Summary

“Should we carry weapons and work with the militants, or work with the army, or [accept to] live like victims?”

—Sinai resident flogged by ISIS-affiliate militants and later punished by the army, Rafah City, late 2015.

Since 2011, the Egyptian military and police have battled ISIS-affiliated militants in North Sinai governorate. Sparsely populated, and with roughly half-a-million residents, this northern part of the Sinai Peninsula that borders Israel and the Gaza Strip has been a historically marginalized territory, separated from the rest of the country by the Suez Canal. Thousands have been arrested, and hundreds have been disappeared in the past six years since the conflict escalated in 2013. Tens of thousands of residents have been forcibly evicted or fled their homes due to ongoing violence.

This report documents how the Egyptian military and police have carried out systematic and widespread arbitrary arrests—including of children—enforced disappearances, torture, and extrajudicial killings, collective punishment, and forced evictions—abuses it has attempted to conceal through an effective ban on independent reporting. The military has also possibly conducted unlawful air and ground attacks that have killed numerous civilians—including children—and used civilian properties for military purposes. In addition, it has recruited, armed, and directed local militias, which have themselves engaged in serious rights violations, such as torture and arbitrary arrests, often exploiting their position to settle personal scores.

Human Rights Watch has previously documented other abuses in Sinai that are not covered in this report, including unlawful mass destruction of homes and the Egyptian army’s forcible evictions of tens of thousands of residents, with little or no help for temporary accommodation and no judicial recourse.

For their part, hundreds of fighters with the ISIS-affiliate group Wilayat Sina’, or Sinai Province, have kidnapped, tortured, and murdered hundreds of Sinai residents. They have beheaded or shot those who disagree with their extreme religious views or whom they perceive to be government sympathizers, and they have executed scores of captured government security forces, a war crime.

Based on the research done for this report, and previous research Human Rights Watch has published on the situation in Sinai, the report finds that the fight in North Sinai most likely amounts to a non-international armed conflict (NIAC) in which the laws of war apply. The conditions to qualify a situation as a NIAC include severity, intensity, and duration of hostilities, as well as identifiable chains of command for warring parties. Some of the abuses carried out by government forces and the militants, which this report documents, are war crimes, and their widespread and systematic nature could amount to crimes against humanity. Both war crimes and crimes against humanity are not subject to any statute of limitation, and the latter could be prosecuted before international tribunals.

The conflict in North Sinai escalated dramatically after July 2013, when then-Defense Minister Abdel Fattah al-Sisi ousted President Mohamed Morsy, a top Muslim Brotherhood official who had taken office the year before. Since Morsy’s removal, which prompted nationwide unrest and a brutal response from the army and police, the government has mobilized tens of thousands of soldiers in the area and used heavy weapons, naval vessels, and military aircraft. It has also imposed a state of emergency and a curfew in most of North Sinai, which quickly became the site of frequent attacks on the military and police.

The Egyptian military presence in Sinai has not been this large seen since the country’s 1979 peace treaty with Israel, which strictly limited armed forces in the Sinai Peninsula. However, since 2013, Israel has not only allowed a build-up of Egyptian military presence in the area beyond the treaty stipulations, but also according to media reports and official statements, aided the Egyptian government forces and probably participated in airstrikes against ISIS-affiliated militants.

As the conflict has ground on, the toll on local residents has grown. Independent media estimates indicate that at least hundreds of civilians have been killed and injured by all sides since July 2013. Formerly inhabited parts of North Sinai have turned into ghost towns, abandoned by residents fearful of more violence or being forcibly evicted by the army.

Governments have an obligation to protect inhabitants of their territories from harm and protect their right to life. They and all parties to a conflict are also obliged to comply with international law. As the United Nations has repeatedly warned and Human Rights Watch has repeatedly documented, not only are abusive counterterrorism measures unlawful, they are also often counterproductive, alienating the very local communities they are allegedly protecting and generating support for extremist and armed groups.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Egyptian authorities to protect civilians and uphold its obligations under the international laws of war and local and international human rights laws. The United Nations Human Rights Council and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights should also open a commission of inquiry into abuses by all parties to the conflict in the North Sinai, including the Egyptian authorities, their armed forces and their irregular militias, and Sinai Province group. In addition, UN member states should suspend assistance to the Egyptian military and the police, as long as they carry out widespread and serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law and fail to hold those responsible for violations accountable. Governments currently transferring weapons to Egypt, including the United States, United Kingdom, and France, have a responsibility to monitor how the arms they export are being used. When they continue to supply arms and other assistance knowing this support is significantly contributing to serious abuses, they may risk being complicit in these violations as well.

Government Abuses

Mass Arrests and Enforced Disappearances

Since the escalation of the military campaigns in North Sinai in the summer of 2013, security forces have arrested thousands of residents, many of whom were probably arbitrarily arrested. Regular arbitrary arrest campaigns are part of daily life in areas where militants have been most active, residents said, including the cities of Rafah, Sheikh Zuwayed, al-Arish, and their surrounding villages in the northeast.

According to locals who spoke to Human Rights Watch, the police and military treated residents of these areas with automatic suspicion. They said that soldiers, sometimes accompanied by Interior Ministry police forces and army-sponsored militia members, traveling in convoys of armored vehicles, regularly cordoned off neighborhoods and moved from house to house, asking for men by name or arresting whoever happened to be present.

In no case that Human Rights Watch documented did authorities present a warrant or tell residents why they were making arrests, witnesses said. Typically, arresting officers said they would take someone for routine questioning and return them shortly. In reality, most people who have been arrested have been detained for long periods, sometimes years.

Human Rights Watch documented 50 cases of local residents arbitrarily arrested by government security forces. In 39 of these cases, authorities likely forcibly disappeared them. Of those forcibly disappeared, 14 have been missing for at least three years. In none of these cases did prosecutors investigate the disappearance or subsequent alleged torture of detainees. In one case, a young man, whom the army forcibly disappeared for months before moving him to an official prison outside the Sinai, told the prosecutor interrogating him about his months-long disappearance and ill-treatment. He said the prosecutor responded: “Consider it the price you pay for the sake of the homeland.”

Extrajudicial Killings and Killings at Checkpoints

Human Rights Watch documented 14 cases of extrajudicial killing of detainees in North Sinai, in addition to at least six cases that Human Rights Watch published prior to this report. In one case, the military arrested two brothers from their home in al-Arish, the capital of the governorate, in February 2015, and took them to Battalion 101, the largest military base in North Sinai. Two days later, one of the detained men’s relatives said he received word that bodies had been discovered by the road near the entrance to al-Raysan, a remote village south of al-Arish. When the relative arrived there, he said he found vehicle tracks and the bodies of the two men, one with bullet wounds to the back and face, and the other to the head. The next day, detainees who had just been released from Battalion 101 came to offer their condolences and told the relative that soldiers had taken the two brothers out of their cell on the morning of their death and loaded them into a convoy of Humvees.

All the main roads in North Sinai are tightly controlled by dozens of army checkpoints and military installations. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that soldiers at the checkpoints sometimes shot at approaching individuals and civilian vehicles that posed no apparent security threat. Human Rights Watch documented three of these likely unlawful killings. Witnesses also described how the curfew imposed in North Sinai since October 2014 did not allow emergency medical aid to be provided. Even outside curfew hours, ambulances took a long time to arrive at their intended destination because of delays at army and police checkpoints.

Ill-Treatment, Torture, and Death in Detention

The military detained most of those arrested in North Sinai at three sites: Battalion 101, located in al-Arish; Camp al-Zohor, a converted youth and sports center in Sheikh Zuwayed; and al-Azoly, a military prison inside Al-Galaa Military Base, the headquarters of the Second Field Army in the Suez Canal city of Ismailia. Residents arrested by the police are typically transferred to the North Sinai governorate headquarters of the Interior Ministry’s National Security Agency, also in al-Arish.

Far removed from any judicial oversight, detainees at these sites lack basic rights and sometimes are subject to abuse. In this report, Human Rights Watch documented 10 cases in which detainees or their relatives said they had been physically abused, including by beatings and electric shocks, almost always by soldiers in uniform. They described how this abuse, which in many cases appeared to amount to torture, occurred while they were forcibly disappeared—i.e., when their detention was kept secret from relatives or lawyers—and kept in overcrowded cells without adequate food, clothing, clean water, or healthcare.

Former detainees described seeing children as young as 12 detained in these conditions with adults. Very few of the former detainees, whose time in custody ranged from weeks to months, were ever charged or appeared before prosecutors, as Egyptian law requires. Those who did only saw prosecutors after authorities transferred them to official detention facilities outside the Sinai or to military courts inside Al-Galaa Military Base for trial. Due to fear of being re-arrested and tortured—and possibly being extrajudicially killed—no former detainees have filed a complaint with the authorities about their treatment.

Former detainees said they witnessed the death of three other detainees in custody because of ill-treatment and lack of medical care.

Interviewees said that some military officers working in North Sinai torture detainees until they supply interrogators with the identities of so-called “terrorists” or “takfiris,” the Arabic word for extremists who believe in excommunicating fellow Muslims and which the Egyptian authorities use broadly to describe all militants.

One man detained in Camp al-Zohor recalled the words of an interrogator who seemed to admit that the military’s brutal tactics yielded deadly mistakes. “It’s true that in army [detention] some people are taken wrongly, and others die,” the interrogator said. “But we also fight takfiris, and arrest [many] of them.”

Role of Pro-Government Militias

This report also documents the role of pro-government militias in North Sinai. Not long after the conflict began, the army, which had not operated in North Sinai for decades and lacked local intelligence, began recruiting local residents into an irregular militia, unregulated by official decrees or laws, which has since played a substantial role in abuses.

Called manadeeb (delegates) by the authorities and gawasees (spies) or “Battalion 103”—a play on the name of the Battalion 101 military base—by North Sinai residents, these militias perform a function that blends intelligence gathering with police action. Despite their irregular status, they have de-facto arrest powers and operate under the direction and command of the military, which gives them uniforms, weapons, money, and often a place to live on military bases. Militia members are decisive figures in army arrest campaigns, which they often exploit to settle personal disputes or to further business interests, residents said.

“They turn people in and that’s it,” including “anyone who pesters them or who they’re annoyed with,” a former army officer, who served in North Sinai, told Human Rights Watch.

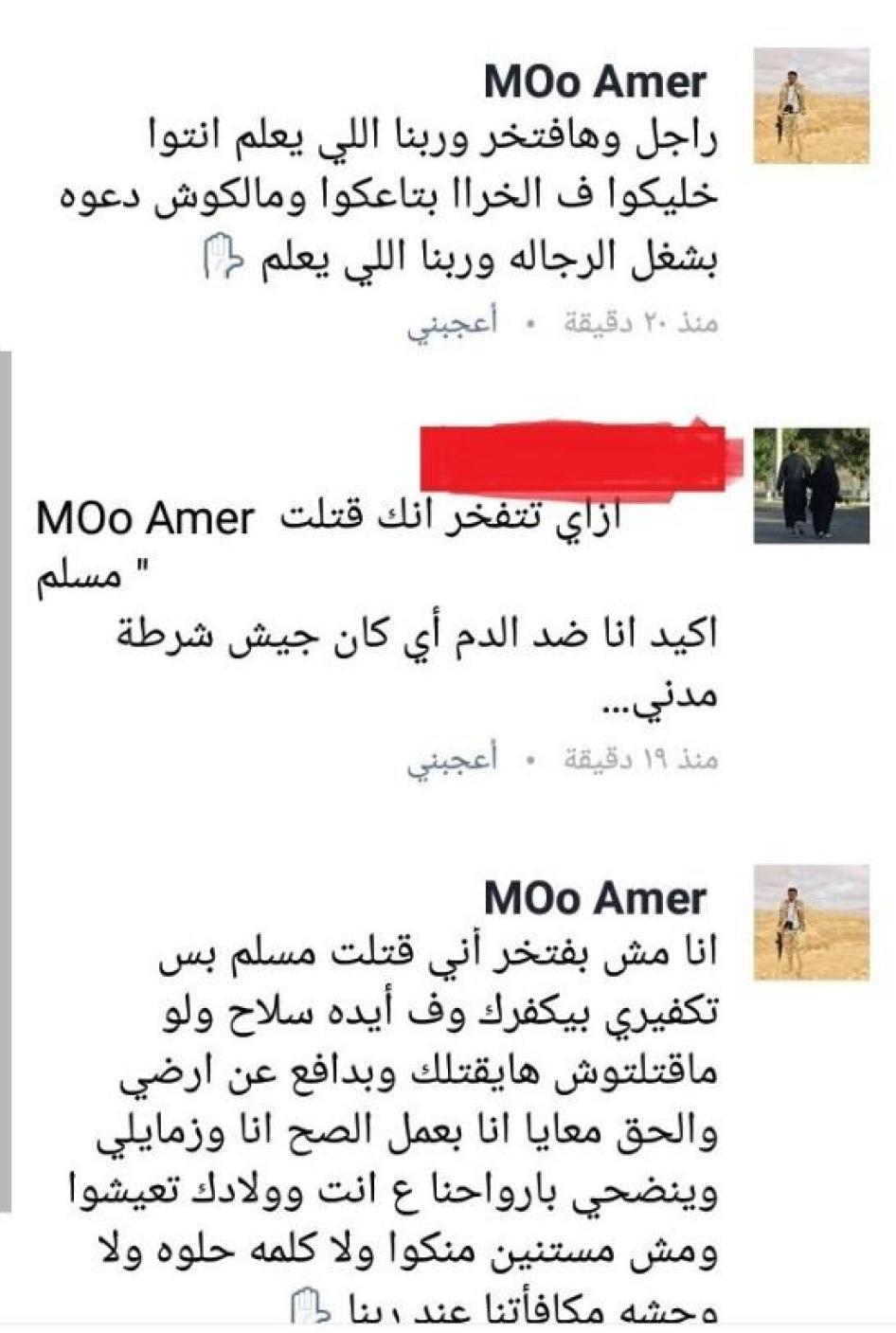

The militias function almost completely outside the law. Sometimes, militia members themselves have apparently carried out the worst abuses. In April 2017, a Turkey-based satellite channel opposed to the Egyptian government aired a leaked video, apparently filmed by a soldier, of a militia member interrogating and then executing two young male detainees in an empty field. Human Rights Watch determined through several Sinai residents that the video was authentic. A military intelligence officer could be seen on the video supervising the executions while other soldiers watched.

The exact size and composition of the militias are unknown, but many of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch said it was common to see militia members—easily recognized by their ragtag informal uniforms of army-issued camouflage clothes, sometimes paired with flip-flops, and their face-covering scarves and local accents—accompanying army convoys and identifying individuals for arrest. Residents told Human Rights Watch that the army paid militia members well and appeared to recruit men who had criminal backgrounds.

“Most of the group members are known and have sawabiq (criminal records) or were baltageya (thugs),” a resident told Human Rights Watch. “And most of them are looked down on because of [drug] addiction, [or] because their tribes renounced them due to their past criminal behavior. So, they couldn’t find a safer refuge than the military cover they’re working through.”

North Sinai residents spoke of altercations with militia members that led to arrests. One woman from Rafah whose father the army forcibly disappeared in 2014 said a militia member came to her home shortly after her father put up an electricity pole in front of the house. She said:

The militia member said, ‘You can’t put that here,’ and they had an argument in the street … My father told him, ‘I’ll complain about you to the army,’ and [he] started laughing loudly and said to my father, ‘If you open your mouth, I’ll take you to the army from your home.’ And two days after the argument, we found a convoy of Humvees and armored vehicles enter the neighborhood and come to our home.

Likely due to the poor reputation of the militias, residents also said that in a few cases, the army distributed “unofficial” pamphlets in North Sinai towns distancing the armed forces from one or several militia members and saying they would punish them. However, Human Rights Watch found no evidence of abusive militia members being held to account.

Possible Unlawful Air and Ground Attacks

The army has never acknowledged that any civilian casualties have occurred in North Sinai. Without access to the governorate, it is challenging for human rights groups or independent media to assess the humanitarian impact of air and artillery attacks, whether committed by Egypt, Israel, or the militants. But several accounts given to Human Rights Watch suggest that the Egyptian military is not taking feasible precautions to avoid and minimize harm to civilians while conducting its operations.

The report documents several incidents in which residents said that, to their knowledge, there were no military targets or clashes around their homes when the army used various air or ground-delivered weapons which caused possible civilian casualties and damaged or destroyed civilian homes and infrastructure.

One woman described how an army convoy transporting ammunition to a checkpoint entered her neighborhood in Sheikh Zuwayed in October 2015 and began to exchange fire with militants about 500 meters from her house. As she took cover, holding her two teenage daughters, a projectile struck her house and exploded. She said:

It’s a hard feeling, getting shot at while your daughters are in your lap. You don’t know your fate or theirs or what to do, and they’re screaming, and you can’t protect them from the shooting…. The blood is the last thing I remember, and the sound of screaming, me and my daughters.

The woman was knocked unconscious and woke up in the hospital, where she later learned that her daughters had died by the time rescuers pulled their bodies from the rubble of her house. She blamed the Egyptian army for the attack, saying the militants were not using weapons capable of firing projectiles powerful enough to have done such damage to her house.

ISIS-Affiliate Sinai Province Group Abuses

The local ISIS affiliate in North Sinai, Wilayat Sina’ (Sinai Province), has taken root in the northeast and committed horrific crimes, said interviewees, including kidnapping scores of residents and security force members and extrajudicially executing some.

Sinai Province’s indiscriminate attacks, such as using improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in populated areas, have killed hundreds of civilians and led to forced displacement of local residents. The group has also deliberately attacked civilians, including claiming responsibility for the October 2015 bombing of Metrojet Flight 9268, which exploded after taking off from the Sinai resort town of Sharm al-Sheikh, killing all 224 passengers and crew Sinai Province fighters were probably also responsible for a November 2017 attack on worshippers at al-Rawda Mosque in North Sinai that killed at least 311 people, including children, probably the deadliest violent attack by an armed group in Egypt’s history.

In areas in Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed, the group established its own Sharia (Islamic law) courts that oversaw unfair “trials” and set up its own checkpoints that conducted regular policing and Hisba (enforcement of certain Islamic rules). This included instructing women not to leave their houses alone and to cover their bodies and faces when they went out. Attacks on Christian residents in al-Arish that resembled ISIS attacks elsewhere in the Middle East have forced all Christian families to leave their homes and flee Sinai.

Recommendations

To the Egyptian Government and the Egyptian Army

- Allow independent humanitarian and relief groups to conduct operations in Sinai, including the Egyptian Red Crescent and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

- Lift unlawful restrictions on movement of Sinai residents and commercial activities and ensure that remedies are offered to residents affected by necessary restrictions.

- Order immediate investigations and prosecutions, in compliance with international fair trial standards, of members of the government security forces and the pro-government militias involved in abuses.

- Release all detainees who are held without evidence of wrongdoing and promptly bring those charged before civilian courts and guarantee fair trials and due process in all cases.

- Move all detainees immediately to official prisons. Shut down all unofficial detention centers, particularly al-Azoly prison, and bring all detention sites under judicial supervision and all detention conditions in compliance with the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners.

- Establish a transparent, independent redress mechanism for detainees who committed no wrongdoing and for families who have been forcibly evicted, whose property was damaged or destroyed during conflict, or whose relative was injured or killed unlawfully.

- Establish a committee, which includes effective representation of Sinai communities, to study and supervise remedies for the return of families displaced from conflict areas as soon as possible.

- Release children in detention. Do not prosecute children unless as a last resort and in accordance with international juvenile justice standards.

- Invite and accept requests for visits by UN Special Procedure mechanisms to the Sinai, provide them with unhindered access, and ensure that no reprisals are committed against individuals who cooperate with them.

- Transparently investigate incidents in which strikes conducted by the Egyptian military have led to civilian casualties. Communicate the results of such investigations to civilian victims and their relatives and offer monetary compensations and non-monetary acknowledgements of the harm done, such as apologies, regardless of lawfulness of the attack that caused the harm.

- Ensure, through military academy curricula and further courses, that military officers and soldiers are educated on the principles of international humanitarian law and comply with these obligations as part of their professional duties.

To the Egyptian Parliament

- Amend Law 25 of 1966 for the Military Code of Justice to clearly establish the rights of detainees in military detention and the treatment of civilians at times of armed conflicts according to international standards.

- Amend the Emergency Law to bring judicial supervision over all security measures and remove the unchecked, non-constitutional powers given to security forces.

- Thoroughly revise or revoke Law 94 of 2015 for Countering Terrorism to remove officers’ impunity and narrow the definition of terrorism and otherwise comply with international norms.

- Call for public hearing sessions at the parliament for North Sinai residents and activists to explain their grievances and present their demands.

To the Ministry of Justice and Egypt’s Prosecutor General Office

- The Ministry of Justice should launch an independent investigation into the failure of prosecutors in Sinai to investigate abuses by security forces and militant groups. Prosecutors found negligent should be disciplined as appropriate by their own professional body.

- The Ministry of Justice should immediately commission an independent investigation, comprising Sinai activists, human rights defenders, civil society representatives, and law professors, to proactively seek, receive, and transparently review evidence of abuses by security forces and militant groups in Sinai. The victims of abuses and their relatives should be allowed access to information and be involved in the investigation.

- Order prosecutors to immediately visit secret sites of detention reported by witnesses in the Sinai and order them shut down or their conversion to official prisons if appropriate.

To the National Council of Human Rights

- Establish a permanent office in North Sinai to receive complaints and investigate them promptly and to monitor discrimination against North Sinai people. Publish the findings of the council’s work on Sinai regularly.

To the Israeli Government

- Publicly announce the nature of the involvement of Israeli forces in the North Sinai conflict.

- Transparently investigate incidents in which strikes conducted by the Israeli military have led to civilian casualties. Communicate the results of such investigations to civilian victims and their relatives and offer monetary compensations and non-monetary acknowledgements of the harm done, such as apologies, regardless of lawfulness of the attack that caused the harm.

To All Parties to the Conflict, including the Self-Declared Sinai Province Militants

- Take all feasible measures to protect civilians, in accordance with international humanitarian law, during any military ground and air campaigns.

- In areas where a non-state party to the conflict serves as the de-facto governing force, take all feasible measures to protect without discrimination the rights of all inhabitants and ensure all civilians’ basic needs are met.

To the United States Administration

- Halt all military and security assistance to Egypt and condition its resumption on concrete improvement of human rights, including an independent investigation into and prosecutions of perpetrators of serious violations, including war crimes, in North Sinai.

- Investigate and release a public report on use of US weapons and/or equipment in the serious abuses in Sinai, including those documented in this report as well as by other credible organizations and independent media outlets.

- Conduct an official review of goals, objectives, and effectiveness of joint military exercises, including Egypt’s participation in all multilateral military exercises to prepare Egypt’s military to combat the threat from the ISIS-affiliate Sinai Province, and ensure that civilian casualty minimization is incorporated into all efforts.

- Ensure the US Embassy country team in Egypt conducts a thorough and comprehensive human rights vet for all Egyptian military units that receive US security assistance or training and operate in the Sinai Peninsula. Ensure that all offices and personnel tasked with ensuring compliance under the Leahy Law at the Departments of State, Defense, and US Central Command have a clear understanding of their mandate and adequate funding.

- Impose visa bans and asset freezes pursuant to the Global Magnitsky Accountability Act of 2016 and Executive Order 13818 on all Egyptian security officials found to be complicit in gross human rights violations in the Sinai.

- Urge Egyptian authorities to open Sinai and allow consistent access to independent journalists and observers as well as to US officials, including congressional delegations.

To the US Congress

- If the US executive branch fails to halt all military and security assistance to Egypt, Congress should legislate accordingly to remove the option of a national security waiver that enables the administration to circumvent congressional human rights conditions on US assistance.

- Request an updated Government Accountability Office report looking at end-use monitoring of US weapons and equipment in Egypt; ensure all future assistance to the Egyptian government is conditioned on the implementation of proper and effective end-using monitoring mechanisms.

- Ensure that all offices tasked with ensuring compliance under the Leahy Law at the Departments of State and Defense have adequate funding and staff.

- Conduct oversight hearings in relevant congressional committees, such as foreign relations and appropriations committees, to gain a better understanding of US support for Egypt’s military operations in Sinai, including allegations of serious violations, including war crimes, documented in this report.

- Urge Egyptian authorities to immediately open Sinai and allow consistent access to independent journalists and observers as well as to US officials, including congressional delegations.

To All Egypt’s International Partners

- Halt all military and security assistance to Egypt and condition its resumption on evidence of an end to serious violations, including war crimes in North Sinai, and credible steps to investigate and prosecute such crimes.

- European Union member states in particular should uphold the August 21, 2013 Foreign Affairs Council decision of halting arms transfers to Egypt and revising all such licenses.

- Ensure proper and effective end-using monitoring mechanisms of any future assistance offered to the Egyptian government.

- Pressure Egyptian authorities to immediately open Sinai to independent journalists and observers and humanitarian aid groups.

- Under the principle of universal jurisdiction and in accordance with national laws, investigate and, where appropriate, prosecute individuals implicated in serious crimes under international law.

To the UN Human Rights Council, Special Rapporteurs, Security Council Bodies, and Office of Counter-Terrorism

- The UN Human Rights Council should establish an international investigation into violations and abuses committed by all parties to the conflict in North Sinai, including senior Egyptian officials and government security forces, pro-government militias, and Sinai Province militants. The investigation should also include the Office of the Prosecutor General for its failure to hold perpetrators accountable.

- Special Procedures mechanisms should request to conduct visits to Egypt, including North Sinai, particularly the Special Rapporteurs on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism; extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions; torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; the right to development; and the UN Working Groups on enforced or involuntary disappearances and on arbitrary detention.

- The Security Council Counterterrorism Committee, the Counterterrorism Committee Executive Directorate, and the Office of Counter-Terrorism should request to visit areas of Egypt, including North Sinai, for meetings with all parties, including civil society members, and briefings by Egyptian officials, and submit reports on their findings to the UN Security Council and Secretary-General António Guterres. Such reporting, including by the Office, should highlight the nationwide use of counterterrorism operations by the government to bypass international and domestic laws aimed at safeguarding human rights. The Office should report details of specific cases of abuse and, where there is sufficient evidence, name individual officials linked to human rights abuses in countering terrorism for further investigation and possible prosecution.

To the African Union and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

- Member states of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights should adopt a resolution condemning abuses by all parties to the conflict in North Sinai. The commission should hold the Government of Egypt to account regarding Egypt’s failure to promote and protect human rights in North Sinai.

- The Peace and Security Council of the African Union should place Egypt on its agenda and periodically review the situation of human rights in the country, particularly in North Sinai.

- The Peace and Security Council should also review all military and security arrangements with Egypt, impose an embargo on all arms exports to the Egyptian army, and halt all security trainings with Egyptian security forces and condition their resumption on evidence of an end to serious violations in North Sinai, including war crimes and taking credible steps to investigate and prosecute such crimes.

- The Working Group on Indigenous Populations/Communities in Africa should request to visit Egypt, including North Sinai, to examine the question of indigenous communities in North Sinai and the decades-long marginalization and recent dispossession and forced evictions.

- The following special mechanisms should request to visit Egypt and produce reports of their findings regarding the situation in North Sinai: the Working Group on Death Penalty and Extra-Judicial, Summary or Arbitrary killings in Africa; the Special Rapporteur on Prisons, Conditions of Detention and Policing; the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information; and the Committee for the Prevention of Torture in Africa. These special mechanisms should work in close collaboration with the UN Special procedures and the UN Human Rights Council.

Methodology

The Egyptian army severely restricts independent organizations, especially media and human rights groups, from traveling to North Sinai governorate. Human Rights Watch is aware of at least three journalists whom the army and its military prosecution have arrested and charged for their work on Sinai. One of them, Ismail Alexandrani, received a ten-year sentence from a military court in May 2018. In the same case, a Sinai resident received a ten-year sentence because he administrated a Facebook page where he published information on Sinai.

From April 2016 to April 2018, Human Rights Watch interviewed 54 North Sinai residents, several Sinai activists, a former Egyptian government official who worked in North Sinai, two former Egyptian army officers and a former soldier who were deployed in Sinai, and a former United States national security official involved in US policymaking on Egypt who also had discussions with Egyptian officials about Sinai. Human Rights Watch also interviewed several journalists who covered Sinai in recent years. Of the 54 interviews conducted with residents, 14 focused on abuses by Sinai Province militants. Human Rights Watch conducted all of the interviews in Arabic, with the exception of the former US official. Researchers informed interviewees of the purpose of the interview, the ways the data they collected would be used, and gave interviewees an assurance of anonymity. This report uses pseudonyms for all interviewees unless otherwise stated. In certain cases, we have withheld other identifying information to protect the privacy and security of interviewees. None of the interviewees received financial or other incentives for speaking with Human Rights Watch. Some of the interviews were conducted remotely through different calling and texting platforms, and others were conducted face-to-face both inside and outside Egypt.

The interviews done for this report covered violations and incidents that occurred mainly between 2015 and 2017 but some incidents documented occurred as early as July 2013 and as late as June 2018.

In several cases, Human Rights Watch researchers were able to review medical and legal documents that victims or their families provided to them in order to cross-check victims’ accounts against official statements, as well as photographs and video footage the Egyptian army or government and pro-government newspapers have published on the situation in Sinai. Human Rights Watch also analyzed a number of videos that appeared on different social media platforms that publish images, videos, and local commentary from Sinai, as well as dozens of news articles, analytical pieces, and social media posts by well-known Sinai activists and officials in English and Arabic. Human Rights Watch also conducted several media reviews of reports published on Sinai by four Egyptian newspapers of civilian casualties resulting from air and ground strikes or gunfire in Sinai.[1]

Human Rights Watch also analyzed over 50 satellite images recorded between January 2013 and May 2018 to assess allegations of indiscriminate bombardment, monitor the construction of military bases, quantify building demolition, verify witness testimony, and validate videos and photographs shared through social media.

Human Rights Watch reviewed official statements, including by President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the army spokesperson, North Sinai governors, and other officials from different government entities. Human Rights Watch also reviewed written and video statements released by the Sinai Province militant group. Human Rights Watch reviewed a government-sponsored report on the government’s counterterrorism operations in Sinai, co-drafted by an Egyptian judge, and released by the State Information Service in July 2018. Human Rights Watch also reviewed brief recommendations on the situation in North Sinai that were included in two annual reports (2015-2016) by the government-sponsored National Council for Human Rights.

Human Rights Watch sent letters to the office of the cabinet, the minister of defense, the official spokesperson of the Defense Ministry, the Foreign Ministry, and the State Information Service on November 27, 2018, as well as to the North Sinai Governor on May 10, 2018, with detailed questions that cover all the patterns of abuses documented but received no response (See Appendices I and II). Human Rights Watch sent the same letters again to the Embassy of Egypt in Washington, DC, on January 10. Human Rights Watch also sent letters to the Israeli government on January 14, 2019 inquiring about the nature of Israeli military involvement in North Sinai, its reported carrying out of airstrikes in the area, and its existing mechanisms to investigate incidents that led to civilian casualties in Egypt (See Appendix III). Any response received after publishing the report will be published on Human Rights Watch’s website.

While working on this report, Human Rights Watch has separately documented and published the findings of at least six cases of extrajudicial killings in North Sinai in two separate news releases.[2] Human Rights Watch has previously documented in two reports in 2015 and again in early 2018 the unlawful demolitions of thousands of homes and farm areas by the army in Sinai.[3] In 2018 Human Rights Watch also documented the difficult humanitarian situation in most of North Sinai resulting from severe army restrictions on the movement of people and the flow of goods.[4]

I. Background

North Sinai Conflict in Numbers

At least 3,076 alleged militants and 1,226 army and police personnel have been killed between January 2014 and June 2018 in North Sinai, according to the Washington-based Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, which compiles casualty numbers from the conflict in North Sinai based on government statements and media reports.[5]

The institute’s data show marked discrepancies in the numbers of security forces casualties that the Egyptian army spokesperson has reported and those reported in Egyptian newspapers. According to the institute’s data, security forces have arrested more than 12,000 people in its ongoing military campaigns in North Sinai from July 2013 to the end of 2018.

The North Sinai conflict has taken a heavy toll on civilians, yet the government has never publicly provided civilian casualty figures. According to official army statements, security forces arrested over 5,300 suspects and fugitives in just the single year that followed the beginning of “Sinai 2018” military campaign.[6] The army has not disclosed how many of those arrested have been sent to trial or released after initial accusations.

The government has not publicly acknowledged a single case of mistaken arrest or wrongful death despite substantial documentation of the military’s arbitrary mass arrests and use of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings in Sinai. In January 2018, President al-Sisi denied any wrongdoing committed by security forces. However, in a rare but undetailed statement, al-Sisi said that the government was compensating families of those who “fell by mistake.”[7] During the research for this report, Human Rights Watch interviewed some families who received government compensations in an opaque process entirely overseen by the army for having been affected by airstrike or ground shelling attacks.

In 2018, the independent news website Mada Masr said it obtained a government study from the Ministry of Social Solidarity showing that 621 civilians were killed and 1,247 injured as a result of gunfire and shelling from an “unknown source” between July 2013 and Mid-2017.[8] Sinai residents and activists who spoke with Human Rights Watch for this report said that “unknown source” was the only description allowed for relatives of killed and injured civilians who reported casualty incidents to local authorities, when the source responsible was actually government forces.[9]

According to a separate media review by Human Rights Watch of news reports on Sinai from January 2015 to June 2018, Egyptian private and government newspapers reported that over 100 residents were killed and over 300 others injured in North Sinai by gunfire from an “unknown source.” The casualties reported included over 80 women and more than 60 children. The review also showed that newspapers reported over 100 residents were killed and over 250 injured due to “shelling by an unknown source.” This included over 70 women and more than 100 children.

Roots of the North Sinai Conflict

Several factors seem to have affected the development of the Islamist insurgency in North Sinai, including Israel’s decades-old occupation of Palestinian territory, regional dynamics such as the United States’ 2003 invasion of Iraq, and North Sinai’s history of neglect and oppression by Egypt’s central government. [10]

The group that presaged North Sinai’s contemporary militants was al-Tawhid wal-Jihad (Monotheism and Holy War). The group recruited most of its members from Sheikh Zuwayed, in North Sinai, and its surrounding villages, where many residents lacked employment and had long ago grown accustomed to being forgotten by the government.[11] The local movement shared its name with the powerful militant group founded by Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi that would later become Al-Qaeda in Iraq.[12]

In 2004, in its first major act of violence, al-Tawhid wal-Jihad bombed resorts in Taba, Ras al-Shetan, and Nuweiba, along the South Sinai coast, long popular with Israeli tourists, killing 34 people.[13] In response, Egyptian Interior Ministry forces swept through Sinai villages, breaking into homes and arbitrarily arresting hundreds of men—by some estimates up to 3,000.[14] In nearly every case, arresting officers produced no warrants, detained suspects without informing their families or lawyers about their whereabouts—sometimes for years—and tortured those they held in custody.[15] This harsh campaign only worsened grievances against the government.

On July 23, 2005, the anniversary of Egypt’s 1952 revolution, three bombs exploded in the Sinai’s main resort town, Sharm al-Sheikh, where then-President Hosni Mubarak’s family owned five villas, killing at least 88 people.[16] Militants killed at least 30 people the next year, on April 24, 2006, on the eve of the anniversary of Israel’s withdrawal from Sinai, when more bombings struck Dahab, another South Sinai resort town.[17]

Authorities responded swiftly and violently. By the end of 2006, they claimed to have killed all of the bombing conspirators, as well as the leaders of al-Tawhid wal-Jihad, and to have arrested many other group members.[18] From the authorities’ point of view, the harsh response seemed to pay off: for several years, there were no more attacks.

Yet serious problems endured. Smuggling across the Gaza Strip, a major source of employment in the underdeveloped Sinai for decades, boomed after the Palestinian political movement Hamas seized control in Gaza in 2007, and Israel and Egypt responded with a near-total blockade.[19] Sinai clans, with extended families living on both sides of the border, smuggled a variety of goods—including food, fuel, construction materials, and weapons—into Gaza at an increasing rate throughout the late 2000s.[20] Many smuggling tunnels began inside homes and gardens on the Egyptian side of Rafah, a town which straddles the border, making their destruction difficult.[21] Many also functioned with the tacit approval of Egyptian authorities, who often sought bribes for allowing them to operate.[22]

By the late 2000s, many observers and government officials in Egypt recognized that the economic and social situation in Sinai needed attention.[23]

A lawmaker from one of Sinai’s clans said that lack of jobs forced people to take up illegal activities, such as smuggling.[24] Even a local member of Mubarak’s own National Democratic Party said that Egypt’s central government would never be able to properly develop North Sinai as long as authorities treated it as a “security zone,” appointed former military and Interior Ministry generals to run its affairs, and denied its residents various rights and opportunities afforded to mainland Egyptians, such as the same level of education or guaranteed land ownership free from arbitrary military intervention.[25]

A New Kind of Militancy

In late January 2011, protests erupted throughout Egypt, leading within a month to the resignation of President Mubarak. At least 846 people died in 18 days of revolt from January 25 to February 11, 2011. While there were casualties throughout Egypt, violence was acute in North Sinai, where well-armed groups attacked Interior Ministry facilities with automatic, high-caliber firearms and rocket-propelled grenades.[26]

By the night of January 28, several prisons in Egypt had been opened, some following violent attacks and others apparently on purpose.[27] After the unrest subsided, the new government began officially releasing prisoners. Between January and October 2011, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), which governed the country after Mubarak’s resignation, pardoned 858 prisoners.[28] Many were Islamist political figures, including some accused of violence, such as members of Egyptian Islamic Jihad and al-Jama`a al-Islamiyya (The Islamic Group).[29] More than 50 of those released were from Sinai.[30]

In North Sinai, the collapse of the police state and the military’s inability to deploy in large numbers due to the 1979 peace agreement with Israel meant months of weak law enforcement. The Libyan uprising in February 2011 gave birth to a new smuggling route across Egypt’s vast and porous western border. North Sinai was flooded with weapons.[31]

The almost simultaneous arrival in North Sinai of plentiful heavy weapons and long-jailed men with radical ideologies marked the beginning of a new era of militancy. The first indication came in al-Arish in July 2011, with the brazen daytime attack on the police station launched by a convoy of militants flying black flags.

On July 24, 2012, a new armed group declared its existence: Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (Partisans of the Holy House, a reference to Jerusalem).

Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis

A little more than a week later, on August 5, 2012, armed men stormed an Egyptian army checkpoint in Rafah as troops inside were preparing to break their daily Ramadan fast. They killed 16 soldiers before stealing a truck and an armored vehicle and speeding toward the border with Israel. The truck became stuck, and the driver detonated a suicide bomb inside. However, the armored vehicle navigated Israel’s border barriers and continued down the highway until an Israeli warplane and tank destroyed it, killing seven militants.[32]

In response to the attack—one of the deadliest on Egyptian armed forces since the 1973 war with Israel—President Mohamed Morsy sacked the director of the General Intelligence Service, Murad Mowafi, himself a former governor of North Sinai.[33] Days later, Morsy removed armed forces Chief of Staff Sami Anan and Defense Minister Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, elevating Military Intelligence Director Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to the role of defense minister.[34] The Egyptian military said it would “avenge” the attack, describing the militants as “nonbelievers.”[35]

Beginning of Militarization in North Sinai

The Rafah attack marked the beginning of the militarization of the Sinai conflict. In response, the armed forces deployed more troops to North Sinai, backed by tanks, armored vehicles, and artillery, calling it Operation Eagle II.[36]

In a step that drew substantial criticism, Morsy dispatched a delegation of Islamist politicians and religious figures to mediate with the North Sinai militants.[37] But Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis declined to participate, and on September 21, 2012, three of its fighters launched an attack on an Israeli military patrol on the Egypt border, in which they and an Israeli soldier died.[38]

Though Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis had yet to shift the focus of its attacks to Egyptian targets, its propaganda began to indicate growing disillusionment with the Muslim Brotherhood-led government in Cairo, which had been voted into office in 2011 and 2012.[39] Then, on July 3, 2013, as mass protests against Morsy’s rule and calls for early elections peaked, al-Sisi, the defense minister elevated by Morsy a year before, forcibly removed the president.

From July to August 2013, political upheaval loomed in Cairo between the new leadership and those who remained opposed to al-Sisi.[40] Then, on August 14, Interior Ministry forces, with support and approval from al-Sisi and the military, brutally cleared mass protest sit-ins at Rab’a al-Adawiya and al-Nahda squares in Cairo, resulting in the deaths of at least 904 people in one day.[41]

Less than a month later, on September 5, a powerful bomb ripped through the armored convoy of Interior Minister Mohamed Ibrahim as it drove through a neighborhood in northeast Cairo, killing one police officer and wounding 10 other members of the police and 11 civilians.[42] Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis claimed credit for the assassination attempt, which marked a dramatic escalation in post-uprising political violence. The group promised further attacks on police and military in retribution for the August mass killings. They called on fellow Muslims “to come together around their mujahideen (holy warrior) brothers in their war against those criminals.”[43]

Joining the Islamic State

The next month, Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis stepped up its attacks. On October 19, 2013, a car bomb detonated outside a military intelligence building in Ismailia, a city on the Suez Canal, wounding six soldiers.[44] In December, another suicide bomber detonated himself inside the Interior Ministry’s security directorate in the governorate of Dakhalia, killing 16 people and wounding 132 others.[45] On January 24, 2014, a remotely detonated car bomb exploded outside the Cairo security directorate, killing four people.[46] On February 16, a suicide bomber attacked a bus carrying South Korean tourists from Sinai to Israel, killing three and the Egyptian bus driver and wounding dozens more.[47]

On October 24, 2014, Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis carried out its largest operation up until that point: a coordinated daylight attack on two Egyptian security positions in North Sinai, killing at least 31 soldiers and wounding at least 41 others.[48]

On the night of the attack, al-Sisi, who had been elected president that June, declared a three-month state of emergency in North Sinai.[49] Five days later, Prime Minister Ibrahim Mehleb issued a decree ordering the “isolation” and “evacuation” of 79 square kilometers of Sinai land along the Gaza border, encompassing all of Rafah.[50] Over the next four years, the military would demolish over 6,850 buildings in Rafah, including thousands of residential homes, permanently evicting families with little or no warning or support afterward.[51]

On November 10, 2014, just two weeks after the attack, Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis formally pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in an online audio statement.[52] After the statement, the group began referring to itself on its social media accounts and online postings as Wilayat Sina’, or Sinai Province, styling itself as a territorial division of the Islamic State.[53]

Following militant attacks on army and police bases in al-Arish in early 2015, the Egyptian president issued a decree to create the Unified Military Command for the East of the Suez Canal and Combating Terrorism. General Osama Roshdy Askar first led this unified command, followed by General Mohamed Abdella and Mohamed al-Masry in 2017 and 2018. The unified command is supposed to supervise and guide counterterrorism efforts of the Second and Third Field Armies that constitute the major troop deployments in North Sinai.

On July 1, Sinai Province carried out simultaneous daytime attacks on more than 15 army and police installations in North Sinai, killing dozens of soldiers.[54] After 12 hours of fighting, only attacks by Egyptian F-16 fighter jets managed to drive the group’s fighters out of Sheikh Zuwayed.[55] Two weeks later, the group claimed responsibility for a missile attack that damaged an Egyptian navy ship near al-Arish.[56]

Association with the Islamic State appeared to drive not only an uptick in the group’s attacks but a further radicalization that justified attacks against different groups.[57] On October 31, 2015, Sinai Province claimed the bombing of a passenger airplane flying from Sharm al-Sheikh to St. Petersburg, Russia, which killed all 224 people on board.

Several media reports said that, beginning sometime in 2015, and with Egypt’s approval, Israel began airstrikes against militants inside North Sinai. Over the next two years, the reports said, Israel conducted more than 100 such strikes. American officials told The New York Times, which broke the news of the campaign, that the strikes “played a decisive role in enabling the Egyptian armed forces to gain an upper hand against the militants.”[58] Israeli’s government did not comment, and while Egypt’s army initially denied the reports, in January 2019, the US news program 60 Minutes aired an interview with President al-Sisi in which he confirmed his country’s cooperation with Israel in the Sinai Peninsula.[59]

In November 2017, militants stormed al-Rawda Mosque in Baer al-Abd, a town in North Sinai, during packed Friday prayers and killed 311 people, including 27 children, in a blaze of gunfire.[60] The Sinai Province group did not officially claim responsibility, but the men who attacked the mosque carried Islamic State flags.[61]

In late December 2017, Sinai Province released a statement and video showing a long-range attack on a military helicopter at al-Arish Airport, using a Kornet anti-tank missile.[62] The attack apparently targeted Defense Minister Sedki Sobhy and Interior Minister Magdy Abd al-Ghaffar, who were visiting the airport and nearby at the time. Though they survived, the missile strike killed one of the pilots, a security guard, and Sobhy’s bureau chief.[63]

Following the attack, President al-Sisi said they needed to clear a five-kilometer wide buffer zone around the airport to protect it, evicting hundreds of residents and razing thousands of hectares of farmland. No residents appeared to receive compensation and no decrees were issued to define the buffer zones and methods of compensation.[64] Later, in July 2018, the army began building a six-meter tall wall surrounding the buffer zone.[65]

Increasingly Abusive Counterinsurgency Campaign

After the Rawda Mosque attack, al-Sisi ordered the military to secure the Sinai Peninsula in three months, and publicly ordered his commanders to use “all brute force” to do so.[66] A few weeks later, the army began operation “Sinai 2018,” which included a wave of arrests and killings.[67]

As of mid-2018, the army had almost entirely demolished Rafah and evicted nearly all its 70,000 residents.[68] Such demolitions have continued and expanded to encompass other parts of North Sinai. In January 2018, President al-Sisi announced a government plan to bulldoze the populated five-kilometer buffer zone around the airport in al-Arish, Sinai’s capital, potentially evicting thousands residents.[69] And by late 2018, the government began applying policies that civil society activists described as aiming at “dispossessing” their lands and evicting more cities in Sinai. Some of these laws require Sinai residents to “prove” their Egyptian descent in order to keep their lands.[70]

The army has failed to decisively defeat Sinai Province, but it maintains a suffocating grip on everyday life in the governorate, stifling freedom of movement, raiding homes, conducting mass arrests, and seizing possessions without due process guarantees. The state of emergency and continuous military operations have taken a toll on residents’ daily lives, especially in Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed, two cities in the east of Sinai. [71] Many Sinai residents who spoke with Human Rights Watch said that while they had initially welcomed the army's expansion into the Sinai in 2012, believing that army forces would treat them better than the traditionally-abusive police forces, their attitudes quickly changed in 2013 due to pervasive fear of arrest by army forces. Many residents said they constantly risk being falsely labeled by authorities as “terrorists.”

Authorities tightly control movement within North Sinai and between the governorate and mainland Egypt, restricting commerce and causing regular shortages of food, water, and medical supplies to towns caught between the military and the militants. They regularly shut all internet and cellular networks across large stretches of North Sinai for days at a time.[72] Egyptian authorities defend such measures as necessary to disrupt militant attacks.[73]

Despite the government’s denial of violations, a few rare official statements have admitted problems and violations of Sinai residents’ rights. For example, a member of the National Council for Human Rights wrote on his Facebook account in 2018 that “many residents” had never received compensation despite having their houses demolished or their farms razed, or having been arrested and “released after long periods” without charges or seeing their family members killed or injured. “All state institutions must work to alleviate the tragedy of these victims… Otherwise, we leave an open wound and a gap that widens with time,” the council member wrote.[74]

Media reports have suggested that dozens of army and police officers, some of them from senior ranks or elite forces, have joined militant groups, including Sinai Province.[75] Human Rights Watch reviewed the prosecution file of a case that was brought before a military court in Ismailia concerning militancy in Sinai that involved 42 defendants, including two former army officers.

As the conflict has endured, the decades-long marginalization of the area has been coupled with a near-absolute prohibition of independent reporting from Sinai. Pro-government media rhetoric instead frequently describes Sinai residents as “traitors” or the root of the problem, who are at best “are not helping the government enough” to eradicate the militant groups.[76] Some of these media articles call on the army to “burn Sinai,” “hit it with Napalm,” “evict its residents,” “destroy it completely,” and “leave no body alive there.”[77]

The years-long state of emergency and curfew in North Sinai also has minimized the potential for peaceful opposition and civil society activities, reinforced with an effective ban on independent gatherings. Such activities are mainly led by “the People’s Committee in North Sinai,” an independent group comprising Sinai residents and community leaders. However, the group has been able to hold only a handful of meetings over the last several years. They demanded that the government allows such meetings and issued several statements criticizing the authorities’ arbitrary arrests, orders of forced evictions, and the lack of essential services such as electricity and water. A 2017 statement accused the government’s counterterrorism policies of “targeting Sinai residents” and not “terrorism,” and that the main aim of the abusive army-led campaign is to force Sinai residents to leave their lands.[78]

On July 8, 2017, Gen. Mahmoud Mansour, a former Military Intelligence senior officer, summarized the government’s mentality in the conflict when he told a TV show:

Enough with kindness, and enough [saying that] they are civilians and enough with slogans … and enough with human rights... Those who are afraid to lose their lives, leave Sinai.[79]

II. Legal Analysis

The Egyptian army’s battle with the ISIS-affiliate Sinai Province has transformed North Sinai governorate into what many interviewees described as a conflict zone. After five years of Egyptian army operations, as well as the likely participation of the Israeli military, many towns and highways are now highly securitized military zones. During this period, Sinai Province militants have demonstrated a high degree of organization, establishing checkpoints for periods of time in urban centers, running “Sharia courts” and “grievance committees,” and carrying out punishments in areas where they exert influence. Egyptian officials, including President al-Sisi, have frequently used the word “war” to describe the situation in Sinai as early as in 2014.[80]

Human Rights Watch believes hostilities in North Sinai most likely amount to a non-international armed conflict (NIAC) that began sometime in 2014. In addition to the requirements that an armed conflict exists and that it is “not of an international character,” i.e., between government forces and non-state actors or armed groups, determination of a NIAC relies on three additional criteria: 1) the level of violence rises above the threshold of simply internal disturbances; 2) the violence is of a “protracted nature”; and 3) militant or insurgent groups possess armed forces functioning under a certain command structure.[81] Human Rights Watch’s research over four years shows that all of these criteria appear to apply in North Sinai.[82]

In December 2018, the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, a well-known academic institution focused on international law, released a study that also argued the situation in North Sinai is a NIAC based on the relevant criteria.[83]

The State Information Service, a government entity tasked with engaging with foreign media correspondents, released a legal study of the Sinai conflict in July 2018 co-authored by Judge Adel Maged, deputy head of Egypt’s Cassation Court. The report stated that the “legal nature of the government response (to the militancy in Sinai) … is one that is usually regulated internationally by the rules of armed conflict, and locally by military laws.”[84] The report authors, however, claimed that members of “armed terrorist groups” enjoy no protection under international humanitarian law because, the authors argue, members of these groups are “illegal combatants.”[85]

High Level of Violence and Protracted Nature of the North Sinai Conflict

The level of violence in North Sinai has escalated over the past several years, with the Egyptian armed forces now deploying at least 41 brigades, including up to 25,000 soldiers, according to President al-Sisi in a January 2017 statement.[86] According to Israeli media, citing the Egyptian military’s chief of staff, this troop deployment had doubled by March 2018 to 88 battalions, comprising around 42,000 soldiers.[87] These forces included hundreds of tanks, armored vehicles, and other heavy machinery. Airstrikes by Apache helicopters and F-16 jetfighters have become a regular phenomenon in North Sinai during the conflict and naval forces have also been mobilized on the coast of North Sinai.

The army claims to have killed at least 3,076 “militants” from January 2014 to June 2018, and according to a Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy study, militants killed at least 1,226 army and police officers and soldiers in the same period of time.[88] Government forces and the militants have killed and injured hundreds of civilians. While these casualty figures stem from the conflict’s recent escalation, the Egyptian army actually began its military operations in the area in August 2011 with “Operation Eagle” over 8 years ago.

The army has announced the killings of several ISIS leaders throughout their operations. According to a media review Human Rights Watch conducted, prosecutors have charged or accused at least 725 defendants in different cases with belonging to Sinai Province or its predecessor, Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis. Military and criminal courts sentenced some of those defendants to death, mostly residents of Sinai, and some have already been executed. The government also released the names of at least 18 militant leaders it claimed to have killed between 2013 and June 2018, as well as arresting 4 others. [89]

Sinai Province’s Level of Organization

The government-sponsored July 2018 legal study of the North Sinai conflict said that “those terrorist groups possess an organized quasi-military nature.” The study said:

The seriousness of the attacks launched by terrorist groups [in North Sinai] is exemplified by the large numbers of attackers, the types of weapons used, and the level of planning and methods of fighting used, which make the national criminal and punitive frameworks incapable of dealing with them. [90]

Interviews with victims of Sinai Province abuses and assessments by analysts who closely monitor the group indicate that the militant group displays a significant degree of organization, with a hierarchical structure and multiple operational divisions that act in coordination under a unified leadership.[91] Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that militants have set up “nonpermanent” checkpoints and routinely checked residents’ IDs and disciplined individuals for infractions according to their interpretation of Sharia rules in Rafah, Sheikh Zuwayed, and sometimes al-Arish.

Interviewees also stated that Sinai Province runs multiple detention sites where they interrogate detained civilians. Interviewees described what they called “grievance committees,” a Sinai Province division that received residents’ complaints about ill-treatment or injustice inflicted by the group’s members. Human Rights Watch also interviewed a woman who said her husband was a member of the militant group and was killed in an Egyptian army strike in mid-2015. She said that the group maintained a system to take care of the widows and their children. She also said that she feared returning to her community out of fear of arrest.[92]

In several areas of Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed, residents expressed in interviews with Human Rights Watch their fear in reporting the militants to the government, due to the militants’ level of control and influence in the area they lived.[93]

Frequently, the group has released written and video statements about its operations in North Sinai or about the death of its members and leaders. Several former army and police officers have joined the group, according to the group’s statements and media reports. [94] In November 2018, the group announced the killing of its top leader in Sinai, Abu Osama al-Masry.[95]

International Law and Egypt’s National Laws

In a NIAC, international humanitarian law (IHL) applies. IHL recognizes that a states’ armed forces can target fighters and other military targets but provides a range of guarantees and safeguards concerning the protection of civilians and the treatment of prisoners. Egypt ratified all four Geneva conventions in 1952, as well as its two additional protocols (in 1992) that constitute the main body of IHL.

Human rights law continues to apply during armed conflicts. Egypt is also bound by UN and African human rights standards, including those adopted by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which emphasize a government’s obligations to respect fundamental rights while combating terrorism.[96]

The Egyptian Code of Military Justice (Law 25 of 1966) is largely outdated and many of its provisions do not correspond to IHL. It allows officers “in the field” to establish “field courts” consisting of army officers, without any judicial supervision, to try and sentence captured members of an opposing army or armed group immediately. Human Rights Watch is not aware of the Egyptian army in Sinai establishing such courts. Egypt’s military code also does not clearly establish the rights of detainees in an armed conflict. It does, however, punish those convicted of “inflicting violence” on individuals who are hors de combat, that is, a wounded combatant who is no longer taking part in hostilities.[97]

Egypt’s draconian, unreformed Emergency Law (Law 162 of 1958) grants security forces nearly unlimited powers, with little or no judicial checks and balances, including seizing civilian properties and houses, compelling citizens to do “any work” security forces deem necessary, and providing wide latitude to forcibly evict residents.[98] The government has imposed the state of emergency in North Sinai uninterruptedly since October 2014. Egypt should drastically amend its Emergency Law to bring it in accordance with its constitution and international obligations.

In 2015, the government passed a new counterterrorism law that espouses an overly broad definition of terrorism and contradicts international standards. The law punishes journalists for publishing news about counterterrorism operations that contradicts official statements with fines up to half a million Egyptian pounds [around US$27,800].[99]

Education at Egyptian military academies appears to lack instruction on human rights or international humanitarian law, and Human Rights Watch is not aware of any legal education or training offered to military conscripts.[100] The International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC) 2017 activity report on Egypt said that the ICRC trained 25 senior police officers and 2,911 army officers and cadets, as well as 96 officers assigned to peacekeeping operations on IHL and International Human Rights Law (IHRL). The report said this was “a positive step towards integration of IHL into military education and then into the military doctrine.”[101]

The government-sponsored July 2018 legal study on Sinai claimed that the fight against terrorist groups is regulated by what it claimed was a “new model” in international law that it called “state versus terrorist groups armed conflict model.” Under this model, the authors argue the “unlawful combatants” do not enjoy any protections stipulated by IHL. They said that the use of “brute force” in Sinai is “justified” because regular law enforcement forces “proved unable” to face those armed groups.[102] The report claimed that civilians are no longer civilians if they become “hostile” to the state. And if they carry arms then they become “unlawful combatants.”[103]

Such an approach appears to ignore the basic principles of international humanitarian law, in particular the overriding requirements to distinguish between civilians and combatants at all times and that attacks may only be directed at combatants, not civilians.[104] The Egyptian government should disregard and withdraw this legal opinion and publicly reaffirm that it will comply only with IHL and its obligations under human rights law. Several resolutions adopted by the UN General Assembly and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights emphasized that governments should “ensure that any measure taken to combat terrorism complies with their obligations under international law, in particular international human rights, refugee and humanitarian law.”[105]

Israel, and any other country involved in the North Sinai conflict, should ensure that its operations do not violate international standards and do not amount to assisting Egypt in the commission of internationally wrongful acts.[106]

War Crimes and other International Crimes

The Egyptian authorities have repeatedly denied any wrongdoing in the course of conducting military operations in Sinai. In October 2013, a senior military commander said: “We haven’t harmed one innocent citizen. We didn’t even injure or kill a cat.” He claimed that the army could have ended its operations in Sinai in six hours if the army was allowed to disregard human rights.[107]

The abuses that Human Rights Watch documented by both government security forces and the Sinai Province militant group are serious violations of IHL and some of them appear to amount to war crimes, including the use of torture and the deliberate killings of civilians and prisoners.

Individuals who commit serious violations with criminal intent—that is, intentionally or recklessly—may be prosecuted for war crimes. Individuals may also be held criminally liable for assisting in, facilitating, aiding, or abetting a war crime. All governments that are parties to an armed conflict are obligated to investigate alleged war crimes by members of their armed forces.

In addition, some of these crimes such as arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, torture, unlawful killings, and the forcible transfer of population may constitute crimes against humanity that fall within the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court. Crimes against humanity are defined as such crimes that cause great suffering or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health and are committed “as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack.”[108] The failure of the Egyptian government to investigate, or even admit, such serious abuses reflect a larger failure of the senior officials who know, or must have known, about these abuses as and did not appear to investigate or prevent their recurrence.

Arbitrary Arrests, Secret Detentions, Ill-Treatment, and Torture

International human rights law continues to apply during a conflict situation and although some rights may be slightly more restricted during a publicly declared state of emergency threatening the nation, other rights are “non-derogable,” meaning they can never be suspended or modified regardless of the situation. In a NIAC, all detainees should be swiftly brought to a judge to decide their detention or release, and they should never be ill-treated, tortured, or extrajudicially executed. They should only be kept in official places of detention, and authorities should swiftly release them in case of lack of evidence of wrongdoing and compensate them for the periods they spent in custody without charge.

Egyptian security forces, especially the military, have repeatedly violated all of these guarantees. Government forces have arbitrarily arrested and forcibly disappeared Sinai residents on a widespread and systematic scale. The majority of prisoners from North Sinai are held in three detention facilities where Human Rights Watch documented inhuman conditions, and where detainees are often deprived of access to the outside world, including their families and legal counsel.

An arrest is arbitrary and unlawful when it happens for no internationally-recognized offenses, such as when someone is arrested for exercising their fundamental rights, or when a person is deprived of their right to due process, such as when they are arrested without a basis in law or without swift judicial review, or when a person remains in detention after the sentence ordered by a court has ended.[109]

Former detainees told Human Rights Watch that the military also tortured them.[110] As documented in this report, military detention sites are not only secret, they also lack the basic minimum requirements according to UN guidelines, including adequate access to food and health care. Some detainees died in custody because of ill-treatment and a lack of medical care. The prohibition on torture is recognized as a fundamental guarantee for civilians and persons hors de combat. This also means that combatants, when detained, should never be tortured, ill-treated, or killed. Torture consists of the infliction of “severe physical or mental pain or suffering” for purposes such as “obtaining information or a confession, punishment, intimidation or coercion or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind.”[111] The UN Convention Against Torture (CAT), which Egypt ratified in 1986, categorically bans torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.[112]

Every detainee must be treated humanely at all times. Visits from family members must be allowed if practicable. Under applicable human rights law, children should be detained only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time. In all cases, children should be held separately from adults, unless they are detained with their family. Human Rights Watch documented that the army held children detainees for months in the same secret detentions with adults and abused them.

As documented in this report, the militants in Sinai have also used secret detentions and have subjected detainees to legal proceedings that do not correspond to any international standards. They have used hanging and flogging among other means of punishment which likely amount to torture.

The ban against torture and other ill-treatment is one of the most fundamental prohibitions in international human rights and humanitarian law. No exceptional circumstances may justify torture, and states are required to investigate and prosecute those responsible for torture.

Detaining Children

As documented in this report, the Egyptian army held child suspects in secret detentions alongside adult detainees. When charged, child detainees faced prosecution before military and criminal courts instead of juvenile courts.

International law allows authorities to detain children in limited situations, but only if formally charged with committing a crime, not merely as suspects, and only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.[113] Children should never be detained alongside unrelated adults.[114] In cases where children were members of armed groups, they should not be “treated as security threats … and administratively detained or prosecuted for their alleged association,” which harms their best interests as well as society’s interest in their reintegration, the UN Secretary General reported in 2016.[115] In order to fulfill its obligations under the Optional Protocol on Children and Armed Conflict, which Egypt acceded to in 2007, authorities should provide children accused of involvement with militant groups with “all appropriate assistance for their physical and psychological recovery and their social reintegration.”[116]

Extrajudicial Killings