<<previous | index | next>>

IV. How Multinational Internet Companies assist Government Censorship in China

1. Yahoo! Inc.

“Our mission is to be the most essential global Internet service for consumers and businesses. How we pursue that mission is influenced by a set of core values - the standards that guide interactions with fellow Yahoos, the principles that direct how we service our customers, the ideals that drive what we do and how we do it… We are committed to winning with integrity. We know leadership is hard won and should never be taken for granted… We respect our customers above all else and never forget that they come to us by choice. We share a personal responsibility to maintain our customers' loyalty and trust.”

—Yahoo! mission statement, reflecting on “Our Core Values”54

Yahoo! was the first major U.S. Internet content company to enter the China market, rolling out a Chinese-language search engine and establishing a Beijing office in 1999.55

“Self-discipline” signatory: In August 2002 Yahoo! became a signatory to the “Public Pledge on Self-discipline for the Chinese Internet Industry,” the “voluntary pledge” initiated by the Internet Society of China (see Section II, Part 2, above).56 Protesting the move at the time, Human Rights Watch Executive Director Kenneth Roth argued that by collaborating with state censorship in this fashion, Yahoo! would “switch from being an information gateway to an information gatekeeper.”57 Responding to the outcry from human rights groups, who pointed out that Yahoo! was not required by Chinese law to sign the pledge, Yahoo! associate senior counsel Greg Wrenn countered that “the restrictions on content contained in the pledge impose no greater obligation than already exists in laws in China.”58 In an August 1, 2006 letter to Human Rights Watch, Yahoo! stated that, “The pledge involved all major Internet companies in China and was a reiteration of what was already the case - all Intenet companies in China are subject to Chinese law, including with respect to filtering and information disclosure” (see Appendix xx for full text of letter). This is technically accurate as Microsoft and Google were not operating in China at the time. However, unlike Yahoo!, neither company has signed the pledge since beginning operations in China.

Search engine filtering: Like all other Chinese search engine services, Yahoo! China (http://cn.yahoo.com) maintains a list of thousands of words, phrases and web addresses to be filtered out of search results. (For information on how companies in general generate such lists, see Section II, Part 2.)

A concrete example of Yahoo!’s search engine filtering can be seen with the search term “Dongzhou” (东洲), the name of a village where police opened fire on demonstrators in the summer of 2005. An August 9, 2006 search on the unfiltered Yahoo.com returned 371,000 results, with most of the results on the first three pages being articles about the protests and shootings. A search on the same day of the same term in cn.yahoo.com (Yahoo! China) returned 106,000 results, with none of the results at least on the first three pages containing any links related to the protest and crackdown. Instead, the first few pages of results link to websites for businesses, schools, and other institutions with “dongzhou” in the name (see Figs. 2 & 3). Results on search engines normally order themselves based on the popularity of the webpage as calculated by mathematical algorithms, not by subjective decisions about the value and nature of the site’s content.

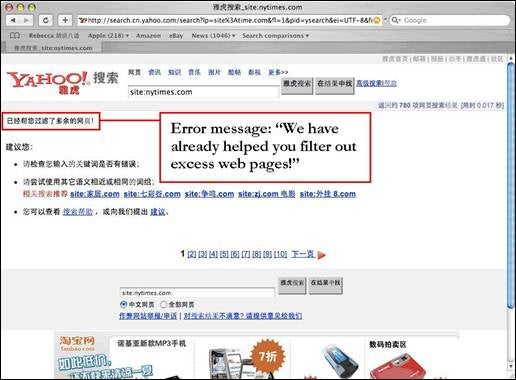

One way in which the number of results is substantially reduced is by the de-listing of entire websites from the search engine, so that the de-listed sites are skipped over when the search engine trawls the web for results. Neither Yahoo! nor any other company has released a list of websites that have been de-listed for their political and religious content. In Yahoo!'s case, such sites evidently include Radio Free Asia, Human Rights Watch, and the New York Times (see Appendix XII and Figs. 4 and 5). In other instances, searches for some politically sensitive keywords cause Yahoo.com.cn to deliver no page at all in response to the user’s request; all the user sees as a result is an error message appearing in her browser. In some instances such searches on Yahoo.com.cn result in server timeout, which causes the entire search engine to be unusable for any search for several minutes after the sensitive search is conducted (see Fig. 5).

Yahoo! user data employed by Chinese authorities to help convict critics: Yahoo! China provides a Chinese-language email service at Yahoo.com.cn. Independent tests have indicated, and Yahoo! executives have confirmed, that data for the Yahoo.com.cn email accounts is housed on servers inside the PRC.59 As of this writing, court documents obtained by human rights groups have shown that user data handed over by Yahoo! to Chinese law enforcement officials has assisted in the arrest and conviction of at least four people who used email accounts from the Yahoo.com.cn service. The four cases are as follows:

- Shi Tao: The Chinese journalist was sentenced in April 2005 to ten years in prison for “divulging state secrets abroad.” According to court documents translated by the Dui Hua Foundation and released by Reporters Sans Frontières. Yahoo! complied with requests from the Chinese authorities for information regarding an IP address connected to a cn.mail.yahoo.com email account. The information provided by Yahoo! Holdings (Hong Kong) Holdings linked Shi Tao to materials posted on a U.S.-based dissident website. 60 (See Appendix III for full case details.)

- Li Zhi: The Internet writer was sentenced in December 2003 to eight years in prison for “inciting subversion of the state authority.” According to the court verdict originally posted on the Internet by the Chinese law firm that defended him, user account information provided by Yahoo! was used to build the prosecutors’ case. 61 (See Appendix IV for full case details.)

- Jiang Lijun: The Internet writer and pro-democracy activist was sentenced in November 2003 to four years in prison for “subversion.” According to the court verdict obtained and translated by the Dui Hua Foundation, Yahoo! helped confirm that an anonymous email account used to transmit politically sensitive emails was used by Jiang.62 (See Appendix V for full case details.)

- Wang Xiaoning: The Internet writer and dissident was sentenced in September 2003 to ten years in prison for “incitement to subvert state power,” on the basis of essays he distributed on the Internet via email and Yahoo! Groups. According to the court judgment obtained by Human Rights in China, Yahoo! provided information to investigators pertaining to the email address and Yahoo! group used by Wang.63 (See Appendix VI for full case details.)

Figure 2: Yahoo.com unfiltered search on “Dongzhou” (results on first page are all discussing the incident in which military policy fired on protesting villagers)

In response to the public outcry after the case of Shi Tao came to light in early September 2005, Yahoo! spokesperson Mary Osako said: “Just like any other global company, Yahoo! must ensure that its local country sites must operate within the laws, regulations and customs of the country in which they are based.”64

Chinese court documents cite Yahoo! Holdings (Hong Kong) as the entity responsible for handing over user data in these cases. However, Yahoo! executives insist that the user data for email accounts under the Yahoo.com.cn service was housed on servers in China, not Hong Kong. According to Michael Callahan, Yahoo!’s Senior Vice President and General Counsel: “Yahoo! China and Yahoo! Hong Kong have always operated independently of one another. There was not then, nor is there today, any exchange of user information between Yahoo! Hong Kong and Yahoo! China.”65

Figure 3: Yahoo.com.cn (Yahoo! China) filtered search on “Dongzhou” (results are non-political and unrelated to the shooting incident or protests)

With data housed on servers in the PRC and managed by Yahoo! China employees, who are largely Chinese nationals, Yahoo! claims that it had no choice but to hand over the information: “When we receive a demand from law enforcement authorized under the law of the country in which we operate, we must comply,” said Yahoo!’s Michael Callahan.66 Callahan and other Yahoo! executives have also argued that, as with criminal cases in any country, Yahoo! employees generally have no information about the nature of the case and would not be in a position to know whether the user data requested relates to a political or ordinary criminal case.67 “Law enforcement agencies in China, the United States, and elsewhere typically do not explain to information technology companies or other businesses why they demand specific information regarding certain individuals,” Callahan said. “In many cases, Yahoo! does not know the real identity of

Figure 4: Yahoo! China search showing nytimes.com de-list, error message: “We have already helped you filter out excess web pages!”

individuals for whom governments request information, as very often our users subscribe to our services without using their real names.” These points were reiterated in the August 1, 2006 letter from Yahoo! to Human Rights Watch:

When we had operational control of Yahoo! China, we took steps to make clear our Beijing operation would comply with disclosure demands only if they came through authorized law enforcement officers, in writing, on official law enforcement letterhead, with the official agency seal, and established the legal validity of the demand. Yahoo! China only provided information as legally required and construed demands as narrowly as possible. Information demands that did not comply with this process were refused. To our knowledge, there is no process for appealing a proper demand in China. Throughout Yahoo!'s operations globally, we employ rigorous procedural protections under applicable laws in response to govemment requests for information.

Figure 5: Yahoo! China search showing hrw.org de-list: "no web page matching site: hrw.org could be found," and the disclaimer message: "according to relevant laws and regulations, a portion of results may not appear."

For this reason, Human Rights Watch believes that it is likely impossible for an Internet company to avoid intentionally, negligently, or unknowingly participating in political repression when its user data is housed on computer servers physically located within the legal jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China. Thus the first step towards human rights-compliant corporate conduct in China is to store user data outside of the PRC (or for that matter, outside any country with a clear and well-documented track record of prosecuting internationally protected speech as a criminal act).

Alibaba partnership: Unlike Microsoft and Google (cases detailed below), Yahoo! has chosen to relinquish control over what is done in China under its brand name to a Chinese partner. In August 2005, Yahoo! announced it would purchase a 40 percent stake in the Chinese e-commerce firm Alibaba.com. It was also announced that Yahoo! would merge its China-based subsidiaries into Alibaba, including the Yahoo! Chinese search engine (at: cn.yahoo.com) and Chinese email service (cn.mail.yahoo.com). On February 15, 2006, when Yahoo! (along with three other U.S.-based companies, Cisco, Microsoft, and Google), was brought before a U.S. House of Representatives committee hearing to explain its collaboration with Chinese government censorship requirements, Michael Callahan explained: “It is very important to note that Alibaba.com is the owner of the Yahoo! China businesses, and that as a strategic partner and investor, Yahoo!, which holds one of the four Alibaba.com board seats, does not have day-to-day operational control over the Yahoo! China division of Alibaba.com.”68 According to spokeswoman Mary Osako, Alibaba has had full control over Yahoo! China’s operational and compliance policies since October 2005.69

Statements by Alibaba’s CEO Jack Ma make it clear that his company has no intention of changing Yahoo! China’s approach to handing over user information. In November 2005, when the Financial Times asked him what he would have done in the Shi Tao case, he replied: “I would do the same thing… I tell my customers and my colleagues, that’s the right way to do business.”70 In a May 7, 2006 interview with the San Francisco Chronicle he elaborated further:

We set up a process today—I think a few months ago—if anyone comes looking for information from my company, not only Yahoo but also Taobao (Alibaba’s consumer auction site) and Alibaba (the auction site for businesses). If it’s national security or a terrorist, if it’s criminals, or people cheating on the Internet, that’s when we cooperate. The authorities must have a license or a document. Otherwise, the answer is no.71

Regarding censorship of Yahoo!’s search engine, Ma recently told the New York Times: “Anything that is illegal in China — it’s not going to be on our search engine. Something that is really no good, like Falun Gong?” He shook his head in disgust. “No! We are a business! Shareholders want to make money. Shareholders want us to make the customer happy. Meanwhile, we do not have any responsibilities saying we should do this or that political thing. Forget about it!”72

In the August 1, 2006 letter to Human Rights Watch, Yahoo!’s Michael Samway insisted that Yahoo! is not relinquishing all responsibility for Alibaba’s actions:

As a large equity investor with one of four Alibaba.com board seats, we have made clear to Alibaba.com's senior management our desire that Alibaba.com continue to apply the same rigorous standards in response to govemment demands for information about its users. We will continue to use our influence in these areas given our global beliefs about the benefits of the Internet and our understanding of requirements under local laws.

Response to criticism: Yahoo! executives respond consistently that search engine filtering is done in compliance with Chinese law, and that there is no alternative other than not doing business in China at all.73 In May 2006 Yahoo! CEO Terry Semel responded that providing the censored and politically compromised services still benefits the Chinese people more than if Yahoo! were absent from China altogether.74

On the eve of the congressional hearings, Yahoo! issued a press release titled “Our Beliefs as a Global Internet Company,” in which the company made the following commitments:

As part of our ongoing commitment to preserving the open availability of the Internet around the world, we are undertaking the following:

- Collective Action: We will work with industry, government, academia and NGOs to explore policies to guide industry practices in countries where content is treated more restrictively than in the United States and to promote the principles of freedom of speech and expression.

- Compliance Practices: We will continue to employ rigorous procedural protections under applicable laws in response to government requests for information, maintaining our commitment to user privacy and compliance with the law.

- Information Restrictions: Where a government requests we restrict search results, we will do so if required by applicable law and only in a way that impacts the results as narrowly as possible. If we are required to restrict search results, we will strive to achieve maximum transparency to the user.

- Government Engagement: We will actively engage in ongoing policy dialogue with governments with respect to the nature of the Internet and the free flow of information.75

Few concrete actions: Aside from repeated statements of regret about what happened to the four Chinese government critics and pledges of continued commitment to the above principles, Yahoo! executives have refused to do anything further to reverse the wrongs perpetrated on at least four Chinese citizens with Yahoo!’s help. At Yahoo!’s 2006 annual shareholder meeting, Anthony Cruz, a shareholder representing Amnesty International, challenged Yahoo! executives, including Chief Executive Terry Semel and co-founder Jerry Yang, to publicly ask the Chinese government to release imprisoned Internet dissidents. Yahoo!’s top management declined Cruz’s request. Yang said “We are going to do it in the way we think is most appropriate,” and “we don’t have a lot of choice once we are in the country and complying with the local laws.”76 Semel deflected responsibility back to the U.S. government: “I don’t think any one group and I don’t think any one company can change the course of governments….The way I believe major change comes about is when those groups work together and also put certain pressure on our own government….Ultimately, governments do bring about change in other governments, particularly if they are trading partners.”77

As Alibaba’s Jack Ma indicates above, in early 2006 Yahoo! asked Alibaba to adhere to a strict policy about the conditions under which it is acceptable to release user data to Chinese authorities. It appears, based on conversations with industry executives, that this was in response to public criticism. In his recent San Francisco Chronicle interview, Ma rejected the idea of moving user data overseas, saying “That doesn’t make any sense. Even outside China, if it is a terrorist, or if it is national security, you still have to deal with it. Even if your main operation is outside China, you still have to comply.”78 Absent from this reasoning is the recognition that different governments define national security very differently, and that courts in many other countries are independent, while Chinese courts have a well documented track record of acting as an arm of the government and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and treating peaceful challenges to the ruling party’s legitimacy as a threat to national security.79

In keeping with recent statements by Yahoo! executives, in May 2006 Yahoo! CEO Terry Semel responded that providing the censored and politically compromised services still benefits the Chinese people more than if Yahoo! were absent from China altogether.80 On July 27, 2006, Yahoo! China began running a disclaimer notice at the bottom of all search pages, which says in Chinese "According to relevant laws and regulations, some search results may not appear." While this represents a step in the right direction, Human Rights Watch does not believe that this notice in small print at the very bottom of all search results pages (regardless of the search term) represents "maximum transparency to the user" as stated by Yahoo! to be the company's goal in congressional testimony. This is especially the case when it is clear from test results that Yahoo! censors its results more heavily than its competitors but gives the user no explanation as to why this is necessary. "Maximum transparency to the user" would entail informing users of how many results have been censored and why, and giving clear information about how the search engine's censorship decisions get made, so that the user knows what he or she is missing and knows who is responsible for the content's absence. Without such steps, the search engine continues to play the role of non-transparent censor.

Chinese critics: After the case of Shi Tao was exposed by Reporters Sans Frontières and the Dui Hua Foundation, the Beijing-based dissident intellectual Liu Xiaobo wrote a long letter to Jerry Yang, in which he condemned such justifications as specious:

In my view, what Yahoo! has done is exchange power for money, i.e. to win business profit by engaging in political cooperation with China’s police. Regardless of the reason for this action, and regardless of what kinds of institutions are involved, once Yahoo! complies with the CCP to deprive human rights, what it does is no longer of a business nature, but of a political nature. It cannot be denied that China’s Internet control itself is part of its politics, and a despotic politics as well. Therefore, the “power for money” exchange that takes place between western companies like Yahoo! and the CCP not only damages the interests of customers like Shi Tao, but also damages the principles of equality and transparency, the rules that all enterprises should abide by when engaging in free trade. And it follows that if Yahoo! gains a bigger stake in the Chinese market by betraying the interests of its customers, the money it makes is “immoral money”, money made from the abuse of human rights. This is patently unfair to other foreign companies that do abide by business ethics.81 (The full text of Liu’s letter can be found in Appendix VII.)

After being censored by Microsoft’s MSN Spaces (details in following section on Microsoft), Chinese blogger Zhao Jing, a.k.a. Michael Anti, wrote that the Chinese people were probably still better off that Microsoft’s MSN and Google were engaged in China despite their compliance with Chinese censorship.82 However he had no such feelings for Yahoo!: “A company such as Yahoo! which gives up information is unforgivable. It would be for the good of the Chinese netizens if such a company could be shut down or get out of China forever.”83 He was even more blunt in an interview with the New York Times: “Yahoo is a sellout,” he said. “Chinese people hate Yahoo.”84 Such opinions are examples of the way in which Yahoo!’s behavior in China is viewed by Chinese intellectuals and opinion-leaders concerned with free speech issues.

While no comprehensive opinion survey of Chinese Internet user perceptions has been conducted to date, there is evidence that publicity about Yahoo!’s conduct in China has caused at least some Chinese Internet users to choose other email services. A question was recently posed in Chinese on a blog: “which do you trust more, yahoo.cn email, Gmail or Hotmail?” A number of respondents cited privacy concerns with Yahoo!, and others expressed appreciation that Gmail enables the user to use browser-based encryption through the “https” protocol.85

2. Microsoft Corp.

“As a successful global corporation, we have a responsibility to use our resources and influence to make a positive impact on the world and its people.”

—“Global Citizenship at Microsoft”86

“We remove a small number of URLs from the result pages in the MSN China Search site to omit inappropriate content as determined by local practice, law, or regulation [emphasis added]. We provide a link to a notice if search results have been filtered or may contain non-functional links but we do not block whole queries.”

—Pamela S. Passman, Vice-President, Global Corporate Affairs, responding to letter from Human Rights Watch87

While Microsoft has had a business and research presence in China since 1992, the Chinese version of the Microsoft Network (MSN) online portal was launched only in mid-2005, after the formation of a joint venture between MSN and Shanghai Alliance Investment Ltd. (SAIL) to create MSN China in May 2005.88 (Funded by the Shanghai City Government, SAIL is a venture fund led by Jiang Mianheng, son of former PRC president Jiang Zemin.)89

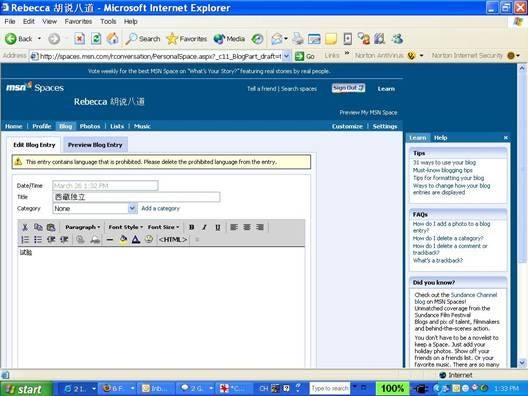

Blog censorship: Within a month of MSN China’s rolling out its Chinese portal, Microsoft came under criticism from the press and bloggers (both Chinese and Western) for censoring words such as “democracy” and “freedom” in the titles of its Chinese blogs.90 Meanwhile, testing of the service in December showed that censorship of MSN Spaces Chinese blogs had been extended beyond titles of the full blogs to the titles of individual blog posts themselves. As shown in Fig. 6, testing also showed that while sensitive words such as “Tibet independence” and “Falungong” (the banned religious group) could be posted in the body of blog posts, use of such words would cause the entire blog to be shut down within days, by Microsoft staff on Microsoft servers.91

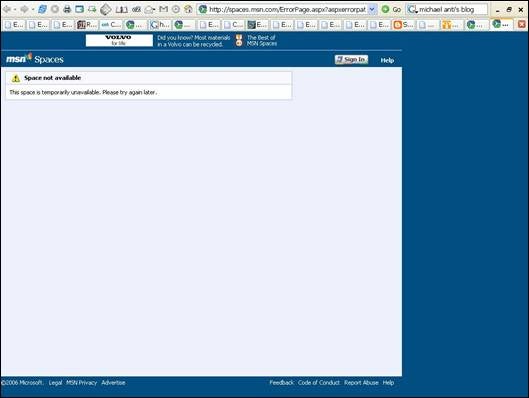

The extent of MSN Spaces censorship created an uproar after the popular blog of Zhao Jing, writing under the pseudonym Michael Anti, was shut down on December 30, 2005.92 In 2005 Zhao had become one of China’s edgiest journalistic bloggers, often pushing at the boundaries of what is acceptable. He had started blogging on MSN Spaces in August 2005 after his original blog hosted by the Scotland-based company Blog-City.com was blocked by Chinese Internet service providers. In December Zhao used his blog to speak out when propaganda authorities cracked down on Beijing News, a relatively new tabloid with a national reputation for exposing corruption and official abuse. The editor and deputy editors were fired and more than one hundred members of the newspaper’s staff walked out in protest. Zhao covered the crackdown extensively on his MSN Spaces blog, discussing behind-the-scenes developments, supported the walkout and called for a reader boycott of the newspaper. Microsoft told the New York Times that MSN Spaces staff deleted Zhao’s blog “after Chinese authorities made a request through a Shanghai-based affiliate of the company.”93

Microsoft’s response: Public outcry and criticism of Microsoft’s action was so strong in the United States that by late January 2006 Microsoft decided to alter its Chinese blog censorship policy.94 Called to testify before the U.S. House of Representatives in February to explain its collaboration with Chinese government censorship requirements, Microsoft outlined the following efforts at transparency while still complying with Chinese censorship requirements:

First, explicit standards for protecting content access: Microsoft will remove access to blog content only when it receives a legally binding notice from the government indicating that the material violates local laws, or if the content violates MSN’s terms of use.

Second, maintaining global access: Microsoft will remove access to content only in the country issuing the order. When blog content is blocked due to restrictions based on local laws, the rest of the world will continue to have access. This is a new capability Microsoft is implementing in the MSN Spaces infrastructure.

Figure 6: MSN Spaces – Error message when attempting to post blog entry with title “Tibet Independence”

Third, transparent user notification: When local laws require the company to block access to certain content, Microsoft will ensure that users know why that content was blocked, by notifying them that access has been limited due to a government restriction.95

Nina Wu, the sister of detained filmmaker and blogger Wu Hao, had been using an MSN Spaces blog from March 2006 until his release that July to describe her quest to secure

Figure 7: Error message appearing on December 30 after blog of Michael Anti (Zhao Jing) was taken down (http://spaces.msn.com/mranti/)

her brother’s release and her personal shock that his legal and constitutional rights appeared to have been ignored by Chinese authorities. (Wu Hao, who was working on a documentary film about Christians in China at the time of his disappearance on February 22, 2006, was held by Chinese State Security without formal arrest, charge, trial, or access to a lawyer until his release on July 11, 2006.) Throughout this time her blog was not taken down or blocked to Chinese users. Likewise, the wife of dissident AIDS activist Hu Jia has also been able to maintain a blog on MSN Spaces describing her husband’s ordeal, as well as similar ordeals experienced by the families of other activists. Both blogs have remained uncensored and visible, despite the fact that their subject matter is arguably as politically sensitive, if not more so, than the content on Michael Anti’s blog.96 On April 10 Nina Wu reflected on her own experiences with censorship:

After Haozi disappeared, browsing the Internet and searching for related information became a mandatory daily class. I have googled a great deal of information on “Hao Wu,” but I can’t visit many of the search results, especially addresses with .org suffixes. Eight or nine out of ten will return “Impossible to display this webpage.” I don’t know what kind of sensitive information these websites contain. Before, I did not believe in “Internet censorship.” This was because I used to visit mostly finance and investment websites, which rarely have problems. Only when I faced a serious predicament did I discover that this was a real problem.

Today someone asked me about the effect of Haozi’s incident on me and other family members. I think the most direct effect is that I began to be concerned about my own “rights” and the social problems that Haozi was concerned about.97

However, some other Chinese bloggers have reported takedowns of their MSN Spaces blogs in recent months.98 It is not known whether Chinese authorities have made requests for those blogs to be taken down, but if the blogs of Nina Wu and Zeng Jinyan remain visible due to Microsoft’s revised policies, this is a step in the right direction, and an example of the way in which companies can successfully resist pressure to proactively censor politically sensitive content.

By the end of 2005, MSN Spaces hosted more Chinese blogs than any other Chinese-language blog-hosting service, surpassing its homegrown PRC competitors.99 It remains to be seen at this writing how or whether Microsoft’s efforts to institute greater accountability and transparency will impact competition with MSN Spaces’ domestic Chinese competition.

Chinese bloggers react: While the blog of Zhao Jing, a.k.a. Michael Anti, was censored by MSN Spaces, Zhao has said on his blog and in media interviews that while he would have preferred not to have been censored, it is on balance better that MSN has found a way to compromise, yet still provide a platform on which ordinary Chinese can speak much more freely than before—albeit not completely freely. 100 Upon reading news that there would be congressional hearings he wrote:

Furthermore, at a time when globalization and politics are mixed up, I do not think that we can treat everything in black-and-white terms as being for or against the improvement of freedom and rights for the people of China. On one hand, Microsoft shut down a blog to interfere with the freedom of speech in China. On the other hand, MSN Spaces has truly improved the ability and will of the Chinese people to use blogs to speak out and MSN Messenger also affected the communication method over the Internet. This is two sides of the practical consequences when capital pursues the market. How the Americans judge this problem and mete out punishment is a problem for the Americans. If they totally prevent any compromised company from entering the Chinese market, then the Chinese netizens will not be freer at least in the short term. Besides, we must distinguish between the sellout by Yahoo! and the compromise by Microsoft, because they are completely different matters.101

In the days after Zhao’s blog was censored, many other Chinese bloggers (many of them on MSN Spaces) carried out lengthy discussions of his case, republishing his final posts, and generally expressing sympathy. They were not censored by MSN, even though Zhao himself had been. An interesting essay by a blogger named Chiu Yung began to circulate in the Chinese blogosphere, arguing that MSN did the right thing by “sacrificing” Anti. If it hadn’t, the reasoning went, the entire MSN Spaces service would become unavailable to all Chinese bloggers, and that would be a greater loss. The essayist wrote that Chinese people should thank MSN for the same reason they should thank the U.S. for not implementing sanctions. He also argued that Chinese people themselves are ultimately responsible for allowing their fellow countrymen to be censored, and that the ultimate solution is going to have to be initiated by the Chinese themselves.102

> >

>

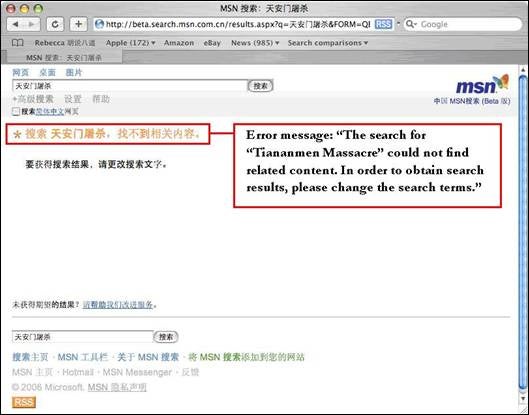

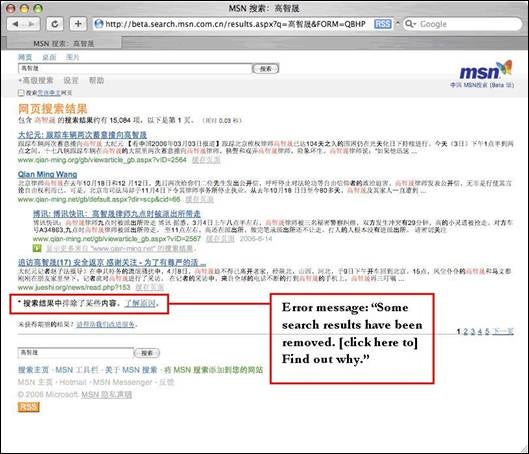

Figure 8: MSN Search on “Tiananmen Massacre”

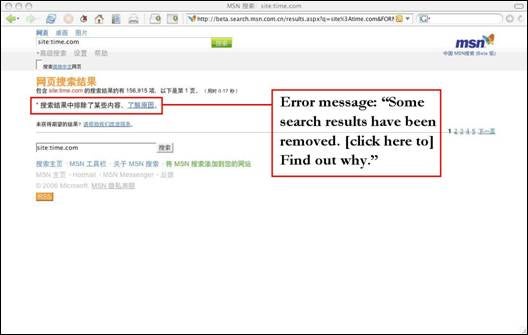

Search engine: In October, Microsoft launched a search technology center in China and on January 3, 2006, MSN launched its own “beta” (test-version) Chinese search engine, at http://beta.search.msn.com.cn, which was integrated into the MSN China portal as http://search.msn.com.cn.103 Initial testing of the “beta” version in January by editors at CNet News.com showed the MSN search tool linking to a number of sites

Figure 9: MSN Beta Chinese search on “Tiananmen Massacre”

that are blocked by Yahoo! and Google search, including Human Rights Watch’s hrw.org, although there were some other sites not blocked by Google and Yahoo! (such as time.com) that were blocked by MSN search.104 (See Section III for Human Rights Watch’s detailed analysis comparing MSN’s Chinese search results to those of Google, Yahoo!, and Baidu.) Meanwhile, on searches that have been censored to exclude politically sensitive search results, the MSN Chinese search engine often (but not always) includes a notification to users at the bottom of the page which says: “The search results have omitted some content. [click here to] Find out why.” The hyperlinked text then takes the user to an explanatory page containing explanations of a list of features and potential questions related to MSN search results. Near the bottom of the page is the heading “When there are no search results or filtered search results,” under which is the

Figure 10: Search on MSN Chinese “Beta” for “Gao Zhisheng” (human rights lawyer)

following text: “When there are no or very few search results, please try a similar word or a phrase that describes the word’s meaning. Sometimes, according to the local unwritten rules, laws, and regulations, inappropriate content cannot be displayed.”105 MSN also de-lists websites from its search engine, as discussed in Section III and depicted in Fig. 11 of this section. Human Rights Watch has found that while MSN’s Chinese search engine turns up more diverse information on political and religious subjects than Yahoo! and Baidu, it censors content more heavily than Google.cn (see Section III for details).

Figure 11: MSN de-listing of time.com

Hotmail stays offshore: For the time being, Microsoft executives have admitted that Microsoft has held off providing Chinese-language Hotmail services hosted on servers inside the PRC due to concerns that Microsoft would find itself in the same position as Yahoo!, that is, subjecting its local employees to official requests for email user data, with which they would feel compelled to comply. Microsoft has been successful in refusing Chinese government requests for Hotmail user data in the past, on the grounds that the data is not under PRC legal jurisdiction.

3. Google, Inc.

"Ten Things that Google has found to be true...

6. You can make money without doing evil.”—Google, “Our Principles”106

“The prize is a world in which every human being starts life with the same access to information, the same opportunities to learn and the same power to communicate. I believe that is worth fighting for.”

—Eric Schmidt, chief executive of Google107

“I think it's arrogant for us to walk into a country where we are just beginning to operate and tell that country how to operate.”

—Eric Schmidt, chief executive of Google108

While Google has had a Chinese language search engine since September 2000, the company did not set up a physical presence inside the People’s Republic of China until the launch of its Beijing research and development center in July 2005.109

Early problems: In September 2002, the Chinese government temporarily blocked Google.com on Chinese Internet service providers, making it completely impossible for Internet users inside China to access Google’s search engine without use of a proxy server or other circumvention tools. Instead, people typing Google.com into their search engines would be automatically re-directed to Chinese search engines. Soon after this happened, Google issued a statement that the company was working with Chinese authorities to restore access. The block was lifted after two weeks.110 In an interview not long after Google was unblocked, co-founder Sergey Brin stated that Google did not negotiate with Chinese authorities to have the search engine unblocked, and that instead “popular demand” had made it impossible to keep it blocked.111 It is not clear in what way popular demand was measured or how it changed from 2002 to 2006, when Google decided to launch the censored Google.cn site.

However, testing conducted by the OpenNet Initiative (ONI) in 2004 concluded that “while Google is accessible to Chinese users, not all of its functions are available; because of China’s content filtering technologies, users of Google within China experience a much different Google than those outside.” China was (and still is) blocking––at the service router level––all access to Google’s “cache” (the link provided along with each search that enables you to access an earlier “snapshot” of the webpage you are looking for, in case the real version has been taken down or rendered inaccessible for whatever reason.112

Additionally, as with all search results, the ONI test found that the Chinese censorship system was blocking thousands of Google search results that would manifest in one of two ways: 1) When a search on a particular word or phrase yielded links to banned sites being filtered by the Chinese “firewall,” the user encounters an error page upon clicking on one of the censored links. There is no warning that this will happen and no explanation after it happened that the failure to connect to the page is not the result of user error or technical failure but deliberate blockage. 2) When the user types certain keywords into a Google search, their connection to Google is terminated and they receive no search results. Again there is no explanation for why this happens. As the ONI points out, “Neither China’s keyword filtering nor the mechanism used to filter the Google cache is specific to Google.”113 In other words, the actual censorship being done in this case is by employees of the Internet Service Providers and by Chinese government employees, not by Google employees.

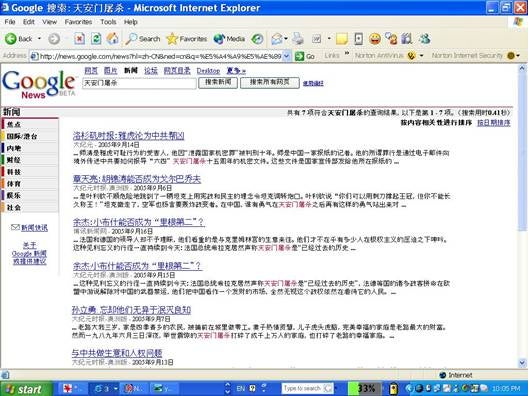

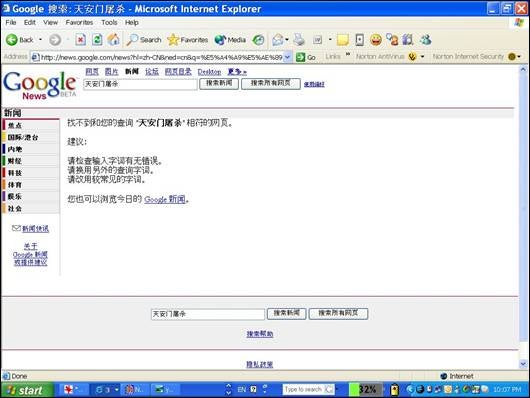

Passive censorship in Chinese-language Google News: In September 2004 the launch of a Chinese-language edition of Google News also marked Google’s first step in the direction of compromise with Chinese censorship practices. When the user typed in words or phrases that yielded blocked results, Chinese Google News did not display those results (see Figs 12 & 13 for a comparison of a search for “Tiananmen massacre” conducted on regular Google News and Chinese Google News in October 2005).The filtering was being done by the Chinese government and Chinese ISPs, not directly by Google. But Google opted not to display links on Chinese Google News that would lead to error pages or termination of the session.

In response to criticism by human rights and free speech groups, Google responded on its official blog:

For Internet users in China, we had to consider the fact that some sources are entirely blocked. Leaving aside the politics, that presents us with a serious user experience problem. Google News does not show news stories, but rather links to news stories. So links to stories published by blocked news sources would not work for users inside the PRC -- if they clicked on a headline from a blocked source, they would get an error page. It is possible that there would be some small user value to just seeing the headlines. However, simply showing these headlines would likely result in Google News being blocked altogether in China.114

Active censorship with Google.cn: In December 2005 Google received its license as a Chinese Internet service. Then on January 26, 2006, Google launched a censored version of its search engine for the Chinese market in which Google became the censor, not merely the victim of state and ISP censorship. Tests of the site showed that Google.cn censors thousands of keywords and web addresses.115 The “block list” was not given to Google by the Chinese government, but rather––as with the other search engines operating in China––was created internally by Google staff based on their own testing of what terms and web addresses were being blocked by Chinese Internet service providers.116

Google’s CEO Eric Schmidt explained that Google’s decision to launch a censored service was the result of a great deal of internal wrangling within the company, but that ultimately Google executives concluded that censorship was necessary for Google to provide more and better service to Chinese Internet users. “We concluded that although we weren’t wild about the restrictions, it was even worse to not try to serve those users at all,” he said. “We actually did an evil scale and decided not to serve at all was worse evil.”117

Figure 12: Search on regular Google News: “Tiananmen Massacre”

On Google’s official blog, senior policy counsel Andrew McLaughlin explained that the company’s top management had decided that being in China with a censored service would serve Chinese users better than if Google refused to censor. McLaughlin argued that while Google.com remained accessible to Chinese Internet users, “Google.com appears to be down around 10 percent of the time. Even when users can reach it, the website is slow, and sometimes produces results that when clicked on, stall out the user’s browser.”118 He defended Google’s decision against critics who slammed the company for compromising its signature corporate motto: “don’t be evil.”119

McLaughlin continued:

Launching a Google domain that restricts information in any way isn’t a step we took lightly. For several years, we’ve debated whether entering the Chinese market at this point in history could be consistent with our mission and values. Filtering our search results clearly compromises our mission. Failing to offer Google search at all to a fifth of the world’s population, however, does so far more severely. Whether our critics agree with our decision or not, due to the severe quality problems faced by users trying to access Google.com from within China, this is precisely the choice we believe we faced. By launching Google.cn and making a major ongoing investment in people and infrastructure within China, we intend to change that. 120

Figure 13: Filtered search on Chinese Google News: “Tiananmen Massacre”

Clearly, Google felt that it was losing market share to its number-one competitor in the Chinese search engine market, Baidu, as a result of problems Chinese users were having accessing Google.com. Users regularly experienced Internet connection failures resulting from clicking on links appearing in Google.com search results that happened to be censored by Chinese Internet service providers.

It is difficult to assess the extent to which inaccessibility was truly affecting Google’s market position without access to Google’s full data from the results of its accessibility testing, which Google has not released.121

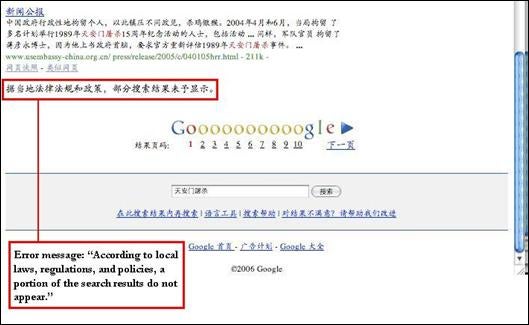

Google de-lists politically sensitive websites from the Google.cn search engine, but does not publicize a list of which sites are de-listed and does not notify the site’s owners. In an effort to increase transparency with users, Google.cn included one feature that is also being used to some degree by MSN Chinese “beta” search. In all cases in which search results are censored, Google.cn displays a message at the bottom of the screen: “These search results are not complete, in accordance with Chinese laws and regulations.” Google claimed in a statement that adding this level of transparency to censorship justified its decision to become an active censor. According to Google’s McLaughlin, “Chinese regulations will require us to remove some sensitive information from our search results. When we do so, we’ll disclose this to users, just as we already do in those rare instances where we alter results in order to comply with local laws in France, Germany and the U.S.”122 (See Figs. 14, 15 & 16.)

It is not true, however, that Google provides the same amount of disclosure about its Chinese censorship practices as it does when responding to court take-down orders in France, Germany, and the United States. On Google.com, results are often removed due to “cease and desist” requests over copyright violation. Search pages in which results have been removed include the following notice at the bottom of the page: “In response to a complaint we received under the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act, we have removed 1 result(s) from this page. If you wish, you may read the DMCA complaint that caused the removal(s) at ChillingEffects.org.”123 A link then enables the user to read the full legal request that resulted in removal.124 In France and Germany, when results are removed from a Google search, a notice at the bottom of the page notifies the user of exactly how many results were removed. It reads: “In response to a legal request

>

>

Figure 14: Google.com search on “Tiananmen Massacre”

submitted to Google, we have removed [x number of] result(s) from this page. If you wish, you may read more about the request at ChillingEffects.org.”125 A link then directs the user to a specific page on ChillingEffects.org with information about the legal circumstances under which the result was removed.126

Figure 15: Google.cn search on “Tiananmen massacre”

Figure 16: Google.cn de-listing of hrw.org

The level of transparency Google currently provides to the French, Chinese, and U.S. user is in itself criticized as inadequate by many technology analysts and free speech activists.127 While Chinese legal and political circumstances surrounding censorship are very different from these countries, and government practices are several degrees less accountable and transparent, Google nonetheless owes the Chinese user the maximum extent of information possible about what has been removed and why. While Google has made a gesture in that direction by generating a generic notice when some search results have been removed, Human Rights Watch believes that it is possible and necessary for Google to provide even the Chinese user with more specific information about the number of results removed and why.

In his February 15, 2006 congressional testimony, Google Vice President Eliot Schrage pointed out that in addition to a disclosure policy of informing Chinese users whenever search results have been removed, Google’s new site will provide a link to the uncensored Google.com, ensuring that it remains available to Chinese users. His testimony also indicated that Google has observed and learned from the experiences of Yahoo! and Microsoft: “Google.cn today includes basic Google search services, together with a local business information and map service. Other products––such as Gmail and Blogger, our blog service––that involve personal and confidential information will be introduced only when we are comfortable that we can provide them in a way that protects the privacy and security of users’ information.”128

Schrage also said that Google supports industry cooperation to minimize censorship:

Google supports the idea of Internet industry action to define common principles to guide the practices of technology firms in countries that restrict access to information. Together with colleagues at other leading Internet companies, we are actively exploring the potential for guidelines that would apply for all countries in which Internet content is subjected to governmental restrictions. Such guidelines might encompass, for example, disclosure to users, protections for user data, and periodic reporting about governmental restrictions and the measures taken in response to them.129

Google also argues that these voluntary actions would be much more effective with help from the U.S. government’s executive branch:

The United States government has a role to play in contributing to the global expansion of free expression. For example, the U.S. Departments of State and Commerce and the office of the U.S. Trade Representative should continue to make censorship a central element of our bilateral and multilateral agendas.

Moreover, the U.S. government should seek to bolster the global reach and impact of our Internet information industry by placing obstacles to its growth at the top of our trade agenda. At the risk of oversimplification, the U.S. should treat censorship as a barrier to trade, and raise that issue in appropriate fora.130

Chinese netizen reactions: Opinions differ in China––even among people who chafe against official restrictions on their freedom of speech––as to whether Google’s compromise was acceptable. When Google.cn was first rolled out, a number of Chinese bloggers concerned with free speech issues were quick to condemn the move. One labeled the new service the “Castrated Google.”131 Others, such as Michael Anti, were more philosophical, pointing out that while Google had made a compromise, it had done so after considerable weighing of the human consequences, and made a conscious decision not to provide services that would put itself in the position of having its local employees––with no choice but to comply––into conflict with the Chinese government demands to censor content or, even worse, to hand individuals over to the police.132

Some Chinese bloggers have also expressed concern that the existence of the censored Google.cn will make it easier for Chinese ISP’s to block Google.com without excessive public outcry, because some form of Google search remains available.133 Indeed, in late May and the first days of June—the most politically sensitive time of the year due to the anniversary of the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre—several Chinese Internet users in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou reported that Google.com was consistently inaccessible while the censored Google.cn remained accessible as normal. 134 Users also reported problems accessing Gmail and other Google-hosted services.135 Google spokespersons neither confirmed nor denied what was happening, but acknowledged user reports and said that the company was investigating.136 By June 9the block was off, prompting speculation by Reporters Sans Frontieres that the easing was thanks to user outcry, although what happened remained difficult to assess, given that neither Google nor the Chinese government have elaborated publicly on the facts of the situation.137

Chinese Internet users responded with anger, directed primarily at whoever was responsible for creating the blockage. Many bloggers protested by publishing on their blogs the picture of a voodoo doll labeled as “the person who makes it impossible to access Google,” with needles stuck in its heart, and the caption: “one click on this site equals one pin prick.”138 (See Fig. 17.)

Figure 17: Anti-censorship voodoo doll displayed by Chinese blogger “keso” (screen grab on June 15, 2006)

Some Chinese bloggers, however, also blamed Google for not being upfront and honest with China’s frustrated netizens about what was going on. “Chinese bloggers are discontented with Google China’s official blog, since it did not have any explanation on the issues,” wrote the Chinese blogger “Tangos” at China Web 2.0 Review.139 In fact, Google’s Chinese blog made no mention of the entire situation, despite the fact that the Google.com blockage was the primary concern of Google users during that period.140 Chinese blogger “Herock” writes: “I can’t believe Google China isn’t aware that nobody can get on Google these days. In my view, reacting to these kinds of big events is part of the mission of a corporate blog. But the method of ‘Hei Ban Bao’ [the Google China blog – literally translated as ‘blackboard news’] is to pretend that this never happened and not say a word. This makes me feel that ‘Hei Ban Bao’ is totally useless.”141 Useless or not, the situation certainly demonstrates that Google’s China management are not being honest with their users, and that their users not only notice, but at least many of the influential and vocal ones seem to care a great deal.

A few days later Google co-founder Sergey Brin told reporters in Washington, D.C., that most Google users in China use the uncensored Google.com, not the censored Google.cn. He said that while Google had acquiesced to Chinese government censorship demands, they were “a set of rules that we weren’t comfortable with.” He then continued: “We felt that perhaps we could compromise our principles but provide ultimately more information for the Chinese and be a more effective service and perhaps make more of a difference.” He added that “perhaps now the principled approach makes more sense.” He then said: “It’s perfectly reasonable to do something different, to say: ‘Look, we’re going to stand by the principle against censorship, and we won’t actually operate there.’ That’s an alternate path….It’s not where we chose to go right now, but I can sort of see how people came to different conclusions about doing the right thing.”142

Asked by reporters for comment soon thereafter, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Liu Jianchao responded at a press conference as follows:

China holds a positive attitude toward cooperation with Google in the information area. Any economic and trade cooperation should be conducted within the framework of law. We hope that corporations operating in China can abide by Chinese law.143

Chinese blogger Keso had this reaction:

Liu Jianchao’s statement actually equals an admission that the blocking of Google was done by us because Google didn’t respect Chinese law. But China’s spokesman will never clearly tell the foreigners what article of the law Google violated, and that the blocking is being done by which law. Foreigners usually want to be able to conduct commercial activities according to clear laws which they can follow. But in China, a lot of things are like Zen and can’t be explained. Without some breakthrough in thinking, if you want to comprehend the Chinese way, unfortunately you also have to invest a lot of time. 144

The comments thread following Keso’s post is long and lively. Some sympathized with Google’s situation or commented that competitor Baidu must be celebrating. Some expressed frustration with the system. Some wrote satirical poems and ditties, while others posted widely-used shorthand acronyms for obscenities in reference to Baidu and the Chinese government. Others remarked that Google is naive to think it can do anything other than adapt to the Chinese political situation. Some invoked patriotism and national pride in homegrown products and the need for foreigners to respect Chinese law. Others discussed the detailed business and advertising reasons for Google.cn’s lack of success so far, or argued about the quality of Baidu versus Google.145 These comments are among the many examples of the extent to which Chinese Internet users themselves disagree over how multinational companies should respond to Chinese government demands.

It is worth noting that there is a perception among Chinese Internet users that Baidu gains competitively from Google’s problems. This is one further example of the way in which lack of transparent laws and procedures creates an unfair playing field for international businesses seeking to compete in the Chinese market. In light of this situation, Google should be justified in challenging Chinese ISP’s blockage of Google.com—when done without clear legal reason, procedure or process for appeal—as an unfair and extralegal barrier to trade, calling upon the U.S. Trade Representative and the World Trade Organization for support.

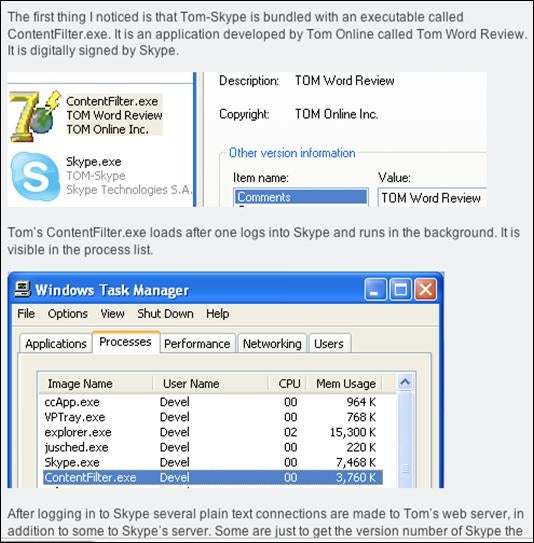

4. Skype

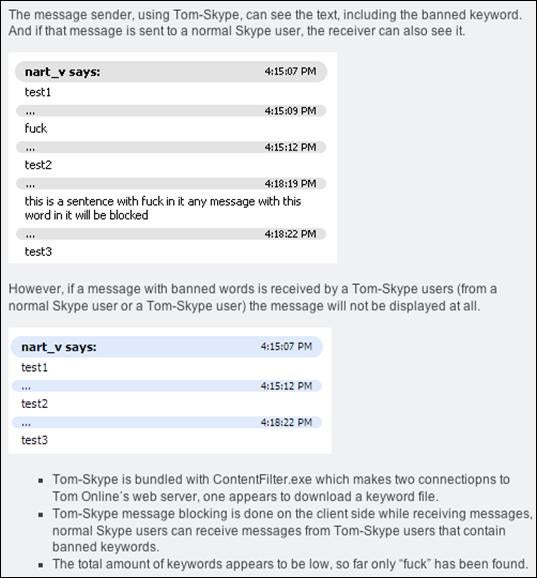

In November 2004 Skype (which was acquired by eBay in September 2005) launched a simplified Chinese-language version of Skype, the online voice and chat client, jointly developed with TOM Online Inc., a Chinese wireless Internet company. In September 2005 Skype and TOM formed a joint venture company to “develop, customize and distribute a simplified Chinese version of the Skype software and premium services to Internet users and service providers in China.”146 The Chinese client distributed by TOM Online employs a filtering mechanism that prevents users from sending text messages with banned phrases such as “Falungong” and “Dalai Lama.”147

In an April 2006 interview with the Financial Times, Skype’s chief executive Niklas Zennström responded to a question about Skype’s Chinese-language censorship, explaining that Skype was simply complying as necessary with local law. “Tom had implemented a text filter, which is what everyone else in that market is doing,” the Financial Times quoted Mr Zennström as saying. “Those are the regulations.”148 Neither Zennström nor any other Skype executive, however, has clarified exactly which regulations are being complied with or which keywords are involved. Nor has Skype made public a full list of the keywords being blocked by the TOM-Skype client. Skype’s Jaanus Kase followed up with a post on the official Skype blog with some further clarification. He said:

TOM operates a text filter in TOM-Skype. The filter operates solely on text chats. The filter has a list of words which will not be displayed in Skype chats. The text filter operates on the chat message content before it is encrypted for transmission, or after it has been decrypted on the receiver side. If the message is found unsuitable for displaying, it is simply discarded and not displayed or transmitted anywhere.

It is important to underline:

- The text filter does not affect in any way the security and encryption mechanisms of Skype.

- Full end-to-end security is preserved and there is no compromise of people’s privacy.

- Calls, chats and all other forms of communication on Skype continue to be encrypted and secure.

- There is absolutely no filtering on voice communications.149

Chinese bloggers and Internet entrepreneurs responded in the blog’s comments section, challenging the necessity of Skype’s action. Examples of the comments include:

Skype don’t need necessarily need [sic] Tom to operate business in China. Skype itself can do the job well since users help Skype spreading anywhere. I don’t know or even can’t image any government enforces a software to do text filtering unless they do self-policing first. Skype is misled by Tom, the useless partner. Basically Skype is different from Google or Yahoo online service, it’s standalone software.

Geeks in China ever regard Skype as the hero to play important role to conduct secure communication. They are very disappointed now to see Skype join the evil business list. Sigh!

The cooperation is definitely reducing the reputation of Skype in this country. It will also pushing [sic] users away. Please re-consider the decision (cooperating with ToM and anti-freedom). I suppose Skype the company is becoming a responsible business, why not rethink it?150

After blogger criticism that he was ignoring users’ censorship concerns, Kase eventually responded with a comment at the RConversation.com blog: “Skype has taken a decision to have TOM Online actively manage its business in China, thus you should be addressing these questions to TOM.”151

Interestingly, when Human Rights Watch downloaded and tested the TOM-Skype client, entering lists of banned words from the “block lists” of other services (such as those listed in Appendices I and II), none of the words were found to be blocked. Other Internet users in China have reported similar results. Nart Villeneuve of the OpenNet Initiative downloaded and analyzed the TOM-Skype client and found that, after running long lists of commonly banned words (including “Falungong” and “Dalai Lama”), he only succeeded in triggering the blockage of one common English-language obscenity. He did discover, however, that when installing TOM-Skype onto his computer, the censoring program ContentFilter.exe was also automatically installed without any user notification. Upon logging in, the program downloaded an encrypted file called “keyfile” onto his computer. (The file remained on his computer after he uninstalled TOM-Skype later.) He was unable to decrypt the file, but he writes in his blog that it appeared to be “a keyword list file of some sort.” Villeneuve observes that the keyword blocking takes place on the side of the message recipient and that any message containing the blocked keyword (sent by any Skype user to any user of the TOM-Skype client) fails to appear on the recipient’s screen.152 Human Rights Watch has downloaded the TOM-Skype client and had an identical experience. The censorware was downloaded onto a Human Rights Watch researcher’s hard drive without notification, and we received identical results to Villeneuve’s when testing lists of keywords frequently banned in China. Thus, while TOM-Skype currently does not censor many words, the TOM-Skype client is ready upon installation to receive updates from TOM-Skype at any time, adding new censored words without the user’s knowledge.

Skype has not acknowledged and is not known to be censoring its text chat in any other country besides China. The justification given by Skype executives for censorship is, in essence, the peer pressure defense: “Everbody does it.” To Skype’s credit, as of this writing very few words are being censored and no political or religious words have been discovered to be among them. It is not clear whether this is the result of recent public scrutiny or whether the TOM-Skype client had not yet added words to the block list. The key question now is whether Skype will resist adding new words to the block list without a legally binding written court order from the Chinese authorities to do so, or whether TOM-Skype will take an initiative proactively to censor. However, TOM-Skype does not inform users that censorware will be installed on their computer at the same time that the TOM-Skype software is installed. Skype executives have said that their local partner is carrying out “best practice” in the Chinese market. The installation of censorware without informing the user is actually considered to be “worst practice” in the Internet industry.

In order to set the standard for “best practices” in dealing with the Chinese government’s pressure to censor its users, Human Rights Watch recommends that Skype should prevail upon its business partner to: 1) resist adding any further keywords to the TOM-Skype censorship list without a court order forcing them to do so; and 2) inform users clearly and prominently on the download page that censorware will be installed along with the TOM-Skype client. It is not too late for Skype to resist the “race to the bottom” taking place in China, in which more and more multinational companies are participating and thus legitimizing China’s system of censorship without questioning a) whether the standard practices have any grounding even in Chinese legal procedure; b) whether they are truly necessary in order to function in China; or c) whether market advantage might be gained by making greater efforts than the domestic competition to maximize user interests and rights.

Figure 18: Detail from Nart Villeneuve blog post about TOM-Skype censorware

Figure 19: Detail from Nart Villeneuve’s blog post depicting censored chat on TOM-Skype

[54] “Yahoo! We Value…” Yahoo Mission Statement, 2004 [online], http://docs.yahoo.com/info/values/ (retrieved July 27, 2006).

[55] “Yahoo! Introduces Yahoo! China,” Yahoo! corporate press release, September 24, 1999 [online], http://docs.yahoo.com/docs/pr/release389.html (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[56] Jim Hu, “Yahoo yields to Chinese web laws,” CNet News.com.

[57] “Yahoo! Risks abusing human rights in China,” Human Rights Watch news release, August 9, 2002, http://www.hrw.org/press/2002/08/yahoo080902.htm.

[58] Jim Hu, “Yahoo yields to Chinese web laws,” CNet News.com.

[59] “Testimony of Michael Callahan, Senior Vice President and General Counsel, Yahoo! Inc., Before the Subcommittees on Africa, Global Human Rights and International Operations, and Asia and the Pacific,” U.S. House of Representatives Committee on International Relations, Joint Hearing: “The Internet in China: A Tool for Freedom or Suppression?” February 15, 2006 [online], http://wwwc.house.gov/international_relations/109/cal021506.pdf, and Yahoo! corporate press release, undated, http://yhoo.client.shareholder.com/press/ReleaseDetail.cfm?ReleaseID=187725 (both retrieved July 11, 2006).

[60] Reporters Sans Frontières, “Information supplied by Yahoo! helped journalist Shi Tao get 10 years in prison,” September 6, 2005 [online], http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=14884 (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[61] For a partial English translation see http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2006/02/yahoo_helped_sentence_another_cyber_dissident_to_8_year_1.php (retrieved July 11, 2006); for the full Chinese court document see http://www.peacehall.com/news/gb/china/2006/02/200602051139.shtml; for a full English translation by Hong Kong blogger Roland Soong, see http://www.zonaeuropa.com/20060209_2.htm (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[62] The original Chinese court document and English translation are at http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=17180 (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[63] The original document and translation are at http://hrichina.org/public/contents/press?revision%5fid=27803&item%5fid=27801 (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[64] “CHINA: Yahoo gave email account data used to imprison journalist,” Committee to Protect Journalists 2005 News Alert, September 7, 2005 [online], http://www.cpj.org/news/2005/China07sept05na.html (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[65] Callahan testimony, U.S. House of Representatives Committee on International Relations, Joint Hearing: “The Internet in China.”

[66] Ibid. See also: “Chinese man ‘jailed due to Yahoo,’“ BBC News, February 9, 2006 [online], http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/4695718.stm (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[67]“Yahoo Writer Jailed in China,” Red Herring, February 9, 2006 [online], http://www.redherring.com/Article.aspx?a=15659&hed=Yahoo+Writer+Jailed+in+China (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[68] Callahan testimony, U.S. House of Representatives Committee on International Relations, Joint Hearing: “The Internet in China.”

[69] “Yahoo Writer Jailed in China,” Red Herring.

[70] Mure Dickie, “Yahoo backed on helping China trace writer,” FT.com. November 10, 2005 [online], http://news.ft.com/cms/s/7ed7a41e-515f-11da-ac3b-0000779e2340.html (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[71] “ALIBABA.COM On the Record: Jack Ma,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 7, 2006 [online], http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/chronicle/archive/2006/05/07/BUGAQIJ8221.DTL (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[72] Clive Thompson, “Google’s China Problem,” New York Times Magazine, April 23, 2006 [online], http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/23/magazine/23google.html?ex=1303444800en=9721027e105631bfei=5088partner=rssnytemc=rss&pagewanted=all (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[73] Nate Anderson, “Yahoo on China: We’re doing some good,” Ars Technica, May 12, 2006 [online], http://arstechnica.com/news.ars/post/20060512-6823.html (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[74] Nate Anderson, “Yahoo on China,” Ars Technica.

[75] “Yahoo!: Our Beliefs as a Global Internet Company,” Yahoo! corporate press release, undated [online], http://yhoo.client.shareholder.com/press/ReleaseDetail.cfm?ReleaseID=187401 (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[76] Elinor Mills, “Yahoo Blog:Yahoo says no to Amnesty International on China,” CNet News.com, May 25, 2006, http://news.com.com/2061-10811_3-6077174.html (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[77] Ibid.

[78] “ALIBABA.COM On the Record: Jack Ma,” San Francisco Chronicle.

[79] See, among others, Human Rights Watch/Asia, “Whose Security? State Security in China’s New Criminal Code,” A Human Rights Watch Report, vol. 9, no. 4(C) April 1997, http://www.hrw.org/reports/1997/china5/; “China: Fair Trial for New York Times Researcher,” Human Rights Watch news release, June 2, 2006, http://hrw.org/english/docs/2006/06/02/china13498.htm; and U.S. State Department, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2005: China,” March 8, 2006 [online], http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2005/61605.htm (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[80] Nate Anderson, “Yahoo on China,” Ars Technica.

[81]Liu Xiaobo, “An Open Letter to Jerry Yang, Chairman of Yahoo! Inc. Regarding the Arrest of Shi Tao,” China Information Center, October 14, 2005 [online], http://www.cicus.org/news/newsdetail.php?id=5421 (retrieved July 11, 2006).

[82] Zhao Jing, “Guanyu Weiruan shijian he meiguo guohui keneng de lifa,” January 14, 2006, http://anti.blog-city.com/1603202.htm (retrieved July 16, 2006).

[83] Zhao Jing, “The Freedom of Chinese Netizens Is Not Up To The Americans,” blog, original Chinese at http://anti.blog-city.com/1634657.htm; English translation by Roland Soong at EastSouthWestNorth, http://www.zonaeuropa.com/20060217_1.htm (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[84]Clive Thompson, “Google’s China Problem,” New York Times Magazine.

[85] http://spaces.msn.com/rconversation/blog/cns!A325F2EACCC417CF!110.entry?_c=BlogPart#permalink

[86] Global Citizenship at Microsoft, [online], http://www.microsoft.com/about/corporatecitizenship/citizenship/default.mspx (retrieved July 27, 2006)

[87] Letter from Pamela S. Passman, Vice President, Global Corporate Affairs, Microsoft Corporation, to Human Rights Watch, July 21, 2006.

[88] “Microsoft Prepares to Launch MSN China,” Microsoft news release, May 11, 2005, http://www.microsoft.com/presspass/press/2005/may05/05-11MSNChinaLaunchPR.mspx (accessed July 12, 2006).

[89] Ibid. See also Allen T. Cheng, “Shanghai’s ‘King of I.T.’,” Asiaweek.com, February 9, 2001 [online], http://www.pathfinder.com/asiaweek/technology/article/0,8707,97638,00.html (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[90] “Screenshots of Censorship,” blog, Global Voices, June 16, 2005,

http://www.globalvoicesonline.org/?p=238; and http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/4088702.stm (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[91] Tests conducted by author between December 10 and 30, 2005, initially for the book chapter: Rebecca MacKinnon, “Flatter World and Thicker Walls? Blogs, Censorship and Civic Discourse in China” in Daniel Drezner and Henry Farrell, eds., The Political Promise of Blogging (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, publication pending), draft version under the title “Chinese Blogs: Censorship and Civic Discourse” at

http://rconversation.blogs.com/rconversation/files/mackinnon_chinese_blogs_chapter.pdf (retrieved July 14, 2006).

[92] Roland Soong, “The Anti Blog is Gone,” EastSouthWestNorth, December 31, 2005 [online], http://www.zonaeuropa.com/200512brief.htm#100 (retrieved July 12, 2006); and Rebecca MacKinnon, “Microsoft Takes Down Chinese Blogger,” RConversation.com, January 3, 2006 [online], http://rconversation.blogs.com/rconversation/2006/01/microsoft_takes.html (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[93] David Barboza and Tom Zeller, Jr., “Microsoft Shuts Blog’s Site After Complaints by Beijing,” New York Times, January 6, 2006 [online], http://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/06/technology/06blog.html?ex=1294203600&en=f785b99efa4cf025&ei=5090&partner=rssuserland&emc=rss (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[94] Jeremy Kirk, “Microsoft revamps blogging policy,” InfoWorld, January 31, 2006 [online], http://www.infoworld.com/article/06/01/31/74926_HNmicrosoftbloggingpolicy_1.html (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[95] Testimony of Jack Krumholtz Associate General Counsel and Managing Director, Federal Government Affairs Microsoft Corporation, House of Representatives Committee on International Relations Joint Hearing of the Subcommittee on Africa, Global Human Rights and International Operations and the Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific: “The Internet in China: A Tool for Freedom or Suppression?” February 15, 2006 [online], http://wwwc.house.gov/international_relations/109/kru021506.pdf (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[96] For the blog of Nina Wu, sister of Wu Hao, see http://spaces.msn.com/wuhaofamily/ ; for the blog of Hu Jia’s wife, Zeng Jinyan, see: http://spaces.msn.com/zengjinyan/ (both retrieved July 16, 2006).

[97] Original Chinese entry at http://wuhaofamily.spaces.msn.com/blog/cns!4004C8EDDE5C40F3!184.entry?_c=BlogPart; English translation at http://ethanzuckerman.com/haowu/?p=5228 (both retrieved July 12, 2006).

[98] Blogger Nancy Yinwang recently posted a comment on Nina Wu’s blog (at http://spaces.msn.com/wuhaofamily/blog/cns!4004C8EDDE5C40F3!346.entry?_c11_blogpart_blogpart=blogview&_c=blogpart#permalink) to announce that her blog (http://spaces.msn.com/nancy-yingwang) had been deleted. Translation at http://www.globalvoicesonline.org/2006/05/11/china-msn-censors-another-blog/ (retrieved July 14, 2006).

[99] “MSN Spaces rated the leading blog service provider in China,” People’s Daily Online, December 20, 2005 [online], http://english.people.com.cn/200512/20/eng20051220_229546.html (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[100] Clive Thompson, “Google’s China Problem,” New York Times Magazine.

[101] Michael Anti, “Wode taidu: Guanyu weiruan shijian he meiguo guohui keneng de lifa,” Anti Guanyu xinwen he zhengzhi de meiri sikao (Anti’s blog on Blog-city.com), January 14, 2006, http://anti.blog-city.com/1603202.htm; translation by Roland Soong at EastSouthWestNorth, January 15, 2006 [online], http://www.zonaeuropa.com/20060115_2.htm (both retrieved July 21, 2006).

[102] Chiu Yung, “Bushi MSN kechi, shi women diren yi deng,” Chiu Yung’s Web, January 4, 2006 [online], http://www.cantonline.com/index.php?op=ViewArticle&articleId=253&blogId=1 (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[103] About the research center see “Microsoft launches Search Technology Center in China,” CNET News.com, October 28, 2005, http://news.com.com/Microsoft+launches+Search+Technology+Center+in+China/2100-7345_3-5919207.html (accessed July 12, 2006). About the beta search launch see EricWan, “MSN Launches Chinese Search Beta,” Pacific Epoch, January 6, 2006 [online], http://www.pacificepoch.com/newsstories/50283_0_5_0_M/ (retrieved July 12, 2006); and “Beta Version of Chinese MSN Search Available,” China Net Investor reproducing Shanghai Times, January 15, 2006 [online], http://china-netinvestor.blogspot.com/2006/01/beta-version-of-chinese-msn-search.html (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[104] Declan McCullagh, “No booze or jokes for Googlers in China,” CNET News.com, January 26, 2006 [online], http://news.com.com/What+Google+censors+in+China/2100-1030_3-6031727.html?tag=nefd.lede (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[105] The explanatory page is on MSN’s Chinese search website at http://beta.search.msn.com.cn/docs/help.aspx?t=SEARCH_CONC_AboutSearchResults.htm&FORM=HRRE#4; For an example of a search result containing censorship notification see http://beta.search.msn.com.cn/results.aspx?q=高智晟&FORM=QBHP. For an example of a clearly censored search result without any block notification message see http://beta.search.msn.com.cn/results.aspx?q=天安门屠杀&FORM=QBHP (all retrieved July 12, 2006).

[106] Google Corporate Information, "Our Philosophy, No. 6: You can make money without doing evil," [online], http://www.google.com/intl/en/corporate/tenthings.html (retrieved July 27, 2006).

[107] Eric Schmidt, “Let more of the world access the internet,” The Financial Times, May 21, 2006.

[108] “Google defends cooperation with China: Unveil Chinese language brand name: ‘Gu Ge’ or ‘Valley Song’,” Associated Press, April 12, 2006.

[109] “Google to Open Research and Development Center in China,” Google corporate news release, July 19, 2006 [online], http://www.google.com/press/pressrel/rd_china.html (retrieved July 12, 2006). “Google Launches New Japanese, Chinese, and Korean Search Services,” Google corporate news release, September 12, 2000 [online], http://www.google.com/press/pressrel/pressrelease34.html (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[110] Jason Dean, “As Google Pushes into China, It Faces Clash With Censors,” Wall Street Journal, December 16, 2005 [online], http://online.wsj.com/article/SB113468633674723824.html (retrieved July 16, 2006).

[111] OpenNet Initiative, “Google Search & Cache Filtering Behind China’s Great Firewall,” Bulletin 006, August 30, 2004 [online], http://www.opennetinitiative.net/bulletins/006/ (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[112] For further explanation of the Google cache see http://www.google.com/help/features.html#cached. For an example of the Google cache for a Human Rights Watch webpage on China see: http://64.233.187.104/search?q=cache:eVMz-MuvpOMJ:www.hrw.org/asia/china.php+human+rights+watch+china&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1 (both retrieved July 12, 2006).

[113] OpenNet Initiative, “Google Search & Cache Filtering Behind China’s Great Firewall.”

[114]“China, Google News and source inclusion,” Google Blog, September 27, 2004, http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2004/09/china-google-news-and-source-inclusion.html (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[115] OpenNet Initiative, “Google.cn Filtering: How It Works,” blog, January 25, 2006, http://www.opennetinitiative.net/blog/?p=87 (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[116] Clive Thompson, “Google’s China Problem,” New York Times Magazine.

[117] Danny Sullivan, “Google Created EvilRank Scale To Decide On Chinese Censorship,” Search Engine Watch, January 30, 2006 [online], http://blog.searchenginewatch.com/blog/060130-154414 (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[118]Andrew McLaughlin, “Google In China,” Google Blog, January 27, 2006, http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2006/01/google-in-china.html (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[119] For an explanation of Google’s code of conduct see Google’s official investor website at http://investor.google.com/conduct.html (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[120] McLaughlin, “Google In China,” Google Blog.

[121] Hundreds of tests by one of this report’s authors in Beijing and Shanghai in November 2005 over a ten-day period from a variety of locales did not reflect the same level of difficulty accessing Google.com on Chinese ISPs. Numerous Chinese working in the IT industry expressed skepticism at Google’s claim based on their own experiences.

[122] McLaughlin, “Google in China,” Google Blog.

[123]See for example http://www.google.com/search?q=seven+wonders+of+india&btnG=Search&hl=en&lr=&c2coff=1 (retrieved July 12, 2006).

[124] Ibid. The link is to http://www.chillingeffects.org/dmca512/show.cgi?NoticeID=805 (retrieved July 12, 2006).