V. Discrimination in Planning

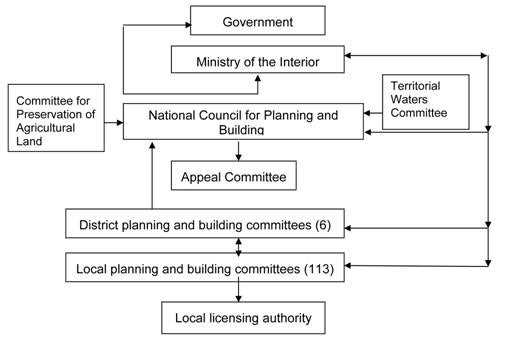

The 1965 Planning and Building Law centralized planning under the Ministry of Interior. The law creates a three-tiered structure with national, district, and local levels. Each tier is responsible for creating master plans and implementing approved plans in the areas under its jurisdiction.

At the highest level, the National Board for Planning and Building (National Board) prepares a national master plan and submits it to the government, which accepts, rejects, or amends it. Individuals have no right to lodge formal objections to national master plans. The approved national master plan represents the vision for the future development of the country. It dictates everything from land use to transportation, electricity and water networks, and industrial development.109

Under the National Board there are district Planning and Building Commissions (District Commissions), and in each District there are multiple Local Planning and Building Commissions (Local Commissions). Some of these represent just one community and are part of the locally elected authority; others cover several communities and are appointed by the minister of interior (see below).110

Bedouin Needs Not Met

Israel’s current national Master Plan, known as TAMA 35, fails to address the needs of the Bedouin population.112 The plan ignores the existence of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, which are not even marked on the maps of TAMA 35. The plan does not mention the population of these villages nor propose solutions to the desperate living situation of the tens of thousands of Bedouin citizens living in these communities. According to researchers at the Israeli organization Adva:

The phenomenon of excluding the Bedouin from government master plans is not a new one: the state, through its planning bodies, has acted this way for years. In a number of major regional master plans, the “unrecognized” Bedouin villages went totally unmarked, as if they did not exist, or their locations were marked as intended for public use such as sewerage works, public parks or industrial areas. Such plans included the 1972 district plan, the 1991 “Negev Front (Kidmat Negev) Plan,” the 1995 greater Beersheba metropolitan plan, and the 1998 renewed district plan.113

Rather than addressing existing inequalities, Israeli master plans and proposed new Jewish settlements appear to perpetuate them by consolidating state control over as much Bedouin land as possible while confining Bedouin in the smallest areas possible and breaking up the contiguity of Bedouin areas. Dr. Amer al-Hozayel, a planner with the municipality of Rahat, one of the seven government-planned townships, demonstrated to Human Rights Watch on maps how these goals were carried out in the Beer Sheva Metropolitan plan. He explained:

The goal of the plan is to expand Beer Sheva, and it clearly does this to the east—where 90 percent of the unrecognized villages lie—rather than to the north or west, which are relatively open areas. The plan also created new towns which the Israelis call “disconnecting and surrounding.” The black triangles show where new Jewish towns are being planned or built, and you can clearly see how they break up the continuity of the Bedouin areas and prevent expansion of the current Bedouin locales. Look at [the newly established Jewish town of] Givaot Bar—its goal is to prevent Rahat from expanding southwards. There is a Jewish town Omerit planned between these two unrecognized villages of Bir al-Mshash and al-Zarnung which breaks the link between them. In order to break up Bedouin continuity between Beer Sheva and Dimona they are planning a new Jewish town around [the unrecognized village of] al-Sdeir and another on top of the [unrecognized] village of Um Ratam.114

Al-Hozayel’s allegations have been echoed by various government officials. On July 21, 2002, the government issued Decision No. 2265 to establish 14 new settlements, six of them in the Negev. At the government meeting where the decision was made Minister Yitzhak Levi said, “The settlements are intended to stop the spread of illegal Arab settlements.” At the same meeting, then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon said “If we do not settle the land, someone else will do so.”115 In July 2003 the government began promoting an additional plan for 30 new settlements in the Galilee and the Negev. In a July 2003 interview regarding this new plan, then-Advisor to the Prime Minister on Settlements Affairs Uzi Keren said “[an] important issue in the establishment of these settlements is closing breaches, or locating settlements in policy terms, in the places that are important to the state, that is, for Jewish settlement... this is simply to strengthen settlement in areas sparse in Jewish population.”116

Even while the government has created the nine newly-recognized or established Bedouin villages/townships in the Negev, unlike their Jewish counterparts, they have stagnated from lack of funds and political will. One official who advised the Abu Basma Regional Council, in which the nine communities are located, told Human Rights Watch:

In Abu Basma, what have they delivered? People want electricity, water, paved roads. Kalaji [head of Abu Basma] failed to deliver in these areas. He started only now, after two years and three months, to do anything. He paved one main road in Abu Karinat. He started to build schools in Qasr Sir and Abu Karinat and some public buildings. That’s it. Not more than that. None of these villages have water or electricity yet. There is a new generation of Bedouin today who can see what is happening in Jewish communities and make the comparison. When the government wanted to establish Givaot Bar it only took a couple of months to deliver water, electricity, and a paved road.117

On July 18, 2005, the Ministerial Committee on the Non-Jewish Sector, chaired by then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, announced “a comprehensive development plan for the Abu Basma Regional Council.” The government promised to invest NIS 470 million over three years (2005-08) to develop education, health, employment, and social services and to provide utilities, infrastructure, housing, and agricultural lands.118 Yet government ministries have handed over little of this money. In 2005 Abu Basma was supposed to receive NIS 30 million from the ILA for planning and construction, NIS 14 million from the Ministry of Transport for building roads, and NIS 4.6 million for the Ministry of Health for constructing and maintaining health facilities. In fact, the council received only NIS 210,000 for construction and planning, NIS 56,000 for sanitation, and NIS 318,000 for water infrastructure.119 When Human Rights Watch visited several of the Abu Basma villages in March and April 2006, they were indistinguishable from their unrecognized neighbors.

Government officials admit that the money has not been forthcoming. The head of the Ministry of Interior for the Southern Region, Dudu Cohen, told a Knesset committee debate, “The ministries are supposed to pass the money on to the council. They do not transfer the money itself, but authorizations, irregular allocations and so on. When there are budgetary cutbacks in a certain ministry, it will cut wherever it wants, it doesn't ask me or the government. We follow this and always try to understand where the budget intended for Abu Basma disappeared.”120

Absence of Planning Participation and Consultation of Bedouin

In Israel, planning is highly centralized and, by law, the only way for individuals to participate in the process is by submitting objections to particular plans. Large parts of the system do not encourage participation or protect the right of various sectors of society to be fairly represented.

In 2000, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that land and other resources should be allocated according to principles of distributive justice.121 In 2004, the Israeli Planning Association adopted a code of ethics supporting the need for consultation with minority communities and the obligation to pursue the well-being and empowerment of all members of society.122

Yet in practical terms, Israel’s Arab citizens, especially the Bedouin, remain systematically marginalized in the planning process. First, they are very thinly represented on any of the planning committees. Second, the master plans rarely take their needs into account. Israeli planning authorities have created plans to address the needs of particular communities—for example, the National Master Plan TAMA 31 in the 1990s dealt with the absorption of a large number of immigrants from the former Soviet Union. However, planning authorities have never designed a master plan to address the needs of the Arab community, even though Arab communities rank among the most distressed, with chronic land and housing shortages, poor economies, and low employment opportunities.123 Regional master plans have also never properly addressed the dire need of the Bedouin of the Negev for adequate housing and residential options.

When the Southern District Plan (TAMAM 4/14) was first formulated, it completely ignored the existence and needs of the Bedouin in the unrecognized villages. After the Association for Civil Rights in Israel (representing the villagers, the RCUV, and Dukium) petitioned the Israeli Supreme Court, the planning authorities acknowledged the discrimination and, in July 2001, as part of a settlement with the court, agreed to meet with the petitioners and representatives of the communities to discuss ways to integrate the housing and residential needs of the residents of the unrecognized villages into the Master Plan.124 However, this process has dragged on for seven years; while some improvements have been made, the Plan still ignores the needs of most of the unrecognized villages.

Ariel Dloomy of Dukium described the consultation process to Human Rights Watch:

We petitioned the High Court of Justice to include Bedouin representatives and relevant NGOs in the master plan for the Negev, the Metropolitan Beer Sheva plan. They agreed. According to the court the working group for the Beer Sheva Metropolitan plan was obliged to consult with us. The working group invited us just two or three times. I took part in two meetings, and they just showed us the plan, briefly let us speak, ignored us and moved on. It was very depressing. Banna [Shoughry-Badarne, a lawyer with the Association for Civil Rights in Israel] had produced lengthy, detailed objections to the current plan and detailed alternatives, created with planners, and they gave her just a few minutes to present, ignored her, and moved on. Our opinions were never really taken into account, and when they claim that they consulted Bedouin and their allies and included us in the planning process, it is not accurate. It never really happens.125

Lack of Local Representation

By law the minister of interior can determine which communities will be accorded their own local commissions (which are part of their elected local governments) and which communities will be joined together as part of a larger local planning area (to be governed by a ministry-appointed local commission).126 Only 6 percent of Arab localities have an elected local commission, as opposed to 55 percent of Jewish localities. According to planners with the Israeli planning rights organization, Bimkom:

The importance of a local planning commission is implicit in, among other things, its ability to initiate a plan for a community and to issue building permits, an authority which gives the local authority a certain degree of planning autonomy. In the present circumstances, most Arab towns, except for relatively large ones, and even those designated formally as cities, are not authorized to, and cannot, initiate a plan or issue building permits. These places are dependent on decisions made by planning commissions on which, in the main, they have no representation….127

Indeed, only three Arab members out of a total of 32 sit on the National Board.128 The Northern and Southern District Commissions each have only two Arab members out of 17 members129

Local commissions that are part of the elected leadership of a community are more likely to be in touch with the wishes of their constituencies and to try to respond favorably to their needs. An elected local commission also provides avenues for greater community participation in the planning process and is accountable to community residents. Conversely, in communities that have ministry-appointed local commissions, the central government has great control over planning and development, with minimal participation from affected populations and no means for residents to hold the local commission accountable.

Each newly recognized Bedouin village in the Negev has representatives sitting on the Abu Basma Regional Council, but the villagers did not democratically elect their representatives, who were appointed by government officials.130 The Abu Basma Regional Council also suffers from a dearth of Bedouin staff and is headed by a ministry-appointed Jewish mayor who runs the council from his office in Jerusalem. When asked at a Knesset committee debate about the lack of genuine Bedouin representation and involvement in Abu Basma, the minister of interior refused to answer and also forbade his deputy to do so.131

The head of the Ministry of Interior for the Southern Region, Dudu Cohen, claimed that the appointed Bedouin representatives on Abu Basma Regional Council were consulted with regard to the planning of the newly recognized villages in the Negev. However, in a particularly candid admission, he confirmed that these individuals were not selected by the community, but rather chosen by himself, by the department responsible for Bedouin affairs in the ILA, or by the police. When a member of the Knesset suggested that community organizations could better choose representatives from their community, Cohen retorted, "Unfortunately the organizations do not represent the residents … [the council and the police] make recommendations based on their knowledge of the structure of the tribe, the family, the influential persons of the community, and they know them all very well."132

At the far end of the spectrum, when it comes to local planning, lie the Bedouin unrecognized villages of the Negev. Since these villages are not officially recognized as residential localities, they do not fall under any local authority or the jurisdiction of any local commissions. As a result, they have no vehicle through which to propose municipal plans for their localities or determine the future of their communities. Since the submission and approval of a master plan represents the only way to build legally, they are forever stuck in a vicious cycle—no plan, no permits, and no legal community; no legal community, no possibility to plan and issue building permits. The only time that planning commissions (on which the Bedouin unrecognized villages are never represented) address the unrecognized villages is when they approve home demolition orders in unrecognized villages that sit on land under their jurisdiction.

No Criteria for Recognizing Communities

There are no clear criteria in Israeli law for determining when a new community will be created or when a locality can apply for and be granted official recognition. The age and size of the community do not seem to be relevant factors. Even though the Bedouin villages existed prior to the creation of the 1965 law, they were not included in the original master plans. Thus while Jewish communities with as few as one family acquire recognition, Bedouin villages with hundreds or even thousands of residents do not.

Existing master plans articulate some general principles. For example, TAMA 35 states that a new community can be established when “a planning institute has been convinced that a new town or village should be established.”133 This vague benchmark provides ample room for maneuvering by savvy local planning commissions, while providing little opportunity for underrepresented communities such as the Bedouin. According to the policies of the Ministry of Interior, government officials must inspect an unrecognized village to determine whether it should attain recognition. But the Ministry of Interior has never conducted a thorough examination of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev to determine whether they merit recognition, even though Bedouin villagers filed a petition to Israel’s Supreme Court in 1991 asking the ministry to do so.134

Since 1948, the state has built over one hundred small Jewish communities in the Negev, many of them with huge tracts of agricultural land, some of them on ancestral Bedouin villages. The website of the Sha’ar HaNegev Regional Council in the Western Negev boasts, “Every kibbutz in the region has well-developed agricultural areas that extend over thousands of acres of field crops, orchards, dairies and chicken houses.”135 After Israel evacuated settlers from the Gaza Strip in 2005, many evacuee communities expressed their wish for new agricultural villages where they could continue to live as a community and pursue a rural and agricultural way of life. This demand is not dissimilar to that of the Bedouin, but in the settlers’ case the government addressed it swiftly. One example is the village of Shomria, in the Bnei Shimon Regional Council in the Negev. The authorities reestablished the village of Shomria, a former kibbutz, for the evacuees from the Gaza settlement of Atzmona. Due to fast-track planning and generous government budgets, just nine months after the Gaza evacuation more than 400 people were living in Shomria in temporary accommodation. Residents inaugurated the first permanent building in Shomria a year-and-a-half after the evacuation.136 The government has planned, financed, and developed similar communities in the immediate aftermath of the evacuation.137

Retroactive Legalization and Changed Zoning

One of the problems of the unrecognized villages, as mentioned previously, is that in the original Israeli master plan the government zoned the land that the villages already occupied as non-residential land, in most cases agricultural land. Under Israeli law it is illegal to plan or build buildings on land that is not zoned as residential. Planning authorities have zoned other areas of the Negev for military purposes, also off-limits for housing. On March 29, 2006, Human Rights Watch drove past the unrecognized village pictured below on the road to the unrecognized village of Um al-Hieran. Salim Abu Alqian told Human Rights Watch that although the village had been there for decades, in recent years the military put up firing zone signs forbidding entry.138

Firing Zone sign with unrecognized village in the background. A resident of a neighboring unrecognized village said the signs went up in the last couple of years, decades after the village was established. © 2006 Lucy Mair/Human Rights Watch

Dr. Amer al-Hozayel described the signs in front of this village as part of the government’s broader strategy for Bedouin land confiscation in the Negev:

The government has a strategy to suddenly declare that areas in the Negev, where unrecognized villages are often located, are closed military zones. There are two large areas that have been affected by this, a Southern one that was declared in 1998 and the one in the area of Um al-Hieran that was declared after 2000. However, it is all a trick. After the government declares them as closed military areas and tries to evict everyone living there they plan to use this land for new Jewish towns. We know this for a fact since we received internal documents leaked from a sympathetic source in the ILA that detail the new Jewish towns planned for those areas. In 2001 we published a map with all the contours of the declared military areas and the names of the new Jewish towns planned for those areas [see map at beginning of this report]. The ILA was shocked that we knew about its plans. The southern closed military zone measures 141,000 dunams and 42,000 dunams of that belongs to unrecognized villages. Two unrecognized villages fall fully within the military zone—al-Mizra and Gatamat al-Mathar. The other military zone around Um [al-]Hieran encompasses 50,000 dunams 12,500 acres, and 18,125 dunams of that belongs to unrecognized villages.139

On the other hand, when the government seeks to establish new Jewish communities, non-residential zoning does not stand in its way. In the Hevel Lachish Regional Council near Kiryat Gat, in the Negev, officials are planning to build four or five new communities for the Gaza evacuees—one of them, Mirsham, on 1,500 dunams of lands formerly zoned for agriculture and forest.140 In another example, in February 2007, Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and Defense Minister Amir Peretz agreed to change the boundaries of an IDF live-fire zone in eastern Lachish in the Negev to create the community of Gvaot Hazan for evacuees from the Neveh Dekalim settlement in Gaza. In the government press release on the decision, Olmert said, “If there is anything worth canceling a firing zone for, it is the establishment of life in this country.”141

The planning process is riddled with inconsistencies. In cases where construction by Jewish Israelis occurred contrary to the plan and without obtaining necessary permits, the authorities provide retroactive legalization. One example is the individual farms mentioned in Chapter IV, many of which had not secured appropriate zoning and building permits at the time they were built and which are now being retroactively legalized.142

109 The Planning and Building Law - 1965, Sefer HaHokim, 467,p. 307.

110 Ibid.

111Rachelle Alterman, ed., “National-Level Planning in Israel: Walking the Tightrope Between Government Control and Privatisation”, in National-Level Planning in Democratic Countries, an International Comparison of City and Regional Policy-Making (Liverpool University Press, 2001).

112 Integrated National Master Plan for Building, Development and Preservation – TAMA 35, approved at the end of 2005.

113 Swirski and Hasson, Invisible Citizens, p. 12.

114 Human Rights Watch interview with Amer al-Hozayel, Rahat, April 3, 2006.

115 D. Bachor, “The Government Approved th eEstablishment of 14 New Community Settlements,” YNET, July 21, 2002 [Hebrew], as quoted in Hana Hamdan, “The Policy of Settlement and ‘Spatial Judaization’ in the Naqab,” Adalah Newsletter, Vol. 11, March 2005.

116 Interview broadcast on Israel’s Channel 2 Radio on July 20, 2003, as quoted in Hamdan, “The Policy of Settlement,” Adalah Newsletter.

117 Human Rights Watch interview with Thabet Abu Ras, Beer Sheva, April 5, 2006.

118 “Comprehensive Development Plan for Abu Basma Regional Council Approved,” Prime Minister’s Office press release, July 18, 2005, http://www.pm.gov.il/PMOEng/Archive/Press+Releases/2005/07/spokmes180705.htm (accessed May 23, 2007).

119 Planned allocations appear on Budget Complements for Abu Basma Regional Council, Government Decision 3956, July 22, 2005, http://www.pmo.gov.il/PMO/Archive/Decisions/2005/07/des3956.htm. [Hebrew] (accessed May 25, 2007). Abu Basma financial activity on "Annual Supervised Financial report For Regional Council Abu Basma", Department for the Inspection of Local Authorities in the Ministry of the Interior, September 28, 2006. http://www.moin.gov.il/apps/pubwebsite/MainMenu.nsf/ [Hebrew] (accessed May 25, 2007).

120 Protocol of 11/06/2006 meeting of the Knesset Internal Affairs and Environment Committee on Master plans of Bedouin settlements in the Negev and home demolitions. http://www.knesset.gov.il/protocols/data/html/pnim/2006-11-06.html [Hebrew] (accessed May 23, 2007).

121Siach Hadash [New Discourse] v. the Minister of Infrastructure (H.C. 244/00), para. 39. According to one definition, “Distributive justice is concerned with the fair allocation of resources among diverse members of a community. Fair allocation typically takes into account the total amount of goods to be distributed, the distributing procedure, and the pattern of distribution that results.” http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/distributive_justice/. (accessed November 20, 2007).

122 Israeli Planning Association, Code of Ethics, 2004.

123 See Chapter VII for information on the poor socio-economic status of Bedouin government-planned townships.

124 Email from Banna Shougry-Badarne to Human Rights Watch, June 18, 2007.

125 Human Rights Watch interview with Ariel Dloomy, Rahat, March 29, 2006. Banna is a lawyer from the Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI).

126 In areas where a local committee includes the area of more than one local authority, the Minister of Interior appoints an eight-member local committee, consisting of the official in charge of the district or his/her representative, and another seven members whom the Minister appoints from among a list recommended by the local authorities. Representation is not mandatory for all authorities. From: Hana Hamdan and Yosef Jabareen, “A Proposal for Suitable Representation of the Arab Minority in Israel’s National Planning System,” Adalah Newsletter, Vol. 23, March 2006.

127 Groag and Hartman, “Planning Rights in Arab Communities in Israel.”

128 Hamdan and Jabareen, “A Proposal for Suitable Representation.”

129 In the Northern District Planning and Building Committee there are two Palestinian members (men) out of 17, even though Palestinians make up more than half of the district’s population. The Southern District Planning and Building Commission covering the Negev also has only one Bedouin member: the mayor of Rahat.

130 In December 2003 the Ministry of Interior created the Abu Basma Regional Council, which was officially launched on February 3, 2004. The Ministry tasked Abu Basma Regional Council with running the newly-recognized Bedouin villages.

131Protocol of November 6, 2006 meeting of the Knesset Internal Affairs and Environment Committee on Master plans of Bedouin settlements in the Negev and home demolitions. http://www.knesset.gov.il/protocols/data/html/pnim/2006-11-06.html [Hebrew] (accessed May 23, 2007).

132 Ibid.

133 A plan for a new community will be approved after HOLENTA (the Committee of Fundamental Planning) presents its recommendations to the National Council.” TAMA 35 (National Master Plan) – Directives, November 2000, p. 20, http://www.moin.gov.il/Apps/PubWebSite/publications.nsf/All/7DCAB7169E94789F42256A01003B7C57/$FILE/Publications.pdf?OpenElement [Hebrew] (accessed September 17, 2007).

134 Court Case 1991/00. In a settlement with the Court, the Ministry agreed to conduct an examination that the Court was supposed to supervise. This has never happened. Email from Banna Shoughry-Badarne to Human Rights Watch, June 18, 2007.

135 Sha’ar Ha Negev Regional Council website, http://www.sng.org.il/english-site/first.htm (accessed May 23, 2007).

136 Information on Shomria from Bnei Shimon Regional Council website. See: http://www.bns.org.il/site/he/eCity.asp?pi=2370; http://www.bns.org.il/site/he/eCity.asp?pi=2386&doc_id=12434; and http://www.bns.org.il/site/he/eCity.asp?pi=2386&doc_id=13308

(accessed March 25, 2007).

137 See, for example, Israeli government Cabinet Meeting minutes, May 7, 2006 (on file with Human Rights Watch), recording approval for a three-year development plan for the Halutzit dunes communities at a cost of NIS 159.2 for the first phase. The government also tasked a team of directors-general of various ministries to prepare a three-year plan for the establishment of residential communities in the Lachish district including expanding Amatzia, Shomriya, and Sheke that also housed Gaza evacuees. Finally, they decided to allocate NIS 70 million to the Construction and Housing Ministry for the planning needs at another new community, Yesodot.

138 Human Rights Watch interview with Salim Abu Alqian, Um al-Hieran, March 29, 2006.

139 Human Rights Watch interview with Amer al-Hozayel, Rahat, April 3, 2006. While Human Rights Watch has not seen the leaked ILA documents referred to by Dr. al-Hozayel, we have seen the subsequent maps mapping the closed military zones and the new Jewish villages planned or built in those areas.

140 Taken from the Lachish website, http://www.lachish.org.il (accessed February 12, 2007).

141 “Agreement to Enable the Establishment of the Gvaot Hazan Community for Evacuees from Neveh Dekalim,” Government press release, February 11, 2007.

142 Retroactive legalization of illegal Jewish building occurs in the occupied West Bank as well. One such case involves the settlement of Modiin Illit in the West Bank where an entire new neighborhood of 1,500 apartments was built illegally since the apartments were not part of the original master plan. This illegal building was recently retroactively legalized by the Supreme Planning Council for Judea and Samaria. See Akiva Eldar, “Planning council approves illegal West Bank building plan,” Haaretz, February 25, 2007, http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/829740.html (accessed February 25, 2007).