Containment Plan

Bulgaria’s Pushbacks and Detention of Syrian and Other Asylum Seekers and Migrants

Map

A Pushback Victim’s Story

My wife and kid were hiding and I lost them there and haven’t seen them since. I don’t know why they arrested me without taking my wife. When the police found me and arrested me they immediately started beating me. They kneed me in my crotch very hard. Three police beat me. When they beat me I tried to say that my wife and child were close by. But they didn’t listen and they didn’t say anything that I understood. The only English they knew was “No, no Bulgaria!”

After beating me, the police brought me over to their superior who pointed to his boot as if because of me his boot was dirty. So he ordered the soldier to beat me. First he beat me with his fist in my stomach and then with the butt of his gun on my back so I fell down, then he kicked my ribcage while I was lying down. One of my bones in my lower back is broken. I had very intense pain but didn’t know that it was broken at the time. They kept beating my head and my back. First one soldier and then another. I tried to escape but they caught me and beat me even more. They even beat me as they were dragging me to the car. They put three of us on the back seat of the jeep. I wasn’t even thinking about pain, all I was worried about was my wife and child….

They drove us for about 30 to 45 minutes and took us out of the car and again, one of the soldiers started beating me with his stick all over except for my head, but particularly my chest. We were walking at this point so while we were walking he kept hitting me with his stick. The walk was about 200 meters and I was beaten all the way. When we reached the border, the soldier showed the direction to Turkey.[1]

A 21-year-old Afghan from Herat, interviewed in Turkey, who said that he crossed into Bulgaria with his wife and very young child in mid-October 2013. He said he saw the Bulgarian flag and that he and four others walked another two to three hours inside Bulgaria when a Bulgarian official and two uniformed subordinates caught him and two other men, but not his wife and child. He showed Human Rights Watch the scars on his back.

Summary

In recent times, Bulgaria has not been a host country for significant numbers of refugees. On average, Bulgaria registered about 1,000 asylum seekers per year in the past decade. This changed in 2013 when more than 11,000 people, over half of them fleeing from Syria’s deadly repression and war, lodged asylum applications. Bulgaria was unprepared for the surge in asylum seekers, showing itself incapable of processing individual asylum claims, and failing to provide new arrivals with basic humanitarian assistance, including food and shelter.

As a member state of the European Union (EU), Bulgaria is legally obliged to meet the standards for the reception of asylum seekers set by the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) and to operate an asylum system according to the same procedures as any other EU member state. As this report documents, however, Bulgaria failed to meet not only EU standards, but also minimal international standards for the treatment of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants. As a result, at almost every stage of their efforts to seek refuge in Bulgaria, men, women and children fleeing such places as Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan have faced physical and bureaucratic barriers, violent abuse, and hardship.

Pushbacks

On November 6, 2013, the Bulgarian government established a new policy to prevent irregular entry at the Turkish border. This “containment plan” entailed deploying an additional 1,500 police officers at the border, supplemented by a contingent of guest guards from other EU member states through the EU’s external border control agency, Frontex, and the construction of a fence along a 33-kilometer stretch of the Turkish border.

In the weeks before the new containment policy was implemented, the Bulgarian authorities were already trying to limit the number of people trying to cross, but the implementation of the containment plan on November 6 effectively slammed the door to new arrivals. Human Rights Watch heard migrants’ accounts of being apprehended inside Bulgaria or at the border and being summarily returned to Turkey, either by being turned over to Turkish guards or by being taken to the border and ordered to walk in the direction of Turkey.

In early December 2013, Human Rights Watch toured an empty temporary holding center for irregular migrants at Elhovo about 28 kilometers north of the Turkish border. In a converted basketball court, which had held hundreds of people a couple of weeks earlier, all that remained were vacant cages and the detritus of filthy, torn bedding. The UN refugee agency (UNHCR) reported that only 99 people crossed into Bulgaria from Turkey in January 2014.

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch interviewed 177 refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants in various locations in both Bulgaria (140) and Turkey (37). Most of those interviewed in Bulgaria had arrived prior to the November 6 policy change. Nearly all of those interviewed in Turkey had been pushed back, both before and after the change. Human Rights Watch heard detailed accounts of 44 pushback incidents from 41 people. The pushback incidents involved at least 519 people in which Bulgarian border police apprehended people on Bulgarian soil and summarily returned them to Turkey without proper procedures and with no opportunity to lodge asylum claims, often using excessive force. Many of those interviewed about being summarily returned said that Bulgarian guards beat or otherwise mistreated them.

This report concludes that the precipitous drop in border crossings, coinciding with the formal announcement of a policy to contain and reduce the number of asylum seekers and other migrants irregularly crossing the border, indicates a systematic and deliberate practice of preventing undocumented asylum seekers from entering Bulgaria to lodge claims for international protection. This conclusion is supported by the accounts people gave to Human Rights Watch about Bulgarian border police forcibly returning them to Turkey.

Conditions in Detention Facilities and Registration and Reception Centers

Although new arrivals had virtually stopped by the time of the Human Rights Watch visit, the Bulgarian authorities were hardly able to cope with those who were already there. The Bulgarian border authorities were transferring some irregular border crossers, particularly north Africans, to one of two detention centers operated by the Ministry of Interior: Lyubimets, located about 30 kilometers northwest of the Turkish border, or Busmantsi, on the outskirts of Bulgaria’s capital, Sofia. Both detention centers are locked and guarded prison-like buildings surrounded by high walls and barbed wire.

Detainees in both facilities complained to Human Rights Watch about abusive, sometimes violent, treatment by guards, overcrowding and noise, tension among various nationality groups, the mixing of unaccompanied children with adults, dirty and insufficient toilets, inadequate ventilation, and the poor quality of the food. They also complained that they had limited means to communicate with the outside world, as well as a lack of communication with guards and other authorities. This resulted in ignorance and confusion about procedures relating to release or to seeking asylum.

Unaccompanied migrant children were held in detention centers together with adult detainees, in breach of international law, during 2013 and were not assigned legal guardians. The absence of legal guardians prevented unaccompanied children from access to social services and put them at further risk of exploitation and homelessness.

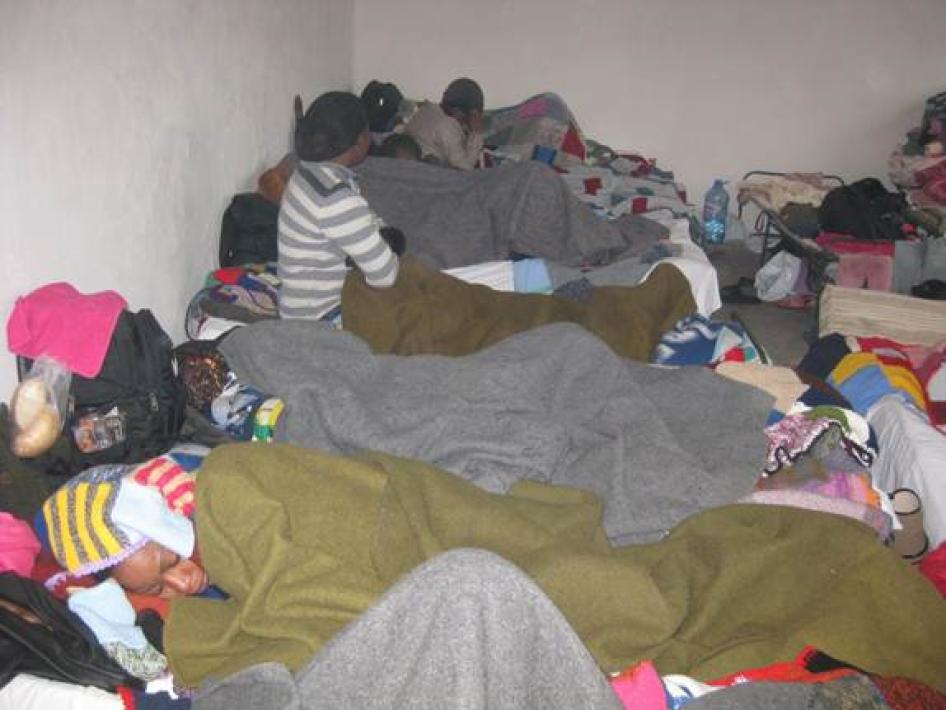

At the time of the Human Rights Watch visit to Bulgaria, the Bulgarian authorities had transferred more than a thousand Syrians, Afghans, and others, including families with young children, to a former army base converted into a closed camp near the town of Harmanli, about 50 kilometers from the border. The authorities transferred people whom they regarded as potential asylum seekers from border police stations or the migrant detention centers to Harmanli. In the first months of Harmanli’s use as a camp, most of the detainees lived in a muddy stretch in tents that provided no protection from the rain and cold. By the time of the Human Rights Watch visit, the State Agency for Refugees (SAR) had moved most of the people out of the tents and some were living in warm and dry prefabricated containers but the agency had not provided decent accommodation for hundreds of newcomers who were living in filthy and cold buildings that lacked heat, windows, or adequate plumbing.

At the time of the Human Rights Watch visit, the Bulgarian authorities would not allow any Harmanli residents to leave the camp. Conditions at Harmanli have improved since our visit. Starting on February 1, 2014, the Bulgarian Ministry of Defense began providing hot meals. A month later, the buildings were heated, Harmanli was designated as a registration and reception center, and all residents were registered as asylum seekers. By March 6, residents were permitted to come and go from Harmanli during afternoon hours and as of March 19 restrictions on movement in and out of the center had been lifted.

Human Rights Watch also visited five SAR-administered registration and reception centers for asylum seekers in December 2013, and was able to enter three of them. In four of the five centers, residents complained about lack of heat. In all places, asylum seekers said that the 65 leva (approximately 33 euros or US $44) per month allowance for each asylum seeker was inadequate to meet their basic needs for food and other necessities. Two of the centers were converted schools that were never designed as living quarters; both were dilapidated, overcrowded, cold, and dirty without adequate facilities for bathing or washing.

Despite the conditions, many residents expressed the fear that they would be granted refugee or humanitarian status, at which point the facility administrators would give them five days to leave before turning them out on the street with no further assistance. At the time of the writing of this report, conditions in the reception centers are reported to have improved. According to UNHCR, all centers have heat, the SAR provides two hot meals a day to residents, and many residents are now being allowed to remain in the centers for longer periods after being granted refugee or humanitarian status if they lack the means to support themselves.

Granting of Refugee or Humanitarian Status

While the Bulgarian government’s record on granting refugee or humanitarian status is relatively good, authorities provide little or no support to asylum seekers once they have been granted status or have left reception centers.

During 2013, 7,144 people applied for asylum in Bulgaria of whom 4,511 were Syrians. SAR processed 2,816 asylum claims, granting 2,279 persons humanitarian status and 183 refugee status and denying 354, a protection rate of 87 percent of cases decided. Most of those granted some form of protection were Syrians.

After granting refugee or humanitarian status, the government stops providing refugees the 65 leva per month they had received as asylum seekers. Human Rights Watch researchers met recognized refugees who were homeless and squatting in unfinished, abandoned buildings in the vicinity of the open centers. Although authorized legally to work after being recognized, refugees find it almost impossible to find work in Bulgaria, the poorest country in the EU with high unemployment rates. Very few refugees speak even minimal Bulgarian—because no language classes are provided—and find the prospect of job-seeking intimidating.

Given the harsh treatment many have experienced in Bulgaria and the draw of relatives and better job prospects in Germany, Sweden, and other countries lying to the west, many asylum seekers told Human Rights Watch that they would leave the country as soon as they were able to and would not come back voluntarily. However, EU and national laws make it difficult for recognized refugees and beneficiaries of subsidiary protection granted by one EU member state to work in another, or to adjust their status once there. Consequently, many refugees who leave Bulgaria for other EU member states risk sanctions for unauthorized stay and forced return to Bulgaria.

The Wider Picture

The “plan for the containment of the crisis resulting from stronger migration pressure on the Bulgarian border” adopted by Bulgaria’s Council of Ministers presumed that there was a migration crisis on the Bulgarian border. A little perspective on Bulgaria’s migration crisis is in order.

In the first five weeks of 2014—at a time when 99 asylum seekers succeeded in crossing from Turkey to Bulgaria—more than 20,000 Syrian refugees entered Turkey, the country to which Bulgaria was pushing back asylum seekers. The number of Syrian asylum seekers entering Turkey in the first five weeks of 2014 was roughly double the number of all asylum seekers entering Bulgaria during the whole of 2013. By the end of January 2014, Turkey had registered 580,756 Syrian refugees and another 44,800 non-Syrian asylum seekers. UNHCR registered more than 860,000 Syrian refugees in Lebanon in 2013; this would be the equivalent of 1,482,000 refugees suddenly arriving in Bulgaria. Bulgaria hosted 6,832 registered asylum seekers as of March 19, 2014.

Bulgaria, of course, is faced with a humanitarian challenge and its capacity to meet that challenge is limited. But the European Union has helped to bolster its capacity and the humanitarian situation inside the country is improving for the refugees and asylum seekers who have already entered. Even with limited capacity, however, Bulgaria must meet basic, minimal obligations to respect the rights of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants. As this report documents, it has failed to do that.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Bulgarian government to end summary expulsions at the Turkish border and to stop the excessive use of force by border guards. We further call on the Bulgarian government to improve the treatment of detainees and conditions of detention in police stations and migrant detention centers.

Human Rights Watch calls on EU member states not to return asylum seekers to Bulgaria under the Dublin Regulation until Bulgaria fully complies with the standards of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), in particular, by significantly improving detention conditions, by providing effective protection for asylum seekers, by providing assistance to enable the integration of people with refugee or humanitarian status, and by ceasing summary, brutal forced returns at the Turkish border.

Human Rights Watch welcomes significant improvements in registration and reception conditions for asylum seekers in the reception centers since our visit to Bulgaria in December 2013. But these improvements coincide with the institution of a harsh pushback policy and a drop in arrivals of new asylum seekers. This suggests that those fortunate enough to have entered before the door was slammed will now be treated decently, but that the rest will face a closed door despite the existence of an infrastructure finally capable of receiving them and registering their asylum claims.

For Bulgaria, the solution to what it perceives as a mass refugee influx, or a potential mass influx, should not be to push back undocumented asylum seekers attempting to cross the border with Turkey but rather to keep the border open to asylum seekers and treat them decently. For its part, the EU should agree on a common position to promote burden sharing among EU member states, including through the relocation of asylum seekers and refugees in Bulgaria to other EU member states.

Recommendations

To the Government of Bulgaria

- End summary expulsions and rejections of asylum seekers from within Bulgaria and at the Turkish border.

- Stop beatings, use of electric shocks, and other abuses against migrants at the border with Turkey; investigate and hold to account officials who abuse foreigners.

- Provide irregular migrants at the border access to formalized procedures, including the opportunity to lodge claims for protection in Bulgaria.

- Do not detain asylum seekers as a deterrent measure to reduce the number of people seeking protection in Bulgaria; provide open accommodation for asylum seekers.

- Ensure that all detainees in the custody of the General Directorate of the Border Police and the Ministry of Interior are treated in a humane and dignified manner and that their detention fully complies with Bulgaria’s international obligations governing the administrative detention of migrants.

- Do not detain unaccompanied migrant children or children with their families. Detain children only as a measure of last resort dictated by their best interests. Do not detain children with unrelated adults. Provide all unaccompanied children with legal guardians, as required by Bulgarian law.

- Ensure that staff and guards of migrant detention centers and border police stations and staff of the State Agency for Refugees are able to communicate with foreigners in their own languages, including through the use of competent interpreters.

- Ensure that all residents of reception centers are treated in a humane and dignified manner and that their accommodation fully complies with Bulgaria’s EU obligations governing the reception of asylum seekers.

- Fully fund the National Program for Integration of Refugees to enable proper integration for all recognized refugees and beneficiaries of humanitarian status.

To the European Union

- The Council of the European Union should agree on a common position to promote equitable burden sharing among EU member states, including through the relocation of asylum seekers and refugees to other EU member states.

- European Union member states should not return asylum seekers to Bulgaria under the Dublin Regulation. They should not resume transfers until Bulgaria demonstrates that it complies with EU standards on the human rights of asylum seekers and refugees, particularly until Bulgaria stops blocking access to asylum and summarily returning irregular border crossers at the Turkish border; improves the poor conditions and ends maltreatment in migrant detention centers; closes gaps in the asylum procedure; and addresses its lack of capacity to integrate people with refugee or humanitarian status.

- The European Commission should continue to provide humanitarian and technical assistance to Bulgaria to bring its asylum and migration system into line with the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). It should identify any breaches of the CEAS by Bulgaria and the steps it needs to take to comply with the CEAS, provide a clear timeline for compliance, and consider enforcement action if Bulgaria fails to take prompt action to remedy the breaches identified.

Methodology

This report is based on field research in Bulgaria from December 1 to December 15, 2013 and in Turkey from January 12 to January 18, 2014. To the best of our knowledge, the reporting on the situation in Bulgaria is current as of March 21, 2014.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 140 refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants in Bulgaria and 37 in Turkey. Out of the 177 people interviewed, 83 were from Syria (of whom 48 were Kurds), 48 from Afghanistan, 12 from Algeria, 8 from Morocco, 8 from Iran, and the remainder were from 14 other nations.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 157 males and 10 females, including 13 unaccompanied children, of whom one was a girl. Interviews were all in private with no others present except, where noted, for 10 family interviews involving immediate family members. The average length of interviews was about 30 to 40 minutes. The Human Rights Watch researchers were a male and a female; in Bulgaria, both interpreters were female and in Turkey both were male.

In all cases, Human Rights Watch told all interviewees that they would receive no personal service or benefit for their testimonies and that the interviews were completely voluntary and confidential. All names of migrant and refugee interviewees are withheld for their protection and that of their families, and in some cases we have concealed other details, such as the location of the interview. The notations in this report use a letter and a number for each interview; the letter indicates the person who conducted the interview and the number refers to the person being interviewed. All interviews are on file with Human Rights Watch. Several interviewees told us that the Bulgarian authorities had taken punitive action against them after they talked to journalists or others and some detainees told us that the authorities had told them not to complain to Human Rights Watch shortly before our visit.

Although we made every effort to choose detainees to speak to at random, on the first day of our visit to Busmantsi most of the detainees we interviewed all came from the same room, which we learned during the course of the interviews was in better condition than other rooms. On the second visit to Busmantsi, we were able to interview different detainees from each floor of the facility. At Lyubimets, our visit came shortly after an incident in which detainees alleged that guards beat many people severely. We were prevented from seeing or interviewing more severely injured detainees, according to the detainees we did interview. At the Elhovo Distribution Center, the guards wrote down the names of all detainees we interviewed. Many of the accounts we documented of treatment and conditions at these and other locations were from former detainees who were no longer living in these detention centers at the time of the interview.

All interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interview and that their accounts might be used publicly but with assurances that their real names would not be published. No incentives were offered or provided to persons interviewed. All interviews were conducted privately, except where specifically noted. The interviews were conducted in English and German and with the help of interpreters in Arabic, Kurdish, Dari, and Farsi.

Human Rights Watch interviewed officials of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and staff members of various nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Bulgaria, including the Bulgarian Red Cross, the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee, Caritas Bulgaria, the Legal Clinic For Refugees and Migrants, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and the Office of the Grand Mufti in Bulgaria. We also interviewed Plamen Angelov, deputy minister of interior; Milen Penev, deputy director of border police; and Nikolai Chirpanliev, president of the State Agency for Refugees. In Turkey, Human Rights Watch interviewed a senior official at the Afghanistan Consulate General and staff at Turks of Afghanistan International Social Culture and Association Aid and Yel Değirmeni Orphanage. Human Rights Watch also requested permission to visit Turkey’s migrant detention centers in Edirne, Kirklareli, and Istanbul but was denied permission to visit any centers.

Terminology

Although international law defines “migrant workers,” it does not define “migrants.” In this report, “migrant” is a broad term to describe foreign nationals in Bulgaria. We use the term inclusively rather than exclusively; the use of the term “migrant” does not exclude the possibility that a person may be an asylum seeker or refugee.

An “asylum seeker” is a person who is trying to be recognized as a refugee or to establish a claim for protection on other grounds. Where we are confident that a person is seeking protection, whether in Bulgaria or elsewhere in Europe, we refer to that person as an asylum seeker.

A “refugee,” as defined in the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, to which Bulgaria is a state party, is a person with a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” who is outside his country of nationality and is unable or unwilling, because of that fear, to return.

European Union member states provide subsidiary protection—known in Bulgaria as “humanitarian status” —to people who have been found to face a real risk of suffering serious harm if returned to their country of origin or habitual residence because of the death penalty or execution; torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; or indiscriminate violence in situations of international or internal armed conflict.Recognition of refugee status by a government or UNHCR is declaratory, which means that people are, in fact, refugees before they have been officially recognized as such.

Migrant interviewees used the terms “police,” “guards,” and “soldiers” interchangeably. Anyone referred to as such was described as wearing a uniform, unless the text specifically notes that he was in plain clothes.

The term “pushback” is not defined in international law but is used in this report to describe rejections at the Bulgarian border or expulsions from within Bulgarian territory that occur without allowing expellees to claim asylum and without any individualized assessment of their need for international protection. This method of "pushback" when applied to more than one migrant has been recognized as a form of “collective expulsion,” prohibited under article 4, Protocol 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights. A collective expulsion is any measure that compels aliens, as a group, to leave the jurisdiction without a reasonable and objective examination of the particular cases of each individual alien of the group.

In line with international instruments, the term “child” as used in this report refers to a person under the age of 18. We discuss children traveling with their families and unaccompanied migrant children. For the purposes of this report, we use the definition of “unaccompanied migrant child” from the term “unaccompanied child” employed by the Committee on the Rights of the Child: “‘Unaccompanied children’ are children, as defined in article 1 of the Convention [on the Rights of the Child], who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.”

I. Bulgarian Border Police Pushbacks to Turkey and Abuses upon Apprehension

On November 6, 2013, Bulgarian authorities announced a new policy to reduce the number of irregular crossings of the border, including, explicitly, those seeking protection in Bulgaria. Human Rights Watch interviewed migrants who crossed or attempted to cross the Turkey-Bulgaria border before and after November 6, 2013. Migrants told us of having been summarily returned—or pushed back— after crossing from Turkey to Bulgaria or at the border even in the weeks before November 6, but a near complete shutdown of irregular border crossings occurred with the implementation of the containment plan on that date.

Violent, Summary Returns to Turkey

Human Rights Watch interviewed 41 people in various locations in both Bulgaria and Turkey who gave detailed accounts of 44 incidents involving at least 519 people, in which Bulgarian border police apprehended irregular border crossers in Bulgaria, sometimes significantly inside Bulgarian territory, and summarily returned them to Turkey without proper procedures and with no opportunity to lodge asylum claims.[2] These border pushbacks have also sometimes involved border guards using excessive force.

A 29-year-old stateless man said that he arrived with a group of six or seven Afghans on October 24, 2013. He said that Bulgarian border guards “arrested me and hit me with a police stick in the face and took me back to Turkey, in the bush, not at a crossing point.” He said that they also beat the Afghans he was with. “They were hitting them strong with high kicks and low kicks.”[3]

Human Rights Watch interviewed three adult Afghan siblings in Turkey who said that they were part of a group of two families who succeeded in walking five or six kilometers inside Bulgaria before being caught in mid-October 2013. In a group interview, the three related how Bulgarian border police brutalized them and then lied to Turkish border guards about where they were apprehended:

Brother 1: The police immediately started beating us. They started beating particularly the women and when me [sic] and my brother opposed the police, they started beating the women even worse and some of the others. There were four officers and four dogs.

Brother 2: Two police beat me with kicks and fists for about two or three minutes and on my back.

Brother 1: They beat me for one to two minutes with fists on my back and back of my neck. One in our group was kicked in his sexual organ. Our sister was not beaten. They were holding their dogs and threatened that they would set their dogs on us. After that, they took us to the Turkish border and handed us over to the Turkish guards. The Bulgarian guards lied to the Turks. They told them that they arrested us close to the border, despite the fact that we were 6 kilometers from the border. The Turks asked us if Bulgarians were saying the truth and we said no, that we were arrested 6 kilometers from the border. The Bulgarian guards told the Turks that we were lying. In the end, the Turkish guards took us.[4]

Some people told us that Bulgarian border police threatened them with guns, including by shooting over their heads. During a group interview in Turkey with five Afghans, three boys and two men, one of the interviewees described one such incident in early January 2014:

We heard gunfire and shouting…. We saw two Bulgarian guards about 100 meters from us. We had some sticks in our hands and the two Bulgarian guards pointed their guns at us. We dropped our sticks and raised our hands and surrendered. Although we didn’t expect it, they fired their guns at us. Thank God, nobody was hurt. After they fired, we were so scared that we started running back into Turkey.[5]

In a separate incident in the third week of December 2013, a 22-year-old Afghan man, interviewed together with his 19-year-old wife, said the Bulgarian guards firing over his head drew return fire from the Turkish guards. In the exchange of gunfire, he was shot twice:

I am sure we were in Bulgaria when we saw the Bulgarian guards shooting. We started running towards Turkey and the Turkish guards fired seven or eight shots at us. I could see the guards; they were about 25 to 35 meters away. I got hit by two bullets in the right buttocks. When I was shot I had reached Turkish soil.[6]

Border Stand-offs

Human Rights Watch heard several different accounts of Bulgarian border guards taking individuals or a group to the border with Turkey and leaving them there, not allowing them into Bulgaria or to ask for asylum. At times, the Bulgarian guards were met by Turkish border guards and a standoff ensued, sometimes lasting for days, during which time the migrants had to endure extremely harsh winter weather conditions and were not provided with blankets, food, or water.

A Syrian, who said that he immediately asked for asylum when he was caught after crossing the border, described his severe beating at the hands of Bulgarian border guards when such a stand-off occurred just inside the Bulgarian border on November 12, 2013:

While on the border, two Bulgarian police hit me with truncheons in the face and on my neck. And then several more police came, I don’t know how many, and also started hitting me with their truncheons. I was beaten because I crossed the border and was told to leave. They beat me so bad that I fainted for a few moments and my vision became all blurry afterwards. They also tried to beat my wife but she was clenching our baby and when they saw that they didn’t beat her. Instead, the police pushed her so she fell to the ground. We kept asking the police for water, but they refused to give any. The Turkish police gave us water instead. The Bulgarian police kept trying to push us back but the Turks didn’t allow it.[7]

After this stand-off the Bulgarian authorities took his group to the Elhovo police station, where they spent 12 days, and from there to the Harmanli camp.

Another group of Syrian was involved in a similar stand-off when they arrived at the Bulgarian border on October 28, 2013. According to a 28-year-old father traveling with 12 family members, including children, Bulgarian border guards caught his group 50 meters inside Bulgaria:

They took us to the line of the border and told us to go back. I refused to go back to Turkey, so they used force. At first, two police hit us to push us back to Turkey, but they were only 2 against 12 of us. So they called for reinforcements. My whole family clutched together sitting down, with our arms clenched together. At this point, police started using their truncheons to beat us wherever they could reach. They also hit the women. We were sitting on the ground. It was cold because we had to cross the river first and we were wet. We stayed seated on the ground for two hours.

At one point, the police took my brother and hit him and pushed him over to the Turkish side with all his stuff. My brother’s wife tried to reason with another border police to let him back. My son was very scared and peed himself in fear. My relative was pushed to the ground and dragged on the ground. They did these things because we didn’t want to go back to Turkey. Two police started beating my back with a truncheon as I was sitting and then two more. I still have pain in my back because of this.[8]

Human Rights Watch researchers also documented cases in which Bulgarian border guards forcibly detained people in freezing, snowy conditions in the mountainous border region without providing so much as a blanket. A 24-year-old Palestinian from Syria, who entered Bulgaria on September 25, 2013, said that he reached a village inside Bulgaria when Bulgarian border police apprehended him and took him back to the border where he spent two nights sitting in the cold:

They caught us and took us right to the border with Turkey. An officer came. They said they would call for the Turkish police to come and get us, but the Turkish police never came. They would not let us enter or go back to Turkey. They made us sleep in the snow on the ground for two nights right before their eyes. We asked for a blanket. They would not give us a blanket. When I saw this attitude I became pessimistic. We told the police we wanted to enter Bulgaria. They would not let us enter. For two days they kept saying, “You can go back to Turkey.” Finally, we went into Turkey.[9]

Forced, Organized Returns at the Border

In most of the cases we documented, Bulgarian border guards pushed migrants back summarily with no procedures and no time spent in border police stations, but Human Rights Watch heard several accounts that described a higher level of organization and processing prior to the forcible return.

A 21-year-old Syrian man said that his group had walked for a day and a half and passed four Bulgarian villages before Bulgarian police caught them on December 25, 2013. He said the police took them to a small police station and held them there for about six hours before transferring them to a larger jail-like building where he spent four nights. There he said a man he thought was Bulgarian interviewed him using an interpreter he thought was a Syrian Alawite and thus, he assumed he was a supporter of Bashar al-Asad, Syria’s Alawite president. They asked dozens of questions about his route of entry and his nationality. He told them that he was Syrian and wanted to stay in Bulgaria, but the interpreter said that he had to go back to Turkey. He signed a paper in Bulgarian that he did not understand. He described his forced return:

After I signed the paper at the police station, they put 15 of us in a large military vehicle, using force to push some into the vehicle, and drove us 20 minutes to the border. It was about 11:00 p.m. They took us to an empty space on the border where there were no Turkish guards, and this time they had to push some out of the vehicle. They told us to walk forward and not to turn around. We did not encounter any Turkish troops.[10]

A person speaking on behalf of a group of five Afghans, one child and four men, said after crossing the border from Turkey on December 26, 2013 they spent the night at a base in Bulgaria before Bulgarian border police took them back to the border and forced them into Turkey:

They took us to a base in Bulgaria. Next night they brought us to the Turkish border. When they took us, we were happy because we thought we were going to a camp and they would take our asylum applications. But they didn’t do that. They just kept us without food or water and they were laughing at us. We spent three or four hours there in the middle of the night and no fingerprints were taken, no registration was made. They brought us to the river about one meter deep. We were afraid and wanted a boat, but they didn’t give us. When we refused to cross, one guard fired his gun into the sky. We were so scared we crossed the river.[11]

A 16-year-old unaccompanied Afghan spent time in what he said was a Bulgarian police station and the authorities put him and his three traveling companions on a truck and a boat in the process of forcibly returning them and other migrants to Turkey. After crossing the border in early December 2013, his group had reached a Bulgarian village, where a shopkeeper called the police. The police picked them up and took them to a police station, despite the fact he told the police he was 16 (and therefore entitled to particular treatment, see chapter VII):

We were kept in the police station for 30 minutes. After 30 minutes, another car came to take us to detention….It was about half an hour to the detention center by car. At midnight, they put all the groups together; we found ourselves with Syrians and other Arabs. They put all of us in a truck. I thought I was going to be taken to a camp. It took about one hour until they took us out of the truck. We were in a forest and we saw Bulgarian military people. They made us walk for ten minutes until we reached a river. Next to the river, two guards with guns were waiting. There was also a boat. They had to split the larger group into two smaller groups as they could only take six people at a time in the boat. But they took us all to the other side. There they just dropped us and disappeared. I didn’t even have shoes.[12]

Border Police Abuses

In addition to instances of forcibly returning irregular border crossers to Turkey, Bulgarian border guards have hit, kicked, and set guard dogs on irregular border crossers as well as stolen money and personal belongings from them and made verbal threats, according to the accounts of migrants. A 25-year-old Syrian told Human Rights Watch about his experience crossing the border on October 23, 2013:

The first policeman I met beat me on my leg. It was exactly at the border, but I was sure I was inside Bulgaria. They beat me and my cousin. One guard hit me with his open hand and then kicked my leg. They took our ID cards and documents, and then brought us to a police station. We were there from 8 p.m. to 2 a.m. It was like a jail where they laughed at us and treated us without respect.[13]

A 40-year-old Algerian man was bitten by a guard dog when he was apprehended on May 29, 2013:

I met the police in the forest and they were with dogs. I wasn’t trying to run. I surrendered, but they set the dog on me. They pushed the dog to me. They controlled the dog. It was on a leash. The dog bit me three times on the leg.[14]

A 19-year-old Palestinian from Syria who crossed the border during the second week of December 2013 said he was robbed and abused by officials he said were Bulgarian border guards:

When we crossed the border some guards caught us and told us if we did not give them our money they would send us back to Turkey. They were definitely border guards. They were wearing army clothes. They took our mobiles [phones] and took $120 cash from me. The one who took my $120 had a camouflage military uniform. I would recognize him. Then they took us to the forest and pointed and told us to walk to the main road in Bulgaria, but we knew they had pointed us in the direction of Turkey.[15]

A 25-year-old Afghan gave a similar account of robbery and abuse in the course of being forcibly returned to Turkey on January 11, 2014:

The Bulgarian guards found us and pointed their guns at us and started beating us…. Afterwards, they put us in the car and took us to the border. They took all our phones and money and any valuables we had. Then they dropped us on the other side of the wire. Before releasing us, they beat us again and pointed to Turkey and told us to go there.

It seemed like the only thing that really interested them was whether we had money. They kept asking if we had money and when they found we didn’t have any left, they got angry and beat us and dropped us on the other side of the border. Then they fired into the sky to scare us and we ran to Turkey. They didn’t let us talk even. Once or twice we tried to talk to them or ask a question but before we managed to finish a sentence, they started beating us. We had no chance even to ask for asylum. The only thing they asked was which country we were from and whether we had money or expensive phones.[16]

II. The Bulgarian Containment Plan and the Principle of Nonrefoulement

Unpreparedness for the Crisis

Despite ample early warning signs, Bulgaria was unprepared for the increase in asylum seekers in 2013. A highly critical February 5, 2014 report by the Ministry of Interior said, “Until mid-2013 Bulgaria was completely unprepared for the forecasted refugee flow.”[17] It singled out the State Agency for Refugees (SAR) for wasting money and failing to provide sufficient and adequate accommodations for asylum seekers. The report said that European Refugee Fund monies were “spent on: awareness campaigns, brochures, trainings, seminars, specialized computers and software, but not for setting up accommodation places.”[18]

The report also said that in September 2013 an official inspection of the site of the proposed emergency reception camp at Harmanli (where more than 1,400 people would be held) found it “not suitable for setting up a wagon camp, there was no water and electricity.”[19]

Bulgaria’s “Plan for the Containment of the Crisis”

As the numbers of people crossing the Bulgarian border irregularly rose from 2,332 in September 2013 to 3,626 in October,[20] the Bulgarian Council of Ministers adopted what the council referred to as a “plan for the containment of the crisis resulting from stronger migration pressure on the Bulgarian border.” The containment plan listed as its main goals (1) reducing the number of illegal immigrants entering and residing illegally in Bulgarian territory; (2) containing the risks of terrorism and radical extremism, pandemics and epidemics, ethnic, religious, and political conflict, and criminality associated with illegal immigrants; (3) maintaining order, security and humane conditions at reception centers; (4) reducing the number of persons seeking protection in the territory of Bulgaria; (5) fast and efficient integration of refugees and beneficiaries of humanitarian status; (6) ensuring additional external resources; and (7) efficient communication with society.[21]

The initiatives for reducing the number of irregular migrants and asylum seekers included the construction of a 30-kilometer “barrier wall along the most sensitive sections of the [274-kilometer] State border” with Turkey,[22] and increasing the number of border patrols on the Bulgarian-Turkish border with the deployment of an additional 1,500 police.[23] In addition, the EU increased the number of border guards from other EU member states through the Poseidon land borders joint operation coordinated by Frontex, the EU’s agency for managing its external frontiers.[24] By January 15, 2014, Frontex had deployed an additional 170 experts to Bulgaria as part of the Poseidon land borders operation.[25]

The containment plan went into effect immediately and succeeded in stopping the influx almost entirely. On December 11, 2013, Human Rights Watch toured the police station at Elhovo, 28 kilometers north of the border. The station is the first stop for most people caught crossing the border irregularly. A few weeks earlier Amnesty International had toured the facility and reported that it was crammed with about 500 detainees.[26] At the time of our visit, it stood empty. All that remained were vacant cages and the detritus of filthy, torn bedding. (See The Elhovo Police Station.)

The Elhovo station chief told Human Rights Watch that no one had been apprehended on this 36-kilometer stretch of the border since November 6, when the new policy went into effect.[27] On February 7, 2014, the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) reported that only 99 people had crossed into Bulgaria from Turkey since the beginning of the year.[28]

The Ministry of Interior reported, “As at 31 January 2014 the influx of illegal immigrants was practically ceased.” The Ministry said that its large-scale police operation set out “to provide 100% protection of the most sensitive sections of the border.” Expressing its satisfaction on the success of preventing the entry of an estimated 15,000 people, the Ministry made no distinction between economic migrants and refugees in need of protection:

According to the evaluations of the National Operational Headquarters, had the specialized operation along the Bulgarian-Turkish Border not been performed, now we would have had more than 15,000 illegal immigrants and protection seekers in the territory of the country. Such a scenario of the situation would be a prerequisite for severe financial and social dimensions of the crisis.[29]

Human Rights Watch believes that the Bulgarian government has, since November 6, 2013, embarked on a systematic practice to prevent undocumented asylum seekers from crossing into Bulgaria to lodge claims for international protection. We base this finding on the following factors:

- a formal announcement of a plan, on November 6, 2013, to contain and reduce the number of asylum seekers and other migrants crossing the border irregularly, reiterated by the Ministry of Interior's report that the police under its authority set out "to provide 100% protection of the most sensitive sections of the border";

- the construction of a border fence along a critical segment of the border, that was due to be completed in mid-March 2014, coinciding with the announcement of that containment plan;

- the deployment of an additional 1,500 border guards, coinciding with the announcement of the containment plan;

- the precipitous drop in border crossing since the containment plan went into effect—in the month of October 2013, prior to the Nov. 6, 2013 announcement, 3,626 crossed the border irregularly, about 116 people per day. In the first five weeks of 2014, 99 crossed the border irregularly, a rate of about 2 ½ people per day.[30]

- Human Rights Watch’s interviews with 41 people giving accounts of 44 incidents in which at least 519 people were forcibly and summarily returned.

The government insists that the border is not closed to asylum seekers. In a February 5, 2014 letter to Human Rights Watch, Deputy Minister Angelov wrote:

It should be very clearly stated that the border with Turkey is not “closed” and won’t be “closed.” All border crossing points are open and accessible. The border control has been strengthened, inter alia by the deployment of additional police officers and technical equipment, in line with the Schengen catalogues and the integrated border management model of the EU. The objective is to prevent illegal migration and in the same time to encourage the asylum seekers to use more orderly and safe routes.[31]

This response is disingenuous. To reach an official border crossing on the Turkish border, a traveler must first pass through the exit control at one of the several Turkish border check points on the Turkish-Bulgarian border. Turkish border authorities do not allow undocumented people to exit through official crossing points, so they are not able to reach the Bulgarian entry check points. There is no way, therefore, for an undocumented asylum seeker to exit Turkey legally in order to seek asylum at Bulgaria’s official border crossing posts. The only actual option for undocumented asylum seekers (the vast majority do not have proper travel documents) is either to try to hide on a truck or other vehicle and pass irregularly through an official check point, or try to circumvent the official crossing points by making a clandestine crossing through the “green zone” stretch of border that the Bulgarian authorities are now working to fortify against irregular crossings.

The Principle of Nonrefoulement and the Right to Seek Asylum

Deputy Minister Angelov assured Human Rights Watch, “I am convinced we are acting within EU policies, respecting all legal rights, including the principle of nonrefoulement.”[32]

The 1951 Refugee Convention prohibits the return of refugees "in any manner whatsoever" to places where their life or freedom would be threatened.[33] Bulgaria is bound to the principle of nonrefoulement through its ratification of both the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol.[34] Further, Bulgarian domestic law, incorporating Bulgaria's international obligations as well as transposing the asylum directives of the European Community, additionally and explicitly binds Bulgaria to the principle of nonrefoulement.[35]

Pushbacks at the border do not nullify the nonrefoulement obligation. UNHCR’s Executive Committee, comprised of 87 states, expresses the consensus of state practice with regard to the international refugee regime through formal conclusions. As early as 1977, the Executive Committee issued a formal conclusion that "[r]eaffirms the fundamental importance of the observance of the principle of nonrefoulement-both at the border and within the territory of a State…"[36]

As documented in this report, Bulgarian border police have been summarily and forcibly expelling third country nationals to Turkey without giving them the opportunity to seek asylum (see Violent, Summary Returns to Turkey). The Schengen Borders Code (Regulation (EC) 562/2006) holds not only that member state border guards must “fully respect human dignity,” but also that refusal of entry at a border “shall be without prejudice to the application of special provisions concerning the right of asylum and to international protection” and that “persons refused entry shall have the right to appeal.”[37]

Similarly, the EU’s Returns Directive (2008/115/EC) prohibits member states from returning asylum seekers, saying they “should not be regarded as staying illegally on the territory of a Member State until a negative decision on the application…has entered into force.”[38] Although the Returns Directive, article 2(2)(a), allows member states not to apply the directive to migrants who irregularly cross the external borders of the EU, article 4(4)(a) and (b) says that they are still required to limit the use of coercive measures, to take into account the needs of vulnerable persons, to provide decent detention conditions, and to respect the principle of nonrefoulement.

The border pushbacks documented in this report follow no proper procedure and carry a negative presumption that irregular border crossers are not seeking asylum when the presumption, at least with regard to people fleeing Syria and Afghanistan, ought to be that they are.

Is Turkey a Safe Third Country?

Bulgaria’s deputy minister of interior, Plamen Angelov, told Human Rights Watch that the November 6 containment plan involved close cooperation with Turkey as “the key element” in preventing third country nationals from penetrating Bulgaria’s borders. He said that Bulgaria had already greatly improved its partnership with Turkey on border controls. Angelov said that the coordination plan, now in effect, but continuing to develop, involves heightened surveillance and communication between border guard forces on both sides of the border and foresees joint border patrols. Angelov said, “Turkey is a safe country.”[39]

The nonrefoulement obligation applies not only to direct return into the hands of persecutors and torturers, but to indirect returns as well. That is, states cannot absolve themselves of responsibility by sending a refugee to a non-persecutory state that in turn sends them to a third persecutory state.[40]

International refugee law permits the return of an asylum seeker to a third country, but only if that country “agrees to admit him to its territory as an asylum seeker and consider his request” and is able and willing to provide the asylum seeker with effective protection.[41]Turkey does not meet this standard for several reasons.

First, Turkey is the only country that retains the original geographical limitation of the 1951 Refugee Convention to refugees from Europe.[42]Consequently, under Turkish law, it is not possible for a refugee from Syria, Afghanistan, or any other non-European country to be recognized as a refugee and granted asylum. At best, Turkish law regards non-European refugees as asylum seekers who can never be granted asylum on Turkish territory. Therefore Turkey cannot be considered as a safe third country under EU law which stipulates that a third country can only be considered safe if “it has ratified and observes the provisions of the Geneva Convention without any geographical limitations.”[43]

Second, Bulgaria’s Law on Asylum and Refugees defines a safe third country as one where the applicant “has resided” and where there is “a possibility to claim a refugee status and upon granting it to enjoy a protection as a refugee.”[44] Since most of the asylum seekers we interviewed in Bulgaria had not resided in Turkey and Turkish law excludes the possibility that non-European asylum seekers can claim refugee status, Turkey cannot be regarded as a safe third country under Bulgarian law.

Third, Bulgaria does not have a bilateral readmission agreement with Turkey for the orderly return of third country nationals and Turkey has not formally agreed to admit third country nationals from Bulgaria with the guarantee that their asylum claims would be examined according to the same standards that apply in Bulgaria.[45]

The Right to Asylum in EU and Bulgarian Law

Bulgaria is bound by EU law and its own Constitution to respect the right to asylum.[46]The “right to asylum” is enshrined in article 18 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, as amended by the 2007 Treaty of Lisbon. With the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon in December 2009, the Charter became legally binding on EU member states when they apply EU law and the right to asylum became an enforceable right under the EU’s legal order.[47]Article 27(2) of the Bulgarian Constitution binds the Bulgarian government to grant asylum, saying, “The Republic of Bulgaria shall grant asylum to foreigners persecuted for their opinions or activity in the defense of internationally recognized rights and freedoms.”[48]

This means that in addition to its obligation to respect for the principle of nonrefoulement, Bulgaria is also obligated to consider asylum requests and cannot shirk that responsibility by pushing asylum seekers to Turkey, which has not similarly bound itself to respect the right to seek and enjoy asylum.

Is Bulgaria Faced with a Mass Influx?

The “plan for the containment of the crisis resulting from stronger migration pressure on the Bulgarian border” adopted by Bulgaria’s Council of Ministers presumed that there was a migration crisis on the Bulgarian border. A little perspective on Bulgaria’s migration crisis is in order.

In the first five weeks of 2014—at a time when 99 asylum seekers succeeded in crossing from Turkey to Bulgaria—more than 20,000 Syrian refugees entered Turkey, the country to which Bulgaria was pushing back asylum seekers. The number of Syrian asylum seekers entering Turkey in the first five weeks of 2014 was roughly double the number of all asylum seekers entering Bulgaria during the whole of 2013.[49] By the end of 2013, Turkey had registered more than 580,000 Syrian refugees and another 44,800 non-Syrian asylum seekers.[50] UNHCR registered more than 860,000 Syrian refugees in Lebanon in 2013; this would be the equivalent of 1,482,000 refugees suddenly arriving in Bulgaria.[51] Bulgaria hosted 6,832 registered asylum seekers, as of March 19, 2014.[52]

Bulgaria, of course, is faced with a humanitarian challenge and its capacity to meet that challenge is limited. But the European Union has helped to bolster its capacity and the humanitarian situation inside the country has improved for the refugees and asylum seekers who have already entered.[53] Even with limited capacity, however, Bulgaria must meet basic, minimal obligations to respect the rights of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants. As this report documents, it has failed to do that.

III. Abuses and Detention Conditions in Border Police Stations

The Elhovo Police Station

Until they started systematically returning migrants summarily to Turkey, the usual practice prior to November 6, 2013 was for Bulgarian border guards to take apprehended migrants, including families with children, to a police station near the border administered by the General Directorate of the Border Police (GDBP). Nearly all the migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Bulgaria said that border police who apprehended them first took them to the Elhovo police station about 28 kilometers from the Lesovo checkpoint on the Turkish border.

A 24-year-old Palestinian from Syria who had been left for two days to sleep at the border before being pushed into Turkey on September 27, 2013, described what happened after the pushback when his group crossed back into Bulgaria some distance from where they had been expelled. He said that his group of 18 reached a Bulgarian village and that the villagers called the police. Black-uniformed policemen with POLICE written across their chests came and took them to Elhovo:

We were fingerprinted and signed papers. The women were kept in the building, but the men were made to sleep outside. It was very cold. There was a fence around the area. We were just on the earth, on the soil. There were no blankets. We told the police one of the men was ill. The police told us to make him run to warm him up. They gave us a food packet for one day consisting of biscuits, bread, and yogurt. I was there for three days.[54]

At the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit, December 10, 2013, the facility was completely empty (see Bulgaria’s “Plan for the Containment of the Crisis”). The station chief first took us to see a modern and clean cell block, each of the cells having two or three beds and its own toilet. Down the same hallway were offices for fingerprinting, photographing, and interviewing new arrivals, including one office where Frontex guest guards and interpreters working with them conduct nationality determination interviews. The chief informed us that no one is held longer than 24 hours in this facility.

We asked where migrants were accommodated when their numbers exceed the available space in the cell block. The police chief then took us to an indoor basketball court, where we observed the detritus of what only a matter of days or weeks before had been filled with migrants.[55] The gym was divided by five large cages, one for women and children, we were told, and the other four divided for men according to broad “nationality” categories: “Syrians” (including Iraqis and Palestinians), “Afghans” (including Iranians and other South Asian groups), “Algerians” (meaning north Africans), and “Africans.” All that remained were filthy and torn blankets, thin, dirty mattresses, and the wooden, graffiti-filled planks on which they slept.[56]

Many people from different locations described to Human Rights Watch their stay in the basketball court. A 31-year-old Afghan man who was held there with his sister and her two children described his 9-day stay in October 2013:

They gave us food one time, the first day. Every day we asked for food. They didn’t give any, even for the children. We were terribly hungry for three days. On the fourth day, they let us to go to a market to buy food with our own money and to bring it back to the camp. We could only go to the market once every three days. We did not know how long we would be there. Some people had been there for 15 days. We could not sleep. We had no blankets. I had no blanket. It was very cold. I slept on the floor. At most I could sleep for one hour, then stand up, then try to sleep again. After three nights I got a blanket. But then [someone] robbed our food and stole my blanket. It was very dirty. There were insects. The police pushed us but did not hit us because there were cameras watching. But one time I saw them take two young people to a room where there were no cameras and hurt them.[57]

An Afghan who said he was a 17-year-old unaccompanied child described what happened after Bulgarian border guards caught him on November 11, 2013:

They brought us to the first camp. We were there almost nine days, but with no food for eight days. We had to buy food. I had to share a bed and a blanket with three other people. Sometimes I slept on the floor. There was no shower, just a water tap, and just a dirty toilet on the floor that we had to ask permission to use. I never said a word [to the guards] but I saw them use tasers on other people who talked to silence them.[58]

The nightmare of Elhovo began for many migrants we spoke to during their processing at the police station. A 26-year-old single Algerian man described his treatment at the Elhovo police station after being apprehended at a bus station inside Bulgaria on October 21, 2013:

One of the policemen in plain cothes took us to a camp about 10 minutes from the bus station. It sounded like “Ox bo” [referring to Elhovo]. I spent 12 days in hell there. I was beaten. I had to buy food with my own money. On the first day they beat me. They asked me how I got to the bus station. They used an electric taser shock on me. They asked questions, how I got to the bus station on my own. I was standing during the interrogation. One questioned me and the other beat me with his fist or with the electric prod. He hit me three times with electric shocks: on my arm, my side, and my leg. [59]

A 29-year-old stateless man from North Africa recalled that at Elhovo “they used an electric taser to make you move. I was hit on the leg by the taser.” [60] A 20-year-old single Moroccan who said that he was caught crossing the border on September 9, 2013 said that the beatings started when he was first apprehended and continued at Elhovo:

The police at the border beat me with a police stick. A group of five guards beat all of us. Our group included Iraqis and Syrians. They broke one guy’s arm. They took us to the first camp, Elhovo. It was very overcrowded. We spent six days there but they only gave us food on the first day. The police there were insulting. They used bad words. If you asked for water, they beat you. I saw them beat a sick guy who had asthma. He was sick and asking to go to the doctor. They did not send him to a clinic. Nothing.[61]

A 33-year-old Syrian man who entered Bulgaria in early November 2013 said that Bulgarian border police at the Elhovo basketball court detention facility shocked him with a taser. His ill-treatment started at the Elhovo police station after a Frontex guest guard from Germany turned him over to the Bulgarian border police:

The man who caught me was a German in a guard uniform with an EU badge. He was very polite. He called for the Bulgarian border police to come get us. I could understand in German that the guard who caught us told the Bulgarian border police to give us food and water. They didn’t give us anything. They took us to a police station and held us there for 48 hours and didn’t give us any food. They wouldn’t even allow us to buy food. I just ate the food I was carrying with me….

I told the police [at the basketball detention center] I wanted to use the toilet. The guard said no, he would not let me use the toilet. After that I walked some distance outside the building to urinate, but the guard saw me and used his taser on me. He shocked me with it twice. First, when I was urinating and then to make me move faster. He hit me on the side of my leg and on my back. It was a strong taser. I still feel the pain of the electric shock on my back. The other guards were about 10 meters from us when this happened. They just watched and laughed.

In general, the treatment here [at Harmanli] is very bad. They don’t let you breathe on your own here... Of course, it is better than my country. I am escaping war. But now I prefer to die than to stay in these conditions.[62]

Family groups fared no better at the Elhovo police station. A 17-year-old girl from Pakistan who crossed into Bulgaria with her family in mid-October 2013 described her family’s treatment during their 10 days at Elhovo:

We didn’t get any food there. It was horrible and the family was split up. My father and brother stayed in one cage, and me and my mother and sister in another cage. The police used electric sticks to beat people. They beat my father. Two police officers beat him because he complained about the lack of medicines and the bad conditions and because he asked for information. They beat him several times with the stick upon his shoulder. My father is diabetic and they only gave him one pill. He’s sick and he needs medicine.[63]

The detritus after weeks of overcrowded detention in the now empty basketball court at the Elhovo Regional Directorate Border Police. ©2014 Human Rights Watch

A 35-year-old Afghan mother of three children who with her family spent eight days in the “cage camp” said that in addition to “not giving us any food” and poor conditions, the police were rude and violent:

A police officer kicked me twice in my stomach. Why did they do that? They called my number out and I was looking for my shoes and therefore was a bit late in replying to my number being called out. As I was crouching down, the police officer came over and kicked me in the stomach. I also saw three or four times people were hit with an electric shock when they asked to go to the toilet.[64]

Scraps of mattress on the plywood beds at the Elhovo basketball detention center. ©2014 Human Rights Watch

Not everyone interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the Elhovo police had beaten them, but every person interviewed who had been held at Elhovo said that they were only given food, at most, for one day regardless of how long they spent there, and that they were exposed to the cold, in some cases being forced to remain on the bare ground, outside late into the night before being allowed into a building.

Human Rights Watch asked the Ministry of Interior how many foreigners were held at Elhovo for more than 24 hours and for the average length of stay for detainees in 2013. The Ministry of Interior said, “Persons are not detained in the Border Police Stations for more than 24 hours,” and asserted that they are all transferred after 24 hours to the State Agency for Refugees (SAR)-administered Registration and Reception Centers (RRC) or to the Ministry of Interior’s Special Centers for Temporary Accommodation of Foreigners (SCTAF) “depending on whether they have applied for refugee or humanitarian status or not.”[65] The Ministry added a hypothetical: “If exceptionally the persons could not be accommodated in the centres of SAR, they could stay in a hotel.”

Human Rights Watch also asked the Ministry of Interior to provide information on the amount and type of food provided by state authorities per day and per person at the Elhovo police station, and whether this amount meets state guidelines for detainees in state custody. The Ministry of Interior responded, “All persons having illegally crossed the state border receive a warm food provided by the Bulgarian authorities with a value of 3.50 leva [about 1.77 euro or US $2.35] for adults and 5.23 leva [about 2.65 euro or US $3.50] for minors” per day.[66]

Elhovo Distribution Center

After the initial—supposedly 24-hour—stay at the Elhovo police station, migrants are usually transported a short distance to a three-story building that has been converted into a detention center known as the Elhovo Distribution Center. On each floor is a row of large cells that at the time of the Human Rights Watch visit held about 25 people each. The hallway is barred and separated by a guard station. The purpose of the center is to hold migrants temporarily, to interview them to ascertain who they are, and to transfer them either to one of the detention centers or to a registration and reception center.

Human Rights Watch researchers visited the center on December 10, 2013. The guards took down the names of every detainee whom we interviewed. The interviews took place in corners of one of the offices that were used by staff. Although the interviews were all private and out of earshot of any guards or staff, staff were able to see the detainees who were being interviewed. During the course of the day, Human Rights Watch was able to enter the living quarters of the detainees, to walk down the hallway and look at the rooms, which were overcrowded and dirty.

Human Rights Watch observed a heavy presence of black-uniformed guards at Elhovo, all of whom were armed with batons. The administrator of the center, a woman in civilian clothes, told us that the facility had a capacity for 240 but on the day of the Human Rights Watch visit was holding 300. She said that Harmanli and other camps were full, so they were not able to distribute migrants as quickly as before. She said that normally people are only detained there for a maximum of several days, but that people at the present time were being held there for as long as 18 days.[67] She said that priority for placement is given to Syrian families, but that men, particularly if they are neither Syrian nor Afghan, have longer waits. She said that most people in the facility were Syrian or Afghan. She also said that there were no separate accommodations for unaccompanied children, and that “conditions are not perfect.”

The most common complaints of the detainees at Elhovo (including former detainees) were about the food (Human Rights Watch observed the watery gruel that was being served during our visit); the dirty toilets (about 30 or 40 people per toilet) that are inaccessible at night because the room doors are closed and the toilets are at the end of the corridor; bad ventilation; and tension and conflict among the detainees.

IV. Abuses and Conditions in Migrant Detention Centers

From the Elhovo Distribution Center, and other police stations and distribution points, migrants, including children and their families, are sent either to a registration and reception center under the auspices of the State Agency for Refugees or to one of two detention centers run by the Ministry of Interior: Busmantsi, on the outskirts of Sofia, or Lyubimets, about 30 kilometers from the Turkish border. The Ministry of Interior calls these two centers Special Centers for Temporary Accommodation of Foreigners (SCTAF).

Detainees in both facilities had little understanding why they were being detained in these prison-like conditions, how long they would remain detained, and the process for release. For those who have lodged asylum claims, one common way to be released from detention has been to pay Bulgarian middlemen who present themselves as “lawyers” to establish an address outside the facility (see Chapter VII, Asylum Seekers Living outside the Centers). [68] Many of these addresses prove to be fictitious. Meanwhile those seeking release are required to sign a waiver of entitlement to any public social services, including the 65 leva monthly stipend and housing in an open center. As a result many asylum seekers become homeless and destitute after their release from detention.

Busmantsi SCTAF

Located on the outskirts of Sofia, Busmantsi SCTAF is used primarily to hold migrants pending their deportation. With a capacity for 400 detainees, the facility held 486 detainees on the first day Human Rights Watch visited. The commander said that it had been over capacity for the past six months. The Ministry of Interior said that 380 minors were held there in 2013. [69] Human Rights Watch was able to tour the living quarters and witnessed the overcrowding of about 30 men in a room. There is little space to sit in the rooms, but there is a small separate room with a television set and a recreation yard that detainees were using during the visit. The bedding looked worn and dirty. One of the dormitory rooms had no glass in one of the windows, and the men there were using a piece of a bedsheet to shield themselves from the cold wind.

Busmantsi Special Center for the Temporary Accomodation of Foreigners (SCTAF) ©2014 Human Rights Watch

The most common complaints we heard related to the poor quality of food and to fear or annoyance about other detainees in the facility.

One of the most common complaints of detainees at Busmantsi SCTAF is that they do not know why or how long they will be held there and what steps they need to take to facilitate their release. A 27-year-old Syrian man told Human Rights Watch that he did not feel safe in the room in which he was being held with 35 other men. He said that some detainees talked loudly and made noise so he could not sleep and stole his clothing and other belongings. But he said that the lack of communication, lack of information, and uncertainty were his biggest problems:

I report when my things are stolen and the guard says, “It is not my problem.” I escaped the jail of Syria to come to another jail here. They tell me this is not a prison but a closed camp. The only difference is that with a prison you have a day in court. Here I am a prisoner without a judgment. I want to go out for medical care, but nobody is answering us or telling us anything. I want to be released but no one will help me. If people in Syria knew the conditions here, they wouldn’t come here.[70]

One detainee we spoke to at Busmantsi SCTAF, a Syrian, described the “bad conditions:”

There are too many people in one room and too many cockroaches. It’s a very dirty place and if new people come here, they have to sleep on the floor. I can’t get to my medicines without bribing the guard. When the guards get mad, they press people up against the wall and shout. [71]

A former detainee at Busmantsi SCTAF, a 32-year-old chemist from Syria, now at one of the reception centers, told Human Rights Watch about the three-months he spent at Busmantsi:

Busmantsi was very dirty, not secure. [Someone] stole my dirty bedding. After two weeks I got a sheet. The food was not good, it was too little. Bulgaria is a poor country, but the guards do not organize anything. They let [other detainees] butt in line and take our food. The Algerians and Africans fought. The health clinic was very simple. I wanted to check my high blood pressure, but the monitor didn’t work. The medicine was not sufficient.

I kept asking for an interview for refugee status. The guard told me no. I went to him three times in an hour. He pushed me. Then I told him not to push me. Then he beat me. First he hit me with his hand and then he kicked me. [72]

Violence and Solitary Confinement

The authorities at Busmantsi SCTAF sometimes use solitary confinement to discipline detainees. One detainee, a 40-year-old Algerian, said he spent 15 days in solitary confinement there:

The first day, they really beat me a lot. I felt nearly dead from it. They hit me on the chest, my side, my head. They hit me with their fists and kicked me. The cell had one window. Some days I was not allowed to leave the cell at all. During the 15 days I was in there, I was allowed out maybe two or three times for about a half hour each time.[73]

Another Algerian man described highly abusive treatment while he was held in segregation in Busmantsi for eight days:

The police officer brought me to the isolation cell. He locked the door and covered the camera and started hitting me on my back with his electric truncheon. Outside, two officers were beating up on my friend. The officer hit me very hard several times. I lost count. This happened [date withheld]. The police officer was crazy. While I was in solitary confinement the police took my food rations. The officer would take my bread and apples off my plate. They threw me a dirty blanket. I have scabies on my leg and it’s very bad so I need medical attention. After the beating, I wanted to go to the doctor, but when I asked the police, he just told me I was a donkey and pushed me on my shoulder. [Human Rights Watch observed and photographed the man’s open and infected wound.][74]

Lyubimets SCTAF

The Lyubimets Special Center for the Temporary Accomodation of Foreigners (SCTAF), located near the town of Svilengrad on the border with Turkey, had a detainee population of 460 on the day of our visit, although the SCTAF has a 300-bed capacity. The center commander told us that the center had been over capacity by an average of about 50 persons during the past six months. He said that detainees are held, on average, for 60 to 65 days, but that 10 of the detainees currently were being held for as long as 90 days. He said that most of the detainees were from North Africa and that on the day of our visit there were no Syrians in the facility. He said that all of the detainees crossed the Turkish border. He also said that no deportations occur directly from Lyubimets, but only from Busmantsi SCTAF. He said that the facility only houses males, and that it included unaccompanied boys who were not segregated from adults. [75] The Ministry of Interior said that Lyubimets detained 912 minors in Lyubimets in 2013. [76]