"They Came and Destroyed Our Village Again"

The Plight of Internally Displaced Persons in Karen State

Glossary

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations

CBO Community-based organization

CIDKP Committee for Internally Displaced Karen People

DKBA Democratic Karen Buddhist Army

HURFOM Human Rights Foundation of Monland

ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross

IDP Internally Displaced Person

IMNA Independent Mon News Agency

KESAN Karen Environment and Social Action Network

KHRG Karen Human Rights Group

KIO Kachin Independence Organization

KNLA Karen National Liberation Army

KNPP Karenni National Progressive Party

KNU Karen National Union

MNEC Mon National Education Committee

NLD National League for Democracy

NMSP New Mon State Party

PKDS Pan-Kachin Development Society

SLORC State Law and Order Restoration Council

SPDC State Peace and Development Council

TBBC Thailand Burma Border Consortium

UNHCR United Nations High Commission for Refugees

UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund

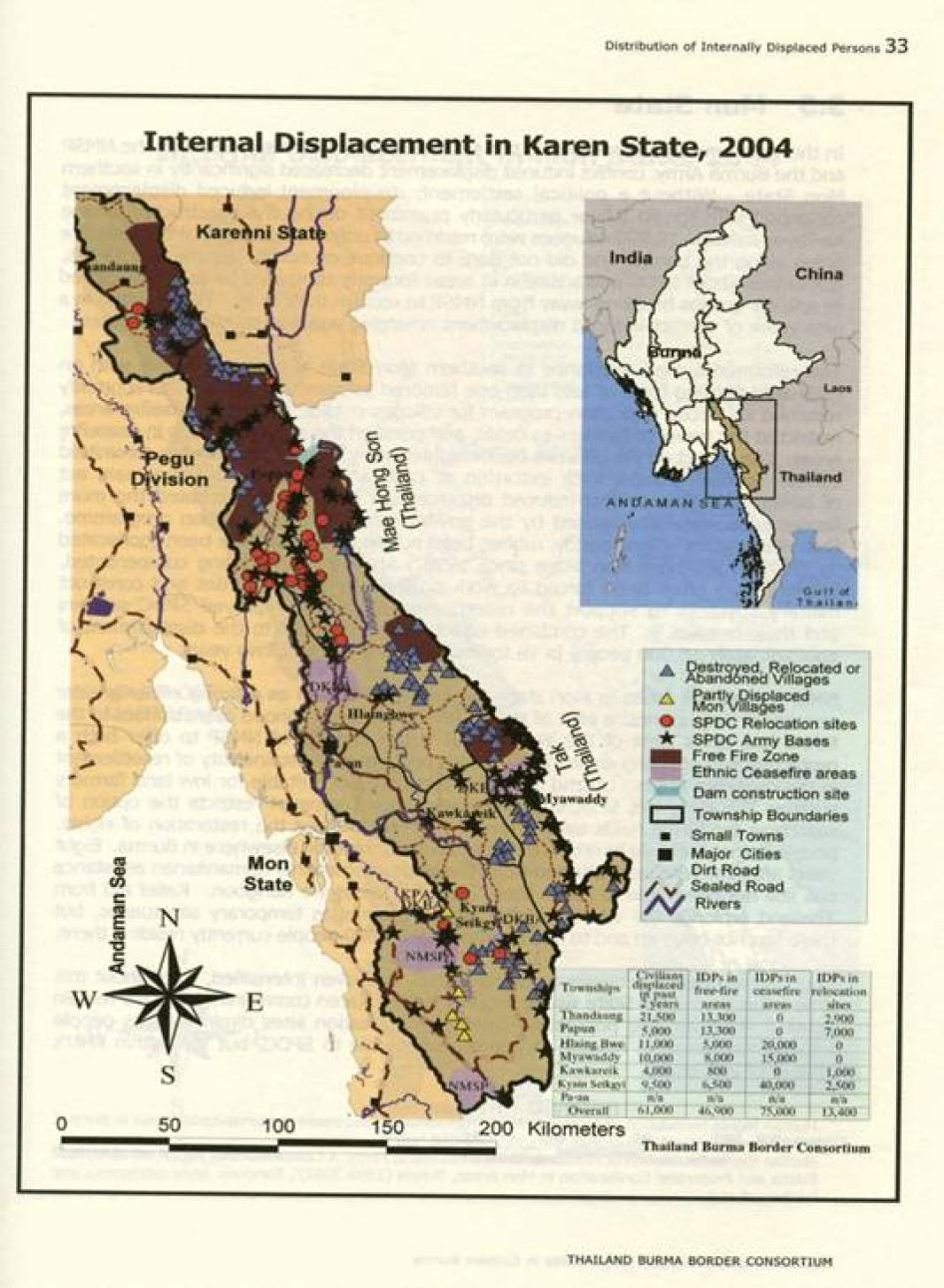

Map 1: Internal Displacement in Karen State, 2004

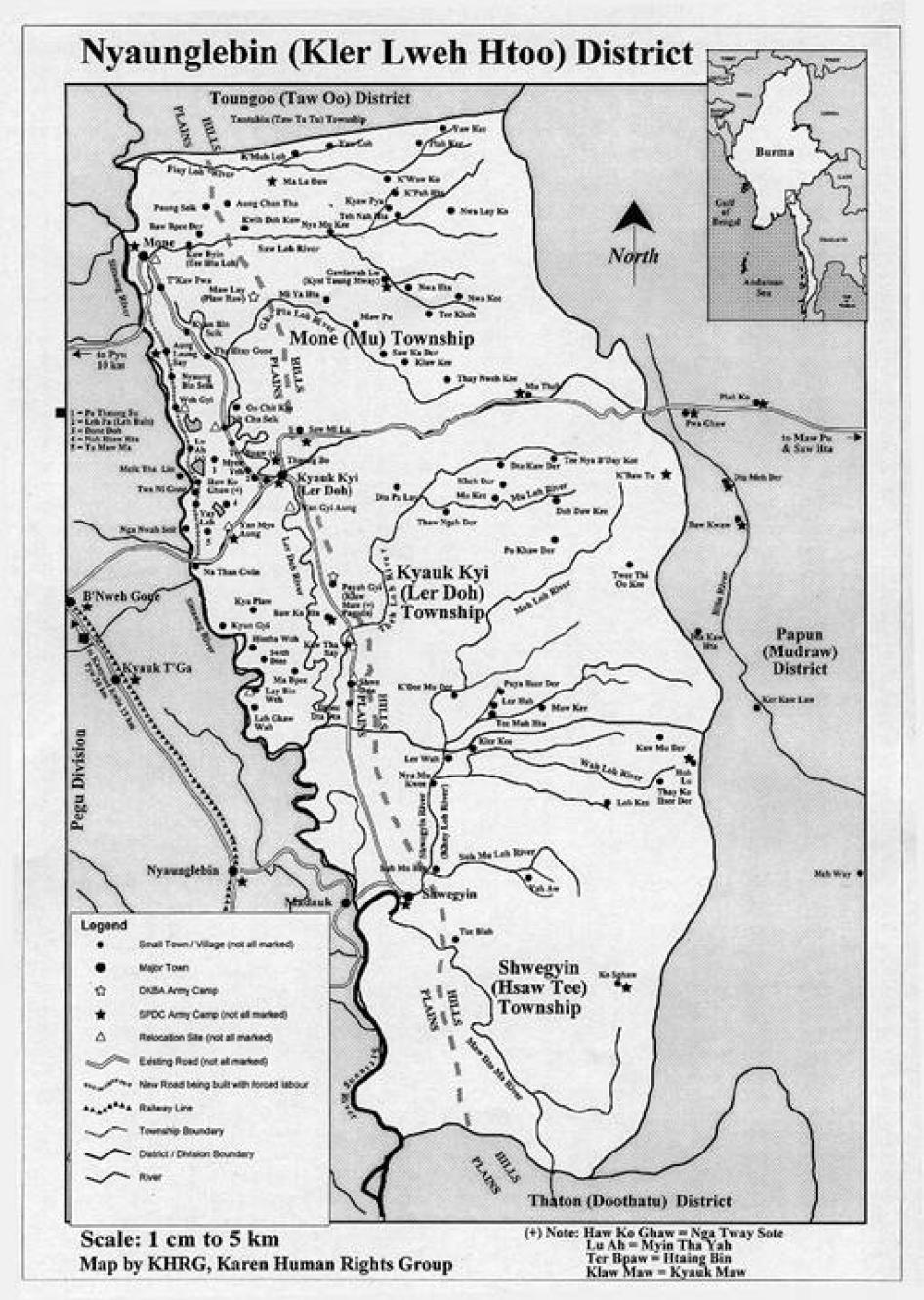

Map 2: Nyaunglebin (Kler Lweh Htoo) District

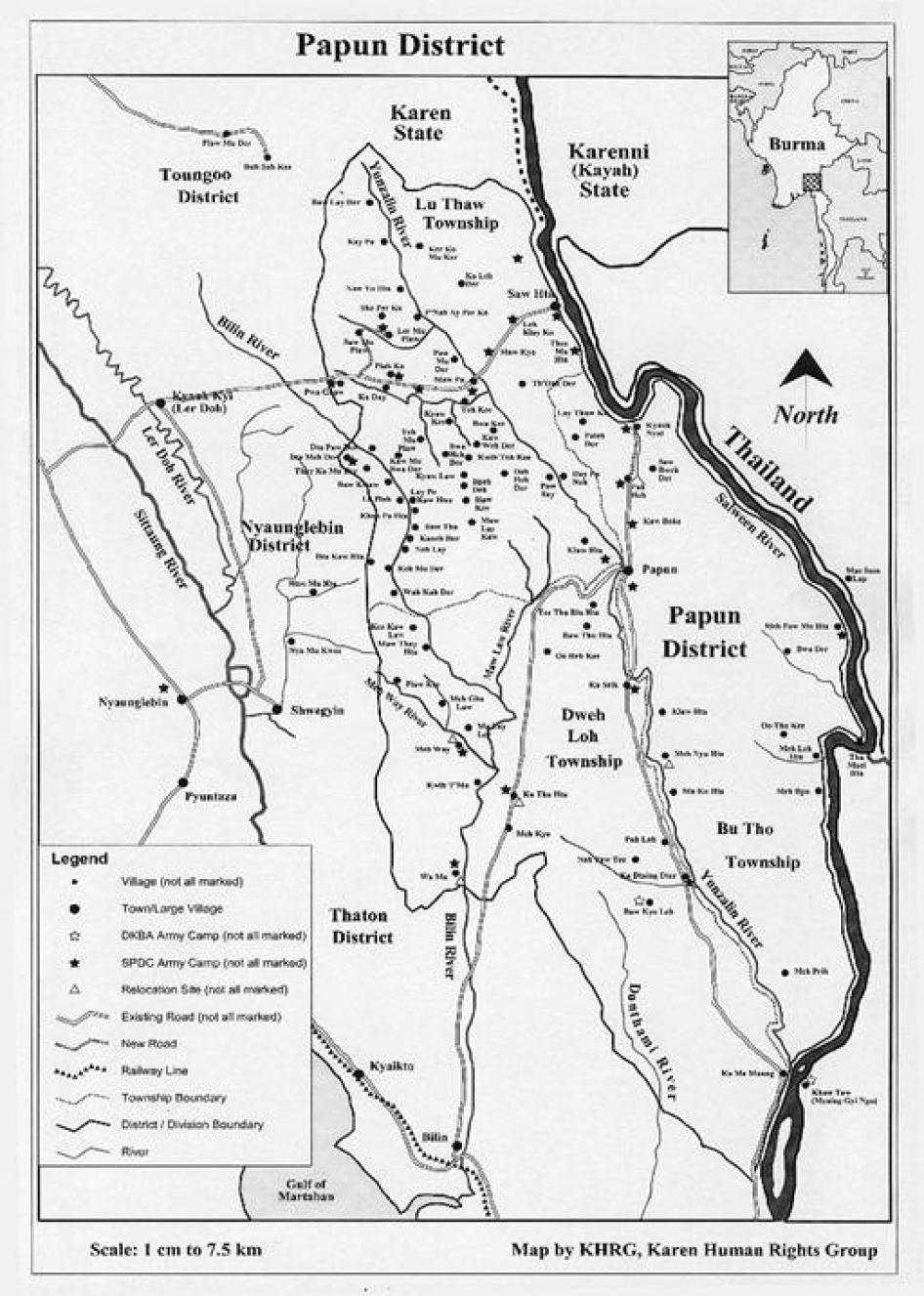

Map 3: Papun District

I. Summary

When the Tatmadaw entered my village they killed men and beat women when they caught them.[1]

Burmese soldiers came into Tho Mer Kee village and burnt down all the houses. They killed all our pigs, goats and chickens––and then shot the buffalos for fun.[2]

We had to flee to the jungle, where we stayed for a week, with very little food. Then we returned to re-build our homes, and try to farm again. However, the next year, they [the Tatmadaw] came and destroyed our village again.[3]

While the nonviolent struggle of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi against the Burmese military government's continuing repression has captured the world's attention, the profound human rights and humanitarian crisis endured by Burma's ethnic minority communities has largely been ignored.[4]

Decades of armed conflict have devastated ethnic minority communities, which make up approximately 35 percent of Burma's population. The Burmese army, or Tatmadaw, has for many years carried out numerous and widespread summary executions, looting, torture, rape and other sexual violence, arbitrary arrests and torture, forced labor, recruitment of child soldiers, and the displacement and demolition of entire villages as part of military operations against ethnic minority armed opposition groups. Civilians bear the brunt of a state of almost perpetual conflict and militarization.

Violations of international human rights and humanitarian law (the laws of war) by the Tatmadaw have been particularly acute in eastern Karen state, which runs along the northwestern border of Thailand. One woman described to Human Rights Watch more than twenty years of Tatmadaw brutality:

The Burmese Army troops first attacked in November 1979, while we were harvesting our fields near Ler Kaw village. They shot and killed my sister, who was only thirteen, and my cousin, who was fifteen. We had to flee, but they chased after us and shot and killed another villager. There was no fighting near the village at that time. The Burma Army troops just wanted to kill us Karen villagers.

The Burmese soldiers attacked us again at Htee Hto Kaw Kee, in 1992. They shot and killed my husband and injured other villagers. The soldiers burned down our houses and killed and ate our animals. They also burned our rice barn, destroying 190 tins of rice. [They also] killed my son-in-law, who was just collecting betel nut in the forest. He [had] small children.

In January 1998, at Lo Kee village, my cousin's husband was killed by Burmese troops when they entered the village. Many people fled to the jungle. In March 2002 my other cousin's husband was also killed. Their house and livestock were destroyed too.

The woman's mother added more details to the account, and clarified that the Burmese troops faced no armed resistance that could justify their attack on the villagers:

I will never forget our suffering at Ler Kaw village. When the soldiers shot my thirteen-year-old daughter, her intestines came out. Her father and I tried to save her, and escape. She was in agony, and screaming, but we couldn't do anything to ease her pain. She died after an hour. We haven't done anything against the government. All we had in our hands when their troops attacked was our paddy, and harvesting tools. If the soldiers had called us, we would have gone to talk with them. They didn't have to shoot.[5]

One result of the Tatmadaw's brutal behavior has been the creation of large numbers of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees among Burma's ethnic minority communities. Conflict and its consequences have been going on for so long that in many ethnic minority-populated areas, continuous forced relocations and displacement––interspersed with occasional periods of relative stability––have become a fact of life for generations of poor villagers.

The scale of the IDP problem in Burma is daunting. Estimates suggest that, as of late 2004, as many as 650,000 people were internally displaced in eastern Burma alone. According to a recent survey, 157,000 civilians have been displaced in eastern Burma since the end of 2002, and at least 240 villages destroyed, relocated, or abandoned. The majority of displaced people live in areas controlled by the government, now known as the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), or by various ethnic armed groups that have agreed to ceasefires with the government. But approximately eighty-four thousand displaced people live in zones of ongoing armed conflict, where the worst human rights abuses continue. Many IDPs live in hiding in war zones. Another two million Burmese live in Thailand, including 145,000 refugees living in camps.

Karen State is the location of some of the largest numbers of IDPs in Burma. Since 2002, approximately 100,000 people have been displaced from Karen areas,which include parts of Pegu and Tenasserim Divisions. Though a provisional ceasefire was agreed in December 2003 between the SPDC and the Karen National Union (KNU), sporadic fighting continues. Tatmadaw military operations against the KNU's army, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), in the first months of 2005 caused numerous deaths and injuries to civilians in poor villages along the Thai border. They also forced many civilians to flee internally or to Thailand. For example, at least 9,000 civilians were displaced in Toungoo District, in the far north of Karen State bordering Karenni State, and in Nyaunglebin District in northwest Karen State, during major Tatmadaw offensives between November 2004 and February 2005.

The majority of Karen IDPs have been forced out of their homes as a direct result of the Tatmadaw's "Four Cuts" counter-insurgency strategy, in which the Burmese army has attempted to defeat armed ethnic groups by denying them access to food, funds, recruits, and information from other insurgent groups. H.T., a twenty-eight year-old Karen from Dooplaya District, described his experience with the Tatmadaw in January 2005:

There were two groups [of Tatmadaw soldiers]. The first was commanded by Lt. Soe Myint Aw, and the second was commanded by Captain Toe Toe Aung. They had about sixty men each. Lt. So Myint Aw told us that the "strategic commander" gave them orders to attack the village. I just ran. It took twenty minutes to walk to the border. We stayed there on Monday. There is a motorbike and a phone that everyone in the village can use. We had to leave them there. I could hear machine gun fire and mortars when I was running to the borderline. I am afraid for my family, and very afraid that the SPDC will kill me. It's possible I will be tortured when I go back. Eleven SPDC soldiers were killed by the KNU. I don't want to go back to see the [SPDC] soldiers. I want to go back to my village when the fighting stops but I will be prepared to run once again.[6]

This report describes the situation in government-controlled areas, including relocation sites, which are generally not accessible from across the Thailand border. The report identifies two main causes of displacement:

• Displacement due to armed conflict as a direct result of fighting, or because armed conflict has undermined human and food security and livelihood options; and

• Displacement due to human rights violations, particularly land rights caused by Tatmadaw andmilitia confiscation of land and other violations of land rights, especially in the context of natural resource extraction, such as logging and mining. Other rights violations, such as forced labor, killings, torture, and rape, also cause displacement.

The report describes patterns of abuse and forced relocation over a period of many years. It documents how serious violations of international humanitarian law and human rights abuses continue to occur in some parts of Karen State, such as Toungoo and Nyaunglebin Districts, while other areas are relatively quiet. It recommends a need to think of new and more realistic answers to the dilemmas faced by IDPs, many of whom may not be able––or may not want––to go home again.

For this report, Human Rights Watch interviewed community leaders, representatives of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), staff at community-based organizations (CBOs), U.N. officials, and many others. Most important, we interviewed forty-six Karen IDPs living in the Papun hills, in mid-late 2003, and along the Thai border, in early 2005. These forty-six individuals altogether were displaced more than one thousand times. Incredibly, five individuals had been forcibly displaced more than one hundred times. One of these five, an elderly woman, first fled to the jungle during World War II, when Japanese soldiers came to her village.

All the interviewees for this report had been farmers and continue to derive most of their food from working their own or others' rice fields. These fields remain susceptible to destruction by Tatmadaw patrols. Displacement often means that new land must be cleared for farming, rather than farmers being able to return to former swidden fields in sustainable rotation after fallow swiddens have regained their fertility. Over time, the disruption of traditional agricultural practices has seriously undermined livelihoods and caused encroachment by swidden farmers into primary forest, rather than rotating their plots in secondary forest customarily used for swidden agriculture.

Many IDPs have been displaced for some time, and live alongside others who are not––or have not recently been––displaced. Their needs may therefore be similar to those of other vulnerable populations in peri-urban and rural Burma.

The main problems identified by interviewees were lack of consistent access to food; insufficient income and livelihood problems; human rights abuses and poor physical security related to displacement and fighting; lack of access to education and health services; and, finally, the problem of landmines, which destroy both land and their victims' lives. Their primary need is to be able to farm properly, without disturbance, and thus improve income and food security, as well as better access to education and health services. All wanted to, as one interviewee put it, "live in peace and with justice."

Most of these problems are linked to longer-term structural problems, and can only be addressed in the context of socio-economic––and above all political––solutions to Burma's protracted ethnic conflicts.

The findings of this report caution against assuming that all IDPs necessarily want to return "home." Returning home can be a problematic concept for people who have been on the move for long periods of time.Many IDPs may wish to return home, if it still exists, but others may want to stay put or resettle elsewhere. Some who have returned home or have otherwise resettled still face major problems, while others have not. Some have not moved and built new lives in the place to which they were displaced, often in the jungle hills or in a relocation site.

Thus, those providing assistance should avoid taking a one-size-fits all approach to meeting the needs of IDPs. Instead, the focus should be on individual choiceand the needs of specific communities. Indeed, the U.N. Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, which summarize existing international law as it applies to IDPs, make choice the touchstone. Competent authorities have a duty to "establish conditions, as well as provide the means" to allow voluntary resettlement and integration in the place to which people are displaced, if that is their choice.[7]

An understanding of long-term patterns of forced displacement should inform the design of humanitarian, development, and socio-political interventions on behalf of the displaced. One aspect that deserves careful consideration is the effect of ceasefires on the human rights situation and on displacement. Over the past decade many armed ethnic groups have entered into ceasefires with the military government in Rangoon. In some parts of the country, ceasefires have meant a reduction in the most severe forms of human rights abuses, though this has not usually led to greater respect for other basic rights, such as freedom of expression or the right to due process of law. But in many cases, ceasefires have been quietly accompanied by the reemergence of local civil society actors. This has been one of the most important, yet under-studied, aspects of the ceasefires in Burma.

The SPDC and KNU agreed to an informal ceasefire inDecember 2003. In some parts of Karen State, the situation began to stabilize. Across the whole of Tenasserim Division, and much of lower and western Karen State, there has been less fighting and fewer of the most severe type of human rights violations, such as extrajudicial executions and torture, than before. SomeIDPs are beginning to return from hiding places in the jungle and from relocation sites to build more permanent houses and grow crops other than swidden rice. However, the Tatmadaw continues its aggressive use of forced labor, especially on road-building projects, land confiscation, and arbitrary taxation in many areas. It has recently stepped up attacks on a variety of armed ethnic groups. Under the right conditions, a ceasefire between the SPDC and the KNU could deliver a substantial improvement in the human rights situation, creating the space in which local and international organizations can begin to address the urgent needs of Karen IDPs. But the situation may yet return to guerilla warfare and full-scale counterinsurgency.

Many of the ceasefires are now under threat. Since the purging of General Khin Nyunt last October, hard-liners in the SPDC have attempted to undermine ceasefires agreed between Rangoon and several armed ethnic groups since 1989. In mid-2005, the future of these ceasefires looks more and more uncertain.

If the SPDC and KNU reach a genuine settlement––an outcome about which Human Rights Watch takes no position––the current transitional period may develop into the type of post-ceasefire scenario seen in Mon and Kachin States since the mid-1990s. There may be more space for civil society to emerge. CBOs and local NGOs can play important roles in the needs analysis, planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation stages of projects. This is particularly true in remote areas inaccessible to international agencies. Donors can assist this process with careful, well-targeted grants to capable local organizations.

Sadly, experiences in Mon and Kachin states show that displacement does not necessarily come to an end with the cessation of armed conflict. Instead, the causes of displacement may change, as the Tatmadaw expands into previously contested areas and confiscates land as part of its efforts to consolidate control and make money. Increased and more industrialized natural resource extraction and other economic activities, such as large-scale agricultural production and development-induced activities, including road and bridge construction, can lead to further displacement. These factors indicate the importance of focusing on the protection of economic, social, and cultural rights, including the critical need to clarify land tenure for indigenous groups and to protect their customary land rights.

In April 2005 the U.N. Commission on Human Rights called upon the Burmese government:

(a) To end the systematic violations of human rights in Myanmar, to ensure full respect for all human rights and fundamental freedoms, to end impunity and to investigate and bring to justice any perpetrators of human rights violations, including members of the military and other government agents in all circumstances;

(b) To end widespread rape and other forms of sexual violence persistently carried out by members of the armed forces, in particular against women belonging to ethnic minorities, and to investigate and bring to justice any perpetrators in order to end impunity for these acts;

(c) To end the systematic enforced displacement of persons and other causes of refugee flows to neighboring countries, to provide the necessary protection and assistance to internally displaced persons, in cooperation with the international community, and to respect the right of refugees to voluntary, safe and dignified return monitored by appropriate international agencies.[8]

Human Rights Watch urges the military government in Rangoon to implement these recommendations immediately. It must issue orders to its troops to end all attacks on civilians. In addition to constituting serious human rights abuses, these attacks undermine any hopes the SPDC may have of reaching a political settlement with representatives of Karen communities. To address the internal displacement problem in Karen areas, Human Rights Watch also urges:

- All parties to the conflict to allow greater international access to conflict areas to provide humanitarian assistance and protection to IDPs. Landmine mapping and clearance is a particularly urgent unmet need. International and local agencies should employ protection staff and provide protection training to all other field staff, and offer such training to all appropriate government officials.

- The development and implementation of policies regarding individual and community land rights and access to land in Burma, including restitution of, or compensation for, property confiscated, stolen, or illegally occupied, and respect for customary rights to land.

- Emphasis on the principle that every solution should be voluntarily chosen through the informed consent of the displaced individual, whether that solution be integration, relocation, or return home.

- That the provision of humanitarian and development assistance is not misused by the government and the Tatmadaw to further military objectives in conflict-affected, often traditionally semi-autonomous, areas. It is critical that international agencies such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) should be able to function independently without unnecessary restrictions.

- Donors to work with local NGOs and rights-respecting local government officials and ceasefire groups to provide services, such as formal and informal education, vocational and skills training and materials, health services, including training of medics, micro-credit programs, natural resource management and environmental protection.

- The provision of aid and assistance through civil society groups and networks, many of which are operational in areas inaccessible to international agencies. Building the capacity of such groups must be a priority. Donors should foster the emergence of under-represented groups, such as non-Christians, minorities within Karen State, and women, and should not concentrate all resources on a narrow set of professional and westernized NGOs. Genuine partnership and joint ownership of projects with civil society actors should be encouraged. Needs and vulnerability assessments should mainstream conflict resolution, protection and gender issues, and highlight policies that effectively address the needs of the poor. Both the SPDC and KNU must be persuaded to let these processes take place, even if they do not like the outcome.

A more detailed set of recommendations can be found in Section VII at the end of this report.

II. Background

Aung San Suu Kyi, the NLD, and the SPDC's failed national dialogue

After a quarter-century of one-party military rule, hundreds of thousands of student and other demonstrators took to the streets across Burma in 1988, calling for democracy and the rule of law. The ruling State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) brutally crushed the movement, killing thousands of civilians. Over the next few years, the SLORC further consolidated its control, establishing its own mass organizations. However, despite severe restrictions on freedom of speech, association, and assembly, many brave individuals and groups have continued to speak out and work for democracy and development at both the community and national levels.

In a reaction to widespread protests, the SLORC held elections in May 1990. The highly popular and outspoken Aung San Suu Kyi, who had been placed under house arrest in 1989, and her party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), won 82 percent of the seats. However, the generals refused to allow the NLD and its allies to form a government, instead imprisoning several hundred more political opponents the following year. Since that time, the junta has insisted on maintaining military rule, changing only its name in 1997 to the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC). Since its refusal to recognize the results of the May 1990 election, the military government has resisted all options but a managed transition––by the military–– to a vaguely described military-led "democracy."

Despite winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 for her nonviolent resistance to the government, Aung San Suu Kyi has been in and out of house arrest since 1989. Many NLD leaders and party activists have also spent a great deal of time arbitrarily detained under house arrest or imprisoned under horrendous conditions. In the mid-1990s, and again in May 2003, Suu Kyi was briefly released, but her efforts to peacefully mobilize supporters were met again with violent military suppression when on May 30, 2003, an SPDC-organized mob at Depayin killed at least four of her bodyguards and possibly dozens of onlookers.

For decades across Burma, human rights abuses, many of them committed by the Burmese army, or Tatmadaw, have been rampant. Common tools of state control include torture, rape, and forced conscription of child soldiers. By mid-November 2004 there were more than 1,400 political prisoners in Burma, and although the SPDC announced at the same time it would release 3,937 prisoners, including a handful of prominent political prisoners, there has been no commensurate political liberalization.

In August 2003, Burma's newly appointed Prime Minister and Chief of Military Intelligence, General Khin Nyunt, announced a reconvening of the National Convention (NC) to draft a new constitution, one of seven steps in the government's "roadmap to democracy."[9] Although this process was clearly dominated by the military, it was effectively the only national-level discussion about about instituting a democratically elected government and dealing with the concerns of Burma's many ethnic groups. Yet, three days before the National Convention reconvened, Burma's two main opposition parties announced that they would not join the convention. The government had failed to meet demands to release Suu Kyi and reopen NLD offices across the country, or to demonstrate to the NLD and the United Nationalities Alliance (UNA), a coalition of ethnic nationality partieselected in 1990, that it would permit genuine debate over key issues. The National Convention has therefore been widely perceived as illegitimate, both inside Burma and abroad.

Internal divisions within the SPDC boiled over when on October 19, 2004, Khin Nyunt––regarded as the second or third most powerful person in the country––was arrested. The fall of Khin Nyunt was preceded and accompanied by the closing down of his powerful military intelligence apparatus and the arrest of many of his associates. Khin Nyunt was replaced as prime minister by Lt-General Soe Win, the man responsible for orchestrating the attack on Aung San Suu Kyi's motorcade at Depayin on May 30, 2003.

To most observers, these events signaled the consolidation of power by the hard-line junta Chairman and Vice-Chairman, Generals Than Shwe and General Maung Aye. The government was careful to portray the move as a change of personnel, rather than of policy. A week later, Than Shwe made the first trip by a Burmese head of state to India in more than twenty years. With continued political and economic support from China and an ever-close relationship with India, the generals remained in a strong position to try to ride out western sanctions and any unease among its Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) partners.

Fifty years of ethnic conflict

While the world's attention has been focused on national-level politics and the fate of Aung San Suu Kyi, much less attention has been paid to the highly complex and brutal abuses of ethnic minorities in more remote parts of the country. The situation is particularly acute in areas of ongoing armed conflict.

Ethnic minorities constitute at least 35 percent, or eighteen million, of Burma's estimated fifty-two million people. Historically, the "ethnic question" has been at the heart of Burma's protracted political, social and humanitarian crises. Ethnic insurgent armies have operated along Burma's borders for decades in several areas since independence in 1948. However, by the early 1980s, the Tatmadaw had gained the upper hand against the ethnic rebels, and the areas under their control began to shrink. Increasing numbers of civilians became displaced by the fighting in eastern and northern Burma, and were no longer able to retreat to relative safety behind the "front lines" of the conflict and rebuild their villages. Instead, many had to flee across the border to Thailand, China, India, or Bangladesh.

Much recent political science literature has focused on the "opportunity motives" for insurgency. However, Burma's rebellions have long been driven by a mixture of genuine grievances and political-military-economic opportunism. Especially following the military take-over by General Ne Win in 1962, ethnic nationality elites have been excluded from meaningful participation in politics, while minority-populated border areas have experienced chronic underdevelopment, combined with often unsustainable natural resource extraction. Meanwhile, in its largely successful campaigns against a myriad of ethnic and communist insurgent organizations, the SPDC and its precursors have extended militarized control into previously semi-autonomous border areas, causing massive social, economic and human disruption––and greatly weakening the armed opposition.

Every Burmese regime since the establishment of military rule in 1962 has sought to suppress ethnic minorities and bring previously insurgent-dominated border areas under Rangoon's control. The strategy has had military and ethnic dimensions: not only would ethnic minority communities be broken up and their ability to resist weakened, but it would also allow for the spread of state-sponsored "Burmanization," in which minority cultures, histories, and political aspirations would be eliminated in favor of a "national" identity. The Burmese regimes in essence view all ethnic minorities as a potential security threat[10], and, as a result, have "allowed security issues to come to dominate all aspects of government policymaking."[11]

The Tatmadaw's often brutal counter-insurgency strategies set the tone for coercive methods of dealing with dissent––whether armed revolt, nonviolent political dissent, or apolitical civilians––over the following decades.[12] The Tatmadaw's "Four Cuts" (pya ley pya) counter-insurgency strategy, used since 1963, best embodies the state's approach to suppressing ethnic minorities. A rebel group has been fully "cut" if it no longer has access to new recruits, intelligence, food, or finances. This approach aims to transform "black" (rebel-held) areas into "brown" (contested/free fire) areas, and then into "white" (government-held) areas.

In response, ethnic insurgent groups have positioned themselves as the defenders of minority populations, adopting guerrilla-style tactics. This has invited retaliation against the civilian population, against which the insurgents have been unable to defend villagers. As a result, rural Burma has now essentially been engaged in a half century of chronic, low-grade warfare. Human rights abuses are rife, most notably torture in detention and rape, and the conflict has further deepened the poverty of an already poor population. Traditional ways of life have been destroyed.

In order to undermine perceived support for armed ethnic or communist groups, since the 1960s the military government and Tatmadaw have created well over a million IDPs by forcibly moving thousands of ethnic nationality villages across the country. IDPs are highly vulnerable to Tatmadaw abuses and have serious difficulty maintaining livelihoods. Even after conflict has died down, many are unable to return to their previous farms and settlements, due to the prevalence of landmines and confiscation of land or other resources. Plans for massive infrastructure projects in border areas––including dams and new roads––will also prevent the resettlement of IDPs and repatriation of refugees.

Ethnic nationality groups have sought to advance their agenda politically as well as militarily. Although most of the 1,076 delegates to the 2003 National Convention were handpicked by the SPDC, they included over one hundred representatives from armed ethnic nationality groups that have concluded ceasefire agreements with Rangoon, such as the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) and New Mon State Party (NMSP). Despite their reservations about the process, most groups apparently attended the convention in good faith in the hope of registering their aspirations on the national political agenda and using the ceasefire agreements to address some of the key issues that have caused armed conflict in Burma for over five decades.

Although demands varied to some extent, there was general agreement among them to press for granting states more authority, transforming ceasefire armies into local security forces, and, most importantly, establishing a federal union of Burma, under the rubric of "ethnic or national democracy." In expressing their concerns on the national political stage, ethnic groups have made it harder for the international community, while pursuing the resolution of political issues in Rangoon, namely the restoration of multiparty democracy in Burma, to ignore the "ethnic question."

However, the convention's Convening Work Committee refused to put the proposals of the ethnic groups on the agenda, claiming they fell outside the National Convention's current remit.[13] The ceasefire groups were told that their proposal would be submitted directly to the Prime Minister, General Khin Nyunt, yet his ouster in October 2004 means that the proposals remain in limbo.

The National Convention did not reconvene until February 17, 2005. It did so without the NLD and the Shan State Army-North (SSA-N) ceasefire group, which boycotted the convention following the arrest of several Shan leaders in early February. These included Khun Htun Oo and Sai Nyunt Lwin, Chairman and General Secretary of the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy (SNLD), the party with the second largest number of MPs-elect from 1990. The Shan leaders were detained following a meeting in Taunggyi (southern Shan State) on February 7, where plans were discussed to form a stronger coalition between Shan State ceasefire groups and the 1990 parties, who were not at the convention.[14]

On February 13, six ceasefire groups issued a statement, repeating their demands of the previous year and calling for a review of the draft constitution's Principle No. 6, which provides that the military will continue to play a leading role in politics. They also asked for non-ceasefire groups to be allowed observer status at the convention, to allow disagreements and debate, and for the convention minutes to record such dissenting voices. Upon arrival, delegates to the convention were cut off from each other and from most contact with the outside world.

On March 7, 2005, U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan told the United Nations Commission on Human Rights that:

Most regrettably, it…remains the Secretary-General's view that the National Convention, in its present format, does not adhere to the recommendations made by the General Assembly in successive resolutions.

He thus reiterates his call on the Myanmar authorities, even at this late stage, to take the necessary steps to make the roadmap process more inclusive and credible. The Secretary-General also encourages the authorities to ensure that the third phase of the roadmap, the drafting of the constitution, is fully inclusive. A national referendum will be held after that. It is his considered view that unless this poll adheres to internationally accepted standards of conduct and participation, it may be difficult for the international community, including the countries of the region, to endorse the result.[15]

In mid-March it was revealed that the National Convention would take another break, from mid-April. Some observers interpreted this as a sign of "unsolved problems with ethnic ceasefire groups."[16]

In late April 2005 a battalion of the Shan State National Army (SSNA) ceasefire group was pressured by the SPDC into surrendering its weapons. Many observers viewed this as an escalation of the government's crackdown on Shan opposition groups.[17] Then, on April 29, another northern Shan State–based ceasefire group, the Palaung State Liberation Army (PSLA), was also forced to surrender its weapons. This development may indicate that the government is intent on picking off ceasefire groups one-by-one, persuading the smaller groups and less well-organized groups to disarm first, before moving on to the better established Wa, Kachin, Mon, and other militias.[18] In late May the SSNA leader, Colonel Sai Yi, took his three remaining battalions back to war with Rangoon, merging his forces with the Shan State Army-South (SSA-S), which had never agreed to a ceasefire.[19] This was the first time in a decade that a ceasefire group had resumed armed conflict with the military government.

It is an open secret that the Thai government is pressuring the KNU to sign an agreement with Rangoon because it wants to be rid of the 140,000 mostly Karen refugees in the kingdom and is keen to exploit the economic opportunities that peace may bring to its borders. KNU negotiators have emphasized the extent of the displacement crisis in Burma, and suggested that the plight of IDPs be addressed before any refugee repatriation is undertaken. Most aid workers and diplomats agree that the time is not yet right to begin sending refugees back from Thailand.

The Karen

Despite the limited opportunities for community development and peace-building represented by the ceasefires in conflict-related areas, much of Karen and Karenni States, southern Shan State, and Tenasserim Division––in the east and southeast of Burma––are still affected by low-level armed conflict. For the civilian victims of civil war, the situation remains dire.

The five to seven million Karen in Burma and approximately 350,000 Karen in Thailand speak twelve mutually unintelligible, but related, dialects. Between 80-85 percent of Karen are either S'ghaw (mostly Christian and animist living in the hills) or Pwo (mostly lowland Buddhists). About 25-30 percent are Christian, 5-10 percent are animist, and the rest are Buddhist. An estimated 30 percent of Karen people live in urban settings and 70 percent in rural areas. About 40 percent are plains dwellers and 60 percent live in the hills.[20]

As demarcated by the government, Karen State consists of seven townships (Pa'an, Kawkareik, Kya-In Seik-Gyi, Myawaddy, Papun, Thandaung and Hlaingbwe), with a population in 1995 of approximately 1.3 million.[21] The percentage of Karen living in Karen State has decreased considerably due to the outflow to Thailand.

Rejecting the government's administrative boundaries, the KNU has organized the Karen "free state" of Kaw Thoo Lei[22] into seven districts, each of which corresponds to a Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) brigade area.[23] The districts are divided into twenty-eight townships and then into groups of villages administered as a unit by the KNU––that is, in areas where the KNU still exercises some influence. This civilian structure is paralleled by an often more extensive KNLA military administration.

The majority of the Karen live in Tenasserim Division (KNU Mergui-Tavoy District), eastern Pegu (or Bago) Division (which overlaps with Nyaunglebin District), Mon State (which overlaps with parts of Duplaya and Thaton Districts), and the Irrawaddy Division, areas that are mostly government-controlled.[24] Neither the government nor the KNU has ever conducted a reliable population survey. However, a report issued in 1998 estimated the population of Kaw Thoo Lei at between 2-2.4 million people, or about half the Karen population of Burma.[25]

The Karen have been subject to repeated displacement. For example, following the introduction of the "Four Cuts" in 1974-5, approximately forty-three villages in the Nyaunglebin District were forcibly relocated at least twice.[26] According to the highly respected Thailand Burma Border Consortium (TBBC), there were eighteen thousand IDPs in eastern Pegu Division in mid-2004, while a community-based organization working inside Burma reported as many as 29,807 people displaced in the same area at government-controlled sites alone. Similarly, in Papun District, a "Four Cuts" operation beginning in the mid-1970s displaced an estimated fifty thousand people.[27] Further Tatmadaw operations caused about nine thousand refugees to flee to Thailand in 1996 alone.[28]

Although Karen nationalists have resisted Rangoon's domination for more than fifty years, their internal divisions have been equally persistent, making it difficult to articulate a unified position on behalf of the entire nationality group. It has also been easier for the military government in Rangoon to "divide and conquer" the Karen.

Like most ethnic insurgent groups, the KNU has claimed to be fighting for democracy in Burma––especially since the great 1988 "democracy uprising." Although the KNU retains a sometimes contested legitimacy in many Karen communities, the democratic ideal has not always been honored in practice, and the liberated zones have often been characterized by a top-down tributary political system, aspects of which recall pre-colonial forms of socio-political organization.

After a series of military setbacks, dating back to the 1970s, and with greatly diminished support from the Thai government and army, the KNU today is a greatly weakened force. The KNLA still has some five thousand-seven thousand soldiers, but it no longer represents a significant military threat to the SPDC.[29] However, the KNU's longevity alone brings it considerable credibility among the wider Burmese opposition. It is also still considered a key player by elements within the SPDC.

Like other insurgent organizations in Burma, the KNU has an interest in controlling, or at least maintaining, populations in traditionally Karen lands––as a source of legitimacy, and of food, intelligence, volunteer soldiers, and porters. KNLA soldiers regularly organize village evacuations to protect villagers from Tatmadaw incursions.[30] However, cases of KNLA soldiers purposefully targeting civilians are rare. Since the provisional ceasefire in 2003 there has been virtually no displacement as a result of KNLA offensive operations.

In an incident that has undermined intra-Karen relations along the border for a decade, disaffected Buddhist Pwo-speaking KNLA soldiers who felt excluded by the dominant Christian S'ghaw-speaking KNU elite broke from the mainstream Karen insurgentgroup in December 1994. The establishment of the Democratic Karen Buddhist Organization (DKBO) and Army (DKBA) in December 1994, which may have taken place with encouragement from local Tatmadaw units, also reflected legitimate grievances among the KNU rank-and-file regarding the Christian-dominated organization's alleged discrimination against the Buddhist majority in Kaw Thoo Lei.

The emergence of the DKBA consolidated a major split in the Karen insurgent ranks. The DKBA command-and-control structure is weak, and many of these units enjoy almost complete autonomy, and/or answer to local Tatmadaw commanders. DKBA troop strength is difficult to gauge. Informed sources suggest that the number of active soldiers is about three thousand-four thousand. It currently fields three brigades.[31]

The DKBA often acts as a proxy militia army for the Tatmadaw, deflecting some criticism for the state's harsh policies. Like the Tatmadaw, it uses displacement as a means of controlling populations and resources and undermining its rivals. Between 1995-98 it instigated at least twelve major attacks on KNU-controlled refugee camps in Thailand, killing more than twenty people,[32] and it has launched attacks on KNLA positions following the announcement of a provisional KNU-SPDC ceasefire. In addition, many DKBA commanders and soldiers must be considered conflict entrepreneurs who have been personally empowered and enriched as a result of the fighting.

Since the fall from power in October 2004 of General Khin Nyunt, a number of militias have come under pressure to hand over their arms to the government. Several DKBA units in particular are under pressure to surrender to the Tatmadaw. As result a number of Karen soldiers have returned to the KNU in 2005.[33] In late May, reports emerged that DKBA units were beginning to withdraw from parts of northern Karen State, including Nyaunglebin District, and being replaced by the Tatmadaw.

Ceasefires

Until 1989, the Tatmadaw had been fighting two interconnected civil wars: one against the ethnic nationalist insurgents, and another against the Communist Party of Burma (CPB). The CPB collapsed in early 1989 and disintegrated into four ethnic militias, which quickly agreed to ceasefires with Rangoon.

Since 1989, ceasefire arrangements have been made with some twenty-eight armed ethnic nationality groups. The nature of the ceasefire agreements are not uniform, although in all cases the ex-insurgents have retained their arms and still control sometimes extensive blocks of territory (in recognition of the military situation on the ground). The ceasefires are not peace treaties, and generally lack all but the most rudimentary accommodation of the ex-insurgents' political and developmental demands. These agreements have been dismissed by some as benefiting vested interests in the military regime and insurgent hierarchies. Civilians in these 'ceasefire areas' still experience a wide range of problems.

However, in many cases there is also something of a peace dividend from the ceasefires. Human rights abuses, displacement, and livelihood issues are considerably less acute in ceasefire areas, so much so that the TBBC reports that the IDP population in those areas has increased, as IDPs move out of war zones and into ceasefire zones. While many violations continue, such as forced labor, land confiscation, and arbitrary taxation, in areas where ceasefires have held serious violations against the integrity of the person, such as extrajudicial killings and torture, have decreased.[34] This pattern is already emerging in post-armed conflict Karen areas.

The variable vulnerability to abuse is illustrated by the TBBC's October 2004 report on "Internal Displacement and Vulnerability in Eastern Burma." The report stated that "the internally displaced population in ceasefire areas has increased by between 20-30 percent during the past two years," as IDPs in hiding move to relatively more secure areas.[35] A range of indicators show that conditions for IDPs in ceasefire areas are significantly better than in free-fire zones or relocation sites. Reports of human rights abuses (with the exception of forced labor and local "taxes," which are extracted by ceasefire groups) are lower in ceasefire areas than in free-fire areas, partial/mixed administration areas or relocation sites.[36] People in ceasefire areas are reportedly less likely to be forcibly displaced (on average, 0.2 times/year) than those in free-fire areas (1.4 times), partial/mixed administration areas (0.3 times), or relocation sites (1 time), and are also less likely to become casualties of war (0.2 percent, compared to a range in other situations of between 0.3-2.2 percent).[37]

One crucial but largely unrecognized benefit of the ceasefire process is the rise of community-based organizations (CBOs). These not only address humanitarian and developmental needs, but also make it possible to debate and articulate their communities' specific concerns. Whether the ceasefire process can be sustained, and move from the current negative peace––characterized by a significant decrease in armed conflict––into a positive, peace-building phase, will be fundamental to the success of reconstruction and national reconciliation efforts.

In this climate of risk and uncertainty, the KNU, Burma's most significant remaining insurgent group, has been attempting to negotiate a ceasefire with Rangoon. On December 10, 2003, the KNU announced a "gentlemen's agreement" to stop fighting, shortly after an exploratory meeting in Rangoon between military intelligence officers and a team selected by KNU Vice-Chairman General Bo Mya. These were the first KNU-government contacts since 1995-96.

Following the announcement, both the KNU and SPDC ordered their military units to cease offensive operations. However, the Tatmadaw subsequently repeatedly violated the agreement. Talks continued in Rangoon in mid-January and in Moulmein in February.[38] These yielded a vague "agreement in principle," with specifics to be discussed over the coming year. The KNU pressed to establish concrete mechanisms to address human rights and other ceasefire violations, and to discuss the urgent needs of IDPs and other conflict-affected civilians.

During the January 2004 talks, a military government representative for the first time admitted that the Tatmadaw had engaged in extensive population relocations, as part of its counter-insurgent strategy. He also accepted that, with an end to the fighting, these people might be able to go home, and receive appropriate assistance.[39] But the next round of talks was delayed for several months, following an incident on February 23 in which KNLA 3rd Brigade troops attacked a Tatmadaw camp in western Nyaunglebin District, killing several soldiers and liberating weapons and some communications equipment. Although the KNLA returned the seized material, the SPDC used this ceasefire violation as a ground to further delay talks.

In March 2004 Paulo Sergio Pinheiro, the United Nations "Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar," stated that:

Among other related positive developments, the most notable is the resumption of peace talks between the Government and the largest armed opposition group, the Karen National Union. Were human rights commitments to be built into an agreement, this process could significantly improve not only the human rights situation in ethnic minority areas, but also the political climate throughout Burma.[40]

The next few months will determine whether or not a KNU-SPDC ceasefire will be achieved and deliver a substantial improvement in the human rights situation, creating the space in which local and international organizations can begin to address the urgent needs of Karen villagers.

The Monk's Story[41]

I was born at Hgaw Klar. My parents were 'slash and burn' farmers. Then we moved to Paw Mu Lah Hta, and stayed for three years. There was no school and no hospital. If we got sick, we had to buy medicines at nearby Mae Wai. After three years we returned to Hgaw Klar, to do irrigated paddy cultivation. My mother died, and one year later my father got married again. By that time I was five years old.

Then we moved to Pau War Der, to do 'slash and burn' cultivation again. We also got income from dock-fruits. There was a school, which went up to fourth standard.

In 1978-78, when I was twenty-one years old, Tatmadaw Infantry Battalion No. 30 undertook military operations in the area. While we were fleeing to Ta Kaw Khi, one man was shot and wounded. We had no western medicine, so we used traditional cures. He recovered from the wound, but later got a high fever and died. He was fifty years old. During that military operation many people were killed in the area.

In June 1997 we were captured by the Tatmadaw. We were taken back to Shwe Kyin town, where we were kept at Klaw Maw Kho [relocation site]. There was no school, but there was a small hospital. Two villagers from Ga Lay Der died there. After two years, I fled and came back to Ner Khi. Then, because the Tatmadaw attacked in 2002, I fled into Htee Kho Khi, in the jungle. After one year, I moved to Thwa Hta.

My present monastery is made of bamboo. The daka [Buddhist villagers who donate to the monks] give me food, such as paddy and rice, salt and fish paste. The monastery's main income is rice and paddy, donated together with a little money by the daka, who support our religious work.

If we have money we buy medicines, and the daka sometimes donate medicines as well. If the illness is not serious, we buy medicine and we drink it at the monastery. I got sick once and went to the hospital, where I got malaria medicines. Most sick people in the village have diarrhea and vomiting diseases, or a cough with vomited blood, which they say is tuberculosis. These kinds of diseases are common.

The village school was established by Kaw Thoo Lei [the KNU] and local a Karen NGO. I think that there are enough teachers. They carried back the school materials from the eastern part of the state – maybe from [the KNU base at] Day Bu Noh, although I don't know much about this. To begin with, when we built the school, it was only first standard; later we extended it up to third standard, and later fourth standard.

The main problem in our area is that the Tatmadaw attack people, and villagers are unable to support themselves. They face food shortages, have less money and have health care problems.

For example, Saw Pah Lay was shot and killed by the Tatmadaw while he was harvesting in his paddy farm. People kept watch, but the column came by another path, and shot the people who were harvesting; only Saw Pah Lay was hit. Another villager, Nay Pwe Moo Pah, trod on a landmine and was killed. Battles took place in the area more than ten times.

III. Human Rights Abuses of the Karen

In this country, order is the law. Everybody in Burma knows that if you make just one mistake––in word or deed––you'll end up in jail.[42]

Human rights and humanitarian law violations in Karen state

The consequences of the "mistake" of being perceived as an opponent of the SPDC in majority Burman areas of the country have been well documented. But until recently, less attention has focused on widespread human rights violations in ethnic nationality areas of Burma, particularly those inhabited by the Karen. This section documents ethnicity-based persecution by Tatmadaw military assaults on the civilian population, including killings, rape, forced labor, and repeated displacement.

International humanitarian law prohibits acts or threats of violence, the primary purpose of which is to spread terror among the civilian population.[43] All sides in the ongoing armed conflicts in Burma are bound by international humanitarian law (the laws of war). Under the 1949 Geneva Conventions, which Burma ratified in 1992, the conflict with the KNLA is considered a non-international (internal) armed conflict. During an internal armed conflict, government armed forces and their proxy forces and armed opposition groups must abide by Common Article III to the Geneva Conventions as well as customary international humanitarian law. Common Article III as well as international human rights law prohibits the murder, torture or other mistreatment of captured combatants and civilians. Customary international humanitarian law further prohibits attacks against individual civilians, the civilian population and civilian objects, such as homes and temples. Attacks on military targets that cause indiscriminate or disproportionate harm to the civilian population are likewise prohibited.[44]

The Tatmadaw has committed atrocities with the apparent aim to instill fear in the civilian population for several decades. It has attempted to maintain control throughout Karen areas by brutalizing the civilian population. Echoing the logic of the "Four Cuts," military officials defend their actions as necessary in the prosecution of a protracted war against rurally based guerillas.[45] Over the years, Tatmadaw forces have conducted repeated military assaults against ethnic minority villages in which there were no armed opposition forces or other apparent military target. Furthermore, upon taking control of such villages, Tatmadaw personnel have frequently committed abuses against the residents. These atrocities appear designed to instill terror in the civilian population and ultimately weaken opposition to the government.

Nearly all witnesses described the Tatmadaw's attacks as targeting civilians at random and without an immediate military objective. H.D.'s story encompasses many of the violations experienced by the Karen. She is a sixty-seven-year-old S'ghaw Karen woman who moved to Ka Law Gaw Village on the Thai-Burma border as a settler nine years ago. Before that time she claimed that internal displacement was part of her life, and that she has moved "over one hundred times." She has been made to participate in forced labor many times in her life. She can speak Burmese as she was once a village leader in an SPDC controlled area of Karen State.

Before when I lived in another village, I was a village head. Burmese troops treated us very bad and used men as porters and beat some men to death. One SPDC officer asked me if SPDC do good work or bad work? He wanted to know if I preferred SPDC or KNU? I said I didn't know and that the political situation is still on a journey and we will see––whoever takes us to the end is good. I was afraid when I spoke to that officer. I cannot count [how many times I have had to do forced labor]. I have many times been made to show the way. I am very afraid when I have to do this at night. Many times I have been made to carry supplies for one day.

One night I stayed in a cave. It was very uncomfortable ground. It smelled bad and we were all afraid. The next day I was crawling along the ground and I looked up to see a Thai soldier standing in front of me. He told me to go back to my village. I told him the SPDC was there, I cannot go back. I was afraid of this soldier. Finally he said to come in [to Thailand]. The Thai soldiers kept us in the cave for two nights, then they took us to the monastery [in Thailand] until today…I only carried my granddaughter when I ran.

Another case reported to Human Rights Watch typifies the types of abuses committed:

After I harvest the paddy they come and take it all. I have a little left. When the doo-dar [enemy] come into my house I am afraid and think they will rape me. They call me moe- moe ["mother-mother"] to show respect then take everything. A soldier came into my house and began to speak to me, but I cannot understand so I just ignored him. He became angry and threatened me with his knife then took the pot of rice I was cooking. The soldiers are always suspicious and don't trust us. They always ask where are the Karen soldiers. The Burmese soldiers are bad people. I tremble when I see them. I cannot approach [them]. The soldiers…gave us nothing…they only took from us.[46]

H.T., a twenty-eight-year-old Karen from Dooplaya District along the Thai-Burma border near Tak Province, is married with one child. He said that on January 10, 2005––Karen New Year––local SPDC and KNU commanders had worked out a local ceasefire so that the New Year celebrations would not be disrupted. When a messenger sent by the SPDC from another village arrived with an order for the village head to go to the local SPDC column base thirty minutes away, he knew that something was going to happen.

The KNU soldiers were in our village celebrating Karen New Year. The SPDC got very angry and wanted to come to the village. The village head went to negotiate with the SPDC officer five times. The last time three monks and a religious teacher also went to talk to the officer so that they would not attack. In the village a KNU officer, Ner Dah Mya, 201 Special Battalion Commanding Officer, spoke to a DKBA officer who was with the SPDC soldiers to try and stop the fighting. DKBA gave the radio to the SPDC officer but he just shut off the radio. He did not want to talk with KNU. Just attack. Twenty – thirty families stayed on the Karen side on Monday night. Many of them were hiding in a cave. The others went to the Thai side. On Tuesday nearly 350 people went to the monastery inside Thailand traveling in small groups.[47]

Given these civilians' geographical proximity to the Thai border, it is common for them to seek shelter from Tatmadaw assaults there. In some cases, the Thai military is helpful to them.

N.B., a forty-six-year-old S'ghaw Karen farmer, fled the Tatmadaw into Thailand two days before Human Rights Watch interviewed her in January 2005. She spent two nights on the borderline in a cave hiding from SPDC soldiers. Thai soldiers let her come into Thailand where she spent two nights in a monastery with the rest of the people who had fled the fighting. According to N.B., this was the third time in her life she had been forced to flee.

We were afraid that SPDC would come. The fighting started on Monday, Burmese soldiers came, saw two KNU soldiers and started shooting. On Wednesday [January 12, 2005], four people went back to the village and SPDC took them. We don't know what happened to them.[48]

Despite the ongoing ceasefire negotiations between the KNU and the SPDC, abuses of Karen civilians have continued. In December 2003 the Tatmadaw launched a major offensive against the KNU in northern Lu Thaw township and against the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP) in southern Karenni (a short-lived SLORC-KNPP ceasefire broke down in 1995). Like most post-ceasefire military operations, this campaign specifically targeted the civilian population, displacing some 5,500 people, from nineteen villages. The Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG) documented the arrest and summary execution of at least thirty-one civilians in Nyaunglebin District during the period of the ceasefire.[49] The KHRG reported in September 2004 that "villagers have been summarily executed by SPDC columns."[50] There is considerable evidence of further abuses, including summary executions, torture, and looting.[51]

Since mid-February 2004, occasional skirmishes have displaced at least two thousand civilians around Mawchi in Southwest Karenni State, where no ceasefire has been agreed.[52]

In addition to attacks directed against civilians, the Tatmadaw also represses Karenvillagers by stealing, extorting, or destroying their personal property. Customary international humanitarian law prohibits pillage, the forcible taking of private property, and looting. Attacking or destroying objects indispensable to the civilian population, such as food supplies or livestock, are also prohibited, unless such objects are being used as sustenance solely by enemy forces. Collective punishments against a civilian population violate international law.[53]

Such abuses have been particularly acute since 1998, when Tatmadaw battalions were ordered to be self-reliant for food. Since then, the army has been living off the land. Such actions only augment poverty, displacement, and resentment. The KHRG has reported that during the ceasefire negotiations, "SPDC military units have also continued to demand building materials, food, and money from the villagers.

Looting by Burmese troops was a common theme in accounts by the displaced Karen. According to a forty-seven-year-old man:

In 2000 my parents went back into the mountains, to tend their betel nut trees and rice field. While they were weeding the fields, troops from Burma Army Battalion 48 came and shot them, without question. The troops took their livestock and belongings, including 90,000 Kyat in cash, and burnt their hut. The soldiers also shot and killed three men, Saw Tha Pu Loo, Saw Eh Doh Wah, Saw Poh Blay, and injured one.[54]

Soon after the interview was conducted, Tatmadaw Battalion 264 troops arrested and killed the man's brother while he was harvesting betel.

A fifty-year-old woman, N.L., from the Nyanglebin District told Human Rights Watch how "In November 2001, Tatmadaw troops came into Ko Ker village and burnt down all the houses. They killed the pigs and chickens, destroyed the rice barns, and looted our possessions."[55]

According to K.T., the soldiers came every week:

Sometimes the soldiers stayed for two-three days. They ate food, killed our livestock, mostly chickens, and drank alcohol. The soldiers just point at what they want then take it.

K.T. said that she "walked with my children for one full day to reach the border. I was very afraid of landmines but I came anyway." K.T. told Human Rights Watch that her two daughters died soon after she arrived at the borderline, one in Ler Per Her and the other one in a clinic at Mae La refugee camp. Her youngest son is seriously ill.

LST is a thirty-year-old S'ghaw Karen woman.[56] She is married with six children. Many of the people that had lived in Mae Ken village in Eastern Hpa-an District had filtered away in the past year to IDP settlements within Karen State or to live in another village. Stealing by SPDC soldiers was constant, and they forced villager to perform menial labor to support the nearby Tatmadaw base without compensation. She left the village because thesoldiers had taken almost all her possessions and took away most of her small paddy crop yearly.

I dare not stay in the village. The soldiers steal everything from us. We cannot do anymore (stay in the village). We leave because of SPDC soldiers not Ka Thoo Lei soldiers (KNU). They took away all my belongings.

LST's story also demonstrates that such abuses are not only visited on those living in villages, but also on those already displaced. She had to leave for the border with her family in three groups, as a large group would attract the attention of the army patrols. She could also not carry many household goods because it would have alerted the army that she was fleeing.

I did not carry pots or blankets when we fled because the SPDC would know we were running away. Three times we came across SPDC soldiers. I was scared of talking to the soldiers. We could not understand [their questions] and just pointed. We tried to tell them we were just visiting [another village]. It took me nearly twelve hours to walk here with two children. The men [including her husband] came in six hours but they had no children [to bring].

Again, the KHRG notes that, "SPDC officers also continued to enrich themselves through … extortion of money during the early part of 2004." Recent reports from Nyaunglebin District indicate that the Tatmadaw has continued to extort cash, goods and labor from villagers throughout the period of the 'ceasefire'. Army units in the area have reportedly been ordered to collect 100,000 Kyat per month (approximately U.S.$100) from villagers, for a "front line military fund," of which 80,000 Kyat is reportedly transferred to the Tatmadaw Southeast Regional Command headquarters. In total, local KNU sources estimate that 10 million Kyat was extorted from villagers in Nyaunglebin District, in the first half of 2004.[57]

Another villager described the events that led her to flee:

In 1997, the Burma Army shot my brother in the bladder. He bled to death. Later, in 2002 in Baw Gwa village, Burma Army troops twice destroyed our rice barns. The second time, they also burnt our houses while we were hiding in the forest. We were so scared. Later, when we crept back to the village, we had nothing to eat and nowhere to sleep. We were still scared, but also hungry–– and angry too. Now, whenever I hear of or see the Burmese soldiers, my heart beats quickly, and I get all shaky and nervous.[58]

In addition to direct attacks on civilians, Burmese troops often destroy the livelihood of the Karen villagers they target, as reflected in many of the accounts above.

A villager explained how she was displaced:

In 1998 Burma Army troops came to Da Baw Kee village, and asked us to move all of our rice from jungle hiding places into the centre of the village. They said that if we did not obey them, they would burn all our rice and houses. When we had finished moving the rice, they burnt down all of our houses and rice barns anyway (including the newly transported rice too). Then they told us to move to Mae Wai relocation village, or to Ko Sh'rot. Some villagers moved as instructed, but others fled to the jungle.[59]

It is clear from the testimony that in many cases Burmese troops were either attempting to prevent the Karen villagers from surviving in their villages, or gathering provisions for their own needs with total disregard for the civilians.

Forced labor

Despite repeated denials by the SPDC, the Tatmadaw continues to conscript local villagers in Karen areas, including children, to work either as army porters or as unpaid laborers. Many villagers told Human Rights Watch that they fled as a result of these practices, thus maintaining the cycle of abuse and displacement. In addition, since January 2004, the SPDC has also expanded forcible conscription into local militias, which must be supported financially by villagers.[60]

Uncompensated or abusive forced labor is prohibited under international human rights and humanitarian law. International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention No. 29, the Forced Labor Convention, defines forced or compulsory labor as "all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily."[61] The ILO took the unusual step of appointing a Commission of Inquiry to investigate violations of the Convention in Burma and in 1998 it issued a comprehensive report that found the government "guilty of an international crime that is also, if committed in a widespread or systematic manner, a crime against humanity."[62]

In October 2004 the TBBC reported that "more than half [57 percent of those surveyed, but only 39 percent in Karen State] of internally displaced households have been forced to work without compensation and have been extorted cash or property within the last year." Furthermore, 52 percent of those surveyed, but only 39 percent in Karen State, had paid illegal taxes over the past year, and 17 percent––9 percent in Karen State––had food supplies destroyed.[63] CBOs working inside the country also report that forced labor––including forced portering and payment of "porter fees"––is a major problem for IDPs and others across eastern Burma.[64]

A young man of nineteen described his abduction and forced labor at the hands of the Tatmadaw:

I never saw Karen soldiers in the village; only government troops. We faced many problems from the Burma Army. We had to give them money, and build bridges and roads for them, all unpaid. One evening, in August 2003, my mother sent me to the market…on my way home, I was arrested by the Burma Army soldiers, and my arms were tied behind my back. They forced me to get into a truck, which already contained over one hundred people. That night they took us to Taungoo. In the morning they gave us some rice, and then took us to the battalion base at Kyauk Gyi [Ler Doh] town. We were put in a building surrounded by soldiers, where we spent the night. The next day we had to carry rice up the motor road to Mu Then. We eventually arrived at their Ka Pen base, where we stayed for three months.

During that time we cut and carried bamboo for the soldiers, and carried rocks to build their garrison. We were beaten regularly, and had to do lots of very heavy work. We were given very little food, and never any medicines. During those three months I saw six people die of illness. I myself had malaria, and couldn't work properly. However, the troops said that I was being lazy, and punched me on the face and nose, and beat me with a stick on the back of my legs.

Although we had been warned not to run, I couldn't face this existence anymore, so I decided to escape. My malaria was so bad that I couldn't do the work they forced us to do, so I had to get away. I collected a little rice at night, and then asked permission to go to the lavatory. Then I ran and ran, the whole night! Then I ate my rice and drank some stream water, had a nap, and then set-off again into the jungle. I was quite sick by then, because of the malaria. Also, I had to eat the rice un-cooked, as I had no pot and dared not light a fire![65]

K.T., a thirty-year-old S'ghaw Karen woman, fled to the border at the end of 2004 because she could no longer endure forced labor and food shortages. Her village, Mae Ken, used to have forty-fifty families, but now there are just a few left. K.T. said that the fighting in the area had decreased in the past two years, but forced labor and stealing by SPDC soldiers was at the same level. According to K.T., there is a Tatmadaw battalion base close to the village, about two hours walk away, although the villagers can see the base on top of a hill. The villagers would be used almost every day for forced labor, which could mean carrying supplies from the auto road thirty minutes walk from the base, or for security along paths, cooking for soldiers, or repairing buildings or structures for the soldiers.[66] She said they did forced labor, and that she had been taken as a porter often when she was young:

All the time, every week. The SPDC change every six months, so we help them carry [equipment]. Every day we must cook for them and carry water.

LST's husband and fellow villagers were forced into serving as Tatmadaw porters:

My husband would always hide in the jungle when the SPDC came. When they caught him the made him become a porter. He could not grow crops or work…All my family has done (portering). In the last year two people from my village were taken as porters and stepped on landmines. They died. The SPDC did not inform us. We found out from other people.

Another displaced villager cried as he was interviewed:

I was a Burma Army porter so many times that I can't count. When I was a porter, the army gave me very little to eat. We porters were often beaten. Some were beaten to death by the soldiers. They tied us porters together, so we could not escape, and made us carry heavy loads.

In December 1995, while I was in the front-line as a porter, the Burma Army came to my village, Thi P'Yaw Taw, and killed my wife and two children. They burnt down my house, and looted all of the household and livestock. When I came back to my village, I had nothing to live on. I did nothing for a few years, and then in 1997 I remarried, and had another child. I moved to another village, but still they used to come and take me as a porter. In 2002 the Burma Army again caught me, and I had to be their porter. While I was away, the army again entered my village and killed my new wife and child. I was nearly mad with my bad luck and broken heart.[67]

According to some interviewees, the only way to avoid portering is to pay a bribe.[68]

The Burmese military's use of forced labor and porters causes harm well beyond that suffered by those directly involved. This practice of forced labor contravenes international law and has various serious side-effects, such as a reduction in family productivity and a concomitant inability to pay taxes and other fees, leaving those involved at further risk of forced labor.

In addition, as Karen men escaped their villages to avoid forced labor, they often left their families particularly vulnerable to Tatmadaw abuses. The following account is typical of the experience of villagers in northern Karen state:

In 1997 we were living in Da Baw Kee village. My husband fled to the jungle when Burma Army Light Infantry Division No. 77 troops entered the village, because he did not want to be captured and taken as a porter. As I had malaria at the time, I did not flee with my husband, but stayed at home with my five-year-old daughter. The troops came into the house where I was lying, and looted everything; they even stepped on my head! One of the soldiers pointed his gun at my daughter, and took the packet of chilies she was holding – our only food. Later, the soldiers returned, and interrogated me about the whereabouts of my husband.The Captain stole my bracelet (which my mother had given me) 'to give to his wife in Mandalay.' Although we were hungry, they wouldn't let us cook, or even go to the toilet.[69]

B.E., a thirty-three-year-old S'ghaw Karen, is now in the Mae La refugee camp in Tak Province in Thailand. The region he used to live in was classified as a "brown area," meaning it was contested by the Tatmadaw and KNLA. His village was a cluster of houses. Most people were farmers, and there was a small school and a clinic. B.E. had lived in the area for most of his life as a farmer, teacher, and part-time medic.

According to B.E., Burmese soldiers would use the villagers for forced labor routinely. He was forced ten times to "show the way" for Tatmadaw patrols. This could mean impressments for a day or several days. Often this would entail him guiding Tatmadaw patrols through landmine-infested jungle paths. The soldiers treated the people in his village very badly. B.E. said that two Karen women in his village were raped by Burmese army soldiers. He said he was once beaten by a Burmese soldier because he remonstrated with him for stealing a chicken. In late 1998 at a Karen festival, Tatmadaw soldiers came into the village.

They didn't say any words, they just started to beat us. They killed all the livestock, beat people, then left.[70]

In mid-2003, fighting intensified in their area between the Tatmadaw, with their DKBA allies, and the KNLA. Forced labor increased to assist the Burmese soldiers to carry their supplies. The village held a meeting after a month of the fighting to decide what to do. Most of the villagers, but not all, decided they should move to the border away from the fighting. They sent one person to contact the KNLA to let them know they would be leaving, and asking instructions on where to go. "No one wanted to leave. But if I stayed in the village I would always be afraid."

The whole village––thirty families comprising 158 men, women and children––fled nearly a month later. The very morning they fled––September 7––the Burmese soldiers shelled the village with mortar fire, injuring two men and one woman. It took all day to walk through landmine-infested jungle to reach the Moei River that forms the border with Thailand. At the border, they were assisted by KNLA soldiers with small amounts of food, but it was still not safe so they were moved further along the border the next day.

B.E.'s wife was heavily pregnant when they left, and he said she was very afraid of the landmines as they walked. All the people crossed over to the Thai side where they stayed in the jungle at Le Min Jaw, supported by international NGOs. "There was no work to do, we just stayed there." Most of the people arrived in Mae La refugee camp on October 8, 2003, although two families returned to their village in Karen State because family members who were with the DKBA summoned them.

B.E. is not happy to be in the camp, living in a small hut on the steep mountainside.

I don't want to be here but I can't go back. There are so many landmines. How can I go back? Now the DKBA live in the village (area). We cannot go back.

The KNLA also employs some of these tactics. Villagers taken as porters for the KNLA worked without payment, but sometimes received rice from other villagers. Villagers were usually required to work for a day or two. While some Karen justified such human rights violations in the name of solidarity with the struggle against the SPDC, saying they are the same ethnicity and the KNLA protects them,[71] other Karen expressed anger at the KNLA's forced conscription of porters and soldiers.[72]

IV. Internal Displacement

Internally displaced persons are persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized State border.[73]

The U.N. Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, from which the above definition of an IDP is taken, provide an authoritative restatement of existing international human rights, humanitarian and refugee law as it relates to the protection of internally displaced persons. The Guiding Principles address all phases of displacement: providing protection against arbitrary displacement; ensuring protection and assistance during displacement; and, establishing guarantees for safe return, resettlement, or reintegration. By drawing heavily on existing law and standards, the Guiding Principles are intended to provide practical guidance to governments, the U.N., and other intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations in their work with IDPs.