“We Are Also Dying of AIDS”

Barriers to HIV Services and Treatment for Persons with Disabilities in Zambia

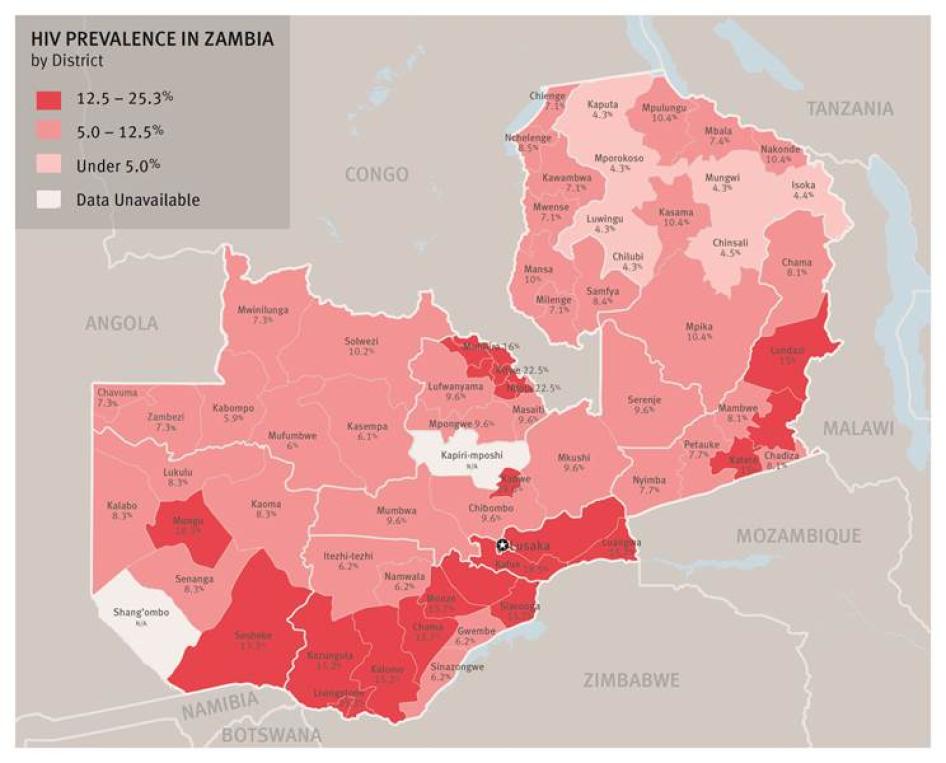

Map of Zambia

Human Rights Watch conducted field research in the highest prevalence districts in Southern, Copperbelt and Lusaka provinces. SOURCE: Zambia HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Projections Report 1985-2010 (Central Statistical office).

Glossary

|

Cerebral palsy |

An impairment of muscular function and weakness of the limbs caused by lack of oxygen to the brain immediately after birth, brain injury during birth, or a viral infection. Often accompanied by poor motor skills, it sometimes involves speech and learning difficulties.[1] |

|

Developmental disability |

An umbrella term that refers to any disability starting before the age of 22 and continuing indefinitely (i.e. that will likely be life-long).[2] It limits one or more major life activities such as self-care, language, learning, mobility, self-direction, independent living, or economic self-sufficiency.[3] While this includes intellectual disabilities such as Down syndrome, it also includes conditions that do not necessarily have a cognitive impairment component, such as cerebral palsy, autism, and epilepsy and other seizure disorders. Some developmental disabilities are purely physical, such as sensory impairments or congenital physical disabilities. It may also be the result of multiple disabilities. While autism is often conflated with learning disabilities, it is actually a developmental disability. |

|

Disabled persons’ organizations (DPOs) |

These are formal groups of people who are living with disabilities and who work to promote self-representation, participation, equality and integration of all people with disabilities. |

|

Intellectual disability |

An “intellectual disability” (such as Down Syndrome) is characterized by significant limitations both in intellectual functioning (reasoning, learning, problem solving) and in adaptive behavior, which covers a range of everyday social and practical skills. “Intellectual disability” forms a subset within the larger universe of “developmental disability,” but the boundaries are often blurred as many individuals fall into both categories to differing degrees and for different reasons. |

|

Psychosocial disability |

The preferred term to describe persons with mental health problems such as depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Psychosocial disability relates to the interaction between psychological differences and social/cultural limits for behavior, as well as the stigma that society attaches to persons with mental impairments.[4] |

Summary

When you go for VCT [voluntary HIV counseling and testing], you are looked up and down, people say, “Why should you be in the line? Who could give you HIV?” They don’t expect disabled women to be sexually active.

—Yvone L., a Zambian woman with a physical disability, Lusaka,

November 2013

The problem is that deaf people have no detailed information on AIDS. We can go to the hospital but there is no sign language...The deaf do not know about adherence to medication and it can be a killer.

—Franklyn C., a Zambian man who is deaf and has received training to be a counselor for HIV testing and counseling, Kitwe, January 2014

There has been significant progress around the world in recent years toward providing universal access to HIV prevention, treatment, care and support programs. However, as the United Nations has acknowledged, such progress has excluded people with disabilities because of the lack of adequately targeted and accessible services for such persons.

The global epicenter of the HIV pandemic remains in eastern and southern Africa. Half of all new HIV infections occur in these regions annually, and they are home to 17 million people living with HIV. It is increasingly recognized that persons with disabilities are often more vulnerable to HIV infection than anyone else because of their lower education and literacy levels, higher poverty, and greater risks of physical and sexual violence.

Zambia has made important progress in scaling-up HIV prevention and treatment services over the past decade. However, more than 1 in 10 adults in Zambia are living with HIV, and 46 thousand adults and more than 9,000 children are infected with HIV every year. There are nearly two million persons with disabilities in Zambia, and like any other Zambian, they face a high risk of HIV infection. Yet, adults and children with disabilities have been systematically left behind in the national HIV response, with limited access to HIV prevention information and significant barriers to HIV testing and treatment.

This report examines the barriers faced by persons with physical, sensory, psychosocial and intellectual disabilities in accessing HIV services, including HIV prevention education and information, condoms, testing, treatment and long-term support for adherence. It also examines the exposure of persons with disabilities to significant risk factors for HIV.

We found that persons with disabilities face several key barriers to HIV services, and hence to realizing their right to the highest attainable standard of health. While some of these are the same for all people living with HIV, and not only for persons with disabilities, other barriers disproportionately limit or uniquely affect persons with disabilities. Key barriers include: 1) pervasive stigma and discrimination both in the community and by healthcare workers; 2) lack of access to inclusive HIV prevention education and information in schools, community settings, and through mass media; 3) obstacles to accessing voluntary testing and HIV treatment services; and 4) lack of appropriate support for adherence to antiretroviral treatment (ART).

1. Pervasive Stigma and Discrimination

In Zambia, disability is often considered a curse or punishment caused by evil spirits or as a result of witchcraft, for example in response to the actions of family members. Taboos regarding their sexuality result in a lack of respect for the sexual and reproductive rights of persons with disabilities. Individuals with different disabilities told Human Rights Watch that they are often viewed as being asexual and are confronted with negative attitudes about their right to marry and have children. As a result, persons with disabilities sometimes do not have access to HIV prevention, testing, or treatment services.

All persons living with HIV experience stigma and discrimination. However, persons with disabilities face “double” stigma because of their disabilities and HIV status, perpetuating their social isolation, hampering the linkage and adherence to treatment, and limiting their ability to form intimate relationships. This increased stigma further inhibits disclosure of their positive status in the community and even within their family and circle of peers.

2. Lack of Access to Inclusive HIV Prevention Education and Information

Children with disabilities are unable to access HIV prevention information on an equal basis with other children because of lack of access to education in general. Discrimination within the family, admission barriers and lack of physical accessibility keep many children with disabilities out of school where they might receive HIV prevention information. Even when children are able to attend school, children with disabilities are often excluded from programs providing HIV information, or cannot access inclusive materials.

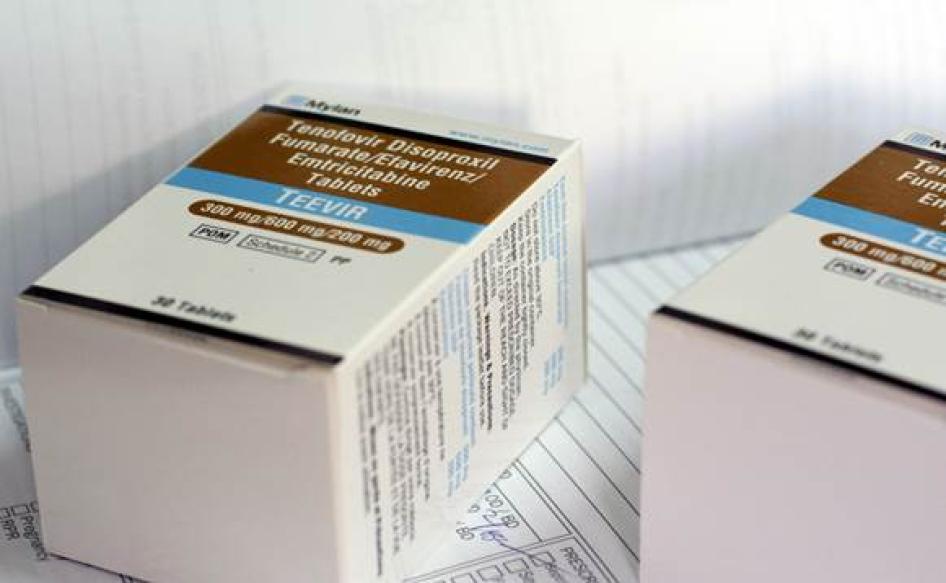

Antiretroviral drugs, like those pictured here, often do not have Braille symbols, making it difficult for blind people to identify various medications. © 2014 Justin Purefoy for Human Rights Watch

Similarly, adults with disabilities often cannot access general HIV information disseminated through print and mass media because of the lack of materials produced in simplified formats, braille, large print, or with sign language symbols. Persons with sensory or physical disabilities experience difficulties in accessing and using condoms due to the lack of accessible information and peer education. Community-based sensitization activities often exclude persons with disabilities due to physical and communication barriers and social isolation. Human Rights Watch found high rates of sexual and intimate partner violence among women and girls with disabilities, which increases their risk for HIV infection. The vulnerability of women and girls with disabilities is compounded because they lack equal access to information about gender-based violence, HIV prevention and social protection services.

Dominic Vwalya (left), who is blind and living with HIV, is accompanied here by a volunteer health worker to a local health center in Lusaka. © 2014 Justin Purefoy for Human Rights Watch

3. Barriers to Voluntary HIV Testing and HIV Treatment Services

Persons with disabilities told Human Rights Watch about the lack of effective pre- and post- HIV testing counseling because of inadequate training of healthcare workers on how to communicate with and address the concerns of people with disabilities. Persons with disabilities, in particular those who are deaf or blind, reported that healthcare workers do not adequately elicit personal health information, undertake diagnosis, prescribe medication, and counsel people with disabilities when they visit health facilities for antiretroviral treatment or in relation to opportunistic infections.

Persons with disabilities often experience a lack of confidentiality in HIV testing because of communication barriers and the need to involve a third person for interpretation. Representatives of the national organization of persons with psychosocial disabilities told Human Rights Watch that some individuals with psychosocial disabilities in mental health units in general hospitals are not ensured of their free and informed consent for HIV testing. Health workers and medical staff from three mental health units interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported varying application of HIV testing consent procedures in healthcare settings as well as confusion concerning the testing policy.

4. Lack of Appropriate Support for Treatment Adherence

Persons with disabilities who are receiving antiretroviral treatment often depend on the availability of a family member or friend for mobility or communication assistance to keep up with scheduled appointments. When this support is not available, however, accommodations are rarely made for their circumstances, such as re-scheduling appointments or providing a longer supply of medicine to individuals. Instead, healthcare workers label persons with disabilities as “defaulters,” requiring them to have more frequent appointments and limiting their supply of medicine as a consequence of missing an appointment.

* * *

These barriers deny persons with disabilities their right to health and other rights affected by one’s well-being, such as to work, to privacy and to freedom of movement. Zambia has ratified a number of international and regional human rights treaties including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which obligates governments to provide persons with disabilities the same range, quality and standard of free or affordable health care and programs as provided to other persons, including population-based public health programs. This means that persons with disabilities should be able to access HIV services on an equal basis with others.

In line with the CRPD, Zambia’s 2012 Persons with Disabilities Act directs the government to provide equal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare and public health programs. The 2012 draft Constitution guarantees persons with disabilities enjoyment of all the rights and freedoms in the Bill of Rights on the basis of accessibility and non-discrimination. In addition, the Zambian government has recognized persons with disabilities as a vulnerable population at risk for HIV; yet, it has not implemented specific interventions and strategies to provide inclusive HIV services for persons with disabilities.

International donors and United Nations agencies said that they were aware of the lack of inclusive and targeted HIV services for persons with disabilities in Zambia, and admitted that they had not done enough to ensure that funding for HIV services is allocated without discrimination and equitably benefits persons with disabilities who are just as if not more vulnerable to HIV.

The Zambian government should protect the fundamental rights of persons with disabilities by fully implementing the 2012 Persons with Disabilities Act. The African Union has called on member states to develop preventive and curative HIV services for the most vulnerable groups, including persons with disabilities. Zambia should take all appropriate steps to eliminate the pervasive stigma and discrimination persons with disabilities face in accessing HIV services and provide inclusive and targeted HIV prevention, testing and treatment services for persons with different disabilities.

As a regional leader in developing and expanding comprehensive HIV services, Zambia could become a model for inclusion of persons with disabilities. However, Zambia cannot achieve its goal of universal and equitable access to HIV prevention, treatment and care, if it leaves behind persons with disabilities in its national HIV response.

One of those being left behind is Daniel L., a shy but determined 13-year-old who is deaf and HIV-positive. He lost both his parents to HIV and has experienced stigma and neglect from his own family, who failed to enroll him in HIV treatment for some time, because they considered him to be doubly cursed and a burden. He told Human Rights Watch that he cannot talk to anyone about living with HIV and taking antiretroviral medicine as a deaf adolescent: “No one at the clinic or at home can sign with me. I can’t tell them [school friends] because I don’t want them to insult me.” Daniel becomes worried about his future but as he told Human Rights Watch, “I will fight to survive.”[5]

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Zambia and the National Assembly

To the National AIDS Council, Ministry of Gender and Child Development, Ministry of Community Development, Mother and Child Health, and the Ministry of Health

- Implement targeted disability-specific HIV services as well as ensure accessibility of existing mainstream HIV services to persons with different disabilities.

- Make hospitals and health centers accessible for persons with disabilities including through ramps, accessible examination and counseling rooms and toilets, and the availability of sign language interpreters.

- Develop a code of ethics for HIV testing, diagnosis and counseling services for persons with disabilities and provide training on it to health workers providing HIV services. Train all health workers on the rights of persons with disabilities, including their right to sexual and reproductive health.

- Ensure that HIV testing, treatment, care and support services adhere fully to ethical principles of confidentiality and the need for free and informed consent.

- Strengthen home-based care, peer services and mobile clinics for HIV service delivery to persons with disabilities.

- Ensure inclusive and targeted programs to prevent sexual violence against women and girls with disabilities and to provide treatment and support services for survivors.

To the Zambia Agency for Persons with Disabilities

- Develop and implement initiatives to combat stigma and discrimination against persons with disabilities in all areas of life, including in the area of public health.

To the Ministry of Community Development, Mother and Child Health, the Ministry of Health, and the Central Statistics Office

- Support research on HIV risk factors and prevalence among persons with disabilities, either through existing national surveys (such as the Demographic and Health Survey, Sexual Behavior Survey and Antenatal Care Surveillance Survey) or through targeted research. Ensure that the information can be disaggregated by type of disability, age and gender.

To UN Agencies, Donor Agencies working on HIV/AIDS, Donor Countries, and the Global Fund

- Assist the government of Zambia, through technical and financial support, with the design and implementation of inclusive HIV programming within each stage of the HIV continuum of prevention and care for persons with disabilities.

Methodology

Field research for this report was carried out in Zambia in November 2013 and January-February 2014 across the provinces of Lusaka, Southern and Copperbelt. These regions were selected because they are geographically diverse and they have the highest number of adults and children living with HIV in the country. Within each province, we focused on urban and peri-urban districts.

The report is based on 205 in-depth interviews with 64 individuals with disabilities, 15 parents of children with disabilities, 9 special education teachers as well as 117 nongovernmental organization (NGO) representatives, government officials, healthcare workers, and other individuals.

Of the 52 adults and 12 children with disabilities[6] interviewed, 27 had physical disabilities, 12 were deaf, 9 were blind or had low vision, 2 had intellectual disabilities, 11 had psychosocial disabilities and 3 had multiple disabilities. Of these, 29 self-reported as living with HIV. Of those who self-reported as HIV-positive, some reported a pre-existing disability while others acquired their disability as a result of HIV.

Interviews were facilitated by NGOs providing community health services to adults and children living with HIV as well as disabled people’s organizations (DPOs), organizations providing HIV services, and disability rights activists. Human Rights Watch also met with field staff from government bodies, namely the Zambia Agency for Persons with Disability (ZAPD) and the Ministry of Community Development, Mother and Child Health. Because of these referrals, we expect that the individuals we spoke with were more likely to be linked to HIV and general social services, compared to individuals with disabilities not known by these organizations.

Interviews covered a range of topics related to the experiences of persons with disabilities in accessing HIV prevention, testing services and treatment. Conducting interviews on HIV poses a number of methodological and ethical challenges. We took great care to interview adults and children in a friendly and sensitive manner, and ensured that the interview took place in a private setting. Interviews were conducted mainly at interviewees’ homes or at NGO premises in locations where the interviewee’s privacy was protected. Information about the HIV status of the adults and children interviewed was kept strictly confidential.

Before each interview, Human Rights Watch informed interviewees of its purpose, the kinds of issues that would be covered, and how the information would be used. We then asked if they wanted to participate. We informed them that they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any specific question, without consequence. Interviews with adults and children with disabilities and their families were carried out in English, Bemba, Nyanja, Lozi, Tonga and sign language with consecutive interpretation as needed.

Interviewees did not receive any material compensation. Unless otherwise noted, we have disguised the identities of all interviewees in this report to protect their privacy. The identities of a number of other interviewees including some government personnel have also been withheld at their request.

With permission from the Ministry of Community Development and Mother and Child Health, Human Rights Watch visited seven primary healthcare sites, two mobile clinics and five tertiary hospitals. We also visited two children’s homes for orphaned and vulnerable children affected by HIV, four government education facilities with special education units for children with disabilities, and two Victim Support Units (VSUs) at local police stations.

We conducted interviews with 41 healthcare workers including eight voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) and ART counselors, eight nurses, seven doctors, five clinical officers, two psychologists and five home healthcare workers. These interviews concerned their experiences in providing HIV services to persons with disabilities. We also sought their opinion on measures that could be taken to improve access to HIV services by persons with disabilities.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 18 local and national government officials from the Ministry of Community Development, Mother and Child Health, Ministry of Education, Science, Vocational Training and Early Education, Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Justice, the National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council and the Zambia Agency for Persons with Disabilities; and 33 representatives of local NGOs, organizations providing HIV services including faith-based organizations, international NGOs, and United Nations agencies.

Human Rights Watch consulted with international disability rights experts at various stages of the research and writing and reviewed a number of official documents from the Zambian government, as well as relevant reports from donors, UN agencies and NGOs.

In May 2014, Human Rights Watch presented preliminary findings to the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Community Development, Mother and Child Health, the Ministry of Education, Science, Vocational Training and Early Education, the Ministry of Gender and Child Development, the Ministry of Justice, the Zambia Agency for Persons with Disabilities, and the National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council.

I. Background

HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Zambia [7]

Globally, approximately 35.3 million people are living with HIV.[8] Eastern and southern Africa remain the epicenter of the pandemic, with 48 percent of the world’s new HIV infections and 17.1 million of all those with HIV living in these regions.[9] Zambia has a generalized HIV epidemic—that is, an epidemic that affects all segments of society. In 2012, the prevalence of HIV in Zambia was about 12.7 percent within the 15 to 49 age group, with more than 700,000 adults and children estimated to be living with HIV.[10]

In 2004, the Zambian government introduced free access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the public health sector. In June 2005, the government declared the ART service package (including counseling, x-rays, and CD4 testing[11]) free of charge.[12]

Zambia has made significant investment and progress in scaling-up HIV prevention and treatment services over the past decade. The number of HIV counseling and testing sites has increased from 56 in 2001 to 1,800 in 2012[13] and the number of health facilities providing ART services (in both the private and public sectors) has increased from 107 in 2005 to 564 in 2013.[14] Between 2005 and 2013, the number of adults and children on ART increased from 57,164 to 580,118, representing an increase from 23.5 percent treatment coverage for those needing ART to 81.9 percent.[15]

However, the Zambian government has acknowledged that it faces a number of challenges in ensuring universal access and utilization of HIV services – including an “inadequate focus on vulnerable populations.” [16] In 2008, the Kampala Declaration, adopted by the African Campaign on Disability and HIV & AIDS, called on African governments to ensure that “National AIDS strategic plans recognize persons with disabilities as vulnerable to the impact of HIV and AIDS” and provide inclusive services. [17]

Zambia’s 2012 Persons with Disabilities Act mandates the government to “provide persons with disabilities with the same range, quality and standard of free or affordable health care as provided to other persons, including in the area of sexual and reproductive health and population based public health programmes.” [18] The draft 2012 National Disability Policy states that “people with disabilities have similar sexual desires as the non-disabled and are equally affected by the pandemic.” [19] Furthermore, the Zambian government recognized persons with disabilities as a “vulnerable population” in its third National AIDS Strategic Framework (NASF 2011-2015). [20]

Persons with Disabilities in Zambia

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than one billion people worldwide – 15 percent of the world’s population - live with physical, sensory (deafness, blindness), intellectual or psychosocial disabilities, or a combination of these.[21]

There is limited data on people with disabilities in Zambia, including how many adults and children are living with disabilities and their specific housing, education, and healthcare needs. There is wide disparity in the available statistics, from 2.0 percent in the 2010 National Census[22] to 13.3 percent, based on a 2006 national representative survey of living conditions among people with disabilities conducted by the Zambia Federation of Disability Organizations (ZAFOD), in collaboration with SINTEF Health Research and other partners.[23] WHO has previously estimated that 15.3 percent of the population in African countries has a significant or moderate disability.[24]

The 2010 census reported 251,427 persons with disabilities in Zambia, including 66,043 children and young people in the 5 to 19 year age group.[25] However, national educational data indicates that this number likely underestimates the number of people with disabilities. In comparison to the census data, the Ministry of Education reported that 198,394 children with special learning needs (comprising children with hearing, physical, intellectual, visual, specific learning and other disabilities) were enrolled in Grades 1-9 in basic schools in 2010.[26]

The prevalence of disability is likely higher than the government figures indicate due to social factors that isolate people with disabilities and the limitations in data collection. Because of fear and shame, and traditional beliefs that disability is associated with misfortune in the family caused by witchcraft,[27] many adults and children with disabilities remain hidden in their homes away from the public and may not be included in any data on persons with disabilities.

Furthermore, while the government expanded the number of disability categories in the 2010 census,[28] data on disability was collected through a dichotomous (yes/no) response to questions about the existence of a disability, rather than an approach that captured “variations in the intensity of the disabilities.”[29] Such an approach would likely understate the prevalence by capturing only the most severe forms of disability. Using the SINTEF estimate of 13.3 percent prevalence (based on capturing disability across a spectrum of degrees of severity), there would be approximately 1.9 million persons with disabilities in Zambia.[30]

There is no internationally accepted definition of disability. The 2006 Convention on the

Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), a landmark treaty so far ratified by 147 countries including Zambia, describes persons with disabilities as including those “who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”[31] Zambia’s Persons with Disabilities Act defines disability as a “permanent” impairment resulting from the interaction between health conditions and external contextual factors.[32] However, by requiring the existence of a “permanent” condition, it is narrower than the CRPD, which does not exclude temporal impairment in its scope.

According to Zambia’s 2010 Census, physical and sensory disabilities were the most common type of disability in the country, with 43.6 percent of persons with disabilities reporting some sensory impairment (partially sighted, blind, deaf, hard of hearing). A total of 32.7 percent had a physical disability, 6.8 percent reported a psychosocial disability, and 4.7 percent had an intellectual or learning disability.[33]

Vulnerability of Persons with Disabilities to HIV

Internationally, growing evidence indicates that people with disabilities have greater exposure to all of the risk factors[34] for HIV including lower education and literacy levels, poverty, and risk of physical and sexual violence, and hence may be disproportionately affected by HIV.[35] In Zambia the limited data on persons with disabilities also suggests that they are more vulnerable to the risk factors for HIV.[36]

Persons with disabilities in Zambia have limited access to education and a low level of literacy. The 2010 Census indicated a literacy rate of 58.6 percent among persons with disabilities in comparison to 70.4 percent for persons without disability.[37] According to the census, 34.4 percent of persons with disabilities had never attended school, in comparison to 20.9 percent of persons without disabilities.[38]

In Zambia and in many other countries, disability and poverty are inextricably linked.[39] Worldwide, as many as 50 percent of disabilities, are directly linked to poverty.[40] Poverty can lead to disability through malnourishment, lack of access to health services, poor sanitation, or unsafe living and working conditions.[41] In turn, having a disability can “entrap a person in poverty by limiting their access to education, employment, public services and even marriage.”[42] In Zambia, more than 60 percent of the population lives below the poverty line with more than 40 percent living in extreme poverty.[43] Persons with disabilities are disproportionately affected by poverty. In its survey on living conditions among people with disabilities in Zambia, SINTEF found that 57.2 percent of people with disabilities aged 15 years and over had never been employed.[44]

National data indicates that women in Zambia face multiple forms of discrimination and abuses including gender-based violence, adding another risk factor for HIV.[45] International research also indicates that women with disabilities are likely to be disproportionately affected by violence.[46] According to the 2004 Global Survey on HIV/AIDS and Disability, “individuals with disability are up to three times more likely to be victims of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and rape.”[47] A 2010 survey of children and young adults with disabilities found high levels of physical and sexual violence against children and young people with disabilities in Zambia.[48]

These risk factors indicate that persons with disabilities are likely to be more vulnerable to HIV infection. While there is little data on how people with disabilities are affected by HIV, emerging data from the region and internationally indicates that there is at least an equal, if not greater rate of HIV prevalence among people with disabilities.[49] In Zambia, preliminary studies also indicate that persons with disabilities are just as if not more vulnerable to HIV infection.[50]

II. Barriers to HIV Services and Poor Quality of Care

“I’m a human being who has feelings…People say how did you become positive? They should understand that HIV does not spare the disabled.”

—Dominic Vwalya, a blind pastor from Lusaka, November 2013

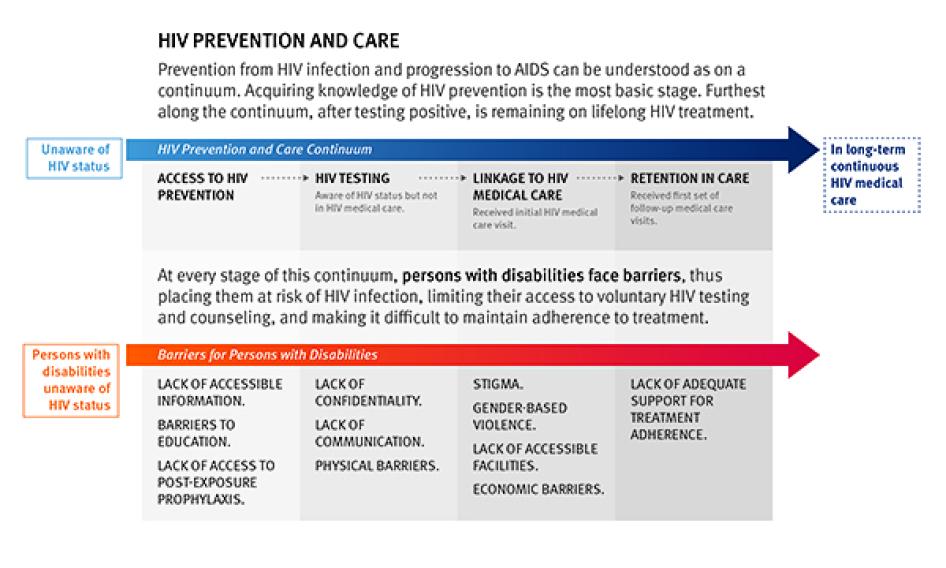

Prevention from HIV infection and progression to AIDS can be understood as on a continuum. At the most basic is acquiring knowledge of HIV prevention. Further along the continuum are such steps as being able to access HIV testing and then, if testing positive, gaining access to treatment and care, and being able to remain on lifelong treatment.

At every stage of this continuum, persons with disabilities face stigma, discrimination and communication and information barriers, thus placing them at a risk of HIV infection, limiting their access to voluntary HIV testing and counseling – which is a critical entry point for linkage to antiretroviral treatment and care – and making it difficult to maintain adherence to treatment.

Pervasive Stigma and Discrimination

Social Isolation in the Community

In Zambia, disability is often considered a curse or punishment caused by evil spirits or witchcraft, in response to the actions of family members. Carol A., the mother of a 14-year-old boy who has paralysis in his arms and legs due to meningitis, told Human Rights Watch that people in her community say things like, “Maybe the grandfather is sucking the child’s blood and selling it so he can add years to his life.”[51] People with disabilities told Human Rights Watch that community members also say a person acquired his or her disability because “they stepped on a charm,” or they have “been bewitched” by unseen spirits.[52]

Persons with different disabilities experience stigma and discrimination in different ways. Franklyn C., who is deaf, told Human Rights Watch: “In the community they see you using your hands and they think you are part human, part animal and don’t want to associate with you.”[53]

Persons with psychosocial disabilities and those living with epilepsy are often feared or viewed as being violent. Samson B., who is receiving treatment for psychosis, said: “Sometimes people say that they should not come near me because I am mentally disturbed and maybe I will throw stones at them.”[54]

Persons with disabilities are often called by denigrating and stigmatizing names. For example, individuals with psychosocial and intellectual disabilities are called “chibulu” (one who doesn’t understand), “wofunta” (mad) or “silu” (insane).[55] People with psychosocial disabilities are also called “a Chainama,” based on the name of the main psychiatric hospital in Zambia, the Chainama Hills Hospital.[56]

Patrick M., a 43-year-old man with a physical disability, described how social and physical isolation limit access to HIV information: “Health workers come from town and speak to a group of people gathered, but if you can’t go, you don’t get the information. You are cut from it. People with disabilities are left in the house.”[57]

Stereotypical views regarding the sexual and reproductive lives of people with disabilities also impede access to sexual and reproductive health and HIV prevention information. Susan M., a single mother with a physical disability, told Human Rights Watch: “People think that people with disabilities can’t have boyfriends, girlfriends...They can’t feel sex...They must be just staying at home as a disabled.”[58]

Inocente T., a man who is blind, told Human Rights Watch that some people in his community “believe that someone who has a disability should not indulge in sex. There is stigma…[but] we are human beings like any other person.”[59] Such views impede the ability of people with disabilities to access condoms. As Leonard C., a man with physical and visual disability explained: “We are too shy to go to the shops to get condoms…even to the clinic” because of the fear of what members of the community will say when people with disabilities are seen getting condoms.[60]

Patrick M., the 43-year-old man with a physical disability, said:

Sometimes people think that when you marry someone disabled, you will have children with the same disease. They think that you can’t do anything in society. Can’t get married. People in the community discouraged women from marrying me. People don’t like us. They think that disability will pass to our children. We will just have another problem...People are surprised that I have six children. They say ‘Wow, so these are your children?’ ”[61]

Human Rights Watch found that people with disabilities, like Jane Chalembwa (pictured here), the mother of three children, are often confronted with negative attitudes in Zambia about their right to marry and have children. © 2014 Justin Purefoy for Human Rights Watch

Stigma and Discrimination in Healthcare Settings

“We don’t counsel people with disabilities about HIV prevention, as there is no point.”

—James S., a home outreach volunteer for rehabilitation services, Livingstone, November 2013

Stigmatizing environments and attitudes within health facilities also create barriers for persons with disabilities and their caregivers in accessing health information, testing and treatment. The mother of a child with cerebral palsy and intellectual disability, told Human Rights Watch: “If we mothers have ‘too big’ children on our back, we get stares and negative comments from people at the clinic…Stigma barricades you and your child.”[62]

While most people interviewed by Human Rights Watch did not experience direct discrimination by healthcare workers, some health workers made assumptions about whether people with disabilities can understand health information or held mistaken beliefs about their vulnerability to HIV. Samson B., a man with a psychosocial disability, told Human Rights Watch: “I see that they think that because I’m mentally disturbed, there is no need [for the health workers] to talk to me about HIV.”[63]

While some people with disabilities rely on their caregivers and family members for HIV prevention information,[64] others do not feel they can access HIV information. Lusa Kabemba, a blind woman who provides services for women with visual disabilities told Human Rights Watch, “A lot of people in the compounds who don’t have the information I have would rather just die because of the stigma.”[65]

Many persons with disabilities interviewed told Human Rights Watch that they are often confronted by perceptions that they are asexual or do not have a right to full sexual and reproductive lives.[66] Yvone L., who has a physical disability and works with women with disabilities, said: “When you go for VCT [voluntary counseling and testing] you are looked up and down, people say, ‘Why should you be in the line? Who could give you HIV?’ They don’t expect disabled women to be sexually active.”[67]

In some cases, persons with disabilities said that health workers providing pre- and post-HIV test counseling could be helpful or in some cases harsh or hurtful to them. Philip M., who has a physical disability and is the father of six children, said: “When they find that a disabled person is affected [positive], some [nurses] will encourage that person, but some will use bad words, like: ‘You know the way you are and you start doing this? How are you going to live? You can’t work.’”[68] Michael C., a 30-year-old man with a physical disability told Human Rights Watch: “They say ‘Why should you get involved in sex if you are disabled. You don’t even feel sorry for yourself.’…But we have a right to have sex.”[69]

Women with disabilities also said that health workers expressed negative and stigmatizing attitudes toward pregnant women with disabilities. Yvone L. said, “If you go for pregnancy care, they counsel you publicly as if you have done something wrong and everyone is free to make comments…‘Why should you become pregnant?’ Everyone gets shocked.”[70]

Many persons with disabilities interviewed told Human Rights Watch about their preference for peer counselors at general health facilities or testing facilities for people with disabilities. Gordon K., a 26-year-old deaf man in Kitwe, explained: “Some of us deaf, we are afraid to even talk about it…Afraid to discuss topics of sex, HIV…so it is better with a deaf counselor.”[71] Candice L., a blind woman, told Human Rights Watch: “VCT is the starting point. It would be good to have our own VCT where we could test each other on our own, then we could refer to a clinic. We are being left out.”[72]

Double Stigma and Linkage to HIV Treatment & Adherence

After testing positive for HIV, individuals with disabilities face difficulty linking to ART because of stigma or fear of loss of confidentiality. The experience of stigma by persons with disabilities is not dissimilar to many people without disabilities who are living with HIV. However, persons with disabilities face compounded barriers because their fear of HIV-related stigma is heightened by lack of accessible HIV information and negative attitudes about their sexual and reproductive lives by health workers and people in the community.

For example, Bruce A., who has a physical disability and lives in a small farming community outside of Livingstone, told Human Rights Watch that he is scared to start ART and has not continued his follow-up appointments after receiving his positive HIV test because he fears that women in his community will be further discouraged from forming an intimate relationship with him: “The women’s families already tell them not to marry a cripple.”[73]

Persons with disabilities are also affected by internalized stigma, which impacts their linkage to treatment. Ruth L., an ART counselor in Ndola, told Human Rights Watch: “Some people with disabilities look down upon themselves, become withdrawn after VCT – they don’t want to follow-up for treatment.”[74] Lucy B., who is blind and recently finished secondary school, said: “Most of us with disability are not free to talk about our [HIV] condition…We are ashamed because we are seen as a double burden to society.”[75]

Jacob T., a 44-year-old deaf man, told Human Rights Watch about how he and his wife (who is also deaf) struggled to accept their positive status: “I was so ashamed in front of the doctor – I didn’t even know what it was to be HIV-positive – others will look down at you – for some time, we didn’t tell anybody except me and her…I was worried that I have made a mistake because I have been going with others – I kept that a secret to myself.”[76] He said that he and his wife experienced heightened fear of HIV-related stigma because of negative community attitudes about their right to a full sexual and reproductive life as a deaf couple.

Several persons with disabilities told Human Rights Watch that they preferred not to seek ART at their local or closest health facility providing ART because of their fear of stigma.[77] Matthew C. who has a physical disability, explained: “There is no privacy in the clinic – you can meet others from our community there and don’t want them to know your status…some of us would prefer to go for ART to a clinic far away.”[78] While this fear of HIV related stigma is not unique to persons with disabilities, many of them told us that they face a heightened concern for privacy because of the double stigma they face in the community - related to both their disability and HIV status.

HIV-related stigma also creates barriers for individuals with disabilities in adhering to treatment. Persons with disabilities are often reliant on relatives or others to take them to medical appointments or communicate information to them, and therefore have to tell them about their status, depriving them of confidentiality and risking a stigmatizing response.

According to the Persons With Disabilities Act 2012, the government (through the Zambia Agency for Persons with Disabilities) is obligated to “carry out programmes and conduct campaigns…to raise public awareness…to combat stereotypes, prejudices and harmful practices relating to people with disabilities in all areas of life.”[79] However, to date legislation has had little impact on the prevailing negative societal attitudes and effects of stigma on persons with disabilities.

Barriers to HIV Prevention Services

Lack of Access to Inclusive HIV Prevention Education in the Classroom

Schools play an important role in addressing the knowledge gap in HIV prevention among children and young people. In Zambia, HIV education in schools is predominantly provided through the “Life Skills Education Framework” and is integrated with the teaching of core curriculum subjects, rather than being delivered as a comprehensive, stand-alone unit.[80]

However, because of lack of effective access to education, children with disabilities are unable to access HIV prevention information on an equal basis with others. According to one study, children with disabilities are almost three times more likely to have never attended school in Zambia than children without disabilities in the same household.[81]

Stephen M., a deaf youth from a peri-urban area explained, “We have discrimination in our own homes...Hearing siblings come first...Even my father refused to pay [my] school fees but my brothers and sisters went to school.”[82] In some communities, children with disabilities are denied the chance to go to school. One rehabilitation home care worker told Human Rights Watch: “It’s a challenge for disabled children to go to school, especially those with intellectual disabilities...Disabled children are looked at as useless.”[83]

Child with physical disability in a special education facility in Ndola. © 2014 Rashmi Chopra/ Human Rights Watch

Yet even when children with disabilities are able to attend schools, they are often left out of instruction on HIV because of stereotypical perceptions of teachers that children with disabilities do not need to learn about HIV or due to the lack of appropriate materials. Anita C., a special education teacher for children with intellectual disabilities, explained, “We get no adapted materials...Once in a blue moon, we get HIV materials…If we have money, we buy some or make some...These children [with intellectual disabilities] are vulnerable – we need pictures and other materials to educate them.”[84] To date, the Life Skills learning materials are not available in braille, large print, sign-language symbols or simplified formats.[85]

Special education teachers and head teachers also told Human Rights Watch that while their schools provide peer-based extra-curricular HIV prevention education to students through programs such as “Anti-AIDS Clubs” or “Safe Love Clubs,” special education teachers are typically not involved in such initiatives and children with disabilities are often not encouraged to participate in these activities.[86] As one teacher for deaf students said: “Sexuality and HIV education is just for the hearing and their teachers.”[87] Of the 44 students with disabilities interviewed, only a few had participated in such clubs.[88] Special education teachers and students with disabilities are also typically excluded from special HIV prevention programming in schools.[89] For example, the “Delayed Sexual Debut” project involving training of peer youth educators and teacher champions across 13 schools in three districts in Zambia in 2012 did not include special education teachers or students attending special education units.[90]

Lack of Appropriate HIV Prevention Information

Persons with disabilities lack access to inclusive HIV information and communication, particularly persons with visual, hearing or intellectual disabilities. Few print materials are produced in braille, large print, or with sign language symbols.[91] Most organizations working on HIV prevention who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that small volumes of materials are produced in braille and sign language with limited dissemination for special events such as World AIDS Day.[92] George Mizinga, a blind man who runs an organization in Livingstone for persons with disabilities, told Human Rights Watch: “Some material is translated into braille in Lusaka but it rarely reaches here.”[93] Several DPOs and teachers told Human Rights Watch that available HIV materials in braille often contain outdated information.[94]

Deaf counselors and sign language interpreters told Human Rights Watch about the need to develop signs for technical terms associated with HIV and sexual and reproductive health and the need for standardization of sign language vocabulary.[95] Deaf people also raised their concerns about the compounded barriers faced by deaf people who are not literate. A deaf man explained: “They don’t consider the deaf who can’t read...Recently, there was a campaign on male circumcision but it didn’t get to the deaf.”[96]

DPOs representing different disabilities also told Human Rights Watch about the lack of materials in simplified language or visual formats for people with intellectual and learning disabilities and people with low literacy levels.

Many people whom we interviewed expressed a need for peer-to-peer communication and the importance of peer verification of information.[97] Jacob T., a 44-year-old deaf man, said, “I see posters and pamphlets but I learned about male circumcision at the deaf church…better to educate from deaf to deaf.”[98] One deaf counselor told Human Rights Watch, “Some [deaf] are afraid to even talk about it...afraid by subjects of sex, condoms... We teach each other about why AIDS comes.”[99] However, people with disabilities are rarely included in peer-based programming, and HIV counselors with disabilities receive little training and support on peer to peer counseling.[100]

While a few NGOs are actively working on inclusion of persons with disabilities in community-based sensitization activities, Human Rights Watch found that people with disabilities in many communities are excluded from activities involving theatre, mobile outreach and community meetings and clubs due to physical and communication barriers and isolation within the community. Rosemary T., a counselor who works with a community-based sexual and reproductive health program in five districts in the Copperbelt province, told Human Rights Watch: “Communication is a barrier to disabled people coming to the meetings...The youth in the districts asked for training in sign language because they were having trouble communicating with the deaf.”[101]

Despite their vulnerability to physical and sexual violence, Human Rights Watch found that women and girls with disabilities and their families are often excluded from community-based initiatives to prevent gender-based violence (GBV). Since the passage of The Anti-Gender-Based Violence Act in 2011, there has been an increase in community mobilization initiatives to raise awareness about prevention of and protection from gender-based violence.[102] However, most of these initiatives do not address persons with disabilities and parents of children with disabilities. Anti-GBV clubs formed by community members typically do not involve persons with disabilities in their leadership or membership and do not conduct inclusive activities for people with disabilities.[103]

Community workers and healthcare workers told Human Rights Watch that women and girls with disabilities who have been victims of sexual violence are also typically unable to access information about post-exposure prophylaxis (to reduce the risk of HIV infection) because of communication barriers and isolation from health and protection services. Information materials about the Anti-Gender-Based Violence Act, Victim Support Unit services at police stations, post-exposure prophylaxis and access to protection services are not provided in braille, large print, simplified formats or sign language.[104] The Anti-Gender-Based Violence Act contains limited provisions about equal access to services by people with disabilities. The National Guidelines for the Multidisciplinary Management of Survivors of Gender Based Violence in Zambia do not address treatment, care and support of women and children with disabilities.[105]

Sylvester Katontoka, an activist with a psychosocial disability, suggested that the government and organizations providing HIV services need to work more closely with DPOs to identify community leaders and outreach methods that can assist in mobilizing people with disabilities who are living in fear and isolation.[106]

Lack of Access to Condoms

People with sensory or physical disabilities told Human Rights Watch that they experience a number of challenges in accessing and using condoms, including the lack of accessible information and education.[107]

George Mizinga, who is blind, told Human Rights Watch of the need for education on condom use: “Condom use is difficult for the blind. It’s more difficult to teach a blind person to use a condom. They have to be able to touch - you can’t just show them and say do it like this.”[108] Dominic Vwalya, a 40-year-old blind man, said: “A blind person probably relies on their partner to help with using a condom. I can do it by feeling, but I’m not going to see whether it is damaged. The expiry date can be a problem. The one selling might give you the expired ones.”[109]

Michael C., a 30-year-old man with a physical disability, told Human Rights Watch that people with physical disabilities need specialized instructions on how to use condoms: “If one has weak limbs or a downward posture...no one is willing to give information on how to use them and it is difficult sometimes if you have to rely on the partner.”[110]

Several women with physical disabilities also said that they had trouble: “We want to access female condoms but we are too shy to move from where we are to the clinic.”[111] Most of the people with disabilities interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they preferred obtaining condoms from DPOs and other local community-based organizations providing services to persons with disabilities, rather than from clinics or shops. They also expressed the need for peer-based training on condom use.

FaithFaith, 25, became deaf when she contracted cerebral malaria at the age of 5. She attended a special school only for a few years, dropping out because her family could not afford the transportation costs and did not believe she would benefit from schooling. Faith did not learn formal sign language properly and cannot read. She now communicates through a mix of formal sign language and traditional signs that are understood and translated by her brother and mother with whom she lives. Faith found out she was HIV-positive in 2012 after giving birth to her daughter, who is also HIV-positive. Her husband verbally abuses her and is often absent. Faith did not know about HIV prevention until she tested positive. Sensitization meetings and workshops on HIV prevention in her local community are not conducted in sign language. She relies on her mother and brother to accompany her to appointments for antiretroviral treatment and to help her understand information provided by the clinic about antiretroviral treatment for her and her baby. They also help Faith care for her baby. There is no sign language interpreter at the clinic she visits. Faith does not like going to the clinic because people in the waiting area often stare at her when she is signing and make comments about how someone like her can be HIV-positive. One healthcare worker told Faith and her mother that someone like Faith should not be allowed to have any more children. |

Barriers to Voluntary HIV Counseling and Testing Services

Voluntary HIV counseling and testing is the entry point for critical linkages to care and treatment. In Zambia, HIV counseling and testing is either provided at voluntary HIV testing sites where individuals self-present for testing, or at the initiation of healthcare providers. In the latter case it is initiated as a routine offer of testing (such as to pregnant women in antenatal care to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV) or as a diagnostic service in clinical settings for patients who present with symptoms that could be attributed to HIV.[112] Despite progress, voluntary testing in the general population, at 24.3 percent (tested in past 12 months) has remained low due to a number of factors including HIV stigma and fear of social rejection, fear of rejection by family or intimate partner and concerns about antiretroviral treatment.[113]

Information and Communication Barriers

Persons with disabilities told Human Rights Watch about the lack of effective counseling services because of inadequate training of healthcare workers in how to communicate with and address the concerns of people with disabilities. Paul C., who has a psychosocial disability told Human Rights Watch: “VCT counselors need to be better trained...need to provide more than a test...not just about taking the test but about counseling that the result is not a death sentence.”[114]

Healthcare workers told Human Rights Watch about the lack of training and support provided to them in relation to people with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities.

Thomas L., a VCT counselor at a district clinic in Ndola, told Human Rights Watch:

We have some blind and deaf clients. Communication is a challenge. We don’t have anyone trained in sign language and have to write to communicate with the deaf. At the VCT, sometimes the deaf will come with someone to translate, sometimes we will refer them to the central hospital.[115]

Raymond L., a VCT counselor at a district clinic in Livingstone, explained the challenges they face in attending to persons with disabilities:

We have had people who are a bit slow, or with mental illness. It is hard to counsel someone who is mentally challenged. They are not getting it. They are not taking it seriously. We don’t get any training in that. Training would help. Sometime a person is violent when you want to prick them. It would be good to have workshops on people with disabilities.[116]

Felix B., a HIV counselor who provides testing and counseling services to pregnant women at a health center in Livingstone, told Human Rights Watch:

I can remember seeing a girl with a mental disability brought here by a neighbor. She had been raped. She was seven months pregnant when she came in. She was mentally ill...She had VCT. It was difficult to communicate with her. We communicated with her through the woman who brought her. She could understand what I was saying, but she was not responding, touching herself in strange ways, sucking her finger, scratching her head.[117]

According to Zambia’s National Guidelines for HIV Counseling and Testing, HIV testing services should comprise pre-test counseling (which includes providing information about the HIV test and responding to the client’s understanding of HIV/AIDS) and post-test counseling (which includes providing information about additional testing and positive living as well as making appropriate referrals and linkages to care and treatment services).[118] The Guidelines require that “counseling should always be adapted to the needs of the client.”[119] However, due to communication barriers and lack of training of HIV counselors, persons with different disabilities often do not have access to information and counseling on an equal basis with others.

Lack of Confidentiality in HIV Testing

Confidentiality of HIV test results is a cornerstone principle of medical ethics recognized as a best practice. Individuals with disabilities, however, often experience a lack of confidentiality because of communication barriers and the need to involve a third person for interpretation.

Chipo Tembo, a deaf woman who went alone for her first HIV test, told Human Rights Watch: “They [the clinic] didn’t have any sign language. They did a test and asked me to come back. I came back with my mother, but I would have preferred her not to find out then.”[120]

Many deaf people interviewed by Human Rights Watch shared their concern for lack of confidentiality by the sign language interpreter present during the testing and counseling session. Mackenzie Mbewe, a deaf man, told Human Rights Watch: “When you go with an interpreter, there is no confidentiality. They [the interpreters] can’t keep secrets…That is why we want nurses and doctors to be trained to interpret because they have ethics. Ethics training for interpreters would also be a good idea.”[121]

Lidia A., a deaf woman from Kitwe told Human Rights Watch about how confidentiality can also be breached by family members of friends: “Even if the interpreter is a friend of a family member, information spreads quickly...If it’s the wife, the husband will know quickly.”[122] In a few instances, deaf people told Human Rights Watch of their preference to access HIV testing facilities outside of their local communities because they are afraid that their status will be disclosed to community members by a known sign language interpreter.[123]

Zambia’s National Guidelines for HIV Counseling and Testing require that “it is essential that confidentiality be maintained when conducting HIV testing of any type.”[124]

Concerns about Free and Informed Consent in HIV Testing

HIV testing without consent, like violations of confidentiality, is contrary to medical ethics and best practices.

Representatives of MHUNZA, the Mental Health Users Network of Zambia, the national DPO of persons with psychosocial disabilities, told Human Rights Watch, that some people with psychosocial disabilities attending psychiatric units in general hospitals as in-patients are not ensured of full and informed consent for HIV testing.[125] Psychiatric clinical officers and medical staff from three psychiatric units interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported varying application of HIV testing consent procedures in the healthcare setting as well as confusion concerning the testing policy.[126]

The Guidelines distinguish between voluntary HIV testing, where the “client/patient has to actively and freely choose to take an HIV test, for example visiting a VCT centre” and routine or provider-initiated testing and counseling (PITC) or diagnostic counseling and testing (DCT), where the testing is conducted on the basis of “opt out screening.”[127] In the latter context, “the test is automatically performed unless the individual concerned raises an objection and opts out.”[128]

Medical staff from two psychiatric units told Human Rights Watch that they inform patients that the HIV test is being performed as part of other diagnostic tests and refer them for further pre-test counseling if they refuse or are uncomfortable with the testing.[129]

In the third psychiatric unit, healthcare workers told Human Rights Watch about differing testing practices and confusion about the government’s testing policy in health settings. A psychologist at the psychiatric unit told Human Rights Watch of the practice of testing for treatment purposes and disclosing the result to the patient only if they have accepted voluntary testing:

It is mandatory to run tests including HIV tests. There is a Ministry of Health policy that distinguishes between diagnostic testing and VCT. You can do diagnostic testing if you need to know a patient’s status for their treatment. They say that when you agree to be admitted, you agree that they can draw blood. You do baseline tests, including HIV...but the policy is not clear and nobody checks how it is applied. If we test someone and find out that they are positive, and have a low CD4 count, we will talk to them and try to get them to do VCT. … If we know that a patient is positive, we would try to get them to do VCT before they are discharged, but if they will not consent, we don’t tell them. So many people are positive and it influences all their other conditions, so we need to know their status to treat them better – you could be dealing with an OI [opportunistic infection] and not know.[130]

A clinical psychiatric officer at the same hospital told Human Rights Watch:

There is mandatory HIV testing when the patients come. If they are positive, they need to know so that they know which medications to start with. Else we’re killing them. We counsel them – can we examine, test and tell them? But we already know. HIV mimics a lot of other psychiatric disorders, that’s why we have to look for HIV.[131]

Another clinical psychiatric officer told Human Rights Watch about the need for routine HIV testing in mental health units: “If we suspect that an acute patient might be positive, we ask for an HIV test...drug reactions are one of the reasons why we test people for HIV when they are admitted. Carbamazepine interacts with ARVs and can cause drug resistance because it causes the ARVs to be cleared from the blood faster.”[132]

Staff from all three psychiatric units expressed the need for more training on ethical standards and application of the testing policy, and may be using terms such as ‘mandatory’ or ‘routine’ in imprecise ways to describe current practices. Staff said that applying HIV testing policies was especially difficult for patients considered to be in an “acute condition.”

The Guidelines provide that while both voluntary and routine HIV tests require a person’s full written or verbal consent, testing can be done without explicit consent in a number of circumstances including where “patients [are] unable to give consent (unconscious, mentally impaired) in whom HIV testing is deemed essential for management and no next of kin is available.”[133]

Free and informed consent is critical in the provision of HIV services. Exceptions to this requirement under Zambian guidelines, such as on the grounds of mental impairment, are not compliant with articles 12 and 25 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.[134] The pending 2014 Mental Health Bill provides for “supported decision making” for persons with disabilities as required for implementation of the right to exercise legal capacity, in line with article 12 of the CRPD.[135] The CRPD obligates governments to ensure free and informed consent in medical care and treatment including through training and promulgation of ethical standards for public and private health care.[136]

Barriers to Treatment, Care, and Support

Barriers to Treatment Adherence

A high level of adherence is crucial for the success of antiretroviral therapy (ART). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “adherence to ART is well-recognized as an essential component of individual and programmatic treatment success.”[137]The World Health Organization found that “higher levels of drug adherence are associated with improved virological, immunological and clinical outcomes and that adherence rates exceeding 95 percent are necessary in order to maximize the benefits of ART.”[138]Lack of adherence can lead to the development of drug resistance, illness, or death.

The lack of “treatment literacy” or counseling for individuals with disabilities creates significant barriers in adhering to treatment.

Many of the people with disabilities interviewed by Human Rights Watch, in particular deaf and blind people, reported that healthcare workers do not adequately elicit personal health information, diagnose, and prescribe medication and counsel people with disabilities when they visit health facilities for scheduled appointments for ART or in relation to opportunistic infections. Several deaf people on ART told Human Rights Watch about the lack of information exchange about their condition during their initial and follow-up appointments due to communication barriers including the lack of sign language interpretation.

One deaf ART patient in Lusaka told Human Rights:

“We communicate by writing a little...She [the counselor] doesn’t ask me anything - just counts my tablets and points to how many I take.”[139]

Chipo Tembo, a deaf woman, also explained:

“I write and they write…we use the broken English of my deaf culture. It is very difficult because sometimes I try to explain why I feel ill, but I’m not sure they understand me and give me the right medicine to take.”[140]

Another deaf patient on ART told Human Rights Watch about the lack of counseling on the importance of adherence:

“The doctor doesn’t teach how to take them…they just do the basics...He just says to take this medicine and come back and get some more without giving any other information like why not to skip the medication.”[141]

Sometimes, interpretation is available at hospitals, however. For example, Noreen C. who takes her deaf 14-year-old nephew to the health clinic for his ART appointments in Kitwe, explained: “We have limited capacity to talk to Samuel because we don’t sign. When I asked the doctors to tell him the effects of stopping taking his medicine, they brought a sign language interpreter.” Yet “usually they don’t have one,” Noreen C. said. “We worry if he will get the support he needs without someone to sign with him.”[142]

Dominic Vwalya., who is blind, told Human Rights Watch that blind people become more anxious about ART because they do not get accessible information about antiretroviral drugs and side effects from the counselors:

There are instructions attached to the medicine inside the box. How was I going to read to know the instructions? Or what if there was no one at home to read English? The instructions say: There might be reactions, you might feel a rash, headaches, constipation, abnormal urine, you must take much water. I had to ask another one who is taking the same medicine about these things.[143]

Many people with psychosocial disabilities told Human Rights Watch about their anxiety due to the lack of information given to them about the interaction and effects of taking ARV and psychotropic drugs. Gabriel L., a 38-year-old man from Lusaka, said he cannot access ART and mental health treatment at the same location and that he is not provided information about the combined burden of the two drug regimens by his ART counselor or by the clinical officer prescribing psychotropic drugs.[144] He told Human Rights Watch: “We have patient rights to information...about HIV and psychotropic medicines...but we are not told about this by anyone, about the dosage and interaction...These are very strong drugs...We must know about it.”[145]

Several persons with disabilities told Human Rights Watch that they wanted information about taking psychotropic drugs in addition to ARV medicine, but were scared to tell their ART counselor about their psychosocial disability (and disclose they were on psychotropic medication) because of their fear of being stigmatized as a “mad” person.[146] While in some locations mobile health clinics are being piloted at health care sites providing ART, integration of HIV services with mental health service provision remains low.[147]

The Persons with Disabilities Act obligates the government to ensure that health professionals “provide care of the same quality to people with disabilities as to others”[148]; to provide “systems to avail appropriate facilities and personnel to local health institutions for the benefit of people with disabilities;”[149] and “include the study of disability and disability related issues in the curriculum of training institutions for health professionals.”[150] Many healthcare workers providing HIV services interviewed by Human Rights Watch expressed the need for training on how to address communication challenges and provide psychosocial support to persons with disabilities.

Lack of Appropriate Adherence Monitoring

Strict adherence to ART is supported by ongoing monitoring of how a patient is maintaining the prescribed medicine regimen, which can be influenced by social and clinical factors. ART counselors assess adherence at regular intervals when patients attend scheduled appointments to collect a prescribed supply of medicine.

More than half of the persons with disabilities interviewed who disclosed that they were enrolled in ART told Human Rights Watch that they sometimes experience difficulty in keeping scheduled appointments due to the lack of availability of a family member or friend who can act as a guide for the blind, provide mobility assistance to persons with physical disabilities or communication assistance to deaf people or persons with intellectual disabilities.

The majority of persons with disabilities interviewed who were enrolled in ART, told Human Rights Watch that no accommodation is made for their circumstances, such as appointment re-scheduling or providing a longer supply of medicine on an individualized basis. Instead, individuals with disabilities were often told they had “defaulted” and were given a shorter supply of medicine as a consequence of missing an appointment.[151]

Dominic Vwalya., who is blind, said:

If you miss an appointment, they [ART counselors] become suspicious that you are not taking medicines. I need a guide to get to an appointment – this is difficult. When there were some bad times, I couldn’t go on the actual date. Since I missed an appointment, they put me on a two-week supply which was a challenge – as I need to take my nephew or niece (who are at school) to go with me to the appointment...They need to be pulled out of school to come with me.[152]

Persons with disabilities told Human Rights Watch that they feel stigmatized by being labeled as a “defaulter” by healthcare workers and are burdened with increased transportation costs and difficulties in arranging mobility or other assistance when they are required to attend appointments more frequently.[153]

Candice L., who is also blind, told Human Rights Watch:

One time, my children were doing year 9 exams so they couldn’t accompany me. I had medicine for that day and another day. I didn’t go that day. The counselor said: “You are a defaulter so you have to come back to the clinic in one week.” I usually get a three-month supply of ART, [but] I was given supply of only one week. I didn’t like being called a “defaulter.” I had done nothing wrong. So I refused and went to another clinic.[154]

In a few instances, persons with visual and physical disabilities and healthcare workers told Human Rights Watch that these circumstances were anticipated and resolved as a result of mobile and home outreach services.[155] However, most people with disabilities interviewed told Human Rights Watch they did not have access to these services.[156]

ART counselors told Human Rights Watch that they find it more difficult to adapt adherence management protocols for people with disabilities due to communication barriers and concerns about lack of follow-up alternatives, especially where there are no mobile or outreach services available. Ruth L., an ART counselor in Ndola told Human Rights Watch:

You have to counsel patients if you are giving them a lot [supply of medicines]. Usually you want to monitor side effects but sometimes there are reasons to give an even longer supply. But we worry that if we give too many medicines to someone far away, they may sell it...We also want to check CD4 and viral load.[157]

According to the national ART protocols on adherence management, a defaulter status is recognized “when a person who has been located as late or lost to follow-up chooses not to return to care.”[158] However, healthcare workers and persons with disabilities enrolled on ART told Human Rights Watch about the use of the term in connection with patients who had missed appointments but were still linked to care. The protocols also provide guidance on tracking and follow-up of patients who miss appointments including SMS messaging, home visits and contact with community workers.[159]

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities obligates governments to develop universally designed services “which should require the minimum possible adaptation and the least cost to meet the specific needs of a person with disabilities” and “to promote universal design in the development of standards and guidelines.”[160]ART protocols and guidelines should be designed to ensure that they address the needs of people with physical, sensory, intellectual and psychosocial disabilities.

Lack of Adequate Adherence and Positive Living Support

“People with disabilities are often the most challenged because they are without a support network.”[161]

—Dr. David M., ART doctor in a health center in Lusaka, November 2014

According to the World Health Organization, “Adherence to ART may also be challenging in the absence of supportive environments” and “informing and encouraging people receiving ART and their families and peers are essential components of chronic HIV care.”[162] Studies show that there is an association between peer support and high rates of adherence and retention.[163]

Many persons with disabilities and health workers told Human Rights Watch that social isolation, stigma and a culture of secrecy about HIV inhibits disclosure of positive status within the family and in the community and hence limits opportunities for support. The sister of a young woman with an intellectual disability told us: “She cannot come out...She thinks it taboo to say I slept with someone and got it...It becomes something heavy in our culture.”[164]

She also told Human Rights Watch that her sister told her that she feared disclosure because a number of people in their local community believe she should not be leading a full sexual and reproductive life.

Persons with disabilities face heightened barriers to disclosure because of the lack of accessible information on living with HIV and lack of accessible and inclusive positive living support programs, including peer support programs. Philip M., who has a physical disability, told Human Rights Watch: “I know there are some people who are on ART in my community but it is hard for them to talk about it...We cannot talk about it...It is a secret.”[165]

Candice L., who is blind, explained the importance of support structures:

How do you know what time to take your drugs? Some people have talking watches or listen to the radio, or they rely on relatives at home. Sometimes we need encouragement. That is why it is good to open up. My children tell me when it’s time for me to take my ART. People without support miss their treatment, so it is very important to be open in family and community...The able-bodied, they came out together but for us, it is very difficult.[166]

A health worker dispenses antiretroviral medications at Chreso Ministries VCT (Voluntary Counseling & Testing) and ART (Antiretroviral Treatment) Centre in Lusaka. 2014 Justin Purefoy for Human Rights Watch

Particular Challenges Facing Children and Young People with Disabilities

Several children and adults with sensory disabilities and their caregivers in Lusaka and Kitwe told Human Rights Watch about the impact of parents and guardians not disclosing to them that they are in fact taking ARV drugs.[167]

Lucy B., an 18-year-old who is blind and has been raised by her aunt and uncle after her parents passed away, told Human Rights Watch: