Summary

The guards hung me by my wrists from the ceiling for eight days. After a few days of hanging, being denied sleep, it felt like my brain stopped working. I was imagining things. My feet got swollen on the third day. I felt pain that I have never felt in my entire life. It was excruciating. I screamed that I needed to go to a hospital, but the guards just laughed at me.

—Elias describing how he was tortured in Branch 285 of the Department of General Intelligence in Damascus

Since the beginning of anti-government protests in March 2011, Syrian authorities have subjected tens of thousands of people to arbitrary arrests, unlawful detentions, enforced disappearances, ill-treatment, and torture using an extensive network of detention facilities, an archipelago of torture centers, scattered throughout Syria.

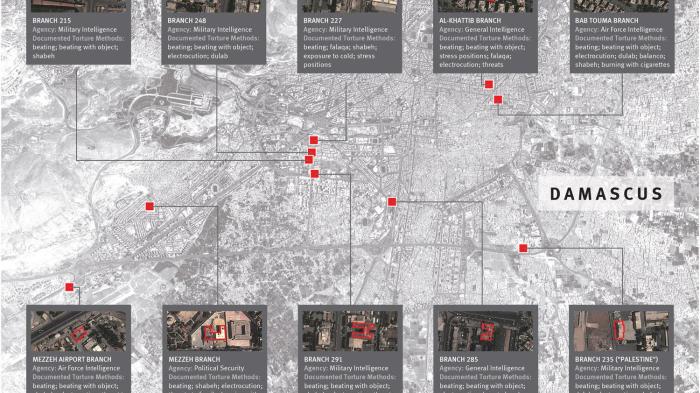

Based on more than 200 interviews with former detainees, including women and children, and defectors from the Syrian military and intelligence agencies, this report focuses on 27 of these detention facilities. For each facility, most of them with cells and torture chambers and one or several underground floors, we provide the exact location, identify the agencies responsible for operating them, document the type of ill-treatment and torture used, and name, to the extent possible, the individuals running them. The facilities included in this report are those for which multiple witnesses have indicated the same location and provided detailed descriptions about the use of torture. The actual number of such facilities is likely much higher.

In charge of Syria’s network of detention facilities are the country’s four main intelligence agencies, commonly referred to collectively as the mukhabarat:

- the Department of Military Intelligence (Shu`bat al-Mukhabarat al-`Askariyya);

- the Political Security Directorate (Idarat al-Amn al-Siyasi);

- the General Intelligence Directorate (Idarat al-Mukhabarat al-`Amma); and

- the Air Force Intelligence Directorate (Idarat al-Mukhabarat al-Jawiyya).

Each of these four agencies maintains central branches in Damascus as well as regional, city, and local branches across the country. In virtually all of these branches there are detention facilities of varying size.

Syria’s intelligence agencies have historically operated independently from each other with no clear boundaries to their areas of jurisdiction. Relying on the country’s overbroad emergency law, the mukhabarat has a long history of detaining people without arrest warrants and denying detainees other due process safeguards. Lifting the emergency law in April 2011 changed little in practice. Legislation limiting the time that a person can be lawfully held in detention without judicial review to 60 days for certain crimes, simultaneously introduced in April 2011, does not meet the requirement in international law that judicial review should take place “promptly.” Furthermore, several former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had been held without judicial review even longer than the 60 days permitted by Syrian law.

To manage the thousands of people detained in the context of anti-government demonstrations, the authorities also established numerous temporary unofficial holding centres in places such as stadiums, military bases, schools, and hospitals where the authorities rounded up and held people during massive detention campaigns before transporting them to branches of the intelligence agencies.

All of the witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch described conditions of detention—extreme overcrowding, inadequate food, and routine denial of necessary medical assistance—that would by themselves amount to ill-treatment and, in some cases, torture. But almost all the former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch also said they had been subjected to torture or witnessed the torture of others during their detention. Interrogators, guards, and officers used a broad range of torture methods, including prolonged beatings, often with objects such as batons and wires, holding the detainees in painful stress positions for prolonged periods of time, often with the use of specially devised equipment, the use of electricity, burning with car battery acid, sexual assault and humiliation, the pulling of fingernails, and mock execution. Altogether Human Rights Watch documented more than 20 different methods of torture used in Syria’s archipelago of torture centers.

© 2012 Human Rights Watch

Most of the detainees interviewed said they had been subjected to several forms of torture, often inflicted with escalating levels of pain. At times detainees were forced to remain naked or in their underwear while they were tortured. Several former detainees interviewed for this report told Human Rights Watch that they had witnessed people dying from torture in detention. Human Rights Watch also received information about deaths in custody from families or friends of the victims.

A former intelligence officer described to Human Rights Watch the various methods used at the Air Force Intelligence base at the Mezzeh airport in Damascus:

The mildest form of torture is hitting people with batons on their arms and legs and not giving them anything to eat or drink. Then they would hang the detainees from the ceiling by their hands, sometimes for hours or days. I saw it while I was talking to the interrogators. They used electric stun-guns and an electroshock machine, an electric current transformer. It is a small machine with two wires with clips that they attach to nipples and a knob that regulates the current. In addition, they put people in coffins and threatened to kill them and close the coffin. People were wearing underwear. They pour hot water on people and then whip them. I’ve also seen drills there, but I’ve never seen them being used. I’ve also seen them using martial art moves, like breaking ribs with a knee kick. They put pins under your feet and hit you so that you step on them. I also heard them threatening to cut off the detainees’ penises.

A 31-year-old detainee who was detained in Idlib governorate in June described to Human Rights Watch how intelligence agents tortured him in the Idlib Central Prison:

They forced me to undress. Then they started squeezing my fingers with pliers. They put staples in my fingers, chest, and ears. I was only allowed to take them out if I spoke. The nails in the ears were the most painful. They used two wires hooked up to a car battery to give me electric shocks. They used electric stun-guns on my genitals twice. I thought I would never see my family again. They tortured me like this three times over three days.

While most of the torture victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch were young men aged between 18 and 35, interviewed victims also included children, women, and elderly individuals. Defecting members of the intelligence agencies told Human Rights Watch that they either witnessed or participated in the torture and ill-treatment of detainees, corroborating accounts by former detainees.

Human Rights Watch has documented the use of torture and ill-treatment in the following detention facilities:

|

Agency |

Name of Branch |

City |

Head of Branch |

|

Military Intelligence |

Branch 215 |

Damascus |

Brig. Gen. Sha’afiq |

|

Military Intelligence |

Branch 227 |

Damascus |

Maj. Gen. Rustom Ghazali |

|

Military Intelligence |

Branch 291 |

Damascus |

Brig. Gen. Burhan Qadour (Replaced Brig. Gen. Yousef Abdou in May 2012) |

|

Military Intelligence |

Branch 235 (“Palestine”) |

Damascus |

Brig. Gen. Muhammad Khallouf |

|

Military Intelligence |

Branch 248 |

Damascus |

Not identified |

|

Military Intelligence |

Branch 245 |

Daraa |

Col. Loai al-Ali |

|

Military Intelligence |

Aleppo Branch |

Aleppo |

Not identified |

|

Military Intelligence |

Branch 271 |

Idlib |

Brig. Gen. Nawfel al-Hussein |

|

Military Intelligence |

Homs Branch |

Homs |

Muhammad Zamreni |

|

Military Intelligence |

Latakia Branch |

Latakia |

Not identified |

|

Air Force Intelligence |

Mezzeh Airport Branch |

Damascus |

Brig. Gen. Abdul Salam Fajr Mahmoud (director of investigative branch) |

|

Air Force Intelligence |

Bab Touma Branch |

Damascus |

Not identified |

|

Air Force Intelligence |

Homs Branch |

Homs |

Brig. Gen. Jawdat al-Ahmed |

|

Air Force Intelligence |

Daraa branch |

Daraa |

Col. Qusay Mihoub |

|

Air Force Intelligence |

Latakia Branch |

Latakia |

Col. Suhail Al-Abdullah |

|

Political Security |

Mezzeh Branch |

Damascus |

Not identified |

|

Political Security |

Idlib Branch |

Idlib |

Not identified |

|

Political Security |

Homs Branch |

Homs |

Not identified |

|

Political Security |

Latakia Branch |

Latakia |

Not identified |

|

Political Security |

Daraa Branch |

Daraa |

Not identified |

|

General Intelligence |

Latakia Branch |

Latakia |

Brig. Gen. Khudr Khudr |

|

General Intelligence |

Branch 285 |

Damascus |

Brig. Gen. Ibrahim Ma’ala (Replaced Brig. Gen. Hussam Fendi in late 2011) |

|

General Intelligence |

Al-Khattib Branch |

Damascus |

Not identified |

|

General Intelligence |

Aleppo Branch |

Aleppo |

Not identified |

|

General Intelligence |

Branch 318 |

Homs |

Brig. Gen. Firas Al-Hamed |

|

General Intelligence |

Idlib Branch |

Idlib |

Not identified |

|

Joint |

Central Prison - Idlib |

Idlib |

Not identified |

In the vast majority of detention cases documented by Human Rights Watch, family members could obtain no information about the fate or whereabouts of the detainees and detainees were not allowed any contact with the outside world. Many of the detentions can therefore be qualified as enforced disappearances.

Human Rights Watch calls on the UN Security Council to ensure accountability for these crimes by referring the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court. Human Rights Watch also calls on the United Nations Security Council to ensure that the Syrian government grants recognized international detention monitors access to all detention facilities, including those mentioned in this report.

Recommendations

To the UN Security Council

- Demand that Syria grant recognized international detention monitors access to all detention facilities, official and unofficial, without prior notification, including those mentioned in this report;

- Ensure that the UN supervisory mission (UNSMIS ) deployed to Syria includes a properly staffed and equipped human rights component with staff with expertise in detention monitoring that is able to identify the use of arbitrary detention, visit detention centers, and to safely and independently interview victims of human rights abuses while protecting them from retaliation. The mission should include among its personnel people trained to identify gender-based violence and other gender-specific human rights violations and personnel trained to work with children;

- Demand that Syria enforce its commitment under point 4 of the Annan plan by releasing all arbitrarily detained persons, “including especially vulnerable categories of persons, and persons involved in peaceful political activities,” and provide without delay “a list of all places in which such persons are being detained”;

- Refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court (ICC);

- Adopt targeted sanctions on officials credibly implicated in abuses;

- Require states to suspend all military sales and assistance, including technical training and services, to the Syrian government, given the real risk that the weapons and technology will be used in the commission of serious human rights violations;

- Demand that Syria cooperate fully with the UN Human Rights Council Commission of Inquiry and with the UNSMIS;

- Demand access for humanitarian missions, foreign journalists, and independent human rights organizations.

To All Countries

- Acting individually, or jointly through regional mechanisms where appropriate, adopt targeted sanctions against Syrian officials credibly implicated in the ongoing serious violations of international human rights law;

- Under the principle of universal jurisdiction and in accordance with national laws, investigate and prosecute members of the Syrian senior military and civilian leadership suspected of committing international crimes;

- Call for the UN Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to the ICC, as the forum most capable of effectively investigating and prosecuting those bearing the greatest responsibility for abuses in Syria.

To the Arab League

- Acting individually and jointly, maintain and strengthen targeted sanctions against Syrian officials credibly implicated in the ongoing grave, widespread, and systematic violations of international human rights law in Syria since mid-March 2011;

- Support a strong UNSMIS human rights component (as described in the recommendations above);

- Call for the UN Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to the ICC.

To Russia and China

- Support UN Security Council action on Syria (as described in the recommendations above), including referring the situation to the ICC;

- Suspend all military sales and assistance to the Syrian government, given the real risk that weapons and technology will be used in the commission of serious human rights violations;

- Condemn in the strongest terms the Syrian authorities’ systematic violations of human rights;

To the Syrian Government

- Release all arbitrarily detained persons, “including especially vulnerable categories of persons, and persons involved in peaceful political activities,” and provide without delay “a list of all places in which such persons are being detained” in accordance with point 4 of the Annan plan.

- Immediately halt the practice of enforced disappearance, arbitrary arrest and detention, and the use of torture;

- Conduct prompt, thorough, and objective investigations into allegations of arbitrary detention, use of torture, enforced disappearances, and deaths in custody, including the ones described in this report, and bring the perpetrators to justice;

- Suspend members of the security forces against whom there are credible allegations of human rights abuses, pending investigations;

- Annul Legislative Decree No. 14, of January 15, 1969, and Legislative Decree 69, which provide immunity to members of the security forces by requiring a decree from the General Command of the Army and Armed Forces to prosecute any member of the internal security forces, Political Security, and customs police;

- Publish lists of all detainees;

- Provide immediate and unhindered access for recognized international detention monitors to all detention facilities, official and unofficial, without prior notification, including those mentioned in this report;

- Provide all UNSMIS staff with the necessary permissions, including visas to Syria or use of UN air assets, to carry out their mandate;

- Provide immediate and unhindered access and cooperation to independent observers, journalists, and human rights monitors, including the UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights; the UN Human Rights Council Commission of Inquiry on Syria; and the special rapporteur on Syria.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch has documented the systematic use of torture by the Syrian authorities since anti-government demonstrations broke out in March 2011.[1] This report is based on more than 200 interviews with former detainees and defectors from the Syrian military and intelligence agencies. The interviews were conducted in Syria and in neighboring countries that host refugees from Syria—Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, and Turkey—between April 2011 and May 2012.

Interviews were conducted in Arabic or in English using an interpreter. Because of the very real possibility of reprisals we have withheld the names of the victims and witnesses we interviewed, using instead pseudonyms to identify the sources of information.

To establish the location of the detention facilities, we asked victims, witnesses, and defectors to indicate the building where they were held, visited, or served using satellite imagery. Some detainees were not able to identify the facility in which they were held because they were blindfolded. Others, however, were able to do so, either because they were detained close to where they lived and knew the area well, or because they were told by guards and fellow detainees where they were being held, or because they were not blindfolded when they were brought to the facility or released. In a few cases, detainees were asked to come back to the same detention facility for further interrogation upon release.

We also asked former detainees and defectors to describe the facilities in detail and to draw the layout of the floors where they were detained and interrogated. This helped us to corroborate information from different witnesses.

We also asked former detainees and defectors to name those in charge of these detention facilities. In some cases, it was possible to corroborate information through independent interviews with two or more witnesses or public sources. However, given the secrecy surrounding the Syrian intelligence services (mukhabarat), names of commanders and others in authority and command responsibility might be further clarified as more information comes to light.

The detention facilities included in this report are those for which several sources described having witnessed or experienced the use of torture and ill-treatment. We have only provided the location of facilities that were identified by two or more people.

I. Arrest, Detention, and Torture in Syria

Arbitrary Arrests and Unlawful Detention

Given the limited access for independent observers and the near-complete secrecy surrounding detentions and detention facilities in Syria, it is virtually impossible to establish how many people have been detained since demonstrations broke out in March 2011. As of June 22, 2012, the Violations Documentation Center (VDC), a Syrian monitoring group working in coordination with the Local Coordination Committees (LCC), a network of Syrian activists, had documented over 25,000 detentions.[2] The actual number is likely much higher.

Most of the detentions documented by Human Rights Watch were carried out by the intelligence services (mukhabarat), often assisted by the military, during and immediately following anti-government protests; in the course of large-scale house-to-house “sweep” operations; and at checkpoints on roads. Riot police (Hafz al-Nizam), the army, and, in some cases, pro-government militias also detained people, but often these detainees were eventually transferred to the mukhabarat.

Security forces also raided the homes of “wanted” individuals and, in some cases, when these persons were not at home, detained their relatives instead. The raids were often accompanied by looting and destruction of property, and by beatings and other ill-treatment of the detainees. As documented in previous Human Rights Watch publications, these actions were usually ordered, authorized, or condoned by the commanding officers.[3]

According to witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the security forces conducting the arrests did not introduce themselves, did not provide any legal justification for the arrest, and did not inform the detainees as to where they were being taken. Following the arrests, the detainees were usually brought to local detention facilities—police stations, local branches of one of the intelligence agencies, or ad-hoc facilities such as stadiums, schools, facilities belonging to the youth branch of the Baath party (locally referred to as Tala’e`), or hospitals. Following initial interrogation and collection of personal data, the security forces typically transferred the detainees to larger detention facilities located in regional centers such as Damascus, Homs, Idlib, Latakia, Daraa, and Hama.

Most of the detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch spent anywhere from a few days to several months in detention. In most cases, detainees were held in more than one detention facility. It was not uncommon for detainees to be transferred to four or five detention facilities run by different intelligence agencies during their detention, being subjected to torture, the deliberate infliction of severe pain, in several of them.

In a typical example, security forces detained thirty-one-year old Khalil during a protest in a town in the Idlib governorate on June 29, 2011. They first took him to the local police station where police officers interrogated him three times during the night following his arrest, kicking and beating him. The next day security forces transferred Khalil to the central prison in Idlib, where he initially spent 16 days on the third floor, being subjected to severe torture by Political Security officers who had taken over the floor. Political Security officers then transferred him to a Military Intelligence facility located in the basement of the prison, where the torture continued. After 13 days in Military Intelligence custody in Idlib, Khalil was transferred to Damascus where he was held in Military Intelligence Branch 215 for five days, in Branch 291 for six days, and then in Branch 248 before he was eventually released, about two months after his detention.[4]

Some detainees were released without any formal procedure, when the interrogators eventually told them that they were free to go; others were taken to court and seen by a judge and either charged and released on bail, or simply released. More than half of the former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch were released without seeing a judge or having any formal charges brought against them. Human Rights Watch does not know how many people were sentenced to prison terms after their detention.

The vast majority of detention cases documented by Human Rights Watch can be qualified as enforced disappearances. In international law this is when state agents or other persons acting with the support of the state detain someone and then refuse to acknowledge the detention, or conceal his or her fate or whereabouts.[5] In most of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the detainees’ families had no information about their fate or whereabouts for weeks or, in some cases, months following the arrest, despite their inquiries with various intelligence agencies. The authorities did not allow detainees to have any contact with the outside world and left their families wondering whether their detained relatives were alive or dead.

Widespread or systematic enforced disappearances, carried out as part of a state policy, can constitute a crime against humanity.[6]

Conditions in Detention

All of the witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch described conditions in these detention facilities that by themselves amount to ill-treatment and, in some cases, torture.

In all of the facilities that witnesses described to Human Rights Watch, the detainees were held in overcrowded cells. Former detainees usually distinguished between what they called common cells and individual cells. The size of the common cells varied, measuring up to 70 square meters. For example, two former detainees told Human Rights Watch that a common cell measuring about 20 square meters in Military Intelligence Branch 291 in Damascus held 60-75 people.

Former detainees explained to Human Rights Watch that what they called individual cells were often small rooms measuring one to two square meters, many with a hole in the middle of the ground for a toilet. While in some cases former detainees reported being held alone in such cells most of the detainees said that these individual cells usually held several people. Both in the common and individual cells, the overcrowding was such that in many cases the detainees could only stand inside their cells, or had to take turns sleeping.

Hatem, who was detained in late September 2011 in a branch of the General Intelligence Directorate in Kafr Souseh, Damascus, told Human Rights Watch,

In the first three days I was in a group cell. We were around 65 people in the cell which was 3.5 by 3 meters. While in that cell I stayed standing for three days. When I wanted to sleep I would lean on the wall and sleep. The bathroom was in the cell. After the first three days they moved me to a solitary cell. We were five people in that cell. It was one by two meters. In the group cell that had around 65 people. Because they couldn’t sleep and had to stand all the time, people started to go crazy, to hallucinate. There was a group of five or six people in my group cell that started going crazy. One time some people were sitting, and sleeping in the cell, and there was one person hallucinating who started peeing on the people as they are sleeping. Imagine![7]

The majority of former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were blindfolded and handcuffed most of the time during their detentions, and some said they were kept naked for several days.

All the former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported being deprived of proper food (a commonly described meal was a piece of stale bread, half an egg, or a tomato, provided once a day), potable water, and regular access to a toilet.

Samir, who was detained in Military Intelligence Branch 235 (known as the “Palestine Branch”) in Damascus from July to September 2011, told Human Rights Watch,

They brought me down to where the cells are and put me in a room that measured 2 by 1.5 meters. The ceiling was not high. They left me there by myself. I stayed in this cell the whole time I was detained. The cell had every kind of filth, cockroaches, fleas, the smell of dirt and mold. There was no toilet. There was just an old large Pepsi bottle filled with urine. On the floor there was a flimsy mattress with an unreal smell … There was no light and [when I entered] no food and no water. [You would] hear the sound of torture, beatings, people being sworn at, humiliated, it was routine. They let you go to the toilet two times a day. You just took your Pepsi bottle and emptied it and there was another bottle for water, which you filled. There was no showering and no soap. For 61 days I did not shower once. After a while, you get used to it.

There were three meals a day, but their way of distributing it was very bizarre. They distributed the bread on the floor. In the metal door of the cell there was a small vent for air. They threw the bread in through this vent. The bread was either dough or burnt entirely. We would only get stale bread. They would serve the food in old empty halaweh [a sugar and sesame sweet] containers ... The guard that distributed the bread at lunch yelled at you to stand at the door and to put out your plate to get the food. Then he throws the liquid, the bulgar wheat—it’s all dirt—through the vent. He throws it, some lands on the floor, some on the plate, you don’t know where. This is between 12 and 2 o’clock. At 4 p.m. you go to the bathroom. They give each person one potato for his dinner. At night there is no other food. The second time you go to the bathroom is at 6 a.m. You go to the bathroom and the prison guard, so as not to tire himself out, has the food at the door of the bathroom and gives it to you on the way out. It is four olives and a small spoon of jam or sometimes half an egg or some halaweh, but the worst kind of halaweh.[8]

Former detainees also said that there was virtually no medical assistance available to the detainees in many detention facilities, even to those who sustained injuries or bullet wounds during their arrest, or suffered from chronic conditions. Several witnesses told Human Rights Watch that they witnessed the deaths of fellow detainees from complications caused by lack of medications they required for diabetes or a heart condition.

Jalal, a former detainee in the Central Prison in Idlib, for example, told Human Rights Watch that one of the detainees died because of lack of medical treatment in July 2011:

One guy had diabetes. We kept telling the guards to get him medical care, but they would just take him out and beat him up. For a week he couldn’t eat or stand up. We had to carry him to the bathroom. And then he went into diabetic shock. He said his prayers and then he just died. As he was saying his prayers another prisoner realized that he was dying and started kicking the door. But the guards just took the guy out who kicked the door and beat him. They dropped the dead man’s body on the floor outside the cell and called the nurse who confirmed that he had died.[9]

Systematic Use of Torture and Deaths in Custody

Almost all the former detainees interviewed told Human Rights Watch that they had been subjected to torture, meaning the deliberate infliction of severe pain, during their detention and witnessed the torture of others. Defectors from the intelligence agencies, who either witnessed or participated in the torture and ill-treatment of detainees, corroborated these accounts.

The most severe torture took place during interrogation sessions, often in separate interrogation or torture rooms, or in corridors and hallways in some of the smaller detention facilities. During these sessions, interrogators and officers usually wanted the detainees to confess to having participated in demonstrations, provide names of other demonstrators and organizers, admit to owning and having used weapons, and in some cases provide information about alleged funding of demonstrations from abroad.

But many former detainees interviewed also believed that a main reason for the use of torture was not just to obtain information, but to punish and intimidate the detainees.

Interrogators, guards, and officers used a wide range of torture methods, including prolonged beatings, often with objects such as batons and cables, holding the detainees in stress positions for prolonged periods of time, and use of electricity and electric shocks. At times detainees were forced to remain naked or in their underwear while they were tortured.

Human Rights Watch has documented the use of the following torture methods:[10]

- Prolonged and severe beating, punching, and kicking;

- Beating with objects (cables, whips, sticks, batons, pipes);

- Falaqa (beating the victim with sticks, batons, or whips on the soles of the feet);

- Shabeh (hanging the victim from the ceiling by the wrists so that the his toes barely touch the ground or he is completely suspended in the air with his entire weight on his wrists, causing extreme swelling and discomfort);

- Balanco (hanging the victim by the wrists tied behind the back);

- Basat al-reeh, or “flying carpet” ( tying the victim down to a flat board, the head suspended in the air so that the victim cannot defend himself. One variation of this torture involves stretching the limbs while the victim lies on the board (as on a rack). In another variation described to Human Rights Watch the board is folded in half so that the victim’s face touches his legs both causing pain and further immobilizing the victim);

- Dulab, or the “tire method” (the victim is forced to bend at the waist and stick his head, neck, legs and sometimes arms into the inside of a car tire so that the victim is totally immobilized and cannot protect him or herself from ensuing beatings);

- Electrocution (with electric prods or wires connected to a battery);

- Mock execution;

- Threats against the detainee (of execution, rape);

- Threats against family members (of detention, rape);

- Exposure to cold/heat;

- Sexual violence;

- Stress positions, such as being forced to stand upright for hours or days;

- Hanging upside down;

- “Standing on the wall” (The victim stands with his back to the wall. His hands are tied to the wall up by his head. There is a metal pole sticking out of the wall pressing into his back and causing discomfort but he can’t move because his hands are tied. His feet are on the ground);

- Pulling out fingernails;

- Plucking out hair/beard;

- Use of acid to burn skin;

- Burning; and

- Prolonged nudity.

Some of these torture methods, such as the use of electric shocks, the dulab, and basat al-reeh, involved the use of objects, some of them apparently custom-made, which indicates that the torture was planned. Many of these torture methods had been used in Syria in the past. In 1991, Human Rights Watch documented many of these forms of torture.[11]

While information from former detainees indicates that particular detention facilities, or particular interrogation officers, preferred certain torture methods over others, the replication of torture methods across branches and even agencies shows that the use of torture was systematic.

ShabehDetainees described being hung from the ceiling by their wrists. Some detainees described their toes barely touching the ground, while others said they were suspended in the air with their entire weight on their wrists, causing extreme swelling and discomfort. While suspended, a number of detainees told Human Rights Watch they were beaten. “ They would beat me and say ‘don’t you want to confess!’ For an hour and a half I was hanging. I didn’t confess and they brought me down. At his point it was 3.30-4:00 am. My hands were red like blood.” — Male detained in the Kafr Souseh neighborhood of Damascus in September 2011. Human Rights Watch interviewed him by phone while he was inside Syria.

|

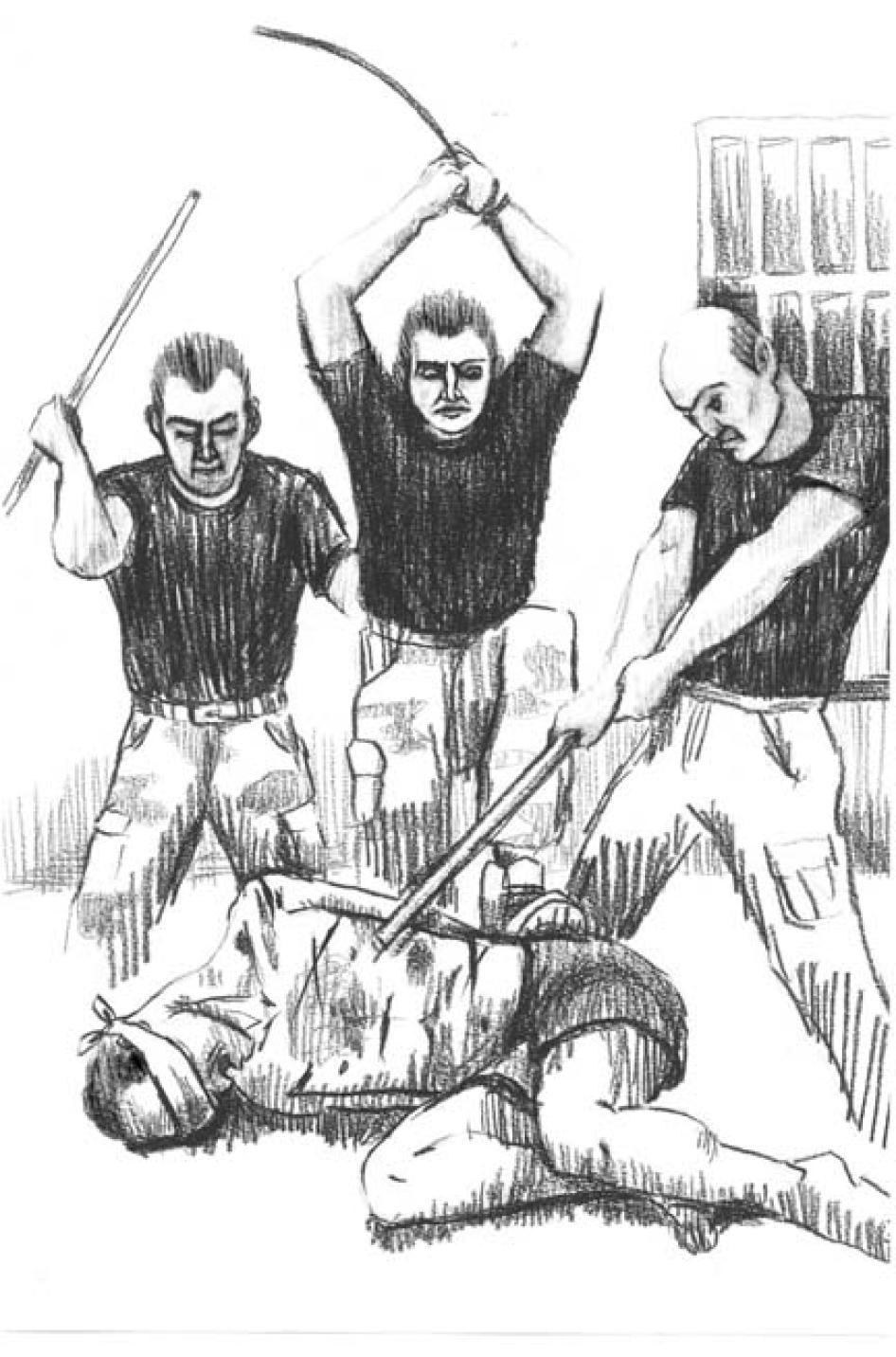

Human Rights Watch commissioned a

Syrian artist to produce sketches based on statements received from former

detainees and security force defectors. They depict six of the most commonly

used torture methods in detention centers across Syria — shabeh, dulab, beating

with object, falaqa, electrocution, and basat al-reeh. They are not

representations of any specific individuals.

© 2012 Human Rights Watch

DulabDetainees described being folded at the waist and having their head, neck, and legs put into a car tire so that they were immobilized and could not protect themselves from beatings on the back, legs, and head including by batons and whips. Some detainees described having their arms inside the tire as well. “They fold you in half, feet first, and put you inside so that you can’t move at all. Then they started beating me. They had a braided electrical cable and they hit me with it. There was no talking. It was like this for 30 minutes then they pulled me out and poured water on my legs and hands. Cold water. I was feeling death.” — Soldier who was detained in the Military Intelligence branch in Latakia in June 2011. Human Rights Watch interviewed him in Hatay, Turkey in January 2012. |

Beating with ObjectsOn the way to and inside detention facilities detainees described being bound and blindfolded while being beaten by batons, cables, whips, and other objects. “There were 20 security officers. To welcome us each started beating us with a whip while we were standing. We were ten people in a row [one right after the other]. The officer hit me in the chest and I fell on those behind me and they fell down. Each security officer hit us and they were laughing. They made us lie on our stomachs and they hit the bottoms of our feet… ” — Male detained in the Central Prison in Idlib in July 2011. Human Rights Watch interviewed him in Hatay, Turkey in January 2012. |

FalaqaDetainees described being beaten on the soles of their feet with sticks and whips to the point that their skin was raw, their feet swollen and bleeding, making it impossible to walk. “He ordered me to raise my legs and then he started hitting me on my soles with a thick wooden baton. I started screaming “I didn’t do anything, I can’t bear the pain.” He hit me 5 times and ordered me to stand up. After standing he told me to run in my place. I couldn’t lift my legs because of the pain.” — Male detained at the Tadumr roundabout checkpoint and taken to the Political Security branch in Homs. Human Rights Watch interviewed him by Skype while he was inside Syria in April 2012. |

ElectrocutionDetainees described being bound, sometimes on a chair, having cattle prongs attached to their bodies, and being jolted repeatedly by electrical currents. The prongs were reportedly attached to sensitive places including genitalia, inside the mouth, and also on the neck, chest, hands, and legs. “I didn’t confess. The interrogator said ‘bring me the electricity.’…The guard brought two electric prongs. He put one in my mouth, on my tooth. Then he started turning it on and off quickly. He did this 7/8 times. I felt like, that’s it. I am not going to leave this branch.” — Soldier who was held at the Air Force Intelligence branch in Latakia in June 2011. Human Rights Watch interviewed him in Hatay, Turkey in January 2012. |

Basat al-reehA number of detainees described being tortured on the “basat al-reeh”. Some indicated that this involved being tied down to a flat board so that they were helpless to defend themselves with their heads suspended in the air. They said their hands and feet were tied together and that they were bound across the chest and legs. Other detainees said that their limbs were also stretched, or pulled, and others indicated that the board folded in half so that their faces touched their legs, both causing pain and further immobilizing them. “They folded me so my head hit my toes. Hands up above my head, with my elbows bent. They were hitting me with a silicon cable and something like braided electrical cable. I passed out. First he closed it. I felt all of my muscles pulled. He closed it and was beating me, and then I passed out.” — Male detained in March or April 2011 and held in a shabiha run detention facility in Latakia. Human Rights Watch interviewed him in Hatay, Turkey in January 2012. |

All the detainees Human Rights Watch interviewed said the interrogators verbally and physically humiliated them, and threatened both them and their relatives with further abuse or, in some cases, execution.

Ten of the detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they had been subjected to sexual abuse and three said they had witnessed sexual abuse of others. The sexual abuse included rape, penetration with objects, sexual groping, prolonged forced nudity, and electroshock and beatings to genitalia.[12]Thirty-one-year-old Halim, who was detained in Daraa governorate on August 8, 2011 and later transferred to Branch 291 where he spent about 20 days, told Human Rights Watch:

They took five of us out to the corridor. Four were waiting while the fifth was being interrogated. We were standing up, blindfolded, and handcuffed. They beat me. An officer placed a gun to my head, he gave me electric shocks with a stun-gun, and he made me sit on a stick in the ground [sexually abusing me]. There were no real questions— just accusations. But I denied everything.[13]

In most cases documented by Human Rights Watch, detainees were subjected to a combination of these torture methods, often with increasing levels of pain. Amine, a former career soldier who was detained on April 9, 2011, showed Human Rights Watch burn marks on his wrists and explained that they were caused by torture by electricity during his 40-day detention in Military Intelligence Branch 291 in Damascus:

The first day they took me out for interrogation one of the officers punched me in the face and broke one of my teeth. Another said to somebody who just entered the room that he should “beat the shit out of me.” They lifted my legs and beat me with sticks on the soles [of my feet]. As a result, they broke two of my toes on the left foot. They also kicked me with their boots. I don’t know how long it lasted. Maybe it lasted for 12 hours. They took shifts. Every time I called for help or shouted “stop” they laughed.

Then they said “connect him to electricity.” The put me in a chair and placed one cable in my hand and clipped another to my right wrist. I just didn’t have anything to tell them.

I lost consciousness so I don’t know how long it lasted. I woke up when they threw water on me. Then they took me back to the cell. I was naked and received no food and no water. But I couldn’t even lie down because there was not enough space and there was water on the floor.

A couple of hours later they brought me back for interrogation. This time they connected me to electricity before even talking to me. This time, the cables were connected to my lower legs. A doctor later told me that I have lost 60% of the sensitivity in my right leg.

They threatened to arrest my wife, daughter, and my oldest son. They were using my wife’s name. I took their threats very seriously. I fainted again from the electric shocks and they must have dragged me back because when I woke up I was back in my cell.

A couple of hours later they took me out for interrogation again. This time they started using electric shocks to my private parts and they threatened to give me an “acid bath.”[14]

Amer, a 23-year-old man from a town in the Idlib governorate, described to Human Rights Watch how he was tortured during his 42-day detention in the Political Security Branch in Latakia:

They undressed me, tied my hands behind my back, and hit me on my private parts. They clipped my hands to a metal pipe and lifted me so that my feet hardly touched the floor. They kept me like that for two days. When they released me I couldn’t stand, my feet were completely swollen.

I then spent five days in a single cell with six other people. After that 15 officers took me to a separate room. They were cursing my mother and sister and threatened to rape me. They put me on a basat al-reeh – I was lying on my back, tied to a board, and they lifted my head and legs. All this time I was undressed. They wrapped wires around my penis and turned on the electricity. I could just hear it buzzing. They did this maybe five times for about 10 seconds. I passed out.

When I regained consciousness they were pushing my legs and hands into a tire. My entire body was blue from beatings.[15]

Several former detainees told Human Rights Watch that they had witnessed people dying from torture in detention. Five defected security force officers also told Human Rights Watch that they had witnessed detainees being executed and beaten to death while in custody.[16]

Human Rights Watch has documented deaths in custody in the following detention facilities:

- Air Force Intelligence Branch in Mezzeh airport, Damascus;[17]

- Idlib Branch of the Department of Military Intelligence;[18]

- Homs Branch of the Department of Military Intelligence;[19]

- Central Prison Idlib;[20]

- Temporary holding facility in Daraa stadium.[21]

As of June 18, 2012, the Violations Documentation Center, a Syrian monitoring group collecting the names of those killed and detained in connection with the anti-government uprising, had recorded the names of 575 people who died in custody since March 2011.[22]

Walid, a member of the riot police (Hafz al-Nizam), Brigade 121, Battalion 225 told Human Rights Watch:

In December a protester was killed at our base in Tel Al-Harra, in Daraa governorate. We had arrested him earlier at a protest and brought him back to the base. He was handcuffed and we told him to praise Bashar [al-Assad]. He refused so others in my unit beat him. After they beat him he was still combative and responded “your leader is nothing and your mothers are whores.” One colonel got angry and ordered that they use more violence against the detainee. Seven officers beat him with batons for more than an hour that evening until he died. Later, the colonel said, “put this dog outside” so they placed his body in an empty house. I saw the body before it was taken away, his face was bloody – I knew it was the same person that they had brought in, but his face was now totally different because of the disfiguration. Beatings are common when we detain people but not deaths. However, no one looks the same after we have arrested them and transferred them to [General Intelligence].[23]

Ghassan, a defected sergeant from Brigade 18, Battalion 627 told Human Rights Watch that on January 11 or 12 he saw 12 corpses of men who had been brought in alive earlier that night to his base in Zabadani. He said,

All of them were wearing civilian clothing and two of them were wearing pajamas. None of them had beards. I saw their faces as I walked by them and their faces were disfigured from blunt force trauma. Near the bodies, I saw shovels that had blood and what looked like brain particles. A soldier in the 4th Division who participated in their killing told me that they were ordered to kill them because they were all foreign terrorists. But when I went into the Colonel’s office, I saw the dead men’s identification cards in plain view on his desk. All the men were Syrians, from Sarghaya. The soldier told me that he and other soldiers had killed the men. He didn’t say how but that they were all alive when they brought them in.[24]

Human Rights Watch also received information about deaths in custody from the families or friends of the victims. Family members of the victims told Human Rights Watch they had no information about their relatives’ fate or whereabouts after security forces detained them until the day they received a call, usually from a local public hospital, asking them to pick up the body of their relative. In some cases, the bodies were found dumped in the street. In all cases where families described finding their relatives’ bodies to Human Rights Watch, they said the bodies bore marks consistent with infliction of torture, including bruises, cuts, and burns.

The authorities provided families with no information on the circumstances surrounding the deaths of their relatives and, to Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, have launched no investigations. In many cases, families of those killed in custody had to sign documents indicating that “armed gangs” had killed their relatives and had to promise not to hold a public funeral as a condition of receiving the body.

The ban against torture is one of the most fundamental prohibitions in international human rights law. No exceptional circumstances can justify torture. Syria is a party to key international treaties that ban torture under all circumstances, even during recognized states of emergency, and require investigation and prosecution of those responsible for torture.[25] When committed as part of a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population, torture constitutes a crime against humanity under customary international law and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[26]

Individuals who carried out or ordered the commission of crimes against humanity bear individual criminal responsibility for these crimes under international law, including the Rome Statute.[27]

Military commanders and intelligence officials could also bear responsibility for violations committed by individuals under their direct or ultimate command in accordance with the doctrine of command responsibility when they knew or should have known about the crimes and failed to prevent them or to submit the matter for prosecution.[28] This would apply, without exception, not only to the officials overseeing detention facilities, but also to the heads of intelligence agencies, members of government, and a head of state, none of whom are exempt from responsibility.[29]

Detention and Torture of Children, Women and Elderly

While the majority of the former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch were young men in their 20s and 30s, security forces also detained and tortured particularly vulnerable people such children, women, and the elderly.

As with the total number of detainees, it is virtually impossible to establish how many children, women, and elderly persons the security forces have detained, but local activists have recorded the detention of 635 children and 319 women as of June 22, 2012.[30] Through interviews with children and other detainees who witnessed the torture of children during their detention Human Rights Watch has documented the detention and torture of children in 12 cases.[31]

For example, Hossam, age 13, told Human Rights Watch that security forces detained him and a relative, also 13, in May 2011 and tortured him for three days at a military security branch about 45 minutes by car from Tal Kalakh:

Every so often they would open our cell door and yell at us and beat us. They said, “You pigs, you want freedom?” They interrogated me by myself. They asked, “Who is your god?” And I said, “Allah.” Then they electrocuted me on my stomach, with a prod. I fell unconscious. When they interrogated me the second time, they beat me and electrocuted me again. The third time they had some pliers, and they pulled out my toenail. They said, “Remember this saying, always keep it in mind: We take both kids and adults, and we kill them both.” I started to cry, and they returned me to the cell.[32]

It was the detention and torture of children from the southern town of Daraa in March 2011 that triggered the first anti-government protests in Syria, and in the following months several other cases, including the torture and death of 13-year-old Hamza Ali al-Khateeb, caused an outcry in Syria and internationally.[33]

In cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the detained children were usually between 13 and 17 years old, although some witnesses and defectors reported seeing boys as young as eight in detention. They were mostly held in the same cells and in the same conditions as adults, sometimes in solitary confinement, and subjected to many of the torture methods described above.

While the vast majority of former detainees interviewed were men, Human Rights Watch also interviewed women who had been detained. Sabah, a female adult detainee who was held in the Military Intelligence Branch in Jisr Shughour in the Idlib governorate in November 2011, described to Human Rights Watch how she was beaten and groped by a guard while in detention. She said:

The director asked me why I was going to demonstrations … I didn’t lie. He asked what I said in demonstrations and I told him … Then he slapped me. I will not forget it. He told the boys to come take me … they took me to a closed room. There were boxes in it. It was like a storage room. There were also broken chairs and other things. They took my abaya off. I was wearing jeans and a tee-shirt underneath, and a guard tied my hands behind my back. I said, “A dog like you doesn’t have a right to do anything [to touch me] …” He grabbed my breasts. [Eventually] he let my arms untie. I said, “Beat me, shoot me, but don’t put your hand on me.” … He came to grab my breasts again and I pushed him ... When I pushed him he fell on the boxes. Then he grabbed me by the chest and threw me against the wall. I fell and he started beating me with a stick. On the knee and on the ankle. My ankle was also broken [along with my hand] …[34]

Another female detainee, Nour, described to Human Rights Watch how she was sexually abused when she was detained in Military Intelligence Branch 235 in Damascus in late 2011/early 2012 for two to three months:

There were three other women in the cell when I arrived … Throughout our time in that cell, the four of us there were permanently in one of four positions: They tied our handcuffed hands above our heads onto a chain coming out of the ceiling and chained our feet together with our feet flat on the floor. They tied us face up to a metal bed which just had two planks of wood on it – we were in an X position so our wrists and ankles were attached to the four corners of the bed frame. They put our entire hunched body into the hole of a big tire with our back bent forward. They tied us to a metal chair with no bottom or back to which they sometimes attached electrodes to electrocute us.

With every new shift of the guards, they would switch our positions. We slept in those positions. They electrocuted us quite often … Each time my body and particularly my jaw and teeth would clench up for a long time – it was extremely painful …

They did other things to us too … [They] raped us while we were on the bed … [one of them] used to force the soldiers who were reluctant, saying things like “I have a sister,” to rape us. In my case they raped me about four or five times … Twice, more than one man raped me one after the other. I cannot remember how many it was each time.[35]

There were also elderly people among those detained. Seventy-three-year-old Abu Ghassan told Human Rights Watch that in the early morning one day in March 2012, the army came to the mosque in his town in the Idlib governorate. Abu Ghassan said that while he was praying with his 71-year-old brother about 50 soldiers arrived to the mosque with tanks and other military vehicles and, after checking his documents, said that he was wanted by the authorities. Abu Ghassan said:

They put me in the car, handcuffed, and kept me there all day, until seven in the evening. I told them, “I am an old man, let me go to the bathroom,” but they just beat me on the face. Then they brought me to State Security in Idlib, and put me in a 30-square-meter cell with about 100 other detainees. I had to sleep squatting on the floor. There was just one toilet for all of us. They interrogated me four times, each time asking why some of my family members joined the FSA. I didn’t deny it, but said there was nothing I could do to control what my relatives do. They slapped me on the face a lot.[36]

II. Syria’s Detention Facilities

Syria’s network of underground detention facilities are run by the country’s four main intelligence agencies, commonly referred to as the mukhabarat:

- the Department of Military Intelligence (Shu`bat al-Mukhabarat al-`Askariyya);

- the Air Force Intelligence Directorate (Idarat al-Mukhabarat al-Jawiyya).

- the Political Security Directorate (Idarat al-Amn al-Siyasi); and

- the General Intelligence Directorate (Idarat al-Mukhabarat al-`Amma).

Each of these four agencies maintains central branches in Damascus as well as regional, city, and local branches across the country, in virtually all of which there are underground detention facilities of varying size.

In addition to the large number of detention centers in intelligence branches, the Syrian authorities also established numerous temporary unofficial detention centers in stadiums, schools, hospitals, and on military bases. These temporary detention facilities often served as large collection points where the security forces gathered hundreds of detainees before they screened them and transported them to other detention facilities.

In some cases, intelligence agencies also used some of these newly established detention centres for longer-term detentions, possibly because their own underground detention facilities were full. For example, intelligence agencies assumed control of at least one floor and the basement of the Central Prison in Idlib, subjecting detainees to prolonged detention, interrogations, and torture in that facility.

The following chapters provide information about detention facilities run by these four agencies, including, when available, the names of those in charge, the location, general comments, methods of torture documented by Human Rights Watch, and statements by eyewitnesses and victims.

Department of Military Intelligence

Director:

Maj. Gen. Abdul Fatah Kudsiyeh[37]

Branch 291 – Damascus [38]Officers in charge of facility:

Location:Coordinates: 33.50462N, 36.274799E[42] Damascus city. May 6 Street, commonly referred to as the “Street of Branches,” on the northeastern corner of the intersection with April 17 Street. Documented methods of torture and ill-treatment:Beating; beating with objects; shabeh; electrocution; threats against detainee; exposure to cold; threats against family members; sexual abuse. General comments:Detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they were kept on the second or third underground floor. At the bottom of a set of stairs there was a large entry room. Most of the torture took place in this room or in interrogation rooms on the same floor, which were accessed through a door from the entry room. Interrogations also took place on the ground floor. From the entry room on the underground floor, double doors lead to a corridor with several common cells on each side and about 16 individual cells along two shorter corridors off the main corridor. The detainees said that the cells were extremely over-crowded. Three of the detainees said that the group cells, which measured approximately 20 square meters, held 60-75 people. Two detainees said that the individual cells, measuring about one square meter, held five or six people. (By using his hand, one detainee estimated that the individual cell measured 1.5 by 0.70 meters.) |

This map shows the locations of detention centers that were identified by multiple witnesses. Using satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch asked the victims and defectors to point out the buildings where torture took place. Former detainees and defectors corroborated the findings by describing the facilities in detail and drawing layouts of the floors where they were detained and interrogated.It also sets out the names of the known commanders. The report sets out where there is evidence of direct, indirect or command responsibility of the commanders, but Human Rights Watch does not have evidence of this applying in each case.

Statements by victims and eyewitnesses:

They took five of us out to the corridor. Four were waiting while the fifth was being interrogated. We were standing up, blindfolded, and handcuffed. They beat me. An officer placed a gun to my head, he gave me electric shocks with a stun-gun, and he made me sit on a stick in the ground [sexually abusing me]. There were no real questions– just accusations. But I denied everything.

The officer then called a soldier and told him to suspend me in the shabeh position. I didn’t know at that time what it was. They took me out to the corridor. There was a tall double-door leading to the corridor with the cells. There was a ring installed on top of the door that doesn’t usually open. They handcuffed me behind my back and then handcuffed me to the ring so that only my toes could reach the ground, causing pressure on the wrists and shoulders. Anybody passing by hit me. They kept me like this for 48 hours. I couldn’t move for three days after this and I needed help to go to the bathroom.

—Thirty-one-year-old Halim, who was detained in Daraa governorate on August 8, 2011, and later transferred Branch 291 where he spent about 20 days. [43]

***

They made me bend over and took a piece of ice and pushed it into my anus six times. Then they tied me and hung me upside down for six hours. The ice-torture was difficult. I was ready to confess that I had owned a tank. We were six people in a small cell that used to be a toilet. They were running the air-conditioner so it was very cold. I started throwing up and suffered from diarrhea.

—Thirty-one-year-old Khalil, who was detained in the Idlib governorate on June 29, 2011, and spent about two months in several places of detention, including six days in Branch 291. [44]

***

After the first week they took me for questioning. They read to me what they said I had confessed to while in the Military Intelligence branch in Aleppo. But the information was completely different [from what I told the interrogators there]. It said that I had confessed to carrying weapons, that I was part of gangs, that we communicated with other gangs and so on. I denied everything for three hours. Then they placed me facing a wall with my hands cuffed behind my back for seven or eight hours.

The next day the interrogation continued. They started threatening me and my family. They said that if I don’t confess they would bring in my mother and siblings and rape and abuse them. He was going through my phone, asking about names.

They beat me with batons and electric cables before they again made me stand for three, four hours before they brought me back to the cell. The same routine took place three, four days in a row.

We could hear people from other cells being tortured, including women who were screaming when they slapped them.

Some people were held standing against the wall deprived of sleep for up to seven days. They would just lose it and started confessing to everything without even being asked.

—Fawzi who was detained for the second time on August 6 and spent about 70 days in detention, including about 40 days in Branch 291. [45]

***

Because they said I organized demonstrations they tortured me with electricity. They hooked it up to my ear. I was in a cell with 40 people. Twenty-seven of them were from Idlib, 10 from Daraa, and the rest from Deir al-Zour. We were three floors underground … They beat me in the interrogation room while I was blindfolded. I was standing and one person was beating me. I confessed to going to demonstrations … They took me to another guy who put the electricity on my ears. This was in one big room. There were lots of people standing there.

—Ammar who was detained in June 2011 and spent almost two months in detention. [46]

Branch 235 (“Palestine Branch”) – Damascus [47]Officers in charge of facility:

Location:Coordinates: 33.491501N, 36.319008E Damascus city. Mohallak al-Janoubi (the Southern Interchange) road on the northwestern corner of intersection with Damascus Airport Motorway. Documented methods of torture and ill-treatment:Beating; beating with objects; dulab; electrocution; shabeh; threats. General comments:Several former detainees said that Branch 235, or the “Palestine Branch” as it is often called, is one of the most feared detention facilities. According to former detainees, Branch 235 has several underground floors where detainees are kept. Former detainees said that they were held on the second or third underground floors. Detainees were interrogated both on the third underground floor and on the ground floor. |

Statements by victims and eyewitnesses:

They interrogated me twice. The first time they used the dulab. They put my legs and head through the tire and beat me up with cables. The more I moved, the more they beat me. They hit me more than 100 times in an hour. My legs were so swollen afterwards I could hardly walk. The second time they used electricity. I was kneeling and they used an electric stick to shock me on my stomach, back, and neck.

I was placed in a small cell with no ventilation or light. There were about 60 people in there. The cell measured three by four meters. We took turns sleeping and we took turns taking our shirts off and waving them to move the air.

—Marwan, who was detained in Daraa in June 2011 and spent about four months in detention, including about a week in Branch 235. [49]

***

When I arrived at the branch they welcomed me by beating me 12 times with cables. Others were hit more. I was in the Palestine Branch for two days. They summoned me to interrogation. The other detainees said that I would not be hit if I stuck with the confession. I was hit five times with cables during that interrogation. During the next interrogation they told me that the crime was very serious and that they would send me to the General Intelligence Directorate. They hit me 15 times.

—Twenty-three-year-old Rudi, who was detained in Aleppo on October 17 and spent 47 days in detention, including two days in Branch 235 .[50]

When we arrived at Branch 235 they started beating us as soon as they pulled us out of the bus. They gathered us in a big room and started calling out names. The detainees with identification cards were sent to cells. About 50 people didn’t have any papers and officers told the soldiers to “have fun with them.”

I was sitting on my knees, facing the wall. They hit us on the back of the neck with a thick stick. When they called somebody’s name, five people would be standing at the door and beat us with cable-wires, sticks, and batons. They beat us for about 30 minutes before they took us to the next room and stripped us naked. Then they started beating us with a thick belt, which we called the “five-layer-belt” because they had wrapped several belts together with plastic tape.

—Sixteen-year-old Talal, who was detained in Daraa on April 1 together with his 23-year-old brother. He spent 11 days in detention, nine of them in Branch 235 .[51]

***

They took my fingerprints and beat me. I was barefoot. They beat my head against the wall and then they took me to the interrogation room where they continued to beat me and gave me electric shocks. After 30 minutes they took me two floors underground where they kept me for five days.

There was another interrogation. It was the same thing, but this time I noticed that somebody was writing. Somebody beat me with their fist and chipped my tooth. They pushed me to the ground and continued to beat me. They made me fingerprint four different documents.

—Twenty-one-year-old Samer, who was detained in Tal Kalakh on May 14 and spent five days in detention in Branch 235. [52]

***

On the eighth day they moved me to Branch 235 together with another detainee who was there because he had been interviewed by Al Jazeera. I stayed there for eight days and they beat me all the time. The Al Jazeera guy was kept in handcuffs all the time and he later told me that he was kept in a solitary cell. We were ten people together in a four-by-four meter large cell. We were all from different places.

—Twenty-nine-year-old Wael, who was detained in Tal Kalakh on May 14 and spent eight days in detention in Branch 235. [53]

***

I was there ten to fifteen days. Right away there was violence. They put me in a solitary cell after 30 minutes of beating. I was in the cell for five days. The only food I got was bread. There was water in the cell, from a faucet, but it was dirty. It ran yellow and sometimes red. During the interrogation they would ask me if I carried weapons and I said no. They hung me from my wrists, shabeh, so I was just on my toes. They would throw water on me and hit me with an electrical cable. They would throw hot water – it wasn’t boiling, but hot – on us when we passed out to wake us up ... There was torture every day except the last two.

—Nabih, who was detained in Latakia in June 2011. [54]

***

After we arrived at the branch they put me in a room, where from the sounds of voices it seemed like more than 15 people beat me … I was in the room for a while, they left me on my knees for three hours. It was like a corridor with people coming and going. As they came and went they would beat me with their hands, legs, Kalashnikovs [assault rifles], and electrical cable, and they were swearing. Then they put me in a room with an interrogator …

The interrogator is not a human being. He is not normal. He was giving orders to four other people in the room. They put me on the ground. It is a beating you cannot describe. They beat my back and feet with a big electric cable. I couldn’t sleep on my back for 25 days. There are still scars on my back.

They threatened to bring my mother. They asked whether I wanted them to bring my wife here and have all the guys sleep with her. Let your God come release you … I reached a point where I could not feel at all …

Then he took me down to the prison … Two guards met us behind a big metal door … These two untied my hands and blindfold and started beating me again. They beat me in an unimaginable way. It was just with their hands and just on the face.

You don’t understand how difficult it is to bear the beating from the prison guards. They know better than anyone how to swear, humiliate, and beat. You can’t take it … It takes you away from anything called humanity.

—Samir, who was detained in Damascus in July 2011. [55]

Branch 248 – Damascus [56]Location:Coordinates: 33.507938N, 36.274066E Damascus city. “Street of Branches.” Documented methods of torture and ill-treatment:Beating; beating with object; electrocution; dulab. General CommentsBranch 248 has detention facilities underground. |

Statements by victims and eyewitnesses:

When I arrived at Branch 248 I was screaming from pain because my legs were broken [from gunshot injuries]. They laid me down in an underground corridor. After five minutes five guys came and started to beat me. I was still blindfolded, but I was able to see a bit under the blindfold. They punched me in the face so I started bleeding from the nose. They left me alone when I pretended to be unconscious. Afterwards another guy came and smacked my head into the ground. Finally an officer came. They wanted to transfer me to a cell, but there was no room for anybody with broken legs so they transferred me to hospital 601 instead. After six days in the hospital they took me back to 248. In the cell, two guards held my legs apart and beat me in the groin.

—Thirty-two-year-old Hussein, who was detained in Da raa at the end of April after he was shot in both legs. [57]

In Branch 248 we were five in a cell that was 3.5 meters by 150 cm. I knew the size from the tiles. There was no blanket, nothing. There was no bathroom in the cell. We had a bottle of water which we would fill from the bathroom. I spent 20 days in the cell before they moved me back to Branch 291.

—Ammar, who was detained in June 2011.[58]

***

When I arrived [from the military intelligence facility in Homs to Branch 248] the treatment was also very bad. They took my clothes off and blindfolded me. They were beating me while I was naked, in front. They beat me with whips all over my body. My whole body swelled. They took me to a solitary cell. The torture noises were much worse here. It was forbidden to sit or to sleep. I was chained and standing the whole time. For more than three days I didn’t sleep. I couldn’t close my eyes. The next day they took me to the head of the branch. He said, look, you confessed. He showed me my finger prints and said that the old interrogators would testify against me.

They took me to the torture room and I would hear noises that were just unreal. When they took me to this room they were mostly beating me with a whip. I was blindfolded. They used electricity, how am I going to tell you, in sensitive places. Now it is four months later and there are still marks on my body. After I was tortured they put me in my cell. For three days I was just tortured. No interrogation, nothing. No one spoke with me. After three days of torture they took me to interrogation. I was here for six [days]. I was not allowed to sleep, not allowed to sit. If they saw me sitting they would put me in the tire and would hit me with a whip.

—Munir, who was arrested in May 2011 in Homs .[59]

Branch 227 – Damascus[60]Officers in charge of facility:

Location:Coordinates: 33.510586N, 36.274689E Damascus city. May 6 Street on the corner with Omar Bin Abdulaziz Street, near the Ministry of Higher Education. Documented Methods of Torture and Ill-TreatmentBeating; falaqa; shabeh; exposure to cold; stress positions. General CommentsBranch 227 is the Military Intelligence branch responsible for Damascus governorate outside of Damascus city. One former detainee said that the underground detention facility included both individual cells and a big room measuring about 100 square meters, which held about 400 people when he was there. At some point, according to this detainee, some of the older detainees were transferred to a different cell with slightly better conditions . [62] |

Statements by victims and eyewitnesses:

They brought me to confess on August 12. There weren’t really any questions – mostly beatings. They used falaqa and shabeh on me and soaked me with cold water. I passed out twice during the interrogation session. They used cold water to wake me up both times. The torture took place in the corridor. They also brought 14/15-year-old boys there. When I went back to the cell, the other people in the cell were crying. They had heard my screams. The skin on my right foot broke because of the swelling from the beating.

—Fifty-seven-year-old Mustafa, who was detained in early August 2011 and spent almost two months in detention. Human Rights Watch saw scars on Mustafa’s right foot, allegedly from swelling after the beating.[63]

***

From the army base they took us to Branch 227 where we arrived around noon. They tortured us until 9 p.m. In the beginning they kept us standing on our toes with our hands up in the corridor, blindfolded. Anybody walking by would hit us. Then they pushed us down the stairs – about 15-20 steps – and we were placed in a cell measuring about two by six meters with 50-60 detainees.

On the fifth day the guards summoned us for interrogation. The interrogator was kind, but then three officers took me to the torture room. They hit me a lot, but didn’t say anything. After ten days in detention they released me, but gave me a paper saying that I should come back to Branch 227 for further interrogation.

—Twenty-year-old Lutfi, who was detained in his military unit after an officer accused him and four others of planning to defect.[64]

Branch 215 – Damascus [65]Officers in charge of facility:

Location:Coordinates: 33.507379N, 36.274010E Damascus. On “Street of Branches,” next to the Carlton Hotel. Documented methods of torture and ill-treatment:Beating; beating with object; shabeh. General Comments:Branch 215 has detention facilities underground. One former detainee said that there were 76 people in a cell measuring 11 by 3.80 meters. [67] |

Statements by victims and eyewitnesses:

When we arrived they started punching, kicking, and beating us with cables. The next morning they started interrogating us. We received no food for four days. They brought water only on the third day. Those asking for food were beaten.

On the fifth day it was my turn to be interrogated. They took me to a different room and started reading the statement from Idlib. When I said that they had forced me to confess about the Kalashnikov somebody handcuffed me to a pipe below the ceiling. This was around 2 p.m. I could just barely reach the floor with my toes. The next day a kind guard loosened the hand-cuffs a bit so I could stand on my feet. I was kept like this for three days. I was not even allowed to go to the toilet.

—Thirty-one-year-old Khalil, who was detained during a protest in a town close to the Turkish border on June 29 and spent five days in Branch 215. Khalil showed Human Rights Watch marks from the handcuffs on his wrists.[68]

***

They moved us to a cell measuring 11 by four meters with 76 people. There was no air-conditioner, no bathroom. We were allowed to go to the toilet three times per day. Food was very bad. Many people were about to die because of medical problems such as heart, diabetes, high blood pressure, asthma, and allergies. During the 40 days I spent there, I showered only two or three times. There were lots of lice. The guards would hit us when we went to the bathroom, but they didn’t take me out for interrogation.

—Yamen, who was detained in the Daraa governorate on July 3 and spent two months in detention, including 40 days in Branch 215.[69]

Branch 245 – Daraa [70]Officers in charge of facility:

Location:Coordinates: 32.627697N, 36.09988E Daraa city. Hanano street. Documented methods of torture and ill-treatment:Beating; beating with object; hanging upside down; dulab. General Comments:Former detainees said that they were kept underground, usually for a relatively short time, before they were transferred to detention facilities in Damascus. Witnesses described the detention facility as having ten cells along a two-meter-wide corridor, that torture took place in the corridor, and that there is an interrogation room at the end of the corridor. |

Statements by victims and eyewitnesses:

As we walked down the stairs people on both sides were hitting us with cable-wires and other objects. You didn’t know where the blows were coming from. Then they took us to the interrogation room.

It was brutal. They didn’t ask any questions. They just hit us. You didn’t know when you would be hit or hit a wall.

They took us out of the interrogation room and made us face the wall, standing on our knees. If somebody moved, relaxed, or tried to adjust their position, somebody would hit them. We were blindfolded. We stayed there until a new shift arrived, perhaps for one day.

We only spent 15-20 minutes in the interrogation room. They used the tire method on us. At first an officer interrogated and tortured me, then another came. They kept accusing me of having killed two people.

—Mohsin, who was detained in Daraa near the Omari mosque on March 23.[72]

***

They removed our blindfold when we arrived and then they took us underground. They made us stand up against the wall. The cells were packed. They took us one by one for interrogation. They asked about armed people. When I said that I didn’t know anybody, they told me to “just pick somebody.”

They insulted us, calling us “traitors” and cursing us. They took us to a yard outside, made us lay down, and started beating us. They told us that they didn’t torture people in Daraa, so we’d better confess before they transferred us to Damascus.

—Ayoub, who was detained in Daraa in April together with his brother.[73]