“You Are All Terrorists”

Kenyan Police Abuse of Refugees in Nairobi

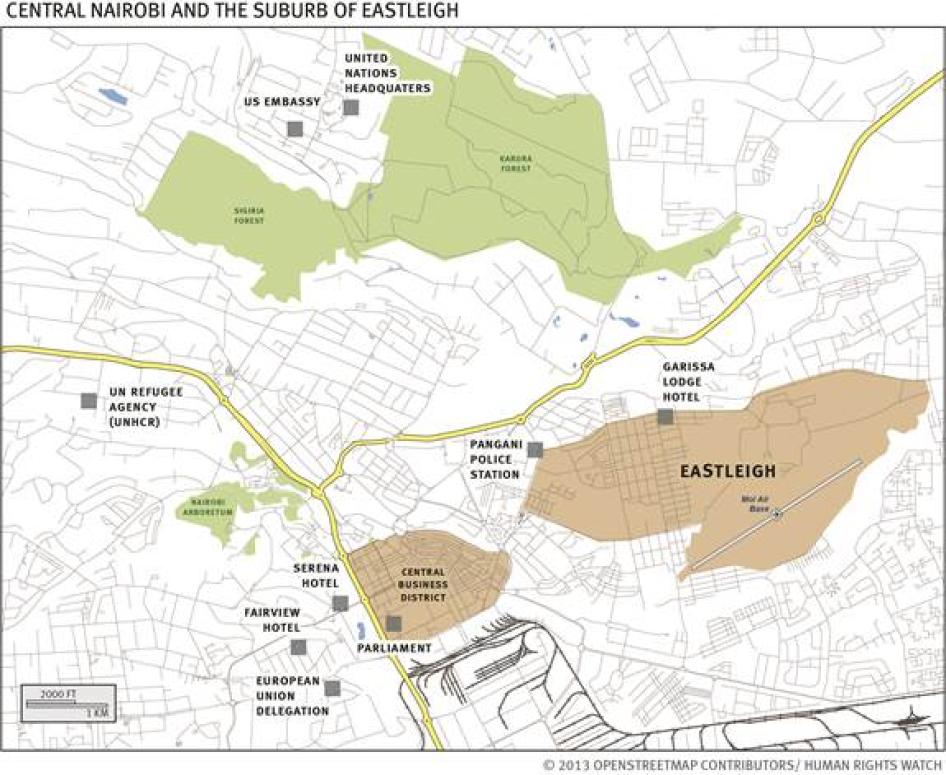

Map

|

I was walking home on 4th Street when three RP [Regular Police] officers—one woman and two men—stopped me. I showed them my refugee documents and they just attacked me. The woman grabbed my breasts and shoulders and tried to lift my veil and then pushed me into a ditch by the roadside. Then all three hit and kicked me and tore at my clothes. The woman was shouting ‘you are a prostitute’ and ‘you Somalis are all Al-Shabaab and terrorists.’ Then they put me in their car and we drove off. It was dark so I did not know where we were. When we stopped, the woman and one of the men got out of the car and left me in the car with the other man who hit my legs with his truncheon and slapped me. Then he raped me. When he finished he got out of the car and the other man got in and raped me. When it was over, they drove me for some time and then shouted at me to get out of the car. Then they just drove away. Human Rights Watch interview with 34-year-old Somali woman living with her four children in Eastleigh since 2008, Eastleigh, Nairobi, February 4, 2013 |

|

The evening of November 19, around 6 p.m. [a day after the Eastleigh bus bombing that killed at least seven people] I went to the mosque. I left my 12-year-old daughter at home. When I got back to my apartment, I saw many GSU [police] officers with batons. I rushed up the stairs and saw the front door was open. My daughter later told me the police had kicked it down and asked her for our jewelry. There were five officers. My daughter rushed towards me, crying, but one of the officers grabbed her and threw her down the stairs. One of the other officers grabbed me by the arms and another kicked me. Then both grabbed me and threw me down the stairs too and my hijab [veil] came undone. The officers picked us up and tossed us like bundled goods into their truck. We drove through town and they picked up many more Somalis, near the mosque and in the streets, until the truck was full. They drove us to the Pangani police station and said anyone who wanted to leave should pay and that anyone who refused would be taken into the police station. A man and his wife offered Ksh 15,000 (US$ 181) to have all four of us released. The police agreed but said, ‘If we release you now, other police will arrest you again,’ so they kept us in the truck for six hours, until midnight. Then they just let us go.

Human

Rights Watch interview with Somali woman in Eastleigh, Nairobi, |

Summary

The police kept saying we were Al-Shabaab terrorists and said ‘Somalis are like donkeys: they have no rights in Kenya.’

—Somali refugee on what Kenya police told him in Nairobi’s Pangani police station on November 19, 2012

On November 19, 2012, Kenyan police from four different units unleashed a wave of abuses, including torture, against Somali and Ethiopian refugees and asylum seekers and Somali Kenyans in Eastleigh, a predominantly Somali suburb of Nairobi only a few kilometers from the city’s business district, foreign embassies, United Nations headquarters, and tourist hotels.

The sudden escalation of police abuses came one day after unknown perpetrators attacked a bus in Eastleigh killing seven people and injuring 30. The abuses ended in late January, a few days after the Kenyan High Court ordered the authorities to halt a proposed plan to relocate all urban refugees to refugee camps.

This report, based on 101 interviews, documents abuses during this period in Eastleigh that directly affected around one thousand people. Witnesses and victims of abuse told Human Rights Watch that police personnel from the General Services Unit (GSU), the Regular Police (RP), the Administration Police (AP), and the Criminal Investigations Department (CID) committed the abuses, which included rape, beatings and kicking, theft, extortion, and arbitrary detention in inhuman and degrading conditions. Many women and children were among the victims. Police officers also arrested and charged hundreds of Eastleigh residents with public order offenses without any evidence, before the courts ordered their release.

Almost every refugee and asylum seeker Human Rights Watch interviewed about police abuses they faced in Eastleigh between November 19 and late January 2013 said the police repeatedly accused them of being “terrorists,” indicating one motivation for the abuses appeared to be retaliation for some 30 attacks on law enforcement officials and civilians by unknown perpetrators in Kenya since October 2011. To date only one person—a Kenyan national not of Somali ethnicity—has been convicted for one of the attacks.

Furthermore, almost every one of the 101 people interviewed for this report said police demanded victims pay them large sums of money and then let them go, indicating that personal gain—not national security concerns—was the main reason police targeted and abused their victims.

In fifty cases involving rape and serious violence in which officers accused their victims of being terrorists or coerced them into paying money, Human Rights Watch concluded the abuses amounted to torture under the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention against Torture).

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch how police raped them—including two cases of gang rape—in homes, side streets, on wasteland, and in some cases with children close by. They described how police beat, kicked and punched them—including women and children—in their homes, in the street and in police vehicles, causing serious injury and long-term pain. They spoke about how police entered their homes, often in the middle of the night, and businesses to steal large amounts of money and other personal belongings and to extort money from them to secure their release. And they explained how police arbitrarily detained them in their homes, in the street, in police vehicles, and in police stations where they held them, sometimes for many days, in inhuman and degrading conditions while threatening to charge them, without any evidence, on terrorism or public order charges.

On December 13, 2012, Kenya’s Department of Refugee Affairs (DRA) announced in a press conference that the spate of attacks meant all 55,000 refugees and asylum seekers living in Nairobi should move to the country’s closed refugee camps near the Somali and Sudanese borders or face forced relocation there and that all registration of, and services for, urban refugees would end immediately. As of this writing, all registration and most services remain suspended.

After the announcement, police officers continued their rampage and used threats of transfer to the camps or deportation to Somalia as a further excuse for their abuses and extortion.

Acting on a legal challenge by the Kenyan nongovernmental organization (NGO) Kituo Cha Sheria (“Center for Law”) on January 23, 2013, Kenya’s High Court blocked the planned transfers to camps while it considers whether the transfers would violate Kenyan and international law. As of this writing, the Court was scheduled to hear the case on May 20, with a decision to follow soon after.

The December 13 transfer announcement fails to show that the plan to force tens of thousands of refugees living in Kenya’s cities into closed camps is both necessary to achieve enhanced national security and proportional (i.e., the least restrictive measure to address Kenya’s genuine national security concerns). It also clearly discriminates between Kenyan citizens and refugees because the policy allows Kenyans to move freely and denies refugees that right, which they have under the Refugee Convention, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and Kenyan law.

Under international law, transferring refugees from the cities to squalid, overcrowded, and closed refugee camps facing a funding shortfall of over US$100 million would also violate a range of their other rights, including the right to free movement, the right not to be forcibly evicted from their homes, and the right to access basic economic and social rights—such as the right to food, livelihoods, health care, and education.

Fearing possible forced transfer to the camps and more abuses, thousands of Somali nationals living in Nairobi have already left the city, either returning to Somalia or other neighboring countries, according to the United Nations. If the court rules the transfer would be legal, refugees and asylum seekers unwilling to move to the camps—including to the new Kambioos camp near the town of Dadaab—or return to ongoing insecurity in Somalia face the risk of more police violence.

Forcibly transferring urban refugees to Kenya’s refugee camps to face extremely difficult living conditions and increasing insecurity also risks causing refugees to jeopardize their safety by returning prematurely to Somalia.

Kenyan police abuses against Somali refugees and Somali Kenyans are not new. In 2009, 2010 and 2012, Human Rights Watch reported on Kenyan security force abuses, including torture, rape, and other serious forms of violence, against Somali Kenyans and Somali refugees throughout Kenya’s predominantly Somali inhabited North Eastern region, including in and around the Dadaab refugee camps sheltering almost half a million mostly Somali refugees.

On all three occasions the authorities said they would investigate the abuses and publish their findings, but to date they have published no findings and have not prosecuted anyone responsible for the abuses, fuelling the well-documented culture of impunity in Kenya’s law enforcement agencies that appears to have encouraged the latest wave of police abuses in Nairobi.

In late January 2013, refugee organizations in Nairobi condemned reports of police abuses in Eastleigh in the previous months, but as of mid-May, no organization has published detailed findings on the nature and extent of the abuses, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Nairobi. Refugee organizations in Nairobi say the failure is at least in part because until late January 2013, UNHCR did not have an effective rights abuse monitoring system in place to document the abuses which means refugee organizations had little incentive to collect information about the abuses to share with UNHCR.

UNHCR told Human Rights Watch it has raised reports of abuses with the Kenyan authorities. But at no point during or since the 10-week wave of abuses did UNHCR publicly call on the authorities to rein in their abusive police forces and to hold officers accountable.

On March 18, 2012, Human Rights Watch wrote to Kenya’s Inspector General, the then Minster of Internal Security and Provincial Administration and to the Commissioner for Refugee Affairs outlining our findings and requesting comment. As of this writing, Human Rights Watch had not received a response.

Absent effective Kenyan accountability mechanisms to prevent police abuses and to punish Kenyan police officers who perpetrate human rights abuses against refugees and asylum seekers in Eastleigh and elsewhere, it is crucial that UNHCR publicly and unambiguously oppose the relocation of Kenya’s urban refugees to refugee camps—which so far it has not done—and monitor and publicly report on any future police abuses in Nairobi and elsewhere. Foreign donors, in particular those who fund UNHCR, should encourage UNHCR to do so.

UNHCR, donor governments, and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ Special Rapporteur on Refugees, Asylum Seekers, IDPs and Migrants in Africa should raise the abuses, including acts of torture, set out in this report with the Kenyan authorities and call on them to investigate commanding police officers responsible for police units present in Eastleigh between mid-November 2012 and late January 2013 and to ensure no such abuses reoccur.

Donor governments should in no way support the Kenyan authorities’ plans to forcibly transfer refugees to the camps and should encourage the authorities to abandon those plans. Donors should also refuse to support any other Kenyan initiatives that might contribute directly or indirectly to forcing Somali refugees to return to Somalia before that country is safe for returns.

Recommendations

To the Government of Kenya

To the Deputy Inspector Generals of the Regular Police and Administration Police

- Instruct the police to:

- Stop rape, beatings, and other unlawful violence against refugees, asylum seekers, and Somali Kenyans, some of which amount to acts of torture;

- Stop arbitrarily detaining refugees, asylum seekers, and Somali Kenyans, particularly in Pangani police station;

- Stop stealing and extorting money from refugees, asylum seekers, and Somali Kenyans;

- Stop charging refugees, asylum seekers, and Somali Kenyans with public order-related offenses without any evidence.

To the National Police Service Commission (NPSC) and the Independent Police Oversight Authority (IPOA)

- The NPSC should:

- Investigate commanding officers—including, if appropriate, the police inspector general and his two deputies—responsible for police units active in Eastleigh between mid-November 2012 and late January 2013, as well as police officers under their command suspected of abuses, and discipline and prosecute any found to have committed crimes, including torture;

- Create a special committee of inquiry to report back to the NSPC on the extent and nature of police abuses, including torture, against refugees and asylum seekers in Eastleigh between November 2012 and January 2013 with recommendations for which commanding officers should be held responsible for the abuses;

- Ensure that the committee formed in 2010 to investigate law enforcement abuses against Somali Kenyans and Somali refugees in North Eastern region which Human Rights Watch documented publishes its findings and that a new committee be established to investigate the abuses Human Rights Watch documented in Mandera region in 2009.

- The IPOA should publicly encourage refugees and asylum seekers to lodge complaints with the IPOA against officers known to be involved in torture and other abuses.

- The IPOA should take specific steps to help ensure women can safely lodge complaints about sexual violence by police, including protecting their identity from being known in their local community, ensuring that female staff are available to take their statements and referring them to service providers specialized in helping survivors of sexual violence.

To the Chief of Defence Forces

- Ensure that the committee formed in 2012 to investigate law enforcement abuses documented by Human Rights Watch against Somali Kenyans and Somali refugees in North Eastern region publishes its findings.

To the Ministry of Interior and Coordination of National Government

- A bandon unlawful plans announced on December 13, 2012 to forcibly transfer Kenya’s urban refugees to Kenya’s refugee camps.

- End plans to use the new Kambioos camp in Dadaab to relocate urban refugees from Nairobi and other cities; instead, with the support of foreign donors, work with UNHCR and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to prepare Kambioos for the voluntary transfer of refugees from the other massively overcrowded older refugee camps in Dadaab.

- Do not introduce any other measures or take actions aimed at forcing refugees and asylum seekers to leave Kenya’s cities or that have the indirect effect of forcing them to return to their countries where they risk persecution or generalized violence; instead, allow UNHCR and NGOs to continue to carry out and plan their work with all refugees in Kenya until it is safe for them to return to their country.

To the Department of Refugee Affairs

- Restart registration of asylum seekers and renewal of refugees’ papers in urban areas immediately and announce that UNHCR and NGOs may resume full services to refugees and asylum seekers in urban areas.

To the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- Investigate the November 2012-January 2013 abuses against refugees and asylum seekers documented in this report and publish UNHCR’s findings.

- Push for police accountability with the Kenyan authorities for such abuses in line with the above recommendations.

- Support refugees and asylum seekers to file formal complaints with the police, including the identification of officers who abused them.

- Dedicate enough protection officers to work closely with NGOs in Eastleigh and other parts of Nairobi to monitor and document police abuses effectively; if abuses reoccur, raise them with the Kenyan authorities, proactively share such information with donor governments, and publicly denounce them.

- Publicly and unambiguously oppose the authorities’ unlawful urban refugee relocation plans.

- Impress on the Kenyan authorities the negative effects of the suspension of registration and services in urban areas.

- Raise concerns over Kenya’s police abuses of Somali asylum seekers and refugees and any continued plans to relocate urban refugees at the October 2013 meeting of UNHCR’s Executive Committee in Geneva.

To the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ Special Rapporteur on Refugees, Asylum Seekers, IDPs and Migrants in Africa

- Call on Kenya to ensure abuses such as those documented in this report do not reoccur and to discipline or charge any police officers found to be responsible for abuses.

- Call on Kenya to abandon its unlawful plans to relocate urban refugees to the country’s refugee camps and to respect its international obligations towards refugees and asylum seekers.

- Request permission to visit Kenya to speak with government officials, UNHCR, and NGOs working with refugees and asylum seekers and issue a public report on the extent of abuses faced by urban refugees and asylum seekers in Eastleigh between mid- November 2012 and late January 2013.

To Donor Governments Providing Support to UNHCR and to Kenya

- Raise the abuses set out in this report with the Kenyan authorities, including during bilateral meetings at UNHCR’s Executive Committee meeting in Geneva in October 2013, and call on them to ensure such abuses do not reoccur and to hold responsible officers to account.

- Vet all law enforcement individuals enrolled in training or assistance programs to ensure that they were not deployed to Eastleigh between mid-November 2012 and late January 2013.

- Condition security sector assistance on accountability for past abuses during operations by the security forces in Eastleigh, North East region, Mount Elgon, and other locations.

- Insist on a human rights component for all security force training programs as a condition of security assistance.

- Include reports on abuses and Kenya’s violation of international refugee and human rights law in reviews of bilateral aid to Kenya.

- Support any UNHCR efforts to encourage refugees and asylum seekers willing to lodge complaints against the police for abuses committed.

- Encourage UNHCR to improve its protection monitoring in Eastleigh and other parts of Nairobi and request regular updates from UNHCR on its findings and related advocacy with the Kenyan authorities.

- Urge the Kenyan authorities to abandon the unlawful plan to forcibly relocate urban refugees to camps.

- Urge UNHCR to publicly oppose the relocation plan.

- Do not commit funding in advance to develop Kambioos camp for the purpose of relocating urban refugees, but generously fund its development to help decongest the old camps in Dadaab.

- Continue to support refugee organizations, including UNHCR, providing Somali refugees in the Dadaab camps with assistance and protection to ensure they do not feel compelled to return to Somalia due to poor conditions in the camps.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, between January 28, 2013 and February 8, 2013, including five days in the suburb of Eastleigh during which two Human Rights Watch staff (one male and one female) conducted in-depth interviews with 96 Somali and Ethiopian registered refugees and asylum seekers (31 men, 64 women, and 1 girl) and with 5 Somali Kenyans (two men and three women).

Human Rights Watch worked with NGOs in Eastleigh and with other local contacts to identify refugees and asylum seekers who had experienced Kenyan police abuses since mid-November 2012. Interviews were conducted individually in private, confidential settings and lasted an average of 30 minutes.

Human Rights Watch staff explained the purpose of the interviews, gave assurances of anonymity, and explained to interviewees they would not receive any incentives for speaking with Human Rights Watch. We also received interviewees’ consent to describe their experiences. Particular care was taken to ensure that rape survivors were comfortable with talking about what had happened to them and that they were aware they could terminate the interview at any point. Human Rights Watch gave rape survivors information about confidential nongovernmental physical and mental health care services available close to where they lived. Individual names and other identifying details have been removed to protect their identity and security.

All interviews were conducted in English and Somali or English and Amharic using interpreters. Estimates of the dimensions of detention cells are based on interviewees’ comparisons with the size of the interview space. Whenever interviewees referred to police committing abuses, interviewers asked the interviewees to describe the uniform the police were wearing and thereby identified whether the police officers concerned belonged to the General Services Unit (GSU), Administration Police (AP), Regular Police (RP) or the plain-clothed Criminal Investigations Department (CID).

Based on the 101 interviews, Human Rights Watch documented abuses affecting around one thousand people.

Human Rights Watch also conducted 11 interviews with staff from national and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and with staff from 15 foreign embassies. In late January and early February 2013, Human Rights Watch repeatedly asked to meet with Kenya’s Department of Refugee Affairs (DRA) and with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Nairobi but received no response.

On March 18, 2012, Human Rights Watch wrote to Kenya’s inspector general, the then minster of internal security and provincial administration, and to the commissioner for refugee affairs outlining our findings and requesting comment. At this writing, Human Rights Watch had not received a response.

I. Background

Between October 2011—when Kenyan military forces deployed in Somalia—and December 2012, Kenya faced over 30 attacks by unknown perpetrators involving grenade and other explosives, resulting in dozens of deaths and hundreds of casualties. Six attacks occurred in November 2012 and December 2012 in Nairobi’s Eastleigh suburb, home to hundreds of thousands of Somali Kenyans and Somali refugees. To date only one person, a Kenyan national not of ethnic Somali origin, has been prosecuted and convicted relating to one of the attacks in October 2011.[1]

On December 13, 2012, Kenya’s Department of Refugee Affairs announced that because of the attacks, Kenya’s 55,000 registered urban refugees should move to the country’s refugee camps, thereby implying that urban refugees—and particularly Somali refugees—constituted a security threat. Refugees told Human Rights Watch that police who abused them in Eastleigh used the threat of arrest and prosecution on terror charges—calling them “terrorists”—as an excuse to abuse and extort money from them.

Police extortion and arbitrary arrests of refugees in Eastleigh is not new, nor is discrimination and abuse by Kenyan security forces of Somali Kenyans and Somali refugees. However, the scale and intensity of the crackdown that ensued in Eastleigh between mid-November 2011 and late January 2013 was unprecedented.

By late January, the security force crackdown declined, most probably because on January 23 Kenya’s High Court ruled the authorities should suspend their plans to relocate urban refugees to the camps and because security forces began to focus on Kenya’s then looming national elections on March 4. As of mid-May when this report went to print, a new government was being established and President Uhuru Kenyatta had released a list of cabinet nominees to be taken to parliament for approval.[2]

Grenade and Other Attacks in Kenya Since October 2011

In October 2011, Kenya launched a military offensive against the Islamist armed group Al-Shabaab in Somalia. Al-Shabaab promised revenge, threatening to bomb buildings in Nairobi and to kill civilians.[3]

Since then, Kenya has faced over 30 attacks involving grenades and other explosives, which resulted in at least 76 deaths and hundreds of injuries.[4] Kenyan government officials have blamed Al-Shabaab and its sympathizers in Kenya for these attacks, although the group has only claimed responsibility in a small number of cases.

The majority of the 2012 attacks happened in Nairobi, in the coastal areas, and in North Eastern region, including in the Dadaab refugee camps, home to around 450,000 mostly Somali refugees.[5] The deadliest such attack occurred on July 1, 2012, when masked gunmen launched simultaneous gun and grenade assaults on two churches in Garissa, the main town in North Eastern region, killing 17 and wounding more than 60.[6]

Nairobi suffered numerous attacks in 2012, including at bus stations, churches, and shopping centers. At least six of the attacks involved grenades or improvised explosive devices (IEDs), resulting in severe injuries and significant damage to property.[7]

Nairobi’s Eastleigh suburb—only a few kilometers from Kenya’s central business district and a few kilometers more from a number of international embassies, UN headquarters, and major tourist hotels—saw six attacks in as many weeks during November 2012 and December 2012. The suburb has about 350,000 inhabitants, made up mostly of Somali Kenyans—who since Kenya’s independence from British colonial rule in 1963 have built a vibrant business community there—as well as tens of thousands of registered Somali refugees and likely tens of thousands more unregistered Somali nationals who started fleeing Somalia in 1991.[8]

The first, and most serious, attack in Eastleigh occurred on November 18, 2012, when an IED was thrown at a crowded mini-bus. At least seven people were killed, and over 30 were seriously injured.[9]

The same day, youth gangs from neighboring suburbs stormed the streets of Eastleigh and attacked residents of Somali origin, including both refugees and Somali Kenyans. Several people were stabbed, and others were injured by stones. Some local news outlets cited reports that 10 women were raped. The gangs looted Somali-owned shops and caused significant damage to property. Kenyan security forces deployed to the streets in large numbers and fired shots into the air and used tear gas against protesters. The riots ended on November 20, 2012.[10]

Refugees and asylum seekers told Human Rights Watch that the police abuses described in this report, including cases of gang rape, began on November 19, a day after the attack on the mini-bus.

Less than three weeks after the November 18 attack, Eastleigh was hit by more attacks. On December 5, a roadside bomb exploded during rush hour traffic, killing one person and injuring eight.[11]

On December 7, an unidentified assailant threw a hand grenade at the Hidaya Mosque on Eastleigh’s Wood Street just as worshippers were leaving Friday evening prayer, killing five people and seriously injuring sixteen, including Yusuf Hassan, a member of parliament for Nairobi’s Kamukunji Constituency.[12]

Again, angry protesters burned and looted Somali-owned shops the same night. Kenyan security forces quickly prevented the situation from escalating.[13] But following the attack, police launched another large-scale police sweep in Eastleigh. Media reports said police detained more than 300 suspects, mostly Somali nationals, over the next two days.[14]

MP Yusuf Hassan, who witnessed the youth gang attacks on November 19 and who has liaised extensively with police over the attacks in Eastleigh, told Human Rights Watch that as of early February police had told him not a single person had been charged and prosecuted over the IED and grenade attacks in Eastleigh in November 2012 and December 2012 (including the attack in which Hassan himself was injured).[15]

On December 13, 2012, Kenya’s Department of Refugee Affairs announced that Kenya’s 55,000 registered urban refugees and asylum seekers would be required to move to refugee camps in Kenya’s northeast and northwest and that all assistance to, and registration of, urban refugees and asylum seekers should end. The authorities said the plan responded to the recent attacks in Kenya, implying that urban refugees—and particularly Somali refugees—constituted a terror threat.

Although the relocation plan has been suspended pending a challenge in the courts, refugees and asylum seekers who faced police abuses after December 13 told Human Rights Watch that the police not only used the threat of arrest and prosecution on terror charges—calling them “terrorists”—but also the threat of prosecution for illegal presence in Nairobi due to their failure to move to the camps as an excuse to abuse and extort money from them.

On December 20, the government decided to form a committee made up of five government officials and five members drawn from the Eastleigh business community to investigate the grenade and IED attacks in various parts of Kenya, but not the police abuses that had taken place over the previous four weeks.[16]

Long-standing Pattern of Kenyan Law Enforcement Abuses Against Somali Kenyans and Somali Refugees

Human Rights Watch has reported on patterns of discrimination and mistreatment of Somali refugees and Somali Kenyans for many years, including in the 1980s and 1990s.[17] In the past few years, there have also been widespread and repeated abuses of members of these communities by the Kenyan police and military.

In 2009, Human Rights Watch reported on torture, rape, and other violence against Somali Kenyans in Kenya’s Mandera county in the North Eastern region committed by Kenyan security forces during a joint police-military operation between October 25, 2009 and 28, 2009 aimed at disarming warring militias in the Mandera area.[18] During the operation, the Kenyan army and police targeted 10 towns and villages, rounding up the population, beating and torturing male residents en masse, and carried out widespread looting and destruction of property. Members of the security forces raped women in their homes in at least some of the targeted communities while men were tortured in the streets. The operation left more than 1,200 injured, one dead, and at least a dozen women raped. To date, there has been no credible investigation or prosecution of individuals responsible for the abuses.

In June 2010, Human Rights Watch reported on widespread police abuses committed between 2008 and 2010 against Somali refugees in the Dadaab refugee camps in North Eastern region, including rape, beatings, extortion, arbitrary arrest, and detention. The authorities created a committee to look into the abuses but never published its findings and took no steps to prosecute police officers responsible.[19]

In May 2012, Human Rights Watch reported on abuses committed by security forces between November 2011 and March 2012 against Somali Kenyans and Somali refugees in North Eastern region, including rape, beatings, arbitrary detention, extortion, and looting.[20]The abuses occurred in the context of a Kenyan military and police response to attacks in North Eastern region by militants suspected of being linked to Al-Shabaab, the Somali Islamist armed movement.

During the operation, the Kenyan military and police arbitrarily rounded up large numbers of Somali Kenyans and Somali refugees in Garissa, Wajir, and Mandera, as well as in the Dadaab refugee camps. The abuses included rape and attempted sexual assault; beatings; arbitrary detention; extortion; the looting and destruction of property; and various forms of physical mistreatment and deliberate humiliation, such as forcing victims to sit in water, to roll on the ground in the sun, or to carry heavy loads for extended periods. The Kenyan military also detained scores of civilians, despite the fact that it had no legal authority to do so. Following public reporting of the abuses, the military established an ad hoc board of inquiry and initially appeared to be investigating the abuses, but to date no report has been published and none of the perpetrators of the abuses have been brought to justice.

II. Torture, Rape, Beatings, and Extortion by the Kenyan Police

The torture and other abuses documented in this report took place in homes, on streets, and in police stations between November 19, 2012 and late January 2013. Some took place in the context of security operations following grenade or bomb attacks in Eastleigh, such as the IED attack on a mini-bus on November 18, 2012 and the attack on December 8, 2012 on the Hidaya Mosque.

Victims of police abuse victims who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that the General Services Unit (GSU) committed the majority of these abuses. The Regular Police (RP) also committed serious abuses and arbitrarily detained and extorted money from hundreds of people in various police stations, according to interviewees who were taken to police stations and who saw what happened to others there. The Administration Police (AP) and the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) also committed abuses.

Rape, Other Forms of Sexual Assault, and Threats of Sexual Violence

‘You are a prostitute and you Somalis are all Al-Shabaab and terrorists.’

—A Somali refugee on what a female RP officer said to her just before two male RP officers raped her on January 18 in a police vehicle near Eastleigh’s 4th Street

‘We don’t respect your religion or culture. This is Kenya. We can rape you if we want to.’

—A Somali refugee on what GSU officers said to her on December 10, when she protested officers molesting Somali women in a GSU truck picking up Somalis and Ethiopians from the streets in Eastleigh

Reports of police rape of refugees and asylum seekers in Eastleigh after the November 18, 2012 bus attack first surfaced in late November.

Two Eastleigh-based social workers working with sexual violence survivors told Human Rights Watch that local women started to approach them on November 23 or thereabouts and reported that a day after the November 18 bus attack police entered apartment blocks throughout Eastleigh, particularly in Section 1 of the district near where the attack took place, and raped and beat women and girls in their apartments.

One of the two social workers informed MP Yusuf Hassan who in turn spoke with police representatives. The social workers said the number of rape reports decreased in late November but started to increase again during the second week of in December. The two social workers continued to receive reports about police rape in Eastleigh throughout December and January. One of the social workers told Human Rights Watch, “I could give you examples [of reported police rape cases] all day long.” [21]

The two social workers also said that almost none of the women who had been raped sought medical care, either because they thought they would have to pay for it and were unaware of free medical care provided by international NGOs in Eastleigh or because they feared their relatives and neighbors would find out they were raped. They also said none of the women reported the rapes to the police because they thought it would be pointless to inform the police that police had raped them. [22]

Almost all of the rape survivors told the two social workers that they were too afraid of police retaliation and community stigmatization to speak with Human Rights Watch about what had happened to them. However, seven survivors agreed to speak with Human Rights Watch and described in detail how police officers from the General Services Unit (GSU), the Regular Police (RP), or the Administration Police (AP) officers raped them and, in one case, three other women.

Some of the 10 rapes took place in apartments and others took place in alleys or on wasteland. Four of the attacks involved GSU officers, the two gang rape cases involved RP officers, and one case involved AP officers. Three attacks took place between November 19, 2012 and November 21, 2012, three during the first 10 days of December, and the seventh just before December 25.

A 23-year-old woman from Mogadishu living in Eastleigh since 2008 described how GSU officers raped her and three other women at night on wasteland near Eastleigh in early December. She said:

At around 8 p.m., lots of GSU came to the building where I was living on Jam Street and searched everyone’s apartment. Three of them came to my apartment and I showed them my refugee identity documents. But they took me to their truck nearby which was full of mostly Somali men and three women.

They drove us to a place where they told all the men to get out and then drove us four women to a different area. They told us to get out and forced us to walk through a field to a small building with a few rooms. They took each of us to a different room. Only one GSU officer entered the room with me. It was very dirty inside.

He told me to sit on the bed. Then he pulled me up by one wrist, slapped me, and ripped my dress. He took off his trousers and then he raped me. He held down one of my legs with his hand, pushing it to one side and against the wall. My leg still hurts, even now. I pleaded with him in Swahili to stop but he ignored me. I tried to struggle but he was too strong. While he raped me I could hear the other women shouting and then screaming and I knew they were also being raped.

When it was over, he left and immediately other GSU officers came in and took me to the truck. I was bleeding from my groin area and I used my headscarf as a pad.

Other GSU officers brought the other three women to the truck. Their dresses were ripped and they were totally silent. We didn’t have to say anything to each other because we all knew what had happened to all of us. They drove us to another place and just left us. We stopped a car which took us back to Eastleigh.[23]

Another Somali woman, aged 32 with six children who has lived on Eastleigh’s 4th Street since 2009, told Human Rights Watch how three RP officers gang raped her in her apartment on November 19:

Three police officers in dark clothes came to my apartment at night. My six children and I were all sleeping. I heard a loud knock on the door and opened it. They barged in and looked around, as if they wanted to search the apartment. I told all my children to go into the second room and I closed the door.

I showed them my UNHCR refugee letter and they asked me, ‘How will you bail yourself out?’ I said. ‘You are supposed to protect me.’ Then one of them slapped me and dragged me to the bed. All three of them slapped and beat me all over my body. They told me not to scream. They all took off their trousers and then one after the other they raped me. Two of them held me down while the other one raped and then they swapped around.

After the third one finished, they just left the apartment without saying anything. The neighbors came in and I was in tears on the bed. I just told the children they had beaten me, not what really happened to me.

Now I want to go back to Mogadishu because I am so afraid it will happen again, but I don’t have the money to go back. I know another three women who were raped by police officers that same night in the building I live in. They went back to Mogadishu because they were so afraid.[24]

A 22-year-old Somali woman who came to Kenya as a refugee in 1991 described how police raided her home and raped her on December 9:

At midnight, I was asleep with my children when two GSU officers came to my apartment. I showed them my refugee identity cards, but they tore both of them up and started beating, kicking and slapping me, shouting: ‘What are you doing here without a legal document?’

Then one of them took my children into the kitchen and closed the door. He then hit me on one of my shoulders with the butt of his rifle. The other man pushed me onto the bed, beat me, and tore off my clothes. Then he raped me. He put his hand over my mouth and held my neck tightly with his other hand. He was saying something in Swahili but I don’t know what. I could hardly breathe and my neck was swollen for many days afterwards.

The other man stood by the door. When it was over, they said nothing and just left. I didn’t go to a clinic because I don’t have money. I didn’t tell anyone about this because I was so ashamed. Of course I have not gone to the police to complain because they did this to me. [25]

Only one of the rape survivors Human Rights Watch spoke with said she had gone to a clinic. The others said they were either too afraid to speak to doctors about what happened or did not have enough money to pay for medical care. [26]

Five other women and one girl said GSU and RP officers sexually assaulted them, including by groping them, forcing them to take off clothes, and ripping off veils. One of the women said officers attacked about 10 other women with her. In two cases, officers threatened to rape women. Four of the cases involved GSU officers while the other two involved RP officers. [27]

A 38-year-old Somali woman with four children described how GSU officers sexually assaulted her and about 10 other Somali women in a truck the morning of December 10 on Eastleigh’s 2nd Avenue:

I was on my way to the market to sell food. There was a GSU truck parked in the street. Two GSU officers stopped me. I showed them my refugee ID and they threatened to take me to the police station if I didn’t give them money. When I said I didn’t have any, they put me in their truck. There were already 10 other women, all Somalis, in there.

Then a number of GSU officers grabbed us and touched us all over our bodies. I said our religion does not allow such behavior, but they said: ‘We don’t respect your religion or culture. This is Kenya. We can rape you if we want to.’ They drove us around in their truck and demanded a lot of money to let me go. I finally paid Ksh 15,000 ($181) and they let me go.[28]

Beatings, Kicking, Punching, and Slapping

They pushed me to the floor and kicked me all over my body, on the back of my neck, my hands, my sides and kidneys, my back and my legs. They wouldn’t stop and then I started spitting blood. My children were crying and pleaded with the police to stop.

—Somali refugee woman with two children on GSU officers’ violence against her in her home in Eastleigh, early January

Sixty-five Somalis and Ethiopians, many of whom were women, told Human Rights Watch that police officers seriously assaulted them in their homes, in the street, and in police stations between mid-November 2012 and late January 2013. Eighteen people also described witnessing police officers assault other people.

Nine people said police beat with them with truncheons, including two women and, in one case, officers beat three children. Almost all of the attacks happened by day in streets. [29]

A Somali woman working as a tea seller in Nairobi since 2006 with four children, aged 12 to 15, related how GSU attacked three of her children on December 2 while she and her eldest son were detained at Pangani police station:

I was in my home on 7th Street at around 10 a.m. with my four children and a friend who sometimes helps me in the apartment. About 20 GSU officers came to our building and entered lots of apartments, including mine. I showed them my and my son’s refugee ID cards but they ignored them. They told my eldest son and me to leave the apartment and when I refused they hit me very hard on the back of the head with a truncheon. Then some of them forced us out and other officers stayed behind in the apartment.

The GSU officers took us to their truck which was full of Somalis including many women, some of whom were breast-feeding their infants and crying. The GSU asked for money and took those of us who couldn’t pay to Pangani police station where they kept my son and me for two hours in cells packed full of Somalis and Ethiopians.

After a neighbor came and paid Ksh 10,000 ($120) to release us, my son and I went home and found my three children crying. They told me the GSU officers had beaten them with truncheons. My friend said she had tried to stop the beating but that the officers had slapped her and pushed her away. My children were in a lot of pain but I couldn’t take them to hospital because I didn’t even have enough money to pay my neighbor back the Ksh 10,000. [30]

Similarly, a 50-year-old Somali women told Human Rights Watch that in December 2012, two AP and two GSU officers seriously assaulted her with batons—including after she had collapsed onto the ground—when she tried to prevent them from taking her 17-year-old daughter away on 4th Street. More than two months later she said she was still in significant pain and was unable to sleep properly, while her daughter had fled to the Dadaab refugee camps out of fear of further police violence. [31]

A 32-year-old Ethiopian man living in Eastleigh since 2006, father of an eight-month-old child, described how GSU officers severely beat him with truncheons and punched him on Eastleigh’s Chai Road and in their truck at around 7 p.m. on December 20:

I was walking down Chai Road when a number of GSU officers stopped me. They told me my DRA refugee card was invalid and didn’t give it back to me. Then they accused me of being a member of Al-Qaeda and Al-Shabaab and said I had thrown a grenade at police. When I said they were wrong, they handcuffed me and then three of them beat me.

One of them beat me with a truncheon and one of the others with the butt of his rifle. The third one punched and slapped me. I fell to the ground and they kept on beating me. Then they put me in the back of their truck which already had lots of Somalis in it. Some of the GSU officers got into the truck and beat me and some of the Somalis. Then they searched my pockets, stole Ksh 8,000 ($96) and pushed me out of the truck.

Since they attacked me, I have been coughing and my kidney hurts a lot. I didn’t go to a clinic or hospital because I don’t have the money. If I go to the clinic, I won’t have money to buy bread and milk for my baby boy. [32]

Twenty-eight people, including 13 women and 6 children, told Human Rights Watch that police officers kicked and punched them. The attacks happened mainly in homes and on streets. [33]

Some of the attacks were particularly violent, causing serious injury and long-term pain.

A 33-year-old woman with a very husky voice she attributed to the attack described how GSU officers kicked her so hard in front of her two children, aged three and six, that she spit blood:

At the beginning of January, three GSU officers came to my apartment on 3rd Street at around 4 p.m. They tore up a copy of my UNHCR refugee letter and asked for the original. When I said I had lost it, they attacked me while my two children watched.

They pushed me to the floor and kicked me all over my body, on the back of my neck, my hands, my sides and kidneys, my back and my legs. They wouldn’t stop and then I started spitting blood. My children were crying and pleaded with the police to stop.

Then took my bag and took all the money I had in it, Ksh 10,000 ($120). I tried to get up and stop them but they dragged me by my ankles along the ground to their car and drove me around Eastleigh. When I asked whether they were taking me to a police station they slapped me. Some of my neighbors followed the police car and then paid the police Ksh 5,000 to release me.

Since the attack I have been sick. I have regularly vomited blood and my voice has changed. Since then I have hardly left home because I am so afraid of the police. [34]

A 23-year-old Somali woman from Mogadishu described how a number of AP officers came to her apartment on 7th Street in Eastleigh during the first week of December, told her she was causing insecurity in Kenya, beat her into unconsciousness, and then raped her. [35]

Similarly, in another case, witnesses said that GSU officers kicked a 12-year-old boy so violently he lost consciousness and then beat a Somali 26-year-old woman who witnessed the beating until she too fell unconscious. She was later raped by police. She described what happened:

It was 10 p.m. about two days after the bus bombing in Eastleigh on November 18 and I was in my apartment on 4th Street. Suddenly I heard lots of noise, so I went to the balcony and looked down and saw about 50 GSU officers in the compound. I saw them kicking and beating a young boy, about 12 years old. I ran down the stairs toward the police beating the boy and asked why they were beating him. One of them slapped me and I said: ‘You are not human beings.’ Then a second officer beat me twice very fiercely on the back of my head and my neck and I lost consciousness.

Later that night when I came to, my neighbors told me the GSU continued to kick and punch the boy until he lost consciousness. [36]

An Ethiopian man told Human Rights Watch that on December 21, two GSU officers came to his apartment, said they thought his refugee identity card was a fake and said they wanted money. When he said he did not have any, they attacked his wife, kicking her very forcefully in her sides. Later that day he said she started passing blood in her urine. [37]

A young Somali woman, aged 22, described how a number of RP officers came to her apartment in Eastleigh and pushed her infant out of her arms and onto the floor before mainly kicking her and also beating her with truncheons, causing long-term pain. [38]

Twenty-seven people, including 17 women, said police slapped them, including one case causing potentially permanent deafness and another two involving serious injuries due to recent medical operations. [39]

A 27-year-old Somali woman said that on November 27 or 28, three GSU officers stopped her on 4th Street as she was going to buy milk for the youngest of her six children, aged 11 months. When they ignored her DRA refugee card, demanded money and she refused, one of the GSU officers slapped her so hard on the left ear that she lost her hearing. She said the doctor she visited did not know whether the loss was temporary or permanent. [40]

Another Somali woman, aged 28, who has lived in Eastleigh since 1991, told Human Rights Watch that on December 15, five GSU officers entered her apartment and tore up her aunt’s refugee identity card in front of her. The woman said that her aunt had just had an ear operation and was speaking loudly because of temporary hearing loss, which the GSU might have thought meant she was shouting at them. One of the officers slapped her so hard on her ear that she fell over and started bleeding from the mouth. The police then stole a music system and left. [41]

Theft and Extortion

After that I closed my shop because there is no point in doing business if you are going to get robbed by the police.

—Ethiopian refugee on how he responded to police stealing Ksh 45,000 [$542] from his shop in Eastleigh on December 5, 2013

‘We are not looking for ID cards, we are looking for money.’

—Ethiopian asylum seeker on what GSU police told him on December 21, 2012 when they detained him at his apartment

Human Rights Watch documented 30 incidents in which interviewees claimed GSU or RP officers stole various items and large amounts of money from them while arbitrarily detaining them in their homes, in streets and in police stations.

Twenty-two people said GSU officers stole cell phones, jewelry, a music system and a total of Ksh 246,000 ($2,964). The average amount of money that witnesses said was stolen was just over Ksh 10,000 ($120), although in some cases witnesses claim GSU officers stole around 15,000. In three cases, the witnesses say officers stole Ksh 20,000 and in two further cases Ksh 35,000 and Ksh 50,000.

Nine people said RP officers stole cell phones, business materials, and a total of KS 37,000. The average amount stolen among interview subjects was Ksh 5,280 and the highest was Ksh 15,000.

Five people told Human Rights Watch that police officers stole money from them just after they had withdrawn funds from money transfer centers. [42]

Many refugees told Human Rights Watch they pleaded with the police not to steal from them. A 34-year-old Ethiopian refugee said he asked police demanding he pay Ksh 10,000 ($120) not to take his money because he would not be able to eat. He then asked police to give him back Ksh 1,000, after which the police assaulted him.[43]

Human Rights Watch also documented 80 incidents in which witnesses say GSU, RP or AP officers extorted money from them while threatening to prosecute them and their children on terrorism-related charges, move them to camps, or deport them to Somalia or Ethiopia.

In each case the witnesses say police released them when they paid, indicating that the sole purpose of detaining them was to extort money from them, not to investigate crimes or to enforce the government’s proposed plan to relocate refugees.

Interviewees described 48 incidents involving GSU officers who extorted a total of Ksh 335,000 ($4,036), or an average of just over Ksh 6,979 ($84) per incident. Twenty-five incidents described involved RP officers who extorted a total of Ksh 286,900, or an average of Ksh 11,476. In seven incidents AP officers extorted a total of Ksh 38,500, an average of Ksh 5,500.

Typical of dozens of incidents described by witnesses, a 21-year-old d Ethiopian asylum seeker, father of four who has been working as a tailor in Eastleigh since 2010, said:

One morning at the end of December, two Regular Police officers came to the shop where I work, told me my refugee identity card was invalid and took me to the Eastleigh Chief police station. They demanded I pay Ksh 10,000 ($120) and slapped me when I said I didn’t have money. Then they said, ‘If you don’t pay, we will take you to court as a terrorist. And if the court does not take the case, we will force you to the camps or will send you back to your country.’ After I paid, they released me. [44]

A 27-year-old Somali woman also described how police threatened her and dozens of other Somalis and Ethiopians with prosecution if they didn’t pay money:

It was a few days after the November 18 matatu [mini-bus] blast [in Eastleigh]. GSU officers came to my apartment and when I said I did not have my refugee Identity document because I had lost it, they took me to Pangani police station where the police asked for Ksh 50,000 ($602). When I said I had no money, they said they would charge me with belonging to al-Qaeda because I did not have a Kenyan ID card.

There were lots of Somalis and Ethiopians in the cells. Everyone who paid was released but those of us who didn’t had to stay. They kept on saying, ‘Give me 50,000 and you won’t go to court.’

They kept me in the police station all night and took me to Makadera court the next morning with about 20 other Somalis and Ethiopians. The judge said I and anyone else without a Kenyan identity card would be jailed for belonging to a terrorist group and that anyone who did have a Kenyan identity card would be freed if they paid Ksh 15,000 ($180). When we left the court room the police said, ‘If you pay you can leave – and if you don’t pay you will go to jail.’ My husband paid Ksh 31,400 and they let me go.[45]

The vast majority of Somali, Ethiopian and other refugees and asylum seekers in Eastleigh interviewed by Human Rights Watch say they have very little money or are destitute. Many work in menial jobs for very little pay with an average monthly income of around Ksh 8,000 – Ksh 9,500 ($96 - $114) a month, [46] making the sums stolen or extorted from them extremely serious. Many said they had to resort to borrowing money from others who could pay or collect money from the community.

Police Abuses as Torture

Under the Kenyan Constitution, which reflects key provisions of international human rights treaties to which Kenya is party including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,[47] all people in Kenya, including refugees and asylum seekers, are entitled to protection of their physical integrity, freedom from all forms of inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment, freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention, and protection from arbitrary interference with their property and privacy without discrimination on the grounds of national origin or any other status.[48]

Article 1 of the Convention against Torture defines torture as “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.”[49]

The evidence obtained by Human Rights Watch shows that between mid-November 2012 and late January 2013, police in Eastleigh who raped and seriously assaulted refugees and asylum seekers intentionally inflicted severe physical and mental pain or suffering while calling their victims terrorists and to extort money from them, thereby indicating the violence was punishment for attacks third persons committed in Eastleigh and to coerce them to pay money to the police to secure their release.

As a result, Kenyan public officials committed numerous acts of torture in Eastleigh during the abuses. On May 10, 2013, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Committee Against Torture with a summary of these findings and presented the findings orally in front of the Committee in Geneva on May 14. [50]

The Kenyan government has a legal obligation to carry out prompt and fair investigations into torture and prosecute and punish those military and civilian officials responsible.[51] All states party to the Convention against Torture are responsible for bringing torturers to justice.[52] A full investigation into torture should trace the origin of orders that led to the torture, be they from civilian or military commanders.[53] But the investigation should also determine command responsibility—that is, those who knew or should have known about the abuses—identifying those who were in a position of command yet failed to prevent the abuses or punish those responsible. The Committee Against Torture has stated that it “considers it essential that the responsibility of any superior officials, whether for direct instigation or encouragement of torture or ill-treatment or for consent or acquiescence therein, be fully investigated through competent, independent and impartial prosecutorial and judicial authorities.”[54]

III. Arbitrary Detention and Criminal Charges Without Evidence

Throughout the ten weeks of abuses in Eastleigh, police arbitrarily detained at least one thousand people in homes, streets, vehicles, and police stations, including in inhuman and degrading conditions. Police also falsely charged well over one hundred people—and possibly many more—with public order offenses, with no evidence of any kind to substantiate the charges.

Arbitrary Detention

There were dozens of Somalis and Ethiopians in the police station and they were all calling their relatives to come and pay so the police would release them.

—Ethiopian refugee on his detention in Pangani police station, Eastleigh, January 10

Almost every person Human Rights Watch interviewed described how police officers detained them and, in many cases, dozens of other people for hours or days simply because they initially refused to give in to police demands for money. Police failed to explain why they arrested them in their homes or in the street, and then detained them in police vehicles or police stations. All of the interviewees were released as soon as they had paid.

Kenyan and international law prohibit arbitrary detention. Kenyan law allows police officers to arrest and detain a person only if they have reasonable grounds for suspecting them of having committed an offense. [55] International law requires that anyone who is arrested shall be informed, at the time of arrest, of the reasons for their arrest and shall be promptly both informed of any charges against them and be brought before a judge. Detention before trial shall be the exception rather than rule and anyone in pre-trial detention is entitled to trial within a reasonable time or to release. [56]

In the cases documented, the Regular Police (RP) detained a total of about 300 people in a number of police stations, notably Eastleigh’s Pangani police station. A further 450 or so people were detained in vehicles, of whom 340 by General Services Unit (GSU) and 100 by RP officers. Fifty-seven people were detained in public places in various parts of Eastleigh, of whom 23 by GSU and 20 by Criminal Investigations Department (CID) officers. At least 212 were detained in their homes, mostly by GSU and smaller numbers by Administration Police (AP) and RP officers.

Detention in Police Stations

Fifteen people told Human Rights Watch how RP officers detained them in police stations in Eastleigh, including in six cases with dozens of others (a total of at least 300 people detained). Police held them for hours or days without giving them reasons for their arrest, without interviewing them, and without charging them with any offense. In one case, almost 100 people were held for three days before about 50 of them were released. Human Rights Watch was unable to establish when the remainder were released. [57]

Some of the cases followed police sweeps on November 19 and November 20, but most of them happened throughout late November, December, and January, indicating that arbitrary detention was not limited to specific sweeps following the bomb or grenade attacks in Eastleigh.

Based on the descriptions given by former detainees, the detention conditions in Pangani police station—where up to one hundred people were at times crammed for days into three very small police cells with one toilet between them—amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment.

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch of many cases in which they said police held people for days without informing them about offenses they might have been suspected of committing and the reason for their detention. For example, Human Rights Watch spoke with a young Somali Kenyan who was detained for days with almost 100 other people at Pangani police station the night of the November 18 bus attack before being taken to court on November 20. He said that at no point did police explain to him or dozens of others held with him in the cell why they were being detained and police interviewed none of them about suspected crimes. He said:

It was around midnight on November 18 and the GSU, RP, and AP all came to Alferdoos House apartment block in Eastleigh’s Section 1, about five minutes away from where the bus explosion happened earlier that day. They rounded up 28 of us, all young men, and took us to Pangani police station. There were already around 60 other Somali and Somali Kenyan men and children, some of them 12 or 13 years old, who told us they had just been brought there, like us.

They put all of us in three small cells, linked with one narrow corridor which had a filthy overflowing toilet at one end. The whole place stank of feces and urine. They forced me and around 30 others in one of the cells which was 3 meters by 3 meters and which did not have a window. We had no space to move. It was so full no one could even sit down.

The police kept insulting us, saying we were Al-Shabaab members and said, ‘Somalis are donkeys and have no rights in Kenya.’ They kept us in that cell all night, all next day, and the whole following night. The police did not interview us and on November 20 they took us to court.[58]

Detention in Police Vehicles

The largest number of documented arbitrary detention cases involved detention in police vehicles. Twenty-two people described how police detained them, together with around 430 others, in police trucks and cars, sometimes for hours on end, without giving any reason.[59] Numerous interviewees said police beat and kicked them and others in trucks. All said they were released after paying money.

Typical of these cases was a 35-year-old Ethiopian man with a bandaged hand who had been living in Eastleigh since 2006. He told Human Rights Watch how police detained him in a truck and assaulted him on December 21 or 22:

I was walking on 3rd Street to go home for lunch when four GSU officers stopped me. They took me to their truck nearby which was already full of Somalis and Ethiopians. They asked for my ID paper and I showed them my DRA card and UNHCR letter. Then they asked me for Ksh 5,000 ($60) and I said I had no money. They put me in the truck where they kept me for a long time. Then they searched my pockets and took all the money I had, KS 2,000, and my mobile phone.

When I tried to hold onto the phone, the officer trying to take it punched me in the left side of my face. Then they took me off the truck and a few of them beat me with the butts of their rifles, kicked me and stood on my right hand [bandaged]. They shouted, ’You are Al-Shabaab, go back to the camp.’ I went to a hospital and the doctor said one of the bones in my hand was broken. Even now, I still have very bad pain in my spine and in my hand. [60]

Detention in the Street

According to interviewees, police also arbitrarily detained dozens of people in Eastleigh’s streets as they went about their daily business. They described police detaining them and others in the street for as long as it took to arrange relatives and friends to come with enough money to secure their release. In some cases, police held them for as long as four hours. [61]

A 29-year-old Somali male described how AP officers stopped him on Eastleigh’s Jam Street at around 7 p.m. in late December and detained him until a friend had collected Ksh 20,000 ($140) to pay the police:

Three AP officers stopped me in the street and asked for my ID documents. When I showed them my UNHCR and Kenyan refugee documents, they told me they were fake and took them from me. Then they accused me of using drugs, and I said ‘If you suspect I’m using drugs, take me to prison and take me to the court so I can defend myself.’

Then they accused me of being an Al-Shabaab terrorist and asked me how much money I had with me. When I said I had no money, they told me they would take me to prison and court as a terrorist if I didn’t pay Ksh 20,000 ($240). They said if I refused and then changed my mind and wanted to pay them once I was in prison, the price would be Ksh 200,000 ($2400).

I called a friend and asked him to collect Ksh 20,000 for me. After some time, he came with the money and the police gave me back my ID documents and let me go.[62]

Detention in Homes

Between mid-November 2012 to the end of January 2013, Somalis, Ethiopians, and Somali Kenyans living in all parts of Eastleigh said they faced the constant threat of police raiding their homes and detaining them there for half an hour to a number of hours.

The raids created a profound sense of insecurity among victims, many of whom told Human Rights Watch they were living in constant fear of more raids and of being detained and abused in their homes. Most of the Somali and Ethiopian nationals said they were now considering leaving Kenya for good and that they knew other refugees and asylum seekers who had already left Kenya for the same reason.

Many of the raids took place at night and the interviewees said many involved serious police violence, including against women and children, [63] the use of teargas in enclosed spaces, [64] and the theft of personal property. During many of the raids, the witnesses said police made no distinction between men, women, and children and treated Somali Kenyans in the same way as they treated Somali and Ethiopian refugees and asylum seekers.

Forty-three people described incidents in which police detained them and others (a total of at least 200 people) in their homes. [65]

A pregnant 26-year-old Somali Kenyan woman living since 2006 in Eastleigh with her husband and her nine-month and two-year-old sons and 10-year-old daughter, told Human Rights Watch how on December 9, GSU police officers detained and assaulted her in her home:

It was around 9:30 a.m. when the GSU came and just broke down my front door. I could smell teargas. They grabbed my daughter by the wrist and told me to get our identity cards. Then they went into the bedroom and emptied the wardrobe. My husband was in Sudan at the time and had sent money to pay for rent and other things, so they found Ksh 50,000 ($602) in the wardrobe. They took all of it. I asked them why they were robbing me and they kicked me in the kidney. I was one-month pregnant at the time but I was lucky because the baby survived. My children were all very afraid and were coughing a lot because there was teargas in the building. Even now, months afterwards, they still have breathing problems.[66]

On December 8, at about 10 a.m., GSU officers detained a 20-year-old Somali Kenyan woman from Wajir in Kenya’s North Eastern region in her home in Eastleigh’s Section 3 and beat her brother. She said:

I was at home with my older brother and younger siblings when the police arrived. My brother said we should not worry because he thought the police would leave us alone as soon as we had shown them our Kenyan ID cards.

They knocked hard on our door and when we opened they barged in. Saying nothing, one of them grabbed my brother by the neck and six others beat him with batons on his head and back. When he fell to the floor, one of them stood on him. I have never seen people so violent.

I shouted, ‘We’re all Kenyan, why are you beating my brother?’ One of the officers grabbed my arm and twisted it. It felt like he was trying to break my arm. I told him I had Kenyan ID and that I spoke Swahili but he ignored me and shouted, ‘Go back to your country.’ I felt so bad, as if I were not even Kenyan.

The other officers went to the bedroom where I could hear them trying to break the locks on some of the cabinets. They also broke all the windows in our apartment.

The day after, my brother went to the Aga Khan Hospital, where he had to stay for two days before they let him go home. He still has kidney problems. [67]

Criminal Charges Without Evidence

At Pangani police station, the police asked me to pay Ksh 50,000 ($602). When I said I didn’t have any money, they said they would charge me with being a terrorist and take me to court.

—Somali woman, taken to court on false charges without evidence November 21

As part of the Eastleigh police raids, on at least one occasion, police rounded up dozens of Somali and Ethiopian nationals, as well as Somali Kenyans, and then arbitrarily arrested, detained, and falsely charged them with public order offenses, with no evidence of any kind to substantiate the charges.

Based on interviews with detainees and their lawyers, Human Rights Watch documented one case in which police subjected to this treatment 88 people: 84 Somali nationals, including 35 children who were detained in the same cells as adults, and four Somali Kenyan men. Each person in the group of eighty-seven paid between Ksh 100,000 ($1200) and 200,000 to be released on bail, with most securing their release five days after they were first arrested. On February 25, 2013, a magistrate’s court threw the case out for lack of evidence—with the police and prosecution repeatedly failing to produce a single piece of evidence or witnesses to substantiate the charges—and ordered the police to return the bail money. [68]

Lawyers for the accused also confirmed with Human Rights Watch that the 88 people were arrested in Eastleigh during the nights of November 18 and November 19 and that most said the police had broken into their homes and dragged them from their beds. At no point during their arrest did the police give any of the group reasons for their arrest or question them in relation to any suspected offense. [69]

In early February, Human Rights Watch interviewed two of the 88 people, a 26-year-old Somali man and a 20-year-old Somali Kenyan man. Both were living in the same apartment block close to where the bus explosion happened on November 18 in Eastleigh’s Section 1 and both were arbitrarily arrested and detained together with 28 other men from their apartment block the same night. The Somali Kenyan said:

It was 11:30 p.m., the same day as the explosion happened. I was in bed when I heard a lot of noise. I went to the door and saw large numbers of RP, AP, and GSU officers all over the apartment block. Five of the officers came into my room and told me my Kenyan ID card was invalid. When I asked them why, one of them slapped me and took to me to one of their trucks. Then they drove me and lots of other men from our apartment block to Pangani police station.

There were already around 50 other men and boys there—some as young as 12 or 13—who said the police had picked them up from a single apartment block that evening. Another seven said the police had picked them up from different places the same evening. The police didn’t tell any of us why they had brought us to the police station and they didn’t interview any of us in the police station about anything.

They kept us there until the morning of November 20 when they took all of us to court. At the court, the police said they were charging us with threatening to disrupt peace in Eastleigh’s Kamukunji area, participating in organized crime and extorting money from pedestrians. On January 22, they took us back to court and the court said it would release us on bail if we paid Ksh 100,000 ($1200] each. I used all my tuition fees and had to stop studying.[70]

Human Rights Watch also interviewed two others—Somali asylum seekers, one male and one female—about what appeared to be similar cases of false charges against them and others leading to days of arbitrary detention and an obligation to pay high bail amounts to secure their release.

One of these witnesses, a 21-year-old Somali man who came to Eastleigh in 2012, was arbitrarily arrested, assaulted, detained, and taken to court in January 2013 without ever finding out on what charges. He told Human Rights Watch:

On January 20 or 21, I was walking home from work on 7th Street, in section 1, at about 8 p.m. A few CID officers stopped me and a group of around 20 others in the area. They handcuffed all of us and made us sit on the ground.

Then they slapped and kicked us. They kicked me on my calves and in my sides and beat me on my shoulders. They didn’t say anything. They didn’t even ask us for money or for our ID documents. Then a few blue police cars took us to Pangani police station.

They held me there for two days. There were about 20 other people in my cell which was only about 3 x 3 m. There was one toilet which was filthy and the whole place stank. They only gave us ugali [maize meal] at lunch and we had to drink from the tap next to the filthy toilet.

They didn’t interview me once. Some of the other ones paid money to get released but the police said, ‘You younger ones, you have to go to court.’ On the third day they took a few of us to court. I have no idea why they took us to court, what the charge was. The judge just said we should each pay Ksh 70,000 KS ($843) to be released, but I still don’t know what for.

When I left the court room, the police told me if I paid Ksh 20,000 ($240) they would release me. My uncle was there and paid. The police then let me go and said I did not have to come back to court. [71]

IV. Kenya’s Refugee Relocation Plan

On December 13, 2012, Kenya’s Department of Refugee Affairs (DRA) announced that Kenya’s 55,000 registered urban refugees and asylum seekers were required to move to refugee camps in Kenya’s northeast and northwest and that all assistance to, and registration of, urban refugees and asylum seekers should end.

If carried out, the plan would be an unnecessary and disproportionate response to national security concerns and would breach various provisions of international refugee and human rights law. On January 21, 2013, a refugee charity and legal aid NGO in Nairobi, Kituo Cha Sheria, lodged a petition asking Kenya’s High Court to rule the proposed relocation plan unlawful. On January 23, the court ordered the government not to carry out the plan until the court had ruled on its legality. As this report went to print, the court was due to hear the case on May 22, 2013.

Despite the court’s order to put the plan on hold, the authorities continue to tell the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and aid agencies not to provide services to urban refugees and asylum seekers and the offices of the DRA, which registers them, remain formally closed. Asylum seekers in Nairobi and other cities are therefore unable to apply for asylum with the authorities and refugees are unable to renew their refugee identity cards, increasing the risk of arbitrary arrest and detention for unlawful presence in Kenya.

Kenya’s Urban Refugees

Under Kenya’s informal encampment policy, the overwhelming majority of Kenya’s mostly Somali refugee population has been forced to live for over two decades in closed refugee camps. Only very few refugees are allowed to leave the camps and temporarily move to other parts of Kenya, in violation of their right to free movement. [72]