“We are the Walking Dead”

Killings of Shia Hazara in Balochistan, Pakistan

Glossary

|

Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) |

The BLA is a Baloch nationalist armed separatist group based in the province of Balochistan. It has been in armed conflict with the Pakistani government since 2006. |

|

Crime Investigation Department (CID) |

The CID is a department of the Pakistan police with specialized functions and mandate for dealing with terrorism, sectarian violence, and organized crime. |

|

Eid-ul-Fitr |

Eid-ul-Fitr is one of the most important religious days in the Muslim calendar and marks the end of the holy month of Ramadan (the month of fasting). The Eid-ul-Fitr is celebrated by all Muslim sects. |

|

Field Investigation Unit (FIU) |

The FIU refers generally to a specialized investigation unit of the intelligence services, particularly Inter-Services Intelligence. |

|

Frontier Corps |

The Frontier Corps is a federal auxiliary paramilitary force that acts as a unit of the Pakistan Army. It is led by senior serving army officers but falls under the formal jurisdiction of Pakistan's federal interior ministry. |

|

Intelligence Bureau (IB) |

The IB is the intelligence agency responsible for internal/domestic matters and is often viewed as the intelligence agency with the most civilian oversight and control. |

|

Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) |

Under military command, the ISI is Pakistan’s largest and most powerful intelligence agency and is responsible for national security intelligence gathering. |

|

Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) |

The ISPR is an administrative unit of the military responsible for issuing statements regarding military issues and for general public relations regarding military matters. |

|

Jamiat-e-Ulema-e-Islam-Fazlur Rehman (JUI-F) |

The JUI-F is a political party based on hardline Sunni Deobandi Islamic doctrine. It is viewed as the “parent” political party of the Taliban movement, though it no longer exercises meaningful influence over the Taliban. It has been a coalition partner in successive governments since 2002. |

|

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) |

The LEJ is a militant extremist Sunni Deobandi group formed in 1996 as a breakaway faction of the sectarian militant Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP). The LeJ views Shia Muslims as heretics and their killing as religiously justified. |

|

Military Intelligence (MI) |

The MI is an intelligence agency controlled and supervised directly by the Pakistani military; it consists primarily of serving military officers. |

|

Maintenance of Public Order (MPO) |

The MPO ordinance is a preventive detention measure that allows the state to override standard legal procedures and due process of law in situations in which the government deems any person a threat to public order or safety. It allows the government to “arrest and detain suspected persons” for up to six months for a range of offenses. |

|

Muharram |

Muharram is the first month of the Islamic calendar, which the Shia community marks with a variety of mass outdoor religious rituals mourning the massacre of Prophet Mohammad’s grandson and his family. The event marks the origin of the Shia-Sunni schism in Islam. |

|

Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) |

The PML-(N) is a political party headed by current Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. It emerged in 1990 as the dominant faction of a party created by former military ruler General Ziaul Haq in 1986. |

|

Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) |

The PPP is a left-of-center political party formed in 1967 by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and later headed by his daughter Benazir Bhutto. The PPP controlled Pakistan’s federal government and Balochistan’s provincial government between March 2008 and March 2013 under the leadership of President Asif Zardari. |

|

Sipah-e-Muhammed (SM) |

The SM is a militant Shia sectarian group formed in the early 1990s. It has targeted a handful of Sunni extremist militant leaders over the last decade but is not known to attack or kill civilians. |

|

Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP) |

The SSP is a militant Sunni Deobandi group formed in 1980 with the declared aim of containing Shia influence in Pakistan after the 1979 Iranian revolution. |

|

Sunni Deobandi school of thought |

The Deobandi school of thought in Islam came to prominence with the founding in 1866 in India of Darul Uloom Deoband, regarded as the first “modern” Islamic Madrassah. It advocates a hardline Sunni interpretation of Islam as practiced by the Taliban. |

|

Tehrik-e-Nifaz-e-Fiqh-e-Jafaria (TNFJ) |

The TNFJ is a Shia Muslim political organization formed in 1979 with the declared aim of safeguarding the interests of Shia Muslims. |

|

Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TPP) |

The TTP is a militant Islamist umbrella group claiming inspiration from the Afghan Taliban, though it is operationally autonomous. It formally declared its existence in 2007. It and affiliated groups are responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of Pakistani civilians and more than 10,000 military personnel. |

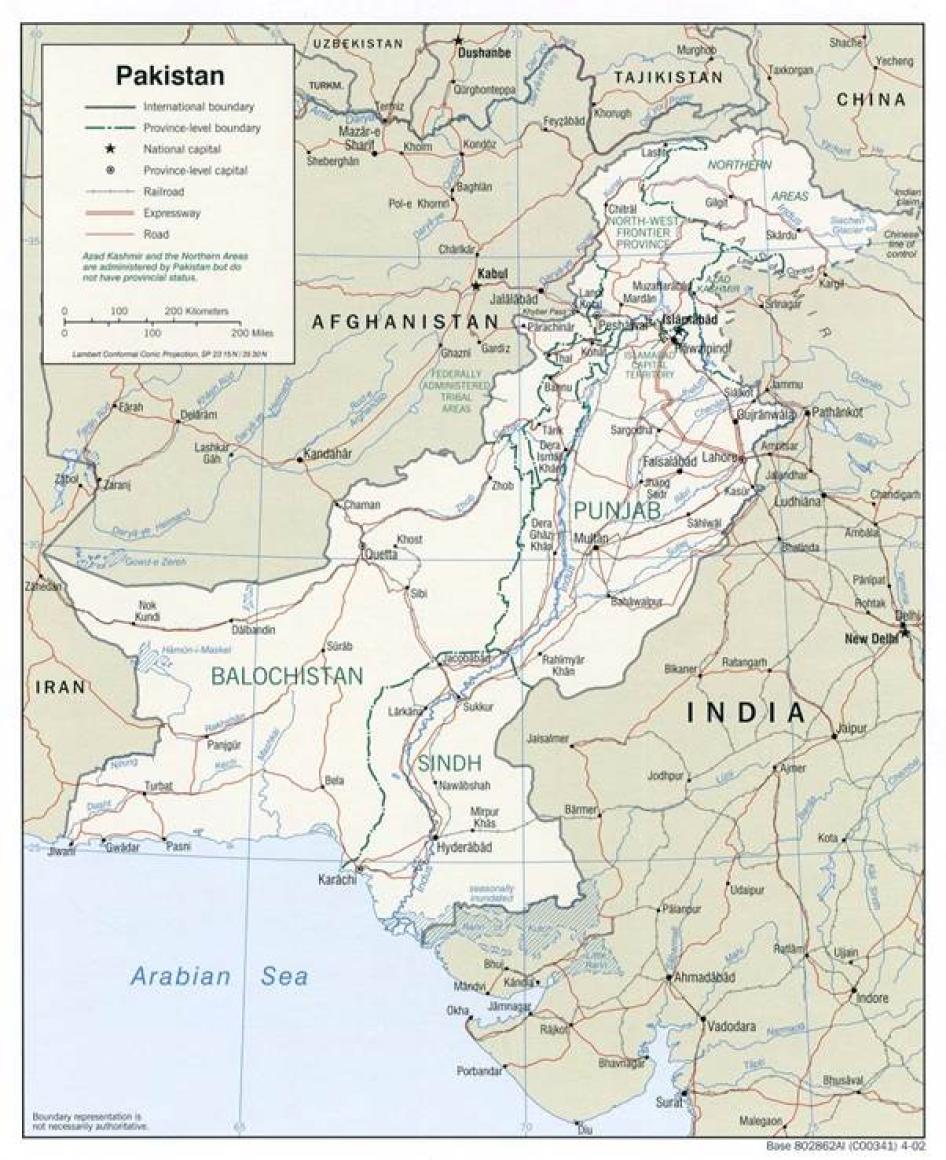

Map of Pakistan

Courtesy of University of Texas at Austin © 2002

Map of Balochistan

© Human Rights Watch

Summary

They asked who the Sunnis were, asking for names. Then they told the Sunnis to run. We jumped and ran for our lives. But while they allowed everybody who was not a Shia to get away, they made sure that the Shias stayed on the bus. Then they made them get out and opened fire.

—Haji Khushal Khan, bus driver, Balochistan, December 2011, Quetta

On September 20, 2011, near the town of Mastung in Pakistan’s Balochistan province, gunmen stopped a bus carrying about 40 Shia Muslims of Hazara ethnicity traveling to Iran to visit Shia holy sites. After letting the Sunnis on the bus go, the gunmen ordered the Hazara passengers to disembark and proceeded to shoot them, killing 26 and wounding 6. Later that day, gunmen killed three of the Hazara survivors as they tried to bring attack victims to a hospital in Quetta. The Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ), a Sunni militant group, claimed responsibility for the attack. The Mastung shooting marked the first time—but not the last—that the LeJ perpetrated a mass killing of Hazara after first separating them from Sunnis.

Asked how he intended to “stem the tears” of the Hazara community, Balochistan’s then-chief minister, Aslam Raisani, told the media, “Of the millions who live in Balochistan, 40 dead in Mastung is not a big deal. I will send a truckload of tissue papers to the bereaved families. I’d send tobacco if I weren’t a politician.”

In recent years, Pakistan’s Shia community, which constitutes some 20 percent of the country’s overwhelmingly Muslim population, has been the target of an alarming and unprecedented escalation in sectarian violence. Armed Sunni militants have conducted numerous shootings and bombings across Pakistan, killing thousands of Shia citizens. Militants have targeted Shia police officers, bureaucrats, and a judge, Zulfiqar Naqvi, who was killed by motorcycle-riding assassins in Quetta on August 30, 2012. Human Rights Watch recorded at least 450 killings of Shia in 2012, the community’s bloodiest year; at least another 400 Shia were killed in 2013. While sporadic sectarian violence between Sunni and Shia militant groups has long persisted in Pakistan, attacks in recent years have been overwhelmingly one-sided and primarily targeted ordinary Shia going about their daily lives.

This report documents Sunni militant attacks on the mostly Shia Hazara community in Pakistan’s southwestern province of Balochistan from 2010 until early 2014. The Hazara in Balochistan, numbering about half a million people, find themselves particularly vulnerable to attack because of their distinctive facial features and Shia religious affiliation. More than 500 Hazaras have been killed in attacks since 2008, but their precarious position is reflected in the increasing percentage of Hazara among all Shia victims of sectarian attack. Approximately one-quarter of the Shia killed in sectarian violence across Pakistan in 2012 belonged to the Hazara community in Balochistan. In 2013, nearly half of Shia killed in Pakistan were Hazaras.

The sectarian massacres have taken place under successive governments since Pakistan’s return to democratic governance in 2008. To many Hazara, the persistent failure of the authorities at both the provincial and national levels to apprehend attackers or prosecute the militant groups claiming responsibility for the attacks suggests that the authorities are incompetent, indifferent, or possibly complicit in the attacks.

While there is no evidence indicating official or systemic state patronage of the LeJ, the country’s law enforcement agencies, military, and paramilitary forces have done little to investigate them or take steps to prevent the next attack. While the LeJ attacks are abuses by private actors, international human rights law places an obligation on governments to adequately investigate and punish persistent serious offenses—or be implicated in violations of human rights.

The bloodiest attacks, resulting in the highest death tolls recorded in sectarian violence in Pakistan since independence in 1947, occurred in January and February 2013, when bomb attacks in Quetta killed at least 180 Hazaras. The LeJ claimed responsibility for both attacks.

On January 10, 2013 the suicide bombing of a snooker club frequented by Hazaras killed 96 and injured at least 150. Many of those killed and injured were the victims of a car bomb near the club that exploded 10 minutes after the first, striking those who had gone to to the aid of the wounded. Initial government indifference and apathy was met by the Hazara community’s refusal to bury its dead in protest, sparking country-wide demonstrations in solidarity. Three days after the attack, Pakistan’s government suspended the provincial government and imposed federal rule in response to demands of the Hazara community.

On February 17, 2013, at least 84 Hazara were killed and more than 160 injured when a bomb exploded in a vegetable market in Quetta’s Hazara Town. The perpetrators had remotely detonated hundreds of kilograms of explosives rigged to a water tanker when the market was packed with shoppers.

Survivors and victims’ family members say that the ongoing attacks have caused profound harm to Balochistan’s Hazara community. Increasingly, members of the Hazara community have been compelled to live a fearful existence of restricted movement that has created economic hardship and curtailed access to education. That oppressive situation has prompted large numbers of Hazara to flee Pakistan for refuge in other countries.

These hardships are compounded by elements within Pakistan’s security agencies who appear to view the Hazara community with suspicion. Speaking on condition of anonymity, retired members of the paramilitary Frontier Corps, Balochistan’s principal security agency, described the Hazara to Human Rights Watch as “agents of Iran” and “untrustworthy.” One former official even suggested, without evidence, that the Hazara “exaggerated” their plight in order to seek asylum abroad and “gain financial and political support from Iran to wage its agenda in Pakistan.”

The Lashkar-e-Jhangvi has claimed responsibility for most of the attacks and killings. It has also killed with increasing impunity members of the Frontier Corps or police assigned to protect Shia processions, pilgrims, or Hazara neighborhoods.

The rhetoric of the LeJ is both anti-Shia and anti-Iran. The LeJ long enjoyed a close relationship with Pakistan’s military and intelligence agencies, which encouraged it in the 1990s to forge strong links with armed Islamist groups fighting in Kashmir and Afghanistan. Almost the entire leadership of the LeJ fought alongside the Taliban in Afghanistan. In 1998 it aided the Taliban in the massacre of thousands of Hazaras living in Mazar-e-Sharif.

However, in recent years that relationship appears to have fractured in some parts of the country and generally become more complicated as the LeJ joined the network of the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (the Pakistani Taliban, TTP) and has been involved in high profile attacks on Pakistani military personnel and installations, government officials, infrastructure, and civilians. As the TTP has intensified attacks on Pakistan, the LeJ has emerged as its principal militant partner in Balochistan and, more crucially, in Pakistan’s powerful and prosperous Punjab province, where it is deeply entrenched and has its origins. The Pakistani military maintains that it has no links, formal or informal, with the LeJ, and that there is no anti-Hazara or anti-Shia sentiment within the FC or other military agencies operating in Balochistan.

Since 2002, the operational chief of the LeJ has been Malik Ishaq. He has been accused of involvement in some 44 attacks that resulted in the killing of some 70 people, mostly Shia, but has never been convicted and has been acquitted on all charges in 40 of these cases, amid allegations of violence, threats against witnesses, and fear among judges. The failure to bring Ishaq to justice underscores seriously failings in Pakistan’s criminal justice system and the impunity that thrives as a result of this failure.

Caption: Malik Ishaq. Photo courtesy of Reuters.

While Pakistan and Balochistan authorities claim to have arrested dozens of suspects in attacks against Shia since 2008, only a handful have been charged. Virtually all members of the LeJ leadership operate with impunity, continuing to play leadership roles even when in custody awaiting trial. A number of convicted high-profile LeJ militants and suspects in custody, including its operational chief in Balochistan, Usman Saifullah Kurd, have escaped from military and civilian detention in circumstances the authorities have been unable to explain.

While some enhanced security cover in Quetta’s Hazara neighborhoods and to Shia pilgrims travelling to Iran has been in evidence since a new provincial government assumed office in Balochistan in June 2013, the situation of the Hazara and other Shia in Balochistan has not improved. In January 2014, 28 Hazara were killed in a suicide bombing attack in Mastung on a bus carrying pilgrims returning from Iran. The government responded by temporarily suspending the bus service to prevent further attacks. On June 9, 2014, at least 24 Shia pilgrims from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province were killed in a gun and suicide attack on a transit hotel in the Balochistan border town of Taftan. The attackers were killed in retaliatory fire by FC personnel. Pakistan’s interior minister, Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan, responded to the atrocity in parliament by suggesting that the pilgrims, mostly extremely poor, should find alternative modes of travel by air or ferry as it was impossible to secure the 700 kilometer bus route.]

The Hazara have been targeted to be killed, sometimes blown up by bombs, while participating in religious processions, praying in mosques, going to work, or just going about daily life. Hounded into virtual ghettoization in the Hazara neighborhoods of Quetta, they have then suffered the same fate in the ghettos or when going to and returning from pilgrimages to Iran, and staying in hotels along the way. There is no travel route, no shopping trip, no school run, no work commute that is safe.

Meanwhile, Pakistani authorities have responded, at best, by suggesting that the Hazara accept open-ended ghettoization, ever increasing curbs on movement and religious observance, and ongoing economic, cultural, and social discrimination as the price for staying alive. Yet the LeJ still finds ways to attack and kill.

The fact that repeated attacks on Hazaras go uninvestigated and unpunished and that elements within the security services and elected officials alike display discriminatory attitudes and hostility toward them generates a belief among many Hazara we interviewed that the military, Frontier Corps, and other state authorities in Balochistan are at best indifferent and at worst complicit in the attacks. These views gain traction from the fact that attacks and impunity continue despite the presence of significant military, paramilitary, and civilian security forces and intelligence agencies in Balochistan.

This egregious abuse can only end when the LeJ is disarmed and disbanded and its leadership and militant cadres held accountable. Pakistan’s international partners should press the Pakistani government to uphold its international human rights obligations and promote good governance by investigating sectarian killings in Balochistan and prosecuting all those responsible. Pakistan’s political leaders, law enforcement agencies, administrative authorities, judiciary, and military need to take immediate measures to prevent these attacks and end the LeJ’s capacity to kill with impunity. If the Pakistani state continues to play the role of unconcerned or ineffectual bystander, it will effectively be declaring itself complicit in the ghettoization and slaughter of the Hazara and wider Shia community.

Key Recommendations

The Pakistan government should take immediate measures to investigate and prosecute sectarian killings in Balochistan and conduct a broader investigation into sectarian killings in Pakistan. Specifically, Human Rights Watch recommends:

To the Government of Pakistan

- Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif should follow up on his public denunciations of sectarian killings by ordering the immediate arrest and prosecution of the leadership of the LeJ, its members, and affiliates responsible for planning, ordering, perpetrating, inciting, or enabling sectarian violence.

- Disband, disarm, and hold accountable all militant groups implicated in serious human rights violations, particularly the LeJ.

- Establish an independent federal commission to investigate, recommend criminal prosecutions, and publicly report on sectarian killings in Balochistan. The commission should investigate the failure of successive Pakistani governments at the federal, provincial, and local levels to successfully investigate and prosecute such sectarian killings in Balochistan. The commission should be given unfettered access to relevant government records on sectarian killings, as well as the authority to hold public hearings and subpoena individuals, including survivors of sectarian attacks, relatives of victims, government officials, and security force personnel, to testify.

- Immediately remove from service any administrative or security personnel implicated in sectarian attacks or who failed to investigate and arrest alleged perpetrators of such attacks.

To the Provincial Government of Balochistan

- Disband, disarm, and hold accountable all militant groups, particularly Lej, implicated in serious human rights violations. Seek the assistance of the federal government within the framework of the constitution as required.

- Instruct the police to fully investigate all cases of targeted killings and to prosecute those implicated in such abuses, especially members of the LeJ and affiliated militant groups. Assist federal level investigations within the ambit of the law and constitution.

- In consultation with Hazara and other Shia communities, tighten security measures and the deployment of security forces around Shia mosques and other areas where Shia communities congregate to ensure they can engage in religious, social, cultural, and economic activities without threat of violence.

- Implement and uphold laws prohibiting hate speech that results in incitement or discrimination as defined in international law.

To Major Donors and Pakistan’s External Partners, including the United States, European Union, Japan, Australia, the World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank

- Press the Pakistani government to uphold its international human rights obligations and promote good governance by investigating sectarian killings in Balochistan and prosecuting all those responsible, particularly the LeJ leadership, which has publicly claimed responsibility for hundreds of attacks.

- Press the Pakistani government to disband, disarm, and hold accountable all militant groups implicated in serious human rights violations.

- Offer to support external law enforcement assistance with investigations into sectarian killings in Balochistan and elsewhere in Pakistan.

- Use bilateral meetings, including within the diplomatic, law enforcement, and intelligence realms, to reinforce these messages.

- Communicate to the Pakistani authorities that a failure to take action against militant groups implicated in abuses against minorities in areas under government control jeopardizes US economic, development, and military assistance and cooperation.

Methodology

This report is based on more than 100 interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers in Quetta and by telephone from January 2010 through June 2013. Human Rights Watch interviewed victims of attacks and their relatives, local Hazara community leaders, and members of Balochistan provincial government, police, the Frontier Corps, and retired intelligence personnel.

Due to the ongoing violence against Shia Hazara in Balochistan, our research required a high level of sensitivity to the security of both the researchers and interviewees. We conducted interviews only in circumstances in which they could be carried out without surveillance and possible harassment and reprisals by militants. Where necessary, names of Hazara community members have been changed in this report due to concerns about possible militant reprisals, as indicated in relevant citations. All retired intelligence and FC personnel spoke on condition of anonymity due to professional constraints and obligations.

Interviews were conducted in Urdu and English. Human Rights Watch neither offered nor provided incentives to persons interviewed. All participants provided oral informed consent.

The report also draws on academic research, relevant reports, and articles published in Pakistani and international media.

I. Sectarian Militancy in Pakistan

While Pakistan has not held a census since 1998, its current population is estimated at around 185 million people, of whom approximately 95 percent are Muslim.[1] Sunnis represent approximately 75 percent of the population and Shias 20 percent.[2] The small Hazara Shia community is concentrated in the south-western province of Balochistan, largely in the capital city of Quetta; it is estimated to be around 500,000.[3]

The rise in violence between Sunni and Shia Muslims in Pakistan began in the early 1980s. Prior to this, clashes between Shias and Sunnis were rare and usually occurred during Muharram processions, commemorating the seminal event in Shia history.[4] A combination of domestic and international political factors contributed to this rise in violence, including the Iranian Revolution of 1979, military ruler Gen. Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq’s policy of Islamization[5] of the Pakistani state, and US-backed Afghan resistance to the 1979 Soviet Invasion.[6]

The success of the Iranian Revolution and Zia-ul-Haq’s impostion of his Islamization program (reflecting the rising influence of the Sunni Deobandi school of thought),[7] actively resisted by the Shia community, played a significant role in radicalization of both Sunni and Shia. The new revolutionary government in Iran supported the Pakistani Shia in their effort to counter Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization effort, which itself was directly backed by Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia. The Shia community viewed Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization as a bid to create a Sunni state. In response, Pakistani Shia in 1979 founded the Tehrik-e-Nifaz-e-Fiqh-e-Jafaria (TNFJ) with the declared objective of defending the community, and by 1985 it had become a militant Shia organization.[8]

To contain such perceived challenges to Sunni dominance in Pakistan, Deobandi Sunni organizations such as the Jamiat-e-Ulema-e-Islam (JUI)[9] supported the establishment of the militant Sipah-i-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP)[10] in 1985. The SSP was formed under the leadership of Haq Nawaz Jhangvi, who belonged to a poor family from the central Punjab town of Jhang, and at the time was the naib amir (vice-president) of JUI Punjab.[11] The SSP was a sectarian group focused on limiting the influence of Shi’ism in Pakistan.[12] The SSP was responsible for high-profile assassinations of Iranian diplomats, including that of Iranian Consul-General Agha Sadiq Ganji in 1990.[13]

In 1988, after Zia-ul-Haq’s death, civilian rule and democratic governance returned to Pakistan. At the same time, Shia-Sunni militancy escalated markedly with assassinations of government and military officials by both Shia and Sunni militants as well as the targeted killings of ordinary citizens, mostly Shia, on the basis of sectarian identity. Those killings prompted numerous professionals and business people, particularly members of the Shia community living in the port city of Karachi, to go into self-imposed exile or to relocate to “safer” cities.[14]

The return to democratic rule led the SSP and TJP to enter mainstream politics by forging alliances with the Nawaz Sharif-led Pakistan Muslim League (PML) and Benazir Bhutto’s Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP). However, within a couple of years of their formation, both the SSP and TJP formed splinter groups—the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) and Sipah-e-Muhammed (SM), respectively.

The Taliban, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, and the Hazara

The emergence in Afghanistan in 1994 of the Pakistan-government-backed Taliban, militant Sunni Muslims who view Shia as blasphemers, [15] unleashed a new wave of persecution against the Hazara in Afghanistan. In August 1998, when Taliban forces entered the multi-ethnic northern Afghanistan city of Mazar-i Sharif, they killed at least 2,000 civilians, the majority of them Hazaras. [16] In the immediate aftermath of the city's occupation by the Taliban, the newly installed governor, Mullah Manon Niazi, delivered public speeches in which he termed the Hazaras “infidels” and threatened them with death if they did not convert to Sunni Islam or leave Afghanistan. [17] These events caused many Hazara to flee to neighboring Balochistan and to Iran.

A number of Pakistanis, including members of the extremist Sunni group Sipah-i-Sahaba (SSP) and its off-shoot, the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ), fought on the side of the Taliban in Mazar-e Sharif.[18]The links between these Afghan and Pakistani Sunni militant groups and the flood of Hazara into Balochistan prompted a rise in persecution of the Hazara in that province.

The fall of the Taliban government in late 2001 marked an end to the extreme prejudice and threats that Hazara in Afghanistan had been enduring. However, Taliban attacks targeting Afghanistan’s Hazara have continued under the administration of President Hamid Karzai. In 2004, for instance, Taliban forces pulled 16 Hazaras from their vehicle in south-central Afghanistan and executed them.[19] Many other attacks on the Hazara by the Taliban and their allies in Afghanistan have been documented.

But the Taliban’s loss of power in Afghanistan has made the situation more precarious for the Hazara in Balochistan. Key members of the Taliban’s senior leadership relocated to Balochistan’s capital, Quetta.[20] Their presence, combined with the emergence of LeJ and SSP as Al-Qaeda affiliates in Pakistan, has created new dangers for Balochistan’s Hazara.

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi in Pakistan

The LeJ is reportedly funded by private Arab donors and was created for the sole purpose of serving as an anti-Shia, anti-Iran militant group.[21] The LeJ has reportedly established strong links with Islamist armed groups fighting in Kashmir and Afghanistan.[22] In 1998, as noted above, the LeJ fought alongside the Taliban and participated in the massacre of thousands of Hazaras in Mazar-e-Sharif.[23] There is evidence to suggest that Islamist groups such as the Harkat-ul-Aansar (HuA) have offered protection and training to members of SSP and LeJ.[24]

Like the SSP, the LeJ carried out high-profile assassinations of Iranian diplomats including that of Muhammed Al-Rahimi in Multan in 1997, and an attack on the Iranian Cultural Centre in Lahore the same year.[25] LeJ members have also been implicated in the attempted assassination of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in Raiwind, Lahore, in 1999 and for the Mominpura massacre of 27 Shias in Lahore in 1998.[26]

Military ruler General Musharaf banned the LeJ in 2002,[27] but the ban has not hobbled the LeJ’s ability to perpetrate sectarian attacks across Pakistan. They include attacks against the Hazara community in Quetta carried out in collaboration with the Taliban.[28]

Malik Ishaq

Malik Ishaq has been the operational chief of the LeJ since 2002. Ishaq has been prosecuted for alleged involvement in some 44 incidents of violence that have involved the killings of 70 people, mostly from Pakistan’s Shia community.[29] However, the courts have not convicted Ishaq for any of those killings and have acquitted him in 40 terrorism-related cases, including three acquittals by a Rawalpindi court on May 29, 2014, on the basis that “evidence against Ishaq was not sufficient for further proceedings.”[30] The failure to bring Ishaq to justice underscores both the crisis of Pakistan’s criminal justice system and the impunity for serious abuses this failure facilitates.

In October 1997, Ishaq admitted to an Urdu language newspaper his involvement in the killing of over 100 people.[31] In recent years, Pakistani security forces have linked Ishaq, in collaboration with the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (the Pakistani Taliban, or TTP), to armed attacks, such as those on the Mannawan Police Academy outside Lahore in 2009[32] and on the visiting Sri Lankan cricket team the same year.[33]

Ishaq has maintained a close working relationship with Pakistani military and intelligence authorities. In October 2009, they flew Ishaq from Lahore to Rawalpindi on a military plane to negotiate with Al-Qaeda and TTP militants linked with the LeJ for the release of several high-ranking military officers taken hostage in an attack on the Pakistan army’s General Headquarters.[34] While Ishaq’s intervention at the behest of the Pakistani military was widely reported but never officially acknowledged by authorities, a military official speaking on condition of anonymity confirmed the reported facts to Human Rights Watch.[35]

On July 14, 2011, the Supreme Court of Pakistan ordered Ishaq’s release on charges of murder due to lack of evidence. Upon release, Ishaq was greeted outside prison by SSP chief Maulana Muhammad Ahmad Ludhianvi.[36]

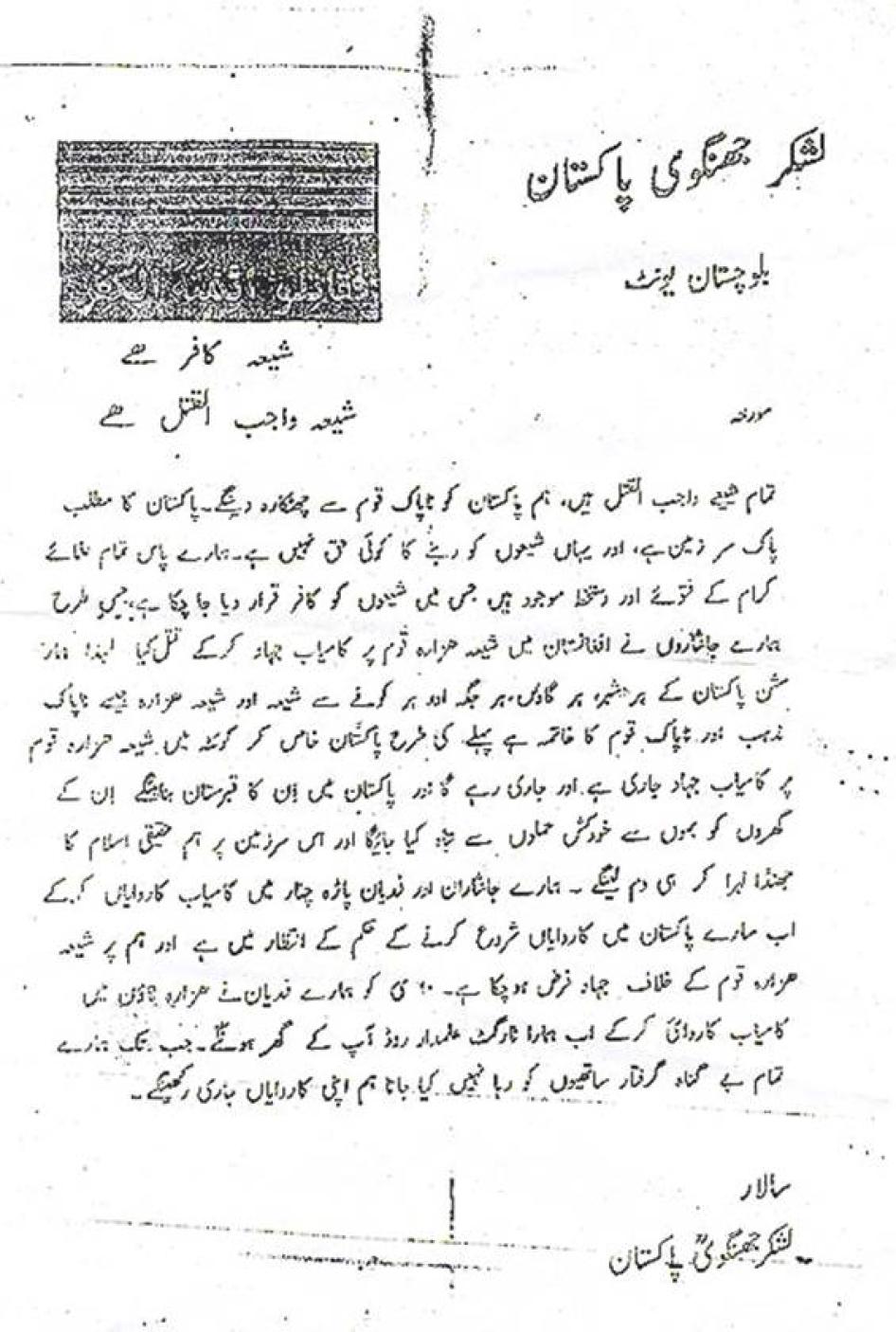

Coinciding with Ishaq’s July 2011 release, the LeJ promptly issued a written threat against the Shia population. The letter, written in Urdu and widely circulated in Quetta and beyond, stated:

All Shi'ites are worthy of killing. We will rid Pakistan of unclean people. Pakistan means land of the pure and the Shi'ites have no right to live in this country. We have the edict and signatures of revered scholars, declaring Shi'ites infidels. Just as our fighters have waged a successful jihad against the Shi'ite Hazaras in Afghanistan, our mission in Pakistan is the abolition of this impure sect and its followers from every city, every village, and every nook and corner of Pakistan. As in the past, our successful jihad against the Hazaras in Pakistan and, in particular, in Quetta, is ongoing and will continue in the future. We will make Pakistan the graveyard of the Shi'ite Hazaras and their houses will be destroyed by bombs and suicide bombers. We will only rest when we will be able to fly the flag of true Islam on this land of the pure. Jihad against the Shi'ite Hazaras has now become our duty. [37]

On August 30, 2011, gunmen riding a motorbike shot dead Zulfiqar Naqvi, a Shia judge in Quetta, his driver, Essa Khan, and a police bodyguard, Abdul Shakoor.[38] Those murders prompted the police to re-arrest Ishaq the following day on charges of inciting violence against the Shia community on August 9, 2011.[39] Pakistani judicial authorities subsequently released Ishaq on bail on September 10, 2011.[40] Then, in the aftermath of the September 20, 2011 Mastung massacre, on September 21, police placed Ishaq under house arrest under Maintenance of Public Order (MPO)[41] provisions.[42]Sohail Chatta, the local police chief, told the media that house arrest had been imposed because Ishaq’s behavior endangered “sectarian harmony and caused a sudden rise in sectarian temperature in the country.”[43] The Lahore High Court ordered Ishaq’s release on January 21, 2012 because of lack of sufficient evidence.[44] Police re-arrested Ishaq under the MPO on February 25, 2013, after two suicide bombings killed about 200 Hazaras in Quetta.[45] While Ishaq remains under formal detention, the police have made no progress in investigating existing charges against him nor have they brought any additional charges against him linked to subsequent LeJ attacks.[46] He is believed to be in control of LeJ operations from prison.[47]

The United States Department of State declared Malik Ishaq a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist” on February 6, 2014. [48]

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi in Balochistan

Usman Saifullah Kurd has been operational chief of the LeJ in Balochistan since at least 2002. Media reports have alleged that he has been involved in hundreds of killings across the country, particularly Balochistan.[49] Pakistani intelligence officials allege that several other key militants including Dawood Badini[50] and Shafiqur Rehman Rind[51] assist Kurd with LeJ operations.[52]

According to a now-retired Pakistani intelligence official, Mohammed A. (a pseudonym), the Pakistani government did not consider LeJ’s presence in Balochistan a “cause for concern” until the first major attack on Hazaras in Balochistan on July 4, 2003, in Quetta. In that attack, three gunmen entered a Hazara mosque (Imambargah) during Friday prayers, killing 53 people and injuring 57 others.[53] Mohammed A. told Human Rights Watch:

Until this attack, we saw the LeJ guys as allies, if not friends. Their activities were manageable. But these attacks on the Hazara did change the perception and then many of us stopped thinking of them as allies. But, importantly, many of us did not.[54]

Ahmad B. (pseudonym), another former intelligence official, provided Human Rights Watch a description of the LeJ’s organizational structure in Balochistan. He said that the four key LeJ members have been involved in fighting NATO forces in Afghanistan. The militants usually operate in small groups of three to four people for a particular mission—although this may change at times. When they are not operating, these militants are usually involved in training and recruitment activities—although this may overlap. The three main centers which are Lashkar-e-Jhangvi hubs in Balochistan are Mastung, Quetta, and Khuzdar. Two other regions that are becoming increasingly radicalized are Turbat and Hub near Karachi. Karachi is seen as a safe haven for the militants—many have second homes there—particularly in the Lyari area.[55]

Despite the LeJ’s long record of atrocities against civilians, Ahmed B. told Human Rights Watch that Pakistani intelligence did not perceive the group as a fundamental threat to the state: “While these people are hostiles and often attack us, it is important to maintain some level of goodwill with them as they can be useful.”[56]

Police arrested Badini on June 14, 2004, in Karachi.[57]While in custody, Badini allegedly confessed to masterminding the bombing of a Shia mosque (Imambargah) in Quetta on July 4, 2003, and the bombing of a Moharram religious procession in Quetta on March 2, 2004.[58]

Police arrested Saifullah Kurd, LeJ’s Balochistan leader, in Karachi on June 22, 2006.[59] While in custody, Kurd allegedly admitted to having trained a cadre of hit men and suicide bombers to target the Shia in Quetta and masterminding multiple attacks on Shia, mostly Hazara targets.[60]

Kurd and Bandini escaped from an Anti-Terrorism Force jail in Quetta’s highly guarded Army Cantonment on January 18, 2008, under circumstances that Pakistan’s military has been unable to explain.[61] Badini was later re-arrested but Kurd remains at large.[62]

A retired Frontier Corps official told Human Rights Watch:

When Kurd was arrested, he admitted to everything he had done and boasted he would be free and the authorities could not hold him. It turns out he was right. And he could not have escaped from the Quetta Cantonment without inside involvement. If there was any doubt about inside involvement it ended that day. [63]

II. Attacks on Hazara and Other Shia in Balochistan

The following are illustrative cases of sectarian attacks against Hazara and other Shia in Balochistan since major attacks began in 2003. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list and omission of specific cases is in no way a reflection that Human Rights Watch does not consider each case to be a tragedy in itself.

Hazara Mosque Attack, July 2003

The first major attack on Hazaras in Balochistan took place on July 4, 2003, in Quetta when three Sunni gunmen entered a Hazara mosque during Friday prayers and killed 53 people and wounded 57 others.[64] Authorities later reported that one of the attackers was confirmed to be a suicide bomber.[65] The LeJ claimed responsibility for the attack.[66] Family members of victims report ongoing threats and follow-up attacks by what they suspect were LeJ militants.

Fatima, widow of Kashif Raza, a shopkeeper killed in the attack, is one of several family members of victims of the Hazara mosque attack who told Human Rights Watch that suspected LeJ militants continue to attack them and threaten their safety:

Our family is still receiving threats from the LeJ, but we have not lodged a complaint with the local authorities because they will do nothing. My brother along with his five friends was also attacked on May 30, 2008. The young men, all between 17 and 21 years of age, were returning home after a cricket match. Gunmen on motorbikes surrounded and opened fire on them in the early evening on Samungli Road in Quetta. My brother was injured, but survived, while his friends lost their lives. My family has not filed any complaints because they have no strong backing to be taken seriously by the authorities. Police and security agencies have not caught the killers. Members of our community are not given basic human rights in Quetta and they do not feel secure living there.[67]

Targeted Killing of Dr. Abid Iqbal, August 2009

By 2009, the focus of LeJ attacks on the Hazara in Balochistan shifted from Shia religious processions to the targeting of individual Shia professionals and government and security force officials.

On August 17, 2009, Dr. Adib Iqbal, an eminent cardiologist at Quetta’s Civil Hospital, became one of the first victims of LeJ attacks on prominent Shia in Quetta.

Tahira Iqbal, Iqbal’s widow, told Human Rights Watch that her husband was killed after receiving multiple death threats from an unidentified source who Dr. Iqbal believed was a LeJ insurgent. She attributed the LeJ’s targeting of her husband due to “his stature in the [Hazara] community.”[68] She said:

The day my husband was shot dead, he left early for his clinic. It was around 5 p.m. on Monday, August 17, 2009. I was sitting in our drawing room when he appeared dressed and ready to go. I was a bit surprised—it was bit early for him to leave. He glanced at me briefly and then he left. That was the last time I saw my husband. An hour later, a relative called to say he had been shot—he had heard it on TV. We immediately switched to a news channel. Sure enough, there was the news—I immediately took my then 10-year-old son and rushed to the Civil Hospital where the media said he had been taken. By the time we got there, it was too late.

We later learned how he was killed from the people present in the building where my husband’s clinic was located.[69] My husband had just arrived there and was parking his car. At that moment he was attacked from the front—as he was leaning across the seat of the car. He died on the spot while his killer calmly walked away from the parking lot. Some eyewitnesses say [the killer] then got on a motorbike and drove away from the scene. But everybody knows who it was—the description by the eyewitnesses and the messages recovered from my husband’s phone all pointed to Saifullah Kurd.[70] However—for reasons best known to them—the police insisted on registering a report against unknown assailants. I did not push the matter at the time. I was too much in shock and had other problems.

Tahira Iqbal said that her husband’s death followed multiple death threats from an individual who identified himself as Saifullah Kurd:

I knew he had been receiving threats about two years earlier but I thought they had stopped. In fact they had continued and intensified since June 2009. His friend later told me they were all by Baloch speaking men. They were in the form of calls and text messages. Most were from Saifullah Kurd—he actually identified himself or wrote that it was him. In the last message he said clearly ‘We will not let you live.’[71]

Tahira Iqbal described to Human Rights Watch how she continued to receive threats after her husband’s murder:

After his death, I used his cell for a while and I started getting calls. They were all taunting and sometimes even vulgar and obscene. The first one came the night that Abid died—the man asked ‘How do you feel now?’ After a while I just shut the [phone card] off.[72]

2010: Escalating Violence

Sunni extremist killings of Shia Hazara escalated in 2010. That year, at least 80 Shia, most of them Hazara, were killed in Balochistan.[73]

Attacks included the gunning down of groups of civilians, suicide bombings, and targeted killings of individual Shia. Virtually all segments of the Hazara community came under attack.

Targeted Killing of Dr. Nadir Khan, January 2010

On January 12, 2010, LeJ gunmen shot and killed Dr. Nadir Khan and his driver, Shabbir Husain, in Quetta.[74] Husain’s brother, Mubahir Husain, told Human Rights Watch:

Dr. Khan had received many threats prior to the attack by the LeJ and had lodged a complaint with the police authorities. The government has, of course, failed to arrest the killers.” As Shias, my family and I receive threats all the time and have complained to the authorities several times but no action has ever been taken. The members of our community feel vulnerable and insecure and live in a constant state of anxiety in Quetta. We feel we are not given any rights. We feel we are the walking dead. [75]

Suicide Bombing of Hospital, Quetta, April 2010

On April 16, 2010, a suicide bomber killed 12 people and injured 47, including a journalist and two police officials, in an attack on Quetta’s Civil Hospital.[76] The attack took place after the body of Ashraf Zaidi, a Shia bank manager, shot dead earlier in the day by Sunni extremists, was brought to the hospital. The attackers evidently targeted the hospital knowing that members of the Shia community would be gathering at the hospital in the aftermath of Zaidi’s killing. LeJ claimed responsibility for the attack.[77]

The bombing killed Syed Ayub Shah, a Hazara community leader. His brother Syed Asghar Shah told Human Rights Watch:

My brother was killed in a suicide bomb attack on a group of mourners outside the emergency section of Quetta’s civil hospital on April 16, 2010. Several members of the Hazara community as well as senior police officials were killed in the attack. My brother had gone to attend to the body of our cousin Syed Arshad Zaidi—son of Syed Ashraf Zaidi chairman of the Shia council of Balochistan. He had been shot dead by gunmen earlier that morning. As our uncle, Syed Ashraf Zaidi, was out of town, my brother rushed to the hospital as soon as he heard the news. It was the Civil Hospital, the main trauma center in the city. I dropped him off near the hospital before going on to collect my nephew. I had just returned to the hospital when the blast took place. I had just disembarked from the car when the blast occurred. As I tumbled over, my nephew, who is a policeman in the anti-terrorist wing, picked me up and pushed me against the wall of the hospital compound. After the blast we continued to wait outside as there was intermittent gunfire, finally, after 10 minutes, we were able to get in. I kept calling on my brother’s cell phone, but got no answer. Eventually my youngest brother picked us up. I asked him if Ayub was well. He just told me to come into the main section of the emergency. When I walked in I saw Ayub in my youngest brother’s arms. He had bled to death.[78]

Targeted Killing of Dr. Qamber Hussain, May 2010

Unidentified gunmen shot and killed Dr. Qamber Hussain, a Hazara physician, at Quetta’s Civil Hospital on May 22, 2010. The gunmen also shot and killed Ali Murtaza, a bystander who attempted to assist Hussain after he was shot.[79] According to Murtaza’s father:

My son Ali Murtaza was going about his business on Sarki Road in Quetta when terrorists attacked Dr. Qamber Hussain, a physician at the civil hospital. The incident took place right in front of him. Dr. Hussain was bleeding to death when my son tried to get him out of his car. The terrorists, who were still there, then opened fire on my son as a result of which he was seriously injured. By the time the ambulance got there, Dr. Hussain was dead, but my son was still alive. He died later in hospital. They had shot him four times. He had a head wound that proved to be fatal. My son himself had received threats from the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi earlier, but that never scared him. He was a spiritual healer by profession, a peaceful man. The Lashkar-e-Jhangvi has been named as being behind the attack. But no arrest has taken place so far. As a Shia, I expect no protection from the Pakistan state. It seems the Pakistani state wants to see all Shias dead.[80]

Suicide Bombing on Al Quds Rally, September 2010

A suicide bombing on September 3, 2010, killed 56 Shia demonstrators and wounded at least 160 others who were attending a rally near Quetta’s Meezan Chowk traffic circle.[81] The demonstration was organized by the Imamia Students Organisation, a Shia student group. Immediately after the suicide attack, unidentified gunmen started firing into the air creating further panic.[82] Lashkar-e-Jhangvi claimed responsibility for the attack and confirmed the identity of the bomber as 22-year-old Arshad Muavia.[83]

Immediately after the attack, the Inspector General of Police for Balochistan, Iqbal Malik, suggested that the attack had taken place because the protesters had reneged on an agreement to not go up to Meezan Chowk. “They were stopped at a place agreed upon for terminating the procession, but they violated the written agreement,” Malik told the media.[84]

2011: Worsening Brutality

In 2011, LeJ attacks on Shias across Balochistan rose in frequency and brutality.

Spini Road Attack, July 2011

Alleged LeJ gunmen shot and killed 11 Shia Hazara and wounded 3 others on July 30, 2011, on Spini Road in Quetta. The motorbike-riding gunmen fired at a passenger van travelling to Quetta from Hazara town.[85]

Buniyad Ali, whose wife Paril Gul was killed in the attack, told Human Rights Watch:

My wife and son were on their way home when the public service van they were travelling in was attacked in Quetta. Gunmen opened fire in broad daylight on the van. Paril Gul was a housewife and would rarely venture out. She had gone to visit her ailing father taking my son along. The police later registered a complaint against the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi but nothing has been done. Why did the Lashkar kill my wife and why has the government not done anything to stop them? Our life is a living hell. I am forced to believe that the government wants all Shias dead. There is no other explanation.[86]

Fatima, the widow of Syed Aqeel Mosavi, another victim of the Spini road attack, told Human Rights Watch:

My husband was a day laborer. He was travelling in a passenger van on his way to the market for work when it was attacked by Lashkar-e-Jhangvi terrorists. Aqeel was a good man and not involved in politics—they just target us because we are Shias. The government attitude is unbelievable: so many security agencies and they can’t provide us protection even in Quetta?[87]

Eid Day Suicide Bombing, August 2011

On August 31, 2011, an alleged LeJ suicide bomber attacked a Shia mosque on Gulistan Road in Quetta’s Murriabad area. The attack killed 11 Shias and wounded 13 others.[88] The bomb detonated as worshippers emerged from the mosque after marking the Muslim festival of Eid.[89] The blast was severe enough to destroy several neighborhood houses.[90]

Idrees, a resident of one of the houses damaged by the blast, described the post-blast carnage to Human Rights Watch:

I was inside my home when the walls shook, there was a loud noise and everything fell down. I rushed out and saw black smoke at the street corner. There were bodies lying everywhere, limbs, torsos, other body parts. The living were covered in blood. People were screaming in panic or agony. From one minute to the next, a peaceful place had turned into a vision of hell. I rushed in to help. I asked how it had happened—one of the injured told me a Toyota pickup van came speeding down the main road and tried to force its way down the [narrow] street leading to the entrance of the Imambargah [mosque]. Then it blew up. [91]

Ali Dost, the father of 10-year-old Sher Ali who was killed in the blast, told Human Rights Watch:

I heard the blast and rushed to help. I wasn’t worried about Sher Ali—I thought he was at home or my sister’s. There were dozens injured and everybody pitched in to help. As the ambulances started taking them to hospital, we heard blood was needed. So my eldest son and I rushed off to Civil Hospital to donate. We saw lots of dead and injured, but not my son.

After that we came back around mid-day. I went to say my prayers and sent my son to look for the other children. At that time, there was an announcement from the mosque. They said the bodies of a 65-year-old man and a 10-year-old boy were lying there. I went there to see who it was and my son was lying there dead. He had been hit by pellets in the neck, in his eyes, on the head as well as the hands and lower abdomen. One of his legs was broken, but there was no mistaking he was my Sher Ali.

He was bright and cheerful young boy—10 years of age. He was my favorite. I had brought him up myself since the death of his mother. He was studying in Grade 4 at the Fauji Foundation School and was also learning the Quran at the mosque. Everybody who knew him loved him. Why did the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi have to kill him? What have we done? Why did the government allow my son to die? And tomorrow, so will I die. So will we all. Every last Shia will die if the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi can help it. And our government will just watch us being slaughtered.[92]

Syed Ali Naqi, the father of 22-year-old victim Syed Mohammad Yusuf told Human Rights Watch:

As soon as the [Eid] prayers ended, Yusuf went out of the mosque to greet some friends—I stayed behind to exchange good wishes with neighbors. I saw him leave. Then the blast took place. I heard an enormous sound and a cloud of smoke. There was chaos immediately afterwards, but a few minutes later there was an announcement from the mosque asking people to get inside as it was safe. The doors were then shut for about 10 minutes. Afterwards, when things had calmed down, the gates opened. I rushed outside and started looking for Yusuf—there was just this gut feeling that something had happened to him. We didn’t find him in the melee outside. Some of the dead and injured had already been rushed to hospital so we went to the Civil Hospital. I walked into the emergency and there was a line of bodies with shrouds covering their faces.

I lifted the cover off the first and it was my son. His body was totally burnt—there was a cavity where his heart had been and his entire body was marked with pellets. I recognized him by his hands—his clothes had turned to ashes. I asked God to receive his sacrifice and took the body home.

Yusuf was a handsome young boy. He was 22 years old and studying business at a local college. My family have been living here forever and never received any threats. But the government is increasingly failing in its duty to protect us. There is only the law of the jungle or worse if you are Shia. I have a good business, I pay taxes but I still feel I am a second-class citizen in Pakistan. Why are Shias to be killed? Why does the government allow Lashkar-e-Jhangvi to kill us?[93]

Mastung Massacre, September 2011

On September 19, 2011, near the town of Mastung, Sunni gunmen forced about 40 Hazara to disembark from a bus in which they had been traveling to Iran to visit Shia holy sites. The gunmen then shot dead 26 of the Shia passengers and wounded six others.[94] Although some of the Hazara passengers managed to escape, another three were killed by gunmen as they tried to bring victims of the bus shooting to a hospital in Quetta.[95] LeJ claimed responsibility for the attack.[96] While previous large scale attacks on Hazara involved suicide bombings, the Mastung attack was the first mass killing in which the assassins first identified and separated the Sunni and Shia passengers, and then proceeded to kill the Shia.

Haji Khushal Khan, the driver of the bus, told Human Rights Watch that gunmen in three Toyota Hi-Lux Minivans forced the bus to the side of the road and then methodically began murdering his Shia passengers:

I drive coaches on the route to the Iran border. That day we had left on time from the bus depot and entered Mastung. [The gunmen] came speeding just as we entered Mastung district and intercepted us. One vehicle passed us and set up a roadblock while another forced us off the road. I don't remember how many men there were, but they were all armed with Kalashnikovs [military assault rifles] and rocket launchers. They told us to get out. They asked who the Sunnis were, asking for names. Then they told the Sunnis to run. We jumped and ran for our lives. Everybody was so scared… someone ran in this direction and someone in that direction. But while they allowed everybody who was not a Shia to get away, they made sure that the Shias stayed on the bus. Afterwards they made them get out and opened fire. I saw it while taking shelter in a nearby building. The bodies then just lay there for one and a half hours before help arrived. The first was a patrol that just set up a perimeter watch. A few minutes later the ambulances arrived to take away those killed.[97]

Victims’ families told Human Rights Watch that the government had failed to provide protection to the Hazaras or to hold perpetrators accountable.

The government responded to the Mastung massacre by placing Malik Ishaq, the LeJ leader, under house arrest under Maintenance of Public Order (MPO) provisions on September 21, 2011.[98]Sohail Chatta, the police chief in Rahim Yar Khan district, told the media that the government had taken that measure because Ishaq’s behavior endangered “sectarian harmony and caused a sudden rise in sectarian temperature in the country.”[99]

Akhtarabad Massacre, October 2011

On October 4, 2011, gunmen on motorbikes stopped a bus carrying mostly Shia Hazara en route to work at a vegetable market in Akhtarabad, on the outskirts of Quetta. The attackers forced the passengers off the bus, made them stand in a row, and opened fire, killing 13 and wounding 6 others.[100]

Faiyaz Hussain, son of victim Hussain Ali, told Human Rights Watch:

My father, Hussain Ali, was shot dead by terrorists in Akhtarabad on October 4, 2011. He was a vegetable vendor by profession and the sole earner in the family. He had collected his vegetables and was on his way to market early in the morning by public transport. The van was then pulled over, all people were made to get out and then were shot dead. There is no other source of income for our family after Hussain’s death. He did not receive any death threats, but our family believes the LeJ is behind his killing. The terrorists behind his death are still at large with no action having been taken against them. I believe my father was martyred because he was a Shia.[101]

2012: Rising Body Count

In 2012 there was a significant spike in the number of killings of members of the Shia community across Pakistan and of the Hazara community in particular in Balochistan. Well over 50 attacks against members of the Shia community took place that year. At least 125 Shias were killed in Balochistan during this period, over 120 of them Hazara.[102]

Attack on Hazara Shops, Prince Road, Quetta, April 2012

On April 9, 2012, motorcycle-riding gunmen attacked Hazara-owned businesses on Prince Road in Quetta. The attack killed six Hazara shopkeepers. The Lashkar-e-Jhangvi claimed responsibility for the attack.[103]

Ramzan Ali, a shopkeeper whose brother Nadir Ali was killed in the attack, told Human Rights Watch that the Shia gunmen had specifically singled out Hazara businesses:

We had a shop on Prince Road, Quetta. My father, myself, and my brother Nadir Ali worked there together. My brother was older than me and was married with four children, two of whom have disabilities.

The attack on our shop took place in the evening around the time of Maghreb prayers [sunset]. I had left the shop 10 minutes prior to the attack. There were four shops owned and run by Hazara Shias in one row and all four were attacked together. Six to seven people on motorbikes came and opened fire. They killed the Hazaras who were working in the shops and also those who were working at the back in the storeroom. I rushed back to Prince Road as soon as I learnt about the attack. By the time I got there, the police and Frontier Corps had arrived and all the bodies of the victims had been removed to Civil Hospital. I locked the shops and then went to Civil Hospital where I identified my brother’s body. In all, six persons were killed and two were injured. One of the injured is still unable to walk.

I know that we were targeted because I later learned that, two days before the attack, someone came to a Pashtun shopkeeper whose shop was four shops down from the Hazara-owned shops and asked which ones were owned by Hazaras. The attackers knew exactly how many Hazaras worked in those shops and where. They knew that there were people working in the storerooms as well, which is why they went to the back of the shops and killed people.

The officer in charge of City Police Station contacted us and also came to the shops to gather evidence for further investigation. However, we have not heard anything after that. We have also not heard about compensation. We have decided not to pursue the matter, as it will be a waste of our time.[104]

Attack on Taxi, Brewery Road, Quetta, April 2012

On April 14, 2012, LeJ gunmen killed six Hazara in an attack on a taxi on Brewery Road in Quetta.[105]

Najeebullah, the 18-year-old son of Mohammed Ali Ariz, a medical doctor who was killed in the attack along with five others, told Human Rights Watch:

On the morning of April 14, my father left home to go to Marriabad to console the family of someone who had died. He was traveling in a taxi with four other persons from the neighborhood. As the taxi came on to Brewery Road, near the Brewery Road police station, four persons on motorcycles opened fire on the taxi. The driver and the five passengers were killed. The Lashkar-e-Jhangvi claimed responsibility for the attack.

Some people who knew us and had witnessed the killing called us to give us this hideous news. As I was the only male family member present at home at the time, I went to the Brewery Road police station to register the FIR [First Information Report].[106] The police have not contacted me since then regarding the investigation nor have we contacted them ourselves since it is very unsafe for us to leave this area.[107]

Raheela Ariz, Mohammed Ali Ariz’s daughter, said her father’s murder followed numerous threats from Sunni extremists:

A few days before his death, my father warned my brothers and several of his friends and acquaintances about their safety; he asked everyone to take extra security precautions. This was because he had received threats from the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi.[108]

Quetta Passport Office Killings, May 2012

On May 15, 2012, alleged LeJ gunmen on motorcycles opened fire on a crowd of Hazaras outside the Quetta Passport office on Joint Road. The attack killed two Hazaras and wounded another.[109]

Zahoor Shah, father of Sajjad Hussain, who was killed in the attack, told Human Rights Watch that his son was at the passport office to work abroad:

My son’s passport was about to expire and he wanted to have it renewed so he could try to seek employment in Iran as conditions in Quetta have been steadily deteriorating—which is why he felt the need to go to Iran. He first went to the office on [May] 14 but could not be attended to since there was already a long queue when he arrived. So the following day, he went rather early in the morning. A few hours later, a person whom we know who works in the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) called me to inform me that my son had been killed. His friend Mohammed Tahir, who had accompanied him, was also killed.

The police have not contacted us about the investigation. We did put in an application for compensation, but have still not heard anything about it from the authorities.

The Lashkar-e-Jhangvi claimed responsibility for the attack. I don’t understand why my son has been killed—my reality simply is that my son is dead.[110]

University Bus Suicide Bombing, June 2012

On June 18, 2012, a suicide car bomb attack on a university bus In Jinnah Town, Quetta, killed four Shia Hazara and wounded 72 others, including 28 students. Lashkar-e-Jhangvi claimed responsibility for the attack.[111]

Ali Akhlaqi, the 16-year-old brother of victim Aqeel Raza, told Human Rights Watch of how he learned of his brother’s murder:

I was in school when my brother was killed. I even remember the moment it happened. We had congregated for assembly and at 8:20 a.m. we heard a loud blast. There was absolute commotion. At first everyone thought that the girls’ school in the lane next to ours had been attacked. However, a few minutes later some friends came and told us that the IT University bus carrying students from Alamdar Road [Hazara enclave] had been attacked. I started crying because I knew my brother was on that bus and I was worried that he might have been killed. I tried calling his mobile but received no answer. I then rushed home. As soon as I arrived I saw that several women had congregated in our home and my mother was sitting among them in a state of shock. I knew then that my brother had been martyred. A professor and two other students were also killed in the attack. Several others were seriously injured. The Lashkar-e-Jhangvi said they did it.

No one from the government or the police or the FC [Frontier Corps] has contacted us. I am very angry and upset. I want to know why the government is not taking any action against these killers? Why doesn’t the government act when Shias are killed?[112]

Twin Attacks on September 1, 2012

On September 1, 2012, LeJ militants shot dead seven Hazaras in two separate incidents in Quetta. In the first incident, four gunmen riding two motorbikes intercepted a bus near the Hazar Ganji area. The gunmen pulled five Shia vegetable sellers off the vehicle and shot them dead, witnesses told Human Rights Watch. In the second incident, also in the Hazar Ganji area of Quetta, two gunmen on motorcycles shot dead another two Hazaras.[113]

Mastung Pilgrim Bus Bombing, September 2012

On September 20, 2012, the LeJ launched a bomb attack against a bus full of Shia Hazara pilgrims en route to Iran in the Ganjdori area of Mastung outside of Quetta.[114] The attack killed three people and wounded 12 others.[115]

Targeted Shooting in Kuchlak, October 2012

On October 4, 2012, gunmen affiliated with the LeJ attacked a taxi carrying three Hazara provincial government employees from Kuchlak, a town on the outskirts of Quetta. The gunmen killed Sikandar Ali, an employee of the Balochistan government’s finance ministry.[116]

Mohammed Mehdi, a cousin of Sikandar Ali, told Human Rights Watch:

My cousin, Sikander Ali, was employed by the provincial government and was posted to Kuchlak and used to travel from Quetta to Kuchlak and back every day. I suppose he felt safe traveling in this area as it is in the Pashtun belt. On the morning of October 4 between 9 and 9:30 a.m., he left for Kuchlak with two of his friends. As they got to Kuchlak, a young man fired at the vehicle my cousin was travelling in. My cousin’s friends fired in response and the attacker fled. One of the friends, Mohammad Mushtaq, who was injured, then realized that my cousin had been shot in the head. He drove the car to Civil Hospital Quetta but my cousin was pronounced dead upon arrival. He had probably died the instant he was shot. The third person in the car was also seriously injured; while he survived the attack, he was blinded. Lashkar-e-Jhangvi claimed [responsibility for] the attack. The following day… a postmortem report was also provided to the family by Civil Hospital. The police also came to his house to collect further information and assured the family that they would help in getting compensation, but nothing has happened since.[117]

Targeted Attack on Auto Repair Shop, Sirki Road, Quetta, October 2012

On October 16, 2012, four LeJ gunmen on motorcycles shot four men dead from the Hazara community. The attack targeted an auto repair shop owned and operated by a Hazara mechanic in Quetta’s Kabarhi Market on Sirki Road and killed Ata Ali, Muhammad Ibrahim, Ghulam Ali, and Syed Awiz.[118]

Jam Ali, son of Muhammad Ibrahim, described his father’s killing to Human Rights Watch:

My father had rented a tire shop on Sirki Road. It was one in a row of 10-15 shops run by Hazaras. At around 10 a.m., I received a telephone call from my cousin telling me that there had been an attack on the tire shops. Four attackers came on motorcycles that they parked at a short distance from the shops; then they walked up to the shops and opened fire simultaneously on several shops. At the time four people, including my father, were in the shops and all four were killed. All of them received bullets to their heads and necks. Several more would have been killed, but thankfully for them they were not in their shops at the time and were instead sitting at a nearby tea shop.

Upon receiving the news, I rushed to Civil Hospital. A FIR was registered by the police and a post mortem performed the same day and we were provided a copy. However, after that day the police never contacted us regarding the investigation. We, on the other hand, did try to pursue the case and an acquaintance in the police took us to the Capital City Police Office in Quetta. However, when we got there a senior officer asked our acquaintance why he had brought us to the office. He said: ‘Why have you brought these people here? They know and we know who killed their father. Take them away!’ No government official contacted us about compensation.[119]

Spinney Road, Quetta Taxi attacks, November 2012

On November 6, 2012, LeJ gunmen opened fire on a taxicab travelling to Hazara Town in Quetta killing three Hazara, including the taxi driver, Mohammad Zaman.[120]

Sughra, the widow of Zaman, described to Human Rights Watch the killing of her husband:

He left that morning to earn his livelihood. There were five persons in the taxi and as the taxi got on to Spinney Road, gunmen opened fire. Three people were killed and two were injured. One of the injured died later. I am told that the newspaper said that the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi claimed responsibility for the attack.

My husband was taken to Bolan Hospital and was pronounced dead upon arrival. My brother went to the hospital to identify the body. No government official has come forward to assist us.[121]

In a separate attack on a taxi the same day, November 6, 2012, LeJ gunmen shot and killed Rehmat Ali, a taxi driver, on Spinney Road in Quetta.[122]

Mohammed Ibrahim, the father of Rehmat Ali, told Human Rights Watch that the police had not notified him about progress in the investigation nor had he heard of any possible government compensation for his son’s murder.[123]

Targeted Killings in Qandahari Bazaar, Quetta, November 2012

On November 10, 2012, LeJ gunmen attacked a taxi cab driving through the Qandahari bazaar area of Quetta. The attack killed two of the taxi’s Hazara passengers and wounded the driver.[124]

Mirza Ali, the taxi driver, described the attack to Human Rights Watch:

At first, I didn’t realize who was being targeted. But a moment later, I realized that our vehicle had been targeted and I ducked. However, I still received five bullets. The person sitting next to me was shot in the head and died immediately. He slumped and fell on my arm and I was also hit in the arm as a result of which it broke. In addition, a bullet grazed my neck and I was hit in the leg. Both persons sitting in the back were also shot in the head; one died in the car while the other was seriously injured. Despite my injuries and with great difficulty, as soon as the firing stopped, I sped my taxi away to Civil Hospital. Two people were pronounced dead upon arrival while myself and the other passenger at the back were injured. From Civil Hospital, we were later shifted to Quetta’s Combined Military Hospital.

In Civil Hospital someone took down my statement. However, I am not sure if it was a police official. No police official contacted me after the incident for my statement or for any assistance in a criminal investigation. I have also not been contacted by a government official regarding compensation. I paid for some of my medical expenses and I am told that the government took care of the rest. However, I am not sure if they have paid or if they will pay for any medical expenses in the future.[125]

Targeted Killings in Qandahari Bazar, Quetta, December 2012

On December 13, 2012, LeJ gunmen shot and killed three members of Quetta’s Hazara community in three separate targeted killings.[126] One of the victims was Karar Hussain, a baker, who was shot dead at the bakery where he worked in Qandahari Bazaar.[127]

2013-14: Unprecedented Massacres

The bloodiest attacks, resulting in the highest death tolls recorded in sectarian violence in Pakistan since independence in 1947, occurred in January and February 2013, when bomb attacks in Quetta killed at least 180 Hazaras. The LeJ claimed responsibility for both attacks.[128]

These attacks were met by countrywide protests in support of the Hazara and the Shia more generally.

Alamdar Road Snooker Club Suicide Bombing, January 2013

On January 10, 2013, a LeJ suicide bombing attack against a snooker club killed 96 Hazaras and wounded at least 150 others.[129] The initial attack killed dozens. Ten minutes after the first blast, as people went to the aid of the wounded, a car bomb planted in an ambulance that arrived on the scene with other ambulances and rescue vehicles exploded near the club, killing dozens more.[130]

Mumtaz Batool, the sister of 22-year-old Mohammad Mehdi who was killed in the attack, described the bombing:

I live at Rehmatullah Road close by to the scene of the attack. I first heard what seemed like a relatively small bomb going off. My brother rushed out to see what had happened, thinking that it was perhaps a rocket attack. That was the last time I saw him. In the second follow-up blast, our entire home shook, all the glass was shattered. My brother’s friends told me that they were moving the injured out of the snooker club when one of the ambulances waiting outside blew up. My brother was killed instantly.

Our entire neighborhood is full of homes grieving the dead and tending to the maimed. There were bits of human flesh on our rooftops and our courtyards. It was horrific.[131]

Talib Hussain, 35, a bystander, told Human Rights Watch of the impact of the blast:

I was passing by the snooker club as I live close by. When I heard the blast, I ran to the club to help. As I moved away from the club for a few minutes about six ambulances entered. And then there was a flash of light. Hundreds of boys had gathered, and the next thing I saw was body parts all over. Initially they had arrested three or four people but we never knew what happened to them and they were never presented in court.[132]

Quetta Hazara Town Vegetable Market Bomb Attack, February 2013

On February 17, 2013, a bomb targeting the crowded vegetable market in Quetta’s Hazara Town killed at least 84 Hazara and wounded more than 160 others.[133] The LeJ claimed responsibility for detonating a remote-controlled water tanker mounted on a tractor-trolley that they had rigged with hundreds of kilograms of explosives.[134]

Mastung Pilgrim Bus Bombing, January 2014

On January 2, 2014, some 30 Hazara were killed in a suicide bombing attack in Mastung on a bus carrying pilgrims back from Iran. 21 Hazara pilgrims were injured. The attacker struck the bus en route from the border town of Taftan to Quetta. The LeJ claimed responsibility for the attack.[135]

The government responded by temporarily suspending the bus service to prevent further attacks.[136]

Taftan Attack, June 2014

On June 9, 2014, 30 Shia pilgrims from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province were killed in a gun and suicide attack on a transit hotel in the Balochistan border town of Taftan. Though a group of non-Hazara Shias were killed before the attackers were killed in retaliatory fire, there were some 300 pilgrims present at the hotel at the time, most of them Hazara.[137] Jaishul Islam, a group affiliated with the LeJ, claimed responsibility for the attack.[138]

Pakistan’s interior minister, Chaudhry Nisar, failed to offer any reassurance or concrete measures to protect Shia pilgrims. Instead, he responded to the atrocity in parliament by suggesting that the mostly desperately poor Shia pilgrims should find alternative modes of travel—by air or ferry——as it was impossible to secure the 700 kilometer bus route.[139]

III. Impact of Violence on Quetta’s Hazara Community

The LeJ’s numerous attacks on Quetta’s Shia Hazara has had a profound impact on the social, cultural, and economic life of that community. Since 2012, Quetta’s Hazara have been compelled to limit their activities to the Hazara-dominated neighborhoods of Marriabad and Hazara Town. As a result, they face increasing economic hardship, little safe access to education, and severe limits on their freedom of movement.

Ramzan Ali, a shopkeeper whose brother Nadir Ali was killed in the April 9, 2012 attack on Shia shopkeepers on Quetta’s Prince Road, believes that the attack was meant not only to kill Hazara, but to worsen their already precarious economic situation. He described how Hazara-owned businesses were being forced to move from other parts of the city into Hazara-dominated neighborhoods for their safety:

After the attack my father kept the shop closed for one month. He then told me to move the shop to Alamdar Road, in our own area [Marriabad], which is where it is currently. It is very unsafe for us to move out of our area now. If we do so it is at great risk to our lives. In the past many of us who had to go out of Quetta for business used to travel by bus. However, now we avoid buses, as it is very risky. We have been forced to travel by air, which is very expensive. Due to these reasons we have suffered tremendously economically.[140]

That view was echoed by Najeebullah, the 18-year-old son of Mohammed Ali Ariz, a medical doctor who was killed in the April 14, 2012 Brewery Road attack:

It is virtually impossible for us to go out of Hazara Town and if we do so, it is at great cost to our lives. My father, like other members of our community, received threatening phone calls from the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi who want our community to leave Pakistan.

Zahoor Shah, father of Sajjad Hussain who was killed in the May 15, 2012 Quetta Passport Office attack, said:

There is no other earning member in our family. My younger son is training to be a tailor but until he learns the trade, he is unable to support the family. My son Sajjad was the sole breadwinner. Some people knew our situation and they tried to help us, so we began to survive on handouts from our neighbors. However, how long can people keep supporting us? Some have stopped giving.[141]

Ahmad Hussain, the older brother of Aqeel Raza killed in the June 18, 2012 university bus suicide bombing, described the impact of LeJ violence on the Hazara community as being akin to a hostage-taking:

We have also suffered economically as we can only work safely in our own areas. I used to be posted in the EFU[142] office on Jinnah Road but a year ago my boss, fearing for my safety, kindly relocated me to the office on Alamdar Road. We are now hostages in our own city.[143]

Juma Khan, the son of Hussain Ali who died in the June 28, 2011 Hazarganji bus bombing, described how the attacks have restricted employment options for himself and other members of the Hazara community:

I used to drive a rickshaw, but currently I am unemployed. In the current situation it is very difficult for me to drive a rickshaw as it is very unsafe for Hazaras to travel to and work outside our own area. I am looking for government job or some work in Marriabad [where we live]. My family and I received no threats before or after the bomb attack. However, we only feel safe and secure in our own area and not in others. The government has failed to protect our community. They know that the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi are the killers, but still they do not stop them. It seems the law enforcers are on the side of the killers not ours. [144]