(New York) – Bolivian authorities should repeal a November 15, 2019 decree granting the military overly broad discretion to use force, and stop harassing independent journalists and government opponents, Human Rights Watch said today. Nine people died and 122 were wounded during a demonstration in Chapare province on November 15.

Since Jeanine Áñez assumed office as interim president, the government has adopted and announced alarming measures that run counter to fundamental human rights standards. The decree contributes to impunity for military abuses during crowd control operations. The government also announced that it would prosecute journalists and former high-level authorities for “sedition.”

“We are extremely concerned by measures taken by Bolivian authorities that appear to prioritize brutally cracking down on opponents and critics and give the armed forces a blank check to commit abuses instead of working to restore the rule of law in the country,” said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “The priority should be to ensure that the fundamental rights of Bolivians, including to peaceful protest and other peaceful assembly, are upheld.”

Bolivian authorities should stop harassing journalists and government opponents and ensure that judicial authorities conduct independent, impartial, and prompt investigations into deaths during clashes between security forces and protesters.

Michelle Bachelet, the United Nations high commissioner for human rights, said on November 16 that the recent deaths “appear to be the result of unnecessary or disproportionate use of force by the police and army.” The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights reported that at least 23 people have died since the October 20 presidential election and 700 more have been injured.

On November 15, Áñez adopted a presidential decree, deploying the military in “defense of society and public order.” The decree exempts members of the armed forces from criminal responsibility when they act “in legitimate defense or state of necessity” and respect the “principles of legality, absolute necessity and proportionality” as defined under specific provisions of Bolivian law.

The decree runs counter to the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, international standards that provide authoritative guidance on security officers’ use of force. The basic principles require law enforcement officials, in carrying out their duty, to apply non-lethal force as much as possible before resorting to firearms in violent protests. Whenever the use of firearms is unavoidable, law enforcement officials should use restraint and act in proportion to the seriousness of the risk faced. The legitimate objective should be achieved with minimal damage and injury, and preservation of human life respected. Under the UN Basic Principles, the intentional lethal use of firearms is permissible only “when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.”

The decree and the legislation cited in it fail to distinguish between the use of firearms and the deliberately lethal use of firearms – that is, the distinction between shooting and shooting with intent to kill, Human Rights Watch said. This is a key distinction because even in those very limited cases in which the use of firearms is unavoidable, officers should normally not shoot to kill.

“Áñez’s decree is inconsistent with international human rights standards and sends the dangerous message to soldiers in the streets that they will not be held accountable for abuses,” Vivanco said. “The decree should be urgently repealed.”

On November 13, the newly appointed minister of government, Arturo Murillo, warned that the government will “go after” and incarcerate people who commit “sedition” – a crime that is vaguely defined and carries up to three years in prison under Bolivian law. Bolivia’s criminal code defines “sedition” as the crime committed by “rising against the government authority … publicly and in open hostility,” including by “oppos[ing] the execution of national or provincial laws or resolutions.”

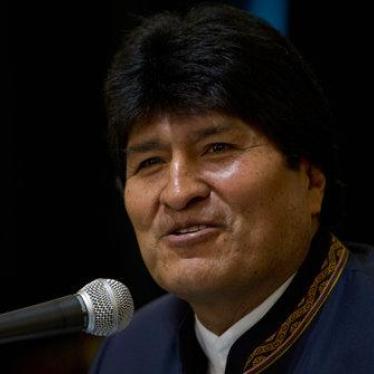

Murillo said that the government would also “hunt down” Juan Ramón Quintana, minister of government under former President Evo Morales, whom he described as “an animal.” Any investigations and prosecutions against former officials from Morales’ MAS political party should strictly respect due process guarantees, Human Rights Watch said.

On November 14, the newly appointed communication minister, Roxana Lizárraga, said that the government “will take the pertinent actions,” including “deportation” against journalists who are “committing sedition.” Since civil unrest broke after the October 20 election, several journalists have been attacked, according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and Bolivia’s Ombudsperson’s office.

“No journalist should be prosecuted or deported for doing their job,” Vivanco said. “In times of crisis, the general public needs journalists more than ever. The government should be taking measures to protect them, not threaten them.”