Map of Sri Lanka

I. Summary

What I am saying is, if there is a terrorist group, why can’t you do anything? It’s not against a community... I’m talking about terrorists. Anything is fair.

—Defense Secretary Gothabaya Rajapaksa, June 12, 2007

My wife was bathing at the well near my hut. I heard one big boom and saw smoke…. Then I saw her lying near the well…. Blood was all around. I called her but she didn’t speak.—Father of two whose wife died in the army shelling of the displaced persons camp at Kathiravelli on November 8, 2006

We just want to know where he is. He can even be in prison but let us know where he is.

—Mother of “disappeared” son, Colombo, March 2007

Sri Lanka is in the midst of a human rights crisis. The ceasefire between the government and the armed secessionist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) exists only in name. Since mid-2006, when major military operations resumed, civilians have paid a heavy price, both directly in the fighting and in the dramatic increase in abductions, killings, and “disappearances.” The return to war has brought serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law.

The LTTE is much to blame. The group, fighting for an independent Tamil state, has directly targeted civilians with remote-controlled landmines and suicide bombers, murdered perceived political opponents, and forcibly recruited ethnic Tamils into its forces, many of them children.1 In the areas of the country’s north and east under its control, the LTTE harshly represses the rights to free expression, association, and movement.

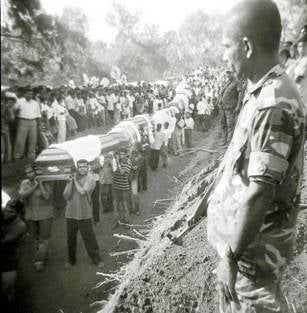

A mass grave for the victims of the LTTE’s June 15, 2006 landmine attack on a civilian bus that killed 67 people. © 2006 Q. Sakamaki/Redux

Human Rights Watch has long documented abuses by the LTTE, particularly the LTTE’s systematic recruitment and use of children as soldiers, the targeted killings of political opponents, and its abusive fundraising tactics abroad.2 We will continue to report on LTTE abuses and press the LTTE to change its practices.

This report, however, focuses primarily on abuses by the Sri Lankan government and allied armed groups, which have gotten decidedly worse over the past year. As the hostilities have increased, the government’s respect for international law has sharply declined, with it often appearing indifferent to the impact on civilians in the north and east.

This report does not aim to be a comprehensive account. Rather, it highlights with examples the main areas of concern, from violations of the laws of war and extrajudicial killings to unlawful restrictions on the media and nongovernmental organizations and the widespread impunity enjoyed by state security forces. It uses victim and eyewitness accounts to document indiscriminate attacks on civilians, the forced return of internally displaced persons, and the spate of arrests and “disappearances” by government forces and allied groups. Case studies reveal how the rights to freedom of expression and association are increasingly under threat from a government intolerant of criticism and dissent. Ethnic Tamils have suffered the brunt of abuses, but members of the Muslim and majority Sinhalese populations have also been victims of government rights violations.

Sri Lanka’s defense establishment is particularly responsible for abuses. The security forces have driven policy on the ethnic conflict since President Mahinda Rajapaksa was elected in November 2005, led by the president’s influential brother, Defense Secretary Gothabaya Rajapaksa. After an LTTE attempt on the defense secretary’s life, the government expanded draconian Emergency Regulations, in place from the previous government, that grant the security forces sweeping powers of detention and arrest. The government has used counterterror legislation against journalists who expose human rights abuses, official corruption, or otherwise question the government’s handling of the conflict with the LTTE.

Even top government officials have expressed concern. In a private letter to President Rajapaksa on December 13, 2006, then-Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera warned that the government must do more to address the deterioration of human rights. Leaked to the press after Samaraweera was sacked, the letter noted “persistent reports about alleged abductions and extra-judicial killings attributed to government forces as well as the [allied] Karuna faction and the LTTE” in areas controlled by both the government and the LTTE. “Whether or not these were committed by terrorist groups or government agencies,” Samaraweera wrote, “it is the responsibility of the government to investigate and prosecute the perpetrators in keeping with Sri Lanka’s treaty commitments.” He added, “Even when fighting a ruthless terrorist group like the LTTE, the Government must not be seen as using the same tactics as a terror group. The rule of law must always be respected by all arms of the government.”3

Ironically, the serious deterioration in the government’s human rights record is taking place under a president who was once a human rights activist, known for getting dossiers of the “disappeared” out of the country to the United Nations (UN) Commission on Human Rights in 1990. President Rajapaksa’s official biography trumpets him as a “champion of human rights,”4 but he has failed to demonstrate those qualities during his presidential term.

Abuses during armed conflict

Some of the most serious international law violations have taken place during armed hostilities, when civilians have died in unlawful attacks and others were displaced. Both the government and the LTTE have shown a brazen disregard for the well-being of non-combatants.

In one of the most deadly incidents of recent years, government shelling in the eastern Vaharai area on November 8, 2006, hit school grounds that were housing thousands of displaced civilians, killing 62 and wounding 47. Government forces failed to distinguish between combatants and civilians and may have purposely targeted the school. Based on interviews with a dozen witnesses and other information, Human Rights Watch found no evidence to support government claims that the LTTE had fired that morning at government forces from the vicinity of the school or had used civilians as “human shields” to protect themselves from attack.

The treatment of internally displaced persons remains a paramount concern. Some 315,000 people have had to flee their homes due to fighting since August 2006; 100,000 fled in March 2007 alone. This comes atop the 200,000-250,000 people made homeless by the December 2004 tsunami—many from the same areas as the recent fighting—and the approximately 315,000 displaced by the conflict prior to 2002. Since January 2006 more than 18,000 Sri Lankans have fled to India, often on rickety boats, as refugees.

Both the LTTE and the government have failed adequately to provide for the needs of the displaced. The LTTE has at times blocked civilians from leaving areas of conflict, while the government through its indiscriminate shelling and restrictions on humanitarian aid has compelled civilians to flee. The government has forcibly returned displaced persons after it deemed their home areas “cleared” of the LTTE, often without adequate security or humanitarian assistance in place.

Internally displaced Tamils collect their temporary identity cards from the Sri Lankan police at Aryampathy refugee camp in Batticaloa in May 2007. © 2007 Reuters/Buddhika Weerasinghe

Humanitarian aid agencies and nongovernmental organizations, domestic and international, are finding it increasingly difficult to service populations in need, and have sometimes come under direct attack. According to the United Nations, 24 aid workers died in Sri Lanka in 2006, including 17 local staff of the Paris-based Action Contre Le Faim who were murdered in August. The Sri Lankan authorities have not arrested anyone for that crime.5

Abductions and “disappearances”

The number of abductions and enforced disappearances is spiraling. The national Human Rights Commission (HRC) said it recorded roughly 1,000 cases in 2006, plus nearly 100 more in the first two months of 2007.6 A government commission established in September 2006 to investigate “disappearances” said in June 2007 that 2,020 people were abducted or “disappeared” between September 14, 2006, and February 25, 2007. Approximately 1,134 of these people were found alive but the others remain missing.7

On the Jaffna peninsula alone, an area under strict military control, more than 800 persons were reported missing between December 2005 and April 2007. According to a credible non-governmental organization that tracks “disappearances,” 564 of these persons were still missing as of May 1.

While the LTTE has long been responsible for abductions, the majority of recent “disappearances” in Jaffna and the rest of the country implicate government forces or armed groups acting with governmental complicity.

While many of the “disappeared” likely have been killed, some may be in detention, held under the newly imposed Emergency Regulations (see below). If so, the government should announce the names of such persons, as well as any charges against them, and list the locations where they are being held. Those not charged should be released.

Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with the family members of 109 people who said their relative had been abducted or “disappeared” since 2006. These included cases from Jaffna, Colombo, Vavuniya, Mannar, Trincomalee, and Batticaloa. The cases can largely be grouped into two basic types: those by the state in the name of counterinsurgency, and those by allied armed groups or the LTTE to eliminate rivals, recruit fighters, or extort funds.

In the lawlessness that has grown in the past two years, criminal elements also appear to have committed some of the abductions. Over the course of late 2006 and 2007 scores of abductions were accompanied by huge ransom demands and the victims were mostly businessmen from the minority Tamil community. By May-June 2007, members of the Muslim community, particularly in the eastern district of Ampara, were targeted as well.

Under growing pressure from within Sri Lanka and abroad, the government has taken some steps to address abductions and enforced disappearances, including some arrests of alleged perpetrators, but none of these steps has significantly slowed the abuse. A one-man government commission on “disappearances” established in September 2006 has issued strong statements about the abuse and the government’s inability to halt it, but the government has not made public any of the commission’s interim reports, nor is it obliged to implement any of the recommendations.

Public statements by the government have rejected the overwhelming evidence of government involvement as “unfounded” and cast those who accuse government forces as sympathizers of the LTTE. President Rajapaksa, once an advocate for the “disappeared,” has dismissed many of the cases as fakes. “Many of those people who are said to have been abducted are in England, Germany, gone abroad,” he said in May 2007. “They have made complaints that they were abducted, but when they return they don’t say.”8

Arbitrary arrests and detention

In August 2005, after the assassination of Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar, the government of then-President Chandrika Kumaratunga imposed Emergency Regulations drawn from the Emergency Regulations of 2000. Long a controversial measure in Sri Lanka, the regulations granted the security forces sweeping powers of arrest and detention, allowing the authorities to hold a person without charge based on vaguely defined accusations for up to 12 months.

Over the past 18 months, the Rajapaksa government has detained an undetermined number of people reaching into the hundreds under the regulations. The primary targets are young Tamil men suspected of being LTTE members or supporters, but the government has recently cast a wider net, arresting non-Tamils for allegedly supporting the LTTE.

The overbroad and vaguely worded regulations allow for the detention of any person “acting in any manner prejudicial to the national security or to the maintenance of public order, or to the maintenance of essential services.” The authorities may search, detain for the purpose of a search, and arrest without a warrant any person suspected of an offense under the regulations.

The regulations also provide for house arrest, restrictions on the internal movement of certain persons or groups, prohibitions on an individual from leaving the country, and limitations on an individual’s business or employment. They allow for the censorship of articles related broadly to “sensitive” issues, and the disruption and banning of public meetings.

The number of people arrested under the Emergency Regulations remains unclear. In March 2007 the government announced it was holding 452 persons under the Emergency Regulations (372 Tamils, 61 Sinhalese, and 19 Muslims), among them 15 soldiers, five policemen, one former policeman, and three military deserters.9 Human Rights Watch requested updated figures in June, as well as the status of cases and the locations of detention, but the government failed to provide the information requested.

In December 2006 the government introduced another Emergency Regulation called the Prevention and Prohibition of Terrorism and Specified Terrorist Activities. The broad, sweeping language allows for the criminalization of a range of peaceful activities that are protected under Sri Lankan and international law. Some of the regulations could be used to justify a crackdown on the media and civil society organizations, including those working on human rights, inter-ethnic relations, or peace-building. The authorities could also use the wide immunity clause to exempt from prosecution members of the security forces deemed to be acting in “good faith.”

Karuna group abuses

The Sri Lankan government has failed to take action against the abusive Karuna group, a Tamil armed group under the leadership of V. Muralitharan that split from the LTTE in 2004 and now cooperates with Sri Lankan security forces in their common fight against the LTTE. With the LTTE’s loss of territories in the east, the Karuna group has exerted de facto authority in the districts of Ampara, Trincomalee, and Batticaloa. The group also expanded its operations in the northern Vavuniya district, engaging in extortion and abductions.

Despite ongoing international scrutiny and criticism, including from the United Nations, the Karuna group has continued to abduct and forcibly recruit children and young men for use as soldiers, with state complicity. Between December 2006 and June 2007 UNICEF documented 145 cases of child recruitment or re-recruitment by the Karuna group. The actual number is likely to be higher because many parents are afraid to report cases, and these numbers do not reflect the forced recruitment of young men over 18.

In February 2007 Human Rights Watch observed armed children guarding Karuna political offices in plain view of the Sri Lankan army and police. A top Karuna Eastern commander was seen riding atop an army personnel carrier. Armed Karuna cadre openly roamed the streets in Batticaloa district in sight of security forces, and in some cases they jointly patrolled with the police.

President Rajapaksa and other Sri Lankan officials have repeatedly promised that the government would investigate the allegations of state complicity in Karuna abductions and hold accountable any member of the security forces found to have violated the law. To date, however, the government has taken no effective steps. No member of the security forces is known to have been disciplined or prosecuted for committing these illegal acts. There is now a clear pattern of complicity by the security forces in abductions, extrajudicial executions, and extortion committed by this group.

Human Rights Watch asked the Sri Lankan government the status of the investigation announced by President Rajapaksa. Prior to any announced results, the government said that it “has no complicity with the Karuna group in any allegations of child recruitment or abduction.” This calls into question the sincerity of the government’s commitment to an investigation.

The mother of an abducted boy from Batticaloa district holds a photograph of her son. © 2006 Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch

Crackdown on dissent

The government has increasingly sought to silence those who question or criticize its approach to the armed conflict or its human rights record. It has dismissed peaceful critics as “traitors,” “terrorist sympathizers,” and “supporters of the LTTE.” And it has used counterterror legislation to prosecute those whose views or versions of events do not coincide with those of the government.

Humanitarian and human rights organizations, both Sri Lankan and international, have come under sustained pressure. The government has dismissed their allegations of human rights violations as “baseless” and influenced by propaganda of the LTTE. “Any group or organization, falling prey to this malicious propaganda of the LTTE, without prior inquiry, investigation or reliable verification, could as well be accused of complicity in propagating and disseminating the message and motives of the LTTE,” the government’s peace secretariat said in March 2007.10

Given Sri Lanka’s Emergency Regulations, which criminalize “aiding and abetting the LTTE,” this broad lumping of human rights groups with the LTTE seems aimed at silencing organizations working to report objectively on human rights, including groups also highly critical of the LTTE.

The climate of fear for human rights activists is intensified by death threats some individuals have received over the phone in the past year, in which unknown individuals warn activists that the government should not be condemned.

In December 2005, a parliamentary committee established to monitor the influx of aid organizations after the tsunami expanded its scope to organizations that work on human rights, democratization, and peace-building. The committee required NGOs to submit their internal records from the past 10 years, such as lists of publications and organized functions, including attendees.

Freedom of the press has taken a serious blow. Eleven Sri Lankan journalists and other media practitioners have been killed by various parties to the conflict since August 2005. To date, no one has been convicted for any of the killings.

Tamil journalists work under severe threat from both the LTTE and government forces. In LTTE-controlled areas media freedom is severely restricted. The LTTE has been implicated in abductions of media practitioners and the killings of journalists. It has routinely pressured Tamil journalists and attempted to force Tamil media practitioners to resign from state-owned media. The circulation of some Tamil newspapers was unofficially banned in parts of the north and east. In October 2006 and again in January 2007 the Karuna group blocked the delivery of the newspapers Thinakural, Virakesari, and Sudar Oli in Batticaloa and Ampara.

The Sinhala-language media is not exempt from government pressure. On November 22, 2006, agents of the police’s Terrorist Investigation Division arrested Munusamy Parameswary, a reporter for the Sinhala newspaper Mawbima, accusing her of “helping the LTTE and a suspected suicide bomber.” Parameswary was apparently targeted because of her writings on human rights violations, including enforced disappearances. The police released her on March 22, 2007, when a court found insufficient evidence to continue her detention.

On February 27, 2007, the Terrorist Investigation Division arrested the spokesperson and financial director of Standard Newspapers Ltd., which publishes Mawbima and the English-language weekly Sunday Standard. Under the Emergency Regulations they detained him for over two months without charge. On March 13, 2007, the government froze the company’s assets, forcing Mawbima and Sunday Standard to stop publication. On May 30, the police arrested the owner of the company under the Terrorist Financing Act on suspicion of providing material and financial assistance to the LTTE.

Over the past year President Rajapaksa has held regular breakfast meetings with media editors. According to participants, he has at times admonished editors for their “unpatriotic” writing. His brother the defence secretary has been more direct: in April 2007 he telephoned the editor of the Daily Mirror, an English-language daily, and told her that he would ”exterminate” a journalist who had written on human rights issues in the country’s east.

Impunity reigns

Impunity for human rights violations by government security forces, long a problem in Sri Lanka, remains a disturbing norm. As the conflict intensifies and government forces are implicated in a longer list of abuses, from arbitrary arrests and “disappearances” to war crimes, the government has displayed a clear unwillingness to hold accountable those responsible for serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. Government institutions have proved inadequate to deal with the scale and intensity of abuse.

One barrier to accountability lies in the failure to implement the 17th amendment to the constitution, which provides for the establishment of a Constitutional Council to nominate independent members to various government commissions, including the Human Rights Commission. Ignoring the amendment, the president has directly appointed commissioners to the bodies that deal with the police, public service, and human rights, thereby placing their independence in doubt. The 17th amendment has been similarly bypassed in the unilateral appointment of the attorney general, which undermines the independence of that office.

In response to rising domestic and international concerns about human rights violations in Sri Lanka, and to preempt proposals for an international human rights monitoring mission, in November 2006 the government established a Presidential Commission of Inquiry (CoI) to investigate serious cases of human rights violations by all parties since August 1, 2005. Instead of an international commission, as many human rights groups had urged, and as President Rajapaksa had initially agreed, the commission is composed of Sri Lankan members, who are assisted by a group of international observers, called the International Independent Group of Eminent Persons (IIGEP).

The Commission of Inquiry has serious deficiencies, and it remains to be seen whether it can effectively promote accountability where state institutions have failed. First, the commission does not appear to have made much headway in the 16 serious cases it has the mandate to investigate, while additional atrocities by all sides continue to occur. Second, the commission can only recommend to the government the steps to take, so its findings will not necessarily result in prosecutions. Third, investigations are stymied by an inadequate witness protection program that would encourage rightly fearful victims and witnesses to testify about abuses by government security forces. Fourth, the attorney general’s office has a direct role in commission investigations—a potential conflict of interest that may undermine the commission’s independence. Finally, the head of the commission is limiting the work of the international experts to a narrow observer-only role, which would prohibit them from conducting investigations and speaking with witnesses.

In its first interim report to the president, the IIGEP warned that the success of the commission was at risk. It expressed concern that the government had not taken adequate measures to address crucial issues, such as “the independence of the commission, timeliness and witness protection.”11 In its second report, the IIGEP questioned the role of the attorney general’s department in assisting the commission, highlighting examples of lacking impartiality. The report said the commission’s conduct was “inconsistent with international norms and standards” and that failure to take corrective action “will result in the commission not fulfilling its fact-finding mandate in conformity with those norms and standards.”12

All of these problems suggest that the Commission of Inquiry is unlikely to make significant progress to change the climate of impunity in Sri Lanka today. The Rajapaksa government has not seriously addressed the escalating human rights crisis, and measures by the government and the CoI to address issues such as the independence of the Commission and witness protection are falling short. The Commission of Inquiry seems more an effort to stave off domestic and international criticism than a sincere attempt to promote accountability and deter future abuse.

An international role

Foreign governments were especially supportive of the Commission of Inquiry, and its increasingly evident failings highlight the need for concerned governments to rethink their approach to human rights protection. In particular, international donor states should intensify their expressions of concern, urging the government to end abuse and punish those responsible. The Sri Lankan government time and again has pledged to its people and the international community that it will protect human rights and hold abusers accountable; it has routinely failed to fulfill that pledge.

The international co-chairs for the peace process (the United States, Japan, the European Union, and Norway), as well as other states, should use their leverage with both the government and the LTTE to encourage respect for international law, including the protection of civilians during hostilities. Financial aid is one lever that international governments have, and states such as the United Kingdom and Germany have recently elected to limit their assistance until government practices improve.

Concerned governments should also use the United Nations Human Rights Council to initiate and support strong resolutions to promote compliance with international law by the government and the LTTE. Most importantly, the international community should work at the Human Rights Council and with the government to establish a United Nations human rights monitoring mission in Sri Lanka to monitor, investigate, and report on human rights abuses and laws of war violations by all sides—the government, the LTTE, and Karuna forces.13

Key recommendations

Human Rights Watch urges the Sri Lankan government, the LTTE, the Karuna group, and key international actors to respond with urgency to the human rights crisis in Sri Lanka. Specifically, we call on all relevant actors to:

Establish a human rights monitoring mission under United Nations auspices to investigate abuses by all parties, report publicly on abuses to enable prosecutions, and facilitate efforts to improve human rights at the local level. Improve humanitarian access to populations at risk, including by ending unnecessary restrictions on humanitarian agencies. Cease all deliberate and indiscriminate attacks on civilians, facilitate rather than prevent civilians leaving areas of active fighting and provide humanitarian agencies safe passage to populations at risk. End use of Emergency Regulations to clamp down on and threaten media, humanitarian and human rights groups, and other civil society organizations. Regularly publicize the names of all persons detained by the military and police under Emergency Regulations and other laws, and provide detainees due process rights, including access to their families and legal representation and to challenge the lawfulness of their detention. Cease the forced recruitment of all persons, end all recruitment of children, and permit those unlawfully recruited to return to their families.

Full recommendations can be found in Chapter XI.

Methodology

This report is based primarily on field research in Sri Lanka in February-March 2007. Human Rights Watch visited Colombo and its environs, and the districts of Batticaloa and Jaffna. The names of many interviewees are redacted or removed, usually at the interviewee’s request, to protect that person from potential harm.

On June 18, Human Rights Watch wrote to President Mahinda Rajapaksa, requesting replies to 33 questions on a range of issues. The government replied on July 12. Relevant answers are included in the report. On some central issues the government did not provide the requested information, such as the number of people arrested under the Emergency Regulations, the number of people arrested on charges of kidnapping or abductions, and the status of the government’s investigation into alleged state complicity in abductions by the Karuna group.

1 In this report, consistent with international law, the words “child” and “children” refer to anyone under the age of 18.

2 See Human Rights Watch, Funding the Final War: LTTE Intimidation and Extortion in the Tamil Diaspora, vol. 18, no. 1(C), March 2006, http://hrw.org/reports/2006/ltte0306/; Human Rights Watch, Living in Fear: Child Soldiers and the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka, vol. 16, no. 13(C), November 2004, http://hrw.org/reports/2004/srilanka1104/; “Sri Lanka: New Killings Threaten Ceasefire,” Human Rights Watch news release, July 28, 2004, http://hrw.org/english/docs/2004/07/27/slanka9153.htm.

3 The Sunday Times Online, vol. 41-no. 39, February 25, 2007, http://sundaytimes.lk/070225/News/102news.html (accessed July 2, 2007).

4 Official website of the President of Sri Lanka, http://www.presidentsl.org/data/about.htm (accessed May 21, 2007).

5 Security Council Briefing by Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs John Holmes, June 22, 2007, http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/RWB.NSF/db900SID/SHES-74ESMZ?OpenDocument (accessed June 25, 2007).

6 Simon Gardner, “Abductions, Disappearances Haunt Sri Lanka’s Civil War,” Reuters, March 5, 2007, and “Sri Lanka Police, Soldiers Arrested over Abductions,” Reuters, March 6, 2007.

7 “US Concerned about Disappeared,” BBC Sinhala.com, June 28, 2007, http://www.bbc.co.uk/sinhala/news/story/2007/06/070629_uscondemn.shtml (accessed July 2, 2007).

8 Teymoor Nabili, “Peace Through War in Sri Lanka,” Al Jazeera, May 31, 2007, http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/654B1090-36E2-4374-AFC9-7EDCE9ACB4C7.htm (accessed May 31, 2007).

9 The figure is mentioned in a report by the International Crisis Group, “Sri Lanka’s Human Rights Crisis,” June 14, 2007, http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/RWFiles2007.nsf/FilesByRWDocUnidFilename/DBC51E0313E10AB5852572FA006892C6-Full_Report.pdf/$File/Full_Report.pdf (accessed July 18, 2007), which cites "Sri Lanka Human Rights Update," INFORM and Law and Society Trust, March 15, 2007.

10 Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process (SCOPP), “Baseless Allegations of Abductions and Disappearances,” March 8, 2007.

11 “International Independent Group of Eminent Persons Public Statement,” June 11, 2007. For the full text of the statement see http://www.medico-international.de/en/projects/srilanka/watch/20070611iigep.pdf (accessed June 28, 2007).

12 “International Independent Group of Eminent Persons Public Statement,” June 15, 2007. For the full text of the statement see http://www.medico-international.de/en/projects/srilanka/watch/20070615iigep.pdf (accessed July 2, 2007).

13 A UN human rights monitoring mission would entail a field office of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights with a mandate of protection, monitoring, capacity building, and public reporting.