Embattled

Retaliation against Sexual Assault Survivors in the US Military

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Protect Our Defenders (POD) for their considerable contribution to this report. In addition to providing general consultation during the initial stages and throughout the investigation process, POD supplied subject matter experts, helped identify survivors to be interviewed for the report, secured survivors’ consent, gave Human Rights Watch access to POD’s pro bono files and survivor database for survivors who had consented, and reviewed and contributed feedback on the final report and policy recommendations. We are grateful for their collaboration on this effort. This project could not have been done without their support.

Sara Darehshori, senior counsel in the US Program, and Meghan Rhoad, researcher in the Women’s Rights Division at Human Rights Watch, researched and wrote this report. Dr. Brian Root, a quantitative analyst at Human Rights Watch, analyzed the data and created the graphs in the “Scope of the Problem” section. This report was edited at Human Rights Watch by Alison Parker, director of the US Program; Liesl Gerntholtz, director of the Women’s Rights Division; James Ross, legal and policy director; Danielle Haas, senior editor; and Joseph Saunders, deputy program director. Portions of the report were also reviewed by Shantha Rau Barriga, director of the Disability Rights Division. Samantha Reiser, coordinator of the US Program, and Alexandra Kotowski, senior associate in the Women’s Rights Division, provided assistance with research and final preparation of the report, formatting, and footnotes. Layout and production were coordinated by Kathy Mills, publications specialist, Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, and Alexandra Kotowski.

A number of interns helped to research, organize, and check information for this report: Alex Simon-Fox, Phoebe Young, Margaret Weirich, Maya Kapelnikova, Wesley Erdelack, and Akhila Kolisetty.

Photographs were kindly provided by Mary F. Calvert.

Extremely generous pro bono legal assistance was provided by a team led by Claire Slack at McDermott, Will, & Emery LLP in Menlo Park, California. McDermott analyzed and coded all the Boards of Correction of Military Records on our behalf. In addition, we received invaluable pro bono assistance from Todd Toral and Jesse Medlong at DLA Piper LLP’s San Francisco office and Maya Watson at Bodman PLC in Detroit, Michigan, with our numerous records requests.

External reviews of portions of this report were conducted by Shannon Green, Elizabeth Hillman, and Tom Devine, among others.

We would also like to thank COL James McKee, Col Carol Joyce, CAPT Karen Fischer-Anderson, and Lt Col Andrea deCamara, heads of their respective Special Victim Counsel and Victims’ Legal Counsel programs for their cooperation and assistance with our research.

In addition, a number of veterans’ advocates and others went out of their way to assist us with our research, including Liz Luras, Monisha Rios, Michael and Geri Lynn Matthews, Patricia Lee Stotter, Lynn and Steve Newsom, Sandra Park, Susan Burke, Ray Toney, Rachel Natelson, Ruth Moore, Tia Christopher, Sandy Geschwind, and the staff of the Response Systems Panel, particularly Julie Carson and Meghan Tokash.

Finally, and most importantly, we are thankful to the service member survivors of sexual assault who shared their stories with us. This report would not have been possible without their commitment to ensuring that other victims in the US military will be able to seek justice without fear of retaliation.

Summary

Spat on. Deprived of food. Assailed with obscenities and insults—“whore,” “cum dumpster,” “slut,” “faggot,” “wildebeest.” Threatened with death by “friendly fire” during deployment. Demeaned. Demoted. Disciplined. Discharged for misconduct.

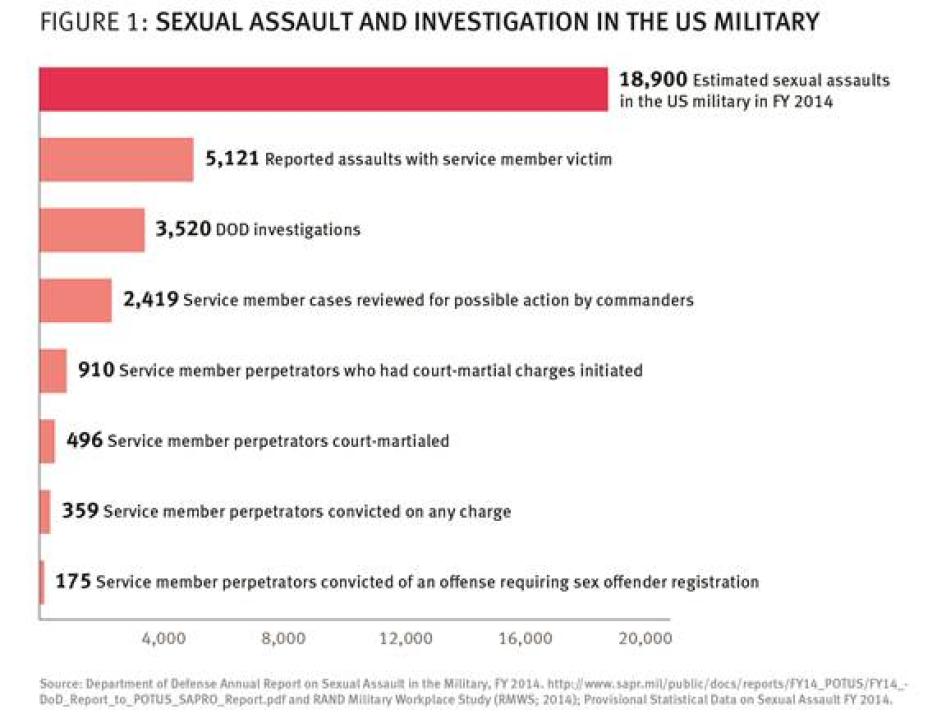

It is no secret that the US military has a sexual assault problem: the Department of Defense estimates that 18,900 US service members were sexually assaulted in fiscal year (FY) 2014.[1] But the slurs, sanctions, and scorn described above are not the punishments that soldiers and their superiors have meted out to those who have perpetrated sexual assault in the armed forces, but rather what happened to victims who reported their experiences.

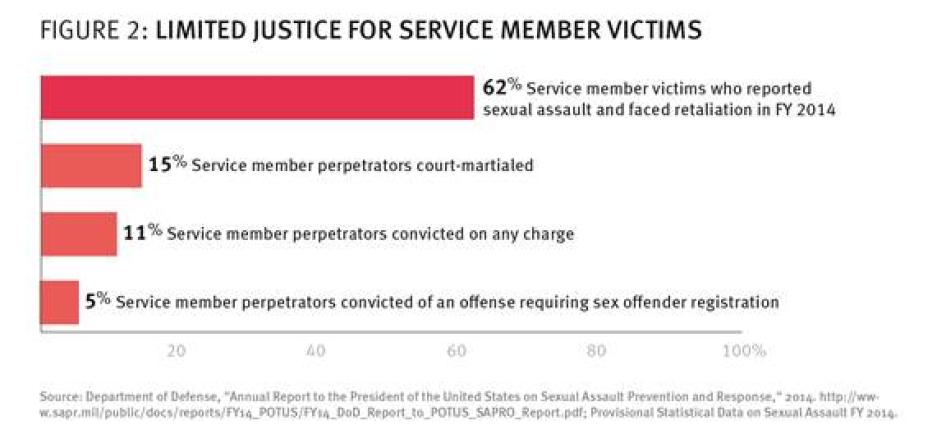

Military sexual assault survivors almost never see a remedy for these actions, for which virtually no one is held accountable. Military surveys indicate that most respondents—62 percent—who experienced unwanted sexual contact and reported it to a military authority faced retaliation as a result of reporting.[2] In other words, military service members who reported sexual assault were 12 times more likely to suffer retaliation for doing so than to see their offender, if also a service member, convicted for a sex offense. Just 5 percent (175 out of 3,261) of sexual assault cases in the Defense Department’s jurisdiction investigated with a reportable outcome in FY 2014 led to a sex offense conviction.[3]

It is estimated that only one in four victims reports sexual assault to military authorities. In surveys, service members consistently cite fear of retaliation from the perpetrator or the perpetrator’s friends, or concern about their careers, as reasons for not reporting.[4]

Such fears are well-founded. Although the military has undertaken significant and commendable reforms in how it handles sexual assault cases in recent years, it has not yet effectively addressed retaliation and fear of retaliation.

Survivors have little recourse if they experience retaliation and few of those who retaliate are held accountable. Human Rights Watch was unable to uncover more than two examples of even minor disciplinary action being taken against persons who retaliated against a survivor.

While reporting rates have improved dramatically in recent years, the positive trend will not continue if victims see that those who report their assaults experience retaliation and that no action is taken to address the problem. In other words, ending retaliation is critical to effectively addressing sexual assault in the US military.

Research Focus

Human Rights Watch undertook this investigation to examine reports of retaliation that these survivors faced: its forms, causes, perpetrators, and, perhaps most importantly, what recourse survivors had to stop it or to remedy related damage to their career.

We conducted 255 in-person and telephone interviews and examined documents produced by US government agencies in response to numerous public record requests, publicly available information, and performed data analysis. We spoke to more than 150 survivors of sexual assault. Twenty-two of the survivors interviewed were male, though this does not reflect the demographics of sexual assault victims in the US military. Because the services are disproportionately male, there are more male victims of unwanted sexual contact than female, though men report at much lower rates.[5] Given recent reforms in the military’s treatment of sexual assault, we focused our analysis on active duty survivor experiences from the last few years (FY 2012 and later) to ensure the report reflects the current context.

Retaliation as understood by the Department of Defense encompasses both professional and social retaliation. In its recent “Report to the President,” the department described retaliation as including “taking or threatening to take an adverse personnel action or withholding or threatening to withhold a favorable personnel action, with respect to a member of the Armed Forces because the member made a protected communication (e.g., filed a report of sexual assault).” It also recognizes that retaliation “includes social ostracism and such acts of maltreatment committed by peers of the victim or by other persons because the member made a protected communication.” In surveys on retaliation, the Defense Department has also asked survivors whether they have been punished for an infraction but these are not included in the department’s formal definition of retaliation.

Human Rights Watch investigated the above types of retaliation, as well as several additional issues that arose repeatedly in interviews as negative repercussions for survivors who reported or sought assistance with recovery from the sexual assault.

In particular, we documented the military’s punishment of victims for minor “collateral misconduct,” such as underage drinking or adultery, which only came to the attention of authorities because the victim came forward to report sexual assault. Fear of punishment for minor infractions is a major obstacle to reporting for many service members, and understandably so; even administrative punishment such as a written reprimand can impact promotion or the ability to stay in service during military downsizing.

We also documented the many barriers—from stigma to lack of confidentiality—that obstruct survivors’ access to the mental health care they may want or need to treat their trauma and maintain their readiness for military service. Because mental health records have been routinely disclosed during criminal proceedings and used against a victim, victims often have had to choose between seeking help or having their private medical records revealed. As a result, several victims’ lawyers told us they cautioned clients not to seek counseling if they were going to trial. Recent reforms to the Military Rules of Evidence may have addressed this issue, but their implementation needs to be monitored.

Retaliation

Many survivors told Human Rights Watch that they considered the aftermath of the sexual assault—bullying and isolation from peers or the damage done to their career as a result of reporting—worse than the assault itself. Survivors told Human Rights Watch that they felt they were viewed as “troublemakers” who brought negative attention to their unit. At the very moment that they needed support, survivors described peers turning on them due to loyalty to the perpetrator or fear that they would be shunned by association.

The ostracism and bullying went well beyond not being invited to parties. Service members described being threatened, harassed, and abused: one survivor sought safety in a hospital because colleagues told her she “better sleep light,” and disabled her car after she reported her assailant. Another was besieged with phone calls after members of her unit put notes on cars at the post exchange (the on-base store) saying “for a good time call” and her number. Another wrote that within six months of his report he had been “physically attacked twice and verbally belittled” by peers and non-commissioned officers.

On the professional side, many victims feel they face a choice between reporting their sexual assault and continuing their careers in the military. Those fears are borne out in the stories survivors shared with Human Rights Watch of careers that began with seemingly limitless potential—some stellar to the point of receiving national recognition—only to plummet in various ways following the service member’s report of a sexual assault. Service members across branches describe similar patterns of career problems after reporting their assault.

Some survivors told Human Rights Watch how their reporting of an assault seemed to precipitate a change in their work assignments from high-level military tasks like intelligence work to menial tasks like picking up garbage, or to tasks that took them away from their area of specialty. One Marine, with training in computers, said that after her assault she was transferred to an armory unit for four months where she had to work inside an enclosed and locked cage with five men cleaning and passing out weapons.

Survivors also told Human Rights Watch they saw their performance evaluations take a downward turn after reporting. One senior master sergeant reported being groped by a military lawyer—a Judge Advocate (JAG)—when she was a young airman and on her next evaluation she received a lower mark for “questionable handling of personnel matters.”

Relatedly, survivors said their command denied them important opportunities for training, deployments, and ultimately promotions. A high-achieving sergeant in the Air National Guard told Human Rights Watch that she was up for promotion when she reported a sexual assault that had occurred earlier in her career. Afterwards, a colleague told her a wing commander said, “Over my dead body will she get promoted now.” She lost her responsibility for training people and was demoted twice. “Despite all those awards, I got nothing,” she said.

Many survivors told Human Rights Watch that disciplinary action against them became a daily part of life after they reported. The military disciplinary system provides a spectrum of administrative options for commanders to ensure good order and discipline. These options also create ample opportunity for commanders to exercise their authority to retaliate against service members for reporting sexual assault. While some survivors who spoke with Human Rights Watch praised their commanders for the support they provided, many had the opposite experience.

At the less punitive end of the spectrum, survivors reported receiving formal letters of counseling (a notation of problematic behavior in the service member’s personnel records) for behavior that would normally be overlooked or, at most, dismissed with an oral warning. Survivors recalled getting even more serious letters of reprimand, for infractions like wearing the “wrong socks” or leaving dirty dishes in the sink.

Some survivors said it appeared their command looked for any excuse—such as one victim falling behind on a run while under medical treatment—to take more severe disciplinary action (non-judicial punishment). While not criminal, these actions can carry stiff penalties, such as reduction in rank, forfeiture of pay, confinement, or diminished rations for set periods of time, and remain on the service member’s permanent record.

In some cases, retaliation for reporting sexual assault led to the survivor being forced out of the military. Whether by choice or not, few of the survivors with whom we spoke who reported their assaults stayed (or plan to stay) in service beyond current enlistment requirements.

Impact of Punishment

Being punished by one’s peers or supervisors for reporting a violent sex crime or for seeking medical treatment would represent a grave injustice in any employment context; it would also potentially compound the trauma of a sexual assault. But the military is not any employment context. In fact, “employer” is a word that rarely comes up when service members speak about their relationship to the military. One former naval officer told Human Rights Watch:

Everyone is told from day one that the military is your family. We’ve got your back. You can trust these people. If you are sexually assaulted, it takes on an incestuous dynamic. It is that level of betrayal. Then it goes to your command—if the command handles it badly, that’s another level of betrayal. Every time the system fails, another layer of betrayal.

In addition to the betrayal, military retaliation is not limited to a 9-to-5 work day, and cannot be escaped with two weeks’ notice. Service members are not mere coworkers with their perpetrators and their friends, they live together. Especially for junior enlisted service members, the military controls every minute of their time and aspect of their lives. Many service members are bound by contracts to the military for fixed-year terms.

Getting out of those commitments because they are being tormented at work is not always possible. Quitting is not an option—indeed, it is a crime. In years past, survivors fearing further violence and retaliation have left duty stations seeking safety and found themselves later court-martialed and imprisoned for going AWOL (absent without leave). One Coast Guard trainee considered faking suicide because she saw no other way to get out of military service and away from the supervisor who was regularly harassing her—and who was also the person designated to receive complaints about sexual harassment.

Limited Protections

Addressing retaliation against military sexual assault survivors constitutes an international legal obligation of the US government. In joining the Convention against Torture, the United States committed to ensure that those who report torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment “are protected against all ill-treatment or intimidation as a consequence of his complaint or any evidence given.”[6] In 2014, the United Nations Committee against Torture, the expert body charged with monitoring compliance with the convention, reminded the US government of its obligation to ensure those protections for complainants reporting military sexual assault.[7]

In addition, international law affords victims the right to an effective remedy for sexual assault.[8] Recognizing the ways that retaliation can interfere with victims’ access to a remedy under human rights law, international best practices on the treatment of victims require that governments “take measures to minimize inconvenience to victims, protect their privacy, when necessary, and ensure their safety, as well as that of their families and witnesses on their behalf, from intimidation and retaliation.”[9] To ensure survivors’ ability to access a remedy, governments should take all appropriate measures to end retaliation.

Nevertheless, protections for service members who are sexually assaulted are limited under existing US law. Unlike civilians, longstanding Supreme Court precedent prohibits service members from suing the military for any injuries or harm “that arise out of or are in the course of activity incident to service.”[10] This includes violations of their constitutional rights.[11] Federal appeals courts have also barred uniformed personnel from bringing discrimination suits under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, the primary mechanism for holding employers accountable for inappropriate sexual conduct.

In its “Report to the President,” the Department of Defense identified nine avenues of recourse open to sexual assault survivors facing retaliation. Our research has shown that only three of the nine are viable options. Those three are:

- Seeking a military protective order;

- Requesting an expedited transfer; or

- Transfer for safety to another duty station.

These options are supportive or protective responses that remove the victim from the situation or protect them from harm. But they do not involve holding those responsible for the retaliation accountable. Furthermore, Human Rights Watch interviews suggest that while a transfer may offer some survivors a fresh start, others saw it as punitive or found that harassment and a reputation as a “troublemaker” followed them to other duty stations.

On the other hand, our research indicates that the six purported accountability mechanisms have not proven up to the task. These are: reporting to the commander; reporting to a commander in another chain of command; reporting to a Sexual Assault Response Coordinator at another installation; filing a Military Equal Opportunity (MEO) Complaint; reporting to the Department of Defense inspector general; and punishing retaliators for failing to obey orders.

These mechanisms are not utilized, are ineffective, poorly understood, hamstrung by jurisdictional limitations, not sufficiently independent of command structures, mistrusted because they lead to new incidents of retaliation—or all of the above. Further, little effort has been made to deter retaliation by holding wrongdoers accountable for their acts, despite a plethora of disciplinary options available to command.

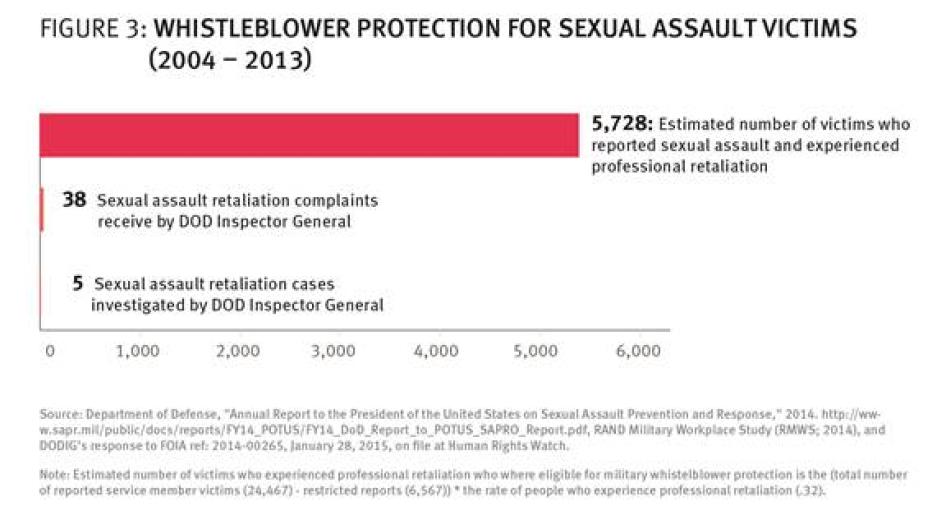

The Inspector General’s Office is the office designated in the US military to investigate complaints of professional retaliation. If a service member believes they have suffered negative personnel action after reporting a sexual assault or sexual harassment, they can make a complaint directly to the Department of Defense Inspector General (DODIG) or to their service Inspector General (IG) under the Military Whistleblower Protection Act.

However, although Defense Department data suggest that thousands of survivors have experienced the type of professional retaliation that would fall under the Military Whistleblower Protection Act, we have been unable to find cases in which a survivor who experienced retaliation was helped by that law.

According to documents Human Rights Watch obtained via public records requests, between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2013, DODIG received only 38 complaints from a victim of sexual assault alleging professional retaliation. It was unable to substantiate any of those complaints,[12] perhaps due to problems discussed in this report with inadequate investigations and the high burden of proof required for substantiation.

During the same period, the Defense Department reports receiving 17,900 unrestricted (non-confidential) complaints of sexual assault from service member victims. A 2014 military workplace and gender relations survey found that 32 percent of service members who reported sexual assault also said they subsequently faced professional retaliation, suggesting that well over 5,000 of the service members who filed complaints of sexual assault in the 2004-2013 period may have also experienced professional retaliation and could have sought protection under the Military Whistleblower Protection Act.

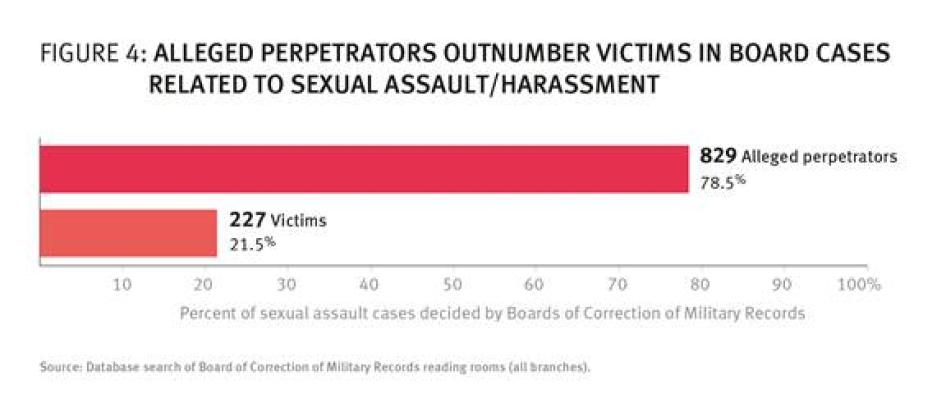

Even if an IG investigation were to substantiate a survivor’s claim, actually correcting any unjust negative mark in a service member’s military record involves an entirely different process and mechanism: the Boards for Correction of Military Records. In practice, record corrections almost never happen for sexual assault victims or for military whistleblowers generally. Of all military whistleblower complaints, less than 1 percent receive some form of relief from the records boards. Human Rights Watch analyzed records board decisions over an 18-year period and found just 66 cases in which sexual assault victims won full or partial correction of an injustice in their record.

At the same time, our analysis shows that alleged perpetrators of sexual assault sought and received corrections in their records from the Boards far more often than victims, even though victims are much more likely to experience administrative action that might require assistance from the Boards to correct. Other potential avenues for redress—such as the Military Equal Opportunity Program and an Article 138 complaint through a superior officer—also have shown no demonstrated ability to provide redress for victims of retaliation by peers or superiors.

Recent Efforts to Address Sexual Assault

While these findings paint a dismal picture of what awaits military sexual assault victims who choose to report, some recent reforms aimed at preventing and responding to retaliation provide important protections. In the wake of extensive media coverage and public attention to the issue of rape in the US military, Congress and the Department of Defense have made numerous reforms to the military justice system to protect victims’ rights in recent years. Over 200 provisions of law, secretarial initiatives, and independent recommendations have been undertaken within the last three years.

These include: not requiring military sexual assault survivors to report mental health counseling on security clearance applications; prohibiting retaliation under the military’s criminal code, the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ); establishing the expedited transfer program to allow survivors to transition swiftly out of toxic environments; and requiring heightened review of administrative discharges of sexual assault victims.

Human Rights Watch’s investigations found the recent creation of the Special Victim Counsel programs to provide attorneys to victims a singularly powerful reform. As the programs are new, many of our interviewees did not have the advantage of that service, but those who did reported that it made a significant difference to have their interests represented, not only in the criminal investigation and proceedings against their perpetrators, but in the negotiation of a range of matters with their commands, including retaliatory behavior by peers and supervisors.

Since the Report to the President in December 2014, the Defense Department has expanded its efforts to curb retaliation. Beginning in March 2015, military sexual assault case management group meetings chaired by commands at various levels have begun to regularly address retaliation. Plans are also in place to enhance skills and training for first-line supervisors to recognize retaliation. The Defense Department also plans to enhance its data collection on retaliation.

These reforms show promise, and likely have only begun to demonstrate their potential. However, real change needs further reforms to make remedial mechanisms more accessible and effective, and to ensure that those who commit or condone retaliation are held accountable. Without reforms targeted at those issues, retaliation is likely to continue unabated as surveys indicate it did between 2012 and 2014 despite efforts to address it.

***

We recognize that trauma resulting from sexual assault may negatively impact a survivor’s performance or lead to misconduct that the military is justified in addressing. Some survivors may be less competitive for promotion because they missed crucial aspects of their duties or training due to legal meetings or medical appointments. And what some survivors experience as retaliation, such as a transfer to a new duty station or work environment, may seem benign or even supportive to others if it removes them from a hostile environment. It may be hard for the military to find an appropriate position for someone who needs to move on short notice. The military also has particular battle-readiness needs and fitness for duty requirements that may make it less adaptable to meeting victims’ needs than most other institutions.

There is no “one size fits all” solution for victims.

Yet this investigation concludes that even in such situations, the US military’s response too often is unnecessarily punitive and lacking consideration of the victim’s mitigating circumstances.

For individual survivors, retaliation can cost them their careers and more, but their colleagues and superiors may be inured to their suffering. Lauren Morris, a Navy reservist who was raped while deployed as an intelligence specialist, described how casually those around her took the retaliation compared with what it meant to her:

[Retaliation] was not a game. It was my life. It was my military career, future job opportunities, what I wanted to study in college. It was who I was as a person. And it was a joke to them.[13]

Morris’ and others’ experiences of retaliation deter other victims from reporting sexual assault and renders the military an institution that is both a nightmare for victims and a haven for perpetrators.

This is not the result that the armed forces, the Department of Defense, Congress, or the US public wants. It is certainly not the result that US service members deserve. In order to address retaliation the government should fix what is not working and strengthen what is.

Human Rights Watch recommends that:

- Congress reform the Military Whistleblower Protection Act to afford service members the same level of protection as civilians.

- Congress establish a prohibition on criminal charges or disciplinary action against survivors for minor collateral misconduct that would not have come to the military’s attention but for the victim’s report of sexual assault.

- The Defense Department expand initiatives, like the Special Victim Counsel program, expedited transfers, and non-military options for mental health care, which give survivors the tools and control to direct their recovery and their future in the military.

- Systems and individuals in the armed forces that take retaliation seriously be rewarded, and those who commit or tolerate acts of retaliation be held to account.

Survivors of sexual assault in the US armed forces deserve nothing less.

Recommendations

To the United States Congress

- Strengthen the Military Whistleblower Protection Act.

- Alter burden of proof standard to be consistent with the federal Whistleblower Protection Act and best practices.

- Expand protection to prohibit retaliatory investigations, the failure by a superior to respond to retaliation committed by subordinates, and any other discriminatory action that creates a chilling effect on reporting sexual assault.

- Expand the protections to whistleblowers to include rights: to have Department of Defense Inspector General (DODIG) conduct the investigation; to counsel; to a hearing before the Boards of Correction of Military Records; to request disciplinary action against the party found to have retaliated; to have negative personnel action suspended during the investigation; and to recover reasonable attorney fees.

- Consistent with the proposed Legal Justice for Servicemembers Act of 2015, require the Boards of Correction and Inspector General (IG) to recommend disciplinary action for personnel responsible for retaliation.

- Expand procedural protections for complainants and streamline the process for whistleblowers to get relief.

- Make training in whistleblower protection rights mandatory for all service members.

- Apply Administrative Procedure Act standards to judicial review of military whistleblower cases.

- Prohibit disciplinary action or criminal charges against victims for minor crimes (including underage drinking, fraternization, and adultery) that only came to the military’s attention due to the victim’s report of sexual assault.

- Monitor use of Military Rule of Evidence 513 following its recent revision and consider further narrowing exceptions to the psychotherapist patient privilege.

- Require a court order for investigators or third parties to obtain victims’ mental health records.

To the Secretary of Defense

Regarding Special Victim Counsel (SVC) and Victims’ Legal Counsel (VLC)

- Improve outreach about SVCs so that survivors are more aware of the services they offer and have access to them before reporting to investigators.

- Require investigators to have victims speak with an SVC/VLC before waiving any right or beginning an investigative interview.

- Require the services to provide victims with SVC/VLC consultation prior to an administrative discharge.

- Strengthen capacity of SVCs to respond to retaliation in different forms and expand access to their services.

- Co-locate counseling and Sexual Assault Response Coordinators (SARCs)/ Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention (SHARPS) with legal services offices.

- Establish uniform practice and procedures concerning SVCs’ participation in military judicial proceedings, including timely disclosure requirements of pleadings. Ensure SVCs are available on all major bases and can meet with clients in person at least once.

Regarding Mental Health

- Improve access to civilian mental health care.

- Work closely with local rape crisis centers on training and outreach on base to ensure their services are accessible and known to service members.

- Expand the number of mental health providers trained to handle sexual assault cases and improve training to therapists to reinforce information about proper recordkeeping and disclosure.

- Reinforce mental health providers’ obligation to consult with patients and advise them of risks of disclosure before complying with any waivers to disclose medical records.

- Expand outreach about the availability of Military Sexual Trauma (MST) counseling to active service members at Department of Veterans Affairs Vet Centers.

- Co-locate behavioral health facilities in buildings with multiple functions to help preserve confidentiality of those who enter the facilities.

- Expand availability of appointments after working hours so service members can seek help while they are not on duty.

- Ensure that commanders communicate to front-line supervisors that service members should not face negative repercussions for absences due to medical appointments.

- Expand possibilities for voluntary in-patient treatment when appropriate and as an alternative to leaving the service for those who wish to remain in the military but may temporarily be incapable of performing their duties.

- Create Defense Department in-patient facilities to assist with trauma arising from sexual assault and ensure that they have sufficient capacity and specialized treatment for male survivors.

Other

- Provide training and intervention for junior enlisted personnel in supervisory positions about responding to sexual assault in their unit, the effects of trauma, and the appropriate response to peer retaliation.

- Monitor treatment of victims by their peers and immediate supervisors and collect data on incidents of retaliation.

- Aggressively investigate and respond to allegations of reprisal and publicly highlight measures taken against those responsible for retaliatory action.

- Allow survivors to defer a performance evaluation, promotion consideration, or skills test for a period of time if their ability to perform or duties have been impacted by issues relating to sexual assault; create an instruction for Performance or Promotion Review Boards on how to take into account a sexual assault in an evaluation when it has impacted the victim’s performance relative to their peers.

- Train broader leadership on the impact of trauma, counter-intuitive victim behaviors, and protection of those alleging sexual assault.

- Require commander consultation with SARCs/SHARPS or SVCs on how to address retaliation on a case-by-case basis as there is no “one size fits all” solution.

- Provide a mechanism for the Defense Department’s Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office (SAPRO) to receive and then enquire into generalized (non-case specific) information about problematic units or commands for the purpose of targeting remedial training and other efforts.

- More strictly enforce confidentiality of information on a restricted (confidential) sexual assault report.

- Recognize leaders who effectively respond to reprisals.

- Instruct commanders to consider favorably requests by victims to transfer housing when possible, particularly if they were assaulted there.

- For victims in areas of narrow specialties, consider the option of a career field change, if requested by a victim.

- Allow collateral duty Victim Advocates sufficient time and material support (such as access to cell phones or transportation) to perform their advocacy duties without negatively impacting their regular duties and include feedback from victims as part of their performance evaluations.

- Vary sexual assault trainings from standard power points to better engage audiences (i.e., employ more interactive trainings, workshops, theater).

- Allow victims who have made restricted reports to request expedited transfer through their SVC.

- Expand the requirement to provide a victim with a record of trial to include cases where the court martial resulted in an acquittal.

To Community Service Providers

- Allow service members to seek counseling on an anonymous and voluntary basis (consistent with obligations to ensure the service member is not a danger to themselves or others).

- Engage veterans (as staff or board members) to facilitate a relationship with the local base and assist with explaining military culture to civilian staff.

- Conduct active outreach on bases to ensure awareness of community services.

- Participate in training victim advocates and sexual assault training for service members on base.

- Extend operating hours to accommodate counseling sessions after working hours or on weekends.

- Provide training to mental health providers on proper documentation of cases including training on preparation of what should be included in medical records (symptoms, diagnosis, treatment plan) and what should be excluded (i.e. a play by play of events) as well as military mental health practices.

- Reinforce mental health providers’ obligation to consult patients and advise them of risks of disclosure before complying with any waiver to disclose medical records.

- Provide feedback to SAPRO on problem units or patterns of abuse apparent from information received (within the bounds of client confidentiality).

Download detailed recommendations to the Department of Defense » (PDF)

Methodology

This report is based primarily on more than 255 in-person and telephone interviews conducted between October 2013 and April 2015, as well as documents provided to Human Rights Watch in response to public record requests.

Interviews were conducted with 150 sexual assault survivors from all branches of the US Armed Forces, including the Coast Guard and National Guard. Research also benefitted from written accounts from an additional 52 survivors. The issues documented in this report arose consistently in our interviews with survivors across the military services. However, we did not attempt to conduct a representative sampling of military sexual assault survivors. This is not a scientific study and this report’s findings cannot be generalized to the military population as a whole. Given the sensitive nature of the topic and confidentiality concerns expressed by many interviewees, all survivors’ names and other identifying details have been withheld. All names of survivors are randomly assigned pseudonyms.

Some survivors also provided documentation in support of their interviews. Since this report covers retaliation against victims after reporting a sexual assault, and in order to minimize further trauma, Human Rights Watch did not focus our interviews or investigations on the underlying assault. Because the Department of Defense has undertaken significant changes in its handling of sexual assault cases since FY 2012,[14] for descriptions of retaliation we relied primarily on the accounts of 75 survivors who are either active service members or who left the military in mid-2011 or later. The 75 accounts came from 17 written submissions and 58 interviews. Of the 58 interviewees, 27 are currently serving or left service in 2015; 11 left in 2014; 11 left in 2013; 5 left in 2012; and 4 left in 2011. However, some of the assaults occurred prior to changes in the military’s handling of sexual assault cases, but the retaliation continued to impact the survivor’s career during the timeframe of this report.

Notably, many of the survivors we interviewed (including active service members) were assaulted prior to the implementation of the Special Victim Counsel (SVC) or Victims’ Legal Counsel (VLC) programs in the different branches. In some cases, lawyers for victims were able to play a positive role in helping address problems victims faced after reporting and those are noted. One of our recommendations is to expand the ability of SVCs and VLCs to assist victims suffering from retaliatory treatment.

Fifty-eight of the 76 survivors were interviewed in person or by telephone and 18 provided or published written accounts. Accounts from older cases were used only on a few issues about which limited accounts were available, such as victims who had complained about retaliation to the Inspector General. When older cases are referenced, they are noted in the text.

Also, 22 of the 150 survivors interviewed were male, and 6 of them were in the timeframe relevant for this report. The disproportionate number of women interviewed does not reflect the demographics of sexual assault victims in the US military. Because the services are disproportionately male, there are more male victims of unwanted sexual contact than female, though men report at much lower rates.[15]

Survivors were located using several methods: Human Rights Watch launched a Facebook page in October 2013 describing the project and providing a point of contact for those willing to be interviewed. A number of survivors we interviewed posted information about our research on private Military Sexual Trauma support pages or referred other survivors to us. In addition, nongovernmental groups who support survivors, including Protect Our Defenders (POD), Service Women’s Action Network (SWAN), and the Military Rape Crisis Center, referred victims to us and/or, with the survivor’s consent, provided their written accounts of their experiences. We also reviewed audio interviews done by StoryCorps as a part of its Veterans Listening Project and in-depth statements included in the “Fort Hood Report,” a joint project by Iraq Veterans Against the War, Civilian-Soldier Alliance and Under the Hood Café and Outreach Center, and the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School. On October 10, 2014, Human Rights Watch placed a print ad in Stars and Stripes newspaper.[16] A similar online ad ran on Military Times websites intermittently between October 6 and October 19, 2014. Special Victim Counsel and Victims’ Legal Counsel also referred clients to us.

In addition to interviews with survivors, Human Rights Watch conducted over 100 interviews with: experts in military law, current and former uniformed and civilian victim advocates, experts in military response to sexual trauma, military law practitioners, members of nongovernmental organizations that work with or advocate on behalf of service members, service members who are not victims, parents of veterans, Special Victim Counsel and Victims’ Legal Counsel, members of the Department of Defense Inspector General’s office, Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Coordinators, Sexual Harassment and Assault Response Program personnel, Judge Advocates, rape crisis center personnel from four rape crisis centers located near military bases, trauma counselors, Vet Center staff, and five members of the Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office at the Department of Defense (SAPRO). We also visited five Vet Centers across the country.

Most interviews were conducted individually and in private. Group interviews were conducted with Navy Victims’ Legal Counsel and Air Force Special Victim Counsel (including their Sexual Assault Prevention and Response (SAPR) policy advisor), members of the Department of Defense Inspector General’s office whistleblower reprisal unit, SAPRO, staff from two rape crisis centers, and one legal services organization. One survivor had her lawyer on the line for a telephone interview; another survivor, who was interviewed multiple times, had a counselor with her for one of her interviews. No incentive or remuneration was offered to interviewees.

In addition to interviews, we submitted document requests under the US Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) to the Offices of the Inspector General for the Department of Defense, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, Air Force, and Army; Boards of Correction of Military Records for the Army, Air Force, and Coast Guard and the Board of Correction of Naval Records; the Office of the Secretary of Defense and Joint Staff; the Army National Guard; the Air National Guard; and the Departments of the Air Force, Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard.[17]

At time of writing, Human Rights Watch received responses from all the Inspectors General and Boards of Correction of Military Records. With the exception of the Army and Air Force, which provided a limited number of documents and data, neither the services nor the Defense Department provided substantive responses to our requests by the time of publication.

As part of our research, we also reviewed extensive publicly available information about military sexual assault including, but not limited to, reports of the Response Systems Panel and the Judicial Proceedings Panel, the responses provided by the branches to the Panel’s requests for information and testimony before the panels, annual reports by the Department of Defense SAPRO, Workplace and Gender Relations Surveys, Department of Defense Inspector General semiannual reports to Congress, Government Accountability Office reports, publications by experts on psychological disorders and administrative and whistleblower law, congressional testimony by military officers and victims, complaints, military sexual assault training materials, Department of Defense Instructions, and nongovernmental and Task Force reports on sexual assault in the military.

In addition, on behalf of Human Rights Watch, the law firm of McDermott, Will & Emery downloaded and analyzed all Boards of Correction cases on the Department of Defense reading room website. The following search terms were used: sex*, sexual w/2 assault, sexual w/2 violence, rape, sexual w/2 misconduct, sexual w/2 harassment, sexual w/2 explicit, inappropriate contact, sexual w/2 abuse, sexual w/2 trauma, sodom*, oral w/2 sex, breast*, buttock*, genital*, anal, whistleblower, whistle w/3 blower, retaliate*, indecent, and rape*. The search resulted in 5,507 cases, of which 539 were duplicates. The remaining 4,968 cases were coded and analyzed for this report.

On April 22 and 23, 2015, Human Rights Watch provided SAPRO and the Department of Defense Inspector General with a summary of the findings of this report and gave them two weeks to respond. The SAPRO response is reflected in this report. We did not receive a response from the Department of Defense Inspector General.

A note on terminology:

Many survivors’ groups, support service organizations, and others working on sexual violence strongly prefer the term “survivor” to “victim.” “Survivor” implies greater empowerment, agency, and resilience, and many individuals do not want to be labeled solely as “victims.” This is often important to their healing process and sense of identity. That said, some individuals feel “victim” better conveys their experience of having been the target of violent crime. In recognition of these differing views, this report uses both terms.

Throughout the report, we reference survivors’ most senior rank while in service, though they may have left service by the time of our interview or prior to publication of this report.

“Retaliation” is used in this report to include adverse actions taken both by peers (social retaliation) and by the chain of command (professional retaliation) against persons who have reported a criminal offense (sexual assault).[18] The National Defense Authorization Act defines retaliation as “(a) taking or threatening to take an adverse personnel action, or withholding or threatening to withhold a favorable personnel action, with respect to a member of the Armed Forces because the member reported a criminal offense; (b) ostracism and such act of maltreatment, as designated by the Secretary of Defense, committed by peers of a member of the Armed Forces or by other persons because the member reported a criminal offense.”[19] Professional retaliation is also referred to as a “reprisal” and is typically handled by the Inspector General. It includes a range of actions such as transfer or reassignment, disciplinary action, poor performance evaluations, and change in a work assignment inconsistent with the military member’s grade. In this report, Human Rights Watch uses the term “retaliation” for all such adverse actions, including those referred to as “reprisals.”

Military service regulations further define the terms “ostracism” and “maltreatment” referenced in (b) above as requiring “the intent to discourage someone from reporting a criminal offense or otherwise discourage the due administration of justice.” Ostracism includes insults or bullying, exclusion from social acceptance or friendship because the victim reported a crime. Maltreatment refers to treatment by peers or by others that, when viewed objectively under all the circumstances, is abusive or otherwise unnecessary for any lawful purpose and that results (or reasonably could have resulted) in physical or mental harm or suffering.[20] Human Rights Watch used the term “ostracism” and “maltreatment” in their ordinary senses without inferring the underlying intent of the person doing the retaliation. This report examines forms of retaliation that do not necessarily align with actionable offenses that meet the elements of proof required for a charge of retaliation under military law.

This report also discusses other adverse consequences of reporting a sexual assault, such as punishment for minor misconduct that came to light as a result of reporting, though the military does not consider that retaliation.

Finally, we note that within the military system, victims may choose to report sexual assault in one of two ways: “restricted” or “unrestricted.” An unrestricted report is a non-confidential disclosure of a sexual assault to military authorities that leads to an investigation. A “restricted” report allows victims to report an assault to specified officials confidentially enabling them to access support or health care without initiating a criminal investigation. All survivors cited in this report made unrestricted reports.

Other military terminology and abbreviations are set out in the glossary at the end of the report. Common abbreviations will be spelled out in the first use of each chapter.

I. Retaliation in the Military

Everyone has the same fear, what happens to the person who reports. We are dispensable.

—Former Airman Torres, November 2013

I knew when I reported my career would be over. Based on past experience, I knew what would happen.

—Petty Officer First Class Cox, November 2013

There is a right to a remedy for all victims of sexual assault. Since retaliation often interferes with survivors’ ability to access a remedy, governments should take all appropriate measures to end retaliation. Recognizing the ways that retaliation can interfere with victims’ access to a remedy under human rights law, international best practices on the treatment of victims require that governments “take measures to minimize inconvenience to victims, protect their privacy, when necessary, and ensure their safety, as well as that of their families and witnesses on their behalf, from intimidation and retaliation.”[21]

Survivors recounted suffering a range of negative actions after reporting sexual assault or harassment, both professional and social. Many considered the aftermath of the assault—bullying and isolation from peers or the damage done to their career as a result of reporting—worse than the assault itself.

Human Rights Watch has concluded that these experiences constitute harmful retaliation consistent with the definition provided in the National Defense Authorization Act. Even if some of the acts were not intended as retaliation, many occurred because the service member reported a sexual assault. In addition, the victim’s beliefs about the incident and, more importantly, their beliefs about the military’s response has a long lasting impact.[22]

Lawyers who worked with victims said they would not report an assault after what they had seen: “I would never report unless I was a virgin coming out of Bible study with no mental health history and it was videotaped, because there will be negative consequences,” one said.[23]An experienced Air Force sex crimes prosecutor said: “I would never report. I was a prosecutor for eight years. No doubt. There is no way.”[24]

Scope of Problem

Service members consistently cite fear of retaliation or negative impact on their careers as major reasons for their unwillingness to report sexual assaults.[25] The Department of Defense estimates one in four service members who experienced sexual assault reported their assault to military authorities in 2013.[26] This number is a significant improvement over the estimated one in ten who reported the previous year,[27] though still lower than the military would like.

In a 2012 study, nearly half (47 percent) of female service members who did not report a sexual assault indicated one reason they did not do so is because they were afraid the perpetrator or his supporters would retaliate against them.[28] The same percentage indicated they did not report because they feared they would be labeled a “troublemaker.” More than a quarter (28 percent) feared they would receive poor performance evaluations, and 23 percent feared they would be punished for other infractions (such as underage drinking) if they reported. The 2014 RAND Military Workplace Study also indicates that concern about retaliation is a significant reason for not reporting an assault, though the figure is lower (15 percent).[29] Unfortunately, these fears are well-grounded as retaliation is pervasive.

According to a 2014 Department of Defense survey conducted by RAND Corporation, 62 percent of active service members who reported sexual assault to a military authority in the past year indicated they experienced retaliation as a result of reporting.[30] The survey defined retaliation to include professional retaliation (such as adverse personnel action), social retaliation (ostracism or maltreatment by peers or others) and administrative action or punishments. Because only active service members participate in the survey, service members who left the military—either voluntarily or involuntarily—after reporting a sexual assault are not included, so the actual rate of retaliation may well be higher.

The military conducts workplace and gender relations surveys every two years. The 2014 RAND survey shows that reported rates of retaliation have not changed since the last workplace survey in 2012, despite aggressive efforts by the military to reform its handling of sexual assault cases, including efforts to address retaliation.

In the 2014 survey, more than half the victims who made a report (53 percent) indicated experiencing social retaliation; 32 percent reported professional retaliation; 35 percent indicated experiencing administrative action (such as a reprimand);[31] and 11 percent reported being punished for an infraction (such as underage drinking). In a separate 2014 Defense Department Survivor Experience Survey, 40 percent of victims who made an unrestricted report of sexual assault reported experiencing professional retaliation, 59 percent experienced social retaliation, and one-third experienced both.[32]

A little retaliation can have enormous impact. The negative experiences of those who report greatly influence other survivors who consider how others have been treated when they make their own decisions about reporting: in the 2012 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey, 43 percent of those who chose not to report a sexual assault indicated that one reason they did not do so is because they heard about the negative experiences of other victims who did report.

Many survivors we interviewed, some of whom did not initially report their assault, said they did not want to report because they had seen what happened to others. As one said, “I know how it works in the military. If you report, you are out [of the military].”[33] One Marine who was ostracized after reporting walked in on her roommate being violently gang-raped. When she asked her roommate if she would report the assault, her roommate said that she would not report because “I don’t want to end up like you.”[34] When a trainee turned her drill sergeant in for sexual misconduct in 2012, she experienced such intense abuse in retaliation that she later discovered his other victims made a pact never to reveal what he had done to them.[35]

The significant strides the military has recently made in improving reporting rates will be erased if victims see that others who report experience retaliation, and that the military does not respond to it effectively.

While most survivors surveyed report experiencing retaliation, few will see their perpetrator tried and punished for a sex offense, as is true generally for these offenses in both the military and civilian contexts. According to the December 2014 Report to the President on Sexual Assault in the Military, in FY 2014, of the 3,261 cases within the Defense Department’s jurisdiction that had outcomes to report,[36] 910 (28 percent) had sex offense charges preferred (initiating the court-martial process); 496 (15 percent) cases proceeded to trial; and 175 (5.4 percent) were convicted of a sex offense.[37]

Thus for a victim deciding whether or not to make an unrestricted report, the risk is 12 times greater that the service member will experience retaliation as a result of their report than that the service member will see the offender (if a service member) convicted for a sex offense after a court martial.[38]

Below is a description of the range of experiences reported by survivors following their reports of sexual assault.

Threats and Violence after Reporting Sexual Violence and Harassment

While social isolation can be devastating on its own, interviewees also reported peer retaliation of a more aggressive nature, up to and including physical violence.

Roy Carter, an Army survivor who provided a written account to Human Rights Watch, reported a sexual assault by a male soldier from another platoon in 2012 only to find his safety further threatened:

Within 6 months I had been physically attacked twice and verbally belittled by no less than six senior NCOs [Non-Commissioned Officers] as well as my entire platoon of peers. It wasn't until I started drinking so heavily and failing at physical fitness that my Chief then finally found me a real counselor almost a year after being there. By then a certain Sergeant in my platoon had told me he would kill me if we ever went to Afghanistan because "friendly fire is a tragic accident that happens." I started carrying a knife for protection from people in my own unit. After I had been there for a year, someone tried to knife me in a bar and kept screaming "DIE FAGGOT, DIE" and that was when I told my Captain that I wanted a discharge before I ended up dead on the evening news which would be bad for him too.[39]

Others also reported threats:

- An Air Force survivor reported being called a “bitch” and being told “You got what you deserved.” Colleagues were angry at her for getting her assailant in trouble and “ruining his career.” She was told she “better sleep light.” Her car was tampered with so she had to walk everywhere. She stayed in a hospital overnight because she felt that nowhere else was safe. Ultimately she was given a transfer, but nothing happened to the people who threatened and harassed her.[40]

- A Marine reported that in 2014 after the case against her perpetrators was closed with them only being punished for alcohol violations, she began getting threatening anonymous text messages and her car was vandalized. On Facebook, her picture was posted on a webpage frequented by Marines with her name, calling her a “wildebeest,” and saying she needed to be silenced “before she lied about another rape.” She was called a “cum dumpster” and someone posted “find her, tag her, haze her, make her life a living hell.” She stopped going to the chow hall (dining facilities) out of fear. [41]

- A Marine Corps VLC told us his client was harassed and viewed as a “problem child.” When she went to a club with a friend, she was confronted by another Marine who told her friend, “Don’t sleep with [her] or she will call ‘rape.’” He cursed and threatened her, and said “If you sleep with anyone in this unit, we will gang up on you and burn you.” The VLC said he was concerned if he raised the issue with her command she would face more retaliation.[42]

Social Retaliation

Isolation and bullying by peers constituted one of the most common and insidious forms of retaliation described in interviews. Why peers appear to retaliate more often against the victims than the perpetrators of assaults is a complex question. As the Response Systems to Adult Sexual Assault Crime Panel found:

A sexual assault allegation involving members of the same military unit may divide loyalties among a close-knit group of people who should be working toward a common goal. Some unit service members may seek to silence the victim’s sexual assault allegation or retaliate against him or her to protect unit cohesion and keep the unit ‘whole.’[43]

Possibly for that reason, leadership often did not respond to survivors’ complaints and sometimes even participated in the retaliation. As a senior master sergeant said, “The shunning spanned the ranks. Peers, supervisors, officers, and enlisted. If you made waves, rocked the boat, you were an issue and some[one who] threatened mission success and accomplishment.”[44]

Many survivors who spoke with Human Rights Watch felt they were viewed as troublemakers who had brought negative attention to the unit. As Lisa Cox, a Navy petty officer, said, “My community is very small and many of my peers, subordinates, and seniors are aware of what happened to me. Instead of their support, I have been marked as someone to stay away from, a trouble maker, snitch and improper words I cannot type out.”[45]

Some pointed to the popularity or professional standing of the perpetrator as a reason they were shunned or bullied. In addition, military sexual assault victims confront many of the same victim-blaming attitudes prevalent in society at large—finding their credibility assailed by inflated perceptions about the rate of false reporting, criticism of their behavior before and after the assault, and antiquated, damaging beliefs about what constitutes “real rape.”

Survivors told Human Rights Watch about the acute trauma caused by having the people who were supposed to defend their lives in battle turn on them at the very moment they most needed support. As Senior Airman Bridges, who reported sexual harassment and assault, said, “They are supposed to be your family. When sexual assault happens, you’re no longer family.”[46]

The severity of peer retaliation varied across our interviews. Some survivors reported being frozen out by former friends and colleagues. Senior Airman Bridges said that being friends with her was seen as a “career-ender” after a commander made comments about her and her complaints on a conference call.[47]

Supervisors often dismissed concerns that victims raised about social ostracism. Seaman Collins said when she repeatedly raised concerns about the snickering and ostracism by her peers to her chain of command in the Navy she was told to “suck it up” and to “grow up” and “ignore it.”[48] A Naval petty officer told Human Rights Watch that after she was assaulted by a cook halfway through a deployment in 2011, her assailant’s colleagues harassed her and as a result she could not eat in the mess hall. Despite complaining to the chain of command several times, she said that nothing was done. For seven months while on deployment, she ended up buying her own food when she was in ports and “living off cans of tuna.”[49]

Fireman Martinez said she was assaulted by her supervisor during her first Coast Guard deployment in the fall of 2012. After an investigation was initiated, she was shunned by her peers. No one would sit with her while she ate. Others said they heard she was getting in trouble for sexually assaulting the perpetrator and his friends. People would look at her and turn away. Her peers knew details about her case but she was forbidden to talk about it and could not defend herself. Fireman Martinez said she felt her command let her down and described that time period as “a shit show.”[50]

Survivors also described situations in which the command appeared to encourage the peer alienation of the survivor. Several service members reported that their isolation was a result of instructions by commanders to their peers not to talk to them. One Marine Corps Judge Advocate General suggested that this instruction may be a mistakenly broad interpretation by junior leaders of general guidance requiring people not to talk with a victim about an ongoing investigation.[51] Regardless of the reason why such instructions are given, the resulting isolation for the victim can be devastating. Survivors told Human Rights Watch of the following experiences:[52]

- Army Specialist Parker said she felt targeted, isolated, and harassed after reporting her assault. Her close friends, people she considered her “brothers and sisters,” were ordered not to talk to her. One friend told her that the platoon sergeant told them not to talk to her, and if they did “they would face charges under the [Uniform Code of Military Justice].” SPC Parker said, “Sexual assault is not what messes you up. It is the reprisals, the hazing. I could recover from the assault but nothing is done for the retaliation.”[53]

- A lance corporal said her friends were told they would get “NJP’d” (non-judicial punishment) if they hung out with her. “I was alone all the way until the end.” She was discharged in June 2012 after being charged with “destruction of government property” for hurting herself after attempting suicide.[54]

- A Marine said that immediately after reporting in 2013, she was told not to talk about the case by Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) investigators. Meanwhile, the perpetrators were spreading rumors that she was a “lying whore.” People would stand outside her room and say her name really loudly then whisper “whore.” [55]

- An SVC said that when her client deployed after reporting a sexual assault in 2015, a higher-ranking person told the men in the client’s unit about the report, called her a “walking SARC [Sexual Assault Response Coordinator] complaint,” and advised them to stay away from her to avoid being falsely accused of sexual assault.[56]

Professional Retaliation

Many rape victims feel they face a choice between reporting their sexual assault or continuing their career in the military. Professional retaliation takes various forms including: poor performance evaluations, lost promotions or opportunities to train, loss of awards, lost privileges, demotions, a change in job duties, disciplinary actions, punitive mental health referrals, and administrative discharge.

Many interviewees told us that the negative turn in their professional careers did not correspond to any change in their work performance. It should be noted, however, that some survivors’ performance may well suffer following a trauma and other negative repercussions may flow from missing work to participate in judicial proceedings or seek counseling or medical treatment.

This can create significant challenges for keeping a service member on a chosen career path. However, the failure to address adequately these challenges leads to victims believing they are being punished for reporting sexual violence and fosters the perception that coming forward is a “huge career-ender.”[57] It also results in loss of good soldiers.

Poor Work Assignments

Survivors reported receiving poor work assignments after reporting sexual assault or harassment. In some cases the assignments were considered undesirable because they involved demeaning tasks, such as picking up garbage. In others, the assignments took the survivors out of their area of specialty, putting them at a disadvantage for promotions.

In some cases this was done to remove victims from a hostile work environment and was a positive move for survivors. Others, however, considered the assignments to be deliberately demeaning and intended to punish them for reporting sexual violence or harassment. It may understandably be difficult for the military to find a suitable temporary position for someone in their specialty on short notice and “fill-in” duties may seem demeaning even when they are not intended to be so.[58] However, being put in a position outside of their specialty for an extended period took some survivors off their career paths and was deeply demoralizing. The following are experiences survivors shared with Human Rights Watch:[59]

- A petty officer reported being assigned to pick up garbage after reporting her rape. She said there were three other women assigned to pick up trash on the base with her in 2013, all of whom had reported assaults, though garbage duty is usually reserved for those on restricted duty.[60] She said “It was like we got in trouble for reporting.”[61]

- One lance corporal who had been trained to fix computers was transferred to the armory unit after reporting a sexual assault in 2014. There she was enclosed in a locked cage with five men for over four months, cleaning and passing out weapons. She had little to do to occupy her time and was stressed being alone in that position. By the time she was reassigned she felt she had “no idea what [she] was doing anymore because [she] had been out of it for too long.” She was also assigned to fix equipment she had not been trained on, negatively impacting her performance. Out of her two-and-a-half years in the Marines, she spent less than six months working in the job she was supposed to do. She was not recommended for promotion.[62]

- After Master Sergeant Davis reported sexual assault, he was removed from his position in command and control and assigned to office duties inconsistent with his rank, including cleaning out office closets. Ultimately he was reassigned to “base beautification” and was made to pick up trash in his uniform and an orange vest. It was winter so he performed this task in the snow and ice with a broken foot and a necrotic hip that meant he needed crutches. He also had to report to an airman of significantly lower rank. Because this assignment was normally reserved for airmen who had been in trouble, it was especially shameful to be seen on base in this position.[63]

- After reporting her assault in 2012, Fireman Martinez was asked to leave her department and was reassigned to operations. Since she did not have clearance yet, she was not allowed into another department, so she spent her days in her berthing (assigned sleeping place on the ship). Later, her advanced training was delayed pending the outcome of the investigation.[64]

- After telling her squad leader about her assault and being told “not to be talking shit about” her assailant who was a senior NCO during a deployment, a corporal said she started getting put on “BS details, mandated full battle rattle [full combat gear] PT [physical training] twice a day, and many times got put on Guard Duty that was generally reserved for someone on a profile that couldn’t go on mission. Not me, as soon as I got off overnight duty, I had a full day ahead of me and did that repeatedly until I gave up trying to pursue it … they won.” She medically retired from the Army in 2012.[65]

Lost Potential for Career Advancement

For too many service members reporting sexual assault ultimately derails or even ends promising military careers, including through unwarranted poor performance evaluations and the revocation of important opportunities for training, deployments, and ultimately promotions.

Annie Moore joined the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) in 2003 at the age of 18 and was commissioned in 2007. She made the rank of army captain in 2011 and deployed to Kuwait where she served as a company commander. She told Human Rights Watch that there she faced an ongoing barrage of inappropriate sexual comments from her command sergeant major. After raising the problem up the chain of command, she saw a dramatic change in the characterization of her performance by the command, a number of whom had connections to the perpetrator. “Suddenly I was the worst commander ever,” she told Human Rights Watch. “I got two mediocre evals [evaluations] that didn’t reflect what I had done.”[66]

Despite doggedly pursuing both the original harassment complaint and subsequent communications with the base inspector general about retaliation, Captain Moore was unsuccessful in her efforts to see anyone held accountable. When she changed duty stations in 2014, she hoped to make a fresh start in a new location, but was informed within her first month by another officer that the brigade commander from Kuwait had spoken to her new brigade commander. Captain Moore told Human Rights Watch:

When I took command, the commander asked me to do 18 months. After I was aware that the [brigade] commanders had talked, I was informed that I was being relieved of my command. No reason was given. The only time you’re relieved or asked to move early is when you have done a poor job. But I have no counselling statement [admonition] on record—there’s nothing to substantiate the negative or mediocre OERs [evaluations] I received.[67]

Others also told Human Rights Watch that they had lost opportunities that seriously damaged their military careers.[68]

- After reporting a sexual assault in late 2013, Senior Airman Robinson had her weapon taken from her because she was considered “emotional” because she cried during a meeting discussing her concerns about living directly across from her perpetrator. As a military police officer, she was unable to do her job without a weapon. During the investigation, Robinson received her “dream deployment” and was scheduled to leave before the case was concluded. However, she was unable to deploy without her arms. Since her commander told her she would get her arms back when the case was over, Robinson decided to withdraw her participation in the case. However, her squadron commander told her she was “unable to get off the train” so she could not get her arms back and deploy.[69]

- Technical Sergeant Phillips had a successful career in the Air National Guard, earning recognition nationally for her work designing training programs and awards for extra work she had done. She was up for a promotion in 2010 when she reported an assault by her supervisor that occurred earlier in her career. After the report, she was moved to a different area and her chances for a promotion evaporated. A colleague told her she overheard her wing commander say, “Over my dead body will she get promoted now.” Phillips lost her responsibility for training people and was demoted twice after her report. She said, “Despite all those awards, I got nothing.” She retired in April 2013.[70]

- An Air Force SARC told of a victim who was not allowed to deploy after reporting her assault—a “flyer who could not fly.” Her career stalled while her assailant was able to deploy. He was promoted during the investigation, though after his conviction he lost his stripes.[71]

Survivors also report being denied medals or recognition that would be expected in ordinary circumstances.[72] Many survivors we spoke with said it was not only demoralizing to be denied their medals, it also sent a negative signal to the promotion board, and ultimately was another marker that could lead to the end of a military career.

- An Army captain who reported a sexual assault in 2010 was scheduled to change her command after two years in her post. After the date for the change of command ceremony was set and invitations sent out, the brigade commander scheduled a brigade-wide training for the same day. She asked if she should change the ceremony date since the entire brigade usually attends the ceremony. Her request was denied and she had a barebones ceremony with just her unit. At the ceremony, despite excellent reviews, she did not receive any award. “If you don’t get the award, it is an indicator to the promotion board that something is wrong. That was the start of the end of my career. Up until then, I was always exceptional, a top performer. I trained others, I was always the top female.”[73]

- Senior Airman Hall reported her assault by her boyfriend, another airman, in 2014. When she next changed duty stations she was declined for a “Permanent Change of Station” medal though she said she had a good conduct medal, no paperwork and was one of few in her shop who never got in trouble. Because the medal counts as a point towards her next promotion, losing it could make her less competitive to move ahead. Through her SVC she has appealed.[74]

- After a National Guard lieutenant colonel reported her sexual assault in 2012, a nomination for an award for meritorious service was withdrawn (even though it is traditionally given to all battalion commanders).[75]

Other survivors also felt reporting their assaults directly impacted their performance evaluations. A number of factors linked to the assaults could lead to poor performance evaluations. For example, performance may be negatively affected by trauma; training or assignments may be interrupted to accommodate legal appointments or healthcare needs; and deployments or other opportunities for advancement may be missed. One victim’s lawyer said his client was not progressing in her career because she was “put in a position where she was doing nothing, and her performance report will show she is not progressing in her career.”[76] As one Army officer said, the effect can be subtle. A lot of unrated time due to involvement in an investigation can impact performance reports.[77]

Because promotions are competitive and high scores on evaluations are common, even one bad evaluation can render someone un-promotable and mark the beginning of the end of a career. However, there is currently no procedure for consideration of how evaluations may be impacted by the aftermath of an assault, though one branch is reportedly considering allowing victims to postpone evaluations.[78] The following are examples of survivors who told Human Rights Watch of instances in which they believed they were unfairly evaluated:[79]

- Petty Officer Bouvier said she had always got the highest marks until she reported her assault. She went from being an “excellent performance” sailor to a “severe problems” sailor. She was constantly told by people to “get over it.” She told Human Rights Watch that she had to sign the evaluation or she would have been punished for disobeying a direct order. She was discharged in 2013.[80]