Map of Syria

Summary

After the demolition in Wadi al-Jouz, the army came to our neighborhood with loudspeakers. They said that they would destroy our neighborhood like they destroyed Wadi al-Jouz and Masha` al-Arb`een should a single bullet be fired from here.

¾A woman who observed the destruction of the Wadi al-Jouz neighborhood from an adjacent neighborhood.

Since July 2012, Syrian authorities have deliberately demolished thousands of residential buildings, in some cases entire neighborhoods, using explosives and bulldozers, in Damascus and Hama, two of Syria’s largest cities. Government officials and pro-government media outlets have claimed that the demolitions were part of urban planning efforts or removal of illegally constructed buildings. However, the demolitions were supervised by military forces and often followed fighting in the areas between government and opposition forces. These circumstances, as well as witness statements and more candid statements by government officials reported in the media indicate that the demolitions were related to the armed conflict and in violation of international humanitarian law, or the laws of war.

Human Rights Watch concluded that seven cases of large-scale demolitions documented in this report violated the laws of war either because they served no necessary military purpose and appeared intended to punish the civilian population, or because they caused disproportionate harm to civilians. Those responsible for the wanton destruction of civilian property or for imposing collective punishment have committed war crimes and should be investigated and held to account.

The first incident of large-scale demolitions documented by Human Rights Watch took place in July 2012. Satellite imagery analyzed by Human Rights Watch shows that since then, the Syrian authorities have demolished a total of at least 145 hectares—an area equivalent to about 200 soccer fields—of mostly residential buildings in seven neighborhoods in Hama and Damascus. Many of the demolished buildings were apartment blocks several stories high, some as many as eight. Thousands of families have lost their homes as a result of these demolitions.

All of the documented demolitions took place in areas widely considered by the authorities and by witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch to be opposition strongholds. As far as Human Rights Watch knows, there have been no similar demolitions in areas that generally support the government, although many houses in those areas were also allegedly built without the necessary permits.

Some of the demolitions took place after heavy fighting between government and opposition forces. In Damascus, for example, government authorities demolished residential buildings in the Tadamoun and Qaboun neighborhoods immediately after government forces pushed back an opposition military offensive in the capital in mid-July 2012. Two neighborhoods in Hama that government forces destroyed in September-October 2012 and April-May 2013, had allegedly been used by opposition fighters to move in and out of the city.

Some of the demolitions took place around government military or strategic objectives that opposition forces had attacked, such as the Mezzeh military airport, the Damascus international airport, and the Tishreen military hospital in the Barzeh neighborhood. While the authorities might have been justified in taking measures to protect these military or strategic objectives, the destruction of hundreds of residential buildings, in some cases kilometers from these objectives, appears to have been disproportionate and in violation of international law.

Some government and military officials have been more forthcoming about the real reason for the demolitions. The governor of the Damascus countryside, Hussein Makhlouf, explicitly stated in a media interview in October 2012 that the demolitions were essential to drive out opposition fighters. After the demolition of the Wadi al-Jouz neighborhood in Hama city in May 2013, the military warned residents in other neighborhoods that their houses would also be demolished if opposition fighters attacked government forces from these neighborhoods, according to a witness in an adjacent neighborhood.

Local residents told Human Rights Watch that government forces gave little or no warning of the demolitions, making it impossible for them to remove most of their belongings. Owners interviewed by Human Rights Watch also said that they had received no compensation. Several house owners claimed that contrary to the government’s stated pretext for the demolitions, they had all the necessary permits and documents for their houses, but their homes were nevertheless destroyed. Human Rights Watch has not been able to verify this claim. Human Rights Watch has not documented that anybody was injured or killed in the process of these demolitions.

Under the laws of war, parties to a conflict may only attack military objectives. The intentional or wanton destruction of civilian property is unlawful unless the property is being used for a military purpose, such as for the deployment of opposing forces. However, civilian property may be destroyed if future use by opposing forces, for example to stage an attack, is expected and imminent and only so long as the expected harm caused to civilians and civilian property is proportionate to the anticipated military advantage. Destroying property merely to punish the population is always prohibited.

In areas that have not been under the control of or face no immediate threat by opposition armed groups, a warring party might lawfully seek to demolish civilian property for longer term security reasons. This would concern, for instance, civilian structures very close to military bases or airports. The laws of war place an obligation on parties to a conflict, to the extent feasible, to remove civilians and civilian objects from the vicinity of military objectives. In accordance with international human rights law, such demolitions would need to be carried out with adequate notice, consultation, and compensation to those affected.

This report is based on detailed analysis of 15 commercial satellite images and interviews with 16 witnesses to the demolitions and owners whose houses were demolished. In addition, Human Rights Watch reviewed media reports, government decrees, and videos of the destruction and its aftermath posted on YouTube.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Syrian government to immediately end demolitions that are in violation of international law and provide compensation and alternative housing to the victims. Human Rights Watch calls on the United Nations Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court.

Recommendations

To the Syrian Government

- Immediately halt demolitions of houses in violation of laws-of-war prohibitions against deliberate or disproportionate attacks on civilian objects, wanton destruction of property, and collective punishment. Urban planning decrees should not be selectively implemented to circumvent laws of war and international human rights law protections;

- Ensure access to humanitarian assistance, including housing, to all civilians who have lost homes because of demolitions, whether or not lawful;

- Provide adequate compensation or alternative housing to residents whose homes have been unlawfully demolished;

- End demolitions of homes for security reasons in areas not threatened by opposition forces without advance notice, consultation, and adequate compensation in accordance with international human rights law;

- Maintain accurate statistics on property damaged and make that information publicly accessible in a timely fashion;

- Provide immediate and unhindered access and cooperation to independent observers, journalists, and human rights monitors, including the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the UN Human Rights Council Commission of Inquiry on Syria.

To the UN Security Council

- Refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court (ICC);

- Adopt targeted sanctions on Syrian officials credibly shown to be implicated in human rights violations;

- Require states to suspend all military sales and assistance, including technical training and services, to the Syrian government until Syria ends unlawful attacks against civilians, given the real risk that the weapons and technology will be used in the commission of serious human rights violations;

- Demand that Syria cooperate fully with the UN Human Rights Council Commission of Inquiry on Syria.

To All Countries

Given the failure of the Security Council to take measures intended to press the Syrian government to end the unlawful killing of civilians and destruction of civilian property, concerned governments should act, individually and collectively, to:

- Publicly condemn unlawful demolitions that violate international humanitarian law;

- Implement embargoes on the sale and supply of arms, ammunition and materiel to the Syrian government;

- Increase pressure on Russia and China to stop hampering effective UN Security Council action on Syria.

Methodology

This report is based on detailed analysis of 15 very-high resolution commercial satellite images recorded between July 16, 2012 and November 20, 2013.[1] Satellite imagery covering the entire urban extent of Damascus and Hama was used to locate demolition sites, evaluate eyewitness testimonies, as well as to measure the area, pace, and timing of the demolitions. Further, the imagery was used to identify the probable methods of demolition employed by government forces and evaluate the local security context immediately preceding, during, and following the demolitions by identifying the number of heavy military vehicles in the immediate area.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 16 people who either witnessed demolitions or owned houses that were demolished. Identification and interviewing of witnesses have been challenging because fighting and subsequent demolitions permanently displaced many of the witnesses. Interviews were conducted by phone and in person in Syria’s neighboring countries. Most interviews were conducted in Arabic by Arabic speaking researchers. Some interviews were conducted through Arabic-English interpretation. Because of the real possibility of reprisals we have withheld the names of the victims and witnesses we interviewed, using instead pseudonyms to identify the sources of information.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed more than 85 videos posted on YouTube and analyzed government decrees and statements, as well as media reports. To verify the time, location, and circumstances of the videos, Human Rights Watch contacted and interviewed the people who filmed the videos whenever possible. In several cases, Human Rights Watch extracted individual frames from the videos, sometimes creating photo mosaics from the frames, and compared visible landmarks in the videos with satellite imagery to confirm the location.

Area measurements in the report refer to the building surface destroyed, not the total area of the neighborhoods that were demolished. The total area of destroyed buildings was calculated from measurements of the affected areas directly from the satellite imagery.

The instances of demolitions included in this report are those for which Human Rights Watch obtained both statements from witnesses or owners, and a time-series of satellite imagery of high enough quality to allow for detailed analysis.

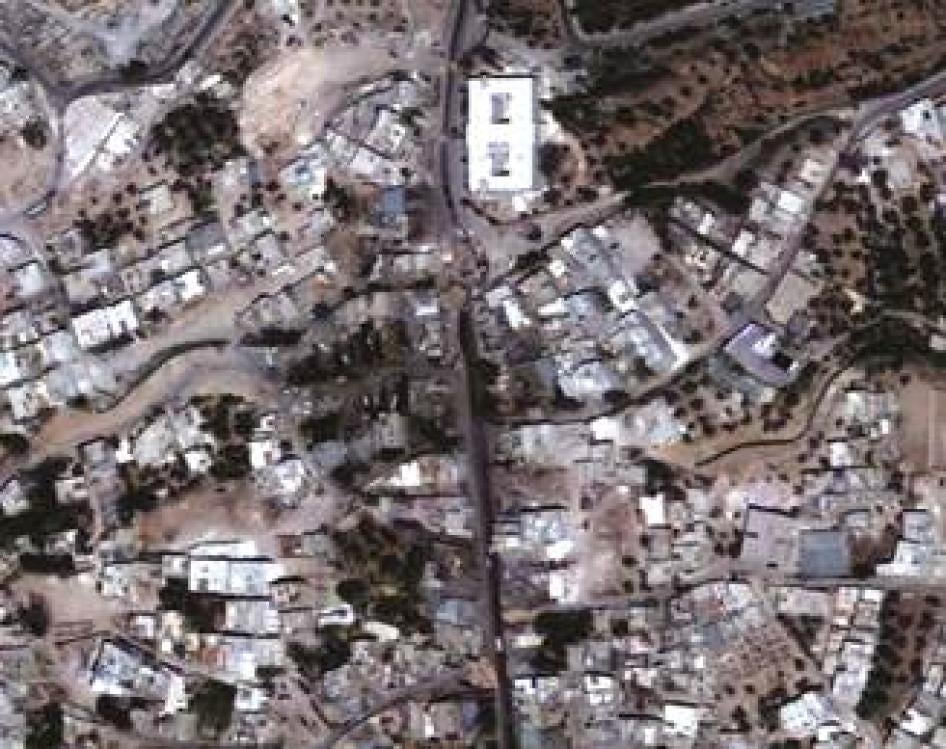

I. Demolition of Masha` al-Arb`een neighborhood, Hama

Date of demolition: September 27-October 13, 2012

Estimated area of destruction: 40 hectares

According to satellite imagery reviewed by Human Rights Watch, virtually all buildings in the Masha` al-Arb`een neighborhood on the northern edge of Hama city were completely destroyed between September 27 and October 13, 2012.

Located adjacent to the Hama-Aleppo highway, the Masha` al-Arb`een neighborhood largely consisted of poorly constructed houses that were built illegally before the Syrian conflict broke out, according to local residents. News articles about the demolition of the neighborhood cited government officials, including the governor of Hama, saying that the authorities were removing illegally built structures to develop the area and improve the living conditions of its inhabitants.[2]

But the context and circumstances of the demolition of the neighborhood indicate that it was mainly driven by ongoing military operations against opposition fighters in the area.

Government forces had clashed with opposition fighters in the neighborhood at various times in the months leading up to the demolition, according to six local residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch. One resident said: “Army soldiers used to break in to our homes searching for opposition fighters. If they suspected that opposition fighters were in the house they would kill or arrest the owner.”[3] Two other witnesses also claimed that government forces had committed extrajudicial executions.[4]

Residents told Human Rights Watch that because government forces controlled the main entrances to Hama, opposition fighters often used the narrow roads in the densely populated al-Arb`een neighborhood to move in and out of the city. Residents also said that some people from the neighborhood had joined the FSA, but that they stayed in only a couple of houses in the neighborhood.

In September 2012, shortly after the end of the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan, government forces launched a major offensive against the neighborhood, shelling the area with artillery and mortars before entering, according to those interviewed by Human Rights Watch. After several days of fighting, opposition fighters retreated from the neighborhood, the witnesses said.[5] News articles cited unnamed government sources claiming that government forces had killed several opposition fighters and seized weapons depots in the neighborhood.[6]

Shortly after opposition fighters retreated, bulldozers directed by government military forces started demolishing the neighborhood, destroying thousands of buildings, according to residents. Umm Oday, who had left the neighborhood a month before the demolition out of fear for her safety, told Human Rights Watch that her neighbor called her one day to tell her that her house was about to be demolished. When she went to her house she saw that the Syrian army had blocked the entrance to her street with tanks and other vehicles. She said:

I yelled, screamed and cried for them to let me pass to see what is going on with my house. When they allowed me and other women to pass, the bulldozer was already demolishing houses while their owners stood outside watching. I begged the soldier to let me in to collect my belongings. He let me, but I had only a few minutes. After I left, the bulldozer demolished my house. Nothing was left of it, not even the walls.[7]

A second owner whose house was also demolished told Human Rights Watch:

We saw bulldozers approaching our neighborhood, but we stayed in our house because we never thought that they would destroy all the houses. After two days, our turn came. We left our things. We were afraid to stay one second longer because our house was shaking while bulldozers destroyed the houses close by. When the bulldozers approached our house, my husband went outside to talk with the army soldiers. My husband was begging them to spare our house but they shouted: ‘We want to destroy, we want to destroy.’ They didn’t explain to us what was happening.[8]

A man who witnessed the destruction from his house across the street from the neighborhood told Human Rights Watch:

It was a disaster and a tragedy. There are no houses left in the neighborhood except one house that was used as a mosque. But of course nobody goes there now because everybody has left.[9]

The two owners of the demolished houses interviewed by Human Rights said that they received no official explanation, warning, or compensation.

The first sign of demolition is visible in satellite imagery taken in the morning of September 28, 2012.[10] While the September 28 imagery shows the presence of over seventy heavy construction and utility vehicles in the neighborhood, only four armored vehicles are visible, supporting witnesses’ claims that the fighting was already over and the neighborhood was under government control by the time of the demolition.[11] Satellite imagery from October 13 showed that by that date virtually all buildings in the neighborhood, a building surface area of over 40 hectares, had been demolished.[12]

II. Demolition of Wadi al-Jouz neighborhood, Hama

Dates of demolition: April 30-May 15, 2013

Estimated area demolished: 10 hectares

Between April 30 and May 15, 2013, government forces demolished the entire Wadi al-Jouz neighborhood (a total building surface area of 10 hectares), located on the northwestern edge of Hama city, according to satellite imagery and two witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch.

As in the case of the Masha` al-Arb`een neighborhood, pro-government media claimed the authorities were removing “urban irregularities” that had made the neighborhood ugly and impeded traffic.[13] Other news articles, however, described the operations in the neighborhood as restoring peace and security, killing terrorists, and seizing weapons and ammunition.[14]

Human Rights Watch interviewed two local residents who witnessed the demolition of the neighborhood. They told Human Rights Watch that, just as with the al-Arb`een neighborhood, opposition fighters had used the Wadi al-Jouz neighborhood to enter and leave Hama city because of its location on the edge of the city. At the end of April, government forces shelled the neighborhood for two days, causing many of the local residents to flee, according to the two witnesses.[15]

In the course of the following week, government forces used bulldozers to destroy all the buildings in the neighborhood according to the two witnesses. One woman, who observed the destruction of Wadi al-Jouz from her house across the highway, told Human Rights Watch:

I could see the neighborhood from my balcony. First I saw big trucks, accompanied by the military, taking things from the houses in the neighborhood. Then bulldozers started destroying the houses. The government said that a lot of rebels were hiding in Wadi al-Jouz.[16]

According to the other witness, the Syrian army used megaphones and told the residents they had one hour to pack their things.[17]

Satellite imagery recorded on April 30 and May 29, 2013, confirm the total demolition of 10 hectares of buildings, also showing heavy construction machinery such as bulldozers and excavators in the area.[18]

While local residents admitted that many buildings in the Wadi al-Jouz neighborhood had been built without the appropriate permissions, the army’s behavior after the demolition of the neighborhood indicates that it had little to do with permissions. A woman who lived in a neighboring district told Human Rights Watch:

After the demolition, the army came to our neighborhood, saying through loudspeakers that they would destroy our neighborhood like they destroyed Wadi al-Jouz and Masha` al-Arb`een should a single bullet be fired from here.[19]

III.Demolitions in Qaboun neighborhood, Damascus

Dates of demolitions: July 21-October, 2012; June-July, 2013 (approximate)[20]

Estimated area demolished: 18 hectares

Satellite imagery reviewed by Human Rights Watch show that buildings covering an area measuring 18 hectares were demolished in the Qaboun neighborhood in northern Damascus in two waves. The satellite photographs indicate that the first wave of demolitions took place between July 16 and October 3, 2012, the second between July 1 and November 20, 2013.[21]

The first wave appears to have been directly related to intensive clashes between government and opposition forces in mid-July, 2012. On July 15, clashes, described as the “fiercest fighting yet” in the capital, were reported in the southern districts of Tadamoun, Midan, and Kafr Souseh, and shortly thereafter in the northern districts of Barzeh and Qaboun.[22]

Government forces gradually forced the opposition to retreat. Walid, a local resident and activist, told Human Rights Watch that government forces launched a major offensive against the district, using helicopters, artillery, and tank fire around July 16, 2012. After several days of fighting, government forces accompanied by shabeeha, pro-government militias, entered the district, according to him, and started to loot houses and shops. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported on July 19, 2012 that the Syrian army had stormed the Qaboun district with “a large number of tanks.”[23] By July 23, government officials and opposition activists said that government forces had largely regained control in Damascus.[24]

After opposition forces retreated from Qaboun, government forces started demolishing houses and shops in the neighborhood. Human Rights Watch interviewed two local residents who witnessed the demolitions. One local restaurant owner told Human Rights Watch:

Around 9:30 a.m. one morning, Syrian security forces arrived in our neighborhood and asked us to leave the premises immediately. I saw three bulldozers with them. They did not give us any prior warning. They just showed up unannounced. When I asked why, the soldier said ‘no more questions’ or else I would be detained. I asked him if I could remove the things in the restaurant, but he said no. I had a motorcycle but they didn’t allow me to take it and forced me to leave on foot. As I was walking I looked back and I saw the bulldozer demolishing my shop. The shop was opened by my grandfather many years ago. I personally managed the restaurant for eight years. Before my eyes, all of my family’s hard work was destroyed in one second.[25]

Walid told Human Rights Watch that the army started demolishing buildings on July 21, 2012 and that the operation lasted for about 50 days. He told Human Rights Watch:

The army demolished 1,250 shops and 650 homes. Eighteen-hundred families had to evacuate. There were two or three families in every house. The Syrian army gave the shop owners 24 hours to empty their shops. Homeowners were given only three hours to pack their stuff and leave. It was not enough time. People barely took anything with them.[26]

Several videos posted on YouTube show demolitions in Qaboun in progress or the aftermath. In one video posted in July, an excavator demolishes houses while being guarded by what appears to be a single main battle tank.[27] Several similar videos posted in September show that the demolition operation continued at that time.[28]

Walid told Human Rights Watch that the areas demolished were the ones where the heaviest fighting took place. He told Human Rights Watch:

The frontline [between the government and opposition forces] extended from the B`ali and `Ardyet neighborhoods, reaching the industrial area. Now both neighborhoods are completely destroyed and exposed enough for the government forces to spot any opposition attack.[29]

Human Rights Watch has not been able to find any government statement or decree explaining the reason for the demolitions in Qaboun. Human Rights Watch was also not able to identify any witnesses to the second wave of demolitions, which took place at some point between July 1 and November 20, 2013, according to satellite imagery.

IV. Demolitions in Tadamoun neighborhood, Damascus

Dates of demolitions: September 8-November 29, 2012; February 4-July 1, 2013;

Estimated area demolished: 15.5 hectares

Satellite imagery analyzed by Human Rights Watch show that buildings in an area measuring 15.5 hectares in the Tadamoun neighborhood in southern Damascus were demolished in two waves: the vast majority of demolition occurred at some point between September 8 and November 29, 2012, followed by more limited demolition at some point between February 4 and July 1, 2013.[30]

Local residents, media reports, and government and opposition statements indicate that the first wave of the demolitions in the Tadamoun district in Damascus followed the same pattern as the demolitions in the Qaboun district (see above). As one of the districts in Damascus under opposition control, Tadamoun saw some of the most intensive clashes of the battle for the capital that took place in July 2012. The neighborhood was described as the opposition’s “last stronghold” as government troops forced opposition fighters to retreat after heavy fighting.[31] Local residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch described fierce shelling of the neighborhood by government forces starting from July 15.[32] Satellite imagery shows active fire and a dense smoke plume on the rooftop of a six-story residential apartment building in the morning of July 16.[33]

According to two local residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the July 2012 fighting caused many residents to leave, and by early August, opposition fighters who had remained in the neighborhood also left, allegedly because they ran out of ammunition.[34] The claim that opposition fighters retreated in early August is consistent with official statements. On August 4, 2012 several media outlets quoted a military spokesperson saying that the army had “cleansed” several areas in Damascus, including Tadamoun, and that the situation was “excellent and stable.”[35]

The two local residents told Human Rights Watch that government forces started demolishing houses in Tadamoun using explosives and bulldozers in September 2012.[36] The first signs of demolition are visible in satellite imagery recorded on September 8.[37] The satellite imagery, showing relatively neat piles of rubble where there were once houses, indicates that the demolition was carried out in a controlled and professional manner.

According to Ahmad who witnessed the destruction, residents received very short warning. He said:

Owners were given one hour to evacuate their homes. I saw people throwing their belongings from the windows. I wanted to help but I was afraid because the Syrian army was there.[38]

The demolitions were also reported by an international journalist who visited Tadamoun in mid-October 2012 when demolitions were still taking place.[39]

Satellite imagery and videos posted on YouTube show that government forces also demolished 12 high-rise residential apartment buildings by controlled explosions in the neighborhoods of al-Zahirat and al-Zohour (al-Qazzaz), adjacent to Tadamoun, between September 22 and November 29, 2012.[40]

Human Rights Watch was not able to identify any witnesses to the second wave of demolitions between February and July 2013 or find any official government statement or decree about the demolitions in Tadamoun.

V. Demolitions in Barzeh neighborhood, Damascus

Dates of demolitions: October 2012; February-July, 2013 (approximate)[41]

Estimated area demolished: 5.3 hectares

In the Barzeh neighborhood in northern Damascus, government forces demolished a total of 5.3 hectares of buildings in two waves: in October 2012 and at some point between February and late July 2013.[42]

According to Bassam, whose house was demolished, government officials justified the demolitions by referring to a decades-old 1960s decree authorizing the widening of the street as part of an urban planning effort.[43] “Everybody knew about this decree,” he told Human Rights Watch. “So when my brother and I decided to buy a piece of land in that area, we made sure that the property was located more than 20 meters from the street in case the government would decide to implement it.”[44] Human Rights Watch has not been able to obtain a copy of the decree.

But according to Bassam, when government forces demolished houses along the Tishreen Hospital Street during two weeks in October 2012, they also demolished his house, which he claimed was located more than 20 meters from the road.[45] Satellite imagery confirming both waves of demolition, shows that all houses within approximately 45 meters on either side of the road, and not 20 meters as the decree allegedly authorizes, were demolished.[46]

Bassam told Human Rights Watch that he tried to complain to the authorities, but that it had been useless:

My cousin and I went to the governor’s office in Damascus and asked for compensation. Of course, they said no. They told us that the demolition was ordered by this decree and we should have known about this before we bought the land. When we explained that our house is not within the 20 meter zone they told us to leave.[47]

Bassam told Human Rights Watch that he had both a document confirming his ownership of the land and a construction permit for his house.[48] Human Rights Watch has not been able to verify this claim.

However, the location and context of the demolitions in the Barzeh neighborhood indicate that the demolitions were related to the ongoing conflict. Both the demolished areas were located in the immediate vicinity of the Tishreen Military Hospital, one of the main hospitals receiving and treating wounded government soldiers.[49] The area is also located at the very edge of Damascus and opposition fighters regularly used the road to move from fields outside the city where they hid, to the area around the Abu Barzeh mosque, where they staged protests, according to Bassam.

The October demolitions removed all buildings within 45 meters of the road to the south of the hospital. The second stage of demolitions destroyed more than 50 buildings just to the south and east of the hospital compound.

Media reports indicate that government and opposition forces clashed several times in the area in the weeks leading up to the demolitions. Media also reported several attacks on and explosions at government checkpoints and police-stations.

One international journalist who visited the hospital noted in an article in December 2012 that buildings on both sides of the road for 90 meters (100 yards) had been flattened by bulldozers to make sniping and ambushes more difficult and cited the director of the hospital saying that six doctor and four ambulance drivers had been killed in a year, possibly when trying to get to the hospital, although this is not specified in the article.[50]

According to Bassam, snipers appeared on top of several buildings including the Tishreen Hospital and the public education center after the demolitions. Because of the demolitions, the snipers were able to monitor a significant area along the road. Bassam told Human Rights Watch that the opposition fighters moved to another area in Barzeh after the demolitions and the protests stopped because the snipers made it too dangerous for protesters to gather.[51]

While there are some reports of clashes in the area at the time of the demolitions, a video posted on YouTube on October 6 shows an excavator tearing down a house while people in civilian clothes are standing in the street and what appear to be civilian cars passing by.[52]

While opposition attacks on the hospital or medical personnel might have justified protective measures by the authorities, the demolition of dozens of houses appears disproportionate. The authorities do not appear to have offered any compensation to owners, according to the one owner that Human Rights Watch interviewed.

VI. Demolitions around Mezzeh airport, Damascus

Dates of demolitions: August, 2012; December, 2012-March, 2013

Estimated area demolished: 41.6 hectares

Satellite imagery reviewed by Human Rights Watch shows that a total of 41.6 hectares of buildings was demolished around Mezzeh military airport, a military base in the southern Damascus suburbs, which is base of the Air Force Intelligence Service, one of Syria’s four main security services. According to the imagery, the demolitions took place mainly at some point between December 2012 and July 2013.[53] Limited demolitions took place also earlier, in August 2012.

When interviewed about demolitions in Damascus Hussein Makhlouf, the governor of the Damascus countryside to which the demolished areas around the Mezzeh airport belong, referred to decree 66, which was issued by President Bashar al-Assad on September 18, 2012. [54] The decree stipulates the development of two areas with illegally constructed houses, one of which seems to be the south-eastern side of the Mezzeh airport that was demolished. [55] Makhlouf said that demolitions would soon be carried out in Daraya, Harasta and Yalda. Although the decree refers to illegally built houses, Makhlouf in the interview said that the demolitions were essential to drive out rebels, according to the article.

The Mezzeh military airport and the adjacent demolished area link Damascus city and Daraya and Moadamiya, two towns in the Damascus countryside known for being opposition strongholds. Initial peaceful protests eventually turned into armed opposition and a significant number of armed opposition fighters used the town to stage attacks on government targets, including the airport. In August 2012, government forces launched a massive offensive against the two towns, described as one of the deadliest government assaults in the Syrian conflict up until that point.[56]

Satellite imagery shows that a small number of buildings just north-east of the Mezzeh airport were demolished in the same period as the August offensive, between August 22 and 26.[57] According to Yasser, a local resident interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the demolished houses were located near military barracks, which had come under attack by opposition fighters during the August clashes. Human Rights Watch has not been able to interview witnesses to these demolitions and more investigation is needed to determine whether this limited wave of demolitions was a violation of international law.

The second, more significant, wave of demolitions started in December 2012. According to Yasser, this phase followed an opposition attack on a government checkpoint at a key intersection on November 25 and killed all the soldiers there.[58] Yasser told Human Rights Watch that government forces easily resumed control of the residential area immediately adjacent to the airport called Khaleej.[59]

Yasser said that his father and grandfather who were living in the Khaleej at the time fled the area on November 25 as soon as they heard about the attack, fearing government retaliation against the civilian population.[60] Yasser told Human Rights Watch that he believed that around 3,000 buildings might have been demolished in total around the Mezzeh airport.[61] Satellite imagery shows that all buildings in a triangle between the airport and two roads to the south and east of the airport have been demolished. Although it is difficult to establish the exact number, satellite imagery indicates that several thousand buildings were demolished.[62]

Compared to the demolitions in the Tadamoun neighborhood, for example, at least some of those around the Mezzah airport appear to have been much less controlled and professional. Videos posted on YouTube in February, 2013, show several buildings being demolished by large uncontrolled explosions, throwing large pieces of building material hundreds of meters into the air.[63]

While opposition attacks on the Mezzeh military airport might have justified the government taking certain measures, the demolition of hundreds of residential buildings appears to have been disproportionate.

VII. Demolitions in Harran Al-`Awamid Neighborhood, Damascus

Date of demolitions: February-April, 2013 (approximate)

Estimated area of destruction: 14.3 hectares

In Harran al-`Awamid, a town of about 12,000 people three kilometers north-east of the Damascus International Airport, government forces demolished a total of 14.3 hectares of buildings in early 2013.

According to media reports around February 12, 2013, the Syrian authorities had issued a decree to expropriate land in several areas around the international airport, including Harran al-`Awamid, to build power lines.[64]

However the circumstances of the demolitions, witness and government statements indicate, that the operation was related to the armed conflict. On January 28, just two weeks before media reports about the expropriation decree, opposition fighters in Harran al-`Awamid attacked the only government checkpoint in the town, forcing government troops to abandon it, according to activists and Tarik, a local resident interviewed by Human Rights Watch.[65] In response, government forces launched artillery, rocket and aerial attacks on the town, which caused the majority of the population to leave.[66] Satellite imagery shows damage consistent with the allegations of shelling in the period between August 28, 2012 and May 23, 2013, the two dates for which imagery was available to Human Rights Watch.[67]

In addition to the attack on the government checkpoint, opposition forces, some of whom were likely based in Harran al-`Awamid, had been conducting attacks on the airport in the months before the demolitions, which likely also factored into the government’s decision to attack and destroy the town.[68] Government statements and pro-government media reports about Harran al-`Awamid before, during, and after the demolitions focused on the clashes between government and opposition forces. In December, pro-government media reported that government forces had killed several “terrorists” in Harran al-`Awamid and confiscated weapons and ammunition in their possession.[69] SANA, Syria’s state-run news agency, published a similar statement in February.[70] And on April 7, SANA announced that Harran al-`Awamid, among other places, had been cleaned of “terrorists.”[71]

Satellite imagery confirms that about 14.3 hectares of buildings were destroyed between August 28, 2012 and May 23, 2013, the dates of the imagery analyzed by Human Rights Watch.[72] Limited satellite coverage over this area prevented a more accurate determination of the time frame from satellite imagery alone, but in a posting on its Facebook page on February 17, the Coordination Council of Greater Damascus wrote that bulldozers had been demolishing houses in the town for ten days, indicating that the demolitions in Harran Al `Awamid started around February 7.[73]

Tarik, a local resident who witnessed the demolitions, told Human Rights Watch that he believed the authorities had demolished about 500 houses, half of all the houses in in Harran Al `Awamid.[74] This is consistent with the damage visible on the May satellite imagery, which shows that the majority of houses in the center were demolished. There are also multiple areas of extensive building demolition within several kilometers of the center of town radiating in most directions. According to Tarik, people dressed in civilian clothes looted furniture from people’s houses before they were demolished by explosives and heavy construction machinery.

Tarik also said that local residents had received no warning or compensation and no formal explanation about the demolitions.[75]

While opposition attacks on the airport might have justified the government taking protective measures, the demolition of hundreds of houses, many kilometers away from the airport, appears to have been disproportionate.

VIII. Legal Framework

International humanitarian law, the laws of war, governs fighting between Syrian government forces and opposition armed groups. This law binds all parties to an armed conflict, whether they are states or non-state armed groups.[76]

The Syrian government has sought to justify the destruction of property in various locations in Syria referring to illegal construction and urban planning efforts. But the circumstances of the demolitions, as detailed in this report, indicate that the demolitions were related to the ongoing armed conflict. While Syrian government forces have destroyed property for legitimate military reasons in some cases, Human Rights Watch found that the large-scale destruction of property in the cases detailed in this report violated Syria’s international legal obligations.

The laws of war governing the methods and means of warfare are primarily found in the Hague Regulations of 1907 and the First Additional Protocol of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol I).[77] Although neither treaty formally applies to the internal armed conflict in Syria, most of the provisions of both are considered reflective of customary law.[78] Also applicable is article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 (Common Article 3), which concerns the treatment of civilians and combatants who are no longer taking part in the fighting.[79]

Central to the law regulating conduct of hostilities is the principle of distinction, which requires parties to a conflict to distinguish at all times between combatants and civilians. Operations may be directed only against combatants and other military objectives; civilians and civilian objects may not be the target of attack.[80]

Civilian objects have been defined as all objects that are not military objectives.Military objectives are those objects which “by their nature, location, purpose or use make an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage” [emphasis added].[81] In cases of doubt there is a presumption that objects normally dedicated to civilian purposes, for example houses and other dwellings, schools, places of worship, and hospitals, are not subject to attack.[82] Civilian objects remain protected from attack, unless and only for such time that they become military objectives. Once a civilian object that is a military objective, such as a house used as a military headquarters, ceases being used to further the military aims of the adversary, it is no longer subject to attack.[83]

Deliberate, indiscriminate or disproportionate attacks against civilians and civilian objects are prohibited. Attacks are indiscriminate when they are not directed at a specific military objective or employ a method or means of warfare that cannot be directed at a military objective or whose effects cannot be limited.[84] A disproportionate attack is one in which the expected incidental loss of civilian life and damage to civilian objects would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated.[85]

In the conduct of military operations, parties to a conflict must take constant care to spare the civilian population and civilian objects from the effects of hostilities.[86] Parties are required to take precautionary measures with a view to avoiding, and in any event minimizing, incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, and damage to civilian objects.[87]

Before conducting an attack, parties to a conflict must do everything feasible to verify that the persons or objects to be attacked are military objectives and not civilians or civilian objects.[88] In its Commentary to Protocol I, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) explains that the requirement to take all “feasible” precautions means, among other things, that those conducting an attack are required to take the steps needed to identify the target as a legitimate military objective “in good time to spare the population as far as possible.”[89] The United Kingdom military manual illustrates the rule as follows:

If, for example, it is suspected that a schoolhouse situated in a commanding tactical position is being used by an adverse party as an observation post and gun emplacement, this suspicion, unsupported by evidence, is not enough to justify an attack on the schoolhouse.[90]

The Hague Regulations forbid during hostilities the unnecessary destruction of the enemy’s property. [91] The Geneva Conventions prohibit, as a grave breach during international armed conflicts, the “extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly.” [92] The prohibition on “wanton destruction” is a longstanding rule of customary international law, dating back at least to the US Lieber Code of 1863, the first modern codification of the laws of war. [93]

The rule of military necessity was defined in the Lieber Code, and later adopted by the ICRC, as “the necessity of those measures which are indispensable for securing the ends of the war, and which are lawful according to the modern law and usages of war.”[94] In other words, military necessity cannot be used as an excuse to violate explicit law-of-war provisions, because the requirements of military necessity have already been incorporated into law-of-war rules.[95] Military necessity incorporates the fundamental legal obligation to avoid damage to civilian property by distinguishing military objectives from civilian objects, only permitting attacks on the former, and prohibiting such destruction if the expected civilian harm is disproportionate to the direct military advantage anticipated.

The concept of military necessity thus rejects measures that are viewed as a means to justify an otherwise unlawful attack, are not intended to defeat the enemy or that violate the laws of war by excessively damaging civilian objects in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated from the attack. While the rule of military necessity grants military planners considerable autonomy about the appropriate tactics for carrying out a military operation, this autonomy remains subservient to the laws and customs of war. [96]

Human Rights Watch found that in the incidents investigated in this report, the destroyed properties were not military objectives as the term is widely understood. Thus, even where the Syrian government asserted a military rationale for the destruction of the property, the objects still did not meet the requirements for a military objective and thus were not subject to attack or destruction.

Human Rights Watch distinguishes these cases from those in which civilian property is a military objective, such as when combatants use residential houses for planning, staging of attacks, and storage of weapons and ammunition.

As noted, a civilian object becomes subject to attack as a military objective when it makes an effective contribution to military action and its destruction in the circumstances ruling at the time provides a definite military advantage. These criteria are critical for determining whether the destruction of property is lawful. Thus, according to the US army field manual’s regulations for destruction in the context of hostilities, there must be a “reasonably close connection between the destruction of property and the overcoming of the enemy’s army.”[97]

In some instances detailed above, it appeared that the Syrian government forces destroyed property either because of its past use as a military objective, that is for possible punitive reasons, or because of its predicted future use as a military objective, that is for anticipatory reasons. International humanitarian law prohibits the punitive destruction of property and places sharp limits on what constitutes a military objective’s future use.

Destruction of property that is no longer or was previously used as a military objective is not permitted. With regard to recently captured areas, the UK military manual states:

[O]nce the defended locality has surrendered or been captured, only such further damage is permitted as is demanded by the exigencies of war, for example removal of fortifications, demolition of military structures, destruction of military stores, or measures for the defence of the locality. It is not permissible to destroy a public building or private house because it was defended.[98]

One respected academic commentator has likewise criticized as a matter of law the destruction of houses for punitive purposes:

Destruction of houses as a (legitimate) integral part of military operations must be distinguished from demolitions of residential buildings carried out as a post-combat punitive measure.… [I]t is wrong to believe that, once used for combat purposes, a civilian object (like a residential building) is tainted permanently as a military objective. As long as combat is in progress, the destruction of property . . . is permissible, if rendered necessary by military operations. Yet, subsequent to the military operations, destruction of property is no longer compatible with modern [law of international armed conflict].[99]

A civilian object can be a military objective if the concrete advantage it provides at the time is of an anticipatory nature. Thus, amilitary unit can destroy a house that would block fields of fire during an expected and imminent enemy attack. Nonetheless, the presumption that a civilian object is not a military objective remains. Thus, acting on the basis of possible enemy intentions is an insufficient basis for attacking a civilian object. The above commentator writes that “field intelligence revealing that the enemy intends to use a particular school as a munitions depot does not justify an attack against the school as long as the munitions have not been moved in.” He adds: “Purpose is predicated on intentions known to guide the adversary, and not on those figured out hypothetically in contingency plans based on a ‘worst case scenario.’”[100]

As the ICRC’s authoritative Commentary on Protocol I states, “it is not legitimate to launch an attack which only offers potential or indeterminate advantages.”[101]Likewise, the authors of the New Rules for Victims of Armed Conflicts note that the military advantage must be “concrete and perceptible” and not “hypothetical and speculative.”[102]

The Eritrea Ethiopia Claims Commission, commenting on the destruction of civilian property by Ethiopian forces retreating from Eritrean territory, stated: “The Commission does not agree that denial of potential future use of properties like these, which are not directly usable for military operations, as are, for example, bridges or railways, could ever be justified under Article 53 [on the destruction of property].”[103]

According to the above commentator, “Certain objects are normally (by nature) dedicated to civilian purposes and, as long as they fulfill their essential function, they must not be treated as military targets.”[104] Objects such as civilian dwellings and schools may be military objectives when they are making an “effective contribution to military action…. The dominant consideration ought to be ‘the circumstances ruling at the time.’”[105]

Other academic commentators explain that the criterion that civilian objects be considered as offering a definite military advantage in the circumstances ruling at the time “is crucial”:

Without this limitation to the actual situation at hand, the principle of distinction would be meaningless, as every object could, in abstracto and under possible future developments, become a military objective. It would suffice that in future enemy troops could occupy a building and transform it into a military objective.[106]

Where destruction is permitted as a matter of imperative military necessity, it must not be disproportionate. That is, as noted above, it cannot be expected to cause damage to civilian objects that would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated. As the ICRC Commentary to the Fourth Geneva Convention states, “whenever it is felt essential to resort to destruction, the occupying authorities must try to keep a sense of proportion in comparing the military advantage gained with the damage done.” [107]

Lastly, in civilian areas that have not been under control by opposition forces, or where there is no imminent threat of such military use, a party to a conflict may have valid security reasons for destroying civilian property. Parties have an obligation, to the extent feasible, to remove civilian objects under their control from the vicinity of military objectives.[108] This could include destroying civilian structures near to army bases, airports and other military objectives. It is unlawful for such destruction to cause disproportionate civilian harm.

The eviction of the population and the destruction of homes may be subject to international human rights law, particularly the right to housing under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[109] Those evicted outside of active hostilities are entitled to adequate notice, genuine consultation, and adequate compensation or alternative housing.[110]

With respect to individual responsibility, serious violations of international humanitarian law committed with criminal intent are war crimes. During non-international armed conflicts, war crimes include “[d]estroying or seizing the property of an adversary unless such destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of the conflict,”[111] and collective punishments.[112]

Criminal intent has been defined as violations committed intentionally or recklessly.[113] Individuals may also be held criminally liable for attempting to commit a war crime, as well as assisting in, facilitating, aiding, or abetting a war crime. Responsibility may also fall on persons planning or instigating the commission of a war crime.[114] Commanders and civilian leaders may be prosecuted for war crimes as a matter of command responsibility when they knew or should have known about the commission of war crimes and took insufficient measures to prevent them or punish those responsible.[115]

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court includes wanton destruction as a war crime.[116] The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) concluded that the elements of the war crime of wanton destruction are met where: (i) the destruction of property occurs on a large scale; (ii) is not justified by military necessity; and (iii) the perpetrator acted with the intent to destroy the property or in reckless disregard of its likely destruction.[117] The ICTY elaborated that “the devastation of property is prohibited except where it may be justified by military necessity. So as to be punishable, the devastation must have been perpetrated intentionally or have been the foreseeable consequence of the acts of the accused.”[118]

Under international humanitarian law, states have a duty to investigate war crimes allegedly committed by members of their armed forces and other persons within their jurisdiction. Those found to be responsible should be prosecuted before courts that meet international fair trial standards or transferred to another jurisdiction to be fairly prosecuted.[119]

The laws of war also provide for a state to make full reparations, including directly to individuals, for the loss caused by violations of the laws of war.[120]

Acknowledgements

This report was researched by Ole Solvang, senior emergencies researcher, Anna Neistat, associate director for program, Lama Fakih, Syria and Lebanon researcher, and Diana Seeman, research assistant. Josh Lyons, satellite imagery analyst at Human Rights Watch, analysed the satellite imagery and video materials. Ole Solvang wrote the report, and Anna Neistat contributed to the writing.

The report was edited by Lama Fakih, Nadim Houry, deputy director in the Middle East and North Africa Division, Clive Baldwin, senior legal advisor, and Tom Porteous, deputy program director. Tamara Alrifai, Advocacy and Communications Director, Middle East and North Africa Division, also reviewed the report.

Production and coordination were provided by Kyle Hunter, associate in the Emergencies Division. Additional research assistance was provided by an intern with the Middle East and North Africa Division.

Grace Choi, publications director, managed the production of imagery and graphics. Amanda Bailly, multimedia coordinator, and Pierre Bairin, multimedia director, managed the production of video content. Kathy Mills, publications specialist, and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, prepared the report for publication.

We especially wish to thank Syrian victims and witnesses who shared their stories with us, as well as the Syrians who helped us in our research, often at great personal risk.

[1] Satellite imagery used in this report was recorded on the mornings of July 16, August 4 and 28, September 8, 22 and 28, October 3 and 13, November 29, 2012, February 4, April 30, May 23 and 29, July 1, and November 20, 2013. Imagery sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[2] “ إزالة مخالفات مشاع الأربعين ليس لتشريد الأهالي ,” (The removal of violations in Mosha’ al-Arb’eenis not fordisplacing residents) , Damas Post , October 9, 2012, http://www.damaspost.com/%D9%85%D8%AD%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%AA/%D8%A5%D8%B2%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A9-%D9%85%D8%AE%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%85%D8%B4%D8%A7%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B1%D8%A8%D8%B9%D9%8A%D9%86-%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%B3-%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%87%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%8A.htm (accessed January 9, 2014);

“ تطهير مناطق في الحجر الأسود بريف دمشق وعمليات نوعية في حلب ,”

( Clearing areas in Hajjar al-Aswadin Damascus Suburbs and uniqueoperationsin Aleppo)

Damas Post , September 20, 2012, http://www.damaspost.com/%D8%B3%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%A9/%D8%AA%D8%B7%D9%87%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D9%85%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%B7%D9%82-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D8%AC%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%AF-%D8%A8%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%81-%D8%AF%D9%85%D8%B4%D9%82-%D9%88%D8%B9%D9%85%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%86%D9%88%D8%B9%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%AD%D9%84%D8%A8.htm (accessed January 9, 2014).

[3] Human Rights Watch phone interview, January 30, 2013.

[4] Human Rights Watch phone interview, January 28, 2013; Human Rights Watch phone interview, January 11, 2012.

[5] Human Rights Watch phone interview, January 30, 2013.

[6] See for example, “ قواتنا المسلحةتقضي على عدد كبير من الإرهابيين في حلب وتكبدهم خسائر فادحة وتطهر حي جوبر بدمشق ,” (“ Our armed forces eliminated a large number ofterroristsin Aleppoand inflicted heavy losses on them andcleansed Jobarneighborhood [from terrorists]inDamascus”)

SANA state news agency, September 27, 2012, http://sana.sy/ara/336/2012/09/27/443895.htm (accessed january 9, 2014); “ وإصابة العشرات من الإرهابيين بعضهم من جنسيات عربية وأجنبية بأحياء بحلب وآخرون يستسلمون..ضبط سيارة محملة بأسلحة متنوعة في كراج الصناعة ,” (“ And wounding dozens ofterrorists, some of them Arab and foreignnationalities in Alepponeighborhoodsandotherssurrender..Seizinga car in industry garage loaded withvariety ofweapons”) , Syria Now, http://www.syrianow.sy/index.php?p=7&id=59339 (accessed January 9, 2014).

[7] Human Rights Watch phone interview, November 14, 2012.

[8] Human Rights Watch phone interview, January 30, 2013.

[9] Human Rights Watch phone interview, January 28, 2013.

[10] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: September 22, October 3 and 13, 2012; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid

[13] “ المباشرة بتنظيم حي مشاع وادي الجوز بمدينة حماة وإزالة كل أشكال المخالفات ,”( “Moving forth with organizing Mosha’ Wadi Al Joz neighborhoodin thecityof Hamaand removingallforms ofviolations”) , SANA state news agency, May 1, 2013, http://sana.sy/ara/347/2013/05/01/480181.htm (accessed January 9, 2014).

[14] “Syrian Arab Army Restore Security to Several Areas in Hama,” Syria Times, May 1, 2013, http://syriatimes.sy/index.php/news/local/4788-syrian-arab-army-restore-security-to-several-areas-in-hama (accessed August 1, 2013);

القضاء على أعداد من الإرهابيين ودك أوكارهم وتدمير أدوات إجرامهم في أرياف دمشقوحمص واللاذقية وحلب" ,“ (“ Eliminating terrorists and destroying their hideouts and their criminal tools in rural Damascus, Homs, Latakia and Aleppo”) , SANA state news agency, May 2, 2013,

http://sana.sy/ara/336/2013/05/02/480123.htm (accessed January 9, 2014); “ سانا: الجيش السوري يعيد الأمن الى وادي الجوز ويضبط مصنعاً للعبوات الناسفة ,” (“ SANA : Syrian armyrestoressecurityinWadi Al Jozandcaptures a factory for manufacturingimprovised explosive device”) , Almada, May 1, 2013, http://almada.ndpcdn.com/news/index/4300/%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%A7--%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%B4-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A-%D9%8A%D8%B9%D9%8A%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%89-%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%88%D8%B2-%D9%88%D9%8A%D8%B6%D8%A8%D8%B7-%D9%85%D8%B5%D9%86%D8%B9%D8%A7%D9%8B-%D9%84%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%A8%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%B3%D9%81%D8%A9 (accessed January 9, 2014).

[15] Human Rights Watch interview, Lebanon, July 11, 2013.

[16] Human Rights Watch interview, Lebanon, July 11, 2013.

[17] Human Rights Watch phone interview, July 31, 2013.

[18] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: April 30, and May 29, 2013; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[19] Human Rights Watch interview, Lebanon, July 11, 2013.

[20] Human Rights Watch phone interview, November 5, 2012.

[21] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: July 16, August 4 and 28, September 8 and 22, October 3, 2012, February 4, July 1, and November 20, 2013; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[22] Erika Solomon, “Fiercest fighting yet reported inside Damascus,” Reuters, July 15, 2012, http://uk.reuters.com/article/2012/07/15/uk-syria-crisis-idUKBRE8640R320120715 (accessed August 10, 2013).

[23] “Tanks roll on Damascus as violence reigns,” Al-Jazeera English, July 19, 2012, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2012/07/201271961645358140.html (accessed January 9, 2014).

[24] “Syrian Army Retakes Most of Damascus,” Naharnet, July 23, 2012, http://www.naharnet.com/stories/en/47542-syrian-army-retakes-most-of-damascus (accessed January 9, 2014); Bassem Mroue and Zeina Karam, “Syria conflict: Damascus Suffers Destruction, Hunger As Fighting hits Country’s Heart,” Huffington Post, July 23, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/07/23/syria-conflict-damascus_n_1695623.html (accessed January 9, 2014).

[25] Human Rights Watch phone interview, November 24, 2013.

[26] Human Rights Watch phone interview, November 5, 2012.

[27] “ هدم المنازل والمحلات بالدبابات في القابون 28-7-2012 ,” (“The demolition of houses and shops with tanks in Qaboun 28-7-2012”), July 28, 2012, video clip, YouTube, http://youtu.be/b-8EHnmE7_4 (accessed August 12, 2013); Human Rights Watch identified the exact location by creating a photomosaic of the video and comparing this with satellite imagery.

[28] “ هاااااام دبابة تهدم المحلات في حي القابون 23-9-2012 ,” (“Important tank destroyed shops in the Qaboun neighborhood 23/09/2012”),September 23, 2012, video clip, YouTube, http://youtu.be/e3j9Lh9Fm08 (accessed August 13, 2013); “ دمشق حي القابون :: الدمار في المنطقة الصناعية ,” (“Damascus Qaboun neighborhood: destruction in the industrial area”), September 12, 2013, video clip, YouTube, http://youtu.be/puKtqPdumv8 (accessed August 13, 2013); “ تهديم وتهبيط المنازل في القابون 29-9-2012 ,” (“Demolition and destruction of homes in Qaboun 29/09/2012”), September 29, 2013, video clip, YouTube, http://youtu.be/peyoOgWkMLw (accessed August 13, 2013); “ هاام دبابات الاسد تقوم بتدمير حي القابون 27-9-2012 ,” (“Important Assad tanks destroys Qaboun neighborhood 27/09/2012”), September 27, 2012, video clip, YouTube, http://youtu.be/MkYM4Nm2wE0 (accessed August 13, 2013); “ قابون - هدم المنازل بالدبابات - 29-9-2012 , “ (“The demolition of houses with tanks - 29/09/2012”), September 29, 2012, video clip, YouTube, http://youtu.be/5GBjOn3nenI (accessed August 13, 2013).

[29] Human Rights Watch phone interview, November 5, 2012.

[30] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: September 8 and 22, October 3, 2012, February 4, and July 1, 2013; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[31] “Syria crisis: UN Assembly condemns Security Council,” BBC News, August 3, 2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-19106250 (accessed August 8, 2013).

[32] Human Rights Watch phone interview, February 18, 2013; Human Rights Watch phone interview February 19, 2013.

[33] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: September 8 and 22, October 3, 2012, February 4 and July 1, 2013; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[34] Human Rights Watch phone interview, February 21, 2013; Human Rights Watch phone interview, February 19, 2013.

[35] See for example, “Syrian Army Controls All of Damascus,” Naharnet, August 4, 2012, http://www.naharnet.com/stories/ar/48953(accessed August 5, 2013); “Syrian army declares Damascus' rebellious district ‘cleaned of armed groups’,” Xinhua News [English edition], August 5, 2012,http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/world/2012-08/05/c_123529591.htm (accessed August 13, 2013).

[36] Human Rights Watch phone interview, February 21, 2013; Human Rights Watch phone interview, February 19, 2013.

[37] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: September 8 and 22, October 3, 2012, February 4 and July 1, 2013; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[38] Human Rights Watch phone interview, February 21, 2013.

[39] Sam Dagher, “Fighting to Hold Damascus, Syria Flattens Rebel 'Slums',” Wall Street Journal, November 27, 2012,http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204707104578092113759746982.html?mod=googlenews_wsj#articleTabs=article

[40] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: September 22, and November 29, 2012; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014. See also, “ الشبيحة تقوم بتفجيرالمباني في الزاهرة الجديدة 9 10 2012 ,” (“Shabeeha bombs the buildings in new al-Zahra 9 10 2012”), October 9, 2012, video clip, YouTube, http://youtu.be/Ol6w_hfwCjs (accessed August 12, 2013); “ تـفجير وهدم الابنية في دمشق- الزاهرة من قبل قوات الاسد ,” (“Bombing and demolition of buildings in Damascus – al Zahra by Assad forces”), September 24, 2012, video clip, YouTube, http://youtu.be/Lk8D9nJm-R4 (accessed August 10, 2013).

[41] Human Rights Watch phone interview, July 4, 2013.

[42] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: September 22, October 3, and November 29, 2012, and February 4 and July 1, 2013; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[43] Human Rights Watch phone interview, July 4, 2013. Some media articles about the demolition in Barzeh refer to decree 2190 from 1975. “ قالت إنها ستؤمن منازل للمستحقين في برزة

محافظة دمشق: تم توجيه 155 إنذاراً لشاغلي عقارات مشروع طريق السلمية ,” It [government] said it will provide houses to the beneficiaries in Barzeh Damascus Governorate: 155 warnings was directed to the occupants of the real estate project of al-Selmia road”

, Syria Steps, January 22, 2011, http://www.syriasteps.com/?d=207&id=62019 (accessed January 9, 2014); “ الاستملاك مرسوم تتوارثه الأجيال دون تنفيذ !!,”( Expropriation decree inherited by generations without impelmentation!!!”) , Jouhina, May 5,2007,

http://alsmu.com/jouhina.com/archive_article.php?id=1716 (accessed January 9, 2014).

[44] Human Rights Watch phone interview, July 4, 2013.

[45] Human Rights Watch phone interview, July 4, 2013.

[46] Satellite imagery recorded on September 22, October 3, and November 29, 2012; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[47] Human Rights Watch phone interview, July 4, 2013.

[48] Human Rights Watch phone interview, July 4, 2013.

[49] Deborah Amos, “At Syrian Military Hospital, The Casualties Mount,” NPR, June 12, 2012, http://www.npr.org/2012/06/12/154858481/at-syrian-military-hospital-the-casualties-mount (accessed January 9, 2014); Jonathan Steele, “Fear follows the ‘martyrs’ on the roads to Damascus,” The Guardian, August 10, 2012, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/aug/10/damascus-syrian-military-hospital; Patrick Cockburn, “Fear and loathing of Syria’s fallen soldiers,” The Independent, December 11, 2012, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/fear-and-loathing-of-syrias-fallen-soldiers-8406496.html (accessed January 9, 2014).

[50] Ibid.

[51] Human Rights Watch phone interview, July 4, 2013.

[52] “ هدم منازل ومحلات المدنيين على طريق مشفى تشرين 6/10/2012 ,” (“T he demolition of houses and shops on Teshreen hospital road October 6/10/2012 " ”), October 6, 2012, video clip, YouTube, http://youtu.be/afUt8ERBRSo (accessed January 9, 2014).

[53] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: August 4 and 28, September 8, and November 29, 2012, February 4, and July 1, 2013; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[54] Sam Dagher, “Fighting to Hold Damascus, Syria Flattens Rebel ‘Slums’,” The Wall Street Journal, November 27, 2012, http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052970204707104578092113759746982 (accessed January 9, 2014).

[55] “ مرسوم بإحداث منطقتين تنظيميتين في نطاق محافظة دمشق ضمن المصور العام للمدينة ,” (“ The creation of two organizational decrees in the province of Damascus within the general scope of the City ”), SANA state news agency, September 20, 2012, http://sana.sy/ara/2/2012/09/20/442479.htm (accessed January 9, 2014).

[56] http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/27/world/middleeast/dozens-of-bodies-are-found-in-town-outside-damascus.html

[57] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: August 4 and 28; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[58] Human Rights Watch interview, Lebanon, June 19, 2013.

[59] Human Rights Watch interview, Lebanon, June 19, 2013.

[60] Human Rights Watch interview, Lebanon, June 19, 2013.

[61] Human Rights Watch interview, Lebanon, June 19, 2013.

[62] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: August 4 and 28, September 8, and November 29, 2012, February 4, and July 1, 2013; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[63] “ تفجير البيوت المحيطة بمطار المزة العسكري - السبت 16-2-2013 ,” (“Bombing of houses surrounding the Mezzeh military airport - Saturday 16/02/2013”), February 16, 2013, video clip, YouTube, http://youtu.be/Vsjg-KIkMMM (accessed August 13, 2013).

[64] Media reports refer to decree 18905. Human Rights Watch has not been able to obtain a copy of the decree itself. The most recent decree on the Syrian government’s site at the time of writing was issued in September 2012. Syrian Government, “Decisions/Resolutions,” (2007-2012), http://www.youropinion.gov.sy/ViewDecisions?type=k (accessed August 13, 2013); “ الحكومة السورية تقرر استملاك مناطق على طريق مطار دمشق الدولي ,” [The Syrian government decides to expropriate areas on the road to Damascus International Airport],”Sham Times, February 10,2013, http://www.chamtimes.com/157480.html, (accessed August 12, 2013); “ الحكومة السورية تقرر استملاك مناطق على طريق مطار دمشق الدولي ,” (“The Syrian government decides to expropriate areas on the road to Damascus International Airport”), http://www.dp-news.com/pages/detail.aspx?articleid=139831 (accessed August 13, 2013); “ الحكومة السورية تستملك أراضي قرى محيطة بالمطار لتوسيع شبكة الكهرباء والأهالي يشككون في نواياها ,” (“Syrian government expropriates the villages surrounding the airport lands for the expansion of the electricity grid and residents are skeptical about the intentions”), Anba Moscow, February 12, 2013, http://anbamoscow.com/aworld/20130212/380087626-print.html (accessed August 13, 2013).

[65] Human Rights Watch phone interview, July 26, 2013. See also: ““ الحكومة السورية تستملك أراضي قرى محيطة بالمطار لتوسيع شبكة الكهرباء والأهالي يشككون في نواياها ,” (“Syrian government expropriates the villages surrounding the airport lands for the expansion of the electricity grid and residents are skeptical about the intentions”), Anba Moscow, February 12, 2013, http://anbamoscow.com/aworld/20130212/380087626-print.html (accessed August 13, 2013).

[66] Human Rights Watch phone interview, July 26, 2013.

[67] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: August 28, 2012, and May 23, 2013; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[68] “Syria conflict: 'Fierce clashes' near Damascus airport,” BBC News, November 29, 2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-20547799 (accessed August 12, 2013); “ المجلس العسكري يتعهد السيطرة على مطار دمشق ,” (“Military Council vows to control Damascus airport”), Al Yaum, November 30, 2012, http://www.alyaum.com/News/art/64371.html (accessed August 8, 2013).

[69] “ الجيش العربي السوري يواصل تطهير ريف دمشق.. وقتلى الإرهابيين بالمئات أغلبهم من جنسيات غير سورية ,”(“ Syrian Arab army continues to cleanse Damascus killing hundreds of terrorists, mostly from non-Syrian nationalities”), Al Baath Media, December 8, 2012, http://www.albaathmedia.sy/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=66655 (accessed August 10, 2013).

[70] “ سلسلة عملياتضد الإرهابيين في ريف دمشق وإيقاع أعداد منهمبين قتيل ومصابفي حلب وريفي إدلب وحمص , ” (“Series of operations against the terrorists in Damascus and a number of them dead and injured in a rural Aleppo and Idlib, Homs”), SANA state news agency, February 2, 2013, http://sana.sy/ara/336/2013/02/02/464988.htm (accessed August 13, 2013).

[71] “ إتمام الطوق على الغوطة الشرقيةوتنظيف المنطقة الممتدة من مطار دمشقإلى جنوب غرب الضمير من الإرهابيين , ” (“Surrounding East Gouta and cleaning the area from terrorists from Damascus Airport to the south-west”), SANA state news agency, April 7, 2013, http://sana.sy/ara/336/2013/04/07/476048.htm (accessed August 5, 2013).

[72] Satellite imagery dates analyzed by Human Rights Watch: August 28, 2012, and May 23, 2013; Sources: EUSI, USG and Astrium; Copyright: DigitalGlobe 2014 and CNES 2014.

[73] Post to Coordinating Greater Damascus, Facebook, February 17, 2013, https://www.facebook.com/Damas.Biggest.Org/posts/482698551787268 (accessed January 9, 2014).

[74] Human Rights Watch phone interview, July 26, 2013.

[75] Ibid.

[76] For a detailed discussion on applicability of international humanitarian law to the conflict in Syria, see Human Rights Watch, Syria – “They Burned My Heart,” May 3, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2012/05/02/they-burned-my-heart-0 . The International Committee of Red Cross (ICRC) concluded in July 2012 that the situation in Syria amounts to a non-international armed conflict. See: ICRC, “Syria: ICRC and Syrian Arab Red Crescent maintain aid effort amid increased fighting,” July 17, 2012, http://www.icrc.org/eng/resources/documents/update/2012/syria-update-2012-07-17.htm (accessed February 2, 2013). International human rights law, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), also continue to be applicable during armed conflicts. These treaties guarantee all individuals their fundamental rights, many of which correspond to the protections afforded under international humanitarian law including the prohibition on torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, non-discrimination, and the right to a fair trial for those charged with criminal offenses. The ICECR addresses the rights to housing, highest attainable standard of health, and employment, among other rights.

[77] Hague Convention IV - Laws and Customs of War on Land : 18 October 1907 (Hague Regulations), 36 Stat. 2277, 1 Bevans 631, 205 Consol. T.S. 277, 3 Martens Nouveau Recueil (ser. 3) 461, entered into force Jan. 26, 1910; Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I) of 8 June 1977, 1125 U.N.T.S. 3, entered into force December 7, 1978. The “means” of combat generally refer to the weapons used, while “methods” refer to the manner in which such weapons are used.

[78] See, e.g., Yoram Dinstein, The Conduct of Hostilities under the Law of International Armed Conflict (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 11 ( “Much of the Protocol may be regarded as declaratory of customary international law, or at least as non-controversial.”). See generally International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary International Humanitarian Law (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005).

[79] See the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, all of which entered into force on October 21, 1950.

[80] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rule 1, citing Protocol I, art. 48. According to ICRC, Commentary on the Additional Protocols, “The basic rule of protection and distinction is confirmed in this article. It is the foundation on which the codification of the laws and customs of war rests.” Ibid., p. 598.

[81] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rules 7 and 8, citing Protocol I, art. 52(2).

[82] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rule 10, citing Protocol I, art. 52(3).

[83] Under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC Statute), it is a war crime to intentionally direct attacks against civilian objects, except during the time they are military objectives. ICC Statute, art. 8(2)(b)(ii).

[84] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rules 11 and 12, citing Protocol I, art. 51.

[85] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rule 14, citing Protocol I, arts. 51(5)(b) and art. 57.

[86] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rule 15, citing Protocol I, art. 57(1).

[87] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rule 17, citing Protocol I, art. 57(2)(a)(2).

[88] See ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rule 16, citing Protocol I, art. 57(2)(a).

[89] See ICRC, Commentary on the Additional Protocols, pp. 681-82.

[90] UK Ministry of Defence, The Manual of the Law of Armed Conflict (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford: 2004), p. 55.

[91] Hague Regulations, art. 23(g).

[92] First Geneva Convention, art. 50; Second Geneva Convention, art. 51; Fourth Geneva Convention, art. 147.