately after she went into solitary confinement:

I just felt I wanted to die, like there was no way out—I was stressed out. I hung up [tried to hang myself] the first day. I took a sheet and tied it to my light and they came around.… The officer, when she was doing rounds, found me. She was banging on the window: “Are you alive? Are you alive?” I could hear her, but I felt like I was going to die. I couldn’t breathe.[82]

Some young people have committed suicide while in solitary confinement.[83] According to a national expert on suicides in juvenile facilities, jails, and prisons, the evidence suggests that most suicides in juvenile (not adult) facilities occur while youth are confined alone to their room.[84]

Struggling with Mental Disabilities and Past Trauma

Many adolescents face the additional challenge of coping with a mental disability while in solitary confinement.[85]

Studies suggest that youth under age 18 enter the adult criminal justice system with high rates of mental disabilities.[86] Approximately 48 percent of adolescents between the ages of 16 and 18 in New York City Department of Corrections custody in FY2012, for example, had a diagnosed mental disability.[87] But some mental disabilities do not manifest until youth reach their teen years.[88]

Some young people in solitary confinement likely struggle to cope simultaneously with the psychological vulnerabilities associated with their developing brains and the onset of mental disabilities, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. As one expert, Dr. Cheryl Wills, a child psychiatrist with experience diagnosing youth in juvenile and adult facilities, described,

Sometimes youth will have psychosis in flashes. It will come out in the stress of being in [isolation] but not with other youth. I have personally seen youth who were not psychotic and you put them in [isolation] and they are psychotic. Was it going to happen? Yes. Did it happen faster in [isolation]? Possibly.[89]

It is not often possible for young people themselves or corrections professionals to identify adolescents with mental disabilities before they are subjected to solitary confinement because some serious mental disabilities do not manifest until late adolescence.[90] Some of the young people interviewed by Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union had been identified as having a mental disability at an early age. Others reported experiencing various mental health problems throughout their youth and while in solitary confinement, without having been identified as having a mental disability. Some experienced mental health problems and were identified as having a mental disability for the first time during or after a period of solitary confinement.

Landon A., who struggled with auditory and visual hallucinations before going to jail, described his experience in solitary confinement: “I would hear stuff. When no one was around it was harder to control. When I was by myself, I would hear stuff and see stuff more.”[91] He said he was usually awake between 10 p.m. and 3 a.m., trying to manage the hallucinations. “I hear the most stuff at night,” he said, “so it’s the hardest time to sleep.”

Young people with mental disabilities interviewed by Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union repeatedly described the pain and suffering associated with attempting—and failing—to cope with the mental health problems they experienced in solitary confinement. Asked about struggling into the night with his hallucinations, Landon A. said solitary confinement is “not a place that you want to go. It’s like mind torture.”[92]

Some also reported that solitary confinement triggered memories of past trauma, making it yet more difficult to cope with the experience. Youth in the criminal justice system have histories of trauma and abuse at much higher rates than the general population.[93] And there is significant evidence to suggest that girls enter the criminal justice system having suffered physical or sexual abuse at much higher rates than boys, and therefore struggle disproportionately with past trauma.[94] Melanie H., for example, was held in protective solitary confinement for three months when she was 15 years old. She said, “When I was eleven, I was raped. And it happened [again] in 2008 and 2009.”[95] When she was isolated, the memories came back: “I was so upset … and a lot was surfacing from my past.… I don’t like …feeling alone. That’s a feeling I try to stay away from. I hate that feeling.”[96]

As one defense attorney opined,

If you isolate a kid [for whom] isolation was a form of child abuse, the jail doesn’t know how to deal [with that]. I have represented clients who have locked [their] kids in a closet and go[ne] out all night long—closets are cheap baby sitters. [I] don’t think anyone explores those issues with those kids—there is no difference in protocols, no accommodation [of past trauma].[97]

Thirty-five interviewees spent more than one period in solitary confinement before they turned 18. This repeated isolation, according to experts, “leaves [youth] with a potential for a post-traumatic reaction.”[98] Phillip J., for example, who was first held in solitary confinement for 36 days when he was 16, described how isolation itself became a trigger for traumatic memories of solitary confinement:

Once you are confined the way I was, then any other confinement just triggers that experience—loss of sleep, all these different flashbacks of different bad events. You try to harness it, but you don’t know how or what’s going on or what’s happening.[99]

Barriers to Accessing Care

Young people in solitary confinement do not get the help they need to cope or adequate access to treatment for mental health problems, whether preexisting or newly developed. Because of this lack of adequate care or access, their suffering can be worse than it may otherwise have been.

Human Rights Watch has elsewhere documented the widespread failures of state prison systems to provide access to care for adults experiencing mental health problems, including those with mental disabilities.[100] On the contrary, prison systems sometimes react to prisoners experiencing a crisis by punishing them. Isaiah O., who entered jail at 17, told us,

Sometimes, when I cut, having a razor or using it against myself, they would give me a [disciplinary violation] for making the room unsanitary or, two, for having a weapon.… It felt like I was going against myself and they was [sic] going against me. That’s when I started going crazy. I mean, I felt with the depression and them going against me, that’s when I started catching assaults. I guess I was fighting two wars—myself and then the officers.[101]

While some young people, like Isaiah O., described being punished for conduct related to mental health problems, others reported being diverted from one form of solitary confinement to another to protect them from self-harm.[102]

In some facilities, young people felt that the only way to get mental health care was through self-harm:

Sometimes you have to [cut yourself] to go to [medical solitary confinement for suicide watch]… get psychological attention … because if you have a psychological emergency or you need to talk to somebody they won’t let you. [So I] cut myself on my arm … [when] I be thinking in my head I need to talk to somebody before I do something I don’t want to do.[103]

A few young people described corrections staff telling them that they did not believe their cries for help or their requests for mental health care. An extremely complicated and toxic atmosphere can develop when corrections staff feel they need to be gatekeepers to mental healthcare. It is too easy for overworked and under-resourced medical and corrections staff to dismiss as malingering a cry for help. Indeed, some may exaggerate their symptoms precisely because the solitary confinement is unbearable.

But, as one expert psychiatrist who evaluates mental healthcare in detention, Dr. Cheryl Wills, said, mental health crises must be taken seriously:

[Youth] need to be taken seriously whether or not they are malingering. I have heard youth and adults say that [staff told them] that if they were going to do it [kill themselves], don’t do it on that staff member’s shift. The security staff is not expert in suicide risk assessment and some malingerers also are mentally ill. The psychiatric interview includes an assessment of suicide risk that is used to formulate a treatment plan. All threats of suicide should be assessed, especially in incarcerated individuals who lack the flexibility to leave the facility and to seek mental health services at a local emergency room.[104]

Physical Harm

Solitary confinement, and practices associated with it, can cause serious physical harm to youth.

Young people held in adult jails and prisons are frequently far from full-grown. Many of the young people we interviewed entered jail or prison inches and pounds away from adulthood. One young man described being unable to fit in his orange jumpsuit: “I believe I was 5’4” or 5’5” … I weighed maybe 140 … in [solitary confinement] they gave you the [orange uniform]. It was too big for me. It kept falling off my waist and everything.”[105]

Jails and prisons are rarely equipped to appropriately manage or provide for those who are physically immature. Our research showed that solitary confinement in adult facilities resulted in a deprivation of exercise and adequate nutrition.

Lack of Adequate Exercise

One of the defining experiences for youth held in solitary confinement in many facilities is the hour out: one hour, each day, during which adolescents are permitted, whether in a hallway, dayroom, or metal cage, to walk around or exercise. Some facilities allow a few minutes more or less than an hour, but an hour out is standard practice. However, Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union found that few facilities actually provide for or encourage physical exercise for youth in solitary confinement. Of the 77 young people we interviewed on their experience in solitary confinement, 15 reported spending at least one period in solitary confinement during which they were allowed no recreation at all. Young people in Florida prisons, for example, reported being denied recreation for the first thirty days spent in disciplinary solitary confinement, pursuant to Department of Corrections (DOC) policy.[106]

Even when held in facilities that allowed outdoor recreation, some adolescents in solitary confinement reported that they were not always able to exercise. Jacob L. described having to wake, without a clock or alarm, to ask to go to recreation:

You go to rec[reation] for an hour, but you have to be up at six in the morning to catch the yard. Before they serve breakfast—you got to catch them before breakfast and [then] they take you after breakfast. So if you don’t know how to wake up, you can’t go outside. That’s supposed to be mandatory [but] they don’t ask you—you have to tell them.[107]

Due to reduced staffing on weekends, some facilities only offer recreation during the week.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the US Department of Health and Human Services both recommend that youth between the ages of six and seventeen engage in one hour or more of physical activity each day.[108] Both agencies recommend that youth regularly do a combination of activities, including vigorous aerobic activity, like running, at least three days a week; muscle-strengthening activity, such as gymnastics, at least three days a week; and bone-strengthening activity, such as jumping rope, at least three days a week.[109]

Most young people who did get to exercise outdoors, like Jacob L., did so in a small, individual, fenced-in cage, often barely larger than their cell. Almost all young people spent their out-of-cell time alone. It is hard to imagine that these conditions would permit adequate aerobic or muscle-strengthening exercise, let alone an adequate contrast from time in one’s cell.

Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union did not interview any young people who described a jail or prison recreation regime that ensured or encouraged strenuous aerobic physical activity. Many young people described working out in their cells to cope with their time in confinement. Jason L. described pacing his cell until he was exhausted:

I kind of talked myself through it. Pace[d] the room. I learned that walking and talking takes you outside. So I would walk and talk for about the first four days until I was dead tired, then sleep for about three and do it over.[110]

Physical Changes and Stunted Growth

Youth who are physically growing and changing need age-appropriate attention and care. Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union found that young people in solitary confinement are sometimes denied access to this care in facilities that provide it, and are denied it altogether in those that do not. A number of young people reported going to sleep hungry night after night. Some told Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union that they experienced (or witnessed in other adolescents) other physical changes as a result of the stress of solitary confinement, such as hair or weight loss.

Several facilities reported that there are no differences between the physical health and dental services available for youth and adults.[111] As one facility reported, “[A youth is] treated as an adult for medical, dental, mental health issues.”[112]

Inadequate Nutrition

One of the most common complaints of young people held in solitary confinement was that the food and meal schedule were nutritionally inadequate, and that they were denied the opportunity to supplement their nutrition by purchasing food items from the facility’s commissary or canteen. Some young people described losing weight as a result.

Caroline I., who spent approximately 41 days in punitive solitary confinement while she was under 18, said, “They only give you a little food, so that’s hard. You lose weight…. I went in 150 and came out 132. That’s more than 15 pounds!”[113] A grandmother who visited her grandson in solitary confinement observed that he “definitely lost weight—he’s so little [now].” She estimated that he lost 15-20 pounds after he entered solitary confinement.[114]

Some young people said that, during their time in punitive solitary confinement, their diet was changed to a baked nutritional loaf as a form of additional punishment. Others described being fed a diet that consisted mostly of beans and processed foods.

The US Department of Agriculture and the National Institutes of Health both recommend a balanced diet of nutrient-dense foods, including vegetables, fruits, and whole grains.[115] While the overall nutritional needs of youth and adults are similar in regards to caloric intake, youth physical development, including bone development, requires additional amounts of some nutrients to ensure healthy growth.[116]

Other Physical Effects

Young people interviewed by Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union described experiencing other physical changes in solitary confinement. One young person reported, “I saw a guy who lost his hair in [solitary confinement]. He wasn’t like that before he got locked up.”[117]

One female interviewee described that, during the months she was in solitary confinement, she stopped menstruating. She recalled that she didn’t start again until after she was transferred out of solitary confinement and to a juvenile facility:

You know it is funny to say. I know I was having periods at that time of my life. But I don’t have any memories of having one at the jail. I remember I went through a long period of time at the juvenile facility where I didn’t have them. That was right when I came back [from jail]. I knew it was a number of months because for a long time I was wondering why I wasn’t having them. I remember because most women complain about them but when I got mine again I was glad. It made me feel human—or at least functioning the way things were supposed to be.[118]

Studies have linked changes in menstruation to stress and trauma.[119]

Social and Developmental Harm

Young people in solitary confinement are frequently deprived of contact with their families and their own children, access to education, and to programming or services necessary for their growth, development, and rehabilitation.

Denial of Family Contact

Limitations on family visits are a common feature of all forms of solitary confinement. Many facilities deny adolescents contact with their families while they are in solitary confinement. For some, this means no visits, no phone calls, and no letters. Facilities often view these things as privileges that young people in solitary confinement can be denied as a result of their classification, or to punish them.

Twenty-one teenagers told us they were denied the ability to visit with loved ones during a period of solitary confinement. Nineteen spent at least one period in solitary confinement during which they were only allowed to visit with loved ones while in a cage, behind glass, or by video-conference. Eleven spent at least one period in solitary confinement during which they were not allowed to write letters to loved ones, having been denied access to pen or pencil and paper.

For some young people, family is the only thing that gives them hope:

I catch myself in the moment, attempting [suicide]. But then I think about my family and everyone on the outs[ide] and I think, if I chose to do that, I can never come home. I think if it weren’t for my family, I would have chosen to commit suicide.[120]

Jeffrey J., whom Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union interviewed in administrative solitary confinement while he was awaiting a disciplinary hearing, feared losing contact if placed in punitive solitary confinement:

I hope they don’t take my visits or call away. Today is going to make the third day I haven’t got a call.... My mom really, really cares about me so she wants to know what is going on.... As long as I can talk to my family, I’ll be okay. I could be in a room all day if I could talk to my family.[121]

In some facilities, young people were allowed visits when in solitary confinement, but denied physical contact with their family members, forced to talk through glass or a metal screen. For some, this was as painful as solitary itself: “The hardest part is being behind glass when your family visits and you can’t hold your family.”[122] Young people cited the denial of hugs and kisses as a source of pain and suffering. Another teenager said, “It was very depressing not to be able to give them a hug. I would cry about that.”[123] Again and again, young people stressed the importance of physical touch. One young woman said, “[Visits] behind glass … [were] torture—I couldn’t touch my family.”[124] A few young parents reported that they were also prevented from receiving visits from their own children while in solitary confinement.

Denial of Adequate Education

Young people in solitary confinement, including adolescents with intellectual disabilities, commonly reported being denied access to adequate education. Youth in some facilities were regularly provided with a packet of educational materials for in-cell self-study, but often their completed work went ungraded and their questions unanswered.

For some jails and prisons, access to education ends the moment the solitary confinement cell door slams shut, regardless of the age of the inmate inside.[125] As Darrell E., who spent approximately 20 days in protective solitary confinement in jail when he was 15, stated bluntly, “No, there was no school for inmates in isolation and there were no exceptions for me.”[126]

Only 31 young people reported receiving educational programming of any type during a period of solitary confinement. Fourteen young people reported spending a period of time in solitary confinement during which they were provided only with a packet of materials to complete in their cell. Twenty-five young people reported spending a period of time in solitary confinement during which they were not provided any educational programming at all; sixteen described spending periods of time in solitary confinement without even a book or magazine to read.

In a few states, education in jails is provided in consultation (or even directly by) state or local departments of education (or school boards). In some of these jurisdictions, the law only provides for limited education, such as four hours per week in Colorado, and allows security exceptions that are applied to youth in solitary confinement.[127] In other jurisdictions, youth in solitary confinement are taught through “cell study,” packets of materials dropped off at their cells.[128] Some young people reported eagerly—and quickly—completing any work packets provided by jails or prisons. Others said they refused to study in their cells. Jeremiah I. said,

If you are enrolled in school, they slide a packet under your door. I don’t do it. I don’t feel like doing work in my cell. If they would take me to school I would do it, but … they just keep giving you work.[129]

Some facilities take no further steps after an adolescent, like Jeremiah, refuses education. Sometimes, those who received cell-study materials were able to consult with a teacher. However, usually this was either through the cell door or by phone. One young woman described how “the officer who does cell-study asks if you have anything and want to talk to your teacher and then you talk on the phone.”[130] Some young people reported interrupted or infrequent contacts with educators.

As discussed above, a number of young people reported experiencing serious mental health problems in solitary confinement. Some of those young people described diminished reasoning and learning abilities as a result of solitary confinement. Jordan E. described feeling mentally slower after solitary confinement:

[Solitary confinement] absolutely slowed down my thinking skills. I would come out of [solitary] and be demonstrably slower. Following conversations, doing math work, my brain slowed down quite a bit. I was far more depressed. There were no real mental health services [in the jail].[131]

Struggling with Intellectual Disabilities

While adult facilities, especially jails, struggle to provide any educational programming for youth, specialized programming for youth with intellectual disabilities is even rarer.[132]

Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union interviewed 11 young people who reported that before entering jail or prison they had either been taught in special classes, having been identified as having a learning disability, or had an individual education plan.[133] Some facilities are unable to identify adolescents with intellectual disabilities, relying on records provided by parents or schools in the community. One prison official reported,

We are not allowed to identify [learning disabilities]. As a department, we don’t identify those types of issues. If we get an individual and we think they might be [in need of] special education—if a parent has paperwork—we can do that process. But as far as someone coming in off the street? If we don’t have paperwork, we can’t do that.[134]

The provision of educational programming to young people with intellectual disabilities can also be complicated by the checkered educational history of many adolescents, even though they may never have been identified as having an intellectual disability.

|

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is a federal law that governs the provision of appropriate special education and related services for youth with disabilities. IDEA was signed into law in 1990 and was significantly amended in 2004. All states receive IDEA funds and are therefore subject to its provisions.[135] IDEA requires the provision of a free and appropriate public education to youth with disabilities, in the least restrictive environment, according to their individual needs through age 21.[136] In defining the “least restrictive environment,” IDEA states, To the maximum extent possible, children with disabilities, including children in public or private institutions or other care facilities, are educated with children who are not disabled, and special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular educational environment [emphasis added] occurs only when the nature or severity of the disability of a child is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily.[137] With regard to detention facilities, IDEA states that governors or other appropriate state officials may assign to any public agency in their state the responsibility of ensuring that particular requirements are met with respect to youth with disabilities who are convicted as adults and are incarcerated in adult prisons. [138] But state law exemptions for adult facilities leave many adolescents with disabilities without the basic educational guarantees set forth in IDEA. Florida, for example, allows for young people with disabilities who are convicted as adults and incarcerated in adult prisons to be exempted from certain IDEA provisions regarding assessment and transition planning. [139] In addition, for young people with disabilities in Florida’s adult prisons, the team devoted to a student’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) may modify that youth’s program or placement based on certain security or penal interests beyond the restrictions set forth in IDEA. [140] Youth with disabilities in solitary confinement are often prevented from receiving proper educational services, such as basic out-of-cell instruction. |

Failure to Provide for Rehabilitation or Social Development

Some of the deprivations that young people confront in solitary confinement differ little from the normal conditions of incarceration. Jails and prisons spend few resources on programming or services, with jails spending even fewer resources than prisons. Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union found that it was exceedingly rare that facilities provided programming or services aimed at rehabilitation or social development to young people under age 18 in solitary confinement. While this is a problem for adolescents in adult facilities generally, the problem is acute for those in solitary confinement. Youth enter jails and prisons—and solitary confinement—in the midst of a transition to adulthood.

As one expert with experience in juvenile and adult facilities told Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union,

We are raising these kids. We need to teach them.… What we are doing is putting young men [and women] who are forming their identity in a situation where they are learning to do things—not in a good way.… So if we are going to send young men [and women] to prison, we need truly specialized units where they can learn and grow. Because I think we all want them to be better off when they come out. The other thing they need is skills that will help them on the outside.[141]