"Get the Gun!"

Human Rights Violations by Uganda's National Army in Law Enforcement Operationsin Karamoja Region

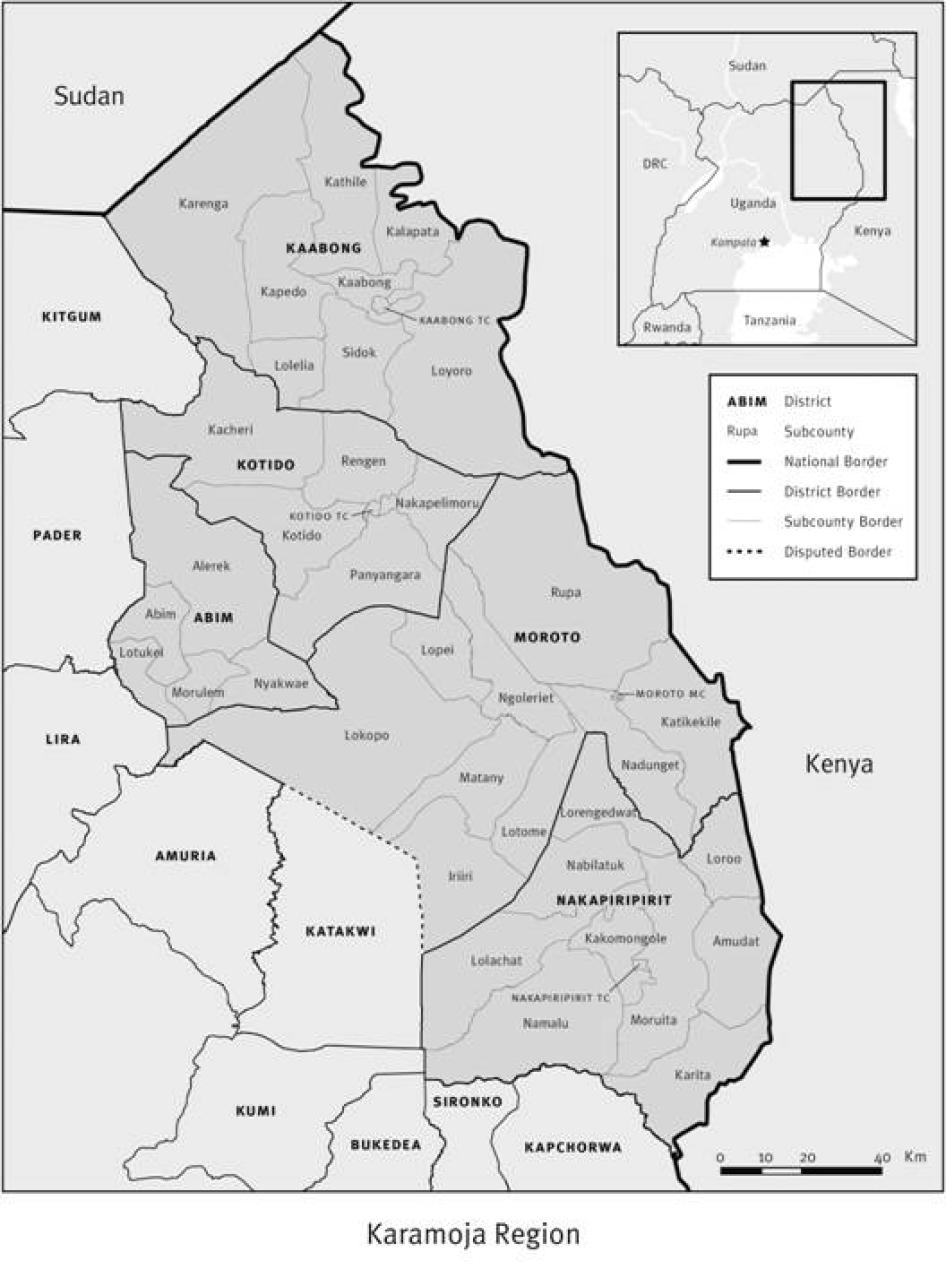

Map

2007 John Emerson

I. Summary

The soldiers asked, "Why are you here?" We said, "We don't know why we are here." Then they said, "You are here because we want the gun."If you say, "I don't know about the gun," the soldiers get the stick and begin beating you . They say, "Get the gun! Get the gun!"

-I.N., detained in Kaabong barracks, September 2006

I heard the army vehicles and just ran out. I was trying to run but I saw that the soldiers were already there surrounding the [homestead]. I didn't even know I was shot until I lay down and saw the blood.

-B.P., young girl shot during disarmament operation, Kaabong district, December 2006

In the remote Karamoja region of northeastern Uganda, pastoralist herding communities struggle for survival amidst frequent drought, intercommunal cattle raids, and banditry. Gun ownership is pervasive, and armed criminality and cattle raiding by civilians in Karamoja exposes the population there, as well as those in neighboring districts, to high levels of violence, and restricts even the movement of humanitarian workers. It poses significant challenges to the government's responsibility to provide for its citizens' security and human rights.

Since May 2006 the national army, tasked with law enforcement responsibilities in the region in the absence of an adequate police presence, renewed a program of forced disarmament to curb the proliferation of small arms. In so-called cordon and search disarmament operations, soldiers surround villages in the middle of the night and at daybreak force families outside while their houses are searched for weapons.

This report, based primarily on field research in Kampala and in the Kaabong and Moroto districts of the Karamoja region in January and February 2007 and additionally drawing on reporting by the United Nations (UN) and other sources, documents alleged human rights violations by soldiers of Uganda's army, the Uganda Peoples' Defence Forces (UPDF), in cordon and search disarmament and other law enforcement operations in the region. These violations have included unlawful killings, torture and ill-treatment, arbitrary detention, and theft and destruction of property. While the Ugandan government has a legitimate interest in improving law and order in Karamoja, including stemming the proliferation of illegal weapons, it must do so in a manner consistent with human rights.

Human Rights Watch welcomes steps taken by the Ugandan government in the past year to curb such human rights violations during disarmament and other law enforcement operations, in response to international and domestic pressure. The Ugandan government, however, has not adequately held to account those responsible for past abuses, and allegations of human rights violations continue to surface periodically in connection with disarmament and other law enforcement operations in Karamoja.

The government has mounted several disarmament campaigns-some voluntary, some forced-in Karamoja since 2001 to collect what it now estimates to be as many as 30,000 unlawfully-held weapons in the region. At the same time, however, government programs to improve security, including programs of disarmament, face a fundamental dilemma: guns are used to defend from raiders as well as to rob and steal. The dynamics behind weapon possession in Karamoja include, for some, the desperate need to secure and defend their cattle and access to limited resources essential for their cattle, a matter of life and death. Removing weapons while not providing sufficient guarantees of safety and security renders, in their view, many communities vulnerable to attack.

Weak government institutions in the region exacerbate these vulnerabilities and leave law enforcement responsibilities in the hands of the UPDF. The present disarmament campaign is just one of these responsibilities, which also include recovering raided cattle, apprehending and prosecuting criminal suspects, and protecting livestock in UPDF-guarded enclosures.

In Kaabong district in December 2006 and January 2007, UPDF soldiers shot and killed 10 individuals, including three children, as they attempted to flee during cordon and search operations.Only one of the individuals killed was reported to have fired on the soldiers, while one other was running away with his gun. Four other individuals, including two children and one youth, were also shot and injured.In four armed confrontations with Karamojong communities between October 2006 and February 2007, at least two of which were preceded by cordon and search operations, dozens of civilians were killed, while the lives of an unknown number of UPDF soldiers were also claimed.

Soldiers routinely beat men, at times to uncover the location of weapons. In Moroto district victims of three cordon and search operations described an almost identical pattern of mass beatings by soldiers of the entire male population: men were first rounded up outside of their homesteads, and then subjected to collective beatings with sticks, whips, guns, and tree branches accompanied by soldiers' demands that they "get the gun."

Following cordon and search operations, soldiers detained men in military facilities. Although one UPDF spokesperson described such detentions-purportedly for the purpose of inducing the surrender of weapons-as lasting no longer than 48 hours-Human Rights Watch interviewed some men who were detained without access to family members for at least two weeks. Former detainees reported to Human Rights Watch that military authorities subjected them to severe beatings and violent interrogations, along with deprivation of food, water, and adequate shelter.

Communities were also the victims of property destruction and theft. During one cordon and search operation, soldiers drove an armored personnel carrier through a homestead, crushing six homes, and narrowly missing a crowd of people.

By conducting cordon and search operations to seize weapons, rather than to prosecute firearms offenses, the government may be seeking to avoid legal requirements authorizing searches, arrest, and detentions in the context of law enforcement operations and that protect the rights of persons under national and international law. Consequently, post-cordon and search detentions lack judicial control, and, at times, are not specific to individuals suspected of criminal activity, thereby violating the rights to be free from arbitrary arrest and detention. Moreover, searches conducted during these operations are authorized by military order alone, and not court-issued warrants mandated under national law, violating individual privacy rights.

In response to allegations of human rights violations during disarmament operations, the government of Uganda has taken several steps. These include launching four investigations; developing a set of internal UPDF guidelines governing the conduct of military personnel during cordon and search operations, the violation of which subjects a soldier to discipline under the UPDF Act; providing UPDF soldiers conducting cordon and search operations with human rights training; and engaging with community members and local leaders about the goals of disarmament.

These steps appear to have had an encouraging effect. The most recent information received by Human Rights Watch indicates that cordon and search operations, while still ongoing, have been markedly less violent than in earlier months of the disarmament campaign and accompanied by far fewer allegations of human rights violations. But allegations of human rights violations, most notably continued detention following cordon and search operations and isolated reports of beatings, have not ceased altogether. Moreover, none of the reports produced by government investigations have been made public. The Ugandan army wrote to Human Rights Watch in September 2007 that a number of soldiers have been brought to justice for human rights violations, but provided no details of the underlying offenses and punishments imposed. In the three explicitly disarmament-related cases of which Human Rights Watch is aware, soldiers were disciplined for petty theft.

Accordingly, although it has taken steps in the right direction, Human Rights Watch calls on the Ugandan government to make further progress in stopping human rights violations by its forces. It should end impunity for violations by its soldiers by investigating and prosecuting or disciplining abuses where appropriate, and safeguard against future violations by revising its disarmament policies to comply with its human rights obligations under national and international law.

Publicity garnered by the disarmament campaign has concentrated national and international attention on the challenges of survival and security in Karamoja; some of these challenges are imposed from within and some from without. The Ugandan government's efforts to respond to allegations of human rights violations in the past year have included increased engagement with the people of Karamoja, who have long been alienated from the rest of the country. To ensure the sustainability of efforts to bring security to the region, the Ugandan government, with the support of the international community and with the communities of Karamoja leading the way, should seize this opportunity to develop durable solutions that reduce conflict and reliance on guns for protection of lives and livelihoods in Karamoja.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Uganda

Publicly acknowledge and condemn human rights violations committed by government forces in the course of forced disarmament operations in Karamoja.

End impunity for human rights violations committed by soldiers of the Uganda Peoples' Defence Forces (UPDF) and its auxiliary forces during cordon and search operations. Promptly, impartially, and transparently investigate and discipline or prosecute as appropriate all allegations of human rights violations, including unlawful killings, arbitrary arrests and detention, torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, and destruction of property.

Expedite reforms in cordon and search operations procedures to ensure their compliance with international human rights law. Review in particular their compliance with protections against arbitrary search, arrest, and detention, and, to the extent such protections are not extended under Ugandan law to UPDF-conducted law enforcement operations, amend Ugandan law accordingly.

Compensate victims of unlawful killings, torture and ill-treatment, arbitrary detention, and looting by government forces adequately and speedily.

Convene a commission of independent experts on pastoralist livelihoods, arms control, and human rights to examine the relationship between livelihoods, conflict resolution, and arms proliferation in Karamoja. The commission, drawing on the existing Karamoja Integrated Disarmament and Development Programme (KIDDP) draft, and guided by a prioritization of human rights, should recommend revisions to KIDDP and coordination with other existing government policies, including the National Action Plan on Arms Management and Disarmament. The commission should seek the input of relevant government ministries, the Uganda Human Rights Commission, the National Focal Point on Small Arms and Light Weapons (NFP), and local elected officials, traditional leaders, and civil society representatives from Karamoja.

To Donor Countries and International Development Partners

Call on the Ugandan government to expedite reforms to cordon and search operations procedures to ensure the legality of these operations, and to investigate and prosecute human rights violations by its forces.

Condition support for the Karamoja Integrated Disarmament and Development Programme (KIDDP) or any policy with a disarmament component on the compatibility of any such disarmament operations with the Ugandan government's human rights obligations under national and international law.

To the United Nations Country Team

Continue, through the leadership of the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, to closely monitor the Ugandan government's compliance with national and international human rights standards in its policies addressed to the Karamoja region, including disarmament.

Increase, where possible, the activities of appropriate UN agencies in Karamoja to bolster human rights, humanitarian assistance, and civilian protection.

Detailed recommendations are given in Chapter VII.

II. Methodology

Human Rights Watch carried out research for this report in Uganda in January and February 2007. In Kaabong and Moroto districts, Human Rights Watch spoke with 51 eyewitnesses about cordon and search and other law enforcement operations conducted by the national army, the Uganda Peoples' Defence Forces (UPDF), between September 2006 and January 2007, and visited the sites of six of these operations. In Kampala, Human Rights Watch spoke with two groups of women living in the Kisenyi area who had migrated from Moroto district.

Interviews were conducted in local languages with the assistance of translators. Most interviews were conducted individually, although they often took place in the presence of others. In several instances where interviews were conducted with multiple villagers rather than one-on-one, they are cited as group interviews.

Human Rights Watch also conducted telephone and in-person interviews in Uganda with representatives of international nongovernmental organizations, United Nations agencies, donor governments, UPDF spokespersons, and other persons with knowledge of livelihoods and human rights in Karamoja. Additional information for this report was gathered in New York and London between November 2006 and September 2007 through phone and in-person interviews, email communications, and desk research.

Where necessary, names have been withheld or replaced by initials (which are not the interviewee's actual initials) to protect identities.

III. Background

The remote Karamoja region of northeastern Uganda, stretching across 10,550 sparsely populated square miles,[1] is home to several traditionally agropastoralist groups. For the Karamojong, as these groups are collectively known, restrictions on access to grazing lands across international and district borders have made survival amidst harsh environmental conditions-including frequent drought-more difficult. Successive governments have also marginalized the area, leaving it with the lowest development and humanitarian indicators in Uganda,[2] weak governmental institutions, and little support for alternative livelihoods.

Within these wider challenges of development, serious insecurity including cattle raiding, banditry, and road ambushes, exacerbated by pervasive use of illegal weapons, presents a significant law and order problem in Karamoja. During the period July 2003 to August 2006, at least a thousand lives were lost in cattle raids, armed clashes, banditry, and law enforcement operations.

The present National Resistance Movement government under President Yoweri Museveni has tasked the national army, the Uganda Peoples' Defence Forces (UPDF), with law enforcement responsibilities in the region. These responsibilities include armed operations to recover raided cattle and to arrest criminal suspects, and (as was the case under previous colonial and post-independence regimes) programs of disarmament. It is in this context that serious human rights violations by military personnel are reported to have taken place, particularly in the period since the government launched a new program of forced disarmament in May 2006.

A. Livelihoods and Insecurity in Karamoja

While the several ethnic groups of agropastoralists who live in northeastern Uganda are referred to collectively as Karamojong,[3] they constitute three distinct groups: the Dodoth to the north in Kaabong district; the Jie in central Karamoja in Kotido district; and the Karimojong to the south in Moroto and Nakapiririt districts.[4] Other smaller groups in Karamoja include the Pokot, the Tepeth, and the Labwor.[5] The population of the region is just under one million persons according to the 2002 census.[6]

In Karamoja, agropastoralism-livestock herding accompanied by cyclical migrations of people and animals and supplemented by settled agricultural cultivation-represents a specific response to environmental conditions that make agriculture difficult to sustain reliably.[7] Failed or poor crops occur in approximately one out of every three years, making livestock products an essential source of sustenance.[8]Pastoralism in Karamoja thus "is the only [subsistence] strategy that works consistently, given the ecological realities of their universe."[9] Notably, a recent study by the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) in Uganda found that while only 11 percent of households in a sample drawn from the eight counties of Karamoja derived more than half of their income from livestock and were thus classed as agropastoralists, agropastoral households had the lowest prevalence of food insecurity or moderate food insecurity in the region.[10]

Migration is a key element in this strategy, allowing for the movement of herds between pasture areas in response to environmental pressures.[11] During the rainy season, herds are grazed near to permanent homesteads or manyattas, with cattle camps or kraals[12]moving out to distant grazing lands during the dry season.[13] Men, women, children, and the elderly are present at both manyattas and kraals, resulting in a "constant flow of people, information, and livestock."[14]

Movements by some groups reach into the neighboring Acholi, Lango, and Teso regions of Uganda, and into Kenya.[15] Access to grazing land outside of and between sections of Karamoja, however, has been restricted over time by government policy beginning in the colonial period-including the imposition of a fixed border between Uganda and Kenya[16]-and continuing in the post-independence era.[17] Conflict between groups within Karamoja, particularly within the Karimojong beginning in the late 1970s, has also curtailed grazing areas internal to Karamoja.[18]

While livelihood strategies vary across Karamoja and groups engage in livestock keeping, agriculture, and other economic activities in differing degrees-often reflecting underlying ecological and historical differences[19]-the Karamojong regard themselves as cattle people. Livestock herding is essential to both cultural identity and livelihood,[20] and the rights to both are protected by international law.[21]

While sharing much in common with neighboring groups in Kenya and Sudan,[22] the pastoralism of Karamoja and its attendant cyclical migrations of people and livestock is largely unique within Uganda. Policies of colonial administrations and post-independence regimes alike have tended toward marginalization of pastoralism in the region:government initiatives have been directed historically almost wholly toward increasing the sustainability of settled agriculture and the assertion of central control.[23] According to one observer, these initiatives, including animal confiscations and restrictions on mobility,[24]contributed to the present impoverishment of Karamoja by increasing competition over scarce, degraded resources, which in turn amplified the consequences of devastating droughts in the 1960s-80s.[25]

Competition over scarce resources contributes to high levels of insecurity in Karamoja. Conflicts between groups, including across international borders, and within the Karimojong group, conflict between its major territorial sections the Matheniko, the Pian, and the Bokora,[26] take the form of cattle raids. Traditionally, cattle raiding redistributed livestock "relieving grazing pressure on fragile grasslands," effected political realignments and population distribution, and permitted the quick recovery of livestock losses.[27] The frequency of raiding increases with drought, disease, and other environmental stressors.[28]

Cycles of raiding and counterraiding between and within groups, however, now engender high levels of violence. As an example, there were 474 raids and 1,057 lives lost (including the lives of at least 45 women and children) during the period July 2003 to August 2006, according to data from only a handful of reporting sites in Karamoja collected by the Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism (CEWARN) of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD).Although other violent incidents-including armed clashes, disarmament operations by the Ugandan military, banditry, and even demonstrations-were also reported during the period, CEWARN attributes most of the violent deaths reported in the region to raiding.[29]

Bokora women from Moroto district, who say they have been forced by the combined effects of drought, government programs of disarmament, and cattle raids to migrate seasonally to Kampala to generate income, described to Human Rights Watch living under the constant threat of raiding:

At you start to get anxious, you start worrying. [The raiders] come as early as 4 or

The enemies come at night. They climb fences and come inside the ekidor [main gate] of the homestead. Presently we have no animals. They take property . If they are not in the mood of killing, they burn your house. They lock the house and burn you in the hut. The frequency [of raids] really varies. It can be once a week . [If there is] no moon [by which to see at night], no raid. At any other time of month [they] raid.

[I left home because of] hunger, insecurity from cattle rustlers, and disarmament . The two pressures [of raids and disarmament] at the same time-you can't really handle it.[30]

Violence associated with cattle raiding is also periodically felt outside the borders of Karamoja. Cattle raids in the 1980s decimated herds in the neighboring Teso, Acholi, and Lango regions.[31] Raids continue to contribute today to the prolonged internal displacement of an estimated 130,000 persons in Amuria and Katakwi districts.[32] In areas of the Acholi region bordering Karamoja, persons displaced primarily due to the Lord's Resistance Army insurgency now cite Karamojong raids as a chief source of insecurity.[33]

The violence associated with cattle raiding is often linked to the wide availability of small arms in the region.[34] No reliable estimate exists of the number of firearms-primarily AK-47 assault rifles-in circulation in Karamoja; reported estimates range from 30,000 to 200,000,[35] while the Ugandan Ministry of Defence claims that there are 30,000 guns in illegal possession in Karamoja.[36] With a population of just under one million persons in the region, the Ministry of Defence's estimate would amount to approximately one gun for every 30 persons.Active gun corridors running across international borders to the north and east,[37] rebel groups,[38] sale by members of the UPDF and its auxiliary forces,[39] attacks on armed members of other Karamojong groups and government security personnel for the purpose of stealing weapons,[40] and direct arming of local militias by district and central governments[41] are all contemporary sources of arms.

Armed violence in the region has also taken on other forms only loosely connected to traditional cattle raiding.Armed theft of cattle for personal gain and commercial profit, spurred by the arrival of a cash economy and opportunistic businessmen in Karamoja, is common,[42] as is banditry, including road ambushes. A report by the Uganda office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) chronicles at least eight ambushes during the period November 16, 2006, to March 31, 2007, involving 14 murders.[43] In one of these incidents, 15 women gathering firewood in Nakapiripirit district were ambushed in January 2007.Nine of the women, two of whom were pregnant, were killed, while the remaining six were injured.[44] Road conditions can be so insecure that international nongovernmental organizations working in the area have adopted various security protocols for inter-district travel, including following public buses, which are reported to be rarely the target of ambushes. Outside of towns, United Nations (UN) agencies are required to travel with armed escorts in all districts.[45] In May 2007 the WFP temporarily suspended operations after one of its drivers was shot and killed in a road ambush in Kotido district.[46]Widespread local opinion attributes banditry to failed or deterred raiders.[47]

Armed criminality and cattle raiding by civilians in Karamoja poses significant challenges to the government's responsibility to provide for its citizens' security and human rights. At the same time, however, government programs to improve security, including programs of disarmament, discussed below, face a fundamental dilemma: guns are used to defend from raiders as well as to rob and steal.

The dynamics behind weapon possession in Karamoja include, for some, the need to secure and defend their cattle and the limited resources essential for their cattle, a matter of life and death.Removing weapons while not providing sufficient guarantees of safety and security renders, in their view, many communities vulnerable to attack. As a result, at the level of each small community guns are a rational feature of pastoralist life in Karamoja, given intensified competition over scarce resources between groups, all with access to arms, the absence of alternative supports for pastoralist livelihoods, and, as discussed immediately below, effective state security institutions.[48]

B. Government Approach to Law and Order in Karamoja

The near absence in Karamoja of civilian law and order institutions exacerbates high levels of insecurity and criminality and rationalizes recourse to self-help by local communities. A draft planning document issued by the Ugandan Office of the Prime Minister in 2005 states: "Very few civil servants are willing to work in conditions of constant insecurity which is the norm in Karamoja. As a result Government infrastructure has been destroyed or broken down. Police posts, prisons quarters, and District Farm Institutes have totally been demolished or simply abandoned to run to ruin."[49]

Although the government announced plans in March 2007 to recruit an additional 30 police officers per subcounty in Karamoja,[50] as of August 2006 there were as few as 137 police officers of the central Uganda Police Force in the entire region.[51] With a population just under one million, the ratio of central police officers to population would have been 1:7,300, about one-sixteenth that of the UN standard of 1:450 and one-quarter that of the national ratio of 1:1,800[52].

Government-sponsored security institutions that do exist are often auxiliary forces drawn from the local population and provided with limited law enforcement training; desertion from such forces has left weapons in circulation in the region in the past.[53] Auxiliary police units-Anti-Stock Theft Units (ASTUs)-have been deployed along the borders of Karamoja to prevent cattle raiding into neighboring regions, and an expansion of the program into Karamoja itself was announced in July 2007.[54] Human Rights Watch has expressed concern, however, that the limited training provided during the related recruitment of "special police constables" in the neighboring Acholi region of northern Uganda may have been insufficient to protect against human rights violations by these forces and to ensure effective, professional policing.[55]

Other law and order resources are similarly scarce. There is no high court presence in the region.[56] The districts of Nakapiripirit, Abim, and Kaabong lack any judicial presence altogether.[57] This means that in Nakapiripirit district, for example, criminal suspects must be transported over 100 kilometers to the nearest magistrate judge in Moroto town.[58] There is a prison in every district apart from Kaabong.[59]

In this vacuum, the responsibilities tasked by the President Museveni government to the UPDF are extensive. They include armed operations by UPDF soldiers to recover raided cattle as well as to track and apprehend criminal suspects.

In instances of the former, UPDF soldiers have at times partnered with the raided community-including in at least one case providing members of the Bokora community with guns-to track cattle.[60]Cattle recovery operations by the UPDF have also led to violent confrontations between UPDF soldiers and armed members of Karamojong communities. In February 2007, as discussed further below, the UPDF claims that its soldiers encountered a stolen herd while on routine patrol in Kotido district. According to UPDF spokespersons and a subsequent statement by the Ministry of Defence, a fierce confrontation between UPDF soldiers and herdsmen over several days left a reported four soldiers and at least 52 armed civilians dead.[61]

(UPDF soldiers have also taken on responsibilities for livestock protection. The UPDF claims to have branded over 150,000 heads of cattle to discourage raiding,[62] and has established UPDF-guarded kraals at army barracks in some areas. In Kaabong, the UPDF-guarded kraals have provided some protection, although the kraals have still been vulnerable to raids.[63] Access of cattle owners to the kraals is restricted, impairing collection of livestock products for food and the use of oxen for agriculture.[64] Further, it is not clear how these kraals will be compatible with necessary migrations. Herds are normally broken up into smaller groups than the size of the herds currently kept in some of the UPDF-guarded kraals,and, as indicated above, migrations are usually accompanied by men, women, and children;these factors pose logistical and protection challenges.[65])

Apprehending criminal suspects can also bring the UPDF into conflict with local communities. In January 2007 UPDF soldiers engaged in a firefight with residents of a village in Lotome subcounty, Moroto district as they entered the village while tracking suspects who had killed nine women collecting grass in Nabilatuk subcounty, Nakapiririt district a few days earlier. (The incident is discussed in detail in Chapter V.A.)

Civilians tried by courts martial

Apprehension of criminal suspects is sometimes followed by prosecution before courts martial (two men accused of the murder of the nine women mentioned immediately above were court martialed and received nine and ten years' imprisonment, for example[66]). Uganda law provides for civilians to be tried under military jurisdiction, including for the unlawful possession of arms "ordinarily being the monopoly of the Defence Forces."[67] This jurisdiction has been challenged before the Ugandan constitutional court, but has been upheld by a vote of three-to-two, at least where civilians are charged under the UPDF Act jointly with military officials.[68] According to the spokesperson for the UPDF Third Division, although UPDF soldiers sometimes do hand over "warriors"-a term commonly used to refer to armed members of Karamojong communities-for prosecution before civilian courts, "the military courts are faster. People themselves ask us to use military courts. They have lost faith in the civilian courts. We don't have time to wait for civilian courts. We are doing the work of the police."[69]

C. Government Disarmament Policies in Karamoja

Disarmament has been another key element in the President Museveni government's law and order strategy for Karamoja, as it had been for previous governments.[70] The present government launched its first effort to disarm the Karamojong and to secure the region shortly after it came to power in 1986.[71] Reportedly accompanied by human rights violations, in the view of one commentator, the "campaign apparently succeeded only in intensifying the hostitility of northern pastoralists toward the government in the south. Subsequently, armed looting of government and nongovernment facilities and convoys became the chief strategy for [Karamojong] recovery and resistance."[72]

Concerted attempts by the government to disarm Karamojong communities were renewed in 2000. In March of that year, politicians from neighboring regions affected by Karamojong cattle raids succeeded in passing a resolution in parliament calling for a program of disarmament in Karamoja.[73] A disarmament campaign was formally launched in December 2001.[74]

The disarmament campaign had a deadline of February 15, 2002, for the voluntary surrender of weapons. Preceded by an extensive mobilization campaign, which reached out to women, local politicians, and kraal leaders, and offering incentives including "an ox-plough, a bag of maize flour, and a certificate as a token of appreciation" to those individuals who handed in weapons, the two-month initiative succeeded in securing the surrender of approximately 10,000 weapons.[75]

After the expiry of the deadline for voluntary surrender of weapons, however, the strategy was shifted to one of military-driven forced disarmament, using "cordon and search" operations involving the creation by UPDF soldiers of a secure perimeter around manyattas and kraals, which are then searched for weapons.[76] There were soon reports of human rights violations: according to interviews conducted in Karamoja by one observer in March and April 2002, these included killings, beatings, rape, and looting.[77] An Irish priest, Fr. Declan O'Toole, who reported to the UPDF and his embassy beatings he witnessed during disarmament operations in Nakapelimoru, Kotido district on March 9,[78] was shot dead along with two companions by UPDF soldiers on March 21, 2002.[79] Within days, on March 25, two soldiers were executed publicly by UPDF firing squad in Kotido town for his murder.[80]

The 2001-02 disarmament was ultimately unsuccessful. A draft government planning document attributes this in part to the redeployment of the UPDF from Karamoja to elsewhere in northern Uganda to fight a resurgent Lord's Resistance Army, claiming this left behind inadequate troop strength to provide protection to communities that had surrendered their weapons, as well as a failure to provide promised incentives in exchange for weapons.[81] In addition, the use of force led to a loss of trust and support among Karamojong communities and leaders for the disarmament.[82]

Insecurity escalated. According to one observer, groups retaining weapons, along with the UPDF itself, "sought to test [potentially new balances of military power] by raiding those thought to be less well-armed. Seldom has there been raiding in so many directions at once at the same time."[83] Uneven patterns of disarmament thus left some groups in Karamoja vulnerable to the raids of those groups still with arms. There is evidence that the present round of disarmament in 2006-07 is having the same consequence for some communities.[84]

The disarmament also paradoxically brought an influx of weapons into the region. Some groups who were disarmed and then raided by their neighbors rearmed for their own protection.[85] Pian home guards were directly rearmed by the government after uneven patterns of disarmament left the Pian vulnerable to raids.[86] In addition, the central government initially established local defense units (LDUs) in Karamoja, as well as in neighboring regions, as a component of the disarmament program to provide security against raiding. In Karamoja, the LDUs, which were never clearly under police or military supervision as a matter of law,[87] were permitted to retain their weapons, which were then registered as government property.[88]Instead of residing in their communities, however, the LDUs were placed in mixed units, under central UPDF command,[89] and some were taken to fight the Lord's Resistance Army insurgency.[90] This led to high desertion rates as the initial understanding of LDU recruits within Karamoja that "they would reside in the community and be able to protect their own cattle and people and with money to feed their own families" was disappointed.[91] Deserting LDU soldiers took their weapons with them or, lacking clear supervision, simply used them for their own ends.[92] At the same time, fear of locally raised self-defense forces in neighboring Lango and Teso regions-the Arrow and Amuka boys-spurred acquisition of weapons within Karamoja.[93]

In September 2004 President Museveni revived disarmament as a priority.[94] In the interim, national commitments to conflict resolution, including through disarmament, arms control, peacebuilding, and development in Karamoja, were strengthened by their inclusion in the 2003-04 revision of the Ugandan government's key development framework, the Poverty Eradication Action Plan (PEAP). [95] The revised PEAP also called for implementation of the National Action Plan on Arms Management and Disarmament (NAP).[96] This is a comprehensive framework for implementation of the government's various commitments to arms control under international and regional agreements,[97] and is administered by a National Focal Point (NFP) housed in the Ministry of Internal Affairs.[98]

As launched in 2004, the new disarmament initiative was primarily voluntary, with provision for forcible disarmament as a last resort. A new round of consultations with stakeholders in Karamoja was undertaken by President Museveni and other government officials.[99] At the same time, the Office of the Prime Minister and international development partners, led by the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), began to seek out a framework for disarmament that would capitalize on lessons learned from 2001-02 by coupling disarmament with development interventions. The result, after intensive consultations, was a draft Karamoja Integrated Disarmament and Development Programme (KIDDP).[100]

Not yet formally launched, the KIDDP continues to be discussed within the government, the donor community, and UN agencies. At this writing, the present draft, dated January 2007, sets out seven "programme components." These include programs directed at improving security through disarmament, regional arms control, preventing raids, and the development of community security arrangements; strengthening law and order institutions; increasing the provision of social services; and developing alternative livelihoods. The draft, however, prescribes very little sequencing of disarmament and development interventions, and the first six months of programming heavily prioritize disarmament.[101] As a result, observers have expressed concern that the KIDDP as presently drafted does not provide adequate incentives for voluntary disarmament in the absence of first providing realistic alternatives to reliance on guns for the protection of livestock and livelihoods, as discussed above. The draft also continues to provide for forced disarmament through cordon and search operations, albeit as a last resort.[102]

D. Return to Cordon and Search Disarmament, May 2006-Present

In May 2006, while the KIDDP was under discussion in the Office of the Prime Minister and various working groups in Kampala, President Museveni directed the UPDF to begin cordon and search disarmament operations. This directive was spurred by the slow pace of voluntary disarmament-between November 1, 2004, and April 30, 2006, only 1,697 guns were surrendered[103] -and what the Ministry of Defence characterized as a sharp increase in armed crime in Karamoja.[104]

Cordon and search operations

Human Rights Watch interviewed two UPDF spokespersons about cordon and search operations; these spokespersons provided slightly different accounts of a typical operation.

According to the Ministry of Defence/UPDF spokesperson, Maj. Felix Kulayigye, in a typical cordon and search operation UPDF soldiers surround an area identified through intelligence-gathering as having a certain number of firearms. Once this cordon is in place, the army commander then informs the local leaders, including the kraal leader and the local councilors[105] of the presence of the army and the nature of the disarmament. All individuals are then requested to exit the homesteads-manyattas-within the cordon.[106]

Soldiers conduct a search of the manyattasand collect any firearms. The owners of firearms collected by or surrendered to the UPDF are given certificates to document their disarmament.[107] Major Kulayigye claimed that once the search is completed, UPDF personnel leave the area, although any individual who resists disarmament by firing on soldiers may be arrested.[108]

However, according to Lt. Henry Obbo, the UPDF spokesperson for the Third Division (the division of the UPDF conducting the disarmament operation in Karamoja), after a search is completed, men from the cordoned area are escorted to so-called "screening centers" located within nearby army facilities. With the assistance of local leaders, the men are checked against a list the UPDF claims to have of all gun owners. If an individual is on the list, he is kept at the screening center.[109] If an individual is not on the list, he is released, unless he is otherwise wanted by the police or the military on suspicion of other crimes, including road ambushes and forcibly resisting disarmament by shooting at soldiers. In those cases, the individual is turned over to the police under the civilian criminal justice system or placed in military detention to face a court martial.[110]

According to Lieutenant Obbo, men detained at the screening center are held for one to two days. They are not arrested for unlawful possession of firearms. Instead, local leaders inform the families of the detained men that they should bring the men's guns to the barracks to secure their release. Obbo stated that even if relatives have not turned in guns to the barracks, no one is detained beyond one to two days.[111]

Major Kulayigye, however, insisted that arrest and detention of men for the purpose of forcing the surrender of weapons had occurred early on during the disarmament, but was an act of "indiscipline and never authorized by policy.[112] In a subsequent response to a letter from Human Rights Watch setting out the key findings of this report, Major Kulayigye acknowledged that "some persons are inconveniently rounded up and taken to screening centers" where "the wanted are sorted out from the innocent and later detained as investigations go on," but that these screening centers are "not military detention centres or facilities."[113]

Human Rights Watch does not know the exact number of cordon and search operations that have been carried out since the disarmament campaign was launched in May 2006. It is likely that they have varied in frequency from place to place. For example, eight cordon and search operations were recorded in Moroto district, 12 in Kotido district, and two in Nakapiripirit district between the start of the disarmament and June 15, 2006.[114] In Kaabong district, cordon and search operations were reportedly as frequent as twice a week in the initial months of disarmament, but as few as nine operations were carried out during the period September 2006 to January 2007.[115] The member of parliament for Pokot county in Nakapiripirit district estimated that each of the approximately 125 villages in his constituency has been subject to four cordon and search operations since May 2006.[116]

Scale of alleged human rights violations connected with UPDF operations

According to a Ministry of Defence news release, 1,008 guns had been recovered through these cordon and search disarmament operations as of March 2007.[117]Allegations of human rights violations by UPDF soldiers, including killings, detentions, beatings, rape, and the destruction of property, however, also surfaced almost as soon as these operations began anew in May 2006. Already as of June 15, 2006, sources reported that the disarmament and related operations had claimed 23 civilian lives, including in exchanges of fire between soldiers and armed civilians, left 22 civilians injured, and resulted in 279 arrests in Kotido, Moroto, and Nakapirpirit districts, while the UPDF had collected 663 guns.[118]

During the period October 29, 2006, to March 31, 2007, OHCHR reported that at least 161 and possibly as many as 189 civilians were killed in cordon and search operations and other UPDF-conducted law enforcement operations. The reported deaths took place allegedly under various circumstances, including, critically, exchanges of fire between soldiers and armed civilians. They included deaths during four cordon and search operations,[119] two UPDF operations of an unspecified nature,[120] one UPDF cattle recovery operation,[121] the operation to apprehend murder suspects in Lotome subcounty, Moroto district that spawned a confrontation with the local community (mentioned above and discussed in detail below in Chapter V.A),[122] and-accounting for the vast majority of deaths-two armed confrontations between the UPDF and Karamojong communities in Lopuyo village, Kotido district in October 2006[123] and in Kotido subcounty, Kotido district in February 2007 (also discussed in more detail in Chapter V.A, below.)[124] OHCHR also reported that UPDF soldiers were killed during some of these and other incidents:an unknown number were killed during the confrontation in Lopuyo in October 2006;[125] four were killed in Lotome in January 2007;[126] seven were killed in Kotido subcounty in February 2007;[127] and three soldiers were killed in attacks on February 19, 2007, in Koblin village, Moroto district and on March 10, 2007, in Loroo subcounty, Nakapiripirit district.[128] In addition, OHCHR reported cases of torture, arbitrary arrests, and destruction of property.

In response to these and other allegations,[129] the government of Uganda has taken several steps to curb human rights violations by its forces. These steps, discussed in greater detail below,[130] include launching four investigations; developing a set of internal UPDF guidelines governing the conduct of military personnel during cordon and search operations, the violation of which subjects a soldier to discipline under the UPDF Act; providing UPDF soldiers conducting cordon and search operations with human rights training; and engaging with community members and local leaders about the goals of disarmament. The most recent information received by Human Rights Watch indicates that cordon and search operations, while still ongoing, have been markedly less violent than in earlier months of the disarmament campaign and accompanied by far fewer allegations of human rights violations.

As this report demonstrates below, however, UPDF forces are alleged to have committed serious human rights violations in the course of cordon and search and other law enforcement operations in Karamoja since May 2006, and the government of Uganda has not yet taken steps to provide adequate accountability for the majority of these violations. In addition, the failure to make applicable the procedural safeguards that ordinarily attach to civilian law enforcement operations leaves those subject to UPDF operations in Karamoja vulnerable to arbitrary searches, arrests, and detentions, as well as heightens the risk of other serious human rights violations occurring during the conduct of UPDF operations.

IV. Legal Standards Governing UPDF Law Enforcement Operations

A. International Law

Under international law, military personnel carrying out policing duties-such as searches, arrest, and detention-are bound by the same human rights standards applicable to all law enforcement officials.[131] Many of these same standards-including protections against the arbitrary deprivation of life, torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, and arbitrary searches, arrests, and detentions, articulated more fully below-are binding on government agents as a matter of Ugandan law.[132]

With regard to confrontations between Uganda Peoples' Defence Forces (UPDF) soldiers and armed members of Karamojong communities, international law distinguishes between armed conflict and internal disturbances and tensions. International humanitarian law (the laws of war) is primarily applicable to the former, while the ordinary principles of international human rights law govern the latter.

Violent confrontations between the UPDF and armed members of Karamojong communities do not appear to have risen to the level of an armed conflict under international law. Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 applies in cases of "an armed conflict not of an international character";[133] the authoritative International Committee of the Red Cross "Commentary"to the Geneva Conventions distinguishes between non-international (internal) armed conflicts and acts of banditry and unorganized and short-lived insurrections for which the conventions do not apply[134]-the clashes in Karamoja appear to be cases of the latter. The Second Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol II) applies only to non-international armed conflicts that are characterized by conflict between the national army and armed opposition groups "under responsible command" that "exercise such control of a part of [the state's] territory as to enable them to carry out sustained and concerted military operations."[135]

Elders and kraal leaders exercise authority over their individual groups, including raiding parties. However, the Karamojong groups-themselves often acting in opposition to one another-do not altogether function under a "responsible command."[136] And their occasional confrontations with UPDF soldiers do not have the character of "sustained and concerted military operations." Instead, these confrontations are more of a piece with "riots" and "isolated and sporadic acts of violence," international disturbances and tensions to which international human rights law-and not international humanitarian lawapplies.[137]

Unless confrontations with armed members of Karamojong communities rise to the level of an armed conflict, the applicable international law will be human rights law.The Ugandan government's international human rights obligations include the fundamental injunction that force used by law enforcement officials, including members of armed forces, must be both necessary and proportional.[138] The rights to life, including against arbitrary deprivation, and to be free from torture permit no derogation.[139]

Civilians who commit criminal acts during violent confrontations with government authorities should be prosecuted under domestic law in accordance with international fair trial standards.But even while restoring internal order, the Ugandan government has a legal obligation to protect and respect the human rights of all individuals within its territory.[140]

B. National Law

Human Rights Watch sought clarification from the government of Uganda by letter of July 23, 2007, as to whether procedures under Ugandan law regulating searches, arrest, and detentions in the context of civil law enforcement operations or pursuant to the military's prosecution of civilians for firearms offenses-to the extent the latter exist, as discussed below-are applicable as a matter of law to UPDF operations (the letter is included in this report as Annex II). The response received by Human Rights Watch from the Ministry of Defence/UPDF spokesperson's office (included as Annex III) did not provide details as to the procedures that must be followed under national law for UPDF-conducted law enforcement operations. Instead, the response referred generally to the UPDF's jurisdiction to try unlawful possession of firearms, discussed below, and to the Ugandan parliament's authorization of UPDF involvement in disarmament in its March 2000 resolution.[141]As far as Human Rights Watch is aware, Ugandan law does not set out the specific procedural safeguards that must be followed in the authorization of searches, arrests, and detentions by UPDF personnel.

Although the UPDF and the Uganda Police Force are independent organs under the Ugandan constitution and governed by different acts of parliament,[142] UPDF "officers and militants" enjoy the "powers and duties" of police officers in assisting civil authorities where a "riot or other disturbance of the peace is likely to be beyond the powers of the civil authorities to suppress or prevent."[143] Assuming the UPDF could be understood to be assisting the civil authorities through its law enforcement operations in Karamoja, its personnel would be bound by the same procedural safeguards-discussed in more detail in Chapter V.D, below-attached to searches, arrests, and detentions by police officers.

An alternative source of authority for UPDF-conducted searches, arrests, and detentions may lie in its authority under the UPDF Act to prosecute civilians for unlawful possession of firearms. As noted above (see Chapter III.B), the military shares jurisdiction over firearms offenses with civilian courts.[144] However, it is unclear under the UPDF Act to what extent the military may undertake searches, arrests, and detentions of civilians or civilian property.

The terms of the UPDF Act appear ordinarily to limit the subjects of UPDF powers of search to service members and property occupied by military personnel,[145] and the power of arrest to service members.[146] However, the UPDF Act does provides for the appointment of special personnel to "detain or arrest without warrant any person subject to military law [who] is suspected of having committed a service offence" and to "exercise such other powers as may be prescribed for the enforcement of military law."[147]

With regard to detentions, persons arrested under the UPDF Act are to be handed over immediately to either civilian or military custody, but the UPDF Act does not specify whether civilians may be committed to military custody.[148] Ordinarily, the Ugandan constitution prohibits detention in "ungazetted" facilities, that is, facilities not published in the official gazette by the minister of internal affairs; UPDF barracks are not gazetted.[149]

In the case of cordon and search operations, a further complication arises in assessing the applicable body of national law. As noted above (see Chapter III.D), according to a spokesperson for the Third Division these operations are conducted to seize illegal weapons, with no intent to charge persons with offenses under civilian or military law. He and the Ministry of Defence/UPDF spokesperson said that the only arrests carried out during disarmament operations for the purpose of charging with offences under military or civilian law are of people who resist disarmament, such as by firing on soldiers.

By restricting the aim of cordon and search operations in this way, the government may be attempting to avoid legal requirements authorizing searches, arrest, and detentions in the context of criminal prosecution. To the extent national law would allow for the use of the military to search private homes, and to arrest and detain individuals without charge in military facilities, however, such practices violate Uganda's obligations under international law, as discussed in the next chapter.

V. Human Rights Violations in UPDF Operations in Karamoja

During a field visit to Karamoja in late January/early February 2007, Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed victims of and eyewitnesses to nine cordon and search operations, as well as the January 2007 confrontation between Uganda Peoples' Defence Forces (UPDF) soldiers and Karamojong communities in Lotome subcounty, Moroto district.[150] Information about three other confrontations between UPDF soldiers and Karamojong communities, at least two of which were preceded by cordon and search operations, were collected from public reports of the Uganda office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the national print media, and interviews with UPDF spokespersons and other knowledgeable sources.[151] The findings of Human Rights Watch's research in Uganda tends to substantiate allegations of unlawful killings and other excessive force, torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, arbitrary detention, and destruction of property during UPDF-conducted law enforcement operations in Karamoja.

The Ministry of Defence/UPDF spokesperson's office, writing to Human Rights Watch in September, has denied that four of the operations described below took place at all.

A. Unlawful Killings and Excessive Use of Force

International law protects the individual's right to life,[152] including from unlawful killings by state agents.[153] As a corollary, law enforcement officials may only use firearms in exceptional cases, with restraint, and even then as a last resort.[154]

Lopuyo, Kotido district, and Morungole, Kaabong district, October 2006

On October 29, 2006, separate cordon and search disarmament operations in Lopuyo village, Rengen subcounty, Kotido district, and in the Morungole hills area of Kaabong district, led to violent clashes between the UPDF and the local population.

According to a local elected leader and other unidentified sources, as reported in a national newspaper, the clash in Lopuyo between the UPDF and armed men of a Jie community on October 29 was sparked when soldiers conducting a cordon and search operation shot dead six youths participating in a traditional dance and a UPDF major was then killed by members of the community.[155] A UPDF spokesperson told Human Rights Watch that reports the UPDF fired first were incorrect.[156]

According to an investigation by OHCHR (which does not purport to resolve whether one side or another initiated the clash), approximately 48 civilians, including women and children, and an unknown number of UPDF soldiers, including the major, were killed that day.[157] Allegedly, soldiers summarily executed six people and arbitrarily killed another four who were among 25 men they locked inside a building and fired upon through an open window; six others were injured. Soldiers allegedly raped an elderly woman.[158]Soldiers also allegedly set fire to 23 manyattas, rendering at least 1,133 people homeless, some of whom reportedly fled to the bush to escape further violence.[159]

OHCHR also reported that a retaliatory attack and looting by armed civilians the following day, October 30, on civil servant quarters in nearby Kotido town caused the displacement of an estimated 702 individuals.[160] One child was wounded in the attack.[161] Separately, a policeman and a teacher were killed in a road ambush attributed to armed civilians near to Kotido town on October 30.[162] Humanitarian agencies, including the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Caritas, Oxfam, and the Church of Uganda, provided emergency assistance to persons displaced by the violence.[163]

The clashes in the Morungole hills area, which also began on October 29, received comparatively less national attention. In a letter published in the government-owned New Vision newspaper, President Museveni stated that a UPDF helicopter gunship "inflicted serious damage to the cattle thieves" during these clashes.[164] According to the unverified reports of a knowledgeable source who spoke to Human Rights Watch on condition of anonymity, soldiers acting on information that the people who had taken their cattle to the area were heavily armed and also that some criminals were hiding in the hills approached the area from three directions in the early hours of October 29. Several firefights between the soldiers and members of the community ensued, with the UPDF ultimately resorting the following day to the use of helicopter gunships (as confirmed by President Museveni's statement in his letter to the editor, quoted above) and tanks. Information collected by the source, but unverified by Human Rights Watch, indicates that at least 17-19 UPDF soldiers and an unknown number of civilians were killed; some of these civilians may have died from lack of medical care.[165]

Kalodeke ward, Lokolia parish, Kaabong district, December 7, 2006

Eight individuals were killed as they attempted to flee during a cordon and search and stolen cattle recovery operation in Kalodeke ward, Lokolia parish, Kaabong subcounty on December 7, 2006.[166]

On the day of the operation, soldiers surrounded the manyattas at about 5 a.m. Witnesses estimated that there were around 300 soldiers on foot, who were described as all armed with automatic weapons and grenades, and accompanied by three military vehicles:[167]

At first we thought some enemies [cattle raiders] had come but then we realized it was the soldiers. When we saw the military vehicles we knew these were soldiers. We saw the soldiers and they started firing. They started spraying bullets. They killed six people from my village and two people from the other village.[168]

A husband, wife, and three of their children were among the eight killed as they attempted to flee.[169]The deceased couple's remaining child, a six-year-old boy, was shot in the hand as he followed after his family.He told Human Rights Watch,

We came out of the village with our parents. I was following my mother and father and I got shot. My mother was shot in front of me and fell down. Then I was shot . One bullet went through [my] fingers.[170]

A girl, age about 10-12, was shot in the thumb of her right hand. She told us,

I heard the army vehicles and just ran out [of the manyatta]. I was trying to run but I saw that the soldiers were already there surrounding the manyatta. I didn't even know I was shot until I lay down and saw the blood.[171]

The men were rounded up outside of the manyattas and questioned; all but one were taken a short distance away to the center of the parish, and from there some of the men were taken to Kaabong barracks.[172] Cattle and goats were confiscated; while some were later returned, some were given to another community that claimed they had been stolen."Only one of the men from here was involved in [cattle] raiding, but they blamed us all and took all the cows," a Kalodeke resident told us.[173]

Soldiers also told the women and children to get outside, apart from a few who were tasked with opening up the granaries in the manyatta so the soldiers could search inside.

The young boy and girl who were shot and injured lay in the field for some four hours until the soldiers left the area and villagers helped them to a nearby health clinic.[174]Where firearms are used, international law calls upon law enforcement officials, to, among other things, "ensure that assistance and medical aid are rendered to any injured or affected persons at the earliest possible moment."[175]

Major Kulayigye, the Ministry of Defence/UPDF spokesperson, told Human Rights Watch that four civilian men were killed in the operation in Lokolia parish on December 7, which he described as a joint UPDF and police operation, when they tried to come to the assistance of suspects apprehended on suspicion of criminal activity. Major Kulayigye denied that any of the victims were women or children.[176] Members of the community told Human Rights Watch that the soldiers justified the shootings as necessary because, the soldiers claimed, a young man had opened the manyatta gate, permitting people to run away.[177]

Nakot ward, Lobongia parish, Kaabong district, December 10, 2006

In a cordon and search operation in Nakot ward, Lobongia parish, Kaabong subcounty on December 10, 2006, one man was shot and killed by UPDF soldiers who returned his fire and a second, P.E., was shot and injured as he attempted to flee.

P.E. was inside his manyatta when soldiers approached for a cordon and search operation. "I don't know the time. I just realized that the military was outside. The military said open. We opened the gate and we came outside," he said.[178]

P.E. told Human Rights Watch that a local defense unit (LDU) soldier opened fire on the soldiers;[179] separately, Human Rights Watch was informed that this LDU soldier had deserted.[180]P.E. saw the soldiers fire back at the LDU deserter, killing him, and P.E. started running: "I thought the soldiers would kill me. I didn't have a gun. I just started running." P.E. was shot three times by the soldiers, who were "showering the bullets," and collapsed in the field outside the manyatta. P.E. regained consciousness only after the soldiers had already completed their cordon and search operation and left the area.[181]An elderly man, R.P., who stayed inside the manyattaand (as discussed below) was severely beaten by soldiers as they searched the manyatta, recalled hearing many gunshots outside.[182]

While the soldiers do not appear to have acted improperly by returning fire at the LDU deserter who shot at them, the incident raises concerns that the soldiers used unnecessary force against the other villagers.[183]

Irosa village, Losogolo parish, Kaabong district, January 1, 2007

During a cordon and search operation on Irosa village in Losogolo parish, Kaabong subcounty on January 1, 2007, a teenage boy, F.E., and his father were shot by soldiers as they fled. According to villagers interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the soldiers came in the night:

We heard military vehicles and then we were running and soldiers started firing. Nobody helped us.

All men were taken outside. They first collected us all outside and then took eight in the vehicle to the barracks . They beat us while they were collecting us from here, but they didn't beat us after they took us to the barracks.[184]

One man, detained after the operation for five days in Kaabong barracks, attempted to hide outside in the bush:

I ran out and hid in the bushes. The soldier found me there and I was beaten on my back with the butt of the gun. The soldier said, "You stop." He beat me twice on my back and kicked me and I fell down. The soldier was saying, "Get the gun! Get the gun!"[185]

F.E. was shot, sustaining a fracture to his right femur and a ruptured bladder:

[A] woman told me soldiers were coming so I started running . I never saw the soldiers. I just saw the fire [from the soldier's gun] . As I fell, I saw the soldier move away. I landed near him and he left me lying there.[186]

F.E.'s father was carrying his gun as he ran, and was killed. Residents of the village told Human Rights Watch,

Karamojong are cowards. When they see the government they start running. This elder [F.E.'s father] had a gun . He was just holding his gun. He was running with his gun. We didn't know he was killed until we saw the soldier had taken the gun.[187]

According to other members of the village, when they realized F.E. had been shot, his mother started crying and convinced a soldier to take the boy to the hospital in Kaabong town.[188]F.E. remained hospitalized at least five months after the incident.[189]

Loparpar village, Nakwamuru parish, Moroto district, January 6, 2007

According to R.D., an eyewitness interviewed by Human Rights Watch, during a cordon and search operation on January 6, 2007, on Loparpar village, Nakwamuru parish, Lopei subcounty, Moroto district, UPDF soldiers fired rocket-propelled grenades at unarmed civilians. During the operation, R.D. saw in the distance a herd of cattle and women with firewood. The soldiers began shooting and launching grenades at these people, and asked R.D., "Who are those people? Are they coming to attack us?" R.D. told Human Rights Watch that he told the soldiers that they were just women collecting firewood.[190] No casualties during this incident were reported to Human Rights Watch.

Lotome subcounty, Moroto district, January 2007

On January 19, 2007, members of the Bokora community in Lotome subcounty, Moroto district, clashed with UPDF soldiers as the latter entered Nachuka village while tracking raiders who had killed nine women collecting grass in Nabilatuk subcounty, Nakapiririt district, a few days earlier. According to T.O., a resident of this village, the men began to run away with their guns when women in the village raised the alarm about the soldiers' presence, the soldiers fired on the men, and the men returned their fire. People from nearby villages joined in the fighting, which lasted about four hours.[191] T.O. claims that four soldiers and no civilians were killed in the clash; T.O. was not himself a participant or witness to the violence.[192]

The following day, UPDF soldiers in an armored personnel carrier (APC) and another military vehicle known as a "mamba" reportedly arrived at six nearby villages, including Nakaromwae and Lobei villages.

Human Rights Watch was told by P.L., a resident of Nakaromwae village, that people from Nakaromwae began to run away, but were followed by the military vehicles. Two men were crushed to death by the military vehicles; according to P.L., when the villagers returned after the army left, they found their skeletons already picked clean by vultures.[193] (Human Rights Watch researchers were shown photographs of the skeletons.) A third man was stripped naked and severely beaten by the soldiers. P.L. told Human Rights Watch,

I did not witness the beating. But I came back that same day and we found him lying naked in the mud. I picked him [up] and helped him to the [hospital]. The whole body had swelling-they had really beat him.[194]

One or more vehicles were reportedly driven through a manyatta, crushing one home.[195] Human Rights Watch researchers visited and photographed the village in early February; damage to fences and other structures was still evident.

In Lobei village, Human Rights Watch was told by a resident, V.E., that people also began to run away as the military vehicles approached. Returning the following morning, villagers, including V.E., found an elderly man-a visitor from Moroto-crushed in the tire tracks of one of the vehicles.[196] According to V.E., soldiers had also looted the manyatta and taken away some of the elders to the UPDF's temporary campsite at a nearby school.[197]

A fourth man from another village, Angaro, was also reportedly crushed to death by the army vehicles.[198]

According to R.A., an elder from Nachuka village detained at the nearby school, the elders from Lobei village were among 19 persons detained by the soldiers, some for more than a week. R.A., interviewed by Human Rights Watch and detained for two days, was tied in a "three-piece," that is, his arms were bent at the elbows, and then his elbows were tied together behind his back, stretching out his chest: "It was so painful we thought we were going to die."[199] Soldiers told the detainees to get the guns that were used in the confrontation. R.A. was also kicked and beaten, and forced to stare into the sun. The treatment improved within a day of his detention after a high-ranking officer arrived and the local council chair of Moroto district (LCV chair) also intervened.[200]

According to the UPDF, four soldiers were killed and five injured, and their weapons stolen, in an operation on January 22, 2007, to arrest the men responsible for killing the nine women in Nakapiripirit district. Four civilians were killed and eight were captured in subsequent related operations by the UPDF.[201] As noted above (Chapter III.B), at least two were subsequently convicted by court martial for the deaths of the nine women and were sentenced to nine and ten years' imprisonment.[202]

Kotido subcounty, Kotido district, February 2007-Possible further episode of unlawful killings

According to an investigation by OHCHR, UPDF cordon and search operations on a kraal at Kapus dam behind the Lokitelaebu trading center in Kotido subcounty, Kotido district, on February 12-13, 2007, "caus[ed] confusion and casualties amongst the population," with 34 civilians (one girl, 15 boys, and 18 men) killed in all.[203] According to a list of 48 victims provided to OHCHR by a local community based organization-on which OHCHR relied in confirming the deaths of 34 of those listed-most victims died as a result of cattle stampede or were killed in crossfire between the army and the armed group.[204] OHCHR investigators photographed two items of unexploded ordnance within two kilometers of the kraal.[205]

OHCHR reported that these operations were "precipitated by an attack on patrolling soldiers near the watering point, following a series of ambushes by armed Karimojong elements on 12 February 2007" and that "[a]fter two day[s] of operations, the UPDF stated that some 80 individuals had been injured or had died as a result of their offensive. The operations reportedly targeted kraals close to the location where the patrolling soldiers had been attacked."[206] Three road ambushes along the Kotido-Abim road on February 13 were reported in the national media.[207]

Human Rights Watch interviewed UPDF spokespersons at the time of UPDF operations in the area. According to these spokespersons, their soldiers were on patrol on February 12 in Kotido district when they encountered herdsmen with a large number of cattle in an unpopulated area and were fired upon;[208] a subsequent statement by the Ministry of Defence identified the area as Kailong,[209] which is also in Kotido subcounty. The soldiers returned fire.Four soldiers and seven civilians were killed in the encounter before the herdsmen were dispersed, abandoning the cattle.[210] According to the Third Division spokesperson, on the following day, February 13, the group several times fired upon the soldiers who had set up a defense around the cattle, and 45 armed civilians were killed by the army. The group moved deeper into the bush, pursued by the army.[211] The UPDF Third Division spokesperson confirmed to Human Rights Watch that the UPDF used helicopter gunships, as well as rocket-propelled grenades and mortars in these clashes. According to the spokesperson, however, these were only used in an attempt to scare off the armed herdsmen and to prevent their escape to Kenya.[212]

The Ministry of Defence/UPDF spokesperson told Human Rights Watch that UPDF operations on February 12-15 were not preceded by a cordon and search operation.[213] However, in comments published the same day as he spoke to us, the Kotido police commander explained in the New Vision that the violence was triggered by UPDF disarmament operations at Kailong dam on February 12,[214] and, as stated above, a subsequent investigation by OHCHR found that UPDF cordon and search operations on a kraalin the Kapus dam area on February 12-13 were precipitated by a Karamojong attack on UPDF soldiers and ambushes. In light of these differing accounts, chronologies, and place names, the relationship between the operations acknowledged by the UPDF and the cordon and search operations reported by the Kotido police commander and documented by OHCHR is not clear.

B. Torture and Ill-treatment

Torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment are prohibited without qualification by international law and the Ugandan constitution.[215] The Convention against Torture, to which Uganda is a party, defines torture as intentional acts by public officials that cause severe physical or mental pain or suffering for the purpose of obtaining information or a confession, or for punishment, intimidation, or discrimination.[216] Cruel and inhuman treatment includes severe suffering that lacks one of the elements of torture or that does not reach the intensity of torture.[217]Degrading treatment includes treatment that involves the humiliation of the victim or that is disproportionate to the circumstances of the case.[218]

The beatings and other physical abuse described below, occurring during cordon and search operations and during post-cordon and search detention, amount to cruel and inhuman treatment, and even to torture, where severe and accompanied by soldiers' demands to "get the gun." Particularly harsh conditions of detention, including deprivation of food and water, have also been determined to constitute inhuman treatment under international law.[219]This abuse also violates the guarantees of humane treatment and "respect for the inherent dignity of the human person" extended by international law to all detained persons.[220]

During cordon and search operations

In all nine cordon and search operations investigated by Human Rights Watch, victims and witnesses reported that men were beaten by soldiers.

These beatings were isolated occurrences in the four cordon and search operations in Kaabong district about which Human Rights Watch obtained victim and eyewitness testimony. For example, in the cordon and search operation in December 2006 on Nakot ward in Lobongia parish, two soldiers beat an elderly man, R.P., as he sat in front of his house inside the manyatta. R.P. told Human Rights Watch that he had stayed behind when other villagers responded to the soldiers' demands that they "come out" and "bring the gun":

When I remained, the soldiers came inside the village. There was one soldier who pointed his gun at me and wanted to shoot me, but the commander stopped him. Another group [of soldiers] came and said, "Why are you here?" I said, "I am lame." These two soldiers started beating me. The soldiers knocked me with the barrel of the gun on the head. Then they got out a bayonet and started stabbing me. They stabbed me three times with the bayonet on the head. I was also beaten with a stick on the leg. Just young men were beating me. The [commander] had already said that I didn't have a gun. I was even kicked in the mouth. I started bleeding. I'm still having pus from my nose.[221]

R.P. spent seven days in the hospital.[222]

In Moroto district, victims from five communities described mass beatings of the male population. In cordon and search operations in three communities-Lorikitae parish, Lokopo subcounty (January 17, 2007), Loputuk parish, Nadunget subcounty (January 26, 2007), and Longalom village, Lokopo subcounty (September 2006), the pattern described was almost identical:soldiers first rounded up the men outside of their manyattas and then subjected them to collective beatings, often accompanied by soldiers' oral commands to "get the gun." According to the victims, soldiers used sticks, whips, guns, and tree branches to carry out the beatings.

Longalom village, Lokopo subcounty, Moroto district, September 2006