Hostages of the Gatekeepers

Abuses against Internally Displaced in Mogadishu, Somalia

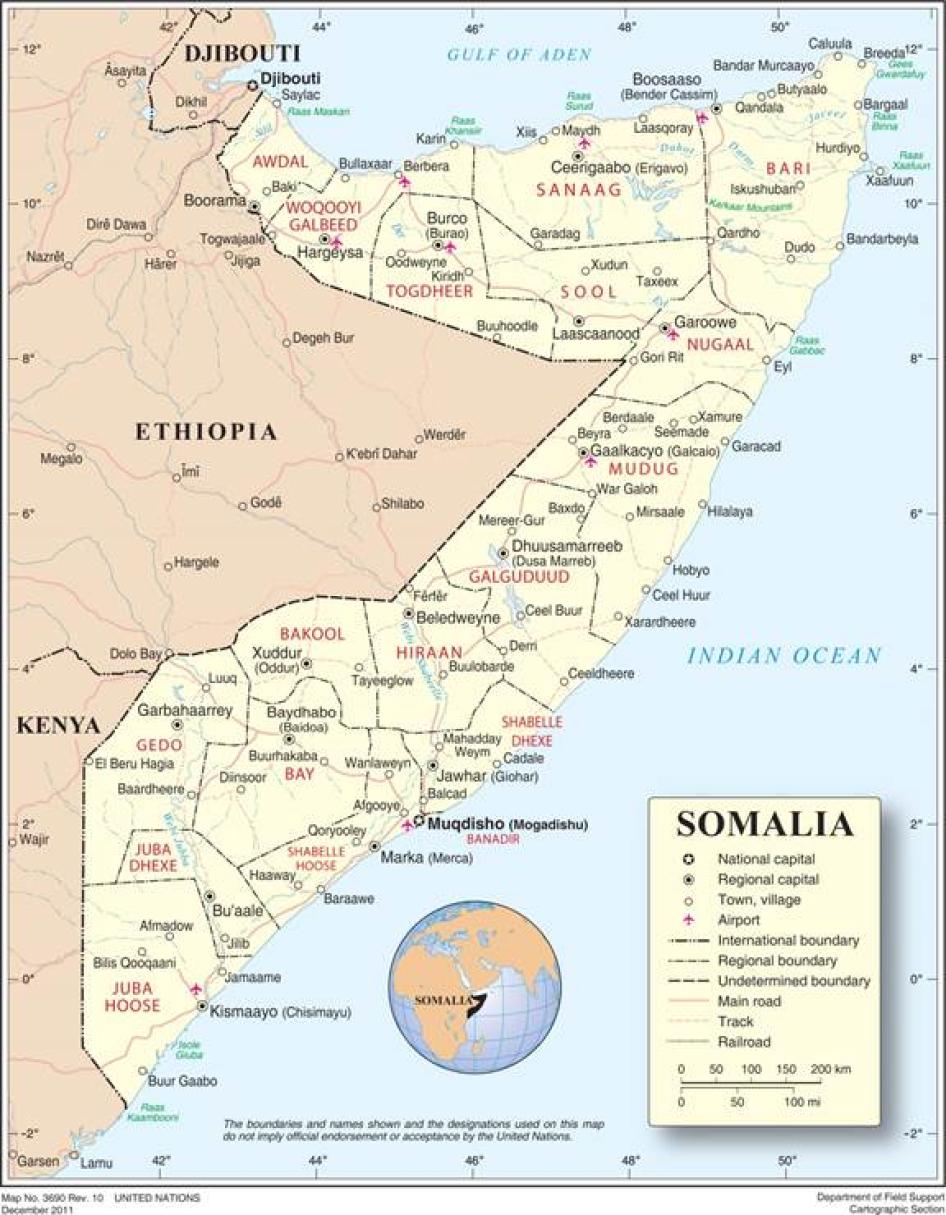

Map 1: Somalia

© 2011 United Nations

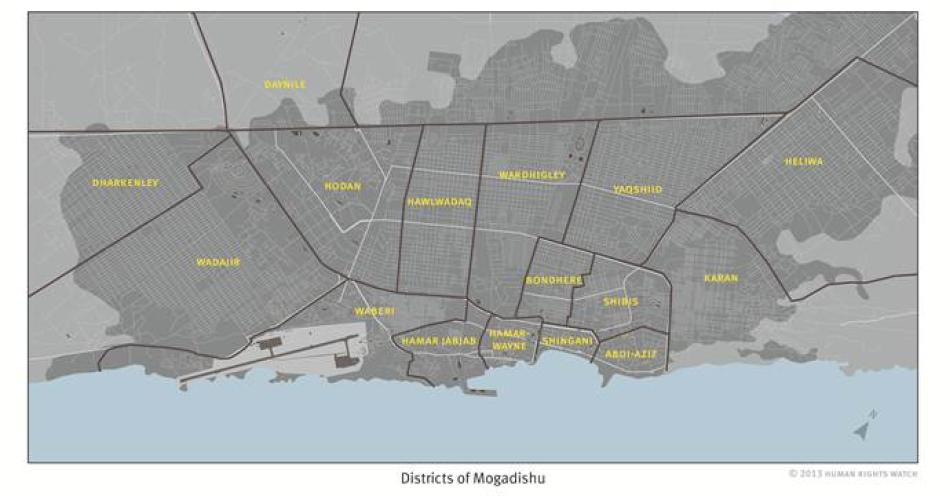

Map 2: Districts of Mogadishu

Summary

In Badbaado camp, only the name is very beautiful, the people are very unkind. The people running the camp are militia allied to the government.… They respect their clan more than the humanity. They don’t care about us, because if they are aware of the attacks against the IDPs they could respond when we reported to them. But they don’t rescue when the women are crying for help.

—43-year-old displaced woman, former resident of Badbaado camp, September 2011

The new government of Somalia plans to relocate tens of thousands of internally displaced people (IDPs) within Mogadishu this year. Many of these people had arrived in the war-torn capital in 2011 as a result of a devastating famine that provoked widespread displacement. The famine was caused by unrelenting drought, ongoing insecurity and fighting, the blocking of civilian access to humanitarian assistance, and increasing “taxation” of resources and livestock by the armed Islamist group al-Shabaab in south-central Somalia. Although there is no accurate death toll, tens of thousands of people are believed to have died as a result of the famine. Hundreds of thousands of people fled into neighboring countries and the United Nations estimates that more than 75,000 IDPs arrived in Mogadishu within the space of nine months in 2011. Instead of finding refuge and the humanitarian assistance they urgently needed, many displaced people encountered a hostile and abusive environment in Mogadishu.

This report is based on more than a year’s research, including 70 interviews with newly arrived persons displaced from south-central Somalia by the 2011-2012 famine and fighting in some of the main IDP camps and settlements in Mogadishu. It examines the situation of displaced people in Mogadishu from the height of the famine in July 2011 through November 2012. And it describes the abuses faced by these people, who are often silenced by those bent on exploiting their vulnerability.

Throughout this period members of displaced communities in Mogadishu faced serious human rights abuses including rape, beatings, ethnic discrimination, restricted access to food and shelter, restrictions on movement, and reprisals when they dared to protest their mistreatment. The most serious abuses were committed by various militias and security forces, often affiliated with the government, operating within or near camps and settlements for the displaced. Frequently these militias were linked or controlled by managers, or “gatekeepers” as they are known, of the IDP camp.

The fate of the displaced is often in the hands of the gatekeepers. By “hosting” IDPs, gatekeepers determine the location of settlements, the access of IDPs to these settlements and, often, their ability to access humanitarian assistance. The gatekeepers are generally from the dominant local clan; occasionally they are linked to local authorities or to clan militias that ostensibly provide security but in fact control the camps.

Among the many problems in the camps perhaps the most threatening is sexual violence. Displaced women and girls face a significant risk of rape in Mogadishu. They told Human Rights Watch that rape usually occurred at night in the huts. Even Badbaado, one of the few government-run IDP camps in the city, was not safe. Several women described being raped by armed men in uniform, some of whom were identified as government soldiers. Many victims of sexual violence never report their experiences to the authorities, fearing reprisals from the perpetrators, wary of the social stigma associated with sexual violence, and having little confidence that the authorities will respond. As the father of a young woman who was raped by four men in government military uniform said: “We don’t know anyone here, we are new to Mogadishu. So we didn’t try to go to justice, because the commander was harassing us at the time my daughter was raped. So how I can trust anyone here? We must keep silent.” Those that do speak out find few options for protection, medical assistance, or redress.

Camp security, which often depends upon government-affiliated militia, have regularly been implicated in threats and assaults against displaced people, including children. It is particularly dangerous during food distributions or inspections of tents provided by humanitarian agencies. And as a result of increasing pressure on land and property in Mogadishu, longstanding as well as recent displaced communities are becoming increasingly vulnerable to forced eviction.

The accounts of people displaced from Bay, Bakool, and the Shabelle regions of south-central Somalia, who are primarily from the Rahanweyn clan and the Bantu minority group, show that these communities are particularly vulnerable to abuse. Gatekeepers and their militia treat them as second class citizens, and subject them to various forms of repression, including frequent verbal and physical abuse.

These displaced communities face serious difficulties obtaining adequate food and shelter. Gatekeepers and militias use various methods to divert or steal food aid during or after distributions. Some of the displaced are forced to resort to begging due to lack of access to food.

Gatekeepers and militias profit from the displaced communities in other ways. They threaten to confiscate the tents provided to IDPs by international humanitarian agencies, to control their movement, including their ability to leave the settlements or camps. Several displaced women said that they felt as if they were hostages of the gatekeepers. As a 40-year-old woman said:

If we give her [the gatekeeper] the tents we have no other alternatives. If we try to move from the camp she takes the tents from us. We don’t have a plastic sheet, we don’t have other shelter, and we don’t have a place to sleep. So until we get rescued we must stay there as hostages.

The displaced, particularly men, have repeatedly tried to raise concerns about abuses with gatekeepers or local and central government authorities. Too often authorities failed to fulfill their promises, or worse, the displaced were later arbitrarily arrested or beaten by local police or militia for daring to raise their concerns. Further displacement has often been the only option available to displaced people seeking to protect themselves from violence.

The economic, social, and political context in Mogadishu at the time of the famine contributed to abuses against the displaced. The Islamist armed group al-Shabaab’s withdrawal in August 2011 created a security vacuum that Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government (TFG) forces were largely unable to fill. This vacuum allowed clan and freelance militias to resurge, many of them directly or indirectly linked to increasingly powerful district commissioners and local officials who emerged to assume control of several of Mogadishu’s districts and its economy.

Internally displaced people are protected under international law—international humanitarian law during wartime and international human rights law at all times. The protections due to IDPs by states have been summarized under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement (the “UN Guiding Principles”), which address both protection and access to humanitarian assistance, among other issues. Of emerging importance to IDPs in Africa is the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention), which came into force on December 6, 2012. The Kampala Convention provides a comprehensive description of the rights of internally displaced people and the obligations of states and non-state actors. Somalia is a signatory but not yet a party to the convention.

Abuses against IDPs have taken place in a general context of impunity for violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. Somalia has been wracked by numerous violations of international humanitarian law, including deliberate and indiscriminate attacks on civilians, summary executions, rape, and looting. Access to humanitarian assistance, which is protected under international humanitarian law, has been a serious problem, particularly in al-Shabaab controlled areas.

Those responsible for abuses can be difficult to identify, particularly given the plethora of armed groups active in Mogadishu and the ready availability of military uniforms. Displaced people who described rape and other abuses to Human Rights Watch occasionally identified government soldiers as responsible. Also implicated were members of militias connected to district commissioners and other local officials, some of which have been integrated into government forces. Gatekeepers and their local militias have abused the displaced population in camps they control by stealing their food and restricting their movement.

The TFG, which was in place until August 2012, largely failed to provide even the most basic protections and assistance to the internally displaced people in areas under its control during and following the famine. TFG officials often denied that the abuses, including rape, were even taking place. A UN official described the authorities’ denial that rape was occurring as the biggest obstacle to tackling the abuse. Increasing support for comprehensive medical and other services for survivors of sexual violence should be high on current donor priorities.

The TFG did not hold to account abusive members of government security forces and allied militias. Although the displaced population was one of the largest and most vulnerable populations in the area of Mogadishu under government control in 2011 and 2012, the TFG took few measures to address their needs. Two district commissioners were convicted by a military court for looting food aid, but then-President Sharif Sheikh Ahmed promptly pardoned them.

Humanitarian agencies and organizations and the donors who support them have long faced a challenging security situation and other obstacles to their efforts to provide assistance to those at risk in Somalia. During the famine there was significant pressure to rapidly expand assistance programs in Mogadishu. A sudden influx of new humanitarian organizations, some of which had little experience operating in Somalia, resulted in programs that neither appreciated the problems facing the displaced communities nor the complexities of providing assistance through local officials and gatekeepers.

The result was programs that at times reinforced the power of abusive officials and gatekeepers at the expense of the populations they were seeking to assist. These problems were exacerbated by the security situation, which forced UN agencies and other organizations to operate from afar and not carry out the monitoring necessary for such programs. Addressing these issues also does not seem to have been a priority.

Although the famine is officially over, fighting and insecurity persist in much of south-central Somalia. Even if some IDPs opt to return home in the coming months, displaced communities will remain a significant part of Mogadishu’s landscape for years to come. The end of the famine and the fragile peace currently affecting Mogadishu provide an opportunity for greater access and accountability for all international actors engaged with Somalia, an opportunity that should not be missed.

The new Somali government established at the end of the transition period in August 2012 has primary responsibility to provide protection for the displaced—and the rest of the Somali population. Showing Somalis that the new government, unlike its predecessors, is able to ensure the rights of the population under its control will be an important test of its credibility. The government plans to relocate the displaced within Mogadishu. This will be a positive step if the displaced are more secure and receive more assistance in the proposed relocation sites. The government should publicly commit to addressing key concerns about access to protection, adequate and effective police, and assistance in the new sites before any such relocations start. Donors supporting the Somali police should make the deployment of a competent and accountable police force to IDP relocation sites a priority. The government should ensure that displaced persons fully participate in the planning and management of the relocation process and make free and informed choices.

Ensuring the accountability of government forces and non-state armed groups for abuses they commit is also crucial. There have been some positive signals: the new president, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, publicly committed in November 2012 to hold to account members of the security forces responsible for rape. However, the police arrest and prosecution in January 2013 of a displaced woman and a journalist to whom she had spoken about her alleged rape by government security forces, points to a greater willingness to protect the perpetrators of sexual violence than to address the serious problem. The case—in which the two defendants initially received one-year prison terms, which were later overturned—has marred the credibility of the government’s reform agenda.

Somalia’s international partners contend that the new government represents real hope for the country’s future. But much will depend on the government’s ability to end impunity for abuses and establish the rule of law and respect for basic rights.

International donors should make clear that accountability for serious human rights abuses, including abuses committed by government forces, is crucial. To that end, the Somali government and its international donors should support both short- and long-term measures to address serious past and ongoing human rights abuses.

There is an immediate need for improved monitoring and reporting on human rights violations, protection concerns and diversion of assistance. Supporting an expansion of human rights monitoring and reporting by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is vital; the current UN review process on Somalia is a perfect opportunity to make this expansion a reality. Donors should also increase support for the UN Risk Management Unit and encourage UN agencies and nongovernmental organizations to collaborate with the unit. UN agencies with a protection mandate should give priority to programs that address the needs of the displaced communities. And the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator’s office should conduct, with the Somali government and other agencies, a Mogadishu-wide profiling exercise to identify and better respond to these needs prior to any future relocation.

Finally, addressing human rights abuses against the displaced and the Somali population generally means tackling longstanding impunity. The Somali government and its international partners should call for the establishment of a UN commission of inquiry—or a comparable, appropriate mechanism to document serious international crimes committed in Somalia—and recommend measures to improve accountability.

Key Recommendations

To the Somali National Government

- Take all necessary measures to ensure that sufficient, competent, and trained police are deployed to protect displaced communities in Mogadishu and other government-controlled areas, including in any new relocation sites, giving special attention to the security needs of women and girls.

- Appropriately discipline or prosecute members of the military, police, non-state armed groups, and government officials responsible for serious human rights violations, including abuses committed against displaced people and misappropriation of humanitarian assistance.

- Initiate, with the assistance of the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator and other international agencies, a profiling exercise of the displaced population in Mogadishu to assess protection needs.

- Support an enlargement of the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights within the new UN mission with significantly increased capacity to monitor and report on human rights violations.

UN agencies, the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and donors such as the United States, United Kingdom, European Union, Turkey, the African Union, and Organization of Islamic Cooperation should publicly endorse and support the above measures.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted more than 70 interviews with internally displaced people (IDPs) in the Somali capital, Mogadishu, including 36 women and girls, between August 2011 and December 2012. The majority of those interviewed were from Somalia’s Bay, Bakool, and Lower Shabelle regions and had arrived in Mogadishu in 2011 as a result of the famine, human rights abuses, and armed conflict in south-central Somalia.

The incidents and patterns of abuses they described occurred mostly in three Mogadishu districts—Dharkenley, Hodan, and Wadajir—where much of the displaced population is located.

Human Rights Watch visited at least 14 camps and settlements to interview displaced people between September 2011 and February 2012. Displaced individuals put Human Rights Watch in contact with other IDPs who were survivors of rape, physical abuse, or reprisals, some of whom were subsequently interviewed inside the camps. Others were interviewed outside the camps in private offices. All interviews of individuals under age 18, the internationally recognized age of children,[1] took place in the presence of a parent, with a parent’s consent. Human Rights Watch interviewed an additional 18 displaced people—including survivors of sexual and gender-based violence—camp leaders, and “gatekeepers” during a five-day visit to Mogadishu in October 2012. A Somali nongovernmental organization (NGO) assisted in the identification of witnesses to abuses and in their interviews. For security reasons Human Rights Watch was not able to interview members of militias linked to the camp gatekeepers.

Human Rights Watch conducted interviews in Somali and other local languages, and in Somali with English translation provided by members of a local NGO. Those interviewed were provided no remuneration.

Between September 2011 and December 2012 Human Rights Watch also spoke in person or by telephone with dozens of other knowledgeable individuals, including Somali local and central government officials, UN officials, representatives of international and Somali aid agencies, Somali human rights organizations, and members of the donor and diplomatic community.

The names of interviewees have been withheld and replaced by pseudonyms for security reasons. The majority of international representatives interviewed by Human Rights Watch also requested that their names and organizations be withheld. Names of alleged perpetrators are omitted except when sufficient eyewitness accounts, collected independently, pointed to the same individual being responsible for abuses.

The report is not a comprehensive description of the situation of all displaced communities in Mogadishu given restrictions on access to some city districts. Nor does it document all the human rights issues faced by IDPs in Mogadishu; rather, it highlights the most significant rights concerns of displaced people who have fled to Mogadishu over the last 18 months.

Background

Since the fall of the Siad Barre regime in 1991, state collapse and civil war have contributed to make Somalia one of the world’s worst human rights and humanitarian crises. While the country is prone to cyclical drought, it is the persistent violence against civilians, repeated displacement, and predatory looting by armed groups that have produced serious famine on several occasions in the last 20 years.

A significant proportion of Somalia’s estimated total population of 7.5 million has been displaced—sometimes repeatedly—either internally or beyond the country’s borders as a result of conflict and food insecurity.[2] According to the United Nations, 1.3 million people are currently displaced within Somalia,[3] and there were by July 2012 more than a million Somali refugees in the Horn of Africa.[4]

The 2011 famine followed intense armed conflict in Mogadishu as well as ongoing insecurity and intermittent fighting in southern areas of the country. It was exacerbated by severe restrictions on access for humanitarian agencies. Some of the most important organizations providing food aid had withdrawn or been banned from working in areas under the control of the armed Islamist group al-Shabaab.[5] Al-Shabaab’s increasing “taxation” of communities under its control further eroded the coping mechanisms of an already vulnerable civilian population.[6]

There were many parallels between the 2011 famine and a Somali famine in the early 1990s that affected similar geographic areas and communities.[7] Between 1991 and 1993 fighting in Mogadishu and subsequent clan-based fighting severely damaged harvests in the fertile southern regions of the country. Tens of thousands of people were displaced.[8] The Rahanweyn and Bantu communities living in the inter-riverine areas of the Bay, Bakool, and Shabelle regions were particularly affected both by the fighting that engulfed their land; the looting of resources, food, and crops by different clan militia; and the ensuing famine.[9] As in 2011 these communities—which have limited links with Somali communities in the diaspora and neighboring countries—were primarily displaced internally, with some fleeing to Mogadishu.[10] According to estimates by humanitarian organizations at the time, around 300,000 people lost their lives in the early 1990s famine, predominantly from the Rahanweyn and Bantu communities.[11]

As would occur prior to the 2011 famine, in the early 1990s increasing armed attacks on aid workers and looting of relief constrained the provision of humanitarian assistance.[12] The obstruction and looting of aid by clan-based and freelance militias in 1992 prompted the first UN intervention known as the United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM) to monitor a ceasefire and protect aid workers. By 1995, the subsequent UN and United States interventions were deemed a failure and were withdrawn. Between the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s, political and humanitarian aid, and general international interest in Somalia, dwindled as successive transitional Somali governments tried and failed to restore a functioning state.[13]

In December 2006 Ethiopia intervened militarily in Somalia at the request of the UN-backed Transitional Federal Government, ousting the Islamic Courts Union, an alliance of Islamic courts that had gained control of Mogadishu and other parts of south-central in mid-2006. The subsequent fighting pitted Ethiopian forces, the TFG, and allied militia against an increasingly powerful insurgency, including al-Shabaab. All of the warring parties were responsible for serious abuses in this period, including unlawful killings, rape, torture, and looting committed in a context of complete impunity.[14]

Ethiopian forces withdrew from Mogadishu in early 2009 following the UN-brokered Djibouti peace agreement,[15] but Ethiopian withdrawal did not bring the peace and stability that many Somalis hoped for. Conflict resumed in Mogadishu, this time between the TFG forces and the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) on the one side, and al-Shabaab and other armed groups on the other.[16] Fighting intensified in 2010 and 2011 as TFG and AMISOM forces tried to extend and consolidate territorial gains. Despite the increasing humanitarian needs, access for humanitarian organizations after 2009 was severely restricted by al-Shabaab’s attacks on and killings of aid workers, and their restrictions on aid delivery, bolstered by al-Shabaab’s expanded control in much of the country.[17]

Developments in 2011 and 2012

Although al-Shabaab withdrew from much of Mogadishu in August 2011, the group has continued to carry out attacks in the capital with grenades, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and suicide bombings.

Much of the conflict in late 2011 and 2012 shifted to south-central Somalia as the TFG, AMISOM, and allied forces tried to push back al-Shabaab from areas of control. The fighting caused further displacement of civilians.

On October 16, 2011, Kenya unilaterally intervened in Somalia to conduct military operations against al-Shabaab. In July 2012, Kenyan troops formally joined AMISOM, and alongside Somali militia, have been fighting al-Shabaab in Gedo and the Juba areas near the Kenyan border.[18]

Ethiopian forces also redeployed in Somalia in 2011,[19] conducting operations with two Somali militias: Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a (a Sufi militia) and Shabelle Valley State (SVS) (a regional militia), to take control of Beletweyne, along the border with Ethiopia, in December 2011, and then Baidoa, the capital of the Bay region in February 2012.[20]

Throughout 2012 the AMISOM, Ethiopian, TFG forces, and allied militia moved into many other key towns in southern Somalia, including Afgooye, Merka and Afmadow. In late September, following a Kenyan-led air and naval offensive, al-Shabaab fighters withdrew from Kismayo, the strategic southern port town and a major source of al-Shabaab’s revenue.[21]

Mogadishu during the Famine

The economic, social, and political context in Mogadishu at the time of the famine contributed to abuses against the displaced. Relevant factors included the governance situation and security vacuum following al-Shabaab’s withdrawal in mid-2011, the economy and system developed around aid distribution in Mogadishu, and clan dynamics that rendered the displaced population from Bay, Bakool, and the Shabelle regions more vulnerable.

Displacement as a Result of Famine

The UN declared famine conditions in July 2011, but early warnings of impending food shortages were already present in late 2010.[22] Conflict, social inequalities, and the absence of key organizations that typically provide food aid exacerbated the food shortages: the UN’s World Food Programme (WFP) and US-based nongovernmental organizations such as CARE[23] had limited access beyond Mogadishu due to both restrictions by al-Shabaab and restrictions imposed by US counterterrorism sanctions that affected aid delivered to areas under al-Shabaab control. The cumulative effect of all of these factors was a serious reduction in the humanitarian community’s capacity to respond to the unfolding crisis.[24] As a result, in the first quarter of 2011 there was a massive influx of displaced people from the affected regions into Mogadishu, where assistance was more readily available.[25] Others affected by the famine fled south towards refugee camps in Dadaab, Kenya, or west to Dolo Ado, Ethiopia.[26]

By July 2011 the UN declared famine in Bakool and Lower Shabelle regions, and by August the UN declared six regions of Somalia in a state of famine, including Mogadishu, particularly its IDP community.[27]

At the height of the famine, an estimated four million people—more than half of the resident Somali population—were reported to be in need of humanitarian assistance, around three million of whom were in the south in predominantly al-Shabaab-controlled areas.[28] Agencies’ assessments of the total number of IDPs in Mogadishu varied, but estimated that at least 150,000 people arrived in Mogadishu since 2011 as a result of the famine.[29]

By February 2012 the UN declared that the famine in Somalia was over but stressed that at least two million people were still in need of emergency humanitarian assistance.[30]

During the 2011 famine, humanitarian agencies faced a variety of challenges. As mentioned above, al-Shabaab banned the WFP, several other UN agencies, and most nongovernmental organizations from working in areas under its control in 2009 and 2010. This ban was extended to an additional 16 agencies and nongovernmental organizations in November 2011.[31] On January 30, 2012, al-Shabaab also banned the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the only remaining organization capable of carrying out large-scale food aid distribution in al-Shabaab areas.[32]

Since 2008, humanitarian organizations have also been affected by counterterrorism legislation such as the United States Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctions that criminalize assistance or financial payments to groups designated by the US government as foreign terrorist organizations, including al-Shabaab. The sanctions led to a significant decrease in US funding of humanitarian organizations and new, burdensome measures on those receiving US aid.[33]

Governance in Mogadishu

Other factors contributed to the dangerous situation facing displaced people in Mogadishu at the time of the famine. Mogadishu in 2011 and early 2012 was a war-ravaged city still wracked by fighting and lawlessness. Until mid-2011 the TFG controlled only a small section of southern Mogadishu and generally failed to provide any services to the population in these areas.

Al-Shabaab’s withdrawal in August 2011 created a security vacuum that the TFG forces were largely unable to fill. The transitional government lacked the means, and it seemed the will, to bridge this vacuum. Embroiled in internal disputes and focused on the political process leading up to the end of the transition, the TFG leadership failed to serve the vulnerable IDP population under its control. This vacuum allowed clan and freelance militias to resurge, many of them directly or indirectly linked to increasingly powerful district commissioners and local officials who emerged to assume control of Mogadishu’s districts and its economy.

After a one-year postponement, on August 20, 2012, the transition period ended, paving the way for a new Somali administration, including a new president, prime minister, and speaker of parliament. Both Somalis and Somalia’s supporters abroad heralded the process as a break with the past, pointing in particular to the selection of a leadership with a civil society background as a positive step. However, the new leadership faces enormous challenges in Mogadishu alone, chief among them, greater accountability of government forces and reining in the militias, including government-allied militia, that continue to exert significant control over much of the city.

Protection of IDPs and improvements in their living conditions, starting with steps to improve their basic rights, will be an important test of the new administration. It is a test that the previous transitional government failed, as this report describes.

Reliance on Gatekeepers

Ever since the relief efforts of the 1980s, and especially during and following the massive international involvement in the famine of the early 1990s, humanitarian assistance—specifically food aid—has played a key role in the political economy of Somalia. Patterns of control of aid and of the vulnerable communities who rely on it have become entrenched, with armed groups constantly vying for control of the resources and power associated with aid.[34]

A 2010 report of the UN Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea described the importance of food aid, and specifically WFP assistance in the Somali economy.[35] The report described the diversion of WFP assistance in Somalia as “large scale,” suggesting that around 50 percent of WFP assistance was being diverted, mainly through the creation of a cartel of contractors and transporters. It noted that in some cases the assistance was used to directly support warring parties.[36]

While large-scale diversion of food aid in the 2011 famine has to date not been documented, a 2012 report of the UN Monitoring Group described the means and methods of diversion at the camp level, the role of gatekeepers, and the implication of district and local officials in the process.[37] One in-depth media investigation documented diversion at WFP wet feeding (cooked food) sites.[38]

The UN’s declaration of famine in July 2011 led to a massive increase in the amount of emergency assistance coming into Mogadishu. According to Somalia analyst Ken Menkhaus:

The TFG leadership, and many (though not all) of the Somalis formally or nominally a part of the TFG as civil servants, security forces, paramilitaries, district commissioners, parliamentarians, and ministers approached the flood of famine relief pouring into Mogadishu as an opportunity to enrich themselves.[39]

At the level of IDP camps or settlements, direct control of the camp, its population, and the assistance brought to the camp is often in the hands of camp managers. Camp managers, more commonly known as “gatekeepers” or “black cats,” have existed throughout Somalia’s civil war and exist throughout the country. However, with the massive influx of aid into Mogadishu during the 2011 famine, the gatekeeper phenomenon appears to have taken on new dimensions. Gatekeepers are sometimes from the displaced community but more often in Mogadishu they are landowners or businesspeople from the local clan who have access to land and links to local clan militia or local authorities.

As the UN Monitoring Group report noted, often gatekeepers are intimately linked to district commissioners, their militia, and other local level authorities, including divisional leaders.[40] While the significance of gatekeepers varies across the city, they are the people who often represent the IDPs to aid agencies, distribute assistance, and often pay for protection or manage the relationship with landlords, local militia, political powerbrokers, and district commissioners.

Hosting displaced communities is a lucrative endeavor. As Ifrax D., a 32-year-old displaced woman living in Ufurow camp in Hodan, said of gatekeepers: “The people are assets for them, they are making business on them, they are depriving them of their rights.”[41]

Displaced people from weaker clans or minority groups are particularly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse at the hands of the gatekeepers. As Menkaus points out: “Too often, in the many deals struck over allocation of food aid locally, the weakest lineages are given short shrift. They are also the main victims of diversion of food aid by ‘black cats’ and others.”

The United Nations Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea noted in mid-2012 that:

The withdrawal of Al-Shabaab forces from Mogadishu on 2 August 2011 should, in principle, have improved access throughout the capital for aid agencies, and facilitated the direct provision of humanitarian assistance to vulnerable Somalis. The reality, however, was quite different: UN agencies, INGOs [international nongovernmental organizations] and their national counterparts were confronted instead with pervasive and sophisticated networks of interference: individuals and organizations who positioned themselves to harness humanitarian assistance flows for their own personal or political advantage. These “gatekeepers” often exercised control over the location of IDP camps; the delivery, distribution and management of assistance; and even physical access to IDP camps and feeding centres, through their influence over the “security” forces deployed to such sites.[42]

Gatekeepers are not alone in diverting food aid and seeking to control and exploit assistance at the local level. As a former senior TFG official told Human Rights Watch: “The IDPs don’t get humanitarian assistance directly, but through district commissioners, militias and gatekeepers: this is the biggest business in Mogadishu.”[43]

As a senior UN official put it, “The aid business, the whole chain is eating, the gatekeepers just steal what is remaining.” However, from the perspective of the displaced, at the camp level the gatekeeper is the central figure.

As explained above, given the absence of formal camps or any kind of centralized registration and government control, it is the gatekeepers who are often the interface with humanitarian agencies in Mogadishu.[44] Some humanitarian agencies have tried to minimize gatekeeper control over assistance and circumvent gatekeepers, while others have opted to end dry food distribution in camps. Some humanitarian representatives admitted having very little room for manoeuver. With the exception of the ICRC, which carried out a two-month assessment of local level dynamics prior to distribution, other organizations tended to rely on informal mechanisms, particularly their local partners or staff, to assess the local context and determine abusive gatekeepers and local-level actors. Because the UN directly implements very few projects in Mogadishu because of security reasons, it relies heavily on local implementing partners.

This report focuses on the districts of Wadajir, Dharkenley, and Hodan, where most of the displaced people who arrived in Mogadishu in 2011 are located, as well as one camp in Waberi district.[45] The gatekeeper and formal and informal security set-up differs from area to area, but some generalizations can be made.

In Wadajir district, the main camp, Rajo, which some humanitarian actors have described as a model camp, is administered and controlled by the district commissioner of Wadajir and the divisional leader. Security is provided by the district commissioner’s militia. The militia is Abgal, a Hawiye sub-clan dominant in Mogadishu. Part of this militia is reported to have been integrated into the government forces in recent years.[46] Siliga camp, also in Wadajir, includes one section that is controlled by Hawadle militia, another Hawiye sub-clan prevalent in Mogadishu, and another section controlled by an “umbrella” organization called Saredo, which is run by the wife of former Member of Parliament (MP) Osman Ali Atto, who are from the Sa’ad clan.[47] According to a recent study of political dynamics in Mogadishu, militias in Wadajir are affiliated to members of the local authorities, though this has not been independently verified by Human Rights Watch.[48]

Badbaado, the biggest camp in Dharkenley district, is administered by the government Disaster Management Agency and since October 2011 security is provided by police posted at the camp. However, security was initially provided by a commander reporting to the district commissioner of Dharkenley. Militias under the command of the district commissioner and deputy district commissioner are reportedly sometimes present in the camp. These militias are from two different Abgal sub-clans and have, as described below, clashed on occasion. Part of the district commissioner’s militia is reported to have been integrated into the government forces.[49] In Hodan district the situation is quite different, with a number of camps, gatekeepers, and militia; there are certain camps reportedly controlled by Sa’ad gatekeepers and militia where the Hodan district commissioner cannot even venture. One UN official told Human Rights Watch that the militias in this area are “better equipped and armed” than the police.

While not all gatekeepers seek to abuse IDPs in their camps, serious abuses are taking place at the hands of gatekeepers and affiliated militia, described in greater detail below.

Clan Dynamics

Internally displaced people throughout the world are particularly vulnerable: uprooted from their social networks, deprived of their livelihoods, often living on land belonging to others, leaving them open to abuse. The clan system in Somalia adds an additional layer of vulnerability to those most affected by the 2011 famine. While clan identity is only one among several factors contributing to the abuses against IDPs in Mogadishu, it can have enormous consequences. As Ken Menkhaus points out:

One of the most troubling but least discussed aspects of Somalia’s recurring humanitarian crises is the low sense of Somali social and ethical obligation to assist countrymen from weak lineages and social groups. This stands in sharp contrast to the very powerful and non-negotiable obligation Somalis have to assist members of their own lineage.[50]

A June 2012 IDP assessment in Mogadishu found that 60 percent of internally displaced people originated from Bay, Bakool, and the two Shabelle regions.[51] While an accurate picture of the famine-affected population is not available, it is believed that the majority of IDPs from southern Somalia displaced as a result of the famine in mid-2011 were from the Rahanweyn and Bantu communities.[52] Human Rights Watch’s research focused on newly arrived displaced persons in Mogadishu, therefore the majority of the interviews were with members of these communities. Both their social status, not seen as being one of the noble clans, and their livelihood strategies, being primarily agro-pastoralists and farmers, rendered them particularly vulnerable to famine and later to abuses in Mogadishu.[53] In Mogadishu the most powerful clans, notably in the districts on which this research focuses on, are from the Hawiye clan group. Neither of these two communities have established links with the Hawiye. The more limited international reach of the Rahanweyn and Bantu, including fewer links in the diaspora and neighboring countries, is also believed to undermine their social support mechanisms.[54]

While part of Somalia’s clan structure, the Rahanweyn are not considered as one of the “noble” pastoralist clans.[55] The Rahanweyn, or Digil-Mirifle, are agro-pastoralists and live predominantly in the inter-riverine area in Bay, Bakool, and to a lesser extent in Lower Shabelle and Middle Juba. They have traditionally been politically marginalized, although the last speaker of parliament under the TFG and the current speaker are both Rahanweyn. The Mirifle in particular speak a distinct Somali dialect known as Afmay. Although the Rahanweyn have traditionally been viewed as more socially diverse than other clans, integrating outsiders including Bantus, they do not have established protection networks with other clans and host communities in Mogadishu.[56] While this is not the only reason Rahanweyn IDPs have been vulnerable to abuse, it contributes to their vulnerability to threats from militia linked to more powerful clans.

The other group believed to have been disproportionately affected by the famine is the Bantu. The Bantu are not part of the Somali clan lineage system, and are predominantly farmers. Historically, the Bantu have faced significant discrimination, marginalization, and persecution because of their distinct culture and characteristics; a significant proportion of the Bantu are descendants of former slaves.[57] Like the Rahanweyn, they traditionally do not carry arms or have their own militia, rendering them particularly vulnerable to armed clans. Certain Bantu have integrated into the Rahanweyn clan but are generally prohibited from inter-marriage with the clans.[58]

Clan identity remains fundamental for access to protection and justice in Somalia, partly due to the traditional xeer system (customary laws that regulate intra- and inter-clan disputes, among other issues), rendering the Rahanweyn and Bantu more vulnerable.[59] According to research carried out in Puntland, minority clans are also more likely to be discriminated against within the formal judicial system because police, who tend to be from the majority clans, side with stronger clans.[60]

Abuses against Internally Displaced People in Mogadishu

The displaced Somalis who fled to Mogadishu over the last two years have been subjected to a range of serious human rights abuses, including rape, beatings, ethnic discrimination, and restrictions on access to food and shelter and freedom of movement.

Identifying the perpetrators of the abuses and their relationship with the authorities is often challenging given the plethora of armed groups in the city, including militias, and the ready availability of military uniforms. However, victims and witnesses of abuses often provide credible accounts that state security forces and government-allied militia, some of which are formally or informally entrusted with providing security in IDP settlements, are responsible for some of the abuses. Private individuals, including gatekeepers, and clan and freelance militia, have also committed abuses against the displaced for which they have not been held to account by the authorities.

Internally displaced people are accorded multiple protections under international human rights law,[61] and during the non-international armed conflict in Somalia, international humanitarian law.[62] It is first and foremost the responsibility of the government to ensure protection and assistance to populations under their effective control without discrimination.[63] The government is also prohibited from unnecessarily impeding access of humanitarian assistance to those in need.[64] Destruction, theft, and looting of humanitarian objects are prohibited.[65]

The various international legal protections afforded IDPs under international law can be found in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, which provide an authoritative restatement of existing international human rights, humanitarian, and refugee law as it relates to the protection of internally displaced people.[66]

The UN Guiding Principles provide that IDPs “shall enjoy, in full equality, the same rights and freedoms under international and domestic law as do other persons in their country. They shall not be discriminated against in the enjoyment of any rights and freedoms on the ground that they are internally displaced.”[67] National authorities have the primary duty and responsibility to provide protection and humanitarian assistance to IDPs within their jurisdiction.[68]

IDPs shall be protected, for example, against rape, torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and other outrages upon personal dignity, such as acts of gender-specific violence, forced prostitution, and any form of indecent assault.[69] They shall have the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose their residence, in particular the right to move freely in and out of camps or other settlements.[70]

Humanitarian assistance to IDPs shall not be diverted, in particular for political or military reasons.[71] All authorities concerned shall facilitate the free passage of humanitarian assistance and grant persons engaged in the provision of such assistance rapid and unimpeded access to the internally displaced.[72]

Additional protections are provided to IDPs under the regional Kampala Convention, which went into force in December 2012.[73] Somalia has signed but not yet ratified the convention,[74] obliging the government to refrain from acts that would defeat the object and purpose of the convention.[75]

Sexual and Gender Based Violence

Throughout the conflict in Somalia internally displaced women and girls have been particularly vulnerable to sexual violence. The extent of sexual and gender based violence (SGBV) against displaced women and girls is difficult to assess but is believed to be widespread though largely underreported throughout south-central Somalia. Reliable data on SGBV is lacking. Women and girls are often reluctant to report rape, including because of fear of reprisals by perpetrators, including government soldiers and allied militia; ostracism and stigma; lack of trust in the authorities; over-reliance on the informal justice system; and the limited medical, psychosocial, and legal services available to displaced communities. Women and girls in south-central Somalia more generally are also at risk of other forms of gender-based violence including domestic violence, female genital mutilation (FGM), and early forced marriage.[76]

International human rights law also contains protections from rape and other forms of sexual abuse through its prohibitions on torture and other ill-treatment, slavery, forced prostitution, and discrimination based on sex.[77] A state must refrain from, and prevent, sexual and gender based violence of all forms against IDPs, including rape and sexual exploitation.[78] The Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child contain additional protections for children.[79] International humanitarian law prohibits acts of sexual violence, prohibiting both states and non-state armed groups from committing rape and other forms of sexual violence.[80]

Human Rights Watch documented several cases of rape in the second half of 2011, mostly in Badbaado camp, in Dharkenley district, a camp that was established by the authorities in mid-2011 as a result of the influx of people into Mogadishu. Incidents of rape were also documented in 2012 in other camps and settlements, including Siliga camp in Wadajir district, Midnimo camp in Tarbuunka district, and Milk Factory camp in Hodan district. Data collected by local organizations working with survivors of SGBV showed an increased number of incidents of rape of displaced people, almost exclusively women and girls, in the second half of 2012. According to the United Nations, over 800 cases of rape were reported in Mogadishu and the surrounding areas between September and late November 2012.[81] Whether these numbers are the result of increased reporting, improved data collection, or an increase in incidents is unclear.

Human Rights Watch research found that armed men in uniform, including government-allied militia and government forces, have been responsible for a significant number of incidents of rape of internally displaced women and girls since July 2011. These included some security personnel who were posted in the camps to provide security. These accounts are supported by NGO and UN reports that conclude that armed and uniformed men, including government allied militias and men in TFG military and police uniform, are the main perpetrators of rape against IDPs.[82]

Quman M., 23, was nine months pregnant when she was gang-raped one night in Badbaado camp by men in TFG military uniform. She told Human Rights Watch:

Three men raped me, and another one was holding a gun on me. They raped me. They didn’t hit me, but they all raped me. I was sleeping and I woke up to discover that someone was pointing a gun on me and a flashlight in my eyes. When I got up, they told me to keep silent and when they all finished they left me. When they were leaving they were in uniform, they wore the mixed light brown uniform of the forces, which the military people wear. They were young men, they were not old men. One of the men was arrested the same day… he was released the same day. When they raped I finished the ninth month of my pregnancy. The pain, which started when they raped me, never left me until I delivered the baby.[83]

According to the United Nations, around 30 percent of victims of sexual violence are girls younger than 18.[84] A Somali NGO working with victims of SGBV noted that girls aged between 12 and 17 are particularly vulnerable to abuse.[85]

A significant number of incidents of rape take place at night, when women and girls are in their huts or makeshift shelters.[86] Safiyo Y., 25, was raped and shot in the leg by a government soldier in Siliga camp, Wadajir district, in the section of the camp that is controlled by Hawadle militia, on October 19, 2011, while she slept in a hut next to her husband.

It was midnight. I was sleeping with my children. I woke up as he [a government soldier] started to open my legs and came in me. … I resisted and I tried to run from him and I screamed. People woke up, and he shot me with four rounds.[87]

Safiyo Y.’s leg had to be amputated.

A 30-year-old blind woman was in her hut in the same camp when she was attacked by an armed man on the night of October 18, 2012:

Three days ago, I was asleep with my children and I heard noises. A man pointed a gun at me then he hit me on the chest with the butt of the gun and the forehead and then he strangled me. I told him: “What do you want? Can you not see I am blind?” and he told me not to make a noise. He later raped me inside my tent. My child is traumatized.[88]

IDPs and local organizations told Human Rights Watch that incidents of rape increased during food distribution as armed men, including government soldiers and militia, come to the IDP areas to get food.[89]

Displaced women and girls and their families have limited means of protection against rape given the context of insecurity in which they live. The destruction or absence of traditional protection mechanisms, especially clan protection, that occurs from being displaced contributes to their vulnerability along with lack of shelter, access to livelihoods, and the culture of impunity that has characterized the conflict in Somalia.[90] The presence of a male relative does not always protect women against abuse; in fact, male relatives are often powerless in the face of armed men. A 25-year-old woman was gang-raped by four armed men in government uniform in Badbaado in front of her husband. She said:

It was 1 a.m. I was sleeping and my husband was sleeping. Two men stepped over my husband. One stood at the side of my head. He held a gun on my heart and told me not to move and not to shout. After the other came from my legs he handed his gun to the one standing at my head.

The two others stood over my husband, one from the legs’ side and the other at his head. They took my husband out of the room. The room [in the makeshift house] was too small. The men tied my husband’s hands back, and blindfolded him. They put a piece of cloth in my mouth to prevent me from shouting, and they covered my eyes with a sheet and they all raped me unkindly. They treated me very awfully.[91]

Traditional clan protections for weak clans and minority groups from outside Mogadishu, such as the Rahanweyn, no longer appear to function in Mogadishu. So women and girls from clans that are weak clans in Mogadishu are particularly vulnerable. One of the few ways for women, girls, and their relatives to prevent the abuses is to flee the camp. The prevalence of rape in Badbaado camp led many IDPs to leave the camp in late 2011 and move to other settlements or IDP areas in the town.[92]

A major reason that the numbers of women and girls that have been subjected to sexual violence in Mogadishu’s IDP camps is likely to be much higher than reported is that victims fear the social stigma of reporting rape, reprisals from their attackers, or do not know their rights. A 70-year-old woman living in Midnimo camp who escaped an attempted rape explained:

The women hide their cases because these people are illiterate and came from the rural areas. They have no idea about the cities, and are surprised that they are attacked and raped by men in the government uniform. So they feel ashamed to say they were raped. Everyone raped runs from the camp to hide herself from people who know her case, and they don’t want any more people to know about it.[93]

Similarly, a 14-year-old girl living in Amara camp in Tarbuunka who was sexually assaulted by boys in the camp and a relative of the gatekeeper described the particular social stigma facing girls who are raped:

In Somalia to break your virginity with rape is humiliation. It can change the rest of your future. Such girls will never get the man they love. They end up dead or turn to become prostitutes.[94]

Staff from a local NGO working with SGBV survivors described the insecurity in which IDPs are living as one of the main reasons more do not come forward to file a complaint or seek redress.[95] The father of a young woman who was raped by four men in government military uniform said: “We don’t know anyone here. We are new to Mogadishu, so we didn’t try to go to justice, because the commander was harassing us at the time my daughter was raped. So how I can trust anyone here? We must keep silent.”[96]

While Human Rights Watch did not carry out a thorough assessment of services available to survivors of rape, UN and NGO staff raised serious concerns about the lack of services, particularly medical services and medication, available to survivors of rape. In 2013 a displaced woman who alleged that she was raped by members of the military was arrested, interrogated without access to a lawyer, and then presented by the police to the media. The case highlighted both the dangers inherent in reporting abuses by security forces and the police’s lack of capacity to provide appropriate response to victims of sexual violence. Furthermore, the prosecution used what they claimed were the woman’s medical records, as she had sought medical assistance following her alleged rape, against her in court, raising further questions about the ability of service providers to guarantee privacy and confidentiality.[97] Research on SGBV in contexts around the world shows that a lack of available services discourages victims from coming forward.[98]

Mistreatment and Discrimination

Those whose mobile phones are robbed are Digil and Mirifle. Those who are in trouble are Digil and Mirifle. They are my people, so we think that we are punished in the camp because of our ethnicity, and when we were taken there we thought a government was handling our problems. We never thought clan militia in government uniforms would oppress us. [99]

—33-year-old IDP man, Badbaado, September 3, 2011

Displaced people living in the camps investigated by Human Rights Watch reported various abuses that have become part of their daily lives in Mogadishu, making their precarious existence even more difficult.

Human Rights Watch heard numerous allegations from displaced people that militias controlled by or linked to gatekeepers, district commissioners, including militias linked to the government, committed routine abuses, including beatings, against displaced people living in camps.

Displaced people living in several camps in Tarbuunka in Hodan district that are run by a gatekeeper also known as Saredo and her husband Gardhere, said that militias working for Saredo routinely inspect IDP tents donated by Turkish NGOs, and beat IDPs whose tents they deem dirty. [100] “My husband also was beaten with the back of the gun,” a displaced woman in one of her camps told Human Rights Watch. “They came to us and told him that the tents are for them so that we must keep them clean. He resisted and told them that some white people gave the tents to us, and it’s ours, not theirs, and they beat him.” [101]

In Rajo camp, the militia controlling the camp, which is under the command of the Wadajir district commissioner and one of the divisional leaders, also beat IDPs, especially during distributions. According to Getachew S., 42, the militias beat up IDPs soon after the district commissioner completes his inspection of food distribution. They start beating people again as they are lining up to receive food. He said that, “The security forces don’t beat the people when he [the district commissioner] is there. They fear him, but when he is gone they start dealing with the people very wildly. They beat us.” [102]

Abuses against IDPs are at times directly linked to their clan identity. They are discriminated against and abused by gatekeepers, militias, and local authorities.

Human Rights Watch heard from IDPs that militias linked to district commissioners and others verbally abuse Rahanweyn IDPs. They are called “Elay” (a sub-clan of Rahanweyn). They are also accused of being al-Shabaab supporters.[103] Al-Shabaab is reported to have recruited a significant number of supporters and fighters among minority groups and the Rahanweyn.[104]

In both Badbaado and Rajo camps IDPs described being verbally abused by the heads of security and their militia while being beaten. A traditional elder at Badbaado camp told Human Rights Watch:

The Dharkenley district commissioner came to us, bringing some 40 men in police uniform. He told us that they are the police guaranteeing our safety, and that Captain Jimale [camp commander placed in the camp by the Dharkenley district commissioner] will be the commander and he will be the chief of the camp. We welcomed that because we thought that they will secure us and will help us.

But things changed soon. The policemen started to beat the people aimlessly. When some food aid came and the people start to gather around the delivery cars, they started beating the women and children, and they started insulting us. They said to us, “You are from Bay and Bakool regions. You are al-Shabaab’s people. You are not displaced by drought, you are cursed people.[105]

Displaced elders also said that camp commanders and government-affiliated militia justify actions aimed at preventing the displaced from mobilizing or complaining about abuses on the basis of their clan identity. One of the Rahanweyn elders in Badbaado said:

When we saw what is going on, we discussed and formed a committee among the displaced people in the camp. We recognized that the police Captain [Jimale] and his supporters in the camp are discriminating against us as a clan, because we [all the displaced in the camp] are from Rahanweyn clan, we are from Middle Shabelle, Bay, and Bakool regions, and his locals are from Da’oud sub-clan of Abgal.

So Captain Jimale was very angry. He arrested us, he kept us in a tent all the night, our hands were tied back, and he denied us any food. He told us that we can’t organize anyone in the camp, we can’t talk to the media, and we can’t enter his office in the camp unless he ordered us to enter.[106]

Similarly, a man was beaten and insulted by the Wadajir district commissioner’s militia that controls Rajo camp. He told Human Rights Watch:

I tried to go to the camp commander, Mohamud, and tell him about the abuse on my son and wife, but he ignored me. And when I tried to inform him about what happened his soldiers tried to beat me. They said to me, “You shit Elay, leave here.”[107]

A displaced man in Rajo camp described the sense of helplessness men feel in the face of abuse by armed camp security:

They [the district commissioner’s militia] beat the women when they collect the water, when we are in line for the food distribution, when the women go for collection of firewood, and whenever they see them passing in the camp. They say, “Here is not your region, why are you here?” Sometimes, we follow the women when they go collecting firewood. We can stop the neighbors from beating them, but when the camp security or administrators beat them we can’t stop because they have guns and they arrest us when we intervene.[108]

A government soldier spoke openly to Human Rights Watch about the discrimination that IDPs face at the hands of gatekeepers and militia and also pointed to the lack of government protection for Rahanweyn IDPs:

The IDPs who fled from Bay and Bakool regions speak a different dialect. Sometimes they are despised, sometimes they are denigrated by the camp administrators, who insult them all the time. They have no representation at all. Their most senior person in the government is the [former] speaker of parliament and … he never visited them. So who cares for them if they have no representation of their government people?[109]

Several IDPs and a member of the governmental Disaster Management Agency described how in Badbaado in late 2011 Captain Jimale would offer tents left vacant by IDPs who had fled the camp because of insecurity, for which his militias were in part responsible, to members of his own clan.[110] Nadif M., a 66-year-old man from the Bakool region, thought this was a deliberate strategy: “The attacks seem like a tactic of displacement, because when we feel threats and some of the people run because of fear, some people from the captain’s clan replace the people who left.”[111]

Evictions

In addition to serious physical abuses, in 2012 displaced families, especially those living in government or private buildings, have increasingly been forcibly evicted from their homes. The reason appears to be growing pressure on land and property in Mogadishu. According to the United Nations around 13 percent of all displacement in Mogadishu is the result of evictions ordered by the government and by private landlords.[112] The report states that, “Earlier in 2012, long-term internally displaced people were forcibly evicted from public buildings in Mogadishu, thus creating a homeless population in the capital.”[113] The evictions often take place with little or no warning, through threats, and with no alternative viable living arrangements provided for the displaced.

The UN Guiding Principles provides that the internally displaced have the right to basic shelter and housing,[114] and the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose their residence.[115] The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Somalia is a party, guarantees the right not to be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with one's privacy and home.[116]

The authorities’ failure to provide residents adequate notification before evicting them is inconsistent with recommendations made by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which calls on governments to ensure various procedural safeguards in cases of forced evictions.[117]

In May 2012, TFG forces moved into al-Adala camp with a “technical,” a vehicle mounted with anti-aircraft guns, and ordered IDPs to vacate. They were not given any prior warning, according to an international aid worker.[118]

In October 2012 several families living at the Banadir High School building and compound in Hodan district were evicted by the district authorities and the local police. The majority had lived in the area for years. The IDPs were given a day to vacate the area. At least four displaced men who went to the district commissioner’s offices to complain were arrested by the police and briefly detained at a local police station.[119]

IDPs from Banadir High School who had been forcibly evicted told Human Rights Watch about not having been given new shelters.[120] One said:

My home was destroyed by the commissioner of Hodan district. He destroyed my house with his bulldozer. Many troops including his bodyguards were taking part. I went to the office of the commissioner several times and requested that my belongings should be taken to a suitable place for me. After they destroyed my home they said to me, “We will give you a tent as shelter,” but I have received nothing from them.[121]

Diversion of Food Aid and Control over Resources

In addition to physical abuses, internally displaced people in Mogadishu face ongoing violations to their rights to food and shelter as a result of diversion of humanitarian assistance at the camp level. Food aid is stolen by a range of actors at the camp level, including government forces, government-allied militia, and private individuals. Shelter is also used to control IDPs movement. Tents are controlled by gatekeepers with the help of their militias.

As noted above, the government has the primary responsibility to provide assistance and protection to the displaced and to seek and facilitate access for international humanitarian organizations where the government is unable to provide adequate resources.[122] The government needs also to protect other fundamental rights, such as the right to housing[123] and freedom of movement.[124]

Looting, Diversion, and Misappropriation of Food Aid

At the camp level, gatekeepers and their militias, government allied-militia, and local authorities use different means to steal assistance that arrives at the camp. These include looting, setting up “ghost” camps, manipulating lists of IDPs who are due to receive assistance, determining access to ration cards, and wrongfully distributing or selling ration cards. Humanitarian agencies told Human Rights Watch that gatekeepers have circumvented monitoring mechanisms of humanitarian agencies and restricted access of journalists.[125] Gatekeepers also demand payments from IDPs as a form of “rent.” These payments are to gatekeepers and sometimes also landowners in exchange for supposed protection or access to land. As one international NGO staff member described it, “There is nowhere that an IDP can live for free.”[126] While payment of rent is not itself an abuse, the displaced who cannot afford to pay for shelter have a right to be accorded assistance by the authorities. If the authorities are unable to provide such assistance, they should seek assistance from humanitarian agencies and international donors.[127]

Many of the IDPs interviewed by Human Rights Watch in 2012 described severe food shortages that often were a result of diversion and misappropriation of food aid by gatekeepers and their militia. As a 30-year-old woman in Kheyr-Qabe camp at Digfeer hospital said, “There is nothing worse than the situation we are in. Now all we want is to get a car and return to our villages, because if I can die here because of food aid diversion, I can also die in my village, because death is death.”[128]

An IDP in one of the Saredo camps in Tarbuunka described the level of diversion and the efforts by gatekeepers to make a profit out of assistance: “Water tanks bring water, and we get it. We have no water shortage, but we have nothing else. They don’t steal the water, because they can’t sell it. If the water would cost money they would steal it.”[129]

Human Rights Watch also documented several incidents in the initial phase of the famine when TFG forces and militias, including government affiliated militias, used deadly force to loot dry food aid.

On August 5, 2011, seven people, including two displaced women, were killed when a militia linked to Yusuf Kaballe, the Dharkenley deputy district commissioner, started looting food aid brought to Badbaado camp by the WFP, prompting a clash with militia guarding the camp.[130] The deputy district commissioner and his militia reportedly refused to allow WFP to distribute the food unless 5 of the 13 trucks were handed over to him.[131]

Human Rights Watch witnessed another incident of looting of rice, flour, and oil supplies. On September 27, 2011, Zamzam Foundation, a Somali humanitarian organization, distributed food at Sayidka camp in Wardhigley district.[132] Once the displaced people had received their rations, pro-government militia in charge of security at the presidential palace, who were overseeing the distribution, started firing in the air, creating chaos. Outside the camp, men with donkey carts were waiting, and started looting the rations of the more vulnerable people, especially unaccompanied women, once the chaos broke out. Other women who were not IDPs but had also received rations were accompanied by armed men and were not targeted. The looted aid was loaded onto the donkey carts that then headed off towards Hamerweyne market. This incident took place only one kilometer from the presidential palace, in an area packed with AMISOM and TFG forces, but no one intervened.

Sayidka (or Beerta Darwiishta) camp is the biggest IDP camp in Mogadishu’s Wardhigley district. A week after this photo was taken in September 2011, government-affiliated militias fired into the air and forcibly looted food aid from the camp. Despite the camp’s close proximity to the presidential palace, government forces did not intervene. © 2011 Private

While more frequent in the initial phases of the 2011 influx, reports of looting continue.

On October 22, 2012, militia associated with the deputy district commissioner of Dharkenley, along with residents living near Badbaado camp, reportedly looted food destined for dozens of households from Badbaado following a distribution by the Turkish Red Crescent.[133]

Controlling the distribution of ration cards has been a common method used to control and misappropriate assistance at the camp level. Displaced people in numerous camps, including the Tarbuunka camps of Hodan district and Rajo camp in Wardigley, described the misappropriation of ration cards to Human Rights Watch.

There are many different ways that gatekeepers acquire ration cards. Gatekeepers often insist on being in charge of allocating ration cards, and according to the 2012 UN Monitoring Group report, new NGOs and donors, such as Turkey and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation countries, are particularly likely to ask or allow gatekeepers to distribute ration cards.[134] One aid agency said that they distributed a certain number of ration cards to gatekeepers in order to prevent them from exploiting or threatening IDPs.[135] Other gatekeepers insist on getting a share of ration cards from the IDP committees, as one IDP from Siliga described: “We have a leader [from the refugee community] who distributes food. The district commissioner decides where the food distribution points are. Our leader will inform us but then the gatekeeper comes with us. Our leader takes cards to her but if he gives her two she asks for more.”[136]

There can be serious consequences when aid workers refuse to accommodate the demands. A Somali NGO told Human Rights Watch that a staff member was temporarily arrested in Badbaado and taken to the local police station in August 2011 after having refused to give ration cards to the deputy district commissioner’s militia.[137]

A former member of the Disaster Management Committee described the corruption around the distribution of ration cards and placed much of the blame on poor monitoring and lack of accountability: “Everyone comes and distributes some food and people are still hungry, because they give some small cards to some IDPs and they give the rest of the cards to their friends and relatives. The reason is that there is no mechanism to monitor and [deliver] justice and there are no people responsible for it.”[138]

It is not only the gatekeepers who benefit, but also their militia, or the locally based militia, as well as government soldiers. Sometimes ration cards are given in exchange for providing security but they are also provided as a preventive measure to stop armed groups from looting assistance and committing other abuses. A gatekeeper from the Tarbuunka area told Human Rights Watch:

The security for distribution is bad. If you don’t pay something then they come at nighttime and commit rape. I had a problem with the security. One week ago, they came in the night, pointed guns at us, stole mobile phones... some in TFG uniform, others in normal clothes, you don’t know where they are from.

I have a relationship with two of them—militia. I pay them, and they manage the security. You give him something and ask him to watch his colleagues. In terms of food distribution we give them three cards. Sometimes we collect money when the situation is really bad. I give them around 20 dollars or I buy them khat [a mild stimulant]. There is no fence in our camp, so they can come in and rape any time. It happens around two or three times a week.[139]

According to an IDP elder, even in Badbaado in late 2012, where security was provided by the police, militia got their share of the food assistance and cards during distributions:

The other militias are around—the DC’s [district commissioner] militia, ASWJ [Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama’a]. But they don’t cause too many problems. They are clan militias and there is something for them [food] when distributions happen, to secure the other food. They must be given their share. Each militia man has a card, or is given a card. They are a small number, about 40 or 50. They only come once food is brought there.

A government soldier described to Human Rights Watch how the camp administrators would also give them cards:

If we try to stop food diversion from the camp administrators or any other person involved in it, we will be the losers, because they are giving us the cards just to bribe us.

I am a soldier, I can’t take responsibility. The Somalis say, the hungry man is not responsible for anything, so all the problem is the hunger that affects everyone.

I am sure the people who fled from the drought areas are very weak and deserve to get the food aid. I agree with that, but, suppose if I stop taking the food aid, which is like 100 kilograms, and all the people are not stopping? I will be the loser. But if all people stealing the food start to stop it in favor of the suffering people in the camps, I will be the first to stop.[140]

Numerous displaced people and aid workers described how gatekeepers as well as their militias would distribute cards to relatives or other individuals who were not part of the IDP camp population. An IDP from Sayidka camp said, “The soldiers want to get the cards. They want to distribute a very small amount and they call their people with mobile telephones and collect the food for them, and they take the food out for them.”[141] Displaced people and local NGOs highlighted the link between food distribution and the presence of militia, with the head of a local NGO calling Badbaado in its early days “a militia market.”[142]

Aid workers also reportedly come under pressure from government officials and district authorities to hand over ration cards to their relatives. A food distributor working for a Turkish NGO explained: “Some government officials call us. They recommend some of their relatives. They request us to give cards to them, [which] we must accept. Each of the officials wants to ask you to give five to seven cards to the people they recommend, so we accept it.”[143] And yet, he also admitted being part of the very same system: “I am not different from those taking the meat from us, we have relatives and friends and neighbors. They know that we are distributing meat, and they visit us in our houses at night and we give them cards.”[144]

Even obtaining a ration card is not always a guarantee that the displaced people can access assistance because the food distributed to them through ration cards is often taken away. In several camps in the Tarbuunka area, including Bisharo, Ufarow, Madlamo, and Kheyr-Qabe camps run by a gatekeeper that IDPs refer to as Fadumo, displaced women are made to line up to receive food aid from a Middle Eastern NGO and for the cameras. But when the agency representatives and the cameras left, the sacks would be taken by the camp militia. The women would be given 100,000 Somali shillings (US$4) by the gatekeeper, significantly less than what the assistance was worth. One displaced woman told Human Rights Watch: