“Off the Backs of the Children”

Forced Begging and Other Abuses against Talibés in Senegal

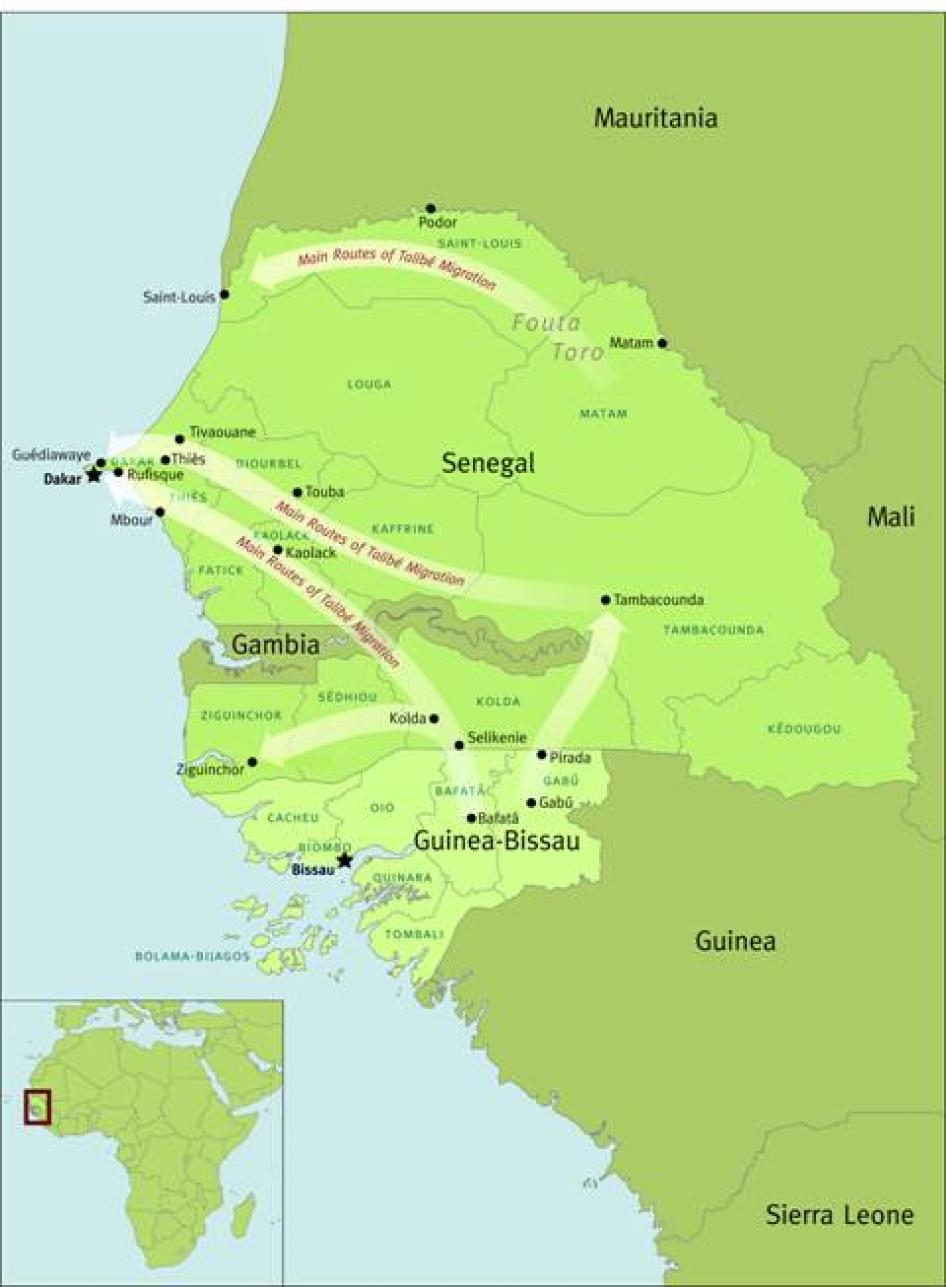

Map of Senegal and Guinea-Bissau

© 2010 John Emerson / Human Rights Watch

The main routes of talibé migration are well known in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau. The routes shown are based on Human Rights Watch’s interviews with talibés, marabouts, parents, and humanitarian and government officials in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau; a 2007 quantitative study of begging children in Dakar performed by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the International Labour Organization, and the World Bank; and detailed records kept by SOS Talibé Children (SOS Crianças Talibés) of children returned to Guinea-Bissau after running away from daaras in Senegal.

Summary

I have to bring money, rice, and sugar each day. When I can’t bring everything, the marabout beats me. He beats me other times too, even when I do bring the sum.... I want to stop this, but I can’t. I can’t leave, I have nowhere to go.–Modou S., 12-year-old talibé in Saint-Louis

The teachings of Islam are completely contrary to sending children on the street and forcing them to beg.... Certain marabouts have ignored this—they love the comfort, the money they receive from living off the backs of the children.–Aliou Seydi, marabout in Kolda

At least 50,000 children attending hundreds of residential Quranic schools, or daaras, in Senegal are subjected to conditions akin to slavery and forced to endure often extreme forms of abuse, neglect, and exploitation by the teachers, or marabouts, who serve as their de facto guardians. By no means do all Quranic schools run such regimes, but many marabouts force the children, known as talibés, to beg on the streets for long hours—a practice that meets the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) definition of a worst form of child labor—and subject them to often brutal physical and psychological abuse. The marabouts are also grossly negligent in fulfilling the children’s basic needs, including food, shelter, and healthcare, despite adequate resources in most urban daaras, brought in primarily by the children themselves.

In hundreds of urban daaras in Senegal, it is the children who provide for the marabout. While talibés live in complete deprivation, marabouts in many daaras demand considerable daily sums from dozens of children in their care, through which some marabouts enjoy relative affluence. In thousands of cases where the marabout transports or receives talibés for the purpose of exploitation, the child is also a victim of trafficking.

The Senegalese and Bissau-Guinean governments, Islamic authorities under whose auspices the schools allegedly operate, and parents have all failed miserably to protect tens of thousands of these children from abuse, and have not made any significant effort to hold the perpetrators accountable. Conditions in the daaras, including the treatment of children within them, remain essentially unregulated by the authorities. Well-intentioned aid agencies attempting to fill the protection gap have too often emboldened the perpetrators by giving aid directly to the marabouts who abuse talibés, insufficiently monitoring the impact or use of such aid, and failing to report abuse.

Moved from their villages in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau to cities in Senegal, talibés are forced to beg for up to 10 hours a day. Morning to night, the landscape of Senegal’s cities is dotted with the sight of the boys—the vast majority under 12 years old and many as young as four—shuffling in small groups through the streets; weaving in and out of traffic; and waiting outside shopping centers, marketplaces, banks, and restaurants. Dressed in filthy, torn, and oversized shirts, and often barefoot, they hold out a small plastic bowl or empty can hoping for alms. On the street they are exposed to disease, the risk of injury or death from car accidents, and physical and sometimes sexual abuse by adults.

In a typical urban daara, the teacher requires his talibés to bring a sum of money, rice, and sugar every day, but little of this benefits the children. Many children are terrified about what will happen to them if they fail to meet the quota, for the punishment—physical abuse meted out by the marabout or his assistant—is generally swift and severe, involving beatings with electric cable, a club, or a cane. Some are bound or chained while beaten, or are forced into stress positions. Those captured after a failed attempt to run away suffer the most severe abuse. Weeks or months after having escaped the daara, some 20 boys showed Human Rights Watch scars and welts on their backs that were left by a teacher’s beatings.

Daily life for these children is one of extreme deprivation. Despite bringing money and rice to the daara, the children are forced to beg for their meals on the street. Some steal or dig through trash in order to find something to eat. The majority suffer from constant hunger and mild to severe malnutrition. When a child falls ill, which happens often with long hours on the street and poor sanitary conditions in the daara, the teacher seldom offers healthcare assistance. The children are forced to spend even longer begging to purchase medicines to treat the stomach parasites, malaria, and skin diseases that run rampant through the daaras. Most of the urban daaras are situated in abandoned, partially constructed structures or makeshift thatched compounds. The children routinely sleep 30 to a small room, crammed so tight that, particularly during the hot season, they choose to brave the elements outside. During Senegal’s four-month winter, the talibés suffer the cold with little or no cover, and, in some cases, even a mat to sleep on.

Many marabouts leave their daara for weeks at a time to return to their villages or to recruit more children, placing talibés as young as four in the care of teenage assistants who often brutalize the youngest and sometimes subject them to sexual abuse.

In hundreds of urban daaras, the marabouts appear to prioritize forced begging over Quranic learning. With their days generally consumed with required activity from the pre-dawn prayer until late into the evening, the talibés rarely have time to access forms of education that would equip them with basic skills, or for normal childhood activities and recreation, including the otherwise ubiquitous game of football. In some cases, they are even beaten for taking time to play, by marabouts who see it as a distraction from begging.

Marabouts who exploit children make little to no effort to facilitate even periodic contact between the talibés and their parents. The proliferation of mobile phones and network coverage into even the most isolated villages in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau should make contact easy, but the vast majority of talibés never speak with their families. In many cases, preventing contact appears to be a strategy employed by the marabout.

Unfed by the marabout, untreated when sick, forced to work for long hours only to turn over money and rice to someone who uses almost none of it for their benefit—and then beaten whenever they fail to reach the quota—hundreds, likely thousands, of talibés run away from daaras each year. Many talibés plan their escape, knowing the exact location of runaway shelters. Others choose life on the streets over the conditions in the daara. As a result, a defining legacy of the present-day urban daara is the growing problem of street children, who are thrust into a life often marked by drugs, abuse, and violence.

The exploitation and abuse of the talibés occurs within a context of traditional religious education, migration, and poverty. For centuries, the daara has been a central institution of learning in Senegal. Parents have long sent their children to a marabout—frequently a relative or someone from the same village—with whom they resided until completing their Quranic studies. Traditionally, children focused on their studies while assisting with cultivation in the marabout’s fields. Begging, if performed at all, was rather a collection of meals from community families. Today, hundreds of thousands of talibés in Senegal attend Quranic schools, many in combination with state schools, and the practice often remains centered on religious and moral education. Yet for at least 50,000 children, including many brought from neighboring countries, marabouts have profited from the absence of government regulation by twisting religious education into economic exploitation.

The forced begging, physical abuse, and dangerous daily living conditions endured by these talibés violate domestic and international law. Senegal has applicable laws on the books, but they are scant enforced. Senegal is a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, and all major international and regional treaties on child labor and trafficking, which provide clear prohibitions against the worst forms of child labor, physical violence, and trafficking. International law also affords children the rights to health, physical development, education, and recreation, obligating the state, parents, and those in whose care a child finds himself to fulfill these rights.

The state is the primary entity responsible for protecting the rights of children within its borders, something which the government of Senegal has failed to do. With the exception of a few modern daaras—which are supported by the government and combine Quranic and state school curricula—not one of the Quranic schools in Senegal is subject to any form of government regulation. In the last decade, the government has notably defined forced begging as a worst form of child labor and criminalized forcing another into begging for economic gain, but this adequate legislation has so far led to little concrete action. Rather than hold marabouts accountable for forced begging, gross neglect, or, in all but the rarest of cases, severe physical abuse, Senegalese authorities have chosen to avoid any challenge to the country’s powerful religious leaders, including individual marabouts.

Countries from which a large number of talibés are sent to Senegal, particularly Guinea-Bissau, have likewise failed to protect their children from the abuse and exploitation that await them in many urban Quranic schools in Senegal. The Bissau-Guinean government has yet to formally criminalize child trafficking and, even under existing legal standards, has been unwilling to hold marabouts accountable for the illegal cross-border movement of children. Guinea-Bissau has also failed domestically to fulfill the right to education—around 60 percent of children are not in its school system—forcing many parents to view Quranic schools in Senegal as the only viable option for their children’s education.

Parents and families, for their part, often send children to daaras without providing any financial assistance. After informally relinquishing parental rights to the marabout, some then turn a blind eye to the abuses their child endures. Many talibés who run away and make it home are returned to the marabout by their parents, who are fully aware that the child will suffer further from forced begging and often extreme corporal punishment. For these children, home is no longer a refuge, compounding the abuse they endure in the daara and leading them to plan their next escapes to a shelter or the street.

Dozens of Senegalese and international aid organizations have worked admirably to fill the protection gap left by state authorities. Organizations provide tens of centers for runaway talibés; work to sensitize parents on the difficult conditions in the daara; and administer food, healthcare, and other basic services to talibés. Yet in some cases, they have actually made the problem worse. By focusing assistance largely on urban daaras, some aid organizations have incentivized marabouts to leave villages for the cities, where they force talibés to beg. By failing to adequately monitor how marabouts use assistance, some organizations have made the practice even more profitable—while marabouts receive aid agency money with one hand, they push their talibés to continue begging with the other. And by treading delicately in their effort to maintain relations with marabouts, many aid organizations have ceased demanding accountability and have failed to report obvious abuse.

The government of Senegal has launched an initiative to create and subject to regulation 100 modern daaras between 2010 and 2012. While the regulation requirement in these new schools is a long-overdue measure, the limited number of daaras affected means that the plan will have little impact on the tens of thousands of talibés who are already living in exploitative daaras. The government must therefore couple efforts to introduce modern daaras with efforts, thus far entirely absent, to hold marabouts accountable for exploitation and abuse.

Under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child the state is obliged to ensure that children have access to a compulsory, holistic primary education that will equip them with the basic skills they need to participate fully and actively in society. In addition to supporting the introduction of modern daaras, the government of Senegal should therefore ensure that children have the choice of access to free primary education through state schools or other means.

Without enforced regulation of daaras and success on accountability, the phenomenon of forced child begging will continue its decades-long pattern of growth. If the Senegalese government wants to retain its place as a leading rights-respecting democracy in West Africa, it must take immediate steps to protect these children who have been neglected by their parents and exploited and abused in the supposed name of religion.

Recommendations

To the Government of Senegal

- Enforce current domestic law that criminalizes forcing another into begging for economic gain—specifically, article 3 of Law No. 2005-06—including by investigating and holding accountable in accordance with fair trial standards marabouts and others who force children to beg.

- Consider amending the law to provide for a greater range of penalties, reducing the range of punishment to include only non-custodial sentences and prison sentences under two years, from the present mandatory two to five years, so that punishments can be better apportioned to the severity of exploitation.

- Create a registry of marabouts who are documented by authorities to have forced children to beg for money, or who are convicted for physical abuse or for being grossly negligent in a child’s care.

- Enforce article 298 of the penal code that criminalizes the physical abuse of children, with the exception of “minor assaults,” including by investigating and holding accountable in accordance with fair trial standards marabouts and others who physically abuse talibés.

- Amend the law to include specific reference to all forms of corporal punishment in schools, in accordance with international law, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child.

- Amend the law to ensure that it holds responsible a marabout who oversees, orders, or fails to prevent or punish an assistant teacher who inflicts physical abuse on a talibé.

- Enforce anti-trafficking provisions under Law No. 2005-06, which criminalizes child trafficking in accordance with the United Nations Trafficking in Persons Protocol.

- Provide additional resources to civil and border police units, particularly in the regions of Ziguinchor and Kolda, to enhance their capacity to deter child trafficking.

- Improve and require periodic training for police units to ensure that they know the laws governing movements of children across borders.

- Express support, from the highest levels of government, for the prosecution of marabouts who violate laws against forced begging, abuse, and trafficking.

- Relevant authorities within the Ministries of Interior and Justice should monitor, investigate, and, where there is evidence, discipline police, investigating judges, and prosecutors who persistently fail to act on allegations of abuse and exploitation by marabouts.

- Issue clear directives to the Brigade des mineurs (Juvenile Police) to proactively investigate abuse and exploitation, including during street patrols.

- Increase police capacity, particularly within the Juvenile Police, including through increased staffing and equipment, in order to better enforce existing laws against forced begging and physical abuse.

- Provide adequate training to the Juvenile Police on methods for interviewing children, and for protecting and assisting victims of severe physical and psychological trauma, including sexual abuse.

- Ensure that children, aid workers, and others have a safe and accessible means of reporting abuse or exploitation, including by better publicizing the state’s child-protection hotline managed by the Centre Ginddi in Dakar, and by extending availability of hotlines and assistance elsewhere in Senegal.

- Introduce a law requiring humanitarian workers to report to the police incidents of abuse, exploitation, and violations of relevant laws governing the treatment of children, including the law on forced begging.

- Require all daaras to be registered and periodically inspected by state officials.

- Enact legislation setting minimum standards under which daaras must operate, with particular attention to daaras that operate as residential schools.

- Encourage child protection authorities to collaborate with Islamic authorities on the development of these standards, which should include: minimum hours of study; promotion and development of the child’s talent and abilities to their fullest potential, either within the daaras or in another educational establishment; minimum living conditions; the maximum number of children per Quranic teacher; qualifications for opening a residential daara; and registration of the daara for state inspection.

- Expand the capacity and mandate of state daara inspectors in order to improve the monitoring of daaras throughout Senegal; empower inspectors to sanction or close daaras that do not meet standards that protect the best interests of the child.

- Direct the Juvenile Police to investigate the extent to which sexual abuse exists in daaras throughout Senegal. Engage talibés, marabouts, the police, parents, community authorities, and Islamic and humanitarian organizations in establishing and publicizing adequate protection mechanisms for children who are victims of sexual abuse.

- Task a minister with coordinating the state response from the various ministries.

- Improve statistic-keeping on the number of talibés and Quranic teachers who come into contact with state authorities, including: talibés who are in conflict with the law; talibés who run away and are recovered by state authorities; and Quranic teachers who are arrested and prosecuted for forcing another into begging, physical abuse, or other abuses against children.

- Ensure the elimination of informal fees and other barriers to children accessing primary education in state schools.

To the Government of Guinea-Bissau

- Enact and enforce legislation that criminalizes child trafficking, including sanctions for those who hire, employ, or encourage others to traffic children on their behalf, and for those who aid and abet trafficking either in the country of origin or country of destination.

- Enact and enforce legislation that criminalizes forced child begging for economic gain.

- Publicly declare that forced child begging is a worst form of child labor; follow with appropriate legislation.

- Increase the capacity of civil and border police units, particularly in the regions of Bafatá and Gabú, to deter child trafficking and other illegal cross-border movements of children.

- Improve and require periodic training for border units to ensure that they know the laws governing movements of children across borders.

- Continue progress on the regulation of religious schools. Work closely with religious leaders to devise appropriate curricula, teacher standards, and registration and enrollment requirements.

- Ensure the elimination of informal fees and other barriers to children accessing primary education, in an effort to better progressively realize the right to education for the 60 percent of Bissau-Guinean children currently outside the state school system.

To the Governments of Senegal and Guinea-Bissau

- Improve collaboration to deter the illegal cross-border migration and trafficking of children from Guinea-Bissau into Senegal, including through additional joint training of border and civil police.

- Enter into a bilateral agreement to:

- formally harmonize legal definitions for what constitutes the illegal cross-border movement of children;

- coordinate strategies to deter the illegal cross-border movement of children; and

- facilitate the return of children who have been trafficked, and ensure that they receive minimum standards of care and supervision.

- Collaborate with religious leaders, traditional leaders, and nongovernmental organizations to raise awareness in communities on the rights of the child under international and domestic law, as well as within Islam.

To Religious Leaders, including Caliphs of the Brotherhoods, Imams, and Grand Marabouts

- Denounce marabouts who engage in the exploitation and abuse of children within daaras.

- Introduce, including during the Friday prayer (jumu’ah), discussion of children’s rights in Islam.

To International and National Humanitarian Organizations

- Explicitly condition funding for marabouts and daaras on the elimination of forced begging and physical abuse, and on minimum living and health conditions within the daara.

- Improve monitoring to determine if marabouts who receive funds are using them to achieve the prescribed goals.

- Cease funding for marabouts who demonstrate a lack of progress toward eliminating child begging, particularly those who continue to demand a quota from their talibés or who continue to physically abuse or neglect them.

- Implement organizational policies and codes of conduct requiring humanitarian workers to report to state authorities incidents of abuse and violations of relevant laws governing the treatment of children whom they directly encounter, including the 2005 law on trafficking and forced begging.

- Stop returning runaway talibés who have been victims of physical abuse or economic exploitation to the marabout. Bring the child to state authorities so that the Ministry of Justice can perform a thorough review of the child’s situation and determine what environment will protect the child’s best interests.

- Focus greater efforts on supporting initiatives in village daaras and state schools to enable children in rural areas to access an education that equips them with the basic skills they will need to participate fully and actively in society, so that children do not need to move to towns and cities to access quality education.

- Increase pressure on the government of Senegal to enforce its laws on forced begging, child abuse, and child trafficking.

To the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Slavery

- Consider an investigation into the situation of the tens of thousands of children in Senegal who are forced to beg by their Quranic teachers, which appears to qualify as a practice akin to child slavery.

To the Economic Community of West African States

- Work with governments in the region to improve collective response to child trafficking.

To the Organisation of the Islamic Conference

- Denounce the practice of forced begging and physical abuse in Quranic schools as in conflict with the Cairo Declaration and other international human rights obligations.

Methodology

This report is based on 11 weeks of field research in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau between November 2009 and February 2010. During the course of this research, interviews were conducted with 175 children; 33 religious authorities, marabouts, and imams in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau; Senegalese and Bissau-Guinean government officials at the national and local levels; diplomats; academics and religious historians; representatives from international organizations, including the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM); representatives from national and international nongovernmental organizations, national human rights groups, and community associations working in various ways to assist the talibés; and some 20 families in Senegalese and Bissau-Guinean villages who had sent their children to distant cities to learn the Quran.

In Senegal, research was conducted in the capital, Dakar; in the Dakar suburbs of Guédiawaye and Rufisque; in the cities of Saint-Louis, Thiès, Mbour, and Kolda; and in villages in the region of Saint-Louis in the north (area called the Fouta Toro, or the Fouta) and in the region of Kolda in the south. In Guinea-Bissau, research was conducted in the capital, Bissau; the cities of Bafatá and Gabú; as well as in villages in the eastern regions of Bafatá and Gabú. This field research was accompanied by an extensive literature review of publicly available and unpublished studies on the talibés in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau conducted by a range of international and local organizations.

Of the 175 children interviewed, 73 were interviewed during in-depth conversations, generally about one hour in length, in one of two types of centers that assist talibés: food and healthcare assistance centers for current talibés; and temporary shelters that assist in the care and repatriation of runaway talibés. These sites helped ensure a secure environment for the children, most of whom were victims of serious abuse, during and immediately after the time of their interview. Of the 73 children interviewed in centers, 14 were interviewed, at the children’s request, in small groups of between two and four children from the same daara; the other 59 interviews of children in centers were conducted individually and privately, with only a translator and the interviewer present.

An additional 102 interviews were conducted with current talibés living in daaras in four Senegalese cities: Dakar, Thiès, Mbour, and Saint-Louis. These interviews normally lasted from 10 to 15 minutes and were conducted away from their daara, generally on the street. About half of the street interviews were conducted in small groups of between two and five talibés, and the other half individually—depending on whether the children were begging in a group or alone. Privacy from other people on the street was ensured. Human Rights Watch did not interview children in or around their own daaras in order to help protect against acts of reprisal such as beatings by the marabout.

All interviews with talibés, marabouts, and families were conducted with the use of an interpreter between French and one of the main languages spoken by respective ethnic groups in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau. The vast majority of interviews were conducted in the interviewee’s first language—generally Pulaar, Wolof, or Creole.

The names of all current and former talibés interviewed for this report have been withheld in order to protect their identity and help ensure their security. The names of parents have also been withheld, even when consent was provided, to protect the identities of their children who remain under the care of the marabouts. The names of some government officials and representatives of nongovernmental organizations, at their request, have likewise been withheld.

Human Rights Watch identified and spoke with talibés, marabouts, and families with the assistance of humanitarian organizations that work with current and former talibés. Different local partners and translators were used in every city and, often, in each neighborhood in which research was conducted.

The exchange rate between the United States dollar and the West African CFA franc (the currency used by seven West African francophone countries as well as Guinea-Bissau) fluctuated from lows around 430 to highs around 490 from October 2009 to March 2010. In this report, all dollar figures use a rate of 460 CFA to the dollar.

Background

Senegal, the western-most country in continental Africa, has a population estimated at around 12 million, about 95 percent of which is Muslim. The largest ethnic groups in Senegal are the Wolof (approximately 43 percent of the population), Peuhl[1] (24 percent), and Serer (15 percent). Independent from France since 1960, Senegal’s official language according to the constitution is French,[2] though Wolof is generally the lingua franca. Arabic is the second most common language of literacy, even surpassing French—the language taught in state schools—in some regions of Senegal.[3]

Development of Islam in Senegal

The first article of Senegal’s constitution formally defines the state as secular.[4] However, Islamic authorities, particularly through the Muslim brotherhoods that dominate nearly all aspects of Senegalese life, wield considerable influence in the political and economic structures of the country.

The form of Islam prevalent in Senegal draws heavily from Sufism—a broad tradition that includes various mystical forms of Islam. The movement began during the eighth century as a reaction to what was perceived as the overly materialistic and worldly pursuits of many leaders and followers of Islam. Sufi adherents are almost always members of tariqas, or brotherhoods, and, in addition to learning the holy texts, place great importance on following the teachings and example of a personal spiritual guide.[5]

There are four principal Sufi brotherhoods in Senegal: the Qadriyya, the Tijaniyya,[6] the Muridiyya,[7] and the Layenne. The oldest order is the Qadriyya, but the current dominant brotherhoods are the Tijaniyya, to which approximately half of Senegal’s Muslim population adheres, and the Muridiyya, the wealthiest and fastest-growing, followed by some 30 percent of Senegalese.[8]

Each brotherhood maintains a strict hierarchy, led by a caliph, a descendant of the brotherhood’s founder in Senegal, followed by marabouts, who serve as teachers or spiritual guides for the brotherhood’s disciples, or talibés. Marabouts wield immense influence over their disciples: the talibé is expected to be devoted and strictly obedient; and the marabout, for his part, is expected to provide guidance and intercession throughout the disciple’s life.[9] Disciples consult marabouts for guidance on a variety of everyday and major life decisions and problems, such as family illness, a job search, and the harvest. Marabouts themselves are organized in a hierarchy, generally based on lineage, experience, and education. In addition, some marabouts in Senegal are imams, the leaders of mosques.

During the early colonial period, between 1850 and 1910, the French repressed charismatic religious leaders who, with their large followings, the colonial administrators feared could incite rebellion.[10] However, this served only to increase the religious leaders’ popularity.[11] By around 1910, the French and the brotherhood leaders began to see the political and economic benefits of adopting a more cooperative relationship. In return for the religious leaders’ pacifying the population and accepting colonial rule, the French relinquished to them immense profits from the production and trade of groundnuts—one of Senegal’s most important exports even today.[12]

Post-independence, the religious leaders’ political and economic power continued to grow. During the presidency of Léopold Sédar Senghor, from independence to 1980, caliphs from the main brotherhoods issued ndiguels (religious edicts, in Wolof), guiding followers to vote for Senghor and the ruling Socialist Party. In return, Senghor affirmed the brotherhoods’ preeminent religious authority in Senegal and provided them considerable economic benefits.[13] In 1988, in hailing the efforts of Senghor’s successor, President Abdou Diouf, to provide roads and lighting in Touba, the Mourides’ holy capital, the Mouride caliph issued a ndiguel that equated voting for the opposition with a betrayal of the Mouride founder.[14] The brazenness of this ndiguel resulted in a backlash against caliphs’ overt intrusion into political life, which led subsequent caliphs to adopt a superficially apolitical stance regarding support for a given candidate.[15]

While caliphs are nominally apolitical in today’s Senegal, politicking by politicians and political candidates of individual marabouts for their disciples’ votes remains an active practice in national and, even more so, in local elections.[16] Human Rights Watch interviewed marabouts in Dakar, Saint-Louis, Kolda, and Mbour who stated that during the last election cycle, in 2007, politicians or their intermediaries explicitly promised assistance in return for votes.[17]

These various forms of political courting of religious authorities, and political involvement by religious authorities, have over the years produced a political system in which no clear boundaries separate the religious and civic spheres.[18] While public expression of dissent toward the government is commonplace, the population and government leaders appear reluctant to express any opposition to religious leaders, an issue acknowledged by multiple government officials and humanitarian workers.[19] This dynamic has served to embolden those responsible for the proliferation of forced child begging and other abuses committed by the marabouts against talibé children.

Quranic Education prior to French Rule

The introduction of Islam in Senegal brought with it the founding of Quranic schools, or daaras. Prior to the arrival of the French—and even after their arrival in all but the most populous cities—Quranic schools were the principal form of education.

The daaras in existence before French colonial rule, as remain today, were led by marabouts, and the students were, then as now, known as talibés. While many talibés lived at home and studied at a daara in their village, many others were entrusted to marabouts in distant villages. The talibés lived with the marabout at the daara, often without any contact with their parents for several years.[20] While both girls and boys undertook memorization of the Quran in their own villages, it was and remains almost exclusively boys whom parents confide to the care of marabouts.

In these traditional daaras that predominated through independence, most marabouts were also cultivators of the land—though their primary concern generally remained education.[21] During Senegal’s long dry season, emphasis was generally placed on Quranic studies. Then, during the harvest, the marabout and older talibés would work together in the fields to provide food for the daara for much of the year—aided by contributions from families whose talibés did not reside at the daara and from community members through almsgiving. While older talibés assisted in the fields, younger talibés would remain in the daara and continue learning, either from the marabout or an assistant.[22]

During this period, the practice of begging existed where children lived at a residential daara and the harvest could not sustain the daara’s food needs. Mamadou Ndiaye, a professor at the Islamic Institute in Dakar who has studied the daara system for three decades, described how the practice of free boarding in Senegal’s Quranic schools led to the begging phenomenon.[23]

However, in the traditional practice, talibés generally did not beg for money; begging was solely for food and did not take time away from the talibés’ studies or put them on the street. Families would donate a bowl of food for a talibé, who would then return to the daara where all would eat as a community.[24] The experience emphasized mastering the Quran and obtaining the highest attainable level of Arabic. This traditional form of begging, however, bears little resemblance to current practice in Senegal’s cities. Indeed, Professor Ndiaye prefers to refer to these two practices using entirely separate terms: “la quête,” or collection, for the traditional practice; and “la mendicité,” or begging, for the modern practice which is the subject of this report.[25]

Quranic Education under French Rule

Despite the imposition of restrictive regulations and sanctions, as well as strategic subsidies for daaras where French was taught, the French authorities were unable to significantly restrict the proliferation of Quranic schools or limit the influence of Islamic authorities over the population.

Between 1857 and 1900, the French colonial administration tried to limit the number of marabouts authorized to teach children the Quran, first in the then-capital of Saint-Louis[26] and soon after throughout the region.[27] Correspondence between colonial leaders and the means they employed toward their goals demonstrated the central motivations behind these efforts: first, a desire to see the French language replace Arabic as the dominant scholarly and common language; and, second, a fear that Islam as practiced in West Africa was not favorable to colonial rule.[28] One colonial administrator wrote, “We are forced to ask ourselves what could be the utility of the study of the Quran as it is ... done in Senegal. The results from an intellectual point of view are negative.”[29]

An 1857 order required marabouts in Saint-Louis to gain authorization from the French governor in order to legally operate a daara. The set of requirements for authorization—which included proof of residency, educational certificates, and certificates of good morals—were intended to both limit the number of daaras and put out of practice individual marabouts whom the French believed to be hostile to their rule.[30] The order also required that all marabouts send their students of 12 years of age or older to evening classes at either a secular or Christian school in order to learn French.[31]

In 1896, the French administration extended this regulation throughout Senegal in an order that continued the use of restrictive authorization requirements; forbade marabouts from receiving children between the ages of six and 15 at Quranic schools during the hours of public education; and required marabouts to obtain from all their students a certificate proving attendance at French school.[32] If a marabout operated a daara without authorization, or failed to comply with the law, he could be punished with a fine and, for the first time, imprisonment.[33]

These acts angered the population, who saw them as meddling with their religious affairs.[34] Most children continued to attend Quranic schools and French spread slowly. Many marabouts continued to teach without authorization, and even those who had authorization generally failed to comply with official requirements.[35]

In the early 20th century, the colonial authorities continued attempts to limit the influence of Islam and Arabic in favor of French rule and language, but changed their approach, from the “stick” of over-regulation and punitive sanctions, to cooperation and cash payments to marabouts who set aside two hours a day for French instruction.[36]

In another proactive effort, the French in 1908 established the Madrasa of Saint-Louis. A school run by the colonial authorities, its purpose, as stated by the governor general of French West Africa, was “to fight against the proselytizing by those [hostile] marabouts and to improve the current, degraded teaching of Arabic through forming an official corps of marabouts.”[37] Scholarships were awarded with a distinct focus on attracting the sons of leading and influential families. The goal was to train future Senegalese political and religious leaders who would be more inclined to support the French.[38] The Madrasa’s curriculum included French, traditional school subjects, Arabic, and the Quran—prioritized in that order.[39]

Subsidies for Quranic schools that taught French and the training of religious and political leaders expanded the reach of the French language and French colonial authority. However, in most regions, parents continued to prefer traditional Quranic schools.[40] Throughout the entire colonial period, the traditional model of the daara—in which children assisted with the harvest and collected meals, but did not beg for money and instead spent the vast majority of their time on mastering the Quran—remained most prevalent. Ultimately unsatisfied with the results of the “carrot” approach as well, the colonial administration abandoned such attempts. A 1945 order stated that Quranic schools were not to be considered educational schools and were not to be given subsidies under any circumstances.[41]

Because the French authorities’ efforts were so explicitly intended to limit the influence of Islam and religious leaders, they have had a long-lasting impact on later attempts to regulate the daaras: nearly all proposed or enacted regulations have been immediately interpreted by religious leaders as anti-Quranic education and anti-Islam. When a number of marabouts in the post-independence period began to use Quranic education as a cover for the exploitation of talibés, the Senegalese government’s immediate and continued failure to challenge religious authorities on this point allowed an ever-worsening system of exploitation and abuse to develop.

Quranic Education Post-Independence: Rising Tide of Forced Begging

In the post-independence period since 1960, village-based daaras have increasingly given way to urban daaras, in which the practice of forced child begging has become more and more prevalent. Immediately following independence, village-based daaras remained the most common and were the sole option for a religious education, which was not provided by the secular state schools, still widely referred to as “French schools.” Then, severe droughts in the late 1970s brought an influx of migrants, including marabouts, from Senegal’s villages to its cities.[42] Unable to make use of the traditional forms of support as were available in the villages, many marabouts began forcing talibés to beg. By the 1980s, forced child begging was ubiquitous in Senegal’s cities, with profitability attracting numerous unscrupulous marabouts.[43] At present, the practice of child begging in Senegal is almost wholly linked to residential Quranic schools: a 2007 study by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the International Labour Organization (ILO), and the World Bank found that 90 percent of children begging in Dakar and its suburbs were talibés.[44]

While the government has categorically failed to respond to the known prevalence of exploitation and abuse of children associated with residential Quranic schools, it has made mild, unsuccessful attempts at larger reform of the education system. In an attempt to attract some families to the state education system, the Senegalese government introduced at independence the option of Arabic study in state schools,[45] but religious instruction was explicitly banned in state schools until 2004. Thousands of Senegalese families who prioritized religious education continued to send their children to daaras, contributing to the proliferation of Islamic associations and Arabic schools.[46]

At the onset of urban migration in the 1970s, many marabouts ran seasonal daaras, where marabouts and talibés would live in the city during the dry season and then return to the village to prepare for the harvest.[47] Then, as the profits obtainable from forced begging and the greater comforts of urban life became apparent, most marabouts remained in the cities all year. Professor Ndiaye explained these developments, and the negative effect that forced begging has had on children’s Quranic education:

Over time, the marabouts started to stay in the cities all year—they weighed the pros and cons and thought it was more favorable to stay in Dakar. Some marabouts became more at ease in Dakar—there was coffee, rice, fish, clean water. Why return to the village, where they had to work the land for long hours, when [in the city] a child comes daily with money, sugar, and rice? As a result, some marabouts reduced the hours of Quranic learning, because the longer the child remains in the daara learning, the less opportunity he has to bring money. The longer he stays outside the daara, the more the marabout can maximize the money that the talibés bring.[48]

Emphasis on Almsgiving

Academics and Senegalese humanitarian officials working with the talibés noted how almsgiving—both a central tenet of the Islamic faith and a widely practiced custom in Senegal—has had the effect of contributing to the entrenchment of the talibé problem, and as a result, the exploitation and abuses associated with child begging. Professor Ndiaye described this phenomenon:

In Senegal, people love to give alms.... People here need a population to give to. Disciples go to their marabout at crucial times—for example, when they want an important job—and the marabout will say that if they want to achieve this, they must give 50 CFA (US$0.11) to 10 talibés.[49]

This should not be construed to suggest that most Senegalese are in favor of the exploitative and abusive practices carried out against the talibés as detailed in this report. Rather, the attendant need felt by many Senegalese to give alms, coupled with the widespread presence of begging talibés, has at once been exploited by many marabouts and contributed to the normalization of the practice throughout Senegal.

Types of Quranic Schools Present Today in Senegal

Village Daara |

A form present in almost every Senegalese village, it generally preserves the traditional focus on memorizing the Quran. In many village daaras, children live at home with their families, attending state schools in the morning and the daara in the afternoon, or vice versa. Children residing at the daara assist the marabout with cultivation during the harvest and with other tasks such as the collection of wood and water. |

Seasonal Daara |

Almost nonexistent now, particularly in Dakar, marabouts and talibés live in cities during the dry season, with talibés generally forced to beg for money. During the rainy season, to prepare for the harvest, marabouts return to the village, often with the talibés who help cultivate. |

Urban Daara with Few or No Talibés Residing at the Daara |

Frequently led by imams at daaras connected with mosques, these daaras are overwhelmingly comprised of children who reside with their families in the surrounding neighborhood. Most of these children also attend state school. There is generally no begging. |

Urban Daara with Talibés Residing at the Daara |

Comprising the majority of daaras in cities, children often come from rural areas in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau to live and learn from a marabout. Under the pretext that begging is essential to sustain the daara and inculcate humility, many marabouts force their talibés to beg for long hours on the streets. The hours of actual Quranic education vary considerably. |

“Modern” Daara |

Though still relatively few in number, these daaras have introduced fields of study other than memorizing the Quran and learning Arabic, including French and state school subjects. Begging for money is generally not performed, as the modern daaras are often financed by inscription fees, religious authorities, the state, foreign aid, and humanitarian aid agencies. |

Exploitation and Abuses Endured by the Talibés in Senegal

Each of us has our own technique to survive.– Abu J., 12-year-old talibé in Saint-Louis[50]

In every major Senegalese city, thousands of young boys dressed in dirty rags trudge back and forth around major intersections, banks, supermarkets, gas stations, and transport hubs begging for money, rice, and sugar. Often barefoot, the boys, known as talibés, hold out a small tomato can or plastic bowl to those passing by, hoping to fulfill the daily quota demanded by their teachers, or marabouts, who oversee their schooling and, usually, living quarters. Typically the children are forced to beg for long hours every day and are beaten, often brutally, for lacking the tiniest amount. On the street they are vulnerable to car accidents, disease, and often scorching heat.

Inside the daaras, the boys are subjected to deplorable conditions and, at times, physical and sexual abuse from older boys. The boys are typically crammed into a room within an abandoned structure that offers scant protection against rain or seasonal cold. Many choose to sleep outside, exposed to the elements. Very few are fed by their marabouts; instead, they must beg to feed themselves, leaving many malnourished and constantly hungry. When they fall sick, which happens often, they seldom receive help from the marabout in obtaining medicines. Ultimately exploited, beaten, and uncared for, at least hundreds every year dare to run away, often choosing the hardship of a life on the streets over the abuse of life in the daara.

Forced begging places children in a harmful situation on the street and therefore meets the ILO’s definition of a worst form of child labor. Moreover, as the forced begging and gross neglect is done with a view toward exploitation, with the marabout receiving the child from his parents and profiting from the child’s labor, it amounts to a practice akin to slavery.

Large and Growing Problem

In the environment of all-powerful religious brotherhoods, limited government response, and the migration of marabouts to urban centers where forced begging has proliferated, tens of thousands of talibé children in Senegal, the vast majority under 12 years old, endure exploitation and severe abuses. Each year, more and more children fall victim to this system of abuse.

Precise estimates of the number of talibés forced to beg are difficult to ascertain, as children are constantly running away and marabouts, emboldened by the absence of government regulation, frequently open up new daaras. However, based on field research and censuses by academics and humanitarian workers interviewed for this report, Human Rights Watch estimates there to be at least 50,000 talibés in Senegal who are forced to beg with a view toward exploitation by their teachers, out of the hundreds of thousands of boys attending Quranic schools in total.

The Senegalese government’s enactment in 2005 of a law that criminalized forcing another into begging for financial gain, as well as efforts to improve conditions in daaras by local and international aid agencies, have failed to stem either the growing numbers of talibés or the serious human rights violations associated with the practice of forced begging and daara life. Evidence of the growing problem includes:

- A Senegalese government official working within the Ministry of Family, Food Security, Women’s Entrepreneurship, Microfinance, and Small Children (Ministry of Family) in Mbour (80 kilometers south of Dakar) registered a near doubling of daaras in the city between 2002 and 2009, including many in which marabouts subjected children to the practice of forced begging.[51]

- A government official who had previously worked in Ziguinchor (480 kilometers south of Dakar) told Human Rights Watch: “Ziguinchor is an example of the fast rise of the begging talibés phenomenon. Up until 1995, the city had barely encountered the presence of these talibés. Now there are thousands.”[52]

- According to an experienced local aid worker in Saint-Louis (270 kilometers north of Dakar), the number of talibés, including both those who are forced to beg and those who are not, has doubled since 2005 from an estimated 7,000 to 14,000.[53]

- According to the director of Samusocial Senegal, an international aid organization that provides healthcare to vulnerable street children in Dakar, including current and former talibés, “There has been an increase in 2009 in the number of street children in Dakar and a lowering in the age of the kids on the street.”[54]

Profile: Young and Far from Home

Of the 175 talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch, roughly half were 10 years of age or younger.[55] On average, the children had begun living at the daara at seven years of age, though Human Rights Watch interviewed talibés who arrived at the daara when only three years old.[56] Many talibés in Senegal are from neighboring countries, most notably Guinea-Bissau, and are thrust into a neighborhood or city where few people speak their language. Combined with their age and distance from home, they find themselves entirely dependent on the marabout, their fellow talibés, and, more often than not, themselves.[57]

The profiles of talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch suggest that the practice of forced begging is not limited to children of any one ethnic group, region, or neighboring country. While boys from the Peuhl ethnic group were disproportionately represented amongst the talibés interviewed in most cities—some 58 percent of the talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch were Peuhl, though the Peuhl ethnicity comprises only one-quarter of Senegal’s population—there were a large number of Wolofs as well. And while a large portion of the talibé population in Dakar hailed from Guinea-Bissau, they were a clear minority in most other Senegalese cities. No matter their places of origin, nearly all talibés who reside at the daara are far from home and rarely, if ever, in contact with their families.

Of the 175 talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the majority (about 60 percent) were Senegalese. However, there were also many from Guinea-Bissau (about a quarter of those interviewed) and smaller, though significant numbers of talibés from the Gambia and Guinea. Of all those interviewed, the majority came from the Peuhl ethnic group (nearly 60 percent) followed by the Wolof (40 percent).

Ethnicities of Talibés Interviewed by Human Rights Watch |

Places of Origin of Talibés Interviewed by Human Rights Watch |

|

|

While samples were insufficient to effectively estimate proportions of talibés by ethnicity or country of origin in each city, Human Rights Watch’s research revealed several distinct patterns of migration related to various cities:

- In Dakar, only about half the talibés interviewed were from Senegal, with almost as many hailing from Guinea-Bissau.[58] In some neighborhoods, over 90 percent of interviewees were from Guinea-Bissau, whereas in other neighborhoods, Senegalese predominated.[59] A clear majority were Peuhl, followed by Wolof and a few Serer.[60]

- In Saint-Louis, about 80 percent of talibés interviewed were from Senegal, followed by Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, and Mauritania.[61] Talibés of the Peuhl ethnicity comprised the overwhelming majority.

- In Thiès, about 60 percent of talibés interviewed were from Senegal. The largest number from a neighboring country hailed from the Gambia, with small percentages from Guinea-Bissau, Mali, and Mauritania.[62] Over half were Wolof, followed closely by Peuhl.

- In a limited number of interviews in Mbour, the vast majority of talibés interviewed were from Senegal, followed by the Gambia. All but one of the talibés were Wolof.[63]

The Story of Ousmane B., a 13-Year-Old Former Talibé[64]I am from the region of Tambacounda. My father decided to send me to learn the Quran when I was six. My mother didn’t want me to leave, but my father controlled the decision. The daara wasn’t a good place, and there were more than 70 of us there. If it was the rainy season, the rain came into where we slept. The cold season was also difficult. We didn’t have any cover and there were no mats, so we slept only on the ground. A lot of the talibés slept outside, because it was more comfortable. I did not have any shoes, and only one shirt and one pair of pants. The marabout had three sons, and when I got clean clothes, the marabout would take them from me and give them to his own children. The marabout paid for his children to go to a modern daara—they didn’t beg. When we were sick, the marabout never bought medicines. We would either come to centers where they would treat us, or we would use our own money to buy medicines. If I told the marabout I was sick and couldn’t beg, the marabout would take me to a room and beat me—just as if I was not able to bring the sum. So I had to go to the streets, even when I was sick. The normal hours for studying were from 6 to 7:30 a.m., 9 to 11 a.m., and 3 to 5 p.m. I begged for money and breakfast from 7:30 to 9 a.m., for money and lunch from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m., and for money and dinner from 5 to 8 p.m. When I first arrived, I had to bring 100 CFA (US$0.22) a day—that was the sum for the youngest. As I got older, the marabout raised the quota to 300 CFA ($0.65), half a kilogram of rice, and 50 CFA ($0.11) worth of sugar. I saw the marabout sell the rice in the community; he never used it to feed us. I have heard from talibés there now that the quota is up to 500 CFA ($1.09). Even then, it was very difficult for me to find the sum. It was easy on Friday, the holy day, but on many other days I had problems. When I couldn’t bring the quota, which happened at least every week, the marabout would take me into the room where the oldest talibés slept. Then he wrapped rope cord around my wrists and beat me with electric cable, over and over. I still have marks on my back (these marks were shown to Human Rights Watch). As bad as it was with the marabout, when he was gone it was even worse. The oldest talibés were really nasty. They would take our money and then beat us really badly if we missed the quota—I would just stay out and keep begging, sleep on the street if necessary. Begging is difficult. We ended up having to do whatever it took to get the daily sum, even steal. To be a talibé, it’s not easy. |

Nature of Forced Begging: Out of the Classroom and onto the Street

Begging is a difficult thing, because I would spend all day begging and sometimes I might end up with nothing.– Mamadou S., eight-year-old former talibé in Thiès[65]

In hundreds of urban residential daaras, the marabout appears to emphasize forced begging over learning the Quran. As one humanitarian worker who works closely with talibés told Human Rights Watch, “In the urban daaras, there is a pretext of education with a real purpose of exploitation.”[66]

In principle, the marabout is responsible for imparting mastery of the Quran and a moral education on the talibé. In practice, the talibés are the marabout’s workers, forced to spend long hours each day on the streets in search of money, rice, and sugar for the marabout—who uses almost none of it for their benefit. With education often secondary to fulfilling the quota, mastering the Quran takes two or three times longer than it would if the children received a proper education, according to Islamic scholars in Senegal.

Long Hours in Search of Money

While the traditional daara placed primary focus on mastering the Quran, the contemporary urban residential daara often focuses on maximizing the marabout’s wealth. Amadou S., 10, told Human Rights Watch that each day the marabout gathers the children at 6 a.m. and, before sending them off into the streets, encourages them by saying, “The rice is there, good luck!”[67] The talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch spent on average 7 hours and 42 minutes, spaced throughout the day, begging for either money or food.[68] Begging is therefore a full-time job for the talibés, generally performed seven days a week.[69]

The vast majority of marabouts in urban daaras demand a specific sum that the talibés must bring back each day.[70] This quota varies between daaras and even within an individual daara: the youngest and newly arrived are required to bring slightly less; those between eight and 15 years old must bring the most; and those over 15 are often exempt from begging.

For the 175 talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the average daily quota of money demanded by the marabout was 373 CFA ($0.87), except for Friday, where as a result of some marabouts setting higher quotas to take advantage of greater almsgiving on the holy day, the average quota was 445 CFA ($0.97).[71] In a country where approximately 30 percent of the population lives on less than a dollar a day,[72] and the gross domestic product per capita is approximately $900,[73] this is a considerable and often difficult sum to achieve. The quota varies greatly by city, as shown in the text box below, but the hours spent begging each day are remarkably consistent. The principal difference is that Dakar is a far richer city, which results in a higher quota.

Average Begging Quota in CFA and Hours by City | |||

|

Normal Days |

Friday |

Hours |

Dakar |

463 |

642 |

7 hrs, 42 mins |

Saint-Louis |

228 |

228 |

7 hrs, 36 mins |

Thiès |

254 |

268 |

7 hrs, 54 mins |

Mbour |

246 |

246 |

7 hrs, 18 mins |

In addition to money, many marabouts require that their talibés bring back sugar and uncooked rice. Just over 50 percent of talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch had a quota for either rice or sugar, around 14 percent had a quota for both rice and sugar, and 35 percent only had to bring whatever they could. The daily quotas ranged from half a kilogram to three kilograms of rice, and from 50 to 100 CFA ($0.11-$0.22) worth of sugar.

In daaras where quantities of rice or sugar are demanded, every talibé told Human Rights Watch that none of what they brought back was ever used for their own consumption. The account of Samba G., eight years old, was typical of what occurred in daaras with high rice quotas or a large number of talibés: “When you brought in the rice, the marabout would fill up large [50-kilogram] bags. When they were full, he would send them back to his village or he would sell them in the neighborhood.”[74] A 50-kilogram bag of rice sells for around 20,000 CFA ($43.50) in Dakar.

As the forced begging is done “with a view” toward exploitation, with the marabout receiving the child from his parents and profiting from the child’s labor, it amounts to a practice akin to slavery.[75]

Going to the City: Suburban Talibés’ Holy Day on Dakar’s StreetsIn one of the most exploitative practices, many marabouts in Dakar’s suburbs force their talibés, either explicitly or indirectly, through an elevated quota of 750 ($1.63) to 1,500 CFA ($3.26), to travel into Dakar from Thursday to Saturday in order to maximize their earnings. They beg around the main mosques in Dakar, particularly on the Friday holy day when Senegalese give greater alms. Human Rights Watch interviewed over a dozen talibés from different suburbs, including Guédiawaye, Mbao, Pikine, and Keur Massar (ranging from 10 to 30 kilometers outside Dakar), and the vast majority said that they engaged in this practice. An 11-year-old talibé in Keur Massar described waking up at 5 a.m. on Thursday to catch public transport into Dakar, hopping off and walking when caught not paying. He, like the others, would then beg all day Thursday before sleeping on Dakar’s streets Thursday night. A full day of begging on Friday follows, either with a return to the suburb on Friday night or, more often, another night on the street before returning Saturday morning. Rather than attending mosque with their talibés on Friday, marabouts are widely subjecting children to 16-hour work days and nights on the streets. |

Injury and Death from Car Accidents

The hours spent on the street begging put talibés at considerable risk of injury and death from car accidents. It is a common sight to see talibés, some as young as four years old, weaving precariously between cars on major streets, approaching cars as they pull into and out of driveways and in inter-city transport hubs, and sticking their hand or bowl into car windows in the hopes that alms will be given.

Human Rights Watch documented four cases of death as a result of car accidents, and interviewed nine talibés who had been victims of car accidents, with injuries ranging from soreness and bruises to multiple broken bones. In addition, a marabout interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that an eight-year-old talibé under his de facto guardianship had in late 2009 suffered breaks to both of his legs in a car accident.[76] A father of a former talibé told Human Rights Watch that his son had in 2006 suffered a serious injury to his arm as a result of a car accident in Dakar, which still affected him three years later.[77]

While a small sample, all four deaths documented by Human Rights Watch occurred in Dakar—not surprising given the greater level of traffic in the capital. All the deaths and injuries documented happened while the talibés were begging. A 2007 study on begging children in Dakar noted that the conditions on the street inherently expose begging children to dangers, particularly illnesses and car accidents.[78] Likewise, government officials and directors of international humanitarian organizations and local human rights organizations all related to Human Rights Watch that the dangers on the street, including from car accidents, placed the talibés in an extremely vulnerable position for long hours each day.[79]

Pape M., 13, witnessed the death of a friend and fellow talibé in a car accident in Dakar in 2007. He emotionally told Human Rights Watch:

My friend—we begged together—was killed by a car. It happened when the sun was almost down, during the cold season. We were out begging and a car hit him. It was a big car. I don’t know how it happened. The car just hit him and he died, right next to me. The car stopped and people came around. People were shouting at the driver. I think he was taken to the hospital—someone took him in a car—but he died. I never heard the marabout talk about it.[80]

Two other talibés told Human Rights Watch that a fellow talibé in their daara had been killed by a car accident, but neither was present when it happened.[81]A traditional chief in Guinea-Bissau lost a talibé nephew to a car accident in Dakar, concluding that “the practice of forced begging on the street is truly terrible for the children.”[82]

Nine talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch described having suffered injuries from car accidents. Bouba D., nine years old, was injured while begging near the transport terminal in Thiès:

I was hit at the place where the cars leave.I was standing on the side of the road begging near one station wagon when another car came by and struck me. It wasn’t bad—I didn’t break any bones. But several other talibés from my daara have been struck by cars here too, and they have suffered broken bones. One his leg, one his arm. Accidents happen frequently.[83]

Similarly, Ibrahima T., 13, related:

I was hit by a motorbike once and hurt my knee. I was on the side of the road—the road from Dakar to Rufisque—but the motorbike came off the road and struck me. My knee still hurts sometimes, and this was several years ago. The marabout never took me to the hospital.[84]

The frequent accidents demonstrate one of the many ways that forced begging meets the ILO definition of a worst form of child labor and constitutes a violation of the child’s right to physical security and protection from injury, and, in cases of death, a violation of the right to life.[85] The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) requires the state to take all appropriate measures to safeguard the children’s right to physical and mental security. Marabouts, as de facto guardians, are failing to act in the best interests of the child as is also required under the CRC.[86]

Denying the Right to Education

The limited time talibés spend in Quranic classes in most urban daaras, as compared with the time spent begging, brings into question not only the motives of the marabouts, but also the relative value of education received in the daaras.

The number of hours the talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch spent in classes varied greatly—from less than one hour per day to as much as eight hours. However, they almost unanimously described spending more time begging for money and food than they spent in the classroom learning the Quran. On average, they spent nearly eight hours a day begging and only five hours a day scheduled for Quranic classes.

Talibés from several daaras made clear that the hours of study were strictly enforced; however, in the majority of daaras from which talibés were interviewed, it was clear that scheduledhours far surpassed actual hours of learning. Human Rights Watch interviewed tens of talibés in the street in the midst of hours that they said were set aside for studying; when asked why they were not in class at the daara, they universally responded that they would not go back until completing the quota. In addition, many talibés said that the long hours on the street make it difficult for them to concentrate even while at the daara, due to hunger and general fatigue.

The result is that in many urban residential daaras, the talibés’ progress in learning to master the Quran and read and write Arabic, as well as their ability to access education in other basic skills, is severely undermined by the marabouts’ apparent prioritization of begging over classroom time. One marabout in Mbour told Human Rights Watch: “I have never begged my talibés because I want them to learn. The most important part of the apprenticeship is the Quran, and the hours of begging take away from that.”[87] The president of ONG Gounass, a humanitarian organization in Kolda that works closely with daaras in the region and operates a modern daara, likewise related:

The student is there supposedly learning the Quran. But there are many children that pass 10 to 15 years in the daaras and they know neither the Quran nor a true understanding of Islam. They leave the daara without any skills and without even knowing the Quran.[88]

The right to education under the CRC includes an education “designed to empower the child by developing his or her skills, learning and other capacities, human dignity, self-esteem and self-confidence.”[89] Where a child barely learns the Quran and no other educational material, this right is clearly left unfulfilled. Article 7(b) of the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam gives parents the right to choose the form of education for their children, so long as they take into consideration the child’s interests;[90] and article 9(b) states that “[e]very human being has a right to receive both religious and worldly education.”[91] While Quranic education can therefore be an integral part to a child’s self-development, tens of thousands of talibés in Senegal are failing to receive either a religious education or an education in other basic skills.

Severe Physical Abuse

Each time I was beaten, I would think of my family who never laid a hand on me.– Abdou K., 11-year-old former talibé[92]

The overwhelming majority of talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported suffering repeated, often severe, physical abuse in the daara. Beatings were most frequently reported within the context of failing to return the daily quota, although there were tens of talibés who were also beaten for failure to master the Quranic verses. The physical abuse was perpetrated by the marabout himself or, to a lesser extent, an older talibé, or “grand” talibé, who served as an assistant teacher.[93]

Talibés typically described being taken to a room, stripped of their shirt, and beaten with an electric cable or a club—usually struck repeatedly on the back and neck. Some were subjected to stress positions, chained to a piece of furniture, or bound or shackled during the beating. More than 20 talibés revealed to Human Rights Watch welts and scars resulting from beatings they had received. The children expressed profound levels of fear at what would await them should they fail to meet the marabout’s established quota.

Malick L., a 13-year-old former talibé, showed Human Rights Watch the scars from the beatings he had suffered at the hands of his marabout more than a year before. He recounted his experience, which was typical of many other talibés interviewed:

When I could not bring the quota, the marabout beat me—even if I lacked 5 CFA ($0.01), he beat me. It was always the marabout himself. He took out the electric cable and we went to the room. I stood there and ... he hit me over and over, generally on the back but at times he missed and hit my head. I still have marks on my back from the beatings.[94]

Not surprisingly, all but one of the talibés interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had run away from their daaras said that they had been beaten repeatedly for failing to bring enough money; the other was brutally beaten for mistakes in memorizing the Quran. Of the 139 current talibés interviewed, 77 percent described being beaten for failing to collect the quota. Human Rights Watch believes that this percentage may be even higher, given the apparent fear among children interviewed in groups, particularly on the street, that other talibés might report to the marabout what had been discussed with the researcher.[95]

Of those who described being beaten for failing to collect the quota, the overwhelming majority stated that it happened each and every time that they could not bring the quota. Other talibés described being beaten only after being given a “second chance” to complete the quota, as Boubacar D., 12, told Human Rights Watch:

If we cannot bring the quota one day, our name is put on the board with the sum we owe. We are in debt. If we cannot bring it all the next day, then we are beaten badly with electric cable.[96]

Every talibé but one stated that the punishment was inflicted by the marabout himself or with his clear knowledge and endorsement—since he was, at a minimum, physically present when some of the beatings occurred.[97]

Determining the precise frequency of the beatings is difficult, as many of the talibés are very young and conceptions of time are not always accurate. All but one former talibé interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they suffered the beatings at least once a week, and many said two or three times. Among current talibés, answers varied from very rarely to every day.[98] A large number of talibés said that their beatings were particularly common on Saturdays and Sundays, since there are far fewer people on the streets to give money.

During in-depth interviews, talibés identified a number of different objects that marabouts and other teachers had used to beat them. Most commonly cited was electric cable (39 cases, including one in which a long strip of iron was attached to inflict additional damage), followed by a club (13 cases), a cane (six), a whip (four), a hand (three), a tire strip (three), rope cord (two), and “whatever is lying around” (two).

Human Rights Watch also documented multiple cases of marabouts using stress positions to accompany beatings.[99] Chérif B., 11, told Human Rights Watch:

If I can’t bring the quota, then the marabout beats me with an electric cable or a club. He takes us into a room and brings other talibés in to watch. Every time he forces us to hold our ears and move up and down as he strikes us—he keeps striking while we do this until we tumble over. If we tumble over right away, he starts again.[100]

Eight talibés described being chained or bound with rope during beatings by their marabout or an assistant.[101] Ibrahima T., 13, recounted being repeatedly bound and beaten in a daara in a Dakar suburb before running away in 2009:

Every time I could not complete the quota by 10 a.m., one of the grand talibés would take me into a room and chain me around my ankles. Then he would beat me with electric cable or a tire strip—the strikes were too numerous to count. After he finished, the grand talibé would leave me there, chained, until seven at night, sometimes beating me again.... The punishment was the same for arriving late. If I came back after 10 a.m., even with the quota, I was chained until nighttime and beaten—the marabout was very strict about it.[102]

One marabout employed a particularly heinous method of punishment, in which he forced the youngest talibés to brutalize each other or suffer additional consequences (see text box of the story of Laye B. below).

The talibés almost universally described the beatings—and the fear of a coming beating when they were unable to collect the quota—as the worst abuse in the daara. Babacar R., 14, related:

Begging is too difficult because if I do not have the daily quota, the grand talibé beats me. He hits me everywhere—on the head, the back, everywhere, and over and over. It’s difficult, it’s very painful.... I want to return home and work in my village. I don’t want to be here.”[103]

Moreover, the gross neglect, deprivation, and serious human rights abuses endured by tens of thousands of talibés at the hands of many marabouts are augmented when, as is common, the marabout is either absent or leaves the daara for days or even weeks. Human Rights Watch documented 18 cases in which the marabout lived in a house separate from the daara where the talibés slept, including some instances when the marabout only came to the daara on certain days.[104] Tens of talibés described how their marabouts left the city multiple times a year to return to home villages—sometimes for holidays, sometimes to bring back more talibés.[105] In each of these daaras, talibés as young as four are left under the supervision of older talibés, generally around 18 years old. Under such circumstances, older talibés are responsible for frequent beatings, stealing money from younger talibés, and sexual abuse.[106]

Talibés who said that they were not beaten generally acknowledged another form of dangerous punishment: refusing entry into the daara. Talibés in these daaras said that while their marabout did not strike them, they could not come back to the daara until they completed the quota. This restriction often resulted in their begging late into the night or, alternatively, sleeping on the streets.[107] In only around 7 percent of Human Rights Watch’s interviews did talibés say that there was no punishment at all for failing to bring the quota.