Locked Up in Karaj

Spotlight on Political Prisoners in One Iranian City

Map

Summary

While United Nations bodies and human rights groups have frequently reported that Iran’s prisons contain large numbers of political prisoners, there is little clarity on the precise number of persons the authorities in Iran are currently detaining solely because they exercised their fundamental rights such as freedom of speech, assembly or association. This report is the beginning of an effort by Human Rights Watch to address this lack of clarity and specificity by compiling a roster of political prisoners in Iran and recounting some of their stories. The report focuses on several prisons in the city of Karaj which lies about 47 kilometers northwest of the capital Tehran.

Human Rights Watch has identified 63 prisoners held in Karaj’s Rajai Shahr and Central Prison all of whom appear to have been convicted solely in connection to their involvement in peaceful political activities or for exercising their rights to freedom of speech, assembly, or association. The prisoners include members of the political opposition, bloggers and journalists, a lawyer, and labor, and minority rights activists.

Human Rights Watch reviewed these prisoners’ cases, including the charges against them and information from family members, lawyers, and other sources familiar with the cases. None of the information collected by Human Rights Watch suggests that any of them had any known connection to violence. Revolutionary courts have detained or convicted these persons on charges such as “acting against the national security,” and “propaganda against the state.”

During the course of its investigations of prisoners held in prisons in Karaj, Human Rights Watch also documented additional cases in which individuals may have been convicted for allegedly violent offenses, but which nonetheless raise serious questions whether the government may have targeted these individuals for their peaceful activities.

Of the 63 cases of political prisoners documented by Human Rights Watch, 59 were being held in Rajai Shahr prison. Rajai Shahr is thought to be the main prison in Karaj that holds political prisoners, and one of several prisons in the country known to hold prisoners charged with national security-related crimes.

Since the 1979 revolution, Iranian authorities have prosecuted thousands of critics, including political opposition members, civil society activists, and members of religious and ethnic minorities. Iranian revolutionary courts have subsequently convicted many of them, handing down often harsh sentences. Officials have invoked broadly or vaguely worded national security laws, many of which criminalize the exercise of fundamental rights protected under international law. Examples of these politicized crimes include “gathering and collusion against the national security,” “propaganda against the [state],” and “insult[ing] the Supreme Leader,” and “publication of lies.” Courts frequently hand down heavy, if not abusive, sentences on these charges, including heavy prison terms, flogging, fines, and work bans barring professionals, such as lawyers or journalists, from practicing their trade upon release from prison.

Iranian officials have also, in some cases, invoked other laws and charged government critics of violent “terrorism-related” crimes, such as moharebeh (“enmity against God”) and efsad-e fel arz (“sowing corruption on earth), which are vague and overbroad in both definition and application. The punishments for such crimes are severe and include death. Human Rights Watch has documented cases where prosecutors have charged critics of the government for allegedly committing crimes of violence such as terrorism, without providing sufficient, or in some cases any, evidence to establish the guilt of the accused. Revolutionary courts have subsequently convicted many of these individuals, often handing down harsh sentences. There have been numerous due process violations in many of these trials, including secret hearings, lack of access to a lawyer, long periods of incommunicado and solitary confinement, and serious allegations of torture and coerced confessions.

While many Iranian officials repeatedly and brazenly deny that Iran is holding any political prisoners, others, including President Hassan Rouhani, have implicitly acknowledged the existence of political prisoners in the country. The issue of political detainees, including the cases of political opposition leaders Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi who have been under house arrest since 2011, was a prominent theme during the 2013 presidential election campaign.

Following the election and inauguration of President Rouhani, the authorities announced the pardoning of about 80 detainees in September and October 2013. A few prominent political activists and human rights defenders were released, but many political prisoners remain behind bars.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Iranian government to immediately and unconditionally release political prisoners detained in the prisons of Karaj and all other detainees imprisoned solely for exercising their fundamental rights; to suspend key provisions of the country’s penal code that violate the rights of criminal defendants; and to introduce new criminal or penal legislation in line with its international legal obligations.

Despite a provision in the 1989 Iranian constitution mandating lawmakers to define “political offenses” and that those committing such offenses should be tried before a jury, no such law currently exists. Therefore Iran should implement a law that ensures that no one can be prosecuted simply for exercising their fundamental rights, and that those charged with any such crimes are given at least the minimum fair trial protections required under international law.

Recommendations

To the Iranian Government

Arbitrary Arrests and Treatment in Detention

- Release all individuals currently deprived of their liberty for peacefully exercising their rights to free expression, association, and assembly;

- Ensure that all persons deprived of their liberty receive family visits, and inform relatives of the location and status of family members in detention;

- Abolish the use of prolonged solitary confinement;

- Investigate and respond promptly to all complaints of torture and ill-treatment;

- Discipline or prosecute as appropriate security, intelligence, judiciary, and other officials at all levels who are responsible for the torture and mistreatment of detainees in custody;

Legal Reform

- Implement laws that ensures that no one can be prosecuted simply for exercising their fundamental rights, and that those charged with any such crimes are given at least the minimum fair trial protections required under international law;

- Abolish or amend vague or overly broad

crimes such as or efsad-e fel arz (“sowing corruption”):

- Narrowly define and identify the elements of conduct under this offense that constitute a crime, including defining a “center of corruption,” so as to ensure that conduct that is protected under international law, such as the exercise of human rights like freedom of expression or association, is not criminalized under these provisions;

- Remove the death penalty for this offense, beginning with crimes not considered “serious” under international law, including “publishing lies,” “damaging the economy of the country,” and “operat[ing] or managing centers of corruption or prostitution”;

- Amend or abolish the vague security laws under the Islamic Penal Code and other legislation under the Islamic Penal Code that permits the government to arbitrarily suppress and punish individuals for peaceful political expression, in breach of the government’s international legal obligations, on grounds that “national security” is being endangered. The following provisions are particularly problematic:

- Articles 498-99 which criminalize the establishment of, and membership in, any group that aims to “disrupt national security”;

- Article 500, which sets a sentence of three months to one year of imprisonment for anyone found guilty of “in any way advertising against the order of the Islamic Republic of Iran or advertising for the benefit of groups or institutions against the order”;

- Article 610 , which designates “gathering or collusion against the domestic or international security of the nation or commissioning such acts” as a crime punishable from two to five years of imprisonment;

- Article 618, which criminalizes “disrupting the order and comfort and calm of the general public or preventing people from work” and allows for a sentence of 3 months to one year, and up to 74 lashes;

- Article 513, which criminalizes any “insults” to any of the “Islamic sanctities” or holy figures in Islam and carries a punishment of one to five years, and in some instances may carry a death penalty;

- Article 514, which criminalizes any “insults” directed at the first leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, or the current leader, and authorizes punishment ranging from six months to two years in prison;

- Article 609, which criminalizes “insults” to other government officials including the heads of the executive, legislative and judiciary branches and allows for a sentence of three to six months, 74 lashes or monetary fines;

- Article 698, which criminalizes anyone “disrupt[ing] the opinion of the authorities or the public” by publishing “lies”;

- Remove all provisions that allow for punishments that amount to torture or cruel and degrading treatment, including flogging;

- Amend the penal code by adopting a definition of torture consistent with article 1 of the Convention against Torture to ensure that all acts of torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment are criminal offenses, including criminalizing command responsibility for such acts committed by subordinates and that penalties reflect the grave nature of such offenses.

- Change provisions in the Code of Criminal Procedure that allow the right to counsel to be denied in the investigative phase of pre-trial detention. The government should guarantee the right of security detainees to meet in private with legal counsel throughout the period of their detention and trial;

- Remove any and all references to the death penalty in the penal code and abolish its use;

- Abolish the death penalty completely and immediately for child offenders, including those charged with categories of crimes for which death sentences can still be issued by courts (i.e. “crimes against God” or “retribution crimes”);

Implementation of Recent Amendments to the Penal Code

- Implement Article 134 of the new Islamic Penal Code which requires convicts with multiple charges to receive only the maximum penalty for their most serious charges, rather than consecutive penalties for each lesser charge;

- Implement recent amendments to the penal code that forbid execution of individuals convicted of moharebeh or efsad-e fel arz who have not personally used weapons or resorted to violence.

Cooperation with UN Rights Bodies

- Fully cooperate with all UN rights bodies and allow the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Iran, to visit Iran to meet with officials and conduct independent investigations.

Methodology

The Iranian government does not allow international human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch to enter the country to conduct independent investigations into human rights abuses. Iranian activists, journalists, human rights lawyers, relatives of political prisoners and former political prisoners are often not comfortable carrying out extended conversations on human rights issues via telephone or email, fearing government surveillance. The government often accuses its critics inside Iran, including human rights activists, of being agents of foreign states or entities, and prosecutes them under Iran’s national security laws.

In this report, Human Rights Watch users the term “political prisoner” for anyone whose case it could review closely, based on the available information, and it believes is currently being detained by the Iranian government solely due to the peaceful exercise of their fundamental rights such as freedom of speech, assembly or association, religion, opinion or other rights protected by international human rights law. The list of political prisoners in Karaj prisons compiled here may not be exhaustive.

Human Rights Watch documented most of the cases presented in this report through telephone interviews and email correspondence conducted between November 2013 and July 2014. Those who provided information included former political prisoners, relatives of political prisoners, lawyers, activists, and others familiar with the cases.

Human Rights Watch also relied on earlier research on political prisoners in Iran we had conducted in the past five years. That research also took the form of interviews with individuals familiar with the cases. Human Rights Watch has already published the findings of this earlier research in reports, press releases, and other material released during the past five years. In cases where we relied on earlier research we updated the information where necessary.

All of the interviews were conducted in Persian (Farsi). Names of some of those interviewed have been withheld to protect their security.

The list of political prisoners included in this report has been updated through July 2014.

I. Background

Iran’s “National Security” and Anti-Terrorism Laws

The Iranian penal code’s national security laws constitute the government’s primary legal tool for stifling dissent. These laws fall into two categories: laws which carry ta’zir, or “discretionary punishments,[1] and laws which carry hadd (plural hodud) punishments, or punishments that are specified in Sharia law.[2] These laws are so broadly worded as to allow the authorities to punish a range of peaceful activities and free expression with the legal cover of protecting national security. The “discretionary punishment” provisions of national security offenses have been in place since 1996, and the government has frequently relied on them to severely punish perceived critics for exercising their rights to freedom of expression, association, and assembly.[3]

In January 2012, the Guardian Council, an unelected body of 12 religious jurists charged with vetting all legislation to ensure its compatibility with Iran’s constitution and Sharia (Islamic law), approved the text of a new penal code that amended the hodud provisions of the penal code.[4] The government implemented the new version of the penal code in early 2013. However, these new penal provisions failed to make any changes to address the overly broad or vaguely defined national security laws that carried “discretionary punishments, and are the criminal provisions most commonly used by revolutionary courts to prosecute and imprison government critics.”[5]

Many of the penal code’s national security laws criminalize the exercise of fundamental rights. Crimes that fall under these laws include “gathering and collusion against the national security,”[6] “propaganda against the [state],”[7] “disrupt[ing] public order,”[8] and establishing or membership in groups “aiming to disrupt the national security.”[9] Additionally, to silence government critics courts have resorted to other “discretionary punishments” related to criminal defamation laws such as “insult[ing] the sacred values of Islam or any of the Great Prophets or [twelve] Shi’ite Imams,”[10] “insult[ing] the Supreme Leader,”[11] “insult[ing] other public officials (such as the Head of the Judiciary or President)[12] and “disrupt[ing] the opinion of the authorities or the public” by publishing lies.[13]

Courts have handed down heavy sentences to those convicted on these charges including prison terms of up to 10 years per crime, flogging, fines, and work bans barring professionals, such as lawyers or journalists, from practicing their trade upon release from prison.[14] Human Rights Watch has documented cases where authorities have sentenced peaceful activists convicted of these national security crimes to imprisonment of 20 years or more in cases where the individuals are found guilty of several crimes.[15] In certain circumstances, new provisions of the amended penal code allow for a reduction of prison sentences for individuals convicted of multiple national security crimes.[16]It is not clear, however, whether the Judiciary is systematically reassessing appeals by lawyers of clients whose cases may qualify for judicial review.[17]

Prior to the implementation of the amended penal code in 2013, Iran’s judiciary generally charged defendants alleged to have taken part in violent or terrorism-related activities with the crime of moharebeh (“enmity against God”) or efsad-e fel arz (“sowing corruption on earth.”)[18]

For example, under articles 186 and 190-91 of the old penal code (which the judiciary invoked to sentence some of those currently serving time in Karaj prisons), anyone found responsible for taking up arms against the state, or belonging to an organization taking up arms against the state, was considered guilty of “enmity against God” and sentenced to death.[19] Furthermore, under these old code provisions there was no legal distinction between individuals who were supporters or members of armed opposition groups who did not participate in violence, and those who were involved in armed activities—both could receive the death penalty.

The amended penal code retains the crime of moharebeh, but limits its definition to anyone who threatens public security by “drawing arms” with the intent to kill, injure, steal, or frighten others.[20] This definition is different from the definition in the old code, which allowed for the death penalty for individuals who were members of any group (including political opposition groups) that engaged in armed resistance or terrorism against the state. The crime of enmity against God in the new code also covers robbery and trafficking involving armed activities.[21] As in the old code, the penalty for this offensemay be death, amputation, crucifixion (not entailing death), or internal exile, and lies at the discretion of the judge.[22]

The amended penal code greatly expands the crime of efsad-e fel arz for which the penalty is death. Under the new definition of “sowing corruption on earth,” a court may convict someone of sowing corruption if he is found to have “committed crimes against the physical well-being of the public, internal or external security, published lies, damaged the economy of the country, engaged in destruction and sabotage…or operated or managed centers of corruption or prostitution in a way that seriously disturbs the public order and security of the nation.”[23]

The amended code also introduces the wholly new hadd crime of baghi, or “armed rebellion,” which targets individuals engaged in armed resistance against the state.[24] It provides that the members of any group that opposes the ideals of the Islamic Republic and who take up arms to further the group’s goals will be sentenced to death.[25] In instances where authorities arrest members of the armed or terrorist group who have not used weapons or resorted to violence, however, courts will sentence the members to imprisonment not exceeding 15 years (though the group will still be considered an armed or terrorist group).[26]

This second provision is arguably an improvement over article 186 of the old code in that it distinguishes between members of armed or “terrorist groups” who use or carry arms, and those who do not. The new, more restricted, definition of moharebeh, and the newly defined crime of baghi, do not necessarily infringe on the exercise of fundamental rights that are protected under international law, but the punishments available for these crimes (death, amputation, and crucifixion) violate the right to life or the prohibition against torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.[27] Human Rights Watch opposes the death penalty in all circumstances an inherently cruel and irreversible punishment.

Many detainees currently serving long prison sentences or waiting in prison for their death sentences to be carried out on terrorism-related charges were convicted prior to the implementation of the new penal code amendments in 2013. In two cases reviewed by Human Rights Watch, however, the detainee’s request for review of his death sentence on these grounds did not stop his execution.[28]

According to Ehsan Mojtavi, a lawyer who represented a Kurdish dissident executed in October 2013 for his alleged ties to an armed Kurdish group, Iran’s criminal law allows those convicted under the old penal code to request a review of their sentence if the new code imposes a lighter punishment.[29] People who never engaged in violence themselves, but were convicted under the old moharebeh provisions for supporting armed opposition groups can request a review by the country’s Supreme Court, which may reduce a death sentence to imprisonment not to exceed 15 years.

In another case, authorities at Rajai Shahr prison hanged Gholamreza Khosravi Savadjani, convicted of moharebeh for assisting the Mojahedin-e Khalq Organization (MEK), on June 1, 2014.[30] The Iranian government considers the MEK to be a terrorist organization. Khosravi’s execution went forth despite numerous procedural deficiencies in his case, and the recent amendments in the penal code that should have qualified Khosravi’s case for further judicial review and converted his death sentence to imprisonment.[31]

Human Rights Watch has criticized both the old and amended penal codes for their overly broad or vaguely worded definitions of terrorism-related crimes.[32] In numerous cases revolutionary courts sentenced individuals to death for moharebeh where no evidence existed that the defendant had resorted to violence, or based on extremely tenuous links with the alleged terrorist groups (including support for their political ideals).[33] In some cases security forces used physical and psychological coercion, including torture, to secure false confessions in security-related cases, and courts have convicted defendants of moharebeh in trials where prosecutors relied primarily, if not solely, on confessions, and failed to provide any other convincing evidence establishing the defendant’s guilt.[34]

Iran’s constitution provides little protection from such ambiguous and overbroad criminal laws. While the constitution sets out basic rights to expression, assembly, and association, these are invariably weakened by broadly defined exceptions. Article 24 of the constitution grants freedom of the press and publication “except when it is detrimental to the fundamental principles of Islam or the rights of the public.[35] Article 26 states that freedom of association is granted except in cases that “violate the principles of independence, freedom, national unity, the criteria of Islam, or the basis of the Islamic Republic.”[36] Article 27 guarantees the right to peaceful assembly again with the exception of cases deemed to be “detrimental to the fundamental principles of Islam.”[37]

Article 168 of Iran’s constitution, amended in 1989, states: “Political and press offenses will be tried openly and in the presence of a jury, in courts of justice. The manner of the selection of the jury, its powers, and the definition of political offences, will be determined by law in accordance with the Islamic criteria.” In light of this provision, Iran should implement a law that ensures that no one can be prosecuted simply for exercising their fundamental rights, and that those charged with any such crimes are given at least the minimum fair trial protections required under international law.[38]

Number of Political Prisoners in Iran

There is no clarity on the number of political prisoners in Iran. In March 2014 the special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran, Ahmed Shaheed, reported to the UN Human Rights Council, that “at least 895 ‘prisoners of conscience’ and ‘political prisoners’ were reportedly imprisoned” in Iranian prisons.[39]

Some Iranian officials have denied assertions by Iranian rights activists, human rights organizations and UN bodies that Iran has imprisoned large numbers of persons solely because they exercised their fundamental rights, such as freedom of speech, assembly, or association.[40] On December 3, 2013, the head of Iran’s judiciary, Ayatollah Sadegh Amoli Larijani, called such assertions“a very big lie.”[41]

However other officials including Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, have implicitly acknowledged that there are political detainees in Iran.[42] During the 2013 election campaign that brought Rouhani to power the issue of political prisoners, including the cases of political opposition leaders Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi who have been under house arrest since 2011, was a prominent theme.

Following the election and inauguration of President Rouhani, in September and October 2013, authorities pardoned about 80 detainees, including releasing a few prominent political activists and human rights defenders.[43] Among those released was Nasrin Sotoudeh, a well-known lawyer and rights defender, freed on September 18 after she had served three years of a six-year prison sentence.[44] However many political prisoners remain behind bars, including the Karaj detainees whose cases are presented in this report.

II. Political Prisoners in Karaj Prisons

The city of Karaj is situated about 47 kilometers northwest of Iran’s capital Tehran. It is the principle city of Alborz province. There are three main prisons in the city: Rajai Shahr prison, Ghezel Hesar prison, and the Central Prison at Karaj. Human Rights Watch’s investigation identified 63 prisoners held in Karaj prisons, including 59 in Rajai Shahr prison and 4 in Central Prison at Karaj, who appear to have been convicted solely in connection with their involvement in peaceful political activities or for exercising their rights to freedom of speech, assembly, or association.

Human Rights Watch review of these prisoners’ cases included the charges against them and firsthand information from family members, lawyers, and other sources familiar with the cases. None of the evidence suggests that any of them had any known connection to violence. Revolutionary courts have detained or convicted these activists on national security charges such as “gathering and collusion against the national security,” “propaganda against the state,” and “spreading corruption on earth.” They are serving prison sentences ranging from 4 to 20 years.

The largest number of political prisoners in Karaj are at Rajai Shahr prison. Rajai Shahr prison, also known as Gohardasht prison, is located in northwestern Karaj. Statements and other information gathered by Human Rights Watch suggest that many of the prisoners detained in Rajai Shahr prison for violating “national security” laws are currently held in Ward 4.

The largest number of political prisoners in Karaj are at Rajai Shahr prison. Rajai Shahr prison, also known as Gohardasht prison, is located in northwestern Karaj.

A source familiar with the situation in the prison told Human Rights Watch that one of the most critical issues for political prisoners in Rajai Shahr is access to medical care.[45]

Despite the efforts of the prison’s infirmary to resolve some of these problems, prisoners still struggle with a lack of medication and specialist care. Additionally, the prisoners suffer from an ongoing cycle of being taken to hospitals outside the prison and being returned [to prison] prior to full recovery. Not to mention that the right to medical furloughs, especially for those who are suffering from serious [ailments], is often denied.[46]

During the course of its investigations Human Rights Watch also gathered similar accounts from prisoners in Karaj’s two other prison facilities, Ghezel Hesar prison and the Central Prison.

Journalists, Bloggers and Social Media Activists

Human Rights Watch has identified nine journalists and bloggers held in Karaj who qualify as political prisoners. All of them are in Rajai Shahr prison except for one.

According to Reporters Without Borders there are at least 62 journalists and bloggers in Iran’s prisons, making Iran one of the largest jailers of journalists in the world.[47] The Iranian judiciary imposes harsh sentences on journalists and bloggers based on vague and ill-defined press and security laws such as “acting against the national security,” “propaganda against the state,” “publishing lies,” and insulting the prophets or government officials such as the president, or Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.[48]

Bahman Ahmadi-Amoui © 2014 Private

Bahman Ahmadi-Amoui, a journalist who had written articles critical of the government on his website and in official newspapers, is serving a four-year sentence in Rajai Shahr after his arrest on June 20, 2009. Officials arrested him following the disputed elections and prosecuted him on charges of “propaganda against the state,” “insulting the president,” and “acting against the national security.” A revolutionary court sentenced him to seven years and four months in prison and 34 lashes, which was reduced on appeal to four years.[49]

Authorities transferred Ahmadi-Amoui on June 12, 2012, from Tehran’s Evin prison to a solitary cell in Rajai Shahr. At the time, a source familiar with the case told Human Rights Watch that during the transfer, authorities harassed and insulted Ahmadi-Amoui before sending him to solitary confinement. Five days later, authorities finally moved Ahmadi-Amoui out of solitary confinement and into Room 12. They allowed his wife, Jila Baniyaghoob, to visit him for the first time in 50 days, a source close to the family told Human Rights Watch.[50]

Another Iranian journalist, Keyvan Samimi, 66, is also detained in Ward 4, Room 12 of Rajai Shahr prison, according to a former prisoner and other sources. Samimi was the editor-in-chief of the banned reformist newspaper Nameh and blogged on the banned site Kharabaat, which published dissenting opinions. He was also a member of the Society in Defense of Press Freedom, the Committee to Pursue Arbitrary Arrests, and the Committee to Defend the Right To Education. Security forces in June 2009 broke into his house in the middle of the night, confiscated his personal belongings, and arrested him. Officials of the judiciary accused Samimi of crimes related to his journalism, including “propaganda against the state,” “conspiring against national security,” “participating in post-election protests,” and “issuing statements questioning the validity of the election results.”[51]

A Tehran revolutionary court in 2009 convicted him of all of these charges and sentenced him to six years in prison and a lifetime ban from any journalistic, social, or political activity, though a Tehran appellate court later reduced the ban to 15 years. Samimi had been serving his sentence in Ward 350 of Evin prison until September 2012, when prison authorities transferred him to a solitary cell in Rajai Shahr prison, according to rights groups. Although he suffers from various ailments, including a liver tumor and arthritis, officials have repeatedly denied him medical leave, according to rights groups.[52]

The authorities are also holding a 53-year-old blogger, Mohammad-Reza Pourshajari, in Karaj’s Central Prison, a separate facility that normally houses detainees convicted in Karaj courts. In 2010 the authorities tried and convicted Pourshajari, who is also known by his pen name, Siamak Mehr, on charges of “acting against the national security,” “insulting Ayatollah Khomeini,” and “insulting [religious] sanctities” for writings he posted on his personal blog, his daughter told Human Rights Watch. Pourshajari suffers

Mohammad-Reza Pourshajari © 2014 Private

from serious heart ailments and authorities have consistently denied him proper medical care, his daughter said.[53] In a June 10, 2013 audio recording obtained by Human Rights Watch, a voice identified as Pourshajari’s says that authorities beat and tortured him and threatened to hang him after forcing him to stand on a four-legged stool during his initial detention following his arrest on September 12, 2010. He also says that authorities held him in solitary confinement for eight consecutive months and that interrogators repeatedly threatened to send him to the gallows.[54]

Other journalists currently detained in Rajai Shahr prison include: Masoud Bastani, Saeed Razavi-Faghih, Ahmad Zeidabadi, Mohammad (Kourosh) Nasiri, Kamran Ayazi, and Mohammad Akrami.[55]

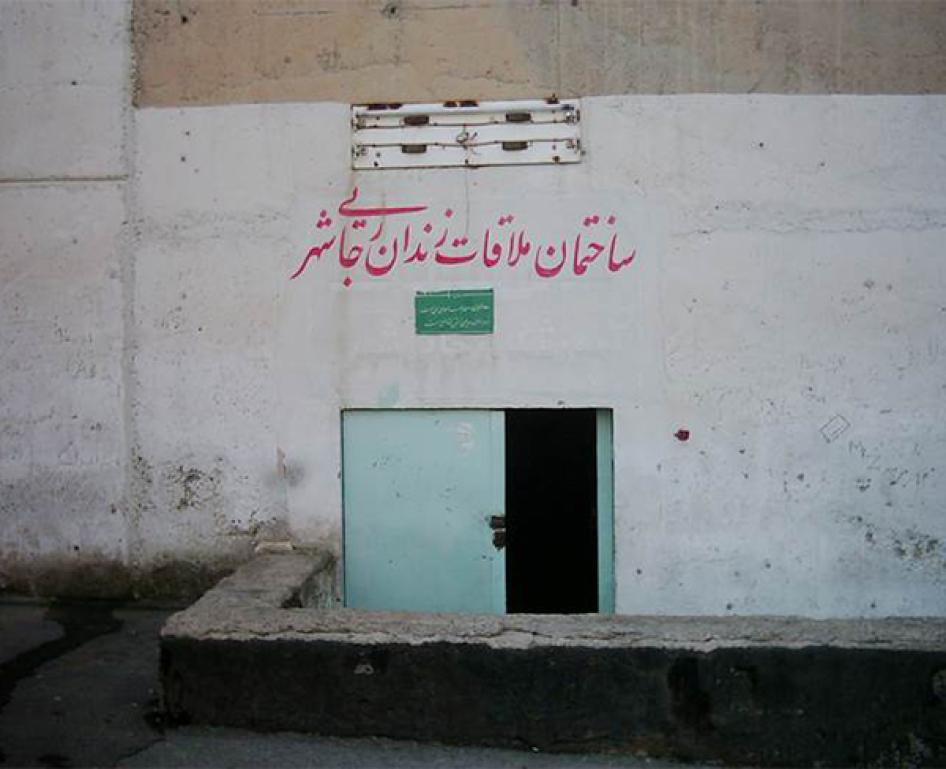

The Central Prison at Karaj is adjacent to Ghezel Hesar prison. After authorities separated Alborz province from Tehran they sent prisoners convicted in Alborz courts to this prison.

Lawyers and Other Rights Defenders

Human Rights Watch’s investigation has identified seven rights defenders and one lawyer who are imprisoned in Karaj. All are detained in Rajai Shahr prison.

Authorities are holding lawyer Mohammad Seifzadeh, who is 67 years old, in Rajai Shahr prison. He is a former colleague of Nobel Peace laureate Shirin Ebadi who cofounded the Defenders of Human Rights Center with Ebadi and several other lawyers. In October 2010, a revolutionary court convicted Seifzadeh of charges including “acting against national security through establishing the Defenders of Human Rights Center,” according to the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. An appeals court later reduced his nine-year sentence to two years, but in March 2013, Branch 15 of Tehran’s Revolutionary Court sentenced Seifzadeh to another six years in prison for “assembly and collusion against the national security” for writing critical letters to former President Khatami and signing several group statements while in prison, Ebadi told Human Rights Watch.[56]

The authorities are also holding several student and labor rights activists at Rajai Shahr prison. On Student Day in December 2009, students demonstrated on university campuses throughout Iran, to protest the results of the disputed June 2009 presidential election. Authorities arrested student protesters, including Majid Tavakoli, a 23-year-old student at Amirkabir University and member of the school’s Islamic Student Association, who gave a speech criticizing the government. In 2009 a revolutionary court sentenced Tavakoli to eight-and-a-half years in prison on various national security charges related to his speech, including “conspiring against the national security,” “propaganda against the regime,” and “insulting the Supreme Leader” and president. Authorities later transferred Tavakoli from Evin prison in Tehran to Rajai Shahr, according to rights groups. He is currently being held in Ward 4, Room 12, said a former prisoner.[57]

Shahrokh Zamani, a labor rights activist, is another inmate at Rajai Shahr prison. In 2011, a revolutionary court convicted Zamani, 55, of charges of “assembly and collusion against the national security,” “establishing an illegal group,” “propaganda against the state,” and “insulting the Supreme Leader,” and sentenced him to 11.5 years in prison, solely in connection with his activities as a member of an independent painters’ syndicate and a board member of the Committee to Pursue the Establishment of Labor Unions, according to a source familiar with his case.[58]

Authorities arrested Rasoul Bodaghi, a labor and teacher union activist, in September 2009. Prosecutors later charged him with “propaganda against the state” and “collusion and gathering against the national security.” A source familiar with Bodaghi’s case told Human Rights Watch that for evidence of his “crimes” prosecutors presented proof that he had attended teachers’ assemblies, participated in anti-government rallies following the disputed 2009 presidential election. The source said that Bodaghi’s trial, which took place in 2010, lasted only two minutes, during which the prosecution read the verdict and the court issued a verdict. The judiciary sentenced Bodaghi to six years’ imprisonment on the collusion and propaganda charges, and imposed a five year ban on his ability to participate in union activities after his release.[59]

Jafar Eghdami © 2014 Private

Authorities convicted Jafar Eghdami, a rights activist, on charges of moharebeh or “enmity against God,” according to a source familiar with the case. The source told Human Rights Watch that Eghdami was arrested after attending memorial services at Khavaran Cemetery in Tehran, where hundreds of members of the Mojahedin-e Khalq and leftist groups are believed to have been buried after summary executions in several prisons in and near Tehran, including Rajai Shahr, in 1988 (then called Gohardasht prison). The source also said intelligence officials accused Eghdami of having contacts with the MEK, which has acknowledged carrying out violent attacks in Iran. When Eghdami denied these charges and intelligence officials subjected him to harsh interrogations and psychological torture during pretrial detention. During Eghdami’s trial sessions, which were held in private in violation of international law, revolutionary court judges threatened his lawyers and prevented them from mounting a defense, the source said.[60]

The source told Human Rights Watch that a Tehran revolutionary court initially sentenced Eghdami to five years’ internal exile in a prison in southeastern Iran, but the prosecutor appealed the decision and he ultimately received a 10-year sentence, which he is currently serving in Rajai Shahr prison.[61]

Other rights defenders currently detained in Rajai Shahr prison include: Reza Shahabi, Mehdi Farahi Shandiz, and Navid Khanjani[62].

Religious Minority Activists and Community Leaders

Human Rights Watch’s investigation identified 38 peaceful religious activists and community leaders, the majority of them are members of Iran’s Baha’i minority, whom the Iranian authorities are holding at both Rajai Shahr prison and the Central Prison in Karaj. At least 136 Baha’is are detained in Iranian prisons for their peaceful activities.[63]

Saeed Rezaei © 2014 Private

Baha’i leaders Jamaloddin Khanjani, Afif Naeimi, Saeed Rezaei, Behrouz Azizi Tavakoli, and Vahid Tizfahm are each serving 20-year prison sentences in Rajai Shahr. Security forces arrested these men, along with two female leaders now in detention at another facility, between May 8 and May 14, 2008. After holding the seven in Evin prison in Tehran for 20 months without charge, officials on January 12, 2010 brought charges that included spying, “insulting religious sanctities,” and “spreading corruption on earth.” All the charges were related to their peaceful activities as leaders of the Baha’i community. Authorities have often leveled the charge of spying against Baha’is because of the faith’s supposed links to Israel (the tomb of the faith’s founder, Baha’u’llah, is near Acre in what is now Israel).[64] A lawyer familiar with the case of these Baha’i leaders told Human Rights Watch that the government provided no evidence at trial to substantiate the government’s espionage charges.[65]

Authorities refused bail to the five men and two women and allowed them only limited visits with immediate family members and lawyers, according to sources familiar with their case.

The visitation room at Rajai Shahr prison © 2004 Private

Their trial began January 12, 2010, and consisted of six brief closed-door hearings, the last on June 14, 2010, before a Tehran revolutionary court found all of them guilty as charged.[66]

In 2011, authorities raided the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education, an online correspondence university created in 1987 to serve Baha’is, whom the government systematically bars from university education. Officers arrested and jailed at least 30 faculty members and administrators. Revolutionary courts convicted them of “membership in the unlawful” university, and “membership in the subversive Baha’i group with the intent to act against the national security,” and sentenced them to prison.[67] At least 11 of these 30 faculty members and administrators are detained in Ward 4, Room 12 of Rajai Shahr prison, according to a former prisoner and another source familiar with these cases.[68]

The authorities are also holding two Christian pastors and two Christian converts in prisons in Karaj. The family of Saeed Abedini, a Christian pastor, has said that he is detained in Ward 4 Room 12 of Rajai Shahr prison.[69] A revolutionary court convicted him of “intent to endanger the national security” by establishing and running home churches, and sentenced him to eight years in prison[70]

Authorities are also holding Christian pastor Behanam Irani, Hossein Saketi Aramsari (also known as “Stephen”) and Reza Rabbani (also known as “Silas”) at the Central Prison in Karaj, a source familiar with the cases told Human Rights Watch.[71] Armed security and intelligence forces entered pastor Irani’s home in April 2010 and arrested him for performing ceremonies in a private home with a small group of other Iranian Christians. A revolutionary court had previously convicted Irani in 2008 of acting “against national security” and “propaganda against the system” for proselytizing, and issued a suspended five-year sentence against him. After the 2010 arrest, however, a revolutionary court revived the initial sentence, the source said. The court relied on Irani’s admission that he was a Christian convert and pastor, and on testimony from witnesses who accused him of tricking them into adopting the Christian faith.[72] Saketi Aramsari is currently serving a one-year prison term on the charge of “propaganda against the system,” according to the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran and the source familiar with these two cases.[73]

Iranian security and intelligence forces consider proselytizing by Christians a security threat and has systematically targeted those involved—especially those not affiliated with Iran’s indigenous Christian communities, such as Armenians, Assyrians, and Chaldeans.[74]

Other religious minority activists detained in Karaj prisons for exercising their fundamental rights include: Farhad Sedgh, Ramin Zibaei, Mahmoud Badavam, Riazollah Sobhani, Shahin Negari, Kamran Mortazavi, Kamran Rahimian, Keyvan Rahimian, Aziz Samandari, Amanollah Mostaghim, Fouad Moghadam, Didar Raoufi, Ighan Shahidi, Fouad Khanjani, Fouad Fahandej, Farhad Fahandej, Kourosh Ziari, Farahmand Sanaei, Kamal Kashani, Payam Markazi, Shahram Chinian, Afshin Heyratian, Siamak Sadri, Peyman Kashfi, Adel Naimi, Sarang Ettehadi, Shahab Dehghani, Shamim Naeimi,and Shahrokh Taef.

Political Activists

Human Rights Watch’s investigation has identified eight prisoners in Karaj who have been imprisoned solely because of their peaceful political activism. All are detained in Rajai Shahr prison.

Throughout Iran members of reformist parties and other government opponents are serving sentences stemming from the government crackdown after the disputed 2009 election. Many had unfair trials before revolutionary courts, whose judges fail to ensure basic due process standards. Revolutionary courts sentenced some after mass show trials during which they were indicted on patently political charges such as “actions against the national security,” “propaganda against the regime,” “membership in illegal groups,” and “disturbing public order.” Some defendants were made to confess before television cameras, in violation of the right under international law to not be compelled to testify against oneself.[75]

Heshmatollah Tabarzadi © 2014 Private

On September 27, 2010, more than a year after the start of protests against the result of the 2009 election, Iran’s general prosecutor and judiciary spokesman, Gholamhossein Mohseni-Ejei, announced a court order dissolving both the Islamic Iran Participation Front and the Mojahedin of the Islamic Revolution, pro-reform parties.[76] Authorities have also prevented members of other opposition groups, like the Freedom Movement party, from holding gatherings.

Mehdi Mahmoudian, an opposition political activist linked to the reformist and now banned Islamic Iran Participation Front party, is currently serving a five-year prison sentence in Rajai Shashr prison. A Tehran revolutionary court convicted him of “assembly and collusion against the national security” for his reports on abuses in Kahrizak Detention Facility, according to the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.[77]

Other political activists currently detained in Rajai Shahr prison include: Mostafa Nili, Hamid Motamedi-Mehr, Mehdi Abiat, Saeed Madani, Mostafa Eskandari, Behzad Arabgol, and Heshmatollah Tabarzadi.

List of Political Prisoners in Karaj Prisons

Labor and Teachers’ Union Activists

|

1 |

Shahrokh Zamani

|

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; labor rights activist tried and convicted of “assembly and collusion against the nationals security,” “establishing an illegal group,” “propaganda against the state,” and “insulting the Supreme Leader” solely in connection with his activities as a member of an independent painters’ syndicate and a board member of the Committee to Pursue the Establishment of Labor Unions |

11.5 years [78] |

|

2 |

Rasoul Bodaghi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; member of teachers’ trade union tried and convicted of “propaganda against the state,” “assembly and collusion against the national security,” and “participating in illegal gatherings” |

six years [79]

|

|

3 |

Mehdi Farahi Shandiz |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; labor rights activist tried and convicted for “insulting the Supreme Leader” and “disturbing the public order” |

three years [80] |

|

4 |

Reza Shahabi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; labor rights activist tried and convicted of “propaganda against the state,” “assembly and collusion against the national security” |

four years [81] |

Political Activists and Opposition Members: [82]

|

5 |

Mostafa Nili |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a political activist tried and convicted for “assembly and collusion against the national security for participating in anti-government demonstrations following the disputed 2009 presidential election |

three and a half years[83] |

|

6 |

Mehdi Mahmoudian |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; political opposition member tried and convicted of “assembly and collusion against the national security” for his journalism on abuses that took place in Kahrizak Detention Facility and his links to the reformist and now banned Islamic Iran Participation Front party |

five years[84] |

|

7 |

Hamid Motamedi-Mehr |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a political activist and opposition member tried and convicted for “membership in an illegal group” (i.e. the Freedom Movement), “propaganda against the state,” and participating in illegal demonstrations” |

five years[85] |

|

8 |

Heshmatollah Tabarzadi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a political activist, opposition member, and journalist tried and convicted for “propaganda against the system,” “assembly and collusion against the national security,” and “insulting the Supreme Leader” |

eight years[86] |

|

9 |

Mostafa Eskandari |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a political activist tried and convicted for “propaganda against the state,” assembly and collusion against the national security,” “insulting the President,” and “insulting the Supreme Leader” |

eight and a half years[87] |

|

10 |

Mehdi Abiat |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; student and protester tried convicted of “insulting the Supreme Leader and government officials and “disrupting the public order” |

two and a half years; later reduced to 15 months via a partial amnesty[88] |

|

11 |

Saeed Madani |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; political activist and academic convicted of “assembly and collusion against the national security” and “propaganda against the state” |

six years[89] |

|

12 |

Behzad Arabgol |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; political activist and protester convicted of “assembly and collusion against the national security,” and disobeying (police) orders |

4 years[90] |

Lawyers and Other Rights Defenders

|

13 |

Mohammad Seifzadeh |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a lawyer and rights defender tried and convicted for his professional activities on “acting against national security through establishing the Defenders of Human Rights Center” (a rights group cofounded with Nobel Peace Laureate Shirin Ebadi); “assembly and collusion against the national security” (for writing critical letters and signing several group statements while in prison) |

8 years[91]

|

|

14 |

Majid Tavakoli |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; student activist tried and convicted of “conspiring against national security,” “propaganda against the state,” and “insulting the Supreme Leader and president” |

eight and a half years[92]

|

|

15 |

Jafar Eghdami |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; rights activist tried and convicted of moharebeh or “enmity against God,” on evidence that allegedly consisted of visiting a cemetery where hundreds of MEK members are believed to be buried |

10 years[93] |

|

16 |

Navid Khanjani |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i and rights activist previously denied the right to university education; convicted of “membership in the “Committee of Human Rights Reporters and Human Rights Activists group; “establishing a group for students deprived of education”; “disturbing the public opinion and propaganda against the state [by publishing news and reports and conducting interviews with foreign television and radio,” and “publishing lies” |

12 years[94]

|

Journalists, Bloggers and Social Media Activists

|

17 |

Masoud Bastani |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; journalist tried and convicted for his writings on “propaganda against the state,” “disturbing the public order,” and assembly and collusion against the national security” |

six years[95]

|

|

18 |

Bahman Ahmadi Amoui |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; journalist tried and convicted on “propaganda against the state, “insulting the president,” and “acting against the national security” on the basis of his writings criticizing the Ahmadinejad government |

five years[96]

|

|

19 |

Keyvan Samimi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; journalist and political/rights activist tried and convicted of “propaganda against the state,” “assembly and collusion against the conspiring against national security,” and “participating in illegal protests” (following the disputed 2009 presidential election) |

six years[97]

|

|

20 |

Ahmad Zeidabadi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a journalist tried and convicted of “assembly and collusion against the national security” and “propaganda against the state” solely for his publications and professional activities |

six years[98]

|

|

21 |

Saeed Razavi-Faghih |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a journalist and reformist tried and convicted of “propaganda against the state,” “participation in illegal demonstrations,” and “insulting the Supreme Leader |

four years[99]

|

|

22 |

Mehdi Abiat |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a blogger tried and convicted of “insulting the Supreme Leader and government officials and “disrupting the public order |

two and a half years later reduced to 15 months via a partial amnesty[100] |

|

23 |

Mohammad-Reza Pourshajari |

Held in Central Prison at Karaj; a blogger tried and convicted for “acting against the national security,” “insulting Ayatollah Khomeini,” and “insulting [religious] sanctities” for writings he posted on his personal blog |

four years[101]

|

|

24 |

Mohammad Akrami |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a blogger charged with “propaganda against the state” for his social media (mostly Facebook) activities and postings[102] |

|

|

25 |

Mohammad (Kourosh) Nasiri |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a blogger tried and convicted for “insulting the holy sanctities,” “insulting the Supreme Leader,” “propaganda against the state,” for taking part in a Facebook posting |

5 years[103]

|

|

26 |

Kamran Ayazi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a blogger tried and convicted for “assembly and collusion against the national security” and “insulting the holy sanctities” for his internet activities |

9 years[104]

|

Religious Minorities/Activists [105]

|

27 |

Saeed Abedini |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Christian convert who established and ran home churches, was tried and convicted for “the intent to endanger national security” |

eight years[106]

|

|

28 |

Behnam Irani |

Held in Central Prison at Karaj; Christian pastor and convert tried and convicted for “against national security” and “propaganda against the system” because of his proselytizing |

five years[107]

|

|

29 |

Hossein Saketi Aramsari |

Held in Central Prison at Karaj; Christian convert tried and convicted for “propaganda against the system” because of his proselytizing |

one year[108]

|

|

30 |

Jamalodin Khanjani |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a leader of Iran’s Baha’i community on espionage for Israel, “insulting religious sanctities”, “propaganda against the state,” “corruption on earth” |

20 years[109] |

|

31 |

Behrouz Azizi Tavakoli |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a leader of Iran’s Baha’i community on espionage for Israel, “insulting religious sanctities”, “propaganda against the state,” “corruption on earth” |

20 years[110] |

|

32 |

Afif Naeimi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a leader of Iran’s Baha’i community on espionage for Israel, “insulting religious sanctities”, “propaganda against the state,” “corruption on earth” |

20 years[111] |

|

33 |

Vahid Tizfahm |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a leader of Iran’s Baha’i community on espionage for Israel, “insulting religious sanctities”, “propaganda against the state,” “corruption on earth” |

20 years[112] |

|

34 |

Saeed Rezaei |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a leader of Iran’s Baha’i community on espionage for Israel, “insulting religious sanctities”, “propaganda against the state,” “corruption on earth” |

20 years[113] |

|

35 |

Farhad Sedghi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a member of and educator for the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education for “membership in the unlawful BIHE,” and “membership in the subversive Baha’i group with the intent to act against the national security” |

four years[114]

|

|

36 |

Ramin Zibaei |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a member of and educator for the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education for “membership in the unlawful BIHE,” and “membership in the subversive Baha’i group with the intent to act against the national security” |

four years)[115]

|

|

37 |

Riazollah Sobhani |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a member of and educator for the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education for “membership in the unlawful BIHE,” and “membership in the subversive Baha’i group with the intent to act against the national security” |

four years[116]

|

|

38 |

Kamran Mortezaei |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a member of and educator for the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education for “membership in the unlawful BIHE,” and “membership in the subversive Baha’i group with the intent to act against the national security” |

five years[117]

|

|

39 |

Shahin Negari |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a member of and educator for the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education for “membership in the unlawful BIHE,” and “membership in the subversive Baha’i group with the intent to act against the national security” |

four years[118]

|

|

40 |

Mahmoud Badavam |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a member of and educator for the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education for “membership in the unlawful BIHE,” and “membership in the subversive Baha’i group with the intent to act against the national security” |

four years[119]

|

|

41 |

Kamran Rahimian |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a member of and educator for the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education for “membership in the unlawful BIHE,” and “membership in the subversive Baha’i group with the intent to act against the national security” |

four years[120]

|

|

42 |

Keyvan Rahimian |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted as a member of and educator for the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education for “membership in the unlawful BIHE,” and “membership in the subversive Baha’i group with the intent to act against the national security” |

four years[121]

|

|

43 |

Aziz Samandari |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; Baha’i tried and convicted as a member of and educator for the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education for “membership in the subversive Baha’i group,” “providing technical support to the unlawful BIHE” |

five years[122]

|

|

44 |

Peyman Kashfi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted for “membership in a subversive group” (i.e. the Baha’i Faith) and “acting against the national security” |

four years[123]

|

|

45 |

Didar Raoufi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted for “membership in the Baha’i Faith” and “spreading Baha’i propaganda” |

three years[124] |

|

46 |

Adel Naeimi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted for “membership in the Baha’i Faith” and “spreading Baha’i propaganda” |

three years[125] |

|

47 |

Farhad Fahandej |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted for “organizing and running an illegal organization (related to the Baha’i Faith), “membership in an illegal organization (i.e. the Baha’i Faith),” “propaganda against the state” |

10 years[126]

|

|

48 |

Fouad Fahandej |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted for “organizing and running an illegal organization (related to the Baha’i Faith), “membership in an illegal organization (i.e. the Baha’i Faith)” |

five years[127]

|

|

49 |

Kourosh Ziari |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted for “organizing and running an illegal organization (related to the Baha’i Faith), “membership in an illegal organization (i.e. the Baha’i Faith)” |

five years[128]

|

|

50 |

Payam Markazi Baha’i |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; tried and convicted for “organizing and running an illegal organization (related to the Baha’i Faith), “membership in an illegal organization (i.e. the Baha’i Faith)” |

five years[129] |

|

51 |

Farahmand Sanaei |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted for “organizing and running an illegal organization (related to the Baha’i Faith), “membership in an illegal organization (i.e. the Baha’i Faith)” |

five years[130]

|

|

52 |

Siamak Sadri |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted for “organizing and running an illegal organization (related to the Baha’i Faith), “membership in an illegal organization (i.e. the Baha’i Faith)” |

five years[131]

|

|

53 |

Kamal Kashani |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; tried and convicted for “organizing and running an illegal organization (related to the Baha’i Faith), “membership in an illegal organization (i.e. the Baha’i Faith)”; |

five years[132]

|

|

54 |

Afshin Heyratian |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; child rights activist and Baha’i citizen tried and convicted |

four years[133] |

|

55 |

Fouad Khanjani |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i previously denied the right to university education and tried and convicted of “assembly and collusion against the national security” and “disturbing the public order” |

four years[134] |

|

56 |

Shahram Chinian |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted of “membership in an illegal organization (i.e. the Baha’i Faith),” “collaborating with anti-revolutionary groups (i.e. related to the Baha’i Faith), “insulting religious sanctities” |

eight years[135]

|

|

57 |

Fouad Moghadam |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted of “assembly and collusion against the national security” |

five years[136]

|

|

58 |

Amanollah Mostaghim |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted for “membership in an illegal organization” (i.e. related to the BIHE and the Baha’i Faith) |

five years[137]

|

|

59 |

Ighan Shahidi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i previously denied the right to university education and tried and convicted of “membership in the illegal Council to Defend the Right to Education,” “propaganda against the state,” and “membership in an illegal organization” (i.e. the Baha’i Faith) |

five years[138]

|

|

60 |

Shahrokh Taef |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted of “membership in an illegal organization” (i.e. the Baha’i Faith) |

four years[139]

|

|

61 |

Sarang Ettehadi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tried and convicted of a Baha’i tried and convicted of “propaganda against the system” and “membership in an illegal organization” (i.e. the Baha’i Faith) |

one year[140]

|

|

62 |

Shamim Naeimi |

Held in Rajai Shahr prison; a Baha’i tired and convicted of “membership in an illegal organization” (i.e. Baha’i Faith) |

three years[141] |

|

63 |

Reza Rabbani |

Held in Central Prison at Karaj; a Christian convert in pretrial detention)[142] |

|

III. Due Process Concerns in Other Cases of

Concern at Prisons in Karaj

In addition to the political prisoners Human Rights Watch has identified, Human Rights Watch has concerns about possible due process violations in the cases of 126 other detainees in Karaj prisons who have been active in political or religious opposition groups or otherwise charged with national security crimes. The prisoners are being held in Ghezel Hesar prison, Rooms 10 and 12 of Ward 4 of Rajai Shahr prison, and the Central Prison at Karaj. The authorities allege that many of these persons are affiliated with political or religious groups engaged in disrupting the country’s national security, or have been involved in violent or terrorist activities.

Ghezel Hesar prison is approximately eight kilometers southwest of Rajai Shahr in the city of Karaj. It is considered one of the largest prisons in the Middle East. The overwhelming majority of prisoners held in this detention facility are believed to have been convicted by courts on drug trafficking charges. Human Rights Watch is aware of only two individuals convicted of national security charges (and sentenced to death) who are currently being held at this facility. According to some estimates, Ghezel Hesar prison may hold as many as 15,000 prisoners, making it one of the largest prisons in the Middle East.

Human Rights Watch was not able to gather enough information to determine whether these individuals actually participated in violence, but the circumstances of their arrest, detention, and prosecution suggest that they may be victims of due process violations, and raises questions regarding whether they are being targeted for their peaceful exercise of fundamental rights such as freedom of expression and association. Human Rights Watch and other organizations have documented due process violations in similar cases in the past.[143]

On May 29, 2014, Human Rights Watch forwarded the list of names of 120 prisoners held in Rajai Shahr and Ghezel Hesar prisons to the Iranian authorities and asked them to provide a) the charges under which they have been convicted, b) their sentence, c) the evidence used to convict them in revolutionary courts, d) whether they or their lawyers ever challenged the convictions by alleging serious due process violations, including secret hearings, lack of access to a lawyer, long periods of incommunicado and solitary confinement, and allegations of ill-treatment, torture, and coerced confessions, and e) whether the judiciary has ever investigated allegations of serious due process violations in these cases.[144]

Thirty-five of the names included in this list were of individuals sentenced to death by revolutionary courts and at imminent risk of execution. Human Rights Watch asked the authorities to provide further information on these individuals, and has since, along with several other rights groups, asked the authorities to stop their execution.[145]

To date Human Rights Watch has not received any responses to its requests.

Zaniar Moradi © 2014 Private

Twenty-two of the 126 prisoners belong to political opposition parties such as the Mojahedin-e Khalq and several leftist Kurdish parties, including the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran and Komala, according to information gathered by Human Rights Watch.[146]

Loghman Moradi © 2014 Private

These detainees are being held in Room 12 of Ward 4 of Rajai Shahr prison. In 2010 officials convicted two of them, Kurdish activists Loghman and Zaniar Moradi, who are cousins, of “enmity against God” and “corruption on earth,” according to a source familiar with their case.[147]

The two were convicted for their membership in the banned Komala party, which advocates Kurdish autonomy, and for their alleged involvement in the killing of the son of a Sunni Muslim cleric in the western city of Marivan the source said. They deny any involvement in the killing, and say that during the initial phase of their pretrial detention, Intelligence Ministry agents accused them only of connection to Komala, not with killing the cleric’s son.[148]

Over several months, Intelligence Ministry agents in the northwestern city of Sanandaj severely tortured them during interrogation, the source said, including with threats of sexual assault, apparently to pressure them to turn in one of the cousin’s fathers, whom the men said the government has targeted for years, and who is currently in Iraqi Kurdistan. When the two men refused to cooperate, the judiciary eventually indicted the two men on murder charges as well as with cooperating with Komala.[149]

During the cousins’ trial, which took place in Branch 28 of the Revolutionary Court in Tehran and lasted approximately 20 minutes, the judge informed the defendants that officials had charged them with assassinating the son of the Sunni cleric, sentenced them to death, and prevented them or their court-appointed lawyer from providing a defense, according to the source familiar with the case. The source also said that Zaniar and Loghman complained to the authorities of torture during pretrial detention, which they said forced their confessions, but that no one responded to their complaint. Human Rights Watch has reviewed a letter the two wrote in 2012 in which they vividly describe the ill-treatment and torture which included beatings and threats of sexual violence they were subjected to.[150]

Officials are also holding three other Kurdish activists in Ward 4, Room 12 of Rajai Shahr prison, three of whom were convicted for their alleged ties to the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran according a source familiar with their cases. Authorities are holding another 16 prisoners in Ward 4, Room 12 for their alleged ties to the banned Mojahedin-e Khalq organization (MEK), and at least 13 others on various espionage or spying-related charges on behalf of foreign governments or opposition groups.[151]

Human Rights Watch has also acquired a list of names of 86 other prisoners held in Ward 4, Room 10 of Rajai Shahr prison, and two others held in Ghezel Hesar prison, detained on various national security-related charges including terrorism-related ones. Little is known about the activities or the circumstances of the arrests and convictions of these individuals, but many faced trial in revolutionary courts after weeks, if not months, at Intelligence Ministry detention facilities located in Iran’s Kurdish-majority areas.[152] They are believed to have been tortured or otherwise ill-treated during that time.[153]

Many of the prisoners held in this room describe themselves as Sunni activists or “missionaries” who support a strict, literalist interpretation of Sunni Islam, a source familiar with these cases told Human Rights Watch. Most are from Iran’s Kurdish or Baluch communities but some are citizens of foreign countries, according to the same source. The authorities, however, allege that some were involved in armed activities, including assassinations and murder, while others either assisted these groups or endangered the country’s national security by other means.[154]

The source familiar with these cases told Human Rights Watch that in December 11, 2011, prison officials transferred these prisoners from Ward 4, Room 102, to Room 10 of the prison at the request of a few prisoners affiliated with leftist-secular Kurdish parties such as Komala and PJAK. [155] The prisoners now held in Room 10 have restricted access to family visits, telephone privileges, and medical care , according to the former prisoner and others. [156]

The judiciary has issued death sentences for at least 33 of these prisoners and they are at imminent risk of execution. Human Rights Watch believes most of the men were arrested by Intelligence Ministry officials in the western province of Kordestan in 2009 and 2010, and held in solitary confinement during their pretrial detention for several months without access to a lawyer or relatives. Thirty one of them were tried by Branch 28 of the Revolutionary Court of Tehran, while one was tried by Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court of Tehran and another by a branch of the Revolutionary Court of Sanandaj.[157]

They were sentenced to death after being convicted of vaguely worded national security offenses including “gathering and colluding against national security,” “spreading propaganda against the system,” “membership in Salafist groups," “corruption on earth,” and “enmity against God.” The latter two charges can carry the death penalty.[158]

According to his national identity card, at least one of the defendants, Borzan Nasrollahzadeh, is believed to have been under 18 at the time of his alleged offense, which would prohibit his execution under international law, including under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which Iran is a party.[159]

Rajai Shahr prison © 2014 Private

Several sources familiar with the cases of six of these prisoners— Hamed Ahmadi, Jamshid Dehghani, Jahangir Dehghani, Kamal Molaei, Sedigh Mohammadi, and Seyed Hadi Hosseini— told Human Rights Watch that all six deny that they killed anyone or had any involvement in violent acts. The men allege severe torture, including the use of electric shocks and threats of sexual assault, prolonged solitary confinement, and coerced confessions at the hands of Intelligence Ministry officials during their pretrial detention in the city of Sanandaj in Kurdistan Province.[160]

Ahmadi, Jahangir Dehghani, Jamshid Dehghani and Molaei are accused of killing Mullah Mohammad Sheikh al-Islam, a senior Sunni cleric with ties to the Iranian authorities. They have denied the accusation, saying that they were arrested between June and July 2009, several months before the sheikh’s killing, in September.[161] Their trial took place in Branch 28 of Tehran’s Revolutionary Court and took no longer than 10 minutes, during which they were not allowed to offer a defense.[162] The Supreme Court upheld their death sentences in September 2013, and the sentences have been sent to the Office for the Implementation of Sentences, the official body in charge of carrying out executions. The men are considered to be at imminent risk of execution.[163]

Before appearing before the judge none of the six knew that they had been charged with “enmity against God” or that they could receive death sentences.[164]

As of June 2014, the Supreme Court also confirmed the death sentences of four other members of the group—Seyed Jamal Mousavi, Abdorahman Sangani, Sedigh Mohammadi and Seyed Hadi Hosseini. The other 25 men remain on death row pending review by the Supreme Court.[165]

The names of the 126 prisoners discussed in this chapter and identified in Human Rights Watch’s letter to the Iranian authorities are:

- 1. Varia Ghaderifard

- 2. Ahmad Nasiri

- 3. Kamal Molaei

- 4. Hamed Ahmadi

- 5. Abdolrahman Sangani

- 6. Mohammad Gharibi

- 7. Jamshid Dehghani

- 8. Jahangir Dehghani

- 9. Pourya Mohammadi

- 10. Farzad Shahnazari

- 11. Mohammad-Yavar Rahimi

- 12. Alem Barmashti

- 13. Bahman Rahimi

- 14. Edris Nemati

- 15. Barzan Nasrollazadeh

- 16. Keyvan Momenifard

- 17. Teymour Naderizadeh

- 18. Farzad Honarjou

- 19. Farshid Naseri

- 20. Shahoo Ebrahimi

- 21. Omid Peyvand

- 22. Amjad Salehi

- 23. Omid Mahmoudi

- 24. Mohammad-Keyvan Karimi

- 25. Varia Amiri

- 26. Borhan Asgharian

- 27. Hossein Amini

- 28. Esmaeil Atashmard

- 29. Ghasem Abasteh

- 30. Abdolsalam Agnesh

- 31. Jabar Beydkham

- 32. Mohammad Amin Barghi

- 33. Khosro Besharat

- 34. Firouz Hamidi

- 35. Yadollah Habibi

- 36. Jabar Hasani

- 37. Khaled Hajizadeh

- 38. Maaz Hakimi

- 39. Anwar Khezri

- 40. Ramin Zahedi

- 41. Jamal Soleimani

- 42. Farhad Salimi

- 43. Mohammad-Zaman Shahbaksh

- 44. Kamran Sheykheh

- 45. Hasan Shoveylan

- 46. Mohammadyaser Sharafipour

- 47. Keykhosro Sharafipour

- 48. Vahed Sharafipour

- 49. Abdollah Shariati

- 50. Parviz Osmani

- 51. Shouresh Alimoradi

- 52. Davoud Abdollahi

- 53. Kambiz Abbasi

- 54. Jamal Ghaderi

- 55. Ramin Karami

- 56. Ali Karami

- 57. Ayoub Karimi

- 58. Kamran Mamhosseini

- 59. Erfan Naderizadeh

- 60. Fouad Yousefi

- 61. Souran Alipour

- 62. Fouad Rezazadeh

- 63. Hossein Alizadeh

- 64. Hossein Javadi

- 65. Kaveh Veisi

- 66. Kaveh Sharifi

- 67. Arash Sharifi

- 68. Mokhtar Rahimi

- 69. Shahram Ahmadi

- 70. Behrouz Shahnazari

- 71. Taleb Maleki

- 72. Zaniar Moradi

- 73. Loghman Moradi

- 74. Omar Faghihpour

- 75. Khaled Fereydouni

- 76. Mohammad Nazari

- 77. Saleh Kohandel

- 78. Saeed Masouri

- 79. Hasan Ashtiani

- 80. Aref Pishehvar

- 81. Afshin Baymani

- 82. Mohammad Ali (Pirouz)Mansouri

- 83. Misagh Yazdannejad

- 84. Mohammad Banazadeh Amirkhizi

- 85. Khaled Hordani

- 86. Farhang Pourmansouri

- 87. Shahram Pourmansouri

- 88. Karim Marouf Aziz

- 89. Seifollah Segani

- 90.Hasan Tafah

- 91.Batir Shahmodof

- 92.Ali Moezzi

- 93.Seyed Hadi Hosseini

- 94.Sedigh Mohammadi

- 95.Mehdi Mohammadi

- 96.Heyman Darvish

- 97.Ali Mafakheri

- 98. Fakhreddin Aziz

- 99. Asadollah Hadi

- 100. Asghar Ghatan

- 101. Majid Asadi

- 102. Mashallah Haeri

- 103. Reza Akbari Monfared

- 104. Javad Fouladvand

- 105. Ali Salanpour

- 106. Gholamhossein Asadi

- 107. [Name Withheld]

- 108. [Name Withheld]

- 109. [Name Withheld]

- 110. [Name Withheld]

- 111. [Name Withheld]

- 112. [Name Withheld]

- 113. [Name Withheld]

- 114. [Name Withheld]

- 115. [Name Withheld]

- 116. [Name Withheld]

- 117. [Name Withheld]

- 118. [Name Withheld]

- 119. [Name Withheld]

- 120. [Name Withheld]

- 121. [Name Withheld]

- 122. [Name Withheld]

- 123. [Name Withheld]

- 124. [Name Withheld]

- 125. [Name Withheld]

- 126. [Name Withheld]

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Faraz Sanei, researcher for the Middle East and North Africa division of Human Rights Watch, with extensive research conducted by a research assistant.

Robin Shulman, consultant to the Middle East and North Africa division, Clive Baldwin, senior legal advisor at Human Rights Watch, and Tom Porteous, deputy program director, reviewed this report.

Sandy Elkhoury, associate in the Middle East and North Africa division, provided production assistance. Nadia Riazati provided additional research assistance and translation (from English to Persian). Publications Specialist Kathy Mills, and Administrative Manager Fitzroy Hepkins prepared the report for publication.

Human Rights Watch sincerely thanks all the individuals who shared their knowledge and experiences to make this report possible, sometimes at personal risk.

Appendix I

May 29, 2014

His Excellency Ayatollah Sadegh Larijani

Head of the Judiciary

Islamic Republic of Iran

His Excellency Mohmmad Javad Larijani

Head of the Judiciary’s High Council for Human Rights

Islamic Republic of Iran

Your Excellencies: