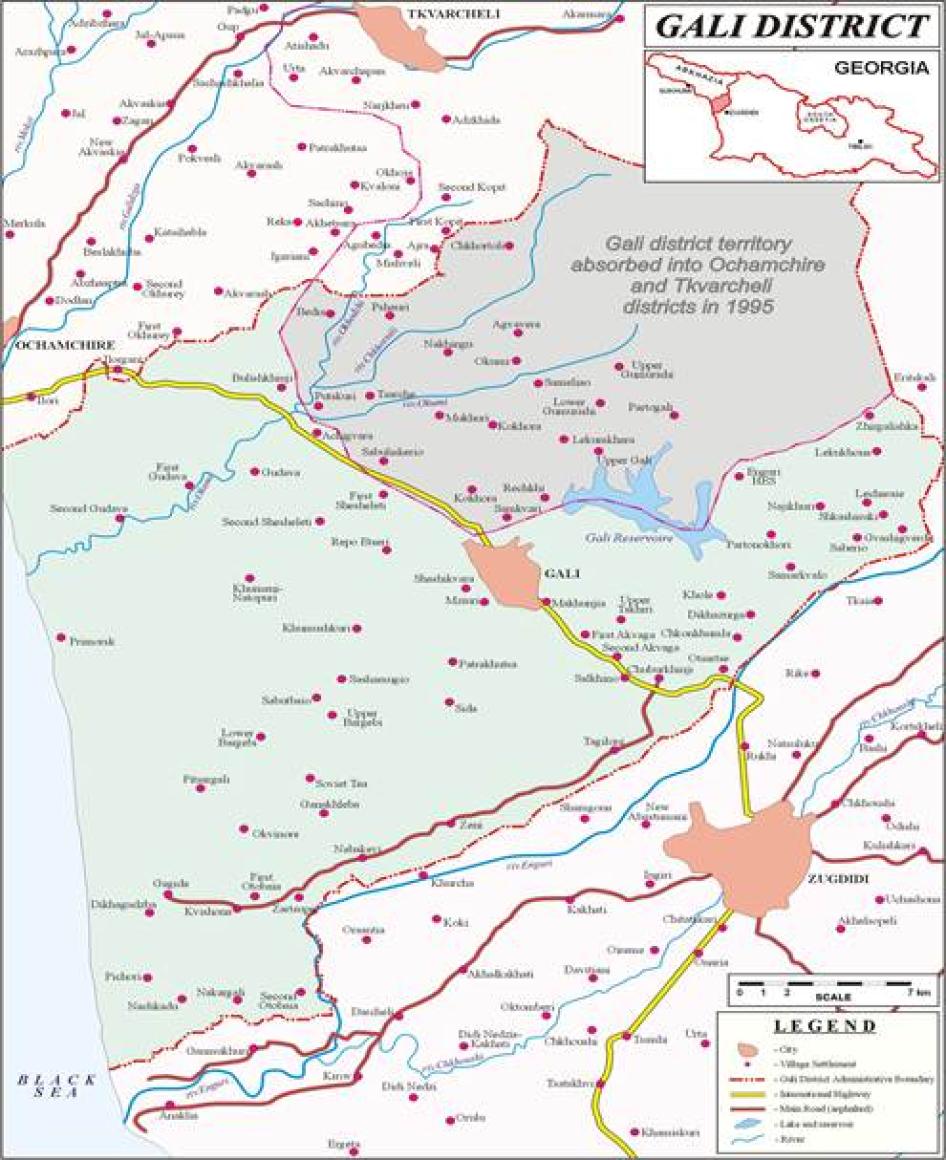

Map of Gali District

© Human Rights Watch 2011

This map is for reference only and does not imply political endorsement of its content.

Summary

Almost 18 years after a cease-fire ended the Georgian-Abkhaz war, the conflict over the breakaway region of Abkhazia remains as far from a political resolution as ever, leaving in limbo the lives of more than 200,000 people, mostly ethnic Georgians displaced by the conflict. The only area of Abkhazia where the de facto authorities in the breakaway region have allowed returns of displaced persons is the southernmost district of Gali, where ethnic Georgians constituted 96 percent of the pre- conflict population. About 47,000 displaced people have returned to their homes in Gali district. But the Abkhaz authorities have erected barriers to their enjoyment of a range of civil and political rights.

This report documents the Abkhaz authorities’ arbitrary interference with returnees’ rights to freedom of movement, education, and other rights in Abkhazia. It is based on interviews with more than one hundred Gali residents conducted on both sides of the administrative boundary line, officials of the de facto Abkhaz administration, and representatives of international governmental and non-governmental organizations working in Abkhazia.

Armed conflict broke out in Abkhazia between the Georgian military and breakaway Abkhaz forces in summer 1992. A ceasefire agreed in May 1994 largely held until August 2008, when a short war broke out between Georgia and Russia over South Ossetia, another breakaway region of Georgia. The war in South Ossetia significantly altered the situation in Abkhazia as well. Abkhaz security forces occupied the Kodori gorge, the only pre-conflict part of Abkhazia over which the Georgian government had previously retained control, and all existing negotiations and conflict resolution mechanisms collapsed.

Although Russia and several other states have recognized Abkhazia, the territory is internationally recognized as part of Georgia.

Following its recognition of Abkhazia in December 2008, Russia vetoed the extension of the Organization for Security and Co-operation (OSCE) mission in Georgia, arguing that the OSCE should have separate missions in South Ossetia and Georgia. Using a similar argument, in June 2009, Russia vetoed the extension of the mandate for United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia (UNOMIG), which had maintained more than 120 military observers along the ceasefire line for 16 years and had led international efforts to resolve the conflict in Abkhazia. Russian border guards replaced Russian peacekeepers on the Abkhaz side of the administrative boundary line.

The Georgian and Abkhaz sides have continued talks under various auspices, but negotiations have made little progress. In the face of the political stalemate there is little or no prospect for the dignified and secure return of the thousands of people who remain displaced from their homes in Abkhazia. For a short period in 1994, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) facilitated the resettlement of several hundred people to Gali district. The spontaneous return of Gali residents continued well after that. In early 1999 the Abkhaz authorities launched a unilateral initiative to implement returns to Gali district. Many families went back, initially commuting daily across the ceasefire line, and migrating seasonally to tend their fields and look after their property.

However, the Abkhaz authorities’ arbitrary interference with the rights of ethnic Georgian returnees has driven some of those who have returned to their homes to leave Gali district and go back to uncontested areas of Georgia. This in turn has presented serious obstacles for larger scale, sustainable returns of displaced persons to their homes in the breakaway region.

The de facto authorities require all residents of Abkhazia to obtain Abkhaz passports as a prerequisite for the enjoyment of certain rights, such as the right to work in the public sector, to vote and run for public office, to obtain a high school diploma, to undertake property transactions or to commute freely across the administrative boundary line which separates Abkhazia from uncontested areas of Georgia.

The procedure for obtaining such documents is discriminatory and onerous for ethnic Georgian returnees. Abkhaz law automatically grants the right to a passport to all ethnic Abkhaz as well as to all people, regardless of their ethnicity, who had resided in Abkhazia for at least five years at the time of the 1999 declaration of independence. These criteria automatically exclude ethnic Georgians who were displaced by the fighting in 1992-1993 but who subsequently returned and are now resident in Gali district.

Ethnic Georgians can receive Abkhaz passports through naturalization. However this process is excessively burdensome, requiring ethnic Georgians to collect, translate, and file a large number of documents, some of which they do not always possess. Moreover, the process requires ethnic Georgians to renounce their Georgian citizenship. The Abkhaz authorities emphasize that they do not compel anyone to obtain Abkhaz citizenship. However by putting in place a system that requires an individual to obtain the Abkhaz passport in order to enjoy certain rights, the authorities are arbitrarily interfering with those rights.

The ability to cross back and forth across the administrative boundary line is particularly important to returnees because the daily social, economic, and family life of many Gali returnees is on both sides of this line: while they may live in Gali district, they visit close relatives, receive Georgian government social benefits, obtain timely medical care, and in some cases attend school, on the other side of the boundary, often just several kilometers away in the town of Zugdidi.

However, since August 2008 the Abkhaz authorities have restricted returnees’ ability to commute across the boundary by eliminating three of the four “official” crossing points, and by requiring special crossing permits for those who do not possess Abkhaz passports. As a result, many who wish to cross the administrative boundary must first make a circuitous and time-consuming trip to Gali’s administrative center, the town of Gali, to obtain a permit. Those who do not have the time or the means to travel to Gali town sometimes resort to crossing unofficially, thereby risking detention, fines, and imprisonment. The restrictions imposed by the Abkhaz authorities are arbitrary and constitute an onerous burden, especially for those who live in rural areas that are close to the boundary yet far from the town of Gali.

Access to Georgian-language education for ethnic Georgians living in Gali district is also restricted. Prior to the conflict in 1990s, Georgian was the language of instruction for almost all schools in Gali district. Since 1995 the Abkhaz authorities have gradually introduced Russian as the main language of instruction, reducing the availability of Georgian language education, especially in upper Gali. Abkhazia’s new education policy has created barriers to education, as the majority of school-age children living in Gali district do not speak Russian. The policy has also affected the quality of education as there are not enough qualified Russian-speaking teachers in the Gali district to teach in Russian. As a result, some parents are moving their children to those schools in the district where the curriculum is still in Georgian. Other students are leaving Gali altogether to continue their education in territory controlled by the Georgian government.

Eleven schools in lower Gali continue to teach in Georgian, but their future status as Georgian-language schools remains uncertain. Teachers and parents worry that as the Abkhaz authorities devote more resources to ensuring Russian as the language of instruction in all schools in Gali, Georgian-language schools will disappear altogether. If that happens, native Georgian-language speakers would not have the same access to education in their mother tongue as Abkhaz and Russian residents of Abkhazia.

Many ethnic Georgians in the Gali district express serious concern about personal security and protection against violent crime. These concerns are an important factor both for those who have returned to Gali and are deciding whether to stay or leave again for uncontested areas of Georgia and for those who are still waiting to decide whether to return to their homes in Gali. Ethnic Georgians from Gali overwhelmingly conveyed to Human Rights Watch a sense of acute vulnerability to theft, kidnapping for ransom, armed robbery, extortion and other crimes. According to the former UN Special Representative on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons, this vulnerability is largely due to the weakness in the rule of law and administration of justice in the area, as well as deep, mutual distrust between the Georgian population and the Abkhaz security forces.

Although Abkhazia is not recognized as an independent state under international law, the Abkhaz authorities nevertheless have obligations under international law to respect human rights. Under international law, all human rights guarantees applicable within the territory of Georgia also apply to Abkhazia, and the de facto authorities in Abkhazia, as a power with effective control, are obligated to respect and protect those guarantees.

Abkhazia’s constitution explicitly guarantees the rights and freedoms provided in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights treaties. Without prejudice to Abkhazia’s status, the authorities in Abkhazia have an obligation to ensure freedom of movement in both directions across the administrative boundary, and non-discrimination, in particular with regard to the issuance of identity documents and the right to education. Since they exercise effective control in Abkhazia, the de facto authorities also bear primary responsibility, and therefore a duty, for ensuring the safety and security of the local residents.

Until UNOMIG’s mandate was terminated in 2009, the UN maintained a human rights office in Abkhazia, which was jointly staffed by the OSCE and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). This office had a protection mandate, including to gather information from victims and witnesses and to follow up on individual complaints. UNOMIG also reported biannually to the Secretary General. Although a relative newcomer to the conflict, the European Union has also become a significant player as the largest donor funding rehabilitation and confidence-building projects. In response to the 2008 conflict, Brussels also deployed an unarmed civilian monitoring mission (EUMM) to Georgia, but its monitors are denied access to Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Although these institutions continue to send high-level visits to Abkhazia, and several UN agencies maintain a field presence in Abkhazia, including the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), currently there is no agency on the ground with a broad human rights monitoring and reporting mandate.

Abkhazia is now moving rapidly to institutionalize its sovereignty, but this cannot come at the cost of the rights of ethnic Georgians. After the forced withdrawal of the UN and OSCE from Abkhazia there are fewer possibilities for monitoring and protection, leaving ethnic Georgians in Gali more vulnerable than ever. The Abkhaz authorities need to act now to recognize and protect the rights of all people in Abkhazia, including ethnic Georgians in Gali district. Failure to do so will at best cause tens of thousands of people to live in a constant state of anxiety and limbo. At worst, it could force large numbers of Abkhazia’s ethnic Georgians to leave their homes forever. Both of these injustices can and should be averted.

Key Recommendations

To the De Facto Authorities in Abkhazia

- Recognize, respect and fulfill the right of persons displaced from Abkhazia to return to their homes in Gali district and elsewhere in the territory under the Abkhaz authorities’ effective control.

- Amend measures on citizenship and identity documentation and eliminate any provisions, such as those that automatically grant citizenship based only on ethnic identity or on residence in Abkhazia during the conflict period, which are discriminatory and incompatible with international human rights law.

- Allow all returnees to the Gali district to freely cross the Administrative Boundary Line in both directions.

- Recognize and respect the right of returnees to use their mother tongue, including in educational institutions.

- Allow independent and impartial monitoring and reporting on human rights situation in Gali district.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research on ethnic Georgian returnees to the Gali district of Abkhazia from June 2009 through March 2011. Several Human Rights Watch researchers carried out in-depth interviews during three research missions to Gali and Zugdidi districts, respectively. Research missions in Abkhazia were conducted from September 28 to October 5, 2009; from March 10 to 15, 2010; and from October 11 to 15, 2010. Research in Zugdidi, a district in uncontested Georgia, adjacent to the administrative boundary line with Abkhazia, was carried out from June 18 to 20, 2009; July 10 to 15, 2009; and December 21 to 24, 2009. Researchers also conducted follow-up desk research through March 2011.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than one hundred residents of the Gali district, including individuals who stayed more or less permanently in the district, individuals who regularly commuted across the administrative boundary, and those who could not return for security and other reasons. Researchers also interviewed civil society representatives in Abkhazia and in uncontested parts of Georgia, and school teachers, students, and medical personnel in Gali district. Human Rights Watch also interviewed representatives and officials of the Abkhaz government, including the prime minister, the minister of foreign affairs, the minister of education, the head of the Gali district administration and his deputy, passport desk officials, a district education department official, and several village administration heads. We also interviewed representatives of foreign governments and non-governmental organizations working in Abkhazia.

Interviews in the Gali district were conducted in Russian by researchers who are native speakers of Russian. Interviews in Zugdidi district were conducted in Georgian by a researcher who is a native speaker of Georgian. Interviews were conducted mostly with each interviewee individually and in private. Human Rights Watch identified interviewees through local civil society groups, as well as by randomly selecting households in Gali district. Human Rights Watch researchers also went to various crossing points at the administrative boundary and spoke to people who were planning or had already crossed it.

At no point in Abkhazia did our researchers encounter interference, direct or indirect, by the Abkhaz authorities.

In almost all instances the names of interviewees have been withheld at their request and out of concern for their security. Pseudonyms have been used instead to protect their identities. To further protect the security of some of the interviewees, we do not identify the location of interviews. All interviews are on file with Human Rights Watch.

Georgian and Abkhaz speakers use different names for the same geographic locations in Abkhazia. This report follows the stylistic practice used by the UN: thus Gali rather than (Abkhaz) Gal, Sukhumi rather than Sukhum, Inguri for Ingur, and so on.

I. Background

Abkhazia, a former Soviet Autonomous Republic in Georgia, is squeezed between the Black Sea and the Caucasus Mountains. It borders the Russian Federation to the north and the Georgian region of Samegrelo to the south east. Its capital is Sukhumi.

Abkhazia has an area of 8,700 square kilometers, an eighth of Georgia’s territory, including nearly half of its coastline. The Inguri River serves as a natural border line between Abkhazia and uncontested Georgian territory and roughly follows the administrative boundary line between the two.

In March 2010, Abkhaz officials put the population of Abkhazia at 215, 557,[1] which is significantly lower than the pre-conflict population of about half a million. However current population data are, and have long been, highly controversial and politicized. The 1989 census was the last to be conducted during the Soviet era, and the last before the outbreak of the conflict. According to that census, the ethnic Abkhaz population of Abkhazia was 93,267, 17.8 percent of the total population of 525,061. The ethnic Georgian population was 239,872, 45.7 percent of the total. Armenians and Russians were the two other most numerous ethnic groups with 14.6 and 14.3 percent of the total, respectively.[2]

Gali is the southernmost district of Abkhazia. Slightly larger than 1,000 square kilometers, it was the largest district by area of pre-conflict Abkhazia.[3] It is a fertile region that was a key supplier of agricultural produce, mostly nuts and citrus, to the rest of Abkhazia. Prior to the 1992-1993 conflict 96 percent of Gali’s 79,688 inhabitants were ethnic Georgian.[4]

1. Declaration of Independence, Conflict

1992-1993 Conflict

As Georgia took steps to separate from the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, Abkhazia also sought greater autonomy from Georgia.[5] Tensions rose between Tbilisi and Sukhumi over the latter’s bid for sovereignty and grew into open hostilities in August 1992. On August 14, 1992 Georgian armed forces entered Gali district officially to rescue thirteen hostages and secure Georgia’s rail lines to Russia.[6] However, the Georgian troops advanced towards Sukhumi and attacked Abkhaz government buildings.[7] After several unsuccessful ceasefire agreements, in September 1993 Abkhaz forces launched a surprise offensive and seized control of almost all of Abkhazia, with the exception of the upper Kodori gorge in the northeastern part of Abkhazia.[8]

As a result of the war, about 8,000 people, Georgian and Abkhaz, died, 18,000 were wounded, and Abkhaz troops gained control of most of Abkhazia.[9] More than 200,000 people, the majority of them ethnic Georgians, were displaced from their homes in Abkhazia. Some spontaneously returned to the Gali district.[10] But most remain displaced to this day. All parties to the conflict committed violations of international human rights and humanitarian law, including indiscriminate attacks and targeted terrorizing of the civilian population.[11]

Ceasefire, Conflict Resolution Mechanisms, and 2008 War

A ceasefire was formally declared in May 1994, when the parties to the conflict signed the Agreement on a Cease-fire and Separation of Forces (also known as the Moscow Agreement). Negotiated under the auspices of the Geneva Peace Process, this agreement led to the deployment of a Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) peacekeeping force, composed entirely of Russian troops, to monitor the ceasefire. The sides also agreed to task the UN Observer Mission to Georgia (UNOMIG) to monitor the conduct of the CIS peacekeeping force.[12]

After the signing of the Moscow Agreement, negotiations between Sukhumi and Tbilisi continued under the Geneva Peace Process. Parallel to this UN process, Russia also pursued independent negotiations with Sukhumi and Tbilisi.[13]

In the following years, negotiations produced no tangible results on the key issues of Abkhazia’s status and returns of displaced persons. In May 1998 Georgian armed paramilitary groups launched a series of attacks in the Gali district against Abkhaz forces. In response, Abkhaz forces drove out not only the attackers, but also thousands of ethnic Georgians who had spontaneously come back to the Gali district following the 1993 conflict. Abkhaz forces looted and burned homes and infrastructure.[14] Many of those who fled in 1998 eventually went back to Gali.[15]

The second major clash occurred in August 2008, during the war between Russia and Georgia over South Ossetia, another breakaway region of Georgia.[16] On August 10, 2008 Abkhaz military forces launched an operation to overtake the upper Kodori gorge, the only part of the pre-1992 Abkhazia not under the control of the Abkhaz authorities.[17] They gained full control of the area within two days. Over 2,000 ethnic Georgians residing in the gorge were forced to leave their homes and remain displaced to this day.[18]

With the August 2008 conflict all existing negotiations and conflict resolution mechanisms collapsed. Furthermore, following its recognition of Abkhazia (see below), Russia vetoed an extension of mandate of the Organization for Security and Co-operation (OSCE) mission in Georgia when it expired in December 2008. Moscow argued that the OSCE should have separate missions in South Ossetia and Georgia.[19] Using a similar argument, in June 2009 Russia vetoed the extension of the mandate of the United Nations Mission in Georgia (UNOMIG), bringing an end to the UN’s 16-year long peacekeeping and broad monitoring role in Abkhazia.[20]

New Geneva Talks

The August 2008 ceasefire which ended the war in South Ossetia also covered Abkhazia.[21] The six-point plan envisaged international discussions on “the modalities of security and stability” in Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[22] The first round of discussions took place on October 15, 2008 in Geneva and since then subsequent rounds have been held periodically. The Geneva talks involve delegations from Georgia, the United States, Russia, and the de facto authorities of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. They are held under the auspices of the United Nations, the European Union and the OSCE. The negotiations consist of two working groups that meet in parallel in Geneva. One group covers security and stability in the region; the other covers humanitarian issues and primarily deals with the problem of displaced persons and refugees.[23]

The Geneva discussions often appear stalled. However, following the end of the UN’s mandate in Abkhazia in 2009, they are the only international forum in which all parties currently engage.[24] During a February 2009 meeting the parties reached an important agreement to set up joint incident prevention and response mechanisms (IPRM), which aims to “ensure a timely and adequate response to the security situation, including incidents and their investigation, security of vital installations and infrastructure, responding to criminal activities, ensuring effective delivery of humanitarian aid, and any other issues which could affect stability and security, with a particular focus on incident prevention and response.”[25] IPRM is the only on-the-ground process that brings all the sides together to exchange information on local incidents, criminal cases, and human rights violations. It meets in Gali on a regular basis.[26]

2. Returns of Displaced Persons

As noted above, almost all of Abkhazia’s pre-conflict ethnic Georgian population was forced to leave in 1993. The Abkhaz authorities have allowed some to return to the Gali district, but not to other parts of Abkhazia.[27] The Abkhaz and Georgian sides dispute the numbers of returnees and the very definition of the word “returnee.” The Georgian authorities consider almost all ethnic Georgians in the Gali district as internally displaced even if they currently live in Gali because their return was not organized in dignity and safety, whereas the Abkhaz side regards as returnees everyone who went back to the Gali district.[28]

According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), citing the Georgian Ministry for Refugees and Accommodation, by the end of 2009 there were officially 212,113 ethnic Georgian displaced persons from Abkhazia.[29] But this figure includes those who spontaneously returned to the Gali district.[30] Abkhaz officials say the number of displaced is around 150,000.[31]

The right of return has been a key element of all efforts to end the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict. Since July 1993, the UN Security Council has passed 32 resolutions reiterating the right of all displaced people to return to Abkhazia. The UN Security Council has urged the parties to “commit to fulfill, within a reliable timeframe, the conditions necessary for the safe, dignified and swift return of refugees and internally displaced persons.”[32] On May 15, 2008 the UN General Assembly adopted a non-binding resolution recognizing the right of all displaced persons to return to Abkhazia, and their property rights and calling for the “rapid development of a timetable to ensure the prompt voluntary return of all refugees and internally displaced persons to their homes.”[33]

In April 1994 the parties signed an agreement establishing a quadripartite commission to implement the return of displaced people, assess damage to property, and start repatriation of the displaced to Gali district.[34] The agreement underlined the right of all refugees and displaced persons to return to their places of previous permanent residence.[35] It barred individuals from returning “where there is serious evidence that they have committed war crimes and crimes against humanity as defined in international instruments and international practice as well as serious non-political crimes committed in the context of the conflict.”[36] The agreement also excluded any persons, “who have previously taken part in the hostilities and are currently serving in armed formations preparing to fight in Abkhazia.”[37]

The process of organized return under the auspices of UNHCR lasted less than a year and assisted in the resettlement of only 311 persons to Gali district.[38] However, the spontaneous return of Gali residents continued until May 1998 when, as noted above, renewed violence forced between 30,000 and 40,000 people to flee a second time, destroying infrastructure and about 1,500 homes, including many of those recently rehabilitated with donor assistance.[39]

In early 1999 the Abkhaz authorities launched a unilateral initiative to implement returns to Gali district.[40] Many families soon went back, initially commuting daily across the ceasefire line and migrating seasonally to tend their fields and look after the remains of their houses.

In September 2010 the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on the human rights of internally displaced persons, Walter Kälin, visited Georgia and its breakaway regions, including the Gali district. He released his report to the UN Human Rights Council in December. While he noted an improvement in security for returnees to Abkhazia, he remarked that their “return prospects remain disappointingly low.” He attributed this to “the absence of political solutions to conflicts.”[41]

3. Current Landscape

Abkhazia’s Relations with Russia

Russia strongly supported Abkhazia during the secessionist war with Georgia. Moscow and Sukhumi continue to enjoy close ties. As Georgian-Russian relations deteriorated in the years leading up to the 2008 August war over South Ossetia, Moscow increased its support to Abkhazia. The support further intensified after Kosovo’s declaration of independence in February 2008.[42] The ties became even closer after the August 2008 war in South Ossetia and Russia’s formal recognition of Georgia’s breakaway regions.

On August 25, 2008 both chambers of the Russian Federal Assembly unanimously adopted resolutions supporting the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and recommended that the executive branch recognize both entities.[43] The following day Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed a Decree on Recognition of the Independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[44] Tbilisi condemned the move as an annexation of its territories and, in response, broke diplomatic ties with Russia.[45]

On September 17, 2008 Russia and Abkhazia concluded an Agreement on Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance.[46]

Russia moved to establish closer ties with Abkhazia, appointed an ambassador in October 2008, and opened an embassy in Sukhumi in May 2009.[47] In April 2009 Moscow signed a five-year agreement with Abkhazia to take formal control of its frontiers with uncontested Georgian territory.[48] As noted above, Russia vetoed the extension of the mandates of the OSCE and UN missions in Georgia in December 2008 and June 2009 respectively.

Russian-Abkhaz military relations were further strengthened on February 17, 2010 when the two sides signed an agreement allowing Moscow to establish a military base in Abkhazia for 49 years.[49] Moscow also has plans to house a naval base in the port of Ochamchire, close to the ceasefire line, and open air traffic communication between Russia and the breakaway region.[50] An agreement between Russia and Abkhazia regarding the latter was signed on February 17, 2010.[51]

The majority of Abkhazia’s population holds Russian passports.[52] In 2000 the Russian government began proactively to offer residents of South Ossetia and Abkhazia Russian citizenship and to facilitate their acquisition of Russian passports for foreign travel. Some estimates suggest that by 2006 more than 80 percent of Abkhazia’s population had received Russian passports.[53] While Russia imposed a visa regime on Georgian nationals in 2000, Abkhaz holders of Russian passports have been able to cross freely into Russia and benefit in some cases from Russian pensions and other social benefits.[54] The Russian ruble is Abkhazia’s official currency.

Abkhazia’s Political and Economic Landscape

Abkhazia is led by a president elected for a five-year term and has a parliament consisting of 35 members who are each elected from a single electoral district. The last presidential election in Abkhazia was held on December 12, 2009. The incumbent President, Sergei Bagapsh, was re-elected with 61 percent of vote.[55] The most recent parliamentary elections were held in March 2007.[56] Although much of Abkhazia’s pre-war ethnic Georgian population, most of whom live in uncontested areas of Georgia, was disenfranchised from those elections, returnees to Gali played a decisive role in Bagapsh’s first election.[57] Neither Tbilisi nor the international community recognized the elections in Abkhazia, citing, amongst other things, a lack of participation by displaced ethnic Georgians.[58] Bagapsh passed away on May 29, 2011, and early presidential elections are scheduled for August 26.[59]

Abkhazia is largely rural. Many residents cultivate tea, tobacco, citrus, and hazelnuts for commercial trade. Many are also engaged in subsistence farming. The economy is largely dependent on Russian assistance.[60] In March 2010 Moscow and Sukhumi agreed on a complex plan for the socio-economic development of Abkhazia, with Russia committing to provide 10.9 billion rubles (about US$ 375 million) of support to Abkhazia in 2010-2012.[61]

Local authorities hope to develop the tourism industry taking advantage of Abkhazia’s popularity as a tourist destination in Soviet times. Abkhaz officials believe the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics will benefit the regional economy.[62] Sukhumi expects to supply raw material for construction and to provide some infrastructure for the event, including the possible re-opening of the Sukhumi and Gudauta airports and the rehabilitation of the Sochi-Sukhumi railway.[63]

Abkhazia maintains its own army.[64] Military service is obligatory and the authorities draft conscripts twice a year. Tbilisi often accuses Sukhumi of forcibly recruiting returnees from the Gali district,[65] a claim which the Abkhaz authorities deny.

Young men from Gali district told Human Rights Watch that they either leave the district during the drafting season or pay a bribe of roughly 15,000 rubles (about US$ 500) each season.[66] The prospect of conscription into Abkhaz forces is one factor that affects ethnic Georgians’ decisions about whether to return permanently to Gali or remain displaced elsewhere in Georgia. The mother of a 21-year old young man, Maia M., told Human Rights Watch that the fear of conscription prevents her son from travelling to Gali. She also shared stories of other draftees in the village:

My son can’t come here as we are afraid he might be drafted to the military. In order to avoid getting drafted we pay $300 per season [$600 a year] to an acquaintance in the enlistment office. We also give some wine and nuts… There were five young men drafted in our neighborhood. One of them served the full term without any problems, but his mother is ethnic Abkhaz. The other four had problems. They could not take it long and fled to Georgia.[67]

4. Background on the Gali District

Gali is the southernmost district of Abkhazia. Slightly more than 1,000 square kilometers, it was, as noted above, the largest district by area of pre-conflict Abkhazia. It is a fertile region that was a key supplier of agricultural produce, mostly nuts and citrus, to the rest of Abkhazia.

Prior to the 1992-1993 conflict 96 percent of the province’s roughly 80,000 inhabitants were ethnic Georgian. Currently there are 24 village administrations in Gali district, consisting of approximately 30 villages. The district’s administrative center is the town of Gali, which had a pre-conflict population of almost 16,000.[68] The area south of the town of Gali is known as lower Gali, and areas east and north of the town are known as upper Gali.[69] The terms “lower Gali” and “upper Gali” are nominal, but often used by the local residents.

During the 1992-1993 conflict there was little or no fighting in Gali, but at the end of September 1993 most residents were forced to flee as Abkhaz forces pushed south to the Inguri River after taking Sukhumi. Abkhaz forces nevertheless torched and looted many houses. During renewed violence in Gali in 1998, Abkhaz forces destroyed and deliberately burned hundreds of houses and school buildings. According to the UN Needs Assessment report:

In contrast to the Sukhumi area, and many parts of the Ochamchira district, structures in Gali district were not damaged by bullets, fires or mortar rounds during the war… [A]fter the flight of most of the local population, some buildings were damaged by fire, and many more by looting… [T]he most serious physical damage was done during 1998 events, and in the aftermath, when hundreds and hundreds of homes and school buildings were deliberately burned…followed by another wave of comprehensive looting.[70]

Extensive looting, lack of proper maintenance, and failure to conduct significant rehabilitation and reconstruction work has left Gali district’s physical infrastructure and public utilities in a dilapidated state.[71] In addition, homeowners have been largely unable to afford to rebuild or repair their damaged properties. Thus the living conditions of returnees remain poor with poor housing, limited economic opportunities, and a general lack of public services.

Current Population Data for the Gali District

As noted above, there are no reliable statistics on the current population of Gali district. Population data for Gali and the status of this population are highly disputed and politicized by the parties to the conflict. According to the president’s special representative for the Gali district administration, as many as 47,000 displaced people have returned permanently to the Gali district since 1999 and an additional 5,000 people commute back and forth, although they have registered with Abkhaz authorities as returnees.[72] This figure is much higher than the number the Abkhaz Foreign Ministry provided to Human Rights Watch. According to the Foreign Ministry, as of January 1, 2009 the population of Gali district was 29,177.[73] The discrepancy could be caused by the district’s changed administrative boundaries. Preliminary census results conducted in Abkhazia in February 2011 put Gali district’s population at 30,437 people.[74]

A Georgian government official told Human Rights Watch that about 45,000 displaced persons have spontaneously returned to the Gali district since 1999, with additional seasonal migration of 3,000 to 5,000 people.[75]

The situation is further complicated by the lack of a reliable system to register returnees to the Gali district, regardless of their formal status. There were several stalled attempts by UNHCR, with the support of both Tbilisi and Sukhumi, to count the returnees to the Gali district. In June 2005 both sides endorsed UNHCR’s 2-year-plan to verify the number of returnees and even supported the questionnaire to be used for this exercise.[76] However, the plan never went ahead after Tbilisi made several requests for a postponement.[77] Such an exercise could have ended the dispute over the number of returnees and enabled the donor community to better assess the humanitarian and other needs of returnees on the ground.

Until August 2008 3,000 to 5,000 ethnic Georgian displaced people crossed the administrative boundary daily between the Gali district and uncontested Georgian territory for a variety of economic, family, and security reasons explained below.[78] After the August 2008 war between Russia and Georgia, the Abkhaz authorities imposed new restrictions on crossing the administrative border. For more than a year the Abkhaz authorities closed the border and allowed people to cross only for humanitarian reasons. In 2010 the authorities eased these restrictions. Under current Abkhaz regulations it is possible to cross legally but only through the main Inguri Bridge and only with a special permit which any resident of the Gali district can obtain from the district administration on payment of a small fee of 100 rubles. Abkhaz officials told Human Rights Watch that they want the Georgian returnees to decide where they want to live: “We plan to finish the border consolidation by 2011. Then the people will understand that there’s no return back to Georgia. They will have to decide where they prefer to settle.”[79]

Local Administration

Gali’s administration is headed by Beslan Arshba, who was appointed by President Bagapsh in 2007.[80] The de facto president also maintains a special representative in the district, Ruslan Kishmaria, a former military commander. The district administration has one representative in each of the district’s 30 villages. Their duties include collecting taxes on land, nuts, and other crops, ensuring various utility payments, and overseeing school administrations.[81]

All key posts in the Gali administration are held by ethnic Abkhaz brought in from other districts of Abkhazia, though their support staffs are often ethnic Georgians. While a large majority of the local population in Gali district consists of ethnic Georgians, they are only marginally represented beyond the village levels in the administration, law enforcement, and the judiciary.[82]

The official languages of Gali district administration, including its courts, are Russian and Abkhazian. This puts the Georgian-speaking majority of the population of Gali at a disadvantage when communicating with the administration.

Security and Law Enforcement

Personal security and protection from crime are a constant worry for many ethnic Georgians in Gali district and an important factor when they decide whether to return to the homes or leave them for good for uncontested areas of Georgia.

Ethnic Georgians from Gali conveyed to Human Rights Watch a sense of vulnerability to theft, kidnapping for ransom, armed robbery, extortion, looting, especially during harvest season, and other crime. Because the Gali district is predominantly populated by ethnic Georgians, they are collectively vulnerable to such crimes.[83]

In the absence of a comprehensive peace agreement, the Abkhaz authorities have effective control of the territory of Abkhazia and they therefore bear the primary responsibility for ensuring the safety and security of the local residents, as well as for the protection of their rights.

Human Rights Watch was not in a position to comprehensively examine whether the Abkhaz authorities are failing to fulfill this duty with regard to Gali district. In 2005, a leading UN official noted, however, that guaranteeing returnees’ security and upholding law and order in Gali district has proven difficult. This is largely due to the weak development of the rule of law and administration of justice and deep, mutual mistrust between the Georgian population and Abkhaz security forces.[84]

It is not known whether crime rates in Gali are higher than in other parts of Abkhazia, but several UN reports highlight that violent crime in Gali, including armed robbery, kidnapping for ransom, and theft, and the prevailing culture of impunity “generat[e] a feeling of insecurity among the local population.” [85] Although by 2010 the security situation in Gali district was believed to have improved, returnees are still exposed to risks of violence, and they do not trust the local authorities to effectively investigate such incidents.[86]

An arson attack against six houses inhabited by ethnic Georgian returnees in 2010 in lower Gali illustrates the vulnerability of local residents. The attacks took place on June 6, 2010, several days after the killing of a village official and an Abkhaz customs officer.[87] That day about 100 people, allegedly the relatives of the killed officials, drove from Sukhumi and Gudauta, and burned six houses in the village of Dikhazurga. Human Rights Watch interviewed inhabitants of three of the burnt houses as well as several witnesses to the incident. They said that although security officials witnessed the incident, they did not do anything to prevent it.[88] When Human Rights Watch visited in October 2010, the families were still left destitute as a result of the fire.

In a radio interview, Beslan Arshba, the head of the Gali district administration confirmed that five houses were indeed burned in Dikhazurga. He denied that it was a result of a punitive operation, but acknowledged that the authorities failed to take the situation under control and prevent the arsons. He explained:

There was no punitive operation there. Houses were burned in one village – Dikhazurga. Unidentified people set five houses on fire. We did not manage to control it. There were many people who were angry and we could not have watched everyone… we gave humanitarian assistance to people [who suffered].[89]

Many ethnic Georgians said they do not venture out after dark.[90] Many villages do not have a police force, and in remote rural areas, particularly in lower Gali, the closest police agents can be over a dozen kilometers away. Many crimes are never reported because even when police are accessible, Gali residents are reluctant to turn to them due to a lack of trust. Several residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they fear reporting crimes because at best the perpetrators are detained, but released soon, allegedly after paying bribes, leaving victims vulnerable to retribution.[91]

Human Rights Watch learned of, and also interviewed, ethnic Georgians who chose to leave Gali district for good to live in uncontested parts of Georgia after they became victims of crime, rather than try to seek justice for the crime.[92]

II. Legal Framework

Since Russia’s recognition of Abkhazia in August 2008, Nicaragua, Venezuela, and the Micronesian island of Nauru have followed suit.[93] As a matter of international law Abkhazia is not recognized as a state. Human Rights Watch takes no position on the independence of Abkhazia or the territorial integrity of Georgia. Nevertheless, as the de facto authority exercising power and control over Abkhazia, the Abkhaz administration bears responsibility for ensuring respect for the applicable human rights guarantees enjoyed by the residents in Abkhazia. As the obligations of Georgia under international human rights treaties continue to apply to Abkhazia, the de facto authorities therefore have the obligation to respect and protect those guarantees.

The key document outlining the rights of internally displaced persons is the United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement (the Guiding Principles), which reflect existing international human rights and humanitarian law and restate and clarify the rights of displaced persons.[94] The Guiding Principles, though not binding per se, are based on existing international customary, humanitarian and human rights laws and therefore have universal applicability.[95] Georgia has modeled its domestic legislation relating to displaced persons, at least in part, on the Guiding Principles.[96]

The right of people displaced by war to return to their homes, i.e. the “right of voluntary repatriation” is guaranteed under several international instruments.[97] As the UN Special Representative notes in his 2005 report, the de facto authorities of Abkhazia are responsible for providing not only for the physical security of returnees, but also for protecting civil and political, economic, social and cultural rights of those who choose to go back to their places of permanent residence.[98]

Displaced persons are entitled to the same rights as the population at large.[99] They may additionally have special needs by virtue of their displacement, and competent authorities have a duty to provide for such needs. Returnees to Gali district are Georgian citizens and entitled to enjoy the protection of all guarantees of international humanitarian and human rights law instruments to which Georgia is a party, or that are applicable on the basis of customary international law. These include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights.

The primary duty and responsibility to provide for those rights and liberties lie with the national authorities. [100] However, the Guiding Principles also apply to non-state actors who have effective control over a territory to such an extent that the rights of displaced persons and returnees are affected.[101] The Guiding Principles state that such de facto authorities are obliged to respect the rights of displaced persons concerned, and that the observance of these principles does not prejudice the legal status of the authorities.[102]

In the Georgian context this means that the de facto administration in Abkhazia is responsible for respecting the rights of those people who return in the areas under its effective control. Walter Kälin notes that such protection “must not be limited to securing the survival and physical security of IDPs but also relates to all relevant guarantees, including civil and political as well as economic, social and cultural rights attributed to them [IDPs] by international human rights and humanitarian law.”[103]

For the purpose of responsibility and accountability, international law characterizes the acts of de facto authorities as acts of the state. International law on state responsibility adopted by the International Law Commission in 2001 and approved by the UN General Assembly in 2001 states:

The conduct of a person or group of persons shall be considered an act of a State under international law if the person or group of persons is in fact exercising elements of the governmental authority in the absence or default of the official authorities and in circumstances such as to call for the exercise of those elements of authority.[104]

Therefore, the Abkhaz authorities have an obligation to respect human rights whether or not they are the primary “duty holders.” This point is also emphasized by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) High Commissioner on National Minorities, Knut Vollebaek:

I reiterate that international norms and standards require that any authority exercising jurisdiction over population and territory, even if not recognized by the international community, must respect the human rights of everyone, including those of persons belonging to ethnic communities.[105]

The positive obligation to protect human rights and provide for civil and political liberties is also stressed in the constitution of Abkhazia adopted in 1999. Article 11 of the Constitution reads:

The Republic of Abkhazia shall recognize and guarantee rights and freedoms provided in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenants of economic, social, cultural, civil and political rights, or in the other universally recognized international legal acts.[106]

III. Key Human Rights Issues

1. Citizenship and Identity Documents

In 2005 the Abkhaz parliament enacted a “Law of the Republic of Abkhazia on Citizenship of the Republic of Abkhazia,” which defines who is eligible for Abkhaz citizenship, the procedures to obtain it, and the grounds for refusal. Although laws adopted by the de facto authorities do not have any international legal consequences, as they were adopted by internationally unrecognized authorities, they nevertheless have direct impact on people residing in Abkhazia, including ethnic Georgians.

The Abkhaz administration considers an Abkhaz passport to be proof of Abkhaz citizenship. This document also serves as a gateway to a range of rights, including the right to work in the public sector, to participate in elections and hold public office, and to enjoy property rights. The Abkhaz passport is also necessary to receive a high school diploma and use the simplified procedure to apply for a travel permit to cross the administrative boundary line.

The citizenship measure adopted by the Abkhaz authorities presents two human rights concerns. First, the UN has found that it is discriminatory because it allows ethnic Abkhaz, regardless of their places of residence, to become citizens automatically but creates barriers to non-ethnic Abkhaz who wish to become citizens.[107] Discrimination on ethnic grounds is banned by key international treaties, including by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the European Convention on Human Rights.[108]

The law also allows those who are not ethnic Abkhaz to receive Abkhaz citizenship automatically as long as they were resident in Abkhazia for at least five years at the time of Abkhazia’s declaration of independence in 1999.[109] This second condition excludes almost all ethnic Georgians currently resident in Gali district because they were displaced by the fighting in 1992-1993.

Receiving Abkhaz citizenship and an Abkhaz passport is also possible through a naturalization process, but that requires ethnic Georgian returnees to ‘renounce’ their Georgian citizenship and go through onerous administrative procedures, which include collecting and filing a range of documents, some of which they do not always possess or which need to be translated into Abkhaz or Russian.[110] Moreover as Abkhaz ‘citizenship’ is not recognized under international law, the requirement to renounce Georgian citizenship could render those who have to apply for an Abkhaz passport, in legal limbo without an internationally recognized nationality.[111]

Despite the renunciation requirement and an onerous application process, many returnees to the Gali district apply for Abkhazian passports, because they need to have one in order to enjoy a range of rights and freedoms.

Although the Abkhaz authorities claim that they do not compel anyone to obtain an Abkhaz passport, they do nonetheless make possession of such a passport a prerequisite to enjoying civil and political, as well as social, cultural and economic rights. These include the right to work in the public sector, hold public office, vote in elections, own and transfer property, and use the simplified procedure to apply for a permit to cross the administrative boundary line. By putting in place a system that requires an individual to obtain such a document in order to enjoy certain rights, the authorities are arbitrarily interfering with those rights. If there is a requirement that any formal Abkhaz documents be obtained as a prerequisite to access or enjoy a range of civil and political rights, such documents should be issued to everyone without any discrimination, including on ethnic grounds. Furthermore, the requirement to renounce Georgian citizenship should be eliminated.

On July 31, 2009 the Abkhaz parliament adopted amendments easing the citizenship law’s application to returnees to the Gali district. The amendments considered returnees to Gali as “citizens of Abkhazia” and simplified the process by which they could obtain Abkhaz passports.[112] However, under pressure from the Abkhaz political opposition, President Sergey Bagapsh vetoed the amendments and in August 2009 returned them to the parliament for further consideration.[113]

At that point the Abkhaz authorities suspended the simplified distribution of Abkhaz passports to residents of Gali district. Several estimates suggested that prior to the suspension about 3,500 passports had been issued to Gali residents.[114]

The process of issuing passports to Gali returnees was renewed slowly in late 2010. However, a large majority of Gali residents still do not have Abkhaz passports, although some applied as early as August 2009. Most have Georgian national identification cards or passports, which the Abkhaz authorities do not accept as identity documents. Many have Form 9 documents, an identity document issued by the Abkhaz authorities to returnees in the years prior to August 2008.[115] Prior to 2008, ethnic Georgians could use Form 9 to cross the administrative boundary line, to vote, obtain high school diplomas,and for other civic acts.[116]

It is not clear whether Form 9 documents are still valid. In March 2010 Abkhaz authorities told Human Rights Watch that they continue to be issued and that they can be extended.[117] However several Gali residents told Human Rights Watch that they thought it was no longer issued and the old ones had expired.[118]

Some continue to use their expired Soviet passports, with Gali residency stamps in them, for administrative boundary line crossings.

Obtaining Abkhaz Passports

Article 13 of the citizenship measure establishes the following conditions for “naturalization”: knowledge of the Abkhazian language, citizenship oath to the republic of Abkhazia, possessing knowledge of the main principles of Abkhazia’s constitution, maintaining permanent and continuous residence in Abkhazia for ten years, having a legal income and paying taxes, and renouncing previous citizenship.[119]

Procedures for obtaining Abkhaz passports for ethnic Georgian Gali residents are cumbersome and appear discriminatory. The list of necessary documents includes: Soviet passport or Form 9, birth certificate, marriage certificate, high school and university diplomas, information paper from the regional military commissariat, residence permit, labor record book, passport photos, house and land property registration book, registration certificate confirming the place of residence, certificate of address, passport fee payment confirmation, and an application form submitted in triplicate. All documents must be submitted in Russian or Abkhazian. Many Gali residents have to have their documents translated and notarized in the town of Gali, which adds expense and time to the application process.

One member of the Abkhaz parliament in favor of simplified procedures for issuing passports told Human Rights Watch:

This process has to be simplified at least for the elderly. Their documents have often been burned or lost after the fighting. And it’s not always possible to restore them. In the Gali archives we have documents only from 1940 and onwards. If somebody is born prior to that, he or she will have to go to Sukhumi to restore it. How can one go to Sukhumi? On what money? This creates problems for elderly people who don’t have all the necessary documents.[120]

Once the necessary documents are submitted to the passport desk in the Gali administration, they are forwarded to the national security service of Abkhazia for approval.[121] A Gali passport service official told Human Rights Watch that the security service vets applicants for suspicious activities or connections, especially during the 1992-1993 conflict.[122] Once these checks are completed, the authorities issue a document proving that the individual has filed an application for an Abkhaz passport.

Even when Gali residents voluntarily apply for citizenship and a passport, they often face difficulties gathering the necessary documentation. Tamar T., told Human Rights Watch:

Many have serious problems with Abkhaz passports. They can’t get all the necessary documents. Several teachers have this problem at my school. We have to go through terrible bureaucracy to apply for an Abkhaz passport.[123]

Maia M., a resident of Chuburkhinji village, told Human Rights Watch that she had problems submitting an application for an Abkhaz passport for her daughter because she had not graduated from a high school in the Gali district. She had sent her daughter to school Zugdidi in 2004 after the schools in Chuburkhinji switched from Georgian to Russian-language instruction:

My daughter graduated from school in Zugdidi in 2009. She was coming home every weekend. And now for her to continue commuting back and forth I wanted to apply for an Abkhaz passport for her. However, in the administration I was told that she will have problems getting it, as she did not graduate from a school here. I don’t know what to do.”[124]

Documentation appears to be a problem if a returnee marries a person from the other side of the administrative boundary line. Another Chuburkhinji resident told Human Rights Watch, “My neighbor married a woman from Zugdidi. They are married for 10 years now, but she can’t get any documents here. She can’t even apply for Abkhaz passport.”[125]

The Rule on Renunciation

Article 6 of the citizenship law allows dual citizenship only to persons of Abkhaz ethnicity, while all others “have the right to obtain citizenship of the Russian Federation only” as their second citizenship.[126] This provision is clearly intended to deny ethnic Georgians in the Gali district the right to retain their Georgian citizenship when acquiring Abkhaz passports. While in practice, the authorities do not confiscate Georgian passports or identity documents, the requirement to renounce one’s citizenship, even nominally, creates additional anxiety for the local population.[127] They fear unknown consequences should the Abkhaz authorities discover their Georgian identity papers.

Gali residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that while applying for Abkhaz passports they had to write on the application that they voluntarily renounce their Georgian citizenship in exchange for Abkhaz citizenship. Anna A., a 20-year-old resident of Gali town, filed her application for an Abkhaz passport in May 2009. She told Human Rights Watch:

I had to submit copies of my Form 9, high school diploma, residency document, and proof of payment, and some other docs... They also took my fingerprints and asked me to write on the application that I voluntarily refuse Georgian citizenship in exchange for Abkhaz.[128]

Nineteen-year-old Giga G., a resident of lower Gali, told Human Rights Watch that he leaves his Georgian identity card in Zugdidi before he crosses the administrative border because he fears Abkhaz border officials will confiscate or tear it up if they find it.[129]

Citizenship and Other Rights

Only citizens of Abkhazia are officially entitled to certain civil and political, as well as some social and economic rights. An Abkhaz passport is a required document for jobs in the public sector, including for teachers and medical personnel.

Ruslan Kishmaria, the president’s special representative in Gali district, told Human Rights Watch:

People of course can continue to live here without passports. And can even work, for example, in their back yard. But why do I need him or her in a public [sector] job, when there are others with Abkhaz passports? If he refuses to take our passport, what kind of a friend and a brother-in-arms would he be? Let him live here, but for us he will be a social outcast.[130]

Sergey Shamba, prime minister of the de facto government, reiterated the point in an interview with Human Rights Watch. He said: “[Jobs in] educational institutions should go to citizens of our country.”[131] Shamba also stressed that no one had been fired from schools for not having an Abkhaz passport. However, several teachers told Human Rights Watch that the Gali district education department instructed them to apply for Abkhaz passports if they wanted to keep their jobs.[132]

Ketino K., a school teacher in the Gali district, told Human Rights Watch that the headmaster in her school was warned in early 2009 that teachers without Abkhaz passports will not be able to receive their salaries. “Although this has not been implemented so far, most of us were scared and applied for the Abkhaz passport,” she said.[133] Tamar T., a 55-year-old teacher from Gali told a similar story. “If you want to work and live here you need to get the passport,” Tamar said. “The administration explained this clearly at a gathering in Gali [town].”[134]

In an interview with Human Rights Watch the deputy head of the education department in the Gali district, Jamalia Charkazia, denied that this was the case, but nonetheless justified such a policy, saying, “If you don’t want to be a citizen of this country, don’t want to participate in elections then maybe you should not be teaching in a state institution.”[135]

At least one school was instructed to provide a list of teachers who applied for Abkhaz passports and the reasons why anyone had not done so. A teacher in a lower Gali district school described what happened to Human Rights Watch:

The head of the district administration requested everyone to apply by September 20 [2009]. We need to collect a lot of documents to apply. Three times we hired a mini bus to go to Gali town to submit documents… Now following their instructions, we have prepared this list of staff who applied, and if someone had not applied, what were the reasons.[136]

A teacher in a lower Gali school who was instructed to apply for an Abkhaz passport if she wanted to keep her job told Human Rights Watch that she did not want to sign a document renouncing her Georgian citizenship, but when she refused an administration official signed on her behalf:

To get this [Abkhaz] passport . . . you need to write with your own hand: ‘I renounce Georgian citizenship,’ and sign it. I did not sign it. I thought it was unfair. But those at the passport desk signed it instead of me.[137]

The same teacher had problems because her university diploma was from another part of Georgia, not Abkhazia:

When I handed in documents for a new passport, I gave them my Georgian diploma. They told me that they did not need it and it was not right. Of course, I don’t have a different one. How could I? So I gave the man 100 rubles (US$ 3.5) and he accepted my application anyway.[138]

Another teacher from a lower Gali district school, Zinaida Z., refused to write and sign a renunciation statement, and as a result her documents were never accepted for the Abkhaz passport. Later she decided to leave Abkhazia altogether.[139]

A young man working for an international relief agency in Gali town told Human Rights Watch:

If you want to live and work there, you should get it [an Abkhaz passport]. You can’t do anything without a passport. Everyone living there should have one. Without the Abkhaz passport you can’t buy, sell or transfer your property.[140]

Amiran A., a resident of Zemo Bagrebi village in the Gali district, complained to Human Rights Watch that in order for him to keep his land, he had to register it, and to register, he had to obtain an Abkhaz passport, which required documents that he did not possess:

I have a plot of land here. In the Gali administration they say that I need to register the plot in my name in order to keep it, but in order to register it I have to have the Abkhaz passport. I would have applied for it, but I don’t have the required documents; I don’t even have Form 9. I don’t know what to do.[141]

41-year-old Inga I. told a similar story. Her parents had a house in Gali town, but once they died she could not inherit the property or pass it on to her children without first obtaining an Abkhaz passport:

I met a notary public in Gali who told me that I can’t do anything with my property unless I get an Abkhaz passport. I don’t want it, because I will have to write in the application that I refuse my Georgian citizenship, which I don’t want to do.[142]

A 40-year-old, resident of Gali town, Tsiala Ts., had a similar problem. She could not transfer property to her children after her parents died, without first getting the Abkhaz passport.[143]

2. Freedom of Movement

The freedom to cross the administrative boundary line, which roughly follows the Inguri River bed between the Gali district and uncontested areas of Georgia, is particularly important to returnees because their daily social, economic, and family life is, in many cases, on both sides of the boundary. Often these ties are in Zugdidi, a city just a few kilometers from the administrative boundary line. But since August 2008 the de facto Abkhaz authorities have restricted returnees’ ability to commute across this line.

Frequent trips across the boundary are necessary for a number of reasons. First, returnees to Gali frequently cross to collect Georgian government allowances for displaced persons, which are paid only on the Georgian-controlled side of the Inguri River. Second, many displaced persons told Human Rights Watch that while the security situation in the Gali district improved somewhat in the past year or so, they do not feel safe living there permanently. Many therefore preferred to live permanently elsewhere in Georgia but to return to Gali temporarily to tend to their fields and take care of their property there.[144] Third, Gali residents maintain close family ties with relatives in Zugdidi and other parts of uncontested Georgian territory. Some families are divided across the administrative border, particularly those with school-age children and who fear enforced Russian-language education policies.[145] High-school graduates also often leave Gali district to continue their higher education in Georgian-controlled territory. As noted above, young men of conscription age also often stay away from Gali district during the conscription season in order to avoid being drafted by the Abkhaz authorities. Finally, because road conditions that connect parts of lower Gali to the town of Gali are often poor, many residents of those areas prefer to go to Zugdidi than to Gali town if they need to make a trip to town.

The right to freedom of movement is enshrined in the ICCPR and the European Convention on Human Rights.[146] The UN Human Rights Committee, the treaty body that monitors states’ compliance with the ICCPR, has said that freedom of movement is “an indispensable condition for the free development of a person.”[147] While freedom of movement is not an absolute right and the de facto authorities can impose some limitations for security and other considerations, current restrictions appear arbitrary and constitute an onerous burden on individuals, unjustifiably interfering with their right to freedom of movement.

For more than a year following the August 2008 conflict, the administrative boundary was officially closed, and crossing was permitted only for humanitarian purposes.[148] Although the boundary is no longer closed, there is currently only one crossing—over the Inguri Bridge—and each time Gali residents wish to cross they must obtain a special permit in the town of Gali. This requirement is especially burdensome for residents of lower Gali, which is close to the administrative border. They have to make a circuitous, time-consuming trip to the town of Gali to get a permit. Those who can afford neither the time nor the expense of traveling to the town of Gali resort to crossing the border unofficially. Crossing without a permit or in locations other than the Inguri Bridge is considered illegal and punishable by incremental fines and even imprisonment.

Many residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch consider their ability to commute across the administrative border essential if they are to remain permanently in Gali. Several of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch expressed fear that after the Russian Border Guard Service takes full control over the administrative border they might be forced to decide definitively whether to stay in Abkhazia for good or to leave. Understandably, for the reasons already outlined, most prefer to maintain the option of travelling freely between their homes in Abkhazia and Georgian-controlled territory. Further restrictions on freedom of movement across the administrative boundary are likely to lead to a new wave of displacement. As noted by Temur T., a resident of Tageloni village in lower Gali, “If people cannot go back and forth normally, then they won’t have any other options left but to go to the other side for good.”[149]

Pre-2008 Crossing and Post-2008 Consolidation of the Administrative Border

Thousands of people used to commute across the ceasefire line, often daily, in order to collect social assistance provided by the Georgian government or to maintain ties with their families, or both. In interviews with Human Rights Watch many expressed anxiety about no longer being able to cross the line. For example, Maia M., a 40-year-old resident of Chuburkhinji village told Human Rights Watch that she commuted frequently over the Inguri River. “I have parents and a brother there [in Zugdidi],” she said. “They have not been here since 1993. They are afraid. If the border is closed how can I visit them? All of us have relatives there. How can we keep in touch?”[150]

Rusudan R., a 63-year-old resident of Chuburkhinji, who until 2008 also commuted frequently, told Human Rights Watch that she needs to commute for medical treatment and to buy medications. “We don’t have anything here – neither medications, nor doctors,” she said. “If we need anything, we go to Zugdidi. We can’t survive otherwise.”[151] Tamar T., a 55-year-old resident of Gali, faces similar problems. “I am a diabetic and depend on insulin,” she said. “I need to have four injections a day. I can buy insulin only in Zugdidi. Therefore, my ability to cross over the bridge is a life and death issue.”[152]

Until August 2008 there were four or five official crossing points over the Inguri River and about a dozen unofficial ones, particularly when the river’s water level was low. Rules for crossing the administrative border, though arbitrarily applied, were more relaxed. Returnees could use a variety of documents to cross the Inguri River, including Form 9, old Soviet passports with a Gali residency stamp, birth certificates with Gali as a place of birth, student identification cards, teacher certificates, and healthcare system employee IDs. Many of those interviewed told Human Rights Watch that crossing the administrative boundary was usually easy as long as they had one of those documents and paid a small “fee” as a bribe. However, they also complained that crossing the border depended on the mood of Abkhaz border guards. In some cases border guards would refuse to let them cross without providing any explanation, even if all documents were in order.[153]

Following the August 2008 conflict the Abkhaz authorities imposed severe restrictions on all movement across the administrative boundary line, which was officially closed for over a year and a half.[154] Crossing was allowed from the Gali side only for those who had Abkhaz passports or Soviet passports with Gali residency stamps. [155] Those who did not hold these passports needed to obtain crossing permits, which the Gali administration would issue only on humanitarian or other exceptional grounds. Students who studied in Zugdidi and people requiring emergency medical intervention were among the categories of those to whom the authorities would issue permits.[156] Crossing was also allowed in special circumstances, such as weddings, funerals, and family reunions. Crossings were only allowed at the main Inguri Bridge crossing, which is near Chuburkhinji.

As the Russian military consolidated the administrative boundary line towards the end of 2010, the Abkhaz authorities relaxed the crossing procedures. The Inguri Bridge remains the only legal crossing point, but residents no longer need to present grounds justifying their need to cross. Whilst this has meant that the process of obtaining a permit is more straightforward, nonetheless it remains excessively burdensome. The very existence of the border controls at the administrative boundary line, and the fact that there is only one legal crossing point, impede the exercise of protected fundamental rights. Abkhaz officials have said that these are temporary measures put in place while Russian border guards take over the administrative border and that when this process is complete there will be five official crossing points.[157]

Crossing the administrative boundary without a special permit or anywhere other than at the Inguri Bridge is considered unauthorized border crossing and is punishable under Abkhaz law. Articles 190 and 1901 of the Administrative Code of Abkhazia set out a fine of up to 10 minimal monthly wages for illegal border crossing.[158] Repeated offense of illegal border crossing can also lead to criminal prosecution with sanctions of fines from 30,000 to 60,000 rubles (approximately US$ 1000 to US$2000) or two years of imprisonment.[159]

Obtaining a Crossing Permit

The Gali district administration requires one permit for each crossing of the administrative boundary line at the Inguri Bridge. In order to obtain a permit, residents need to present Form 9, an Abkhaz passport, or a statement attesting that that they have filed documents for Abkhaz citizenship, and pay a 100 ruble (US$ 3.5) fee. Permits are issued on the spot, without a waiting period. Permits are valid for one round-trip border crossing and must be used within one month of issue. The Abkhaz administration does not issue multiple-crossing permits so each crossing requires a new application and a new permit.

It is particularly burdensome for residents of lower Gali district, who live along the Inguri River, to apply for permits each time they need to cross the administrative boundary line. Until August 2008 they could easily cross over the river at a variety of locations by bus or even by foot. Now, however, they must make the trip to the town of Gali in order to obtain a special permit. This makes any trip across the border more expensive and time-consuming, especially given the poor state of rural roads. For example, the 28 kilometer drive from Pirveli Otobaia, a village about 1.5 kilometers from the administrative boundary line, to the town of Gali takes about two hours in good weather. When the road is muddy it can be nearly impassable.[160] Kote K., a resident of the lower Gali district village of Kvemo Bargebi, told Human Rights Watch his village is only a 15-minute drive to the administrative boundary line, but that the drive to the town of Gali for a permit takes an additional two hours and involves additional costs, which many cannot afford.[161]

A similar frustration was shared by a 60-year-old resident of Nabakevi village, Mzevinar M.

She told Human Rights Watch:

I try to use bypass roads instead of going through the main bridge. If Russians catch you they take you to Gali [town], where Abkhaz take a lot of money from you. They call it a fine. The central bridge, where Abkhaz guards stand, is far from here. That’s why I use the bypass roads, but every time I do so, I’m afraid of being caught.[162]

Impact of Crossing Restrictions

Crossing restrictions can be particularly onerous for people who have medical needs and require frequent trips to the other side of the administrative boundary line. Medical facilities are more developed in Zugdidi than in the Gali district. Furthermore, it is much easier for a lower Gali resident to access Zugdidi than the town of Gali. Therefore, those who have returned to their homes in Gali often seek medical assistance on the other side of the administrative boundary line. Tamar T., who suffers from diabetes, told Human Rights Watch that it is difficult for her to get a permit every time she needs to go to Zugdidi to buy her medications. She tried, but failed, to convince the Abkhaz authorities to issue her a multiple-crossing permit. She has to sneak through unofficial crossing places or bribe her way through the Abkhaz security in order to cross without a permit.

One resident of a border village who urgently needed to cross the administrative boundary line to seek medical assistance for her sick child tried but failed to cross without a permit. She explained to Human Rights Watch that she did not have time to make a trip to Gali town to request such a permit and unsuccessfully tried to convince the border guards to let her and the child through:

My daughter had a fever. You know this was a period of swine flu scare. I got frightened and wanted to take her to Zugdidi. No matter how much I begged the Abkhaz guards at the main bridge, they would not let me through. They told me to take her to the Gali hospital instead. That’s what I had to do in the end.[163]

The problem of obtaining a permit becomes particularly acute when someone needs emergency medical assistance. For example, the Nabakevi hospital in the Gali district is some hundred meters from the administrative border and only 15 kilometers from Zugdidi. Nabakevi hospital staff often direct people in need of emergency medical assistance to Zugdidi. However the new border crossing restrictions make it more difficult for medical personnel to do this. A doctor in a village close to the administrative boundary line told Human Rights Watch that she got in trouble after sending a wounded patient to Zugdidi:

I was summoned to the investigative department in Gali and the head of the department started screaming at me: ‘Who gave you the right to send the patients to Zugdidi? You do this all the time. Why do you do this? Why didn’t you bring him to Gali [town hospital]? We’ll fire you.’ I am a doctor, I had to help the patient and what do I get in return? I got screamed at.[164]