<<previous | index | next>>

Iran

Freedom of expression and freedom of thought are the preconditions of a democratic society. But freedom does not mean chaos.

—Former Iranian President Mohammad Khatami163

When young people meet each other in Iran, one of the first questions they ask each other is, “Do you have a blog?”164 In February 2004, an online “census” ranked Farsi the third-most-popular language for blogs.165 A 2004 poll found that many Iranians trust the Internet more than other news media.166 The trend has spread to the highest levels of the government: former Vice-President Mohammad Ali Abtahi set up a blog to record progress at a conference he was attending, complete with photos.167 A senior cleric maintains a blog-like Web site for Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.168

Much of this Internet activity in Iran, particularly on the part of critics of the government, has developed in response to the relentless crackdown on the independent print media and continuing government control of television and radio. In April 2000, the Office of the Leader and the judiciary launched a campaign against the independent press, closing more than one hundred newspapers and journals in the period since then. The judiciary ordered the arrest of scores of journalists and writers. Saeed Mortazavi, then the judge of Public Court Branch 1410, was the leading force behind the crackdown in its early years, directed mainly at newspapers and journals which had become critical voices for change. He was subsequently appointed to the powerful position of Tehran Chief Prosecutor, a post he holds today.169

Following this crackdown, many journalists and dissidents increasingly relied on the Internet to circumvent the judiciary’s tight control of print media. In 2004, the judiciary, relying on unaccountable intelligence and security forces, began to target online journalists and bloggers in an effort to quash this flourishing new medium.

Iranian Web sites—despite a desperate effort on the part of the government to control the Internet¾nevertheless continue to express opinions that the country’s print media would never run. The government has imprisoned online journalists, bloggers, and technical support staff. It has blocked thousands of Web sites, including—contrary to its claims that it welcomes criticism—sites that criticize government policies or report stories the government does not wish to see published.170 It has sought to limit the spread of blogs by blocking popular Web sites that offer free publishing tools for blogs.

Iran has the potential to become a world leader in information technology. It has a young, educated, computer-literate population that has quickly taken to the Internet. It is rapidly developing its telecommunications infrastructure. Attempts to restrict Internet usage violate Iran’s obligation to protect freedom of expression and foster popular mistrust of the government.

Access to the Internet

Internet use is soaring in Iran. In 2001, an estimated 250,000 Iranians were online.171 By July 2005, that number had climbed to 6.2 million. The Telecommunication Company of Iran (TCI), a private company the government established to implement the Ministry of Communications and Technology’s policies, estimates that 25 million Iranians will be online by 2009. In July 2005, Iran was home to 683 Internet Service Providers (ISPs).172 The Data Communication Company of Iran (DCCI), a subsidiary of the TCI, is the nation’s most widely used ISP.173

According to one estimate, 1,500 Internet cafés service Tehran alone.174 The TCI has undertaken an ambitious program to extend this service to the countryside. It connected 2,745 villages to the telecommunications network in 2004, bringing the total number of connected villages to 44,741 (of approximately 70,000) by July 2005. Iran is rapidly extending its high-speed fiber-optic cable network, laying 2,768 kilometers of fiber-optic cables in 2004 alone.175 In March 2004, Alcatel, a French telecommunications company, announced it had signed a contract with the private Iranian ISP Asre Danesh Afzar to supply 100,000 broadband, dedicated subscriber lines (DSL) to Iran.176

Legal Constraints on Free Expression

The right to free expression is enshrined in the Iranian constitution and in international human rights treaties ratified by Iran. Article 23 of the Iranian constitution holds that “the investigation of individuals’ beliefs is forbidden, and no one may be molested or taken to task simply for holding a certain belief.”177 Article 24 safeguards press freedoms.178 Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Iran ratified in 1975, states, “Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference,” and that “everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.”179

Iran’s leaders have rhetorically upheld these commitments. Then President Mohammad Khatami, speaking to reporters in December 2003, said Iran was “not censoring criticism. Criticism is OK. Even political Web sites that are openly opposed to the Iranian Government…are available to the Iranian people.”180 Iran’s former minister of information technology, Ahmad Motamedi, added that there was “no punishment defined” for publishing material the government did not agree with.181

In practice, vaguely worded Iranian laws and regulations restrict the exercise of the rights to free expression and to access information. Article 500 of the country’s Penal Code states that “anyone who undertakes any form of propaganda against the state...will be sentenced to between three months and one year in prison,” and leaves “propaganda” undefined.182

Iran’s Press Law of 1986 forbids censorship while at the same time it establishes a broad basis for the harsh punishment of content deemed inappropriate. Article 4 declares that “no government or non-government official should resort to coercive measures against the press…or attempt to censure and control the press.”183 But Article 6 forbids, among other things, publishing material

promoting subjects which might damage the foundation of the Islamic Republic…encouraging and instigating individuals and groups to act against the security, dignity and interests of the Islamic Republic of Iran within or outside the country…or offending the Leader of the Revolution and recognized religious authorities (senior Islamic jurisprudents)…or quoting articles from the deviant press, parties and groups which oppose Islam (inside and outside the country) in such a manner as to propagate such ideas.184

Article 25 of the Press Law further holds writers who “instigate and encourage people to commit crimes against the domestic security or foreign policies of the state” responsible as accomplices to those crimes, “should those actions bear adverse consequences,” and adds, “If no evidence is found of such consequences, [writers] shall be subject to a decision of the religious judge according to Islamic penal code.”185 What comprises a “crime against the domestic security or foreign policies of the state” is left open to interpretation. Likewise, Article 26 continues, “Whoever insults Islam and its sanctities through the press and his/her guilt amounts to apostasy, shall be sentenced as an apostate, and should his/her offense fall short of apostasy he/she shall be subject to the Islamic penal code.”186

Article 27 continues, “Should a publication insult the Leader or Council of Leadership of the Islamic Republic of Iran or senior religious authorities (top Islamic jurisprudents), the license of the publication shall be revoked and its managing director and the writer of the insulting article shall be referred to competent courts for punishment.”187

Under Article 513 of the Penal Code, offences deemed to be an “insult to religion” can be punished by death or imprisonment for up to five years, but “insult” is not defined. Article 698 provides sentences of up to two years in prison or up to seventy-four lashes for those convicted of intentionally creating “anxiety and unease in the public’s mind,” spreading “false rumors,” or writing about “acts which are not true.” Article 609 criminalizes criticism of state officials in connection with carrying out their work, and calls for a punishment of a fine, seventy-four lashes, or between three and six months of imprisonment for such “insults.”188

Such sweeping language violates international free-expression norms. According to the U.N. Human Rights Committee, “When a State party imposes certain restrictions on the exercise of freedom of expression, these may not put in jeopardy the right itself.”189 The Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression in January 2000 urged

all Governments to ensure that press offences are no longer punishable by terms of imprisonment, except in cases involving racist or discriminatory comments or calls to violence. In the case of offences such as “libeling,” “insulting” or “defaming” the head of State and publishing or broadcasting “false” or “alarmist” information, prison terms are both reprehensible and out of proportion to the harm suffered by the victim. In all such cases, imprisonment as punishment for the peaceful expression of an opinion constitutes a serious violation of human rights.190

Encryption

Encryption is illegal in Iran unless users provide the key to the authorities. Article 5.3.8 of the Rules and Regulations for Computer Information Providers, promulgated by Supreme Council for Cultural Revolution, states that usage of any form of encryption “for the purpose of exchanging information requires obtaining the permission of related authorities by registering [the means of encryption’s] specifics, algorithm, and its key, as well as information about the involved parties with the Supreme Council for Cultural Revolution. Otherwise the use of encryption is not allowed.”

Mechanisms of Internet Control

When asked what regulations specifically govern the Internet in Iran, the Iranian government referred Human Rights Watch to a Data Communication Company of Iran (DCCI) Web page.191 According to these regulations, promulgated by the Supreme Council for Cultural Revolution, access service providers (ASPs) “are required to provide filtering systems to prevent access to prohibited immoral and political sites” and to “prevent indirect access through proxy servers.”192

The council’s regulations also stipulate that officers of ISPs

must be Iranian nationals with an allegiance to the Constitution of the Islamic Republic; a member of a faith recognized by the constitution; possess technical skills with the minimum required academic degree and be at least 25 years old; not have immoral reputation or a criminal conviction; not belong to an anti-revolutionary organization or support one (those who have been convicted of acting against internal or external security or are known to be acting against the Islamic Republic cannot be officers of ISPs).193

ISPs are further “legally liable and bound by the following rules and commitments:”

5.3.1. ISPs and their subscribers are responsible for the content they distribute on the network.

Note: 5.3.1. does not apply to providing access to news/information sources. […]

5.3.3. ISPs must implement filtering devices. Filtering standards will be provided by the Council. […]

5.3.5. ISPs are required to record all user information and IP addresses and provide this information to the Ministry of Post and Telegraph. […]

5.3.14. ISPs can only access the Internet through authorized ASPs.194

Regulations targeting ISPs, such as rule 5.3.1, impose a heavy and perhaps technically impossible burden on the data carrier, one that is incompatible with protecting the right to freedom of expression online. Such regulations run counter to the principle of free expression online by imposing a regulatory burden on ISPs that—to the extent that it is even feasible given the nature of data flow online—forces them into the role of censors.

Rule 5.3.5 requires ISPs “to record all user information and IP addresses and provide this information to the Ministry of Post and Telegraph.” Such a disclosure requirement constitutes by its sweeping nature a violation of the right to seek, receive, and impart ideas anonymously.

The Council then enumerates what online activities are prohibited:

6. Production and dissemination of the following by ISPs and their subscribers is prohibited:

6.1. Publishing anti-Islamic material

6.2. Insulting Islam.

6.3. Publishing material that is against the Constitution or which affects the independence of the nation.

6.4. Insulting the leader.

6.5. Insulting religious sanctities, Islamic decrees, values of the Islamic revolution or political ideologies of Imam Khomeini.

6.6. Material that will agitate national unity and harmony.

6.7. Causing public pessimism about the legitimacy and efficacy of the Islamic system.

6.8. Publicizing illegal groups or parties.

6.9. Publication of government documents and material related to national security, the military or the police.

6.10. Publication of obscenity and immoral photographs and images.

6.11. Promoting use of cigarettes or drugs.

6.12. Libel against public officials and insulting real or legal persons.

6.13. Revealing private matters of persons and violating their personal sanctuary.

6.14. Publication of computer and information system passwords or methods to obtain such information.

6.15. Illegal commercial transactions through the Internet such as forgery, embezzlement, gambling, etc.

6.16. Buying, selling or advertising illegal goods.

6.17. Any unauthorized access to sites containing private information and any attempt to crack passwords or secret codes protecting systems.

6.18. Any attack on sites belonging to others for the purpose of disabling or slowing their operation.

6.19. Any attempt to intercept information over networks.

6.20. Creation of radio or television networks without the authorization and supervision of the “Sound and Vision” Organization [Sazeman Seda va Sima, which regulates Iran’s broadcast media].195

The vague language of these provisions, particularly rules 6.1-6.9, drawn as they are from the 1986 Press Law and Penal Code, places unreasonable restrictions on free expression by effectively criminalizing any online criticism of the government.

Under rule 8, these prohibitions apply to Internet cafés and their patrons as well as to ISPs and their clients.196 In May 2001, the government temporarily closed more than 400 Internet cafés in Tehran.197

Detentions

The Group Detentions of August-October 2004

Between August and November 2004, the judiciary, led by Mortazavi in his role as chief prosecutor for Tehran, started a new campaign of arrests of journalists, nongovernmental-organization activists, bloggers, and the technical staff of Web sites specializing in political news. The authorities accompanied this crackdown with increased filtering and blocking of news and information Web sites and blogs inside and outside Iran.

In August 2004, the judiciary blocked the official Web site of the Islamic Revolution Mujahedin Organization, Emrouz (http://www.emrouz.info), and the Islamic Participation Front’s Web site, Rooydad (http://www.rooydadnews.com). Both of these organizations represented reformist political forces with close ties to then President Khatami’s government.

On August 5, 2004, security forces detained Asghar Vatankhah, who was in charge of advertising on the Emrouz Web site. Three days later the authorities arrested a member of Emrouz’s technical staff, Masood Ghoreishi, who uploaded pages to the site.

The authorities detained contributing journalists and technical staff rather than high-profile political leaders under whose names these Web sites operate. On August 15, Mohsen Armin, a spokesman for the Islamic Revolution Mujahedin Organization, expressed that group’s concern regarding these arrests:

Two people working for the Emrouz Web site were detained by unknown officials and our information indicates that the motivation behind these arrests is to gain information about Emrouz Web site. Following these detentions, agents apparently operating under the authority of Tehran chief prosecutor searched the homes of the detainees and confiscated their personal computers and CDs. Ever since the filtering of Emrouz Web site, we have explicitly protested this action and have said that we are responsible for its operation. If the authorities claim to have uncovered conspiracy towards a coup, spying, or overthrowing the state, why do they not directly approach the management of the site instead of detaining its technical staff?198

On August 22, 2004, the judiciary detained six members of Rooydad’s technical staff¾Farid Sani, Arash Naderpour, Mani Javadi, Kiavash Ghadmeli, Mozhgan Ghavidel, and Mehdi Derayati.

All were held in secret detention centers, without access to visits by their families and lawyers. The individuals detained from both the Emrouz and Rooydad Web sites were involved in providing technical assistance sites and played no role in deciding their content and postings.

During the next two months, the judiciary targeted online journalists, bloggers, and non-governmental organization (NGO) activists who used online media to express their views and arrested eight more people:

Authorities held all of the detainees in solitary confinement in a secret detention center. Judiciary officials gave differing reasons for these arrests. On October 12, 2004, Jamal Karimi Rad, the judiciary’s spokesman, said that the detainees were accused of “propaganda against the regime, endangering national security, inciting public unrest, and insulting sacred belief.” The head of the judiciary, Ayatollah Mahmud Hashemi Shahrudi, in an October 27, 2004, interview with state-run television, stated that “these people will be tried in connection with moral crimes.”

The government released the detainees on bail in November and December 2004 without any charges formally filed against them. Interrogators forced four of the detainees—Omid Memarian, Ruzbeh Mir Ebrahimi, Shahram Rafihzadeh, and Javad Gholam Tamayomi—to write false confession letters as a condition for their release.200

In a December 11 public letter to then-President Mohammed Khatami, the father of one of those detained, Ali Mazroi—who is also president of the Association of Iranian Journalists and a former member of parliament—implicated the judiciary in the torture and secret detention of the detainees. In his letter, Mazroi wrote:

Immediately after entering the prison, the interrogator blindfolded Hanif and began interrogations. The first question posed by the interrogator was “to write down all your immoral activities and corruptions.” Hanif asked the interrogator what the charges against him were. In return, the interrogator screamed at him to answer the question. Hanif said “I do not have any moral corruptions.” The interrogator beat him and posed similar questions. Then, the interrogator told Hanif that according to confessions made by Derayati [another detainee], Hanif was the technical chief of the Rooydad Web site and asked Hanif to explain his activities in this regard…. The interrogation continued for nearly five days and encompassed moral corruption, illegitimate personal relationships, and even the most intimate details of family issues…. During sixty-six days of detention, Hanif spent fifty-nine days in a solitary cell with approximate dimensions of two meters by one-and-a-half meters. The only times he left his cell were for interrogations or to use a bathroom (three times daily, each time for only three minutes). The interrogator beat him on numerous occasions and applied sever pressure. … The judiciary officials never told us of the location of this prison. According to various sources, this prison is illegal and it is operated outside the supervision of the Prison Bureau. The other detainees suffered similar ill-treatment.201

Immediately afterward, Chief Prosecutor Mortazavi filed libel charges against

Mazroi. On December 11, Mortazavi ordered the detention of three of the

released detainees—Omid Memarian, Shahram Rafihzadeh and Ruzbeh Mir Ebrahimi—as

witnesses for the prosecution in the case. These three and Javad Gholam

Tamayomi, a journalist who has been in detention since October 18, were brought

to Mortazavi’s office. Mortazavi threatened the four with lengthy prison

sentences if they did not deny Mazroi’s allegations. They were interrogated for

three consecutive days for eight hours each day.

On December 14, the four detainees were brought in front of a televised “press

conference” arranged by Mortazavi. That evening, government-controlled

television news broadcast videotapes that showed the four saying that their

jailors treated them as “gently as flowers.”202

The detainees had been kept at a secret location one hour

outside of central Tehran, where they were held in solitary confinement in

small cells for up to three months. During the entire length of their detention

they were subjected to torture—including beatings with electrical cables—and

interrogations that lasted up to eleven hours at a stretch.

Authorities denied the detainees access to lawyers and to medical care when

they fell ill, and rarely permitted family visits. Interrogators often

threatened detainees with the arrest of family members and friends if they did

not cooperate. Their mental stress had reached such a level that many detainees

had reportedly become suicidal. The apparent purpose of this treatment

was to extract confessions that would implicate reformist politicians and civil

society activists in activities such as spying and violating national security

laws.

On December 25, Hanif Mazroi, Massoud Ghoreishi, Fereshteh

Ghazi, Arash Naderpour and Mahbobeh Abasgholizadeh—all of them detained

journalists—testified about their detention before the presidential commission

tasked with investigating detention and ill-treatment of detainees. Fereshteh

Ghazi detailed her treatment, including severe beatings that resulted in a

broken nose during one interrogation session. This information became public

after a member of the presidential commission, Mohammad Ali Abtahi, published

these testimonies in his blog.203

On January 1, two other former detainees, Omid Memarian and Ruzbeh Mir

Ebrahimi, also appeared in front of the commission, where they confirmed

details of their torture and renounced the contents of their confession

letters.

After their appearances before the presidential commission, Chief Prosecutor

Mortazavi threatened each with lengthy prison sentences and harm to their

family members as punishment for their testimony. Mortazavi continued to issue

subpoenas for the journalists without specifying charges. His operatives also

harassed the journalists with daily phone calls.204

On January 12, 2005, the head of the judiciary, Ayatollah Mahmud Hashemi Shahrudi, ordered the formation of an internal investigating committee to probe bloggers’ claims of torture and ill-treatment. At a press conference on March 29, judiciary spokesperson Jamal Karimirad said that its findings had been presented to Ayatollah Shahrudi and that a final report would be made public shortly. The report was never made public.205 As a result of the investigation, Karimarad said on April 20, all detainees had been cleared of any wrongdoing except the four online journalists and bloggers who wrote “confession letters”—Omid Memarian, Shahram Rafihzadeh, Ruzbeh Mir Ebrahimi, and Javad Gholam Tamayomi. But the judiciary’s investigation failed to hold anyone in the judiciary or security forces responsible for illegal detentions, torture, and ill-treatment of detainees.

On August 13, the judiciary formally indicted the four online journalists and bloggers and said that their trial would be held soon.206 Chief of the Tehran judiciary Abasali Alizadeh did not specify on what grounds the bloggers were being indicted.

Sina Motalebi

On December 1, 2002, journalist Sina Motalebi posted an article on his blog about the trial of Hashem Aghajari, a university professor who was sentenced to death in November 2002 after he criticized aspects of Iran’s clerical rule.207 Between January and April 2003, judiciary officials summoned Motalebi numerous times. Motalebi told Human Rights Watch that he was repeatedly interrogated about his postings advocating the cause of detained and imprisoned writers. The judiciary agents told him that his postings amounted to “disturbing the public opinion” and “propaganda against the judiciary.”208

On the evening of April 19, 2003, judiciary agents contacted Motalebi and told him he should report to their offices the next morning. On the morning of April 20, Motalebi presented himself at Imam Khomeini Judicial Complex in Tehran, where he was promptly detained on the order of Judge Jafar Saberi Zafarghandi.

Judiciary agents detained Motalebi in a secret location in solitary confinement in a small room. He was repeatedly interrogated regarding his postings on his blog and accused of “acting against national security.” His interrogator asked him to “list all illegitimate and illegal activities that you have ever committed including all your communications and connections with counter-revolutionary forces abroad.”209

Though no charges had been brought against him, the judiciary released Motalebi on May 12, 2003, only after he posted bail in amount of 300 million rials (U.S. $37,500). Officials continued to harass him. In November 2003, after Shirin Ebadi had won the Noble Peace prize, judiciary agents summoned and interrogated Motalebi regarding a congratulatory letter to Ebadi that he had signed; they also continued to threaten harm to his family.210

In December 2003, Motalebi left for Europe where he sought asylum. In June 2004, he recalled his experiences at a joint press conference held by Human Rights Watch and Reporters sans frontières. The judiciary responded by arresting his father, Saeed Motalebi. On September 8, 2004, judiciary agents arrested Saeed Motalebi and charged him with “assisting the escape of an accused person,” an apparent reference to his son’s departure from Iran, despite the fact that Sina Motalebi left Iran legally.211 Saeed Motalebi was detained for 10 days in a secret detention center before being released. His trial, held on November 15, 2004, has not yet produced a verdict.212

Mojtaba Lotfi

Mojtaba Lotfi, a student of Islamic jurisprudence in Qom, might seem an unlikely candidate to be imprisoned for his online journalism. But Lotfi is a member of the editorial board of the news Web site http://www.naqshineh.com, which the government of Iran has blocked since March 2004 on the orders of the Qom authorities.213He had previously written for the reformist newspaper Khordad, which authorities closed in 1999.

Lotfi was detained in May 2004 after posting an article on http://www.naqshineh.com headlined “Respect for Human Rights in Cases Involving the Clergy.”He was released two-and-a-half months later after posting 650 million rials ($81,250) bail.214 During his detention, he was held in solitary confinement for twenty days and was not allowed to meet with his family or lawyer.215

On August 14, 2004, the Special Court for the Clergy in Qom sentenced Lotfi to forty-six months in prison on charges of “disseminating lies,” “activities against the government,” and “revealing state secrets.”216 He appealed, but on February 5, 2005, an appeals court upheld the sentence, and he was imprisoned.217

On August 28, 2005, after six months in prison, Lotfi was granted a three-day furlough to attend a religious festival with his family. At the end of the three days, he received a call saying he need not return to prison. His health, already poor from having been gassed in the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, had reportedly deteriorated while he was in prison.218

Mohammad Reza Nasab Abdullahi

On February 23, 2005, following a closed-door trial held without his lawyer, Mohammad Reza Nasab Abdullahi was sentenced to six months in prison on appeal for insulting the Supreme Leader and spreading anti-government propaganda. He was imprisoned five days later. Abdullahi, a university student, human rights activist, editor of a student newspaper, and blogger in the central Iranian city of Kerman, served six months in an Iranian prison for posting an entry on his blog, Webnegar (“Web writer”) at http://www.iranreform.persianblog.com. The offending post, titled “I Want to Know,” was addressed to the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei and criticized the government’s repression of “civil and personal rights and liberties.”219

On March 2, Abdullahi’s wife, 26-year-old university student Najmeh Oumidparvar, was arrested in her home. She had posted messages from her husband on her own blog, http://www.faryadebeseda.persianblog.com. On the eve of her arrest, she had given an interview to the German radio station Deutsche Welle. She was four months pregnant. After twenty-four days in custody, Oumidparvar was freed on bail.220

Mojtaba Saminejad

In October 2004, Mojtaba Saminejad was a 25-year-old Tehran journalism student who maintained the popular blog, http://www.man-namanam.blogspot.com. On October 31, 2004, after Saminejad reported the arrests of three other bloggers, judiciary agents arrested him and held him in solitary confinement for eighty-eight days. The government released Saminejad on January 27, 2005, after setting bail for 500 million rials ($62,500).221

Soon after his release, Saminejad started a new blog called Stijeh, at http://www.8MDR8.blogspot.com. Judiciary agents detained him again on February 12, 2005, and his bail was tripled to 1.5 billion Rials ($187,500)—a price too exorbitant for his family to pay.222

On May 16, 2005, Saminejad wrote a letter to the chief justice of the Islamic Revolutionary Court saying that he had spent three months in solitary confinement under intense pressure, and requesting to be released.223 On May 20, he faced trial behind closed doors.224 According to his lawyer, Mohammad Seifzadeh, Saminejad was charged with: “insulting Imam Khomeini and the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamanei;” “acting against national security by disseminating rumors and lies;” “insulting the sacred tenets of Islam;” “disturbing public opinion by publishing untrue statements;” and engaging in “illegitimate relationships and encouraging vice and immoral activities.” Lawyer Seifzadeh said that the last charge concerned a photograph taken of Saminejad and his classmates while they were on a hiking trip.

On June 7, 2005, Saminejad was sentenced to two years in prison for “insulting Imam Khomeini and the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei.” Although he was cleared of the other four charges against him, the judge found that he would have to stand trial for the more serious charge of “insulting the Prophet and his family.” Saminejad was charged with apostasy, a capital offense under article 512 of the Penal Code .225 He was acquitted of this last charge on June 21, but remains in Rajaii Shahr prison amid housed with violent criminals.226

Arash Sigarchi

Arash Sigarchi, former editor of the daily Gilan Emrouz, maintains a blog called Panjareh Eltehab (“Window of Anguish”) from his home in the northern city of Rasht.227 His online writings were often critical of the government and he frequently protested the detention of other Iranian bloggers. On January 16, 2005, days after he had given interviews to BBC World Service and the U.S.-based Radio Farda, he was summoned to court and interrogated. The next day, agents of the Ministry of Intelligence arrested him.228

On February 2, the revolutionary court in the northern province of Gilan sentenced Sigarchi to fourteen years in prison, but made its ruling public only on February 22. Charges included espionage, “aiding and abating hostile governments and opposition groups” by giving interviews to the U.S.-based Radio Farda, endangering national security, and “insulting Imam Khomeini and the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei.” The court based its decision on a report by the Intelligence Ministry agents who arrested Sigarchi.

Sigarchi’s trial violated international standards for fair trials. It was held behind closed doors and in the absence of his lawyer—indeed, he was not allowed to meet with his lawyer for months after his arrest.

Sigarchi’s lawyer, Mohammad Saifzadeh, told Human Rights Watch that his client’s summons, arrest, and the search and seizure of his personal documents were marked by numerous irregularities and illegal actions. Authorities released him on March 16, 2005, after he posted 1 billion rials ($125,000) in bail. He has appealed his conviction.229

After his release, Sigarchi told reporters that the only evidence presented against him was

a few selected postings from my blog, selected transcripts of my interviews with Radio Farda reporters, and a few of my journalistic writings… During the trial, I did not have the right to a lawyer. The judge and the court officer explicitly told me there was no need. They encouraged me not to hire a lawyer so my problem could be resolved more easily. But after they issued my sentence, I asked my brother to hire a lawyer.230

Thereafter, Sigarchi was represented by three prominent Iranian human rights lawyers: Shirin Ebadi, Parviz Jahangard, and Mohammad Seifzadeh.

At his June 9, 2005, appeal hearing, Sigarchi’s lawyers rejected all the charges against him and argued that the lower court’s decision was illegal and unsupported by any evidence. The appeals court has yet to issue its ruling.231

Censorship

Over the course of September 2005, researchers from Human Rights Watch and the Open Net Initiative (ONI), assisted by Iranian bloggers, tested 3,146 Web sites from Iran. Using the methodology described in the introduction to this report and in ONI’s other reports on Internet censorship around the world, researchers tested four categories of sites:

- A list of “high impact” sites reported to be blocked or likely to be blocked in Iran because to their content;

- A “global,” or control list of sites reflecting a range of Internet content, (including, for example, major news sites and sites about “hacking”);

- A list of Iranian blogs;

- Previous tests indicated that Web site filtering in Iran was likely accomplished by software called SmartFilter, produced by the U.S.-based Secure Computing. Secure Computing did not dispute these results at the time, but denied having sold the software to Iran.232 A fourth list, comprised of sites known to be blocked by this software, was included in this round of testing in order to test whether the government was still using SmartFilter to block Web sites.

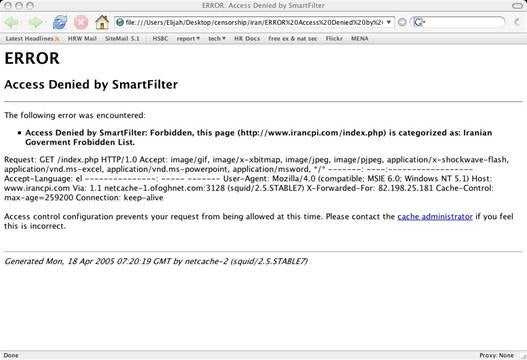

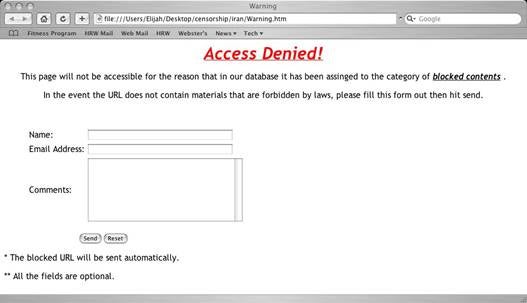

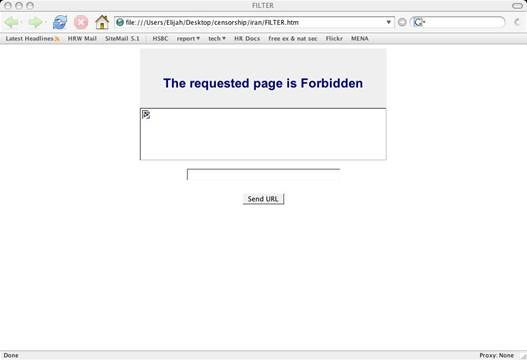

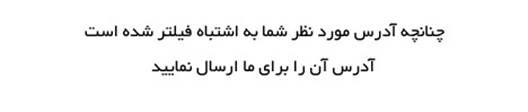

In Iran, attempts to navigate to a blocked Web site immediately return a page saying that access to the site is “forbidden” or “denied.” The page varies depending on the ISP used. A few samples, sent to Human Rights Watch by Iranian Internet users, follow:

The second example above strongly suggests that Iranian ISPs continue to use SmartFilter to block Web sites.

In mid-October 2005, researchers tested 3,146 sites from a location within Iran connected to the Internet via TCI, the country’s most popular ISP. Of the 3,146 sites tested, 718 were found to be blocked.

Researchers tested 643 Iranian blogs and found 129 blocked. Twelve were inaccessible for other reasons. Researchers further compiled a list of fifty-four Web sites associated with opposition political groups. Of these, twenty-one were blocked. Of the forty Web sites researchers tested that offer anonymous, unfiltered web browsing via a proxy server outside Iran, sixteen were confirmed blocked. Commercial Web sites featuring sexual material or dating services were extensively blocked.

Among the sites blocked for their political content were:

- http://www.womeniniran.net, a Web site dedicated to women’s rights, and to social, economic, and political issues pertaining to women in Iran.

- http://www.iftribune.com, the Web site of the Women’s Cultural Center, an independent and non-governmental organization in Tehran.

- http://www.womeniw.com, an Iran-based Web site dedicated to combating all forms of discrimination, but particularly discrimination against women.

- http://www.irwomen.com, the Web site of the Iranian Women’s Center, which provides news and analysis on issues of particular interest to women from a cultural and literary perspective.

- http://www.radiofarda.com, the Web site of Radio Farda, a Farsi station produced by Voice of America.

- http://www.nitv.tv, the Web site of the U.S.-based National Iranian TV, which broadcasts into Iran via satellite.

- http://www.rooydad.com, a Farsi-language news site that provides news, opinion, and commentary about the Iranian government with a reformist slant and provides links to other reformist sites.

- http://www.iranvajahan.net, a London-based monarchist Web site.

- http://www.iranian.com, a U.S.-based site operated by and for expatriate Iranians.

- http://www.iran-emrooz.de/, a Farsi-language, online political magazine that publishes articles by Iranian reformists and dissidents.

- http://www.peiknet.com, a Farsi-language news and opinion site that frequently publishes critical articles about the government.

- http://www.roshangari.com/, which features news, opinion, and commentary in Farsi and English from a reformist angle.

- http://www.kayhanlondon.com/, the online version of Kayhan London, a newspaper published by Iranian exiles. It is not related to the Kayhan published in Iran.

- http://www.hoder.com/, http://www.editormyself.com/, and http://sobhaneh.org/, Popular political blogs run by Hossein Derakhshan, a Toronto-based Iranian blogger and online free-expression activist. They are available in English and Farsi. Derakhshan was among the first Farsi-language bloggers and is credited with first adapting blogging software to support Farsi easily.

- http://z8un.com/, another popular Farsi-language blog that covers politics and social issues, it has been online since 2002.

- http://www.zananeha.com/, a Farsi-language, feminist blog that frequently criticizes the government.

- http://www.cappuccinomag.com/, an online news and opinion magazine covering politics, society, arts, and entertainment.

- http://mithras.org/, a political blog that has reported news of political arrests and executions.

- http://www.rezapahlavi.org, the official site of Reza Pahlavi, the son of the late shah.

- http://www.farahpahlavi.org, the official Web site of Farah Pahlavi, former Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s widow.

- http://www.pdk-iran.org/, the Web site of the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan.

- http://www.nehzateazadi.org, the official site of the Freedom Movement Party, whose members have been jailed and disqualified from running in elections.

- http://www.montazeri.com, a Web site promoting views of Ayatollah Hussein Ali Montazeri, a grand ayatollah who ran afoul of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini prior to the latter’s death in 1988, and who has been under house arrest since 1997 for criticizing unaccountable rule of the Supreme Leader. http://www.montazeri.net was also blocked, though http://www.montazeri.ws was not.

- http://www.mellimazhabi.org, the official site of Melli-Mazhabi opposition party, the members of which have been subject to harassment and arrest in Iran.

- http://www.marzeporgohar.org, the Web site of the Marze Por Gohar Party, which describes itself as “for a secular Iran.” The group was active in the 1999 student demonstrations.

- http://www.komala.org, the Web site of the Komala Party, a banned Iranian Kurdish political party.

- http://forouharha.com, a Web site dedicated to Parvaneh and Dariush Forouhar, prominent opposition figures who were killed in their home by Iranian Intelligence officers on November 22, 1998.

- http://akbarganji.net, dedicated to Akbar Ganji, a high-profile Iranian investigative journalist who has been in prison since April 22, 2000, following his arrest for participating in a conference in Berlin. Ganji has gone on prolonged hunger strikes several times to protest his treatment in prison.

- http://www.alijavadi.com/, http://www.wpiran.org/, http://www.tudehpartyiran.org/default.asp, http://www.toufan.org/, http://www.kargar.org/, http://www.fadai.org/, http://www.iransocialforum.org/, Web sites of Iranian Leftist groups, politicians, and political parties.

- http://www.banisadr.com.fr/, the official site of Abolhassan Banisadr, Iran’s first president after the 1979 revolution. He has become an opposition figure and lives in France. He publishes articles criticizing the Iranian government.

- http://www.entezam.org/, a Web site dedicated to Abbas Amir Entezam, the longest-serving political prisoner in Iran. Entezam was deputy prime minister and government spokesman of Iran’s provisional government after the revolution in 1979.

- http://www.iran-e-sabz.org/, the official site of the Green Party of Iran. The Green Party of Iran is a political party founded to defend Iran’s environment and to advocate for “political, economical, social, and cultural freedom.”

- http://www.jebhemelli.net/, one of many sites belonging to the Iranian National Front Party (INFP). The INFP “strives to establish a democratic system based on the will of the Iranian people,” and seeks to “establish individual liberties and social freedoms.”

- http://www.kurdistanmedia.com/, the Web site of the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan. The site provides news, information, opinion, and commentary about Iran and its Kurdish population.

- http://iranncr.org, a Web site of the armed Iranian resistance group the Mojahedin Khalq Organization (MKO), also known as the National Council of Resistance of Iran. Iranian Internet users reported that the organization’s other Web sites are also blocked.

- http://reference.bahai.org/fa, a Persian-language Web site dedicated to the teachings of the Baha’i faith.

- http://www.irantestimony.com, which presents human rights news from Iran and collects testimony from victims of human rights abuses.

It should be noted that these results constitute a “snapshot” of the Iranian Internet in October 2005. Sites reported blocked at the time of our testing may no longer be blocked. Likewise, sites that were available during our tests may no longer be available.

Conclusion

Iran is experiencing a boom in Internet use. This, in turn, has opened a new space for ordinary Iranians to express themselves and to transmit and receive information. But repressive legislation and regulations and a rash of detentions of online writers amount to what the Open Net Initiative has called “one of the world’s most substantial Internet censorship regimes.”233

To comply with its obligations to protect free expression under Iran’s constitution and international human rights treaties it has signed, the Iranian government should:

- Access: Continue investing in improving Iran’s Internet infrastructure. The explosion in self-expression the blogging phenomenon has heralded in Iran would not have been possible without the underlying infrastructure that allows the Internet to operate.

- Detentions: Release Mojtaba Saminejad immediately and unconditionally, and appoint an independent commission to investigate those responsible for the extensive illegal detention of journalists and online writers over the course of 2004-2005, and to recommend appropriate penalties for those responsible for these illegal detentions within the framework of Iranian law and international human rights standards.

- Censorship: The Iranian government should cease blocking Web sites that carry material protected by the rights to free expression and free information, including, but not limited to: http://www.womeniniran.net, http://www.iftribune.com, http://www.womeniw.com, http://www.irwomen.com, http://www.radiofarda.com, http://www.nitv.tv, http://www.rooydad.com, http://www.iranvajahan.net, http://www.iranian.com, http://www.iran-emrooz.de/, http://www.peiknet.com, http://www.roshangari.com/, http://www.kayhanlondon.com/, http://www.hoder.com/, http://www.editormyself.com/, and http://sobhaneh.org/, http://z8un.com/, http://www.zananeha.com/, http://www.cappuccinomag.com/, http://mithras.org/, http://www.rezapahlavi.org, http://www.farahpahlavi.org, http://www.pdk-iran.org/, http://www.nehzateazadi.org, http://www.montazeri.com, http://www.montazeri.net, http://www.mellimazhabi.org, http://www.marzeporgohar.org, http://www.komala.org, http://forouharha.com, http://akbarganji.net, http://www.alijavadi.com/, http://www.wpiran.org/, http://www.tudehpartyiran.org/default.asp, http://www.toufan.org/, http://www.kargar.org/, http://www.fadai.org/, http://www.iransocialforum.org/, http://www.banisadr.com.fr/, http://www.entezam.org/, http://www.iran-e-sabz.org/, http://www.jebhemelli.net/, http://www.kurdistanmedia.com/, http://iranncr.org, http://reference.bahai.org/fa, http://www.irantestimony.com

- Laws and Regulations: The Iranian government should strike rules 6.1 through 6.7 and 6.20 of the DCCI’s regulations for Internet use in Iran. Prohibitions against “publishing anti-Islamic material,” “Insulting the Leader,” publishing “material that will agitate national unity and harmony,” or “causing public pessimism about the legitimacy and efficacy of the Islamic system” serve to criminalize the peaceful exercise of the right to free expression. The Iranian government should seek to pass legislation that provides strict guarantees of the privacy of electronic communications. It should further seek to pass new laws that affirmatively protect the right to freely access or disseminate information or opinions and clarify the narrow circumstances in which government interference would be warranted according to international standards.

[163] Aaron Scullion, “Iran’s President Defends Web Control,” BBC News, December 12, 2003, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/3312841.stm, accessed September 20, 2005.

[164] Iranian Blogger Hossein Derakhshan, address to the “Voices, Bits, and Bytes” conference at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard Law School, December 10, 2004.

[165] Study conducted by the National Institute for Technology and Liberal Education, http://www.blogcensus.net/?page=lang, accessed September 20, 2005. While many of the blogs may have been located outside Iran, the vast majority of Farsi-speakers live in Iran.

[166] Iranian Student News Agency, http://www.isna.co.ir/news/NewsCont.asp?id=427457&lang=P, accessed September 21, 2005 (in Farsi).

[167] Reporters sans frontières, Internet Under Surveillance, 2004: Iran, http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=10733&Valider=OK, accessed September 20, 2005. (As of October 2005, it was available under a new address: http://www.webneveshteha.com).

[168] See http://www.khamenei.ir/EN/home.jsp.

[169] Human Rights Watch, Like the Dead in Their Coffins—Torture, Detention, and the Crushing of Dissent in Iran, June 2004.

[170] Former President Khatami quoted in Aaron Scullion, “Iran’s President Defends Web Control.”

[171] Nazila Fathi, “Iran Jails More Journalists and Blocks Web Sites,” The New York Times, November 8, 2004.

[172] Telecommunication Company of Iran, 2005, July 2005, http://www.tci.ir/eng.asp?page=22&code=1&sm=0, accessed September 21, 2005. By comparison, Egypt, a country with a larger population, has only 4 million Internet users and fewer than 200 ISPs.

[173] Press freedom advocates have alleged that the DCCI is under the control of the Intelligence Ministry. See Reporters sans frontières, The Internet Under Surveillance, 2004: Iran, http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=10733&Valider=OK, accessed September 21, 2005.

[174] Luke Thomas, “Rise of the Internet as a Political Force in Iran,” Persian Journal, March 19, 2004, http://www.iranian.ws/cgi-bin/iran_news/exec/view.cgi/2/1772/printer, accessed September 20, 2005.

[175] On the number of connected villages and the extension of fiber-optic cables in Iran: Telecommunications Company of Iran, 2005; on the number of villages and small villages in Iran: Houmam Habibi Parsa, “Country Paper: Islamic Republic of Iran,” Non-Farm Employment Opportunities in Rural Areas in Asia, 2004, http://www.apo-tokyo.org/00e-books/AG-05_Non-FarmEmployment/11Iran_Non-Farm.pdf

[176] Alacatel press release, March 23, 2004, http://www.home.alcatel.com/vpr/vpr.nsf/DateKey/23032004uk, accessed September 21, 2005.

[177] Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran, article 23, op. cit.

[178] “Publications and the press have freedom of expression except when it is detrimental to the fundamental principles of Islam or the rights of the public. The details of this exception will be specified by law,” Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran, article 24.

[179] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), G.A. res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force Mar. 23, 1976, article 19, http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/a_ccpr.htm, accessed September 3, 2005.

[180] Aaron Scullion, “Iran’s President Defends Web Control.”

[181] Ibid.

[182]Amnesty International, Iran: A Legal System That Fails to Protect Freedom of Expression and Association, December 21, 2001, http://web.amnesty.org/library/index/engMDE130452001?Open, accessed September 21, 2005.

[183] Iranian Press Law, ratified March 19, 1986, article 4. English translation available at http://www.netiran.com/?fn=law14, accessed September 21, 2005. For a fuller discussion of the Press Law, see Human Rights Watch, As Fragile as a Crystal Glass: Press Freedom in Iran, October 12, 1999, http://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/iran/; Middle East Watch (Now Human Rights Watch/Middle East and North Africa), Guardians of Thought, (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1993), pp. 24-26.

[184] Press Law, article 6.

[185] Press Law of 1986, article 25.

[186] Press Law of 1986, article 26.

[187] Press Law of 1986, article 27.

[188] Quoted in Amnesty International, Iran: A Legal System.

[189] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, CCPR General Comment 10: Freedom of Expression (Art. 19): June 29, 1983, http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/0/2bb2f14bf558182ac12563ed0048df17?Opendocument, accessed September 21, 2005.

[190] Annual Report to the UN Commission on Human Rights, Promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, UN Doc. E/CN.4/2000/63, para. 205.

[191] http://www.dci.ir/data4.asp, accessed October 20, 2005.

[192] Supreme Council for Cultural Revolution, “Rules and Regulations for Computer Information Providers,” translated by Human Rights Watch from the Web site of the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology—Data Communications Company of Iran, http://www.dci.ir/data4.asp; on requirement to provide filtering systems: Article A, Item 6a.; on preventing indirect access through proxy servers: The Council is chaired by the president but dominated by clerics.

[193] Ibid., Article B, Items 5.2.1 - 5.2.5.

[194] Ibid., Article B, Items, 5.3.1 – 5.3.14.

[195] Ibid., Article B, Items 6.1-6.20.

[196] Ibid., Article B, Item 8.

[197] Reporters sans frontières, “400 Cybercafés Closed,” May 14, 2001, http://www.rsf.org/rsf/uk/html/mo/cplp01/lp01/140501.html, accessed September 21, 2005. The cafes were allowed to re-open in June 2001.

[198] Iranian Students News Agency, “Islamic Revolution Mujahedin Organization Alarmed over Detention of Two Employees,” August 15, 2004, http://www.isna.ir/Main/NewsView.aspx?ID=News-416932 (in Farsi).

[199] Human Rights Watch, “Iran: Web Writers Purge Underway,” November 8, 2004, http://hrw.org/english/docs/2004/11/08/iran9631.htm.

[200] Human Rights Watch, “Iran: Judiciary Should Admit Blogger Abuse,’” April 5, 2005, http://hrw.org/english/docs/2005/04/04/iran10415.htm.

[201] Ali Mazroi’s Letter to the President, December 12, 2004, http://news.gooya.com/politics/archives/020270.php, accessed October 20, 2005 (in Farsi).

[202] Human Rights Watch, “Iran: Judiciary Uses Coercion to Cover Up Torture,” December 20, 2004, http://hrw.org/english/docs/2004/12/17/iran9913.htm.

[203] http://www.webneveshtha.com/weblog/?id=1249214259, accessed October 20, 2005 (in Farsi).

[204] Human Rights Watch, “Iran: Journalists Receive Death Threats After Testifying,” January 6, 2005. http://hrw.org/english/docs/2005/01/06/iran9948.htm.

[205] Iranian Students News Agency, “Bloggers Cleared, Except Four,” April, 20, 2005, http://www.isna.ir/Main/NewsView.aspx?ID=News-516865 (in Farsi).

[206] Iranian Students News Agency, “Bloggers’ court hearing to be held soon,” August 13, 2005. http://www.isna.ir/Main/NewsView.aspx?ID=News-569237, accessed October 20, 2005 (in Farsi).

[207] http://www.rooznegar.com

[208] Human Rights Watch Interview with Sina Motalebi, June 8, 2004.

[209] Ibid.

[210] Ibid.

[211] Iranian Labor News Agency, “Sina Motalebi’s Father in Court,” November, 9, 2004, http://www.ilna.ir/shownews.asp?code=146389&code1=1 (in Farsi).

[212] Iranian Labor News Agency, “Saeed Motalebi’s Trial Is Held,” November, 16, 2004 (in Farsi).

[213] Reporters sans frontières, “Appeals Court Confirms Prison for Cyber-Dissident While Blogger Is Re-Imprisoned,” February 15, 2005, http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=12564, accessed September 21, 2005.

[214] Iranian Labor News Agency, “Editorial Board Member of Naqshineh Site Is Sentenced to 46 Months in Prison,” August 14, 2004, http://www.ilna.ir/shownews.asp?code=119316&code1=1 (in Farsi).

[215] Iranian Labor News Agency, “Editorial Board Member,” and Reporters sans frontières, “Appeals Court Confirms Prison for Cyber-Dissident While Blogger Is Re-Imprisoned,” February 15, 2005, http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=12564, accessed September 21, 2005.

[216] Iranian Labor News Agency, “Editorial Board Member.”

[217] Reporters sans frontières, “Appeals Court Confirms Prison for Cyber-Dissident While Blogger Is Re-Imprisoned,” February 15, 2005, http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=12564, accessed September 21, 2005.

[218] Reporters sans frontières, “Release of Cyberjournalist Mojtaba Lotfi and Blogger Mohamad Reza Nasab Abdolahi,” August 29, 2005, http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=14807, accessed September 21, 2005.

[219] For the full text of the blog post, as translated by Human Rights Watch, see http://www.hrw.org/campaigns/internet/iran/nasb.htm.

[220] Reporters sans frontières, “Pregnant Blogger Najmeh Oumidparvar Freed After 24 Days in Prison,” March 29, 2005, http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=12655, accessed September 21, 2005.

[221] Iranian Student News Agency, “Another Blogger, Mojtaba Saminejad, Is Released,” January 28, 2005, http://www.isna.ir/Main/NewsView.aspx?ID=News-487342 (in Farsi).

[222] “Latest News Regarding Saminejad’s Situation,” Hatef News, http://www.hatefnews.com/, May 16, 2005 (in Farsi).

[223] Iranian Student News Agency, “Saminejad Asks to be Released in Letter to the Chief of the Islamic Revolutionary Court,” May 16, 2005, http://www.isna.ir/Main/NewsView.aspx?ID=News-527664 (in Farsi).

[224] Iranian Labor News Agency, “Saminejad’s Trial Held Behind Closed Doors,” May 20, 2005, http://www.ilna.ir/shownews.asp?code=208417&code1=1 (in Farsi).

[225] BBC Persian, “Iranian Blogger Sentenced to Two Years,” June 7, 2005, http://www.bbc.co.uk/persian/iran/story/2005/06/050606_sm-madyar.shtml (in Farsi).

[226] Iranian Labor News Agency, “Saminejad’s Lawyer: The Court, Instead of Freeing Saminajed, Reduced His Bail by 20 Million Toman,” July 12, 2005 (in Farsi).

[227] http://www.sigarchi.com/blog.

[228] Iranian Students News Agency, “Arash Sigarchi, Editor of Gilan Emrouz, Summoned to Court,” January 16, 2005, http://news.gooya.com/politics/archives/022220.php, accessed January 16, 2005 (in Farsi).

[229] BBC Persian, “Arash Sigarchi released,” March 17, 2005 (in Farsi).

[230] Azadi Bayan interview with Arash Sigarchi, http://mag.gooya.com/politics/archives/025449.php (in Farsi).

[231] Iranian Students News Agency, “Sigarchi’s Appeals Court Trial Held on Thursday,” June 10, 2005, http://www.isna.ir/Main/NewsView.aspx?ID=News-538922 (in Farsi).

[232] "Secure Computing has sold no licenses to any entity in Iran, and any use of Secure's software by an ISP in Iran has been without Secure Computing's consent and is in violation of Secure Computing's End User License Agreement. We have been made aware of ISPs in Iran making illegal and unauthorized attempts to use of our software. Secure Computing is actively taking steps to stop this illegal use of our products. Secure Computing Corporation is fully committed to complying with the export laws, policies and regulations of the United States. It is Secure Computing's policy that strict compliance with all laws and regulations concerning the export and re-export of our products and/or technical information is required. Unless authorized by the U.S. Government, Secure Computing Corporation prohibits export and reexport of Secure products, software, services, and technology to Iran and destinations subject to U.S. embargoes or trade sanctions." Statement of Secure Computing Chief Executive Officer John McNulty, issued June 22, 2005 and cited in, “Country Study: Internet Filtering in Iran, 2004-2005,” OpenNet Initiative, June 21, 2005, http://www.opennetinitiative.net/studies/iran/ONI_Country_Study_Iran.pdf.

[233] Open Net Initiative, Country Study: Internet Filtering in Iran, 2004-2005, June 21, 2005, http://www.opennetinitiative.net/studies/iran/ONI_Country_Study_Iran.pdf.

| <<previous | index | next>> | November 2005 |