Paramilitaries’ Heirs

The New Face of Violence in Colombia

Glossary

AUC: Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia,United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, a coalition of 37 paramilitary groups in Colombia that officially demobilized by 2006.

Colombian National Police, Division of Carabineers: Dirección de Carabineros de la Policía Nacional de Colombia, a division of the National Police that operates in rural regions and is tasked with confronting successor groups, as well as with providing security for eradication of illicit crops.

ELN: Ejército de Liberación Nacional, National Liberation Army, a left-wing guerrilla group.

FARC: Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, Colombia’s largest left-wing guerrilla group.

MAPP/OAS: Organization of American States’ Mission to Support the Peace Process in Colombia, a mission established in 2004 as part of an agreement between the Organization of American States and the Colombian government to monitor and verify the demobilization of the AUC paramilitary groups.

Office of the Attorney General of Colombia: Fiscalía General de la Nación, a Colombian state entity charged with conducting most criminal investigations and prosecutions. The Office of the Attorney General is formally independent of the executive branch of the government.

Office of the Inspector General of Colombia: Procuraduría General de la Nación, a Colombian state entity charged with representing the interests of citizens before the rest of the state. The office conducts most disciplinary investigations of public officials and monitors criminal investigations and prosecutions, as well as other state agencies’ actions.

Early Warning System of the Office of the Ombudsman of Colombia: Sistema de Alertas Tempranas de la Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia. The Ombudsman’s Office (or Defensoría) is a Colombian state entity charged with promoting and defending human rights and international humanitarian law. The Early Warning System is a subdivision of the Ombudsman’s Office, charged with monitoring risks to civilians in connection with the armed conflict, and promoting actions to prevent abuses.

Permanent Human Rights Unit of the Personería of Medellín: Unidad Permanente de Derechos Humanos de la Personería de Medellín. The Personería is a municipal entity that is also an agent of the Public Ministry, and is charged with monitoring human rights and citizens’ rights in the city of Medellín. The Medellín Personería’s Permanent Human Rights Unit is a division of the Personería specifically charged with monitoring and protecting human rights in the city.

Presidential Agency for Social Action and International Cooperation (Social Action): Agencia Presidencial para la Acción Social y la Cooperación Internacional (Acción Social), a Colombian state entity that is charged with administering national and international resources for the execution of social programs for vulnerable populations under the authority of the Presidency of Colombia. Among other functions, Social Action oversees the registration of and assistance to internally displaced persons.

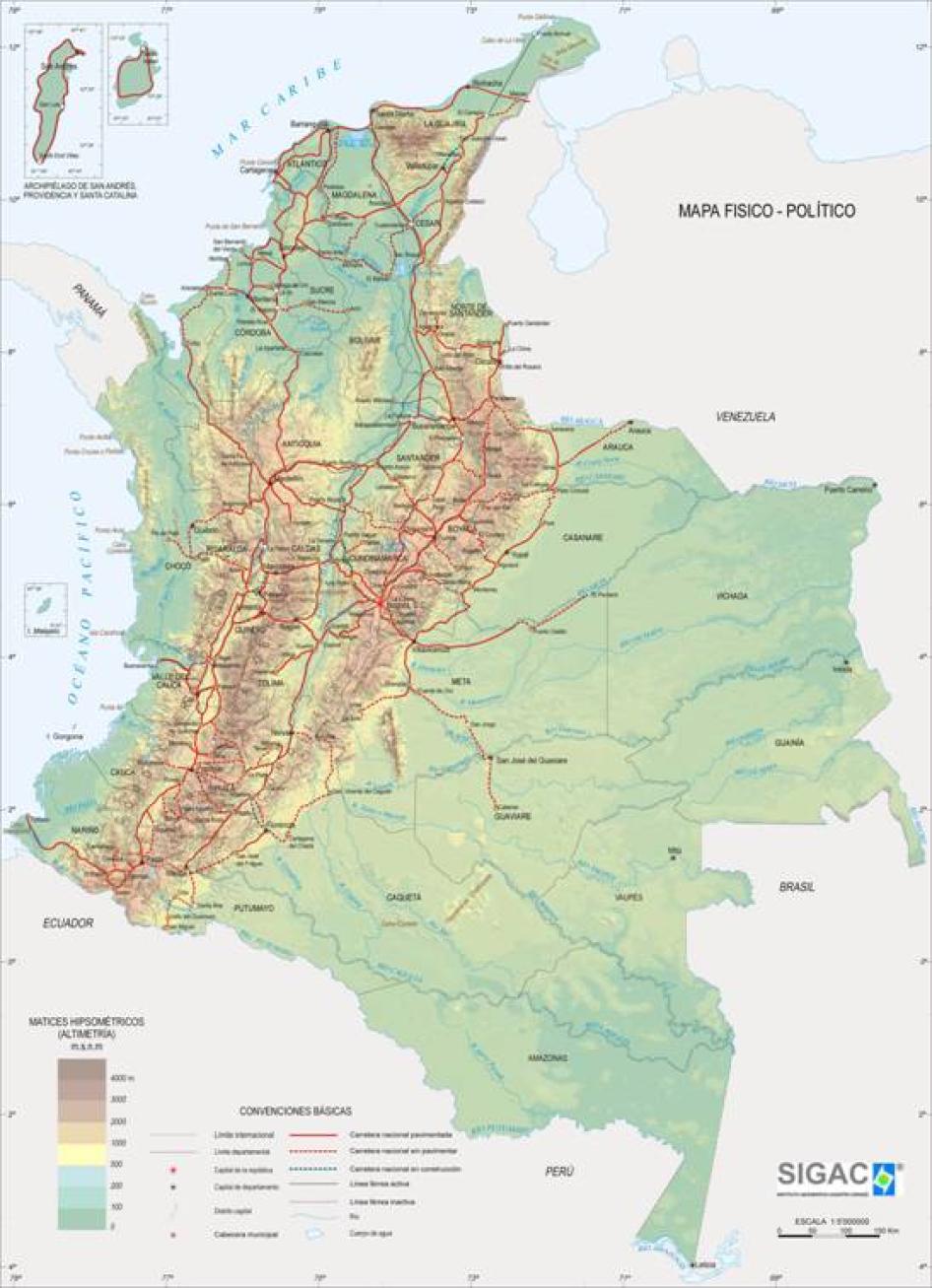

Map of Colombia

I. Summary and Recommendations

Between 2003 and 2006 the Colombian government implemented a demobilization process for 37 armed groups that made up the brutal, mafia-like, paramilitary coalition known as the AUC (the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia, or United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia). The government claimed success, as more than 30,000 persons went through demobilization ceremonies, pledged to cease criminal activity, and entered reintegration programs offering them training, work, and stipends. Since then, the government has repeatedly said that the paramilitaries no longer exist.

But almost immediately after the demobilization process had ended, new groups cropped up all over the country, taking the reins of the criminal operations that the AUC leadership previously ran.

Today, these successor groups are quietly having a dramatic effect on the human rights and humanitarian situation in Colombia. Of particular concern, as documented extensively in this report, the successor groups are engaging in widespread and serious abuses against civilians, including massacres, killings, rapes, threats, and extortion. They have repeatedly targeted human rights defenders, trade unionists, displaced persons including Afro-Colombians who seek to recover their land, victims of the AUC who are seeking justice, and community members who do not follow their orders. The rise of the groups has coincided with a significant increase in the rates of internal displacement around the country from 2004 through at least 2007. And in some regions, like the city of Medellín, where the homicide rate has nearly doubled in the past year, the groups’ operations have resulted in a large increase in violence. To many civilians, the AUC’s demobilization has done little to change the conditions of fear and violence in which they live.

The threat posed by the successor groups is both serious and steadily growing. Colombia’s National Police estimates that they have more than 4,000 members. Non-governmental estimates run as high as 10,200. According to conservative police figures, the groups are quickly increasing their areas of operation and as of July 2009 had a presence in at least 173 municipalities in 24 of Colombia’s 32 departments. They are actively recruiting new members from among teenagers, demobilized individuals, and young men and women. In several cases, they have been known to recruit members from distant regions of the country, displaying a high level of organization at a national level. Increasingly, the successor groups have merged or have absorbed one another, so that fewer groups are operating in a more coordinated manner, covering a larger territory.

The police speak of eight major groups: the Urabeños, the Rastrojos, ERPAC, the Paisas, the Machos, New Generation, the group from the Magdalena Medio, and Renacer. Human Rights Watch also received credible reports of the existence of other groups, such as the Black Eagles in Nariño, which the police did not include in their list at the time.

A serious cause for concern is the fact that many eyewitnesses with whom we spoke reported that members of the security forces were tolerating successor groups’ activities in various regions.

The Colombian government and some analysts label the successor groups as “emerging criminal gangs at the service of drug trafficking” (bandas criminales emergentes or BACRIM), insisting that the successor groups are something new and very different from the paramilitaries. Other experts and many residents view them as a continuation of the AUC, or a new generation of paramilitaries.

Regardless of how the successor groups are categorized, the fact is that today they are frequently targeting civilians, committing horrific crimes including massacres, killings, rapes, and forced displacement. And the state has an obligation to protect the civilian population, to prevent abuses, and to hold perpetrators accountable.

Unfortunately, the government has yet to take strong and effective measures to fulfill these obligations. It has failed to invest adequate resources in the police units charged with combating the groups, or in the group of prosecutors charged with investigating them. It has done far too little to investigate regular reports of toleration of the successor groups by state agents or public security forces. And it has yet to take adequate measures to protect civilians from this new threat. Instead, the government has dragged its feet on funding for the Early Warning System of the Ombudsman’s Office, which plays a key role in protecting the civilian population, and state agencies have at times denied assistance to civilians who reported being displaced by successor groups.

This report addresses three main issues. First, it documents the extent to which the emergence of the successor groups is related to the government’s failure to effectively demobilize many AUC leaders and fighters. Second, it describes the groups’ frequent and brutal abuses against civilians, highlighting common patterns of behavior with particular attention to four regions where the groups have a substantial presence: the city of Medellín, the Urabá region of Chocó state, and the states of Meta and Nariño. Third, the report points out continuing shortcomings in the government’s response to the groups’ operations and abuses.

The report is based on nearly two years of field research in Colombia. Human Rights Watch conducted dozens of interviews with victims, demobilized paramilitaries, local and national law enforcement authorities and state agencies, members of the public security forces, and non-governmental organizations in the following regions: Sincelejo (Sucre); Barranquilla (Atlántico); Pasto and Tumaco (Nariño); Cúcuta (Norte de Santander); Barrancabermeja and Bucaramanga (Santander); Medellín (Antioquia); Villavicencio, Granada, Vistahermosa, and Puerto Rico (Meta); the humanitarian zones of Curvaradó and Andalucía (Chocó); and the capital, Bogotá.

The Successor Groups: A Predictable Outcome of a Flawed Demobilization

While there are differences between the AUC and its successors, the successor groups are in several respects a continuation of some of the AUC’s paramilitary “blocks” or groups. As reported by the police, a majority of the leaders of the successor groups are mid-level AUC commanders who never demobilized or continued engaging in criminal activity despite ostensibly having demobilized. The groups are active in many of the same regions where the AUC had a presence, and operate in similar ways to the AUC: controlling territory through threats and extortion, engaging in drug trafficking and other criminal activity, and committing widespread abuses against civilians.

The emergence of the successor groups was predictable, in large part due to the Colombian government’s failure to dismantle the AUC’s criminal networks and financial and political support structures during the demobilizations.

The demobilization process suffered from serious flaws, which Human Rights Watch documented extensively and reported on at the time. One problem is that the government failed to verify whether those who demobilized were really paramilitaries, and whether all paramilitaries in fact demobilized. As a result, in some cases paramilitary groups were able to engage in fraud, recruiting civilians to pose as paramilitaries to demobilize, while keeping a core segment of their groups active. This is particularly clear in the case of the Northern Block demobilization, in which there is substantial evidence of outright fraud. There are also signs of fraud in the demobilizations of groups in Medellín and Nariño.

But perhaps a more serious problem was the fact that the government failed to take advantage of the process to thoroughly question demobilizing paramilitaries about their knowledge of the groups’ assets, contacts, and criminal operations, to investigate the groups’ criminal networks and sources of support, and to take them apart. Thus, for example, even though Freddy Rendón, the commander of the Elmer Cárdenas block of the AUC, demobilized, his brother Daniel quickly filled Freddy’s shoes, continuing the block’s drug trafficking, extortion, protection of illegally taken lands held by people associated with the paramilitaries, and its harassment of civilians in the Urabá region.

With some exceptions, prosecutors have failed to thoroughly investigate the AUC’s complex criminal operations, financing sources, and networks of support. Thus, successor groups have been able to easily fill the AUC’s shoes, using the massive resources they already had or could readily obtain through crime to recruit new members and continue controlling and abusing the civilian population.

The Human Rights and Humanitarian Impact of the Successor Groups

The successor groups are engaged in widespread and serious abuses against civilians in much of the country. They massacre, kill, rape, torture, and forcibly “disappear” persons who do not follow their orders. They regularly use threats and extortion against members of the communities where they operate, as a way to exert control over local populations. They frequently threaten, and sometimes attack, human rights defenders, trade unionists, journalists, and victims of the AUC who press claims for justice or restitution of land.

For example, one human rights defender described how, while she was providing assistance to a victim of the AUC at the victim’s home, members of a successor group calling themselves the Black Eagles broke into the house, raped both women, and warned her to stop doing human rights work. “They told me it was forbidden for me to do that in the municipality. They didn’t want victims to know their rights or report abuses,” she told us.[1] When she continued her work, they kidnapped her and said that if she did not leave town, they would go after her family. She sought help from local authorities, who dismissed her saying she should have known better than to do human rights work, and so she eventually fled and went into hiding.

Similarly, Juan David Díaz, a doctor who leads the local Sincelejo chapter of the Movement of Victims of State Crimes, a non-governmental organization, has reported threats and attempts on his life by successor groups. Juan David has been pressing for justice for the murder of his father, Tito Diaz, a mayor who was killed by the AUC, with the collaboration of a former state governor (who was recently convicted).

Trade unionists, a frequent target of the AUC, are now targeted by successor groups. According to the National Labor School, the leading organization monitoring labor rights in Colombia, in 2008 trade unionists reported receiving 498 threats (against 405 trade unionists). Of those, 265 are listed as having come from the successor groups, while 220 came from unidentified actors.[2]

The successor groups are also forcibly displacing large numbers of civilians from their homes. Forced displacement by these groups likely has contributed to a substantial rise in internal displacement nationwide after 2004. According to official figures, after dropping to 228,828 in 2004, the number of newly displaced persons went up each year until it hit 327,624 in 2007. The official 2008 numbers are a little lower, at 300,693, but still substantially higher than at the start of the demobilization process.[3] The non-governmental organization Consultoria para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (CODHES) reports different numbers, finding that around 380,863 people were displaced in 2008—a 24.47 percent increase over its number (305,966) for 2007.[4]

In fact, much of the displacement is occurring in regions where successor groups are active. CODHES says there were 82 cases of group displacement in 2008; the most affected departments were Nariño and Chocó, where the successor groups are very active.[5] Human Rights Watch spoke to dozens of victims who said they had been displaced by successor groups in Nariño, Medellín, the Urabá region, and along the Atlantic Coast.

Without exception, in each of the four major regions Human Rights Watch visited and examined closely for this report, the successor groups were committing serious abuses against civilians.

For example, inMedellín, successor groups (often made up of demobilized or non-demobilized AUC members) continued exerting control in various neighborhoods through extortion, threats, beatings, and targeted killings after the demobilization of the paramilitary blocks in the city. Despite his supposed demobilization, AUC leader Diego Murillo Bejarano (known as “Don Berna”), exerted what locals and many officials described as a monopoly over crime and security in the city, contributing to a significant but temporary reduction in homicides for a few years. But in the words of one city resident, the people in the city at the time were experiencing “peace with a gun to your throat.”[6]

Due to infighting in Don Berna’s group, as well as competition with other successor groups trying to enter the city, the last two years have seen a rapid rise in violence against civilians in Medellín. In the first ten months of 2009 there were 1,717 homicides in the city—more than doubling the 830 killings registered in Medellín for the same period in 2008. The groups have also caused a significant rise in internal displacement in the city. In one case Human Rights Watch documented, more than 40 people from the Pablo Escobar neighborhood of Medellín were forced to flee their homes between late 2008 and early 2009 as a result of killings and threats by the local armed group, which is partly made up of demobilized individuals. The victims, who were hiding in a shelter in Medellín, described living in a state of constant fear in the city: “We can no longer live in Medellín. They have tentacles everywhere.”[7]

In the southern border state of Nariño, massacres, killings, threats, and massive forced displacement of civilians occur on a regular basis, though they are significantly underreported. The successor groups in Nariño are responsible for a significant share of these abuses. For example, between June and July of 2008, almost all residents in three communities in the coastal municipality of Satinga were displaced after one of the successor groups (then using the name Autodefensas Campesinas de Nariño, or Peasant Self Defense Forces of Nariño) went into one of the towns, killed two young men, and reportedly caused the forced disappearance of a third.

A substantial portion of the Liberators of the South Block of the AUC remained active in Nariño and, under the name “New Generation,” violently took over important sectors of the Andean mountain range shortly after the demobilizations. More recently, New Generation has lost influence, but two other groups have gained in strength. Along most of Nariño’s coastline, the Rastrojos and the Black Eagles are active and frequently engage in acts of violence against civilians. Both groups are reported to have a growing presence in the Andean mountain range. In our interviews in the region, several residents, local officials, and international observers described cases in which public security forces apparently tolerated the Black Eagles.

As one man from the Andean town of Santa Cruz told Human Rights Watch: “In Madrigal ... the Black Eagles interrogate us, with the police 20 meters away... [Y]ou can’t trust the army or police because they’re practically with the guys... In Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa we have the Rastrojos. They arrived in March or April. They arrived ... in camouflaged uniform. They’re a lot, 100, 150, 300—they’ve grown a lot... They come in and tax the businessmen. It appears that they sometimes confront guerrillas and other times the Black Eagles and New Generation.”[8]

Colombia’s Obligations

Regardless of their label (whether as armed groups, paramilitaries or organized crime), the Colombian government bears specific responsibilities to address the threat that they pose to the civilian population. Those include obligations to protect civilians from harm, prevent abuses, and ensure accountability for abuses when they occur.[9]The level of state responsibility for the abuses of the successor groups will increase depending on the extent to which state agents tolerate or actively collaborate with these groups.

In addition, some of the successor groups could be considered armed groups for the purposes of the laws of war (international humanitarian law, IHL). Several successor groups appear to be highly organized and to have a responsible command and control structure, and an involvement in the conflict, such that they qualify as armed groups under IHL: for example, ERPAC, which operates on in Meta, Vichada, and Guaviare, and, arguably, some of the groups in Nariño, qualify.

Other groups, enjoying less territorial control or less organization, or that are not aligned to the conflict, may simply be “criminal organizations.” In relation to such groups, however, the state still has a legal duty to take reasonable steps to prevent the commission of human rights violations, to carry out serious investigations of violations if committed, to identify those responsible, to impose the appropriate punishment, and to ensure adequate compensation for victims.

State Response

The government has assigned the Colombian National Police’s Division of Carabineers the lead role in confronting the successor groups.

Government policies stipulate that the military is to step in to confront the successor groups only when the police formally request it, or in situations where the military happens to encounter the groups and must use force to protect the civilian population. But the Carabineers presently appear to lack the capacity and resources to effectively pursue the successor groups in all areas where the successor groups are engaging in abuses. In several areas where the groups operate, the police have no presence. Yet the military does not appear to be stepping in to fight the groups in those areas. In at least one case, Human Rights Watch found that police and army officials in the state of Meta each pointed to the other as the authority responsible for combating the successor groups. The army cited the government policy assigning responsibility to the police as a reason not to step in, and the local police said they had no jurisdiction.

Another problem is the failure of the government to invest adequate resources to ensure that members of the successor groups and their accomplices are held accountable for their crimes. The Office of the Attorney General created a specialized group of prosecutors in 2008 to handle cases involving the successor groups. But the group is understaffed, and is able to focus only on some of the successor groups.

One significant concern, raised by members of the police and the Office of the Attorney General, is corruption and toleration of successor groups by some state officials, which make it difficult to track down, confront, and hold accountable the groups.

The most prominent example of such concerns involves the current criminal investigation into allegations that the chief prosecutor of Medellín, Guillermo Valencia Cossio (the brother of Colombia’s minister of interior), collaborated extensively with successor groups. He has denied the allegations. As detailed in this report, Human Rights Watch also received reports in Nariño, Chocó, Medellín and Meta of situations in which members of the police or army appeared to tolerate the activities of successor groups.

With few exceptions, the government has failed to take effective measures to identify, investigate, and punish state officials who tolerate the successor groups. At times, public security forces appear to respond to allegations that their members are tolerating the groups by simply transferring the officials to other regions. The correct response would be to inform prosecutors of the allegations and suspend the officials in question while criminal investigations are conducted.

The state has also failed to take adequate measures to prevent abuses by the successor groups and protect the civilian population.

The Ministry of Interior’s longstanding protection program for human rights defenders, trade unionists, and journalists has provided much-needed protection to vulnerable individuals. But it does not cover victims of the AUC who are seeking justice, restitution of land, or reparation under the Justice and Peace Law (a 2005 law allowing paramilitaries responsible for atrocities and other serious crimes to receive dramatically reduced sentences in exchange for their demobilization, confession, and return of illegally acquired assets). The Constitutional Court has ordered that these victims receive protection from the state and the government has since implemented a decree providing for increased police security in regions considered to present high risks for victims participating in the Justice and Peace Law Process. Yet it remains unclear whether the program is effectively covering all victims who need protection. These programs also do not cover ordinary civilians in many regions who are continuously being threatened, attacked, and displaced by the successor groups.

In several instances, Human Rights Watch received reports that representatives of the Presidential Agency for Social Action and International Cooperation (Social Action) were refusing to register and provide assistance to internally displaced persons who reported that they were displaced by paramilitaries, on the grounds that paramilitaries no longer exist. While Social Action says that these cases do not reflect official government policy, it must take effective action to ensure that such rejections do not continue at a local level.

Finally, the Ombudsman’s Early Warning System (the EWS), which constantly monitors the human rights situation in various regions and regularly issues well-documented risk reports about the dangers facing civilian populations, has played a key role in reporting on the successor groups’ operations and likely abuses. But other state institutions that should be acting on the EWS’s recommendations often ignore or downplay them. The decision-making process on what actions to take based on the EWS’s risk reports lacks transparency and, as recommended by the US Agency for International Development, requires reform. The EWS has also suffered due to government delays in providing necessary funding.

Recommendations

To the Government of Colombia

On the Demobilization of Paramilitary Blocks

In light of the evidence of significant fraud in the demobilizations of some paramilitary blocks, and the failure of portions of the blocks to demobilize, the government should:

- Establish an ad-hoc independent commission of inquiry to provide a public accounting of what happened during the demobilizations, how many of the purportedly demobilized paramilitaries were really combatants, to what extent paramilitaries remain active today, and to what extent paramilitaries responsible for atrocities have evaded justice.

- Conduct a systematic and coordinated effort to identify land and illegal assets that paramilitaries or their accomplices may be holding, and ensure their recovery and restitution to victims. Among other steps, this will require adequately funding the Superintendence of Notaries and Registry, so that it can increase collection of information about land holdings and cross-reference it with displaced persons’ reports of land takings.

On Combating the Successor Groups

In light of the failure of government policies to prevent the continued growth of the successor groups, the government should:

- Ensure that the Carabineers unit of the police is adequately funded and staffed to confront the successor groups.

- Instruct the army that if its members observe or receive reports of successor groups operating in regions under their jurisdiction, they are to immediately inform the police and appropriate judicial authorities so that they can respond. The instruction should make clear that if the police have no presence in the area, the army should take steps to confront and arrest the successor groups’ members.

- Provide sufficient resources for the Office of the Attorney General to increase the number of prosecutors and investigators in its specialized group investigating successor groups.

On Alleged Toleration of Successor Groups by State Agents

In light of regular, credible allegations that state agents and members of the public security forces are tolerating successor groups, and the tendency of public security forces to address the allegations by simply transferring their members to other regions, the government should:

- Vigorously investigate and prosecute officials who are credibly alleged to have collaborated with or tolerated the successor groups.

- Instruct the police and army that, when they receive allegations of toleration of successor groups by their members, they should immediately report such allegations to the Office of the Attorney General for investigation and suspend the members against whom the allegations were made while investigations are conducted.

On Protection of and Assistance to Victims and Civilians

In light of the failure of current government policies to provide effective protection to victims of the AUC and civilians in regions where the successor groups operate, the government should:

- Put into operation an effective protection program for victims and witnesses of paramilitary crimes, as required by the Colombian Constitutional Court.

- Provide sufficient funding for the Office of the Ombudsman to expand and ensure the uninterrupted operation of the Early Warning System.

- As the US Agency for International Development’s inspector general has recommended, reform the Inter-Institutional Committee on Early Warnings to allow active participation by representatives of the Ombudsman’s Office, to ensure publicity of risk reports and transparency of the Committee’s decision-making, and to ensure appropriate and timely responses to risk reports.

- Issue directives to Social Action and other state agencies providing that Social Action should register persons who are victims of displacement by successor groups. Victims who refer to the perpetrators of abuses against them as paramilitaries should not be denied assistance on the grounds that paramilitaries no longer exist. The directive should provide for disciplinary action against officials who disregard these instructions.

To the Office of the Attorney General of Colombia

On the Demobilization of Paramilitary Blocks

- In light of a 2007 Supreme Court ruling that forbids pardons for crimes of “paramilitarism,” the Office of the Attorney General should open investigations into and take advantage of the opportunity to re-interview demobilized persons who did not receive pardons, and to inquire in greater depth about their groups’ structure, crimes, accomplices, and assets, as well as about the individual’s membership in the group.

- Thoroughly interrogate participants in the Justice and Peace Process about their groups’ financing streams, assets, and criminal networks; dismantle those networks; and recover assets under the control of the groups or their successors.

- Thoroughly investigate and prosecute demobilized mid-level commanders or others who had leadership roles in paramilitary groups and who may have remained active, as well as all high-ranking military, police, and intelligence officers, politicians, businessmen, or financial backers, against whom there is evidence that they collaborated with paramilitaries.

- In light of the high rate of impunity in cases involving forced displacement, substantially increase efforts to investigate and prosecute allegations of forced displacement and land takings by paramilitary groups and their successors.

On Investigation of Successor Group Abuses

- Review the number and distribution of prosecutors and investigators throughout Colombia to ensure that there are sufficient law enforcement authorities available in regions where the successor groups have a presence.

- Strengthen the specialized group focused on investigating the successor groups, by adding a sufficient number of prosecutors and investigators, and providing sufficient resources and logistical support to that group, so that it can effectively and systematically investigate the major successor groups.

- Instruct prosecutors to prioritize investigations of state agents who have been credibly alleged to have tolerated or collaborated with the successor groups.

To the United States

- Provide specific assistance for logistical support, equipment, and relevant training to the specialized group of prosecutors investigating the successor groups. Training should cover not only strategies for investigation and prosecution of the groups themselves, but also of state agents who have allegedly cooperated with or tolerated the groups.

- Urge the Colombian government to expand the Early Warning System of the Ombudsman’s Office, and to ensure that victims of displacement by the successor groups receive the assistance to which they are entitled.

- Because the paramilitary leaders with the most information about the groups’ criminal networks and financing sources were extradited to the United States, the US Department of Justice should instruct US prosecutors to create meaningful incentives for the extradited paramilitary leaders to disclose information about their criminal networks and links to the political system, military, and financial backers, as well as about the successor groups. The United States should use that information to prosecute all implicated persons that are within its jurisdiction and when appropriate should share the information with Colombian authorities to further prosecutions in Colombia.

- Condition not only military but also police aid on accountability for members of public security forces who collaborate with successor groups.

- Continue to delay ratification of the US-Colombia Free Trade Agreement until Colombia’s government meets human rights pre-conditions, including dismantling paramilitary structures and effectively confronting the successor groups that now pose a serious threat to trade unionists.[10]

To all Donor Countries to Colombia

- Press the Colombian government to expand the Early Warning System of the Ombudsman’s Office, and to ensure that victims of displacement by the successor groups receive the assistance to which they are entitled.

- Assist the Colombian justice system to put in place investigative procedures and strategies to ensure accountability for state agents who cooperate with the successor groups.

- Condition any aid to public security forces on accountability for members of public security forces who collaborate with successor groups.

- Delay consideration of free trade deals with Colombia until the Colombian government meets human rights pre-conditions, including dismantling paramilitary structures and effectively confronting the successor groups that now pose a serious threat to trade unionists.

II. Methodology

Human Rights Watch staff have closely monitored the paramilitary demobilization process in Colombia since it started in 2004, through trips several times a year to different regions in the country where paramilitaries operated and where demobilizations occurred, as well as interviews with demobilized paramilitaries, national, state and local officials, members of the public security forces, and victims of the AUC. The findings of this report are in part based on this long-term monitoring of the demobilization process.

In addition, starting in February of 2008, Human Rights Watch staff conducted intensive field research on the successor groups to the AUC, visiting Sincelejo (Sucre) in February 2008; Pasto (Nariño) in February and July 2008, and July 2009; Tumaco (Nariño) in September and October 2008; Cúcuta (Norte de Santander) in September 2008; Barrancabermeja and Bucaramanga (Santander) in September 2008; Villavicencio, Granada, Vistahermosa, and Puerto Rico (Meta) in March 2009; the humanitarian zones of Curvaradó and Andalucía (Chocó) in June 2009; and the cities of Medellín and Bogotá, on multiple occasions in 2008 and 2009.

Human Rights Watch representatives carried out more than 100 interviews with victims of successor groups to the AUC. In most regions, Human Rights Watch was also able to obtain meetings with local and sometimes national authorities, members of the public security forces, non-governmental organizations, and international organizations. In Barrancabermeja, Sincelejo, Cúcuta, Medellín, and Pasto, Human Rights Watch also interviewed individuals who had participated in the demobilization process. In Bogotá, Human Rights Watch met with diplomats, journalists, experts on Colombian security issues, and high-level government and law enforcement officials who are responsible for addressing the issues discussed in the report. Nearly all interviews were conducted in Spanish, the native language of the interviewees (the sole exceptions are interviews with diplomats, foreign journalists or foreign staff at international organizations).

Human Rights Watch received and reviewed documents, reports, books, and criminal case files, as well as photographs and video footage, from multiple sources. Most photographs in this report or included in the associated multimedia presentation, as well as audio testimony from persons in the field, were taken during the course of research for this report.

Interviewees were identified with the assistance of civil society groups, government officials, and journalists, among others. Most interviews were conducted individually, although they sometimes took place in the presence of family members and friends. Many interviewees expressed fear of reprisals by the successor groups, and, for that reason, requested to speak anonymously. Details about individuals have been withheld when information could place a person at risk, but are on file with Human Rights Watch.

II. The Successor Groups: A Predictable Outcome of a Flawed Demobilization

The successor groups, though different in important respects from the paramilitary United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia, or AUC), have taken on many of the same roles, often with some of the same personnel, in some cases with the same counterinsurgency objectives of the AUC. And whether categorized as new paramilitaries or organized criminal gangs, the successor groups are committing egregious abuses and terrorizing the civilian population in ways all too reminiscent of the AUC. As detailed in this chapter, the successor groups have been able to play this role in part because of serious flaws in the AUC demobilization process, which left portions of the paramilitary blocks active and failed to dismantle their criminal networks and sources of funding and support.

A Fundamentally Flawed Demobilization

Between 2003 and 2006 the Colombian government implemented a demobilization process for the AUC. The Colombian government reports that 31,671 paramilitaries demobilized as part of this process, meaning that they participated in “demobilization” ceremonies in which many of them turned over weapons, pledged to abandon their groups and cease criminal activity, and entered government-sponsored reintegration programs.[11] The majority of the persons who went through the ceremonies received pardons for their membership in the group, but were never investigated for other crimes. Since 2005, approximately 1,800 of the demobilized have begun a process of confessions in exchange for sentencing benefits under the “Justice and Peace Law”—a special law drafted by the Uribe administration to offer a single reduced sentence of five to eight years to paramilitaries responsible for serious crimes who fulfill various requirements.[12]

The demobilization process suffered from two basic problems. First, the government failed to take basic steps to verify who was demobilizing. As a result, in at least some regions there was fraud in the demobilizations, and a portion of the groups remained active. Second, the government failed to take advantage of the opportunity to interrogate demobilizing individuals about the AUC blocks’ criminal networks and assets, which may have allowed groups to hide assets, recruit new members and continue operating under new guises.

Failure to Verify Who Was Demobilizing

It is clear that many paramilitary combatants did in fact go through the demobilization process and abandoned their groups for good. However, there is substantial evidence that many others who participated in the demobilization process were stand-ins rather than paramilitaries, and that portions of the groups remained active. There is also evidence that members of the groups who supposedly demobilized continued engaging in illegal activities.

For example, Human Rights Watch has for years received reports that, during the demobilization of the Cacique Nutibara Block in Medellín in 2003, paramilitary forces recruited young men simply for the purpose of participating in the demobilization ceremony, luring them with promises of a generous stipend and other benefits. The reports of fraud were so widespread that Colombia’s High Commissioner for Peace, Luis Carlos Restrepo, stated that “48 hours before [the demobilization] they mixed in common criminals and stuck them in the package of demobilized persons.”[13] Officials from the Permanent Human Rights Unit of Medellín’s Personería said that, based on surveys in Medellín neighborhoods, they estimate that about 75 percent of the persons who demobilized as part of the Cacique Nutibara and Heroes de Granada Blocks in Medellín were not really combatants in those groups.[14]

Similarly, a demobilized man in Norte de Santander said that, in the demobilization of the Catatumbo block, while most of the group’s members did go through the process, “there were people who never belonged to the group but demobilized because they wanted a benefit. He claims they approached the commander, who said ‘if you want to you can enter.’”[15] In other regions, such as Nariño, Human Rights Watch has received reports that paramilitary commanders put on a show of demobilizing while in fact leaving behind a core group of members who could continue exerting territorial control.

In other cases, combatants and mid-level commanders who supposedly demobilized have continued engaging in the same activities. One demobilized individual told Human Rights Watch that his unit participated in the demobilization process “due to pressure from the high commanders, but our local commander told us that whoever wanted to return should just come back to [the region]. They’re still there. That hasn’t finished.”[16]

The most obvious case of fraud is that of the demobilization of the Northern Block, which had a strong presence in the coastal states of Cesar, Magdalena, Atlántico, and La Guajira. Between March 8 and 10, 2006, 4,759 supposed members of the Northern Block demobilized alongside their commander, Rodrigo Tovar Pupo, also known by his alias as “Jorge 40.”[17] But the next day, investigators from the Human Rights Unit of the Attorney General’s Office made a huge find: as part of a long-standing criminal investigation, they arrested Édgar Ignacio Fierro Flórez, also known as “Don Antonio,” a member of the Northern Block who had participated in the demobilization ceremonies but who was reportedly continuing to run the group’s operations in that part of the country.[18] In a search, the investigators found computers and a massive quantity of electronic and paper files about the Northern Block.

Human Rights Watch had access to internal investigative reports about the contents of a computer, hard drives, and files, which show that there was widespread fraud in the Northern Block’s demobilization.[19] The files reportedly contain numerous emails and instant messenger discussions, allegedly involving Jorge 40, in which he apparently gave orders to his lieutenants to recruit as many people as possible from among peasants and unemployed persons to participate in the demobilization. The messages include instructions to prepare these civilians for the day of the demobilization ceremony, so that they would know how to march and sing the paramilitaries’ anthem. They address details such as how to obtain uniforms, and include instructions to guide the “demobilizing” persons on what to say to prosecutors, telling them the questions prosecutors would ask, and how to answer. For example, the messages emphasize that these persons must make clear that there are no “urban” members of the organization—sectors of the group continued operating in urban areas like Barranquilla. One message says that the paramilitaries gave a list of individuals who were demobilizing to the National Intelligence Service (Departamento Administrativo de Seguridad or DAS) in advance, to see if any of them had criminal records, and that the DAS had said they did not. Other messages discuss the members of the group who would not demobilize, so that they could continue controlling key regions.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States, which was present at the Northern Block’s demobilization, described its concern over fraud:

[M]any persons claiming demobilization status did not appear to be combatants... [T]he delegation was concerned at the low number of combatants compared to the number of persons who said they were radio operators, food distributors, or laundresses.... They repeatedly claimed that they were following direct orders of the “maximum leader” of Bloque Norte, Jorge 40, and they provided no information to identify lower ranking officers of the armed unit, thus undermining the credibility of their statement.[20]

As Human Rights Watch has previously documented, the demobilization process lacked mechanisms designed to ensure that those who were going through the demobilization ceremonies were in fact paramilitaries or that all paramilitaries in each block in fact demobilized.[21] As noted by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights with respect to the Northern Block’s demobilization, “there were no mechanisms for determining which persons really belonged to the unit, and were therefore entitled to social and economic benefits, nor for establishing consequences in case of fraud.”[22] The authorities failed to effectively interrogate the persons seeking demobilization benefits, or conduct even a cursory investigation of who they were and what they did.

Contrary to common belief, the vast majority of persons who have “demobilized” have not done so pursuant to the “Justice and Peace Law”—the specialized law designed to grant reduced sentences to demobilized persons responsible for serious crimes.[23] Rather, they have simply sought to receive economic benefits and pardons for their membership in the group pursuant to Colombian Law 782 of 2002 and Decree 128 of 2003.

Until July of 2007, the Colombian government interpreted Law 782 and Decree 128 to allow the government to offer a pardon or “cessation” of criminal proceedings for the crime of concierto para delinquir (conspiracy, the standard charge against paramilitaries) and related crimes such as illegal weapons possession.[24]

Thus, thousands of individuals going through the demobilization ceremonies were simply asked to answer a handful of questions by prosecutors, and later granted pardons or “cessation.”[25]They then entered reintegration programs that offered them stipends and other economic and social benefits, with no further scrutiny from the authorities.[26]

Because of the lack of rigor of the process, it is now very difficult to determine how many of the demobilized were combatants, or how many of the real paramilitaries remained active.

The government has had opportunities to restructure the demobilization process to address some of these problems, but so far has failed to do so. Specifically in July 2007, the Colombian Supreme Court ruled that paramilitaries’ crimes did not constitute “political crimes,” the only type of offense that is pardonable according to Law 782 of 2002 and Colombia’s Constitution.[27] Until the Supreme Court ruling, the government had been applying pardons for paramilitaries on the ground that their crimes were political.[28] The Court’s ruling, while not specifically addressing the application of Law 782, contradicted the government’s interpretation of “paramilitarism” as a political crime that could be pardoned.

But instead of taking advantage of this new opportunity to restructure the demobilization process and conduct more thorough interviews and investigations of the demobilized persons, President Uribe reacted to the ruling by accusing the Court of operating with an “ideological bias,” and claiming that the Court’s independence was only “relative” because “all the institutions of the State must cooperate with the good of the Nation.”[29] Uribe administration officials claimed that the ruling threatened to derail the demobilization process because approximately 19,000 individuals who had gone through demobilization ceremonies had not yet received pardons, and now they would be barred from doing so.[30]

To avoid having to investigate the demobilized paramilitaries, in July 2009 the Colombian Congress amended the country’s Penal Code to allow the Office of the Attorney General to apply what is known as the “principle of opportunity” (a form of prosecutorial discretion) to suspend investigations against or refuse to prosecute demobilized persons.[31]

Failure to Dismantle Paramilitaries’ Criminal and Financial Networks

To secure a genuine and lasting paramilitary demobilization, the government should have focused on the sources of their power: their drug trafficking routes and criminal activity, their assets, their financial backers, and their support networks in the political system and military.

But as Human Rights Watch has documented in past reports, the government actively resisted efforts to dismantle paramilitaries’ networks and to investigate their accomplices.[32] For example, the Justice and Peace Law, which offers reduced sentences to paramilitaries responsible for atrocities in exchange for their demobilization, as originally drafted by the government, did not provide for effective sanctions if paramilitaries seeking reduced sentences failed to confess their crimes or turn over illegally acquired assets.

Some of these problems were corrected thanks to a Constitutional Court ruling, which said that paramilitaries who wanted reduced sentences would be required to give full and truthful confessions and turn over illegally acquired assets, and that they would risk losing reduced sentences if they lied.[33] As a result, throughout 2007 and part of 2008, prosecutors began to obtain some valuable information from paramilitary commanders about their crimes and accomplices. At the same time, the Colombian Supreme Court began a series of unprecedented investigations of paramilitary collaborators in the political system.[34] Today, more than 80 members of the Colombian Congress have come under Supreme Court investigation or have been convicted for links to paramilitaries.[35]

Yet the implementation of the reformed Justice and Peace Law has continued to suffer from serious problems.[36] The vast majority of paramilitaries who demobilized are not actively participating in the Justice and Peace Law process, as only the ones who already had criminal records or were afraid they might be caught had a real incentive to participate—the overwhelming majority simply sought pardons under Law 782. The Attorney General’s Office lists 3,712 persons as having applied for benefits under the Justice and Peace Law.[37] Of these, only 1,836—less than half—have started their “versiones libres”—the statements to prosecutors in which they’re supposed to confess their crimes if they wish to receive reduced sentences. And only five are reported to have completed their confessions.[38] The leaders who probably had the most information to offer have been extradited to the United States, where they have, for the most part, ceased talking to Colombian authorities.[39]

The Colombian government has yet to make a serious nationwide effort to track down the AUC’s massive illegally obtained assets and wealth, which can easily be used to recruit new members and continue running criminal operations under new guises.

Among other illegal activities, the paramilitaries were responsible for widespread land takings, but the government has yet to identify the stolen land. “I left my land with my children because of threats and massacres in Ungía, Chocó,” one displaced woman told Human Rights Watch. “Those who didn’t leave are now dead... The majority of people from there left land that today the paramilitaries possess.”[40] Today, according to official statistics, more than 3 million people are registered as internally displaced in Colombia.[41] A recent national poll of displaced persons found that the largest group—37 percent—was pushed out by paramilitary groups.[42] Most left behind land or real estate.[43] Official estimates of the amount of land left behind by displaced persons range from 2.9 million hectares (between 2001 and 2006, according to the State Comptroller’s Office) to 6.8 million hectares (according to the Presidential Agency for Social Action and International Cooperation, or “Social Action,” in a 2004 study).[44] The takings have particularly affected Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities that have been pushed out of their traditional territories.[45]

As of February 2008, the National Reparations Fund, charged with holding land and assets turned over by paramilitaries during the Justice and Peace Process, contained only US$5 million worth of assets in the form of land, cattle, cash, and vehicles.[46] As of October 2009, only thirty-one paramilitaries, and six paramilitary blocks, had officially turned over assets to the government as part of the Justice and Peace Process.[47]

At least part of the problem is that the government itself decreed that individual paramilitaries could turn over illegal assets anytime before they were actually charged with crimes under the Justice and Peace Law—giving them little incentive to turn them over early on.[48] Once they were extradited, most leaders lost even that incentive.

Identifying and recovering the land that paramilitaries took by force is a complex task that will require a well-planned strategy and the investment of adequate resources. The Justice and Peace Law, various implementing decrees, and Constitutional Court rulings require the government to ensure land restitution.[49] But the government has only recently started to establish the regional commissions on land restitution required by the Justice and Peace Law.[50] And it has yet to invest adequate resources to collect basic information about the displaced persons and the land or other property that was taken from them.[51]

Unless the government takes effective measures to identify the land that paramilitaries took and return it to its owners, it will be leaving intact a significant source of wealth and power for paramilitary accomplices and front men. Due to the lack of investigation of this issue, it is difficult to know for sure to what extent AUC assets and financing sources have continued fueling the activities of the successor groups. However, as described in later sections, in regions such as Urabá landowners who benefited from paramilitary takings have been reported to be working with successor groups to threaten and even kill victims who seek to recover land.

Finally, as Human Rights Watch has documented before, despite the efforts of the Supreme Court and others to investigate and hold accountable paramilitary collaborators in politics and the military, the government has repeatedly taken steps that have undermined or limited progress in this area.[52] In particular, the Uribe administration has repeatedly launched public personal attacks on the Supreme Court and its members, in what looks like a concerted campaign to smear and discredit the court, and has proposed constitutional amendments to remove the so-called “para-politics” investigations from the court’s jurisdiction. It has also blocked meaningful efforts to reform Congress to eliminate paramilitary influence.[53] According to recent news reports, several of the politicians who have come under investigation and have resigned are supporting candidacies of their siblings and spouses to replace them, so that they may retain their influence in Congress.[54]

Links between the AUC and its Successors

There are differences between the successor groups and the AUC. First, the successor groups, for the most part, appear to operate independently from one another—they have yet to form a single coalition articulating their shared goals and interests or coordinating their criminal activities and, in some cases, military-like operations. Second, their leaders are less visible than some of the AUC leaders, such as Carlos Castaño, were. And third, the focus of most successor groups appears to be less on counterinsurgency. Nonetheless, they share with the AUC a deep involvement in mafia-like criminal activities, including drug-trafficking, as has been noted not only by the government but also by the OAS Mission to Support the Peace Process in Colombia (the MAPP/OAS).[55] And as described below, there are other significant ways in which these groups are a continuation of, and are similar to, the AUC’s blocks.

Leadership

Based on police reports about the structure of the successor groups, it appears that most are led by former mid-level commanders of the AUC who either never demobilized or simply continued their operations after supposedly demobilizing. This is true of Pedro Oliverio Guerrero (Cuchillo), the leader of ERPAC; several of the leaders of the groups operating in Medellín; and Ovidio Isaza in the Middle Magdalena region, among others. Daniel Rendón, who led the Urabeños until his arrest in 2009, was also an AUC member and the brother of Freddy Rendón, the leader of the Elmer Cárdenas block of the AUC. The main exception is the Rastrojos group, which is reported to have developed from an armed wing of the North of the Valley drug cartel, which was barred from participating in the demobilization process.

Drug Trafficking and Other Criminal Activity

Like the AUC blocks, the successor groups are deeply involved in drug trafficking and other criminal activities, including smuggling, extortion, and money laundering. In fact, the AUC was a descendant of “Muerte a Secuestradores” (Death to Kidnappers), an alliance formed in the 1980s by the drug lords Pablo Escobar, Fidel Castaño, Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha, and others to free relatives or traffickers who had been kidnapped by guerrillas.[56]

In Norte de Santander, for example, even though the Catatumbo Block of the AUC engaged in horrific massacres and killings of civilians whom they labeled as “guerrilla sympathizers,” sources said they rarely confronted the guerrillas directly. One of their main activities was controlling the lucrative drug corridors and smuggling over the border with Venezuela, as well as extortion and other criminal activity.[57]

Many well-known paramilitary leaders like “Don Berna” or “Macaco” were known primarily as drug traffickers before they claimed the mantle of paramilitarism.[58]

One senior police officer went so far as to tell Human Rights Watch that he saw clear continuity between the paramilitaries and the successor groups, in the sense that the AUC’s blocks “were not paramilitaries; they were narcotrafficking mafias that latched on to paramilitarism. [The successor groups] are the product of a demobilization process that was full of lies. Those guys tricked all of us. They included young boys who were displaced. The ones who killed did not demobilize.”[59]

Counterinsurgency Operations

Human Rights Watch received information indicating that some of the groups (or sectors of them) occasionally engage in counterinsurgency operations and persecute persons whom they view as FARC collaborators, particularly in regions where the FARC still has a presence. For example, in Meta, residents reported that members of the successor groups had been seeking information about persons who might have helped guerrillas, and had threatened some people as “guerrilla collaborators.” In Nariño, too, Human Rights Watch received reports of possible confrontations between some of the successor groups and the FARC.

Many of the threats that trade unionists, human rights defenders, and others have received from the successor groups refer to their targets as guerrillas or guerrilla collaborators, using language similar to that used by the AUC. Similarly, threatening flyers that have appeared in many Colombian towns and cities in the last year or so, and which are sometimes signed by “Black Eagles” or other similar groups, often label their recipients “military objectives” and accuse them of being “guerrillas.”[60]

Most successor groups appear less focused on counterinsurgency than the AUC. In fact, government sources often speak of links between the successor groups and FARC or ELN guerrillas, at least for purposes of drug trafficking. Several sources told Human Rights Watch that in Nariño and Cauca, the Rastrojos (which were never part of the AUC) have developed an alliance with the ELN guerrillas against the FARC to control territory for drug trafficking.[61]

Yet the AUC itself included several groups that did not have a strong counterinsurgency focus, such as Don Berna’s groups in Medellín, which were to a large extent focused on controlling criminal activity. The same is true of the groups run by Carlos Mario Jiménez Naranjo (“Macaco”), the head of the Central Bolívar Block of the AUC; Rodrigo Pérez Alzate (“Pablo Sevillano”), the head of the Liberators of the South Block; and Francisco Javier Zuluaga (“Gordolindo”) who led the Pacific Block of the AUC.[62]

According to one of the specialized prosecutors charged with investigating the successor groups, these groups are “a development from the paramilitaries... That ideological base that the paramilitaries had, which was already very questionable, now they have it even less.”[63]

III. The Rise and Growth of the Successor Groups

The AUC demobilizations officially ended on August 15, 2006.[64] In their aftermath, scores of successor groups with close ties to the AUC appeared around the country.

The OAS Mission to Support the Peace Process in Colombia (or MAPP), tracking official information from the Colombian police, reported in early 2007 that it had identified “22 units, with the participation of middle-ranking officers—demobilized or not—the recruitment of former combatants... and the control of illicit economic activity.”[65] The MAPP estimated the groups had approximately 3,000 members.[66]

Since then, the groups’ membership and areas of operation have consistently grown. Estimates of the successor groups’ number and membership vary a great deal by source, but in some cases run as high as 10,200.[67] In mid-2008, the MAPP expressed concern “about the continued existence and even increase in these factions, despite actions taken by law enforcement agencies. This shows a significant resistance and revival capacity, with resources making possible ongoing recruitment and the persistence of corruption at the local level.”[68]

The police, who have the most conservative figures, say the total number of groups has dropped, as many have fused or absorbed one another and some have disappeared or been defeated.[69] But their membership and regional presence continues to grow. As of July 2009, the police reported that the groups had 4,037 members, an increase over the 3,760 they said existed a few months before, in February of 2009. They operate in 24 of Colombia’s 32 departments. Police figures also show that between February and July of 2009, the groups increased their areas of operation by 21 municipalities, jumping from 152 to 173.[70]

The Principal Successor Groups

As of mid-2009, police documents stated that eight successor groups were in operation.[71] According to sources in the police and the Office of the Attorney General, four of the groups are significantly stronger and are the main focus of attention of the authorities:[72]

- Los de Urabá or the Urabeños: This group was formerly run by Daniel Rendón (also known as “Don Mario”), a non-demobilized AUC member who was also the brother of Freddy Rendón Arias (“El Alemán”), the former leader of the “Elmer Cárdenas” Block of the AUC, which supposedly demobilized in 2006.[73] After Don Mario’s arrest in early 2009, the police reported that the group had come under the command of Juan de Dios Usuga David, also known as “Giovanni.”[74] However, in October 2009 the police reported the arrest of another man, Omar Alberto Gómez, known as “El Guajiro,” whom they identified as the group’s leader.[75] According to police documents, this group, which has in the past used other names such as “Heroes de Castaño” (the “Heroes of Castaño,” alluding to disappeared AUC chief Carlos Castaño) and “Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia” (Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia) has spread its area of operation from the Urabá region of Chocó and Antioquia to nine departments and seventy-nine municipalities. The group is reported to have 1,120 members.[76]

- The Rastrojos: According to multiple reports received by Human Rights Watch, the Rastrojos were an armed wing of the North of the Valley drug cartel, who have historically been tied to Wilber Varela (also known as “Jabón”), a drug trafficker who was reportedly killed in Venezuela in January 2008.[77] They were believed to have had links to demobilized paramilitary leader Carlos Mario Jiménez (also known as “Macaco”).[78] The group attempted to participate in the demobilization process but ultimately was not allowed to do so because the government considered it a criminal organization.[79] Official documents state that the Rastrojos now operate in 10 departments and 50 municipalities, have 1,394 members, and are commanded by Javier Antonio Calle Serna (also known as “El Doctor”).[80]

- The Paisas: Multiple sources told Human Rights Watch that the Paisas are the heirs of paramilitary leader Don Berna, and are related to his “Envigado Office,” a criminal organization in Medellín. Don Berna is reported to have retained control over these groups from prison. Since his extradition, there have been reports of substantial infighting and possible fracturing of the groups. Official documents state that the Paisas operate in 7 departments and 45 municipalities and have 415 members; their leader is said to be Fabio León Vélez Correa (also known as “Nito”).[81]

- Ejército Revolucionario Popular Antiterrorista Colombiano, or ERPAC (Colombian Revolutionary Popular Antiterrorist Army): This group is led by Pedro Oliverio Guerrero Castillo, also known as “Cuchillo.” Cuchillo is a long-running paramilitary leader, first operating in the private army of drug-trafficker Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha, and then joining the AUC’s Centauros Block. He is reported to have killed the then-leader of the Centauros Block, Miguel Arroyave.[82] He participated in the demobilization process as the leader of the Heroes del Guaviare front of the Centauros Block, but continued his illegal activity. The ERPAC operates mostly on the plains east of Bogotá, in the departments of Meta, Casanare, Vichada, and Guaviare, though police reports state it also has a presence in Arauca and Guainia. Police estimate it has 770 members.[83]

In addition, the police report having identified the following other groups:

- Renacer (Rebirth): The police report that this group operates in 11 municipalities of the department of Chocó under the leadership of José María Negrete (also known as “Raúl”), and has 100 members.[84]

- Nueva Generación (New Generation): Human Rights Watch has received substantial credible information indicating that this group was created by members of the Liberators of the South Block of the AUC almost immediately after its supposed demobilization. The police report that this group operates in three municipalities in the department of Nariño, under the leadership of Omar Grannoble (also known as “El Tigre”) and has 114 members.[85]

- Los del Magdalena Medio (the ones from the Middle Magdalena region): The police report that this group operates in eight municipalities in four departments and has 80 members. Its leader, according to police documents, is Ovidio Isaza (also known as Roque).[86] Isaza is a former leader of the AUC in the Magdalena Medio region. He is also the son of Ramon Isaza, one of the first and most prominent AUC leaders. After participating in the demobilization process, he never went through the Justice and Peace Process, and was released by authorities due to lack of evidence.[87]

- The Machos: Like the Rastrojos, this group is reported to be the armed branch of a preexisting drug trafficking cartel. The police reports it operates in two municipalities of the Valle del Cauca department and has 44 members.[88]

Interviews with victims and local authorities around the country suggest that Colombian police figures underestimate the membership and number of the successor groups. In some regions, Human Rights Watch received reports about the existence of groups that the police did not recognize as such. For example, in an interview with Human Rights Watch, a senior member of the police said that the Black Eagles group in Nariño is “more mythical” than real.[89] Yet Human Rights Watch received repeated, consistent statements from people in Nariño about the operation of the Black Eagles, who controlled territory in several areas, threatened civilians, and were apparently engaged in a bloody turf war against the Rastrojos over control of the port city of Tumaco. Less than two months after denying the existence of the Black Eagles in meetings with Human Rights Watch, the police announced the arrest of 36 members of the Black Eagles in Nariño.[90] Similarly, even though the police list ERPAC as having 770 members, news reports cite the army and the investigative arm of the Office of the Attorney General as estimating that it has 1,120 members and is rapidly growing through active recruitment.[91]

What are the Black Eagles?

In many different parts of the country, witnesses that spoke to Human Rights Watch said that the persons who were controlling crime and killing, forcibly displacing, raping, or threatening them, had identified themselves as members of the “Black Eagles.” Often, flyers and written threats against human rights defenders and others are signed by the Black Eagles.

Yet members of the Police told Human Rights Watch that the “Black Eagles” was not a single group, but rather a convenient label that many groups, including local gangs, had appropriated to generate fear in the population.[92]

As described later in this report, in Nariño, Human Rights Watch received consistent reports by several residents and authorities that indicate that the Black Eagles in that region are in fact a single successor group with a high level of coordination, operating in many ways like a former AUC block. In Urabá, Human Rights Watch received reports that the local successor group (there called the Urabeños) at times has called itself the Black Eagles, using the name interchangeably with others. These groups, at least, are not simply local gangs. Nonetheless, Human Rights Watch did not receive substantial information indicating that the various groups using the label Black Eagles are a single national group.

Recruitment of New Members

The successor groups have been actively recruiting members, offering very high wages, and sometimes threatening people to get them to join. They often target demobilized persons.

According to one demobilized individual in Sucre, when he demobilized in 2005, his commander told the group that “whoever wanted to turn himself in should do so, but that whoever wants to return, should return” to their area of operation in Antioquia. “They’re there. That’s not over,” he said. In fact, “there are lots of active groups of the same paramilitaries. Even yesterday when I went to school a classmate told me that ‘Cucho’ called him so we would pick up some guys and go out there. They’re paying 500 or more. They’ve approached me several times, old commanders, friends... Lots of guys have gone.”[93]

Another demobilized man said that “there were people who went to the new groups... There are kids who ask me if I’d go again. You’re afraid to talk to anybody. Many have been killed because they’ve spoken about something. The self-defense forces aren’t finished.... There are other people who go too, new people. [The pay] doesn’t drop below half a million pesos. It’s easy to enter, but leaving is difficult.”[94]A local official in Sincelejo told Human Rights Watch that he knew of approximately 14 cases in which demobilized men had been approached by their former commanders to rejoin their groups.[95]

A member of an organization of demobilized paramilitaries in Barrancabermeja said that members of his organization had been murdered. “We’re in a tough moment because we are being threatened by people who want us to return to crime. It hurts because we’ve tried to organize, but we have received threats... [T]here are still criminal groups that see the demobilized as possible recruits and they do it through threats.”[96]

He recounted how, in mid-2008, when a group of demobilized men was attending a psychological support session outdoors as part of the reintegration program, armed men passed by in a motorcycle and shot at them, injuring the psychologist and three of the program participants.[97] A few days later, on August 19, he said he received a call from someone saying he should meet the “new company” at a soccer field. The demobilized man said they threatened his family. He did not go, but was afraid of what would happen.[98]

MAPP officials told Human Rights Watch that they estimated that more than 50 percent of the members of the successor groups were new recruits. Often, the groups use threats and deception to convince new members to join, according to the MAPP.[99] They said some of the strongest recruitment they had documented was taking place in the regions of Urabá, Cesar, La Guajira and the Middle Magdalena, Buenaventura, and the Nariño coast. “There are historic areas for recruitment, that the groups know,” said a MAPP representative.

Often recruits are taken to work in distant regions. For example, in the southern state of Nariño, Human Rights Watch received numerous reports that many members of the group that citizens identify as the Black Eagles had an accent characteristic of people from Antioquia, in the north of the country. Similarly, Human Rights Watch received reports that many young men from the western Urabá region were operating under Cuchillo’s command on the plains states, in the east of Colombia.

One man in the Urabá region of Chocó department described how the Black Eagles had taken 18 young men from Belen de Bajirá. “One was my grandson and he escaped. They took them to Guaviare to join the Black Eagles there. They’re new faces, not from here. And they send the ones from here to other places.”[100]

The groups’ frequent recruitment and movement of men from one part of the country to another suggests a high level of national integration and operation by the groups.

Human Rights Watch also received reports of young men who remained in the demobilization program but were simultaneously working for paramilitary groups. Sources that work with the reintegration program in the department of Norte de Santander said that many participants, especially in the towns of Tibú and Puerto Santander, “continue committing crimes. But we can’t do anything until somebody reports them... [T]he guys are with the police and pass in front of the police, and even the community itself seeks them out [instead of] going to the police to complain... It’s perverse... But there’s a situation of silence... even though it’s a widely known secret [secreto a gritos].”[101] One demobilized man living in Puerto Santander agreed, stating that “the ones in Puerto Santander have a strange monopoly... They go to the training sessions and meetings with the OAS but they’re working with the Black Eagles.”[102]

IV. The Successor Groups’ Human Rights and Humanitarian Impact

The successor groups are committing widespread and serious abuses, including massacres, killings, forced disappearances, rape, forced displacement, threats, extortion, kidnappings, and recruitment of children as combatants.

The most common abuses are killings of and threats against civilians, including trade unionists, journalists, human rights defenders, and victims of the AUC seeking restitution of land and justice as part of the Justice and Peace Process. They are one of the main actors responsible for the forced displacement of over a quarter of a million Colombians every year.

The MAPP has noted that in several regions people “do not perceive an improvement in their security conditions” as a result of the paramilitary demobilization.[103] Colombians in many different regions told Human Rights Watch that the climate of fear in which they lived had not meaningfully changed as a result of the demobilizations.

The government has occasionally acknowledged this fact, in an indirect manner. For example, in its 2007 report on human rights in Colombia, the Human Rights Observatory of the Vice-President’s Office stated that “[h]istorically the self-defense forces were the principal group responsible for massacres in the country, but with their disappearance... there is an increase in the percentage of cases with no known author... [S]everal of these cases ... are linked to the appearance of new criminal gangs linked to drug trafficking.”[104]

In fact, between 2007 and 2008 the number of yearly massacres in Colombia jumped by 42 percent, to 37 cases (involving 169 victims) from 26 cases (involving 128 victims). According to the Human Rights Observatory, the successor groups were using the massacres “as a means of revenge, to take control of territory, show power, and conduct ‘purges’ within their organizations, all of this directed towards controlling the drug business.”[105]

Violence and Threats against Vulnerable Groups

In every region Human Rights Watch visited, it received numerous reports of threats and killings by the successor groups. Often their targets are human rights defenders, trade unionists, journalists, and victims of the AUC who seek to claim their rights. Such threats often have a chilling effect on, or otherwise impair, the legitimate work of their targets.