Glossary

Boko Haram: The name commonly used by Nigerian and foreign media to refer to the militant Islamic group. Boko in Hausa means “Western education” or “Western influence” and haram in Arabic means “sinful” or “forbidden.”

Hausa: The lingua franca of northern Nigeria.

Jama’atu Ahlus-Sunnah Lidda’Awati Wal Jihad: The formal name for Boko Haram and the name the group prefers to use when referring to itself. It means “People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad.”

Joint Military Task Force (JTF): Hybrid government security forces, primarily comprised of military, police, and State Security Service personnel, deployed to various northern Nigerian states to respond to the Boko Haram violence.

Naira: Nigeria’s currency, with an approximate value of 160 naira to 1 US dollar in this report.

Police Mobile Force (MOPOL): Nigeria’s anti-riot police, commonly dressed in black and green uniforms.

Sharia: Religious legal, civic, and social code in Islam based on the Quran, sayings of the Prophet Mohammed, and judgments of Islamic scholars.

State Security Service (SSS): Nigeria’s secret police and its internal intelligence agency.

Summary

Since July 2009, suspected members of Boko Haram, an armed Islamic group, have killed at least 1,500 people in northern and central Nigeria. The group, whose professed aim is to rid the country of its corrupt and abusive government and institute what it describes as religious purity, has committed horrific crimes against Nigeria’s citizens.

Boko Haram’s attacks—centered in the north—have primarily targeted police and other government security agents, Christians worshiping in church, and Muslims who the group accuses of having cooperated with the government. Boko Haram has carried out numerous gun attacks and bombings, in some cases using suicide bombers, on a wide array of venues including police stations, military facilities, churches, schools, beer halls, newspaper offices, and the United Nations building in the capital, Abuja. In addition to these attacks, the group has forced Christian men to convert to Islam on pain of death and has assassinated Muslim clerics and traditional leaders in the north for allegedly speaking out against its tactics or for cooperating with authorities to identify group members. Following Boko Haram attacks on Christians this year, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay said that the attacks may constitute crimes against humanity if judged to be deliberate acts leading to population “cleansing” based on religion or ethnicity.

Nigeria’s government has responded with a heavy hand to Boko Haram’s violence. In the name of ending the group’s threat to citizens, security forces comprising military, police, and intelligence personnel, known as the Joint Military Task Force (JTF), have killed hundreds of Boko Haram suspects and random members of communities where attacks have occurred. According to witnesses, the JTF has engaged in excessive use of force, physical abuse, secret detentions, extortion, burning of houses, stealing money during raids, and extrajudicial killings of suspects. These killings, and clashes with the group, have raised the death toll of those killed by Boko Haram or security forces to more than 2,800 people since 2009.

This report is based on three trips to Nigeria between July 2010 and 2012 and continuous monitoring of media report of Boko Haram attacks and statements. It explores the crimes committed by the Islamist group and also exposes and sheds light on the underreported role of Nigeria’s government, whose actions in response to the violence have contravened international human rights standards and fueled further attacks. Human Rights Watch’s research suggests that crimes against humanity may have been committed both by state agents and members of Boko Haram.

On December 31, 2011—after a series of Boko Haram bombings across northern Nigeria—President Goodluck Jonathan declared a state of emergency, which suspended constitutional guarantees in 15 areas of 4 northern states. The state of emergency, which remained in effect for six months, did not ameliorate insecurity. Nor did regulations issued in April 2012 that detailed emergency powers granted to security forces to combat the Boko Haram threat. The group carried out more attacks and killed more people during this six-month period than in all of 2010 and 2011 combined. Nigeria has kept Boko Haram suspects in detention often incommunicado without charge or trial for months or even years and has failed to register arrests or inform relatives about the whereabouts of detainees. In the northern cities of Maiduguri and Kano, for example, Human Rights Watch found that the authorities no longer even bring formal charges against Boko Haram suspects. The fate of many of these individuals after their arrest remains unclear.

Civil society activists in Nigeria say that ordinary citizens fear both Boko Haram and the JTF, whose abusive tactics at times strengthen the Islamist group’s narrative that it is battling government brutality. Indeed, the police’s extrajudicial execution of Boko Haram’s leader, Mohammed Yusuf, and dozens of other suspected members in July 2009 became a rallying cry for the group’s subsequent violent campaign. In addition, civil society activists said that because community members themselves are subjected to JTF abuses they are often unwilling to cooperate with security personnel and provide information about Boko Haram, which impedes effective responses to the group’s attacks.

A complex mixture of economic, social, and political factors had provided a fertile environment for Boko Haram. These include endemic corruption, poverty (which is more severe in large parts of the north than in other parts of the country), and impunity for violence, including horrific inter-communal killings and human rights abuses by security forces. These deeply entrenched problems cannot be easily resolved. Nonetheless, all parties should respect international human rights standards and halt the downward spiral of violence that terrorizes residents in northern and central Nigeria.

The group’s new leader, Abubakar Shekau, took over after Yusuf’s death in July 2009, but since then the group has gone underground leading to much speculation about the composition of the group’s leadership and organizational structure, and possible factions, sponsors, and links with foreign groups, such as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). While some analysts believe the group is divided into factions, others argue that Boko Haram has evolved into a cell-based organization that remains unified under Shekau’s control. Complicating the matter are criminal gangs in the north, including political thugs, that are suspected of committing crimes under the guise of Boko Haram. Despite Boko Haram’s clandestine nature, the largely consistent pattern of attacks documented in this report suggests a degree of coordination or organizational control within the group.

Although Boko Haram is a non-state actor and is not party to international human rights treaties, it has a responsibility to respect the lives, property, and liberties of Nigerians. The group should immediately cease all attacks on Nigeria’s citizens, including attacks on the right to freedom of expression and religion, such as assaults on media and churches, and attacks on schools that undermine children’s right to education.

For its part, Nigeria’s government has a responsibility to protect its citizens from violence, but also to respect international human rights law related to the use of force by its security forces, treatment of detainees, prohibition of torture, and the obligation to hold speedy and open trials. These rights are guaranteed by various international treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which Nigeria has ratified. Nigerian authorities should also prosecute the perpetrators of crimes, by either Boko Haram or government security forces—something they have so far largely failed to do.

Nigeria’s international partners, including the United States and United Kingdom, have expressed concern about the intensifying violence in Nigeria, human rights violations, and government failures to address the underlying causes of the violence. They should continue to press Nigeria’s government to protect human rights, increase security for citizens at risk of further attacks, rein in abusive security forces, bring to justice the perpetrators of violence, and meaningfully address corruption, poverty, and other factors that have created a fertile ground for violent militancy.

In 2010 the situation in Nigeria was placed under preliminary examination by the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC)—to which Nigeria became a party in 2001. In July 2012 the ICC prosecutor visited Nigeria. The ICC should continue to monitor Nigeria’s efforts to hold perpetrators to account and press the government, consistent with its obligations under the Rome Statute and the principle of complementarity, to ensure that individuals implicated in serious crimes in violation of international law, including crimes against humanity, are thoroughly investigated and prosecuted.

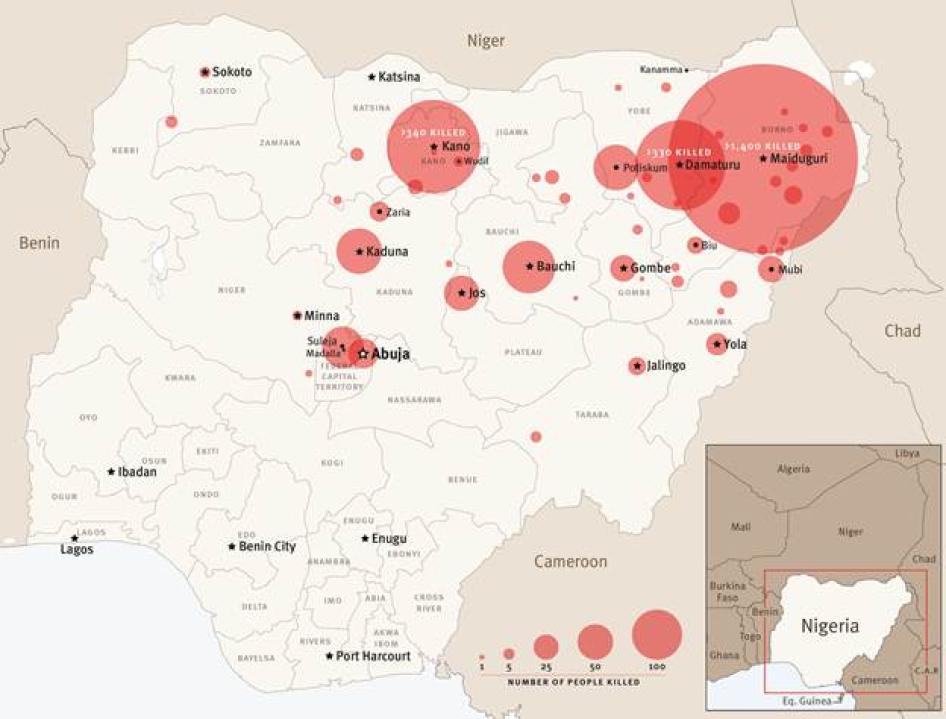

Estimated Number of People Killed by Boko Haram or Government Security Forces in Nigeria Between July 2009 and September 2012

Estimated death toll based on Human Rights Watch monitoring of Nigerian and foreign media reports. © 2012 John Emerson/Human Rights Watch.

Recommendations

To the Government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria

- Provide additional security personnel to protect vulnerable communities, including Christian minorities in the north and Muslims, among them clerics and traditional rulers, who oppose Boko Haram.

- Ensure that prompt and thorough investigations are conducted into allegations of arbitrary detention, use of torture, enforced disappearances, and deaths in custody. Ensure that the relevant authorities prosecute without delay and according to international fair trial standards all security force personnel implicated in any of these abuses.

- Repeal or reform portions of the Terrorism (Prevention) Act that contravene international human rights and due process standards, including the designation and banning of organizations as terrorist groups without providing judicial appeal, and the power to detain suspects for prolonged periods without formal charge.

- Enact legislation to domesticate the International Criminal Court’s Rome Statute, which Nigeria ratified in 2001, including criminalizing under Nigerian law genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, consistent with Rome Statute definitions.

- Enact legislation that criminalizes torture under domestic law according to international standards, including the Convention against Torture.

- Protect the due process rights of all detainees.

- Compile, maintain, and make available to those who need it, including detention center inspectors and family members, a list of detention facilities and detainees in custody.

- Immediately permit access to lawyers for detainees.

- Provide immediate and unhindered access for independent monitors to all detention facilities without prior notification.

- Bring detained suspects promptly to a public civilian court and ensure that they are either charged with a recognizable crime or released.

- Immediately order security forces to stop all harassment and abuse of citizens and the destruction of property, in line with domestic law and international human rights standards.

- Ensure, consistent with Nigeria’s obligations under the Rome Statute and the principle of complementarity, that prompt and thorough investigations are conducted into allegations of serious crimes committed by government security personnel in violation of international law, including extrajudicial killings, physical abuse, stealing of property, and burning of homes, shops, and vehicles. Ensure that relevant authorities prosecute without delay and according to international fair trial standards anyone implicated in these abuses.

- Ensure, consistent with Nigeria’s obligations under the Rome Statute and the principle of complementarity, that relevant authorities prosecute without delay and according to international fair trial standards all Boko Haram suspects implicated in serious crimes committed in violation of international law, including crimes against humanity.

- Enact a robust witness protection program for Nigerians who denounce Boko Haram attacks or security force abuses.

- Provide additional protection to schools at risk of attack and take steps

to mitigate the impact of attacks on children’s right to education.

- Prepare in advance a rapid response system so that when attacks on schools occur, schools are quickly repaired or rebuilt, and destroyed education material replaced. Ensure that during construction students receive delivery of education at alternative locations and, where appropriate, psychosocial support.

- Designate a senior official in each state affected by Boko Haram attacks on schools to implement and oversee monitoring of the rapid response system to ensure immediate repair and rebuilding of schools damaged in attacks.

- Take urgent measures to address factors that give rise to militancy in

Nigeria.

- Ensure that the progressive realization of the right to health and education is recognized and implemented for all Nigerians, without discrimination, including through budget allocations.

- Renew efforts to tackle endemic government corruption by increasing the independence of Nigeria’s leading anti-corruption agency, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, through greater security of tenure for its chairperson; strengthening the capacity of overburdened federal courts by improving institutional and infrastructural support to the judiciary; and ensuring that all government officials, including police personnel, implicated in corruption are investigated and prosecuted without delay and according to international fair trial standards.

- Ensure that relevant authorities investigate and prosecute without delay those responsible for inter-communal violence, including for ethnic and sectarian killings in Kaduna and Plateau states; and enact legislation to end divisive state and local government policies that discriminate against “non-indigenes,” people who cannot trace their ancestry to the original inhabitants of an area.

To the Nigerian Military

- Fully investigate reports of human rights abuses committed by soldiers.

- Suspend military personnel against whom there are credible allegations of human rights abuses, pending investigations.

- Refer military suspects of human rights abuses to the civilian courts for criminal investigation. Fully cooperate with any criminal investigation into the conduct of military personnel.

- Establish effective channels for residents to report incidents of abuse carried out by military personnel, and ensure that each is followed up with a transparent and credible investigation.

To Boko Haram

- Immediately cease all attacks, and threats of attacks, that cause loss of life, injury, and destruction of property.

- Take all necessary steps to comply with the principles of international human rights law.

- Cease all attacks on the right to freedom of expression and religion, such as assaults on media and churches.

- Cease all attacks on schools or threats that undermine children’s right to education.

- Comply with international standards to refrain from incitement to acts of violence.

To Nigeria’s International Partners, including the United States and United Kingdom

- Seize every opportunity to press Nigeria to fulfill its obligations under international law regarding torture, treatment of detainees, and due process guarantees.

- Press Nigeria about reports of excessive use of force and extra-legal activity among Nigerian security forces and the importance of protecting human rights.

- Condition future aid to Nigerian security forces on clear improvements in respect for human rights and on meaningful progress in holding accountable security force personnel implicated in abuses against Nigerian citizens.

- Assist Nigeria’s government in creating a witness protection program and in training security and justice-sector personnel to ensure compliance with international due process standards.

To the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States

- Press Nigeria to fulfill its obligations under international and regional conventions regarding torture, treatment of detainees, and due process guarantees.

- Press Nigeria to thoroughly investigate and prosecute without delay and according to international fair trial standards all members of Boko Haram and government security forces implicated in acts of violence and abuse.

To the International Criminal Court

- Continue to assess whether crimes committed in Nigeria constitute crimes under the ICC’s jurisdiction, and monitor the government’s efforts to hold perpetrators to account, including through periodic visits to Nigeria.

- Continue to press Nigeria, consistent with its obligations under the Rome Statute and the principle of complementarity, to ensure that individuals implicated in serious crimes committed in violation of international law, including crimes against humanity, are investigated and prosecuted according to international fair trial standards.

Methodology

This report is based on field research in Nigeria in July 2010 and in May and July 2012, and the continuous monitoring of Boko Haram attacks and statements. It explores the crimes committed by the group and alleged abuses by Nigeria’s security forces, whose actions in response to the violence have contravened international human rights standards and fueled further attacks.

Human Rights Watch conducted 135 interviews with 91 witnesses and victims of Boko Haram attacks or security forces abuses, as well as with lawyers, civil society activists, journalists, religious leaders, military and police officials, senior officials at the federal Ministry of Justice, a judge, diplomats, and foreign aid workers.

Between July 1 and 5, 2012, a Human Rights Watch researcher interviewed government officials and diplomats in Abuja, and between July 5 and 11, 2010, a researcher visited Maiduguri, Borno State, and conducted 32 interviews, including with 21 witnesses and victims of Boko Haram violence or security forces abuses that occurred during five days of violence in Maiduguri in July 2009. In addition, two Human Rights Watch researchers visited the cities of Maiduguri, Kano, Abuja, and Madalla between May 17 and 31, 2012. These locations were selected for the following reasons:

- Maiduguri, Borno State, is the scene of most of Boko Haram’s attacks and alleged security force abuses. The city was the group’s base before Boko Haram went underground in 2009 and remains its stronghold.

- Kano, Kano State, has suffered the second highest death toll from the violence after Maiduguri. On January 20, 2012, Boko Haram launched coordinated gun and bomb attacks on the city that killed at least 185, its single most deadly day of attacks since 2009.

- Madalla, Niger State, is the site of the December 25, 2011 bombing of St. Theresa’s Catholic Church that killed 43 people—the highest death toll in a single church bombing.

- Abuja, the nation’s capital, is the site of several Boko Haram bombings, including attacks on the United Nations building on August 25, 2011 and ThisDay newspaper offices on April 26, 2012.

Human Rights Watch has withheld the names of witnesses, many of whom expressed fear of talking openly about Boko Haram or security force abuses due to fear of reprisals. Most of the interviews were conducted in private to protect the identity of witnesses. Human Rights Watch did not give witnesses financial incentives to speak.

The report is not exhaustive. Security concerns, especially in the city of Maiduguri, hindered more extensive research. Given the sheer scope of the violence, the report has not documented numerous other incidents of suspected attacks by Boko Haram and alleged security force abuses both in the cities visited and in other locations in northern and central Nigeria. However, the research conducted, together with reports in the Nigerian and foreign media of alleged Boko Haram attacks and statements by its leaders, provides a framework for analyzing the patterns and extent of the violence.

I. Fertile Ground for Militancy

Northern Nigeria, which is predominantly Muslim, has a long history of Islamic uprisings against the state. In the early nineteenth century an Islamic preacher named Usman dan Fodio launched a holy war against what he saw as the corrupt and unjust rule of the Hausa rulers and established the Sokoto Caliphate, and Sharia law, across much of what is today northern Nigeria.[1] After the British overthrew the Sokoto Caliphate in 1903, they incorporated the northern region, along with the southern territories, into the colony of Nigeria in 1914. The colonial laws in northern Nigeria, including criminal laws, retained some aspects of Sharia, but at independence in 1960 the new government limited Sharia law to civil matters.[2]

The first four decades following independence were dominated by a series of military coups and successive military dictatorships interspersed by short-lived civilian administrations. [3] During this period, radical religious groups in the north flourished and at times came into open conflict with the ruling elite, which were increasingly seen as corrupt and abusive. One such group was the Maitatsine sect, which established a large following among the urban poor in the northern city of Kano with its message that denounced the affluent elites as infidels, opposed Western influence, and refused to recognize secular authorities. [4] Eleven days of violent clashes between the Maitatsine and government security forces in December 1980 left more than 4,000 dead. [5] The military crushed the uprising and its leader was killed, but over the next five years hundreds of people died in subsequent clashes between security forces and remnants of the group in several northern cities. [6]

Following the return to civilian rule in 1999, the clamor for Sharia in the north again intensified. Capitalizing on the mood, governors in 12 northern states adopted legislation that added Sharia law to state penal codes.[7] Christian minorities in the north opposed these moves. Although Sharia was added by state governments as a parallel law to existing penal codes, and only applied to Muslims, Christians saw it as a step toward Islamizing the north and undermining their equal rights under a secular state.[8] In 2000, protests against Sharia by Christians in the northern city of Kaduna led to clashes with Muslims, resulting in more than 2,000 deaths.[9] Regarded by many Nigerians as a ploy by northern governors to win popular support, and with limited enforcement mechanisms, implementation of Sharia soon fizzled out in most northern states.[10]

Meanwhile, corruption flourished. Political elites continued to enrich themselves on the nation’s oil wealth, while poverty among the general population, especially in large parts of the north, deepened. Confidence in the often abusive and corrupt police eroded. Ethnic and sectarian violence further exacerbated tensions, all creating a fertile ground for Boko Haram. This section examines some of these factors in further detail.

Corruption and Police Brutality

Nigeria possesses Africa’s largest oil and gas reserves—and exported US$86.2 billion of petroleum products in 2011.[11] When the country gained independence from British colonial rule in 1960, such resources led many Nigerians to be optimistic about the future of their country. Human Rights Watch has documented, however, how, rather than making concrete improvements in the lives of ordinary Nigerians, oil revenues have often fueled political violence, fraudulent elections, police abuse, and other human rights violations.[12] Over the past few decades, poverty has increased, and key public institutions have crumbled. Several hundred billion dollars of public funds have been lost due to corruption and mismanagement.[13] Despite the federal government’s “war on corruption,” graft and corruption remain endemic at all levels of government.[14]

Poor governance and corruption have provided a rallying cry for Boko Haram. According to one Nigerian journalist who has interviewed senior Boko Haram leaders:

Corruption became the catalyst for Boko Haram. [Mohammed] Yusuf [the group’s first leader] would have found it difficult to gain a lot of these people if he was operating in a functional state. But his teaching was easily accepted because the environment, the frustrations, the corruption, [and] the injustice made it fertile for his ideology to grow fast, very fast, like wildfire. [15]

As far back as 2004, early followers of Mohammed Yusuf cited corruption as motivation for their actions. Before being whisked away by the police, one of Yusuf’s followers, arrested in January 2004, told a journalist: “Our group has definitely suffered a setback, but our objective of fighting corruption by institutionalizing Islamic government must be achieved very soon.”[16]

A Christian man who was abducted by Boko Haram gunmen in July 2009 and taken to Yusuf’s compound before he was released later recalled that the group’s leaders told him that:

The reason they [Boko Haram] killed government officials and police was because of corruption and injustice…. They said they are against the government because of the corruption in the government sector. Islam is against corruption, they said. If Sharia is applied, corruption would be eliminated.[17]

Oil provides a corrosive underpinning for official malfeasance in Nigeria. Human Rights Watch has documented how members of the governing elite have squandered and siphoned off public funds to enrich themselves at the expense of basic health and education services for most ordinary citizens.[18] Corrupt politicians have used oil wealth to mobilize violence in support of their political aims.[19]

Corruption has also infected the Nigeria Police Force, undermined the criminal justice system, and fueled police abuses. Human Rights Watch has documented how police routinely extort money from victims of crimes to initiate investigations or from suspects to drop investigations. High-level police officials have embezzled and mismanaged vast sums of money meant for basic police operations, leaving officers on the ground with few resources to ensure public security. Senior officers also enforce a perverse system of “returns,” in which rank-and-file officers pay a share of the money extorted from the public up the chain of command.[20] The police have been implicated in frequent extortion-related abuses, including arbitrary arrests, torture, and extrajudicial killings. Nearly all of these crimes have been committed with impunity.[21]

Boko Haram leaders blame Western influence in Nigeria for corrupting the country’s leaders and corroding the criminal justice system. The Christian man mentioned above, who was abducted by Boko Haram gunmen in July 2009, recalled what one of their leaders told the captives:

[B]efore Western education in the northern area the emir would sort it [criminal matters] out. But after Western education, the police come and take bribes from the complainant and from the accused, and the person who pays the highest gets justice.[22]

While professing to oppose such corruption, Boko Haram has at times openly exploited it for its own ends. In August 2011, for example, Boko Haram claimed it succeeded in carrying out a car bomb attack on the United Nations office in Abuja by bribing government security personnel at checkpoints along the 800-kilometer route from the city of Maiduguri, in northeast Nigeria, to the nation’s capital. “Luckily for us,” a group spokesperson said, “security agents are not out to work diligently but to find money for themselves, and 20 or 50 naira [US$0.12 or $0.31] that was politely given to them gave us a pass.”[23]

Poverty

Nearly 100 million Nigerians live on less than one US dollar a day. In January 2012, Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics released a report showing that the percentage of Nigerians living in “absolute poverty” had increased nationwide from 55 to 61 percent between 2004 and 2010.[24] This rise is especially notable in a country that, in 2011, was the globe’s fourth largest exporter of oil.[25]

Poverty is unevenly spread throughout the country and is less severe in many parts of the south than in the north. Unemployment, lack of economic opportunities, and wealth inequalities are a source of deep frustration across the country, especially in many parts of the north.

The National Bureau of Statistics’ report, for example, shows that 70 percent of Nigerians in northeast Nigeria—Boko Haram’s traditional stronghold—live on less than a dollar a day, compared to 50 and 59 percent in southwest and southeast Nigeria, respectively.[26] According to the government’s 2008 Demographic and Health Survey, less than 23 percent of women and 54 percent of men in northeast Nigeria can read, compared to more than 79 percent of women and 90 percent of men in the south.[27]

Chronic Malnutrition among children is also more prevalent in northern Nigeria than in the south. More than 50 percent of northern children under the age of five are moderately to severely stunted compared to less than 30 percent of their southern counterparts.[28] Infrastructure development also lags behind in the north. In northeast Nigeria, for example, only 24 percent of households have access to electricity, compared with 71 percent of households in the southwest.[29]

Inter-communal Violence

Nigeria is the largest country in the world that is almost equally divided between Christians and Muslims. Its population of some 160 million people belongs to more than 250 different ethnic groups. The vast majority of the north is Muslim, while southeast Nigeria is largely Christian. Many parts of central Nigeria, often referred to as the “Middle Belt,” are predominately Christian, though some states in this region have a Muslim majority. The population of southwest Nigeria is roughly evenly mixed among Christians and Muslims.[30] Divisive state and local government policies that discriminate against individuals solely on the basis of their ethnic heritage and relegate thousands of state residents to permanent second-class status have exacerbated existing ethnic tensions.[31] Boko Haram has exploited Nigeria’s history of ethnic and sectarian strife, along with chronic impunity for perpetrators of violence, including Christians accused of killing Muslims, as justification for its own violent campaign.

Though a national phenomenon, inter-communal violence has been most deadly in the “Middle Belt” region, especially in Kaduna and Plateau states. Since 2000, several thousand people have been killed in each of these states. The victims, including women and children, have been hacked to death, burned alive, and dragged out of cars and murdered in tit-for-tat killings that in many cases were based simply on their ethnic or religious identity.[32] Mobs have burned down both mosques and churches. Since 2010, three mass killings in which more than 100 people died in each incident took place in small towns and villages of these states.[33] The highest death toll occurred in an attack on April 18 and 19, 2011 in the town of Zonkwa, in southern Kaduna State, which left at least 300 Muslim men dead. The attack followed election riots and burning of churches in northern states.[34]

Members of ethnic groups from southern Nigeria who live in the north have also faced violence. In 1966, for example, thousands of Igbo, from southeast Nigeria, were killed in pogroms across the north that followed a military coup led by Igbo officers in which mostly northern political and military leaders died.[35] There have been numerous other incidents since then. In February 2006, for example, anger over the publication in Denmark of controversial cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed reached Nigeria, sparking riots by mobs of Muslims in Maiduguri that left some 50 Christians dead and more than 50 churches burned.[36] Subsequently, more than 80 northern Muslims were killed in reprisal killings by mobs of Christians in southeast Nigeria.[37]

In all but a handful of cases, the Nigerian authorities have failed to prosecute the perpetrators of inter-communal killings, and the cycle of violence has continued.

Boko Haram has often referenced these attacks in justifying its own atrocities.[38] For example, in December 2011, when it claimed responsibility for the 2011 Christmas Day bombing of a church in Madalla, Niger State, the group cited an attack on Muslims on August 29, 2011, in Jos, Plateau State, during a religious service at the end of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. A dozen Muslims reportedly died.[39] A Boko Haram spokesperson said: “What we did was a reminder to all those that forgot the atrocities committed against our Muslim brothers during the Eid el-Fitr celebrations in Jos.” When Muslims were killed, the spokesperson asserted, “the Federal Government and the international community maintained sealed lips.”[40]

II. Boko Haram

We want to reiterate that we are warriors who are carrying out Jihad (religious war) in Nigeria and our struggle is based on the traditions of the holy prophet. We will never accept any system of government apart from the one stipulated by Islam because that is the only way that the Muslims can be liberated. We do not believe in any system of government, be it traditional or orthodox except the Islamic system and that is why we will keep on fighting against democracy, capitalism, socialism and whatever. We will not allow the Nigerian Constitution to replace the laws that have been enshrined in the Holy Qur’an, we will not allow adulterated conventional education (Boko) to replace Islamic teachings. We will not respect the Nigerian government because it is illegal. We will continue to fight its military and the police because they are not protecting Islam. We do not believe in the Nigerian judicial system and we will fight anyone who assists the government in perpetrating illegalities.

—Boko Haram statement, April 2011 [41]

If it runs contrary to the teachings of Allah, we reject it.

—Mohammed Yusuf, BBC Online [42]

Origins

Boko Haram’s origins are central to the group’s self-definition and justification of violent tactics used to fight Nigeria’s government and perceived allies.

In mid-2003, a band of some 200 people, many of them university students or unemployed youth, migrated to a remote region of Yobe State and set up a camp near the Niger border.[43] The group, which was known as Al Sunna wal Jamma (“Followers of the Prophet’s Teachings”), or more commonly the Nigerian Taliban, sought to withdraw from the “corrupt,” “sinful,” and “unjust” secular state of Nigeria and form a new community based on Islamic law.[44] Following disputes between the Nigerian Taliban and local residents, the government authorities sought to disband the group.[45] In December 2003, the Nigerian Taliban attacked a police station in the nearby village of Kanamma, killing a police officer. Over the following week, the group launched raids on police stations and other government buildings in four other towns, including Damaturu, the state capital.[46] The Nigerian government deployed the military and police reinforcements to crush the uprising. The security forces killed or captured dozens of Nigerian Taliban members, and the group was dispersed from the area.[47] During the next year, however, the Nigerian Taliban launched several raids in neighboring Borno State, before the security forces eventually crushed them there as well.[48]

The police said the group’s spiritual leader, a charismatic preacher from Maiduguri named Mohammed Yusuf, had fled to Saudi Arabia, and declared him wanted.[49] The deputy governor of Borno State at the time, Adamu Dibal, later said he met Yusuf in Saudi Arabia. According to Dibal, Yusuf insisted he had nothing to do with the uprising and wanted to return to his family in Nigeria. “Through my discussions with him ... and through my contacts with the security agencies, he was allowed back in,” Dibal said, adding that he thought Yusuf might be “useful to the intelligence agencies.”[50]

After his return to Maiduguri, Yusuf acknowledged that members of the Nigerian Taliban had studied under him but insisted he had urged them not to resort to violence. “These youths studied the Koran with me and with others. Afterwards they wanted to leave the town, which they thought impure, and head for the bush, believing that Muslims who do not share their ideology are infidels,” he said. Yusuf claimed he shared their goal of an Islamic state but didn’t believe in violence: “I think that an Islamic system of government should be established in Nigeria, and if possible all over the world, but through dialogue,” he said.[51]

Yusuf continued to preach and gain followers. The authorities arrested him on various occasions and twice charged him to court, but the prosecutions never went forward.[52] In late 2008 the Borno State government ordered Yusuf and his deputy, Abubakar Shekau, to stop preaching, but they continued.[53] In November 2008, the State Security Service (SSS), Nigeria’s internal intelligence agency, arrested Yusuf for allegedly trying to “incite disaffection against the government of Nigeria.” Authorities arraigned him before a Federal High Court in Abuja in January 2009, but he was released on bail.[54]

Yusuf’s movement eventually took on the name Jama’atu Ahlus-Sunnah Lidda’Awati Wal Jihad (“People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad”). The domestic and foreign press popularized the name Boko Haram, which is a Hausa term meaning, “Western education is sinful.” The name is derived from one of Yusuf’s main teachings that asserts that Western-style education (boko) is religiously forbidden (haram) under Islam.

The July 2009 Violence

The summer of 2009 marked a tipping point in the conflict between Yusuf and the authorities, climaxing in five days of deadly violence in July 2009. Clashes between the group and security forces and brazen execution-style killings by both sides left more than 800 people dead in Borno, Bauchi, Yobe, and Kano states.[55] The targeted campaign of killings by Boko Haram and extrajudicial killings of detainees by government security forces were signs of things to come.

The confrontation began on June 11 in Maiduguri when government security personnel and participants in a Boko Haram funeral procession clashed over mourners’ refusal to wear motorcycle helmets. Members of an anti-robbery task force comprised of military and police personnel opened fire on the procession, injuring 17.[56] Yusuf demanded justice, but the authorities neither investigated the alleged excessive use of force nor apologized for the shooting.[57]

As tensions escalated, the police, on July 21, raided a house of a Boko Haram member in Biu, 180 kilometers south of Maiduguri, and seized bomb-making materials.[58] Later that week, one of Yusuf’s followers in Maiduguri blew himself up when a bomb he was making went off.[59] Yusuf called the man a martyr.[60]

In the early morning hours of July 26, Boko Haram members burned down a police station in Dutsen Tanshi, on the outskirts of Bauchi, the Bauchi State capital. Five Boko Haram members died and several police officers were injured.[61] The military and police responded by raiding a mosque and homes in Bauchi where Boko Haram members had regrouped, killing dozens of the group’s members.[62] Yusuf vowed revenge, saying he was “ready to fight to die” to avenge the killing of his followers.[63]

That night, about two hours before midnight, bands of Yusuf’s followers launched coordinated attacks across Maiduguri. Boko Haram members armed with bows and arrows, knives, cutlasses, and guns, attacked the police headquarters, police stations, and homes of police officers, and attempted to break into the police armory. They torched churches and raided the main prison—freeing inmates and killing prison guards.[64] Boko Haram fighters also launched pre-dawn raids on a police station in the town of Wudil, Kano State, and on government buildings, including a police station, in Postiskum, Yobe State.[65]

By morning in Maiduguri, Boko Haram controlled large parts of the city.[66] Fighting between the security forces and Boko Haram raged and the military airlifted armored tanks and troop reinforcements to the city.[67] On July 28 and 29, the army shelled Yusuf’s compound, killing or flushing out his followers—at least several dozen were killed in police custody.[68]In Postiskum, on July 29, security forces also raided the group’s hideout on the outskirts of town, killing at least 43 of Yusuf’s followers.[69]

On July 30, government security officials in Maiduguri claimed that they had killed Yusuf’s deputy, Abubakar Shekau, a claim that later proved to be untrue.[70] Later that day, the military captured Yusuf who they said was hiding in his father-in-law’s goat pen.[71] Yusuf had predicted at the beginning of the week that if he surrendered or was captured he would be killed by the security agents: “[I]f we give ourselves up or they get us or me…they will kill me,” he said.[72]

Mohammed Yusuf’s Execution

After capturing Yusuf on July 30, soldiers took him to Giwa military barracks in Maiduguri for interrogation.[73] Video footage from the interrogation shows him with a bandage on his left arm.[74] The commander of a military task force in Maiduguri, Col. Ben Ahonatu, said he then handed Yusuf over to the police.[75] Human Rights Watch interviewed a journalist as well as a 24-year-old woman who lived near the police headquarters in Maiduguri who both said they witnessed police shooting Yusuf inside the police compound early that evening. The 24-year-old woman described what she saw:

On Thursday [July 30], about 6:30 p.m., I heard that they [the police] had brought in Mohammed Yusuf…. We went inside the compound of the police headquarters. There were many people watching. I saw him sitting on the ground. He was handcuffed with a bandage on his arm. He was saying they should pray for him. The MOPOL [anti-riot Police Mobile Force] were enraged. They said he killed their leader—who is a 2IC [second-in-command of the Police Mobile Force]. The MOPOL said we must kill him. But the commissioner of police [Christopher Dega] said they should leave him alive.

Then three of the MOPOLs started shooting him. They first shot him in the chest and stomach and another came and shot him in the back of his head. I was afraid and started running. When I came back he was dead. There were a lot of people taking pictures [of his body].[76]

Police officials gave conflicting accounts of what had happened: The assistant inspector general of police in charge of operations in northeast Nigeria, Moses Anegbode, said on state television that evening that security forces had killed Yusuf “in a shootout while trying to escape.”[77] The Borno State police commissioner, Christopher Dega, who witnesses said was present at Yusuf’s killing, claimed that Yusuf had “died in a gunbattle between armed sect members and a joint military-police force.”[78]

However, journalists who had been invited by the Borno State police spokesperson to view Yusuf’s body at the police headquarters had already taken photos of the handcuffed leader’s bullet-riddled body.[79] The next day, the army commander who had apprehended Yusuf flatly rejected the police claims. “He was arrested alive,” Colonel Ahonatu said. “There was no shootout.”[80]

The government’s information minister at the time, Dora Akunyili, welcomed Yusuf’s death, describing it as the “the best thing that could have happened to Nigeria.”[81] But a year later Boko Haram reemerged—vowing to avenge the crimes of the government, and especially Yusuf’s death.

The Group Goes Underground

The government may have thought they had crushed the uprising in July 2009, but the death of the group’s leader did not end the violence. In a video that surfaced in June 2010, Abubakar Shekau, who was Yusuf’s deputy—and the one whom security officials claimed they had killed in July 2009—announced that he had taken over leadership of the group and threatened renewed attacks to avenge the deaths of its members.[82]

This time the remnants of the group had a stark example of the “unjust” secular state that they could rally behind—the brazen execution of their leader. In September 2010, for example, a Boko Haram member told the BBC’s Hausa radio service that “we are on a revenge mission as most of our members were killed by the police.” [83] Similarly, in November 2011, during the trial of six Boko Haram suspects for attacks in Suleja, Niger State, one of the group members told the court that their mission was to avenge Yusuf’s death. [84]

The group’s stated goals include imposing a strict Islamic identity on Nigeria and implementing a harsh interpretation of Sharia law. On December 26, 2011, the day after Boko Haram’s bombing of a church in Madalla, Niger State, Boko Haram spokesperson Abu Qaqa said: “There will never be peace until our demands are met.”[85]

Since the 2009 violence, Boko Haram has remained underground, and little is known about its leadership or organizational structure. Statements from the group have come from two successive “official” spokespersons, using the pseudonyms “Abu Zaid” and “Abu Qaqa,” who have conducted telephone interviews and emailed statements to journalists, but their actual identifies are unknown. [86] Since 2010 Shekau has appeared in several videos posted online claiming responsibility for attacks and threatening further violence.

The clandestine nature of the group has led to much speculation about the composition of its leadership and membership, possible factions, sponsors, and links with foreign groups. In January 2012, for example, President Goodluck Jonathan warned that Boko Haram sympathizers were present at all levels of government:

Some of them are in the executive arm of government, some of them are in the parliamentary/legislative arm of government, while some of them are even in the judiciary. Some are also in the armed forces, the police and other security agencies. Some continue to dip their hands and eat with you and you won’t even know the person who will point a gun at you or plant a bomb behind your house.[87]

There has been little concrete evidence to date of such penetration. [88] Nonetheless, Boko Haram attacks in northern and central Nigeria have increased since 2010 in a largely consistent pattern of violence suggesting a degree of coordination or organizational control.

In July 2012, Johnnie Carson, the US Department of State’s assistant secretary for African affairs, told the House Subcommittee on African Affairs that while information on Boko Haram was limited he believed the group was composed of at least two branches: a “larger organization” that aims to discredit the Nigerian government and a “smaller more dangerous group that is increasingly sophisticated and increasingly lethal.”[89] Other analysts believe that Boko Haram has evolved into a cell-based organization that remains unified under the control of Shekau and a Shura council, though little is known about the composition of this governing body.[90] Criminal gangs in the north, including “political thugs” allegedly mobilized by politicians, are also suspected of committing crimes under the guise of Boko Haram.[91]

Nigeria’s foreign partners have expressed concerns about possible links between Boko Haram and foreign groups, such as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).[92] Boko Haram’s bombing of the United Nations building in Abuja in August 2011, however, has been the only attack to date on a foreign or international institution for which the group has claimed responsibility.[93]

III. Boko Haram Attacks

We hardly touch anybody except security personnel and Christians and those who have betrayed us.

—Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau, speaking in a video message, January 2012 [94]

Boko Haram has attacked a wide array of targets since 2009, including government authorities (especially the police and other members of security agencies); Christians and other “infidels”; and Muslims, including clerics, traditional leaders, and politicians who have criticized its ideology or tactics or were perceived to have collaborated with the government.

The group’s attacks appear to have steadily increased since its reemergence in 2010. Media reports monitored by Human Rights Watch of suspected Boko Haram attacks, show that between July and December 2010, at least 85 people were killed in some 35 separate attacks in four states in northern and central Nigeria, as well as in Abuja, the nation’s capital. Attacks attributed to Boko Haram in 2011 left at least 550 people dead in some 115 separate incidents. In the first nine months of 2012 alone, more than 815 people died in some 275 separate attacks in 12 northern and central states, and Abuja.[95]

After the group reemerged in 2010, police officers and then Muslim leaders including clerics and traditional rulers who criticized the group or were seen as collaborating with the government to identify group members were the initial target of attacks. Most of these attacks were carried out by gunmen, often riding on motorcycles, who shot and killed their victims. In December 2010, suspected Boko Haram members carried out their first major bombings, with attacks on Christmas Eve in the city of Jos and on New Year’s Eve in Abuja. Within six months of these bombings, the group deployed its first suicide bomber in an attack in June 2011 on the police headquarters in Abuja. Since then, suspected Boko Haram members have carried out numerous suicide bombings of police stations and churches, as well as the United Nations building and the offices of a private newspaper in Abuja.

Attacks on Security Forces

Since 2009, government security services—especially police—have been a primary target of Boko Haram. The group has shot and killed police officers on active duty at police stations, roadblocks, government buildings, and churches, and has targeted unarmed off-duty officers in the street, in barracks, and while drinking in bars. Boko Haram has claimed responsibility for bombing police facilities using improvised explosive devices and suicide bombers. The group has also struck at military bases, checkpoints, and vehicles, especially those of the Joint Military Task Force (JTF) in Maiduguri.

Boko Haram has used various tactics when striking at security targets. Gunmen hiding AK-47s or improvised explosive devices under their robes often use motorcycles in drive-by attacks.[96] They have also killed police officers in knife attacks.

During the five days of violence in July 2009 in Bauchi, Borno, Yobe, and Kano states, Boko Haram members attacked police stations, and killed at least 32 police officers in their homes, at police stations, or in the street.[97] According to witnesses and photos seen by Human Rights Watch, some of the police officers who died appeared to have had their throats slashed with knives or swords. One journalist told Human Rights Watch how on July 27, 2009, Boko Haram members, armed with cutlasses and a gun, set upon a police officer near the emir’s palace in Maiduguri:

The police officer told them he was a Muslim and begged for his life. He then recited the Muslim prayer of faith. They [Boko Haram members] pinned him to the ground and pulled back his neck. I looked away and they sliced his neck. People started running away. He was gasping and he died.[98]

Since the group remerged in 2010, suspected Boko Haram members have attacked more than 60 police stations and police facilities in at least 10 northern and central states, and Abuja, and killed at least 211 police officers, according to media reports monitored by Human Rights Watch. These attacks include an apparent suicide car bombing on June 16, 2011 at the police headquarters in Abuja, for which Boko Haram claimed responsibility.[99] Between January and September 2012, at least 119 police officers have died in suspected Boko Haram attacks, more than in all of 2010 and 2011 combined.[100]

Boko Haram leaders say they kill security agents in retaliation for killings by the police of Mohammed Yusuf and Boko Haram members, as well as for other alleged police abuses, including “arbitrary arrest” and “torture,” and the “persecution” of its members.[101]

In the city of Kano, for example, Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau allegedly warned the city’s leaders in December 2011 that unless the “arbitrary arrest and persecution” of his members stops, the group will “launch endless and violent attacks” on the city.[102] Boko Haram has often cited security force abuses to justify its attacks.[103] In a video message posted online in January 2012, Shekau stated that, “[E]veryone has seen what the security personnel have done to us. Everyone has seen why we are fighting with them.”[104] After claiming responsibility for an attack on a police station in Damagun, Yobe State, in March 2012, a Boko Haram spokesperson declared that “all police stations and other security outfits are our targets.”[105]

On January 20, 2012, Boko Haram followed through on its threats with coordinated attacks on the city of Kano. According to witnesses, some Boko Haram members wore police uniforms to gain access to police facilities. The group attacked the state and regional police headquarters, three city police stations, a police barracks, and the home of the assistant inspector general of police in charge of the region. The local offices of the State Security Service and the immigration department were also attacked. [106] At least 185 people, including residents, a journalist, and at least 29 police officers, died in the city-wide assault. [107]

|

|

|

|

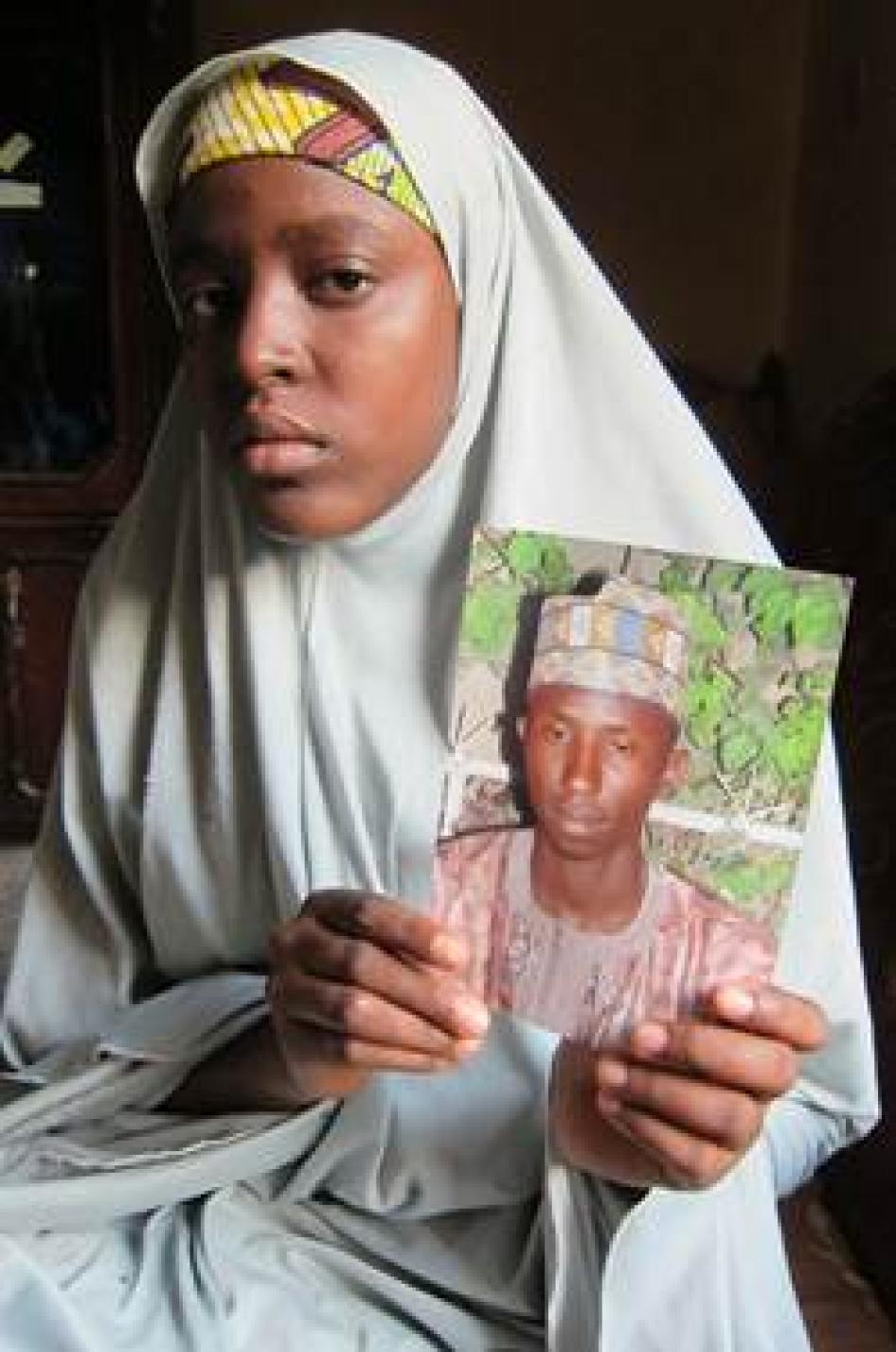

Three women hold pictures of their deceased husbands who were killed by suspected Boko Haram members in the northern city of Kano on January 20, 2012. From left to right: Assistant Police Superintendent Peter Alcor, Police Inspector Musa Muhammed, and Assistant Police Superintendent Edward Entonu. © 2012 Eric Guttschuss/Human Rights Watch

Some of the fatalities, according to witnesses, resulted from suspected Boko Haram members disguised in police uniforms gunning down police officers who approached them and storming the Bompai police barracks, where many officers were off-duty and unarmed. Boko Haram members, witnesses said, moved door to door along the rows of apartments in the barracks on their hunt for victims, shot passers-by at random, and engaged police and soldiers in running gun battles.[108]

A widow of a police officer killed in the barracks told Human Rights Watch how Boko Haram gunmen shot her in the leg, prompting her husband, an officer who had served for 30 years in the police force, to come out of their house:

I was standing in the doorway. It was around 7 o’clock [in the evening]. I saw five men in mobile police uniforms. They had AK-47s. They didn’t say anything. One of them shot me in the leg and I fell inside the house. My husband, he was in uniform, came out and saw them. He had no gun. He asked, “Colleagues, why did you shoot my wife?” And they shot him: bang, in the forehead. He fell down [dead].[109]

The police took the woman to hospital the next morning where doctors amputated her right leg above the knee.

In the eight months since the January 20 assault on Kano, there have been more than 50 smaller attacks in the city.[110] According to the Kano State police commissioner, between February 13 and May 14, 2012, motorcycle-riding gunmen have killed 18 police officers in Kano and injured six other officers.[111]

Attacks on Christians

Boko Haram has carried out numerous attacks on churches and Christians in northern and central Nigeria during its campaign of violence. During the five days of violence in July 2009, for example, Boko Haram members killed 37 Christian men, including three pastors, and torched or partially destroyed 29 churches in Borno State, according to Christian leaders. [112]

Since the group reemerged in 2010, armed gunmen have bombed or opened fire on worshipers in at least 18 churches across eight northern and central states, killing more than 127 Christians and injuring numerous others, according to media reports monitored by Human Rights Watch. A Christian leader in Maiduguri told Human Rights Watch that in Borno State alone, between June 7, 2011 and January 17, 2012, 142 Christians were killed.[113] The attacks on Christians in northern and central Nigeria appear to be part of a systematic plan of violence and intimidation.

According to various statements from Boko Haram, the group is striking at Christians to “start avenging the atrocities committed against Muslims,” undermine “disbelievers and their allies and all those who help them,”[114] and “liberate ourselves and our religion from the hands of infidels and the Nigerian government” as part of a “full scale war between the Muslims and the Christians.”[115]

Boko Haram violence against Christians has included torching and blowing up churches, and carrying out abductions, forced conversions, and attacks in markets and during religious services using guns, improvised explosive devices, or suicide bombers.

During the July 2009 violence, for example, witnesses in Maiduguri said that Boko Haram fighters torched churches, killing men hiding inside, and abducted Christians and took them to Yusuf’s compound.[116] Boko Haram members also killed Christian men after they refused to convert to Islam.[117]

A 15-year-old girl in Maiduguri told Human Rights Watch that on July 26, 2009, the first night of the Boko Haram attacks, she took refuge in a church along with her pastor, the pastor’s brother, a security guard, and a woman from the church. Around midnight Boko Haram assailants armed with guns, knives, and cutlasses tossed Molotov cocktails into the church, broke down the door, and set chairs on fire. She said:

They asked the guard who he was. He said he was the gateman. He begged them to spare his life. The next thing I saw they cut his neck and pushed his body into the chairs.… The pastor’s brother tried to run and they cut him by the head. He fell down inside the church. The pastor and I were hiding by the usher’s table. [It was dark inside and] [t]hey asked the pastor if he was a woman. They then cut him on his hand and head…. That was the last I saw of him.

The assailants then abducted the girl and eventually took her to Yusuf’s compound along with other captured Christians. “They said if we accept to be a Muslim, we will eat. If not, we will not eat,” the girl recalled. She escaped three nights later on July 29 when soldiers shelled the compound.[118]

Another Christian woman in Maiduguri described how Boko Haram fighters, armed with knives, guns, and sticks, came to her house on July 28, 2009 and slit her husband’s throat after he refused to renounce his Christian faith:

They told us to kneel down in front of the house…. They asked me to do the Muslim prayer. I said, “No, I will not do the prayer.” They then turned to my husband. They asked him if he was going to pray and he said, “No.” Then they told him to lie down…. They said if he won’t pray they would kill him. After he refused, one of the men took a knife and cut his throat. They then stood there quietly. I fell down on my husband. They picked me up and took me to their mosque at the compound.[119]

Along with other Christian women at the compound, she was ordered to wash the clothes of Boko Haram fighters killed in the violence and told that she would not be released until she converted to Islam: “[T]hey asked me to convert several times,” she said. “They said if we agree to convert, they will release us. If we don’t convert, they will continue to hold us captive.” She told Human Rights Watch that she saw five Christian men killed at the compound after they refused to renounce their faith. “The women they wouldn’t touch,” she added.[120] However, another witness told Human Rights Watch that Boko Haram killed at least one Christian woman in the camp.[121]

Forced Conversions at Mohammed Yusuf’s CompoundAn Igbo man from southeast Nigeria who was captured by Boko Haram on July 28, 2009 and taken to Yusuf’s compound in Maiduguri, along with his wife and two children, told Human Rights Watch that he saw three people killed in the compound. He said the victims were a police sergeant, a pastor, and a woman who kept urging her husband not to renounce his Christian faith: They took the women and children to a warehouse and locked them up. They searched us….They looked at the identity card of one man and found that he was a police sergeant. They started beating him with their guns. They then dragged him away and cut the back of his neck with a knife. They [then] asked us to do the prayer. They told us if we didn’t pray they would kill us. Those who prayed they took to one side. Those who refused, they kept on another side. I saw a man sitting on the ground. He said he was a pastor. He was preaching and disturbing the Mohammed Yusuf people. He was saying that we should not give up and that we should not betray Jesus. It is better for us to die in Christ. They beat him and then carried him away. I saw one of them cut the back of his neck with a sword. He didn’t die right away but continued to struggle. The third person I saw killed was a woman. She was shouting at her husband not to pray... They [Yusuf’s followers] tried to stop her from tormenting the people, but they couldn’t. Her voice was too much, so they killed her. They dragged her out. [Later] I saw her lying dead. I thought it is better for me to pray to get my family back, so I said I will do the prayer. We did our ablutions and one of them led us in prayer…. They gave me a new name. I chose the name Isa. It means Jesus. [122] |

Human Rights Watch also interviewed three Christian men who were taken by Boko Haram fighters to Yusuf’s compound in July 2009. All three said they had agreed to “say the Muslim prayer” and assume Muslim names to save their lives. They said after they had prayed, Boko Haram leaders explained that they were fighting against the “corruption and injustice” in Nigeria, gave them food, and let them leave the compound.[123] In one case, Yusuf’s men provided an escort for the “former” Christian man and his family back to his home.[124] In another instance, the Boko Haram fighters filled the “newly converted” Muslim man’s vehicle with fuel before they departed the camp.[125]

Since the group reemerged in 2010, its attacks during or after Christian religious services, especially on religious holidays, appear designed to maximize casualties.

On Christmas Eve 2010, gunmen attacked two churches in Maiduguri, killing six people, including a pastor.[126] That same evening in the city of Jos, suspected Boko Haram members detonated several explosives in Christian neighborhoods, which left 33 people dead.[127] Boko Haram claimed responsibility for the attacks.[128] A year later, on Christmas Day 2011, Boko Haram struck at St. Theresa’s Catholic Church in Madalla, Niger State, killing 43 people, in addition to the two bombers.[129] Boko Haram members also attacked a church in Jos that day, killing a police officer on guard.[130]

The largest attack—with the highest death toll as of September 2012 in a church attack—was the Christmas Day 2011 bombing of the church in Madalla. Boko Haram took responsibility for the attack.[131] At 8 a.m. that Christmas Day, witnesses said, worshippers had just begun to exit the front of the church after the end of the first mass. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that a Toyota Camry sedan tried to enter the church grounds, but church security and two police officers stopped the vehicle to inspect it. The car then exploded and flew about seven meters toward the front door of the church. Twenty-six church members and 17 bystanders across the street died in the blast, according to church leaders.[132]

One worshipper had just attended the service with his wife and four daughters, who were walking towards the family car across the street when the bomb went off. All four of his children died in the blast. He said:

There was smoke and dust everywhere. I could see nothing. I looked for my wife and daughters. I found my wife near the front of the church. She was all bloody and someone took her to a hospital by ambulance. She had wounds everywhere and was in a coma [for] six days before she recovered.The girls I could not find for a while—they were all in pieces near the road where I left them. They had wounds to the stomach, arms, and legs. They were broken. My wife, when she awoke, knew right away [that they were dead]. She took them to her hometown for burial.[133]

A mother of five children had stayed home to cook instead of attending the mass with her husband. She ran to the church when she heard there had been an attack:

I fainted. Someone poured water on me and I ran to this place. It was hard to see for the dust. I saw my first daughter twisted and then my first son with a broken hand and hurt eye. My second daughter was burned on the right side of her face. They told me my husband was driving them out of the church when the bomb went off. My husband was burned to ashes.[134]

The woman’s 10-year-old daughter and two sons died. Another son and daughter survived with shrapnel wounds and burns on their bodies.

Following a series of attacks by Boko Haram, including the Christmas Day bombing in Madalla, President Goodluck Jonathan declared a state of emergency on December 31, 2011 in parts of four states.[135] On January 2, 2012, Boko Haram spokesperson Abu Qaqa issued a three-day ultimatum to southern Nigerians, most of whom are Christian, to leave the north.[136] Three days later, on January 5, gunmen attacked a church in the northern city of Gombe, killing six people, including the pastor’s wife.[137] On January 6, gunmen shot 12 worshipers at a church in Yola, Adamawa State.[138] Boko Haram claimed responsibility for the church shootings.[139] On January 11, suspected members of the group opened fire on a commuter van full of Igbo passengers leaving the north, killing four of the passengers, at a filling station in Potiskum, Yobe State.[140] Igbo are the largest ethnic group in southeast Nigeria—the vast majority are Christian.

In a video posted online in January 2012, Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau said that his group was “at war” with Christians because, as he alleged, “they killed our fellows and even ate their flesh in Jos.”[141] Shekau apparently was referring to the August 29, 2011 attack on a Muslim religious service in the city of Jos during the Eid-el Fitr Muslim holiday, which left some 12 people dead.[142] Videos widely circulated on mobile telephones in northern Nigeria appeared to show Christian youth cutting up corpses of Muslim victims and eating the flesh.[143]

On April 29, 2012, suspected Boko Haram gunmen attacked two separate Christian services at Bayero University in Kano, killing 19 worshipers, including two university lecturers.[144] A woman who attended the worship service at the sports hall on campus told Human Rights Watch that attackers shot worshipers who cowered on the ground. “A gunman came to us and shot two men nearby me,” she said.[145]

Boko Haram’s attacks on Christians have not only resulted in death, injury, and forced conversion, but they have also sparked sectarian clashes in already volatile states. On three successive Sundays in June 2012, for example, suicide bombers detonated explosives at church services in Bauchi, Bauchi State; Jos, Plateau State; and Zaria and Kaduna, Kaduna State—all locations of past episodes of inter-communal violence.[146] The June 17 attacks on two churches in Zaria and a church in Kaduna killed at least 21 people and set off several days of reprisal and counter-reprisal killings between Christians and Muslims, resulting in some 80 more deaths.[147] Similarly, the Christmas Eve 2010 bomb blasts in Christian neighborhoods in Jos sparked a month of sectarian bloodletting that claimed around 200 Muslim and Christian lives.[148]

Observers say that Boko Haram’s attacks on Christians are deliberately designed to weaken the government and exploit existing ethnic and religious fault lines.[149] According to one Nigerian journalist who has interviewed senior Boko Haram members:

It is … a strategy by Boko Haram to bring the government to its knees by creating a war situation.… They know that the most important area that can bring down law and order is religion. So they are attacking Christians. When the Christians decide to retaliate they don’t know who is a Boko Haram member, so Christians will just retaliate against Muslims and that will further polarize the country.[150]

Attacks on Muslim Critics and Government Collaborators

Suspected Boko Haram members have carried out numerous attacks on Muslims who either publicly opposed Boko Haram tactics or ideology, or cooperated with government authorities against the group. These include traditional rulers, Islamic clerics, politicians, and civil servants. The attacks frequently involve gunmen arriving on motorcycles, quickly identifying their target, and gunning down the victim, sometimes inside mosques or private homes.

Boko Haram has frequently warned against cooperating with the government or collaborating with security agents. In January 2012, for example, Boko Haram leaflets distributed around the city of Kano stated:

We have on several occasions explained the categories of people we attack and they include: government officials, government security agents, Christians loyal to CAN (Christian Association of Nigeria) and whoever collaborates in arresting or killing us even if he is a Muslim.[151]

Human Rights Watch interviewed three men in Kano who said they witnessed a shooting on February 24, 2012, at an open-air mosque, of a local vigilante group leader who had been cooperating with the police. One witness said that the victim had earlier told him that he had received threatening messages in the previous month from suspected Boko Haram members. The witness said that two gunmen, riding on a motorcycle, pulled up to the mosque during Friday prayers. One of the gunmen then shot dead the vigilante leader along with three other worshipers:

The one on the back got off the motorcycle. He was wearing a trench coat and pulled out a gun—an AK-47. He shouted “Allahu Akbar” and “Jihad.” He then began shooting into the worshipers. I was sitting in front of the congregation. I was paralyzed but I then regained my courage and ran away. He shot those who tried to flee. Some of us were lucky and were able to escape. [152]

Boko Haram spokesperson Abu Qaqa later claimed responsibility for the shooting on behalf of the group.[153]

In the past two years, suspected Boko Haram members have shot and killed at least 12 Islamic clerics in Borno State alone, according to media reports monitored by Human Rights Watch.[154] Most of the clerics, including several elderly imams, were gunned down in their homes by armed men riding motorcycles.

Fundamentalist “Wahhabi” clerics who have been critical of Boko Haram and its leadership appear to have been particular targets. In October 2010, for example, gunmen shot and killed a prominent Wahhabi cleric who was an outspoken critic in Maiduguri. [155] The following month in Maiduguri, a gunman riding a motorcycle opened fire on worshipers in a Wahhabi mosque, killing three, including a 10-year-old boy. [156] In June 2011, a motorcycle gunman in Biu, south of Maiduguri, killed a prominent Wahhabi cleric at close range. [157]

In addition, suspected members of the group have gunned down at least eight traditional leaders—ward and district heads—in Borno and Yobe states in the past two years, according to media reports.[158] In September 2010, a Boko Haram member said in an interview on the BBC’s Hausa radio service that traditional leaders were targeted for “disclosing the name and whereabouts of our sect members.”[159] Similarly, in June 2011, a Boko Haram spokesperson told journalists: “[T]hese traditional institutions are being used to track and hunt us. That is why we attack them.”[160] On July 13, 2012, a suicide bomber detonated himself outside the central mosque in Maiduguri following Friday prayers, killing five people in an apparent assassination attempt on the shehu of Borno, the state’s highest traditional ruler.[161] In a similar attack on August 3, 2012, a suicide bomber blew himself up outside the central mosque in Potiskum, Yobe State, where the emir of Fika, the highest traditional ruler in the state, was attending Friday prayers.[162]

Suspected members of Boko Haram have also killed civil servants—nearly all Muslim—and assassinated more than a dozen politicians in Borno and Yobe states since 2010, according to media reports.[163] In September 2012, for example, suspected Boko Haram gunmen shot and killed Borno State’s attorney general.[164] The group claimed responsibility for the January 2011 killing of the leading candidate at the time in Borno State’s 2011 gubernatorial elections[165] and is also suspected in the October 2011 assassination of a federal legislator who was gunned down outside his home in Maiduguri.[166] “We shall kill anyone who works against Islam,” Shekau vowed in an online video in January 2012, “even if he is a Muslim.”[167]

Attacks on the UN, Bars, and Schools

Boko Haram has not only carried out attacks on government security forces, Muslim and Christian targets, and perceived government collaborators and critics of Boko Haram. It has also targeted other bodies and institutions that it regards as allied with the government or opposed to its own objectives, such as the United Nations, election facilities, media, and even schools.

The group has bombed or carried out gun attacks on at least a dozen bars or entertainments centers in northern Nigeria, according to media reports monitored by Human Rights Watch, and launched a handful of prison raids to free its members.[168] According to media reports, suspected Boko Haram members have blown up more than a dozen banks in northern towns—usually in conjunction with an attack on the town’s police station in which the group would seize guns and ammunition.[169] Some observers suggest that attacks on banks may be the work of common criminal gangs, but Boko Haram has claimed responsibility for some of the raids. In July 2011, for example, Boko Haram spokesperson Abu Qaqa told journalists that the group had “carted away huge sums of money” from three banks. “We took the measure because the mode of operations of the banks was not based on Islamic tenets,” he said.[170] In September 2012, the group claimed responsibility for attacks on more than two dozen mobile telephone towers across northern Nigeria, saying it carried out the attacks because telephone companies were providing information to the authorities to track down its members.[171]

United Nations Headquarters

On August 26, 2011, a bomb-laden car drove through two barriers protecting the UN headquarters in Abuja and detonated. The bomb blew out windows throughout the building and badly damaging the ground floor reception area and first two floors. The blast killed 25 people—22 Nigerians, 1 Norwegian, and 1 Kenyan—and injured more than 100.[172]

Boko Haram spokesperson Abu Qaqa said the group had carried out the blast because the “UN represents unbelief and they support the Nigerian government whom we are fighting.”[173]The attack on the UN building has been the one attack to date on an international or foreign target for which the group has claimed responsibility.

Media

Boko Haram has claimed responsibility for several attacks on the media and issued threats of further violence. On April 26, 2012, the group bombed Nigeria’s ThisDay newspaper office in Abuja and a building that houses several media outlets, including ThisDay, in the northern city of Kaduna. Four people were killed in the suicide car bombing in Abuja, and three died in the Kaduna blast, according to witnesses and media reports.[174]

In an online statement, the group said it bombed ThisDay, a Lagos-based private newspaper, because the newspaper had reported many “lies” about Boko Haram.[175] The statement also claimed that the group was exacting revenge on the newspaper for publishing a 2002 story about the Miss World beauty contest slated to be held that year in Nigeria that Boko Haram said had “dishonored” the Prophet Mohammed.[176] The statement by the group also named other media houses that it threatened to attack.[177]

In addition to these bombings, Boko Haram also claimed responsibility for killing a cameraman who worked with the government owned National Television Authority, in Maiduguri on October 22, 2011. Boko Haram claimed that he was an “informant of security agencies.”[178] A journalist with Channels Television, a private Lagos-based station, was shot and killed during the January 20, 2012 attacks in Kano.[179]

Schools

Since the beginning of 2012, Boko Haram members have attacked at least 20 schools in northern Nigeria, damaging and in some cases destroying them, according to media reports monitored by Human Rights Watch. The group began torching schools in February in a two-week spate of attacks on at least 12 schools in and around Maiduguri, temporarily leaving several thousand children without access to education. All of the attacks occurred at night or early in the morning when pupils and teachers were absent.[180]

A Boko Haram spokesperson told journalists that the attacks were in response to alleged security force raids on Quranic schools and “indiscriminate arrests of students of Koranic schools by security agents.”[181] Suspected members of the group have also burned down schools in Gombe, Yobe, and Kano states, according to media reports.[182]

IV. Security Forces Abuses