“You’ll Be Fired if You Refuse”

Labor Abuses in Zambia’s Chinese State-owned Copper Mines

Map of Zambia

© Human Rights Watch

Summary

Over the past decade, China has rapidly increased its investment throughout Africa. But while many commentaries have examined the ambivalent relationship between China and Africa, few have systematically examined what Chinese investment means in human rights terms, particularly for Africans employed by China’s state-owned companies. By investigating the specific practices of particular Chinese employers, the conditions of a given set of workers, and the enforcement of labor laws by a particular African government, it is possible to begin to paint a picture of China’s broader role in Africa. To this end, this report examines the labor practices of Chinese state-owned companies in Zambia, a landlocked country in southern Africa, focusing on the country’s long-thriving copper mining industry and its well-established organized labor.

Based on three research missions to Zambia, it draws on more than 170 interviews, including with 95 mine workers from the country’s four Chinese copper operations, 48 mine workers from other multinational copper mining operations, management representatives from Chinese-run mines, mining union officials, government representatives, police, medical professionals, journalists, and foreign diplomats. The report examines primarily how practices in the Chinese-run copper mines compare to relevant domestic and international labor and human rights standards, as well as how they compare to those of other copper mining companies in Zambia.

Human Rights Watch found that while Zambians working in the country’s Chinese-run copper mines welcome the substantial investment and job creation, they suffer from abusive employment conditions that fail to meet domestic and international standards and fall short of practices among the copper mining industry elsewhere in Zambia. Miners at several Chinese-run companies spoke of poor health and safety standards, including poor ventilation that can lead to serious lung diseases, hours of work in excess of Zambian law, the failure to replace workers’ personal protective equipment that is damaged while at work, and the threat of being fired should workers refuse to work in unsafe places. Injuries and negative health consequences are not uncommon, although many incidents are not reported to the government, contrary to Zambian and international labor law. The troubling situation stems largely from the attitude of Chinese-owned and run companies in Zambia, which have tended to treat safety and health measures as trivial.

Efforts to address these and other issues of concern to workers—particularly pay, which is higher than Zambia’s monthly minimum wage but much lower than that paid by other international copper mining firms—is hampered by the curtailment of union activity: several Chinese operations suppress workers’ right to join the labor union of their choice and retaliate against outspoken union representatives.

Incidents reported to Human Rights Watch strongly suggest that regulations are considered more of an imposition than an important component of a well-run copper mining operation. Indeed, China’s state-owned enterprises in Zambia’s copper mines appear to be exporting abuses along with investment, with some issues in Zambia strikingly similar to safety and labor problems that plague China’s domestic mining industry.

Primary responsibility for ensuring that Zambia’s copper mines operate in accordance with international standards rests with the Zambian government, which has largely failed to enforce the country’s labor laws and mining regulations. In the September 20, 2011, presidential election, Michael Sata, an opposition politician known for criticizing Chinese company labor practices, defeated incumbent President Rupiah Banda. Sata’s stated commitments to protect workers’ rights are encouraging. But simply demanding that Chinese companies improve their practices is insufficient if not accompanied by more effective regulation of the mines. Above all, this requires addressing inadequacies in the Mines Safety Department—which is understaffed, under-resourced, and faces allegations of corruption—and boosting fines for breaching safety regulations and labor laws that are currently so small they offer little deterrent effect.

History of Zambia’s Copper Industry

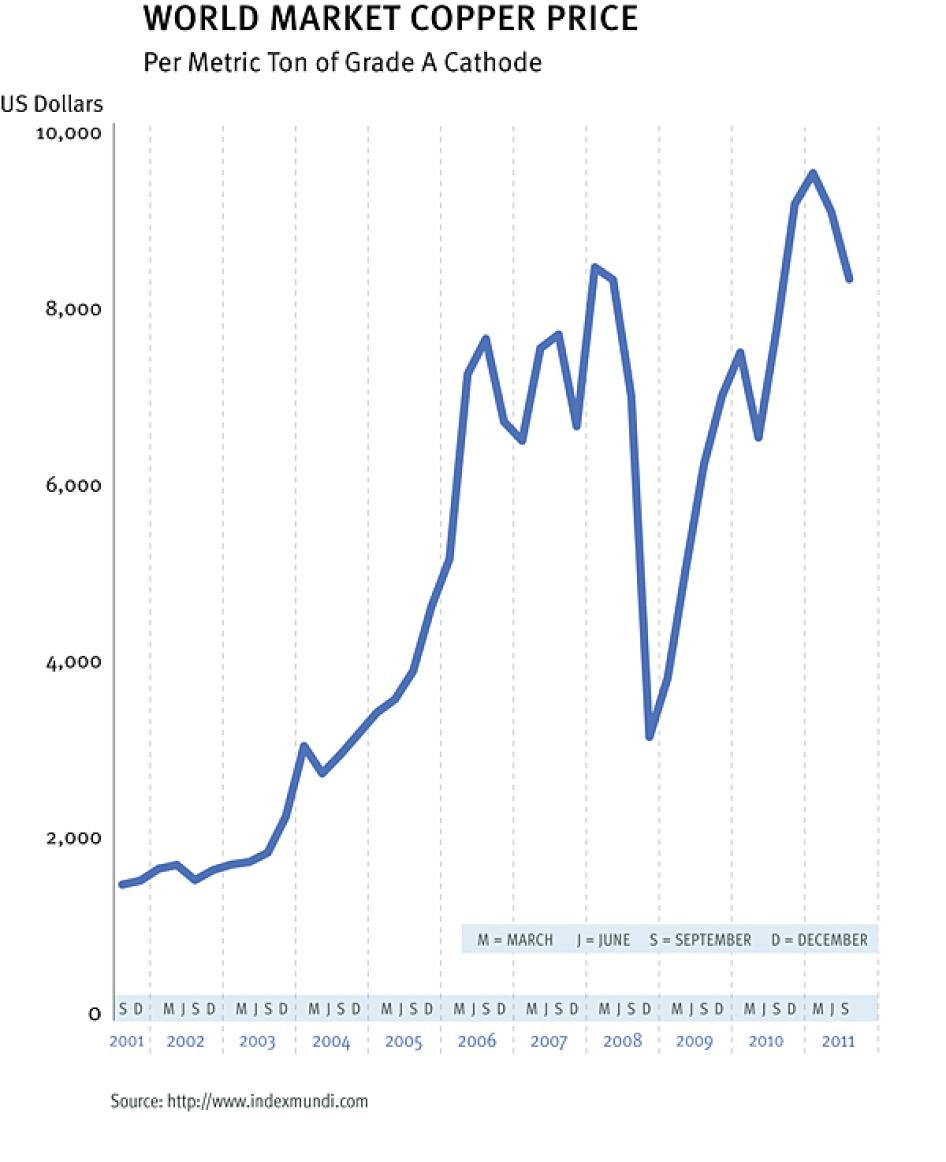

Dating back to 1928, when the country was the British colony of Northern Rhodesia, copper mining—particularly along the Zambian-Congolese “Copperbelt” border—has long been essential to the country’s economic development. Times are good at the moment, with record high copper prices in late 2010 and 2011: on July 1, 2011, the World Bank declared that Zambia had moved back up from low to low-middle income status.

There is a proud mining culture in the country, where copper mining extends back generations in families, and many miners attend trade schools to learn the mining craft. There is also a strong union tradition, with the Mineworkers Union of Zambia (MUZ) and the National Union of Miners and Allied Workers (NUMAW) representing more than 50,000 miners throughout the industry. Finally, there is a detailed and robust set of mining regulations, safety standards, and labor laws that, at least on paper, control every aspect of the industry and generally conform to International Labor Organization standards.

Chinese-run Copper Mining Companies

In 1997, after decades of control by Zambian state-owned enterprises, or “parastatals,” the government sold the copper mines to private investors. Two decades of falling copper prices and low capital investment had left the industry a shell of its lucrative past. Copperbelt towns today look like 1960s models that have aged with difficulty and never been updated, with buildings from that era’s boom times now shuttered or dilapidated and tennis courts and cricket fields once provided and maintained by the Zambian parastatals now overgrown with weeds.

Right after privatization, China entered the Zambian copper mining industry, along with competitors from India, South Africa, Switzerland, and Canada. In 1998, China Non-Ferrous Metals Mining Corporation (CNMC) purchased the copper mine in Chambishi for Non-Ferrous China Africa (NFCA); some US$132 million later, the mine reopened for production in 2003 after being dormant for 13 years. CNMC is overseen by China’s State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), a body that controls state-owned enterprises under the government’s State Council—the country’s highest executive authority in charge of the state’s administration. CNMC therefore has direct links to the Beijing government.

Since 2003, CNMC has opened three mining operations in Zambia in addition to NFCA: Sino Metals Leach Zambia (Sino Metals), a copper processing plant; Chambishi Copper Smelter (CCS), a copper smelting plant; and China Luanshya Mine (CLM), an underground and open-cast mining operation. The four employers currently provide around 6,000 jobs and are undertaking substantial expansion, with several thousand more jobs expected to be filled in the next few years. Mine shafts have been upgraded with modern equipment, the smelter is deemed state-of the-art, and computers have replaced pencils in planning.

Labor Abuses

Miners in these companies who spoke to Human Rights Watch repeatedly expressed gratitude to the Chinese investors for their jobs and the enormous investment being made. Yet each measure of praise was invariably followed by a string of complaints about working conditions. Copper production carries serious health and safety risks from mining through processing and smelting. Underground copper mining is particularly dangerous, with at least 15 recorded fatalities in Zambia every year since 2001. While accidents are not unique to Chinese-run mines, nearly all the Zambian workers and union officials who spoke to Human Rights Watch said the Chinese copper operations were the country’s worst when it comes to health and safety.

Miners at several Chinese-run companies told Human Rights Watch that they often risk their health working under demanding conditions for lengths of time that extend beyond what is permissible under Zambian law, or risk being fired. Some reported spending virtually an entire week handling acid and inhaling noxious fumes and dust. Most miners at Sino Metals and CCS reportedly work 12-hour shifts, compared to the eight-hour shifts outlined in Zambian law and standard in every other copper mining and processing operation in the country. Miners in certain departments at Sino Metals work 78-hour weeks without sufficient overtime, while those in other departments work 365 days a year, or have pay docked from already low salaries.

Company safety officers of Zambian nationality described lacking power to halt work in unsafe areas, saying that Chinese managers consistently overruled them. Workers told countless stories of working under the threat of being fired should they refuse to work in areas they reasonably perceived as dangerous. Such threats are not empty: in several instances when workers did stand up to their Chinese boss, they suffered lost pay, “charges” (written warnings) for insubordination, and even termination. Desperate to keep their job in an economy where one is hard to find, most sacrifice safety concerns for employment. And while the Chinese operations provide workers with personal protective equipment (PPE), several of them refuse to replace it even when it is damaged during work.

The result is preventable accidents and health problems. For example, underground miners suffer broken limbs, crushed fingers, and other injuries from rock falls when there is inadequate support in blast sites. In rare cases, miners are crushed and killed by falling rocks, or electrocuted underground by improperly placed cables. At processing and smelting operations, workers suffer acid burns. Across the copper operations, workers develop serious lung disease, including silicosis, due to poor ventilation and constant exposure to dust and chemicals. Workers and union officials say that many accidents are never reported to the government, contrary to Zambian and international labor law, because they believe Chinese managers have adopted a policy of active concealment— not reporting minor injuries by bribing hurt workers as necessary.

At its most extreme, a 2005 explosion at a Chinese-owned explosives manufacturing plant in Chambishi killed 46 Zambian workers; the following year, riots in Chambishi over work conditions culminated in the shooting of at least five miners, allegedly by a Chinese manager.

While at least one union exists at each Chinese-owned copper mine, several companies have barred workers from joining the Mineworkers Union of Zambia (MUZ)—despite clear provisions in Zambian labor law that allow workers to be represented by the union of their choice and a court ruling in MUZ’s favor on the establishment of a branch office at these specific companies. Union representatives at the Chinese-run operations also described prejudicial acts taken against them for union activities, which violate Zambian and international labor law. These include verbal threats to fire an employee, transfer to jobs that are outside a union representative’s training and expertise, and “charges”—which can lead to deductions of monthly pay and even termination of employment—for attending union meetings. Union leaders at several non-Chinese mines also cited problems, indicating a broader failure by the Zambian government to protect union representatives as required under Zambian and international law.

However, on certain issues in recent years, the practices of Chinese-run copper mining companies have improved. Personal protective equipment is now provided to almost all employees working in these mines, though several Chinese-run copper mines continue to not promptly replace it when damaged. Physical abuse by Chinese supervisors appears to have decreased substantially, and is now rare at NFCA and mostly obsolete at other Chinese-run copper operations. Unions are now accepted as a permanent feature of the enterprise. These improvements show the Chinese companies can and do respond to the local environments in which they operate, but it takes committed action from the host government.

Zambian Government’s Responsibilities

The Zambian government appears to have applied little pressure on the Chinese copper mining companies to meet national and international labor standards beyond the flashpoint events that generated broad anti-Chinese sentiment. Miners, journalists, union officials, and others referred to the “special relationship” between Banda’s government and the Chinese government, including the state-owned companies. As a result, while miners who spoke to Human Rights Watch often expressed contempt for the Chinese management, many blame equally the previous Zambian government for its regulatory failures.

Zambia’s Mines Safety Department (MSD) in the Ministry of Mines is supposed to ensure compliance with health and safety regulations. But understaffed, underfunded, and facing allegations of corruption—it provides little effective regulation of mining companies. The Ministry of Labor appears equally weak in protecting those in the copper industry, endorsing collective bargaining agreements that appear inconsistent with Zambian law. President Sata has promised to take action to ensure the improvement of workers’ conditions; he would do well to start by empowering these ministries to rigorously enforce labor standards across the copper mining industry, not just in the Chinese-run mines.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) has promulgated several conventions that outline minimum conditions in the mining industry to which Zambia is a state party. These include the Safety and Health in Mines Convention (ILO Convention No. 176), and its related Recommendation 183, which define safety standards in detail. These same ILO provisions, along with article 7 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), enshrine safeguards against excessive hours at work. ILO Conventions Nos. 87, 98, and 135 guarantee workers the right to join a union of their choice—also protected by the ICESCR and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights—and shield union representatives from prejudicial acts due to their union role.

Efforts Needed to Protect Miners’ Rights

Human Rights Watch urges the new Sata government to adopt the necessary measures to enforce Zambia’s labor laws, and to ensure its laws conform with international standards. To begin, Human Rights Watch recommends that the government work to improve mine safety by ensuring there is sufficient staffing and equipment at the Mines Safety Department (MSD). Many inspectors have left their posts to pursue employment in the private sector, where remunerations are higher, and a government imposed hiring freeze has crippled the body’s effectiveness.

To improve adherence to safety regulations, Human Rights Watch also calls on the government to increase fines and other penalties that the MSD can impose, which currently provide no deterrent effect on multinational corporations. The government should likewise consider criminal prosecutions against supervisors who force workers to work in unsafe areas that threaten health and safety.

Human Rights Watch also calls on the Ministry of Labor to immediately investigate anti-union activity by Chinese and other multinational copper mining companies, including the denial of MUZ’s presence at Sino Metals and CCS. The Ministry of Labor should impose appropriate sanctions against those threatening union representatives or other unlawful anti-union activity. It should also more critically examine future collective bargaining agreements to ensure they adhere to ILO standards on issues like hours and overtime.

For its part, the Chinese government through its control of the Non-Ferrous Metals Mining Corporation, as well as the companies themselves, should ensure their operations meet Zambian and international labor standards. This should include authorizing company safety officers to halt dangerous activities and rewarding, rather than punishing, workers who act to promote safety. Meeting international standards for health, safety, and the right to organize is not only legally required for Chinese copper mining companies in Zambia, it is good business for Chinese investment and enterprises throughout Africa.

Recommendations

To the Government of Zambia

- Ensure that the Mines Safety Department, in which only 13 of 28 inspector positions are currently filled because of a hiring freeze, has sufficient staff to effectively fulfill its mandate to monitor safety and health conditions in the mining industry.

- Seek to improve the staffing and equipment of the Mines Safety Department so that it can better carry out its monitoring role. In particular, the Mines Safety Department should be able to investigate accidents and perform other duties without requiring financial and material assistance from the copper mining companies it is tasked to monitor.

- Increase the fines that the Mines Safety Department can impose against mining operations that violate safety regulations or labor laws to ensure they have a deterrent effect.

- Direct the police to investigate and prosecute as appropriate mining company officials who use threats and other forms of intimidation to force miners to work in areas they reasonably consider unsafe.

To the Ministry of Mines and Mineral Development, including the Mines Safety Department

- Ensure that safety inspectors perform proactive, unscheduled inspections—rather than respond only to reported accidents—to enforce safety regulations and better prevent future accidents.

- Liaise better with company safety officers and miners, and introduce measures that will facilitate efforts to report accidents anonymously, without threat of reprisals from management. Ensure stiff penalties against any company that punishes workers for reporting safety violations.

- Alert and assist local police when miners or safety officers inform inspectors of cases in which management forces miners to work in unsafe areas or commit physical abuse against them.

- Ensure that companies promptly replace personal protective equipment when damaged during the normal course of work, without any cost to the employee.

To the Ministry of Labor and Social Security

- Investigate immediately the refusal of Sino Metals and Chambishi Copper Smelter to sign a recognition agreement with the Mineworkers Union of Zambia (MUZ), in spite of court rulings that require those companies to allow for union branch offices. Sanction, as necessary, those companies for improper actions taken against the unions and individual workers to deny MUZ’s access.

- Ensure that union representatives at companies throughout the copper mining industry are not subject to prejudicial acts for their union activities, in violation of Zambia’s obligations under International Labour Organization conventions.

- Work with miners and management at Sino Metals and Chambishi Copper Smelter, as well as the mine unions, to ensure that hours of work meet international standards, in particular ILO Recommendation 183. Focus particularly on eliminating situations where miners work 365 days a year, six 12-hour shifts a week, or 18-hour shifts.

- Thoroughly review collective bargaining agreements for provisions that violate Zambian labor law, and seek to eliminate such provisions.

To the Chinese Government

- Integrate international human rights standards into foreign investment and foreign infrastructure and development initiatives, particularly with regard to labor rights.

- Ensure that China Development Bank and China Export-Import Bank foreign investment and development initiatives include criteria that make international human rights standards, and particularly labor rights, a key component of all such investment decisions.

- Convene a meeting of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation to discuss labor-related problems with Chinese investment initiatives in Africa and to establish mechanisms to address these problems.

To China Non-Ferrous Metals Mining Corporation

- Ensure that workers face no reprisals for removing themselves from any location at a mine when circumstances arise that reasonably appear to pose a serious danger to their safety or health.

- Enter immediately into recognition agreements with the Mineworkers Union of Zambia at Sino Metals and Chambishi Copper Smelter and ensure that miners have the right to join the union of their choice.

- Ensure that company safety inspectors can overrule, without prejudice or reprisals, a boss or manager’s decision to work in an area deemed potentially unsafe. Reward managers and safety inspectors who correctly identify health and safety hazards, and punish those who work recklessly.

- Ensure there are sufficient company safety officers, first aid kits, and other safety staffing and equipment. Take steps to include Chinese managers and Zambian workers together in daily safety talks, as well as periodic safety trainings.

- Ensure adequate provision of potable drinking water at the worksite.

To the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) of China’s State Council

- Establish an ombudsman in Chinese embassies where there are state-owned enterprises employing local workforces, allowing local employees in these companies to bring complaints of labor abuses. Investigate these complaints and, where relevant, take appropriate action against companies and management who oversee serious or frequent labor rights abuses.

- Add a provision to SASAC’s commendable “Guidelines to the State-owned Enterprises” to ensure respect for local labor unions, and in particular workers’ right to establish and join the union of their choice and the right of union representatives to operate freely and without prejudice.

Methodology

This report is based on three Human Rights Watch research missions conducted in November 2010 and July 2011 in Zambia’s copper-mining towns of Chambishi, Luanshya, Kitwe, Chingola, Solwezi, Mufulira, Kalulushi, and Ndola, as well as in the capital, Lusaka.

With China’s burgeoning investment in Africa, Human Rights Watch undertook this work to assess what the impact was in human rights terms for those directly employed by Chinese companies. The goal of this report is therefore not to assess or criticize the nebulous concept of “China in Africa,” but to look strictly at labor practices in specific Chinese government-owned companies. Zambia, a country where Chinese parastatals have been intensively engaged in mining and employing a local workforce for almost a decade, provides a useful starting point. The findings presented in this report are limited to Zambia’s copper industry.

This report draws from interviews with 143 miners, including 95 from the four Chinese copper operations and 48 from non-Chinese copper mining operations. Human Rights Watch also spoke with management representatives from the Chinese-run mines; officials from the Mineworkers Union of Zambia (MUZ) and the National Union of Miners and Allied Workers (NUMAW); officials in Zambia’s Ministry of Labour and Social Security and Ministry of Mines and Minerals Development, including the Mines Safety Department; police officials; medical professionals at the Sino-Zam Friendship Hospital that serves miners from the Chinese copper operations in Chambishi; the Zambian Human Rights Commission; representatives of national and international aid organizations; journalists; and foreign diplomats. The field research was supplemented by a review of academic publications and nongovernmental organization reports on China’s role in Africa, particularly in Zambia, and on Zambia’s copper industry, as well as meetings with experts on China’s engagement in Africa.

Most of the copper miners were interviewed individually, though a few were interviewed in small groups based on their request. Interviews were conducted away from the mining sites in order to protect the workers from reprisals by management. The interviews were conducted primarily in English, though in a few cases were conducted in a local language and translated into English by an interpreter.

Human Rights Watch has withheld names and identifying information to protect the miners from reprisal. Many expressed serious concern of being fired if management identified them as having spoken to Human Rights Watch. Details, including age, experience, and specifics of an accident have been withheld where they could expose the identity of individuals interviewed.

Among the management representatives from the Chinese-run mines, Human Rights Watch spoke principally with Zambian nationals. When they were asked if meetings could be arranged with Chinese high-level management, they all responded that it would not be possible—that meetings with groups like Human Rights Watch were conducted only by Zambian nationals. Human Rights Watch made further attempts, in Chinese, to interview Chinese managers and lower-level workers from the Chinese-run copper mines. However, Human Rights Watch was denied access to the work sites and to compounds where the Chinese workforce spends non-working hours. The Chinese workers generally spend their time outside of work in Chinese-only walled compounds. In the few cases in which direct contact was made with a Chinese national involved in the copper mining industry, Human Rights Watch was generally refused interviews. During one brief interview with a Chinese corporate public relations officer from Sino Metals, for example, the officer went inside the compound and returned to say that her boss told her that she should not be speaking with our researcher.

Human Rights Watch also sent a letter with this report’s principal findings to NFCA and China Non-Ferrous Metals Mining Corporation (CNMC). The letter to CNMC and CNMC’s detailed response translated from Chinese are in Annex I. Additional letters with relevant findings were sent to Konkola Copper Mines, Mopani Copper Mines, and Kansanshi Mining. Mopani was the only company to reply, and its responses have been included in the report.

In interviews published throughout this report, Zambian miners refer to “the Chinese” in their discussions of workplace conditions at the four copper mining companies owned by CNMC. By printing this language, Human Rights Watch does not imply that all Chinese companies in Zambia or in Africa are involved in abusive labor practices—or that all Chinese managers in Zambia’s copper industry are abusive. There are important differences among the four Chinese-owned copper mining companies and among each company’s individual managers, some of whom maintain good working relations with their Zambian employees. However, the reference to “the Chinese” as if a monolithic entity is common in Zambian discourse and, in representing what interviewees told Human Rights Watch, is important to reflect in this report.

While this report often provides both the relevant international and Zambian law for the labor abuses documented, Human Rights Watch was not able to obtain Zambia’s specific mining regulations that deal with a variety of safety issues. The mining regulations are not accessible online and, during field research, Human Rights Watch researchers were told by interviewees that they were not readily available outside of the Ministry of Mines. Human Rights Watch asked the permanent secretary of the Ministry of Mines for assistance in obtaining both the regulations and information on accidents at the various mines, and he drafted a letter requesting the Mines Safety Department to provide such assistance. A Mines Safety Department official provided the requested accident information, but, despite acknowledging having the regulations on file in print and electronically, told Human Rights Watch that he could not provide the mining regulations. The official said that only the ministry’s permanent secretary could do so. Repeated calls to the permanent secretary’s office elicited no response to requests to provide the regulations.

Monetary figures throughout this report are calculated using the rate of 4,800 Zambian Kwacha to the United States dollar.

I. Background

China’s role in African industry is neither as new nor as vast as often depicted by the media and some Western scholars, but there is no question that the last decade has seen enormous growth in Chinese investment throughout the continent. State-owned and private Chinese companies have become active in Africa in industries as wide-ranging as construction, telecommunications, manufacturing, farming, and mining—and the direct employment of local workers is likely to continue to grow in coming years. It is within this framework that Human Rights Watch has undertaken this work—not to assess “Chinese investment” or “China in Africa”—but to evaluate human rights and labor practices in specific Chinese government-owned companies.

Zambia’s copper industry provides a useful magnifying lens into Chinese labor practices in Africa because of the historic relationship between the two countries, the relative length of time that Chinese state-owned companies have been engaged in Zambian industries, and the number of Zambians directly employed by these companies. One scholar on China’s role in Zambia has called the Chinese mining operations there “politically embedded in China’s Africa policy.”[1] Zambia is one of the world’s biggest copper producers, with an industry that dates back to the 1920s. It enjoys a workforce highly educated in mining, historically strong labor unions, and detailed mining regulations. Zambia is home to a multiparty democracy since 1991 and has never faced internal armed conflict. It represents, in many ways, one of the most potentially protective environments for labor in the developing world. Unfortunately, the reality is quite different, and Zambians working for Chinese-owned copper mines find themselves vulnerable to a range of abuses.

Chinese engagement in Zambia’s copper industry comes through China Non-Ferrous Metals Mining Corporation (CNMC). CNMC, which owns the four Chinese subsidiaries that control daily operations in Zambia, is, like other Chinese state-owned enterprises, “under the management of [China’s] State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission [SASAC] of the State Council.”[2] The State Council, in turn, is China’s “highest executive organ of State power, as well as the highest organ of State administration,” run by authorities including a premier appointed by China’s president and the ministers of foreign affairs and labor.[3] Given that CNMC is state-owned, the Chinese government is more directly responsible for the wage, health, and union policies that affect the Zambian workforce.

A Body of Work on Business and Human RightsHuman Rights Watch has investigated patterns of human rights abuse linked to multinational companies around the world, with a particular focus on mining, oil, and other extractive industries. That work has included research on patterns of human rights abuse linked to the operations of several multinational oil and mining companies in countries including Nigeria, Sudan, Papua New Guinea, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. We have also documented abuses connected to the logging industry in Indonesia and alleged violations of labor rights in the United States by Wal-Mart and by several major European companies, as well as human rights problems caused by corruption in oil-rich countries including Equatorial Guinea and Angola. We have used that research to advocate for better government regulation of companies’ human rights practices and to advocate directly with companies themselves to acknowledge and ensure accountability for past abuses and to improve their human rights records. In addition, Human Rights Watch participates in several voluntary initiatives designed to bring companies, governments, and civil society advocates together to ensure greater respect for human rights, such as the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights. |

China in Africa

In 2001, the Chinese government formalized a policy of “going out” (zou chuqu, in Mandarin), in which the central government actively supported Chinese companies in economic investment abroad that fit “with one or more of four objectives: providing a market for Chinese products, improving resource security, enabling technology transfer, and promoting research and development.”[4] Chinese engagement in Africa did not begin at this point—as just one example, the Chinese government financed and constructed between 1970 and 1975 the US$500 million Tanzam Railway that linked Zambia’s mines to Dar es Salaam’s port—but the direct engagement in industry across the continent has grown steadily throughout the last decade. In 2006, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, which has organized four summits involving China and African states, published “China’s African policy,” which includes:

[The Chinese government] supports competent Chinese enterprises to cooperate with African nations in various ways on the basis of the principle of mutual benefit and common development, to develop and exploit rationally their resources, with a view to helping African countries to translate their advantages in resources to competitive strength, and realize sustainable development.[5]

China’s increasing role in Africa has spawned a breathtaking number of academic articles, books, media reports, documentaries, and commentary.[6] At its best, this attention has critically examined the positive and negative implications of this “going out” for Africans. This includes China’s role in highly abusive states like Sudan and Zimbabwe, as well as the greater access to cheap goods that Chinese exports often bring, though at times with negative impacts on local production. At its worst, some publications have turned unsupported assertions into fact and drastically overstated the size of Chinese investment and its relationship to natural resource exploitation. Many publications have also treated every “Chinese” company the same—and also as a representation of the Chinese government—whether state-owned or run by a private Macau businessman.[7] At times, this has been exploited by Western politicians and investors to create a false dichotomy between “good” Western investment and “bad” Chinese investment. While there are concerning patterns to Chinese employment practices, this should not malign or ignore the positive potential for Chinese investment in improving economic conditions in Africa.

There is a growing body of research analyzing specific labor and human rights abuses by Chinese employers abroad. The African Labour Research Network said in a 2009 report that while there were differing labor conditions in Chinese-owned companies across African countries and industries, “there are some common trends, such as tense labour relations, hostile attitudes by Chinese employers towards trade unions, violations of workers’ rights, poor working conditions and unfair labour practices.”[8]

In September 2009, the United Kingdom-based Rights and Accountability in Development (RAID) released a report on Chinese mining operations in the Katanga region of the Democratic Republic of Congo. While it found abusive labor practices across the industry, RAID’s survey showed that conditions in the Chinese companies ranked worse than competitor companies from the United States and Europe, “with unanimous agreement that Chinese companies do not comply with the Congolese mining code and other laws and regulations.”[9] This resulted in, among other things, commonplace accidents and health hazards.[10] The Chinese companies in the RAID study were almost all privately owned and relatively small; those in Zambia, by contrast, fall under the enormous Chinese state-owned company (or parastatal) CNMC.

In response to recurring labor complaints, and the “risks that limited oversight brings to China’s long-term interests in Africa,” China’s Ministry of Commerce issued in August 2006 “a set of policy guidelines ‘to strengthen regulations in order to avoid conflicts … in order to protect the national interest.’”[11] In January 2008, SASAC, which oversees state-owned companies including the one operating in Zambia’s copper mines, likewise issued “instructing opinions” on corporate social responsibility, urging parastatals to improve labor rights, safety and health standards, and environmental protection.[12] Guideline 7 of the instructing opinions admonishes state-owned enterprises to “give top priority to ensuring work safety, safeguarding the legal interests of employees, [and] promoting career development,” while guideline 13 says that “safe and healthy working conditions and living environment are necessary to ensure the health of employees, prevent any harm of occupational and other diseases to employees.”[13] In Zambia, CNMC is failing to follow the SASAC guidelines, and it is unclear what efforts the company is making or has made to follow them.

History of Zambia’s Copper Industry

Copper mining began in the British colony of Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia, in 1928 and immediately dominated the country’s economy.[14] The stretch along the Zambian and Congolese border became known as the Copperbelt for the enormous deposits located there. More than 80 years later, the Copperbelt remains the “backbone of the Zambian economy,” contributing to nearly 75 percent of the country’s exports and two-thirds of the central government revenue during years of strong copper prices.[15]

At Zambia’s independence in 1964, copper mining was controlled by two private companies: the UK (and later Roan) Selection Trust and the British-South African owned Anglo American Corporation. With high copper prices in the 1960s and early 1970s, Zambia grew to a middle-income country, with one of Africa’s highest Gross Domestic Products.[16] Zambia’s first president, Kenneth Kaunda, was quickly concerned with the little money that the companies invested in the country’s long-term growth, however. The government sought higher taxes and the companies demurred; in 1969, following a constitutional referendum, Kaunda responded by nationalizing the industry.[17] The two copper mining companies were reorganized and became Nchanga Consolidated Copper Mines Limited (NCCM) and Roan Consolidated Mines Limited (RCM).[18] In 1982, NCCM and RCM merged to form Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines (ZCCM).

Prior even to nationalization, the copper mining companies were expected to provide housing, foodstuffs, and health care for employees. After nationalization, the amenities grew further as companies “operated ‘a cradle to grave’ welfare policy” in which they offered free education for miners’ children and subsidized housing, food, electricity, water, transport, and family burial arrangements.[19] Services were provided to entire mining communities, with companies maintaining roads, street lights, and trash collection and offering social and sporting clubs as well as skills training for women and youth. The mining units also maintained town hospitals, often where no government hospital existed. The mining divisions, and ZCCM as a whole, essentially replaced the government in providing social services. The powerful union, the Mineworkers Union of Zambia (MUZ), was influential in obtaining many of these benefits.[20]

The crash of copper prices in the mid- and late 1970s led to a downward spiral of Zambia’s economy. By 1994, Zambia had become one of the poorest countries in the world, with per capita income down 50 percent from 1974.[21] The copper industry’s revenues could no longer meet the costs of salaries and benefits. Production also collapsed, from 750,000 metric tons in 1973 to just over 250,000 tons in 2000.[22] By the 1980s, Zambia faced massive debts. With pressure from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, Zambia entered into structural adjustment programs that sought a reduction in government expenditures and the privatization of certain state assets.[23] Trade unions, including MUZ, supported the privatization—as by this time new investment was deemed crucial to revitalize the industry.[24] The copper mines, as the most valuable country asset, were central to privatization. After an extended fight between the government, union, and financial institutions over whether the mines would be sold to a single investor or broken up and sold separately, the latter course was taken.[25] Sales began in 1997 (see text box for current owners of main mining assets).

Copper Mining Operations in Zambia

|

Company |

Private Investors |

Nationality of Investor |

|

Konkola Copper Mines (KCM) |

Vedanta Resources (79%) |

Indian |

|

Mopani Copper Mines |

Glencore International (74%), First Quantum Minerals (16%) |

Swiss, Canadian |

|

Kansanshi Mining |

First Quantum Minerals (79%) |

Canadian |

|

Chambishi Metals |

Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (90%) |

Kazakhstani, British |

|

Lumwana Copper Mine |

Barrick Gold Corporation (100%)[26] |

Canadian |

|

Chibuluma Mines |

Metorexgroup (85 %) |

South African |

|

China Luanshya Mine, NFCA (Chambishi Copper Mine), Chambishi Copper Smelter, Sino Metals |

China Non-Ferrous Metals Mining Corporation (CNMC) (85 %) |

Chinese |

Copper prices rose steadily from 2003 to 2008, before plummeting in 2008 to 2009 with the global economic crisis. A number of workers in Zambia’s copper mining industry were laid off, and several mines closed or threatened to close.[27] Prices recovered to previous highs by late 2010 and, in early 2011, reached new records—selling at over $10,000 per metric ton (see graph in Annex II). Current copper prices have led to further expansion of Zambia’s copper industry, with several new mines recently opening or about to open. Moreover, on July 1, 2011, the World Bank declared that Zambia had moved back to low-middle income status.[28] As of 2009, Zambia was the world’s eighth-largest copper producer, and, with the recent growth, it is predicted to enter the top five by 2014.[29]

Through its long history in copper mining, Zambia developed strong mining regulations and labor laws. A professor at Zambia’s Copperbelt University who specializes in the industry, told Human Rights Watch that following a serious mining accident in 1970 at the Mufulira mine, the Zambian government adopted extensively from Canadian mining regulations. As a result, he said, almost every activity underground—from the equipment miners are supposed to wear in certain sections, to the employment of safety officers, to relevant safety procedures—is tightly regulated under law.[30] Godwin Beene, the permanent secretary in the Ministry of Mines and Minerals Development, likewise said:

In Zambian mining, whether open-cast or underground, the industry is regulated tightly by mine safety regulations. If there are any abuses of those regulations, the actors can be punished…. We are a country well versed in mining, and no one is above the law.[31]

The tight regulation of the Zambian copper industry should protect its workers from companies with poor safety practices—unfortunately, this has not been the case with the Chinese-run mines.

Zambian Government as Minority Owner

While no longer the principal owner of the Zambian copper mines—nor involved in the day-to-day operations—the Zambian government maintains a minority ownership in the country’s copper mines. When it sold the mines during privatization, the parastatal mine operator ZCCM became ZCCM Investments Holdings (ZCCM-IH) and retained minority interests. ZCCM-IH’s primary shareholder, at 87.6 percent, is the Zambian government, with private equity holders accounting for the rest.[32] At present, ZCCM-IH owns, for example, 10 percent of Mopani and Chambishi Metals, 15 percent of the Chinese-run underground mines, and around 20 percent of KCM.[33]

While the government’s ownership is meant to protect the state’s financial interests, it also places a greater responsibility on the government to prevent and address abusive labor conditions. As one Zambian journalist who follows the copper industry told Human Rights Watch, “They can’t pretend to not know what’s going on. They have representation on the board of these companies.”[34] The conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO) are often framed in terms of workers’ rights, employers’ obligations to provide adequate conditions, and governments’ responsibility to ensure that employers follow these requirements. In Zambia, with partial ownership of each mine, the government takes on both the direct responsibility of providing adequate conditions and the more traditional governmental responsibility of monitoring their fulfillment.

Chinese Investment in Zambia, Copper Industry

By the end of 2010, China’s investment in Zambia was around $2 billion, according to the Chinese state-run news agency Xinhua, placing Zambia third for Chinese investment after South Africa and the United Kingdom.[35] Moreover, the annual growth rate of China-Zambia bilateral trade stayed above 30 percent since 2000, topping $2.5 billion in 2010.[36] Although China is active in construction, agriculture, energy supply, manufacturing, and telecommunications, the heart of its involvement in Zambia remains mining.

In 1998, as the Zambian government was selling the copper mining assets during privatization, China Non-Ferrous Metals Mining Corporation (CNMC) purchased the Chambishi Copper Mine in an open bid. Non-Ferrous China Africa (NFCA) began production for CNMC in 2003—13 years after the Chambishi mine was last in active production.[37] In 2006, CNMC opened Sino Metal Leach Zambia (known as Sino Metals) near the NFCA underground mine to provide lower-level processing into exportable copper cathode through its tailings leach plant and Solvent Extraction/Electrowinning (SX/EW) plant.[38]

The following year, Zambia became the first African site for China’s special economic zones, or SEZs, announced originally at the 2006 Forum on China–Africa Cooperation.[39] Known in Zambia as the Zambia-China Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone (ZCCZ), SEZs are designed to provide “a combination of world-class infrastructure, expedited customs and administrative procedures, and (usually) fiscal incentives that overcome barriers to investment in the wider economy.”[40] The zone was placed in Chambishi, with the goal to spur additional investment in the copper industry and related production.

CNMC began construction on the Chambishi Copper Smelter (CCS) soon thereafter, and the plant opened in early 2009. In January of that year, the investor at Luanshya Copper Mine closed its operations and announced the mine was for sale; CNMC purchased it several months later. The mine reopened in December 2009 after hundreds of millions of dollars in investment; more than 2,000 miners are employed at China Luanshya Mine (CLM).[41]

The four copper mining companies owned by the parastatal CNMC are:

- NFCA, an underground mine and surface-level plant in the town of Chambishi;[42]

- CLM, an underground mine, processing facility, and open-cast mines in Luanshya;

- CCS, a copper smelting plant in Chambishi; and

- Sino Metals, a copper processing plant in Chambishi.

CNMC continues to make large-scale investment in these companies, with CLM set to begin production in the fourth quarter of 2011 in the Muliasha open-cast mines; the recent opening of a second underground mining shaft at NFCA; ongoing construction at CCS to both increase the tons of copper it can produce and add cobalt processing capabilities; and improvements and expansion at the Sino Metals plant.[43]

In a November 2010 article in the Chinese newspaper Southern Weekend, the general manager of CNMC said that the NFCA mine was “[t]o date … China’s only overseas mine that is already producing regularly and at a profit.” The paper said that NFCA had annual profits of $40 million and, by 2008, had “recouped its 2003 investment.”[44]

Labor Problems and Low Wages in the Chinese Mines

Almost immediately after production began at NFCA in 2003, the Chinese companies faced complaints about labor abuses, particularly low pay, poor safety conditions, and union busting. While some of the anti-Chinese vitriol seemed to reflect racism fueled by cultural differences, the Chinese companies were—and, as this report shows, remain—the biggest violator of workers’ rights among Zambian copper industry employers.[45]

In April 2005, in the most deadly event in the history of Zambian copper mining, 46 Zambian workers were killed in an explosion at a CNMC-owned factory manufacturing cheap mining explosives near NFCA. The public outrage at that event spurred some changes, including slightly improved safety practices and greater acceptance of the country’s two mining unions—MUZ and the newly established National Union of Miners Allied Workers (NUMAW).

On July 25, 2006, workers rioted in protest of the failure to improve their salaries and working conditions. Beginning during the night shift, workers destroyed equipment and attacked a Chinese manager. The next day, some miners moved the protest toward the Chinese managers’ living quarters; shots were fired, with five miners reportedly wounded. Union officials told Reuters at that time that the shots came from a Chinese manager, a claim also reported by others.[46] A sixth person was shot earlier that day by a security officer or policeman. Although the police investigated, its findings were never made public and no charges were filed. Many of the workers who participated in the strike or riots were fired.[47]

A similar event occurred on October 15, 2010, in the town of Sinazongwe, when two Chinese managers at Collum Coal Mine shot 11 workers protesting poor conditions.[48] Collum Coal Mine is owned by a private investor—not a Chinese parastatal like the copper industry’s CNMC—but the event mobilized an outcry against Chinese labor problems more generally. Like the earlier Chambishi event, no one was ultimately prosecuted. A Zambian journalist for an international media outlet told Human Rights Watch:

It just confirmed how powerful the Chinese are in Zambia. The Chinese, you hear them say, we can do anything; this has been proven after the shooting in Sinazongwe. The state dropped the charges, it just negotiated a compensation package. The message was, “Give them money, and any problems will be solved.” They constantly speak in these undertones.[49]

Labor strife continued at the copper mines in January and March 2011, as workers went on strikes that approached full-scale riots at both NFCA and CCS.[50] Workers at both companies demanded significantly higher pay increases than were offered during collective bargaining negotiations, ultimately ending their strike after management slightly improved its offer.

In response to the persistent confrontations with employees over labor abuses, Chinese business leaders in Zambia have at times blamed the country’s regulatory structure. Zan Baosen, the vice general manager of the Zambia-China Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone, was quoted by a Chinese newspaper as saying:

[The laws are] really “too sound”—the standard of the legal system is a little too ahead of its time… Almost 50 percent of the people are unemployed and yet they still want to have so many housing allowances, education allowances and transportation allowances. Also, employees can’t be dismissed without good reason. They can only be dismissed when their work record is poor.... It is necessary to have some laws in the early stages of development; equality gets sacrificed. Inequalities are a reality at every stage of development. They should learn to accept this.[51]

Another longstanding issue invariably at the top of the list of concerns of Zambian mine workers is wages. Chinese copper mining companies often pay base salaries around one-fourth of their competitors’ for the same work. Although the Chinese copper mines do pay more than the Zambian monthly minimum wage, raised in early 2011 to 419,000 Kwacha (US$87), workers and union officials who spoke to Human Rights Watch consistently said that the pay was insufficient to meet their basic needs. A miner at Chambishi Copper Smelter (CCS) explained problems to Human Rights Watch echoed by his colleagues:

Before the [2009] global crisis, I worked at KCM’s [Konkola Copper Mine, owned by an Indian mining conglomerate] smelter. At the time I was laid off, I was making 2.9 million Kwacha (US$604) there as my basic pay…. Now, for working in the CCS smelter, I make just over 640,000 ($133). The pay here at CCS, it’s peanuts. It’s a drop in the ocean….

The money is very difficult with the economy here. I have a wife and three kids. A two-room house in the township is 500,000 Kwacha ($104) a month to rent. So even when you count my allowances, that leaves maybe 500,000 for food, cooking oil, electricity, water, [children’s] education, and anything else. It’s just not possible. The only way I am surviving is from money I saved when working at KCM. That and I borrow money.It’s Kalaba, which means borrowing money that you have to pay back with 25, 50 percent interest…. I’m falling into serious debt, but it’s the only way to survive. At KCM, I used to save money, advance my family, and I was doing the same job.[52]

Pay has grown steadily since CNMC first opened their copper mining operations. The lowest monthly salaries that existed at Sino Metals and CCS two years ago, around 350,000 Kwacha ($73), would not meet the recently raised national minimum wage.[53] NFCA underground mining has more than doubled its lowest pay range since initiating full-scale operations in 2004. However, inflation in Zambia has also increased by between 8 and 18 percent every year since 2004, which means the rising salaries have led to little real increase.[54] Moreover, the competitors of the Chinese companies have increased their own salaries at the same or even greater rate, meaning that the relative gap in pay has actually widened over this period. (For a comparison of wages at different copper mining companies in Zambia as of September 2011, see Annex IV.)

Exporting Abuses?: Similar Labor Problems in China’s Mining IndustryThe closest corollary to Zambia’s copper industry in China is the country’s massive coal mining sector. Its problems provide telling indicators of the challenges faced by workers in the foreign mining operations of Chinese parastatals. China’s coal miners constitute China’s poorest and most marginalized social groups: migrant workers from the rural countryside and laid-off former employees of restructured or closed down state firms.[55] Safety risks including fires, floods, and gas explosions have plagued Chinese coal mines for decades and claim the lives of thousands of Chinese workers every year.[56] Those deaths are linked to what Chinese labor rights activists have described as the “reckless disregard for miners’ lives” exercised by state-owned mine operators in their pursuit of greater production and higher profits.[57] A 2008 report uncovered abuses and safety risks in Chinese coal mines including the denial of mandatory safety equipment such as respirators, the manipulation or sabotage of safety equipment such as toxic gas meters to ensure uninterrupted production, and threats of dismissal or fines against workers who protest safety shortcomings.[58] Those problems appear to persist. An August 2011 state media report on coal mine safety linked the sector’s safety risks and resulting high death tolls on “mine bosses [who] were frequently forcing workers to boost mining, defying safety rules ordered by the government.”[59] Official data from China’s State Administration of Coal Mine Safety Data indicates that in 2010 coal mine accidents claimed the lives of 2,433 Chinese miners, a decline from 2,631 deaths in 2009.[60] That reduction is due to unspecified “headway in coal mine safety work,” the director of the State Administration of Coal Mine Safety, Zhao Tiechui, told state media in June 2011.[61] However, Chinese government efforts to improve safety and reduce fatalities in coal mines have had little impact on illegal, unlicensed mining operations where worker safety remains a low priority for mine owners.[62] A February 2011 article in 21st Century Business Herald, a newspaper in southern China, described the influence of these domestic problems on labor tensions in Zambia and the perception among some Chinese businesspeople that “African trade unions and labor laws are … very troublesome:” A key reason why some Chinese enterprises [in Zambia] would commit such atrocities [referencing the Collum Coal Mine shooting] is that no form of mature worker-management relations has yet developed in China itself. The disregard for labor rights that some local governments [in China] show, their tendency to side with management, and an environment where abuses by the management in domestic labour disputes go unmonitored, have caused a culture of “alienation” of sorts. This has also cultivated the tendency of certain Chinese investors to feel “culture shock” in Africa. [63] |

Politicization of Chinese Investment, 2011 Election

While the role and impact of Chinese investment is frequently politicized throughout Africa—by Western governments and media, local governments, and the Chinese government itself—it may have been most hotly debated in Zambia. In the lead-up to the 2006 presidential election between incumbent President Levy Mwanawasa and his principal challenger, Michael Sata, Sata tried to capitalize on the anti-Chinese fervor following the Chambishi explosion and shootings. He visited Taiwan at that government’s invitation and, in a direct affront to Beijing, made a campaign promise to recognize Taiwan’s independence if elected.[64] China’s ambassador responded by saying that China might sever diplomatic ties if Sata won and halt its investment.[65] Mwanawasa won the election handily, but Sata’s Patriotic Front proved popular in the Copperbelt.

After Mwanawasa died in August 2008, another presidential election was held that October—this time between Sata and Vice President Rupiah Banda, who became acting president upon Mwanawasa’s death. While he continued to decry poor working conditions in the copper industry, Sata promised to protect China’s investments in Zambia.[66] Banda won an extremely close election, with Sata claiming fraud.[67]

On September 20, 2011, Zambians returned to the polls, with Banda and Sata the two main candidates. While his anti-Chinese demagoguery was nowhere near the 2006 levels, Sata remained outspoken against Chinese investment practices in the prelude to elections.[68] When election results had not been announced by September 22, riots broke out in the main Copperbelt towns[69]—where dozens of miners interviewed by Human Rights Watch had threatened “problems” should Banda remain in power. The following day, the electoral commission proclaimed Sata the winner, with around 43 percent of the vote. Banda, with 36 percent of the vote, conceded and called on Zambians “to unite and build tomorrow’s Zambia together.”[70]

In his inaugural speech, Sata said that foreign investment in the mining sector would still be welcomed, but companies must respect the country’s labor laws.[71] The first weeks of his administration have been marked by frenetic activity related to the copper mining industry in particular, and the economy more generally. Sata immediately called on the labor ministry to increase the monthly minimum wage from the current 419,000 Kwacha ($87).[72] He also quickly replaced the head of the anticorruption commission and the police chief, dismissed the governor and board of Zambia’s central bank, and announced that he would further disband the boards of four state-owned companies.[73]

On October 4, the government announced a ban on metal exports, including copper, due to fears that companies were misreporting their exports. The government said that new regulations to improve transparency would be established by October 16. On October 6, however, the government lifted the ban and implied that the regulations might take longer to finalize.[74] Then on October 13, Sata’s minister of mines, Wylbur Simuusa, said that the government was looking to increase its shareholding ownership in the copper mining operations to 35 percent in order to receive “more benefits from the mines.” Simuusa stressed that this was not a step toward nationalization, and any changes would be done in negotiations with the mining companies.[75]

At the same time that the Sata government was announcing widespread changes at the national level, workers throughout Zambia went on wildcat strikes in demand for better working conditions.[76] While strikes were not confined to the copper industry or to Chinese-run companies,[77] the Chinese-owned copper mines were quickly among the hardest hit. On October 5, workers at NFCA walked out and refused to return underground, demanding a 100 percent pay increase to reach similar wage levels as competitor copper mining companies.[78] On October 7, workers at Sino Metals likewise went on strike, followed by a strike at Chambishi Copper Smelter that began on October 12.[79] Miners at NFCA returned to work on October 10 after receiving assurances for their requested pay increase, but then went back on strike on October 17 when the promise appeared to fall through.[80] The following day, NFCA management drafted a memorandum demanding that the miners return to work; according to local news reports, they offered workers a 200,000 Kwacha monthly salary increase ($42), with promises to continue negotiations after work restarted.[81] When the strike continued on October 19, NFCA fired at least 1,000 miners and told them they had 48 hours to appeal the decision.[82] Zambia’s deputy labor minister quickly requested that the company reinstate the fired workers to solve the dispute amicably, and meetings were planned involving the government, management, and the unions.[83] At time of publication, the outcome was not yet clear.

At CCS, miners appeared to slowly return to work with the promise that the government and their unions would quickly take up these issues during yearly collective bargaining negotiations that were due to begin in early November.[84] In the meantime, production ground to a halt at all three Chambishi-based Chinese copper mining operations.

“Good Investors, but Bad Employers”: Dichotomy between Welcomed Chinese Investment and Abusive Labor PracticesWhile almost every miner from Chinese mining operations interviewed by Human Rights Watch complained about their conditions of service, particularly pay and safety practices, many expressed appreciation for the large amount of capital investment that the Chinese investors have brought to the copper industry. As noted in the background, CNMC has taken over several operations that previous investors abandoned. In addition to reopening these mines, the Chinese-run mines are drastically expanding operations. Miners, including an electrician at China Luanshya Mine (CLM), repeatedly expressed gratitude to the Chinese for the investment, noting that it had saved or created thousands of jobs: “The investment has changed greatly with this investor. So much more money is coming into the mine. The last one [Enya Holdings] completely neglected the mine, letting it fail; we were dormant for a year. Now, the Chinese have come and we’re growing, we’re set to open up a new mine.”[85] A management representative from CLM told Human Rights Watch that the Chinese were investing US$170 million to upgrade the Baluba underground shaft that was originally constructed in 1936; another $350 million was being invested to create the Muliashi open-pit mines that will begin production in late 2011 and add more than 1000 new jobs.[86] The Chinese constructed Chambishi Copper Smelter from scratch, opening in 2008 and now employing 900 workers—with ongoing construction to expand further. The smelter, according to union officials and miners who work there, is state-of-the-art. [87] In addition to appreciation for the renovation and expansion work, several miners and union officials noted that the Chinese investors have also made welcome improvements to equipment and technology in the current mines. A NUMAW union leader told Human Rights Watch that the Chinese companies are “modernizing the mines, making them more efficient and making the jobs easier. The CCS smelter, for example, is fantastic, largely computerized.”[88] A draftsman, responsible for planning the drilling underground at CLM, said similarly: “They have brought a lot of computers and technology. In the past, we used a pencil to plot out the drilling pattern; now, each of us in planning has our own computer. This is a big improvement. They have really improved the technology and machinery.”[89] But the praise for the investment was almost always followed by frustration that the Chinese companies could spend so much on improved equipment, new smelting or processing operations, or even new mines, yet not pay workers anywhere near the salaries that other copper mining companies pay. One underground miner at NFCA said simply, “The Chinese think bringing investment alone is sufficient.”[90] A miner at CLM felt similarly, “These people have brought investment. They are opening Muliashi open-pit. They are hard workers. We appreciate this. But they don’t care about Zambians. If they change that, we’ll be happy. They are good investors, but they are bad employers.”[91] Finally, a miner at CCS told Human Rights Watch: “The new investor is bringing materials, looking at how to reap lots of money from the mines. But he is not caring after us. When you look at the cost of machinery the investor is bringing in, compared to what he is giving me, it is totally unacceptable. I should also have value…. Why can’t they return some profits into personnel, safety, and CSR [corporate social responsibility], as well as into the new investments for mines and machinery?”[92] Numerous miners from the Chinese operations said that while people took the jobs in Chinese mines over being unemployed, poor work conditions and wages meant they left as soon as an opportunity existed in another copper mine. |

II. Health and Safety

Sometimes when you find yourself in a dangerous position, they tell you to go ahead with the work. They just consider production, not safety. If someone dies, he can be replaced tomorrow. And if you report the problem, you’ll lose your job.

—Underground miner at NFCA, November 2010[93]

Copper mining carries serious health and safety risks in both the mining and processing operations. Underground copper mining is particularly dangerous, with at least 15 recorded fatalities in Zambia every year since 2001 and numerous other serious injuries and long-term health problems incurred. While accidents are not unique to the Chinese-owned mines, union officials, miners who had worked in Chinese and non-Chinese operations, and even government representatives who spoke to Human Rights Watch all said that the Chinese copper operations were the worst for health and safety conditions.

Miners from the Chinese-owned operations describe safety regulations that are routinely flouted. While the companies employ Zambian safety officers officially tasked with monitoring compliance with national safety procedures, they are given almost no authority; final decisions on whether to work in potentially dangerous areas rests with the manager, generally the Chinese manager, alone. Those who spoke with Human Rights Watch said Chinese bosses routinely force workers to continue in areas considered unsafe—under threat of being fired should the worker refuse—resulting in health problems and accidents. In order to hide the extent of the safety problems, several Chinese-run copper operations appear to deliberately underreport accidents; at times, they bribe workers—often without difficulty, given low salaries—not to report them.

The government’s Mines Safety Department, situated in the Ministry of Mines and Mineral Development, is tasked with enforcing the country’s mining regulations.[94] However, the department’s grossly inadequate staffing and funding as well as the very low fines that can be imposed—eliminating any real deterrent effect—have made the agency largely ineffective.

As discussed below, Zambia has not effectively enforced either domestic or international labor law in the Chinese-owned copper mines in Zambia. The International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) obliges states to ensure “[s]afe and healthy working conditions.[95] International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 176 concerning Safety and Health in Mines sets out the basic obligations of states and employers regarding mine safety, as well as the rights and duties of workers and their unions.[96]

Health and Safety Hazards

Workers throughout Zambia’s copper mining industry are exposed to a variety of health and safety hazards that lead to accidents, including fatal accidents, and long-term health consequences, particularly affecting their lungs. ILO Convention No. 176, as well as the related ILO Recommendation 183 concerning Safety and Health in Mines, was drafted specifically to deal with the risks that come with mining—with the goal “to prevent any fatalities, injuries or ill health affecting workers or members of the public.”[97] While accidents and some health consequences are likely to occur even when companies follow—and governments enforce—safety regulations, the failure to take seriously health and safety precautions leads to far greater problems.

A nurse at Sino-Zam Friendship Hospital, where miners at the three Chinese-owned Chambishi operations receive free medical care, described the injuries she sees from NFCA miners:

Rock falls are the most frequent of the severe problems. They are at times fatal, or result in crushed bones. We’ve had to do traumatic amputations of fingers, for example…. There are other injuries from [chemical] gassing, also acid and electric burns. And then there are common problems when the concentrate dust shavings get in the miners’ eyes…. We also see general health problems from the contact with dust and fumes, due to poor ventilation. Pneumoconiosis [black lung] and particularly silicosis occur.[98]

Underground miners likewise considered a rock fall the most dangerous event they faced. It occurs most often during blasting or drilling, when insufficient support has been created above or to the side of worksites. Accidents due to insufficient support can occur as a result of worker negligence or when mining bosses insist that workers continue past areas with sufficient support—so that production is not slowed for building new supports. Enormous rocks come crashing down during a rock fall, injuring and at times killing those caught underneath. Workers identified other fatalities as a result of electrocutions underground, though these occur far less frequently. At times, platforms on which workers are drilling or placing explosives, for example, can collapse, and workers suffer severe and even fatal injuries when plummeting. A worker died in one such accident at NFCA on December 30, 2010.

Among the less immediately dangerous sources of complaints at NFCA is the poor ventilation underground that can lead to both short-term and long-term health problems. ILO Convention No. 176 requires employers to take all necessary measures to ensure “adequate ventilation” underground. Recommendation 183 states that mines “should be ventilated in an appropriate manner to maintain an atmosphere … in which working conditions are adequate,” in accordance with applicable national and international standards on dust and gas.[99]

An underground miner who works with explosives told Human Rights Watch:

The ventilation is very bad down there, as we drill deeper. There is lots of smoke, lots of dust, and yet we aren’t given respirators. We just have a dust mask. We all have lung problems. I inhale the stuff all the time, because they don’t give us a respirator; so my lungs and throat always hurt.[100]

Another underground miner at NFCA, who worked with Konkola Copper Mines (KCM) until he was laid off during the 2008 global economic crisis, said that “some of the areas underground where we work would be off limits in other companies due to poor ventilation…. We can feel the lung problems already, even though our friends in other mines have been working for much longer. We know we’re at risk for health problems because of the conditions here.”[101]

One miner interviewed by Human Rights Watch from the Mufulira mine operated by Mopani Copper Mines likewise complained about poor ventilation underground, saying, “Even with the safety equipment, we just breathe in dust. We can feel it in our lungs; I’ve had lots of problems. In some areas, they should improve the ventilation before we start work, but they don’t.”[102] In a 2008 article in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, researchers took dust samples from Mopani’s two underground mines and found that “59% and 26% of Mufulira and Nkana Mine samples, respectively, were above the calculated U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration permissible exposure limit.” They concluded that “weak dust monitoring at these mines … may increase the risk of nonmalignant disease in many miners” and recommended that “Zambian mining houses and the government establish crystalline silica analysis laboratory capacity and adopt dust mass concentration occupational exposure limits for more protective dust monitoring of workers.”[103] In response to a letter from Human Rights Watch outlining concerns, Mopani’s Chief Executive Officer David Callow said that the company takes the issue of silicosis “very seriously and is focused on reducing incidence” through measures including “improved localized dust management in work places”; programs raising employees’ awareness on “dust control and personal protective equipment usage”; implementing “personalized dust monitoring techniques” for Mopani employees working in high-exposure areas; and more frequent medical checkups. Mopani’s response continued:

Silicosis generally has a long latent period to manifest, which can be 20 years or more, so some of the benefits of [the company’s] focus since privatisation may not yet be apparent. Even still, incidence has been almost halved since privatisation. Progress in this area is monitored closely by Mopani’s board.[104]

At the processing and smelting operations, miners work with acids and other noxious chemicals to separate the copper from the rock. Sulfuric acid is one of the most commonly used substances. As with underground miners, workers are also routinely exposed to dust, fumes, and other hazardous substances. In certain departments, often referred to as “hot metal” departments, miners work in environments of extreme heat. Fatal accidents are far less common in processing than in underground mining, but acid burns and lung disease, for example, can be common when companies do not comply with safety regulations.[105]

To protect against problems associated with mining, ILO Convention No. 176 requires employers in mining operations to inform workers of the work’s hazards; to “take appropriate measures to eliminate or minimize risks resulting from exposure to those hazards”; to ensure “adequate protection against risk of accident or injury to health,” including through the provision and maintenance, at no cost, of personal protective equipment; and to provide first aid at the workplace as well as “access to appropriate medical facilities.”[106] The biggest problems in the Chinese-owned mines are the second and third requirements, on minimizing risks and providing adequate protection. Rather than eliminating or minimizing the risks, Chinese mine owners and managers appear to increase the risks through threats against workers who would prioritize safety over production.

While these problems are discussed in more detail below, a doctor who had worked for more than a decade at the mine hospital for Luanshya Mine, which was owned and run by a Swiss-based investor until sold to CNMC in 2009, told Human Rights Watch:

The number of accidents under the Chinese has gone way up, we have seen this in the hospital. They’re not concerned about safety. There have been several fatal accidents since they took over, and we did not see many at all before them. I see lots of cases of crushed fingers as well, one just last week…. I can tell you from the hospital side, accidents are a major problem now. We see more than ever before. And most of these could be prevented if safety was prioritized. We need to sensitize the Chinese about the safety rules, about the labor laws, and they need to start following these.[107]

To bring attention to potential safety hazards, daily safety talks among work units—at the beginning of each shift—are fairly standard across the copper mining industry. A miner at the tailings and leach plant was one of several KCM employees to underscore their importance: “The company emphasizes safety talks before the job. These are done within our sections, for about five minutes in every shift before we start. Everyone takes part, and we talk about the dangers. These have reduced the number of accidents.”[108] Miners at Mopani and Kansanshi likewise mentioned daily safety talks in various departments.[109]

A national-level official at the Mineworkers Union of Zambia told Human Rights Watch that there was a stark difference at NFCA in particular: “Most companies take safety talks seriously. This goes back to the days of ZCCM, they have been standard since. NFCA is the big exception.”[110] Miners at NFCA told Human Rights Watch that safety talks had been introduced in early 2011—showing, as elsewhere, that there have been improvements among the Chinese-run companies—but one underground miner cited a remaining problem echoed by others:

The Chinese are never there for the safety talks, it’s just the Zambians.Even when you have a Chinese manager, when he makes the decisions underground, he doesn’t take part. Only the Zambian manager, who has no real authority, leads the morning safety talk.[111]

The result, as stated by an underground mine truck operator, is that“what we hear during the safety talk and what they do underground is very different.”[112]