V. Recent Abuses and Continuing Impunity

“I have not seen any official being punished. And quite frankly, I don’t even try to get them prosecuted. My priority is to get my clients released while they are still alive.”

—Mian Abdul Qayoom, president of the Jammu and Kashmir High Court Bar Association, Srinagar267

Since 2002, government officials and senior military officers have made statements instructing the security forces that human rights abuses will not be tolerated. For example, the first statement from the Congress party’s Ghulam Nabi Azad after his appointment as chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir on November 2, 2005 (as part of a rotation previously agreed with its coalition partner, the People’s Democratic Party, or PDP), was that his government would not tolerate custodial killings by troops and police.268 Perhaps more important, Gen. J.J. Singh, the Indian Chief of Army Staff, reportedly told his troops that such deaths would not be tolerated because they negated all the good work done by the army.269 Perhaps most significantly, in May 2006, even Prime Minister Manmohan Singh told troops in Jammu and Kashmir, “It is possible and desirable that you should be firm but humane; effective and efficient; in control but unobtrusive.” He added, “You must be steadfast in your commitment to human rights and there should be zero tolerance for custodial deaths.”270

These are important messages that, if translated into action, could make a major difference in the human rights situation and help improve public trust in the government and security forces.

Since the 2002 state elections that threw out the administration of Farooq Abdullah’s National Conference party and brought PDP leader Mufti Mohammad Sayeed to power as chief minister, there have been some improvements on the ground. The number of new “disappearances” has significantly decreased; according to the Association of the Parents of Disappeared Persons they have dropped from eighty-one in 2003 to eighteen in 2005. The systematic use of warrantless searches as part of cordon-and-search operations for militants has been reduced. With a reduction in random grenade or sniper attacks by militants upon security posts, and perhaps because of better human rights training, the practice of storming neighborhoods after such attacks, setting fire to buildings, and randomly beating up residents has also decreased. This shows that political commitment can make a difference.

Yet the army and paramilitaries are not under control of the civilian authorities in Srinagar. As the security forces continue to try to crush the insurgency––and without a clear and unqualified commitment to reform from the leadership of the national government, the army, and the paramilitaries––serious abuses such as killings, “disappearances,” torture, and arbitrary and illegal detentions continue.

Alarmingly, the prevalence of impunity continues. Most alleged cases of abuse are not investigated. In the rare instances when they are, Human Rights Watch can find no cases resulting in public prosecutions or convictions of soldiers, paramilitaries, or police.271 Disciplinary measures within the Indian army, the CRPF, the BSF, or the police are also rare and lacking in transparency. In March 2006, Chief Minister Ghulam Nabi Azad told the Jammu and Kashmir assembly that since the insurgency began disciplinary action had been taken against 134 army personnel, seventy-nine members of the Border Security Force, and sixty policemen.272 However, the government has not provided any details, such as the nature of the crime, the name of the victim, the name of the accused, or dates, calling into question whether these cases really exist and, if they do, whether they have anything to do with human rights abuses or are just cases of ordinary crimes such as theft or corruption, or disciplinary problems such as fistfights or breaking of internal rules.

In short, Indian security forces continue to hide behind the shield of immunity provisions in Indian law and the lack of political will in New Delhi to address the critical human rights situation in Jammu and Kashmir.

In this chapter we list only cases after the November 2002 election of a state government that came to power promising improvements in the human rights situation. We believe that these cases require a thorough and independent investigation leading to appropriate prosecutions or disciplinary action. The police and other law enforcement authorities must act on their own to investigate serious abuses, and not simply wait for complaints from family members. Formal complaints are neither required nor often forthcoming because, as many families told Human Rights Watch, they are afraid or believe it is pointless.

These cases illustrate the scope of continuing abuses and the need for the government to fulfill its obligations under international law to fully investigate and prosecute serious violations of human rights. The government further must provide for the right to a remedy and reparations for the victims and their families, regardless of their status as militants or innocent civilians. It is also hoped that the human tragedies brought to light by these accounts will provide additional impetus for genuine government action.

A. Killings

“These people are like trained killer dogs. Once unleashed, it is difficult to keep them in check.”

—Senior police official speaking to Human Rights Watch about security forces operating in Kashmir273

The most alarming human rights problem in Jammu and Kashmir remains the high number of unlawful killings by security forces.274 During fighting between government forces and militants, the laws of war—specifically common article 3 to the 1949 Geneva Conventions and customary laws of war—apply. The laws of war prohibit attacks on civilians and attacks that do not discriminate between civilians and valid military targets. Civilians have been victims of fighting in which they were shot in the crossfire, but they have also been subjected to laws of war violations in which the security forces did not take all feasible precautions to distinguish between civilians and militants. The security forces have then often sought to claim that those shot were militants or civilians who died in crossfire.

Provoking the greatest local outcry have been cases of faked “encounter killings.” As in 2000 at Pathirabal (see Section IV above), in these cases the security forces are alleged to have fabricated a story about having killed a “militant” in self-defense or in battle when in fact the person was executed in custody.275 Common article 3 prohibits at all times murder, torture and other ill-treatment of civilians and captured combatants. Summary or extrajudicial executions also violate the right to life under international human rights law. According to Indian officials who spoke to Human Rights Watch on condition of anonymity, faked encounter killings are more likely to happen if a suspected militant is identified as a Pakistani, or as an important militant leader who might be a security risk if kept in jail, either because he might indoctrinate other prisoners or because there is a perceived danger of hostage-taking to secure his release. The case of the hijacking of an Indian Airlines plane from Kathmandu to Kandahar in 1999 to secure the release of Pakistani militants is often cited.276

In 2001, the U.S. government wrote:

Kashmiri separatist groups maintain that many such “encounters” are faked and that suspected militants offering no resistance are executed summarily by security forces. Statements by senior police and army officials confirm that the security forces are under instructions to kill foreign militants, rather than attempt to capture them alive. Human rights groups allege that this particularly is true in the case of security force encounters with non-Kashmiri militants who cross into Jammu and Kashmir illegally.277

So pervasive is the problem of faked encounters––not just in Jammu and Kashmir, but in other parts of India where security forces are engaged in containing crime or insurgencies—that the National Human Rights Commission has issued guidelines on investigating such incidents and punishing those making false claims.278 As Parvez Imroz, president of the Public Commission on Human Rights (a nongovernmental organization), says:

There are a number of cases where we believe disappeared persons have been killed in faked encounters. In fact, there are cases pending in the High Court but the judiciary has not been particularly productive, merely directing the state or police to investigate. Of course, despite court orders, the progress in such investigations is always slow.279

Such fake encounter killings might even be encouraged by the military command structure through decorations, gallantry citations or promotions of personnel credited for the death of militants. Such incentives may lead to abuses.280 Maj. Gen. V.K. Singh, a retired officer, has written in an essay in Military Law: Then, Now and Beyond:

Units involved in counter insurgency operations may fall to the temptations to show results, which in simple terms, translates into kills. Every dead militant is a feather in the cap of the commanding officer, leading to rewards such as decorations and unit citations. As a result, there is a danger that the Army units may begin to emulate the Police, and start staging “encounters.” It may be recalled that Mr KPS Gill used similar tactics to curb militancy in Punjab, when he was the [director general of police]. The Army was often co-opted in these operations, and learned the techniques at close hand.281

Officials routinely talk publicly about the “elimination of terrorists,” in language that may contribute to a sense among security forces that they have an assurance of not being held accountable for illegal acts of violence. For instance, in an interview with the Hindu, Chief Minister Ghulam Nabi Azad said that “those who come from across the border and indulge in killings of innocent people should not expect any mercy or concession. Our bullet is going to get those who are killing innocent people… and we are not going to budge even an inch from this position.”282

The circumstances around allegedly faked encounter killings are often in dispute. For instance, on July 5, 2005, Hizb-ul-Mujahedin commander Ghulam Mohiuddin Dar was, according to the army, ambushed and killed in an armed encounter. The army said it had prior information that he was in the neighborhood. Dar’s supporters, on the other hand, say that he was arrested by members of the Rashtriya Rifles when he was bathing in a stream around noon, taken into custody, and shot about five hours later in what troops falsely claim to have been an armed encounter in a forest.283 Human Rights Watch has been unable to verify either version of this incident. This is why credible, independent investigations are needed. Protection of witnesses is critical.

Another recent example of a disputed case is the death of Abdul Wali Khatana, Maulvi Mohammad Farooq, and Mohammad Farooq in Batgund Heepora village on January 17, 2006. Villagers told the Public Commission on Human Rights that the three men, who were associated with a local madrassah (Islamic school), were taken into custody four days earlier and later executed.284 The army said that the men were members of the Hizb-ul-Mujahedin and were killed in an ambush. According to army spokesman Col. V.K. Batra, Khatana had indeed been called for questioning by the 7th Rashtriya Rifles, but he left the army camp and went underground. According to the army the three militants were killed after an exchange of fire; a pistol and two rifles were allegedly recovered from the militants.285 The villagers refused to accept this version and held protest demonstrations until district authorities promised an inquiry.286

Two other cases investigated by Human Rights Watch are illustrative. According to an army report filed with the police, Mohammad Ibrahim Dar and Ishfaq Ahmad Rather were killed by the 2nd Rashtriya Rifles in Lawaypora in Srinagar in an armed encounter on September 29, 2005.287 Relatives of Mohammad Ibrahim, a Hizb-ul-Mujahedin commander, insisted that he had been arrested and then killed in a faked encounter. 288 So did the brother of Ishfaq Ahmad, another Hizb-ul-Mujahedin commander who was allegedly killed in the same encounter.289 It is difficult, as in most such cases, to establish exactly what happened, but Salima Ganai, Mohammad Ibrahim’s sister, said that when his body was handed over to the family, it bore signs of torture.

It was obvious to us that my brother had been tortured and then killed in a faked encounter. He had bullet wounds. But there were also cuts on his hands, between his fingers and on his wrists. There were these marks on his face that looked like cigarette burns. It seems to me that they killed him with great cruelty.290

While they want to know what happened to their brothers, both Salima Ganai and Ishfaq Ahmad’s brother, Altaf Ahmad, told Human Rights Watch that they did not believe a fair investigation was possible into the deaths.

Protests often occur when a local Kashmiri is killed. The official response usually is to offer an oral assurance of an inquiry, though these rarely happen. If such inquiries do take place, the findings are seldom made public. According to the Public Commission on Human Rights, of the seventy-three inquiries ordered since the new government was elected in November 2002 and up to December 2005, there is information available in only six cases.291 If any action is taken against those found responsible, that too is rarely made public. Human Rights Watch could find no instances in which there was a public prosecution leading to a conviction of those alleged to be responsible for faked encounter killings in Jammu and Kashmir.

In some cases the photograph of a missing Kashmiri turns up in the newspaper or police station as that of a dead “foreign militant” killed in an encounter. In such cases (some of which are described below), the family of the deceased may file a complaint or appeal for exhumation of the body to identify the victim and hold proper burial ceremonies. Frequently, however, the victims of extrajudicial execution by the security forces are suspected militants who are genuinely from Pakistan.292 When the individual is from Pakistan and has no relatives in Jammu and Kashmir state, complaints are rarely filed.

In this section we also discuss cases in which troops opened fire on people they believed mistakenly to be militants. In an interview with Human Rights Watch, the army spokesman in Srinagar classified these cases as an “error of judgment,” as opposed to deliberate murder, which he said would be an “error of intention.”293 However, errors of judgment occur too frequently in Jammu and Kashmir, where special laws such as the Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act provide troops with extraordinary powers to shoot to kill. For example, on February 23, 2006, even as the prime minister convened a discussion with Kashmiri groups to try and develop a consensus to end the conflict, in Handwara, four boys, one of them just eight years old, were shot dead by the army.294 The Kashmir valley erupted in rage, refusing to accept the army’s claim that the boys had died in crossfire. A judicial probe was belatedly ordered, but many Kashmiris have little faith in it. Instead, they fear that impunity will prevail.

International human rights standards call for a "thorough, prompt and impartial investigation of all suspected cases of extra-legal, arbitrary and summary executions,” including cases where complaints by relatives or other reliable reports suggest death in such circumstances.295 The Indian government’s investigative practices do not meet accepted international standards in alleged extrajudicial killings, including the right of the deceased’s family to be informed and have access to the investigation, and for the publication of a report “within a reasonable period of time” on the scope and findings of the investigation.296

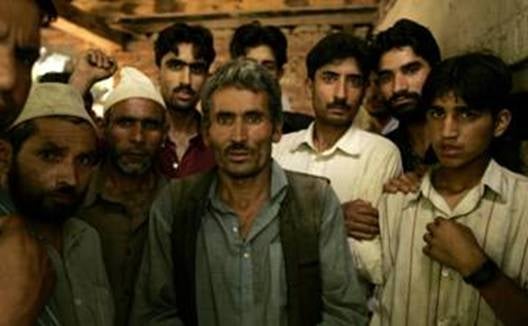

Killing of three youths in Vilgam, Kupwara, July 24, 2005

Bilal Ahmed Sheikh, Shabir Ahmed Shah, Wasim Ahmed Wani, and Manzoor Ahmed Shah were attending the wedding festivities of Manzoor Ahmed’s elder brother. Drummers had been brought in and the four teenagers danced all evening. Close to midnight, they slipped out and walked a short distance to the outskirts of the village, where hidden from disapproving adults, they lit a cigarette.

The groom, Farooq Ahmed Shah, remembers the sudden sound of gunfire. Everyone was shocked. Earlier, the groom’s family had gone to the army camp near the village, invited troops to the wedding and informed them formally that the festivities would go on late into the night. He wondered why the army was conducting operations so close to the village.

As soon as the firing stopped, the villagers scurried home to safety. The parents of the youths worried about their sons, but assumed that they had decided to stay with a friend. At about 4 a.m. soldiers arrived at the home of Farooq Ahmed Shah. “They said my brother had been injured and asked my father to come with them to the hospital.”297

The villagers began to gather. By then, the other youths had already been discovered as missing. At around 9:30 a.m., the village headman returned with some soldiers and told the villagers that the army had opened fire, claiming to have mistaken the four teenagers for militants. Three of them, Bilal Ahmed, Shabir Ahmed, and Wasim Ahmed, had been killed. Manzoor Ahmed was in hospital with critical injuries.298

The army apologized for the incident and offered 300,000 rupees (U.S.$6,500) in compensation for each of the three deaths. In an interview with Human Rights Watch soon after the incident, the army spokesman in Srinagar said there would be an inquiry: “We have to learn from this incident. We are already in the process of reviewing our operating procedures. We will see who was in charge and if there was scope for the commander to exercise restraint.”299

After the inquiry, according to the same spokesman, the soldier who had opened fire received a warning, but the details have not been publicized. The spokesman told us, “But you must try and understand the difficulties of our troops during such operations. We found that there had been two militant ambushes in the area earlier. In both cases, there were army casualties while the militants escaped. The men made an honest mistake when they opened fire this time. They did not expect the boys to be hiding and smoking.”300

The mother of Bilal Ahmad Sheikh, one of the three Kashmiri teenagers mistakenly shot and killed by Indian Army soldiers in Vilgam, weeps days after the shooting. The three boys had stepped outside a wedding reception to smoke cigarettes when Indian Army soldiers mistook them for Islamist militants, even though the soldiers were informed of the village festivities. Villagers are required to carry flashlights or lanterns after sunset when walking outdoors in the Kashmir valley, but the boys were not carrying either. The Indian Army has apologized and offered compensation to the families.

© 2005 Robert Nickelsberg

Killing of Parvez Ahmad Dar, Kangan, Pulwama, July 20, 2005

Just four days before the incident at Vilgam, sixteen-year-old Parvez Ahmad Dar went with his father and uncle to open irrigation channels into their paddy field in Kangan village. Water is in short supply and villagers take turns to use the precious resource. While returning, Parvez Ahmad fell behind his father and uncle, who walked ahead carrying an oil lantern, a rule at night in rural Jammu and Kashmir to distinguish villagers from militants, who tend to use flashlights. According to Kabir Ahmad Dar, the victim’s uncle:

We heard firing and we went into a neighbor’s hut for safety. We did not know where the boy was, but we thought he must have run to the village. At 6 a.m. the army said there was a crackdown and called everyone outside. There was a major with the soldiers and he said there had been crossfiring. We said there was no crossfire. The firing had come from only one side…. We wanted to go search for my nephew who was not in the village. The major refused to let us go…. He said that my nephew was a militant and had been shot while running away. When we started shouting then he finally admitted that a child had been killed by mistake.301

The villagers ran to the field and found Parvez Ahmad lying there. He had been shot in the back. The villagers insist that the troops had opened fire without provocation. But Lt. Gen. S.S. Dhillon, the commanding officer of the 15th Corps, said that Parvez Ahmad was killed in “retaliatory fire” and that there was “a big difference between the July 20 and July 24 incidents.”302 An inquiry was promised after protests by the villagers, but if it actually took place the results have not been made public.

Killing of Mohammad Ramzan Dar, Gundipora, Budgam, June 6, 2005

According to his family, Mohammad Ramzan Dar suffered from a psychological disorder and was therefore unfit for regular jobs. The village had appointed him caretaker of the local mosque, to help support his family. Mohammad Ramzan woke as usual at 3:30 a.m. on June 6, 2005, so that he could be in the mosque in time to call to morning prayers. Many of the villagers woke up soon after because they heard gunfire. As is usual, everyone stayed inside as long as the firing continued so that they would not be caught in crossfire.

In the morning there was no call to prayer, but some of the villagers went to the mosque on time. Outside the mosque, they found the body of Mohammad Ramzan. He had been shot in the head and chest. After villagers protested, police and district authorities promised an inquiry. According to Mohammad Ismail Dar, brother of Mohammad Ramzan, the authorities later said that the killing was a mistake:

We were told that the 34th Rashtriya Rifles had planned an ambush in the area. My brother was not right in the head and he used to talk to himself. The soldiers heard voices and opened fire thinking that there were militants near the mosque.303

The family received compensation. Mohammad Ismail Dar noted the connection between the wide powers of the security forces to use lethal force and the tragedies that ensued:

I am willing to believe that this incident was a mistake. But how can the army go around shooting people like this? These mistakes should not happen. It is because, in Kashmir, the army can shoot whom they like.304

Killing of Zulfiqar Ali Khan, Mohammad Rafiq Mattal and Feroz Ahmad Bhat, April 21, 2005

Zulfiqar Ali Khan left his home in Galiban village around noon on April 21, 2005, after walking his daughter to school. He went to Baramulla town, about fifteen kilometers away, to talk to his father’s doctor and run some errands related to his apple trade. Around 4 p.m. he met a neighbor who was also in Baramulla and said that he was soon heading back home. Meanwhile, he had bought vegetables and, meeting a local constable, sent the bag of vegetables back home with him because the constable was going back to the village immediately.

Later that day, according to a report lodged by the army with the police, Zulfiqar Ali Khan crossed the Line of Control into Pakistan-administered Kashmir, and then back again that night into Jammu and Kashmir state with other militants. The report alleged that they were intercepted and killed in an armed encounter near the Choroonda post in Uri, about sixty kilometers from Baramulla town.

Zulfiqar Ali Khan’s family say that the army is lying. His father, Sardar Kabir Ahmed Khan, says that villagers near Choroonda told him that they saw a car with darkened windows drive past at around 7 p.m. Soon afterwards they heard shots. Sardar Kabir Khan believes that the security forces abducted two other men, Mohammad Rafiq Mattal and Feroz Ahmad Bhat, before picking up Zulfiqar Ali from Baramulla, drove to Choroonda, and then made them walk near the border and opened fire, killing them. Sardar Kabir Khan asks some basic questions:

How, between 4 p.m. and midnight can someone go across the border, meet up with militants, and come back? There are so many soldiers in the area. None of them could see him? My son had been injured in a bomb blast attack some weeks before he died. He could not walk very well. Yet, we are supposed to believe he just strolled across a heavily mined border which is fenced and guarded. And lastly, you should have seen my son’s body. His boots were polished. His clothes were ironed. This, even though he had allegedly trekked across the border. Twice. I think it is obvious. My son was murdered.305

Zulfiqar Ali Khan had been arrested for militancy in 1994, detained for four years, and released in 1998. Since then, his father says, Zulfiqar Ali Khan had stopped his association with militants. According to Zulfiqar Ali Khan’s brother in law, Fayaz Ahmad: “[Zulfiqar] was not really interested in militancy even earlier. But his father was a politician associated with the Congress and National Conference. Militants wanted to kill him. At that time, the militants were here all the time. His sons used to associate with the militants so that they would not kill their father.”306

Zulfiqar Ali’s younger brother, Firdaus Ali Khan, was killed by the army in 1993. Their father said sadly:

The army came to his shop and said, “You have been feeding militants.” Then they walked him down the hill, shot him and walked away. At that time, there was no choice but to feed militants. They had guns. Also, they used to threaten to kill me. But the army brutally killed my boy. Now, they have killed my older son. My home is now empty.307

According to the army, Zulfiqar Ali was a guide who helped militants cross the Line of Control. The army claims that on April 21, 2005, he deliberately sent vegetables home with the village constable to establish his presence in Baramulla town. Then he quickly drove up to the village near the border and crept across. At night, he was coming back with a group of militants when he was killed in an armed exchange.308

Disputing this version of events, Sardar Kabir Ahmad Khan demands to know why his son died:

I want them to tell me why they killed him. Why they lied and said he had come from Pakistan. Why do they have to kill?… I think they took my son into custody in Baramulla and then killed him in a faked encounter in the border. I don’t understand this. If they really thought my son was a militant, they could have jailed him. Why kill him? His killers should be punished.309

Three other men were killed in the same encounter in which Zulfiqar Ali was killed. Their relatives also insisted to Human Rights Watch that the men had been killed in a faked encounter. One of the men, Feroz Ahmad Bhat, had been identified by the army as a Pakistani militant and buried. His father, Habibullah Bhat, recognized his son from a police photograph of the corpse and sought an exhumation. He said that, “At the police station, they said that the army had delivered the bodies of militants killed at the border. They said that only one was a Kashmiri. The others were Pakistani and had already been buried. They showed us the picture of the dead Pakistani militants. I identified my son from the picture.”310 Habibullah Bhat said he tried to file a police complaint so that these deaths could be properly investigated, but was refused. “At the police station they say they cannot file a report because my son was a militant and killed in an encounter. They say that I have no case for complaint.”311

Killing of Nazir Ahmad Dar, December 29, 2004

The Border Security Force stopped a bus at a checkpost in Kharpora village on the morning of December 29, 2004. As is usual, the passengers were asked to disembark for routine checking. Two militants traveling in the bus opened fire. One soldier was injured. Other soldiers at the checkpost opened fire in response. In the exchange of fire one militant was killed while the other escaped.

According to Nazir Ahmad Dar’s brother-in-law, also called Nazir Ahmad Dar, when villagers heard the gunshots, they ran away in fright. Nazir Ahmad and his neighbors began to run as well. As they passed the road where the bus had been stopped, a stray bullet hit Nazir Ahmad in the leg. He still continued to limp to safety. He was stopped by BSF guards who were checking identity cards to ensure that the escaped militant was not hiding among the villagers. When Nazir Ahmad arrived, he too pulled out his identity card. His brother-in-law said there were some neighbors present who saw what happened next:

Nazir Ahmad was walking slowly. The BSF men asked him why he was limping. He told the soldiers that he had been hit by a bullet as he was running past the bus. But the soldiers must have thought that he was the escaped militant because they immediately pointed their guns at him. Our neighbor, who was standing there, heard Nazir Ahmad say, “I am not a militant. You can arrest me and check.” Instead, they opened fire and killed him.312

The villagers went to the local police station. According to the brother-in-law, several eyewitnesses said that they had heard Nazir Ahmad offer to surrender. That night, members of the BSF came to the village. They met the eyewitnesses and the family. They visited the victim’s sister and brother-in-law as well:

They said, “We will settle with you. Change your statement to say that he was asked to surrender but did not stop.” They offered money. But I said that my brother-in-law has small children. If we take your money, tomorrow the militants will come and ask why we settled. They will kill the children.313

The BSF soldiers repeatedly returned to the village. Nazir Ahmad’s relatives were summoned to their camp. So were the eyewitnesses. Soldiers pressured them to change their statements. Finally, the villagers complained to the local police. That appeared to have some effect. The summons and visits by the BSF stopped. About two weeks later, according to the brother-in-law, that unit of the BSF was shifted out of the neighborhood. However, he does not know whether those responsible for Nazir Ahmad’s death were ever punished. No eyewitness or relative was ever called to testify in any court of inquiry about the incident. The district authorities paid the routine 100,000 rupee (roughly U.S.$2,300) compensation handed out in cases of death due to crossfire. As far as anyone knows, the case is now closed.

Killing of Abdul Rashid, October 17, 2004

Around midnight on October 16-17, 2004, security forces arrived at the home of thirty-six-year-old Abdul Rashid. His wife, Taja Bano, told Human Rights Watch:

They knocked on the doors and then asked for some tea. Four men walked inside. They were in uniform and carrying weapons. But they had black cloths tied around their faces. There were others outside

The family does not know whether the security forces belonged to the army, the paramilitaries, or the police (they were told by neighbors that the men belonged to the Special Operations Group, SOG, a counter-insurgency unit of the state police). The next day, villagers found a body lying near the road and some of them identified it as Abdul Rashid. He had been shot.

The local police station handed Abdul Rashid’s body to his relatives. His father filed a police complaint alleging that he had been murdered by security forces. The local police certified that Abdul Rashid, a laborer and father of seven, had no links with the militants. The family was then paid compensation of 100,000 rupees.

Abdul Rashid’s family believes that the security forces killed him because his wife’s brother, Mohammad Yusuf Sheikh, was a militant. Taja Bano said that Mohammad Yusuf did not keep in touch with his family, but the security forces were unwilling to believe this:

The army and police had come to the house many times before this. They wanted us to tell Mohammad Yusuf to surrender. How could we do anything? My brother did not meet us.315

The family had initially wanted to file a lawsuit against the police, so that Abdul Rashid’s murderers could be prosecuted. But then they decided against it. Says Abdul Rashid’s mother, Saja Bano: “We are poor. My son is dead. I was scared that they would come and kill my grandson as well.”316

She had good reason to fear further violence from the security forces. Her daughter-in-law says that after Mohammad Yusuf had joined the Hizb-ul-Mujahedin in the late 1990s, the security forces would often harass his brother, Bashir Ahmed Sheikh, about Mohammad Yusuf’s whereabouts. Taja Bano recounted:

They used to come and say that Mohammad Yusuf must have visited us. Or that we knew where he was. Or that he had hidden weapons in the house. But it was all untrue.317

According to Taja Bano, Bashir Ahmed “disappeared” on February 17, 2003. His body was later handed over to the family with bullet wounds. She blames the security forces for his death, saying that some neighbors had seen Bashir Ahmed being taken into custody by security forces in Srinagar.318 In June 2005, Taja Bano heard rumors that Mohammad Yusuf Sheikh had been killed in an armed encounter. She does not have any details.

Killings of Syed Yaseen Shah and Mohammad Anwar Shah, April 20, 2004

In March 2004, Mohammad Anwar Shah, a Muslim cleric, brought his ill mother from their mountain village in Chootwaliwar, Gandherbal, to Srinagar to see a doctor. While he left his mother with his sister, Mohammad Anwar stayed with his cousin, Syed Yaseen Shah, also a cleric, who worked at a Srinagar mosque.

On March 28 the two men left Syed Yaseen Shah’s house in the morning. According to Syed Yaseen’s wife, they had fixed an appointment to discuss Mohammad Anwar’s mother’s case with a Srinagar doctor. They left saying they would be home for lunch. They never returned.

The family contacted the police and filed a missing persons complaint. Three or four times, the family was summoned for identification of unknown corpses, most of them militants killed in fighting, but they were not their missing relatives.

An acquaintance told Syed Yaseen’s wife that the two men had been seen being arrested near Srinagar’s Iqbal Park by security forces. So their relatives went to various army camps asking if the two men were in custody, but to no avail. Says Mohammad Anwar’s brother, Syed Mohammad Ismail Shah: “We searched everywhere. For three months, we were running from here to there.”319

In June 2004, the family heard about the death of two militants in Lolab on April 20, 2004. In a police report, the 18th Rashtriya Rifles claimed to have killed two foreign militants, whom they named as Abu Faisal and Jaffar Ali, in an encounter.320 Both bodies had been buried in Lolab by the Lalpur police. Although the names are not mentioned, the army website lists the killing of the two militants, along with a list of weapons that were recovered.321

The family went to the Lalpur police station, where they were shown photographs of the dead “foreign” militants. The dead were their relatives: “Abu Faisal” was Mohammad Anwar, and “Jaffar Ali” was Syed Yaseen.

Mohammad Ismail told Human Rights Watch that he then appealed to the district magistrate, asking for exhumation of the bodies so that proper burial ceremonies could take place. A week later, the bodies were exhumed in the presence of local police and government doctors. Relatives identified both bodies, which were consequently handed over to be buried in the family graveyard.

Mohammad Ismail told Human Rights Watch that Syed Yaseen Shah had joined the militants in 1990, had returned from training in Pakistan in 1993, had been arrested in 1994, and released four years later. He claims that his cousin had no militant connections at the time they were killed. Syed Yaseen Shah was thirty-five when he died, married with three children. Mohammad Anwar Shah was twenty-eight when he was killed. He was sickly, having needed surgery in 2001 for a stomach ailment, and, according to his brother, was never part of any extremist group.

The family does not want to pursue the prosecution of the soldiers who claimed to have killed two foreigners in an encounter. They are only relieved that the bodies were returned to them and were properly buried. They expect no compensation. According to Mohammad Ismail:

In the official records, the bodies are that of some foreign militants. My brother is still a “disappeared.” How can I claim compensation? If I try to do anything, they will take his body away. At least now he is resting in the family graveyard.322

Killing of Zohar Ahmad Lone, Budgam, October 4, 2004

On October 4, 2004, seventeen-year-old Zohar Ahmad Lone and four others from his village were summoned by soldiers belonging to the 35th Rashtriya Rifles. They were taken to the next village, Naslapora, where two militants were holed up in a house. The house had been surrounded by troops who were calling out to the militants, asking them to surrender. Zohar Ahmad and the others were then told to walk up to the house and ask the militants to surrender. As soon as they reached the door, the militants opened fire. One of Zohar Ahmad’s friends was injured and fell to the ground. Frightened, Zohar Ahmad turned around and started running away. Some soldiers standing at the back opened fire, probably mistaking him for one of the militants, and killed him.

Soldiers then took Zohar Ahmed’s body to the local police station and said that Zohar Ahmad had been killed in crossfire. The operation continued, and the two militants were killed.

The government paid compensation to the family, as is the norm in the case of death in crossfire. Zohar Ahmed’s father, Ghulam Mohammad Lone, told Human Rights Watch that he did not want to pursue a case to prosecute the soldiers who had deliberately placed his son at risk: “What is the point? Nothing will happen and instead the army will be angry with me.”323

Killing of Abdul Hamid Ganie, Gandherbal, September 12, 2003

On September 11, 2003, several police officers belonging to the Special Operations Group came to the home of Abdul Hamid Ganie, a former militant who had been appointed as a special police officer (a scheme to generate employment by informally hiring Kashmiris, particularly militants who have surrendered, into the police force to do administrative work or man checkposts).324 According to his brother, Abdul Rashid Ganie, Abdul Hamid told his wife before leaving that the officers needed him for a police operation.

The next day, the SOG handed Abdul Hamid’s body to the local police station and filed a report, claiming that Abdul Hamid was a militant who had agreed to help the police locate weapons hoarded by his group, but on the way an exchange of fire with armed gunmen had broken out and Abdul Hamid had been killed in the crossfire.325

Abdul Rashid Ganie told Human Rights Watch that he found bruises and strangulation marks on his brother’s body. He claims that Abdul Hamid was tortured and then murdered because of a quarrel Abdul Rashid had with a local official from the SOG about money. This man, accompanied by his colleagues, had come in search of Abdul Rashid, but he was not home. The next day they picked up his younger brother, Abdul Hamid, instead.

They wanted revenge and so they tortured my brother and then they killed him. His ribs and legs were fractured and there was a red mark around his neck. They must have strangled him.326

After protests by villagers, the local administration ordered an inquiry on October 1, 2003. The inquiry learned from a dental surgeon, Dr. Roof Jeelani, that members of the SOG had forced him to sign on the death certificate that the cause of death was bullet injuries leading to loss of blood. He testified in writing on January 6, 2004, that he was not trained to perform autopsies and had been “compelled by [the SOG] and the policemen who were more than 30 members.”327

Abdul Hamid’s body was exhumed for autopsy and several villagers and eyewitnesses were interviewed. Based on the resulting report, on March 1, 2004, the district magistrate wrote to the superintendent of police in Gandherbal that “the findings of the enquiry reveal that the death… took place while in the custody of SOG personnel, Gandherbal.” Saying that SOG personnel had claimed that Abdul Hamid died while accompanying a raiding party, the report said that “this aspect had been found doubtful during the enquiry,” and the magistrate instructed the superintendent of police to initiate proceedings against the “delinquent officials.”328

The district authorities instructed the police to lodge a complaint of murder against thirteen men, but as of February 2006 it did not appear that any charges have been filed.329 All were still employed by the state police. They have, according to family members, threatened them on several occasions to withdraw the case. As Abdul Rashid told Human Rights Watch: “They say, ‘It has been one year. Look. Nothing happened to us. But you have seen what we did to your brother. We will do the same to you and to your children.’”330

Killing of Farooq Ahmad Khan, September 3, 2003

On August 19, 2003, Farooq Ahmad Khan, who worked in a Srinagar bakery, was taken into custody along with his employer, Bashir Ahmed Sofi, by soldiers from the 18th Rashtriya Rifles. According to Farooq Ahmad’s father, Bashir Ahmed Sofi had quarreled with another employee who had possibly provided false information about Bashir Ahmed to the security forces. The father thinks Farooq Ahmad was taken because he was in the wrong place at the wrong time.331

According to Farooq Ahmad’s father, Bashir Ahmed was released a few hours after being arrested. He said he was asked for information about militants operating in the area, and that he had been separated from Farooq Ahmad soon after arrest. When Farooq Ahmad failed to return, Bashir Ahmed informed Farooq Ahmad’s relatives of his arrest. Farooq Ahmad belonged to a poor farmer family of ten from a border area of Jammu and Kashmir. Wali Mohammad Khan, Farooq Ahmad’s father, rushed to Srinagar, where he went to local police stations to ask about his son, but he was unable to locate him. With hardly any money to pay lawyers, bribe officials, or survive in a big city, the family was forced to postpone a daughter’s wedding.

Some villagers suggested that Farooq Ahmad’s father contact the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP). On January 15, 2004, the APDP helped Wali Mohammad file a habeas corpus petition. The army denied having arrested Farooq Ahmad.332

Meanwhile, a relative gave Wali Mohammad a September 3, 2003 copy of the Urdu-language newspaper Al Safa, which carried a news report that one Imtiaz Ahmad, a Pakistani militant from Kala Khan in Punjab, had been shot in an “encounter.” The article said that:

One militant, a suicide bomber, was killed by BSF 57 BN [57th Battalion of the Border Security Force] yesterday at Ishpur, Nishat, Srinagar. He was asked to stop when he behaved suspiciously but instead, he started firing at BSF officials. In retaliation BSF personnel also opened fire resulting in his death…. A rifle and three hand grenades were recovered from him.333

According to Wali Mohammad, the accompanying photograph of the killed militant was that of his son, Farooq Ahmad.334

I saw the photograph only in October and went to the police station. I showed them the photograph and told them it was my son. The police officer said that this man was a fidayeen [suicide bomber] from Pakistan called Imtiaz. I said that my son is not called Imtiaz but this is his picture. 335

Farooq Khan’s body had been handed over by the police to a voluntary group in Srinagar that performs the funeral rites of unidentified militants. With the APDP’s help, Wali Mohammad filed a petition in the High Court asking for the body to be exhumed.336 On October 12, 2004, Wali Mohammad’s plea was turned down by the High Court. His lawyers appealed. Finally, on January 3, 2005, the district magistrate ordered the exhumation of the body for DNA sampling to establish its identity. The exhumation took place on April 11, 2005. The forensic results of the DNA test were still being awaited ten months later, as of February 2006. Parvez Imroz of the APDP and Wali Mohammad’s lawyer said they would file an appeal in the Indian Supreme Court.337

Killing of Mohammad Bashir Ahmed Sheikh, Rustan Beerwah, Budgam, July 17, 2003

After Mohammad Yusuf Ahmed Sheikh became a militant in 1990, his family was constantly harassed by security agencies. His two younger brothers, Mohammed Bashir Ahmed Sheikh and Mohammed Tariq Ahmed Sheikh, were often taken away to illegal detention centers in police and army barracks for interrogation. In 1996, Tariq Ahmed was beaten so badly that he lost his hearing. In August 2000, when security forces raided the family home yet again looking for information about Yusuf Ahmed, his other brother, Bashir Ahmed, climbed into a tree from the third-story window of his house to escape the possibility of another round of torture and interrogation. He fell and was badly injured, partially losing the use of his hands. A hospital report notes that he was admitted on August 18, 2000, with head injuries.338

In July 2003, Bashir Ahmed was once again summoned for interrogation by the Special Operations Group of the state police. He was told to come to the Harinawaz camp. He took a bus there on July 10, 2003. He then “disappeared.” His family contacted the police and placed a notice in the local papers. According to his mother, Fatima Begum, a week later someone from Batamalloo, a neighborhood in Srinagar, contacted the family to say that he had seen security officials arrest Bashir Ahmed at the Batamalloo bus stop on July 10, 2003, as soon as he got off the bus.

According to his mother, when they first contacted the police a constable on duty told them that Bashir Ahmed was in custody and that he would be released. However, after that first day, officials at the Harinawaz camp denied that Bashir Ahmed was in police custody and said that he had not been summoned to the camp. Fatima Begum has no evidence that Bashir Ahmed had actually been called to the camp. He had simply come home and said that he had been asked, once again, to report to the police.

Following Bashir Ahmed’s “disappearance,” his relatives and neighbors held protest demonstrations. The local police promised to inquire. On the afternoon of July 18, 2003, they told the family that Bashir Ahmed had been killed in an armed encounter in Gandherbal, near Srinagar. As is the law, the Rashtriya Rifles had filed a report at the nearest police station in Gandherbal, reporting an armed encounter on July 17, 2003, in the surrounding forest in which a militant had been killed; arms and ammunition were recovered after the killing. They claimed that the militant was Bashir Ahmed. His mother disputes this as impossible:

Bashir Ahmed was handicapped after he fell from the tree. His hands were almost useless. He could barely hold a cup of tea and could certainly not carry heavy weapons. The army is lying.339

Fatima Begum went to Gandherbal, where she identified the body. Bashir Ahmed’s body was handed over to his family. Relatives and neighbors held more demonstrations insisting that Bashir Ahmed had been killed in a faked encounter. To pacify them, the district official orally promised the protesters that there would be an inquiry. On July 19, 2003, a Special Operations Group officer in Budgam, Mushtaq Ahmed Bukhari, told journalists that Bashir Ahmed had not been taken into police custody. But he also agreed that Bashir Ahmed was not a militant. “I know he was innocent but his elder brother is a militant,” he said.340

Fatima Begum and other relatives went several times to the district headquarters to ask about the promised inquiry, but they were unable to obtain any information. Meanwhile, members of a local unit of the Special Operations Group visited her home repeatedly and threatened her and her family. Says Fatima Begum:

The police used to raid our house all the time. They even hit me when I protested. I even went to Mehbooba Mufti [President of the PDP] and told her, “Please, blow us up with explosives, but put an end to this.”341

In despair, the family has decided not to pursue the case. Fatima Begum explained to Human Rights Watch:

The police already said he is a militant. They claim he had weapons and fired at the army. What can we do about him now? We just hope that the security forces leave us alone.342

Killing of Javed Ahmad Magray, Nowgam, May 1, 2003

Javed Ahmad Magray, a seventeen-year-old student, was studying in his room late at night when his mother last saw him. The following morning, he was missing. His family initially thought that he had left for school early. But his teacher reported him absent. They then assumed he was at the mosque. But when neighbors returned from morning prayers, they said that he had not shown up there. By then neighbors had gathered. Some of them said they had heard gunshots the previous night. When they and the family went outside to the road, they found blood stains and a tooth. The crowd immediately began to shout slogans, assuming the worst.

According to the district magistrate’s inquiry report, Javed Ahmad’s father, Ghulam Nabi Magray, testified that “the army officer in charge of the area came before the mob and stated that the deceased Javed Ahmad Magray is in their custody and asked we people to come along, so that we can meet him at the Army Camp near my house.”343 At the army camp in Soeting, the official told them to contact the Nowgam police station. At the police station, the family learned that an injured “militant,” who had bullet wounds to his legs, shoulders, and mouth, had been brought to the police station at around 2:30 a.m. by Lieutenant Verma of the 119th Assam Regiment, and had been taken to hospital. The “militant” did not survive his injuries. When his relatives rushed to the hospital, the Sher-e-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, they identified the body as Javed Ahmad Magray.

According to the district magistrate’s August 2003 report, a copy of which was obtained by Human Rights Watch, relatives and neighbors of Javed Ahmad, his teachers, the inspector of the Nowgam police station, and representatives of the army took part in the investigation. Nissar Ahmad Shah, chief of the Nowgam police station, deposed that on May 1, 2003, at 2:30 a.m., Lieutenant Verma of the 119th Assam Regiment from the Soiteng Camp arrived at the police station with a written report. According to Nissar Ahmad’s testimony, the army reported that “their party was on patrol of the area and at 0030 hours four persons opened fire and on retaliation one militant was wounded and the other three taking benefit of heavy rains and darkness succeeded in running away.”344 A pistol and some bullets were reportedly recovered and handed over to the police. The police registered a First Information Report (FIR) based on a written report from Major Vastavo of the 119th Assam Regiment and sent the injured militant to hospital. Shah also testified that the police station had no record that Javed Ahmad was involved in “anti-national activity or militancy.”345 The report states that the district magistrate met with Javed Ahmad’s teachers, all of whom testified that the boy was a regular student and that there had been no complaints about militant activity against him.

After recording the statements of neighbors, teachers, parents and police, the magistrate then sent a questionnaire to Major Vastavo. In his response, Major Vastavo said that Javed Ahmad had been wounded in an armed encounter. He also said the patrol party involved in the encounter had been led by Subedar Surinder Sinha of the 119th Infantry Battalion of Assam Regiment. In response to another question, Vastavo said that the army had not received any adverse reports about Javed Ahmad before the incident. In response to questions from the magistrate about the lack of any bullet marks in the area to establish an exchange of fire with militants, the major claimed that “troops of the unit being trained left no mark of firing at any building around the location of the incident,” and that it was not a case of heavy and indiscriminate firing.346

The magistrate then called Subedar Surinder Sinha to record his statement. Although summoned twice, he failed to show up. The army, in a letter to the magistrate, said that Subedar Sinha’s unit had been moved and suggested that further correspondence should be sent to another army address. A subsequent letter duly sent was returned undelivered after sixteen days, leading the magistrate to conclude: “This clearly indicates that the said Subedar on one or the other pretext is unnecessarily delaying to get his statement recorded.”347

The magistrate’s report states:

From the reports/statements/documents and statements of witnesses, I am of the opinion that the deceased was reading in the ground story of his residential house during night hours. The residential house being on the road, the patrolling party headed by Subedar Surinder Sinha of 119 Bn of Assam Regiment dragged the boy out of the window… for keeping the light on and fired at him on the road, afterwards informing his superior officers who took the deceased person to the police station in a critical condition and registered the FIR. The deceased boy was not a militant nor involved in anti-national activity as per the report of the SHO [station house officer] and even the concerned army. The deceased was killed without justification by Subedar S. Sinha and his army men. Being head of the patrolling party, the said Subedar managed to go away from Srinagar and did not respond to letters deliberately though he was aware of everything.348

Javed Ahmad’s father told Human Rights Watch that he has received no information on what action has been taken by the government against Subedar S. Sinha and his superior officers.349 According to the Public Commission on Human Rights, the state government was unable to initiate a criminal prosecution because it failed to receive permission from the central government as required under Section 6 of the Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act.350

In an interview with Human Rights Watch, Col. Arun Marya, a human rights officer at Srinagar’s army headquarters, said that the army never acts without prior information and that Javed Ahmad must have been secretly operating as a militant, without the knowledge of his family and neighbors.351 In spite of the district magistrate’s conclusion, the army continues to list the killing of a militant called Javed Ahmad Magray on its website.352

B. “Disappearances”

“If he is alive, give me news of him. If he is dead, give me his body.”

—Statement of a “half widow,” the wife of a “disappeared” man, August 2005

“Disappearances” occur when people are taken into custody and authorities then deny all responsibility or knowledge of their fate or whereabouts.353 There have been so many “disappearances” in Kashmir that there is now a term for women with missing husbands: they are called “half widows.”

Most half widows are left to the mercy of relatives as they wait for news. Many end up destitute.354 But news often doesn’t come, as it is likely that a significant number of the “disappeared”—some of whom have been missing since the early 1990s—have been killed in custody.

Since the beginning of the insurgency, thousands of Kashmiris have gone missing. Of course, not all persons who go missing in Kashmir are victims of “enforced disappearance” by the security forces: some have left without telling their family or friends, often to join the militants, or simply to find jobs. Tellingly, however, the problem of “enforced disappearance” in Jammu and Kashmir is so widespread that Human Rights Watch learned of certain persons listed as “disappeared” who had actually gone away voluntarily to find jobs in other cities, but whose relatives had immediately assumed they were victims of “enforced disappearance.” Consequently, with such instances of erroneous reporting, substantial controversy remains about the problem’s exact prevalence. But as Human Rights Watch has reported in the past, “enforced disappearance” by troops has been widespread since the early years of the conflict. The problem has been so pervasive that it was a major issue in the 2002 state assembly election campaign: The PDP’s Mufti Mohammad Sayeed promised that, if elected, he would investigate all cases of “disappearances.” His party won the election.

In Jammu and Kashmir, the “disappeared” are often initially held in army or paramilitary camps or in interrogation centers run by police specially deployed in counter-insurgency operations, making it virtually impossible for relatives and lawyers to locate or gain access to them.355 When a person goes missing, relatives often go to the camps of the security forces––the army and paramilitaries based in Jammu and Kashmir––to search for the missing person. If the person is not released or is not produced before a magistrate, relatives go to the police to report that the person is missing. They also often go to the courts for a writ of habeas corpus to be issued ordering the authorities to produce the person in court. In most cases the army or other security forces claim that they do not have the person in their custody.

Efforts of Chief Minister Sayeed to confront the problem of disappearances, along with the determined efforts of the Srinigar-based Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) and others in civil society, appear to be making a difference. According to the APDP, the number of new enforced disappearances dropped from eighty-one in 2003 to forty-one in 2004 to eighteen in 2005. But, crucially, thousands of cases remain unresolved. According to APDP, at least eight thousand people have “disappeared” since the insurgency began.356 In February 2003, the Sayeed government told the state legislative assembly that 3,744 persons had gone missing in Jammu and Kashmir in the period 2000-2002 alone.357

Disappointingly, however, while initially Chief Minister Sayeed promised an end to “disappearances,” he, like his predecessors, later began to claim that many of those missing since 1990 were actually in Pakistan training to be militants. In May 2003, the Sayeed government investigated the APDP lists and concluded that twenty-two “disappeared” persons from a list of 116 had joined militant groups or were in Pakistan, while forty-three persons had been found in their homes during police investigation. Of the rest, it claimed that six were dead, two were in custody with cases registered against them, and investigations were still ongoing in thirteen cases. The APDP responded saying that only two of the twenty-two had actually joined the militants, that some of those who the government claimed were home were actually still missing, and it demanded details in the cases of the six people who the government had claimed were dead. The truth is somewhere in between. The APDP does not have the capacity to follow up on each case of “disappearance” reported to it and, therefore, in some cases it was found during Human Rights Watch’s investigations that the person had not actually been “disappeared,” and was safely home. However, government claims that many of those missing have joined the militants appear to be inaccurate. The debate about the facts and the inconclusive nature of government and NGO claims make it clear why the government or a specially designated independent body should conduct a transparent investigation into each case of “disappearance” reported since 1990.

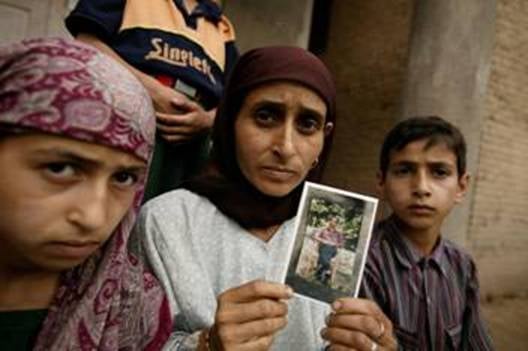

“Disappearance” of Manzoor Ahmed Mir, Awantipora, September 12, 2004

At approximately 9 p.m. on September 12, 2004, Manzoor Ahmed Mir, a thirty-seven-year-old state government employee, had just finished dinner when there was a knock on the door. His house was surrounded by security forces. Most of the men were in uniform, but there were also three masked men in civilian clothes. According to Mohammad Akbar Mir, Manzoor Ahmed’s brother,

The soldiers said that they wanted to search the house. We were told to wait outside with some of the soldiers. Others went into the house. They asked my brother to come into the house with them while they searched. After some time, the soldiers left. We went inside and realized that my brother was missing. They had taken him away. We ran outside and told the soldiers who were still walking out to the road that my brother was gone. But they refused to listen.358

The next day the family went to the police station to lodge a complaint. Mohammad Akbar was later informed by Sheikh Mohammad, the local police chief, that Manzoor Ahmed was alive and would be released soon. But he never returned. Mohammad Akbar says that a month later Sheikh Mohammad was transferred from the area and the police stopped taking an interest in the case.

The family was particularly concerned because Manzoor Ahmed had recently quarreled with one of his neighbors, a police sub-inspector. The police sub-inspector had allegedly threatened Manzoor Ahmed. A few days before he was taken away, approximately eight to ten masked gunmen had barged into Manzoor Ahmed’s house. When the women started screaming for help, the gunmen ran away. Manzoor Ahmed then filed a police complaint against the sub-inspector. (When Human Rights Watch tried to contact the sub-inspector, we were told he was not at home.)

The wife of Manzoor Ahmad Mir holds a photograph of her missing husband while her children look on in Awantipora, Kashmir, August 1, 2005. The husband was taken from his home at night by Indian soldiers following a dispute with a police official on September 12, 2004. He has not been seen since nor has any proof of his arrest been given.

© 2005 Robert Nickelsberg

Mohammad Akbar insists that he recognized the three masked men who came with the soldiers. He claims that they had been to the house earlier with the armed gunmen and believes them to be the police sub-inspector and his two sons. “These people are our neighbors. I’ve known them for years. They may have covered their faces, but I could still recognize them.”359

In April 2005, Manzoor Ahmed’s family filed a habeas corpus petition in the Srinagar High Court. According to their lawyer, the sub-inspector and his sons were named in the petition and filed a response claiming that they knew nothing about Manzoor Ahmed’s “disappearance.” The police and the army have not responded. The final chance to respond to the petition lapsed in February 2006.360

“Disappearance” of Mohammad Ashraf Bhat, Baramulla, June 23, 2003

Mohammad Ashraf Bhat, a twenty-six-year-old heart patient, on June 23, 2003, traveled to Srinagar with his mother to meet with his doctor and purchase medicine. Just as his bus from Baramulla to Srinagar was about to turn into the bus stand in Srinagar, security forces in plainclothes stopped the bus. Some men entered the bus and asked Mohammad Ashraf to step down. According to his mother, Raja Bano, he was then put into a white car and driven away.

I did not know what had happened. It happened so suddenly. I was alone, my son had been taken away, and I did not know where to go in Srinagar. Some people saw me sitting at the bus station and crying. They took me to the police station to file a complaint. But the police refused to help, saying that I should file a complaint with our local police station in Baramulla. In Baramulla, the police said that since he had been picked up in Srinagar, it was their case….We went back and forth like this. No one was even willing to register a case.361

The next month Raja Bano wrote to the magistrate complaining that the police were refusing to register a complaint. The magistrate instructed the police to register the complaint and begin investigations. Raja Bano says she has been going to the police station since the complaint was lodged, but they tell her there has been no progress.

Raja Bano said that her son’s “disappearance” is linked to the surrender of a militant called Fayaz Ahmad Dar two days before, on June 21, 2003. The next day, security forces in plainclothes arrived at the home of Mohammad Ashraf; according to Raja Bano, Fayaz Ahmad was with them. They searched the house and then went away.

The mother of Mohammad Ashraf Bhat, Raja Banu, holds a photo of her “disappeared” son in Pattan, Kashmir, August 3, 2005. Bhat was picked up by Indian security forces from a Srinagar bus station on June 22, 2003, and never seen again. © 2005 Robert Nickelsberg

Nearly three weeks after the “disappearance,” the army arrived at the home once again, accompanied by Fayaz Ahmad. The family was told that the troops were searching for some things that Fayaz Ahmad had left in the house earlier. Nothing was found during the search. The security forces then went to a neighbor’s house, and weapons were recovered from him. The neighbor was arrested, but later released. As of February 2006, there is no news of Mohammad Ashraf Bhat.

“Disappearance” of Showkat Ahmad Pal, June 23, 2003

On June 23, 2003, Showkat Ahmad Pal, a college student, left for his part-time job at the Srinagar News, asmall independent daily. According to a friend present at the time, two Maruti Gypsies, a car model often used by security forces, suddenly drove up as they were walking on Maulana Azad Road in Srinagar. Some armed men in plainclothes pushed Showkat Ahmad into one of the cars before driving away.

Showkat Ahmad’s father, Abdul Rahman Pal, said that they had no idea why his son had been picked up.362 Initially, they did not even know that he had been taken by the security forces. Later, they heard that Mohammad Ashraf, whose case is described above, had been similarly detained by security forces in plainclothes who were traveling in a Maruti Gypsy.

The family has been hunting for Showkat Ahmad in army and police camps. They did not go to court because they feared that if Showkat Ahmad was still alive he would be killed when the judge demanded to know his whereabouts. Showkat Ahmad was still missing as of February 2006.

“Disappearance” of Bashir Ahmad Sofi, June 2003

On June 17, 2003, paramilitary forces, some in plainclothes and others in uniform, arrived at the home of Bashir Ahmad Sofi in Srinagar at around 1:30 a.m. Bashir Ahmad, who often traveled to other Indian cities to sell shawls, was woken up and told that he was wanted for questioning. The soldiers told his family that he would be released in the morning. Hamida Sofi, Bashir Ahmad’s sister, says that it was the Border Security Forces who took her brother: “I saw the BSF insignia on the uniform.”363

When he failed to return, Bashir Ahmad’s relatives filed a police complaint. A week later a police officer named Jala told the family that Bashir Ahmad had been detained by the 61st Battalion of the BSF. However, when Bashir Ahmad’s sisters went to the BSF camp, they were told that Bashir Ahmad was not in their custody.

The same police officer later told the family that the BSF had denied detaining Bashir Ahmad, or even holding any operation in the area on that date. Hamida Sofi said that the police had initially promised that her brother would be home soon. “But later, they said they have checked everywhere and no one knows where he is. They also said that the battalion that was posted in the area at that time has since moved to the border.”364

A few months later, a man released from police custody came to meet the family. He said that he had met Bashir Ahmad while they were in custody at a Special Operations Group (SOG) detention center in Srinagar. When the family went to the police with the information, officials demanded to meet the man who had brought them this news. He refused, fearing retaliation. Bashir Ahmad’s family appealed to the State Human Rights Commission (SHRC), which recommended cash compensation. Bashir Ahmad’s relatives say they do not want money. Said Hamida Sofi: “They offered me compensation and a job. I said give me my brother instead.”365

The family does not want to file a habeas corpus petition. “We are four girls and we have to look after our old parents and grandmother. Who will go running to court?”366

“Disappearance” of Mohammad Hussain Ashraf, May 24, 2003

At age sixteen, Mohammad Hussain Ashraf was already working as a carpet weaver to support his family in Srinagar. After visiting a relative called Ali Mohammad Bhat in Pulwama on May 24, 2003, he started walking to the bus station for the trip home. Close to the bus stop was a garage where some men from the 7th Rashtriya Rifles were getting their jeep fixed. Eyewitnesses later told the family that when he saw the soldiers, Mohammad Hussain started to run away. He was immediately stopped and interrogated.

Two mechanics working at the garage, Yasin Mohammad Malik and Shabir Ahmed Bhat, intervened, telling the soldiers that Mohammad Hussain was young and must have been scared when he saw men in uniform. But the soldiers insisted that he had acted suspiciously and asked Mohammad Hussain to take them to the house where he had come from. They searched Ali Mohammad’s house but did not find anything. Nevertheless, according to Ali Mohammad, the soldiers took Mohammad Hussain away.

Ali Mohammad, Yasin Mohammad Malik, and Shabir Ahmed Bhat later testified to the State Human Rights Commission (SHRC) that they saw the army take Mohammad Hussain into custody. They took down the vehicle registration number, 98B-065366, and later gave it to the police and SHRC.

When Kharzi Begum, Mohammad Hussain’s mother, heard about the detention, she rushed to the Khrew camp where the 7th Rashtriya Rifles is based. She was told that Mohammad Hussain would be released soon. When she returned, however, she was not allowed to speak to any officials. On June 5, 2003, the family filed a police complaint. On June 7, when she went back to the Khrew camp looking for her son, Kharzi Begum was told that her son had already been released. But as of February 2006 Mohammad Hussain has not come home. Khazri Begum said she went back to the 7th Rashtriya Rifles camp and to the police several times, but they didn’t do anything to help:

At the Rashtriya Rifles camp, they would not even allow me to enter. And when I went to the police, they say they cannot do anything because the army says that my son has already been released. Where is he then?367

“Disappearance” of Abdul Rashid Hajam, Dangerpora, Baramulla, November 16, 2002

On the morning of November 16, 2002, Abdul Rashid Hajam went to work at his apple orchard in Baramulla. He has not returned since. According to his wife, Safiqa Bano:

Two of our neighbors saw an army jeep and an army truck stop near the orchard. They saw some soldiers call him to talk to them. The orchard is fenced with barbed wire, but they asked him to crawl under it and come to the road. They talked for a bit and then he walked over to the jeep. The man in the jeep pointed to the truck. After he got in, they pulled down the canvas curtain at the back of the truck and they drove away.368

The family filed a police complaint and also went to the adjoining army camps in search of Abdul Rashid. No one had any news of him. The local police and the commander at the local army camp in Chaksari questioned the two eyewitnesses. The local district authorities also conducted enquiries. They could not trace Abdul Rashid or even discover the army unit that was operating in the area at that time.

Soon after Abdul Rashid “disappeared,” local villagers protested, blocking traffic on the National Highway. One army officer, Maj. Vishal Dhobi of the 29th Rashtriya Rifles from the Chaksari camp, met with the family and promised to try and locate Abdul Rashid. He failed, but offered the army’s assistance in educating Abdul Rashid’s children. On June 3, 2003, he wrote a letter to the district authorities saying:

This is to inform you that Abdul Rashid Hajam… was picked up by unidentified security forces in a military van on 16 November 2002. On doing investigation it has come to notice that the above mentioned is suspected to be dead. Hence an ex gratia case must be initiated as soon as possible for the relief of his widow and three minor children.369

The family received neither compensation nor any news of Abdul Rashid. The family appealed to the State Human Rights Commission. The police, in response to a notice from the SHRC, said that, “During our investigations all security forces units operating in the area were approached…. But no clue was struck.”370 As of February 2006, Abdul Rashid was still missing.

C. Torture and Cruel, Inhuman, and Degrading Treatment

“You have to agree that we will not get the information we need over a cup of tea.”

—Indian official talking to Human Rights Watch about interrogating detainees371

Indian security forces routinely ignore procedural safeguards designed to prevent torture and other mistreatment of persons in custody. Although Indian law requires that everyone taken into custody must be produced before a magistrate within twenty-four hours, this rule is usually ignored. Sections 330 and 331 of the Indian Penal Code forbid the causing of “hurt” or “grievous hurt” to extract a confession, and prescribe prison terms and fines for officers found guilty of torture.372 The Criminal Procedure Code also has clauses to protect detainees from torture: Section 54 provides the right to a medical examination, Section 162 bars the use of written confessions at trial, Section 164 requires a magistrate to ensure that a confession is voluntary, and Section 176 requires a magisterial inquiry into any death in custody.373 The Supreme Court has stated resolutely that Article 21 of the Indian Constitution protects individuals from any form of torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.374 All of these provisions are routinely disregarded.

Human rights defenders have also long complained that Indian law and jurisprudence do not have an express definition of torture.375 However, India is a state party to several major international human rights treaties that prohibit torture, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Article 7 of the ICCPR states that: “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”376 India has signed, but not ratified, the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (the Convention against Torture).377 The Convention against Torture defines torture as:

any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.

As a signatory to the Convention against Torture, India is “obliged to refrain from acts which would defeat the object and purpose” of the treaty.378 Additionally there is such a strong international consensus on the prohibition against torture that it is considered to be binding customary international law on all states, including those that have not ratified the Convention against Torture.379

Torture remains endemic in India. According to former detainees and senior police officials, torture is routine in the interrogations of alleged militants in Jammu and Kashmir. Says Riaz Ahmad, a lawyer at the High Court Bar Association:

Of course there is torture. It is routine. But most people are so glad to be out of interrogation alive, they don’t really complain about the torture.380

It is not just Kashmiris suspected of being militants who are subjected to torture. Relatives of militants are also taken into custody and tortured, either to discover the whereabouts of a suspect, or as a way of forcing the militant to surrender. One man, the brother of a militant, told Human Rights Watch that he was beaten and given electric shocks in custody so that his brother would be forced to surrender. It finally stopped when his brother was killed in an armed encounter in 1998.

I curse my brother for what he brought upon me…. But more than that I curse the soldiers. I was only a boy at that time. They would strip me, make my lie naked on the floor, kick and beat me, split my legs wide apart and leave me tied up like that for hours. When I thought I could not bear any more pain, they would give me electric shocks. Then they would let me go and a few weeks later, again. The same thing. It has ruined me so much that now if I see a man in uniform, I start sweating and trembling. They know. There are many Kashmiris like me. They just pat on the back and tell me to go away.381

Torture and other mistreatment usually takes place in interrogation centers operated by the security forces. It most often occurs in the first hours or days after the victim is detained. Detainees are usually first interrogated by the detaining security force for periods of time that may range from several hours to several weeks.382 During this time the detainee is not produced before a court or given access to anyone outside the interrogation center.383 This violates guidelines laid down by the Supreme Court on arrest and detention.384 According to the Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act, individuals picked up by the army have to be immediately handed over to police custody.385 This rule is routinely flouted while security troops interrogate, and often torture, a detainee.

The longer a detainee is held without being brought in front of a judge, the greater the risk that mistreatment will occur. A police official told Human Rights Watch: