No Tally of the Anguish

Accountability in Maternal Health Care in India

Abbreviations

ANC Antenatal care

ANM Auxiliary Nurse-Midwife

APH Antepartum hemorrhage

ASHA Accredited Social Health Activist

AWW Anganwadi worker

BPL Below poverty line

CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

CESCR UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

CHC Community health center

CMO Chief medical officer

CRC Convention on the Rights of the Child

CSSM Child Survival and Safe Motherhood forms

DLHS District Level Household and Facility Survey

FIGO International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

FOGSI Federation of Obstetric and Gynecological Societies of India

FRU First referral unit

HMIS Health Management Information System

HSC Health sub-center

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

ICESCR International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

ICM International Confederation of Midwives

IFA Iron and folic acid

IMA Indian Medical Association

JSYJanani Suraksha Yojana, literally Motherhood Protection Scheme

MAPEDIR Maternal and perinatal death inquiry and response

MCH Maternal and child health

MDGs Millennium Development Goals

MMR Maternal mortality ratio

MMWG Maternal Mortality Working Group

MOIC Medical officer-in charge

NFHS National Family and Health Survey

NRHM National Rural Health Mission

PHC Primary health center

PNC Postnatal care

PPH Post-partum hemorrhage

RCH Reproductive and child health (program)

RKSRogi Kalyan Samitis, or Patient Welfare Committees

SHC Sub-health center

SR Special Rapporteur

SRS Sample Registration System

UN United Nations

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund

UNICEFUnited Nations Children's Fund

UP Uttar Pradesh state

USAID United States Agency for International Development

WHO World Health Organization

Glossary

Accredited Social Health Activist |

A female health worker appointed under the National Rural Health Mission |

Anganwadi |

Government-run early childhood care and education center. Anganwadi workers' duties include providing nutritional supplements to pregnant and lactating mothers |

Antenatal care |

Care during pregnancy (termed "prenatal care" in American English) |

Antepartum hemorrhage |

Bleeding during pregnancy |

Auxiliary Nurse-Midwife |

A field based health worker usually posted in health sub-centers and primary health centers |

Basic obstetric care |

Obstetric care that includes the ability to conduct normal and assisted deliveries, and manage pregnancy complications by intravenously introducing or injecting anticonvulsants, oxytocic drugs (drugs that expand the cervix or vagina to facilitate delivery), and antibiotics |

Block |

Administrative division of a district |

Chief medical officer |

Highest district level health official in Uttar Pradesh; the equivalent in Tamil Nadu is the deputy director of health services |

Community health center |

Thirty-bed government health facilities in rural India providing secondary health care |

Dalit |

So-called "untouchables," traditionally considered outcastes in India |

District |

Administrative division of a state |

District Level Household and Facility Survey |

A periodic all-India survey conducted under the World Bank funded RCH-II program |

Eclampsia |

Pregnancy complication characterized by seizures or coma |

Emergency obstetric care |

Obstetric care that includes the ability to provide life-saving interventions through surgery (cesarean sections) and blood transfusions |

First referral unit |

A government health facility in India that should be equipped with comprehensive emergency obstetric care facilities and serves as the first hospital in the referral chain when health complications arise that cannot be dealt with at lower-level facilities |

Gram Panchayat |

Literally meaning "assembly of five," a term used to refer to the village-level councils of elected government representatives |

Gram Sabhas |

A cluster of villages governed by a village council |

Gram Vikas Adhikari |

Village development officer |

Janani Suraksha Yojana |

Literally Motherhood Protection Scheme, an NRHM scheme that promotes facility-based deliveries through cash incentives for pregnant women and community-based female health volunteers |

Maternal death |

Death during pregnancy or within 42 days of childbirth or abortion, caused directly or indirectly by pregnancy |

Maternal mortality ratio |

Number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births |

Maternal Mortality Working Group |

Comprised of the WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, the UN Population Division, and the World Bank, as well as several outside technical experts |

Millennium Development Goals |

Eight goals that 189 countries have pledged to achieve by 2015, including a 75 percent maternal mortality reduction compared to its 1990 levels (MDG 5) |

National Family and Health Survey |

A periodic all-India sample survey funded by the Indian government and international agencies |

National Rural Health Mission |

The Indian government's flagship program on rural health care for the period 2005-2012 |

Obstetric fistula |

Tissue damage between the vagina and bladder or rectum leading to incontinence |

Panchayat Mitras |

Literally, friends of the village council |

Postnatal period |

42 days from termination of pregnancy |

Postnatal care |

Health care for women after termination of pregnancy up to 42 days from date of termination of pregnancy |

Post-partum hemorrhage |

Bleeding immediately after delivery |

Primary health center |

Basic health facility in rural areas catering to a population of 30,000 |

Rogi Kalyan Samitis |

Patient Welfare Committees, committees at government health facilities |

Scheduled caste |

Phrase under Indian law for Dalits |

Scheduled tribes |

Phrase under Indian law for adivasis or tribal communities |

Sepsis |

Severe infection spreading through the bloodstream |

Sub-health center |

Basic health facility in rural areas catering to a population of 5,000 |

Termination of pregnancy |

The end of a pregnancy, whether through delivery, miscarriage, or abortion |

UN guidelines |

1997 United Nations Guidelines for Availability and Utilization of Obstetric Services |

UN process indicators |

UN Process Indicators for Availability and Utilization of Obstetric Services |

Summary

Who asks what happened afterwards? ... If a person dies, she dies. If someone hangs himself then it becomes a police case. But if someone dies in a hospital then no one cares.

- Suresh S., neighbor of deceased pregnant woman, Uttar Pradesh, March 2, 2009.

For an emerging global economic power famous for its medical prowess, India continues to have unacceptably high maternal mortality levels. In 2005, the last year for which international data is available, India's maternal mortality ratio was 16 times that of Russia, 10 times that of China, and 4 times higher than in Brazil.[1] Of every 70 Indian girls who reach reproductive age, one will eventually die because of pregnancy, childbirth, or unsafe abortion, compared to one in 7,300 in the developed world. More will suffer preventable injuries, infections, and disabilities, often serious and lasting a lifetime, due to failures in maternal care.

"Destiny" or "fate" brought this upon them, say many of the families that experience maternal deaths, unaware that as many as three in four might be prevented if all women and girls had access to appropriate health care.

After more than a decade of programming for reproductive and child health with few results, the Indian government acknowledged the problem and in 2005 took steps under its flagship National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) to improve public health systems and reduce maternal mortality in particular. Recent data suggest it is having some success: all-India figures show a decline in maternal deaths between 2003 and 2006.

This decline, however, is small in relation to the scope of the problem, and camouflages disparities. Some states like Haryana and Punjab actually showed an increase in maternal mortality. And significant disparities based on income, caste, place of residence, and other arbitrary factors persist even within every state, including those that appear to be improving access to care for pregnant women and mothers. Poor maternal health is far too prevalent in many communities, particularly marginalized Dalit (so-called "untouchable"), other lower caste, and tribal communities.

One step the Indian government has already taken is to increase women's demand for deliveries in health facilities, on the assumption that doing so will promote safe deliveries. National and state officials are also taking steps to upgrade public health facilities to improve the standard of care. They are also making efforts to improve monitoring of health parameters through a new Health Management Information System, and are launching an annual health survey in some key states to boost the levels of health-related information.

These steps are important and, indeed, suggest India has the potential to be a leader among developing countries in attacking maternal mortality and meeting the international commitments spelled out in the "Millennium Development Goal" on maternal mortality. This will be possible, however, only if officials do more to diagnose and steadily improve healthcare systems, programs, and practices by addressing barriers to care and filling health system gaps. And it will be possible only if officials do more to ensure that policies make a difference in the lives of all women and girls, regardless of their background, income level, caste, religion, number of children, place of residence, and other arbitrary factors.

Human Rights Watch believes that a critical issue, one that has received inadequate attention to date, is healthcare system accountability. Accountability, a central human rights principle, is integral to the progressive realization of women's right to sexual and reproductive health and to the realization of the Millennium Development Goal on maternal mortality reduction.

We conducted research in India between November 2008 and August 2009. The work included field investigations with victims and families in Uttar Pradesh and consultations with experts and activists there and in other parts of India. We chose Uttar Pradesh as the locus for field investigation because it has one of the highest maternal mortality ratios and because it is among those states that have introduced an executive order requiring all maternal deaths to be investigated.

Targeted Interventions Generally speaking, maternal mortality is high where womens overall status is low and public health systems are poor. India is no exception and efforts to bolster womens rights and strengthen the healthcare system as a whole must be an important part of efforts to curb maternal mortality. Even so, targeted interventionsbetter access to skilled birth attendance, emergency obstetric care, and improved referral systems, with particular attention to underserved communitieshave been proven to make a significant contribution to reducing maternal deaths, disease, and injury. |

Our research identified four important reasons for the continuing high maternal mortality rate in Uttar Pradesh: barriers to emergency care, poor referral practices, gaps in continuity of care, and improper demands for payment as a condition for delivery of healthcare services.

We also found serious shortcomings in the tools used by authorities to monitor healthcare system performance, identify flaws, and intervene in time to make a difference. While accountability measures may seem dry or abstract, they literally can be a matter of life and death.

As detailed below, we believe that failures in two key areas of accountability are an important reason that many women and girls in states like Uttar Pradesh are needlessly dying or suffering serious harm during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period:

- Failures to gather the necessary information at the district level on where, when, and why deaths and injuries are occurring so that appropriate remedies can be devised; and

- Failures of grievance and redress mechanisms, including emergency response systems.

Disparities: From Global to Local

Globally, more than half a million women and girls die every year because of pregnancy, childbirth, and unsafe abortions (maternal deaths). Nearly 80 percent of these deaths are directly linked to obstetric complications such as hemorrhage, obstructed labor, or eclampsia (pregnancy-related seizures). Many women die during pregnancy or after childbirth due to indirect causes such as tuberculosis, hepatitis, and malaria. Thousands more-about 20-30 times the numbers who die-are still left with infections, or suffer injuries or disabilities such as obstetric fistula due to pregnancy-related complications. Many others suffer pregnancies ridden with health problems such as anemia and night blindness.

The direct medical cause of any particular death explains just part of the story. Typically, a maternal death marks the tragic ending of an already complex story with different elements-socio-economic, cultural, and medical-operating at different levels- individual, household, community, and so on. Factors contributing to maternal death include early marriage, women's poor control over access to and use of contraceptives, husbands or mothers-in-law dictating women's care-seeking behavior, overall poor health including poor nutrition, poverty, lack of health education and awareness, domestic violence, and poor access to quality health care, including obstetric services.

Measures of maternal deaths and morbidities illustrate the vast disparities in global health and access to health care worldwide. Developing countries, including India, bear 99 percent of global maternal mortality. Latest available international figures from 2005 show that India alone contributes to a little under a fourth of the world's maternal mortality, with a maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of 450 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births (compared with Ireland's MMR of 1 and Sierra Leone's 5,400).[2]

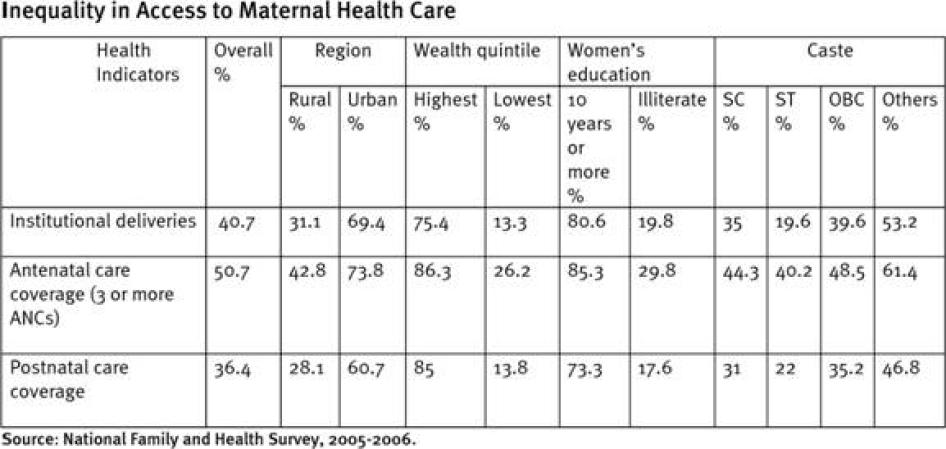

In-country disparities in maternal mortality are huge, with Uttar Pradesh state in north India having one of the highest MMRs, with nearly three times as much as southern Tamil Nadu state. Even within a state, the access to and utilization of maternal health care varies based on region (rural or urban), caste, religion, income, and education. For instance, a 2007 UNICEF study in six northern states in India revealed that 61 percent of the maternal deaths documented in the study occurred in Dalit (so-called "untouchables") and tribal communities.

Recurrent Healthcare System Failures

Indian government policies and programs aim to provide poor rural women with free access to comprehensive emergency obstetric care to save them from life-threatening complications during childbirth. Despite this, thousands of women continue to die because of complications including hemorrhage, obstructed labor, or hypertensive disorders.

The Indian central government's seven-year flagship rural healthcare program, the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), has ushered in many changes in rural health care, especially maternal health care. It provides for a range of "concrete service guarantees" for the rural poor, including free care before and during childbirth, in-patient hospital services, comprehensive emergency obstetric care, referral in case of complication, and postnatal care. But, critically, it fails to monitor whether these standards are actually being met on the ground and ensure that women are aware of them. The result is recurring health system or program gaps that are not being effectively addressed in practice.

Our research in Uttar Pradesh shows that while health authorities are upgrading public health facilities, they have a long way to go. Currently, a majority of public health facilities that are supposed to provide basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care have yet to do so. A health worker trained in midwifery can do very little to save the life of a pregnant woman unless she is supported by a functioning health system including an adequate supply of drugs for obstetric first aid, emergency obstetric care, and referral systems for complications such as hemorrhage, obstructed labor, and hypertensive disorders.

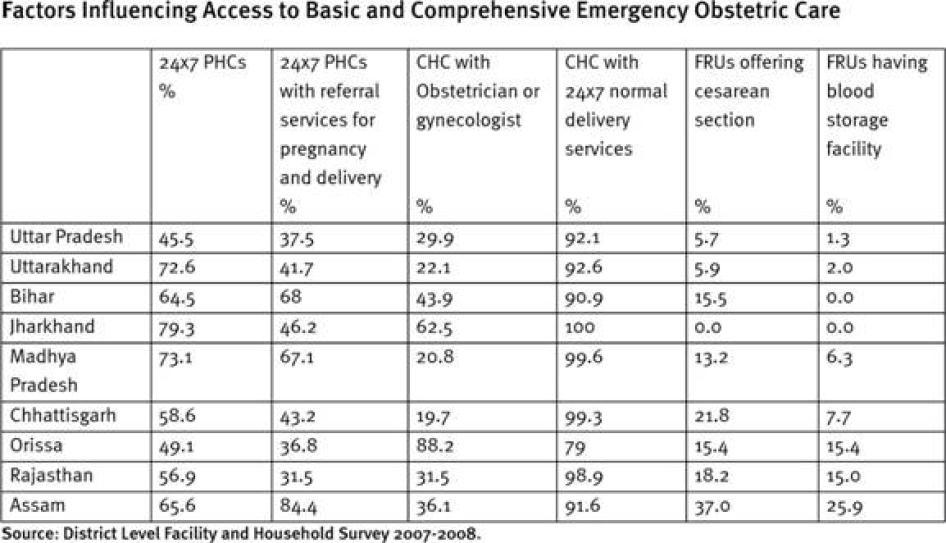

For example, most health staff in community health centers of Uttar Pradesh said that they conducted only "normal deliveries." Women with complications were referred to another facility, with little or no referral support. Uttar Pradesh has 583 fewer community health centers than Indian public health standards require. Less than a third of existing community health centers have an obstetrician or gynecologist and about 45 percent do not have funds to operate even the one ambulance they have. In practice, roughly 1 in 20 first referral units (comprehensive emergency obstetric care facilities) in Uttar Pradesh offer caesarean sections and only 1 in 100 have a blood storage facility.

Staff at community health centers and district hospitals visited by Human Rights Watch in Uttar Pradesh reported referring women with pregnancy complications to facilities at times more than 100 kilometers (60 miles) away for a blood transfusion or cesarean section.

We do not have a gynecologist now. No blood facility. So if there is any case that needs blood we refer the case to Allahabad hospital-Sadguru Sewa Trust [more than 100 kilometers away] ... Only normal cases are taken here. We do not take critical cases. In my time [more than two years], we have had only one cesar case [caesarean] performed. - Health staff member at Chitrakoot district hospital, Uttar Pradesh, March 7, 2009. The hospital is supposed to be equipped with comprehensive emergency obstetric care facilities to address all pregnancy-related complications. |

Women are often referred from one health facility to another before reaching a clinic or hospital that is equipped to provide the emergency care they need. In the words of Trishna T. from rural Uttar Pradesh, who recalled her neighbor's frustrating experience of being sent away from a government health facility at the time of delivery: "What's the point of sending us away? If the doctor cannot deal with the case here, then why should we go to the doctor? For the 1400 rupees [US$28, the cash incentive given to women who deliver babies in hospitals or clinics]? Are we going all the way to kill ourselves?" Often such referrals are made without any support for emergency transport and information about whether the higher facility actually has the ability to deal with the complication.

From Bachrawan [comprehensive emergency obstetric care facility] they sent the case to the Rae Bareli hospital and from there they were asked to go to Lucknow hospital. They [the family] could not afford to go there [Lucknow] so they came back here [community health center]....But they [family] started falling at the doctor's [superintendent] feet and holding his hand and leg. So out of mercy he took her and got her admitted. Not into our ward [female ward]. We said no. So he took her into the male ward. She died. He did not want her to die on the road. There is nothing we could have done in that case. We do not have the facilities here. - Nirmala N., health staff member at a community health center, Uttar Pradesh, February 27, 2009, explaining a failed referral from their center. We took her [Kavita K.] to the community health center and they said, "We cannot look at this here." So we took her to [the hospital in] Hydergad. From Hydergad to Balrampur, and from there to Lucknow-all government hospitals. From Wednesday to Sunday-for five days- we took her from one hospital to another. No one wanted to admit her. In Lucknow they admitted her and started treatment. They treated her for about an hour and then she died. - Suraj S., father of Kavita K., Uttar Pradesh, February 27, 2009, recalling his experience when seeking medical assistance for Kavita after she developed postpartum complications. |

The best institutional delivery cannot save a pregnant woman or new mother unless she is cared for in the immediate postnatal period (24-72 hours) with follow-up care in case of complications thereafter. Poor continuity of care through the antenatal and postnatal periods has remained a persistent problem in states like Uttar Pradesh. A 2008 government survey reveals that there is a significant drop in care even within the immediate postnatal period of 48 hours of delivery in Uttar Pradesh.

Women and girls also face considerable financial barriers to care. Even though government programs guarantee a host of free services including out-patient obstetric services, drugs, and in-patient obstetric services such as comprehensive emergency obstetric care, in practice, the care is seldom free. The most obvious example is government discrimination among women on the basis of age and number of children while providing benefits under healthcare programs like the Mother Protection Scheme (Janani Suraksha Yojana or JSY). In many states, pregnant girls under the age of 19 or women and girls with more than two children are not entitled to benefits under the JSY even though young mothers and mothers with multiple pregnancies are especially in need of such medical attention.

Many health workers in hospitals and clinics make unlawful demands for money or payment as a condition for care. Often this is justified as a customary practice around childbirth where families "volunteer" money or gifts to celebrate childbirth. But such practices should be curbed because they impose a severe burden on poor families. In cases where free care is dependent on whether women belong to families holding cards certifying them as below the poverty line, non-issuance of such cards forms a significant barrier to access.

Nothing is free for anyone. What happens when we take a woman for delivery to the hospital is that she will have to pay for her cord to be cut... for medicines, some more money for the cleaning. The staff nurse will also ask for money. They do not ask the family directly ... We have to take it from the family and give it to them [staff nurses] ... And those of us [ASHAs] who don't listen to the staff nurse or if we threaten to complain, they make a note of us. They remember our faces and then the next time we go they don't treat our [delivery] cases well. They will look at us and say "referral" even if it is a normal case. - Niraja N., female community health worker or ASHA, Uttar Pradesh, February 26, 2009. One man I know had taken his wife for delivery to the CHC. He had sold 10 kilos of wheat that he had bought to get money to bring his wife for delivery. He had some 200-300 rupees [US$4-6]. Now in the CHC they asked him for a minimum of 500 rupees [US$10]. Another 50 [rupees] to cut the cord and 50 [rupees] for the sweeper. So he started begging and saying he did not have more money and that they should help for his wife's delivery. I... asked them why they were demanding money. The nurse started giving us such dirty [verbal] abuses that even I was getting embarrassed and wanted to leave. You imagine how an ordinary person must feel who wants help. - Activist from a local nongovernmental organization in Uttar Pradesh, March 2, 2009. |

Improving Accountability: The Critical Need for Need for Better Monitoring and Timely Investigations

Existing approaches have not done enough to ensure that district health authorities gather information about why existing healthcare programs are not being implemented as they should be. They lack critical information about blockages or gaps in the health system. The key issue here is effective monitoring: using maternal death investigations and appropriate monitoring indicators to obtain the data needed for interventions that save lives and reduce harm.

Central and state authorities often point to the number of facility-based deliveries as an important measure of progress. While this can be a useful measure-facility-based deliveries under some circumstances correlate with reduction in maternal mortality-it does not provide the necessary information on whether a mother actually survived the childbirth and postnatal period without injuries, infections, or disabilities.

"Institutional Deliveries" as a Measure of Progress The Mother Protection Scheme (Janani Suraksha Yojana or JSY) promotes hospital or clinic-based deliveries through cash incentives for pregnant women (1400 rupees, or US$28, in rural areas) and community-health workers with the objective of promoting safe deliveries through improved access to skilled birth attendance. In theory the JSY seeks to integrate the cash assistance with prenatal and postnatal care. Nearly 20 million Indian women delivered in health facilities between mid-2005 and March 2009, a reflection, authorities say, of the JSY incentives. The Indian central and state governments use the number of such institutional deliveries as a key measure of progress on maternal health. While the JSY has improved the demand for institutional deliveries, these statistics alone are not an adequate indicator of progress. While conducting field investigations in Uttar Pradesh, Human Rights Watch found that the number of institutional deliveries at health facilities was counted by keeping track of the number of women who received cash assistance. In several instances, women from rural areas claimed that health workers had approached them saying that they could deliver at home but tell authorities they delivered in the health facility, splitting the cash assistance with the health worker. More fundamentally, counting the number of institutional deliveries alone is misleading unless one monitors the actual outcome of pregnancies through the postnatal period. Currently missing is information on whether pregnant women who develop life-threatening complications such as hemorrhage, obstructed labor, and eclampsia (pregnancy-related seizures) receive timely and free access to emergency obstetric care as guaranteed under the NRHM. Health officials were able to give Human Rights Watch data on the number of institutional deliveries but not on the type of care received. Health experts say that for institutional deliveries to be successfully considered a proxy for safe delivery, the following conditions should be met: A skilled birth attendant should be "trained to proficiency" not only in the skills needed to manage "uncomplicated" cases, but also to identify, manage, and refer complications (WHO, ICM, FIGO Joint statement). Skilled care itself requires that an "accredited and competent" healthcare provider has at her disposal the "necessary equipment and the support of a functioning health system, including transport and referral facilities for emergency obstetric care" (WHO, ICM, FIGO Joint statement). Too often, these conditions are not being met in Uttar Pradesh and many other parts of India. |

While improving access to basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care is critical to reducing preventable maternal mortality and morbidity, so far the Indian central government and states like Uttar Pradesh have not monitored the availability and utilization of such services. In 1997 the United Nations Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) adopted a set of indicators that monitor key interventions required to reduce maternal mortality, including whether the need for emergency obstetric care has been met and the number of deaths from complications in facilities equipped with emergency obstetric care. These indicators are not being used widely in India. Recently, the Indian government rolled out the Health Management Information System (HMIS) which records whether there is access to first referral units or facilities equipped with comprehensive emergency obstetric care as an indicator, but this is being poorly implemented in Uttar Pradesh.

Maternal death investigations identifying health system shortcomings are a powerful method of monitoring the implementation and effectiveness of healthcare schemes at the district level. Studies in different parts of India have repeatedly illustrated their utility in identifying and plugging gaps in healthcare schemes, particularly in underserved areas, and the Indian government is taking steps to institutionalize such investigations. But for such a system to be implemented successfully, authorities will have to take measures to ensure that maternal deaths are reported accurately.

Human Rights Watch documented several continuing barriers to reporting maternal deaths in Uttar Pradesh, the principal of which are illustrated briefly below:

1)Low priority for the collection and use of data on the frequency and cause of maternal deaths.

This information [maternal deaths] doesn't come to us because we don't get this through the pro forma. We don't have a column for maternal deaths.

- Senior health officials, Directorate of Family Welfare, Uttar Pradesh, March 2009.

When we used to have CSSM forms [Child Survival and Safe Motherhood forms], under "Surveillance" we used to have a maternal deaths column. From last year we have given new forms-called routine immunization now- but most of the data collected in this form is also the same-about deliveries also. But the maternal deaths column in this form is missing-I think it got left out by mistake.

- Officer from Directorate of Family Welfare, Uttar Pradesh, March 2009.

2)Lack of clarity among health workers on what a maternal death is.

In this we note down the name of the person who died, date of the death, age, reasons-we note down if it is a child, but adults also sometimes we note down. If it is a pregnant woman who died then we note it down-we have to report it-any death during delivery or after delivery-within six or eight hours after delivery ... If it is after that then we write the reason-there will be other reasons-fever or something else. Those are not maternal deaths. How can those be maternal deaths?

- Ratna R., health worker, Uttar Pradesh, February 2009.

3)Poor continuity of care, essentially excluding from the records any deaths that happen during the immediate postnatal period or thereafter.

4)Jurisdictional concerns with health workers refusing to provide care or document deaths they do not see as within the purview of their care. Many health workers stated that they were instructed to provide JSY services to only those women who are married and residing in their husband's homes.

"This is Rohini's maikai's [mother's house]village. So her death will not be noted here. We do not register women when they are in their maikai's."

-Ratna R., health worker, Uttar Pradesh, February 2009.

I do not have to note down her name because I did not attend her case.... Only bahus [daughters-in-law] of our village get registered. We are told in the training that we have to motivate only the bahus [for institutional delivery].... We get money if we motivate them for sterilization-150 rupees [US$3] for every case. It does not matter where the woman is [for sterilization]. I learnt all this from the training.

- Pooja P., health worker, Uttar Pradesh, March 2009.

5) Fear of disciplinary actions against health centers and workers that report deaths.

The tracking and monitoring [of maternal deaths] is very poor. How much can you expect one lady [referring to the government-appointed birth attendant, or ANM] to do? .... There is underreporting of [maternal] deaths. My personal experience has been that some ANMs hide deaths. They are busy-out for 10 days doing polio [administering vaccine]-they do not go to all of the villages. If there is a [maternal] casualty in this period, they do not report it.

-G. S. Bajpai, district surveillance officer, Uttar Pradesh, March 2009.

6)Caste-based discrimination by health workers, which excludes many communities from care and therefore reporting.

Even when they [health workers] come they bring someone else who is a Chamar [Dalit community]. He is the one who gives polio [drops]. The nurse is Mishra [so-called upper caste] so she would not touch our children.

-Trishna T., woman who had recently delivered, Uttar Pradesh, March 2009.

7)Poor reporting by private facilities that conduct about 20 percent of all deliveries in India.

In our research, we also visited Tamil Nadu, where authorities have taken measures to improve maternal death reporting and investigations. While the Tamil Nadu system has scope for improvement, certain positive features of the Tamil Nadu approach warrant consideration for possible adoption in other parts of India:

- Awareness campaigns around maternal health.

- Encouraging death reporting from multiple sources, including family members and health workers.

- Encouraging reporting of all deaths of pregnant women irrespective of cause of death.

- Targeted training for health workers on maternal death investigations.

- Focusing on all health facilities, public and private.

- Creating a conducive environment for reporting deaths, including by explaining to health workers the purpose of such reporting.

- Assigning a clear purpose to the inquiry-identifying health system gaps that need to be rectified.

A robust civil registration system that records all births and deaths, including cause of death, is essential for effective long-term monitoring of trends in maternal mortality and enforcing laws against early and enforced marriages that directly influence maternal health. India has a civil registration system put in place by the Registration of Births and Deaths Act of 1969, that mandates recording of maternal deaths, but the system has not yet been implemented consistently. Uttar Pradesh has the worst civil registration system in the country. The latest report by the Office of the Registrar General on vital statistics for the period 1996-2005 has no information on Uttar Pradesh and indicates that no annual reports have been submitted. Since collection of vital statistics is a shared responsibility of the Indian central and state governments according to the Indian Constitution, the Indian central government has direct responsibility for the state of the civil registration system in Uttar Pradesh. For a country famed worldwide for its prowess in research, information technology, and medical sophistication, this shows not a lack of capacity but a lack of political will.

Improving Accountability: Reforming Grievance and Redress Mechanisms and Creating Emergency Response Systems

Our research also found that when women suffer preventable harms or have complaints about their treatment, they have no realistic avenue to raise their concerns and have them resolved. Too often, grievance and redress mechanisms, which should be empowering women and helping to identify gaps in maternal care, do not work. Such systems are vital not simply for holding to account those responsible for past violations but also preventing repetition of the same behavior in the future.

Problems with existing mechanisms for grievance and redress:

1)Women's lack of awareness of their entitlements under the different schemes.

2)Absence of a clear complaints procedure with a time-bound inquiry period.

3)Absence of an early or emergency response mechanism to help families that experience difficulties in seeking appropriate care.

4)Poor access to any complaints procedure, especially for poor women with little or no formal education.

5)Lack of support to pursue complaints. For example, daily wage workers are unable to make repeated appearances before human rights or other commissions to present evidence.

6)Fear of reprisals from doctors and health workers where complaints are pursued.

7)Lack of independence at the time of inquiry.

Where obstacles arise in emergencies-such as when a woman requiring urgent care is refused admission to a facility because of discrimination or because she cannot pay-there should be a mechanism for alerting authorities immediately. Bolstering early response systems will allow people who can make a difference to get the necessary information when they need it.

Even where reforms have reduced maternal death and disease, a good grievance and redress mechanism can serve to warn against possible backsliding and address other concerns of women and girls seeking maternal care, including discrimination and mistreatment.

Appropriate mechanisms for individual redress may include compensation or other appropriate action where there is individual responsibility. Individual responsibility should not be limited to frontline health workers and doctors. Any inquiry into a complaint should also examine possible failures in planning and oversight at the district and sub-district levels.

Seven Concrete Recommendations

The Indian government is already committed to a human rights approach to preventable maternal mortality and morbidity and has shown this commitment in several ways. The Indian central and state governments are poised to play a leadership role among developing countries to strengthen accountability en route to achieving the Millennium Development Goal on maternal mortality reduction. This will go a long way toward recasting India's reputation as a country with the highest number of maternal deaths in the world.

To this end, the Indian central government and Uttar Pradesh and other state governments should:

- Require that all healthcare providers, public and private, "notify" (formally report) all pregnancy-related deaths.

- Institutionalize under the NRHM a system of maternal deaths investigations. Investigations should identify systemic shortcomings and findings should be integrated into the planning and development of district and state-level plans.

- Revise the JSY monitoring indicators through a participatory and transparent process, ensuring that they track adverse pregnancy outcomes. The indicators should be in accordance with "United Nations Process Indicators" for availability and utilization of obstetric services.

- Appoint a full-time special officer to oversee the implementation of the civil registration system in Uttar Pradesh and create a special plan for implementation, including adequate funding.

- Develop, through a participatory and transparent process, a facility-based or regional system of ombudsmen to receive grievances and pursue timely redress. The mechanism should be easily accessible to women with little or no formal education.

- Develop early response systems, including a telephone hotline for health-related emergencies which women facing obstetric emergencies could use.

Donor countries and international agencies should provide technical and financial assistance to promote notification and investigation of maternal deaths. They should also provide technical and financial assistance to ensure that all government health interventions, particularly interventions funded by them, are monitored and evaluated in accordance with UN process indicators.

Methodology

This report is based on Human Rights Watch field investigations and consultations with key stakeholders in India between November 2008 and August 2009. Where available, the accounts gathered through our field investigations have been corroborated by data from government surveys, and reports or studies by nongovernmental organizations, international agencies, and public health experts in India.

Based on our preliminary consultations with 55 public health specialists, lawyers, and representatives from local nongovernmental organizations working on the right to health and women's rights across India, Human Rights Watch chose to focus on Uttar Pradesh state in north India.

Uttar Pradesh was chosen as a case study because, being the most populous state, it accounts for the highest number of maternal deaths in India.[3] It is also one of several states that had issued a 2004 governmental order seeking investigations into maternal deaths.

Human Rights Watch also examined southern Tamil Nadu's relatively stronger system of investigating maternal deaths.

The primary field investigations took place in Rae Bareilly, Unnao, Chitrakoot, Lucknow, and Barabanki districts of Uttar Pradesh in February, March, and June 2009; New Delhi in March 2009; and in Tamil Nadu in April 2009. We supplemented these field investigations with telephone interviews between June and August 2009.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 191 people; 95 in individual interviews and the remainder in group interviews. These included:

In Uttar Pradesh:

- Fifty-six women and men from villages, including individuals from nine families in which maternal deaths had occurred.

- Thirty-four health staff from government health facilities, peripheral field-based health workers including auxiliary nurse-midwives (ANMs), accredited social health activists (ASHAs) or female community health aides, anganwadi workers (female workers tasked with providing early childhood care and education and nutritional supplements for pregnant women), and traditional birth attendants.

- Forty-five officials including heads of village level councils, panchayat mitras (literally, friends of the village council), chief medical officers (highest health authority at the district level), officials from the directorates of family welfare and medical and health services, and members of the district and state project management units of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), India's flagship rural healthcare program.

- Seven doctors from the private sector, including representatives from the Uttar Pradesh chapters of the Federation of Obstetric and Gynecological Societies of India and the Indian Medical Association.

- Thirty journalists and representatives from nongovernmental and intergovernmental organizations including Vatsalya, Mamta, SAHAYOG, Healthwatch Forum, Jan Swasthya Abhiyaan-UP chapter, CARE-India, the John Hopkins University project on infant and maternal health, Vanangana, PATH, and UNICEF.

In NewDelhi:

- Eleven officials including officials from the Office of the Registrar General of India, the NRHM directorate, and representatives from the National Health Systems Resource Center, a technical resource center set up under the NRHM.

In Tamil Nadu:

- Four former and four present government officials overseeing maternal mortality reviews.

- Nine activists, including grassroots-level workers and a professor who participates in the maternal mortality review meetings.

Human Rights Watch had hoped to include the perspectives of doctors or health workers who were suspended, dismissed, or arrested following complaints about maternal health care in Uttar Pradesh. Unfortunately, we were able to trace only one such health worker, a hospital staff nurse.

Health workers and nongovernmental organizations providing services to villagers assisted Human Rights Watch in identifying pregnant women and families to interview; we further developed contacts and interview lists through references from interviewees.

Interviews lasted between 20 minutes and three hours and were conducted in English, Hindi, dialects of Hindi such as Awadhi or Bundelkhandi, or Tamil depending on the interviewee's preference. The primary investigator from Human Rights Watch is also fluent in spoken Hindi and Tamil. In cases where the interviewees chose to communicate in Awadhi or Bundelkhandi, the interviews were conducted with the assistance of female interpreters.

All interviews during field investigations in Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and New Delhi were conducted after orally obtaining informed consent. Human Rights Watch has respected the choices of all interviewees to be identified, not identified, or have their experiences and views left out of the report entirely, and has assigned pseudonyms or withheld identifiable information accordingly. Pseudonyms have been assigned randomly, and do not correspond to the religion, caste, or tribe of the interviewee.

We supplemented our field investigations with official data provided by the Indian central and Uttar Pradesh state governments in response to several applications filed by Human Rights Watch under the Right to Information Act, 2005.[4]

Human Rights Watch also convened an India advisory group whose purpose was to provide inputs and feedback on methodology, support in reaching out to relevant networks and groups, and review this report.[5]

Scope and Limitations

This report uses a human rights framework to examine maternal health care, setting out several specific steps we believe officials should take to better integrate accountability into maternal healthcare programs and ensure their implementation through the health system. It does not explore all available tools for accountability including external surveys assessing quality of health care, public hearings, social audits of budgets, or community-based monitoring. The NRHM, India's flagship rural healthcare program, sets out a three-pronged accountability framework of external surveys, community-based monitoring, and stringent internal monitoring. This report's focus is on the last of these three prongs, the state's internal monitoring of policies, practices, and performance. While the arguments presented in this report address the specific issue of preventable maternal mortality and morbidity, accountability as a human rights principle is central to the right to the highest obtainable standard of health more generally.

Uttar Pradesh state is one of eight Empowered Action Group (EAG) states with poor socio-economic indicators.[6]The maternal health parameters of the eight states are comparable, and activists and public health experts in India say they exhibit similar recurring health system shortcomings.[7] The concerns raised in this report in chapters III-V have been examined in the context of Uttar Pradesh, but apply to many states, particularly those in the Empowered Action Group. Financial barriers to care are a problem in many states in India including non-Empowered Action Group states.

While interviewing bereaved families, Human Rights Watch's researchers gathered information on the fulfillment of government standards for maternal health care. Detailed identification and analysis of all the socio-economic or medical causes that contributed to each of these maternal deaths is beyond the scope of this report.

Note on Estimates

All data used in this report are estimates. The indicator most often cited in this report is the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) which is an estimate of the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. The Indian government has released maternal mortality estimates based on various measures including MMR. Maternal mortality data for Indian states and for the country as a whole going back to 1997 have been provided by the Indian government in two recent reports. Data for the period 1997-2003 was released in 2006 in a publicly issued special report on maternal mortality and its causes.[8] A second data set, released in mid-2009, provides preliminary information for the period 2004-2006, pending release of the full report.[9] The in-country estimates used in this report are drawn from the interim 2004-2006 data. Information about medical causes of maternal deaths is drawn from the 1997-2003 data.

International data presented in this report are drawn from the latest available international estimates of maternal mortality that date from 2005.[10] The Maternal Mortality Working Group (MMWG) comprised of the WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, the UN Population Division, and the World Bank, as well as several outside technical experts, developed a methodology to create comparable country, regional, and global estimates of maternal mortality. The MMWG concluded that the data provided by the Indian government's survey is uncertain, containing biases such as ill-defined cause-of-death codes. This group calculated that the Indian survey underestimates the national MMR by 50 percent.

The national MMR figures used in this report should be interpreted with the caveat that they do not fully reflect the changes brought on by the Indian government's flagship healthcare program, the NRHM, which has only been in effect since mid-2005 when the figures were compiled for the period 2004-2006. Furthermore, these figures represent point estimates within a larger range.[11] While the point estimates taken alone suggest a discernible reduction in MMR, the overlap in its ranges makes it difficult to gauge the extent of maternal mortality reduction in many states, particularly the EAG states.[12]

Note on Terminology

"Health workers": We use this phrase to refer to three categories of field-based peripheral workers-ANMs, anganwadi workers, and ASHAs.

"Investigating maternal deaths": We use this phrase to refer to procedures that identify health system shortcomings in addressing the causes, socio-economic as well as medical, of maternal deaths.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has outlined several methods of conducting maternal death reviews including community-based (verbal autopsies) and facility-based reviews, and confidential inquiries.[13] Human Rights Watch does not have the expertise to recommend a particular method of investigating deaths. Confidential inquiries have the merit of covering deaths irrespective of the place of occurrence and of not limiting the inquiry to identifying personal, family, or community factors as is the case with verbal autopsies.

"Lower castes": The phrase "lower castes" has been used to describe two types of castes in India, scheduled castes and so-called "other backward classes." Under Indian law scheduled caste refers to Dalits or so-called "untouchables" who are traditionally considered "outcastes," beneath the lowest caste in the four-caste hierarchy. Indian law uses "other backward classes" to refer to the lowest caste within the four-caste hierarchy, the Shudras. Both groups continue to face historical discrimination and have high rates of poverty.

I. Preventable Maternal Mortality and Morbidity: A Global Public Health Emergency

[Maternal mortality is] a measure of mortality that can be dramatically, rapidly, and consistently decreased-almost to the point of negligibility-if the appropriate actions are taken.

- United Nations Millennium Project Task Force on Child Health and Maternal Health, 2005.

Pregnancy is not a disease or illness. Yet more than half a million women and girls die every year because of pregnancy, childbirth, and unsafe abortions.[14] Health experts determine that about 75 percent of these maternal deaths are preventable. Year after year women die preventable deaths merely because they do not have access to appropriate health interventions.[15]

Pregnancy and childbirth also leave millions of women and girls with short- or long-term injuries, infections, or disabilities (maternal morbidities). For every maternal death there are about 20-30 cases of maternal morbidity.[16]Between 50,000 and 100,000 new incidents of obstetric fistulae (tissue damage between the vagina and the bladder or rectum leading to incontinence) are detected annually.[17] Other long-term morbidities include uterine prolapse (weakened muscles after childbirth leading to displacement of uterus), infertility, and depression; short-term complications include hemorrhage, convulsions, cervical tears, shock, and fever.[18]

This has implications not only for women's reproductive health overall. Differences in levels of preventable maternal mortality and morbidity are strong indicators of other disparities, in particular the unequal access to quality health care, both between women in developed and developing countries and among women in the same country. Nearly 99 percent of all maternal deaths and morbidities occur in developing countries, particularly sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.[19] The difference between Ireland and Sierra Leone illustrates this disparity: in Ireland 1 death occurs per 100,000 live births compared with Sierra Leone's 5,400 deaths. In Niger, one in every eight 15-year-old girls is expected to eventually die of a maternal cause. In contrast, 1 in 47,600 15-year-olds will die in Ireland.

Causes and the Three Delays

Globally, approximately 80 percent of all maternal deaths are estimated to be caused by direct obstetric causes including hemorrhage, sepsis (severe infection spreading through the bloodstream), eclampsia (pregnancy complication characterized by seizures or coma), unsafe abortions, and prolonged or obstructed labor.[20] Other indirect causes include malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS.[21] In countries with high rates of HIV, malaria, or tuberculosis, the proportion of deaths due to such causes may be higher.[22]

Medical causes explain just part of the story. Typically, a maternal death marks the tragic ending of an already complex story with different elements-socio-economic, cultural, and medical-operating at different levels-individual, household, community, and health system-related. Factors contributing to maternal death include early marriage, women's poor control over access to and use of contraceptives of their choice, husbands or mothers-in-law dictating women's care-seeking behavior, overall poor health including poor nutrition, poverty, lack of health education and awareness, domestic violence, and poor access to affordable quality health care, including basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric services.[23]

Health experts typically analyze these myriad circumstances using the "three delays model." In this model the reasons for delay in seeking and utilizing appropriate health care are broken down into three segments-the first being the delay in seeking professional health care, followed by the delay in reaching the appropriate health facility, and lastly, the delay in receiving care.

Some healthcare providers tend to unjustifiably lay all the blame for delay on pregnant women and their families for their uneducated or unresponsive behavior. But the delay in people's decisions to seek care is often due to their perceptions of systemic shortcomings and mistrust in health facilities.[24] Many women and activists from Uttar Pradesh told Human Rights Watch that they did not like going to government healthcare facilities because they are shut, doctors are not present, medicines are not available, or they are too far away.[25] Where a woman's own experiences discourage her from going to a healthcare facility, it is unlikely that information and education programs about facilities or schemes will sustain her motivation to seek care. More nuanced health interventions such as measures to improve the trust in the health system should be taken, for instance, by improving quality of care and creating easily accessible and effective grievance redressal mechanisms.

Reduction Strategies

There is broad global consensus on three critical maternal-mortality-reducing strategies-skilled attendance at birth, access to emergency obstetric care, and access to referral systems. While these three strategies are necessary, they are not sufficient to achieve a 75 percent reduction in maternal mortality.[26]

Available research suggests that access and ability to utilize emergency obstetric care will have maximum impact on maternal mortality. Basic emergency obstetric care includes the ability to conduct assisted vaginal deliveries, remove placenta and retained products, and manage pregnancy complications by intravenously introducing or injecting anticonvulsants, oxytocic drugs (drugs that expand the cervix or vagina to facilitate delivery), and antibiotics.[27] Comprehensive emergency obstetric care includes the ability to provide life-saving interventions including through surgery (cesarean sections) and blood transfusions.[28] Quality basic and emergency obstetric care are dependent on factors such as availability of adequate health personnel trained in midwifery skills, specialists such as anesthetists, gynecologists, and surgeons, adequate infrastructure such as blood banks, blood matching ability, sufficient supply of drugs, and good referral systems.

Skilled birth attendance refers to the presence of health staff trained in midwifery at birth. A skilled birth attendant's ability to save a pregnant woman is limited unless she is supported by a robust health system that includes emergency obstetric care and referral support. Some experts argue that "the skill level of the attendant needed at the peripheral level [sub-district including village level]...depends upon the ready accessibility and acceptance of referral care."[29]

The most skilled attendant cannot save a woman experiencing life-threatening pregnancy-related complications unless she is able to reach the appropriate health facility in time. A strong referral system is not limited to ambulance services. It must at a minimum provide obstetric first aid in case of emergencies and have easily accessible and affordable around-the-clock health care and referral facilities that connect both private and public health facilities.[30]

For all three core interventions to successfully reduce and eliminate preventable maternal mortality and morbidity there has to be a functional public health system. Hence the global priority that is being given to maternal mortality reduction is increasingly hailed as an opportunity to improve public health systems.[31]

International Commitments and Progress on Maternal Mortality Reduction

International and national efforts to reduce maternal mortality span several decades. Concerted global efforts have been made in the last two decades including the 1987 Safe Motherhood Initiative and the 1994 International Convention on Population and Development, which reaffirmed governments' commitment to the issue.[32] And through the Millennium Declaration, 189 countries pledged to achieve eight development goals by 2015, including a 75 percent maternal mortality reduction compared to its 1990 levels.[33] In 2009, in a special session of the Human Rights Council, governments committed to adopting a human rights approach to preventable maternal mortality and morbidity.

But few governments are making adequate progress to achieve a 75 percent reduction in maternal mortality by 2015.[34]There has been less progress in meeting the maternal mortality reduction goal than in meeting any of the other seven MDGs.[35] Even progress in measuring maternal mortality is lacking: a recent international study of 68 countries states that "[t]rends in maternal mortality that would indicate progress towards MDG 5 [maternal mortality reduction] were not available."[36] The authors noted that maternal mortality was high or very high in 56 of the 68 countries. Further, high rates of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis have actually resulted in an increase in maternal mortality in several countries.[37]

II. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity in India

Estimates and Causes

For an emerging global economic power reputed for its medical prowess, India continues to have unacceptably high maternal mortality levels. In 2005, the last year for which international data is available, India's maternal mortality ratios were 16 times that of Russia, 10 times that of China, and 4 times higher than in Brazil.[38] Of every 70 Indian girls who reach reproductive age, one will eventually die because of pregnancy, childbirth, or unsafe abortion, higher than 120 other countries including India's neighbors such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and China. More will suffer preventable injuries, infections, and disabilities, often serious and lasting a lifetime, due to failures in maternal care.

While country data on maternal mortality is poor, there is far less government data on maternal morbidity (injuries, infections, and disabilities associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and unsafe abortions). There is some state-wide data on obstetric fistula and infertility. For instance, the District level Facility and Household Survey (DLHS) shows that nearly 1.6 percent of married women in Uttar Pradesh reported obstetric fistula, and 10 percent experienced primary or secondary infertility.[39] The latest nation-wide government-funded survey, the National Family and Health Survey (NFHS), shows that rural women experience many health problems during pregnancy including difficulty with vision during daytime, night blindness, convulsions not from fever, swelling of the legs, body, and face, excessive fatigue, and vaginal bleeding.[40]

National averages camouflage in-country variations in maternal mortality and morbidity, which indicate poor health equity and a lack of equality in access to and utilization of maternal health care. The northern belt in India, comprising the eight Empowered Action Group (EAG) states and Assam, has the highest maternal mortality rates nationally.[41] At 440 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, Uttar Pradesh reports the second highest maternal mortality in the country, about 1.7 times the estimated national MMR and more than three times that of states like Tamil Nadu in south India.[42]

There are disparities in utilization of maternal health care even within states, districts, and cities. Rural women, the urban poor, and women in geographically remote areas report poorer utilization of maternal healthcare services than those in urban areas.[43] The incidence of morbidity is significantly higher in rural than in urban areas, with rates often two or three times as high.[44] Pregnant women belonging to marginalized communities such as Dalits (so-called untouchables), other backward classes (the so-called lowest caste just above Dalits in the hierarchy), and tribal communities utilize maternal health services far less than women belonging to the uppercastes.[45]A 2007 UNICEF study in six northern states showed that 61 percent of the women who died during pregnancy and childbirth belonged to Dalit or tribal communities.[46]

Roughly 65 percent of all maternal deaths are caused by direct obstetric causes. Hemorrhage is the main cause of death in India, followed by sepsis, and unsafe abortions.[47] At 35 percent, the proportion of maternal deaths due to indirect causes such as tuberculosis, viral hepatitis, malaria, and anemia is also much higher in India than the estimated global average of 20 percent.[48] Poor overall health and nutrition, poor education, women's lack of decision-making power within families, domestic violence, and son-preference coupled with women's poor autonomy in using contraceptives of their choice adversely influence their maternal health.[49]

Maternal mortality remains high in many parts of India despite decades-long initiatives aimed at reducing it.[50] Acknowledging that the number of maternal deaths is "unacceptably high,"[51] the Indian central government itself has identified maternal mortality reduction as a national priority,[52] aiming to bring the MMR below 100 by 2012.[53] The Indian Planning Commission has stated that it will be difficult for India to meet this goal at the present rates at which maternal mortality is declining.[54] Latest all-India estimates show a small decline in maternal mortality from 301 to 254 between 2003 and 2006.[55]

Delivery of Basic and Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric Services

The tiered public health system (see Table 1 on next page) coupled with the services of field-based female health workers including auxiliary nurse-midwives (ANMs) forms the backbone for delivering free basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care to the rural poor. Norms for providing maternal health care at each of these tiers were recently revised through the Indian government's flagship seven-year rural healthcare program, the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), read in conjunction with the 2006 Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS).[56]

Table 1: Tiered Public Health System in India[57]

Health facility |

Level |

Population Norm |

|

Health sub-center (HSC) |

Primary |

Plains: One for every 5,000 Hilly or tribal areas: One for every 3,000 |

|

Primary health center (PHC) |

Primary |

Plains: One for every 30,000 |

Community health center (CHC) |

Secondary |

Plains: One for every 1,20,000 |

|

First Referral Unit (FRU) |

Secondary |

One in every 300,000-500,000 (Community health centers are also being upgraded as first referral units) |

District hospital |

Tertiary |

One for every 2-3 million (In some areas district hospitals function as the first referral unit) |

Medical college hospital |

Tertiary |

One for every 5-8 million |

Introduced in mid-2005, the NRHM seeks to "improve access to rural people, especially poor women and children to equitable, affordable, accountable and effective primary health care" with a special focus on maternal mortality reduction.[58] Seeking to achieve goals set under the 2000 National Health Policy and the Millennium Development Goals, it aims to reduce maternal mortality ratios to below-100 levels by 2012,[59] and commits to "report publicly on progress."[60]

The NRHM subsumed the former Reproductive and Child Health Program (RCH-II) program,[61] developing new strategies for maternal mortality reduction. Amongst other things, it seeks to upgrade primary health centers into around-the-clock facilities for basic emergency obstetric care and emergency obstetric first aid.[62] In remote areas where primary healthcare centers are unavailable, the state can accredit sub-centers to conduct normal deliveries. Where sub-centers are also unavailable, the state can accredit private health facilities to provide such care.[63] The NRHM also requires states to upgrade community health centers as "first referral units" equipped to provide comprehensive emergency obstetric care.[64]

The NRHM provides "concrete service guarantees" for many health needs (see Table 2 on next page). These include health education, skilled attendance at all births, free antenatal care, postnatal care, and in-patient facility-based care for delivery and other maternal health conditions at primary and secondary sub-district and district public health facilities, for women below the poverty line.[65] Private healthcare facilities, which are poorly regulated, conduct about 20 percent of the deliveries and also play a significant role in providing abortion services, but these are not governed by the NRHM service guarantees or the IPHS.[66]

Table 2: Service Guarantees under the NRHM

Health sub-center (HSC) |

Primary health center (PHC) |

Community health center (CHC) |

|

Antenatal care ·An ANM with the help of an ASHA should conduct three antenatal check-ups and a fourth visit around 36 weeks. ·Each antenatal check includes examination of weight, blood pressure, anemia, abdominal examination, height and breast examination, minimum laboratory investigations including hemoglobin, urine albumin, and sugar. ·The health staff should identify and promptly refer high-risk pregnancies to the appropriate health facility. Intranatal care ·Sub-centers in remote areas to conduct normal deliveries. ·They should promptly refer cases to an appropriate health facility. Postnatal care ·ANMs with the assistance of ASHAs should conduct a minimum of two home visits (irrespective of place of delivery), the first within 48 hours of delivery and the second within seven or ten days of delivery. |

All norms for antenatal and postnatal care in sub-centers apply to PHCs. They should provide the following services: ·Free out-patient services. · 24-hour delivery services for normal and assisted deliveries (vacuum and forceps delivery) and manual removal of placenta. ·Safe abortions. ·24-hour emergency pre-referral first aid, management of pregnancy induced hypertension. ·Prompt referral of complicated cases to the appropriate health facility. ·All referral services guaranteed free. |

CHCs should provide the following facilities: ·All facilities present in PHCs. ·Surgical and other medical interventions including cesarean sections and safe abortions. ·Blood storage. ·Referral services including transport. |

The NRHM is applicable to all states, but 18 focus states, including Uttar Pradesh, receive additional funding for the stated goal of regional equity.[67]

The Janani Suraksha Yojana

Reforms introduced through the NRHM are coupled with the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY, literally, Mother Protection Scheme)-an NRHM scheme replacing the earlier National Maternity Benefit Scheme-that promotes facility-based deliveries through cash incentives for pregnant women and ASHAs.[68] The Indian government promotes facility-based deliveries with the stated objective of improving access to skilled birth attendants for pregnant women, especially those below the poverty line and members of Dalit and tribal communities.[69] Women who deliver in health facilities are given greater cash assistance than women who deliver in their homes. Theoretically, the scheme integrates cash assistance with delivery and post delivery care.[70]

The success of the JSY depends on the ASHAs-rural women appointed as community health aides who are given many tasks including tracking pregnancies, assisting with polio drives, and sharing information about family planning. Under the JSY, ASHAs are tasked with developing a micro birth plan to track the progress of every pregnancy within her area of work.[71] They should identify and register all pregnant women and provide services described as the "four Is." These include "informing" dates for antenatal check-ups, "identifying" a health center for referral, "identifying" the place of delivery, and "informing" pregnant women the expected date of delivery.[72]

ASHAs should facilitate both antenatal and postnatal care, assisting women in getting at least three antenatal check-ups during their pregnancy, and visiting them "within seven or ten days of delivery." During the postnatal care visit, they are responsible for facilitating further access to medical assistance if needed. ASHAs are primarily responsible for arranging transport and escorting the pregnant woman to a pre-identified health facility for delivery.

The cost of the scheme is entirely covered by the Indian central government. The government gives women who choose to deliver in government health facilities or accredited private health facilities 1,400 rupees (US$28) in rural areas.[73] In focus states, such as Uttar Pradesh, the cash assistance to women delivering in public health facilities is not limited by age or number of children.[74] Women who choose to deliver in their homes are given 500 rupees (US$10). But such cash assistance for home deliveries is limited to women above age 18 and with up to two live children.

Critiques of the Government's Approach to Maternal Health

NRHM has resulted in greater attention to maternal health but many government officials and civil society groups have concerns about the government's approach. They argue that poor accountability adversely affects not only planning based on women's health needs but also the implementation of existing maternal healthcare interventions. These gaps in accountability manifest themselves in many ways, notably recurrent health system or programmatic gaps and a lack of government action to ensure that health programs are actually reaching pregnant women from marginalized communities including the poor, Dalit, other backward classes, religious minorities and tribal communities, or women in geographically remote areas. Furthermore, activists say that poor monitoring and attention to the supply-side coupled with the spurt in demand for institutional deliveries has resulted in substandard maternal health care at these facilities.[75]

Moreover, state governments' pattern of unspent NRHM funds buttresses calls for better accountability by activists and doctors.For instance, millions of dollars in government funds for health care in Uttar Pradesh go unspent each year. A study for the Indian Planning Commission shows that roughly 40, 40, and 30 percent of the amount allocated under the NRHM to the Uttar Pradesh government went unspent in fiscal years 2005-06, 2006-07, 2007-08[76]. In February-March 2009, activists in Uttar Pradesh claimed that nearly "700 crore rupees [US$140 million]" remained unspent even though it was almost the end of fiscal year 2008-2009.[77]In a January 2009 letter to 71 district chief medical officers, the Uttar Pradesh NRHM Mission Director urged each of them to spend "30 lakh rupees [US$60,000]" within two months, that is, by the end of March 2009.[78]

Health experts and activists have also expressed concerns about the effectiveness of existing government strategies to improve maternal health. While the JSY has improved access to health care during deliveries, many groups argued that the Indian central and state governments are not taking adequate measures to address unsafe abortions-a significant cause of maternal mortality in India. Even though the NRHM guarantees safe abortion services in public health facilities, and abortions are allowed in accordance with the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, in practice, little is being done to promote awareness and access to these services. Furthermore, health care to address maternal morbidities, which affect thousands more women leaving many disabled for life, is not given the attention it requires. What was intended to be a cash assistance integrated with antenatal and postnatal care, in practice, operates as a cash incentive to increase women's demand for facility-based deliveries without information on birth preparedness.[79]

Women's rights and public health experts caution that the government's interventions to improve maternal health are too vertical, ignoring concerns about the overall health of women during their life-cycle, including the underlying determinants of girls' and women's health and their other rights including food, potable water, employment, and access to contraceptives of their choice.[80] The underlying determinants of health influence maternal health care. Dr. Sundari Ravindran, a leading public health expert on the reproductive and sexual health of women, said that in many areas of India, women are likely to experience a far higher rate of pregnancy-related complications requiring emergency obstetric care than the global average of 15 percent.[81] This is because of their overall poor health resulting from poor nutrition and anemia and has implications for the number of facilities that need to be equipped with comprehensive emergency obstetric facilities.

Further, activists repeatedly emphasize that vertically run programs, notably polio eradication, have had negative outcomes, which should not be replicated in maternal healthcare programming.[82] One of the main adverse outcomes of the polio eradication campaign is that field-based health workers spend a large part of their time on it, forcing other health concerns into the backseat. For instance, senior officials from the Uttar Pradesh Directorate of Family Welfare concede that "[p]ulse polio-all focus is on this project and other programs are neglected."[83] A study commissioned by the Uttar Pradesh Health Systems Development Project quotes a USAID study in Uttar Pradesh saying that one of the many challenges to maternal health care is that "National programmes such as Polio eradication [are] consuming half of health functionaries time."[84]

Moreover, many feel that the government mistakenly continues to approach the reproductive and sexual health of women within an overarching framework of "population control or stabilization." The government has not taken measures empowering women to make informed, autonomous, health-related decisions, especially about use of contraceptives or facilitated use of contraceptives that encourage male participation.[85] They point to the government's sterilization program, noting that field-based health workers spend a considerable amount of their time on sterilization without providing information about non-terminal contraceptive methods.[86]

Several women and men from rural Uttar Pradesh reported seeing ASHAs or nurse-midwives only during polio drives or complained that they received prompt assistance only when they wanted to get themselves sterilized.[87] For instance, Vimala V. died after delivering at home and Revati R., a relative who was present at the time of delivery, said she had died without assistance from any health worker. Revati R. explained: "If you tell her [health worker] that it is for sterilization, then they will go to any length to help you-will arrange their own vehicle and take you to the hospital. But if you say that it is for something else, they will not even turn around and look at you."[88]

The "population control" approach has found its way into the JSY as well. In the non-Empowered Action Group states, JSY benefits are restricted to women above age 19 for up to two live births.[89] Likewise, cash assistance for home-based deliveries is restricted to women above age 19 and up to two live births. This shortchanges the medical needs of young mothers and pregnant women with multiple pregnancies.

Finally, the private sector continues to play a significant role in providing healthcare services, including obstetric services. About 64 percent of women go to private healthcare providers for complete antenatal care and about 20 percent of all deliveries occur in private health facilities.[90] Many activists said that the absence of regulation of the private sector posed a significant challenge to ensuring affordable quality maternal health care to all women.[91]

The Importance of Accountability