Summary

George Tenet asked if he had permission to use enhanced interrogation techniques, including waterboarding, on Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.…

“Damn right,” I said.

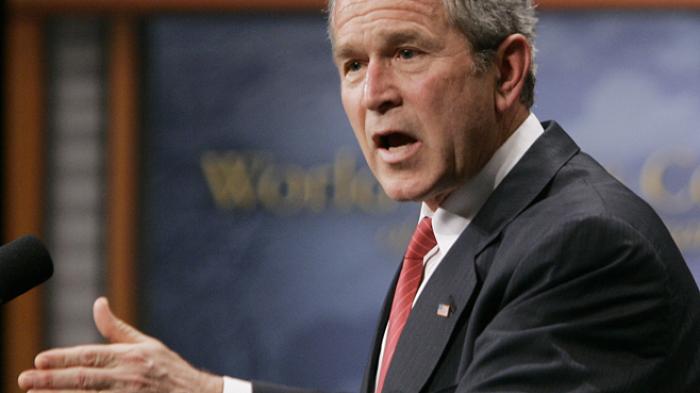

—Former President George W. Bush, 2010[1]

There is no longer any doubt as to whether the current administration has committed war crimes. The only question that remains to be answered is whether those who ordered the use of torture will be held to account.

—Maj. Gen. Antonio Taguba, June 2008[2]

Should former US President George W. Bush be investigated for authorizing “waterboarding” and other abuses against detainees that the United States and scores of other countries have long recognized as torture? Should high-ranking US officials who authorized enforced disappearances of detainees and the transfer of others to countries where they were likely to be tortured be held accountable for their actions?

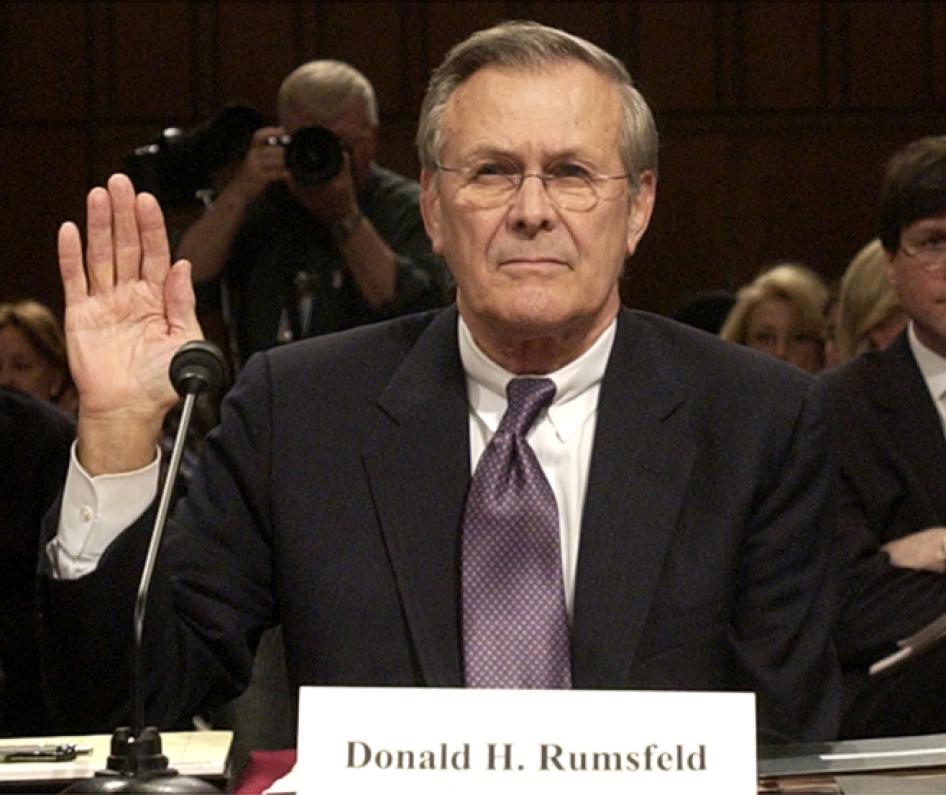

In 2005, Human Rights Watch’s Getting Away with Torture? presented substantial evidence warranting criminal investigations of then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Director George Tenet, as well as Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, formerly the top US commander in Iraq, and Gen. Geoffrey Miller, former commander of the US military detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

This report builds on our prior work by summarizing information that has since been made public about the role played by US government officials most responsible for setting interrogation and detention policies following the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States, and analyzes them under US and international law. Based on this evidence, Human Rights Watch believes there is sufficient basis for the US government to order a broad criminal investigation into alleged crimes committed in connection with the torture and ill-treatment of detainees, the CIA secret detention program, and the rendition of detainees to torture. Such an investigation would necessarily focus on alleged criminal conduct by the following four senior officials—former President George W. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and CIA Director George Tenet.

Such an investigation should also include examination of the roles played by National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice and Attorney General John Ashcroft, as well as the lawyers who crafted the legal “justifications” for torture, including Alberto Gonzales (counsel to the president and later attorney general), Jay Bybee (head of the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel (OLC)), John Rizzo (acting CIA general counsel), David Addington (counsel to the vice president), William J. Haynes II (Department of Defense general counsel), and John Yoo (deputy assistant attorney general in the OLC).

Much important information remains secret. For example, many internal government documents on detention and interrogation policies and practices are still classified, and unavailable to the public. According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which has secured the release of thousands of documents under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), among the dozens of key documents still withheld are the presidential directive of September 2001 authorizing CIA "black sites"—or secret prisons—as well as CIA inspector general records.[3] Moreover, many documents that have ostensibly been released, including the CIA inspector general’s report and Department of Justice and Senate committee reports, contain heavily redacted sections that obscure key events and decisions.

Human Rights Watch believes that many of these documents may contain incriminating information, strengthening the cases for criminal investigation detailed in this report. It also believes there is enough strong evidence from the information made public over the past five years to not only suggest these officials authorized and oversaw widespread and serious violations of US and international law, but that they failed to act to stop mistreatment, or punish those responsible after they became aware of serious abuses. Moreover, while Bush administration officials have claimed that detention and interrogation operations were only authorized after extensive discussion and legal review by Department of Justice attorneys, there is now substantial evidence that civilian leaders requested that politically appointed government lawyers create legal justifications to support abusive interrogation techniques, in the face of opposition from career legal officers.

Thorough, impartial, and genuinely independent investigation is needed into the programs of illegal detention, coerced interrogation, and rendition to torture—and the role of top government officials. Those who authorized, ordered, and oversaw torture and other serious violations of international law, as well as those implicated as a matter of command responsibility, should be investigated and prosecuted if evidence warrants.

Taking such action and addressing the issues raised in this report is crucial to the US’s global standing, and needs to be undertaken if the United States hopes to wipe away the stain of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo and reaffirm the primacy of the rule of law.

Human Rights Watch expresses no opinion about the ultimate guilt or innocence of any officials under US law, nor does it purport to offer a comprehensive account of the possible culpability of these officials or a legal brief. Rather it presents two main sections: one providing a narrative summarizing Bush administration policies and practices on detention and interrogation, and another detailing the case for individual criminal responsibility of several key administration officials.

The road to the violations detailed here began within days of the September 11, 2001 attacks by al Qaeda on New York and Washington, DC, when the Bush administration began crafting a new set of policies, procedures, and practices for detainees captured in military and counterterrorism operations outside the United States. Many of these violated the laws of war, international human rights law, and US federal criminal law. Moreover, the coercive methods that senior US officials approved include tactics that the US has repeatedly condemned as torture or ill-treatment when practiced by others.

For example, the Bush administration authorized coercive interrogation practices by the CIA and the military that amounted to torture, and instituted an illegal secret CIA detention program in which detainees were held in undisclosed locations without notifying their families, allowing access to the International Committee of the Red Cross, or providing for oversight of their treatment. Detainees were also unlawfully rendered (transferred) to countries such as Syria, Egypt, and Jordan, where they were likely to be tortured. Indeed, many were, including Canadian national Maher Arar who described repeated beatings with cables and electrical cords during the 10 months he was held in Syria, where the US sent him in 2002. Evidence suggests that torture in such cases was not a regrettable consequence of rendition; it may have been the purpose.

At the same time, politically appointed administration lawyers drafted legal memoranda that sought to provide legal cover for administration policies on detention and interrogation.

As a direct result of Bush administration decisions, detainees in US custody were beaten, thrown into walls, forced into small boxes, and waterboarded—subjected to mock executions in which they endured the sensation of drowning. Two alleged senior al Qaeda prisoners, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Abu Zubaydah, were waterboarded 183 and 83 times respectively.

Detainees in US-run facilities in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Guantanamo Bay endured prolonged mistreatment, sometimes for weeks and even months. This included painful “stress” positions; prolonged nudity; sleep, food, and water deprivation; exposure to extreme cold or heat; and total darkness with loud music blaring for weeks at a time. Other abuses in Iraq included beatings, near suffocation, sexual abuse, and mock executions. At Guantanamo Bay, some detainees were forced to sit in their own excrement, and some were sexually humiliated by female interrogators. In Afghanistan, prisoners were chained to walls and shackled in a manner that made it impossible to lie down or sleep, with restraints that caused their hands and wrists to swell up or bruise.

These abuses across several continents did not result from the acts of individual soldiers or intelligence agents who broke the rules: they resulted from decisions of senior US leaders to bend, ignore, or cast rules aside. Furthermore, as explained in this report, it is now known that Bush administration officials developed and expanded their initial decisions and authorizations on detainee operations even in the face of internal and external dissent, including warnings that many of their actions violated international and domestic law. And when illegal interrogation techniques on detainees spread broadly beyond what had been explicitly authorized, these officials turned a blind eye, making no effort to stop the practices.

The Price of Impunity

The US government’s disregard for human rights in fighting terrorism in the years following the September 11, 2001 attacks diminished the US’ moral standing, set a negative example for other governments, and undermined US government efforts to reduce anti-American militancy around the world.

In particular, the CIA’s use of torture, enforced disappearance, and secret prisons was illegal, immoral, and counterproductive. These practices tainted the US government’s reputation and standing in combating terrorism, negatively affected foreign intelligence cooperation, and sparked anger and resentment among Muslim communities, whose assistance is crucial to uncovering and preventing future global terrorist threats.

President Barack Obama took important steps toward setting a new course when he abolished secret CIA prisons and banned the use of torture upon taking office in January 2009. But other measures have yet to be taken, such as ending the practice of indefinite detention without trial, closing the military detention facility at Guantanamo Bay and ending rendition of detainees to countries that practice torture. Most crucially, the US commitment to human rights in combating terrorism will remain suspect unless and until the current administration confronts the past. Only by fully and forthrightly dealing with those responsible for systematic violations of human rights after September 11 will the US government be seen to have surmounted them.

Without real accountability for these crimes, those who commit abuses in the name of counterterrorism will point to the US mistreatment of detainees to deflect criticism of their own conduct. Indeed, when a government as dominant and influential as that of the United States openly defies laws prohibiting torture, a bedrock principle of human rights, it virtually invites others to do the same. The US government’s much-needed credibility as a proponent of human rights was damaged by the torture revelations and continues to be damaged by the complete impunity for the policymakers implicated in criminal offenses.

As in countries that have previously come to grips with torture and other serious crimes by national leaders, there are countervailing political pressures within the United States. Commentators assert that any effort to address past abuses would be politically divisive, and might hinder the Obama administration’s ability to achieve pressing policy objectives.

This position ignores the high cost of inaction. Any failure to carry out an investigation into torture will be understood globally as purposeful toleration of illegal activity, and as a way to leave the door open to future abuses.[4] The US cannot convincingly claim to have rejected these egregious human rights violations until they are treated as crimes rather than as “policy options.”

In contrast, the benefits of conducting a credible and impartial criminal investigation are numerous. For example, the US government would send the clearest possible signal that it is committed to repudiating the use of torture. Accountability would boost US moral authority on human rights in counterterrorism in a more concrete and persuasive way than any initiative to date; set a compelling example for governments that the US has criticized for committing human rights abuses and for the populations that suffer from such abuses; and might reveal legal and institutional failings that led to the use of torture, pointing to ways to improve the government’s effectiveness in fighting terrorism. It would also sharply reduce the likelihood of foreign investigations and prosecutions of US officials—which have already begun in Spain—based on the principle of universal jurisdiction, since those prosecutions are generally predicated on the responsible government’s failure to act.

Establishing Accountability

The Bush administration’s response to the revelations of detainee abuse, including the Abu Ghraib abuse scandal, which broke in 2004, was one of damage control rather than a search for truth and accountability. The majority of administration investigations undertaken from 2004 forward lacked the independence or breadth necessary to fully explore the prisoner-abuse issue. Almost all involved the military or CIA investigating itself, and focused on only one element of the treatment of detainees. None looked at the issue of rendition to torture, and none examined the role of civilian leaders who may have had authority over detainee treatment policy.

The US record on criminal accountability for detainee abuse has been abysmal. In 2007, Human Rights Watch collected information on some 350 cases of alleged abuse involving more than 600 US personnel. Despite numerous and systematic abuses, few military personnel had been punished and not a single CIA official held accountable. The highest-ranking officer prosecuted for the abuse of prisoners was a lieutenant colonel, Steven Jordan, court-martialed in 2006 for his role in the Abu Ghraib scandal, but acquitted in 2007.

When Barack Obama, untainted by the detainee abuse scandal, became president in 2009, the outlook for accountability appeared to improve. As a presidential candidate, Obama spoke of the need for a “thorough investigation” of detainee mistreatment.[5] After his election, he said there should be prosecutions if “somebody has blatantly broken the law,” but suggested otherwise when he expressed his “belief that we need to look forward as opposed to looking backwards.”[6]

On August 24, 2009, as the CIA inspector general's long-suppressed report on interrogation practices was released in heavily redacted form with new revelations about unlawful practices, US Attorney General Eric Holder announced he had appointed Assistant United States Attorney John Durham to conduct “a preliminary review into whether federal laws were violated in connection with the interrogation of specific detainees at overseas locations.” Holder added, however, that “the Department of Justice will not prosecute anyone who acted in good faith and within the scope of the legal guidance given by the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) regarding the interrogation of detainees.”[7]

Holder’s statement was in line with that made by President Obama when he released a series of Bush-era memos: “In releasing these memos, it is our intention to assure those who carried out their duties relying in good faith upon legal advice from the Department of Justice that they will not be subject to prosecution.”[8] These statements themselves follow the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005, which provides a defense to criminal charges if the official,

did not know that the practices were unlawful and a person of ordinary sense and understanding would not know the practices were unlawful. Good faith reliance on advice of counsel should be an important factor, among others, to consider in assessing whether a person of ordinary sense and understanding would have known the practices to be unlawful.[9]

The problem is that the legal advice in question—contained in memoranda drafted by the OLC, which provides authoritative legal advice to the president and all executive branch agencies—itself authorized torture and other ill-treatment. It purported to give legal sanction to practices like waterboarding, as well as long-term sleep deprivation, violent slamming of prisoners into walls, forced nudity, and confinement of prisoners into small, dark boxes. Notably, all of the memoranda were later withdrawn by subsequent OLC officials during later periods in the Bush administration.

While US officials who act in good faith reliance upon official statements of the law generally have a defense under US law against criminal prosecution, this does not mean that the Justice Department should embrace the sweeping view that all officials responsible for methods of torture explicitly contemplated under OLC memoranda are protected from criminal investigation. Indeed, for the Justice Department to take such a position would risk validating a legal strategy that seeks to negate criminal liability for wrongdoing by preemptively constructing a legal defense. If such a strategy is seen to have worked, future administrations contemplating illegal actions will also be more likely to employ it.

In assessing the good faith of those who purported to rely on OLC guidance, the Justice Department should critically inquire, on a case-by-case basis, whether a reasonable person at the time these decisions were made would be convinced that such practices were lawful. It seems doubtful that cases of the most serious abuses would pass this test. It is especially unlikely that senior officials who were responsible for authorizing torture will be protected under this calculus, particularly if they were instrumental in pressing for legal cover from the OLC, or if they influenced the drafting of the memoranda that they now claim protect them.

For the Justice Department to look primarily into the actions of low-level interrogators would also be a mistake: it would reflect a fundamental misunderstanding of how and why abuses took place. Whether it was the coercive interrogation methods approved by the Defense Department or the CIA’s secret detention program, these were top-down enterprises that involved senior US officials who were responsible for formulating, authorizing, and supervising abusive practices.

Grounds for Investigation

Over the past several years, more evidence has been placed on the public record regarding the development of illegal detention policies and the torture and ill-treatment of detainees in US custody. Thanks in particular to FOIA lawsuits brought by the ACLU and the Center for Constitutional Rights, which have yielded over 100,000 pages of government documents concerning the treatment of detainees, the public record now includes most of a report by the CIA’s inspector general into detention practices, as well as CIA background papers, other government reports, and the infamous "torture memos" that provided the administration’s legal justification for abusive interrogation techniques.[10] An extensive amount of information was also uncovered in an investigation by the Senate Armed Services Committee, which released a report on detainee abuse in 2008 that was declassified in 2009.[11] The Department of Justice inspector general issued a report about FBI involvement in detention abuse in 2008,[12] and the department’s Office of Professional Responsibility issued a report on the role of department lawyers in crafting legal memoranda which justified abusive interrogations.[13] A report by the International Committee of the Red Cross, leaked by an unknown source, also describes the treatment of “high-value” detainees in CIA custody.[14] In addition, former detainees and whistleblowers have come forward to tell their stories, and many of the principals have spoken about their roles. As described in this report, however, there is also much key evidence—beginning with President Bush’s directive authorizing CIA "black sites"—that remains secret.

In this report, our conclusion, which we believe is compelled by the evidence, is that a criminal investigation is warranted with respect to each of the following:[15]

President George W. Bush: had the ultimate authority over detainee operations and authorized the CIA secret detention program, which forcibly disappeared individuals in long-term incommunicado detention. He authorized the CIA renditions program, which he knew or should have known would result in torture. And he has publicly admitted that he approved CIA use of torture, specifically the waterboarding of two detainees. Bush never exerted his authority to stop the ill-treatment or punish those responsible.

Vice President Dick Cheney: was the driving force behind the establishment of illegal detention policies and the formulation of legal justifications for those policies. He chaired or attended numerous meetings at which specific CIA operations were discussed, beginning with the waterboarding of detainee Abu Zubaydah in 2002. He was a member of the National Security Council (NSC) “Principals Committee,” which approved and later reauthorized the use of waterboarding and other forms of torture and ill-treatment in the CIA interrogation program. Cheney has publicly admitted that he was aware of the use of waterboarding.

Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld: approved illegal interrogation methods that facilitated the use of torture and ill-treatment by US military personnel in Afghanistan and Iraq. Rumsfeld closely followed the interrogation of Guantanamo detainee Mohamed al-Qahtani who was subjected to a six-week regime of coercive interrogation that cumulatively amounted to torture. He was a member of the NSC Principals Committee, which approved the use of torture for CIA detainees. Rumsfeld never exerted his authority to stop the torture and ill-treatment of detainees even after he became aware of evidence of abuse over a three-year period beginning in early 2002.

CIA DirectorGeorge Tenet: authorized and oversaw the CIA’s use of waterboarding, near suffocation, stress positions, light and noise bombardment, sleep deprivation, and other forms of torture and ill-treatment. He was a member of the NSC Principals Committee that approved the use of torture in the CIA interrogation program. Under Tenet's direction, the CIA also “disappeared” detainees by holding them in long-term incommunicado detention in secret locations, and rendered (transferred) detainees to countries in which they were likely to be tortured and were tortured.

In addition, there should be criminal investigations into the drafting of legal memorandums seeking to justify torture, which were the basis for authorizing the CIA secret detention program. The government lawyers involved included Alberto Gonzales, counsel to the president and later attorney general; Jay Bybee, assistant attorney general in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC); John Rizzo, acting CIA general counsel; David Addington, counsel to the vice president; William J. Haynes II, Defense Department general counsel; and John Yoo, deputy assistant attorney general in OLC.

An Independent Nonpartisan Commission

The US and global public deserve a full and public accounting of the scale of abuses following the September 11 attacks, including why and how they occurred. Prosecutions, which focus on individual criminal liability, would not bring the full range of information to light. An independent, nonpartisan commission, along the lines of the 9-11 Commission, should therefore be established to examine the actions of the executive branch, the CIA, the military, and Congress, and to make recommendations to ensure that such widespread and systematic abuses are not repeated.[16]

The investigations that the US government has conducted either have been limited in scope—such as looking at violations by military personnel at a particular place in a restricted timeframe—or have lacked independence, with the military investigating itself. Congressional investigations have been limited to looking at a single agency or department. Individuals who planned or participated in the programs have yet to speak on the record.

Many of the key documents relating to the use of abusive techniques remain secret. Many of the proverbial dots remain unconnected. An independent, nonpartisan commission could provide a fuller picture of the systematic reasons behind the abuses, as well as the human, legal, and political consequences of the government’s unlawful policies.

Recommendations

To the US President

- Direct the attorney general to begin a criminal investigation into US government detention practices and interrogation methods since September 11, 2001, including the CIA detention program. The investigation should:

- examine the role of US officials, no matter their position or rank, who participated in, authorized, ordered, or had command responsibility for torture or ill-treatment and other unlawful detention practices, including enforced disappearance and rendition to torture.

To the US Congress

- Create an independent, nonpartisan commission to investigate the mistreatment of detainees in US custody since September 11, 2001, including torture, enforced disappearance, and rendition to torture. Such a commission should:

- hold hearings, have full subpoena power, compel the production of evidence, and be empowered to recommend the creation of a special prosecutor to investigate possible criminal offenses, if the attorney general has not commenced such an investigation.

To the US Government

- Consistent with its obligations under the Convention against Torture, the US government should ensure that victims of torture obtain redress, which may include providing victims with compensation where warranted outside of the judicial context.

To Foreign Governments

- Unless and until the US government pursues credible criminal investigations of the role of senior officials in the mistreatment of detainees since September 11, 2001, exercise universal jurisdiction or other forms of jurisdiction as provided under international and domestic law to prosecute US officials alleged to be involved in criminal offenses against detainees in violation of international law.

I. Background: Official Sanction for Crimes against Detainees

On September 11, 2001, four commercial airliners commandeered by al Qaeda militants crashed into the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, DC, killing nearly 3,000 people. Three days after the attacks, President Bush sought and obtained a resolution from Congress authorizing him to use “all necessary and appropriate force” against those responsible for the attacks.[17] Within weeks, the US began military operations against the al Qaeda-backed Taliban government in Afghanistan. Concurrently, senior Bush administration officials publicly endorsed and privately undertook policies in the proclaimed “global war on terror” permitting the US to circumvent its international legal obligations.

On September 16, 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney said in a television interview on NBC’s Meet the Press:

We also have to work, through, sort of the dark side, if you will. We’ve got to spend time in the shadows in the intelligence world. A lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion, using sources and methods that are available to our intelligence agencies, if we’re going to be successful. That’s the world these folks operate in, and so it’s going to be vital for us to use any means at our disposal, basically, to achieve our objective.[18]

In prepared testimony to Congress in September 2002, Cofer Black, director of the CIA’s counterterrorism unit, said, “[T]here was ‘before’ 9/11 and ‘after’ 9/11. After 9/11 the gloves come off.”[19]

During a National Security Council “War Cabinet” on September 15, CIA Director George Tenet presented options for covert CIA operations including apprehending terrorism suspects abroad and transferring them to third counties, as well as other operations.[20] Two days later, on September 17, President Bush signed a still‑classified memorandum authorizing the CIA to detain and interrogate suspected al Qaeda members and others believed to be involved in the attacks.[21]

Led by Vice President Cheney’s legal counsel, David Addington, senior administration lawyers—including then-White House counsel, and later attorney general, Alberto Gonzales—drafted a series of legal memoranda to build the legal framework for circumventing international law restraints on the interrogation of prisoners.[22] These memos essentially argued that the Geneva Conventions of 1949, the foundation treaties of war-time conduct, did not apply to individuals detained in connection to the armed conflict in Afghanistan.

A January 9, 2002 draft memo by John Yoo, deputy assistant attorney general in the OLC, advised the Defense Department that the Geneva Conventions did not apply to members of al Qaeda because it was not a state and thus not a party to the conventions. The memo said they also did not apply to the Taliban, as it could not be considered a government because Afghanistan was a “failed state.” The memo also argued that the president could suspend operation of the Geneva Conventions and that customary laws of war did not bind the US because they did not constitute federal law.[23]

William H. Taft, IV, the State Department's legal adviser, warned the argument that the president could suspend the Geneva Conventions was “legally flawed” and the memo’s reasoning was “incorrect as well as incomplete.” The argument that Afghanistan as a “failed state” was no longer a party to the Geneva Conventions was, he said, “contrary to the official position of the United States, the United Nations and all other states that have considered the issue.”[24]

In a key memo dated January 25, 2002, Gonzales urged the president to declare Taliban forces in Afghanistan and al Qaeda outside the coverage of the Geneva Conventions. This, he wrote, would preserve US “flexibility” in the “war against terrorism,” which “in my judgment … renders obsolete Geneva’s strict limitations on questioning of enemy prisoners.” Gonzales also warned that US officials involved in harsh interrogation techniques could potentially be prosecuted for war crimes under US law if the conventions applied.[25]

Gonzales wrote “it was difficult to predict with confidence” how US prosecutors might apply the Geneva Conventions’ strictures against “’outrages against personal dignity’” and “’inhuman treatment.’” He argued that declaring that Taliban and al Qaeda fighters did not have protection afforded by the Geneva Conventions “substantially reduces the threat of domestic criminal prosecution.” Gonzales expressed to President Bush the concern of military leaders that these policies might “undermine US military culture which emphasizes maintaining the highest standards of conduct in combat and could introduce an element of uncertainty in the status of adversaries.”[26] Those concerns were ignored, but proved justified.

Secretary of State Colin Powell met twice with Bush to discuss his concerns about the Yoo memo. Gen. Richard Myers, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and other military leaders voiced similar concerns.[27] Powell argued that declaring the conventions inapplicable would “reverse over a century of US policy and practice in supporting the Geneva Conventions and undermine the protections of the law of war for our troops, both in this specific conflict and in general.”[28]

In response to the objections of Powell and others, Bush slightly modified the proposed order, but did so in a manner that effectively denied protection to the detainees: on February 7, 2002, Bush announced that while the US government would apply the “principles” of the Geneva Conventions to captured members of the Taliban, it would not consider any of them to be prisoners of war (POWs) because the US did not believe they met the convention’s requirements of an armed force as they had no military hierarchy, did not wear uniforms, did not carry arms openly, and did not conduct operations in accordance with the laws and customs of war. He said the US government considered the Geneva Conventions inapplicable to captured members of al Qaeda, though “as a matter of policy, the United States Armed Forces shall continue to treat detainees humanely and, to the extent appropriate and consistent with military necessity, in a manner consistent with the principles of Geneva.”[29]

These decisions essentially reinterpreted the Geneva Conventions to suit the administration’s purposes. Most importantly, they downgraded existing international law, which must be followed, to the level of “principles,” which only should be followed. All persons detained in connection with an armed conflict, whether or not they are entitled to POW status,[30] are still legally entitled to basic protections under international law.[31] For instance, the “fundamental guarantees” described in article 75 of Protocol Additional of 1977 to the 1949 Geneva Conventions relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), which the United States has long considered reflective of customary international law (a widely supported state practice accepted as law), protects all detainees from murder, “torture of all kinds, whether physical or mental,” “corporal punishment,” and “outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment, … and any form of indecent assault.”[32]

II. Torture of Detainees in US Counterterrorism Operations

The CIA Detention Program

On September 15, 2001, CIA Director George Tenet presented the National Security Council (NSC) with options for covert CIA operations involving the abduction of terrorism suspects abroad.[33] Two days later, on September 17, President Bush signed a directive authorizing the CIA to kill, capture, detain, and interrogate suspected al Qaeda-linked terrorists.[34]

On September 26, Tenet reportedly briefed Bush and the NSC on CIA renditions operations in which suspects were transferred into the custody of third countries such as Jordan and Egypt for detention and interrogation.[35]

Meanwhile, CIA and US military personnel in Afghanistan began to interrogate detainees apprehended there, or in Pakistan and handed over to US forces in Afghanistan. At the Qali Jangi fort in northern Afghanistan, CIA and military Special Forces personnel had begun questioning individuals.[36] Detainees also began arriving at a newly created US base near Kandahar in southern Afghanistan in November 2001 and at the Bagram air base outside Kabul in December 2001. Within weeks, media reports began to surface alleging mistreatment of detainees at Qali Jangi and at the Kandahar base.[37]

Allegations of abuse against detainees by US personnel in Afghanistan continued in 2002. According to US Army documents released in 2004 and 2005, four Special Forces personnel “murdered” an Afghan in custody in August 2002.[38] In September 2002, an unnamed detainee died while in CIA custody near Kabul, reportedly of hypothermia.[39] In December 2002, two detainees at Bagram air base were beaten to death by US military guards detailed to work with military intelligence personnel on interrogations.[40] A December 2008 investigation by the Senate Armed Services Committee showed that many of the abusive techniques being considered for formal approval at Guantanamo in October 2002 were in fact already in use in Afghanistan by that time.[41] A 2004 Department of Defense report by former Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger acknowledged that “aggressive” interrogations were underway in Afghanistan from late 2001 through 2002, beyond what was approved in the relevant US army field manual on interrogation.[42]

Secret Detention Sites

Pursuant to President Bush’s September 17, 2001, order, the CIA began to set up secret detention facilities. Although much remains to be learned about the operation of these “black sites,” whose locations have never been acknowledged by the United States, there is strong evidence that the US established secret detention sites for interrogation or transfer in Afghanistan, Guantanamo, Iraq, Lithuania, Morocco, Pakistan, Poland, Romania, and Thailand.[43] The CIA's prisons, which are thought to have held some 100 detainees since 2002,[44] were the site of some of the most egregious human rights violations, many of which are described below.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which interviewed 14 of the former CIA black site detainees after their transfer to Guantanamo, gave the following description of their detention regime:

Throughout the entire period during which they were held in the CIA detention program—which ranged from sixteen months up to almost four and a half years and which, for eleven of the fourteen was over three years—the detainees were kept in continuous solitary confinement and incommunicado detention. They had no knowledge of where they were being held, no contact with persons other than their interrogators or guards. Even their guards were usually masked and, other than the absolute minimum, did not communicate in any way with the detainees. None had any real—let alone regular—contact with other persons detained, other than occasionally for the purposes of inquiry when they were confronted with another detainee. None had any contact with legal representation. The fourteen had no access to news from the outside world, apart from in the later stages of their detention when some of them occasionally received printouts of sports news from the internet and one reported receiving newspapers.

None of the fourteen had any contact with their families, either in written form or through family visits or telephone calls. They were therefore unable to inform their families of their fate. As such, the fourteen had become missing persons. In any context, such a situation, given its prolonged duration, is clearly a cause of extreme distress for both the detainees and families concerned and itself constitutes a form of ill-treatment.

In addition, the detainees were denied access to an independent third party. In order to ensure accountability, there is a need for a procedure of notification to families, and of notification and access to detained persons, under defined modalities, for a third party, such as the ICRC. That this was not practiced, to the knowledge of the ICRC, neither for the fourteen nor for any other detainee who passed through the CIA detention program, is a matter of serious concern.[45]

After news of the sites became public, Bush in September 2006 officially acknowledged the existence of the secret CIA sites, saying:

[A] small number of suspected terrorist leaders and operatives captured during the war have been held and questioned outside the United States, in a separate program operated by the Central Intelligence Agency.... Many specifics of this program, including where these detainees have been held and the details of their confinement, cannot be divulged.[46]

He ordered what he said were the remaining 14 detainees in CIA custody transferred to Guantanamo Bay.[47]

On January 22, 2009, his second full day in office, President Obama issued an executive order to close the CIA’s secret detention program.[48]

The Case of Abu Zubaydah: the First Detainee in the CIA Interrogation Program

In late March 2002, the CIA in Faisalabad, Pakistan, apprehended Zayn al Abidin Muhammad Husayn, more commonly known as Abu Zubaydah. Zubaydah was shot during his arrest and taken to a hospital in Lahore, Pakistan, before being transferred to a secret CIA facility, apparently in Bangkok, Thailand.[49]

Zubaydah was originally believed to be a top al Qaeda operative, and his interrogation became a test case for the CIA’s evolving new role in detention and interrogation under Bush’s September 17, 2001 directive.

A 2009 “Declassified Narrative Describing the Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel's Opinions on the CIA's Detention and Interrogation Program,” released by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in 2009 describes in detail the NSC approval process of the CIA interrogation policy regarding Abu Zubaydah:

CIA records indicate that members of the National Security Council (NSC) and other senior Administration officials were briefed on the CIA’s detention and interrogation program throughout the course of the program. In April 2002, attorneys from the CIA’s Office of General Counsel began discussions with the Legal Adviser to the National Security Council and OLC concerning the CIA’s proposed interrogation plan for Abu Zubaydah and legal restrictions on that interrogation. CIA records indicate that the Legal Adviser to the National Security Council [John Bellinger] briefed the National Security Adviser [Condoleezza Rice], Deputy National Security Adviser [Stephen Hadley], and Counsel to the President [Alberto Gonzales], as well as the Attorney General [John Ashcroft] and the head of the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice [Michael Chertoff].

According to CIA records, because the CIA believed that Abu Zubaydah was withholding imminent threat information during the initial interrogation sessions, attorneys from the CIA's Office of General Counsel [headed by John Rizzo] met with the Attorney General [John Ashcroft], the National Security Adviser [Condoleezza Rice], the Deputy National Security Adviser [Stephen Hadley], the Legal Adviser to the National Security Council [John Bellinger], and the Counsel to the President [Alberto Gonzales], in mid-May 2002 to discuss the possible use of alternative interrogation methods that differed from the traditional methods used by the US military and intelligence community. At this meeting, the CIA proposed particular alternative interrogation methods, including waterboarding.

The CIA's Office of General Counsel subsequently asked OLC to prepare an opinion about the legality of its proposed techniques. To enable OLC to review the legality of the techniques, the CIA provided OLC with written and oral descriptions of the proposed techniques. The CIA also provided OLC with information about any medical and psychological effects of DoD's [Department of Defense] Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) School, which is a military training program during which military personnel receive counter‑interrogation training.[50]

The SERE techniques had been used by the Defense Department’s Joint Personnel Recovery Agency (JPRA) to train US Special Forces to withstand interrogation methods used by enemies who did not abide by the Geneva Conventions.[51] These SERE techniques were described in a 2008 Senate Armed Services Committee report (“Levin Report” or “SASC Report”) as including:

[S]tripping students of their clothing, placing them in stress positions, putting hoods over their heads, disrupting their sleep, treating them like animals, subjecting them to loud music and flashing lights, and exposing them to extreme temperatures. It can also include face and body slaps and until recently…, it included waterboarding.[52]

The CIA and NSC, in essence, were advising that CIA interrogators use techniques modeled on interrogations conducted by past enemies of the US that did not abide by the Geneva Conventions.

In his memoirs, Bush describes approving the waterboarding of Abu Zubaydah:

At my direction, Department of Justice and CIA lawyers conducted a careful legal review. They concluded that the enhanced interrogation program complied with the Constitution and all applicable laws, including those that ban torture.

I took a look at the list of techniques. There were two that I felt went too far, even if they were legal. I directed the CIA not to use them. Another technique was waterboarding, a process of simulated drowning. No doubt the procedure was tough, but medical experts assured the CIA that it did no lasting harm.

…I would have preferred that we get the information another way. But the choice between security and values was real. Had I not authorized waterboarding on senior al Qaeda leaders, I would have had to accept a greater risk that the country would be attacked. In the wake of 9/11, that was a risk I was unwilling to take. My most solemn responsibility as president was to protect the country. I approved the use of the interrogation techniques.[53]

The SSCI Narrative Report continues:

On July 13, 2002, according to CIA records, attorneys from the CIA's Office of General Counsel met with the Legal Adviser to the National Security Council, a Deputy Assistant Attorney General from OLC, the head of the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice, the chief of staff to the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Counsel to the President to provide an overview of the proposed interrogation plan for Abu Zubaydah. On July 17, 2002, according to CIA records, the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) [George Tenet] met with the National Security Advisor[Condoleezza Rice], who advised that the CIA could proceed with its proposed interrogation of Abu Zubaydah. This advice, which authorized CIA to proceed as a policy matter, was subject to a determination of legality by OLC.

On July 24, 2002, according to CIA records, OLC orally advised the CIA that the Attorney General had concluded that certain proposed interrogation techniques were lawful and, on July 26, that the use of waterboarding was lawful. OLC issued two written opinions and a letter memorializing those conclusions on August 1, 2002.[54]

The two August 1 OLC memos, signed by Assistant Attorney General Jay Bybee and largely written by Deputy Assistant Attorney General John Yoo, included what has become known as the “First Bybee Memo” or “Torture Memo.” It found that torturing al Qaeda detainees in captivity abroad may be “justified,” and that international laws against torture "may be unconstitutional if applied to interrogations" conducted in the “circumstances of the current war.” The memo added that the doctrines of "necessity and self-defense could provide justifications that would eliminate any criminal liability" on the part of officials who tortured al Qaeda detainees.[55]

The memo also took an extremely narrow view of which acts might constitute torture. It referred to seven practices that US courts have ruled constitute torture: severe beatings with truncheons and clubs, threats of imminent death, burning with cigarettes, electric shocks to genitalia, rape or sexual assault, and forcing a prisoner to watch the torture of another person. It then advised that “interrogation techniques would have to be similar to these in their extreme nature and in the type of harm caused to violate law.” The memo asserted that “physical pain amounting to torture must be equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death.” The memo also suggested that "mental torture" only included acts that resulted in "significant psychological harm of significant duration, e.g., lasting for months or even years."[56]

A second Bybee memo, declassified in 2009, addressed the legality of 10 specific interrogation tactics, including waterboarding, against Abu Zubaydah (who was incorrectly described in the memo as “one of the highest ranking members of the al Qaeda terrorist organization”). The opinion described in great detail how the techniques should be used, including placing the detainee “in a cramped confinement box with an insect” as “he appears to have a fear of insects” as well as waterboarding, which the Bybee memo concluded did not constitute torture because it did not result in “prolonged mental harm.”[57]

With these approvals, CIA officials began using more abusive interrogation methods on Zubaydah. According to The New York Times, “At times, Mr. Zubaydah, still weak from his wounds, was stripped and placed in a cell without a bunk or blankets. He stood or lay on the bare floor, sometimes with air-conditioning adjusted so that, one official said, Mr. Zubaydah seemed to turn blue. At other times, the interrogators piped in deafening blasts of music by groups like the Red Hot Chili Peppers.”[58]According to the ICRC report, Zubaydah claimed he was slammed directly against a hard concrete wall. Zubaydah was waterboarded 83 times.[59]

Zubaydah later told the ICRC that while being waterboarded he struggled against the straps, causing pain in his wounds, and that he usually vomited after each “suffocation”:

I was ... put on what looked like a hospital bed, and strapped down very tightly with belts. A black cloth was then placed over my face and the interrogators used a mineral water bottle to pour water on the cloth so that I could not breathe. After a few minutes the cloth was removed and the bed was rotated into an upright position. The pressure of the straps on my wounds was very painful. I vomited. The bed was then again lowered to horizontal position and the same torture carried out again with the black cloth over my face and water poured on from a bottle. On this occasion my head was in a more backward, downwards position and the water was poured on for a longer time. I struggled against the straps, trying to breathe, but it was hopeless. I thought I was going to die. I lost control of my urine. Since then I still lose control of my urine when under stress.

I was then placed again in the tall box. While I was inside the box loud music was played again and somebody kept banging repeatedly on the box from the outside. I tried to sit down on the floor, but because of the small space the bucket with urine tipped over and spilt over me…. I was then taken out and again a towel was wrapped around my neck and I was smashed into the wall with the plywood covering and repeatedly slapped in the face by the same two interrogators as before.[60]

In 2007, Zubaydah told a tribunal at Guantanamo Bay that much information he provided to interrogators while he was subjected to what he called “torture” were not true.[61]

The CIA videotaped Zubaydah’s interrogations. In 2005, however, the agency destroyed 90 videotapes of Zubaydah's interrogations, which resulted in a criminal investigation of officials. In November 2010, Justice Department officials confirmed that no charges would be filed in connection with the destruction of the tapes.[62]

As of this writing, Zubaydah remains in Guantanamo. He has not been charged with any offense. Although Bush had described Zubaydah as “one of al Qaeda’s top operatives plotting and planning death and destruction on the United States,”[63] in 2009 the Justice Department recognized that Zubaydah did not have “any direct role in or advance knowledge of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.”[64] While there is much debate over the value of the information he provided, the Washington Post concluded that, “not a single significant plot was foiled as a result of Abu Zubaida's tortured confessions according to former senior government officials who closely followed the interrogations.”[65]

Growth of the CIA Program

Many of the same interrogation methods used on Zubaydah were later used on other detainees in CIA custody, including Abd al-Rahim al-Naishiri, who was apprehended in the United Arab Emirates in August 2002; Ramzi Bin al Shibh, apprehended in Pakistan in September 2002; Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, apprehended in Pakistan in March 2003; and Riduan Isamuddin, also known as Hambali, apprehended in Bangkok in August 2003.

In February 2008, CIA Director Michael Hayden and OLC head Stephen Bradbury confirmed that waterboarding was used on CIA detainees; Hayden mentioned waterboarding being used on al-Nashiri, Zubaydah, and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed specifically.[66]The ICRC interviewed the 14 “high-value” detainees after they had been moved to Guantanamo and found that three had allegedly been waterboarded, among other unlawful methods.[67]According to its report:

The methods of ill-treatment alleged to have been used include the following:

Suffocation by water poured over a cloth placed over the nose and mouth [waterboarding], alleged by three of the fourteen.

Prolonged stress standing position, naked, held with the arms extended and chained above the head, as alleged by ten of the fourteen, for periods from two or three days continuously, and for up to two or three months intermittently, during which period toilet access was sometimes denied resulting in allegations from four detainees that they had to defecate and urinate over themselves.

Beatings by use of a collar held around the detainee’s neck and used to forcefully bang the head and body against the wall, alleged by six of the fourteen.

Beating and kicking, including slapping, punching, kicking to the body and face, alleged by nine of the fourteen.

Confinement in a box to severely restrict movement alleged in the case of one detainee.

Prolonged nudity alleged by eleven of the fourteen during detention, interrogation and ill-treatment; this enforced nudity lasted for periods ranging from several weeks to several months.

Sleep deprivation was alleged by eleven of the fourteen through days of interrogation, through use of forced stress positions (standing or sitting), cold water and use of repetitive loud noise or music. One detainee was kept sitting on a chair for prolonged periods of time.

Exposure to cold temperature was alleged by most of the fourteen, especially via cold cells and interrogation rooms, and for seven of them, by the use of cold water poured over the body or, as alleged by three of the detainees, held around the body by means of a plastic sheet to create an immersion bath with just the head out of the water.

Prolonged shackling of hands and/or feet was alleged by many of the fourteen.

Threats of ill-treatment to the detainee and/or his family, alleged by nine of the fourteen.

Forced shaving of the head and beard, alleged by two of the fourteen.

Deprivation/restricted provision of solid food from 3 days to 1 month after arrest, alleged by eight of the fourteen.

…each specific method was … in fact applied in combination with other methods, either simultaneously, or in succession.[68]

The CIA inspector general’s report, finally released in heavily redacted form in 2009, details incidents including mock executions, waterboarding, execution threats using an unloaded semi-automatic handgun, smoke inhalation to provoke vomiting, threatening a naked and hooded detainee with a revving power drill, death threats and threats against family members, and pressing on pressure points to provoke repeated fainting.[69]

The expansion of the CIA program was later discussed and authorized, after the fact, in a meeting at the White House in early 2003. As the 2009 SSCI narrative states:

In the spring of 2003, the DCI [George Tenet] asked for a reaffirmation of the policies and practices in the interrogation program. In July 2003, according to CIA records, the NSC Principals met to discuss the interrogation techniques employed in the CIA program. According to CIA records, the DCI [George Tenet] and the CIA’s General Counsel [John Rizzo] attended a meeting with the Vice President [Dick Cheney], the National Security Adviser [Condoleezza Rice], the Attorney General [John Ashcroft], the Acting Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel, [Ed Whelan],[70] a Deputy Assistant Attorney General [possibly John Yoo],the Counsel to the President [Alberto Gonzales], and the Legal Adviser to the National Security Council [John Bellinger] to describe the CIA’s interrogation techniques, including waterboarding. According to CIA records, at the conclusion of that meeting, the Principals reaffirmed that the CIA program was lawful and reflected administration policy [emphasis added].[71]

The report adds that on September 16, 2003, “pursuant to a request from the National Security Adviser [Rice], the Director of Central Intelligence [Tenet] subsequently briefed the Secretary of State [Powell] and the Secretary of Defense [Rumsfeld] on the CIA’s interrogation techniques.”[72]

The CIA detention and interrogation program appears to have been scaled back temporarily in 2004, after the Abu Ghraib scandal and a critical report by the CIA inspector general that was sent to the White House in May 2004.

There had been significant controversy within the CIA about the program, leading to an investigation by the CIA Office of Inspector General which took place through 2003 and into 2004. On May 7, 2004, only a few weeks after news of the abuse of detainees at Abu Ghraib broke, the CIA’s Inspector General John Helgerson, despite being reprimanded by a reportedly furious Vice President Cheney,[73] issued a classified report, a copy of which was sent to the highest levels of the White House, the CIA, and to the committee chairman and vice chairman and senior staff of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.[74]

The CIA inspector general’s report appears to have caused considerable anxiety within the White House. According to the SSCI narrative, CIA General Counsel John Rizzo attended a meeting in May 2004 with Alberto Gonzales, David Addington, John Bellinger, and several “senior Department of Justice officials” to discuss the CIA’s program and the Inspector General’s report.[75] The new OLC head, Jack Goldsmith, apparently also raised concerns with the legal analysis in earlier OLC memos, and in June 2004 Goldsmith withdrew the OLC’s unclassified August 1, 2002 opinion on the federal torture statute.[76] For reasons that are unclear, the OLC did not withdraw the classified August 1, 2002 opinion on the Zubaydah interrogation.

However, in May 2005, the new OLC head, Stephen Bradbury, issued three memoranda to the CIA embracing many of the earlier arguments in the Bybee memorandum applicable to Abu Zubaydah, and—years after the fact—formally authorizing the expansion of the techniques originally approved in 2002 to other detainees.[77] The Bradbury memoranda were declassified in 2009 along with the Second Bybee Memo.

After the Bradbury memoranda were approved, the NSC Principals Committee met on May 31, 2005. The Principals Committee, now chaired by Stephen Hadley and including Alberto Gonzales, Condoleezza Rice, and David Addington, among others, “approved” all of the techniques discussed in the May 2005 memoranda, presumably recommending to the president that he reauthorize the program, which he did.[78]

President Bush revealed the existence of the CIA detention and interrogation program a year later, in a public speech at the White House on September 6, 2006, acknowledging that suspects had been held “secretly” “outside the United States.” “[A] reason the terrorists have not succeeded,” he stated while introducing his justifications for the CIA program, “is because our government has changed its policies and given our military, intelligence and law enforcement personnel the tools they need to fight this enemy and protect our people and preserve our freedoms.”[79] Bush reauthorized the program in July 2007.[80]

The CIA Rendition Program

The CIA has regularly transferred detainees to countries known to routinely practice torture, a practice often referred to as “extraordinary rendition.”

While the US practice of rendering terrorist suspects abroad predates the September 11 attacks, the CIA’s rendition practices changed after they occurred. Rather than returning people to their home or third countries to face “justice” (albeit justice that often included torture and grossly unfair trials), the CIA began handing people over to their home or third countries, apparently to facilitate abusive interrogations.[81]

The secrecy surrounding the rendition program means that no accurate statistics exist. One study found 53 such cases, excluding those sent to Afghanistan or into US custody.[82] One such country, Jordan, was notorious for torturing security detainees, which would have been well known to US officials at the time of the transfers. Many detainees were returned to CIA custody immediately after intensive periods of abusive interrogation in Jordan.

Numerous detainees so rendered are known or believed to have been tortured. The following cases are illustrative:

Maher Arar, a Syrian-born Canadian national in transit from a family vacation through John F. Kennedy Airport in New York City was detained by US authorities acting on incorrect information from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.[83] After holding him incommunicado for nearly two weeks, US authorities flew him to Jordan, where he was driven across the border and handed over to Syrian authorities, despite his statements to US officials that he would be tortured if sent there. Indeed, he was tortured during his confinement in a Syrian prison, often with cables and electrical cords.[84] Following an extensive investigation by the Canadian government, which cleared Arar of all terror connections, Canada offered him a formal apology and compensation of 10.5 million Canadian dollars (US$10.75 million) plus legal fees for providing the unsubstantiated information to US officials.[85] In contrast, the Bush administration refused to assist the Canadian inquiry and disregarded Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s request that the US acknowledge its inappropriate conduct. When Arar sued the US for denying him his civil rights, the Bush administration—and later the Obama administration—successfully argued the case should never be allowed to come to trial for reasons of national security.[86]

In early October 2001, Australian citizen Mamdouh Habib was arrested in Pakistan. Pakistan’s interior minister later said that Habib was sent to Egypt on US orders and in US custody.[87] Habib says that while detained in Egypt for six months, he was suspended from hooks on the wall, rammed with an electric cattle prod, forced to stand on tiptoe in a water-filled room, and threatened by a German shepherd dog.[88] In 2002, Habib was transferred from Egypt to Bagram air base in Afghanistan, then to Guantanamo Bay. On January 28, 2005, Habib was sent home from Guantanamo to Sydney, Australia.[89] In 2010, Habib sued the Australian government, claiming Australian officials were complicit in his false imprisonment and assault in Pakistan, Egypt, and Guantanamo.[90] In January 2011, the Australian government paid Habib an undisclosed amount to absolve it of legal liability in the case.[91]

In December 2001, Swedish authorities handed two Egyptians, Ahmed Agiza and Mohammed al-Zari, to CIA operatives at Bromma Airport in Stockholm. The operatives stripped them, inserted suppositories into their rectums, dressed them in a diaper and overalls, blindfolded them, and placed a hood over their heads. They were then placed aboard a US government-leased plane and flown to Egypt.[92] There the two men were reportedly regularly subjected to electric shocks and other mistreatment, including in Cairo’s notorious Tora prison.[93]

On November 16, 2003, Osama Moustafa Nasr—also known as “Abu Omar”—went missing in Milan. Sometime in 2004, he phoned his wife and friends in Milan and reportedly described being stopped in the street “by Western people,” forced into a car, and taken to an air force base.[94] From the airbase, Nasr was flown to Cairo via Germany and turned over to Egypt's secret police, the State Security Intelligence, at Tora prison.[95] There, Nasr alleged being tortured with electric shocks, beatings, rape threats, and genital abuse.[96] The UK’s Sunday Times reported that Nasr “claimed he had been tortured so badly by secret police in Cairo that he had lost hearing in one ear.”[97] In February 2007, after four years of detention, Nasr was released by an Egyptian court, which found that his detention was “unfounded.”[98] Following a subsequent police investigation and indictment, on November 4, 2009, a judge in Milan convicted, in absentia, 22 CIA agents, a US Air Force colonel, and two Italian secret agents for the kidnapping—the first and only convictions anywhere in the world against people involved in the CIA’s extraordinary renditions program.[99] The convictions were confirmed on appeal, and the sentences increased. Each received a sentence of between seven and nine years’ imprisonment, and were ordered to pay €1 million (US$1.44 million) to Nasr and €500,000 (US$720,469) to Nasr's wife.[100] The Italian government has, to date, refused the prosecutor’s request to seek extradition of the US agents.[101]

In November 2001, Muhammad Haydar Zammar, a German citizen of Syrian descent,[102] was arrested in Morocco and flown to Syria.[103] Moroccan government sources have told reporters that the CIA asked them to arrest Zammar and send him to Syria,[104] and that CIA agents took part in his interrogation sessions in Morocco.[105] Zammar was taken to the same Syrian prison where Maher Arar was held.[106] On July 1, 2002, TimeMagazine reported:

US officials tell Time that no Americans are in the room with the Syrian who interrogate Zammar. US officials in Damascus submit written questions to the Syrians, who relay Zammar’s answers back. State Department officials like the arrangement because it insulates the US government from any torture the Syrians may be applying to Zammar. And some State Department officials suspect that Zammar is being tortured.[107]

Muhammad Saad Iqbal Madni, a Pakistani national, was arrested in Jakarta, Indonesia on January 9, 2002. Indonesian officials and diplomats told The Washington Post this was done at the CIA’s request. Several days later, Egypt made a formal request that Indonesia extradite Madni for unspecified, terrorism-related crimes. However, according to “a senior Indonesian government official … [t]his was a US deal all along.… Egypt just provided the formalities.”[108] On January 11, the Indonesian officials said, Madni was taken onto a US registered Gulfstream V jet at a military airport, and flown to Egypt for interrogation.[109]The New York Times reported that “Iqbal said he had been beaten, tightly shackled, covered with a hood and given drugs, subjected to electric shocks and, because he denied knowing Bin Laden, deprived of sleep for six months”; in his own words, “[t]hey make me blind and stand up for whole days.”[110] On September 11, 2004, the Times of London reported that despite repeated inquiries by Madni’s relatives, “nothing has been seen or heard from” him since he was taken from Jakarta.[111] However, he was later transferred to Bagram air base in Afghanistan,[112] and from there to Guantanamo Bay.[113] He later stated that he had attempted suicide.[114] He was ultimately repatriated in August 2008, after spending more than six years in US custody. At that time, he was reported to have difficulty walking, his left ear was infected and was operated on by a Pakistani surgeon, he was receiving physical therapy for back problems, and he was “dependent on a cocktail of antibiotics and antidepressants.”[115]

Coercive Interrogations by the Military

The NSC’s approval of coercive interrogation techniques by the CIA in 2002 set the stage for approval of similar unlawful methods for military interrogators at Guantanamo Bay, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

Abuses by Military Interrogators in Afghanistan, Guantanamo, and Iraq

Abusive interrogations by the military appear to have begun in Afghanistan as early as December 2001 and continued despite high-profile media accounts, and perhaps encouraged by the sidelining and disparaging of the Geneva Conventions by US officials.

Reports by civilian Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents who witnessed detainee abuse by military personnel at Guantanamo—including forcing chained detainees to sit in their own excrement—reinforced accounts by former detainees describing the use of painful stress positions, extended solitary confinement, military dogs to threaten them, threats of torture and death, and prolonged exposure to extremes of heat, cold, and noise.[116] Videotapes of military riot squads subduing suspects reportedly show the guards punching some detainees, tying one to a gurney for questioning and forcing a dozen to strip from the waist down.[117] Former detainees said they were subjected to weeks and even months in solitary confinement—which was at times either suffocatingly hot, or cold from excessive air conditioning—as punishment for not cooperating in interrogations or for violating prison rules.[118]

Many techniques used on detainees by military personnel at Abu Ghraib prison and other Iraqi locations resembled abuse seen earlier in Afghanistan and Guantanamo, including forced standing and exercise, shackling detainees in painful positions or close confinement, extensive long-term sleep deprivation, and exposure to cold.[119]

Abuse spread throughout Iraq from late 2003 and into 2004. Documented cases included beatings and suffocation,[120] sexual abuse,[121] mock executions,[122] and electro-shock torture.[123] Human Rights Watch reported in 2006 on serious abuses by military Special Mission Unit Task Force units in Iraq, including allegations of beatings, exposure to extreme cold or heat, threats of death, sleep deprivation, various forms of psychological torture or mistreatment, painful stress positions, and in one instance, giving a prisoner urine to drink.[124] These abuses received considerable internal military attention and media coverage from 2004 to 2006.[125]

Approving Illegal Techniques for Military Interrogation

While the Bush administration sought to portray the decision to allow the military to use aggressive interrogation methods as originating from Guantanamo,[126] reconstructions of the events, including those provided in a book by lawyer Philippe Sands, indicate the decision came from above, from Defense Secretary Rumsfeld, Defense General Counsel Haynes, Vice President Cheney’s legal counsel David Addington, and White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales, among others.[127]

The Office of the Secretary of Defense began in December 2001 to inquire about Joint Personnel Recovery Agency’s aggressive SERE techniques.[128] Not long after, JPRA personnel provided: training materials to Guantanamo interrogators in February 2002;[129] training to DIA personnel deploying to Afghanistan and Guantanamo in March 2002; at least one written “Draft Exploitation Plan” for possible dissemination to various military and intelligence-gathering agencies in April 2002;[130] and written materials and advice on the use of SERE mock interrogation techniques to psychologists working with interrogators in Guantanamo in June and July 2002.

The tactics used in mock SERE interrogations resembled many of the practices used immediately afterwards in Afghanistan and Guantanamo. These included stripping detainees naked for degradation purposes, exploiting cultural or religious taboos, and use of forced standing, exposure to cold, and prolonged sleep deprivation.

In July 2002, as the Bybee memos were being drafted to permit abusive techniques on Abu Zubaydah, Defense Deputy General Counsel Richard Shiffrin, on behalf of General Counsel Haynes, requested SERE instructor lesson plans, a list of the mock interrogation techniques used in SERE training, and a memorandum describing the “long-term psychological effects” of SERE training on students, and in particular the effects of waterboarding, a document which was also given to the CIA and OLC when they were drafting the August 1, 2002 Abu Zubaydah memorandum.[131] The SASC Report explains:

The list of SERE techniques included such methods as sensory deprivation, sleep disruption, stress positions, waterboarding, and slapping.… Mr. Shiffrin, the DoD Deputy General Counsel for Intelligence, confirmed that a purpose of the request was to “reverse engineer” the techniques.[132]

In mid-September 2002, JPRA staff trained Guantanamo personnel, using abusive techniques used in SERE schools.[133]

A week later, on September 25, 2002, a delegation of senior officials visited Guantanamo to discuss interrogations there.[134] The group included Defense General Counsel Haynes, CIA General Counsel Rizzo, Chief of the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice Michael Chertoff, the Vice President’s counsel Addington (“the guy in charge” according to the military lawyer present),[135] and Gonzales, counsel to the president. According to the SASC Report, Guantanamo commander Maj. Gen. Michael Dunlavey briefed the group on a number of issues including “policy constraints” affecting interrogations. Gen. Dunlavey told Philippe Sands that the group discussed the interrogation of Mohamed al-Qahtani, a detainee suspected of direct involvement in the September 11 attacks. “They wanted to know what we were doing to get to this guy … and Addington was interested in how we were managing it.” Lt. Col. Diane Beaver, Gen. Dunlavey’s senior counsel, confirmed Dunlavey’s account, telling Sands the group had essentially delivered the message to do “whatever needed to be done.”[136]

By October 11, 2002, Dunlavey sent a memo and an attached legal opinion by Lt. Col. Beaver to Gen. James Hill of Southern Command requesting authority to use aggressive interrogation techniques.[137] They included techniques aimed at humiliation and sensory deprivation including use of stress positions, forced standing, isolation for up to 30 days, deprivation of light and sound, 20-hour interrogations, removal of religious items, removal of clothing, forcible grooming such as the shaving of facial hair, and exploiting individual phobias such as fear of dogs. A higher category of techniques included the use of “mild, non-injurious physical contact,” described as grabbing, poking, and light pushing; use of scenarios designed to convince the detainee that death or severely painful consequences were imminent for him or his family; exposure to cold weather or water; and, notably, waterboarding.

In late October 2002, the documents were sent from Gen. Hill to Gen. Richard Meyers, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, with recommendations that the secretary of defense authorize the techniques listed.

On November 14, 2002, Col. Britt Mallow, a senior commander at the Criminal Investigation Task Force (CITF) at Guantanamo who had already raised concerns about abusive interrogations with senior Pentagon officials, together with others expressed his legal concerns to Guantanamo commander Gen. Geoffrey Miller and Defense General Counsel Haynes.[138]

One FBI agent, Jim Clemente, an attorney and former prosecutor, warned that the proposed interrogation plans violated the federal torture statute and that interrogations could lead to prosecution,[139] concerns that were shared with FBI Director Robert Mueller, and senior attorneys in the Defense Department’s General Counsel’s office.[140] At the same time, the FBI reported already ongoing abuses to the Defense Department General Counsel’s office.[141]

Nevertheless, General Counsel Haynes submitted the techniques to Defense Secretary Rumsfeld for approval in late November 2002, with a one-page cover letter recommending he approve most of the methods—but not waterboarding.[142] Rumsfeld approved the recommended techniques, including:

“The use of stress positions (like standing) for a maximum of four hours”;

“Use of the isolation facility for up to 30 days”;

“The detainee may also have a hood placed over his head during transportation and questioning”;

“Deprivation of light and auditory stimuli”;

“Removal of all comfort items (including religious items)”;

“Forced grooming (shaving of facial hair, etc)”;

“Removal of clothing”; and

“Using detainees’ individual phobias (such as fear of dogs) to induce stress.”[143]

Rumsfeld appended a handwritten note to his authorization of these techniques: “I stand for 8-10 hours a day. Why is standing limited to 4 hours?”[144]

Those captured or otherwise taken into custody during the international armed conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan should have been presumptively classified as POWs, and afforded the protections due to POWs under the Third Geneva Convention.[145] In any case, the coercive interrogation methods used were in violation of the protections afforded to all detainees under article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 (Common Article 3) and other prohibitions on inhuman treatment found in customary international law.[146] And individuals responsible for carrying out or ordering torture or other inhuman treatment of detainees, whether or not they have POW status, may be prosecuted for war crimes.

Within weeks, JPRA SERE school personnel were again training Guantanamo interrogators.[147] But controversy continued to brew after Rumsfeld’s order.

Navy General Counsel Alberto Mora took his concerns to the secretary of the Navy, Gordon England, and with England’s approval spoke with Defense’s Haynes three times to warn him about the potential criminal liability associated with the al-Qahtani interrogation and Rumsfeld’s December 2, 2002 memorandum. Mora’s concerns were also put before Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, Jane Dalton, the general counsel to the Joint Chiefs, and Rumsfeld himself.[148] On January 9, 2003, Mora warned Haynes that the “interrogation policies could threaten Secretary Rumsfeld’s tenure and could even damage the presidency.”[149] Mora also left a memorandum with Haynes written by Navy JAG Corps Commander Stephen Gallotta, stating that some of the techniques authorized by Rumsfeld in his December 2, 2002 order, taken alone and especially when taken together, could amount to torture; that some constituted assault; and that most of the techniques, absent lawful purpose, were “per se unlawful.”[150]