Blood on the Streets

The Use of Excessive Force During Bangladesh Protests

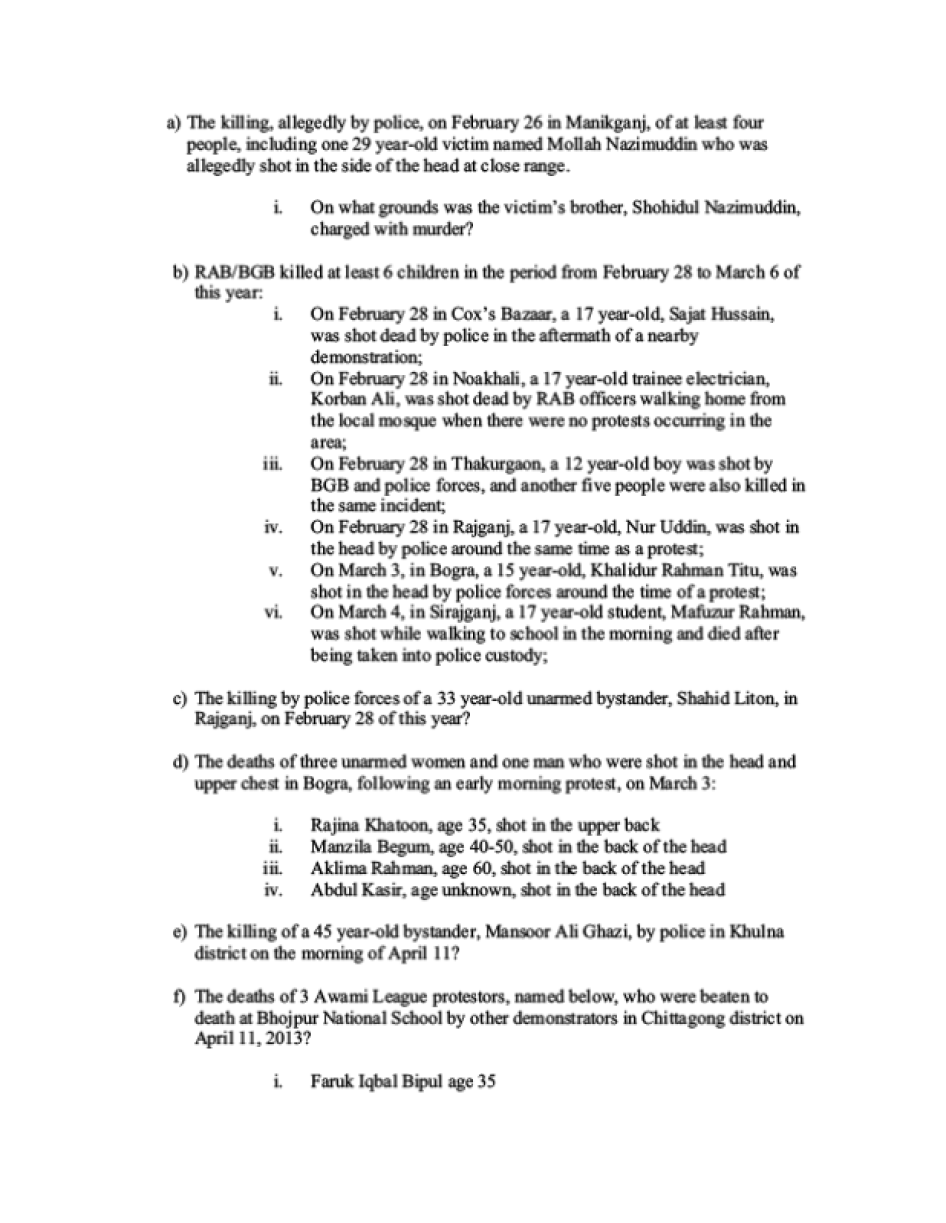

Map of Bangladesh

Map depicting locations of some of the largest clashes in Bangladesh since February 28, 2013. © 2013 Human Rights Watch

Summary

Huge demonstrations have resulted in two major episodes of deadly street violence in Bangladesh in 2013. From February to early May, more than 150 people were killed in the violence, including at least 15 members of the security forces; at least 2,000 people were injured.

Demonstrations were held in favor of and against verdicts handed down by the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) in January and February 2013. They were followed by even larger demonstrations in Dhaka in early May 2013 led by Hefazat-e-Islam, an Islamic movement. Some demonstrations were entirely peaceful; in others protesters threw rocks at or otherwise attacked security forces. In a few cases, officers were beaten to death.

In many cases, security forces responded to violence in an appropriate fashion, using non-lethal methods to disperse crowds. Yet in many other cases documented in this report, the police, Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), and the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) responded with excessive force, killing protesters and bystanders. Security forces used rubber bullets and live ammunition improperly or without justification, killing some protesters in chaotic scenes, and executing others in cold blood. Many of the dead were shot in the head and chest, indicating that security forces fired directly into crowds. Others were beaten or hacked to death. At least seven children were killed by security forces.

With regular hartals (strikes) called by opposition political parties in response to verdicts of the ICT and others likely in the run-up to national elections due by January 2014, there is a significant risk that Bangladesh could descend into a vicious cycle of violence and lawlessness. To avoid this, the government should institute new procedures to ensure that the rights to freedom of assembly and expression are upheld. Peaceful protesters and bystanders need to be protected from unlawful use of force and firearms by the authorities. Organizers of demonstrations and political parties should also take steps to minimize the risk of violence. Those responsible for abuses need to be held accountable.

ICT-Related Demonstrations and Violence

Violence broke out in Bangladesh on February 28, 2013, after the ICT, a domestic court set up to prosecute those responsible for atrocities committed during the country’s 1971 war of independence, convicted the vice president of the Jamaat-e-Islam party, Delwar Hossain Sayedee, of war crimes and sentenced him to death. This conviction followed the January 2013 conviction of Abul Kalam Azad, who was tried in absentia and sentenced to death after being found guilty of crimes against humanity, genocide, and rape. On February 5 the ICT found Abdul Qader Mollah, assistant secretary general of Jamaat, guilty of five of six charges, including crimes against humanity, and sentenced him to life in prison. Since then, the ICT has announced two new verdicts. Jamaat leader Ghulam Azam, 91, was sentenced to 90 years in prison for war crimes on July 16, 2013. On the following day, Ali Ahsan Mohammad Mojaheed, secretary-general of the party, was sentenced to death. The Mollah verdict was greeted with protests, initially centered in the Shahbagh neighborhood of Dhaka, demanding the death penalty. The Shahbagh movement, as it came to be known, was largely peaceful, though some protesters were attacked. The governing Awami League party supported the aim of the protesters and did not attempt to break up the protests.

The February 28 conviction of Sayedee led to demonstrations in Dhaka and districts around the country by supporters and opponents of the verdict. Those celebrating the verdict engaged in some vandalism and violence. Those protesting the verdict, including Jamaat members and supporters, also engaged in violence, leading to civilian and police casualties. Jamaat party officials acknowledged to Human Rights Watch that some of their members had been responsible for isolated incidents of violence. Human Rights Watch viewed footage of hundreds of protesters in Cox’s Bazaar who threw stones and beat on shop fronts with sticks as they passed through the town.

In villages and cities across the country, supporters of Sayedee, a well-known Islamic scholar and politician, took to the streets in protest. In Dhaka, Noakhali, Bogra, Chittagong, Rajganj, and dozens of other locations, hundreds of Jammat supporters and Sayedee followers joined the protests, some spontaneous, some organized in advance.

Eyewitnesses in each location described similar patterns. Protesters gathered in town centers, sometimes moving towards police stations and in some instances Awami League offices. Protesters were usually unarmed but were often seen wielding sticks or carrying rocks and broken bricks. In the majority of locations, eyewitnesses told Human Rights Watch that police initially tried to contain crowds using rubber bullets, tear gas, and other crowd control measures such as bird-shot, which releases dozens of small pellets when fired from shotguns. In many instances, however, this approach was short-lived, with security forces quickly transitioning to use of live bullets and non-lethal weapons fired into the crowd at chest and face height, causing deaths and many serious injuries.

A 20-year-old witness described to Human Rights Watch one such incident in Bogra, the morning after the Sayedee verdict:

Around 7:15 a.m. after prayers, my mother woke me up and asked me to go out to the street with her. There was a women’s procession. I was behind her in the procession and we all went towards the Shananpur local police station. People started throwing bricks and then the police started to open fire. The women were in the front of the procession, they were all sitting down in front of the police station in protest. My mother was among other women sitting.… First they used tear gas, and then they started firing. Everything was chaotic, once the police fired the tear gas, all the people started running in different directions. When they started firing the guns we ran.... For a half hour the shooting continued with pauses.… I saw about four people who died. One was a man, the others women. One of those killed was my mother. Many people were injured.

In some cases detailed in this report, witnesses described the police chasing protesters who participated in protests and executing them at close range.

Hefazat-e-Islam Demonstrations and Violence

A second round of violence took place in Dhaka on May 5-6, before, during, and after a rally by tens of thousands of supporters of a previously little-known organization, Hefazat-e-Islam (Protectors of Islam). Hefazat describes itself as a non-political grouping of religious bodies. Among its demands are a ban on the public mixing of the sexes, criminal prosecution of atheists, and the imposition of the death penalty for blasphemy.

Hefazat called for a national march on Dhaka to demand implementation of its 13-point plan. As crowds of religious students and teachers entered the city on May 5, many from the southern port city of Chittagong, violent clashes broke out between some protesters and security forces. Activists of the Awami League joined in, often facing off against supporters of Jamaat and the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP).

The worst violence took place near Dhaka's central mosque, Baitul Mokaram. Protesters set fire to shops, two office buildings, and a bus, and clashed with police. The security forces retaliated with tear gas, rubber bullets, and live fire. Video footage shows police officers using heavy sticks to beat apparently unarmed protesters lying on the street. Hundreds of people were taken to nearby hospitals. A 25-year-old Hefazat-e-Islam volunteer described the incident to Human Rights Watch:

We took shelter in the Baitul Mokarram mosque. The police called us to come out. When we did, they fired at us. Bullets hit my face, and when I fell down they came and shot me in my knee and abdomen and shoulder. They shot from barely 10 feet [3 meters] away. All were rubber bullets with lead balls. I was not armed, I did not have a stick. I was hit 19 times. I said to them, “Why are you shooting at me? I'm a volunteer.” Now I cannot see anything from my right eye, and after an operation I can see only a little bit from my left eye.

Some of the victims were bystanders, like shopkeeper Raqibal Huq, who died of a gunshot wound to the head. Most were Hefazat supporters like 20-year-old Saidul Islam who was killed by a sharp blow to the head, and 20-year-old Sadam Hussein, whose corpse had gunshot wounds and large cuts to the back.

Police officers were also attacked. One eyewitness in the Dilkusha area told Human Rights Watch that he saw a policeman being knocked to the ground by a group of Hefazat supporters. “It soon became quite grisly and there was blood everywhere,” he said.

By nightfall on May 5, many of the demonstrators had left the city, but about 50,000 had converged on the Shapla Chattar intersection in the heart of the city's central business district, Motijheel. There they held prayers and were addressed by their leaders. At 2:30 a.m. the security forces launched an operation to remove them. Hundreds of police, RAB, and BGB personnel took part in this action, which lasted several hours. They first used megaphones, asking the protesters to leave the area peacefully. Then, moving in from two directions, they used tear gas, rubber bullets, and sound grenades to disperse the demonstrators. Most fled the area, but others hid in side streets and buildings, which were then swept by the security forces.

The government and opposition parties have given widely-differing accounts of what happened next. Human Rights Watch found neither account credible. According to the opposition and Hefazat leaders, the police and RAB killed hundreds of protesters during the sweeps, before secretly dumping the corpses. Hefazat leaders later claimed that government workers picked up the bodies in garbage trucks and dumped them outside the city. They say they are compiling a list of the missing, but are finding it hard to do so because of harassment by the security agencies. According to the group's leaders, 2,000-3,500 people were killed by the security forces. Some opposition figures hyperbolically called it “genocide.”

The government, in turn, has described the Hefazat and opposition party claims as “grossly fabricated.” Foreign Minister Dipu Moni said that the security forces conducted a well-planned and disciplined operation, designed to minimize casualties. She denied that anyone was killed during the operation, saying that the police had recovered only the bodies of 11 people killed during the previous day's clashes.

While Human Rights Watch found no evidence to support the numbers claimed by the opposition and Hefazat leaders, there is strong evidence to dispute the government assertion of a disciplined operation. Journalists and protestors who witnessed the event told Human Rights Watch that on several occasions the security forces opened fire at close range even after unarmed protesters had surrendered. The security forces did not just fire rubber bullets, but also shotgun pellets. Many witnesses spoke of seeing corpses. As already noted, video footage shows police and RAB men beating what appear to be severely injured protesters.

One journalist remembers shaking 25-30 bodies and checking their pulses and is convinced some were dead. Another reporter saw RAB soldiers dragging four bodies near the offices of Biman Bangladesh airlines and loading them onto a truck. When he went to inquire about them, a soldier hit him with a stick on the side his head. The same journalist later checked the pulse of a boy who was lying on the steps of the Sonali Bank and was told by a police officer that the boy was dead. He remembers seeing a lot of bruising around his neck and chest.

One of the protestors described being caught in the violence:

They were raining bullets, tear gas and hot water down on us. It was a terrifying situation. I was with my brother and we tried to escape over a wall. They started beating us with sticks as we climbed over it. I jumped and broke my foot when I landed on the other side. As I tried to run away I was shot. Later, the x-ray showed that there were 102 pellets in my leg. I was not armed. I only had my prayer carpet and prayer beads. It was not aimless shooting, they were targeting us, they were aiming at us. The police were 2 to 3 meters behind me. It was not accidental fire.

Violence continued the next day as Hefazat supporters left Dhaka. Madrassa students supported by opposition activists blocked the main highway to Chittagong and attacked police and BGB officers, killing four. They burned down a police post and destroyed two RAB vehicles. The security forces retaliated, and video footage shows them firing shotguns at protesters. Local hospitals told reporters that seventeen people died that morning.

Based on hospital logs, eyewitness accounts, and well-sourced media reports, Human Rights Watch believes that at least 58 people died on May 5 and 6, seven of whom were members of the security forces. However it is likely the death toll was even higher. It is imperative that the government investigate all claims of people still reported as missing. While some could be in hiding, it is possible that others were killed.

Arrests and Intimidation of Protesters and the Media

Many Bangladeshis we spoke with believe authorities used spurious criminal charges to intimidate eyewitnesses and family members of protesters killed by security forces. In a number of instances after protests, police lodged criminal complaints from members of the public (called “First Information Reports,” or FIRs) against hundreds and sometimes thousands of “unknown assailants.” Police would then enter the communities where protesters came from, using the FIRs as justification for otherwise arbitrary arrests of scores of individuals, particularly of men thought to be Jamaat supporters. The sweeps left men in these communities fearful and drove many into hiding. A researcher from the Bangladeshi nongovernmental organization (NGO) Odhikar told Human Rights Watch that after the February 28 protests in Chittagong he visited three surrounding villages; all were devoid of men, presumably because, fearing arbitrary arrest sweeps, the men were hiding from police.

Following the Shahbagh protests, Awami League leaders, including the home minister, suggested that Jamaat should be banned and media outlets connected to the party closed.

The media faces increasing pressure. Several opposition newspapers and television channels were closed by government order during or after protests and incidents of violence. At this writing some have still not resumed operations. In an apparent attempt to cut off opposition coverage of the events, two television stations that support opposition political parties, Islamic TV and Diganta TV, were taken off the air by the government on the night of May 5-6 while reporting from the Hefazat protest.

In one of the most high profile cases, police arrested Mahmdur Rahman, the editor of the opposition news outlet, Amar Desh, and an advisor to the previous BNP government. Rahman was subsequently charged with sedition. Physical attacks on opposition media, including vandalism and arson, have also occurred with little to no investigation or action by police.

Activists have also been targeted. In April, four bloggers previously described as “atheists” by Amar Desh were arrested for posts criticizing what they characterized as an increasingly fundamentalist Islam. One of them, Asif Mohiuddin, had previously been attacked, he says, by Islamist extremists. Several blog sites were closed.

Government Response

While security forces have been quick to arrest hundreds of protesters and suspected Jamaat supporters, Human Rights Watch found no indication of any meaningful investigations by authorities into alleged security force violations, including unjustified or improper use of live ammunition, mass arrests, and extrajudicial executions. Human Rights Watch has requested but has not received any information about investigations into the deaths of protesters or bystanders, including children. The Bangladeshi authorities are obliged to investigate the use of live fire by security forces and hold perpetrators to account.

At its submission to the United Nations Human Rights Council in February 2013, Bangladesh said it would investigate “every incident of use of force or exchange of fire by police, RAB or other LEAs, even though [it] occurred in the course of authorized duty.” It also stated that:

An Internal Enquiry Cell, a special team trained and organized with the US Government support, investigates any incident of use of force or exchange of fire by RAB members.

However, as of June 2013, the observers, officials, and judicial system monitors we spoke with were not aware of any such investigations being established or any member of the security forces being prosecuted for illegal use of live fire. No member of RAB is known to have ever been successfully prosecuted for a human rights violation. The prosecution of those responsible for excessive use of force should be a government priority.

Human Rights Watch also urges Bangladeshi authorities to publicly order security forces to follow the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, which state that security forces shall “apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force and firearms,” and that “whenever the lawful use of force and firearms is unavoidable, law enforcement officials shall: (a) Exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offence and the legitimate objective to be achieved; (b) Minimize damage and injury, and respect and preserve human life.”

Leaders of political parties should also urge restraint and reject calls for violence during political demonstrations. Human Rights Watch calls on political leaders in Bangladesh to avoid rhetoric that would incite violence.

Key Recommendations

Human Rights Watch calls on the Bangladeshi government to:

- Immediately establish an impartial, transparent, and independent commission to investigate the large numbers of deaths and injuries that occurred in connection with protests between February and early May 2013. The commission should ensure that all perpetrators of serious human rights abuses are brought to justice regardless of their rank or political affiliation, and should make its findings public.

- Provide training to security forces, including in overseeing demonstrations, crowd control, and response to violent protests, as part of efforts to bring their performance into line with international standards.

- Immediately make public the number of persons detained in protest-related security operations, and ensure that all detained persons have access to legal representation and are treated in accordance with international due process standards. This includes ensuring all detainees are brought promptly before a judge and being promptly charged after the initial detention. For those properly charged and facing trial, pre-trial detention should be the exception, not the rule.

Methodology

This report is based on research carried out in Bangladesh from April to June 2013. Human Rights Watch conducted 95 interviews with victims and their family members, witnesses, human rights defenders, journalists, members of the diplomatic community, and lawyers.

The report also makes use of official statements and fact-finding reports prepared by Bangladeshi human rights organizations which were further investigated by Human Rights Watch. In some cases, Human Rights Watch was able to examine television and video footage of specific incidents documented in this report.

To reconstruct the events that occurred during the widely disputed crackdown on the Hefazat-e-Islam rally, Human Rights Watch interviewed eight journalists who reported on the security operation, including those working for organizations considered to be both pro- and anti-government, as well as international media outlets. Human Rights Watch also examined hospital records and conducted interviews with medical staff.

Interviews were done with the full consent of those being interviewed and all of the interviewees were told how Human Rights Watch would use the information provided. Given recent patterns of retribution against witnesses and some victims of the violence, we have chosen to withhold names to protect some of the witnesses.

Human Rights Watch received numerous other allegations of killings, disappearances, mass arrests, and attacks on religious minorities during this period, but due to resource and logistical constraints, we were unable to investigate or independently verify these allegations. They are not included in this report.

Human Rights Watch wrote letters to the office of the home minister, the prime minister’s office, and the ministry of foreign affairs in Bangladesh to raise concerns and request responses about specific allegations of human rights violations. Human Rights Watch received no response. A copy of the letter is included in the appendix to this report.

I. International Crimes Tribunal Protests and Related Violence

The International Crimes Tribunal (ICT), a specially constituted court set up to prosecute those responsible for atrocities committed during the country’s 1971 war of independence, began its operations after the Awami League came to power in 2009.

The ICT has handed down six judgments as of this writing. The first in January 2013 found Abul Kalam Azad, who was tried in absentia, guilty of crimes against humanity, genocide, and rape. He was sentenced to death.[1]

The second judgment, on February 5, 2013, found Abdul Qader Mollah, assistant secretary general of the Jamaat-e-Islam party, guilty of five of six charges, including crimes against humanity. Mollah was acquitted on one charge. He was sentenced to life in prison.[2]

When leaving court, Mollah flashed a “V” for victory sign to an assembled crowd and the media. Outraged that he appeared unrepentant and fearful that a future BNP government would release him, many segments of the public reacted with outrage, calling for Mollah to be hanged. Protests, centering initially in the Shahbagh neighbourhood of Dhaka, sprang up with hundreds of thousands of people demanding the death penalty. The Shahbagh movement, as it came to be known, soon became a flash point for existing tensions between various political factions in Bangladesh.[3]

On February 28, 2013, the ICT convicted the vice president of the Jamaat party, Delwar Hossain Sayedee, of war crimes and sentenced him to death. Immediately following this decision, protests broke out in Dhaka and districts around the country organized by both supporters and opponents of the verdicts. These demonstrations resulted in dozens of deaths of protesters, bystanders, and police officers.[4]

Thousands of people participated in protests, leaving security forces overwhelmed. Media reports and eyewitnesses described how protesters sometimes carried sticks and threw rocks and broken bricks at security personnel deployed to contain the violence.[5] In some instances, properties such as shops, motorcycles, and buses were vandalized and set alight.[6]

Killings of Police and Awami League Supporters

Between February and April 2013, members of Islami Chhatra Shibir, the student wing of Jamaat, and other Jamaat supporters reportedly killed three Awami League supporters and more than a dozen members of the security forces.[7] Human Rights Watch received reports that on February 1 in Jessore a police officer was injured in a clash with Shibir activists and died soon after.[8] On February 28 in Gaibhanda three police officers were beaten to death by protesters.[9] The following day two police officers were killed in Rongpur.[10] On April 11, one police officer was killed in a clash after police arrested a Jamaat activist for vandalism.[11]

In one case documented by Human Rights Watch, three supporters of the Awami League were beaten to death at Bhojpur National School on April 13 in Chittagong district. Human Rights Watch researchers received and verified video footage of this incident. The victims who were beaten to death were Faruk Iqbal Bipul, 35; Forkan Ali, 30; and Md Rubel Miah, 17. According to local human rights defenders, 32 people were arrested in connection with the deaths and are facing charges in the Chittagong Judge’s Court, but police have not released information about the specific charges, citing the “sensitive” nature of the information.[12] The police also booked complaints against 3,000 “unknown assailants” in connection with the killings as well as damage to property that occurred during the attack.[13]

On March 1, following vandalism against Jamaat businesses by a group of Awami League supporters, Jamaat supporters killed Saju Mia, 30, and Nurunnata Sapu, 22, both supporters of the ruling Awami League.[14]

Killings by Security Forces of Protesters

Human Rights Watch documented 18 incidents between February 28 and March 6 in which protesters and bystanders were killed by live ammunition fired by security forces, including the police, BGB and RAB.[15] In many cases security forces first used non-lethal weapons in attempts to disperse crowds, but then used live ammunition, often firing directly into or indiscriminately at crowds and areas around the protests.

Human Rights Watch viewed video footage from one such incident in Bogra where police were seen firing tear gas before firing live rounds into the protesting crowd, killing four people.[16]

The family member of one of the victims described the incident to Human Rights Watch:

The procession was not called by any political party. People regardless of their party affiliation were there to protest Sayedee’s death [sentence]. When we went toward the town we were chased by police…They shot the tear gas. When the protesters started running in the other direction, the police started shooting, instantly they started shooting….

The sound was continuous “rap-rap-rap” for 10 minutes … Four people died … Two people died because of injuries to the head, one woman and a man called Abdul Kafi. It was bullet wounds, I saw the bodies.[17]

In the majority of casualty cases researched by Human Rights Watch in which security forces used live bullets, they did so in a manner likely to cause death or serious injury. In 13 of the 18 such cases we documented, victims were killed by bullet wounds to the head and upper body, suggesting security forces had fired directly at them.[18]

Manzila Begum, a clothes seller, and five other victims killed in a protest on March 3 in Bogra were shot from behind while trying to flee a protest, according to two witnesses. As a family memberof Manzila Begum recounted:

[She] was at the front, she was one of the first women to get shot. The bullet wound was in the back of the head and exited right underneath the eye. I heard it from the people who washed the body and I saw her body myself.[19]

Human Rights Watch viewed video footage from the scene which showed the five killed protesters being taken from the scene with visible wounds to their heads and upper bodies.[20]

17-year-old Saiful (not his real name) described another incident, this one in Kashipur village in Ranjpur district on February 28:

We couldn’t tolerate the tear gas—that’s why we started throwing stones and bricks at them. That’s when they came and started shooting live bullets. There were about 10-15 BGB and 10-15 police. We were not too far away….

There is a raised platform in the middle of the market area. Two of the BGB officers went and stood on top of it and started firing from there…. When they started shooting two people behind me got shot, one of them near the ear, one in the throat.[21]

The firing of live ammunition at protesters appears to have most often occurred when police felt overwhelmed. In Noakhali, a local human rights worker told Human Rights Watch that on February 28, police at Begumganj police station opened fire on hundreds of protesters after protesters tried to remove roadblocks and threw stones at police. Consistent with the pattern seen across the country, police responded initially with tear gas, but quickly switched to live bullets. The officer in charge of the police station said that police used 24 tear gas rounds, 215 shotgun rounds, and 11 rifle rounds, which resulted in the death of at least one protester who was shot in the chest.[22]

In another incident, SB described how her 33-year-old husband, Liton, was shot while trying to find his 11-year-old son, who had gone to watch a protest in Noakhali.

He left home at 4 p.m. We have an 11-year-old boy, who was over near the protest, and my husband went to bring the boy back and that’s when my husband was shot and died. My son is young and was probably curious…. We heard noise from the protest, my husband went out because we realized my son was there.

Two people died there that day, my husband died on the spot. He was shot in the forehead on the right side above the eyebrow…. I was discouraged by people around us to file a case, because I have three children, and I would probably get into more trouble, and I heard from everybody that the police wouldn’t let me file a case. I’m more worried about my children.

There was no investigation, the police came to our house around 9 p.m. to take the body, and we had to pay money to get the body back. One of my brothers-in-law and a cousin went to get the body back…They had to pay 2500TK (US$32) bribe to the constable to get the body back. [23]

Demonstrators on several occasions carried crude sticks, stones, and broken bricks, and in some instances even used low impact explosive devices, but in the 18 killings by security forces investigated by Human Rights Watch, we found no evidence that the victims had been armed at the time they were killed.[24]

The firing of live ammunition into crowds at head and chest height strongly suggests illegal, excessive use of force. Under international law, the Bangladeshi authorities are obligated to use lawful means, including force proportionate to the level of threat or legitimate objective. The United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials provide that all security forces shall, as far as possible, apply nonviolent means before resorting to the use of force and firearms.[25] Whenever the lawful use of force and firearms is unavoidable, the authorities must use restraint and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offense. Lethal force may only be used when strictly unavoidable to protect life. The Basic Principles also call for an effective reporting and review process, especially in cases of death and serious injury.

In its February 2013 submission to the UN Human Rights Council, Bangladesh pledged to investigate “every incident of use of force or exchange of fire by police, RAB or other LEAs, even though [it] [occurred in the course of authorized duty.” It also stated that, “An Internal Enquiry Cell, a special team trained and organized with the US Government support, investigates any incident of use of force or exchange of fire by RAB members.”[26] However, as of June 2013, Human Rights Watch was not aware of any such investigations being undertaken into alleged violations by RAB or other security forces in response to the violence in 2013.

Security Force Shootings of Bystanders, Including Children

Human Rights Watch documented the killing of nine bystanders in separate incidents, seven of whom were children. Those killed were Sajat Hussein, 17; Korban Ali, 17; Masoor Ali Ghazi, 45; Mafuzur Rahman, 17; Nur Uddin, 17; Kokohon Ali, 16; Rubul Islam, 12; Niranjan, 12-13; and Shahid Liton, 33.

According to eyewitnesses, the nine bystanders were not involved in the protests or in any clashes with security forces. Eyewitnesses and family members of three of the child victims said the children were standing in or within the perimeter of a school or madrassa the time of the protests.

In Chongakhata, a family member of one of six victims shot by BGB officers who witnessed the killing described how two 12-year-old boys, Sayed Rubul Islam and a boy known as Niranjan, were shot while standing in front of the madrassa they were attending, watching a protest.

First it was the police, but they didn’t have weapons, then they called the BGB. In 10-15 minutes they first used tear gas and then rubber bullets….I didn’t hear any announcement and then the BGB pointed their guns and there was 10 minutes of continuous shooting. The two boys died on the spot, they were outside their madrassa watching, there were thousands of people. [Sayed] was hit on the right torso, the bullet entered there and exited his back.[27]

Human Rights Watch also documented one case in which police officers, responding to protest violence in Cox’s Bazar on February 28, pursued and killed 17-year-old Sajat Hussein. The victim reportedly had gone to the market to photocopy documents for upcoming exams and took shelter in a family member’s market stall as police began firing on a nearby protest. As he saw police pursuing protesters through the market, he ran to the roof to seek refuge. An eyewitness to events leading to the killing told Human Rights Watch:

There were 7 or 8 policemen … They were firing long weapons, rifles and revolvers in the air … The processions dispersed and there were people running. He [Sajat] ran through the police and was scared and ran up the stairs to the rooftop on the 2nd floor. One or two people ran up behind him. A police officer followed him; it was only one officer carrying a rifle, the rest were downstairs. I heard a gunshot and I noticed the other guys who had gone upstairs run away. I didn’t know my nephew had been shot. After everyone left l went upstairs … I found my nephew with a shot in the left temple on the rooftop … I heard a single gunshot…. There were no bruises, but there was a lot of blood, the side of his temple was missing, it was blown away.[28]

In at least two incidents we investigated, the victims appear to have been arbitrarily pursued or targeted outside of protests. On March 1 in Silyet, Noakhali district, eyewitnesses described how members of RAB 11 shot and killed 17-year-old Korban Ali near a mosque after Friday afternoon prayers. According to an eyewitness at the scene:

RAB stopped the car, two RAB officers got out with guns…. We saw them draw. They fired 7 or 8 times but only one hit Korban Ali. I saw him on the ground with blood coming from his head … They continued to shoot … When the RAB stopped shooting they dragged him like a carcass and flung him into the car.[29]

A 19-year-old man and a 17-year-old girl also sustained injuries in the incident.[30]

In another incident, Mafuzur Rahman, a 17-year-old boy from Folia Village in Sirajganj district, had been walking to tutoring classes on the day of a protest when he was shot from behind. According to his father, who saw the body and spoke to multiple eyewitnesses to the killing:

He used to go to tutoring at 6 a.m…. On March 4, 2013, like every other day, he had gone to tutoring with friends. There was a hartal [strike] and there were police and other law enforcement around. He was walking to the tutoring center and he was shot from behind. After he was shot other boys and girls tried to stop the bleeding. Police then took him. He had bruises to his throat, bruises on his back torso, and a bullet in the left thigh.[31]

Mafuzur Rahman’s body was taken by police officers to the Ullapara Hospital where he was seen by medical staff, still conscious. Police then removed him from the hospital against the advice of medical staff. His body was found less than an hour later in the car the police had used to transport him.[32] His family has received no explanation, and there does not appear to have been any investigation by the police.

Disappearances

Human Rights Watch received multiple reports of individuals last seen in security force custody, or in the custody of men believed to be acting at their behest, who have not been seen since. This includes regional and local Jamaat leaders allegedly “disappeared” in an effort to quell opposition voices. Due to security and movement constraints, Human Rights Watch was not able to investigate all of these reports.

The abduction and “disappearance” of political opposition figures is not new to Bangladesh. Another case more widely documented in the media in Bangladesh was the 2012 abduction of BNP leader Ilias Ali, who has not been seen since.[33]

Human Rights Watch is not able to quantify how many “disappearances” took place during the period of our research, but we received multiple reports of abductions which require further investigation. Bangladeshi authorities should abide by their obligations as a signatory to the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which prohibits enforced disappearances.[34]

II. Violence Related to the Hefazat-e-Islam Rally, May 5-6, 2013

A previously little-known organization, Hefazat-e-Islam (Protectors of Islam), has recently played a leading role in Bangladesh in campaigning for strict adherence to Islamic teachings in all aspects of life.[35] The organization says it is a non-political grouping of religious bodies, but some of its members have ties to segments of the opposition.[36]

Hefazat’s leader, Ahmed Shafi, is a 93-year-old religious scholar from Chittagong, who oversees thousands of madrasas.[37] Hefazat claims that Bangladesh is turning away from Islam and it opposes the secular policies and principles promoted by the governing Awami League.[38] It has campaigned for implementation of its “13-point demands” that includes a ban on the public mixing of the sexes, criminal prosecution of atheists, and imposition of the death penalty for blasphemy.[39]

Hefazat launched its campaign in the aftermath of the Shahbag Movement, accusing some of its organizers of being atheists and insulting Islam.[40] Government supporters believe that Hefazat wants to destabilize Bangladesh ahead of national elections due to be held by January 2014.[41]

On May 5, an estimated 200,000 Hefazat supporters held a rally in Dhaka to push for their demands. The security forces broke up the demonstration early the next morning. Precisely what happened on May 5 and 6 has become hugely controversial in Bangladesh.

The opposition BNP has accused the police of killing hundreds of protesters, describing their actions as a “genocide.”[42] It alleged that the government turned off the electricity in the area where the demonstration was taking place so that the police could kill protesters in the dark. It also claimed that two opposition-funded news channels that had shown footage of corpses were raided and ordered to stop broadcasting as a way of hiding the violence from the public.[43] The leaders of Hefazat also accused the government of a cover-up:

Corpses have been removed and transported to (an) unknown destination by municipal garbage trucks, transport trucks, covered vans, pickup(s) all loaded with corpses. Many apprehend the number of corpses can rise from 2500 to 3000. Materials of proof have been removed quickly from the place of genocide. Thousands and thousands of people have been wounded.[44]

Mohammed Ahlullah Wasel, a spokesman for Hefazat and Islami Oikyajote, a party allied to the BNP, told Human Rights Watch that Hefazat is trying to compile a list of its missing members, but is finding it hard to do because of government harassment:

We are under pressure from the ruling party and the administration. They tell us that if we raise our voices we will get into trouble. Maybe we will be killed or the police will arrest us.[45]

The government has described claims of a massacre as “grossly fabricated.”[46] According to Foreign Minister Dipu Moni, the security forces used water cannon, sound grenades, tear gas, and rubber bullets to disperse the crowd, in a well-planned and disciplined operation designed to minimize casualties. She criticized Hefazat for bringing children to the rally and accused opposition activists of exploiting a religious movement to create “complete lawlessness.” She denied that anyone was killed during the actual operation to clear the protesters from Shapla Chattar, but said that the police recovered 11 bodies after the clashes that took place during the daytime of May 5.[47]

The main operation lasted for around 20 minutes, while the mopping up took up another one and a half hour. Since no lethal or less lethal weapons were used during the operation, there was hardly any scope for casualty in the hands of the law enforcing agencies.... When the police asked them to leave the place, they followed suit with their hands up in the air. Some of the injured people were taken to different hospitals.[48]

While the claims of the BNP lack credibility and those of Hefazat appear overstated, the government’s account also appears inaccurate. The evidence obtained by Human Rights Watch suggests that serious human rights abuses were committed by the security forces and that some people were killed during the early hours of May 6. In total, based on hospital logs, eyewitness accounts, and well-sourced media reports, Human Rights Watch believes that at least 58 people died on May 5 and 6, seven of whom were members of the security forces. The death toll may be higher.

Hefazat recruited large numbers of boys from madrassas to participate in the rally. It is unclear how many were aware of the risks of marching into Dhaka. A 12-year-old madrassa student described his experience as follows:

After the rally I fell asleep near the footbridge by Notre Dame College. There were explosions which woke me up. I saw I was all alone, apart from maybe about 5 or 7 bodies lying in front of me. Then I saw five men in plainclothes. Some had blood on them. They grabbed me and started insulting me, saying they had caught a Hefazat. One man had a helmet on and he said he wanted to slaughter me.

Two of the men grabbed my right arm, two grabbed my left arm, and the fifth man aimed his gun at me. I started weeping and couldn't say anything. They told me not to move but just as he fired I dropped my head. He was aiming at my chest but six small rubber pellets hit my face. The man who fired it was standing about two meters away from me. I then pretended to be dead and they dumped me with some other bodies. Then I saw some RAB coming. I called for help and one gave me some water and told me to go away.[49]

Sequence of Events

On May 5, 2013, some 200,000 madrassa teachers and students, including many boys under the age of 18, converged on Dhaka from different parts of the country, to support Hefazat's demands. Violence broke out from about noon onwards at various locations in the city center. The government blamed it on demonstrators who committed “widespread vandalism, arson and destruction of public and private properties.”[50] Footage filmed by the Associated Press shows police officers opening fire with shotguns and spraying tear gas while trying to prevent a huge crowd of stick-wielding young men from moving away from the center.[51] But the AP only had cameras in one location, and it is not clear what sparked the violence, which soon degenerated into a full-scale clash with protesters hurling rocks at the police and setting up barricades in front of Dhaka's main mosque, the Baitul Mokaram.

Journalists covering the riot said they saw protesters set fire to wooden book stalls, a bus, and two office buildings, including the headquarters of the Bangladesh Communist Party. Some of this damage was still visible a month later. Many of the protesters were not wearing the typical long, white shirt of a madrassa student or teacher, prompting observers to think that they were supporters of the BNP and Jamaat.[52] Awami League activists also fought with Hefezat supporters. Press reports claim there were 15 explosions outside Awami League offices that day.[53] Banglavision TV filmed two Awami League supporters armed with pistols.[54]

A 19-year-old Hefazat volunteer told us:

I was helping others get to Shapla Chattar. While we were marching through the Golap Shah Mazar area, some Chhatra League (Awami League activists) stopped us and we saw many police arriving also. Some police started firing at us from rooftops. Many of those around me were wounded and we panicked. We tried to escape, but the police chased after us. Five of us fell down and were wounded. I was shot in the hand. I was afraid the Chhatra League would kill me as they were carrying sharp blades. Finally I managed to get to Mitford Hospital, but the police were there too and taking some injured people away. The doctors became scared. They gave me some painkillers and told me to go away. Later on I went to the Dhaka Medical College Hospital for treatment. They found nearly 40 pellets in my hand but after surgery could only remove seven. Now I cannot move my fingers or straighten my hand.[55]

A 25-year-old Hefazat-e-Islam volunteer also described being shot:

We took shelter in the Baitul Mokarram mosque. The police called us to come out. When we did, they fired at us. Bullets hit my face and when I fell down they came and shot me in my knee and abdomen and shoulder. They shot from barely 3 meters way. All were rubber bullets with lead balls. I was not armed, I did not a have a stick. I was hit 19 times. I said to them, “Why are you shooting at me? I'm a volunteer.” Now I cannot see anything from my right eye, and after an operation I can see only a little bit from my left eye.[56]

Some of the victims were bystanders, like Raqibal Huq. He was a shopkeeper who had gone to Motijheel to buy homeopathic medicines. He died of a gunshot wound to the head.[57] Others were madrassa students, like Saidul Islam, a 20-year-old, who was killed by a sharp blow to the head.[58] A relative of Sadam Hussein, a 22-year-old student, said his corpse had gunshot wounds and large cuts on the back.[59]

Hundreds of protesters were treated for wounds in hospitals. Many corpses were also brought in. Staff in four hospitals told Human Rights Watch that wounds were caused by small metal pellets or buckshot, small rubber bullets, actual bullets, and by large cuts and bruises. Some protesters had broken limbs, and at least four were fully or partially blinded.[60] Video footage shows police officers beating apparently unarmed men lying on the ground, one of whom looks unconscious or dead and starts to bleed heavily from the head.[61]

In the Al Baraka Hospital, staff said they treated more than 50 patients, most with cuts or injuries caused by rubber bullets or buckshot. They also received two patients with severe bullet injuries. One had been shot through the head, the other through his waist. Staff said the bullet passed through both hip bones.[62]

The Security Force Operation Early on May 6

As night fell, the situation calmed down somewhat. Journalists present said that most of the protesters had gathered peacefully at the Shapla Chattar intersection and were listening to speeches from their leaders or praying. From the edges of the crowd, some protesters threw petrol bombs at the police. The bodies of four men killed earlier in the day were brought to the square and placed on a wooden platform near the stage. Most protesters left the area by midnight, leaving only about 50,000, many of them asleep.[63]

At around 2:30 a.m. on May 6, police reinforcements arrived, along with several hundred members of RAB and the BGB. The BGB stayed behind the other units and was not involved in the ensuing operation according to witnesses. According to a Daily Star journalist at the scene, the commanding officer of the police, Additional Police Commissioner Maruf, addressed his men and told them to exercise restraint. “Don’t shoot much. If necessary we will only use our shotguns. We will only shoot if they threaten us,” the journalist noted him as saying.[64] At 2:30 a.m. the police warned the protesters to leave the area, though it was so noisy few heard the warning.[65]

Police and RAB moved towards Shapla Chattar from two directions, leaving a third main road open as an escape route for the protesters. They fired tear gas, sound grenades and rubber bullets at the crowd, and a riot truck sprayed them with warm water. The attack was deafening, and the majority of Hefazat supporters ran away in panic. Hundreds of others, however, hid in nearby buildings and alleyways, where they were later rounded up. Many came out with their hands up and were allowed to leave, but others were fired at or beaten. One journalist described the scene:

I was tipped off by the police about the operation. I arrived at about 1:15 a.m. There were lots of vehicles belonging to the BGB, RAB, and police. Before the operation started a man held up a hand microphone and told the protestors to leave the place. The Hefazat shouted back slogans and some threw stones. The police waited for a while then started firing some shots in the air. Then they fired tear gas. It was very chaotic, the firing was very loud. They used sound grenades and rubber bullets fired from shotguns. When we moved in Shapla Chattar I saw four dead bodies wrapped in white cloth and polythene. They were lying on a rickshaw van by the stage. I think maybe they had been killed during the day. Then I saw one person lying down. He was bleeding from the left side of his head. I think he had been hit by a tear gas canister. I heard people say he was alive and he was taken to hospital.[66]

Human Rights Watch has not come across any evidence to suggest the security forces used automatic weapons during this operation. However video footage from journalists and eyewitness statements suggest that security forces used indiscriminate and unnecessary force. Many witnesses spoke of seeing corpses. Video footage shows police and RAB officers beating severely injured protesters. One journalist remembers checking the pulses of several men lying on the ground:

When the police started firing we moved to one side of the street and sheltered in a building. We didn't hear a warning, just lots of firing. At 3 a.m. I went into Sonali Bank and saw 15-20 bodies. I checked the breathing of some of them and shook them to see if they were alive or dead. Some were dead, at least 10. I then walked towards the cinema hall and the Alico office.[67] Some fighting was still going on there. A policeman had been killed, and the police had become more aggressive towards the protestors sheltering there. I saw 2 or 3 more bodies.[68]

Another reporter saw RAB soldiers dragging four people and loading them on to a truck:

I was behind the police lines at Dainik Bangla. I did not hear any police announcement or warning that they were going to start the operation. They just started firing rubber bullets and blanks and sound grenades. Later I saw 20-25 RAB taking four bodies from a side road opposite City Centre, near the Biman Bangladesh office. When I went to see what was happening, I told them I was a journalist and showed my ID and one hit me with a stick in face. The bodies were of four madrassa students. I saw the blood but can't tell what sort injuries they had because it was dark. On the steps of the Sonali Bank I saw the body of a young guy. He was maybe 10 or 12. His whole body was bruised from neck to chest. I checked his pulse and heart beat and a policeman also checked his pulse and said he was dead. The police picked up the body and put it into an ambulance.[69]

A 23-year-old madrassa student said that security forces were deliberately targeting protesters.

At around 2:30 a.m. I realized that there was an attack. It was completely dark because they had turned off the lights so I could not actually see which way they coming from. The police said something but it was so loud I could not understand what they were saying. They were raining bullets, tear gas, and hot water down on us. It was a terrifying situation. I was with my brother and we tried to escape over a wall. They started beating us with sticks as we climbed over it. I jumped and broke my foot when I landed on the other side. As I tried to run away I was shot. Later the x-ray showed that there were 102 pellets in my leg. I was not armed. I only had my prayer carpet and prayer beads. It was not aimless shooting, they were targeting us, they were aiming at us. The police were 10 to 15 feet behind me. It was not accidental fire.[70]

An 18-year-old madrassa student said that he was fired at with birdshot and beaten after he surrendered.

I lost contact with my friends after the police operation began. I took shelter with some other guys inside a building. Someone's mobile phone went off and the police knew we were hiding there. They started shouting and swearing at us and threw two sound grenades at us and told us to come out or we would be killed. We were so scared that we would be killed. So we came out with our hands up. The moment I stepped out I was struck by rubber bullets on the leg. I started bleeding and I ran away, but I fell down and they beat me with their sticks. I didn't see any dead bodies but I saw many people who were seriously injured, calling for help, saying “please save my life.”[71]

The May 6 Clashes

Thousands of protesters fled Shapla Chattar in the direction of Jatrabari, on the outskirts of Dhaka, and at the start of the main highway to Chittagong and southeast Bangladesh. Clashes broke out 13 kilometers down this road as students from a madrassa blocked vehicles and threw stones at the police from the roof of the madrassa.[72]

According to a local cameraman who filmed the incident, the students were joined by Hefazat protesters who had fled Dhaka as well as local BNP and Jamaat supporters. He also saw a group of Awami League activists carrying sticks and knives joining in the fray on the side of the police. The cameraman said that the police began by firing tear gas shells at the stone-throwing protesters, but when the protesters ran out of the madrassa, the police used shotguns and automatic weapons.[73] Initially positioned from the side of the protesters, the cameraman saw protesters kill a policeman:

One policeman fell down and they beat him death. I saw this, I was only 20 yards away. I felt scared so crossed over to the police side. When they saw that that man had been killed they started shooting indiscriminately. Some RAB joined them after one hour, but the Hefazat attacked them as well and set fire to two of their vehicles.[74]

The cameraman’s footage of the incident shows many police and RAB personnel firing shotguns at the madrassa building, where students on the roof are throwing back stones.[75] At least 17 protesters were killed in the confrontation. Two police and two BGB men were also killed.[76]

III. Government Response

Following the protests, security forces launched sweeps of neighborhoods thought to harbor individuals believed responsible for violence, but also targeting hundreds of others, including Jamaat supporters and the families of victims, regardless of whether there was evidence they participated in the protests, let alone whether they were responsible for violence. While authorities arrested many protesters and supporters, there have been no signs of meaningful efforts to hold security forces accountable for abuses including unjustified or improper use of live bullets, arbitrary arrests, and extrajudicial executions.

Police Sweeps and Arrests, Intimidation of Victims and Witnesses

Human Rights Watch spoke to 13 people who witnessed large-scale security force security operations and neighborhood sweeps in the immediate aftermath of the ICT-related protests. Many of the operations took place in areas where security forces had recently shot and killed one or more protesters.

Human Rights Watch documented cases in Noakhali, Dhaka, and Manikganj in which police issued FIRs which gave the police authority to arrest hundreds, sometimes thousands, of “unknown assailants.”[77] While police did not actually arrest thousands of people, in some sweeps they arrested dozens. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that immediately following large clashes, police officers would round up local residents who they claimed were a named assailant or one of the “unidentified assailants.” The fact that police had seemingly open-ended authorization to conduct arrests without evidence tying specific individuals to specific crimes generated widespread fear in the affected communities.

A human rights defender working for Odhikar who arrived in Chittagong two days after a protest in which three Awami League supporters were killed described how police had conducted sweeps looking for thousands of unknown assailants, arresting dozens and driving many men out of the villages and into hiding.

I went to the scene two days after the clash. I went to three villages and there were no men in any of the villages because they were hiding. Five cases were filed for the arrest of thousands of unknown assailants. The police had introduced one of the cases, and listed 139 named individuals and 3,000-4,000 unknown assailants. We have a copy of the FIR…. According to police at Bojpur police station they have arrested 32 people named in the FIR and 15 others.[78]

Witnesses described how individuals who were identified as Jamaat supporters were specifically targeted during police sweeps. The mother of one victim told Human Rights Watch:

My son went to say his prayers and he and three other Shibir boys were having snacks when 10-15 plainclothes police came and started chasing them. One of them was caught and they police started beating him, his lungi came off and he said “at least let me keep my lungi on,” but they wouldn’t and they kept beating him. It happened in front of our shop.[79]

Many interviewees asserted that police used broadly framed FIRs to intimidate family members and witnesses so that they would not file cases against members of the security forces.[80] For example, two family members of a 12-year-old boy shot in the torso and killed by police officers on February 28 were charged with the murder of the child (five other victims were also killed in the same incident). Several family members were eyewitnesses to the killing and have fled into hiding. The grandfather of the victim described the events:

We didn’t go to the police, but the next day I found that they filed a case against me. On April 16, 30-35 police came to pick me up. Fifty people in the village have cases filed against them [by police and others], accusing them of being responsible for deaths. Members of each of the victims’ families, usually brothers and fathers, have been charged as well as others…. My brother has been charged…. We are not political, my grandson was not political….They have been going house searching for me, I have had to move a different place each night.[81]

Human Rights Watch documented similar patterns in other locations. The brother-in-law of a 25-year-old business owner shot and killed by police near his place of work in Manikganj was himself charged with the killing of his brother-in-law. Several witnesses told us that the 25-year-old had been shot in the head by police responding to clashes between madrassa students and Awami League supporters. As the brother-in-law told Human Rights Watch:

The police filed a case against us. Four people died that day, many others were injured. I’ve been charged with murder. They have a case against the chairman and a member of the local government; they have all been named in the case. We have all been warned. We want to file a case but they [the police] wouldn’t let me. Six cases were filed by the police, one of them an “unknown assailants” case against 4000 unknown people. In two of the other cases people were specifically named: 113 were named including me in one of them; 125 people were named in another case.[82]

Lack of Investigations and Refusal to Register Complaints from Victims’ Families

A number of family members also told Human Rights Watch that they had been unable to report the killings of family members shot by security forces. In some instances, family members said, police refused to take their complaints. In other instances, the sweeping arrests made by police left family members afraid to approach police.

In Bogra, the son of one victim described how family members of two other women shot by police in the same incident were denied the opportunity to file a case, and contrasted the police refusal to take action on the murders with aggressive police pursuit of locals in connection with other protest-related violence. As he described it:

Family members of those who died did go to the police station but they wouldn’t let them file a case. But the police did file cases against some of the other locals. The charges were that there were attempts to attack the police station by villagers. Some of them have been arrested but some of them are in hiding. Most of them are regular people but some of them are Jamaat followers.[83]

In Bogra, family members were not able to enter the police station. In other locations police were explicit in telling families they were not allowed to file a complaint. The father of a 17-year-old boy shot by a police officer in Cox’s Bazar explained:

I tried to report it to the local police station, but they did not take the complaint. I went there and I said that my son was shot by police, I said, “You shot my son,” and the police said, “We are not going to accept your complaint.”

How I will get justice for my son?[84]

To date Human Rights Watch and families of victims have received no information regarding ongoing or completed investigations into any of the deaths resulting from security force use of live ammunition during or in the immediate aftermath of protests.

Crackdown on Bloggers and Media

Bloggers

Prior to the ICT-related protests, the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission on February 16, 2013, shut down the Sonar Bangla blog, known to be operated by Jamaat activists, for spreading “hate speech and causing communal tension.”[85] This came after a day after pro-Shahbagh blogger Ahmed Rajib Haider was killed by unknown assailants suspected to be pro-Jamaat.[86] The blog was still shut at time of writing.

On February 16, Aminul Mohaimen, the editor of the Sonar Bangla blog, was arrested. The Sonar Bangla blog, widely regarded as a venue through which pro-Jamaat sentiments were expressed, is still unavailable at this writing.

On April 2-3, the police arrested four bloggers, Subrata Adhikari Shuvo, Mashiur Rahman Biplob, Rasel Parvez, and Asif Mohiuddin, who had posted articles critical of the government. The four bloggers had publicly criticized the government through their blogs for being "biased toward Islamist views and ideologies in a country that is constitutionally supposed to be secular," according to news reports.[87] Shuvo, a member of the minority Hindu community, had been openly critical of what he believed was the mainstream media’s failure to report objectively on attacks against religious minorities in Bangladesh.

Police described the four as “known atheists,” and said the four would face charges of “instigating negative elements against Islam to create anarchy.”[88] Molla Nazrul Islam, deputy commissioner of the Dhaka police, told the local press that the bloggers had "hurt the religious feelings of the people by writing against different religions and their prophets and founders including the Prophet Muhammad."[89]

All four were charged under Section 57(2) of the Information Communication Technology Act, 2006, and later granted bail. Further charges are being considered by the courts.[90] Blogger Asif Mohiuddin alleges that a previous physical assault on him was by Islamic extremists. In his final post before his arrest on March 8, 2013, Mohiuddin wrote:

I was attacked but I was lucky, I did not have to die. But blogger Rajib Hayder was not so lucky…. Rajib was attacked later that month. His throat was slashed; the attackers left him only after ensuring his death. Those senseless attackers of Rajib had no quarrel with him; they did not even know him. Still they decided to attack and kill him because they figured his writing is somehow challenging and threatening the all-powerful position of Allah and the only true religion called Islam! They figured this challenge should be countered with knives and machetes for the holy purpose of the protection of almighty Allah and the holiest religion Islam.

Although they believe Allah to be all powerful, omnipresent and omnipotent, they still figured he needs some protection from the literary assault of an innocent writer who writes against what he considers to be bigoted, wrong, poisonous…. However, if my reaction upon hearing these horrible sets of news becomes “mad, barbaric, ignorant,” fingers would be pointed at me; my reaction will be considered more offensive than the actual act of the slashers of Rajib’s throat and how can I not feel enraged, how can [I] not feel helpless; how can any sensible person not [feel these things]?

I do not know whether I am going to be attacked again. So far all the alleged hit-lists published by Islamists contain my name; it is very possible that I am going to be attacked again. Humayun Azad once said: “Speak, for the cup of hemlock is not yet on your [lips].” Therefore, I will keep speaking, I will be writing as long as I am alive, as long as the cup of hemlock is not pushed to my lips.[91]

Bangladesh’s home minister later said that the four bloggers were on a list of 84 bloggers identified by Islamist groups as atheists and suggested that they might face criminal prosecution for hurting “religious sentiments,” which is proscribed by Article 295(A) of the Bangladeshi Penal Code.

Media

Two television stations that support opposition political parties, Islamic TV and Diganta TV, were arbitrarily taken off the air by the government on the night of May 5-6 and remain off the air at the time of writing. The stations had been reporting live from the site of the protests and were shut off in a blatant attempt to cut off opposition coverage of the events.[92]

On April 11, 2013, the police arrested Mahmdur Rahman, the editor of an opposition news outlet, Amar Desh. Rahman was subsequently charged with sedition and unlawful publication of a hacked conversation between the ICT judges and an external consultant. The conversations exposed political interference with the trials. The conversations were originally published by The Economist and later republished in Bangladesh by Amar Desh and other news organizations and websites.[93] Shahbagh protesters had earlier demanded Rahman’s arrest for critical reports about their movement.[94] The state minister for home affairs, speaking at a press conference, said that Rahman has “hurt Muslim religious sentiments.”[95] Rahman had previously been arrested in 2010 on defamation charges but was later released and the charges were dropped. Rahman has alleged torture and ill-treatment while in custody both in 2010 and after his recent arrest.[96]

On April 14, the offices of another opposition newspaper, Daily Sangram, were raided by the police. The editor, Mohamed Abul Asad, has subsequently been criminally charged for printing and publishing copies of Amar Desh after authorities had shut down Amar Desh following Rahman’s arrest.[97] More than a dozen others, including Rahman’s mother, acting chairman of Amar Desh, have also been charged in the same case.[98]

Masumur Rahman Khalili, the editor of a pro-Jamaat newspaper, the Daily Naya Diganta, described to Human Rights Watch researchers the burning and destruction of his paper’s offices on February 12:

Twenty young boys were in front of the office, we were about to deliver press materials. They used that paper to set fire to the press…. There were police behind the group, approximately 20 police standing 20 meters behind them…. The next day I reported the incident to the police and they asked why I was filing a case. I went back the next day and they let us file. A few days later they came to investigate but said they didn’t know who did it. There have been no arrests, no investigations and no follow up report.[99]

At the time of the attack, police arrested several employees who worked at the printing press and were preforming their usual duties. Their arrest was not in conjunction with the attack on the printing press. According to Khalili, one of his employees, Musharaff Hussain, 35, is being held without bail and without access to a lawyer in Dhaka Central Jail on unknown charges.[100]

IV. Recommendations

To the Government of Bangladesh

- Immediately establish an impartial, transparent, and independent commission to investigate the large numbers of deaths and injuries that occurred in connection with protests between February and early May 2013. The commission should ensure that all perpetrators of serious human rights abuses are brought to justice regardless of their rank or political affiliation, and should make its findings public.

- Immediately make public the number of persons detained in protest-related security operations and ensure that all detained persons have access to legal representation and are treated in accordance with international due process standards. This includes ensuring all detainees are brought promptly before a judge and being promptly charged after the initial detention. For those properly charged and facing trial, pre-trial detention should be the exception, not the rule.

- Ensure that all persons detained by the police and other security forces are held at recognized places of detention and are not subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. Immediately inform family members and legal counsel of detainees’ whereabouts, and allow detainees regular contact with family members and unhindered access to legal counsel of their choosing.

- Ensure that all detainees are promptly brought before a judge and charged or released.

- Where there is evidence a person has been disappeared by security forces or others acting at their behest, instruct relevant agencies to conduct rigorous, thorough investigations and immediately make known all available information on the whereabouts or fate of the detainee.

- Immediately stop using First Information Reports (FIRs) as a legal veneer for arresting or criminally charging scores of “unknown assailants” without evidence of specific criminal wrongdoing by those specific individuals.

- Provide prompt, fair, and adequate compensation to victims’ families for deaths or injuries caused by security forces. Provide assistance to families who suffered injury or property loss due to the demonstrations and government crackdown.

- Provide training to security forces, including in overseeing demonstrations, crowd control, and response to violent protests, as part of efforts to bring their performance into linen with international standards.

- Publicly order the security forces to follow the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, which state that security forces shall “apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force and firearms,” and that “whenever the lawful use of force and firearms is unavoidable, law enforcement officials shall: (a) Exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offence and the legitimate objective to be achieved; (b) Minimize damage and injury, and respect and preserve human life.”

- Immediately end all media restrictions that violate the right to freedom of expression, including restrictions on perceived pro-opposition media outlets. Review and drop politically motivated charges against bloggers and members of the media.

- Sign and ratify the international Convention against Enforced Disappearance and the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture, and adopt all necessary legislation and other measures to comply with their terms.

- Immediately invite the following UN special

rapporteurs and working groups to investigate and report on the situation in

Bangladesh, and take all necessary measures to implement their recommendations

in a timely matter:

- special rapporteur on torture;

- special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions;

- Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances

- Fully investigate attacks on religious minorities, and engage in dialogue with minority community leaders and security forces to ensure better protection of such communities, and more rigorous investigation of and response to targeted attacks.

To Political Leaders

- Publicly urge supporters to refrain from violence or incitement of violence during hartals and political protests. Avoid all language that directly incites violence.

- Opposition parties including the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Jammat-e-Islam Party, as well as independent organizations such as Hefazat-e-Islam, should condemn and take steps to deter their supporters from carrying out unlawful acts, including physical attacks on law enforcement officers and members of the public with different political views.

- Protect children taking part in protests from dangerous and harmful situations by ensuring that they are not put in the frontline of potentially violent protests.

To the United States, United Kingdom, European Union, and Other International Donors

- Condition future assistance and training to Bangladeshi security forces on progress in meeting accountability benchmarks, including full cooperation with police and human rights investigators, discharge of officers implicated in serious human rights abuse, and open the establishment and used of a transparent complaints procedures.

- Press the Bangladeshi government to investigate and prosecute police, BGB, and RAB officials and officers responsible for human rights abuses during the recent protests.

- Provide technical support to any body set up by Bangladesh to investigate the deaths and injuries of protesters between February and early May 2013, to ensure a credible and transparent process.

- Review all support to rule of law and justice programs to ensure that courts are able to operate fairly and according to international legal standards.

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Tirana Hassan, senior researcher in the Emergencies Division at Human Rights Watch and Kyle Hunter, associate in the Emergencies Division. Tej Thapa, senior researcher for the Asia Division, and Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia director assisted in the drafting and editing.

The report was edited by Brad Adams, director of the Asia Division; Joseph Saunders, deputy program director; and Clive Baldwin, senior legal advisor. Grace Choi, publications director; Kathy Mills, publications specialist; and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, provided production assistance.

Human Rights Watch is deeply grateful to the many individuals who shared their experiences with us; without their testimony this report would not be possible. We are also grateful for the invaluable knowledge and generosity of human rights activists in Bangladesh, particularly the staff at Odhikar and Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK).

Appendix I

[1] “Bangladesh cleric Abul Kalam Azad sentenced to die for war crimes,” BBC News, January 21, 2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-21118998 (accessed May 28, 2013).

[2] “Bangladesh: Abdul Kader Mullah gets life sentence for war crimes,” BBC News, February 5, 2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-21332622 (accessed May 28, 2013).

[3] In the wake of these protests, the government amended the ICT rules to allow the prosecution to appeal the sentence and seek the death penalty, and made the change retroactive. As we have previously noted, this action violates the prohibition on double jeopardy set forth in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (article 14(7) of the convention provides that persons should not be tried or punished again for an offence for which they have already received a final judgment in accordance with the law). The amendment also allows the prosecution to file war crimes charges against the Jamaat party as a whole, paving the way for an outright ban on the Jamaat-e-Islam party if convicted. Following the Shahbagh protests, Awami League leaders, including the home minister, suggested that Jamaat should be banned and media outlets connected to the party closed. See, “Post-Trial Amendments Taint War Crimes Process,” Human Rights Watch news release, February 14, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/02/14/bangladesh-post-trial-amendments-taint-war-crimes-process.

[4] “Bangladesh: End Violence Over War Crimes Trials,” Human Rights Watch news release, March 1, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/03/01/bangladesh-end-violence-over-war-crimes-trials.

[5] Witnesses described protesters throwing stones at police officers in Rajganj; Human Rights Watch interview with human rights researcher, Dhaka, April 29, 2013.

[6] In one instance in Chittagong, at least 130 motorcycles and minibuses were burned by protesters. Interview with human rights researcher, Dhaka, April 28, 2013. Also photographs/video from newswires show burning of vehicles.

[7] Odhikar, “Human Rights Monitoring Report: January 1- June 30, 2013,” July 1 2013, http://www.odhikar.org/documents/2013/HRR_2013/human-rights-monitoring-Six%20Monthly-report-2013-eng.pdf (accessed July 20, 2013).

[8] “Cops Attacked in Jessore, 1 Killed”, BDnews24.com, March 22, 2013 http://bdnews24.com/bangladesh/2013/03/22/cops-attacked-in-jessore-1-killed (accessed 24 July 2013).

[9] ”Violence Grips Bangladesh After War Crimes Verdict, 23 Killed”, Tehelka Daily, February 28, 2013, http://www.tehelka.com/violence-grips-bangladesh-after-war-crimes-verdict-23-killed/ (accessed July 8, 2013).