Photographs of people who disappeared while attempting to migrate to the United States are laid out across the street from the US Capitol in Washington, DC, October 19, 2021.

People migrating to the US have increasingly died or disappeared while traversing the treacherous US-Mexico land border ever since the US government officially launched Prevention Through Deterrence at its southern border 30 years ago. These policies are explicitly aimed at forcing irregular migrants onto "hostile terrain," making crossing the US southern border so dangerous that it discourages people from even trying. The policies intentionally funnel migrants into the harsh, mountainous Sonoran Desert, where temperatures fluctuate between searing heat and icy cold, or through the fast-moving currents of the Rio Grande, where their lives could be at risk. Deterrence also includes punitive immigration policies and dangerous infrastructure, such as border walls, razor wire, armed soldiers, river buoys equipped with saw blades, and surveillance technology. Mexican criminal groups and corrupt state officials systematically target migrants for violence, while missing person reports are rarely resolved, and the human remains of migrants – even in known mass graves – remain unidentified.

Below are nine personal accounts provided by family members whose loved ones disappeared or died while attempting to join them in the United States. The accounts span the three decades of US border deterrence and are the result of a collaboration between Human Rights Watch and the Colibrí Center for Human Rights, which uses DNA testing to help identify the remains of missing migrants and supports families searching for missing loved ones. Some accounts use pseudonyms or first names to protect the families from retaliation.

While every story is unique, they share important commonalities. Each person who tried crossing the border without US authorization felt it was the only way to reunite with loved ones, achieve financial stability, or flee violence and seek safety. It took purpose, hope, and courage to make the journey. When people disappeared, the US Border Patrol provided families with little to no support. Indeed, there is no coordinated US government response to locate missing people in the borderlands. Additionally, after people disappeared, families were often targeted by extortionists, falsely claiming they captured or had information about missing family members, demanding ransom money.

Over the 30 years, groups estimate that between 10,000 and 80,000 people died at the border – the wide-ranging figure highlights the lack of information – with thousands more disappeared, mostly Brown, Indigenous, and Black migrants from Latin America. Deaths and disappearances have hit record highs under President Joe Biden’s administration.

While the deterrence strategy has failed to reduce migration numbers, it has enriched criminal groups, including smugglers and kidnappers, and wasted billions of taxpayer dollars. For some border agents, tasked with carrying out these policies, the work has led to moral injury and even suicide.

To prevent more deaths, the United States should end deterrence policies and create more safe and legal pathways to migrate, as well as humane processing for new arrivals. The government should also increase funding for more search, rescue, and recovery efforts. When the US government regulates migration, it needs to do so in a manner respectful of human rights—including the right to life, which should be paramount in border and immigration policies.

Danny Pérez

“I've had dreams where he returns,” Angélica Pérez said. “In these dreams, I see him, and I get so excited that I wake up and ask for it to be true.”

The last time Angélica spoke to her younger brother, Danny Pérez, was on November 25, 2015, one day before Thanksgiving. Danny was getting ready to cross the border from Mexico into the United States, to come home. He would never arrive.

Danny was born in Mexico, and he and his family migrated to Northern California in 2000 when he was 5 years old to reunite with their father and to seek a better quality of life. Angélica remembers dark, cold nights traversing the Sonoran Desert south of the US border. Danny remembered almost nothing about living in Mexico.

When Danny was a teenager in California, his parents returned to Mexico. He stayed behind, moving in with Angélica, who became his caretaker, and her children. “This is where he grew up and had friends,” she said. “To go back to Mexico was to not know anyone.”

Still in high school, Danny skateboarded, played soccer with a local team, and wrote and performed rap music with his friends. He was close to Angélica’s oldest son, Alexander. In school, Alexander would proudly say he had a big brother who was also his uncle.

When he turned 18, Danny decided to go to Mexico. In 2012, he rejoined his parents in Guanajuato, Mexico. When he arrived, he was full of ideas and energy. But after a failed attempt to launch an ice cream business with his father, and after struggling to get by in Mexico on low wages as a middle school English teacher, he decided to return to the United States.

He hired smugglers who said they would guide him through the desert mountains between the cities of Tecate and Tijuana.

“In his desperation, Danny thought that that was his only way in,” Angélica said, “He called … and I asked, ‘Are you sure it's safe? I'm scared.’”

Angélica remembers his answer: "Don't worry, I will go prepared,” he said. “I will take food and energy bars with me. I'll even take medicine and ointment. I'm strong enough to do this."

She began to panic when, the following day, she had heard nothing from her little brother. He had promised to let her know when he started crossing. She called him, but he didn’t pick up. The family began searching for Danny, calling US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), sharing Danny’s last known GPS coordinates with Mexican authorities, and reporting Danny as a missing person. Angélica repeatedly typed in her brother’s identifying information on government websites and searched through databases of the missing.

“It was ugly, having to see all of the unidentified bodies while at the same time asking God that we don't find him there,” she said. “We did everything we possibly could to find him.” They submitted DNA samples in both the United States and Mexico.

Like so many other loved ones who go missing in the borderlands, it may be impossible to know what happened to Danny.

“How do I say goodbye when we don't know anything about what happened?” Angélica asked.

His disappearance will have a permanent impact on his family. “If he is no longer with us, I would want him to know that he was always loved by my parents, by me, and that I keep loving him and always will,” she said. “I wish that instead of text messages, we could have talked on the phone, so I could have told him how much I loved him, even though I know he knew. I wish I could have said it to him.”

Hugo Patricio Tenezaca

Hugo Patricio Tenezaca, 19, called his mother, Romelia Yuqui, in New York City to ask for her blessing. He was going to cross the Sonoran Desert into the US. He went missing on June 17, 2012.

Hugo had first crossed the desert in October 2009, the first time he left Ecuador to be with her in New York.

Romelia, who is a US lawful permanent resident, had left Ecuador when Hugo was a child in search of a better life after her then-husband—a police officer—abused her.

For two years, Hugo worked at a bookstore in Manhattan, helping to pay off the debt of his previous crossing. He spent his free time playing with his much younger brother and sister, painting, drawing, and playing the guitar. Romelia still watches a video she has of him singing and playing guitar in the living room.

But when Hugo’s father died in Ecuador, Hugo decided to go back and support his sister, Mayra, who was being mistreated by their stepmother and siblings, and to study.

“I accompanied him to the airport,” Romelia said. “I saw his last look when he left, saying goodbye to me. I got down on the floor and cried. I told him, ‘Hugo, don't go,’ but he left.”

In Quito, things didn’t go as planned. Now that he’d lived in another country, his friends saw him as having money, began to take advantage of him, and ultimately beat him and stole from him. Meanwhile, Mayra was able to get a visa and went to the United States.

Hugo went to the US consulate and was at first approved for a visa to travel safely back to his mother. But then, Romelia recalled, his Ecuadorian passport was taken and US visa revoked for reasons the family do not understand. Without a legal way to migrate, Hugo became desperate. He and his mother contacted the same Guatemalan smuggler who had guided them across the first time and paid him US$14,000.

The journey was difficult, and he called Romelia often.

"Mom, we've arrived in Mexico, [and] it's not like when I crossed the first time,” Hugo said. “The road is complete terrorism. The drug traffickers assaulted the group we were traveling with, and I got under the car and didn't allow anything to be stolen." It took Hugo nearly a month to reach the border.

Hugo called her from near Altar, Sonora, to let her know he was going to cross and to ask her to say a blessing for him. He would be walking for about five days, he said, and would arrive in about eight days. He said he loved her very much.

That was the last time she spoke to him.

Eight days passed, and Romelia started making phone calls to locate her son. No one gave her a straight answer. She was told he had disappeared, that he’d gotten lost looking for water, that he took off running, that he fell asleep and didn’t wake up. She spoke to an Ecuadorian woman Hugo had met and befriended on the journey, who said she preferred to tell Romelia what had happened in person. She never did.

Romelia posted about Hugo on Facebook and lobbied the Ecuadorian consulates in New York and Arizona to help investigate. They were of no help.

People began to swindle Romelia – grifters who knew Hugo was missing and sought to exploit the situation. They would call, saying they had kidnapped Hugo and if she wanted to see him again, she would have to pay $2,000, $3,000, $7,000. Romelia would make desperate phone calls to raise the money, with no sense of how she would pay it back.

One cold night, a man called to ask for another $7,000, saying Hugo was in a red van around the corner. Romelia sent the money, went around the corner, and waited. There was no van, and no one came. The man called to say he couldn’t come because the area was “too hot” with police activity. But there were no police.

Romelia said, “If they had told me, ‘Your life in exchange for your son’s, I would have given my life.”

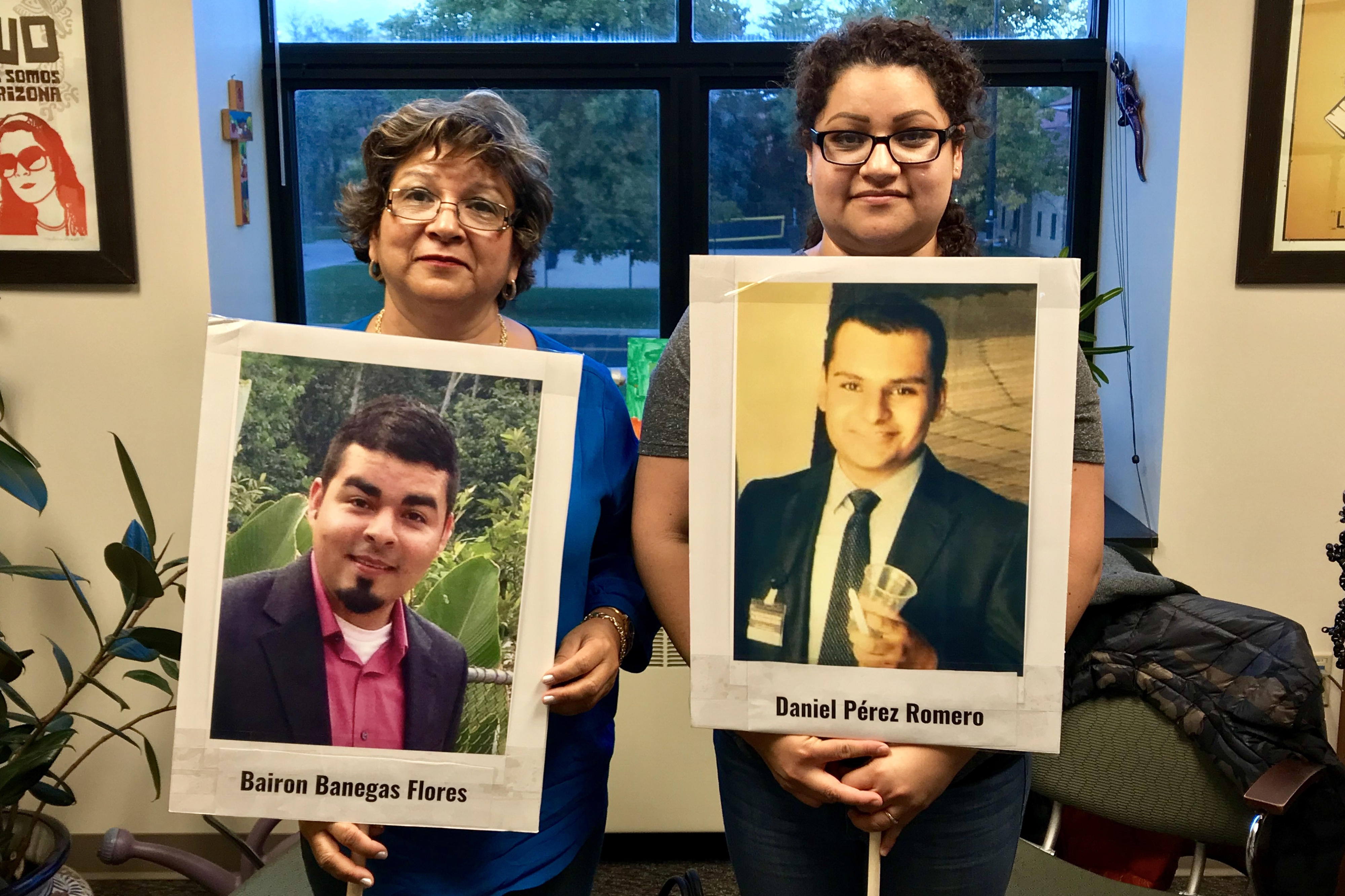

Bairon Fabrizzio Banegas Flores

In 1998, 17-year-old Bairon Fabrizzio Banegas Flores fled Honduras after his life had been threatened by a criminal group, leaving behind a note for his mother, Myrna: “Mommy, I’m going to the United States. Don’t worry about me, I’m going to get there. When I do, I’ll let you know.”

He made it to New York but ended up in the custody of US immigration officials. Because he was a child, he was placed in a facility that sought to find him a foster home until he turned 18. As an adult, he got involved with a church, and relocated to Bowling Green, Kentucky, where he met his wife and studied to be a pastor. He founded a church there, and he and his wife had two daughters.

Myrna wanted Bairon to be a doctor, and when she first visited him in the United States, he told her that her dreams had come true, but with a twist. “I am the best doctor and the best medicine for people because [as a pastor] I heal wounded hearts,” he said.

Bairon gained trust in the immigrant community and, over time, became not only a faith leader but a counselor for those facing deportation or other immigration issues. When the church sent him to Louisville, Kentucky, he continued to advise members in his congregation on immigration issues.

When one member of the congregation was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in 2013, Bairon, who was also unauthorized, went to the office to advocate for the fellow immigrant. While he’d never had a problem with ICE in Bowling Green, the ICE officials in Louisville had a completely different attitude. ICE officials asked him to show proof of his legal status. When he couldn’t produce any, they detained him and quickly deported him.

Myrna said. “I went to pick him up from the airport [in San Pedro Sula, Honduras,] and they arrived as if they were prisoners, as if they were criminals, chained up and all that...It was a terrible way [to treat them].”

He stayed in Honduras for six months, founding another church and working with local youth. But when one of his young daughters back in Kentucky became depressed, refusing to eat or come out of her room, he decided to go back to his family.

“I put my life in the hands of God, and I know he will help me and that I will make it to my daughter,” Myrna remembers he said when she asked him if he was sure about making the journey.

The last time Myrna spoke to her son, he told her he had already made it across the border into Arizona and that the following day the smugglers would pick him up at an agreed upon meeting place. She counted the days. She waited 8 days, then 10 days.

His family looked for him everywhere, but no one has heard from Bairon since. “At first it was very painful because he was always there—there wasn't a day in his life that he didn't call me or send a little text,” Myrna said.

Bairon’s absence has impacted his whole family, but especially his daughters. The oldest stopped going to church.

Myrna and her husband Raúl have since dedicated their lives to helping defend migrants’ rights. “I see what is happening at the border as so horrifying,” Myrna said. “We need to change the way immigrants are treated.”

Thousands of people have gone missing in the harsh and remote terrain at the US-Mexico border, including east of Sasabe, Arizona, pictured here on June 22, 2023. © 2023 Vicki Gaubeca/Human Rights Watch

Maya L.

Maya L. shared an apartment in Mexico City with her family—her husband, mother, sisters, and their children. Although they didn’t have a lot of money, they had one another.

“Everything was OK until the pandemic came,” Maya’s sister, Bianca, said.

Like more than 100 million people around the world, Maya’s husband, Marcus, lost his job when the city entered lockdown. The streets in one of the world’s largest cities were suddenly empty. Marcus struggled to find work, even chasing down a “promising” opportunity in a nearby state only to be scammed. The family had less money than ever.

Marcus sold his car and used the money to cross the Sonoran Desert. He arrived in the United States without incident, quickly found work in Arizona, and began sending money home. But he and Maya missed one another, and they soon decided Maya would also go to the United States.

“Mom, I'm leaving,” Maya said. “I'm going to build you a little house and we're not going to suffer anymore. I promise you I'll be back soon." She said she would come back in a couple of years.

Her mother was worried and wanted Maya to stay, but Maya had made up her mind. The day she left, her sister Bianca hugged Maya, squeezing her tight.

They knew from the news that crossing the border was dangerous, although they didn’t know of anyone who had disappeared.

Once Maya arrived in Sonora, close to the border, she had to stay inside a safehouse and wait. Maya said the coyote seemed like a good person. That he was with his wife surprised her – migrating women experience a disproportionate level of sexual abuse, and having a woman around helped Maya feel safer.

Marcus had paid the smuggler US$2,000 and was to pay another $3,000 once Maya made it across into the United States. After seven days in the safehouse, Maya told her family that she would be crossing and that they would talk when she arrived.

The family started to worry when a week passed with no word from Maya. They waited. Another week passed by. They called the coyote several times, and each time, he told them something different.

“She stayed behind on the nature reserve,” the coyote once said.

“No, she’s already here on this side,” he said another time.

“What happened is migration grabbed us and she ran with one of the guides and a cousin. The three of them took off.”

The last time they called, the coyote said that Maya had died. Then he stopped picking up the phone.

Her family called the Mexican consulate, US immigration authorities, medical examiners’ offices, and hospitals. No one could tell them what had happened to Maya. “It has been nine months without hearing from my sister, and it is like being dead, lifeless, because thinking about whether she is dead, whether they are prostituting her, whether someone has her . . . It is very exhausting to live with this daily,” Bianca said.

Marcus, suffering due to her disappearance, was eventually hospitalized in a behavioral healthcare facility.

Extortionists targeted the family. One of the guides from the group hired to take Maya across the border contacted the family, promising to send a few coyotes out in search of her remains in exchange for almost $5,000. The smugglers promised to carry any remains to the highway so that Border Patrol agents could be called to collect them.

“We gave in,” Bianca said. “The money was paid, [but] at the end of the day there was no response.”

In a separate incident, not long after posting a notice about Maya on Facebook, some people contacted her family to tell them they’d kidnapped her and demanded a ransom of $1,170. They sent a doctored photo, splicing Maya’s face from Facebook onto someone else’s body. The family never sent any money.

“They started telling us that if [we didn’t pay], they were going to kill her,” Bianca said.

But Maya’s family already suspects she is dead.

Mateo Dolores Salazar Hernández

Mateo Dolores Salazar Hernández had experience crossing the US-Mexico border. With family on both sides, Mateo, who lived in New Jersey and was known for his work ethic and optimism, had gone back and forth several times.

According to Mateo’s wife, Gloria Benítez, Mateo came to the United States to build a better life for the family. He wanted to be able to save up enough money so that they would not have to rely on their children in old age.

Mateo set out for Mexico again in May 2018 to meet his new great-granddaughter and to see his granddaughter, Diana Salazar, who calls Mateo “Dad.” He also went to attend the wedding of his daughter, Virginia.

“When he was coming, I told myself, ‘Finally, my little girl is going to meet my dad,’” Diana, who lived in Mexico at the time, said through tears.

But Mateo disappeared on his way back to the US. When he first went missing, the family called every place they could think of, including hospitals, detention facilities, and jails.

Finally, the family reached out to Ángeles del Desierto (Angels of the Desert), a nonprofit group that provides search and rescue services.

“He came through New Mexico, and [the smugglers] told us he stayed behind between Hachita and Playas, but we could never find him,” Gloria said.

The family drove down from New Jersey to search swathes of the desert, which spans hundreds of miles, situated between mountain peaks on either side. They met up with Ángeles del Desierto. “Where are you?” Diana asked the desert of Mateo.

After three days of searching, they called it off. A few months later, the Salazar family searched again for three days, still finding nothing. They submitted their DNA to Colibrí in case it could be matched with someone’s unidentified remains.

“My life changed, radically changed, when my husband went missing,” Gloria said. “We had 42 years of marriage, and I remember that my children used to tell us, ‘When you reach 50 years of marriage, we are going to throw you a party.’ Now time goes on, those 50 years are going to arrive. Let’s see if between now and our wedding anniversary we learn anything about what happened to him.”

Gloria thinks about what would have happened if she’d gone with Mateo to Mexico as he’d suggested, that maybe he wouldn’t have attempted to come back to the United States. But she has needed to be strong for her children, who have also struggled with what-ifs and accepting the loss of their father.

“I have another baby, now I have two,” said Diana, who remembers waking up early on summer mornings to the sound of Mateo cutting the grass and singing. “My son is named Mateo, and the truth is, I don’t lose hope that they will find him.”

Virginia, who was grateful to have seen her father at her wedding, recalled a song her father used to sing when he would come over – “Después de Tanto,” by José María Napoleón – often enlisting her now-husband to play the guitar in an impromptu karaoke session.

Today after so many years of not seeing you, I found you/Today when I saw you among the people without you realizing it, I knew that you live in me/I don't know, I don't know if I can go on, far from you.

[Hoy después de tantos años de no verte, te encontré/Hoy al verte entre la gente sin que tú te dieras cuenta supe que vives en mí/No sé, no sé si pueda continuar lejos de ti ]

Ofelia Muñoz Valenzuela

Ofelia Muñoz Valenzuela was from a small town, Ignacio de la Llave, in the coastal Mexican state of Veracruz. She disappeared at the US-Mexico border in 1997, when her daughter, Elena Gonzales, who today lives in New York, was just 14 years old.

Ofelia was locally famous as the “Güera Musiquera,” a nickname that came from her love of music. “She did not play any instrument, nor did she dance, but she had music in her veins,” Elena said about her mother. Not being able to dance or carry a tune did not stop Ofelia from trying. She would organize frequent dance parties in the town and stiffly move about on the dance floor.

“My dad was an alcoholic, he drank too much, and he always came home drunk and hit us,” Elena said. “First he started with me and ended with my mom.… I think that was one of the reasons that caused her to decide to leave and emigrate.”

When Elena was just two weeks old, her father ordered Ofelia to send their new baby away because of the sound of Elena’s cries. From then on, Elena split her time between her grandmother’s house in Veracruz City and her parents’ home.

In Mexico, a girls’ 15th birthday is a critically important occasion for many families and communities. It’s customary for families to throw an extravagant party, called a quinceañera, to mark a girl’s transition into young adulthood. The parties can involve guest lists, rented halls, decorations, new dresses and suits, expensive flights, and hair and makeup artists.

With Ofelia’s husband unwilling or unable to contribute financially, when Elena was 14, Ofelia told her daughter that she wanted to better provide for her. Ofelia said she would go to the United States to work and save money for Elena’s quince. “’No matter what I have to do, I'm going to make sure your [quinceañera] happens,’” Elena remembers her mother said before Ofelia set out for the US.

When Elena’s 15th birthday came on October 22, she remembers sitting on a piece of furniture outside her grandmother’s house and waiting for hours for her mother. She thought maybe her mom hadn’t been in touch because she wanted to surprise her. But Ofelia never came.

Later, Elena met with a man named Misael, who was among the migrants from her town who returned after failing to reach the US. Misael gave her Ofelia’s identification documents. Misael told Elena that when her mother was first detained in the US, her hair was long and curly, like Elena’s. But the detention center guards shaved her head because Ofelia wouldn’t stop pulling out her own hair because of the stress. Presumably her mother was deported back to Mexico.

Years passed, and Elena eventually migrated to the US. She searched for her mother by word of mouth and on social media to no avail. Eventually someone told her to contact the Colibrí Center for Human Rights. In 2017, staff with Colibrí’s Missing Migrants Program went to New York, where Elena lives, and collected a sample of her DNA to compare with DNA found from people who died crossing the US-Mexico border.

Twenty-one years after her mother disappeared, Elena learned her DNA was a match with that of a human skull found in Webb County, Texas.

Today, Elena is a musician. Like her mother, she has gravitated towards singing.

“I felt that singing was not my thing, but suddenly I took refuge in that, [in] singing,” she said. When she sings, Elena remembers how her mother looked at her with pride and with joy. “That image is the one that I always sing to now. It's the one that I always see in front of me when I'm singing.”

People regularly fall and die or are seriously injured from atop the 18- or 30-foot steel metal bollards constructed under former US President Donald Trump at the US-Mexico border, like the section of barrier pictured here east of Sasabe, Arizona, June 22, 2023. © 2023 Vicki Gaubeca/Human Rights Watch

Rony Eliaquín Escobar Díaz

Rony Eliaquín Escobar Díaz looked up to his older brother, Wagner. He wanted to do everything his brother did: listen to music, watch television, play, go to work. And Wagner, who today lives in Arizona, welcomed his kid-brother’s attention.

Rony went missing on September 3, 2018, after he decided to follow his older brother north across the Sonoran Desert and into the United States. “It wasn't until after a year and a half [after his disappearance] that I started dreaming about him,” Wagner said.

The brothers grew up in Chiapas, a southern Mexican state bordering Guatemala. Wagner studied at a university in Chiapas for a couple of semesters but stopped his studies because he lacked economic support and couldn’t find work. He wanted decent-paying work and a better standard of living, something he said he saw in Hollywood movies, and decided to journey to the US.

When Wagner left Chiapas, Rony was still a small child, so he stayed behind.

Wagner’s trip to Tucson, Arizona, was a harsh and dangerous one, he said, even though he was in good physical shape from working long hours in the mountains of Chiapas. He walked for eight days and nights in the desert with a group of other migrants. He knew he was one wrong move, a bad fall or twisted ankle, away from death. During the last two days, they went without water and food except for one can of tuna and one flour tortilla shared among the group.

A decade later, when Rony was 20 years old, he began making plans to also head north. In September, some boys he knew from town called him to ask if he wanted to cross with them. They were already in Sonora, a Mexican state bordering the US. And just like that, Rony left, traveling through Mexico alone, a nearly 2,000-mile journey that poses serious risks.

Rony made it safely to Sonora and prepared to cross the US-Mexico border near where his brother had crossed.

“You have to be healthy, mentally,” Wagner told Rony over the phone. “You must make a good go of it, decisively, without worrying or something, because that also takes its toll on you. It's not easy to come – for example, if you have problems, your mind is elsewhere, then something bad will for sure happen to you.” Wagner explained the risks. “This is not a game,” Wagner told him.

“Yes, it’s OK, brother,” Rony responded. “We’ll see each other over there.”

They never spoke again.

As the days passed, Wagner and Rony’s other family members started to worry. Rony’s traveling companions provided differing accounts of what happened when Rony was left behind. They said that Border Patrol arrived and scattered the group, and that Rony, who was ill, was lost; or that Rony, sick and tired, simply fell. When Wagner contacted rescue agencies and the Mexican consulate, he felt they ignored him.

Wagner was devastated. He would be in the restaurant kitchen where he worked and feel suddenly as if his heart was stopping. He had to ask for time off work.

Wagner said he prays, asking God where Rony is. “I can't believe a person is lost just like that and disappears into nowhere. That can't be possible.”

Wagner and his family still hold out hope that Rony is alive. From both sides of the US-Mexico border, they say they dream about seeing him smiling and musing, grateful to have seen him somehow. Then they feel the pain of loss all over again as they realize the dreams are not reality.

“I asked God to give me those dreams,” Wagner said. “I wish that this dream would last forever and continue. Like a lifetime.”

Rosita L.

“How is it possible that I have come to see her for the last time, and she is nothing but bones, when I have waited for her with so much love?” Rosa asked when the body of her niece, Rosita L., was finally found.

Rosita was like a daughter to Rosa. The 19-year-old grew up in Tabasco, a southern Mexican state, in a little coastal town. Her father worked as a fisherman and her mother sold tamales and tortillas in the street, but the town had few opportunities for young people. Both of Rosita’s parents suffered from chronic illnesses. Rosita wanted to join her aunts, Rosa and Lili, in the United States to work to cover her parents’ medical expenses. Her aunts are both legal permanent residents.

In April 2021, Rosita decided to make the journey with a neighbor and a cousin. They agreed to pay a smuggler US$7,500 to guide them.

In June, Rosita crossed the border into South Texas with a group of people, including her cousin. When the group arrived in Odessa, Texas, three days later, Rosita was not with them. “It’s just that she couldn’t stand walking anymore and so she stayed [behind],” Rosita’s cousin said. “She said that she was going to turn herself in to immigration.”

The aunts started calling Border Patrol, providing the approximate location for where their niece was last seen and asking if they would go find her. When Border Patrol answered, they said they would look later or that they had already looked. Dozens of calls and visits to the Mexican consulate also proved fruitless. It would take a local sheriff, who picked up the phone when Rosita’s aunts called, going above and beyond to track down Rosita’s remains.

“Here in Texas, no one is going to help, ma’am,” Rosa remembers the sheriff saying. “That Border Patrol told you they were going to look for her, that is a lie. They don’t do it. . .The body was found because a rancher alerted us that the body was there. When did [Border Patrol] go to pick it up? Not until they got around to feeling like it.”

Lili and Rosa believe that if the Border Patrol had searched, agents may have found their niece alive.

Before her remains were found, the aunts traveled twice to Odessa, Texas, based on false sightings of their niece. They called or visited the Mexican consulate daily. They posted on Facebook and other social media. And they called organizations performing search and rescue at the border.

People tried to take advantage of their situation. On eight occasions, they received calls from people claiming they had kidnapped Rosita and demanding ransom. The scammers sent doctored photographs using Rosita’s face from the missing person posts on Facebook.

The sheriff spoke with the neighbor who had traveled with Rosita to find the exact location where she’d stayed behind. “He communicated with me daily,” Rosa said. “That sheriff was an angel looking for Rosita.”

The sheriff learned from county officials that they had indeed picked up Rosita’s remains, which had been taken to Texas State University, as the county morgue was full. The aunts would have to tell Rosita’s mother that she was dead. Rosa coordinated with the Colibrí Center for Human Rights to travel to Tabasco to collect DNA from Rosita’s mother. Their DNA was a match.

Lili and Rosa went to San Marcos, Texas, to see Rosita’s remains. The coroner welcomed them and explained that they had tried to respect and care for the remains of their niece. She also gave the aunts Rosita’s belongings.

“The only thing I can tell you is that my niece is fine,” Lili said. “Wherever God has her, she is good. Because even though she has experienced something very difficult, when I entered [the room] I felt that peace, that tranquility.”

Now, all the family have are memories, photos, and an altar in the house where Rosita grew up. Her little brother pours her a cup of Coca-Cola at mealtime and leaves it at the altar, along with her favorite pastry.

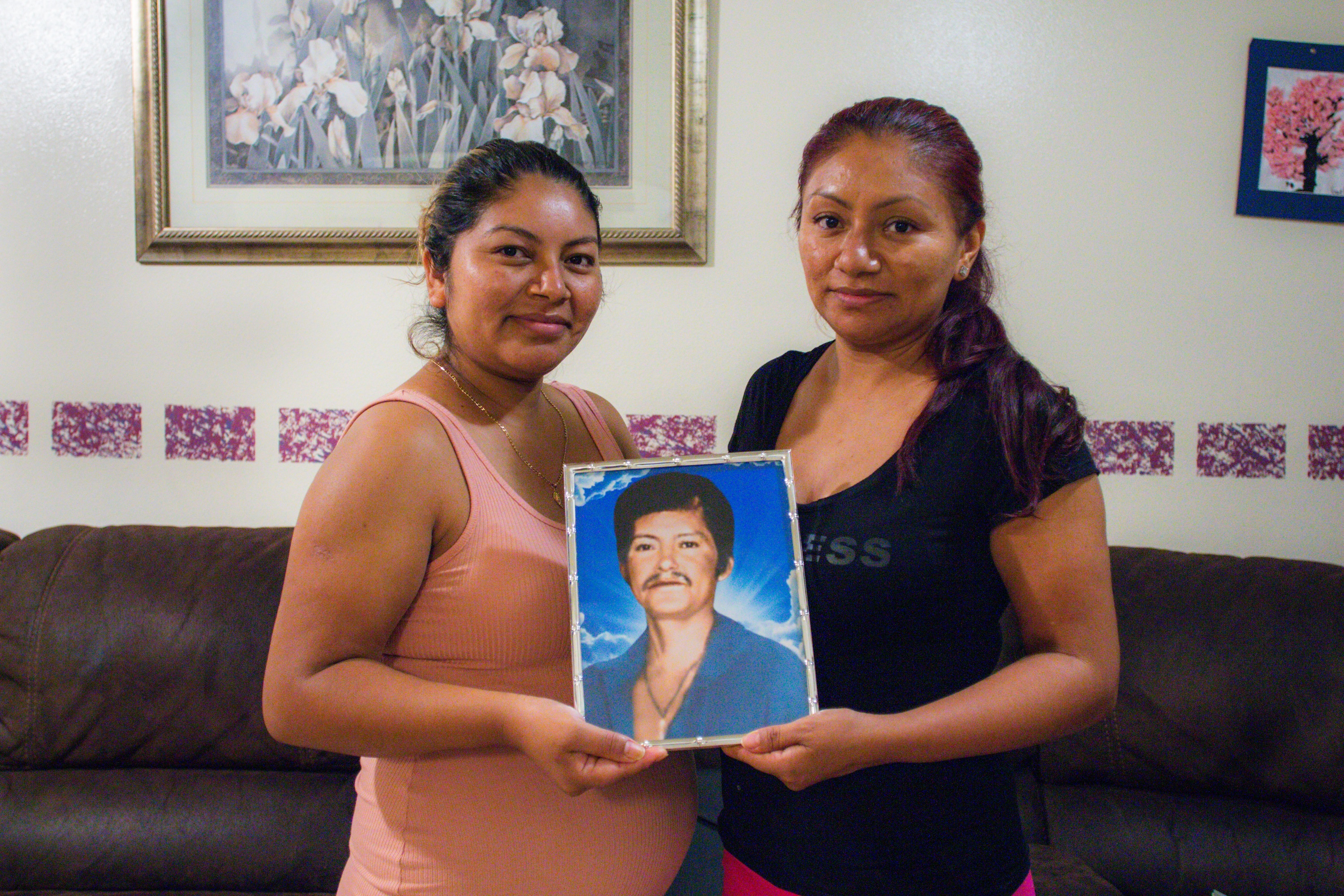

Gualberto Bernal Villanueva

The best bread in the neighborhood could once be found at the bakery Gualberto Bernal Villanueva ran out of his home in Acapulco, Mexico. He sold out almost every day, selling donuts, bolillos, and conchas, among other sweet and savory treats. The bread was so good that the family used it as currency, trading it for other necessities sold by their neighbors.

One of his three daughters, María, used to help him in the kitchen. "He never wrote down any recipe or anything like that,” she said. “In fact, he had it all in his head.”

Those recipes are lost now.

For more than 15 years, Gualberto’s children have wondered if their father is alive or dead. “It’s like we’re never going to have answers,” María said.

Gualberto decided to cross the desert to accompany his youngest daughter, Tania, on the journey after the person who was supposed to accompany her backed out. He planned to join his three older children who were already living in Los Angeles.

The siblings were apprehensive about their father’s arrival. They hadn’t seen him in a long time, and he hadn’t always been the easiest person to get along with—his daughters María, Yesenia, and Tania remember him being a rigid disciplinarian and not allowing the girls out of the house much or permitting them to see their boyfriends without their parents and siblings chaperoning.

On June 2, 2007, after walking three days and three nights through the Sonoran Desert, Gualberto and Tania crossed the US-Mexico border and were in Arizona, just a 5-minute walk from the highway near Nogales and Tucson, along with a large group of migrants. It was Gualberto’s birthday.

The smugglers split the group into two, Tania in one and Gualberto in another. Tania’s group walked about 10 feet ahead.

“I turned around because he wasn’t that far behind me, and [saw] he was coming,” Tania said. “My dad was in perfect condition.” Five minutes later, Tania turned to look again, and he was gone.

“I tried helplessly to go back to look for him, but they wouldn't let me,” she said. A friend of her father’s traveling in the second group said Gualberto ran off after someone hit him. “From then on, I never saw my dad again,” Tania said.

Not long after, Tania was apprehended and detained by Border Patrol agents. She told agents her father had gone missing. The agents said they would look, but since then have refused to answer further requests for information.

Because the siblings did not have legal status in the United States, they were afraid to ask US authorities for help. A friend went to the Mexican consulates in Tucson and Yuma, Arizona, and they went themselves to the Mexican consulate in Los Angeles. They never heard back. The only people to call the family were scammers who claimed to hold Gualberto captive. They asked for US$3,000. But when they refused to let one of Gualberto’s daughters, Yesenia, speak to him, she refused to pay.

“It’s a fraud,” Yesenia said. “It's sad for the families, because you don't know if they really [have your loved one].”

To prevent more deaths, the United States should end deterrence policies and create more safe and legal pathways to migrate, as well as humane processing for new arrivals. The government should also increase funding for more search, rescue, and recovery efforts. When the US government regulates migration, it needs to do so in a manner respectful of human rights—including the right to life, which should be paramount in border and immigration policies.

Residents in Eagle Pass, Texas, hold a vigil on September 4, 2023, to commemorate the people who have died trying to cross the border while swimming across the Rio Grande.

This feature was written and researched by Ari Sawyer. Interviews with families were conducted by Perla Torres from the Colibrí Center. The website was designed by Maggie Svoboda. We thank the families for sharing their grief and their love with us.