“I Wanted to Lie Down and Die”

Trafficking and Torture of Eritreans in Sudan and Egypt

|

A Survivor’s Story The first group of kidnappers said I had to pay $3,500. They blindfolded all of us and chained our hands and legs together. They threatened to remove our organs if we didn’t pay. Even though my family paid, they didn’t release me but instead sold me to a second group. The second kidnappers said we had to pay them $33,000 because they had bought us from the first group, so we had to help them get their money back. They beat me with a metal rod. They dripped molten plastic onto my back. They beat the soles of my feet and then they forced me to stand for long periods of time, sometimes for days. Sometimes they threatened to kill me and put a gun to my head. They hung me from the ceiling so my legs couldn’t reach the floor and they gave me electric shocks. One person died after they hung him from the ceiling for 24 hours. We watched him die. Whenever I called my relatives to ask them to pay, they burnt me with a hot iron rod so I would scream on the phone. We could not protect the women in our room: they just took them out, raped them, and brought them back. They hardly let us sleep and I thought I was going to die but in the end a group of us managed to escape. Human Rights Watch interview, November 14, 2012, with a 23 year-old Eritrean man kidnapped by traffickers near Sudan’s Shagarab refugee camp in March 2012. These traffickers handed him over to Egyptian traffickers in southern Egypt, who held him in Sinai with 24 other men and eight women for six weeks. |

|

A Trafficker’s Story I buy Eritreans from other Bedouin near my village for about $10,000 each. So far I have bought about 100. I keep them in a small hut about 20 kilometers from where I live and I pay two men to stand guard. I torture them so their relatives pay me to let them go. When I started a year ago, I asked for $ 20,000 per person. Like everyone else I have increased the price. I know this money is haram [shameful], but I do it anyway. This year I made about $200,000 profit. The longest I held someone was seven months and the shortest was one month. The last group was four Eritreans and I tortured all of them. I got them to call their relatives and to ask them to pay $33,000 each. Sometimes I tortured them while they were on the phone so the relatives could hear them scream. I did to them what I do to everyone. I beat their legs and feet, and sometimes their stomachs and chest, with a wooden stick. I hang them upside down, sometimes for an hour. Three of them died because I beat them too hard. I released the one that paid. About two out of every 10 people I torture pay what I ask. Some pay less and I release them. Others die of the torture. Sometimes when the wounds get bad and I want them to torture them more, I treat their wounds with bandages and alcohol. I beat women but not children and I have not raped anyone. My parents don’t know I do this and I don’t want them to know. I’m not interested in speaking to anyone who wants me to stop doing this. The government doesn’t care so I don’t mind talking to you. The police won’t do anything to stop us because they know that if they come to our villages we will shoot. The military might try to get us, but I am young so I don’t think about that. I first started doing this because I had no money but saw others making lots of money this way. I know about 35 others who sell or torture Eritreans in Sinai. There are 15 just near my house, living close to each other. We are from different tribes. Some just buy them and sell them on to others, and some of us torture them to get even more money. Human Rights Watch interview with a 17 year-old trafficker near the town of Arish, Sinai, November 6, 2012 . |

|

A Witness’s Story When I see the detainees [former trafficking victims detained in Sinai police stations], I see burn marks on hands and arms, I see cigarette burn marks on their cheeks. Some have dislocated wrists and broken fingers. They tell me it is because the traffickers bend the wrists and fingers backwards and into other bad positions. In some cases I saw amputated fingers, usually the middle finger. Some have head injuries. Some can’t walk because the kidnappers tied them up for so long or beat them on the soles of their feet or legs and they need someone else’s help to stand. When I ask about the injuries, Eritreans always tell me what happened to them. Most women say the kidnappers raped them and they are ashamed. Some of them tell me only indirectly, for example by saying they missed their period. They tell me the traffickers gave them electric shocks, hung them from the ceiling by the hands, sometimes with their hands tied behind their backs, beat them all over their body, including their head. Many are obviously traumatized because of the torture. Many are dehydrated and have lost a lot of blood. The police don’t take people to hospital. Some detainees tell me the police refuse to take them and some say they saw other detainees die in the police station of their injuries. When I identify someone who is particularly badly injured I ask the police to take them to hospital. Sometimes they agree and sometimes they say no. And when I speak to doctors in the Arish hospital, some of them ask me why they should treat migrants who are trying to get to Israel where they will be turned into fighters and then attack Egypt. Confidential Human Rights Watch interview, November 7, 2012 . |

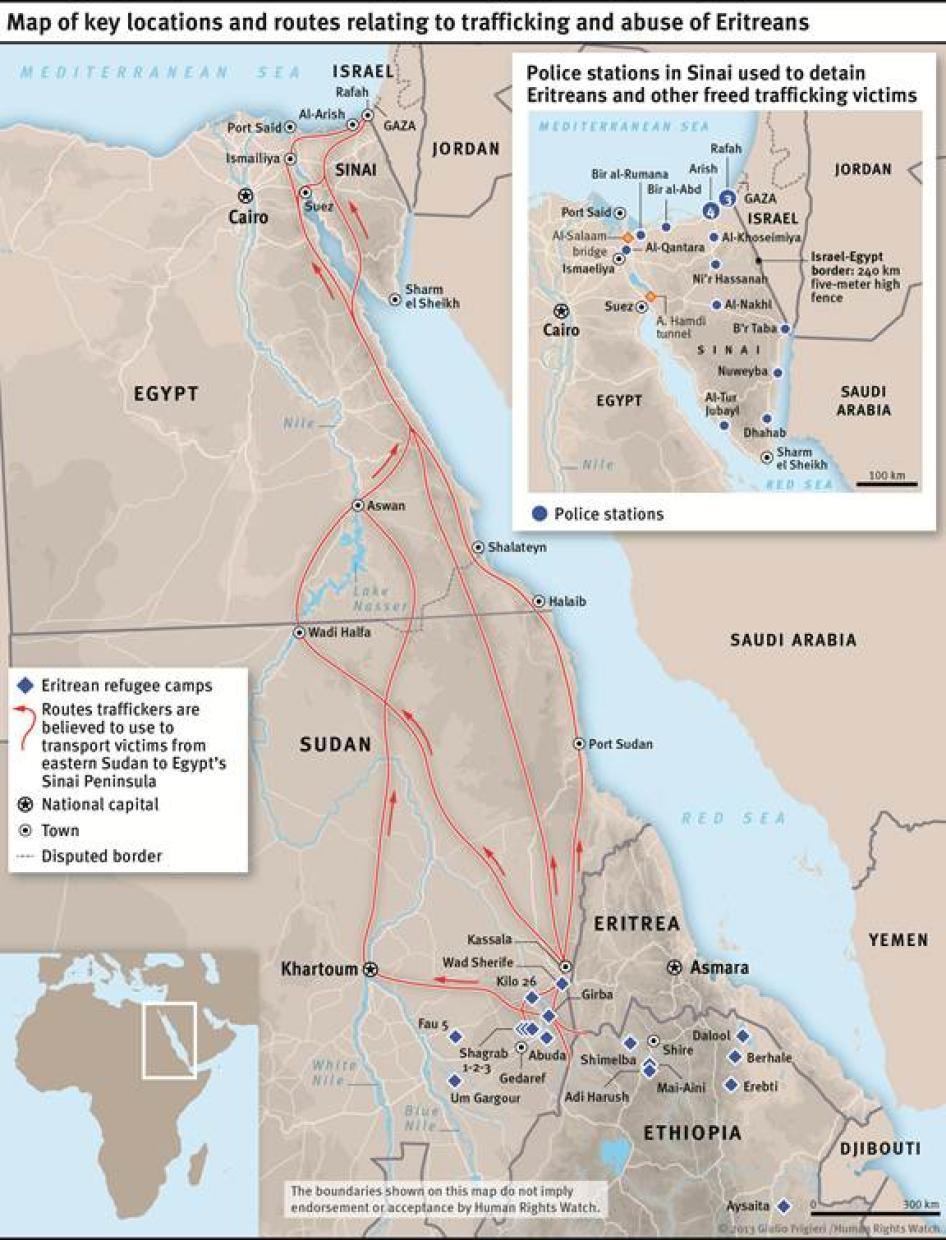

Map

Summary

To make us pay, they abused us. They raped women in front of us and left them naked. They hung us upside down. They beat and burnt us all over our bodies with cigarettes. My friend died in front of us and I wanted to lie down and die.

—Eritrean trafficking victim on the abuse he and others suffered at the hands of Egyptian traffickers in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula in early 2012.

We reached the checkpoint at the big bridge [at the Suez Canal] … and I saw three traffickers get out and speak to the police. They checked other cars, but not our truck. The traffickers got back in and we crossed the bridge.

— Eritrean trafficking victim on what he saw from underneath the canvass in the back of a pickup truck at Egypt’s only bridge for vehicles across the Suez Canal at al Qantara, July 2011.

Since 2006, tens of thousands of Eritreans fleeing widespread human rights abuses and destitution in their country have ended up in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Until 2010, they passed through Sinai voluntarily and generally without problems and crossed into Israel. But over the past three years, Sinai has increasingly represented a dead-end comprised of captivity, cruelty, torture, and death.

Since mid-2010, and as recently as November 2013, Sudanese traffickers have kidnapped Eritreans in eastern Sudan and sold them to Egyptian traffickers in Sinai who have subjected at least hundreds to horrific violence in order to extort large sums of money from the victims’ relatives.

A common technique traffickers use is to hold a mobile phone line open to their hostages’ relatives as they physically abuse their victims. The relatives hear the screams and the kidnappers demand the ransom for the victims’ release. Many Eritreans have told the UN, non-governmental refugee organizations, activists, and journalists of their experiences of rape, burning, mutilation and deformation of limbs, electric shocks, and other forms of violence.

The mutilated hands of an Eritrean trafficking victim who says traffickers in Sinai abused him, permanently injuring his hands, to force his relatives to pay tens of thousands of dollars for his release. Victims have described to Human Rights Watch the techniques traffickers in Sinai used to force them and relatives to pay ransom, including rape, burning, mutilation of limbs, prolonged suspension by the ankles or wrists, and giving electric shocks. © 2013 Moises Saman/Magnum

An Eritrean trafficking victim recovers from skin transplant surgery in Cairo, Egypt after traffickers in Sinai chained her ankles causing a severe infection. Trafficking victims have described to Human Rights Watch and other NGOs how traffickers chained them—often to one another—for months on end, while abusing them, including by raping women in front of other trafficking victims. © 2013 Moises Saman/Magnum

In some cases, these crimes are facilitated by collusion between traffickers and Sudanese and Egyptian police and the military who hand victims over to traffickers in police stations, turn a blind eye at checkpoints, and return escaped trafficking victims to traffickers.

The crimes described in this report constitute trafficking offenses under international law with criminals transporting, transferring, and harboring Eritreans by using force or the threat of force for the purpose of slavery.

Sudan’s very limited prosecutions of traffickers of Eritreans and other trafficking victims, and Egypt’s failure to investigate and prosecute traffickers, as described in this report, means both countries are breaching their obligations under national and international anti-trafficking laws, international human rights law, and national criminal law. These require the authorities to prevent and prosecute trafficking and to guarantee the right to life and physical integrity of everyone on its territory.

The authorities also have an obligation to investigate any official suspected of colluding with traffickers who inflict severe pain and suffering, failing which they are in breach of the UN Convention Against Torture. To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, Egypt has not prosecuted a single official for such collusion while Sudan only prosecuted four officials in 2012 and 2013.

According to the UN Committee on Torture, which reviews State compliance with the Convention, where state officials have “reasonable grounds to believe … that acts of torture or ill- treatment are being committed by … private actors” and “fail to exercise due diligence to prevent, investigate, prosecute and punish such … actors,” such that the state “facilitates and enables [traffickers] to commit acts impermissible under the [Torture] Convention with impunity,” the state then “bears responsibility and its officials should be considered as authors, complicit or otherwise responsible under the [Torture] Convention for consenting to or acquiescing in such impermissible acts.”

The extent of the readily-available evidence in the public realm about the widespread abuses committed in Sinai—as set out in this report—as well as detailed information about trafficker locations given to the Egyptian authorities, means Egyptian officials are therefore also responsible on numerous occasions for breaching Egypt’s obligations under the UN Convention Against Torture. Sudan’s limited prosecution of both traffickers and officials who collude with them means some Sudanese officials are similarly responsible for violations of Sudan’s responsibilities under the convention.

According to UN reports, Eritreans’ ordeal typically begins in or close to Africa’s oldest refugee camps in eastern Sudan, near the Eritrean border, sheltering about 75,000 mostly Muslim Eritreans who have lived there for decades.

Between 2004 and mid-2012, about 2,000 mostly Christian Tigrinya-speaking Eritrean refugees also registered in the camps each month after fleeing widespread rights abuses against Christian communities in their country, with the numbers dropping to an average of about 500 a month since then. But faced with life in remote, poorly serviced camps—with no access to work, no right to leave eastern Sudan, and surrounded by Muslim communities whose language they do not speak—they have moved on in search of protection, work, education, and other opportunities to restart their lives in safety and dignity. Some have travelled to Cairo and Khartoum, from where unknown numbers moved on to Libya and the European Union or to Djibouti, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia. Others have paid smugglers to take them to Israel via Sinai.

In 2010, the first reports surfaced of smugglers turning on their clients during the journey, kidnapping and abusing them to extort money from their relatives in exchange for onward travel. By 2011, Sudanese traffickers had started to kidnap Eritreans from inside or near the UN-run refugee camps near the town of Kassala in eastern Sudan and transferred them to Egyptian traffickers against their will.

In 2012, Eritreans told Human Rights Watch about the abuses they suffered in Sinai and about the collusion of Sudanese and Egyptian security forces with the traffickers. They said that in Kassala, Sudanese police and soldiers handed Eritreans over to traffickers, including at police stations. They also said that in Egypt, soldiers and police colluded with traffickers every step of the way: at checkpoints between the Sudanese border and the Suez Canal, at the heavily-policed canal or at checkpoints manning the only vehicle bridge crossing the canal, in traffickers’ houses, at checkpoints in Sinai’s towns, and close to the border with Israel.

An Eritrean trafficking victim recovers in Cairo in May 2013 from skin transplantation surgery to treat a severe ankle infection caused by the chains traffickers used to shackle her in Sinai. Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 trafficking victims about 29 incidents involving Sudanese and Egyptian security force collusion with traffickers who then tortured their victims. © 2013 Moises Saman/Magnum

In December 2013, Human Rights Watch spoke with an Eritrean activist who has spoken since 2010 by phone with hundreds of Eritreans held in Sinai, as well as with their relatives abroad who have been subjected to extortion. She told Human Rights Watch that after a lull in new reports of Eritreans being taken to Sinai in September and October 2013—which coincided with an increase in Egyptian military activity in Sinai against suspected Islamist armed groups—the calls started again in November and December 2013 from victims kidnapped and taken to Sinai in November.

Despite the overwhelming evidence of these abuses since 2010—documented in dozens of NGO reports and in extensive media coverage—Egyptian authorities have to the knowledge of Human Rights Watch taken no steps to end them. Senior officials in Sinai and Cairo either deny the abuses happen, or say Egypt’s public prosecutor is powerless to investigate such crimes without receiving names and locations of traffickers. In 2012 and 2013, Sudanese authorities prosecuted 14 cases involving traffickers in eastern Sudan. Egypt has prosecuted no officials for colluding with traffickers of Eritreans, while Sudan has prosecuted only four, in 2012 and 2013.

To make matters worse, Eritreans described how in 2011 and 2012 Egyptian border patrols continued their policy of shooting at escaped or released trafficking victims as they approach the 240-kilometer-long and five-meter-high steel fence that Israel almost completed in early 2013 along its border with Egypt. Egyptian border police killed at least 85 sub-Saharan nationals near the fence between July 2007 and September 2010.

When Egyptian border police intercept Eritreans, they transfer some to military or civilian prosecutors in Sinai’s main northern town of Arish, who order them to be detained in police stations in the city and elsewhere in North Sinai. They take others directly to the police stations. Eritreans are detained there for many months and are not allowed to challenge their detention. In breach of Egypt’s 60-year agreement with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), UNHCR is not allowed to visit the detainees, making it impossible for them to lodge refugee claims.

Egyptian authorities also deny trafficking victims their rights under Egypt’s Law on Combatting Human Trafficking to assistance, protection, and immunity from prosecution. Instead, they charge them with immigration offenses, deny them access to medical care, which means some torture victims die, and detain the survivors for months in inhumane and degrading conditions in Sinai’s police stations.

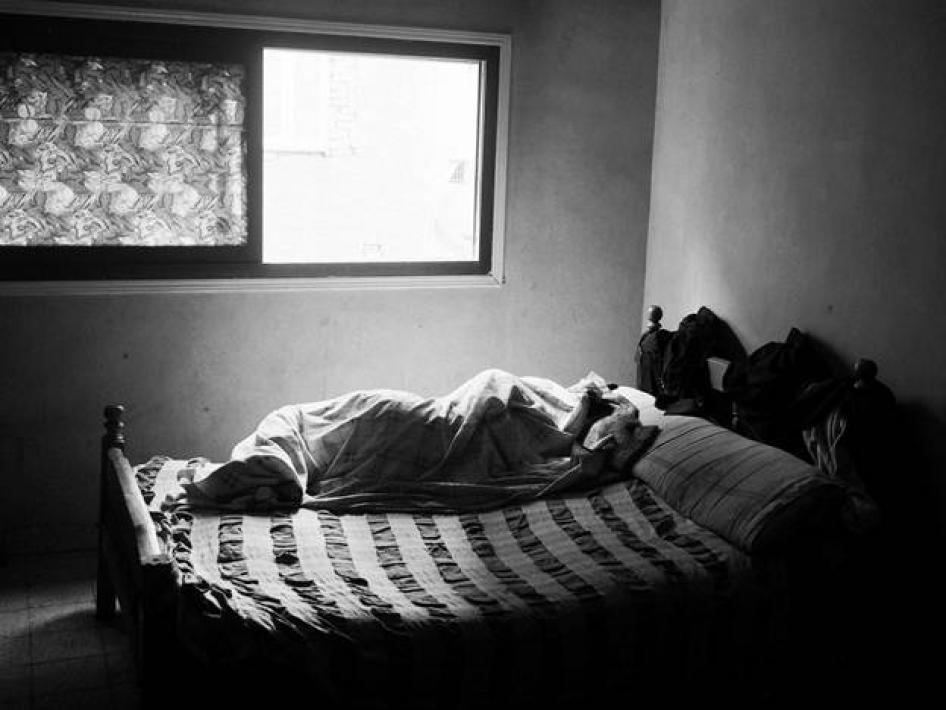

An Eritrean trafficking victim sleeps at a safe house in Cairo, Egypt on May 2, 2013. Some trafficking victims who escape from or are released by their captors in Sinai find their way to Bedouin community leaders who help them travel to Cairo where various NGOs help them. © 2013 Moises Saman/Magnum

According to Human Rights Watch interviews and the UN, the authorities only release them after the detainees purchase an air ticket to Ethiopia, under an arrangement between Egypt and Ethiopia, which allows Eritreans to fly from Cairo to Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa. Egyptian authorities in effect hold the trafficking victims hostage a second time, subjecting them to indefinite and arbitrary detention until their relatives can produce the money for the air ticket which secures their release and removal from Egypt.

Many of those sent back to Ethiopia come full circle, confined once again to the same closed refugee camps near Eritrea from where they made their way to Sudan and onwards to Sinai. As with Eritrean refugees in Sudan, most Eritrean refugees living in the camps in the Afar and Tigray regions of Ethiopia are not permitted to leave the camps to find work and live in poor conditions with limited opportunities to lead productive lives.

With no access to work in Khartoum and other Sudanese cities and facing widespread racism and destitution in Cairo and other Egyptian cities, Eritrean refugees’ options for building dignified and self-sufficient lives are shrinking. Anecdotal reports in 2013 suggest that since Israel effectively sealed its border with Sinai, new smuggling and trafficking routes from Ethiopia and Sudan have opened up to the west, taking increasing numbers of Eritreans on a treacherous journey across the Sahara desert to Libya, from where they hope to reach European countries, often on unseaworthy vessels.

In October 2013, UNHCR reported that some of the survivors of a boat tragedy in which 357 Eritreans drowned off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa on October 3, 2013, had previously registered as refugees in the eastern Sudanese and Ethiopian camps.

To end the horrific abuses committed against Eritreans in eastern Sudan and Egypt, both governments should launch a concerted law enforcement effort to identify and prosecute traffickers as well as Sudanese and Egyptian officials colluding with them. The Sudanese authorities should specifically investigate senior police officials responsible for collusion with traffickers in the town of Kassala and in the surrounding area, including the use of police stations to hand over Eritreans to traffickers.

As the Egyptian government bolsters its military presence and strengthens its law-enforcement capacity in North Sinai as part of counter-insurgency campaign there, it should include in law-enforcement operations the rescue of detained trafficking victims from captivity and the arrest and prosecution of the traffickers.

Egypt’s public prosecutor should launch an investigation into suspected trafficker locations in and around the town of Arish in north eastern Sinai, where the vast majority of traffickers are reported to be based, as well as at points of entry into Sinai and at the southern border with Sudan. Prosecutors should also investigate how traffickers have managed to bypass police and military checkpoints and how and why police and military authorities have allowed them to do so.

In line with Egypt’s anti-trafficking Law, Egyptian authorities should also immediately allow all trafficking victims no longer held by traffickers in Sinai to travel to Cairo, receive medical attention, and register with UNHCR if they are seeking international protection.

International donors to Egypt, including the United States, the European Union and its member states, as well as Norway, should press Sudan and Egypt to end security force collusion with traffickers in eastern Sudan and Egypt, and should urge Egypt to ensure that Egyptian military and police include shutting down trafficking networks among their law enforcement priorities in North Sinai.

R ecommendations

To the Government of Egypt

- Ensure that any military and law-enforcement operations in the Sinai include rescuing trafficking victims and arresting and prosecuting the traffickers responsible under Egypt’s 2010 Law on Combatting Human Trafficking.

- Investigate military and police collusion with traffickers and prosecute personnel who are responsible, including commanding officers; introduce a new law that criminalises official’s participation or complicity in torture, as defined under the UN Convention Against Torture.

- Protect and assist trafficking victims under Egypt’s Law on Combatting Human Trafficking, including by setting up witness protection programs and immunity from prosecution to encourage them to assist in investigations against their traffickers.

- Do not prosecute trafficking victims on immigration charges, do not detain them in police stations, and guarantee them access to UNHCR and other agencies in Cairo to receive protection and assistance, including medical and other care.

- Stop detaining Eritreans in inhuman and degrading conditions in Sinai to force them to agree to travel to Ethiopia.

- Order border guards to stop shooting at unarmed Eritreans and other unarmed asylum seekers and migrants near the Israeli border.

- Grant UNHCR access to all places where migrants are detained pending deportation to ensure asylum seekers among them can lodge asylum claims.

- Require the National Committee to Combat Human Trafficking to provide detailed updates every three months on steps taken by Egypt’s public prosecutor to investigate trafficking crimes in Sinai and security force collusion with traffickers.

To the Government of Sudan

- Investigate security force collusion with traffickers, particularly police commanders in Kassala, and prosecute personnel who are responsible; introduce a new law that criminalises official’s participation or complicity in torture, as defined under the UN Convention Against Torture.

- Investigate and prosecute people suspected of trafficking people in eastern Sudan.

- Urgently improve protection in the refugee camps near Kassala and in border areas to help prevent kidnapping and trafficking of Eritreans.

- Respect the right of all Eritrean and other refugees in Sudan to work and to move freely in Sudan.

- Encourage the National Assembly to swiftly pass anti-trafficking legislation that complies with Sudan’s human rights obligations and issue regular public reports documenting progress on prosecutions of traffickers and security officials who collude with them.

To the Government of Ethiopia

- Grant Eritrean and other refugees the right to move freely throughout Ethiopia and to look for work, without first requiring them to show they can sustain themselves financially.

To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- Regularly and publicly report on the number of known cases in which Eritreans and others are kidnapped by traffickers in eastern Sudan, including a breakdown of locations.

- Encourage Sudan to investigate and prosecute trafficking suspects in eastern Sudan, as well as Sudanese police and military colluding with traffickers; encourage donors to call on Sudan to do the same.

- Call publicly on Egypt to allow UNHCR to access all places where migrants are being detained pending their deportation to ensure asylum seekers among them can lodge asylum claims, including in Sinai.

To the League of Arab States and the African Union

- Call on Egypt and Sudan to investigate and prosecute security officials colluding with traffickers and to investigate and prosecute traffickers.

- Call on Egypt to give trafficking victims the assistance and protection to which they are entitled under Egypt’s Law on Combatting Human Trafficking, including immunity from prosecution for immigration offenses, and allow them to register as asylum seekers with UNHCR.

To Donor Governments P roviding Support to UNHCR, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan

- Press the Egyptian and Sudanese authorities to investigate and prosecute traffickers responsible for the abuses documented in this report and to hold accountable security officials who facilitate these abuses.

- Press Egypt to give trafficking victims the assistance and protection to which they are entitled under Egypt’s Law on Combatting Human Trafficking, including immunity from prosecution for immigration offenses, and allow them to register as asylum seekers with UNHCR.

- To help prevent Eritreans from having to move on from their first country of refuge, press Ethiopia and Sudan to guarantee all refugees’ right to freedom of movement and the right to work.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in Cairo and Sinai, Egypt between November 3 and 14, 2012 and in Tel Aviv, Israel between November 15 and 20, 2012. A Human Rights Watch researcher conducted in-depth individual interviews with 32 Eritrean, two Ethiopian, and three Sudanese nationals. There were 32 men and five women. Among them, 16 were registered refugees and asylum seekers in Cairo and 20 were lawfully present in Israel under its non-deportation policy for Eritrean and Sudanese nationals not registered as asylum seekers in Tel Aviv.

Human Rights Watch worked with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Cairo and Tel Aviv to identify interviewees who had witnessed Egyptian and Sudanese security force collusion with criminals in Sudan and Egypt who had trafficked and otherwise abused them between 2009 and 2012. Interviews were conducted individually in private confidential settings, and lasted an average of 40 minutes.

Human Rights Watch staff explained the purpose of the interviews, gave assurances of anonymity, and explained to interviewees they would not receive any monetary or other incentives for speaking with Human Rights Watch. We also received interviewees’ consent to describe their experiences after informing them that they could terminate the interview at any point. Individual names and other identifying details have been removed to protect their identity and security.

All interviews were conducted in Tigrinya and Arabic, using interpreters. Whenever interviewees referred to police or soldiers colluding with traffickers, interviewers asked the interviewees to describe the uniform the individual was wearing to help distinguish between the police and military.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed the transcripts of 22 detailed interviews with Eritreans conducted by an NGO in Egypt relating to trafficker abuses and Sudanese security forces collusion with traffickers.

Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with two self-confessed traffickers, one of whom spoke about abusing his victims. Human Rights Watch identified them through a local contact in Sinai who knew them well. The two traffickers told Human Rights Watch they were willing to speak about their criminal activities because they were not afraid of any repercussions by Egyptian law enforcement.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed three Egyptian officials, 13 NGO and international humanitarian staff and four foreign embassy staff in Cairo. The three Egyptian officials are Naela Gabr, the head of Egypt’s National Coordinating Committee on Combating and Preventing Human Trafficking; the secretary general of the North Sinai Governorate, Major General Jaber al-Arabi; and a judicial official in Sinai who preferred to remain anonymous.

Human Rights Watch was unable to travel to or conduct interviews in Sudan. The Sudanese government has repeatedly denied visas to international human rights organisations and has effectively closed the country to human rights monitoring. The Sudanese authorities have publicly acknowledged the widespread trafficking of Eritreans in and out of eastern Sudan.

I. Background

Fleeing Eritrea

By early 2013, 300,000 Eritrean refugees and asylum seekers lived in Sudan, Ethiopia, Israel, and Europe, with about 90 percent of Eritrean asylum seekers successfully claiming asylum in recent years.[1] The vast majority left their country after mid-2004, fleeing widespread human rights violations, including mass long-term or indefinite forced conscription and forced labor, extra-judicial killings, disappearances, torture and inhuman and degrading treatment, arbitrary arrest and detention, and restrictions on freedom of expression, conscience and movement. Almost all of the arrivals since mid-2004 are Christians, reflecting increased abuses against that community since 2002.[2]

Those fleeing Eritrea take serious risks. Eritrean law requires Eritreans leaving the country to hold an exit permit which the authorities only issue selectively, severely punishing those caught trying to leave without one.[3] When Eritreans succeed in leaving the country without permits, the authorities often punish their relatives.[4] Border guards have shoot-to-kill orders against people leaving without permits.[5] In this environment, the smuggling and trafficking of Eritreans to Sudan has flourished. The UN has documented some Eritrean officials’ collusion with abusive Sudanese traffickers in eastern Sudan.[6]

Eritrean Refugees in the Horn of Africa and Egypt

Over the past ten years, about 130,000 Eritreans have registered as refugees in eastern Sudan’s refugee camps and tens of thousands more have registered in Ethiopia’s camps. Unknown further numbers have passed through eastern Sudan and Ethiopia without registering as refugees.

Most who register do not stay long in eastern Sudan’s camps. After unsuccessfully searching for protection, assistance and work, they move on in search of security and better opportunities. Between 2006 and 2012, close to 40,000 arrived in Israel, passing through Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Unknown numbers traveled to Saudi Arabia through Djibouti and Yemen and others attempted to reach European countries through Libya.

In October 2013, UNHCR reported that some of the survivors of a boat tragedy in which 357 Eritreans drowned off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa on October 3, 2013, had previously registered as refugees in eastern Sudan and Ethiopia.[7]

Refugee Camps in Eastern Sudan

Since the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Eritreans have fled their country to Africa’s oldest refugee camps, in eastern Sudan. [8] As of October 30, 2013, the camps sheltered 86, 087 Eritreans. [9] Of this number, about 50,000 are Arabic speaking Muslims—from the same community as those living near the camps—who arrived in the camps between 1960 and 2000 and are unlikely to return to Eritrea. [10] UNHCR is working with the Sudanese authorities to permanently integrate this population into eastern Sudanese communities. [11]

After a four year pause in the Eritrean exodus, Eritreans once again started to flee their country in large numbers in mid-2004 with 129,957 registering in the camps between January 1, 2005 and October 31, 2013. [12] Almost all moved on within weeks or months. [13]

Their reluctance to remain in the camps could be explained by a number of factors. The vast majority of those registering have been young Christian men from urban areas unwilling to become dependent on aid agencies in remote rural locations surrounded by Arabic-speaking and Muslim communities. [14] They have limited work rights and opportunities. [15] They also face tight restrictions on freedom of movement. [16] The restrictions are unlawful. [17] The policy has left them with little alternative but to rely on smugglers to move outside eastern Sudan, which in turn exposes them to the risk of kidnapping by traffickers.

Sudan also has a track record of deporting Eritrean asylum seekers, and Eritreans denied access to asylum, back to Eritrea. Between January and May 2013 , Sudan deported at least eight Eritreans to Eritrea. In 2012, Sudan deported at least 68 Eritreans to Eritrea, including registered asylum seekers who were deported just after they had appealed against a refusal to grant them asylum. [18] In October 2011, Sudan deported 300 Eritrean asylum seekers and others unable to claim asylum, and deported dozens more in the five months before that. [19]

The number of people registering in the camps declined drastically in May 2012 from a previous monthly average since January 2009 of about 2,000 to a few hundred each month, a trend that continued for the rest of 2012 and the first ten months of 2013. [20]

To date, none of the agencies working in eastern Sudan, including UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration, have been able to explain the post-May 2012 decrease.[21] Two possible explanations are that fewer Eritreans reach the camps because they fear being kidnapped by traffickers and therefore avoid eastern Sudan entirely, or because an increasing number are kidnapped as soon as they cross the border before they have a chance to reach the camps.[22] Other Eritreans—it is not known how many—have passed through eastern Sudan since 2004, but never registered in the camps, moving on to Khartoum or other countries.[23]

Refugee Camps in Ethiopia

Eritreans have also fled in the tens of thousands to refugee camps in Ethiopia where they face “a harsh life in … arid … landscape which offers very little opportunities for self-reliance.”[24] Refugees are generally not allowed to leave the camps to move freely in Ethiopia, in violation of their free movement rights.[25] In 2008, Ethiopia introduced an “out of camp” policy under which Eritrean refugees may only leave camps after six months to live in urban areas if they can show they can financially support themselves or if any relatives already living in such areas can support them.[26] Refugees may also apply for a permit to temporarily leave the camps, mostly for medical reasons.[27]

Refugees in Ethiopia are only allowed to work and access education insofar as Ethiopia’s laws allows other foreign nationals in Ethiopia to do so. [28] Eritreans find it very hard to find informal work in Addis Ababa and other major cities, a fact underscored by the tens of thousands of Ethiopians who leave their country every year in search of work. [29]

Some Eritrean refugees leave Ethiopia’s refugee camps and risk their lives crossing the Mediterranean to Europe or move on to the refugee camps in Sudan in the mistaken belief they will find better assistance or work opportunities there only to find the opposite is true.[30] As noted below, over the past few years Egypt has deported thousands of Eritreans intercepted in Sinai to Ethiopia. For those whose journey started in the Ethiopian refugee camps, they come full circle.

Eritreans in Cairo

Some Eritreans end up in Egypt, which does not have any refugee camps. Many registered and unregistered Eritrean refugees and asylum seekers live in the Ard al-Liwa suburb of Cairo.[31] Egypt restricts refugees’ rights to education, social security, and work rights.[32] Refugees and asylum seekers of all nationalities have long struggled to survive in Cairo’s informal economy and to access health care.[33] Christian Eritreans, who generally do not speak Arabic, have few opportunities to make a life in an Arabic-speaking and majority Muslim country with high poverty levels and fierce competition in the informal economy.[34]

According to NGOs working with refugees in Cairo, the few Eritreans who have lodged asylum claims and live in Cairo do so because they already have relatives in the city who can support them. [35] A number of Eritreans who spoke with Human Rights Watch, including those who had already been kidnapped and abused in Sinai, said they feared criminals in Cairo would kidnap them and take them to Sinai. One man described in detail how Bedouin kidnapped and tortured him near Cairo to discover the whereabouts of six other Eritreans the kidnappers wanted to find. [36] Cairo-based refugee organizations also told Human Rights Watch that many of their Eritrean refugee clients in Cairo said they feared kidnappers, and that many tried to stay indoors at all times. [37] One of the organizations said it knew of two cases in which criminals had kidnapped Eritreans in Cairo. [38]

II. Trafficking of Eritreans in Sudan

Beginning in 2006, thousands of Eritreans paid Sudanese and Egyptian smugglers to help them travel from eastern Sudan to Israel via Egypt. In 2009, Eritreans started to report to the UN and non-governmental refugee organizations how smugglers turned on them during the journey, kidnapping and then holding them to ransom. By 2011, smuggling had changed into widespread kidnapping by traffickers of mostly Eritreans from eastern Sudan’s refugee camps and the nearby border areas with Eritrea. Sudanese traffickers abuse and torture their victims to extort money from them or their families, and then transport them to Egypt where they are handed over to Egyptian traffickers.

The Shift from Smuggling to Trafficking in Eastern Sudan

In 2006, Eritreans started to pay smugglers to take them from eastern Sudan to Israel. In mid-2010, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Israeli NGOs began receiving reports that smugglers in Sudan, who had been taking mostly Eritreans to Israel since 2006, had started to turn on their clients before and during the journey to Sinai and abused them to extort additional money from them.[39] The smugglers thereby became traffickers, according to the international legal definition.[40]

By the end of 2010, increasing numbers of Eritreans started reporting that they had had no intention of travelling to Egypt or Israel but had been kidnapped in eastern Sudan and taken to Sinai against their will.[41]

An Eritrean man told Human Rights Watch that he and other Eritreans were kidnapped in eastern Sudan in early 2009, while another said he was kidnapped in June 2010. [42] A few Eritreans also told refugee social workers in Cairo that they were kidnapped in the spring of 2010. [43]

Human Rights Watch spoke with 21 Eritreans in Cairo and Tel Aviv who described how they were kidnapped in eastern Sudan in 2011, and reviewed 14 statements taken by refugee organizations in Cairo in which Eritreans said the same. [44]

A community leader in Sinai working with Eritreans released by traffickers in Sinai told Human Rights Watch that in the second half of 2012 a majority of them said they were originally kidnapped in Sudan and taken to Egypt against their will. [45]

In 2011, UNHCR received increasing reports of kidnapping in and around eastern Sudan’s Kassala refugee camps and in 2012, UNHCR recorded about 30 kidnapping cases a month, although it estimated that the number was much higher.[46]

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Antonio Gutteres first publicly highlighted in January 2012 the kidnapping and trafficking of Eritreans in eastern Sudan for the purpose of transfer to Egyptian traffickers.[47]

In January 2013, UNHCR issued a press statement following violence in one of the camps triggered by traffickers kidnapping Eritreans from inside the camp. The statement said UNHCR’s staff had documented kidnapping incidents since early 2011 and that such incidents were on the increase. UNHCR said, “Local tribesmen … as well as some criminal gangs” were “kidnapping …. Eritreans … at the border … as they enter eastern Sudan” and from “in and around the camps” before taking them against their will to Egypt.[48]

Kidnapping, Abuse and Torture of Trafficking Victims in Eastern Sudan

Human Rights Watch spoke with 21 Eritreans who said people they described as “Rashaida” kidnapped them and dozens of others, mostly Eritreans, in eastern Sudan near the Eritrean border and refugee camps near the town of Kassala. [49]

They said the traffickers detained them for days or weeks near Kassala, abused them to extort money from them, and then handed them over to kidnappers in Egypt. Seven said they were kidnapped in 2012, twelve in 2011, one in 2010, and one in 2009.

Eighteen of those interviewed said the traffickers demanded they pay from a few thousand dollars to as much as $10,000 in ransom. Whether they paid or not, all of those interviewed said that the traffickers then transferred them to other men in Egypt who also demanded payment.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed the transcripts of 14 detailed interviews taken by an NGO in Egypt in which Eritreans said “Rashaida” kidnapped them in Sudan near the Eritrean border or the town of Kassala and transferred them to traffickers in Egypt. Six said they were kidnapped in 2012, five in 2011, and three in 2010. [50]

Thirteen of the 35 Eritrean cases that Human Rights Watch interviewed or reviewed said that the Sudanese traffickers repeatedly beat and assaulted them in other ways, of whom three said the traffickers severely abused them and three said the traffickers threatened to kill them if they did not pay. One said that traffickers in Khartoum raped her and other female victims. [51]

Human Rights Watch documented eight cases in which Sudanese police and Sudanese military handed Eritreans directly to traffickers who then abused them. [52]

A 33-year-old Eritrean man from Murki in Eritrea’s Gashbarka region, told Human Rights Watch he fled Eritrea and crossed at night to Sudan near Hafira in September 2011. There he met a farmer who let him stay the night and said he knew people who could help him go to the Kassala refugee camps.

The next day five men in civilian clothes with guns arrived and drove me away. They tied my hands together and beat me. They held me for two months with little food or water. They asked me whether I had relatives in Israel or the United States and told me to call my relatives and ask them to pay $4,000 to have me freed.

They handcuffed me to a bed. Many times four men beat me with wooden sticks on my hands and legs, on my buttocks and on the soles of my feet. Sometimes they whipped me with an electric cable and they often slapped me. After two months they transferred me to other kidnappers who drove me in a large group to Sinai.[53]

An Eritrean boy from Zoba Dobab, age 17, told Human Rights Watch that he fled Eritrea on April 3, 2012, and that local Sudanese people from the Hadarib tribe stopped him and handed him over to “Rashaida.” [54] He said:

They held me for two weeks in the desert with 155 other Eritreans. They said they would shoot me if I didn’t pay $2,000. They beat some of the others to force them to pay the same. Next door to where they held me there were women who often screamed and I thought they were being raped.[55]

In one of the detailed statements Human Rights Watch reviewed, a 15-year-old boy who escaped from his kidnappers at the end of December 2011 said that a second group of “Rashaida” kidnapped and then tortured him and other kidnap victims:

They tied our hands and legs and blindfolded us. Then said they would kill us with knives or guns if we didn’t pay $10,000 and asked us whether we had relatives abroad who could pay. They beat us a lot with metal rods. They poured petrol over us and made us drink water with petrol in it. When we vomited they forced us to drink the vomit. They burned us with cigarettes and we had to stand most of the time.[56]

Transfer to Egyptian Traffickers

|

I am 30 years old and newly married. I started trading in Africans in 2009. I only buy and sell them for profit. I don’t torture them because that is shameful [haram]. The last group I bought and sold was three months ago. I buy the Africans from tribes around Aswan. They tell me they buy them from people in Sudan. I use the hawala [money transfer system] to pay the people in Aswan. When I started in 2009, I paid $100 per person, but this year I had to pay up to $600 per person. This year I have been selling them to other Bedouin here in Sinai for $5,000 a person, usually after holding them for a week or two. In 2010 and 2011, I used to buy around five migrants per day, six days a week, so around 1,500 a year. Until September this year [2012], it was about twice that number. The people in Sudan tell the tribes around Aswan that during the Egyptian revolution [which started in January 2011] it was even easier than before to cross the Sudan-Egyptian border without any checks. The police and military don’t come to stop the traders and the torture because they are afraid of losing too many people if the traders shoot at them. Human Rights Watch interview with Bedouin trafficker an hour and a half from Arish, north eastern Sinai, November 5, 2012. |

All Eritreans Human Rights Watch interviewed said that once they had given in to Sudanese traffickers’ demands for money and paid, the traffickers transferred them to Egyptian traffickers. Interviewees were unable to say where the transfers happened. In some cases, they said they were transferred four or five times before they reached Sinai. [57]

Eighteen of the Eritreans who spoke with Human Rights Watch said they drove for days through desert, sometimes on roads and sometimes on small paths, and that they generally did not see police or military until they reached either the Nile or the Suez Canal in Egypt. Some said the traffickers forced them to lie down under plastic sheeting in the back of the pickup trucks. Others said they were allowed to sit upright in plain sight.

Two Eritreans in Cairo with good knowledge of the route from eastern Sudan to Aswan in southern Egypt said that moving Eritreans in trucks between those two points was generally quite easy because the traffickers could drive through the desert to avoid checkpoints.[58]

Sudanese Security Force Collusion with Traffickers in Eastern Sudan

Trafficking victims described several cases to Human Rights Watch in which Sudanese police and soldiers arbitrarily detained Eritreans and handed them over to traffickers.

In 13 of the cases documented or reviewed by Human Rights Watch, the Eritreans said that Sudanese police detained them in 2011 or 2012 and then handed them over to traffickers. Eight of them said that the handover to the traffickers happened inside or just outside a police station in Kassala town. Another said that he saw the police allow the traffickers who were transporting him in 2012 to pass through their checkpoints.[59]

Two Eritreans also said Sudanese soldiers detained them and handed them over to traffickers. One case took place in 2011, the other in 2012.[60]

A 28-year-old Eritrean man from Wakikant in Eritrea’s central highlands who escaped from Eritrea in November 2011 told Human Rights Watch that one hour after he reached Kassala police stopped him and took him to a police station, took all his money, and put him in a cell. The police then handed him over to traffickers:

They asked me whether I had relatives abroad and I said no. The next morning, the police opened the door and there were two Rashaida standing next to them in the doorway looking at me. I speak a little Arabic so I heard a little of what they said. One of the Rashaida asked one of the policemen, “Do these men have families who can pay us?” and he said, “Yes.” The next day the police took us to a car parked outside the police station. The same two Rashaida were in the car. The police told me to get into the car and the Rashaida drove me to the desert about an hour away.[61]

A 26-year-old Eritrean man who fled to Sudan in February 2012 described how police handed him over to traffickers:

Shortly after I crossed into Sudan, two policemen in blue uniforms caught me near Wadi Sherifeh and took me to a police station where they kept me and another Eritrean man from around 6 p.m. to midnight. One of them spoke Tigrinya and told me the police would take me to a nearby refugee camp. Then two policemen drove the two of us for around one and a half hours until we met a pickup truck with four Rashaida in it. They hit us with an iron bar and put us in the back of the pickup and covered us with a big plastic sheet. I then heard them talking with the police for half an hour and then we left and they drove us to a house where they held us for a night before taking us to Egypt.[62]

A 16-year-old boy from Zerejeka, near Asmara, described how Sudanese police handed him to kidnappers in March 2012:

I left Eritrea for Sudan in February or March 2012 with two men. We walked from the Eritrean border to a police station in Kassala because I had heard in Eritrea that the Rashaida in Sudan were kidnapping people near Kassala and the camps and I wanted the police to protect me. The police said, ‘Welcome, welcome,’ and three of them got in a car with us and said they would take us to Shagrab refugee camp. We drove for 15 minutes to a house and they gave us bread and cheese and told us to rest. One of the policemen was on the phone all the time and half an hour later a car arrived with three Rashaida in it. They put us in their car and drove us away. Then they took us to Sinai.[63]

In 2011, Eritrean asylum seekers in Israel told the Hotline for Migrant Workers, an Israeli NGO, about Sudanese military collusion with traffickers. [64] Eritreans also told researchers in 2013 about such cases. [65]

In June 2013, the US State Department reported that “the [Sudanese] government did not report investigating or prosecuting public officials allegedly complicit in human trafficking, despite reports that Sudanese police sold Eritreans to the Rashaida along the border with Eritrea.” [66]

III. Trafficking of Eritreans in Egypt

Since 2010, Eritreans—and to a far lesser extent, Ethiopians—have suffered horrific abuses at the hands of Egyptian traffickers in Sinai which have been widely publicized through NGO reports and international media coverage, as well in some Egyptian media. In late 2012, Eritreans described incidents to Human Rights Watch in which Egyptian police and military colluded with the traffickers, including at the heavily policed Suez Canal which traffickers must cross to reach Sinai. In November 2012, Human Rights Watch also spoke to Naela Gabr, the head of Egypt’s National Coordinating Committee on Combating and Preventing Human Trafficking (anti-trafficking committee), who acknowledged that trafficking abuses were taking place in the Sinai.

UNHCR says it interviewed trafficking victims abused in Sinai in 2013. In December 2013 and January 2014, Human Rights Watch received new reports of kidnapping in eastern Sudan and trafficking in Sinai that took place between November 2013 and January 2014.

Trafficker Abuses in Sinai

Since mid-2010, the UN, Human Rights Watch and other international NGOs, as well as international and Egyptian media, have reported on abuses committed by traffickers against mostly Eritreans in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. The traffickers abuse their victims to extort money from their relatives in Eritrea and other countries, including the United States and European Union member states.

In hundreds of cases documented by refugee organizations and the UN, traffickers abused victims while forcing them to telephone relatives who pay the ransom after hearing the victims’ screams. Unknown numbers have died following months of horrific abuse. In November 2012, Human Rights Watch spoke with 21 Eritreans in Egypt and Israel about abuses they had suffered in 2011 and 2012.

The abuses documented by Human Rights Watch and others, including UNHCR and NGOs in Egypt and Israel, involve: rape of women, including having plastic piping inserted into their anuses and vaginas; burning of women’s genitalia and breasts; stripping women naked and whipping their buttocks; rape of men with plastic piping; beating with a metal rod or sticks; whipping with rubber whips or plastic cables; dripping molten plastic or rubber onto skin; burning with cigarettes or cigarette lighters; hanging from ceilings to the point of deforming arms; giving electric shocks; beating the soles of feet; forced standing for long periods, sometimes days; threatening to kill them, remove their organs, or cut off fingers; burning with a hot iron rod or boiling water; sleep deprivation; and putting water on wounds and beating the wounds.

Seventeen interviewees told Human Rights Watch they saw people die in front of them after extensive abuse.

Violence, Extortion, Forced Labor, and Death

Eritreans described how traffickers in Sinai held them in appalling conditions for months and abused them viciously to extort tens of thousands of dollars from their relatives. In some cases, this treatment resulted in death.

Twenty-one Eritreans told Human Rights Watch in detail about how traffickers abused them in Sinai in 2011 and 2012. Fourteen showed Human Rights Watch their injuries, mostly what appeared to be burn marks and scars caused by whippings and beatings.

Seventeen Eritreans described how they were sold from one trafficker to another in Sinai and how the violence got worse each time. Five told Human Rights Watch they saw fellow victims die after repeated abuse. [67] Four described watching or hearing traffickers rape women and two women told Human Rights Watch the traffickers raped them. [68]

In December 2012, Human Rights Watch also reviewed eight detailed interviews with Eritreans taken by NGO staff in Cairo in which they described traffickers’ abuses in detail. [69] The staff told Human Rights Watch that they have over one hundred more such statements.

In these interviews, the individuals describe how traffickers held them for months in appalling conditions, demanding they pay tens of thousands of dollars in exchange for their release and abused them to compel their relatives to pay. [70] In every case, the interviewee said that traffickers repeatedly abused them, often daily, including while they put them on the phone so their relatives could hear their suffering.

Human Rights Watch spoke with a 17-year-old boy from Eritrea’s capital, Asmara, who fled to Hafir in Sudan in August 2011 where “Rashaida men” kidnapped and transferred him to traffickers in Sinai who abused him for eight months until his relatives paid $13,000:

They hung me by my arms, and upside down by my ankles. They beat and whipped my back and head with a rubber whip. They beat the soles of my feet with rubber tubes. They put water on my wounds and then beat them. Sometimes they shocked me with electricity, burnt me with hot irons, and dripped melted rubber and plastic on my back and arms. They threatened to cut off my fingers using scissors. Sometimes they came into the room, took the women out, and then I heard the women screaming. They came back crying. During the eight months, I saw six others die because of this torture . [71]

Another 17-year-old Eritrean boy from Zoba Dobab said he escaped from Eritrea on April 3, 2012, and that “Rashaida” traffickers transferred him to Sinai two weeks later, where Egyptian traffickers held him for 10 weeks in two different locations together with around 60 other people. When he refused to pay $20,000 to the second group of traffickers, they abused him:

They beat my back and legs and the soles of my feet with an iron rod. They dripped molten rubber on my arms and hung me from the ceiling by my hands or by my ankles, sometimes for an hour at a time. I saw other men die in front of me because they just left them hanging for too long. I was in so much pain that I could only get up by using the wall to support me.[72]

A 20-year old Eritrean man said he fled Eritrea on November 15, 2011 with a friend. He said Sudanese police handed him and his group over to traffickers who transferred them to Sinai. In Sinai, other traffickers held and abused them and dozens of other Eritreans for almost three months, including by raping women:

We were blindfolded most of the time. To make us pay, they abused all of us. They raped some of the women in our room, in front of us, and left them naked. They hung us upside down and beat us and burnt us all over our bodies with cigarettes. My friend died from the torture, in front of us.[73]

A 33-year-old Eritrean man from Murki in Eritrea’s Gashbarka region said he crossed into Sudan in September 2011. There, traffickers held him for two months before transferring him to Sinai, where a second group of traffickers held him and about 25 others and demanded $25,000 for his release:

They blindfolded us and then tortured us every day. They gave me electric shocks on my hands and feet. They tied my hands and legs and hung me upside down and then they beat me all over my body with wooden sticks and whipped me with plastic cables. They beat me so badly, I could not stand up anymore, but then they forced me to stand all night long to increase the pain. They raped women in front of us. All I wanted to do was lie down and die. [74]

Human Rights Watch also documented traffickers forcing their victims to work as cleaners or on building sites. [75] Four trafficking victims unable to pay the ransom told Human Rights Watch they agreed to work for the traffickers in exchange for an end to the abuses they had suffered. [76]

A Bedouin religious leader of the Sawarka tribe, Sheikh Mohamed, who lives in Mahdiya between Arish and the Egyptian border town of Rafah, told Human Rights Watch that it was common knowledge in the Bedouin community that traffickers forced Eritreans to work:

I know of hundreds [of Eritreans] at this very moment who are forced to work on constructions sites. They are building houses for the kidnappers who pay for the construction materials with the ransom money.[77]

Since 2011, Sheikh Mohamed has turned his home into a safe house for Eritreans and others who manage to escape from traffickers in Sinai or who are released and are directed to him by other Bedouin.

Sheikh Mohamed told Human Rights Watch he had sheltered dozens of mostly Eritrean men who had been tortured and that some Eritreans died in his house as a result of the abuse they had suffered at the hands of traffickers. [78]

One of Sheikh Mohamed’s relatives, who helps care for trafficking victims, told Human Rights Watch that “one of the methods [traffickers] use a lot is removing skin and putting salt on the wounds and another is hanging people from the ceiling by their wrists while attaching pincers to their nipples and giving them electric shocks.” [79]

Since March 2012, Sheikh Mohamed’s colleagues have taken photos of Eritreans in his care, some of which he shared with Human Rights Watch. Sheikh Mohamed gives survivors food, basic health care, and shelter, and arranges for their transfer to Cairo. [80] UNHCR told Human Rights Watch that “many” of the people Sheikh Mohamed had helped transfer to Cairo had been “severely tortured.” [81]

All five Bedouin leaders Human Rights Watch spoke with said it was common knowledge who the traffickers were in Sinai. One Bedouin man said he knew of four locations around 50 kilometers south of Arish where traffickers from his tribe, the Sawarka, had held dozens of Eritreans over the previous two years and abused them. He said most of the kidnappers are between 16 and 30 years old, and that everyone in his tribe and in Arish city knows these men and what they are doing. [82]

UNHCR staff has also interviewed hundreds of trafficking victims in Israel. UNHCR told Human Rights Watch:

All interviewees bore wounds, scars, and injuries attesting to the physical treatment and abuse. Testimonies described abuse including chaining, blindfolding, prolonged deprivation of sleep, continuous beatings, suspension until deformation of arms, electrocution, and droppings of melted rubber onto the skin. More recent testimonies also describe new forms of abuse, such as direct burning of the skin with a lighter on the neck, and throwing of boiled water.... 11 of the 15 women that were interviewed claimed they had been sexually assaulted. The abuse included insertion of objects, oral sex, and rape. A number of women and men described how women were also assaulted by Eritrean men held captive, who were forced to sexually abuse the women. Those who refused to participate in the act were punished severely by additional beatings. Additional men maintained they suspect the women in their respective groups were sexually assaulted, since they were taken outside on many occasions and later returned in tears. [83]

In August 2012 and September 2012, Human Rights Watch spoke with reliable sources in Cairo with regular access to freed or escaped trafficking victims and published a summary of what they said in September 2012. [84] Victims interviewed in 2011, 2012, and 2013 said that in Sinai traffickers tortured them in numerous ways, including sexual violence against women. [85]

In December 2013 and January 2014, Human Rights Watch spoke with an Eritrean activist who has spoken since 2010 by phone with hundreds of Eritreans held in Sinai, as well as with their extorted relatives abroad. She told Human Rights Watch that during Egypt’s renewed military crackdown in Sinai, which started in September 2013, she had received no new reports of Eritreans trafficked into Sinai, but that in November the calls started again. She said she had spoken to trafficking victims, and in two cases relatives of trafficking victims, who described the circumstances in which four different groups of Eritreans, a total of 47, had been kidnapped in eastern Sudan and taken to Sinai between November 2013 and January 2014.[86]

The international media reported new trafficking cases in Sinai in November 2013.[87] UNHCR also has interviewed a number of trafficking victims who were abused in Sinai in 2013.[88]

In mid-2012, the UN Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea concluded that “Bedouin traffickers...routinely hold their passengers captive and demand exorbitant ransoms from their families for their release—typically between $30,000 and $50,000. If ransom is not paid, hostages may find themselves brutally tortured or killed.” The Monitoring Group included five testimonies of Eritreans who were kidnapped in eastern Sudan or Khartoum and taken to Sinai, where they were tortured and where some of them witnessed fellow kidnap victims die under torture.[89]

In June 2013, the US State Department issued its annual Trafficking in Persons report, which noted:

Instances of human trafficking, smuggling, abduction, torture, and extortion of migrants, including asylum seekers, and refugees—particularly from Eritrea, Sudan, and to a lesser extent Ethiopia—continue to occur in the Sinai Peninsula at the hands of criminal groups. Many of these migrants are reportedly held for ransom and forced into sexual servitude or forced labor during their captivity in the Sinai, based on documented victim testimonies. Reports of physical and sexual abuse continue to increase….[They] are brutalized, including by being whipped, beaten, deprived of food, raped, chained together and forced to do domestics or manual labor at smuggler’s homes.[90]

Over the past three years, hundreds of Eritreans have also given detailed statements to Administrative Tribunals in Israeli detention centers on the torture they suffered in Sinai. Israeli NGOs have published some of the statements. [91] In December 2010, Human Rights Watch reviewed and reported on 30 such statements describing how the traffickers shackled their legs and chained people together for months on end, raped women, burned limbs with hot iron bars, whipped them with electrical cords, beat them and forced them to do manual labor. [92] Human Rights Watch found the statements to be credible because of the level of detail involved and, additionally, because of their consistency with interviews Human Rights Watch conducted in Egypt and Israel in November 2012.

Since 2010, non-governmental organizations have also issued numerous reports documenting the torture and deaths of sub-Saharan nationals in Sinai. [93]

Physicians for Human Rights-Israel (PHR-Israel), an NGO that advocates for health rights of undocumented migrants and gives them primary and secondary healthcare, has treated hundreds of people tortured by traffickers in Sinai. Based on 1,300 interviews with sub-Saharan nationals who entered Israel from Sinai between November 2010 and May 2012, the group reported that about a quarter of the interviewees said they had been subjected to serious abuses including sexual assault, electric shocks, burning with metal objects, beating, whipping, prolonged suspension by the limbs, exposure to sun and execution, and threats of organ removal.[94]

In September 2012, Tilburg University in The Netherlands published a report based on interviews with 123 trafficking victims who spoke about torture they suffered in Sinai and what they had witnessed happen to a further 240 torture victims, including children. Interviewees spoke about rape, severe beating, electric shocks, burning, hanging by the limbs, hanging by the hair, and amputation of limbs. They also spoke about watching fellow kidnap victims die under torture.[95]

In December 2013, the University published a second report for which the authors interviewed 115 Eritreans who described how they were kidnapped in eastern Sudan and abused in Sudan and by Egyptian traffickers in Sinai.[96]

Anonymous Egyptian security officials have spoken about finding bodies of African nationals in various parts of Sinai. [97] International and Egyptian media have published dozens of articles on trafficker abuses in Sinai. [98]

Number of Victims, Length of Time Held, Trafficker Identities and Locations

According to the Egyptian authorities themselves, as well as people working with refugees in Egypt, including on Sinai abuses, the Egyptian authorities have not investigated trafficking and torture in Sinai and do not allow UNHCR to work there. As a result, there are no statistics on the number of trafficking victims and the number subjected to violence.

Between January 2006 and December 2012, UNHCR says about 35,000 Eritreans entered Israel through Sinai. Of these, almost 25,000 crossed in 2011 and 2012. [99] There is no way of knowing how many of them were tortured and abused. Considering that a quarter of the 1,300 trafficking victims that PHR-Israel interviewed said they were tortured and abused, the number is likely to be in the thousands. [100] One trafficker whom researchers interviewed in 2013 said he was personally responsible for the death of 1,000 Eritreans and other sub-Saharan nationals. [101]

Between 2010 and 2013, UNHCR in Israel conducted over 700 interviews with sub-Saharan nationals who reached Israel through Sinai who had scars and who described in detailed interviews how traffickers had abused them in Sinai. [102]

Eritreans who spoke with Human Rights Watch said they were held in Sinai from two weeks to three months. Trafficking survivors who spoke with PHR-Israel have described being held between a few days to almost a year, echoing the statements of Eritreans who told an Egyptian NGO that they were held for up to a year.[103] The average length of detention referred to in a small sample of testimonies trafficking victims gave to Israeli immigration tribunals was 140 days. [104]

About a third of the 36 Eritreans who spoke with Human Rights Watch said they had been held for so long because they were sold between various traffickers, and Eritreans have told other organizations the same. [105] The 17-year-old trafficker Human Rights Watch interviewed said he regularly bought from other Bedouin trafficking victims who already had torture wounds and were weak. [106]

As noted above, Human Rights Watch interviewed two traffickers who said that there were dozens of trafficker bases in the areas around Arish alone. Journalists have interviewed trafficking victims who were held in Mahdiya, near the border with Gaza. [107]

Based on hundreds of interviews with trafficking victims, various organizations have published details of traffickers who victims say held and abused them. As discussed below, Egyptian police have made little or no effort to investigate or apprehend any of those alleged to be responsible.

Local Community Attempts to End Trafficking

Two Bedouin community leaders told Human Rights Watch that Bedouin communities throughout Sinai knew who the traffickers were. In the absence of any Egyptian security forces response to trafficking crimes in Sinai, some community leaders have attempted to dissuade Bedouin traffickers from continuing their crimes.[108]

Community leaders described to Human Rights Watch how informal “sharia courts” have encouraged kidnappers to renounce their activities. [109] A senior community leader who helped numerous Eritreans and other sub-Saharan nationals after they were released or escaped said he knew of 15 torturers who had renounced their activities in front of such courts. [110]

Human Rights Watch spoke with one senior community leader who presides over such a court who said ten men had renounced their activities at his council in 2011 and 2012. The sheikh said that he would have no objections to the Egyptian police or military shutting down the various kidnapper hideouts because kidnapping and torture is “not in line with Islamic values.” [111]

Egyptian Security Force Collusion with Traffickers

Human Rights Watch interviews with Eritreans suggest that some Egyptian police and soldiers—including at the heavily controlled Suez canal—have colluded with traffickers taking Eritreans to, and holding them in, Sinai.

In November 2012, Human Rights Watch interviewed 11 Eritreans about 19 incidents that occurred between 2009 and 2012 involving police and military collusion with traffickers who held and tortured them in Sinai. Eleven of the incidents involved the military and eight involved the police. [112]

The collusion took place at points along the Nile that victims could not identify by name, where Sudanese traffickers handed victims over to members of the Egyptian military or police who then transferred them to Egyptian traffickers; at the Suez Canal, where Sudanese or Egyptian traffickers crossing in boats handed victims over to Egyptian soldiers on the eastern (Sinai) side of the canal or where Egyptian policemen on the western side of the canal allowed trucks filled with trafficking victims to cross the canal’s only bridge for vehicles; at traffickers’ houses or at checkpoints in Sinai, where members of the Egyptian military visited traffickers houses and saw trafficking victims without intervening or where Egyptian military personnel intercepted escaped trafficking victims and returned them to traffickers; and at the Israeli border, where—in contrast to other Egyptian security forces at the border who try to prevent Eritreans and others from crossing to Israel—Egyptian soldiers met with traffickers who had released their victims and helped the victims cross the border.

In November 2012, the head of Egypt's anti-trafficking committee told Human Rights Watch that there have been no prosecutions of traffickers and other criminals responsible for abuses against sub-Saharan nationals in Sinai.

Collusion by members of the Egyptian security forces with traffickers who physically abuse their victims and Egypt’s failure to investigate traffickers’ abuses, coupled with the serious nature of the abuses, means Egypt is violating its obligations under the Convention Against Torture. [113]

As noted below, Egyptian authorities have responded to Human Rights Watch’s presentation of these facts by either denying collusion and abuses take place in Sinai or by saying they do not have enough information to initiate investigations.

Collusion at the Nile

Human Rights Watch documented two incidents in which Egyptian soldiers colluded with traffickers at the Nile. Trafficking victims were unable to say where exactly they crossed the Nile.

A 16-year-old Eritrean boy said he fled to Sudan in February 2012 but was kidnapped by six “Rashaida men” soon after crossing who transferred him in a group to Egypt. He said:

When we reached a big river the Rashaida told us it was the Nile. There were already 20 other Eritreans kidnapped before us who were waiting there. They put all of us in a boat, covered us with canvas and we sailed for about two hours. There were six people with guns waiting for us on the other side. It was dark but as we got closer I could see they had lighter skin than the Sudanese, so we all knew they were Egyptians. Three were wearing jalabiyas [traditional long robes] and three were in military uniform, green jackets with spots and trousers with mixed colors including grey.

The three men in uniform stood to one side and watched while the other three beat us with sticks and forced us into the back of two red pickup trucks and covered us with canvas. I could see through holes in the canvas and I saw the three soldiers get onto the back of the pickup truck I was in.

After a while, we reached a military checkpoint and stopped. I heard people talking and we drove on. The next time we stopped, four men with guns and wearing jalabiyas loaded us all onto a big truck. I saw two of the men in uniform drive off in one of the pickups and the third man stayed with us while we were loaded into the truck. After that, I didn’t see him again. [114]

A 26-year-old Eritrean man said Sudanese traffickers took him and other trafficking victims to Egypt in February 2012, where they crossed the Nile and then held them for three days in a house nearby. He said:

After three days, six beige-colored military vehicles arrived. The men who got out had lighter skin and looked like Egyptians. They were wearing normal civilian clothes, except for two who were wearing jalabiyas. All of them had weapons and military belts with military equipment on them. The men put our group of around 30 people into four of the six military vehicles.

We drove with them for one night and one day. The two other military vehicles followed us all the way. Then the men transferred us into a big civilian truck. None of the men from the military pickup trucks got into the back of the big truck with us.[115]

Collusion at Checkpoints

Human Rights Watch documented five incidents of Egyptian police collusion with traffickers at checkpoints.

In one case typical of three others, Sudanese police intercepted a 20-year-old Eritrean man who fled to Sudan in November 2011 and handed him over to Sudanese traffickers. After holding him for a month in Sudan, they transferred him and dozens of other Eritreans in a medium-sized Mitsubishi pickup truck. The police told them to sit down and covered them in plastic sheeting. He said:

They told us when we reached Egypt. Then we went through three police checkpoints. We could see them through gaps in the plastic. The police had lighter faces than the Sudanese so we knew they were Egyptian. They were wearing green and caps. They never looked under the plastic. Each time, they searched all the other cars but not ours. They just let us pass.[116]

Collusion at the Suez Canal

Human Rights Watch spoke with six Eritreans who described how soldiers and policemen colluded with traffickers at the Suez Canal. Four cases involved military personnel and two involved policemen. Some instances of collusion happened on the banks of the canal, with traffickers transporting their victims across in boats, sometimes at night. Other cases happened at police and military checkpoints at the entrance to the Suez Canal Bridge at Qantara, 160 kilometers northeast of Cairo and 50 kilometers south of Port Said.

A 32-year-old Sudanese man trying to reach Israel travelled with smugglers to Sinai in April 2011, together with 70 other Sudanese men in a passenger bus. The group was kidnapped by Egyptian traffickers when they reached the Suez Canal. He told Human Rights Watch:

The driver told us to get off the bus and we were told to wait in a house, about 150 meters away from the edge of the water. Just after dark, Egyptian police—in blue uniform—arrived and a little while after a boat arrived. The smugglers put 25 of us in the boat, while the police stood about 50 meters away, watching. We crossed the canal. On the other side there were three soldiers, wearing beige dotted uniforms and with small handguns, standing next to some men who looked like Bedouin. While the soldiers watched, the Bedouin loaded us into the back of two civilian pickups and told us to lie down and covered us with plastic.[117]

A 37-year-old Eritrean man had an almost identical story. He told Human Rights Watch that in June 2011 traffickers took him and 80 others across the canal at night in a boat and that on the Sinai side two Egyptian soldiers walked them from the boat to the cars of the Bedouin traffickers who then held and abused them for three weeks.[118]

A 22-year-old Eritrean man was trafficked from Sudan to Egypt in June 2011. He said:

A few dozen of us were crammed into the back of a pickup truck with canvass on top of us. When we reached the Suez bridge, some of us could see through some holes in the canvas. I saw three of the traffickers get out and speak with the police who were at the checkpoint before we crossed the big bridge. We saw the police were checking some of the other cars but they didn’t check ours. The kidnappers got back in the truck and we drove over the bridge.[119]

One of the two traffickers Human Rights Watch interviewed in Sinai confirmed that Egyptian police and military colluded with traffickers at the bridge and at the Ahmed Hamdi tunnel that runs under the canal about ten kilometres north of the town of Suez:

From Sudan, traffickers travel to Aswan, where they stay a night or two, and then onwards to Ismailiya [30 kilometers south of the Suez Canal bridge]. From there they cross the canal to Sinai, by boat or over the bridge or through the tunnel. On the other side they hand them over to people who work for me with my cars on this [Sinai] side of the canal.

They cross the bridge or drive through the tunnel with buses and trucks full of Africans. Until December 2011, all the police at the bridge and tunnel took bribes to let us bring Africans into Sinai. Sometimes the police even drove the trucks across. In December, the military took over control of the bridge. Sometimes they make it difficult to cross at the bridge and tunnel, but they still take bribes and let us cross.[120]

According to an international aid worker in Cairo with good knowledge of the situation at the Suez Canal, since early 2011 both the military and the police have been stationed at the tunnel and bridge. [121]