Summary

Since the beginning of anti-government protests in March 2011, Syrian security forces have killed more than 4,000 protesters, injured many more, and arbitrarily arrested tens of thousands across the country, subjecting many of them to torture in detention. These abuses, extensively documented by Human Rights Watch based on statements of hundreds of victims and witnesses, were committed as part of a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population and thus constitute crimes against humanity.

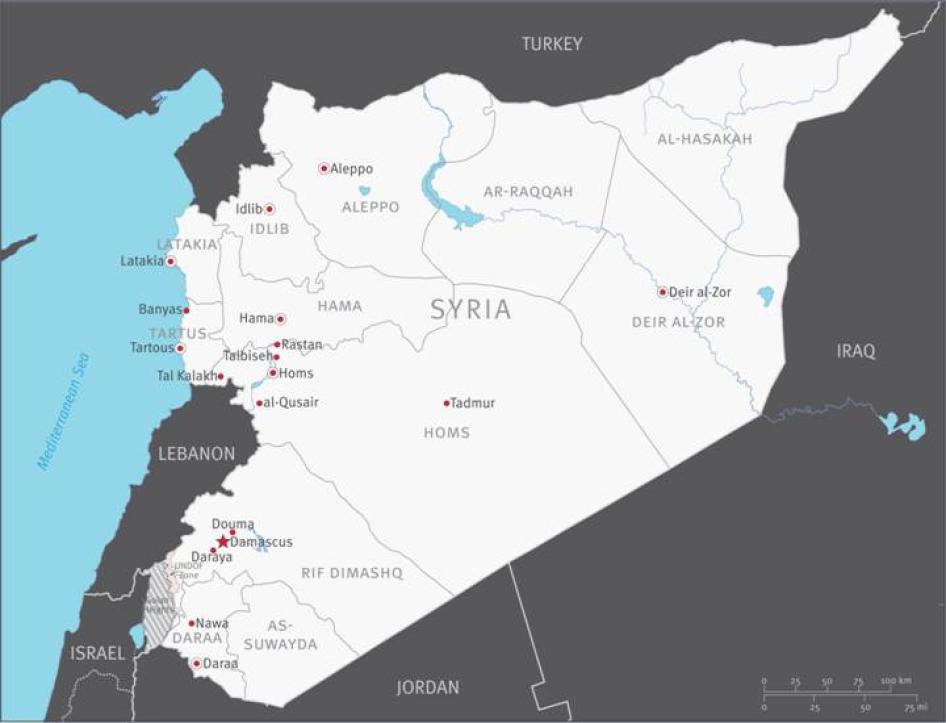

This report focuses on the individual and command responsibility of Syrian military commanders and intelligence officials for these crimes. It is based on interviews with 63 defectors both from the army and from the intelligence agencies, generally known as the mukhabarat. These defectors shared with Human Rights Watch detailed information about their units’ participation in violations and the orders they received from commanders at different levels. The defectors provided information on violations that occurred in seven of Syria’s fourteen governorates: Damascus, Daraa, Homs, Idlib, Tartous, Deir al-Zor, and Hama.

Human Rights Watch interviewed all of the defectors separately and at length. Violations described in this report are those that were described separately by several defectors and with sufficient detail to convince the researcher that the interviewees had first-hand knowledge of the incidents in question. Several accounts have been excluded because interviewees did not provide such detail.

The statements of soldiers and officers who defected from the Syrian military and intelligence agencies leave no doubt that the abuses were committed in pursuance of state policy and that they were directly ordered, authorized, or condoned at the highest levels of Syrian military and civilian leadership.

Human Rights Watch’s findings show that military commanders and officials in the intelligence agencies gave both direct and standing orders to use lethal force against the protesters (at least 20 such cases are documented in detail in this report) as well as to unlawfully arrest, beat, and torture the detainees. In addition, senior military commanders and high-ranking officials, including President Bashar al-Assad and the heads of the intelligence agencies, bear command responsibility for violations committed by their subordinates to the extent that they knew or should have known of the abuses but failed to take action to stop them.

Syrian authorities repeatedly claimed that the violence in the country has been perpetrated by armed terrorist gangs, incited and sponsored from abroad. Human Rights Watch has documented several incidents in which demonstrators and armed neighborhood groups have resorted to violence. Since September, armed attacks on security forces have significantly increased, with the Free Syrian Army, a self-declared opposition armed group with some senior members in Turkey, taking responsibility for many of them. Syrian authorities have claimed that more than 1,100 members of the security forces have been killed since the beginning of the anti-government protests in mid-March.

However, despite the increased number of attacks by defectors and neighborhood defense groups, witness statements and corroborating information indicate that the majority of protests that Human Rights Watch has been able to document since the uprising began in March have been largely peaceful. The information provided for this report by defectors, who were deployed to suppress the protests, supports that assessment and underlines the lengths to which the authorities have gone to misrepresent the protesters as “armed gangs” and “terrorists.” But there is a risk—as seen in hard hit places like the city of Homs—that bigger segments of the protest movement will arm themselves in response to attacks by security forces or pro-government militias, known as shabeeha.

Considering the evidence that crimes against humanity have been committed in Syria, the pervasive climate of impunity for security forces and pro-government militias, and the grave nature of many of their abuses, Human Rights Watch believes that the United Nations Security Council should refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court (ICC). Crimes against humanity are considered crimes triggering universal jurisdiction under international customary law (meaning that national courts of third states could investigate and prosecute them even if they were committed abroad, by foreigners and against foreigners). All states are responsible for bringing to justice those who have committed crimes against humanity.

Killings of Protesters and Bystanders

All of the 63 defectors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that their commanders gave them standing orders to stop the protests “by all means necessary” during regular briefings and prior to deployment. The defectors said that, even when it was not specified, they universally understood the phrase “by all means necessary” as an authorization to use lethal force, especially given the provision of live ammunition as opposed to other means of crowd control. For example:

- “Abdullah,” a soldier with the 409th Battalion, 154th Regiment, 4th Division, said that two high-level commanders, Brigadier General Jawdat Ibrahim Safi and Major General Mohamed Ali Durgham, ordered the troops to shoot at protesters when his unit was deployed to areas in and just outside of Damascus.

- “Mansour,” who served in Air Force Intelligence in Daraa, said that the commander in charge of Air Force Intelligence in Daraa, Colonel Qusay Mihoub, gave his unit orders to “stop the protesters by all possible means,” which included the use of lethal force.

About half of the defectors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the commanders of their units or other officers gave direct orders to open fire at protesters or bystanders, and, in some cases, participated in the killings themselves. According to the defectors, the protesters were not armed and did not present a significant threat to the security forces at the time. For example:

- “Hani,” who served in the Special Operations branch of Air Force Intelligence, said that Colonel Suheil Hassan gave orders to shoot directly at protesters on April 15 during a protest in the Mo`adamiyeh neighborhood in Damascus.

- “Amjad,” who was deployed to Daraa with the 35th Special Forces Regiment, said that he received direct verbal orders from the commander of his unit, Brigadier General Ramadan Mahmoud Ramadan, to open fire at the protesters on April 25.

Human Rights Watch collected extensive information about the participation of specific military units and intelligence agencies in attacks against the protesters in different cities and large-scale military operations that resulted in killings, mass arrests, torture, and other violations. The appendix to this report contains information on the structure of the units, locations where they were deployed, violations in which they were allegedly involved, and, wherever this information was available, the names of their commanders or officials in charge.

Human Rights Watch has previously documented and publicized widespread killings of protesters across the country, based on the statements of hundreds of protesters, victims of abuses, and witnesses. Evidence collected from defectors for this report corroborates some of these previously documented incidents. Several defectors who participated in the April 25 military operation in Daraa, for example, confirmed killings documented by Human Rights Watch in the June 2011 report, “We’ve Never Seen Such Horror.”

The exact number of those killed is difficult to verify given the government-imposed restrictions on independent reporting inside Syria, but the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has put the figure at more than 4,000 as of December 2, 2011, while the Violations Documentation Center (VDC), a monitoring group working in coordination with the Local Coordination Committees (LCC), a network of Syrian activists, has compiled a list of 3,934 civilian deaths as of December 3, 2011. The Syrian government has stated that more than 1,100 members of the security forces have been killed.

Arbitrary Arrests, Torture, and Executions

According to information collected by Human Rights Watch, the Syrian security forces have conducted a massive campaign of arbitrary arrests and torture of detainees across Syria since the beginning of anti-government protests in March 2011. Information provided by the defectors, many of whom personally participated in arrests and ill-treatment, further corroborates these findings.

The defectors described large-scale, arbitrary arrests during protests and at checkpoints, as well as “sweep” operations in residential neighborhoods across the country. Most of the arrests appear to have been conducted by the intelligence agencies, while the military provided support during the arrest and transportation of detainees.

The number of people arrested since the beginning of the protests is impossible to verify. As of December 3, 2011, the VDC had documented almost 15,500 arrests. The real number is likely much higher.

Information from the defectors about sweep operations in which they participated lends support to allegations of a massive campaign of arbitrary arrests. Multiple examples cited in the report show that the security services routinely arrested hundreds, if not thousands, of detainees, including many children, following the protests and after they took control of different towns. For example:

- “Said,” who was deployed to Talbiseh with the 134th Brigade, 18th Division, said that after the military moved into the town in early May, intelligence agencies and the military started conducting daily raids, arresting “anyone older than 14 years—sometimes 20, and sometimes a hundred people.” Said also said that the arrest raids, authorized by the mukhabarat and the military, were accompanied by “brazen looting” and burning of shops.

- “Ghassan,” a lieutenant colonel deployed in Douma with the 106th Brigade, Presidential Guard, said that his brigade, on average, arrested about 50 people, any male between ages 15 and 50, at his checkpoint after each Friday protest.

According to the defectors, arrests were routinely accompanied by beatings and other ill-treatment, which commanders ordered, authorized, or condoned. Those who worked in or had access to detention facilities told Human Rights Watch that they witnessed or participated in the torture of detainees.

The defectors from both the military and the intelligence agencies who were involved in the arrest operations said that they beat detainees during their arrest and transportation to the detention facilities almost without exception. They cited specific orders they received from their commanders in this respect.

While most of the defectors interviewed said they were only involved in transporting the detainees to various detention facilities, a few, mainly those who served in intelligence agencies, said they had first-hand knowledge of the situation inside the facilities. Their statements confirm the widespread use of torture in detention previously documented by Human Rights Watch and provide additional details on the intelligence officials in charge.

One of the most worrisome features of the intensifying crackdown on protesters in Syria has been the growing number of custodial deaths since the beginning of July. Local activists have reported more than 197 such deaths as of November 15, 2011. Two defectors interviewed by Human Rights Watch shared information about the summary execution of detainees or deaths from torture in detention in two areas: Douma, and Bukamal. A lieutenant colonel who served in the Presidential Guard said that he witnessed a summary execution of a detainee at a checkpoint in Douma around August 7, 2011. A defector who had been posted in the eastern town of Bukamal, by the Iraqi border, said that he saw 17 bodies of anti-government activists including a number that had surrendered to an intelligence agency several days earlier.

Denial of Medical Assistance

Defectors also provided further information about the denial of medical assistance to wounded protesters, the use of ambulances to arrest the injured, and the mistreatment of injured individuals in hospitals controlled by intelligence agencies and the military, a disturbing pattern that Human Rights Watch and other organizations have previously documented.

Several examples cited by the defectors strongly suggest that these violations were ordered, authorized, or condoned by commanders rather than committed at the initiative of individual members of the armed forces or intelligence agencies. According to the defectors, security forces brought some of the wounded protesters directly to the detention facilities where they mistreated them.

They said that injured protesters who were brought to the military, or military-controlled, hospitals were also subjected to mistreatment and beatings by intelligence agents and hospital staff. Those whose wounds were serious and did not allow for immediate transportation were held in temporary detention facilities on hospital premises before being transferred to other places of detention.

Command Responsibility of High-Ranking Officers and Government Officials

Given the widespread nature of killings and other crimes committed in Syria, scores of statements from defectors about their orders to shoot and abuse protesters, and the extensive publication of these abuses by the media and international organizations, it is reasonable to conclude that the senior military and civilian leadership knew or should have known about them. The Syrian military and civilian leadership also clearly have failed to take any meaningful action to investigate and stop these abuses. Under international law, they would thus be responsible for violations committed by their subordinates.

With regards to President Bashar al-Assad, who is the commander-in-chief of the Syrian armed forces, and his close associates, including the heads of intelligence agencies and the military leadership, Human Rights Watch has collected additional information that strongly indicates their direct knowledge and involvement in the violent crackdown on protesters.

Human Rights Watch believes that, in addition to military and intelligence officers mentioned in connection with specific incidents in this report, these commanders, including the highest-ranking officers and heads of intelligence agencies, should be investigated on the grounds of their command responsibility for violations committed by units under their control. Under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, criminal liability applies to both those who physically commit the crimes and to senior officials, including those who give the orders and those in a position of command who should have been aware of the abuses but failed to prevent them or to report or prosecute those responsible.

Repercussions for Disobeying Illegal Orders

The consequences for disobeying orders and challenging government claims about the protests have been severe. Eight defectors told Human Rights Watch that they witnessed officers or intelligence agents killing military personnel who refused to follow orders. Three defectors told Human Rights Watch that the authorities had detained them because they refused to follow orders or challenged government claims. At least two said that security forces beat and tortured them. Other defectors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that security forces detained and tortured them for participating in protests during leave or before they started their military service.

The defectors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that security forces detained them for relatively short terms in detention centers on their base or in nearby detention facilities. According to witnesses other defectors were sent to the notorious Tadmor military prison in Homs governorate.

A prison guard from Tadmor told Human Rights Watch that by the time he defected in August the prison housed about 2,500 prisoners. While the prisoners initially included only military personnel, the prison started receiving a growing number of detained protesters and defectors after protests erupted in March. He told Human Rights Watch that security forces there beat and tortured all prisoners, but gave defectors particularly harsh treatment.

One defector said that security forces arrested a close relative to force him to return to his unit.

Virtually all defectors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they were convinced that officers or intelligence agents would kill them if they refused to follow orders. In standard operations to suppress protests, they said that conscript soldiers from the army or intelligence agencies lined up in front, while officers and intelligence agents stayed behind, giving orders and making sure that they followed orders. On several occasions, officers and intelligence agents explicitly threatened to kill soldiers if they did not follow orders.

Most of the defectors said that they tried to evade orders by aiming at protesters’ feet, or firing in the air, but in some cases felt that they had to shoot at the protesters or commit other abuses because they thought that they would themselves be killed otherwise. A few took up arms against intelligence agents and officers who ordered the killings, and many said they defected when they realized that their commanders were ordering them to shoot at unarmed protesters as opposed to the “armed gangs” that they had been told to expect.

Recommendations

The Syrian government’s response to credible accusations of human rights violations has been inadequate and has fostered a climate of impunity, including for unlawful killings, torture, enforced disappearance, and arbitrary detention. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any public information about specific investigations or prosecutions related to violations described in this report.

While many states have condemned Syria’s use of violence and some have followed those words with actions aimed at pushing the Syrian government to change course, the international community has been slow to take collective action.

Considering the evidence that crimes against humanity have been committed in Syria, the pervasive climate of impunity for security forces and pro-government militias, and the grave nature of many of their abuses, Human Rights Watch calls on the United Nations Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court—the forum most capable of effectively investigating and prosecuting those bearing the greatest responsibility for the crimes committed and offering accountability to the Syrian people. The Security Council should also require states to suspend all military sales and assistance to the Syrian government and adopt targeted sanctions on officials credibly implicated in the ongoing grave, widespread, and systematic violations of international human rights law. Human Rights Watch also calls on all states, in accordance with their national laws, to bring to justice under the principle of universal jurisdiction those who have committed crimes against humanity.

Map of Syria

© 2011 Human Rights Watch

Methodology

This report is based on 63 interviews with defectors from Syria’s armed forces and intelligence agencies. Human Rights Watch researchers conducted these interviews in person in Syria’s neighboring countries from May to November 2011. Researchers also interviewed dozens of witnesses in Syria and in neighboring countries to establish the context of the anti-government demonstrations in Syria and corroborate defectors’ statements.

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted the interviews in Arabic or with the help of Arabic-English translators.

The defectors interviewed by Human Rights Watch served in regular army units, the Special Forces, the Military Police, the Presidential Guard, the General Intelligence Directorate, the Air Force Intelligence Directorate, and in other units. While the majority were conscript soldiers, 14 defectors said they had served as officers, the highest-ranking being a lieutenant colonel. Their units were deployed to suppress protests all over Syria, including in the governorates of Damascus, Daraa, Homs, Hama, Idlib, Tartous, and Deir al-Zor.

Syria has been and remains under an information blockade, and obtaining information about the government crackdown on protesters is extremely difficult. Those who speak to investigators or share information through electronic means face severe repercussions. To protect defectors, other witnesses, and their families, Human Rights Watch has changed their names and withheld information about the location of the interviews. In the report, pseudonyms are indicated with quotation marks.

Human Rights Watch interviewed all of the defectors and other witnesses separately and at length. Violations described in this report are those that several defectors described separately and with sufficient detail to convince the researcher that the interviewees had first-hand knowledge of the incidents in question. Several accounts have been excluded because interviewees did not provide such detail.

The majority of incidents described in this report mention the names and ranks of commanders who allegedly gave orders to commit the abuses. In some cases, it was possible to corroborate these allegations through independent interviews with two or more witnesses. In other cases the report gives the name and rank of a commander based on the statement of one defector, but only if Human Rights Watch researchers deemed this was justified by the level of detail and the credibility of the overall evidence provided. While a single person’s statement cannot be the basis of a definitive conclusion about the responsibility of the commanders in question, Human Rights Watch believes that such allegations require a prompt investigation.

I. Background

Protests in Syria

Protests in Syria broke out on March 18 in response to the arrest and torture of 15 school children by the Political Security Directorate, one of Syria’s intelligence agencies, in the southern city of Daraa. Attempting to suppress the demonstrations, security forces opened fire on the protesters, killing at least four. Within days the protests grew into rallies that gathered thousands of people.[1] Protests quickly spread to the rest of the country in a show of sympathy with the Daraa protesters. The government’s violent response only further fueled demonstrations.

At the time of writing, protests are still taking place regularly in the governorates of Daraa, al-Hasaka, Idlib, Deir al-Zor, Homs, Hama, and in the suburbs of the capital, Damascus.

Syrian security forces, primarily the intelligence agencies, referred to generically as mukhabarat, and government-supported militias, referred to locally as shabeeha, regularly used force, often lethal, against largely peaceful demonstrators, and often prevented injured protesters from receiving medical assistance.[2] As the protest movement endured, the government also deployed the army, usually in full military gear and backed by armored personnel vehicles, to quell protests.

While consistent witness statements leave little doubt regarding the widespread and systematic nature of abuses, the exact number of people killed and injured by Syrian security forces is impossible to verify. At the time of writing, Syria remains off-limits to international journalists and human rights groups, and communications are often interrupted in affected areas. However, an expanding network of activists grouping themselves in local coordination committees (LCC) and making extensive use of the Internet, including social media, and reporting the information to a monitoring group, the Violations Documentation Center (VDC), have compiled a list of 3,934 civilians killed, including more than 300 children, as of December 3, 2011.[3]

Syrian authorities went to great lengths to convince the public, both Syrian and international, as well as the members of security forces deployed to quell the protests, that “criminals” and “armed terrorist gangs,” incited and sponsored from abroad, have been responsible for most of the violence.

On October 7, Syria’s deputy foreign minister, Faisal Mekdad, told the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) that his country was “grappling with terrorist threats” and promised to give the UN a list of “more than 1,100 people who have been killed by the terrorists,” including civil servants and police.[4] In an interview with the British Sunday Times newspaper published on November 20, 2011, President al-Assad blamed “armed gangs” for the killing of 800 members of his security forces.[5]

As this report illustrates, however, in at least some cases members of the security forces fell victim to friendly fire or deliberate killings for their refusal to follow the orders. Defectors interviewed for this report also said that in many instances the dead and injured whom the authorities claimed through the state media had been killed or wounded by "armed gangs" and "terrorists" were actually the victims of the government's repression.

Human Rights Watch has documented several incidents in which demonstrators, at times supported by military defectors, have resorted to violence.[6] For example, demonstrators set government buildings on fire in the towns of Daraa, Jisr al-Shughur, and Tal Kalakh, destroyed monuments to President Bashar al-Assad and his father Hafez al-Assad, and torched several vehicles belonging to the security forces.[7] Witnesses described some of these episodes to Human Rights Watch; we also viewed evidence of such attacks on amateur videos available online. Several witnesses also told Human Rights Watch that protesters had killed members of security forces, usually after the security forces had opened fire on them.

At the same time, statements from witnesses, including defectors, protesters, and journalists, indicate that the protesters have been unarmed in the majority of cases documented by Human Rights Watch and other human rights organizations.

Since September, armed attacks on security forces have increased, with the Free Syrian Army, a self-declared opposition armed group with some senior members in Turkey, taking responsibility for many of them, although some commentators, diplomats, and even opposition members have questioned its level of control and organization.[8] On November 28, 2011, during a meeting in Turkey, the Free Syrian Army agreed with the Syrian National Council (SNC), an umbrella group of Syrian opposition, that the Free Syrian Army will “not organize any assault” against Syrian government forces anymore, and will resort to “armed resistance” only “for protecting civilians during protests.”[9]

At the same time, several defectors and other witnesses expressed concern that the government’s continued brutal crackdown had increased sectarian tensions and violence. For example, both Sunni and Alawite residents of the central governorate of Homs, a predominantly Sunni area with a large Alawite minority, already report an increase in kidnappings by unknown gunmen and talk about their fear of driving through some neighborhoods in their cities. Journalists have reported on a number of killings that seem motivated by sectarian retribution.[10] The threat of an increase in sectarian violence has led United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay to warn during an emergency session on Syria at the UN Human Rights Council on December 2, 2011 that “[t]he Syrian authorities’ continual ruthless repression, if not stopped now, can drive the country into a full-fledged civil war.”[11]

In addition to shooting at protesters, security forces launched a massive campaign of arrests, arbitrarily detaining hundreds of protesters across the country, routinely failing to acknowledge their detention or provide information on their whereabouts, and subjecting them to torture and ill-treatment. The intelligence agencies have also arrested lawyers, activists, and journalists who endorsed or promoted the protests, as well as medical personnel suspected of caring for wounded protesters in makeshift field hospitals or private homes.[12]

Human Rights Watch documented large-scale arbitrary detentions, including the detention of children, in Daraa, Damascus and its suburbs, Banyas and surrounding villages, Latakia, Deir al-Zor, Tal Kalakh, Hama, Homs, Zabadani, Jisr al-Shughur, and Maaret al-Nu`man.[13] Many of the arrests appeared entirely arbitrary, with no formal charges brought against the detainees. It appears that most detainees were released several days or weeks later, but others have not reappeared. Many of those cases constitute enforced disappearances, as their families have had no information on their fate or whereabouts for a prolonged period of time.[14]

Released detainees, some of them children, said that they, as well as hundreds of others they saw in detention, were subjected to torture and ill-treatment. All of the former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch described appalling detention conditions, with grossly overcrowded cells, where at times detainees could only sleep in turns, and lack of food.[15]

In several cities, including Daraa, Tal Kalakh, Rastan, Banyas, Deir al-Zor, Hama, and parts of Homs, Syrian security forces moved into neighborhoods in military vehicles, including tanks and armored personnel carriers, under the cover of heavy gunfire. They imposed checkpoints, placed snipers on roofs of buildings, and restricted movement of residents in the streets. In some places, like Daraa, the security forces imposed a full-out siege that lasted for several weeks, cutting off all means of communication and subjecting residents to acute shortages of food, water, medicine, and other essential supplies.[16]

Deployment of Syria’s Security Forces

In March 2011 the Syrian government began deploying security forces from the armed forces, the intelligence agencies, and the shabeeha to quell the protests. First in Daraa, and later, as this report illustrates, in Damascus, Deir al-Zor, Idlib, Hama, Homs, Latakia, and Tartous governorates, the armed forces and intelligence agencies, often working in concert, conducted operations to stamp out the protests.

There are four main intelligence agencies in Syria:

- The Department of Military Intelligence (Shu'bat al-Mukhabarat al-'Askariyya), which includes the Palestine Branch;

- The Political Security Directorate (Idarat al-Amn al-Siyasi);

- The General Intelligence Directorate (Idarat al-Mukhabarat al-'Amma), which is generally referred to by its previous name, State Security (Amn al-Dawla); and

- The Air Force Intelligence Directorate (Idarat al-Mukhabarat al-Jawiyya).[17]

Intelligence agencies overlap extensively, and there are no clear rules for which agency will take the lead in a particular action. These agencies have virtually unlimited de facto authority to carry out arrests, searches, interrogation, and detention. They are more than a simple arm of the government; they are in practice autonomous entities that report directly to the highest officials in the Syrian state, and according to some analysts, directly to the President.[18]

Units from the armed forces deployed to quell the protests include the Presidential Guard, the 3rd, 4th, 5th, 9th, 11th, 15th, and 18th Divisions, and various Special Forces Regiments, including the 35th, 45th, and 46th Regiments. Service in the armed forces is compulsory for adult males[19] and the majority of army defectors are low-level conscripts.[20]

More detailed information regarding the specific military units and intelligence agencies involved in the attacks against protesters in different cities and large-scale military operations is provided in the appendix to this report. This includes information on the structure of the units, locations where they were deployed, violations in which they were allegedly involved, and, where this information is available, the names of their commanders or the officials in charge.

Defections from Armed Forces and Security Agencies

The rate of defections from the Syrian armed forces and intelligence agencies appears to have steadily increased since the authorities deployed their security forces to suppress anti-government protests in March 2011. Estimates of the number of defectors vary significantly. Riad al-Asaad, the head of the Free Syrian Army, a self-declared armed opposition group, told Reuters that his group consisted of 15,000 defectors by mid-October; but many others believe that those numbers are exaggerated.[21] An opposition member told Human Rights Watch in November that he estimated that there were a “few thousand—in the single digits—defectors in the Free Syrian Army.”[22]

The majority of the defectors told Human Rights Watch that they decided to defect when they discovered that the authorities and their officers had deliberately misled them about the nature of the protests. According to the defectors, when the protests erupted in mid-March, the authorities immediately restricted soldiers’ access to information and launched a propaganda campaign to convince the soldiers that they were fighting “armed gangs” and “terrorists” supported by an international conspiracy to destroy Syria. A conscript serving in the Military Police in Deir al-Zor told Human Rights Watch: “Protests in Daraa started on March 18. The very next day they confiscated our cell phones and barred us from watching anything but Syrian state TV and the pro-government Dunya TV. On the news, they started telling us about terrorists.”[23]

A conscript soldier based in Rankous, a suburb of Damascus, gave a similar account to Human Rights Watch:

Soldiers in the unit were under close surveillance; we couldn’t really talk to each other. As for cell phones, they were never allowed, but this rule was never enforced. But starting in April, commanders started breaking the cell phones whenever they caught somebody using them. All TV channels were banned, aside from official Syrian TV.

Every morning commanders conducted a meeting, talking about how good Assad and his family were, and about the threats from the terrorists. And then they also forbade us from taking leave. It used to be eight days every two months, but after April nobody was allowed to go.[24]

A member of the 45th Special Forces Regiment, deployed in the coastal areas of Banyas and Markeb, told Human Rights Watch:

We were told that there are terrorist groups coming into the country with funding from Bandar Bin Sultan [a prominent Saudi prince who served until 2009 as Saudi's national security chief], Saad al-Hariri [a former Lebanese prime minister], and Jeffrey Feltman [US Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern affairs].[25]

Military commanders often communicated this information to soldiers during daily briefings, referred to as nasharat tawjeeh. A lieutenant in the 14th Division posted in Damascus described the briefing: "Each morning we had guidance briefings. They would tell us there are gangs and infiltrators. They would show us pictures of dead soldiers and security forces."[26] One defector, who had served in the army for 25 years, most recently as a communications officer responsible for his unit’s informational radio programs, told Human Rights Watch:

Usually, I wrote the news segments myself and higher-ranking officers only made minor edits to what I wrote, but when I wanted to report on the protests in March, the commanders gave me a prepared statement instead of looking at what I had written. The statement said that terrorist gangs were attacking civilians. Some of my relatives had been participating in the protests, so I knew better. I refused to read it on air, saying that I was not feeling well, but somebody else read it instead.[27]

Defectors from units serving in a number of governorates all over Syria described similar measures taken to prevent them from finding out what was happening, indicating a high-level policy to restrict soldiers’ access to information.

Isolated from any independent sources of information, defectors say they and many of their fellow soldiers initially believed the government statements. A 20-year-old conscript who was stationed on the border with Israel told Human Rights Watch:

When the events started in Daraa, the officers took all our TVs, radios, and phones. The only news we got was through internal radio, and it was all about hooligans, foreign elements, etc. Most of us believed it, and we were scared; even the movement of birds and butterflies would set off shooting.[28]

For many of the defectors, the turning point came when they were finally allowed to go home on leave. The realization that close relatives and friends were participating in the protests and had been attacked by the security forces convinced many that the government’s claims were false. Some even participated in protests themselves while on leave. A few of the defectors said that it was the killing or arrests of family members and friends during protests that convinced them to defect.

Others said they decided to defect after officers ordered them to shoot at peaceful protesters or after they witnessed or participated in the killing of large numbers of protesters. For example, one soldier in the 65th Brigade, 3rd Division, who was sent to Douma to suppress protests in April, told Human Rights Watch:

At one point we killed eight people in 15 minutes. The protesters were unarmed. They didn’t even have rocks! That’s when I decided to defect. I threw away my gun and ran towards the protesters. Somebody picked me up in a van and took me home to Daraa.[29]

Defectors also said that they became disillusioned by officers planting weapons in mosques, frequent friendly fire incidents between intelligence agents and army soldiers, and claims, intended to mislead, that “armed protesters” and “terrorists” had killed soldiers who had actually been killed by intelligence agents, friendly fire, or accidents.

II. Individual and Command Responsibility for Crimes against Humanity

Since the beginning of anti-government protests in March 2011, Syrian security forces have killed more than 4,000 protesters and bystanders in their violent efforts to stop the protests, according to UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay.[30] They have injured many more and arbitrarily arrested tens of thousands across the country, subjecting many of them to torture and ill-treatment in detention. Local activists have reported more than 197 deaths in custody.[31] Human Rights Watch has collected and publicized extensive documentation on these violations committed in governorates of Daraa, Homs, Damascus, Hama, and other places across the country.[32]

Human Rights Watch believes that these abuses were committed as part of a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population and thus constitute crimes against humanity under customary international law and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[33] The independent, international commission of inquiry on Syria appointed by the UN Human Rights Council and set up by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has reached the same conclusion.[34]

The Rome Statute defines an “attack directed against any civilian population” as “a course of conduct involving the multiple commission of acts [which qualify as crimes against humanity such as murder] against any civilian population, pursuant to or in furtherance of a State or organizational policy to commit such attack.”[35]

The statements of soldiers and officers who defected from the Syrian military and security forces leave no doubt that the widespread and systematic abuses, including killings, arbitrary detentions, and torture, were committed in pursuance of a state policy targeting civilians or against the civilian population and that they were directly ordered, authorized, or condoned at the highest levels of Syrian military and civilian leadership.

For individuals to be found culpable of crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute, they must have had knowledge of the crime.[36] That is, perpetrators must have been aware that their actions formed part of the widespread or systematic attack against the civilian population.[37] While perpetrators need not be identified with a policy or plan underlying the crimes against humanity, they must at least have knowingly taken the risk of participating in the policy or plan.[38]

Human Rights Watch’s findings, presented in detail below, show that military commanders and officials in the intelligence agencies gave both direct and standing orders to use lethal force against protesters, as well as to unlawfully arrest, beat, and torture detainees. On many occasions, they were not only present during the commission of the crimes, but personally participated in the violations. In several cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the commanders oversaw the cover-up operations, such as the disposal of dead bodies following the killings.

Individuals implicated in such acts bear individual criminal responsibility for crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute.[39]

Military commanders and intelligence officials could also bear responsibility for violations committed by units under their command in accordance with the doctrine of command responsibility under the Rome Statute, even if they did not directly participate in or give orders to commit the violations.[40]

The Rome Statute stipulates that military commanders bear responsibility for crimes committed by forces under their “effective command and control, or effective authority and control” when they knew or should have known about the crimes and failed to prevent them or to submit the matter for prosecution.[41] The same principle applies to civilian officials for crimes committed by their subordinates that concerned “activities that were within the effective responsibility and control of the superior” when they “knew, or consciously disregarded information which clearly indicated, that the subordinates were committing or about to commit such crimes” and “failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures within his or her power to prevent or repress their commission or to submit the matter to the competent authorities for investigation and prosecution.”[42] A head of state and members of government are not exempt from responsibility.[43]

Several examples indicate that President Bashar al-Assad, who is the commander-in-chief of the Syrian armed forces, the heads of intelligence agencies, and other high-ranking officials mentioned in this report have ordered, authorized, or condoned the violent crackdown on protesters. It is also reasonable to assume that they knew about the extent and nature of the repression through official channels.[44] In addition, information about violations committed by the military and security forces since the beginning of protests in Syria has been publicized by several international organizations, including Human Rights Watch, the media, and Syrian activists. Multiple international bodies have raised concerns about these violations as well. The independent commission of inquiry appointed by the Human Rights Council extensively documented the violations and presented its report to the HRC, and the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution condemning the abuses. In these circumstances, the failure to stop the violations and bring their perpetrators to justice also makes these officials criminally responsible under the doctrine of command responsibility.

The Rome Statute stipulates that, subject to some exceptions, individuals accused of crimes against humanity cannot avail themselves of the defense of following superior orders.[45] One such exception is if an individual acts under a threat of “imminent death or of continuing or imminent serious bodily harm,” made explicitly or “constituted by other circumstances beyond that person’s control,” if “the person does not intend to cause a greater harm than the one sought to be avoided.”[46] As this report illustrates, many rank-and-file soldiers in the Syrian armed forces and intelligence agencies appear to have acted when faced with the choice of committing the crimes or being killed for disobeying the orders, and, in many cases, they seem to have tried to prevent the worst consequences of their actions—for example, by firing in the air, or aiming at the protesters’ feet to avoid killing them.

Another exception may apply to individuals—both soldiers and commanders—who acted in self-defense, or in defense of others “against an imminent and unlawful use of force in a manner proportionate to the degree of danger.”[47]

As mentioned above, Human Rights Watch has documented a number of instances where the protesters resorted to violence, yet these incidents of violence by protesters remained exceptional compared to the number of attacks on protesters we documented.

We also asked every military defector interviewed for this report about the use of violence by the protesters, and all but one of them said that they never felt under threat when dealing with protests. Some mentioned that the protesters threw stones at the security forces, one defector mentioned being involved in a shoot-out with armed protesters in Bukamal in the Deir al-Zor governorate, and one defector mentioned that he was aware of a group of protesters in a town in Daraa governorate that was armed, but had not seen it in action.

Incidents where protesters have allegedly resorted to violence should be further investigated and in some cases may provide a valid defense against accusations of involvement in crimes against humanity where individuals responded in a manner that was proportionate to the degree of danger. The defectors’ statements, however, support the conclusion that in many cases, the force used against the protesters was clearly disproportionate to the threat presented by the overwhelmingly unarmed crowds.

Considering the evidence that crimes against humanity have been committed in Syria, the pervasive climate of impunity for security forces and pro-government militias, and the grave nature of many of their abuses, Human Rights Watch calls on the UN Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to the ICC. Human Rights Watch believes that the ICC is the forum most capable of effectively investigating and prosecuting those bearing the greatest responsibility for serious crimes committed in Syria. Human Rights Watch also recalls that crimes against humanity are considered crimes that trigger universal jurisdiction under international customary law, and thus all states should bring to justice those who have committed them.[48]

Killings of Protesters and Bystanders

The Violations Documentation Center, in cooperation with Local Coordination Committees (LCC), a network of Syrian activists documenting and publicizing violations inside Syria, has collected the names of 3,934 people killed by the security forces between the beginning of anti-government protests in March and December 3, 2011.[49] In her statement on December 2, 2011, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay said that more 4,000 people, over 300 of them children, had been killed.[50] Human Rights Watch has documented and publicized many of these killings.[51]

Defectors’ statements provide further information about the systematic nature of the killings authorized by commanders of the armed forces and intelligence agencies at the highest levels.

All of the military defectors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that their commanders gave standing orders to “stop the protests at any cost” during regular briefings to the troops and prior to deployment. In many cases, the commanders explicitly authorized the use of lethal force against largely peaceful protesters.

In about half of the cases, interviewees said that commanders followed these standing orders with specific orders during the operations against protesters to “open fire,” “shoot,” “kill,” “destroy,” and the like.

Human Rights Watch also obtained information about commanders’ involvement in the planning and implementation of specific operations that resulted in a large number of civilian casualties. Further, on several occasions documented by Human Rights Watch, commanders gave orders or participated in the transfer—or burial—of the bodies of protesters killed in attacks during demonstrations.

Standing orders

All of the 63 defectors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they received standing orders to suppress, stop, or disperse the protests “by all means necessary” prior to deployment.

These orders were communicated during regular morning meetings or immediately before deployment to specific areas either directly by high-ranking commanders, or by lower-level commanders referring to orders received from high-ranking commanders. The defectors said that even when it was not specified, they universally understood the phrase “by all means necessary” as an authorization to use lethal force, especially in the light of the fact that they were issued live ammunition as opposed to other means of crowd control.

Examples of such orders documented by Human Rights Watch include:

· “Ahmed,” a soldier with the Presidential Guard, who was deployed to Douma in April, said that Brigadier General Talal Makhlouf, commander of the 105th Brigade, Presidential Guard, gave his unit verbal orders to “suppress the protest and shoot if people refuse to disperse.”[52]

· “Jamal,” another soldier from the 105th Brigade also said that Brigadier General Talal Makhlouf gave the troops verbal orders to “shoot at protesters.” He recounted to Human Rights Watch specific operations when these orders were implemented. He said:

On August 27 we were near a police hospital in Harasta. About 1,500 protesters came there. They requested the release of an injured protester who was inside the hospital. They held olive branches. They had no arms. There were 35 army soldiers and about 50 mukhabarat personnel at the checkpoint. We also had a jeep with a mounted machine-gun. When the protesters were less than 100 meters away, we opened fire. We had previously received the orders to do so from the Brigadier General. Five protesters were hit, and I believe two of them died.[53]

· “Abdullah,” a soldier with the 409th Battalion, 154th Regiment, 4th Division, said that his unit was deployed to Mo`adamiyeh, Douma, Abbassiyyin, and Dummar, areas in and just outside of Damascus. He said that two high-level commanders gave verbal orders to the troops to shoot at protesters:

We were told to shoot if civilians gathered in groups of more than seven or eight people. Commander of the 154th Regiment Brigadier General Jawbat Ibrahim Safi and divisional commander Major General Mohamed Ali Durgham gave us the orders before we went out. The orders were to shoot at gatherings of protesters as well as defectors, and to storm houses and arrest people.[54]

· “Mansour,” who served in Air Force Intelligence in Daraa, said that the commander in charge of Air Force Intelligence in Daraa, Colonel Qusay Mihoub gave his unit orders to “stop the protesters by all possible means,” which included the use of lethal force. Mansour said:

Our orders were to make the demonstrators retreat by all possible means, including by shooting at them. It was a broad order that shooting was allowed. When officers were present they would decide when and whom to shoot. If somebody carried a microphone or a sign, or if demonstrators refused to retreat, we would shoot. We were ordered to fire directly at protesters many times. We had Kalashnikovs and machine guns, and there were snipers on the roofs.[55]

· “Najib,” who was stationed in Daraa with the 287th Battalion, 132nd Brigade, 5th Division, said that the brigade commander verbally communicated the orders to use lethal force against protesters to the troops before a major military operation on April 25. He said:

Brigadier General Ahmed Yousef Jarad, the brigade commander, gathered us in the yard before we moved out. He told us to stop the people who were rioting by all means necessary. He said that the country needed to be cleaned of the protesters and said we should shoot at anything suspicious. He ordered us to use our PKT machine guns and DShK antiaircraft guns [Russian-made vehicle-mounted weapons] as well. Our general orders were to kill, destroy stores, crush cars in the streets, and arrest people.[56]

· “Habib,” an officer with the 65th Brigade, 3rd Division, told Human Rights Watch that his unit received initial orders at a briefing at their base in Douma in mid-March. According to Habib, Major General Naim Jasem Suleiman, the commander of the 3rd Division, and Brigadier General Jihad Mohamed Sultan, the commander of 65th Brigade, told the troops that they would need to fight armed groups “supported by Israel and the US” and that they had one month to stop the protests at any cost.[57]

Habib explained that his unit fell under the command of Imad Fahed Al Jasem during the April 25 operation in Daraa.[58] According to Habib, his unit also took orders from Brigadier General Ramadan Mahmoud Ramadan, the commander of the 35th Special Forces Regiment, in addition to the divisional and brigade commanders mentioned above.[59]

According to Habib, battalion commander Colonel Mohamed Khader personally gave them additional verbal instructions immediately before the invasion of Daraa:

Just before the operation, Colonel Mohamed Khader gave us about 30 minutes of instructions. As we were entering the town, we were supposed to shoot at anybody who shot at us. But after we entered, our orders were to shoot at anybody we saw, even if they were just sitting on a balcony.[60]

· “Salim,” an officer with the 46th Special Forces Regiment deployed to Idlib, said that Major General Fo’ad Hamoudeh, who had assumed command of the Idlib operation, told the forces to “stop the protesters at any cost” in the beginning of September.[61]

· “Mohamed,” a soldier with aerial defense unit MD 1010 deployed to Bukamal in the beginning of May, said that the commander of his unit, Colonel Issa Shibani made it clear that the unit’s “job was not to arrest people, but to kill.” According to the soldier, the commander gave verbal orders to “kill anyone putting up resistance, regardless of whether they are men, women, or children.”[62] Mohamed said that 35 to 40 people were killed during the first day of the operation as his unit entered Bukamal. A Special Forces commander Major General Bader Aqel gave the soldiers orders to pick up the bodies and hand them over to the mukhabarat.[63]

In some cases, the unit commanders provided clarifications to written orders, making orders to use lethal force more explicit. For example, “Tahir,” who served in the 691st Battalion of the Military Police, said that when the unit was deployed to accompany Special Forces on a mission to Daraa, the commander of his unit read out a written order from the commander of military police, General Mohamed Ibrahim Sha`ar (who became the Minister of Interior on April 14, 2011), saying that the unit was authorized to open fire “if attacked.” The battalion commander, the soldier said, then clarified the order, adding that “if anybody or anything comes your way, fire at them!”[64]

“Ameen,” a sniper with the Special Forces deployed to Homs in the beginning of May, also said that verbal orders sometimes differed from written orders. According to Ameen, Colonel Faisal Bya’i, commander of the 625th Special Forces Battalion, gave the snipers verbal orders “to kill or kill”— to kill the protesters or to kill defectors who disobeyed orders. He added:

On paper, it said “Stop the protesters,” but verbally he explicitly said, “Kill.” During normal days, at curfew, every moving object was a target. During the protests, the commanders gave us a specific number, or a percentage, of protesters who should be liquidated. For 5,000 protesters, for example, the target would be 15-20 people.[65]

“Ameen” said that two commanders from the 45th Regiment, Brigadier General Ghassan Afif and Brigadier General Mohamed Maaruf, had overall command of the operation in Homs at that time.[66]

Direct orders

More than half of the defectors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the commanders of their units or other officers gave direct orders on the spot to open fire at protesters or bystanders, and, in some cases, participated in the killings themselves. From the circumstances of the cases, it appears that the commanders should have known that the protesters were unarmed and did not present a significant threat to the soldiers.

Most of the defectors said that they tried to avoid killing the protesters, by aiming at their feet or firing in the air, but in some cases did not dare to disobey orders because they thought that they would be killed (see chapter below). A few took up arms against security agents and officers who ordered the killings, and many defected when they realized that they were ordered to shoot at unarmed protesters as opposed to the “armed gangs” they had been told to expect.

Homs Governorate

· “Said,” a soldier in the 990th Battalion, 134th Brigade, 18th Division, who participated in the operation in Talbiseh in May, said that Brigadier General Yousef Ismail, the commander of the 134th Brigade, gave them their standing orders, while Colonel Fo’ad Khaddour often gave them direct orders. He said that in early May, Khaddour and Ismail gave verbal orders to open fire at houses and people on roofs during a funeral in Talbiseh for several protesters killed the previous day. He said:

During the funerals, many people went to their roofs, shouting “Allahu Akbar!” [God is great!]. I heard Colonel Khaddour, who was at our checkpoint at the time, contact Brigadier General Yousef Ismail by radio. Khaddour told us to start firing, saying that anyone shouting “Allahu Akbar” from the rooftops was a terrorist. We were firing at the roofs and houses randomly, from BMPs [tracked armored infantry vehicles] and smaller weapons.

When Ismail later came to our checkpoint, he said, “End this at any cost; all ammunition you have is to be used against them.”[67]

· “Osama,” who served in the 555th Airborne Regiment, 4th Division, said that Brigadier General Jamal Yunes, commander of the 555th Regiment, gave them verbal orders to shoot at protesters during their deployment to Mo`adamiyeh, a neighborhood of Damascus. Osama said that he later found out that the orders came from Maher al-Assad, de facto commander of the 4th Division and President al-Assad’s younger brother. Osama said:

Initially, when the protest started, Brigadier General Jamal Yunes told us not to shoot. But then he received additional orders from Maher. He had some kind of paper that he showed the officers, and then the officers pointed their guns at us, and told us to shoot straight at the protesters. These officers later told me that the paper contained orders from Maher to “use all possible means.”[68]

· “Hisham,” who was also deployed to Mo`adamiyeh neighborhood in Damascus with the 555th Airborne Regiment, 4th division, said that Captain Khaldoun Ghalia, the commander of their company, gave them direct verbal orders to open fire on April 23.He said:

The commander gave us orders to shoot at anyone who refused to disperse. The protesters were chanting, “The people and the army are together.” When they approached, the captain gave orders to shoot. We tried to avoid killing people, and shot at their feet; about 20 people were injured.[69]

Hisham said that Captain Khaldoun Ghalia alsoverbally“gave orders to shoot right away to make them disperse,” when the company was deployed to disperse a night protest in Qadam neighborhood in Damascus at the beginning of September. Hisham said he saw people falling, but couldn’t tell how many since it was dark.[70]

· “Hani,” who served in the Special Operations branch of Air Force Intelligence, said that his unit was deployed to Mo`adamiyeh neighborhood in Damascus, together with the 4th Division, on April 15. He said:

We were all armed, with Kalashnikovs and machine guns. There were thousands of protesters. We started firing in the air, but the protesters wouldn’t disperse. Then Colonel Suheil Hassan gave orders to shoot directly at the protesters. He said, “So, they are challenging us?! Shoot them!” There were people injured and killed.[71]

Hani also said that Colonel Ghassan Ismail, commander of the Special Operations unit, gave verbal orders to shoot at the protesters when his unit was sent to suppress a protest in Daraya neighborhood during another operation in June, together with the 4th Division. According to Hani, his orders were “Don’t fire in the air; fire directly [at the protesters].”[72]

Daraa Governorate

· “Amjad,” who was deployed to Daraa with the 35th Special Forces Regiment, said that he received direct verbal orders from his commander to open fire at the protesters on April 25. He said:

The commander of our regiment, Brigadier General Ramadan Mahmoud Ramadan, usually stayed behind the lines. But this time he stood in front of the whole brigade. He said, “Use heavy shooting. Nobody will ask you to explain.” Normally we are supposed to save bullets, but this time he said, “Use as many bullets as you want.” And when somebody asked what we were supposed to shoot at, he said, “At anything in front of you.” About 40 protesters were killed that day. [73]

· “Habib,” who was also deployed to Daraa in April, with the 65th Brigade, 3rd Division, said that his unit received direct verbal orders from the battalion commander, Colonel Mohamed Khader, to open fire at the protesters on at least two occasions. Both incidents took place between April 13 and 25. Habib said:

The first time, Colonel Khader and the mukhabarat were just behind us. Khader had given general orders to shoot before the operations. When the protesters started walking toward us, he gave orders to open fire.

About a week later, on a Friday, several thousand protesters gathered at the intersection near the airport highway. Our commander called us to come to the square to provide support. He said we had to end the protest by all possible means within an hour, to prevent any media coverage. We used smoke bombs, and people dispersed, but then they gathered again. Then the mukhabarat opened fire. We were shooting as well, but tried to shoot in the air. Seven or eight people were killed, about 30 were injured, and about a hundred detained.[74]

· “Hossam,” who served in Air Force Intelligence in Daraa, said that at some point in April, his unit was ordered to enter the Omari mosque in Daraa, which served as a gathering point and makeshift hospital for the protesters. He said that Colonel Majed Darras gave the unit verbal orders to open fire and as a result 12 people were killed.[75]

· “Fouad,” who was deployed to Daraa with the 3rd Battalion, 127th Regiment, 15th Division, said:

I was ordered to shoot at protesters many times, but I shot in the air since I knew these were ordinary people and not terrorists. Those who directly ordered us to shoot were Colonel Imad Abass and Major Ziyad Abdel Shaddoud. They said that we were fighting terrorist groups and that we had to get rid of them. They told us to kill anybody who was outside in the street without asking who they were.[76]

· “Ibrahim,” a sergeant in the 59th Battalion, 5th Division, said that his unit received direct verbal orders to fire at protesters in al-Herak:

Several thousand protesters had gathered near the stadium in al-Herak in the afternoon on August 7. They started walking towards our checkpoint where we had 150-200 soldiers and security agents. They were shouting, “down with the regime!” but they were not armed—no weapons, rocks, or sticks.

There was an imam among the protesters. Brigadier General Mohsin Makhlouf, who was commanding the operation in al-Herak, told the imam that he needed to stop the protesters, but he didn’t, and said that the protesters were peaceful. Then Briagider General Makhlouf and Brigadier General Ali Dawwa ordered us to shoot at the protesters.[77]

Ibrahim also said that in a separate incident, when the unit was deployed at a checkpoint between Izraa and Bosr al-Harir, Major General Suheil Salman Hassan, commander of the 5th Division, gave them verbal orders “to shoot at the protesters if they come near.”[78]

Latakia Governorate

· “Faysal,” a soldier with Coastal Guard 157th Battalion based in Latakia, said that commander Colonel Hassan Kher Bek gave verbal orders to open fire when his unit participated in an offensive on the Palestinian Sands area near Latakia. According to Faysal, Colonel Kher Bek said “Any moving object—a car, a person—is a target.”[79]

Direct participation in killings

Some defectors said that unit commanders not only ordered the killings but also killed people themselves. “Afif,” a career officer who used to serve in the Presidential Guard and took part in the protests in Nawa, said that the military brought in a new group of forces, including the 171st Battalion, 112th Brigade, when the protests restarted in the town in the beginning of August. Afif said he saw their commander, Colonel Sami Abdulkarim Ali, fire at the protesters from his Kalashnikov and kill one person, 16-year-old Omran Riad Salman.[80] Human Rights Watch reviewed footage posted on YouTube that purports to show the body of a young man identified as Omran Riad Salman killed on August 3 in Nawa.[81]

The majority of the defectors also cited incidents where they received direct orders to open fire from mukhabarat or other officers stationed at the same checkpoints, whose names they often did not know because they were from different units.

For example, “Wassim,” a soldier from 76th Brigade, 9th Division, told Human Rights Watch that on April 28, 2011, he was sent to al-Tal to man a checkpoint on the way from al-Tal to Damascus, with orders to use all means necessary, including lethal force, to prevent the protesters from proceeding to Damascus. He said:

After the noon prayer, the protesters—about 3,500 people, mostly youth—started approaching. They took off their shirts to show that they were unarmed. When they approached the first checkpoint, soldiers started shooting, some in the air and some, it seemed, in the crowd. There were no warnings, no tear gas. It was mainly the army, and mukhabarat was observing. The army commanders were giving orders, and the mukhabarat was there to ensure that the soldiers followed them.

People were approaching from different sides, and one guy came up to me and screamed, “If you are a man, shoot me!” The same moment, a mukhabarat guy next to me shot him in the shoulder, at close range, and tried to arrest him. His mother approached us and said, “Let him go; take me instead!,” and a mukhabarat guy in civilian clothes in front of me shot the guy point blank and killed him, in front of his mother. I don’t know how old the guy was; he looked like a teenager. The protesters managed to take his body away.[82]

“Hassan,” a soldier who was stationed at a checkpoint near the army base in Douma, another suburb of Damascus, said: “Mukhabarat officers, who were also at the checkpoint, told us to shoot at protesters if they tried to approach. They never reached our checkpoint though; soldiers at the previous checkpoint had opened fire, and people had dispersed.”[83]

“Faysal,” a soldier with the 157th Coastal Guard Battalion who was stationed at a checkpoint near Latakia, on the road from Tishreen University, a public university situated in Latakia, to Aleppo, described an episode where the mukhabarat and soldiers opened fire at a civilian car:

Our orders were also to shoot at any car that wouldn’t stop. One day, I woke up to the sounds of gunfire, and when I got out, I saw mukhabarat and soldiers firing at a minibus. It was around 3 a.m.; it must have been some kind of emergency. There was a man driving the minibus, and his wife sat next to him holding a child. The minibus stopped, and the woman got out, screaming, “What did you do?! You killed him!” The man was shot in the back, and he was unconscious. There were many bullet holes in the bus, but I saw only one bullet wound on the body. We got a taxi, and sent all three of them off.

The officers from another checkpoint then came to inquire. One of the guys from my battalion started explaining what happened, but a shabeeha guy interrupted, saying, “He was armed.” My fellow soldier said, “no,” but the shabeeah repeated, in a threatening voice, “He was armed.” We couldn’t argue with them; mukhabarat backed them up. [84]

“Ziyad,” a soldier with the 324th Battalion, 167th Brigade, 18th Division, who was based at a checkpoint in Rastan, described a similar incident that resulted in the killing of three persons. He said:

It was in the end of July, just before Ramadan. It happened in front of me, around lunch time. There was a car that was trying to get away from the protest, and get on the road. It was moving closer to the checkpoint, and a mukhabarat officer said, “Fire!” One guy from my battalion raised his Kalashnikov and shot, and others did too.

The car stopped, a man got out of the passenger seat to get the kid who was in the back, and got shot right there. The driver was killed on the spot, and another passenger was also killed. We searched the car for weapons, and didn’t find any, but saw a three-year-old kid in the back. He was alive. We gave the bodies to mukhabarat; they drove them away in a car, and left the boy there. I assume some of the protesters took him away; the protest was winding down at that point.[85]

Arbitrary Detention and Torture

According to information collected by Human Rights Watch, the Syrian security forces have conducted a widespread and systematic campaign of arbitrary arrests and torture of detainees across Syria since the beginning of anti-government protests in March 2011.[86]

Information provided by the defectors in this report, many of whom personally participated in arrests and ill-treatment, further corroborates these findings. The defectors described large-scale arbitrary arrests during protests and at checkpoints, as well as “sweep” operations in residential neighborhoods in a number of governorates.

Defectors who participated in such operations said that they conducted the arrests either on the basis of lists of wanted individuals that they received from their commanders or more general orders to arrest the protesters or residents of specific neighborhoods.

Most of these arrests appear to have been conducted by the intelligence agencies, while the military provided support during the arrest and transportation of detainees. According to the defectors, arrests were routinely accompanied by beatings and other ill-treatment, which the commanders ordered, authorized, or condoned. Those defectors who worked in or had access to detention facilities told Human Rights Watch that they witnessed or participated in the torture of detainees.

Large-scale arbitrary arrests and looting

The number of people arrested since the beginning of the protests is impossible to verify. As of November 23, the VDC had documented more than 15,500 arrests.[87] The real number is likely much higher.

A member of the Air Force Intelligence Special Operations branch told Human Rights Watch that he believed the overall number of detainees to be over 100,000, many of whom had been released again, judging by information accessible to him. He said that by the time he defected at the end of August, there were at least 5,000 detainees at the detention facility at his branch alone.[88] Another witness, “Mansour,” who served in Air Force Intelligence in Daraa independently gave Human Rights Watch a similar figure, saying that his branch arrested about 5,000 people during the three months that he served in Daraa (April through June), about 600 of whom were released at different times thereafter.[89]

Information from the defectors about sweep operations in which they participated lends some support to the high number of detainees provided by the intelligence officers. As the examples below illustrate, security forces regularly detained dozens of individuals during protests; “sweep” operations, which usually took place following protests or after the army invaded a town, resulted in hundreds of arrests. The raids were often accompanied by looting and destruction of property that interviewees said officers condoned.

Daraa Governorate

· “Said,” who was deployed to Talbiseh with the 134th Brigade, 18th Division, said that after the military moved into the town in early May, the mukhabarat and army started conducting daily raids, arresting “anyone older than 14 years, sometimes 20, and sometimes a 100 people.”[90] Said also said that the arrest raids in which he participated, authorized by the mukhabarat and the military, were accompanied by “brazen looting” and burning of shops.[91]

· “Bassam,” who served in a civil defense unit that operated under the command of the 18th Division, said that his unit conducted sweep operations in Talbiseh at the beginning of August, which resulted in the arrest of 200 people, including five women, and in Rastan two days later, where they arrested about 300 people.[92]

· “Habib,” a soldier with the 65th Brigade, 3rd Division, described arbitrary arrests and looting during the raids in Daraa after the army took over the city at the end of April:

When we broke into a house, we would just crash the door without knocking and detain the men—one, two, sometimes more—randomly. We humiliated them in front of their families. Our group normally included ten mukhabarat guys, shabeeha, and two soldiers. Security and soldiers took TV sets, videos, and other goods. Sometimes, we would steal cars to drive away the loot.[93]

Tartous Governorate

· “Mousa,” a soldier who was also deployed in the Banyas area with the 45th Special Forces Regiment, estimated that together with intelligence agencies his unit arrested several thousand people in Banyas alone in April and May. He said that the soldiers brought all of the detainees to the main square in town where they handed them over to the mukhabarat.[94] Two other military defectors who were deployed to Banyas, Bayda, and Basateen in April and May as part of other Special Forces units, also described massive looting, arrests of relatives of wanted individuals, beating of detainees, and harassment of women that took place in all of these towns. One of them, “Zahir,” said:

In Bayda, we broke the doors and took whatever we wanted. The mukhabarat was arresting people; in one area, they arrested ten old men to force their children to turn themselves in. The same continued in Banyas, where we went the next days. In Basateen, we looted everything, both my unit and others. We always took money, and then whatever was there: gold, mobiles, electronics, and sometimes even women’s clothing. I saw the mukhabarat and some soldiers also touching women inappropriately, pretending to be looking for bombs and explosives.[95]

Damascus Governorate

· “Fadi,” a soldier with the 292nd Battalion, Presidential Guard, said that Colonel Murad `Isa gave his unit orders to raid houses in the Mezzeh area in Damascus in mid-April “to extract armed terrorists.” He said the unit provided support to mukhabarat personnel who went inside and arrested about 15 people, none of whom seemed to have weapons.[96] He said that such raids took place every Friday, in Damascus and the suburbs, and resulted in dozens of arrests each time.

· “Hisham,” a soldier with the 555th Airborne Regiment, 4th Division, said that his unit participated in multiple raids in various neighborhoods in Damascus, including Daraya, Sakba, Qadam, Qabun, and Zamalka, from April to September. All of the raids resulted in dozens, and some in hundreds, of arrests. He said he particularly remembered two of the raids in early September, in the Qadam and Qabun neighborhoods. He said:

At dawn, 15 buses with Air Force Intelligence arrived and started raiding houses in Qadam. We manned checkpoints and grabbed anybody who tried to run away. Three of my mom’s cousins, who live in the area, were arrested that night.

Several days later, commanders took us to another area, Qabun. There they told us to conduct raids on the houses as well. We had a list of 900 wanted people. We were there for two days, and arrested about 800 people from that neighborhood. We were at checkpoints preventing escapes. Each checkpoint would receive an updated list, so I knew the numbers.[97]

Deir al-Zor Governorate

· “Mohamed,” who was deployed in Bukamal as part of aerial defense unit MD 1010, said that the commanders instructed the soldiers and security services to arrest family members to make the wanted individuals surrender:

I participated in such raids many times. One time, we went to a house, looking for two wanted men. Another soldier and I were waiting outside. The two men were not at home. We took money and gold, and arrested two women and three kids: two boys, ages about 15 and 10, and a little girl. The mukhabarat hooded the women, and punched them, saying, “We are not going to let you go until the men return, and now you’ll see what ‘freedom’ is like.”[98]

Mohamed said that during the invasion of the town, the soldiers “looted stores and burned pharmacies.”[99]

Hama Governorate

· “Ali,” who was based in Hama in June with the 11th Division, said that soldiers from his unit were involved in the arrests and large-scale looting in the city, taking anything of value, and that he personally saw one of the officers “taking a fridge from the house and loading it into an army truck.”[100]

Defectors who used to man checkpoints told Human Rights Watch that the lists of “wanted” individuals that they received included anywhere from 200 to more than 1,000 names. They said they were supposed to arrest the people on the lists, but that they often arrested those who were not on the list for different reasons such as “suspicious looks,” or “talking back to the soldiers.”