Case Studies

Human Rights Watch investigated rocket strikes in several Israeli cities, focusing on those incidents that killed civilians, as well as on other incidents that reveal aspects of Hezbollah’s intentions. This is not a scientific or a representative sampling of cases. There is no publicly available comprehensive listing of where and when Hezbollah rockets fell; we do not know how many hit military objectives, away from public view, or landed in remote locations.

Nevertheless, the cases presented here confirm that in a significant portion of cases, Hezbollah fired on Israeli civilian areas in violation of international humanitarian law. These attacks coupled with Hezbollah statements that indicate criminal intent to target civilians strongly indicate individual responsibility for the commission of war crimes.

In some cases, Hezbollah appeared to be directly targeting civilians or civilian objects, a conclusion based on the finding that rockets repeatedly and over time hit a particular civilian area or object, in the absence of any finding of an evident military objective. One example is the rockets that hit or landed close to the Western Galilee (Nahariya) hospital during the course of the war. That hospital complex is visible from the border and towers above nearby structures. There was no military target to our knowledge anywhere near the hospital when these rockets struck.

In some cases, Hezbollah rockets hit a civilian object, sometimes repeatedly, but the presence in the vicinity of a military objective prevented a conclusion that the civilian object was the intended target. Even so, most of these attacks were indiscriminate in that Hezbollah fired unguided rockets that were incapable of being aimed so that they could distinguish between a military target and civilians. As such, the attacks constituted serious violations of the laws of war.

Hezbollah did not respond to our letters requesting information on the specific attacks described in this report. However, we cite in the case studies that follow the Hezbollah statements of which we are aware concerning specific attacks.

Akko

On August 3, 2006, eight civilians died in two rocket attacks. Five of them died in a single attack in Akko, a coastal city 17 kilometers south of the border, with a mixed Arab-Jewish population totaling 46,000.125 The rocket fell in a Jewish residential neighborhood. It was one of at least 32 rockets that hit Akko during the conflict, nine of them conventional 122 mm rockets and 23 enhanced-range 122 mm rockets, the police said.126

There was no military objective in the immediate vicinity, to our knowledge. Human Rights Watch researchers drove around the town of Akko immediately before and after the attack and noticed no troops or other mobile military targets.

The biggest military target near Akko is the complex of the Rafael Armament Development Authority, a public-sector defense corporation, south of the city and several kilometers from the site of the August 3 attack.

The five killed in Akko were Shimon Zaribi, 44; his 15-year-old daughter Mazal; Albert Ben-Abu, 41; Ariyeh Tamam, 50; and Ariyeh’s brother Tiran, 39.

Human Rights Watch interviewed Ariyeh Tamam’s wife, Tzvia, who was wounded in the attack, along with her sister-in-law, Simcha, and her eight-year-old daughter, Noa. Tzvia said:

It destroyed our entire family. My husband is dead. His brother is dead. Their sister is in a lot of pain. My disabled mother-in-law is devastated; Simcha also used to be her main caregiver. The kids are traumatized forever.

We don’t have a bomb shelter in our building, so when the sirens started, we went to the shelter in my aunt’s building on Ben Shushan Street. After the first rocket fell, and the siren stopped, we went out of the shelter to have a look. My daughter was standing near me, at the entrance, but Ariyeh went closer to the street. Suddenly, there was another loud boom and pieces of metal flew everywhere. I didn’t realize what had happened to me, but I rushed to the place where my husband was standing. All five people who were standing near the fence there were killed. There was blood everywhere; I tried to drag him away, and was screaming, ‘Don’t die; please don’t die!’ My son threw himself over his body, and was also screaming, ‘Daddy, daddy, don’t die!’ Then the police and the ambulances came, and took us all to the hospital.127

The day before this fatal attack, another rocket strike in Akko injured civilians, although none fatally. Chaim Legaziel, who was visiting Akko that day from his hometown of Netua, recalled:

Because of the conflict, we have not seen the grandkids for three weeks. We thought there was a temporary ceasefire and it was relatively safe to go. But as we approached their house in northern Akko, a rocket hit the street some fifteen meters from the car. There was no siren; I just heard the blast and then saw my wife, Tziona, all covered in blood. She suffers from hemophilia, so the blood was streaming like a river. I don’t remember much. I was in shock from the blast myself; I just threw her into the car. Another man was trying to clamp the wound in her stomach, and we rushed her to the hospital. Tziona suffered two shrapnel wounds in the stomach and one in her right arm.128

Arab al-Aramshe

Arab al-Aramshe is a village inhabited by about 1,100 Bedouins, located only 500 meters from the border fence with Lebanon. According to resident Sobhi Miz’il, the townspeople generally stayed put at the start of the war, even though the Israeli army was firing artillery rounds from cannons located 150 to 200 meters outside the village, and Hezbollah rockets were landing in or near their community. Then, on August 5, a rocket hit next to the house of the Jum`a family, killing Fadya Jum`a, 60, and her two daughters, Sultana, 31 and Samira, 33. The house is located inside the village, in an area of homes. A total of about twenty rockets fell on or next to the village during the war, Miz’il said.

Miz’il said that villagers complained to the regional council about the IDF firing artillery rounds from positions so close to the village, but were told that a war was going on and that the artillery had been placed at strategic positions.129

After that incident, many residents fled south to safer parts of Israel, staying with friends, relatives, or in hotels in Beer Sheva, Abu Ghosh, Kafr Kassem, and elsewhere. Some reluctantly returned before the hostilities ended, Miz’il said, because they could no longer afford to pay for lodging elsewhere.

As a party to an armed conflict, Israel is obligated under international humanitarian law to take all feasible precautions to protect the civilian population under its control against the effects of attack.130 This includes avoiding locating military targets within or near densely populated areas131 and removing civilians from the vicinity of military objectives.132

Lt. Col. David Benjamin, head of civil and international law at the IDF Judge Advocate General’s office, said, “We are a small country. If you said you can’t put an artillery piece within 30 kilometers of a village, we couldn’t operate. The IDF has no policy of firing, purposely or negligently [in a way] that endanger[s] its own civilian population.”133

To our knowledge, Hezbollah issued no statement indicating the intended target of its deadly attack on Arab al-Aramshe; it is not known whether it had been aiming at the IDF artillery cannon or simply firing toward the village. Either way, the question remains whether the IDF could have placed its artillery cannons at a farther remove from the village and whether Israeli authorities could have done more either to shelter the residents of Arab al-Aramshe from Hezbollah fire or to assist in their evacuation.

But even where Israel may have failed to take all feasible precautions to avoid endangering its own civilians by situating military assets in or near densely populated areas, Hezbollah would not have been justified under the laws of war to respond with indiscriminate attacks.

Haifa

Haifa is Israel’s third largest city and the main city in the country’s north. Its population of 267,000 is about 13 percent Arab. Haifa is built mainly on the north-facing slopes of Mount Carmel and neighboring hills, which descend toward the bay of Haifa, a major industrial port.

There are slight variations in the official data regarding the number of rockets that fell on or near Haifa. According to one tally, the police recorded 93 rockets falling on or near the city, including offshore; 40 of these fell inside its boundaries.134 The rockets killed 13 civilians, including two who died from heart attacks, wounded 251, and damaged 1,282 residential buildings and 700 cars, according to data provided by the city’s police department.135

Situated 30 kilometers south of the border, Haifa had no experience of being hit by rockets from Lebanon, although Iraqi Scud missiles reached it in January 1991, during the Gulf War between Iraq and a US-led coalition.136

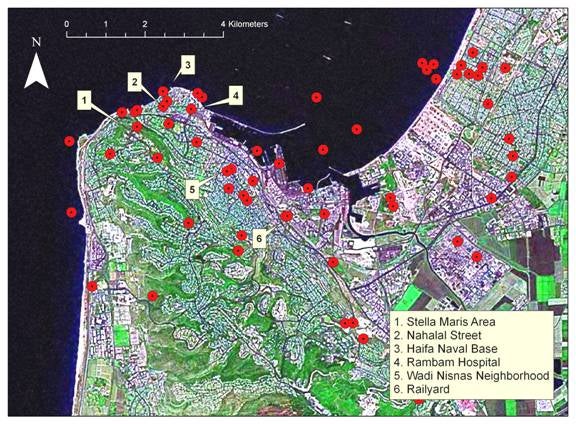

Rocket strikes in Haifa during 2006 armed conflict according to data provided by Israel Police.

© 2007 Human Rights Watch

The first rocket of the 2006 conflict to reach Haifa struck on the evening of July 13, the war’s second day. City Police Chief Nir Meri-Esh identified it as an enhanced-range 122mm rocket that landed near the Stella Maris monastery, about halfway up Mount Carmel, near the top of a hillside cable-car line. It caused no injuries or major damage.

In a statement issued at 2 p.m. that day, Hezbollah had threatened to attack Haifa and its surrounding areas if Beirut or its suburbs were attacked. After Israel reported the strike on Haifa, Hezbollah deputy leader Sheik Na`im Kassem initially denied the report. "Bombing Haifa,” he explained in a phone interview with al-Jazeera television, “would be linked to any bombing of Beirut and its (mainly Shiite southern) suburbs .… It would be

Israeli officials called the attack on Haifa on July 13 “a major escalation.” No further rockets hit Haifa until July 16, according to Police Chief Meri-Esh.

July 16 Attack Kills Eight Workers in Railroad Hangar

On the morning of Sunday, July 16, just as the work week was beginning, a 220mm rocket penetrated the soft roof of a railroad maintenance hangar located in the port area, shooting out tens of thousands of steel spheres. Those projectiles killed eight railway workers and inflicted serious injuries on at least four others.

It was the first time Hezbollah had successfully fired a 220mm rocket into Israel. Until then it had relied on regular and enhanced-range 122mm rockets.

As already noted, Hezbollah had sent statements to the press beginning on July 13 threatening to hit Haifa if Israel attacked Beirut or its southern suburbs. On July 16, following the fatal attack on the railyard, Hezbollah said in a communiqué that the attacks on Haifa that day with “tens” of Raad-2 and Raad-3 rockets were a response to Israel’s ongoing attacks on the Beirut suburbs and other regions and on ports and infrastructure, including the Jiyeh power plant. This may have implied that the attack on Haifa’s rail hangar, located less than half a kilometer from a power plant in the port area, was specifically in retaliation for these attacks. Police Chief Meri-Esh speculated that the intended target of this attack was the power plant.138 In a speech on July 16, Nasrallah stated that Hezbollah had refrained from hitting Haifa’s petrochemical facilities so as to avoid a dangerous escalation, but that such restraint would not continue if the enemy’s “practices its aggression without red lines.”139

Israel’s national railroad, of which this maintenance hangar is a part, is above all a transportation network for Israel’s civilian population. While soldiers use it individually for transportation, the railroad contributed in no substantial way to Israel’s war effort, and therefore cannot be considered a military target.

Human Rights Watch interviewed three injured railway workers at Rambam Hospital. One of them, Alek Vensbaum, 61, recalled:

There were three loud booms and I started running out of the depot …. One of the guys, Nissim, who was later killed, yelled at everyone to run to the shelter. The fourth boom got me when I was nearly at the door, and I was hit by shrapnel

Yaron Yitzhak, 37, added:

At around 9:30 I heard two booms, and the third caught us. I was working on track 6, and there were others working on track 5. The rocket fell on track 3 .... After the first two explosions, we all started running towards the “safe rooms,” which were on the other side, and the third rocket caught me half-way across.

I was hit by shrapnel in both legs, my collarbone, a ball-bearing in my nose and another shattering my eye. I don’t know how long I will remain in the hospital; I will probably need plastic surgery for my eye injuries.141

Sami Raz, 39, a railway electrician, said a steel sphere pierced his lung and lodged near his heart. “I had terrible difficulty breathing after I was hit,” he said.142

More than twenty rockets landed in or near Haifa on July 16, according to Police Chief Meri-Esh, but only the direct hit on the railway hangar caused any serious injuries.143 He described the kind of rocket used in that attack:

The warhead of the 220mm rocket is very sensitive. Whatever it touches, it detonates. With the 122mm rockets, we had a lot of duds. But with the 220mm there were none. They all shot their ball bearings around. Some of the rockets that landed just offshore sprayed the balls into the nearby buildings. One of the 220mm rockets that hit the Carmel [the upper part of the city] brushed the top of a tree [and dispersed its steel balls] before landing on a roof. As a result, all the streets and sidewalks and cars nearby had hundreds of holes.

July 17 Attack Nearly Destroys 3-Story Apartment Building

On July 17, Human Rights Watch researchers visited a three-story apartment building at 16 Nahalal Street in Haifa’s Bat Galim neighborhood after a 220mm rocket heavily damaged its top two floors and wounded six residents, one seriously. The researchers collected steel spheres that had pierced the walls of the apartment building across the street and car windshields up to one block away.

Malka Karasanti, 70,was inside the apartment building that was hit:

I was taking a nap in my apartment on the second floor, when at around 2:30 in the afternoon I heard the siren go off. I went into my bathroom, which I use as a safe room [since there is no shelter in the building]. There was a loud boom, and then everything began to collapse. I was injured in my right shoulder bone, broke a left rib, and have a tear in my eardrum and don’t hear well now. There were two sirens that went off within the hour, and the rocket hit after the second. After about 8 to 10 minutes, the police and firefighters arrived and rescued me.

Malka’s daughter, Mira, added that her mother sat on the toilet, which remained in place when the floor and walls collapsed, because the plumbing to which the toilet is connected supported it. Malka continued:

Most of the people living in the building were not at home at the time, or were injured lightly, except for one fellow who was on his balcony on the first floor when the rocket hit, throwing him off. He has serious head injuries and is here in the hospital.144

The apartment building is located about 100 meters from a major naval training base on the waterfront, and about half a kilometer from Rambam Hospital. The naval base is a legitimate military target.

International humanitarian law obliges Israel, as a warring party, to avoid, to the extent feasible, locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas, and to protect the civilian population under its control from the effects of attack.

Hezbollah may have been seeking, some of the time, to strike valid military objectives such as the naval training base. However, its unguided rockets were unable to target these objectives precisely and instead, in many cases, indiscriminately hit civilian neighborhoods and objects.

More than 45 rockets fell within 500 meters of Rambam hospital, according to data provided by the Haifa police department. The intended target of these rockets is not known; however, the naval base is across the street from the hospital campus.

According to Haifa police chief Meri-Esh, the IDF had emptied its soldiers from the base on the second day of the war. The base, whether staffed or emptied, constitutes a military objective. But being disused would affect the calculation for proportionality—an attack on an empty base would more likely have posed risks to civilian and civilian structures in the vicinity, such as Rambam hospital, that exceeded the expected military advantage from such an attack.

Rambam, the largest hospital in northern Israel, provides specialized services for residents of the entire region and general care for Haifa residents. The fact that it also treated wounded soldiers, many of whom were flown in by helicopter from the Lebanese front, would not make the hospital a military target.

August 6 Attack Kills Three Elderly Persons

If Hezbollah had indeed been targeting military or industrial objects in Haifa some of the time, it expressed no regret for the civilian casualties it was inflicting until its rockets first hit the majority-Arab neighborhood of Wadi Nisnas on August 6, killing two residents and seriously wounding a third. It was then that Hezbollah secretary-general Nasrallah went on television to urge Arab residents to leave the city. (See chapter below on “Hezbollah’s Justifications for Attacks on Civilian Areas.”)

A building in the Wadi Nisnas neighborhood of Haifa, housing the archives of al-Ittihad newspaper, after a rocket struck on August 6, 2006, killing two elderly persons next door. © 2006 Erica Gaston

Wadi Nisnas is located about one kilometer above the industrial waterfront. On August 6 Hana Hammam, 62, and Labiba Mazawi, about 67, were sitting on Hammam’s ground-floor front porch, drinking coffee. An alarm sounded, but they did not seek shelter. The rocket struck the building next door, spraying steel spheres that mortally injured both of them. The building that was struck houses the archives of the Arabic-language communist daily newspaper al-Ittihad.

Saha Bahhar, a political activist who lives one flight up from the porch where the two were killed, recalled:

I was waiting for the evening news on TV. There was a siren a few seconds before, then a boom. I was thrown by the impact. After that I started running to the bathroom, afraid that another rocket would land. The windows were shattered. The man did not die immediately. He was taken away by ambulance. After a few hours, his daughter came up crying, and told me. Both of the victims died from the steel balls. Another downstairs neighbor suffered a spinal injury in the same attack, and is now on a wheelchair.145

At about the same time, another rocket—perhaps from the same volley—landed a few blocks away, destroying a one-family house at 6A Kaesarya Street. Resident Mohammed Saloum, an athletic 40-year-old at the time, was outside. When he ran in to rescue his sister and mother, cooking gas canisters exploded and inflicted on him extensive burns and injuries requiring the amputation of one leg. One year later, Saloum remained in the intensive care unit at Rambam Hospital, undergoing treatment for the burns and for infections in his lungs and blood.146

That evening, Hezbollah issued a communiqué stating that it had attacked Haifa at 8 p.m. with “tens of Raad-2 rockets” in response to Israel’s attacks earlier in the day on Beirut’s southern suburbs.

These were the only two rockets to hit the Wadi Nisnas neighborhood during the conflict.

The same day, an elderly Haifa resident died from a heart attack when rockets crashed near her home. Tamara Lucca was 84.

Targeting the Port Area

The police map of rocket strikes shows three clusters of rocket landings in Haifa, all of them in the lower city: to the west, one encompassing the Bat Galim neighborhood of low-rise apartment buildings, the naval base, and the imposing Rambam Hospital complex; a second cluster in the central port area (including the rail hangar hit July 16) and the neighborhoods just above it; and a third that includes the chemical and fuel storage tanks and refineries at the eastern end of the port. Interviews with Jewish and Arab residents of the city confirmed this pattern.

A rocket hit this apartment building in the Bat Galim neighborhood of Haifa on July 17, 2006, wounding six residents. © 2006 Lucy Mair/Human Rights Watch

Haifa Police Chief Meri-Esh believes Hezbollah was aiming mostly at targets in the port area and that the relatively few rockets that reached the upper city were “over-shots.” The problem is that between the port area and the more affluent upper city neighborhoods on the hill are the lower residential neighborhoods, some densely populated. Thus, if Hezbollah was in fact trying to hit objects on the waterfront, its inaccurate rockets, flying a distance of thirty kilometers, stood a good chance of striking—and did indeed strike—residential and shopping neighborhoods just beyond.

Thus, a rocket slammed into a Bat Galim apartment building on July 17, as described above. Another hit a large post office in the Hadar neighborhood on July 21, injuring thirty, including two seriously. Two days later, 220mm rockets killed sixty-year-old Shimon Glicklich, who lost control of the car he was driving east of Haifa after shrapnel hit it, and Habib Awad, 48, of Iblin, who died from internal injuries while working in a carpentry workshop in nearby Kiryat Ata (see HaKrayot section, below).147

Meri-Esh noted that most or all ships had been moved from Haifa’s harbor during the war, something that city residents also confirmed. Whether ships and facilities were emptied during the conflict, Haifa’s port is home to structures that are military facilities, such as the naval base, and potential dual-use facilities. Dual-use facilities are those that directly contribute to the war effort and if so can be targeted. Attacks on dual-use facilities are bound by the same prohibitions on indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks as attacks on purely military targets. Because dual-use facilities such as electrical power plants and civilian ports typically have significant civilian functions, there is a particular concern that their destruction will cause civilian harm in excess to the anticipated military gain and thus be disproportionate.

The conclusion that Hezbollah was targeting the waterfront is shared by Kobi Bachar, police chief for the adjacent Zvulon district, which includes the industrialized coastline just to the east and north of Haifa. (See separate section on HaKrayot.)

Karmiel, Majd al-Krum, and Deir al-Assad

The 2006 conflict was the first time Hezbollah rockets had reached Karmiel, a city of 44,000 located in the central Galilee’s Beit HaKerem valley, 18 kilometers south of the border. City Police Chief Ephraim Partok said the police identified 193 rocket strikes in and around the city, but more rockets could have fallen undetected in open areas.148 Of the 193 that the police recorded, 67 were within the city itself, of which eleven directly hit homes, he said. Most of the rockets were loaded with steel spheres or submunitions.

While the rockets caused only one moderate injury in the Jewish city of Karmiel, they killed four residents of the adjacent Arab towns of Majd al-Krum and Deir al-Assad.

Karmiel contains no significant military base or other fixed military target; nor was the IDF firing artillery rounds from inside the city, according to the town’s security chief, Yair Koren.149 Outside of town, Cyclone Aviation Products, a company producing both civilian and military aircraft components, has a large plant located in the Barlev industrial park, which it shares with civilian industries. It is located about four kilometers west of the outskirts of Majdal Krum and six kilometers west of the outskirts of Karmiel.

On at least fourteen days during the conflict—July 13, 17, 18, 20, 22, 23, 25, and 28, and August 2, 3, 4, 8, 10, and12—Hezbollah issued communiqués announcing that it had attacked Karmiel earlier in the day. Those communiqués specified no target within the city and never cited, to our knowledge, the Cyclone Aviation plant west of the city. Hezbollah did not reply to requests for information from Human Rights Watch about its intended targets in Karmiel, Majd el-Krum, and Deir al-Assad.

When asked whether there were military targets in the vicinity, some residents of Majd al-Krum and Deir al-Assad said that the IDF had emplaced an artillery piece on a hilltop just north of their towns. Some also said that the Karmiel’s industrial zone might have been considered to be a target. They could point to no other possible military targets in the vicinity of their towns.

But even if any military targets could be confirmed, this cannot explain the general dispersion of nearly 200 rockets in and around Karmiel, Majd al-Krum, and Deir al-Assad during 34 days. It appears much more likely that Hezbollah was deliberately aiming these rockets at the civilian population.

One apparent reason that Karmiel received such a heavy pounding is because it is one of the five Israeli cities with populations over 25,000 within striking distance of a standard 122mm rocket fired from Lebanon (the other four being Nahariya and Akko to the west, and Safed and Kiryat Shmona to the east).150

The rockets started landing in the area on July 13, with five hitting Majd al-Krum, Partok said. After that, they hit Karmiel regularly throughout the conflict. In the first few days, several rockets hit Majd al-Krum to the west and the industrial zone in the eastern sector of Karmiel. From then on, they seemed more dispersed throughout Karmiel and its surroundings.

The rockets caused few physical casualties in Karmiel itself, apparently because its residents were well-drilled in the use of shelters and safe rooms, or fled the city altogether. One-third of the population left town for part or all of the conflict, Partok said. The only resident to suffer more than a minor injury was Boris B., a fifty-seven-year-old Russian immigrant who asked that his family name be withheld. On the morning of July 22, 2006, a rocket went through the roof of the apartment building and blasted into his living room. Boris suffered moderate injuries to his arm and leg, as well as minor shrapnel wounds all over his body.

According to Koren, as many as 600 buildings in Karmiel sustained some damage, most of it light, from shrapnel and especially from the ball bearings that filled the warheads of many of the rockets. Koren said that the damage was worse from rockets that landed in open areas, because they caused a broader shower of shrapnel than when a rocket directly hit a building. “A rocket that fell in the open in one neighborhood could spray ball bearings into a four-story building in another neighborhood,” he said.

Hezbollah hit Karmiel with three basic types of rockets: most were 122mm rockets, loaded either with steel spheres or with submunitions containing smaller steel spheres. About six 220mm rockets and six 240mm rockets also struck in and around Karmiel, Partok said. The latter had no fragmentation, but, he said, “have a lot more explosive power and their effects are horrifying.” Koren noted that two or three of these larger rockets landed outside of the town in the last days of the war. Perhaps these were the same type of rocket that had hit Haifa earlier, he speculated, but Hezbollah could no longer reach Haifa due to having been pushed farther north from their positions closer to the border.

All of the 122mm rockets that the police were able to reach in and around Karmiel contained steel spheres or submunitions, Partok said. This stands in contrast to other cities such as Kiryat Shmona, which received mostly 122mm rockets with standard shrapnel.

According to Koren, Hezbollah first hit Karmiel with rockets containing steel spheres on Saturday, July 15, the day before a ball-bearing filled rocket hit the Haifa rail yard.

Israel Police say they recorded twenty-two cluster munition rockets that landed in Karmiel, more than any other single town or city.151 A rocket containing submunitions fell toward the end of the second week of the war, Koren said, at the entrance to the electric power station, located just behind the municipal building. Most of its submunitions did not explode. The bomb squad originally wanted to remove it but when they saw all of the unexploded submunitions, they decided instead to carry out controlled explosions that night. They then poured concrete to fill the hole.

Karmiel faced special hazards due to the high percentage of unexploded ordnance with submunitions, Partok said. In contrast to rockets loaded with steel spheres, which rarely fail to explode, cluster rockets release submunitions that often fail to detonate upon impact. This presents a risk of explosion to anyone who touches a submunition at a later time. As a result, the police searched intensively to locate and destroy cluster duds, and public authorities conducted a campaign to educate residents to recognize and report them.

Also hard-hit was the nearby municipality of Majd al-Krum, whose 2.5 square kilometers encompass the Arab towns of Majd al-Krum, Deir al-Assad, and Bi’na, with twenty-six thousand people altogether. The edge of Deir al-Assad is several hundred meters west of the Lavon industrial park, north of Karmiel.

According to Salim Sleebi, an accountant and former Majd al-Krum city councilmember, the Israeli media stated that a total of 43 rockets struck the Majd al-Krum area, a number to which he gave credence. He said he had personally seen about 30 spots hit by rockets.152

A single rocket killed two men, Baha’ Karim, 36, and Muhammad Subhi Mana`, 23, on August 4. Another rocket on August 10 killed Miriam Assadi, 26, of Deir al-Assad and her five-year son Fathi Assadi.

Karim, a school teacher, and Mana`, a physical therapist, were killed instantly by a rocket that landed in the street in front of Karim’s house of eastern Majd al-Krum. Tal`at Hussein, 32, who operates a small shop on the street near where the rocket fell, said he was a long-time acquaintance of Karim and talked to him daily. At about 5 p.m. on August 10, Hussein said he was in back of his shop when he heard a warning siren go off. He grabbed his wife and ran inside the shop. About seven seconds later, he said, he heard a thud in the street and then some children shouting. He looked and saw children gathered near two cars, and upon approaching, discovered Karim lying on the street, about four meters away from the cars. Hussein recalled, “He was moving slightly, and there was saliva coming from his mouth, but he didn’t answer me. I knew he was dying.” Hussein said that he believed Karim died of shrapnel wounds in the back but he did not see the wounds. Then he found the body of Mana` about one meter from his car:

He had been driving. When he heard the alarm, he opened his door to flee, and then the rocket landed about two meters from him. He got all of the shrapnel from the rocket, and died immediately. Imagine that you know a person, then you see him, and you can no longer recognize him.153

A pole on a sidewalk in Majdal Krum that was penetrated by steel spheres and shrapnel from a rocket that landed on the street nearby on August 4, 2006, killing two men.

© 2006 Bonnie Docherty/Human Rights Watch

Visiting the site of the attack on September 30, Human Rights Watch saw a filled-over hole in the street that Hussein said the rocket had caused, as well as shrapnel damage on nearby poles and street signs.

Muhammad’s father Sobhi said his son had graduated high school in Majd al-Krum but had had a life-long interest in Germany. He learned German and went to study physical therapy there. Muhammad eventually gave in to family pressure to return home in November 2005, and took a physical therapy job in Haifa. When war broke out in July 2006, his family urged him to leave the country, but this time Muhammad said he would not leave his family until the war was over. Sobhi showed Human Rights Watch a sheath of letters of condolences and appreciation that the family had received from friends and colleagues of Muhammad, both in Germany and in Haifa. A lifelong postal worker, Sobhi said he could no longer focus on his work after his son’s death and was considering early retirement.154

Miriam Assadi, an elementary school teacher, and her son Fathi were killed instantly by a direct rocket hit on their multi-story home in Deir al-Assad, at about 10:40 a.m. on August 10. Fathi’s three-year-old brother Faris lost a leg in the attack, and his grandmother, Fatemeh Faris, 49, lost a leg and some of her hearing, according to Fatemeh’s husband, Assadi Fathi. All of the family members were on the first floor of the house when the rocket hit. Miriam’s brother-in-law, Mohammad Fathi, 18, showed Human Rights Watch a handful of the 6mm steel spheres he said sprayed from the rocket when it detonated. The family has since rebuilt the wall that was hit and resurfaced the shrapnel damage, but the scars are still visible on the trunk of a tree in their back yard.

Asked about potential military targets, Assadi Fathi mentioned that about two kilometers northeast of Deir al-Assad, atop a hill known as Har Chalutz, Israel had placed an artillery piece that fired constantly into Lebanon during the war. He speculated that rockets landing on his family home may have been over-shots aimed at the artillery piece. Then he added, “We’re just citizens of Israel. What happens to the others happens to us.”155

Hezbollah’s wartime communiqués never mention attacks on the Arab towns of Majd al-Krum or Deir al-Assad. But an August 10 statement mentions an attack on nearby Karmiel at 11:20am, a time close to the time of the attack that killed Miriam and Fathi Assadi.

There were two other moderate to serious injuries in the Majd al-Krum area, including one on July 13, the first full day of the conflict. Eighteen-year old Aslan Hammoud, interviewed three days later in the hospital, described how shrapnel hit him in the shoulder, causing nerve damage: “It was around three in the afternoon, and I was in the house downstairs. It is a house on pillars, and there is an open area, a courtyard underneath the house. I heard an explosion and was hit with shrapnel.” Aslan’s mother said she was sleeping at the hospital with her son while her husband remained at home taking care of their other four children. The husband is a fishmonger and cannot just close his shop, since they need the money, she said.156 A visit to the site on July 18 suggested that the shrapnel came from a rocket landing in a parking lot across the street.

More than twelve rockets landed in the eastern part of Majd al-Krum during the conflict, causing a few light injuries. According to Sleebi, the community activist and accountant, three of these landed on July 13—the first full day of the war—and four on August 13. One that landed between the house of Soheil Idriss and the house of a neighbor destroyed a wall and riddled his car with holes from steel spheres, and also slightly injured two of his children, who were inside the house at the time.

Other than Faris Assadi and Fatemeh Faris, the rockets that hit Majd al-Krum/Deir al-Assad caused serious injuries in one other case. A rocket that landed near the main road outside of Majd al-Krum on August 6 inflicted shrapnel wounds to the head of village resident Yassir Bshouti, 32, as he was driving by. Bshouti, who worked in the building trade, was paralyzed as a result of his injuries; the others in his car escaped injury.

Kiryat Shmona

Since the 1960s, more rockets have hit Kiryat Shmona than any other Israeli city. Between 1968 and “Operation Grapes of Wrath” in April 1996 inclusive, a total of 3,839 rockets hit this city located three kilometers from the border, killing eighteen persons, injuring 310, and causing another 175 to seek treatment for shock, according to a city official. 157 Palestinian groups and not Hezbollah were responsible for some of these strikes, especially in the earlier period.

The 2006 conflict was no different: more rockets landed in the city than any other. However, Kiryat Shmona’s 22,100 residents, long accustomed to being under fire, suffered no fatalities. About half of the residents left the town, according to Danny Kadosh, managing director of the municipality,158 while the rest relied on “safe rooms” in their homes and the extensive network of shelters.

What made 2006 different from previous periods of rocket attacks—and what made it hard to endure—was its duration and intensity. Never before had the city been hit with so many rockets and over such a long period of time. According to the tally provided by the IDF, 1,017 rockets landed in or near Kiryat Shmona, 248 of them inside the city. Hezbollah’s wartime communiqués listing rocket attacks on Israel mentions Kiryat Shmona as a target on more than twenty occasions, more than any other town or city.

122mm rockets made up the vast majority of weapons hitting Kiryat Shmona. There were also 15 to 20 mortar shells, and one 240mm rocket, according to Kadosh. There were no cluster munitions or steel-sphere-loaded rockets.

Forty-five residents sustained physical injuries, including twelve who suffered internal injuries, Kadosh said. “We had people hit by shrapnel, who were first diagnosed as having light wounds; then it turned out they had shrapnel embedded in their heart or other organs, and required re-hospitalization.” About 380 persons received treatment for trauma or shock, he added. About 2,000 buildings in and around Kiryat Shmona were damaged, mostly surface damage from shrapnel that sprayed out from the point of impact.

The eastern side of town was hit more than the west, Kadosh said. He speculated that this is because of the shape of the mountain that separates the city from the border. Rockets fired from Lebanon are more likely to fly over western Kiryat Shmona, which clings to the side of the mountain, and land beyond it in the eastern part of the city.

Kadosh said there was a small base attached to the IDF command located inside the city, as well as an IDF medical facility. “The nearest fighting base is based in Metullah,” he said.

Humanitarian law requires that military and civilian medical units used exclusively for medical purposes be respected and protected in all circumstances.159 “Medical units” include “hospitals and other similar units, blood transfusion centers, preventive medicine centers and institutes, medical depots and the medical and pharmaceutical stores of such units.”160 However, military command centers are legitimate targets.

During the war, the fighting base in Metullah, a border village 7 kilometers to the north, moved some of its operations to the outskirts of Kiryat Shmona, Shimon Kamari, the city’s deputy mayor said. 161 Human Rights Watch, on a visit to the city on July 23, 2006, saw an artillery battery firing into Lebanon from a location northeast of the intersection between the main north-south highway (No. 90) and the road heading east to the Golan Heights (No. 99). Although located outside of Kiryat Shmona, it was close to housing on the city’s northern edge. Deputy Mayor Kamari explained, “Since recent events started, even before Katyushas fell on Kiryat Shmona, an artillery battery was moved from the border down to here. They make more noise and frighten the people here more than the Katyushas, but there is no choice: They were attacked when they were on the border. That is why they moved them down here.”

International humanitarian law obliges Israel, as a warring party, to the extent feasible, to avoid locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas, and to protect the civilian population under its control from the effects of attack.

Hezbollah may have known the location of the artillery cannon firing from near Kiryat Shmona, which was on the easier-to-hit eastern side of the town. But the widespread dispersion of strikes in and around this border city throughout the conflict strongly indicates that Hezbollah’s target was the city itself. If Hezbollah was in fact trying to hit the city’s small IDF command base or the nearby artillery piece some or all of the time, its fire was indiscriminate.

HaKrayot

HaKrayot, Hebrew for “the towns,” refers to the coastal suburbs between the city of Haifa to the southwest and Akko to the north. HaKrayot’s population is about 300,000, exceeding that of Haifa. It includes both vast industrial zones as well as residential areas. HaKrayot towns make up most of the Zvulon police district, which also includes some smaller inland towns.

According to government statistics, 124 rockets landed in the Zvulon district, sixty of them inside cities. Zvulon Police Chief Kobi Bachar said that rockets fell on the region throughout the 34 days of the conflict. In addition to the 122mm and 220mm rockets, three 240mm Fajr-3 type rockets and one 302mm “Khyber” rocket landed in the district, he said. The latter landed in the inland Arab village of Ras ’Ali, south of Shfar’Am.

Rockets killed one and injured about eighty civilians in HaKrayot, Bachar said, not counting some three hundred who required treatment for shock or anxiety. Bachar added the casualties were not higher because the residents are well-trained to use shelters and safe rooms, and because a large percentage fled the region for part or all of the war.

Bachar said the pattern of rocket landings in the district indicates that Hezbollah was trying at times to hit industrial plants and at times civilian-populated areas.162 There were direct hits on houses in Nesher (southeast of Haifa) and Kiryat Yam, and hits in residential areas of Kiryat Tiv’on, Kiryat Bialik, Kiryat Motzkin, and Kiryat Chaim.

Hezbollah hit the Delek oil terminal near Kiryat Chaim on July 16. On that day, Nasrallah gave a speech on al-Manar television in which he claimed that, while Hezbollah was able to strike Haifa’s chemical and petrochemical plants, it had refrained from doing so in order to avoid “pushing matters into the unknown.”163

In the view of both Bachar and Haifa Police Chief Meri-Esh, Hezbollah sought to hit Kiryat Chaim’s ammonia and ethelyne storage facilities as well. Bachar said a number of rockets landed within a 500 meter radius of these facilities, including many that fell in the sea nearby. He said the stocks in these tanks had been emptied at the start of the war to minimize the hazards if a rocket struck them. Ethelyne is combustible, while ammonia is an irritant gas that could create a public health emergency if released into the atmosphere. But a danger remained since neither could be emptied entirely.

As noted in the subsection on Kiryat Yam below, Bachar also believes Hezbollah was trying to hit the Rafael Armament Development Authority complex that starts at the northern limits of that city.

Industries may or may not be military objectives, depending on whether they directly contribute to the war effort: An ammunition factory is a target; an automobile factory is one only if it is producing vehicles for military use.

The only rocket fatality in the Zvulon district was Habib Awad, killed when a rocket hit the carpentry shop in Kiryat Ata where he worked. David Siboni, 60, owner of the carpentry shop, described the July 21 incident:

At around 10:45 a.m. today, I was in my office upstairs, when I heard the siren go off. There were about eight other workers here then. Normally, there are 15. I told them all to head to the safe room near the front of the shop. Three other workers and I were still upstairs when a [220mm rocket] hit us directly. [Awad] peeked out of the door and was killed from the blast. His body was in one piece; all of his injuries were internal. One other man was seriously hurt, another moderately. The others were lightly injured.164

Most of the rockets landing in the Zvulon district were loaded with steel spheres, either the 220mm rockets like the ones that hit Haifa or 122mm rockets loaded with submunitions. The 122mm rockets contained 39 grenades containing tiny steel spheres, according to Bachar, who said the police found 13 rockets with submunitions in the district. As noted above, steel-sphere loaded rockets are effective against soft targets, such as human beings, but of little use against hard targets.

One of the worst-hit Krayot towns was Kiryat Yam, a working-class, heavily immigrant community of 37,400, situated 27 kilometers south of the border. About forty rockets fell in Kiryat Yam, according to town spokesperson Nati Silverman.165 The rockets first hit on July 15, he said, and continued until the end of the conflict. They tended to hit between 10 and 12 in the morning and between 3 and 5 in the afternoon, he said.

The rockets, most of them loaded with steel spheres, caused “a few tens” of injuries, four or five of them serious, the remainder mostly shock. Steel spheres were responsible for all of the physical injuries, Silverman said.

According to Silverman, the IDF has no base in or next to Kiryat Yam. Just north of the city, however, is a large complex belonging to the Rafael Armament Development Authority, a legitimate military target. Kobi Bachar, the police commander for the Zebulon district, said he believed that Hezbollah was trying to hit Rafael. He said that his command responded to three rockets that landed inside the complex, and that Kiryat Yam’s northern Savyonei Yam neighborhood, near the Rafael plant, took a large number of hits. He added that additional rockets could have hit the Rafael complex that were handled by IDF bomb removal units rather than by the police.

Hezbollah strikes on the Rafael complex do not explain the scattershot distribution of rocket landings throughout Kiryat Yam. To our knowledge, the city hosted no other significant military objectives during the war. The distribution of rocket strikes throughout the 5-square kilometer town—assuming that the aerial photograph of the town displayed in the mayor’s office represents them accurately—leaves little doubt that Hezbollah was firing indiscriminately, even if it had hoped to hit the Rafael complex.

Kiryat Yam mayor Shmuel Sisso said he was certain that the hits on the town were deliberate. “If you aim and you miss [your target], then you correct your fire,” he said. “Kiryat Yam had places that were hit twice during the war, weeks apart. Maybe those rockets were launched from the same place.” Sisso speculated that the many rockets that fell into the sea just west of the town were aimed at Haifa, but had fallen short. This was not the case for the rockets that struck inside Kiryat Yam, he said, since the town was not situated along the usual path of the rockets traveling from Lebanon toward Haifa. “The only conclusion is they were trying to hit the town itself,” said Sisso.166

Another indication of Hezbollah’s intentions was that nearly all of the rockets fired on Kiryat Yam were loaded with steel spheres, according to Sisso. Steel spheres are an anti-personnel weapon. “If they had wanted to hit the Rafael plant, they wouldn’t have used the steel spheres. There aren’t a lot of workers there. They would have used explosives.”

Human Rights Watch visited “HaMiflasim” (the road-builders) public elementary school in Kiryat Yam, which a steel-sphere loaded rocket hit on the afternoon of August 13. The rocket slammed into an outer wall of the school, damaging classrooms and causing the characteristic round steel-sphere puncture marks on the school’s exterior wall, the basketball backboard in the courtyard, the perimeter fence and the steel dumpster just outside. The school is located in the city’s neighborhood “Dalet” and is surrounded by low-rise apartment buildings and small houses. In August, school is not in session, but during the 2006 conflict children attended a morning daycare program in the basement. At the time that the rocket hit, however, the children had gone home, and no one was injured.

A wall of the elementary school “HaMiflasim” in Kiryat Yam, damaged by steel spheres from a rocket that hit an adjacent classroom on August 13, 2006. © 2006 Bonnie Docherty/Human Rights Watch

Hezbollah provided no specific information about its attacks on Kiryat Yam or its intended targets there; it has not replied to Human Rights Watch requests for information about these attacks.

Ma’alot-Tarshiha and Me’ilia

The town of Ma’alot-Tarshiha (population 21,100) sits on seven square kilometers on hills about ten kilometers south of the Lebanese border. The town is the result of a merger between the Jewish development town of Ma’alot, built alongside the older and more compact Arab town of Tarshiha. The population of the merged towns is about three-quarters Jewish.

Hezbollah rockets had hit Ma’alot-Tarshiha prior to the 2006 war. During this conflict, the town sustained more rocket hits than any other city beside Kiryat Shmona and Nahariya, according to official statistics.167 These included a single fatal strike that killed three youths. Rockets hitting the town also caused a handful of light physical injuries and shock to scores of others.

According to records provided by the municipality, the first rocket hit Ma’alot-Tarshiha on July 16 and from that day until August 13, one or more rockets landed on 21 of the 34 days that the war lasted.168 They landed mostly in the far larger, Jewish town of Ma’alot, hitting homes, restaurants, shops open areas, streets, and a community center. There were no injuries and almost no property damage in the town of Tarshiha.

August 3, the day with the highest number of hits on Ma’alot-Tarshiha—11—was also the only day on which rockets killed civilians. The victims were three friends from Tarshiha: Shanati Shanati, 17, Amir Na’eem, 19,andMuhammad Fa’our, 17. Fa’our was a high school student; Shanati helped his father in farming, and Na’eem was a part-time laborer. At about 4 p.m., the three were driving in a car on a road surrounded by open fields, just west of Tarshiha and about 10 kilometers south of the border, when a rocket struck their car. They fled on foot toward a large boulder in a field by the road when a second rocket exploded in their midst, inflicting deadly shrapnel wounds on all three. According to Shanati’s father As`ad Shanati, who was in a nearby field at the time of the attack, the fatal rocket was one of about seven that landed in this small area outside of town during a fifteen-minute period.

Shanati Shanati, just shy of his eighteenth birthday, was As`ad Shanati’s third child. “But he was everything to me,” the father told Human Rights Watch. “A son can bury a father, but for a father to bury a son is the hardest thing to do,” he said.169

As`ad Shanati and several Tarshiha residents noted that during the war, the IDF had installed an artillery piece on a hilltop about 500 meters north of the site of the deadly strike. They said it was the only military target they were aware of in the town’s immediate vicinity. Ahmed Fa’our, the father of Muhammad, said that the rockets started landing in and around Tarshiha only after Israel started firing artillery from the nearby hilltop. The municipality’s records show no rockets landing in or adjacent to Tarshiha until July 29.

After Israel began firing artillery from near Tarshiha, “there was lots of noise, and the houses shook day and night,” recalled Ahmed, a forty-two-year-old driver. “There were orders for everyone to remain in shelters. But Muhammad was 17, and there was no keeping him inside. This is a house, not a prison. So he went out that day and at about 4 in the afternoon it happened.”

“Muhammad was the oldest, a model for his brothers and sisters. It took a piece from me,” Ahmed said. “I have 5 other children, but I feel the house is empty. Muhammad was also a model for his friends. His friends won’t leave the family.”170 On the day that Human Rights Watch visited the Fa’our home, several of Muhammad’s friends were in the yard, laying out a decorative sidewalk in his memory.171

Hezbollah may have aimed the volley of rockets that afternoon at the hilltop artillery piece and over-shot it. Just before those strikes, a rocket hit for the first time the Arab village of Me’ilia (population 2,700; see below), two kilometers north of where the rocket killed the three youths. While the presence of this artillery piece on a hill outside of Ma’alot-Tarshiha might explain this particular volley, it cannot explain the rocketing of the populated neighborhoods of Ma’alot throughout the war.

Resident Maha Morani described the attack on Me’ilia:

It was around 3:30 p.m. yesterday …. We live on the third floor in a three-floor apartment building. We left kids at home and went out just for a few minutes to buy some food. My daughter was sleeping in her room in a cradle, and our son was in the living room. Suddenly, the siren went off, and my husband—I don’t know how he felt it—tore at full speed to the house, and just flew up the stairs to the room where Nura was sleeping. He grabbed her and rushed down, and just a minute after they left the house, the rocket hit straight into the room where Nura had been sleeping. She was injured in the eye by pieces of concrete that flew all around. Thank God, our son was in another room, so he was not injured physically, but he was in shock. Since the attack, he has not talked at all, not a single word.172

Hezbollah never disclosed the intended target of any of these strikes, to the best of our knowledge; nor did it reply to our request for this information.

Mazra: Mental Hospital hit

On Saturday July 29, at 3p.m., a rocket hit a residential ward of Mazra Mental Health Center, the only mental hospital in northern Israel. It is located in the village of Mazra (population 3,400), about 13 kilometers from the border, and just south of Nahariya. The hospital has a psycho-geriatric ward that includes Holocaust survivors, the only such ward in northern Israel.

Hospital Director Dr. Ilana Tal said she knew of no military base or other fixed military objective near the hospital.173 She added that the IDF did not fire into Lebanon from the vicinity at any time during the war.

The rocket, which was loaded with steel spheres, caused trauma among patients and staff members, but no physical injuries. According to Dr. Tal, staff had moved the patients to the back of the building after a warning siren had sounded. The shelters on the campus can only accommodate a small fraction of the in-patient population.

Dr. Tal said that by the day of the rocket strike, the in-patient population had been reduced from its capacity of 300 to 216 because of the war. Immediately after the strike, the staff began transferring all 216 patients to Abrabanel and Sha’ar Menashe hospitals in central Israel, a process that was completed by July 30.

On the morning of July 30, while the evacuation was under way, Tal said, five or six more rockets struck on or near the hospital campus, which is about 0.15 square kilometers in size. Only one of these caused some physical damage; the others landed on open areas. The fact that the same hospital was struck twice on consecutive days suggests that the first strike was no accident.

Mghar

About forty rockets hit in or near the hilltop town of Mghar in the eastern Galilee, according to Afif Hinou, a schoolteacher and Mghar resident whose sister was one of two villagers killed by the rockets.

Located twenty kilometers south of the border, the mixed Druse-Muslim-Christian town of 19,000 was hit more than other villages in the vicinity.

Although Mghar itself contains no military targets, to our knowledge, it is located in a militarized area. There is a sizable IDF base near its entrance, Machve Alon, and another base between Mghar and Eilabun six kilometers to the south that, according to Hinou, is stocked with ammunition. It is not known whether and how often Hezbollah was targeting either of these military objectives; however, in an August 5 communiqué, Hezbollah said that at 6:40 p.m. it had attacked Hamoul [sic] and Eilabun military bases “with tens of rockets … in response to ongoing Zionist aggression.”

International humanitarian law obliges Israel, as a warring party, to the extent feasible, to avoid locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas, and to protect the civilian population under its control from the effects of attack. According to a report by Israel’s State Comptroller, the Mghar regional council indicated that half of the region’s 19,000 residents had no access to protected shelters.174

Hinou described what happened on August 4, the day a rocket killed his younger sister, Manal Azzam, 27:

We were at our house. We heard the siren. We heard an explosion nearby and we knew it was in our area. I ran to the automobile. I figured someone needed help. My brother, who is also a neighbor, and I went up to a higher house, and looked and saw a pillar of smoke and dust, and we saw it was rising from our parents’ house below. We ran there; it was about 2:05 p.m. The bomb had hit the neighboring house. No one was inside, but Manal lived in one of our family apartments next door. When I got there, I saw that my father had already entered and left the apartment. He told me that Manal was “gone.” She had received a serious injury to her head.

Tens of people started arriving. I entered the apartment and found her on the floor, dead. I did not see two children Qanar, who is six, and Adam, who is two. One of the neighbors had already come and taken them. After five minutes, they brought the children to the ambulance. They had been lightly wounded by fragments in their body. They were brought to Poriah Hospital [in Tiberias] and treated and released the same day. An ambulance took Manal to Abu Kabir [Forensic Institute in Jaffa]. She was buried the following day, the 5th of August.

Manal was 27 years old. She was killed as she was waiting to go to a wedding. Her husband was supposed to return from work and pick her up.

For my parents, this was the second tragedy: we had a brother who was a lieutenant in the IDF who was killed in an automobile accident in 1997.175

The other Mghar resident killed by a Hezbollah rocket was Doua Abbas, 15, who was inside her home when a rocket hit it on July 25.

The rockets that hit Mghar included some cluster munitions with anti-personnel capabilities. Israel police stated that the one Israeli killed by a cluster munition rocket during the conflict was a resident of Mghar. Human Rights Watch was unable to confirm that a cluster rocket killed either Abbas or Azzam; however, we did collect evidence that cluster munitions hit the town and caused some injuries.

Jihad Ghanem, 43, a factory manager, showed us 3mm steel spheres and pieces of metal that he said he collected in front of his house after a rocket hit it between 2:15 and 2:30 p.m. on July 25, the same day that a rocket killed Doua Abbas. The pieces of metal were consistent with the top of MZD-2, or Type-90 submunitions. Ghanem also said he found in his yard a canister with small weapons stacked on top of each other.

A man holds pieces of MZD-2 cluster submunitions that he said landed in his courtyard in Mghar, on July 25, 2006. On the left are the 3mm steel spheres of the type that injured three members of his family. On the right are pieces of the top of such a submunition. © 2006 Bonnie Docherty/Human Rights Watch

Ghanem’s house is in the western part of Mghar, and faces two other houses occupied by family members. The July 25 rocket lightly injured his son Rami, 8, his brother Ziad, 35, and his sister Suha, 33. Rami’s arms bore irregular scars caused by pieces of shrapnel as well as smaller round marks that Jihad said were caused by steel spheres.

The light injuries and the canister Ghanem found suggest that the submunitions may not have deployed properly.

According to other villagers, the rocket that hit the Ghanem’s property was part of a volley of some 10 to 12 rockets that landed in or near Mghar that afternoon, one after the other. Human Rights Watch could not determine how many of the rockets in this volley contained submunitions, but witnesses said that at least one of the other rockets was a cluster munition. Amal Hinou, 42, a brother of Afif Hinou and of Manal Azzam, showed Human Rights Watch pieces of it on October 8, 2006. Amal Hinou, who makes plate-glass products for construction, said that he collected them in an open field in the Hariq area just outside town. These included several clearly identifiable pieces of submunitions and their casings.

MZD-2 submunitions are easy to identify. They resemble small cylindrical bells with a ribbon at one end. A plastic band full of 3mm steel spheres wraps horizontally around the middle of the cylinder. Inside is an armor-piercing “shaped charge.” The steel spheres carried by Hezbollah’s regular 122mm and 220mm rockets—that is, those that do not contain submunitions—are 6mm in diameter.

Hezbollah did not respond to the queries submitted by Human Rights Watch concerning its use of cluster munitions, its intended targets, or the precautions it took to spare civilians.

It is not known whether Hezbollah rockets hit any of the IDF bases situated near Mghar. Given the known inaccuracy of the rockets that Hezbollah used, there was a substantial risk that even if aimed at these bases, the rockets would land in nearby towns. The decision by Hezbollah to fire these rockets when they were loaded with submunitions, whose area effect makes them especially dangerous in populated areas, exacerbates the indiscriminate nature of these attacks.

Nahariya

An examination of the pattern of rockets falling on the city of Nahariya and public Hezbollah statements leaves little doubt that Hezbollah targeted the city itself rather than any military objective. On at least twelve separate days during the conflict, Hezbollah issued communiqués stating it had attacked Nahariya earlier in the day, providing no details on what had been targeted within the city.

Nahariya is a coastal city of 50,500 residents, living in a mix of houses and multi-story apartment buildings. The city is the northernmost coastal city, only 10 kilometers south of the border. It is 10.5 square kilometers in size. Its population is nearly 100 percent Jewish. To the best of our knowledge, there was no significant military presence or activity inside the city during the conflict.

At least 880 Hezbollah rockets struck the Nahariya area during the 2006 conflict, according to official statistics, killing two persons and wounding 94 or 95 others. The most casualties occurred on July 13, when 28 civilians were injured. A handful of the injuries were moderate or serious, including one that required amputation of a leg. The relatively few fatalities and serious injuries can be attributed to civil defense measures: the city’s residents, accustomed to rocket attacks from the past, were well-rehearsed in retreating to public shelters, neighborhood shelters, and private safe rooms. Some relocated during the war to other parts of the country, while the authorities bused others out for short respites.

Hezbollah had hit Nahariya with rockets in the past, but “nothing like this,” said Galia Mor, the city’s director of public relations.176 Proximity to the border and being within range of rockets had over the years harmed the city’s tourist industry and curtailed investment, she said, forcing some property owners to convert hotels to housing.

On July 13, the day after the start of hostilities, rockets started hitting Nahariya. That morning, a rocket hit the roof of an apartment building and penetrated into an apartment below, killing Argentinean immigrant Monica Seidman, 40. The building is located in the residential Neve Yitzhak Rabin neighborhood, east of the city center. A Hezbollah rocket killed one other Israeli civilian that day, Nitzo Rubin, 33, in the city of Safed.

After July 13, rockets landed in Nahariya almost daily, surpassing the number that landed in any other city except Kiryat Shmona. Of these, 195 hit cars, houses, or other structures directly, Mor said. Residents and property-owners reported rocket-inflicted damage to 1,500 houses and small businesses, and to 155 cars, she added.

Most of the rockets that hit Nahariya were 122mm rockets, according to Kobi Bachar, police commander for the Zvulon region. Some of these were outfitted with steel spheres. A few 240mm rockets also hit the city during the course of the war, according to Michael Cardash, deputy head of Israel Police’s Bomb Disposal Division.177

One possible military target was the factory of Blades Technology, Ltd. (still known locally by its former name, Iscar), in the northern part of the city. The company is a major international manufacturer of blades for jet turbine engines. According to Mor, a number of rockets hit the Blades Technology compound during the conflict. While she said that the northern part of the city was hit more than the southern part, residential neighborhoods around the city were struck again and again.

A schematic map of rocket landings, as drawn by Mor, showed that the hits were sufficiently scattered as to indicate that Hezbollah was firing at the 10.5 square kilometer city itself, whether or not it sought to target the Blades Technology factory.

Nahariya may have been well-prepared, but the persistent rocket attacks took a psychological and physical toll on the populace. When Human Rights Watch visited bomb shelters in Nahariya, in July, most were stiflingly hot and overcrowded. Many local residents had been spending days and nights in the shelters since the conflict began.

Nahariya resident Rosa Guttmann, 52, described the difficulties for the elderly of using shelter: “Access for the elderly is hard with all the stairs,” she said. “It is difficult for them to quickly get down into the shelter and later to climb back out. The shelters are cramped and there isn’t enough room for everyone.”178

Another woman who was staying in the same shelter as Guttman said:

We are in the shelter all the time, since the day things started. We only leave when the emergency services announce on the loudspeaker that we can go out. Sometimes we stay at the shelter during the day and go home to sleep at night. Yesterday we went home at around midnight to sleep but around 2 a.m. rockets started falling and at 5 a.m. we’d had enough, and returned to the shelter. We need more mattresses for everyone to sleep here. It is especially hard for the children. They are bored and scared.

In addition to Monica Seidman, Nahariya’s other fatality was Andrei Zlanski, 37, who was killed just outside a shelter in the Ragum neighborhood on the evening of July 18. Human Rights Watch researchers arrived on the scene just after the attack and spoke with eyewitness Eliav Sian, 34:

The guy put his wife and child into the bomb shelter and then went out; I’m not sure why. There was no siren at the time, just a general warning to enter and stay in the shelters. I was standing near the entrance of the shelter, and the guy was just a few meters away. All of a sudden, I heard a whistling sound, and quickly ran back inside. The guy didn’t make it and was killed instantly by the rocket.

Zlanski, Human Rights Watch later learned, had stepped out of the shelter to get a blanket for his daughter. “There used to be about 70 people in the shelter but after he was killed, many people left town, especially those with kids,” said Yoav Zalgan, 35, a single man who remained in the shelter. “And now 30 people are usually here.”

The same day, Nahariya resident Moshe Zamir, 56, witnessed a rocket strike on his neighbor’s house. “Around 6 p.m., I went outside to sit on my front porch,” he said. “All of a sudden, I heard a huge boom, and I quickly crouched down on the ground. I saw debris flying all over the place, and I ran back inside my house.” The rocket hit the house of the neighboring Akuka family, who had already left town, he said.179

On the evening that the rocket killed Zlanski, Hezbollah announced in a communiqué that it had attacked the “settlement” of Nahariya, among others, “in response to the Zionist enemy’s attacks on regions in Lebanon.”

Nahariya Hospital

The Western Galilee Hospital, more commonly known as Nahariya Hospital, sits just outside of town, about three kilometers east of the city center. It is surrounded by open fields; there are no military assets nearby, to our knowledge. The hospital is a large and modern multi-story facility, visible from the Lebanese border. It serves the half-million residents of the western Galilee, from Karmiel to the coast. During the 2006 war it received 1,872 patients, including 343 soldiers, according to hospital spokesperson Ziv Farber.180 The hospital years ago had adapted its basement to accommodate medical wards so that it could operate underground when necessary, protected from rocket attacks.

When a rocket slammed into the north-facing, fourth-floor ophthalmology wing at about 5:30 p.m. on July 28, no one was injured because the patients and the service had already been transferred to the hospital’s basement. The rocket, which contained steel spheres, left a gaping hole in the outer wall and destroyed eight rooms, along with beds, equipment, and various systems installed in the ceilings and walls.

The hit on the hospital looks intentional when viewed in the context of the many near-misses during the war. Dr Jack Stolero, director of the hospital’s emergency room, worked at the hospital continuously from July 12 until August 4. “I am sure that they were trying to hit the hospital,” he said. “All around the hospital at least ten rockets fell during the war, from the early days to the final days. The same morning that the hospital was hit, there was one that landed right next to the hospital parking lot.”

From the smashed windows of the ophthalmology wing, one can easily see the hills on the Lebanese side of the border from which the rockets had been fired. “There are no military bases around here, nothing military at all,” said Farber. “I believe they know perfectly well they are firing at a hospital.”

Nazareth

On July 19, two steel-sphere-filled rockets hit the Arab city of Nazareth. The first killed two small boys on the city’s edge and the second caused extensive damage to a downtown auto dealership, narrowly avoiding injuries. These were the only two rockets that during the war caused any damage in Nazareth, a predominantly Arab city of 65,000, some 40 kilometers from the border with Lebanon. According to official Israeli statistics, an additional four rockets fell in the vicinity of Nazareth but outside the city limits, and one fell in the neighboring Jewish city of Nazareth Illit (Upper Nazareth).

The father of the two boys, Abd al-Rahim Talouzi, an unemployed painter, described the events on the afternoon of July 19. He was napping at his home on the hillside neighborhood of Safafra when an explosion at about 4:45 p.m. awakened him. He and his wife Nouhad immediately began looking for their eight children. He discovered that two of the older boys, Mohtaz, 14 and Ala’, 13, had taken two of the younger ones, Mahmoud, four, and Rabi`, eight, out to play. The four boys had been walking down a steep alley near the house when a rocket slammed into the roadbed. The older boys were farther down the hill and escaped injury, but Rabi` and Mahmoud, five and eight meters away from the impact respectively, died on the scene, their bodies blackened by the rocket’s explosion. Rabi`’s chest was riddled with holes caused by steel spheres, and Mahmoud sustained wounds from the rocket’s shrapnel.181

The frame of a traffic mirror in Nazareth that was pierced by 6mm steel spheres from a rocket that landed nearby on July 19, 2006 killing Mahmoud Talouzi, age four, and his brother Rabi` Talouzi, age eight.

© 2006 Bonnie Docherty/Human Rights Watch

According to Nazareth residents, less than one minute after the rocket landed, another landed in downtown Nazareth, hitting the automobile dealership and garage owned for the past 35 years by Ased Abu Naja Ased. The blast destroyed the garage, an office with computers, diagnostic machines, several cars being serviced in the shop, and three new cars for sale that had arrived that day. The attack took place on Wednesday, the day of the week that the garage and other local businesses closed early. Otherwise, at least 20 workers would have been in the garage, Abu Naja said.182

Zohar Muslai of the Israeli police said, “The two sites that were struck by rockets are one and-a-half to two kilometers apart, as the crow flies. By coincidence the local police chief and I were on patrol about 50 meters from where the two brothers were killed in the Safafra neighborhood. There was immense damage and shrapnel at the site, caused by a 220mm rocket.” 183

When asked about potential military targets in Nazareth that Hezbollah may have been trying to hit, Abd al-Rahim Talouzi said he believed that the rocket that killed his two sons had been intended for the al-Qashli police station, a large older building that sits atop a hill, approximately 100 meters above the steep alley hit by the rocket. Talouzi said he believed the police station was a military target because it housed sophisticated communications equipment. Human Rights Watch was unable to confirm or refute this assertion.

There is a military base a few hundred meters from the auto dealership, in the Bir al-Amir neighborhood of the city, in the Jabal ad-Dawla area. In the region surrounding Nazareth and nearby Arab villages, there are various IDF defense industries and military bases, including the Kfar Ha-Horesh camp about one-half a kilometer south of the city, and the Ramat David (Nahalal) air force base twelve kilometers west of town.

Hezbollah leader Nasrallah apologized publicly for the rocket that claimed the lives of Rabi’ and Mahmoud Talouzi. In an interview on al-Jazeera TV the following day, he said, "To the family that was hit in Nazareth—on my behalf and my brothers, I apologize to this family …. Some events like that happen. At any event, those who were killed in Nazareth, we consider them martyrs for Palestine and martyrs for the nation. I pay my condolences to them." However, Hezbollah never explained what the intended target of the fatal strike had been, to the best of our knowledge.184

Kibbutz Saar

Kibbutz Saar sits slightly northeast of Nahariya and seven kilometers from the border. The vast majority of its 450 residents, including all children, had departed during the first week of the conflict, and those who stayed spent most of their time in bomb shelters.

On August 2, a rocket killed kibbutz member David Lalchuk, 52, who had stayed in the kibbutz to look after the citrus orchards. At about 1 p.m., he left home by bicycle to check the gardens, but turned back when a warning siren sounded. He had almost made it back to the house when a rocket struck the yard, sending out large shrapnel that pierced his body. Lalchuk died on the spot. He had immigrated years earlier from the United States; his wife and children had left the kibbutz during the conflict.

Kibbutz secretary Yair Boymal said the day after the killing that during the three previous weeks, seven rockets had fallen on the kibbutz itself and many more in the agricultural gardens and fields belonging to the kibbutz. He added:

For three weeks we have not been able to take care of our citrus and avocado plantations, as well as the fields. The irrigation systems factory here has been almost shut down. We are losing money, we are losing clients, but we cannot even leave the shelters most of the time, let alone continue the work.185

Hezbollah did not disclose the intended target of this strike, to the best of our knowledge, and did not respond to a request from Human Rights Watch for this information. Human Rights Watch did not ascertain whether there were military objectives near the site of this rocket strike.

Safed (Tzfat)

Safed, a city of 28,100 in the eastern Galilee, is located on hills 13 kilometers south of the border. According to Israeli statistics, 74 rockets hit the city and another 397 landed nearby. Safed suffered one fatality, Nitzo Rubin, 33, who was killed by a rocket that hit the street near him on July 13.

The rockets landed throughout the city but there were two clusters, according to Israel Police’s Michael Cardash: one near the IDF’s Northern Command headquarters on the northeast outskirts of the city and one near Ziv Hospital in the southwest part of the city, about three kilometers away.186 The hospital treats mostly civilians, but also soldiers wounded in Lebanon, who are often flown in to the hospital’s helipad. The IDF Northern Command is a legitimate military target; the hospital is not, regardless of whether it treats soldiers along with civilians.

A rocket struck next to the northwestern corner of the hospital at 11 p.m. on July 17, about five meters from the hospital wall. The blast broke windows and blew others out from the first to the fourth floors, causing damage to the surgical, internal medicine, and pediatrics wards. It also damaged a reinforced concrete platform that holds some of the hospital’s water and gas-processing systems.

Hospital patient Roni Peri, 37, described what happened: