Summary

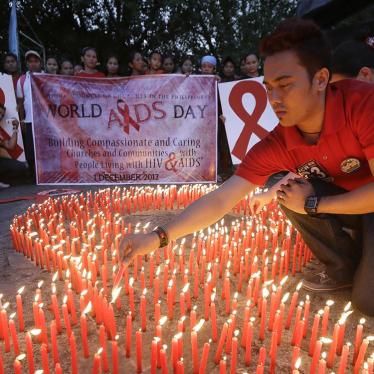

The Philippines is facing one of the fastest-growing epidemics of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the Asia-Pacific region. According to official statistics, HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men has increased tenfold in the last five years. In 2015, the Department of Health reported that at least 11 cities have recorded HIV prevalence rates of more than 5 percent among men who have sex with men, with Cebu City, the county’s second largest city, recording a 15 percent prevalence rate in 2015. Those statistics dwarf the 0.2 percent overall HIV prevalence rate for the Asia-Pacific region and 4.7 percent overall HIV prevalence rate in Sub-Saharan Africa, which has the most serious HIV epidemic in the world.

The country’s growing HIV epidemic has been fueled by a legal and policy environment hostile to evidence-based policies and interventions proven to help prevent HIV transmission. Such restrictions are found in national, provincial, and local government policies, and are compounded by the longstanding resistance of the Roman Catholic Church to sexual health education and condom use. Government policies create obstacles to condom access and HIV testing and limit educational efforts on HIV prevention. Children may be particularly vulnerable to HIV due to inadequate sex education in schools and misguided policies requiring parental consent for those under 18 to purchase condoms or access HIV testing.

Despite its claims that it is adopting policies to help prevent the spread of HIV, the Philippine government is failing to adequately target HIV prevention measures at men who have sex with men (MSM). HIV prevention education in Philippine schools is woefully inadequate and the commercial marketing of condoms to MSM populations is nonexistent. (MSM is an umbrella term originated by health professionals for men and male youth who have sexual relations with persons of the same sex, whether or not they identify as gay or bisexual or also have sexual relationships with women.)

The Philippine government has erected barriers to condom access and HIV testing for men who have sex with men and adolescent males who engage in same-sex practices, particularly those under 18, factors that all contribute to the worsening epidemic. Philippine rights activists for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people blame these policy failures on the government’s focus on HIV prevention policies that target heterosexual couples rather than members of the LGBT community.

As early as the 1990s, the Philippines earned international praise for its policies to prevent HIV transmission. HIV emerged in the Philippines in the 1990s primarily among commercial sex workers in the country’s urban centers. The government responded to that outbreak by aggressively promoting condom use among sex workers through strategies including the deployment of former sex workers as educational outreach volunteers and making the health secretary at the time, the jocular and grandfatherly Juan Flavier, the human face of an official condom promotion movement. Flavier marketed condom use as an activity that was as fun as it was potentially life-saving through media-friendly antics such as inflating condoms in front of journalists and photographers. The government pursued this strategy despite fierce opposition from the Catholic Church. The strategy was a success and contributed to low numbers of people living with HIV.

According to government statistics, which may not accurately reflect the real situation, the number of people living with HIV rose from 2 in 1984 (the year HIV was first reported in the Philippines) to 835 by 2009. From 2009 to 2010, the number of people living with HIV doubled to 1,591 as more men who have sex with men contracted HIV. Government statistics reflect the rise of rates of HIV transmission among MSM populations: health records indicate that 81 percent of the approximately 35,000 cases of HIV recorded between 1984 and June 2016 have been among men who have sex with men.

The government has not tailored HIV prevention policies to address the needs of populations most at risk of HIV infection, a failure that has facilitated HIV transmission among MSM populations. A 2013 report by the World Health Organization (WHO) on the Philippine government’s response to the HIV epidemic warned that “most [government anti-HIV] programme activities remained focused on FSWs [female sex workers], mostly through the vast and busy network of SHCs [social hygiene clinics], while HIV continues to spread, unabated, among other key populations that have little or no access to services suited to their needs.”

Some of the main factors fueling the HIV epidemic among MSM populations include government policies and social stigma that limit condom access. In the Philippines, condoms are readily available for retail sale at pharmacies and convenience stores. However, a legal restriction embodied in the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012 (Republic Act No. 10354, known as the RH Law) prohibits condom purchases by individuals under the age of 18 without parental consent. As a result, retail store employees routinely refuse to sell condoms to youths or demand that they provide identification proving their age, which can be off-putting even for those over 18.

Further, government condom education and access programs fail to take into account the imposing public stigma that retail condom purchases can involve, particularly for teenagers. Human Rights Watch spoke to many people with HIV age 18 to 35 who described their unease when buying condoms. Although the government provides free condoms at public social hygiene clinics (SHCs), which provide no-cost contraceptive supplies and family planning services, many Filipinos will not visit SHCs because they carry a social stigma related to their outreach activities for commercial sex workers.

Local government policy and legal obstacles can further restrict condom access for men who have sex with men and the wider population. The RH Law’s prohibition on condom sales to children without parental consent notwithstanding, the law provides a wide array of reproductive health products and services, including reproductive health care, sexuality education, HIV prevention and treatment, and management of AIDS. However, governments in at least two cities have responded to the RH Law’s passage by passing local ordinances and executive orders banning the sale and distribution of family planning supplies, including condoms.

The mayors of Balanga City in Bataan province and Sorsogon City in the Bicol region have both issued directives to government clinics—which low-income people rely on for health care—forbidding them from procuring and distributing contraceptive products, including condoms. The mayor of Sorsogon, Sally Lee, has threatened to punish government employees who refuse to comply with the order. Mayor Lee has called for the removal of condoms from government clinics due to what municipal health personnel have described as “morality issues” related to the use of condoms. Representatives of the official Commission on Human Rights have criticized the anti-condom policies of Sorsogon and Balanga as threats to public health, and have warned that similar policies might be adopted by other cities in the Philippines.

In January 2015, the Philippine Senate cut one billion pesos (about US$21 million) from the Department of Health’s budget intended for family planning commodities, including condoms. Senators who lobbied for the cut justified it on the basis of fiscal savings. But critics contend that the cut reflected the influence of conservative elements in the Senate. The impact of this cut on condom supplies in 2016 has so far been minimal due to adequate back-supply of condoms at clinics and SHCs. But doctors warn that unless the Senate reinstates the needed funding for contraceptive products, SHCs and other government clinics are likely to exhaust their condom supplies in early 2017.

The government’s failure to provide adequate public access to HIV testing is also fueling the epidemic. Philippine law prohibits HIV testing of children below age 18 without the consent of parents or guardians. This seriously limits HIV testing of men who have sex with men in the 15 to 25 age bracket. Although some clinics skirt the law by assigning clinic personnel to act as “guardians,” public health officials describe the age restriction as a serious obstacle to testing, counseling, and treatment for adolescents and young men, and a barrier to accurately measuring the epidemic’s growth.

These restrictions in part reflect the influence of the Catholic Church on government health and education policy. An estimated 80 percent of Filipinos are Roman Catholics, and the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) has long had an obstructive influence on government anti-HIV policies. Since the early 1990s, the CBCP has issued official statements vilifying condoms, campaigned against legislation that would expand condom access, and levied personal attacks against government officials who favor inclusion of condoms in HIV prevention programs. The Church, backed by conservative lawmakers, has obstructed efforts to expand public education and awareness of the value of condoms in HIV prevention on the basis that condom use promotes promiscuity.

The administration of President Fidel Ramos, who was in office from 1992 to 1998, overrode such objections in favor of evidence-based HIV prevention measures that included condom use. However, the governments of both President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo from 2001 to 2010 and President Benigno Aquino III from 2010 to 2016 failed to give priority to condom use as an HIV prevention method in apparent deference to Catholic Church sensitivities.

The administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, who assumed office on June 30, 2016, has yet to announce any specific policies to address the country’s HIV epidemic. However, during the campaign Duterte spoke in favor of improving the rights of LGBT people, which LGBT rights activists hope will extend to needed policies for addressing the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men. Duterte has also committed his government to full implementation of the RH Law. At the same time, Duterte has engaged in vitriolic anti-gay rhetoric, which may indicate a different path than the one suggested by his more positive public pronouncements.

Currently, the Philippine government fails to provide adequate school education programs on safe sex practices, particularly condom use. Both the RH Law and the Philippine AIDS Prevention and Control Act of 1998 (Republic Act No. 8504, known as the AIDS Law) mandate compulsory “age- and development-appropriate” sexuality education for adolescent children. The RH Law specifically provides for “comprehensive sexuality education,” which includes sexual health, children’s rights, and values formation. However, in practice the majority of public and private schools provide no sex education classes or instruction on methods to prevent sexually transmitted infections.

Most of the people living with HIV interviewed for this report said that their schools provided no sex education lessons, let alone specific lessons on HIV prevention and condom use. Those who told us that their schools did offer sex education courses described the curriculum as focused strictly on dry explanations of human reproductive functions, rather than on condom use to prevent sexually transmitted infections.

The Department of Education (DepEd) tried in 2006 to implement a pilot sexuality education program in its curriculum. However, strong opposition from conservative lawmakers backed by the Catholic Church scuttled the plan. Private schools, many of them established by Catholic orders including the Jesuits and De La Salle Brothers, have also refused to implement mandatory sex education classes on the grounds that such teachings “promote sin.” At one private Catholic school in Manila in 2009, the school administration rejected a sex education module because it did not explicitly condemn masturbation as a sin. As a result, implementation of Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) effectively remains in limbo. The DepEd only issued its draft of official standards needed to teach CSE in early 2016, and it had not yet officially adopted them at time of writing.

The absence of effective promotion and retail marketing of condoms also limits their use, particularly among MSM populations. Commercial mass media advertising for retail branded condoms including Trust and Frenzy is relatively rare in the Philippines. A Philippines-based manufacturer of Trust blames the lack of advertising on obstacles created by the Ad Standards Council (ASC), a private group tasked by the government to regulate outdoor advertising. The ASC discourages the use of even the word “condom” in billboard ads, let alone an actual photo of a condom or any overt display of same-sex affection.

The Philippine government, with the assistance of international agencies and donors that support health in the Philippines, should demonstrate leadership in taking the necessary measures to address the country’s worsening HIV epidemic. That leadership hinges on the political will to recognize both the severity of the epidemic and the decisive role that the government can play in addressing it. By removing legal and policy obstacles to condom access and remedying the dangerous deficit in public awareness of safer sex and HIV prevention methods, the Philippine government would have the opportunity to stop a growing health crisis in its tracks.

Key Recommendations

To the Philippine Government

- Abolish current legal restrictions that bar youth under 18 years of age from purchasing condoms or getting HIV tests without parental or guardian consent, and provide adolescent-friendly, supportive, and confidential HIV prevention, testing, and treatment services.

- Develop an explicit national condom promotion strategy and take immediate and effective steps to counter misinformation about condom use, particularly among men who have sex with men.

- Impose appropriate penalties on municipalities that refuse to comply with the RH Law’s guarantee of public distribution of contraceptive commodities, including condoms.

- The Department of Education should implement its age-appropriate sex education modules in public and private schools nationwide, with specific and evidence-based instruction on HIV prevention. Information about safer sex, particularly non-stigmatizing information about condom use, should be required teaching in senior high school and college.

To International Donors and Agencies Supporting Health in the Philippines

- Ensure that all donor-funded HIV/AIDS education and capacity building programs include programming specifically targeting education of and outreach to men who have sex with men.

- Assess condom needs in national and local health clinics, consult HIV/AIDS nongovernmental organizations about condom supply needs, and work with the Department of Health to ensure sufficient condom supplies nationwide.

Methodology

This report is based on research Human Rights Watch conducted between February and October 2016 in four cities in Metro Manila (Quezon CIty, Makati, Mandaluyong, and Manila) and in Cagayan de Oro, Cebu City, Puerto Princesa, Sorsogon City, and Balanga City. Human Rights Watch selected these cities mainly because of their high HIV incidence and prevalence rates. We conducted research in Sorsogon City and Balanga City due to the local governments’ adoption of policies that explicitly prohibit the sale or distribution of contraceptive supplies, including condoms.

Two Human Rights Watch staff conducted the field research and interviews. Human Rights Watch first consulted nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that advocate for LGBT rights as well as groups that advocate for the rights of people living with HIV. These groups helped Human Rights Watch contact many of the individuals interviewed for this report.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 82 individuals for this report, including 39 people living with HIV, as well as LGBT rights advocates, advocates for the rights of people with HIV, health workers, government officials, and peer educators. The interviews with people living with HIV were conducted one-on-one, primarily in local languages (Tagalog and Cebuano), with some interviews held using an interpreter. The interviews with advocates, government officials, and representatives of NGOs were conducted primarily in English. Human Rights Watch obtained documents from advocates and government officials for this report, as well as information in the public domain.

Human Rights Watch obtained explicit verbal consent from each participant. Most of the interviewees asked that we use pseudonyms or only their first names in referring to them due to concerns of public stigma related to their sexual orientation, gender identity, or HIV-positive status. All of them were informed of the purpose of the interviews, that their responses were voluntary, and that they could end the interview at any time. No compensation was given to any of the interviewees, although some were reimbursed for transportation expenses, especially those who lived far from the interview location.

This report focuses specifically on HIV risk and government failure to mitigate risk for men who have sex with men. This is of course only one population at risk of HIV. Other populations at heightened risk include intravenous drug users, sex workers, and female partners of men who have sex with men. Routes of transmission aside from sex between men include sexual transmission between male and female sex partners and between female sex partners; transmission through needle or syringe sharing or through contact with an HIV-infected syringe or needle; and transmission from mother to child during pregnancy, birth, or breastfeeding.

We have chosen to focus on men who have sex with men in this report because of the rapid increase in infection rates among this population in the Philippines, and due to the specific barriers to adequate HIV prevention efforts this population continues to face.

I. History of the Philippine Government’s Anti-HIV Efforts

Unlike in other parts of the world, the AIDS Epidemic in the Philippines has been growing rapidly. In 2000, only one new case every three days was diagnosed. However, by the end of 2013, there was already one new case every two hours.

–2014 Global AIDS Response Progress Reporting, Country Progress Report: Philippines

From 2010 to 2015, the Philippines recorded one of the fastest-growing epidemics of HIV in the Asia-Pacific region.[1] During that period, Pakistan and Afghanistan were the only countries in the region to have recorded faster growth in new infections.[2] The rise in new infections reflects the failure of successive Philippine governments to take necessary measures to reduce HIV transmission, particularly among men who have sex with men. In the 1990s, the Philippine government won praise for its HIV prevention strategies. Juan Flavier, the health secretary from 1992 to 1995, made condom promotion a key part of his program despite strident opposition from conservatives and the powerful Roman Catholic Church.[3] He often emulated the methods of Thailand’s “condom king,” Mechai Veravaidya, Thailand’s minister of health, tourism, and information from 1991 to 1992,[4] and wrote the country’s national HIV/AIDS law, the Philippine AIDS Prevention and Control Act of 1998.[5]

Jocular, grandfatherly, and never media-shy, Flavier became the face of condom promotion in the Philippines. He would promote condoms wherever he was, especially in front of the cameras.[6] A community doctor who popularized the “Doctors to the Barrios” program in the Philippines, Flavier had a down-to-earth, easygoing air that made him extremely popular among Filipinos. He introduced commercial sex workers to the public in an attempt to humanize the crisis and promote safer sex.[7] Flavier also challenged the Catholic Church’s opposition to condom promotion to reduce HIV transmission. In 1995, Flavier publicly excoriated bishops’ opposition to condoms. Diana Mendoza, a journalist who covered Flavier at the Department of Health, recalled him saying, “You know why? Because they don’t know where ‘it’ is and they don’t know where to put ‘it.’ So let’s give them samples of neon, glow-in-the-dark condoms.”[8]

Catholic Church officials, particularly the late archbishop of Manila, Jaime Cardinal Sin, denounced Flavier as “an agent of Satan” for pursuing his bold condom promotion strategy in the 1990s.[9] At a public rally in 1994, the cardinal reportedly threatened to “tie a millstone around [Flavier’s] neck and drop him in the middle of Manila Bay.”[10] When Flavier distributed condoms to journalists covering President Ramos’s 1992 trip to Thailand, Senator Francisco Tatad accused him of promoting “promiscuity, lechery, adultery, and sexual immorality,” and called for his resignation.[11] In 2001, Cardinal Sin issued a pastoral letter entitled “Subtle Attacks Against Family and Life,” in which he referred to the “naturally occurring minute pores present in all latex materials,” and stated that “the condom corrupts and weakens people … destroys families and individuals … and spreads promiscuity.”[12]

Such opposition to condoms influenced anti-condom regulations at the municipal level. Jose “Lito” Atienza, then mayor of the city of Manila, approved in 2000 Executive Order 003 (EO 003), which effectively banned the sale and distribution of any artificial contraceptives supplies, including condoms, from city health clinics.[13] In a 2007 report on the impact of EO 003, the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR) said:

According to Manila City health officials and hospital directors, women are also warned as part of their education on NFP [natural family planning] that contraceptives are unsafe or ineffective.[14] These people—all medical doctors—talked about the possible cancerous effects of oral contraceptives, identified certain types of pills as “pesticides” and described condoms as ineffective in protecting against HIV.[15]

CRR found that EO 003 “violates women’s right to health by limiting their access to affordable and acceptable essential reproductive health services and information, and increasing their risk of maternal mortality and morbidity, complications (including death) from induced abortions and exposure to HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases.”[16]

Alfredo Lim maintained his own version of a ban on condoms and other contraceptive supplies after he succeeded Atienza as Manila mayor in 2007. In October 2011, Mayor Lim issued Executive Order 030, which stated that the city “shall not disburse and appropriate funds or finance any program or purchase materials, medicines for artificial birth control,” including condoms.[17] However, the order also directed the city to allow couples and families to “exercise full and absolute discretion” in planning their families according to their religious belief and practices.[18]

At the national level, the official approach to HIV prevention changed profoundly after then-President Joseph Estrada replaced Flavier after taking office in 1998. Under Estrada, condom use became a less-prominent aspect of the government’s HIV control programs. The political upheaval created by Estrada’s impeachment in 2001 and the rise to the presidency that same year of his vice president, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, also sidelined government HIV prevention efforts. The Arroyo administration stopped government procurement of reproductive health products including condoms.[19] Arroyo also redirected funds from a government program to support contraceptive programs and awarded the money to the religious group Couples for Christ to teach “natural family planning,” such as the rhythm method.[20]

These policies have undermined government efforts to combat HIV transmission, particularly among men who have sex with men. In June 2002, the United Nations special envoy for HIV/AIDS in Asia, Dr. Nafis Sadik, warned that the Philippines had “huge explosion potential” for an HIV epidemic given the presence of many known routes of HIV transmission such as low condom use among sex workers and increasing rates of adolescent sexual activity.[21] This observation was echoed in September 2003 by then-Health Secretary Manuel Dayrit, who noted that the presence of sexually transmitted diseases such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis among Filipinos signaled that HIV could spread throughout the population unless swift measures were taken to prevent it.[22] In 2004, Human Rights Watch issued a report warning of the potentially dire consequences of deficiencies in the Philippine government’s HIV prevention policies.[23]

Although the administration under President Benigno Aquino III fought the Catholic Church’s opposition to the RH Law, which mandates the provision of funding for government-supplied condoms to public clinics, it was unable to block attempts by the Senate to slash the budget for family planning supplies, including condoms, in the 2016 budget.[24] It also failed to institute programs specifically benefitting MSM populations. According to Stephen Christian Quilacio, executive director of the Northern Mindanao AIDS Advocates, the epidemic was exacerbated by “the [Aquino] government’s failure to address HIV, give focus to the problem, and provide the resources to tackle it.… If the government cannot promote the use of condoms to prevent HIV, surely there’s a problem there.”[25]

Advocates for the rights of LGBT people also blame the previous government for its failure to address the lingering stigmatization of LGBT people by both officials and the wider Philippine society, emphasizing the role of such stigma in the spread of HIV. As Jonas Bagas, a longtime advocate for the rights of LGBT people and people with HIV in the Philippines, stated:

I suppose if the epidemic exploded among, say, mothers and children, we would have a different response by the government. The fact that the epidemic is concentrated on [men who have sex with men], however, makes [the government] ignore it. That happens all the time with government: “If it’s gay people who are affected, let’s just look for them, have them tested, list those who are positive, and then we can monitor their movements and behaviors.” The biggest challenge [to addressing the HIV epidemic] is stigma.[26]

The Philippines has many of the same HIV risk factors as its Asian neighbors. What is distinctive about the Philippines is that as much as 85 percent of its population of 100 million subscribes to Roman Catholicism and an increasingly powerful evangelical movement, and the leaderships of these religions object to the use of condoms for any purpose.[27] Studies have shown a link between adherence to Catholicism and low condom use.[28] Furious Catholic Church opposition to a pilot project of sexuality education implemented in two Manila schools in 2006 and scheduled for eventual national implementation prompted the government to scrap the initiative.[29] The Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) had protested the initiative and warned that “the introduction of sex education into the public schools would encourage teenagers to try premarital sex rather than remain abstinent, and emphasized that sex education is the parents’ responsibility, not the government’s.”[30]

The Catholic Church’s influence on official HIV prevention initiatives has at times produced contradictory, self-defeating policies. In September 2003, then-Health Secretary Manuel Dayrit warned that a combination of high-risk behaviors and rates of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) could result in a massive HIV epidemic unless swift prevention measures were taken.[31] Yet when asked by Human Rights Watch about his country’s approach to condom promotion, Dayrit defended his department’s decision to fund faith-based family planning programs that shunned condom use. Dayrit said that condoms in the Philippines were provided by many local jurisdictions, and that he could “only persuade” jurisdictions that banned condom sales and distribution—such as Manila City—to change their policies.[32] When pressed, however, Dayrit acknowledged the effectiveness of condoms against HIV, albeit as a last resort after sexual abstinence. “The best way to avoid HIV is to abstain from risky behavior,” he told Human Rights Watch. “And if you can’t help yourself, you have to consider using a condom.”[33]

Although the Philippines’ HIV prevalence rate of below 1 percent among the country’s population of 100 million is still low compared to many other countries,[34] it is experiencing a sharp rise in new infections among key affected populations and areas.[35] Philippine government statistics are not always reliable and thus may not accurately reflect the actual situation; however, they do allow for some useful comparisons. From January 1984 to June 2016, the Philippines government recorded 34,999 HIV cases.[36] Of that number, 28,984—nearly 83 percent—were recorded between January 2011 and June 2016. The number of new HIV transmissions recorded daily rose from only 1 in 2008 to 14 in 2014 to 26 by June 2016.[37] At least 11 cities registered HIV prevalence rates among men who have sex with men of more than 5 percent, with one—Cebu City, the country’s second largest—recording a staggering 15 percent prevalence rate in 2015.[38] Those statistics dwarf the 0.2 percent overall HIV prevalence rate for adults in the Asia-Pacific region and 4.7 percent overall HIV prevalence rate for adults in Sub-Saharan Africa, which has the most serious HIV epidemic in the world.[39] The Department of Health warns that the number of HIV infections in the Philippines could reach 133,000 by 2022.[40]

The main mode of HIV transmission remains unprotected sexual intercourse. But whereas in the 1990s this was mainly via heterosexual sex, there are increasing reports of new infections due to unprotected sex among men who have sex with men.[41] According to government statistics, the number of infections among this population increased tenfold between 2010 and 2015, and now eclipses the total number of infections in all other key affected populations.[42] According to the Department of Health’s quarterly HIV surveillance report issued in June 2016, condom use among men who have sex with men is low—only 44 percent reported using condoms during their most recent sexual encounter, and more than half of the respondents who did not use condoms said the main reason was that condoms were not available.[43]

These trends particularly affect adolescents (defined as children and young adults ages 10 to 19), who face multiple vulnerabilities to infection such as comparatively high rates of unprotected sex, stigma, and exclusion from government response to the HIV/AIDS crisis.[44] According to Philippine government data, new HIV infections in adolescents increased by 230 percent from 2011 to 2015, most of it due to unprotected sex.[45] Meanwhile, HIV incidence rates among children and young adults ages 15 to 24 increased by 780 percent from 2001 to 2015.[46]

President Rodrigo Duterte, who took office in June 2016, has yet to make any policy statements on how he will address the country’s HIV epidemic. However, he has committed to fully implementing the RH Law, which obligates the government to provide condoms and other contraceptive products to the public.[47] Despite Duterte’s public use of the pejorative term “son of a whore” to describe a gay United States ambassador,[48] LGBT rights advocates have been encouraged by Duterte’s condemnation of discrimination against LGBT people and his support for same-sex marriage, hoping he will also take a more proactive, evidence-based approach to the country’s HIV epidemic.[49]

II. How Poor Condom Policies Are Contributing to the HIV/AIDS Crisis

The sales lady actually asked for my ID. And she asked me what am I going to use [the condoms] for, why am I buying a condom.

–Bryan, 24, a peer educator from PinoyPlus, an HIV/AIDS support group based in Manila

Laws and Policies that Obstruct Condom Access

Laws and policies at the national, provincial, and municipal levels in the Philippines have undermined condom access and thus increased the risk of HIV transmission, particularly for children under the age of 18. Statistics indicate the severe impact of those laws and policies. Condom use in the Philippines is the second lowest in the Asia-Pacific, with only 38 percent of men who have sex with men under 25 years old using condoms in their last sexual encounter, according to a ranking by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) based on 2009-2014 data.[50] Condom use among men who have sex with men of any age in the Philippines is very low at only 44 percent.[51]

Government studies indicate an alarming trend among adolescents, who are part of the population segment registering the fastest growth in new HIV infections.[52] Only 35 percent of adolescent MSM who had anal sex used condoms the last time they had sex, and only 11 percent used condoms consistently with their last three partners.[53] The main reason given by 61 percent of the respondents was “unavailability of condoms.” Younger men have greater difficulty than older men in accessing condoms, according to the Department of Health’s 2015 survey.[54] Among boys and young men ages 15 to 19, 54 percent “did not buy or receive free condoms,” while only 12 percent bought them.[55] The same survey indicated that while 45 percent of Filipinos age 20 or older who have had anal sex used condoms during their most recent encounter, only 39 percent of those ages 18 to 19 did so, and only 29 percent of those ages 15 to 17 did so.[56]

A key battleground is the RH Law.[57] The law obligates the government to provide a wide array of reproductive health products and services to Filipinos, including contraceptive and HIV prevention products such as condoms.[58] The law mandates compulsory sex education in schools as well as state-subsidized treatment of HIV and AIDS.[59] Opponents of the law sued before the Supreme Court, which in March 2013 ruled to stop enforcement of the law.[60] The next year, on April 8, 2014, the court upheld the constitutionality of the law but conservatives still managed to convince the court to stop the sale and distribution of Implanon and Implanon NXT, two hormonal contraceptive brands, by government clinics.[61]

But despite the value of the RH Law in ensuring public access to condoms to prevent HIV, it also imposes an unreasonable and contradictory age restriction for condom access that undermines efforts to improve access to condoms for adolescents, particularly males who have sex with other males. The law states, “No person shall be denied information and access to family planning services, whether natural or artificial.” Yet it also states, “Minors [children under the age of 18] will not be allowed access to modern methods of family planning without written consent from their parents or guardian/s except when the minor is already a parent or has had a miscarriage.”[62] The country’s AIDS Law also imposes this restriction on HIV testing for children under 18.[63]

The result of the prohibition on children accessing condoms is that retail store clerks routinely require young people purchasing condoms to provide photo identification to confirm that they are at least 18 years old.[64] Several people living with HIV described to Human Rights Watch being humiliated in convenience stores by clerks who demanded identification and then refused to sell them condoms because they were too young and did not have IDs. Bryan, a peer educator from PinoyPlus, an HIV/AIDS support group based in Manila, said the RH Law’s age restriction on condom purchase without parental consent and its enforcement in retail stores is a powerful disincentive for young people to buy and use condoms: “It impresses on them that they are not allowed to use a condom because they are not allowed to buy [them].”[65]

In addition to the limitations of the RH Law, condom availability is affected by continuing pervasive stigma around condom purchase in the Philippines. For many, the fear of being ridiculed by retail store staff creates a strong disincentive to buying condoms. “Condoms are available in drugstores and supermarkets, so these are accessible, but it’s a question of stigmatizing access,” said Teresita Bagasao, the Philippines country director for the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).[66]

Young Filipinos just starting to explore their sexuality are particularly likely to be deterred from buying condoms in retail outlets because of that stigma, said Adrian, 25, a peer educator with LoveYourself, a support group for people with HIV in Manila. “The stigma is still there. So, if you wait in the queue at the cashier and people in front of you are carrying drinks, chips, chocolates, and here you are holding a condom,” he said.[67]

Chard, 25, a peer educator for CebuPlus, an HIV support group in Cebu City, told Human Rights Watch:

These men who have sex with men are happy that there are NGOs that distribute condoms for free, because we’ve found out that they are embarrassed to buy condoms from stores even if these condoms are literally within reach. It’s because when they buy at the pharmacy, the clerks and cashiers couldn’t help looking at them as if they’ve done something wrong. They felt like they were being judged each time they do this in a drugstore. I actually tried buying condoms myself just to see if this had basis. The cashiers looked at me, whispered with each other and snickered.[68]

There is also a powerful social stigma attached to the government social hygiene clinics (SHCs), which offer free condoms and other sexual health-related services. The stigma is linked to the SHCs provision of services to sex workers, who commonly source their condoms and other supplies from these facilities. “You can get condoms, even when you are young, from these social hygiene clinics. These are available—you just don’t have easy access because of the stigma,” said Jhaye Encabo, program manager at CebuPlus. “Let’s say I’m 15. If I were go to the social hygiene clinic, some personnel there would make comments about why I’m [accessing] condoms that would embarrass me. I would be too embarrassed.”[69]

Mara Quesada, the executive director of Achieve, an NGO that provides legal aid to clients with HIV, said the stigma attached to SHCs undermines their effectiveness as condom distribution points for young men who have sex with men. “There may be condoms in the social hygiene clinics,” she said. “But that’s not where the [most at risk of HIV transmission] communities are.”[70]

Recognition of the barriers to distributing condoms to men who have sex with men due to the social stigma surrounding SHCs has prompted at least one municipality—Quezon City, the city with the highest HIV prevalence in the country—to convert some SHCs into so-called sundown clinics that cater to men who have sex with men by extending their operating hours from 11 p.m. to dawn. Sundown clinics provide discrete services in areas with bars and nightclubs patronized by men who have sex with men who would otherwise avoid buying condoms at SHCs or retail stores due to stigma. One such SHC is Klinika Bernardo, an award-winning project by the Quezon City government that caters to the needs of men who have sex with men and promotes HIV prevention, testing, and treatment. After the clinic opened in 2012, the number of those who received testing and counseling increased dramatically, from about 3,000 in 2012 to more than 7,000 in 2013.[71] The government said it plans to open more of these sundown clinics in Quezon City.[72]

In other cities, however, local governments are obstructing HIV prevention efforts. The city government in Balanga City in Bataan province, just southwest of Manila, has banned local public health officials and clinics from the procurement or distribution of contraceptive supplies since Mayor Joet Garcia took office in 2007. A local municipal health official told Human Rights Watch that on Garcia’s order, the city stopped buying contraceptives and refused to distribute those being delivered by the national government through the Department of Health.[73] The interruption in supply of government-provided contraception has compelled Balanga City residents to either buy them from pharmacies or, in the case of women, to clandestinely purchase them from local government-employed midwives at relatively high cost.[74] There has been no research on the impact of these restrictions on rates of HIV transmission among men who have sex with men in Balanga City.

The Balanga City health official told Human Rights Watch that the mayor’s anti-condom policy was a reflection of “his conservative religious convictions” and was strictly oral, rather than an explicit written policy.[75] “Everything was made verbally. Deliveries from the Department of Health national office were refused and were delivered instead to the provincial health office,” the health worker said.[76] Garcia stepped down as Balanga City mayor in May 2016 after being elected to Congress but has been succeeded by his brother Francis, who has not announced any changes to the city’s ban on public provision of contraceptives to low-income residents.[77] Human Rights Watch sent a letter to Mayor Francis Garcia on October 31, 2016, urging him to protect the right to health of Balanga City residents by immediately lifting restrictions on public access to contraceptive supplies, including condoms.[78] Mayor Garcia had not responded to the letter at time of writing.

Other localities have had similar experiences. One barangay (neighborhood or village) in Muntinlupa City, Ayala-Alabang, for example, enacted an ordinance in 2011 that requires a doctor’s prescription for condoms.[79] But the restrictions on condom access that the mayor of Sorsogon City, Sally Lee, has imposed are among the most onerous and obstructive of HIV prevention efforts in the country.

On February 2, 2015, Lee signed Executive Order No. 3 declaring the city a “pro-life city.”[80] The order does not explicitly prohibit family planning services and contraceptive supplies; however, health workers and reproductive health advocates said the city government issued oral orders to the staff of the city’s public clinics, which normally provide contraceptive supplies free of charge, to cease distribution and instead promote only “natural” family planning methods such as the Catholic Church-approved “rhythm method.”[81] That cessation includes condoms. City government officials subsequently removed all contraceptive supplies from the city’s government-operated clinics and health centers.[82] The Sorsogon City Health Office also declined Department of Health deliveries of these products on the basis that they violated the mayor’s declaration of the city as “pro-life.”[83]

Senior Sorsogon City government officials warned city employees that failure to comply with the “pro-life” directive could be grounds for dismissal.[84] Some of those employees told Human Rights Watch in interviews that the municipal government subjected them to surveillance, by assigning other employees to watch them and report any violations to the office of the mayor, to ensure compliance with the “pro-life” directive.[85] Two midwives employed by Balanga City government health clinics declined interviews with Human Rights Watch due to their concerns that they were “under surveillance” by elements of the mayor’s office.[86]

Mayor Lee specifically ordered the removal of condoms from government health clinics. A report prepared by personnel from the Department of Health’s provincial office in collaboration with local NGOs said Lee ordered the condoms be removed “because [she] doesn’t want condoms due to morality issues.”[87] Staff of some social hygiene clinics in Sorsogon City told Human Rights Watch that the executive order compelled them to distribute condoms clandestinely.[88] Lee’s “pro-Life declaration may hinder the STI/HIV prevention efforts and programs of the Local AIDS Council, due to prohibition of use/distribution of condoms,” concluded a 2015 Department of Health assessment of reproductive health services in Sorsogon City.[89]

As a result of such policies, low-income residents who previously relied on free-of-charge distribution of contraceptive supplies—including condoms to prevent HIV infection—must now either buy them in commercial establishments or abandon their use altogether because of cost. Such restrictions also stigmatize access to condoms in an environment in which governments at all levels are already failing to adequately promote condoms for HIV prevention.[90] Human Rights Watch is not aware of any research into the possible impact of the “pro-life city” executive order on transmission of HIV among men who have sex with men in Sorsogon City, but restrictions on public access to contraceptive products, including condoms in both Balanga City and Sorsogon City, has prompted the national Commission on Human Rights in 2016 to launch a nationwide investigation into the legality and health impact of such directives.[91] Human Rights Watch sent a letter to Mayor Lee on October 31, 2016, urging her to protect the right to health of Sorsogon City residents by immediately lifting restrictions on public access to family planning supplies, including condoms.[92] Mayor Lee had not responded to the letter at time of writing.

Inadequate Education on Safe Sex Practices and Condom Us

I never used condoms because I didn’t know [about] condoms. I didn’t know what safe sex was.

–Nathan, a 24-year-old HIV-positive gay man from San Mateo, Rizal province, May 2016

Millions of Filipinos are not sufficiently educated about the role of condoms in preventing HIV transmission. Department of Health data indicates that only one out of five men who have sex with men have basic knowledge of HIV.[93]

Mark, 29, a make-up artist in Manila, contracted HIV in 2015. Mark later learned he had likely acquired the virus through unprotected sex with a man who had begun showing symptoms linked to HIV/AIDS.[94] Mark said he was aware of HIV but had “received no education” about it. “In school, we got no formal sex education. In biology class, we only had technical information [about conception and pregnancy].”

Jake, 20, from Misamis Oriental province, was diagnosed with HIV in 2015. He said he had engaged in commercial sex work when he was 17, serving mostly male clients, some of them foreigners. “I was doing this work, which paid for my schooling, but I had no idea about condoms and HIV,” he said.[95] JM, a 29-year-old man from Cagayan de Oro City who was diagnosed with HIV in 2013, said that he led an active sex life involving unprotected sexual behavior but had almost zero knowledge about HIV and how to protect himself from it. “It sounds stupid, yes, but that’s how it was,” he said.[96]

Vincent, 39, a call-center employee and former teacher from Davao City, was diagnosed with HIV in 2015. He blamed his lack of awareness about how to prevent HIV through use of condoms on the absence of sex education in school. “Even when I was already a teacher, we didn’t have discussions [on HIV or sex education], didn’t even have books about sexuality,” he said. “In the provinces, we were not encouraged to discuss sex and sex education [with] students.”[97]

LGBT rights advocates say that such lack of awareness is a foreseeable outcome of the government’s failure to adequately address the epidemic. “The government should launch a massive and sustained awareness drive on HIV and condom use,” said Raffy Aquino, the director of Philippines Side B, a research-oriented group composed of LGBT activists who identify as bisexuals.[98]

“There was no sex education at all in the early days and there is no sex education now,” said Fritzie Caybot-Estoque, chairperson of the Misamis Oriental Cagayan de Oro AIDS Network, one of the first HIV/AIDS NGOs in the southern Philippines.[99] Jhaye Encabo, program manager of CebuPlus, an AIDS advocacy group in Cebu City, concurs: “The schools do not teach about HIV in the general curriculum.” In the few instances that schools would tap CebuPlus to discuss HIV in class, school administrators would insist that such briefings include a thorough discussion of contraceptive techniques such as abstinence, but “they won’t let us mention condoms, let alone demonstrate condom use.”[100]

Edu Razon of PinoyPlus said schools often invite his organization to provide sessions on sexuality to make up for its absence in the curriculum. People are trying to offer sex education, he said, but the problem is many of the schools are Catholic-run and some find teaching HIV prevention “too radical, too medical.” And so, when trainers from his organization were invited to provide a session in schools, Razon said, administrators would tell them to focus on sexual abstinence and “not to emphasize condoms.”[101]

A top administrator at a Catholic school in Quezon City told Human Rights Watch that HIV and safer sex “are topics we don’t take up in school. Not yet anyway.” Religious opposition is a factor, she said, but it is also because school administrators remain “clueless” about how to teach sex education “in a way that does not offend [traditional Catholic] sensibilities.”[102]

Teresita Bagasao, UNAIDS country director, pointed out that there is a policy on sex education contained in the RH Law, “but you don’t have implementation.”[103] In fact, the government failed—“forgot,” Bagasao said—to include a budget for sexuality education in the curriculum for the 2014-2015 school year. It has since been reverted in the 2016 budget.

The Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) standards that the Department of Education (DepEd) must implement as part of its compliance with the RH Law, which lawmakers passed in 2012 but continues to be the target of an ongoing Supreme Court challenge, remained unimplemented at time of writing.[104] The CSE standards, which were prepared through a DepEd consultation with the women’s health group Likhaan and other NGOs, contain instructions that the DepEd will apply to sex education classes in the country’s schools.

Unlike the Curriculum Guide for Health (Grade 1 to Grade 10) that the DepEd released in 2013, the CSE standards are more specific about sex education and the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. “We need these standards,” said Dr. Ella Naliponguit, director of the DepEd’s Bureau of Learner Support Services. “As to when these are going to be enforced, that remains the question.”[105]

Naliponguit said the government has always had reproductive health education in its curriculum mainly for grades 4 to 6 of the public school system. While the curriculum currently does not provide specific information about sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, Naliponguit said that such information can and should be part of the curriculum. Philippine schools, both public and private, are required by law to teach reproductive health from junior to senior high school.[106] The goal of reproductive health classes is to “provide an idea of sex education” to students by the time they are 15 years old. However, the DepEd acknowledges that private schools generally ignore this requirement. The DepEd has also never assessed the quality of reproductive health education in public schools, and there are no specific modules that target the LGBT population.[107]

The biggest obstacle to meaningful sexuality education in Philippine schools, which already includes modules on condom use to prevent HIV and on the specific risks to men who have sex with men, is the refusal or inability by teachers to address such issues in class, according to educators and activists who work on behalf of rights for people with HIV. “There are teachers who are not comfortable talking about this, who are not trained to talk about this. So we cannot teach condom use in schools,” Naliponguit said.[108] “We try to teach sexuality education as a values formation subject. It’s not a stand-alone subject,” said Ophelia Petate, head teacher at the Casile National High School in Laguna province. “The students are very curious but not a lot of teachers can provide all the answers.” She said that condoms are sometimes mentioned but not extensively: “No, there are no demonstrations of condom use.”[109]

The absence of specific teaching standards on HIV prevention methods fails to address the needs of LGBT students for information about how condom use can help protect them from HIV transmission. Philippines Secretary of Education Leonor Briones, who took office in July 2016, has promised to enhance sex education by making it a separate, stand-alone subject and not just a sub-lesson in science class.[110] The DepEd recognizes the urgency of HIV prevention and, while it does not have HIV specific programs, intends to launch what Naliponguit called “teen hubs” in public schools staffed with trained guidance counselors to dispense advice on sexuality and sexually transmitted infections like HIV. The DepEd is still developing the concept of these “teen hubs,” which will cater mainly to high school students. “It’s a start,” Naliponguit said.[111]

However, “teen hubs” will not actively promote condom use or discuss risks and prevention measures specific to men who have sex with men, and, as such, are unlikely to address the serious sex education deficit contributing to the growth in the HIV epidemic powered by new infections among this group.[112] A representative of a foreign aid organization that supports the Philippine health sector said that in terms of sex education and HIV prevention education, the Philippines “is extremely far behind.… If you look at the curriculum, [sex education and HIV prevention] is pretty near nonexistent. It is up to individual schools, which raises question of quality and consistency.”[113]

“The biggest stumbling block is [lack of] awareness, especially in schools,” said Dr. Gundo Weiler, the World Health Organization (WHO) representative in the Philippines.[114] That view is echoed by Ami Evangelista Swanepoel, executive director of Roots of Health, a reproductive rights group in Puerto Princesa City, one of the cities that has a greater than 5 percent prevalence rate among men who have sex with men. “[Public] knowledge about HIV and all issues related to sex is very low,” she said. “Condom use is really, really low. To be able to have a fighting chance [to reduce new HIV infections], there has to be an aggressive condom promotion.”[115]

Some public health experts say that the government has failed to retool its traditional messaging on condom use and promotion, which has long focused on commercial sex workers and heterosexual couples, to address HIV among men who have sex with men. “The messaging about condoms has not changed. The public is always told: ‘Abstain! Be faithful!’ That doesn’t work among men who have sex with men because you know they have multiple sex partners,” said Mara Quesada, executive director of Achieve.[116]

The Catholic Church’s long-standing opposition to the use of condoms for any purpose is part of the institutional reticence to teach safe sex practices including the use of condoms to prevent HIV infection. Those views are persuasive in a society in which about 80 percent of Filipinos are Roman Catholics.[117] Official Catholic teaching, as expressed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, is silent on the use of condoms against HIV. However, Catholic teaching opposes the use of condoms for artificial birth control, and many bishops’ conferences, Vatican officials, and theologians have interpreted this as an all-out ban on condom use for any purpose. The potential public health implications of this interpretation have divided Catholic ethicists between those who support condoms as a “lesser evil” than HIV infection and those who fear that allowing any leeway for condom use will promote sexual promiscuity and ultimately lead to the acceptability of condoms for birth control.[118]

The Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP), the official organization of all diocesan bishops of the Catholic Church in the Philippines, approaches anti-HIV measures in strictly moral terms, arguing in 2015 that many Filipinos who contract HIV are products of “broken, dysfunctional families.”[119] The CBCP instead advocates an HIV prevention program that emphasizes a “moral lifestyle,” and sexual abstinence rather than condom usage.[120] Its strategy runs counter to research studies which demonstrate that an abstinence strategy is ineffective for HIV prevention.[121]

The CBCP also blocks the implementation of education programs on HIV prevention in the country’s more than 1,000 Catholic schools, which are mandated by law to teach sex education, including on HIV/AIDS.[122] Catholic schools service only a small percentage of the country’s total grade school and high school population of 21 million. But Catholic schools refuse to teach sexuality education—including modules on HIV/AIDS transmission—because the Catholic Church, through the CBCP, rejected a 2009 DepEd module on sex education. The CBCP justified the rejection on the basis that the module did not explicitly define masturbation as a “sin.”[123] The CBCP’s legal advisor also took part in an unsuccessful class suit in 2010 against the DepEd aimed at stopping sex education in public schools.[124] While the effort was unsuccessful, the outspoken opposition of the Catholic Church to public health measures that are proven to prevent HIV transmission is extremely influential among Filipino Catholics and thus undermines the success of those measures.

The Catholic Church’s opposition to condom use has stigmatized usage among high-risk populations, said Jonas Bagas, a Filipino LGBT rights advocate.[125] “The religious groups and the Church have a big role to play in perpetuating this stigmatization,” he said. But he views the government as equally to blame for buckling under the pressure of the Church: “Some imagine the intensity of the Church’s ire so have become afraid themselves instead of performing their mandate.” According to Vinn Pagtakhan, executive director of the HIV support group LoveYourself, the Church’s clout and influence—which it often exerts during elections by using pulpits and pastoral letters to denounce government actions and laws such as the RH Law—particularly affects those in smaller villages, towns, and cities.[126]

Teresita Bagasao, UNAIDS country director, has discerned a softening in the CBCP’s anti-condom stance. She said there is “no longer the full-on attack against condoms” by Church officials. But she concedes that the Church has yet to use its public influence to openly advocate HIV prevention strategies that include promoting condom use. “We have allies inside the Church, but [they] won’t speak openly,” she told Human Rights Watch.

Obstacles to Condom Promotion and Retail Marketing

Condoms are a sensitive product so you have to [frame the public service message] in a different way. Not just about the product, but empathy for people and the problem. [So in an ad] if there is only one man, it’s okay. If there are two men, that’s problematic if the situation is in a bedroom, or if the [men] are “lovey-dovey.”

–Digna D. Santos, Executive Director, Ad Standards Council, Makati City, April 2016

WHO has urged the Philippine government to develop a “national condom strategy” that would make the contraceptive easily and readily available, aided by a social marketing approach and private sector promotion.”[127] Such a recommendation is crucial because condom promotion is almost entirely absent in the Philippines.[128]

Human Rights Watch interviewed many people with HIV who had little knowledge of where to purchase condoms. Jhun, a 37-year-old gay man who acquired HIV in 2013, said he did not use condoms in sexual contacts prior to learning about his HIV-positive status “because I did not know where to access or buy them.”[129]

In 2013, the Department of Health commissioned WHO and UNAIDS to conduct an external review of the government’s response to HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Among its findings:

Social marketing of condoms for the general population is not encouraged in the Philippines; social marketing of condoms targeting key populations is not actively implemented; condom promotion through the media does not exist; and condom distribution at risky venues is not allowed due to the barrier of local ordinances. Although supplied by the Department of Health to social hygiene clinics, condoms are not always available or actively promoted in these facilities. Peers, volunteers and outreach workers do not always carry condoms or promote their correct and consistent use.[130]

There are relatively few condom advertisements in Philippine mass media.[131] Those condom ads that do exist invariably depict heterosexual couples or a single male model.[132] The word “condom” is not used on billboards.[133] And the advertisements are almost all produced by DKT International, a large Philippines-based condom manufacturer, rather than government-produced public service announcements.[134]

Health advocates say that the type and volume of condom advertising and promotion in the Philippines is woefully inadequate considering the rapidly growing HIV epidemic,[135] and no commercial advertising or public service announcements target the population with the fastest increase in new HIV infections—men who have sex with men. “Private condom manufacturers do not want yet to promote condoms among the LGBT communities or targeting men who have sex with men specifically,” said Jonas Bagas, a Filipino advocate for the rights of LGBT people and people with HIV.[136] “There hasn’t been any attempt for MSM advertising” to promote condoms, said Vinn Pagtakhan, executive director of LoveYourself.[137] Dr. Gundo Weiler, the WHO representative in the Philippines, echoes that assessment. “It’s a question of marketing condoms to key affected populations, especially men who have sex with men. It’s not so much [condom] affordability but [condom] accessibility.”[138]

The failure to adequately promote and market condoms to address the realities of the Philippines’ MSM-driven HIV epidemic is rooted in conservative guidelines on permissible advertising. The Ad Standards Council (ASC), a self-regulatory private-sector group tasked by the government’s Consumer Protection Act to regulate and enforce advertising standards, has contributed to the problem by restricting the nature and content of condom advertisements to highly conservative heteronormative standards.. The nonprofit condom supplier DKT International has complained of the ASC “blocking or watering down” public advertising for condom usage and sales, undermining knowledge and access to condoms. “You can’t even use the word condom in your ad,” said DKT International Vice President for Marketing, Emman Alfonso, speaking about the restrictions on LGBT-oriented condom advertising.[139] Alfonso says there is an ASC bias in favor of heteronormative condom advertising that exclusively depicts male and female relationships, saying it has impeded condom advertising that caters to the preferences, needs, and sensitivities of men who have sex with men.[140]

Article 201 of the Philippines Revised Penal Code[141] allows the government to censor “immoral doctrines, obscene publications and exhibitions and indecent shows,” a vague phrase that invites broad censorship.[142] Public figures who advertise condoms are at risk of legal action for doing so. Ang Kapatiran Party senatorial candidate Jo Aurea Imbong filed an injunction against DKT International and the actor Robin Padilla in 2010 for allegedly violating both article 201 and article 200 of the Revised Penal Code (criminalizing “Grave Scandal” by persons who “offend against decency or good customs by any highly scandalous conduct”) for a condom television commercial featuring Padilla.[143]

However, Digna D. Santos, ASC’s executive director, disputes Alfonso’s assertion that the ASC bars condom-related advertising. “In terms of billboards, there are restrictions on skin exposure, sex and violence. But we don't have any specific provisions that condoms can't be mentioned. Trust Condom has ads with the word ‘condom,’” she told Human Righs Watch.[144] However of the three Trust condom billboard ads Human Rights Watch has observed in Metro Manila between May and November 2016, two of those ads featured a man and a woman and neither used the word “condom.” The third ad featured a solitary man and the word “condom” was only mentioned as part of the URL for the company’s Facebook page.[145]

Dr. Ilya Tac-an, head of the HIV/STD Detection Unit of the Cebu City Health Office, attributes conservative condom advertising guidelines to the influence of the Catholic church. “The Catholic Church is very vocal against condom use, which is why they are not really advertised and promoted in the media.”[146] Recent interventions by the Catholic Church to stifle condom advertising support Tac-an’s assertion. In February 2014, the CBCP urged the government and the Ad Standard Council to stop showing condom advertisements.[147] That same year, the CBCP denounced a Valentine’s Day condom promotion campaign.[148]

HIV Testing Obstacles

Young people feel ashamed and embarrassed to get tested [for HIV] because people find out you’re sexually active. I was one of them.

–Charlie, 23, an HIV-positive teacher who worked as a part-time sex worker starting at age 14, Cagayan de Oro City, May 2016

The overwhelming majority of men who have sex with men in the Asia-Pacific region—about 95 percent of those ages 15 to 19, and 85 percent of those ages 20 to 24—are not tested for HIV.[149] WHO data indicates that “only 15 percent of men who have sex with men [in the Asia-Pacific region] have ever had an HIV test and only 5 percent were tested in 2012 and know their result.”[150]

“Some people are afraid to know whether they are infected or not, so they would rather not get tested until it’s too late, when they start having symptoms—that’s the time they decide to get tested,” said Cholo, a peer educator with LoveYourself.[151] Dr. Gundo Weiler, the WHO representative in the Philippines, described the lack of testing as an impediment to adequately tackling the epidemic. “There’s a big backlog of people who are not diagnosed. We want to see more diagnoses,” he said.[152]

As noted above, one of the major obstacles in the Philippines to getting young men who have sex with men tested is a restriction in the AIDS Law that requires children under 18 to have parental consent for an HIV test.

Public health experts say this is a problem because it poses a challenge to identifying people with HIV and helping them get treatment if needed, and because it hobbles efforts to accurately measure the epidemic. “It’s a significant problem, and amending the AIDS Law is required,” said Teresita Bagasao, UNAIDS country director.[153]

“Everyone should receive proper health care, and if you deny someone testing that could potentially bring about further risk to the person, then you’re denying the person health care,” said Vinn Pagtakhan of LoveYourself.[154]

Advocates of children’s rights also criticize the parental consent requirement for HIV tests under the AIDS Law as a violation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which the Philippines ratified in 1990.[155] UNICEF has criticized the need for parental consent for HIV tests for children as a powerful disincentive to accurate documentation of HIV transmission:

The ramifications of parental consent requirements for HIV testing in those under 18 should not be underestimated. Given the sensitivity of an HIV result–and its implications about sexual activity or injecting drug use in adolescents–parental consent can be a strong disincentive for under 18s to test and know their HIV status. Rigid age limitations on independent consent to testing—imposed by many Asia-Pacific countries—run counter to the concept of children’s evolving capacities and their right to participate in decisions regarding their own treatment, wellbeing and best interests.[156]

Advocates for the rights of people with HIV warn that children under the age of 18, particularly young men who have sex with men, are not getting HIV tests due to the parental consent requirement. “We’ve seen that 15 to 24 age group are the most vulnerable and they are precisely the same teenagers that are not being reached because of the [AIDS Law’s] requirement to have parental consent before a minor can be tested,” said Jonas Bagas, advocate for the rights of LGBT people with HIV.[157]

Some testing facilities agree to provide HIV testing for children under 18 if a person in authority such as a doctor is present to assess the need for an HIV test, effectively bypassing the need for parental consent.[158] However, that approach is far from universal at the country’s 131 Department of Health-accredited HIV testing and counseling centers.[159] Nor is it one that comports with international standards for HIV testing.

Awareness of one’s HIV status is a key element in the campaign to fight the epidemic because it encourages HIV-positive people to both adjust their sexual practices—particularly condom use—to help mitigate HIV transmission as well as to receive treatment.

The Department of Health is responsible for HIV testing and outsources much of that responsibility to NGOs including LoveYourself. But even LoveYourself is forced to limit HIV testing to individuals who are covered by PhilHealth, the national healthcare insurance system which limits coverage of people under 21 to individuals who are are wholly financially dependent on either a parent or legal guardian, or are classified as “indigents” by the Department of Social Welfare.[160] LoveYourself operates only two clinics in Metro Manila; the testing it does in these two facilities accounts for half of all testing in the metropolis and about 23 percent of testing nationwide.[161]

III. Philippine and International Law

Domestic Law

The AIDS Prevention and Control Act of 1998 (Republic Act No. 8504, known as the AIDS Law) is the Philippine government’s legislative response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The law’s “declaration of principles” calls for the promotion of “public awareness about the causes, modes of transmission, consequences, means of prevention and control of HIV/AIDS through a comprehensive nationwide educational and information campaign organized and conducted by the State.”[162] Article I of the law emphasizes education and information while article II is about safe practices and procedures. This law also creates the Philippine National AIDS Council, the government’s highest policy-making body on HIV/AIDS. The law has since come under criticism for being outdated and inadequate,[163] with some lawmakers now seeking an amendment that will remove the provision that requires parental consent for children wishing to avail themselves of HIV testing.[164]

The Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012 (Republic Act No. 10354, known as the RH Law), is landmark legislation that provides a comprehensive array of reproductive health services.[165] The result of more than a decade of contentious debate and negotiations in Congress, due mainly to opposition by conservatives and religious groups, the law has generally been praised by health advocates given the numerous and considerable reproductive health issues that Filipinos face.[166] Among other things, the law directs the government to put in place programs for the “prevention, treatment and management of reproductive tract infections (RTIs), HIV and AIDS and other sexually transmittable infections (STIs).” It also instructs the state to provide sexuality education and counseling.[167]

On April 3, 2013, the Department of the Interior and Local Government issued Memorandum Circular No. 2013-29 that aims to “strengthen local responses toward more effective and sustained responses to HIV and AIDS.”[168] This order enjoins local governments to convene local AIDS councils, which are considered effective in battling the epidemic and are in line with the department’s efforts to “localize” the response to HIV/AIDS.[169] The Local Government Guide for Practical Action, in localizing the official response to HIV/AIDS, lists men who have sex with men as one of the “key population-at-risk groups” for local governments to “forge partnerships with” in order to address the epidemic.[170]

International Law

International law obligates states to ensure access to condoms and related HIV prevention services as part of the human right to the highest attainable standard of health. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), ratified by the Philippines in 1974, directs governments to take steps “necessary for … the prevention, treatment and control of epidemic … diseases,” including HIV/AIDS.[171]

United Nations bodies responsible for monitoring implementation of the ICESCR have interpreted this provision to include access to condoms and complete HIV/AIDS information.[172] The right to information, including information about preventing epidemic diseases, is further recognized by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), ratified by the Philippines in 1986.[173]

The UN Human Rights Committee, the international expert body that interprets the ICCPR, in its draft General Comment No. 36 on the right to life, states, “The duty to protect life also imposes on States parties a due diligence obligation to take long-term measures to address the general conditions in society that may eventually give rise to direct threats to life. These general conditions may include … the prevalence of life threatening diseases, such as AIDS.”[174] The committee noted that long-term measures required for ensuring the right to life could include facilitating access to health care and promoting the development of life-saving and life-extending drugs and treatments. It states that governments should “adopt action plans for attaining long-term goals designed to realize more fully the right to life of all individuals, including the introduction of strategies to fight the stigmatization associated with diseases, including sexually-transmitted diseases, which hamper access to medical care.”[175]

The Convention on the Rights of the Child, ratified by the Philippines in 1990, affirms the rights of children to the highest attainable standard of health, and requires governments to ensure children have access to information and preventive health care.[176] The Committee on the Rights of the Child has interpreted these rights to include “the right to access adequate information related to HIV/AIDS prevention and care.” The Committee has urged governments to provide children with “services that are friendly and supportive, provide a range of services and information, are geared to their needs, ensure their opportunity to participate in decisions affecting their health, and are accessible, affordable, confidential, non-judgmental, do not require parental consent and do not discriminate.” Those services and information include “access to HIV related information, voluntary counseling and testing, knowledge of their HIV status, confidential sexual and reproductive health services, free or low cost contraception, condoms and services, as well as HIV-related care and treatment if and when needed, including for the prevention and treatment of health problems related to HIV/AIDS,” in addition to “voluntary, confidential HIV-counseling and testing services, with due attention to the evolving capacities of the child.”[177]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child General Comment No. 15 on the right to health states that governments “should review and consider allowing children to consent to certain medical treatments and interventions without the permission of a parent, caregiver, or guardian, such as HIV testing and sexual and reproductive health services, including education and guidance on sexual health, contraception and safe abortion.”[178]

IV. Recommendations

To the Senate and House of Representatives

- Amend or repeal provisions of the RH Law and AIDS Law that bar youth under 18 years of age from purchasing condoms or getting HIV tests without parental or guardian consent.

- Reinstate funding under the RH Law for procurement and distribution of contraceptive supplies, including condoms, at government clinics.

To the Department of Health

- Develop an explicit national condom promotion strategy and take immediate and effective steps to counter all misinformation about condom use.

- Promptly act to ensure the viability of HIV prevention programs, particularly those that provide testing, treatment, and HIV awareness training to young people and those that provide outreach to and services for MSM populations and, as relevant, their female partners. Expand HIV/AIDS information and education campaigns for such individuals. Adopt measures that ensure accurate information about condom effectiveness during anal sex. Ensure distribution of this information through informal channels of peer educators as well as at health facilities. Involve nongovernmental organizations in the development of these strategies.

- Loosen restrictions on condom advertising to allow explicit mention of condoms in such ads and encourage and facilitate the production of condom advertising that targets men who have sex with men.

- Promote non-stigmatizing condom access systems, such as coin- or debit-card-operated dispensing machines in areas frequented by men who have sex with men.

To the Department of Education

- Accelerate efforts to create and implement a national sex education program for public and private schools that includes modules on the use of condoms to prevent HIV. Ensure that any program teaching “abstinence until marriage” has safeguards to ensure that information about condoms is not withheld, censored, or distorted.