“The Power These Men Have Over Us”

Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by African Union Forces in Somalia

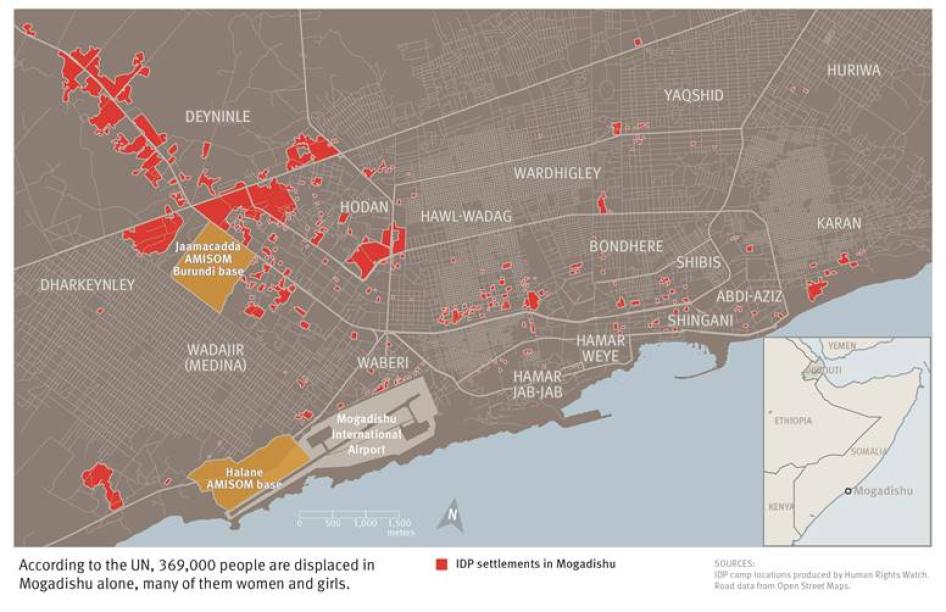

Map

Summary

I was scared he would come back and rape me again or kill me. I want the government to recognize the power these men have over us and for them to protect us from them.

—Farha A., victim of rape by an AMISOM soldier, Mogadishu, February 2014

In June 2013, a Somali interpreter working at the headquarters of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) approached 17-year-old Aziza D.—not her real name—and asked her to “befriend” a Ugandan soldier. He told the girl, who had been struggling to survive in one of Mogadishu’s camps for displaced people, that the soldier could get her anything she needed if she treated him like “he was her husband” and “made him feel comfortable.”

After she met the soldier and it was clear that she was expected to have sex with him, she had second thoughts. The interpreter told her she could not leave and ignored her cries and pleas not to be left alone with him. “When I resisted the soldier’s advances, he became angry and brought back the interpreter who threatened me in Somali,” she told Human Rights Watch.

Years of conflict and famine in Somalia have increased the vulnerability of women and girls like Aziza D., displacing tens of thousands from their communities, often leaving them without their husbands’ or fathers’ or clan protection. Without resources or employment, many women and girls are reliant on outside assistance and forced to do whatever they can to sustain themselves and their families.

The United Nations, Human Rights Watch, and other organizations have documented high levels of sexual and gender-based violence against Somali women and girls, particularly the displaced. But the involvement of AMISOM soldiers has largely been overlooked, including by the mission’s leadership and international donors. As this report shows, some AMISOM soldiers, deployed to Somalia since 2007 to help restore stability in the war-torn capital, Mogadishu, have abused their positions of power to prey on the city’s most vulnerable women and girls. Soldiers have committed acts of rape and other forms of sexual abuse, as well as sexual exploitation—the abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power, or trust, for sexual purposes.

This report is based on research in Somalia, Uganda, and Burundi. Its findings are based on 50 interviews including 21 interviews with survivors of sexual exploitation and abuse as well as interviews with witnesses, foreign observers including officials from troop-contributing countries, and other military personnel. The research documents incidents of sexual exploitation and abuse in the Somali capital, Mogadishu, predominantly by personnel of the Ugandan People’s Defence Forces (UPDF) at and around AMISOM’s headquarters, the AMISOM base camp, and at the camp of the Burundian National Defense Forces (BNDF) contingent in Mogadishu. All of the incidents documented in this report occurred since 2013.

Given the particularly complex and sensitive nature of this research topic, security concerns, as well as the profound reluctance of survivors and witnesses to speak out about their experience, Human Rights Watch did not asses the scale or prevalence of the abuse. Nonetheless, the findings raise serious concerns about abuses by AMISOM soldiers against Somali women and girls that suggest a much larger problem.

Human Rights Watch documented 10 separate incidents of sexual abuse, including rape and sexual assault, and 14 cases of sexual exploitation. Four of the rape cases and one sexual assault involved girls under eighteen. The youngest victim in the cases we investigated was a 12-year-old girl in the outskirts of Baidoa in May 2013 who was allegedly raped by a Ugandan soldier. According to court-martial officials in Uganda, there is a rape case of a minor pending before Uganda’s military courts, but it is not clear if this is the same case.

Members of African Union (AU) forces, making use of Somali intermediaries, have employed a range of tactics to get private access to Somali women and then abuse them. Some AMISOM soldiers have used humanitarian assistance, provided by the mission, to coerce vulnerable women and girls into sexual activity. A number of the women and girls interviewed for this report said that they were initially approached for sex in return for money or raped while seeking medical assistance and water on the AMISOM bases, particularly the Burundian contingent’s base. Others were enticed directly from internally displaced persons (IDP) camps to start working on the AMISOM base camp by female friends and neighbors, some of whom were already working on the base. Some of the women who were raped said that the soldiers gave them food or money afterwards in an apparent attempt to frame the assault as transactional sex or discourage them from filing a complaint or seeking redress.

The women and girls exploited by the soldiers are entering into the AMISOM camps through official and guarded gates, and into areas that are in theory protected zones. Human Rights Watch was aware of a few cases in which the women were given official badges to facilitate their entrance. Sexual exploitation has also taken place within official AMISOM housing. These practices all point toward the exploitation and abuse being organized and even tolerated by senior officials.

Most of the women interviewed for the report were sexually exploited by a single soldier over a period of weeks and even months, although some had sex with several soldiers, notably at the Burundian contingent’s base.

The line between sexual exploitation and sexual abuse is a fine one given the vulnerabilities of the women and the power and financial disparities between them and the soldiers. The women who are sexually exploited become vulnerable to further abuse at the hands of the soldiers, and are also exposed to serious health risks. Several women said that the soldiers refused to wear condoms and that they had caught sexually transmitted infections as a result. Several also described being slapped and beaten by the soldiers with whom they had sex.

Only 2 out of the 21 women and girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch had filed a complaint with Somali or other authorities. Survivors of sexual violence fear reprisals from perpetrators, the government authorities, and the Islamist insurgent group Al-Shabaab, as well as retribution from their own families. Some said they felt powerless and worried about the social stigma they would face if their complaint was to be made public. Others questioned the purpose of complaining when such limited recourse is available. Some were reluctant to lose their only source of income.

The UN secretary-general’s 2003 Bulletin on special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse, a groundbreaking policy document that catalyzed a range of policy statements on sexual exploitation and abuse in UN peacekeeping missions, explicitly prohibits peacekeepers from exchanging any money, goods, or services for sex. Its definition of exploitation encompasses situations where women and girls are vulnerable and a differential power relationship exists. This definition, which has become the international norm, means that whether a woman has consented to engage in sex for money is irrelevant in the peacekeeping context. The African Union Commission’s Reviewed Code of Conduct (AUC Code of Conduct), with which AMISOM troop-contributing countries must comply, prohibits sexual exploitation and abuse.

Until displaced women and girls in Somalia obtain the means to move beyond mere survival, they will remain vulnerable to sexual exploitation and abuse. They should no longer be faced with the same predicament as 19-year-old Kassa D.: “I was worried, I wanted to run but I knew that the same thing that brought me here would get me through this—my hunger,” she said. “I had made a choice and I couldn't turn back now.”

As in international peacekeeping operations, all AMISOM personnel, including locally recruited Somalis, are immune from local legal processes in the country of deployment for any acts they perform in their official capacity. The troop-contributing countries—the countries from which the troops originate—have exclusive jurisdiction over their personnel for any criminal offenses they commit. However, they are bound both by memorandums of understanding (MoUs) signed with the AU prior to deployment and by their international human rights and humanitarian obligations to investigate and prosecute serious allegations of misconduct and crimes.

AMISOM troop-contributing countries, to varying degrees, have established procedures to deal with their forces’ misconduct. Troops have received pre-deployment trainings on the AUC Code of Conduct, and legal advisors and military investigators have been deployed to Somalia to follow-up on allegations of misconduct. Most importantly, the Ugandan forces deployed a court martial to Mogadishu for a year in 2013. Holding in-country courts martial can help to facilitate evidence gathering, serve as a deterrent, ensure that witnesses are available to testify, and assure victims that justice has been served. The court has since been called back to Uganda.

After initially denying allegations of sexual abuse, the AMISOM leadership has started to take some measures to tackle the problem. In particular, AMISOM developed a draft Policy on prevention and response to sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA policy) in 2013 and has also begun to put in place structures to follow-up on sexual exploitation and abuse.

However, the draft policy will need to be significantly strengthened if it is to be effective. In addition, outreach activities carried out so far appear primarily focused on protecting AMISOM’s image rather than addressing the problem. There are still no complaint mechanisms and little or no capacity to investigate abuses. Above all, there is not enough political will among AMISOM troop-contributing countries to make the issue of sexual exploitation and abuse a priority and proactively deploy the necessary resources to tackle the problem.

Ending sexual violence and exploitation by AMISOM forces should start with developing the political will among the political and military leadership in troop-contributing countries to end impunity for perpetrators of abuse, and ensure survivors are adequately supported. First and foremost, troop-contributing countries should significantly reinforce their capacities to pursue investigations and prosecutions inside Somalia. They should send adequate numbers of trained investigators and prosecutors to Somalia and, where appropriate, hold courts martial inside Somalia.

The AU and AMISOM need to foster an organizational culture of “zero tolerance” where force commanders do not turn a blind eye to unlawful activities on their bases. Commanding officers should do more to prevent, identify, and punish such behavior.

The AU should promptly set up conduct and discipline units within peace support operations and an independent and adequately resourced investigative unit that is staffed by independent and qualified members. AMISOM should also ensure systematic collection of information on allegations, investigations, and prosecutions of sexual exploitation and abuse, and commit to publicly report on an annual basis to the AU on this issue.

These measures will also need to go hand-in-hand with efforts to prevent sexual exploitation and abuse on AMISOM bases, including systematic vetting of all forces to ensure those implicated in sexual exploitation and abuse in the past are not deployed, and proactively recruiting more women into their forces, particularly the military police.

Greater independent oversight of the conduct of AMISOM troops is also needed. AMISOM’s international donors, particularly the United Nations, European Union, United States, and United Kingdom should ensure that the UN Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) has a strong human rights unit and is able to implement the secretary-general’s Human Rights Due Diligence Policy, which seeks to ensure that the UN does not support abusive non-UN forces. International donors should ensure that if there are substantial grounds to believe that forces they support are committing widespread or systematic violations of international human rights or humanitarian law, including sexual exploitation and abuse, and the relevant authorities have failed to take the necessary corrective or mitigating measures, this support should be withdrawn.

|

Abuse of Power: Defining Sexual Exploitation and Abuse The UN secretary-general’s 2003 Bulletin on special measures for the protection from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse by UN and related personnel states that:

The Bulletin explicitly prohibits any “exchange of money, employment, goods or services for sex, including sexual favours or other forms of humiliating, degrading or exploitative behavior.” It further prohibits peacekeepers from engaging in any sexual activity with persons under the age of 18, regardless of the age of sexual consent in the country. [1] |

Key Recommendations

To AMISOM Troop-Contributing Countries (Uganda, Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Djibouti, and Sierra Leone) and Police Contingents

- Hold on-site courts martial in Somalia, either by deploying a permanent court martial to areas of operation or by sending courts martial to Somalia on a regular basis;

- Carry out a thorough background check of all individuals deployed to Somalia to ensure that those implicated in serious violations of international humanitarian or human rights law, including sexual violence, are under investigation, have pending charges, or have been subjected to disciplinary measures or criminal conviction for such abuses, are excluded.

To the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM)

- Urgently finalize the draft Policy on prevention and response to sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA policy)after reviewing and amending it to ensure that it serves as an effective prevention instrument.

To the African Union Peace and Security Council

- Establish a permanent and adequately resourced independent investigative body, staffed by professional and independent investigators, to investigate allegations of misconduct and abuses, including sexual exploitation and abuse, in all AU peace support operations; the body should investigate abuses by military, police, and civilian personnel.

To the African Union Commission

- Compile and publicly release an annual report on investigations into sexual exploitation and related offenses and relevant actions taken by AU peace support operations, including AMISOM, and the AU more generally, to address the violations.

To the African Union Peace Support Operations Division

- Promptly establish a professional and permanent conduct and discipline unit for AMISOM, and other peace support operations, to formulate policies and carry out appropriate training of all AMISOM staff, and to refer misconduct allegations to the appropriate investigative authorities.

To AMISOM Donors including the UN, EU, UK, and US

- If there are substantial grounds to believe that personnel of peace support operations forces are committing serious violations of international human rights or humanitarian law, including sexual exploitation and abuse, and where the relevant authorities have failed to take the necessary corrective or mitigating measures, raise public concern and urge the AU and the troop-contributing country to carry out immediate investigations;

- If substantial allegations are not adequately addressed, consider ending military assistance to AU peace support operations forces, including AMISOM. No assistance should be provided to any unit implicated in abuses for which no appropriate disciplinary action has been taken.

Methodology

This report is based on two fact-finding missions to Mogadishu, Somalia in August 2013 and February 2014 and research in Burundi and Uganda in April 2014. Between September 2013 and February 2014, a Mogadishu-based consultant interviewed Somali women and girls who alleged being abused on AMISOM bases. Security and concerns for the safety of interviewees prevented research in other parts of Somalia. Researchers conducted additional interviews in Nairobi, Kenya.

In Mogadishu, Human Rights Watch interviewed 21 Somali women and girls who said they were victims of sexual exploitation and abuse by AMISOM troops. Human Rights Watch worked with local contacts who helped identify women willing to be interviewed for this report. The majority of women lived in makeshift shelters in camps for IDPs in and around Mogadishu. Importantly, and contrary to the experience of many survivors of sexual exploitation and abuse in Somalia, all victims interviewed for this report had already received some basic assistance from service providers. This included Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) kits for some of the rape victims and antibiotics for the women who had sexually transmitted infections.

Interviewees were fully informed about the nature and purpose of the research and how the information they provided would be used. Human Rights Watch obtained oral consent for each of the interviews. No incentives were provided to individuals in exchange for their interviews. All the interviews were conducted in person, in private, and in Somali with a female interpreter. Care was taken to ensure that interviews about past traumatic events did not further traumatize interviewees and all the women interviewed had access to a local organization providing counseling and other services. The names of women and girls have been withheld and replaced by pseudonyms for their security.

Human Rights Watch did not request to visit military bases on which these abuses took place because of concerns regarding confidentiality and the risk of reprisals against survivors or witnesses following such a visit.

Investigating sexual exploitation and abuse is particularly complex and sensitive in peacekeeping contexts given the stigma associated with these abuses, and the volatile and insecure contexts in which they occur. As described in the Abuses Section of this report, survivors of sexual violence interviewed as part of this research voiced reluctance to talk about their experience due to a very real fear of reprisals from their families, perpetrators, and the Islamist insurgent group Al-Shabaab. Those engaged in sex in exchange for money also said they did not want to lose their main source of income. These factors made it especially difficult to interview large numbers of women to assess the scale or prevalence of such abuses.

Yet, as is highlighted in the accounts, a number of the women and girls interviewed described seeing other women and girls facing similar experiences on the AMISOM bases or being recruited by those already engaged in sex for money on the bases. This would indicate that the total number of women and girls subject to sexual exploitation and abuse by AMISOM soldiers is larger than the sample presented in this report.

With two exceptions, all the cases documented took place on the AMISOM base camp and base of the Burundian contingent. This does not preclude the possibility that similar abuses have occurred on or in the vicinity of other AMISOM bases and outposts in Somalia, for instance in the cities of Kismayo and Baidoa where Human Rights Watch did not conduct interviews due to security concerns.

Similarly, while almost all the women and girls interviewed for this report are from internally displaced communities, Human Rights Watch also received credible reports of women and girls from Mogadishu providing sex for money to AMISOM soldiers on the airport base, and in some cases, living on that base. Human Rights Watch was unable to interview any of those women and girls.

In Uganda and Burundi, Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 military court officials and other military personnel including officials from Uganda’s and Burundi’s offices of the military chiefs of staff, military legal advisors, officers who had formerly served in Somalia, as well as private lawyers and journalists. Human Rights Watch also interviewed 10 other witnesses to sexual abuse or exploitation, including employees on AMISOM bases and international observers.

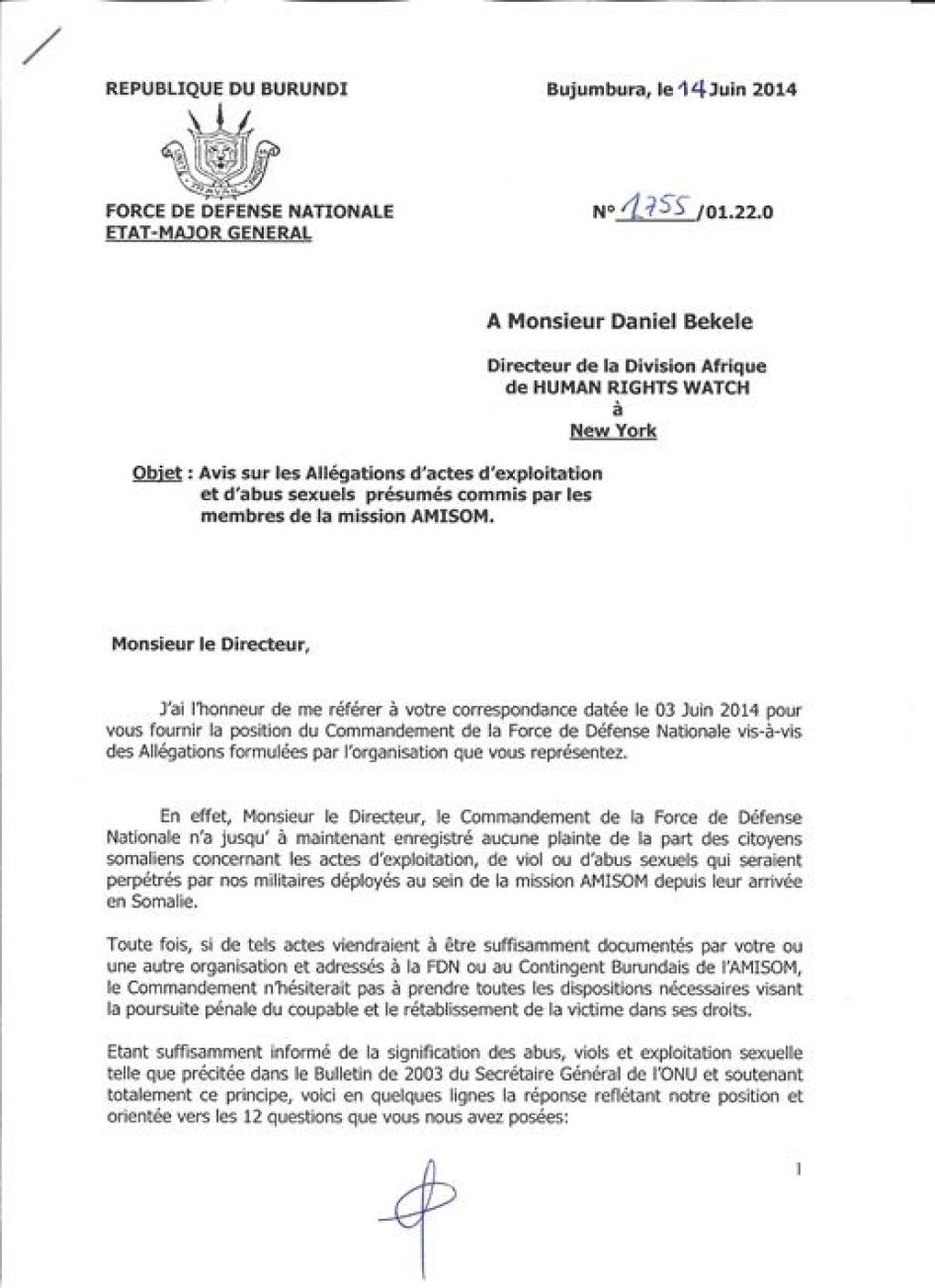

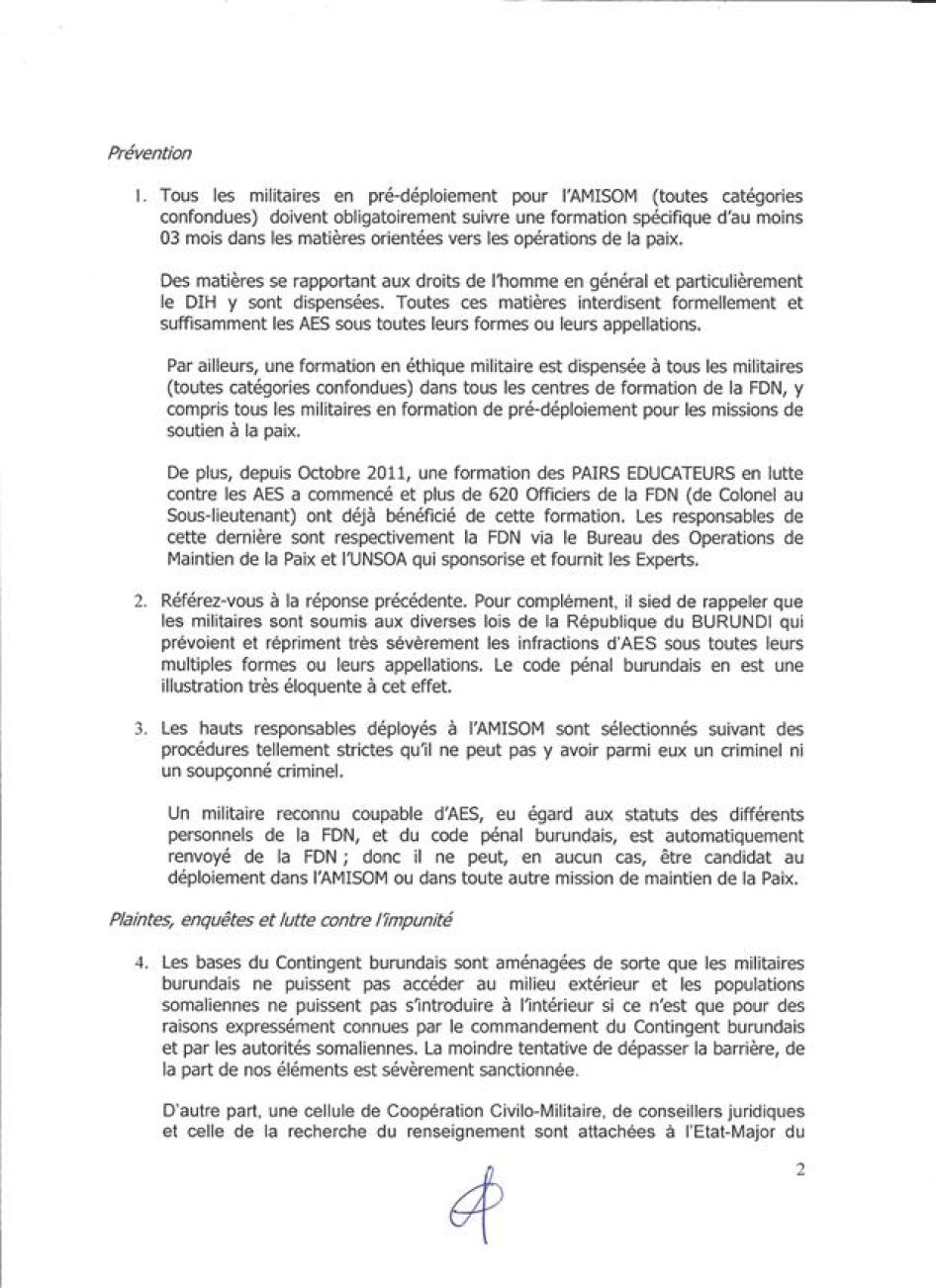

In May and June 2014, Human Rights Watch sent letters with a summary of findings and recommendations, along with research queries, to the Special Representative of the Chairperson of the African Union Commission for Somalia (SRCC), the force commander of the African Union Mission in Somalia, the African Union’s special envoy for women, peace and security, the chief of Defence Forces for the Ugandan People’s Defence Forces (UPDF), and the chief of staff of the Burundian National Defense Forces (BNDF), and requested their responses.[2] The responses of the SRCC and the BNDF are included in the annexes. Human Rights Watch was in email correspondence with the UPDF.

I. Background

Since the fall of the Siad Barre regime in 1991, state collapse and civil war have contributed in making Somalia one of the world’s worst human rights and humanitarian crises. The armed conflict has led to rampant violations of the laws of war, including unlawful killings, rape, torture, and looting, committed by all parties to the conflict, causing massive civilian suffering.[3] The most recent phase of the conflict began in December 2006 when Ethiopia intervened militarily to oust the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) and support the UN-backed Somali Transitional Federal Government (TFG).[4] This intervention, in turn, triggered an insurgency against the Ethiopian and Somali government forces. The armed youth wing of the ICU, Al-Shabaab, emerged as the most powerful armed opposition group in south-central Somalia. [5]

Fighting and famine during Somalia’s long war have displaced millions of people, often repeatedly, either internally or as refugees beyond the country’s borders.[6]

In 2011, a devastating famine emerged from a combination of drought, fighting in Mogadishu, ongoing conflict in southern areas of the country, and restrictions on access for humanitarian agencies.[7] The famine and conflict prompted new large-scale displacement. Assessments of the total number of displaced persons in Mogadishu estimated that at least 150,000 people arrived in the capital in 2011 as a result of the famine.[8]

Violence and dire humanitarian conditions mark daily life for Mogadishu’s IDP population. In a March 2013 report, Human Rights Watch documented serious abuses committed by members of state security forces and armed groups, as well as private individuals controlling the town’s hundreds of camps, against the displaced between 2011 and early 2013. The displaced have been subjected to rape, beatings, ethnic discrimination, and restrictions on access to food, shelter, and freedom of movement.[9] More recently, the UN and international humanitarian organizations have warned of a deteriorating food crisis in Somalia, with particularly alarming rates of malnutrition in Mogadishu’s displaced communities.[10]

Vulnerability of Displaced Women and Girls in Mogadishu

Women and girls constitute a significant proportion of Mogadishu’s displaced population and often suffer sexual abuse by armed men—including both regular soldiers and irregular militia—who rarely face justice.[11]The unequal status of women and girls in Somali society sharply increases their vulnerability to gender-based violence during humanitarian crises. In displaced persons camps, disruptions to community support structures, unsafe physical surroundings, separation from families, and patriarchal governing structures often heighten such vulnerability to gender-based violence. [12]

Somalia’s social system, governed in part by traditional clan structures, leaves displaced women and girls from minority ethnic groups and less powerful clans especially vulnerable to violence due to their social isolation, poor living conditions, and work opportunities.[13] Women and girls from such groups often have very limited access to education and many are unaware of and isolated from the justice system and other government services.

The African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM)

In 2007, the African Union Peace and Security Council deployed a regional peace support force to Somalia mandated by the UN Security Council and supported by the AU’s Peace and Security Operations Division to provide protection for Somali government officials and infrastructure and contribute to the secure delivery of humanitarian assistance.[14]AMISOM was also given a mentoring role to support the “re-establishment and training” of Somali security forces.[15] Since then, AMISOM’s mandate, size, and geographical presence have all steadily increased.

In AMISOM’s first four years, Uganda and Burundi were the only troop-contributing countries. Currently, AMISOM also includes personnel from Kenya, Ethiopia, and small contingents from Djibouti and Sierra Leone, as well as police contingents from Nigeria and Ghana.[16]

AMISOM’s area of operations has been expanded outside the capital to other parts of south-central Somalia. In November 2013, Security Council Resolution 2124 authorized AMISOM to increase its force strength from 17,731 to 22,126 uniformed personnel.[17] More recently, in May 2014, the UN deployed a new guard unit comprised of 410 Ugandan soldiers to protect UN staff in Mogadishu; this force falls under the UN mandate and is therefore regulated by UN rules and regulations, but the rest of the uniformed AMISOM forces are regulated by the AU.[18]

AMISOM receives significant international financial and logistical support as it has been generally credited with having pushed Al-Shabaab out of Mogadishu in mid-2011 and out of other towns since 2012, as well as having provided security to the weak central government in Mogadishu. AMISOM is supported by the UN (logistically and financially), the EU, and bilateral donations—namely from the US, the UK, Japan, Norway, and Canada. The largest cash contributors to the mission are the US, the EU, and the UK.[19]

AMISOM Structure and Presence in Mogadishu

AMISOM is headed by the Special Representative of the Chairperson of the African Union Commission for Somalia (SRCC), a political appointee who oversees the civilian component of the mission, including the mission’s gender unit, established in October 2012.

The military troops are led by a force commander who rotates among the troop-contributing countries. As of August 2014, it was headed by Lt. Gen. Silas Ntigurirwa from Burundi and two deputies from Uganda and Kenya.[20] The six troop-contributing countries are deployed across six different sectors in south-central Somalia and each country has a contingent commander.[21]

The AMISOM Force Headquarters, also known as AMISOM base camp, is located in a former Somali military training camp known as Halane, near Mogadishu’s airport. That base camp hosts the office of the SRCC, the mission’s civilian component, the AMISOM force commander, and the AMISOM police.

An increasing number of embassies and other entities have set up a presence within the large compound of Mogadishu International Airport (MIA). These include UN offices such as the United Nations Support Office for the African Union Mission in Somalia (UNSOA), the UN Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM), as well as the EU Training Mission (EUTM), and diplomatic missions. The Ugandan armed forces, in particular, provide security at the AMISOM base camp as well as perimeter security for the larger airport compound.

The Ugandan contingent command is located on the AMISOM base camp.[22] The Ugandan contingent has other bases in Mogadishu, including the Maslah camp in the Huriwa district of northern Mogadishu, and Ugandan soldiers are also deployed at key government and other strategic locations to provide security.

The Burundian contingent’s base camp is at the compound of Mogadishu’s national university, known as Jaamacadda Ummadda, near X-Control, which is the main checkpoint on the road out of Mogadishu towards the Afgooye corridor. This base camp is surrounded by IDP camps. These include the X-Control camp and further away, the Badbaado and Zona K camps.[23] The Burundian armed forces have at least three other bases in Mogadishu.[24]

The Ugandan contingent operates two medical units on the AMISOM base camp: a hospital primarily reserved for AMISOM soldiers, Somali government soldiers, and staff working with the AU, and another, known as the outpatient department, which is open to the Somali public twice a week.[25] Similarly, the Burundian contingent’s base has an outpatient department that is open to the public twice a week.

On the AMISOM base camp, the soldiers are housed in tents while high-ranking officers are either housed in prefabricated structures or within office buildings. Some of these buildings were built for the purpose of hosting AMISOM whereas others were pre-existing structures.[26]

Many Somalis work on the AMISOM base camp and the MIA compound, including as cleaners, construction workers, and interpreters.[27] The UN and other international agencies have restricted access for Somalis, particularly women, to their compounds.[28] There are also shops inside the base camp and in the airport, primarily run by Somali women selling a whole range of goods including electronics, clothing, and food. One of the busiest areas is the “Marine” Market area at the northern side of the airport runway, which is controlled and regulated by AMISOM, and previously primarily by the UPDF, and accessed through a separate gate, Marine gate.

II. Sexual Abuse and Exploitation by AMISOM

Human Rights Watch documented twenty-one incidents of sexual exploitation and abuse by AMISOM soldiers occurring primarily on two AMISOM bases in Mogadishu: the AMISOM base camp largely controlled by the UPDF and the base camp of the BNDF contingent at the compound of the Somali national university.

While Human Rights Watch’s research did not find a pattern of abuse that could be considered systematic, and its researchers did not investigate all locations where AMISOM forces are deployed, the findings raise serious concerns about abuses by AMISOM soldiers against Somali women and girls. Survivors of assault and exploitation said that they felt powerless, feared retaliation or retribution, as well as the stigma and shame that the abuse could bring, while others did not want to lose their only source of income.

Human Rights Watch’s findings corroborate and expand upon previous reports by UN agencies and the Security Council Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea (SEMG), which noted that allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse “continue to emerge.”[29]

Rape and Sexual Assault by AMISOM Soldiers

Human Rights Watch documented 10 separate incidents of rape and sexual assault by AMISOM personnel. Seven women and girls described being raped and one girl being sexually assaulted by AMISOM soldiers on the two camps in Mogadishu. In one case, the woman said that a soldier raped her and that soldiers gang raped three other women who were with her at the same time. Human Rights Watch documented two other cases—an alleged gang rape of a woman at Maslah camp, the UPDF base in north Mogadishu, and a case of child rape on the outskirts of Baidoa town by a Ugandan soldier. With one exception, all the cases occurred in 2013 and 2014.

In all the incidents documented in this report, Somali intermediaries, often men allegedly working as interpreters either at the entrance of the base camps or in the camp hospitals facilitated soldiers’ access to the women and girls. In most of these cases, soldiers raped women and girls who were trying to access medicine or humanitarian services at the Burundian contingent’s base near an area of Mogadishu known as X-Control.

In late 2013, 15-year-old Qamar R. went to the Burundian X-Control base to get medicine for her sick mother.[30]An interpreter told her to follow two Burundian soldiers who would give her the medicine. She followed them to a remote area similar in structure to a military bunker behind a thick fence, and one of the soldiers proceeded to rape her, while the second one walked around. She told Human Rights Watch: “First he ripped off my hijab and then he attacked me.” As she was leaving, the second Burundian soldier waved her to come over to him and gave her US$10.

Other women who were raped also said that the soldiers gave them food or money after the attack in an apparent attempt to frame the assault as transactional sex and to discourage the women from complaining to authorities. In January 2014, Ayanna S., a displaced person, went to the Burundian X-Control base on a Monday to get medicine for her sick baby.[31] A Somali interpreter working at the base told her to come back alone without her baby. When she returned the next day that the outpatient clinic was opened to the public, the same Somali man called her and three other young women over to a fenced area next to some sandbags. There, six uniformed Burundian men were waiting. Ayanna S. said the soldiers held them at gunpoint, dragged them into a bunker area, and threatened them. The Burundian soldiers then beat and raped the women, badly injuring one.

“We carried the injured woman home. Three of us walked out of the base carrying her,” said Ayanna S. “She couldn’t stand. She couldn’t put weight on her leg. The Burundians were still there as we were leaving. They gave us porridge, cookies, and five [US] dollars, but they didn’t say anything to us, they threw the items at us and a bag to put them in. We carried them with the girl. We never got our prescriptions.” [32]

In another case, a Somali girl was raped after a soldier first tried to pay her to have sex. In June 2013, Aziza D., 17, was approached by her neighbor, an AMISOM interpreter, to befriend Ugandan soldiers in exchange for goods.[33] The interpreter did not explicitly tell Aziza D. that she would have to have sex with the soldier, but said she had to treat the soldier “like he was her husband” and “make him feel comfortable.”[34] She agreed and the next morning she went with him to the Ugandan base near the airport.

Aziza D. explained what happened on the base:

I saw four other girls as I waited. Each girl was led to a different tent by the interpreter. The interpreter introduced me to a much older Ugandan soldier. I told the interpreter I was having second thoughts and wanted to leave but he said I couldn’t since my face was already shown inside the base, I would not be permitted to leave.

Aziza D. said she started to cry and pleaded with the interpreter not to leave her alone with the Ugandan soldier, but he did. When she resisted the soldier’s attempts to have sex with her, he became angry and brought back the interpreter who then verbally threatened her in Somali. Ultimately, she felt she had no choice but to have sex with the soldier. Afterwards, she was given $10 and a bag of apples: “I did it because I was threatened.... It was either do as he wants or die.”[35]

Sexual Exploitation by AMISOM Soldiers

Human Rights Watch documented cases that suggest a relatively organized system of sexual exploitation taking place on both the AMISOM base camp and the base of the Burundian contingent in Mogadishu. These are areas in which AMISOM forces are responsible for security. Given entrenched poverty, limited humanitarian assistance, and dire living conditions, especially for displaced communities, some Somali women and girls are compelled to engage in sex with soldiers in exchange for money, food, and medicine. The AUC Code of Conduct, with which AMISOM troop-contributing countries are required to comply, prohibits sexual exploitation and abuse (see AU, AMISOM Response to Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Allegations).[36] Similarly, the MoUs signed by the AU and the UPDF and BNDF describe sexual exploitation and abuse as serious misconduct.[37]

Women and girls told Human Rights Watch they traded sex for money and goods as a last resort, often as their families’ sole breadwinner.[38] The AMISOM troops have a significantly higher income and access to goods than many Somalis living in the vicinity of the camps, particularly displaced persons. Individual soldiers deployed within AMISOM are supposed to receive over $1,000 a month in allowances, with approximately $200 being deducted by troop-contributing countries.[39]

Given the extreme vulnerability of these women and the differential power relationship between them and the soldiers, this conduct is clearly “sexually exploitative” as defined by the UN secretary-general’s 2003 Bulletin on special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse.[40]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 14 Somali women and girls, all of them displaced, who said AMISOM soldiers paid them for sex since 2013 on the Burundian contingent’s base or the AMISOM base camp in Mogadishu.[41]

As in the cases of rape, most of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch involved a Somali intermediary, often claiming to be an interpreter working on the base, recruiting women and girls directly from IDP camps or when they came to the base seeking medicine or other services.[42] Most of the cases documented took place on the Burundian contingent’s base.[43] Several of the women and girls working on the AMISOM base camp reported being lured in by female acquaintances, some of who were already having paid sex with the soldiers, who would then put them in touch with a male Somali intermediary. In many cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the Somali intermediary or interpreter would then pair the woman or girl with a specific AMISOM soldier with whom she would have sex for money, frequently over a period of weeks or months. Human Rights Watch also interviewed women and girls who regularly, sometimes on a daily basis, came to the Burundian base and had paid sex with several soldiers.[44]

Kassa. D., 19, had sex with Ugandan soldiers because she was unable to pay for food.[45] In May 2013, her friend took her to the base and introduced her to a Somali interpreter. She explained her predicament: “I was worried, I wanted to run but I knew that the same thing that brought me here would get me through this—my hunger. I had made a choice and I couldn't turn back now.” After the sexual intercourse, the interpreter paid her $10 and took her to the gate. When Human Rights Watch interviewed Kassa D., she had been having paid sex with the same soldier for six months.

In addition, witnesses including a former AMISOM civilian contractor, said that some women having paid sex lived inside the AMISOM base camp.[46]

Amina G., 18, has been the family breadwinner since her father was killed in an explosion in 2010 and her mother fell seriously ill.[47] She is the sole provider for two younger sisters. She told Human Rights Watch how she was sexually exploited on the Burundian contingent’s base in early 2013:

A neighbor put me in touch with a Somali man working at the Burundian base. He agreed to meet me after asking me what I looked like and if I was a virgin. He did not fully describe what I would have to do until I came to the base. He said that I would have to befriend powerful foreign men who could help me get money, food and medicine.

I would enter the base through a separate side entrance at 6 a.m. that was used mainly by me and the three girls that I worked with. The youngest girl was 16. The interpreter paid us between $3 and $5 a day and would coordinate the visits by taking us between the soldiers’ rooms. At the end of the day, the intermediary would escort us out.

All the men were foreigners—Burundi military officers. They all wore similar green camouflaged uniforms and had stripes on their epaulets. Some men had three stripes, others had four, but they all looked like powerful men.

The increasing number of shops on the AMISOM bases in Mogadishu also provided greater interaction between AMISOM personnel, soldiers, and Somali women. Several people living and working on the airport compound said that some of the women having paid sex with the Ugandan soldiers were based in the shops in the Marine market, located in Afisyoni at the northern part of the airport runway, and other shops in the AMISOM base camp, between the AMISOM officers’ mess [canteen] and the hospital area during the day.[48] One foreign diplomatic advisor said: “The women are hiding in the back of the small shops. The soldiers go there with the excuse to buy SIM cards. Everyone is aware of this.”[49] The women are sometimes brought to the soldiers’ prefabs [prefabricated residences] that are nearby.

In December 2012, following media reports of shops on the AMISOM base camp being used as a front for exploitative sex, the then-AMISOM force commander, Ugandan Gen. Andrew Gutti, ordered the closure of shops near the soldiers’ quarters, banned Somali women from the base camp, and ordered the shops to be moved to the Marine market area.[50] According to a Somali civilian contractor working on the base camp at the time, most shop owners refused to relocate. In addition, as described above, taking such measures may have merely relocated the problem to a new area.

The nexus between shops and sexual exploitation on the bases was also highlighted by a woman working on the Burundian contingent’s base. Ifrah D. told Human Rights Watch:

I ran a small shop outside the Burundian contingent base. In August 2013, a Somali interpreter introduced me to a Burundian soldier. He helped me to set up a little shop inside the base selling mobile phones. I knew what I was agreeing to. The soldier is a man of power, not like the other soldiers. My shop has become much more profitable. I visit [have sex with] the man occasionally. I consent to his requests.[51]

Coercion and Threats

Women and girls also described how violence could become part of these relationships. One day, the soldier with whom Kassa D. was having paid sex got angry because she did not want to perform fellatio as she had a sore tooth. “I tried to explain to him using hand gestures, but he became infuriated and forced me to perform the act anyway,” she said. “I felt so scared and thought he would shoot me with his pistol.”[52]

Anisa S., 19, said both the Burundian soldiers with whom she had paid sex had been violent to her, including hitting and slapping her on several occasions. [53] She was recruited while seeking water on the base and had never had sex before. She agreed to the arrangement because she was the sole provider for her elderly and sick grandmother and she was in debt.

Women’s Access to the AMISOM Bases

|

While in line [for medicine at the Burundian X-Control base], an interpreter approached me and said he wanted to introduce me to a senior Burundian military officer who would be able to help me. He gave me his number, told me to come back wearing a burqa the next time and said he would meet me at the gate of the side entrance. After thinking it over, I went back to the base. He took me to an area of the base I had not seen before, with a lot of tents and large military vehicles. He introduced me to a Burundian man of about 40 or 50, then left me alone in a room which I think was his room. My baby was given toys to play with. The man undressed himself and we had sex; the baby cried twice and the soldier seemed annoyed by it. When it was finished, I received my medication, $10 and some food. On later visits I saw six other Somali women there—about six regulars between 15 to 24-years-old. —Deka R., Mogadishu, September 2013 |

As documented by Human Rights Watch and the SEMG, the sexual exploitation by Ugandan soldiers at the AMISOM base camp and by Burundian soldiers at the Burundian contingent’s camp appears routine and organized. This heightens the likelihood that others living and working on these bases, including international and AU staff, are aware of the problem.[54] Somali women having paid sex with soldiers have been able to obtain AMISOM badges allowing them easy access in and out of what should be highly secure military zones.[55] Even those without badges are able to access the bases. Some Somali women having paid sex with soldiers have also resided in housing on the base camp.[56]

Once recruited, these women and girls who normally did not cover their faces would frequently wear burqas on their way to the bases to conceal their identity. The Somali intermediaries then facilitated access to the bases, almost exclusively via side entrances. In the case of the AMISOM base camp, they entered via the side entrance gate near the outpatient department.[57] Most of the women and girls told Human Rights Watch that they accessed the base via official, guarded side entrances in the early morning and were often searched by AMISOM female officers at the entry points. Fatima W. said she was not checked upon entering the Burundian base camp because of her frequent visits: “We’re known by the Burundians so we’re not checked.”[58]

One woman said she was picked up directly at the gate by a Ugandan soldier with whom she regularly had paid sex who was in an AMISOM vehicle.[59] One woman, Farxiyo A., told Human Rights Watch that she was given an ID card by the Ugandan soldier she was having paid sex with to facilitate her access through the main airport entrance.[60]

According to a Somali civilian official who worked at the Halane base in 2012 and 2013, and was well acquainted with other Somalis on the base, about eight Somali women who had paid sex with senior officers lived inside the base in prefabricated residential units.[61] The women had official AMISOM contractor badges and ostensibly worked as overnight interpreters at the hospital and daytime interpreters at the outpatient department hospital.

“There is a lot of corruption in AMISOM that allows the women to get these badges,” the Somali official told Human Rights Watch. “Everyone knows that exploitation is happening but no one wants to address it unless the information becomes public—it’s seen as a way of pleasure for soldiers.”[62]

According to a UN official, the UN and diplomats based in the airport compound have on at least one occasion raised concerns with AMISOM officials about the security implications of Somali women carrying AMISOM identity cards around the airport compound.[63] The official did not know what, if anything, had changed as a result.

Human Rights Watch’s research suggests that access to commanders was primarily facilitated by interpreters. As a Somali working on the airport compound said: “The top commanders rely on the translators and the ordinary soldiers rely on their own ways.”[64]

The women said that once inside, most went straight to the soldiers’ quarters. While the women were reluctant to give the exact locations of where they were taken, some described being taken to tents and others said they were taken to more permanent structures.

While the payment varied, the women having regular paid sex with one soldier said they were typically paid around $5 a day but pay ranged from between $3 to $20 a day. Occasionally the soldiers would supplement money with apples, milk, and food cooked on the base. Other times, the women would get medicine or other supplies from the soldiers or interpreters.

In July 2013, a Somali interpreter at the Ugandan base recruited Idil D., 18, after meeting her near the IDP camp where she lives in Suqhoola in the Huriwa district of northern Mogadishu.[65] He lured her by saying that if she befriended a Ugandan soldier and he fell in love with her, he would take her to Uganda. Idil said: “I agreed, because I really wanted to leave Somalia.”[66]

That same day, the interpreter took her to a room on the AMISOM base camp to meet the Ugandan soldier. “At first I was scared of the soldier. He was old enough to be my father. I was nervous, but I really wanted to be sent to Uganda.”[67] After having sexual intercourse, he paid her $20. She had paid sex with the same soldier at the base three times a week for a month. She met five other women at the base who also had similar relationships. In August, the soldier left Somalia without her and never returned.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Women and service providers who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that soldiers paying for sex on the two bases did not consistently wear condoms, placing women at serious risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Several women said they had contracted STIs, primarily gonorrhea, after having sex with soldiers at the bases. Others did not know their health status as they had not been tested. Idil D. said she constantly worried because the soldier she had sex with for money never used a condom. She has not been tested: “I do not want to know if I have AIDS. If I have it, I will go crazy.”[68]

Anisa S., a 19-year-old living in the X-Control IDP camp, has had various health problems including gonorrhea since starting to have sex with soldiers at the Burundian contingent’s base in April 2013.[69] Ayan Y. also discovered she had gonorrhea after having sex with a Burundian soldier without a condom for three months; when she told the interpreter, he gave her $5 to go and buy pills.[70]

Fear of Reporting

With two exceptions, rape survivors interviewed by Human Rights Watch did not file complaints with authorities because they feared stigma, reprisals from family, police, and the Islamist insurgent group Al-Shabaab. Others did not believe authorities would be able or willing to take any effective action. They said they felt powerless.

Farha A., 18, was raped in late December 2013 at the Burundian contingent’s base after going to the AMISOM base to beg.[71] She said she did not report the rape to anyone because she feared reprisals from the soldier.

Even in cases where Somali police suspect misconduct by AMISOM soldiers and want to investigate, they have no jurisdiction over the troops (see AU, AMISOM Response to Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Allegations).

Iftin D. said she was 16 when she was sexually assaulted after going to the Burundian base seeking food.[72] As she was being attacked by four Burundian soldiers she started screaming loudly causing two Somali policemen to come to the gate.

Shots were fired in the air and the soldiers let Iftin D. go. Iftin D. said, “The police asked me what I was doing inside. I told them that [the soldiers] had promised me food and then attacked me. The police didn’t say anything. They just helped me home.”[73]

Both Somali and international officials said that their lack of physical access to certain areas of the AMISOM base camp controlled by the UPDF hampered their ability to monitor abuses in those areas and investigate incidents.[74] A high-level police officer who worked for several years on the airport compound said that the Somali authorities and independent monitors should be given access to these areas.[75]

In the high-profile case of a woman who did exceptionally report her rape by AMISOM soldiers, the investigation was deeply flawed and the woman and the organization providing her with services faced harassment (see AU, AMISOM Response to Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Allegations).

Some women did not report their experiences because they felt that Somali authorities might do more harm than good. The women feared that the authorities would not do anything but stigmatize them or bring them other problems, including criminal prosecution. Under Somalia’s 1962 penal code, sex work carries a prison sentence of between two months and two years, with an even harsher sentence for sex workers who are married.[76] “I am ashamed to go to the police and there is no proof,” said Idil D. “It's my word against theirs. The police will only tell more people and arrest no one. There’s no point.”[77]

Mariam K., 26, who worked on the AMISOM base camp said: “I fear the police would arrest me if I told them.”She was also fearful about the ramifications of the information about her exploitation becoming public. “If my parents or my brothers back home found out what I was doing they may kill me, because Somali people traditionally believe if a girl sells her body, she damages the dignity of her family.”[78]

Many of the women and girls told Human Rights Watch they also feared reprisals by Al-Shabaab. A female cleaner working for years in the MIA, who knew many of the women selling sex on the base, summarized the women’s concerns: “They provide free sex to get food and so on, but what I can tell you is that they are very desperate and they fear Al-Shabaab will kill them. Even their families and relatives may kill them, because they believe they destroyed their honor.”[79]

Idil D., who had been lured by promises of living in Uganda, faced threats as a result of her previous work on the base. She told Human Rights Watch:

After I confided to a girlfriend, people in my community found out that I was visiting the Ugandan base. I received harassing phone calls from people who said they were connected to Al-Shabaab, and they threatened to kill me for associating with AMISOM. My father kicked me out the house. I felt betrayed and depressed after learning the soldier had left the country without me. I did all these things for my future but now I am ruined and I will never be the same. I can’t get married now, everyone knows what I did. No one wants to be around me. My reputation is ruined forever. [80]

III. Jurisdiction over Abuses by AMISOM Forces

States are obligated to ensure that serious violations of human rights committed within their territory are impartially and credibly investigated and appropriately prosecuted. Under the status of mission agreement between the Somali government and the AU, Somalia relinquishes jurisdiction over AMISOM troops who commit crimes on Somali territory, including sexual abuse and exploitation. Primary responsibility falls on troop-contributing countries to hold members of their forces to account for misconduct, including through criminal prosecutions, as specified by status of mission agreements between Somalia and the AU, and individual MoUs between troop-contributing countries and the AU.

Under the Somalia-AU status of mission agreement, all members of AMISOM, including locally recruited Somali personnel, are therefore legally immune from prosecution in the local Somali justice system for all acts performed in their official capacity.[81] Troop-contributing countries have exclusive jurisdiction in prosecuting any criminal offenses committed by their troops in Somalia.[82] AMISOM and troop-contributing countries effectively take primary responsibility for ensuring that as their personnel carry out their mission, they respect the rights of the civilian population.

Soldiers of troop-contributing countries have no individual contractual link with the AU and remain administratively attached to their respective national militaries. Legal obligations of military personnel in AU peace support operations are governed by MoUs agreed to between the AU and each troop-contributing state. These MoUs hold troop-contributing countries responsible for the training and discipline of their forces and for holding their forces to account for misconduct, including through criminal prosecutions.[83]

According to the AMISOM MoUs with troop-contributing countries, governments shall ensure that all members of their contingents comply with the AUC Code of Conduct and discipline.[84] As described below, the AUC Code of Conduct specifically prohibits sexual exploitation and abuse, although it does not define such conduct.

The AMISOM troop-contributing countries’ MoUs are not identical when defining sexual exploitation and abuse. For example, the Burundian MoU seen by Human Rights Watch specifically defines sexual abuse and exploitation whereas the Kenyan and Ugandan MoUs do not.[85] However, all explicitly state that sexual exploitation and abuse constitute serious misconduct.[86] Where investigations conclude that there are well-founded allegations of misconduct by any member of their national contingent, the respective government should forward the case to the appropriate authorities in the troop-contributing country for action.[87]

Significantly, the MoUs also empower the AU to initiate investigations into allegations of abuse and exploitation where the troop-contributing country is unable or unwilling to do so itself.[88]

AMISOM’s responsibilities to prevent and to protect women and girls from sexual exploitation and abuse is affirmed in UN Security Council Resolution 2093, which requests AMISOM “to take adequate measures to prevent sexual violence, and sexual exploitation and abuse, by applying policies consistent with the United Nations zero tolerance policy on sexual exploitation and abuse in the context of peacekeeping.”[89]

UN Security Council Resolution 2124 also requests the AU “to advance efforts to implement a system to address allegations of misconduct.”[90] The resolution also notes that expanded logistical support for AMISOM should be consistent with the requirements of the secretary-general’s Human Rights Due Diligence Policy.[91] Under this policy, support by all UN entities to non-UN security forces cannot be provided where there are substantial grounds to believe the recipient may commit grave violations of international humanitarian,human rights, or refugee law and where the relevant authorities fail to take the necessary corrective or mitigating measures to prevent such violations.[92] Under the policy, should the UN receive reliable information that a recipient is committing such violations, the UN entity providing this support must intercede with the relevant authorities with a view to bringing those violations to an end. If the situation persists despite the intercession, the UN is then obliged to suspend or withdraw support as a last resort.[93]

IV. Troop-Contributing Countries and Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

Troop-contributing countries to AMISOM are responsible for holding their forces to account for and preventing sexual exploitation and abuse. There are a range of actions and procedures that troop-contributing countries—particularly Uganda and Burundi—have taken to tackle abuses and misconduct by their forces. However, troop-contributing countries have not made sexual exploitation and abuse a priority or proactively deployed resources at their disposal to tackle the problem.

Ensuring Accountability for Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

Tackling impunity and ensuring accountability for acts of sexual exploitation and abuse is key to addressing the problem. Thorough and prompt in-country investigations aimed at gathering sufficient and proper evidence would improve the likelihood of pursuing prosecutions of perpetrators.

Holding on-site or in-country courts martial can also facilitate evidence gathering, help ensure that witnesses are available to testify, and increase a victim’s belief that justice has been served. This means ensuring that survivors and their relatives not only participate as witnesses during the investigation and at trial but are kept informed throughout the judicial process.

Regular outreach within affected communities to update them about any investigations and outcomes is also important. Given both the immediate medical impact on survivors and the longer-term psychological, medical, social, and economic consequences they face, troop-contributing countries should also ensure that they assist and compensate via suitable third parties, such as AMISOM or humanitarian agencies, victims of sexual abuse and exploitation.

Ensuring that information on complaints, investigations, prosecutions, and their outcomes is shared by troop-contributing countries with the AMISOM headquarters and the African Union Commission, and made public as appropriate, can also help improve transparency, accountability, and improve oversight by AMISOM.

Investigations and Prosecutions

Troop-contributing countries have deployed, to a varying degree, legal officers, military investigators, and intelligence officers to Somalia in order to investigate misconduct by their troops.[94] However, current and former military justice officers and other military officials previously deployed to Somalia told Human Rights Watch that the legal and investigation capacity is insufficient, and this has negatively affected investigations and prosecutions.[95] They said inadequate investigations and poorly assembled criminal files are among the main reasons why prosecutions often end up in acquittal.[96] Legal advisors to troop-contributing countries also raised concerns that because of the limited number of legal officers deployed to address the problem in each contingent, the risks of incidents not coming to their attention or of cover-ups by commanders remained high.[97]

Human Rights Watch identified only two investigations into allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse since 2012 (see Criminal Investigations into Rape of Girl in Baidoa below).

The legal officer with the Burundian contingent in Mogadishu in early 2012 took part in a preliminary investigation into an allegation of rape of a 16-year-old girl by Burundian soldiers after the girl’s relatives made an oral complaint to the contingent headquarters.[98] The legal officer told Human Rights Watch that his office interviewed the girl and a few witnesses at the location of the incident who said that the family was fabricating the complaints because the girl’s mother wanted access to medical care. The investigators never compiled a formal file on the case and closed the investigation before receiving the results of the medical examination.[99]

Military justice officers identified a range of factors impeding investigations into sexual exploitation and abuse issues, including the lack of both complaints and evidence. A Burundian military prosecutor summed up the obstacles as follows: “I don’t know of any cases of prostitution or rape. But I don’t exclude that there could be cover-up on these issues by commanders. These types of offense are rarely known. They are also difficult to investigate.”[100] The officers also appear to lack the means to carry out thorough investigations, and possibly also the legal knowledge to investigate sexual exploitation and abuse. Several legal officers said they heard rumors about sexual exploitation and abuse during their tenure, but as one stated, he “never received official complaints or found soldiers or officers in ‘flagrante delicto’ [caught in the act].”[101]

Such expectations are unreasonable given both the reluctance of survivors to file complaints as well as the unlikelihood of catching soldiers or officers in the act. This also highlights a lack of understanding about the conduct of investigations into sexual exploitation and abuse as legal officers and military prosecutors need to proactively seek evidence, including by interviewing witnesses and gathering forensic evidence. Furthermore, when asked where women and girls subjected to such abuses could report a complaint, legal officers and senior military officials responded that they could just “come to the bases”; while some survivors may choose to do so, it is unlikely given the military environment, as well as the fear of reprisals from the perpetrators, that women would choose the bases as their first option.[102]

Military Justice

The majority of cases that appear before the Ugandan and Burundian military courts have focused on military offenses not involving civilians, with a few exceptions of incidents of killings of civilians.[103]

The Burundian military has not held any courts martial in Somalia.[104] The Ugandan military, however, held trials by a resident Divisional Court Martial (DCM) in Mogadishu between January and October 2013. [105] Prior to this, the court had been travelling to Mogadishu on occasion as required.[106] During this period the court concluded 30 cases, which was an important step forward toward greater accountability, though none of the cases concluded related to sexual abuse.[107] In October 2013, the on-site DCM was disbanded, and all pending files were brought back to the General Court Martial in the Ugandan capital, Kampala.

Human Rights Watch was not able to determine why the court was disbanded. Some sources mentioned the cost of maintaining the court in Mogadishu, while others cited possible concerns that the Ugandan military would be seen in a negative light if it was the only contingent holding on-site courts martial.[108] One court official speculated: “I think they moved it back [to Kampala] as they were worried that having a court in Mogadishu would highlight the criminality within the UPDF, publicize it.”[109] Certain court officials acknowledged that having the hearings in Kampala was likely to impede justice: “The DCM [in Mogadishu] was a good move. The biggest issue in trying the cases [in Kampala] will be getting the witnesses. If the witnesses don’t appear in court, the cases will be thrown out.”[110]

Overall, military court judges, prosecutors, and lawyers in troop-contributing countries interviewed by Human Rights Watch acknowledged that having courts martial in Mogadishu would be a positive step.[111] One former legal advisor to the BNDF said, “In the current set-up, the lack of evidence evidently benefits the accused.”[112]

Officials deployed to Somalia prior to 2012 told Human Rights Watch that they were not aware of any allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse that had resulted in a board of inquiry or a criminal prosecution.

Criminal Investigations into Rape of Girl in Baidoa

Human Rights Watch research identified only one case of sexual abuse that went before a national military court since 2012.[113]

According to Ugandan military prosecutors, judges, and lawyers involved in the case, the Special Investigation Branch (SIB) of the military intelligence conducted an investigation into allegations of rape of a girl by a Ugandan soldier, which reportedly included statements from the survivor and her parents. A prosecution file was opened in July 2013. [114] The Ugandan military arrested and detained a Ugandan soldier, a private from Battlegroup 10 in the “Bikin” detachment (Bikin is a hotel on the outskirts of Baidoa). The soldier appeared before the Divisional Court Martial in Mogadishu and a hearing was set for October 2013, but then the court was called back to Uganda and the case file transferred to Kampala. [115]

Divisional Court Martial officials told Human Rights Watch that the parents of the survivor had initially been reluctant to support the prosecution, as they were hoping to get compensation.

At the time of writing, the private is still in detention in Uganda, but his case has not been heard.

One official who had been part of the Divisional Court Martial in Somalia was skeptical about the outcome of this case. “I think this case will not succeed,” he said. “If the witnesses wouldn’t come to Mogadishu, how would they agree to come to Uganda?”

While Human Rights Watch was not granted access to the case file, the case appears to correspond with a case of rape of a girl in Baidoa in May 2013 investigated by Human Rights Watch.

In May 2013, a 12-year-old Somali girl from Baidoa went to work on her parents’ farm on the outskirts of the town. A Ugandan soldier approached the farm. Her mother told Human Rights Watch: “She wore a sako [long robe] and jeans under it. After tearing the jeans, he raped her, he cut her vagina, he wounded her very badly. We don’t know if he made that cut with the knife or just with himself.”[116]

The girl’s relatives told Human Rights Watch that Somali soldiers nearby intervened.[117] The girl’s parents were taken to meet with AMISOM officials, and told by the Somali interpreter that AMISOM would give them 50 camels as compensation. The local Somali authorities involved in the case told the relatives to remain silent, not talk to the media or to any nongovernmental organizations about the case, and wait for the compensation.[118] The survivor’s father told Human Rights Watch a few weeks after the incident: “I repeatedly go to AMISOM to get compensation. I have to rent a bicycle to go to the base. They tell us they have arrested the man, and now we have to wait.”

According to the girl’s mother, AMISOM called the survivor’s cousin, a witness, and the girl herself to identify the soldier. They all identified the same soldier. The girl’s parents said AMISOM never approached them about any court case. The mother however said: “A young man from AMISOM told me one time that there was a court hearing in Mogadishu about my daughter’s case, and I asked, ‘Why we were not contacted if there is a hearing?’ and he couldn’t tell me why. I can’t trust the existence of the court if I was not informed, because there must be the victim in court if they charge someone with rape.”

The girl’s mother spoke about the awful consequences for her daughter:

The rape was the beginning, but it became the source of destruction of our family. The case became well known in the city. Everyone in my family became victim of the case, because whenever we go out, people started pointing their fingers at us. My daughter was the victim who felt the physical pain and paid the price of the stigma after that.

People laugh at her whenever she comes out. They say, “An infidel raped her.” They say, “A Ugandan soldier raped her.”

How can you feel if your daughter asks you, “Mother, why do I live? Mother, do I deserve to live? Mother, I better die to hide my shameful face from the people,” and other depressing words.

Other Disciplinary Mechanisms

Boards of Inquiry

Troop-contributing countries regularly establish boards of inquiry to investigate troop misconduct when they receive credible allegations.[119] These can be simultaneous with criminal investigations, focusing primarily on facts, evidence, responsibility, and recommendations for administrative responses, including questions of material compensation and criminal investigations gathering evidence for prosecutions.[120]

Legal advisors to troop-contributing countries told Human Rights Watch of participating in boards of inquiry for a range of allegations, including cases of loss of equipment and killings of civilians. None of the legal advisors and other military court personnel interviewed by Human Rights Watch deployed to Somalia between 2012 and 2013 took part in boards of inquiry into allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse.[121]

A UN staff member who worked closely with AMISOM said that the determination to establish a board of inquiry can be highly politicized. “The troop-contributing countries want to do what is best for them,” he said. “The legal investigations happen, carried out by legal advisors, but then the sector commanders or the like make the final decisions.”[122]

Repatriations

Human Rights Watch has documented two cases of repatriations since 2012 as a result of an incident that may have involved soldiers’ procurement of prostitutes, but not for the exploitation itself.

In October 2012, the Burundian contingent repatriated two officers. The officers—a major in charge of intelligence at the contingent headquarters and a lieutenant colonel in charge of civil-military relations—had left the base for a prolonged period. They were arrested when they returned to the base by military police.[123] Several military officials told Human Rights Watch that they had received credible information that the two had left the base to meet with Somali women to have sex.[124] However, they said that as no complaints were ever filed, these claims were never investigated.[125] Within days the two officers were repatriated to Burundi on charges of “abandoning the post” and reportedly faced disciplinary measures: suspended for a month and possibly also given a posting in Burundi far from their relatives.[126]

Improving Tracking Mechanisms

Procedures whereby troop-contributing countries are to share information with AMISOM are spelled out in the AMISOM Standard Operating Procedures and also included in MoUs.[127] Legal officers said they shared the outcomes of internal boards of inquiry with the AMISOM headquarters’ legal advisors on a regular basis.[128] Specifically, files relating to questions of compensation are reportedly regularly shared as the AMISOM force commander has final sign-off on compensation claims before they are forwarded to the AU headquarters.[129]

However, others said troop-contributing countries did not share all the required information relating to misconduct, investigations, and prosecutions.[130] A former Burundian legal officer said: “There is little exchange of information with other troops, it’s as though [such cases] are an embarrassment that the forces don’t want to publicize.”[131] A UN staff member who worked closely with AMISOM said: “Soldiers have been arrested for a whole range of crimes and offenses, but the troop-contributing countries see it as highly confidential…. Most TCCs [troop contributing countries] don’t want to air their dirty laundry in public.”[132]

Preventing Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

Troop-contributing countries have taken preventive action to reduce misconduct and abuses by their forces, particularly through trainings and sensitization work. Ensuring that peacekeeping forces receive comprehensive training on relevant standards, the nature and causes of abuses, as well as consequences of violations of these standards can be an important measure for preventing such abuses. Vetting of peacekeepers to remove individuals with a record of past abuse is also important to prevent further abuses. UN peacekeeping missions have long acknowledged that a greater number of female personnel in peacekeeping improves conduct within the mission.[133] Greater numbers of female soldiers encourage local women to deposit complaints as they are also more likely to report incidents to female officers.[134] AMISOM has also recognized that female soldiers provide a “meaningful contribution to solidifying peace and security gains in any mission.”[135]

Pre-Deployment Trainings

Most of the troops that have recently been deployed to Somalia underwent a series of pre-deployment trainings.[136] Higher ranking officials and commanders are expected to undergo further specialized training, including on sexual violence, to ensure that they are able to raise awareness among troops under their command of key standards and laws, and also regarding the AUC Code of Conduct and other policies related to sexual abuse.[137]

In his response to a letter from Human Rights Watch, the Burundian chief of staff, Gen.-Maj. Prime Niyongabo, stated that these trainings are obligatory.[138] However, some legal advisors from troop-contributing countries and staff of international organizations questioned whether all troops in fact undergo the required pre-deployment trainings, and said that there was no means of guaranteeing attendance.[139] One legal advisor raised particular concerns about senior commanders dropping out of trainings, even though training of commanders is particularly essential to minimizing abuse.[140]

Dissemination of the African Union Commission’s Code of Conduct

Troop-contributing countries are disseminating the AUC Code of Conduct in national languages in card form among their troops. One Burundian legal officer said he would visit the different Burundian units in order to raise awareness of the code of conduct, and also said that he sent out the UN secretary-general’s 2003 Bulletin on special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse to units but was never able to hold discussions on it.[141] However, as with many other measures, much depends on the commitment of commanders. Legal officers questioned the capacity and willingness of the commanders to systematically remind troops of their responsibilities under these codes.[142]

Vetting

While senior military officials in Uganda and Burundi were able to describe to Human Rights Watch pre-deployment vetting on medical grounds in detail, they were unable to spell out exactly what procedures are in place to prevent individuals with a criminal file or those having faced disciplinary measures in the past from deployment to Somalia or other peace support missions.

A former Burundian legal officer said, “We were told that all officers that are repatriated could not be sent back to a peacekeeping mission, but not sure where this is written.”[143] The head of the peacekeeping department within the Burundian Chief of Staff said they keep track to make sure that people with criminal records or those who have been repatriated for misconduct are not redeployed but that ultimately the decision is taken at the level of the chief of staff. [144] One military court official in Burundi said: “Some people with pending cases before the military court in Bujumbura have been sent to Somalia.” The head of legal services of the Ministry of Defense in Uganda insisted: “We do vet, look at files, we don’t want to include people with a bad track record.”[145]

Enhancing the Presence of Women within AMISOM

So far female representation within AMISOM is minimal. While there is little accurate data on female representation, a report by the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) found that only about 1.5 percent of AMISOM’s military personnel are women.[146] Out of the troop-contributing countries, the report states that the UPDF has the highest percentage of women deployed in its forces to Somalia: in 2013, 3.1 percent of its forces were women, while the BNDF had fewer than 1 percent.[147] Officials and members of the BNDF said that the limited number of women within the BNDF made a significant increase of women among its peacekeeping forces very difficult.[148]

Women tend to be confined to administrative or assistance roles. With the exception of one legal advisor sent by the UPDF in 2013, Human Rights Watch found that all other legal advisors sent by Uganda, Burundi, and Kenya have been men.

V. AU, AMISOM Response to Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Allegations