Heidi’s mother and other family members gather at her grave to mark what would have been her fifth birthday, September 25, 2022. © 2022 Nuevo Laredo Human Rights Committee

Four-year-old Heidi Pérez had a stomachache. “My tummy hurts,” she told her mother, Cristina, who comforted Heidi, as she had so many times before. If her stomach still hurt later, Cristina promised that her step-grandmother, Griselda, who often cared for Heidi while Cristina was working, would give her medicine.

Cristina herself wouldn’t be home until late. She had a night shift as a medical assistant at General Hospital 11 in Nuevo Laredo, the tiny city where they lived, in Tamaulipas state, on Mexico's United States border.

It was August 31, 2022, and it would be the last time Cristina saw her daughter. Heidi would die later that night at her mother’s hospital from a bullet to the head.

Human Rights Watch reviewed the official investigation into Heidi’s death, in partnership with Nuevo Laredo Human Rights Committee, a local advocacy organization. We found serious flaws and omissions in the investigation and identified new evidence about soldiers’ possible role in Heidi’s death.

At around 10 p.m. that night, Cristina received a phone call from her father: Heidi’s stomach still hurt, and they were worried. They wanted to bring her in for an x-ray, just to be safe. Griselda would drive.

Griselda put Heidi and her older brother in her gray Chevrolet Cobalt and headed for the hospital.

At around 10:23 p.m., Griselda approached an intersection a few blocks from their house. She says she saw military vehicles blocking the street ahead. As a long-time resident of Nuevo Laredo, she was concerned but not surprised.

Military vehicles are a common sight on the streets of Nuevo Laredo. The military has been deployed for decades across Mexico to fight drug cartels. Few places have been more affected than Nuevo Laredo. Of the 5,755 military shootouts that the Mexican Army reported from 2007-2023, nearly 700 of them were in Nuevo Laredo, more than any other city, state or municipality in the country.

Griselda turned right to avoid the soldiers. Seconds later, she heard gunshots hitting the car, and she felt a burning in her right arm. As she accelerated to flee, she heard Heidi’s brother cry out, “They killed my sister! My sister is dead!”

Griselda stopped the car and looked into the backseat. Heidi’s older brother was holding her in his arms, as she bled from the head. Griselda moved Heidi to the front seat and called Cristina’s father, in a panic. “They shot her,” he told Cristina in a phone call soon after.

Griselda raced to General Hospital 11, using one hand to steer the car and the other to prop Heidi upright as she bled in the passenger seat.

Minutes later Griselda ran into the hospital, covered in blood. “She’s bleeding!” she shouted, cradling Heidi’s limp body, the girl’s wavy dark hair matted around a massive trauma to the left side of her skull.

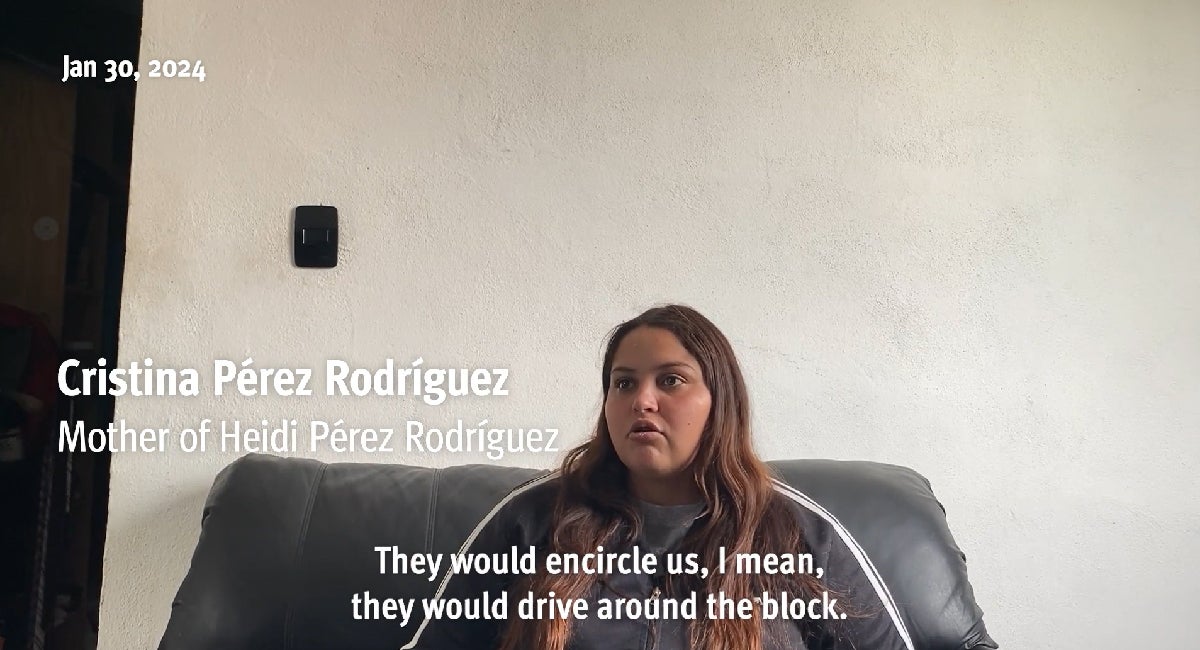

Doctors whisked Heidi off to the pediatric emergency ward, telling Cristina to wait outside. She went to look for Griselda, to ask her what happened. Griselda could barely respond. “She just kept repeating, ‘They shot us. The soldiers shot us.’ I didn’t understand what was going on,” Cristina said.

Minutes later, a doctor approached Cristina and asked her to come into the operating room. The doctor explained that Heidi had been killed by a bullet to the head. It was 10:37 p.m.

The next morning, Cristina went to the prosecutor’s office to make a formal statement. “It was awful,” she recalled. “I was giving my declaration when the soldiers arrived. And right in front of me, they were saying ‘No. We weren’t there.’” She felt powerless. “There were five of them. I was surrounded with no support from anyone and I felt they were ignoring me.”

That day, Cristina reached out for help to a local human rights group, the Nuevo Laredo Human Rights Committee. The group, which provides legal representation for the victims of military abuses, reports having documented at least 18 cases of rights violations linked to the military in Nuevo Laredo since 2018. Raymundo Ramos, the Committee’s president and a longtime human rights advocate, has faced state harassment and surveillance for his investigations into the military in Nuevo Laredo.

At the funeral two days after Heidi died, Cristina told reporters, “She didn’t do anything wrong in this world. She came here to bring us joy. For her and for her brother who is suffering dearly, I demand—and I want—justice.”

But two years later, Heidi’s family is still waiting for justice.

The Mexican government says a stray bullet from a shootout between soldiers and armed criminals killed Heidi. Then-President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, in his morning press conference five days after her death, said that the Defense Ministry had already investigated and those responsible would be held accountable.

Just days earlier, his party had introduced a constitutional reform to give the military permanent control over federal law enforcement. He faced sharp criticism from Mexican and international human rights groups, including Human Rights Watch, who pointed to the military’s long history of abuses against civilians, including extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances that are rarely, if ever, investigated. As a candidate, López Obrador had promised to end military policing, and send the soldiers back to the barracks. Once elected, he changed his tune, arguing that the military abuses were a thing of the past, and that soldiers now fully respect human rights.

The facts tell a different story. Since López Obrador took office in December 2018, the Army has reported killing more than 1,000 civilians—185 of them in Nuevo Laredo. While authorities usually claim civilian deaths are related to armed confrontations with criminal groups, these killings are rarely independently investigated. According to leaked Defense Ministry emails obtained by journalists in 2022, just 147 criminal cases were opened against soldiers for human rights violations from 2007 to 2021. Human rights groups and journalists have documented dozens of cases in which soldiers apparently fired at unarmed people, including many in Nuevo Laredo. The Nuevo Laredo Human Rights Committee reports that, of the 18 cases of human rights violations involving the military it has documented since 2018, just two have made it to trial.

Military Pressure to Stay Silent

On the day of Heidi’s funeral, a Defense Ministry official asked the family for a meeting. Cristina’s cousin responded, asking the official to give the family time to mourn. A few days later, the official called again. This time, Cristina, who happened to be at a restaurant meeting with lawyers from Nuevo Laredo Human Rights Committee when she received the call, agreed to meet, and asked the official to come to the restaurant. When the official arrived, he seemed put off to see Cristina’s lawyers were there. “The moment he saw I wasn’t alone, he turned around and walked out the door. So, I sent him a message asking why he had left and he came back to the table,” she said.

The official told Cristina that the Defense Ministry could provide “support” if the family agreed to stop speaking publicly of Heidi’s death. It is a tactic Mexico’s military has used for years to avoid accountability for abuses. The official told Cristina that if she wanted to discuss the agreement further, it would be better to meet privately, without lawyers.

Cristina interpreted the official’s offer of “support” to mean money. She refused.

In the weeks after the meeting, soldiers began following Cristina and her family around Nuevo Laredo. She says they would appear outside the home at night, or in the vacant lot next door, looking in the Pérez family’s windows. On one occasion, military trucks surrounded Cristina’s brother’s car. The whole family was afraid. “You go everywhere and they’re there, and you don’t know why they’re there. Like as if we were criminals and they’re watching us,” Cristina said. “We couldn’t even go out to the store.”

A week after Heidi’s death, the National Human Rights Commission, a government human rights body, instructed the Army to prevent soldiers from contacting Cristina or going to her home. But the harassment did not stop, she told Human Rights Watch. In October, Cristina and her mother went to the federal attorney general’s office to ask for a restraining order to prevent further harassment. Prosecutors, in a letter to the commander of the military garrison, asked him to order soldiers to stop driving down Cristina’s street. “They didn’t listen to us,” Cristina said. “So, I asked myself: what am I doing here?” Eventually, she felt she had no choice but to leave Nuevo Laredo.

Cristina’s experience is not uncommon. The Defense Ministry’s Citizen Liaison Unit (Unidad de Vinculación Ciudadana) often offers financial compensation to families of people killed or injured by soldiers. In 2009 and 2010, Human Rights Watch documented more than a dozen cases of likely extrajudicial killings after which the military had pressured families to accept compensation in exchange for abandoning pursuit of a criminal investigation. In many cases, families who refused to sign the agreements reported suffering military harassment. This practice has continued. From 2010 to 2022, journalists found more than 230 such agreements between the Defense Ministry and victims’ families. The Defense Ministry refused a Human Rights Watch request for information on 2023 agreements.

Cristina told Human Rights Watch she doesn’t want Heidi’s death to be swept aside like so many other cases. “I don’t want money,” Cristina said. “I want them to investigate… to do their job correctly.”

Serious Omissions in the Investigation

It was the Tamaulipas state prosecutor’s office that initiated the investigation, but the federal attorney general’s office took it over in September 2022. As of August 2024—two years later— no suspects have been identified.

The attorney general’s office told Heidi’s family and their lawyers, in early 2023, that they intended to send the case back to the Tamaulipas state prosecutor's office due to a lack of evidence involving the military. That’s when Human Rights Watch researchers began reviewing thousands of pages of the criminal investigation file, including witness statements, forensic studies, and photographs of the crime scene, vehicles, ammunition, and of Heidi and Griselda’s wounds.

We met with Heidi’s family and her lawyers and travelled to Nuevo Laredo to visit the scene of the shooting and examine the car in which Heidi was riding. We also reviewed security camera footage from the night Heidi was killed, consulted with independent forensic and ballistics experts, and reviewed satellite imagery and open-source imagery to piece together the events of August 31, 2022.

We found serious errors and omissions in the investigation—and little reliable evidence to support the government’s claim that Heidi was killed in a confrontation between soldiers and armed criminals. We found worrying irregularities in the evidence that soldiers presented to support this version of events. We also identified inconsistencies between the Defense Ministry’s version and video evidence from the night of the killing.

We found little evidence that prosecutors had taken sufficient steps to verify the military’s claims or corroborate soldiers’ testimony about the night of Heidi’s killing.

Dubious Evidence of Shootout with Armed Criminals

The Mexican government says Heidi was killed in a shootout, when criminals opened fire against a military convoy. In a letter to Human Rights Watch, on May 21, 2024, the Defense Ministry denied wrongdoing, saying the “military did not violate human rights.”

Heidi’s family, and lawyers from the Nuevo Laredo Human Rights Committee, say that Defense Ministry officials and prosecutors have told them in private that they believe Heidi was killed by unidentified armed people—not by soldiers. But evidence that armed people fired at soldiers or were involved in Heidi’s death is weak and unreliable, Human Rights Watch found. Prosecutors have taken few steps to verify this version of events, and we found no indication that they had attempted to identify the supposed armed criminals.

The Military’s Version of Events

Around two hours after Heidi was killed, the commanders of two military convoys (of three vehicles each), which we will call Convoy One and Convoy Two, filed official reports with the federal attorney general’s office in Nuevo Laredo. Over the following two days, many of the soldiers gave witness statements to prosecutors. Neither the reports nor the testimony mentioned Heidi’s killing.

In the report and testimony, soldiers from Convoy One said that, while driving through the area at around the time Heidi was shot, they had encountered a suspicious looking vehicle—a gray SUV driven by men in military helmets. The SUV was three blocks from the corner where Heidi was shot. When they tried to pursue it, they said, a second vehicle—a black pickup truck—appeared. Its passengers fired at them and fled, they said. The soldiers fired back in self-defense, they said, although they did not fire at the pickup, but at the gray SUV, which also fled. The soldiers then radioed their base to request assistance.

Human Rights Watch reviewed video evidence from a security camera four blocks away that appeared to show gunshots coming from the direction of the soldiers. An investigator from the attorney general’s office who reviewed dashboard camera video from one of the military vehicles also reported seeing a gray SUV and flashes, at the moment the soldiers said they fired their weapons. But the investigator did not report seeing a black pickup. Nor did he report seeing anyone fire at the soldiers. In fact, beyond the soldiers’ testimony, we found no evidence in the case file to suggest that a black pickup was present at the time the soldiers fired their weapons.

The Nuevo Laredo emergency services office told prosecutors, in a letter Human Rights Watch reviewed, that it received no reports of armed people, attacks, or shootings in downtown Nuevo Laredo on the night Heidi was killed. And investigators who inspected the location the following day found no bullet casings, damage to buildings, or evidence of a shootout, except a street sign with a hole in it, according to their crime scene inspection report. It is not clear when the bullet damage occurred or whether it had anything to do with the night’s events.

Likewise, investigators who inspected the military vehicles reported finding a crack, possibly caused by a bullet, in the glass of one vehicle’s machine gun turret. But they recorded no evidence of the crack’s age.

Prosecutors obtained evidence, some of it provided directly by soldiers, to support the claim that armed criminals in a black pickup fired at them. But the evidence is seriously flawed.

An Anonymous Witness and a Suspicious Bullet Casing

Investigators initially reported finding no evidence of a shootout when they inspected the crime scene on September 1st. But on September 4th, they filed a report saying that an anonymous witness had come forward to give them a bullet casing that she said she had found on the ground at the scene of the alleged shootout. The witness reportedly said that a municipal cleaning crew had come that morning and removed all other evidence before crime scene investigators arrived.

Prosecutors waited two months before attempting to corroborate the witness’s story, and only did so after Heidi’s family’s lawyers requested it. In a letter Human Rights Watch reviewed, city officials said that no cleaning crew had been assigned to the area that day.

The Black Pickup Truck

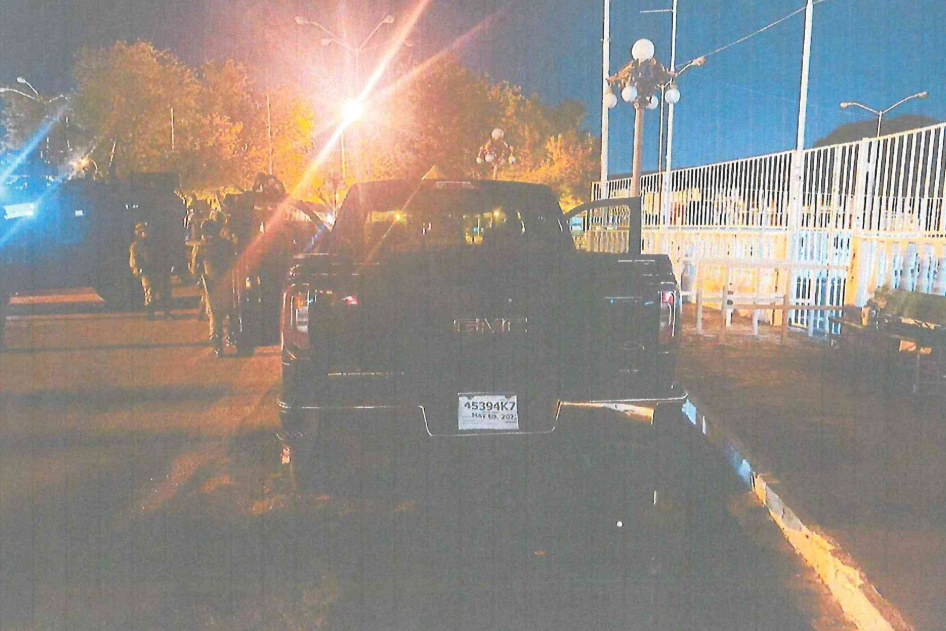

When the soldiers reported the shooting, they brought prosecutors a black pickup truck that they said matched the description of the vehicle that had fired at them. They also brought a loaded plastic ammunition magazine that they said they had found on the driver’s seat.

The soldiers’ narrative of finding and securing the truck reveals a number of inconsistencies. They told prosecutors that soldiers from Convoy Two were resting at their base when they received Convoy One’s call for help. Convoy Two immediately deployed to search for the two vehicles: the gray SUV and the black pickup. But instead of driving to the scene of the supposed shooting, they drove directly to the other side of the city, onto a fairground about three miles from their base and a mile from the scene. They said they immediately found the black pickup abandoned, with its keys in the ignition, doors open, lights on, and a loaded ammunition magazine on the driver’s seat.

Under Mexican law, national protocols, and international standards, law enforcement officials should attempt to preserve or record the location and condition of all evidence related to a criminal case. The idea is to ensure that the evidence has not been fabricated or altered and, if possible, to make a written or video record of any inspection of it. Such procedures are essential to guaranteeing access to justice—and the right to a remedy and reparation—for victims of crime. Instead of taking these steps, the soldiers said they simply drove the black pickup from the fairground to the local branch of the attorney general’s office.

Soldiers gave prosecutors conflicting information about where and how they found the pickup. In the initial police report, soldiers provided GPS coordinates for the spot where they said they had found the pickup, at the northeastern edge of the fairground, near the corner of Calle Nezahualcóyotl and Calle J. F. de La Garza. They said they found the pickup next to a bar.

In their testimony to prosecutors over the following two days, soldiers said they had found the pickup inside the fairground. One soldier said the pickup was found next to the city theatre, which is on the northwest corner of the fairground.

At the request of the lawyer for Heidi’s family, prosecutors sent the military a letter asking them to clarify how and where they found the pickup, ammunition, and magazine, and to provide photographic evidence of the location and condition in which they were found. The military replied providing prosecutors with a map of the route that Convoy Two had taken to reach the fairground and photographs of the pickup.

Human Rights Watch geolocated the photographs of the pickup and determined they were taken at the center of the fairground, around 160 yards southwest of the GPS coordinates initially provided by the military and around 200 yards east of the theatre. The photographs show the truck with its doors open surrounded by soldiers. It is not clear where or how the truck was initially found or whether soldiers moved or examined it before photographing it.

The military also provided a separate photograph showing a magazine and ammunition lying on top of what appears to be a tiled surface, not in the pickup, raising questions about whether the ammunition and magazine were found in the truck as soldiers claimed.

Failure to Corroborate Military’s Version of Events

Prosecutors investigating Heidi’s killing have failed to take many of the basic steps needed to corroborate the military’s version of events. They appear to have taken the military’s statements at face value.

In the two days following Heidi’s death, prosecutors took voluntary witness statements from 38 soldiers of Convoy One (which reported the shootout) and Convoy Two (which reported discovering the black pickup). The statements do not mention Heidi’s death, and there is no record that prosecutors asked any questions about it. Nor did they ask soldiers from Convoy Two why they drove to the other side of the city instead of to the reported scene of the shootout.

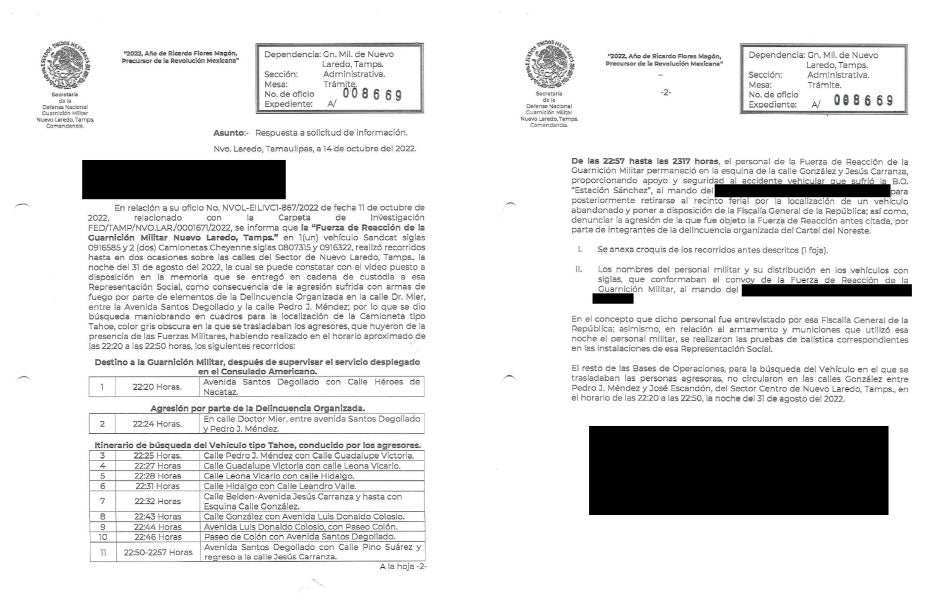

Prosecutors took limited steps to verify the location of Convoy One at the time of Heidi’s killing. They sent letters to the Army asking for written itineraries of the convoys between 10:20 and 10:50 that night. One investigator from the attorney general’s office downloaded the Google location history from the cell phone of the commander of Convoy One. Another reviewed the dashboard camera footage from a Convoy One vehicle; he did not report seeing images of a black pickup.

There is no record in the case file that prosecutors tried to verify the testimony of the soldiers from Convoy Two, who reported that they had found the black pickup and the ammunition magazine at the fairground. In fact, prosecutors took no steps to identify the supposed shooters, to confirm whether the black pickup had been at the scene of Heidi’s death, or to determine how the truck might have gotten from the scene of the shooting to the fairground. They found clothes and personal items inside the truck, but there is no record that they attempted to use these to identify the supposed shooters. There is no record that they tried to obtain fingerprints from the truck or its contents, including the cartridge magazine. There is no indication that prosecutors ever asked the soldiers from Convoy Two why, if they were responding to the shooting, they drove to a different location. In March 2023, prosecutors handed over the black pickup to US officials, who said it had been reported as stolen in the United States.

Failure to Investigate Evidence of Additional Military Convoys

Human Rights Watch found evidence, including new evidence from previously unseen security camera videos, indicating there may have been at least two additional military convoys (of three vehicles each) present downtown before and after the time Heidi was killed. However, prosecutors have taken extremely limited steps to investigate these convoys or determine their whereabouts at the time of Heidi’s killing.

The Army Mentions a Third Convoy

On October 14, six weeks after Heidi died, the Army informed prosecutors that a third military convoy, which we will call Convoy Three, had been in downtown Nuevo Laredo shortly after the killing. In a letter, the commander of the Nuevo Laredo Military Garrison told prosecutors that Convoy One, which had reportedly been searching downtown for the gray SUV and black pickup, stopped to assist Convoy Three, one of whose vehicles had been involved in a traffic accident at around 11:00 pm—thirty minutes after Heidi was shot. None of the soldiers had previously mentioned to prosecutors a third convoy.

At the request of the lawyers of Heidi’s family, prosecutors requested additional information from the Army. The garrison commander replied with a written itinerary of Convoy Three’s location in the minutes leading up to the traffic accident. At the time of Heidi’s killing, it placed the convoy on the outskirts of the city.

Prosecutors confirmed the traffic accident with transit police. But they took no steps to verify Convoy Three’s location half an hour earlier, when Heidi was shot. Nor did they question any soldiers from Convoy Three about their whereabouts or examine their weapons to determine if they had been fired.

Possible Fourth and Fifth Convoys Seen on Security Camera Videos

Human Rights Watch reviewed and geolocated security camera videos from two places downtown. The videos show military units at places and times not consistent with the information that the Army provided to prosecutors. The videos, described below, suggest that, in addition to Convoy One and Convoy Three, there may have been two other military convoys downtown immediately before and after Heidi’s shooting.

Video One: from Intersection of Calle González and Calle Pedro J. Méndez

On September 21, three weeks after the killing, lawyers of Heidi’s family provided prosecutors with security camera videos they had obtained from a business on Calle González.

Human Rights Watch reviewed the videos and confirmed that they show the corner of Calle Pedro J. Méndez and Calle González the night of August 31. That is two blocks from where Heidi was killed and three blocks from the intersection where Convoy Three reported one of its vehicles, a pickup truck, had been involved in an accident with a Chevrolet Cruze that had reportedly run a red light. The videos show at least six military vehicles driving through the area, only three of which were identified in the investigation.

At one point, an unidentified convoy of three military vehicles can be seen driving north on Calle Pedro J. Méndez and turning left to drive west on Calle González, toward the scene of the reported traffic accident. This does not match the route or vehicle description of any of the convoys identified in the case, since Convoy Three reported it was coming from the opposite direction on Calle González when it was involved in the traffic accident and Convoy Two reported that it was never downtown.

Immediately afterwards, a convoy of two pickup trucks with machine guns mounted on a turret in their bed and one armored vehicle can be seen driving west to east on Calle González, away from the location of the reported traffic accident and toward the security camera. The vehicles stop in front of the security camera, and soldiers in one of the pickups shine their flashlights at it before moving off the screen. A minute later, light, seemingly from a flashlight off camera, appears to turn around traffic on the street.

Prosecutors wrote to the Army asking if any military units had been deployed on Calle González between 10:20 and 10:50 that night. The Army said that Convoy One had been there. They did not mention that the vehicles had stopped to examine the security camera or that they had redirected traffic on the street, as seen on the video.

Nor did the Army mention a second military convoy in the area. Prosecutors did not ask for additional information about the three unidentified military vehicles that can be seen driving north on Calle Pedro J. Méndez and turning left to drive west on Calle González.

Video Two: from Intersection of Calle Pino Suárez and Calle Santos Degollado

Human Rights Watch reviewed security camera videos from a business near the corner of Calle Pino Suárez and Calle Santos Degollado, about three blocks from where Heidi was killed. They show a military convoy consisting of three mounted pickup trucks driving north on Calle Santos Degollado, at what the security camera timestamp records as 10:05 on the night of the shooting.

The convoy does not match the description of any of the three mentioned in the case file, all of which contained a mix of armored vehicles and machine gun armed pickup trucks. The Army has reported that all three of the convoys mentioned in the case file were elsewhere at the time. The video indicates that there may have been another convoy downtown immediately before Heidi’s death and four blocks from the scene of the shooting.

Failure to Adequately Test Soldiers’ Weapons

Mexico’s Defense Ministry told Human Rights Watch, in a May 21, 2024, letter, that it had concluded that military personnel were not involved in Heidi’s death because the ballistics studies conducted by prosecutors “determine[d] that the impacts that killed [Heidi] did not originate from a weapon under the control of military personnel.” That is not true.

When Human Rights Watch reviewed the ballistics studies, we found that prosecutors only examined the weapons carried by soldiers in Convoy One, not those carried by soldiers in Convoys Two and Three or by the soldiers in the other unidentified military convoy seen in the security camera videos.

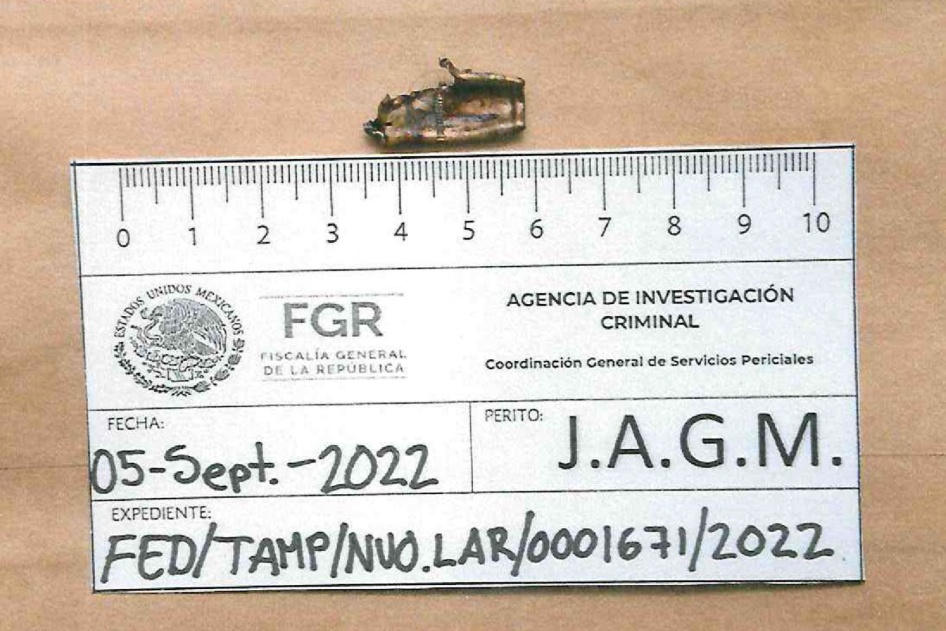

We also found that the studies show a possible but inconclusive match between the bullet that killed Heidi and one of the weapons fired by a soldier that night. We consulted two independent forensics experts, who reviewed the ballistics studies and concluded that prosecutors had not taken sufficient steps to determine whether the bullet and the weapon matched.

When forensic investigators from the attorney general’s office examined Griselda’s car, they recovered a deformed, fired bullet. They determined, through DNA testing, that it was the bullet that had killed Heidi. Ballistics technicians from the attorney general’s office determined that the bullet’s caliber was 7.62 millimeters, the same caliber as bullets for eight of the weapons carried by soldiers in the three convoys that were deployed on the night Heidi was killed: two G3 battle rifles and two Minimi mounted machine guns carried by Convoy One, and four Minimi mounted machine guns carried by the Convoys Two and Three. One of the Minimi machine guns was among the weapons that soldiers said they had fired in the reported shootout.

Investigators sent the deformed bullet recovered from Griselda’s car to ballistics technicians who tested it against sample bullets shot from 24 weapons belonging to 21 soldiers from Convoy One, including from 4 of the 8 weapons that fired 7.62mm bullets. They found no match between the bullet and 23 of the weapons and a possible but inconclusive match with the Minimi machine gun that had reportedly been fired during the shootout.

The independent forensics experts Human Rights Watch consulted said that when ballistics examiners obtain an inconclusive result, they typically conduct further testing. For example, the US government’s guidelines for ballistics examiners recommend firing additional sample bullets from the weapon being tested or applying magnesium smoke to enhance details on the bullet. But the ballistics technicians from the attorney general’s office did not report taking such steps or conducting any further testing on the bullet or weapon. Nor did they test any weapons from Convoys Two and Three.

Heidi’s Family Continues to Demand Justice

Cristina no longer lives in Nuevo Laredo. She felt moving to another city was the only way to protect her family from military harassment. The transition has been difficult. Cristina has struggled to find steady work as a medical assistant.

Two years after Heidi’s death, Cristina continues to demand accountability, despite the official pressure to move on. Heidi’s absence is excruciating for her. “It is very hard for me to battle and live with this pain...day in and day out,” Cristina told Human Rights Watch.

In August, we wrote Mexican Attorney General Alejandro Gertz Manero explaining our concerns about the omissions and irregularities in the investigation of Heidi’s killing. We urged federal prosecutors to take steps to ensure that those responsible for the killing are identified and brought to justice. As of publication, we had received no reply.

Heidi’s death, and the error-filled official response, offer an in-depth look at the myriad ways Mexicans’ security and justice institutions have failed them. It has been nearly two decades since the Mexican government first began deploying soldiers domestically for public security. Since then, military abuses have become commonplace, rates of violent crime have skyrocketed, and prosecutors have proven themselves almost entirely incapable of ensuring justice for victims and their families.

Like thousands of other parents, Cristina continues to demand justice and accountability. Her message for authorities: “You can offer me all the money you want, but I’ll still be here. I won’t be quiet. I don’t want money. I want you to do your job.”

This feature was written and researched by Sophia Jones, Human Rights Watch digital investigations researcher, and an Americas researcher, with the assistance of the staff of Nuevo Laredo Human Rights Committee. Travis Carr designed the website. Ellie Kealey edited the video interviews. Léo Martine, Ivana Vasic, and Christina Rutherford created the maps.

James Lin, of the International Council for the Rehabilitation of Torture Victims, and Carlos Eduardo Valdés Moreno, former director of the Colombian National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences provided external review of the ballistics studies and medical reports.

Human Rights Watch thanks Samuel Storr and Ernesto López Portillo of the Citizens’ Security Program of the Universidad Iberoamericana, in Mexico City, for allowing us to recreate their map of military shootouts.

Human Rights Watch thanks Cristina Pérez and her family for sharing their story and the members of the Nuevo Laredo Human Rights Committee for their tireless efforts to pursue justice for the victims of military abuses in Mexico.