The ruling Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) consolidated political control with a striking 99.6 percent victory in the May 2010 parliamentary elections. The polls were peaceful, but were preceded by months of intimidation of opposition party supporters and an extensive government campaign aimed at increasing support for the ruling party, including by reserving access to government services and resources to ruling party members.

Although the government released prominent opposition leader Birtukan Midekssa from her most recent two-year stint in detention in October 2010, hundreds of other political prisoners remain in jail and at risk of torture and ill-treatment. The government's crackdown on independent civil society and media did not diminish by year's end, dashing hopes that political repression would ease following the May polls.

The 2010 Elections

Although the sweeping margin of the 2010 victory came as a surprise to many observers, the ruling party's win was predictable and echoed the results of local elections in 2008. The 99.6 percent result was the culmination of the government's five-year strategy of systematically closing down space for political dissent and independent criticism. European election observers said that the election fell short of international standards.

In the run-up to the 2010 elections there were a few incidents of violent assaults, including the March 1 killing of Aregawi Gebreyohannes, an opposition candidate in Tigray. More often, voters were influenced by harassment, threats, and coercion. The Ethiopian government's grassroots-level surveillance machine extends into almost every community in this country of 80 million people through an elaborate system of kebele (village or neighborhood) and sub-kebele administrations, through which the government exerts pressure on Ethiopia's largely rural population.

Voters were pressured to join or support the ruling party through a combination of incentives-including access to seeds, fertilizers, tools, and loans-and discriminatory penalties if they support the opposition, such as denial of access to public sector jobs, educational opportunities, and even food assistance. During April and May officials and militia from local administrations went house to house telling residents to register to vote and to vote for the ruling party or face reprisals from local party officials, such as bureaucratic harassment or losing their homes or jobs.

Political Repression, Pretrial Detention, and Torture

In one of Ethiopia's few positive human rights developments in 2010, in October the government released Birtukan Midekssa, the leader of the opposition Unity for Democracy and Justice Party, after she spent 22 months in detention. Along with many other opposition leaders, Birtukan was initially arrested in 2005 and then pardoned in 2007 after spending almost two years in jail. She was rearrested in December 2008. In December 2009 United Nations experts determined that her detention was arbitrary and in violation of international law.

Hundreds of other Ethiopians have been arbitrarily arrested and detained and sometimes subjected to torture and other ill-treatment. No independent domestic or international organizations have access to all of Ethiopia's detention facilities, so it is impossible to determine the number of political prisoners and others who have been arbitrarily detained.

Torture and ill-treatment have been used by Ethiopia's police, military, and other members of the security forces to punish a spectrum of perceived dissenters, including university students, members of the political opposition, and alleged supporters of insurgent groups, as well as alleged terrorist suspects. Secret detention facilities and military barracks are most often used by Ethiopian security forces for such activities. Although Ethiopia's criminal code and other laws contain provisions to protect fundamental human rights, they frequently go unenforced. Very few incidents of torture have been investigated promptly and impartially, much less prosecuted.

Torture and ill-treatment of detainees arrested on suspicion of involvement with armed insurgent groups such as the Oromo Liberation Front and the Ogaden National Liberation Front in Somali region remains a serious concern. The Ethiopian military and other security forces are responsible for serious crimes in the Somali region, including war crimes, but at this writing no credible efforts have been taken by the government to investigate or prosecute those responsible for the crimes.

Freedom of Expression and Association

The government intensified its campaign against independent voices and organizations, as well as its efforts to limit Ethiopians' access to information in late 2009 and 2010. By May, when the parliamentary elections took place, many of Ethiopia's leading independent journalists and human rights activists had fled the country due to implicit and sometimes explicit threats. While a few independent newspapers continue to publish, they exercise self-censorship.

In December 2009 government threats to invoke the 2009 Anti-Terrorism Proclamation against the largest circulation independent newspaper, Addis Neger, forced its editors to close the paper and flee the country. A few days later, police beat an Addis Neger administrator responsible for winding down the newspaper's affairs.

Other newspapers were also threatened or attacked. The Committee to Protect Journalists reported that 15 journalists fled the country between late 2009 and May 2010. An official of the government's media licensing office accused the Awramba Times of "intentionally inciting and misguiding the public." In August unknown assailants smashed windows and doors of its office. In September police interrogated the editor of Sendek after it published interviews with an opposition party leader; the police purportedly were investigating whether the newspaper was licensed.

In March a panel of the Supreme Court reinstated large fines against the owners of four publishing companies convicted in 2007 for "outrages against the constitution" solely for their coverage of the 2005 parliamentary elections. In February a judge sentenced the editor of Al Quds to one year in prison for an article he wrote two years earlier challenging Prime Minister Meles Zenawi's characterization of Ethiopia as an Orthodox Christian country.

Foreign media did not face much better. The government began jamming the Voice of America language programs in Amharic, Oromo, and Tigrinya in February 2010 and followed by jamming Deutsche Welle; the jamming ended in August. Prime Minister Meles personally justified the jamming on the grounds that the broadcasters were "engaging in destabilizing propaganda" reminiscent of Rwandan radio broadcasts advocating genocide.

The assault on independent institutions extends to nongovernmental organizations, particularly those engaged in human rights work. The repressive Charities and Societies Proclamation, enacted in 2009, forbids Ethiopian nongovernmental organizations from doing work on human rights or governance if they receive more than 10 percent of their funding from foreign sources.

The effects of the law on Ethiopia's slowly growing civil society have been predictable and devastating. The leading Ethiopian human rights groups have been crippled by the law and many of their senior staff have fled the country due to the sometimes blatant hostility toward independent activists.

All organizations were forced to re-register with the newly created Charities and Societies Agency in late 2009. Some organizations have changed their mandates to exclude reference to human rights work. Others, including the Ethiopian Human Rights Council (EHRCO), Ethiopia's oldest human rights monitoring organization, and the Ethiopian Women's Lawyers Association (EWLA), which engaged in groundbreaking work on domestic violence and women's rights, slashed their budgets, staff, and operations. The government froze both groups' bank accounts in December 2009, allowing them access to only 10 percent of their funds. Meanwhile, the government is encouraging a variety of ruling party-affiliated organizations to fill the vacuum, including the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, a national human rights institution with no semblance of independence.

Key International Actors

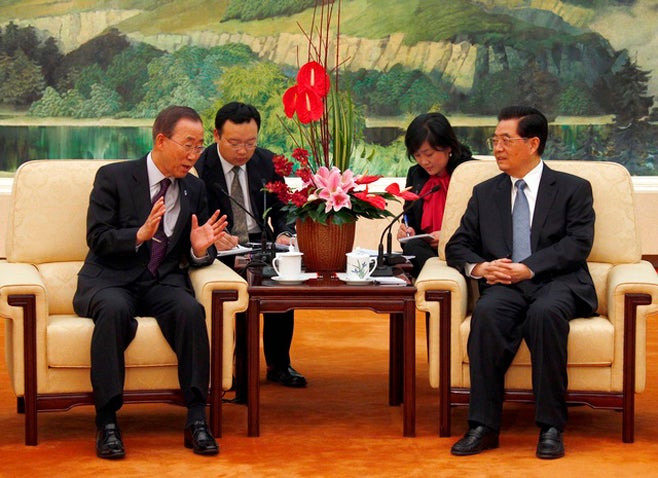

Regional security concerns-particularly regarding Sudan's upcoming referendum and the increasing reach of Somalia's Islamist armed groups-have thus far insulated Ethiopia from increased human rights pressure from Western donors. Ethiopia's African neighbors have been mute in the face of Ethiopia's deteriorating human rights situation, while China, South Korea, and Japan have increased engagement in 2010, although their contributions remain small compared to Western aid. Chinese money largely flows into infrastructure, although trade also increased 27 percent to more than US$800 million in the first six months of 2010, according to The Economist.

Few governments commented publicly on the increasing political repression gripping the country in the months before and after the May elections. In a rare exception, the United States noted in late May that "an environment conducive to free and fair elections was not in place even before Election Day." The European Union's election observers also raised multiple concerns with the unlevel playing field and constraints on freedom of assembly and expression. Yet even after the election result proved the EPRDF's consolidation of a single-party state, Ethiopia's donors continued to channel enormous sums of development assistance through the government. The government received more than $3 billion in development assistance in 2008 alone.

The final report of the UN Human Rights Council's Universal Periodic Review of Ethiopia's human rights record was adopted in March 2010. Ethiopia committed to ratifying the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. It rejected recommendations that it repeal or amend the Charities and Societies Proclamation and that it end the impunity of Ethiopia's security forces.