“Where is the Justice?”*

Interethnic Violence in Southern Kyrgyzstan and its Aftermath

* Writing on posters held up by Uzbek women protesting abuse by security forces outside the house of 20-year-old Khairullo Amanbaev, who died from injuries sustained in police custody.

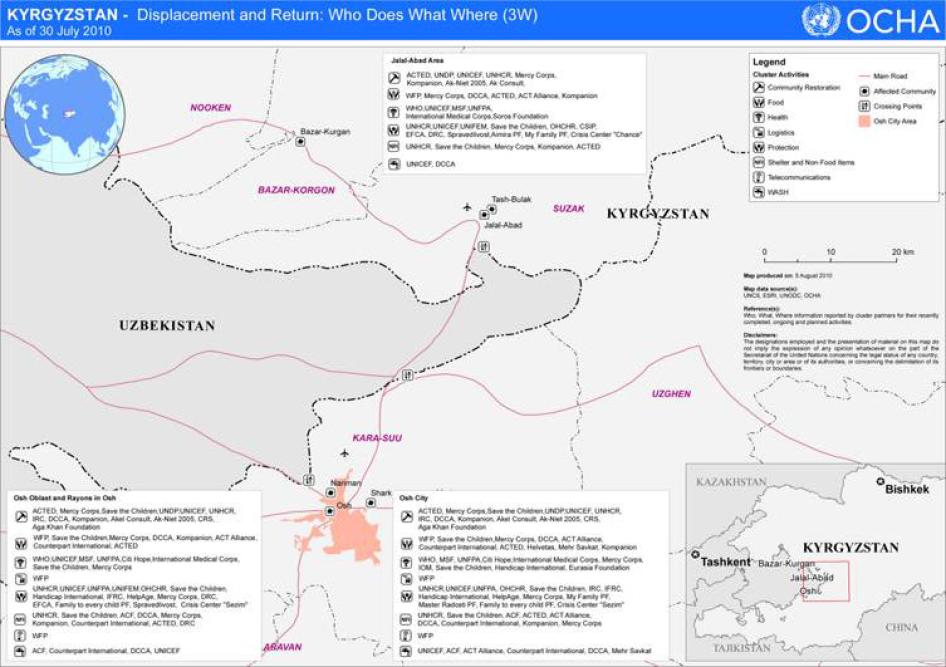

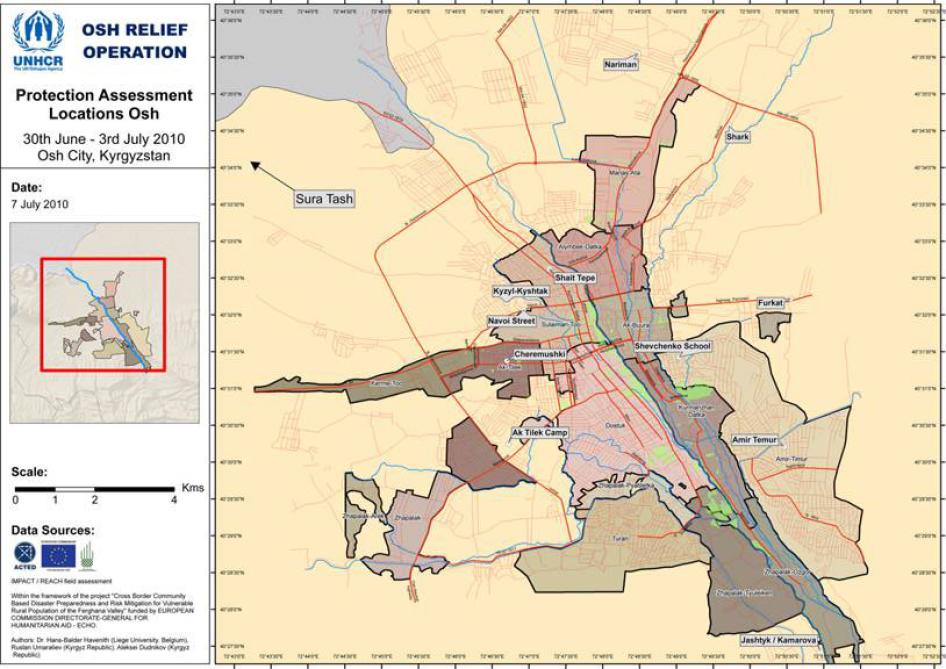

Maps

Summary

From June 10 to 14, 2010, ethnic violence engulfed southern Kyrgyzstan, claiming hundreds of lives and resulting in massive destruction of property. To this day, the situation in the region remains volatile, with tensions high between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks. The two communities are separated by mutual mistrust and anger, while local law enforcement authorities continue to carry out arbitrary arrests, mistreating witnesses and suspects, mainly ethnic Uzbeks.

Human Rights Watch has conducted an extensive, on-the-ground investigation into the violence and its aftermath, from June 10 to July 25, 2010. This report is based on over 200 interviews with Kyrgyz and Uzbek victims and witnesses, lawyers, human rights defenders, and community activists, as well as local government officials, law enforcement and military personnel, and military and civilian prosecutors.

The report recreates the chronology of the June violence, and analyzes the role of the Kyrgyz security forces in the events, including the enormous challenges they faced coping with the violence, allegations of their failure to prevent and stop the bloodshed and allegations of their direct involvement in it. It further examines patterns of arbitrary arrests, ill-treatment, torture in custody, and other violations of due process rights during the government’s investigation into the June events, and documents continued interethnic violence and the authorities’ failure to respond adequately to it.

Mayhem in Southern Kyrgyzstan June 10-14

Ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks have generally lived peacefully together in southern Kyrgyzstan, in many cases inter-marrying and living in ethnically mixed areas. Yet disputes over land distribution and grievances about unequal access to economic and political power have simmered below the surface—traditionally ethnic Uzbeks have been underrepresented in the public sector, but have played a significant role in the private sector. In 1990, disputes over land distribution erupted in violence that killed at least 300 people.

When demonstrators ousted President Kurmanbek Bakiyev in a violent uprising in April 2010, the subsequent political turmoil and jockeying for power brought these grievances to the fore. In need of political support, the interim government appealed to the traditionally apolitical Uzbek community, which became emboldened by playing the role of power broker and put forward demands for greater political power. The prospect of increased Uzbek participation in politics angered many Kyrgyz, and in late April and May the two groups locked into a spiral of increasing tensions.

The massive wave of violence began when a large crowd of ethnic Uzbeks gathered in the center of the city of Osh on the evening of June 10 in response to a fight between a few Kyrgyz and Uzbek men in a nearby casino. Kyrgyz and Uzbek crowds clashed throughout the night, with Uzbeks reportedly responsible for many of the attacks, particularly in the beginning, including beatings and killings of ethnic Kyrgyz.

Outraged by the violence and fired up by quickly-spreading rumors of Uzbek atrocities, crowds of ethnic Kyrgyz from nearby and remote villages joined the local Kyrgyz gangs and descended on Uzbek neighborhoods in Osh, Jalal-Abad, Bazar-Kurgan, and other southern towns and cities. From early morning on June 11 through June 14, the attackers looted and torched Uzbek shops and homes, killing people who remained in the neighborhoods. In some neighborhoods ethnic Uzbeks fought back from behind makeshift barricades.

Many ethnic Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, and Russians, it should be noted, saved the lives of their friends and neighbors of other ethnicities while the attacks were under way.

According to satellite images of the area and statistics collected by local authorities in various neighborhoods, several thousand buildings were completely destroyed in Osh, Jalal-Abad, and Bazar-Kurgan during the June violence, the vast majority of which belonged to ethnic Uzbeks.

The exact number of casualties remains unclear. Based on hospital records, the authorities confirmed the deaths of 356 people, although one official said that almost 900 deaths have been registered. A definitive number of deaths has been difficult to verify, as many families were unable to bring dead relatives to the morgue or arrange for a formal burial during the days of the violence. The authorities have not released an ethnic breakdown of deaths.

The Role and Responsibilities of the Authorities

The attacks on Osh’s Uzbek neighborhoods of Cheremushki, Shait-Tepe, Shark, and others, described to Human Rights Watch independently by dozens of witnesses, show a consistent pattern. In many accounts, individuals in camouflage uniforms on armored military vehicles entered the neighborhoods first, removing the makeshift barricades that Uzbek residents had erected. They were followed by armed men who shot and chased away any remaining residents, and cleared the way for the looters.

The authorities claim that Kyrgyz mobs stole the military uniforms, weapons, and vehicles that were used in the attacks. This, if true, raises a separate set of questions regarding the military’s loss of control over weapons and equipment that ended up in the hands of mobs attacking ethnic Uzbeks and their property.

Yet this explanation cannot account for all of the military vehicles used in attacks. The timing of the attacks, which continued for three days, though the authorities claimed to have regained control over the vehicles within hours; the use of different types of armored vehicles, which do not fit the description of the commandeered vehicles; and testimony obtained by Human Rights Watch from a member of the security forces suggest that at least some government forces facilitated attacks on Uzbek neighborhoods by knowingly or unwittingly giving cover to violent mobs. An additional question is whether they actively participated in these attacks, and if so to what extent.

While the authorities had the right to enter Uzbek neighborhoods, including by force, to disarm Uzbek perpetrators of violence or to rescue Kyrgyz residents who may have been held hostage, they also had an obligation to ensure the safety of the residents in those neighborhoods in light of the presence of large Kyrgyz mobs that clearly posed a serious, identifiable threat to the Uzbeks.

Kyrgyz police and government forces faced monumental challenges trying to restore law and order during the June 10-14 mayhem. In some areas, such as in the town of Kara-Kulja and in the town of Aravan, Human Rights Watch documented how police and local authorities prevented ethnic Kyrgyz from descending on Osh.

With the exception of these few areas, however, Kyrgyz security forces failed to contain or stop the attacks, which eventually petered out several days after they had erupted. The authorities reasonably claimed that government forces were largely unprepared and were quickly overwhelmed by the scale of the violence and outnumbered by attackers. Furthermore, the security forces were poorly trained, outfitted with old equipment, and demoralized by harsh criticism for the use of force in past conflicts.

However, the security forces seemed to respond differently to acts of violence depending on the ethnicity of the perpetrators, raising concerns that capacity was not the only reason for the failure to protect ethnic Uzbeks. The security forces seemed to focus resources on addressing the danger presented by Uzbeks, but not by Kyrgyz, even after it became clear that Kyrgyz mobs posed an imminent threat; and the forces took very limited, if any, operational measures to protect the Uzbek population.

Although officials announced that forces would be posted at entry points to the city of Osh, Kyrgyz villagers told Human Rights Watch that they saw few, if any, government forces on their way into the city.

Several law-enforcement personnel told Human Rights Watch that their hesitation to intervene was due in part to the fact that they did not have orders to use any form of lethal force to stop people engaging in violence. While international law allows for the use of force, including lethal force, by law enforcement officials in certain circumstances, it is unclear what force, if any, was used to prevent the attacks on Uzbek neighborhoods.

There is no doubt that the Kyrgyz authorities faced extraordinary challenges during the outbreak of violence. But their failure to stop killings and large-scale destruction of property must be examined to determine whether all possible measures were taken to protect all citizens. The degree to which the authorities’ response was selective or partial is an issue that requires further investigation in the context of both a criminal investigation of individual responsibility for human rights violations and national and international inquiries into the violence.

Violations in the Aftermath of the Violence

As early as June 11, 2010, Kyrgyz authorities began a criminal investigation of the violence, and have so far opened more than 3,500 criminal cases involving charges of mass disturbance, murder, inflicting bodily harm, arson, destruction of property, robbery, and other crimes committed.

The Kyrgyz interim government has taken numerous measures aimed at national reconciliation. It has established a 30-member national commission to examine the reasons for and consequences of the June violence, and a report is due by September 10, 2010. The commission, however, does not appear to be tasked with examining the role and responsibility of government forces in the violence.

The Kyrgyz authorities have the power and duty to investigate the acts of violence committed from June 10 to 14 and to bring the perpetrators to justice. But Human Rights Watch found that the criminal investigation has been carried out with serious violations of Kyrgyz and international law.

Shortly after the violence ended, the Kyrgyz security forces removed the barricades erected around Uzbek communities and immediately moved in to conduct large-scale “sweep” operations, allegedly to confiscate illegal weapons and apprehend the perpetrators of violence. Yet during their operations, the law enforcement officers acted in an illegal and abusive manner, beating and insulting residents, looting their homes, and, in at least one case, tearing and burning their identification documents. During one of the operations, in the village of Nariman, security forces injured 39 residents, two of whom died in the hospital from the injuries they suffered.

In addition to large-scale operations, various law enforcement agencies have been conducting daily, targeted raids in predominantly Uzbek neighborhoods of Osh. Dozens of witnesses provided consistent accounts of security forces conducting arbitrary, unsanctioned searches of people’s homes without identifying themselves or explaining the reasons for the raid; threatening and insulting the families; refusing to tell the families where detainees were being taken; and, in some cases, beating detainees and planting evidence, such as spent cartridges, during the operations.

In cases documented by Human Rights Watch, detainees were taken to the Osh City Police Department, Osh Province Police Department, local police precincts, the National Security Service (SNB), the Regional Department for Fighting Organized Crime (RUBOP), or one of six military command posts (in Russian, komendatura) in the city. It was not possible for Human Rights Watch to determine how many detainees are currently being held in such facilities—officials claim that there is no central database and that each facility keeps its own record, if there is any at all.

Five lawyers told Human Rights Watch that the authorities have been systematically denying defendants due process rights, such as the right to representation by the lawyer of their choice, and the right to consult with a lawyer in private, so their clients cannot complain confidentially about ill-treatment, extortion, and other violations. The lawyers also said that the authorities have routinely refused to order medical examinations of detainees in cases of suspected ill-treatment.

Human Rights Watch received dozens of reports of police officials demanding substantial bribes from family members (ranging from US$100 to $10,000) for the release of detainees.

While the authorities claim to be investigating crimes committed during the June violence by both ethnic groups, Human Rights Watch research indicates that the security operations disproportionately target ethnic Uzbeks. Officials have not released figures showing the ethnic breakdown of the detainees, and they claim they have kept both Uzbek and Kyrgyz suspects in detention. However, information provided to Human Rights Watch by law enforcement officials, released detainees, and lawyers alike indicates that the overwhelming majority of detainees have been ethnic Uzbeks.

Research by Human Rights Watch indicates that law enforcement officers routinely subjected people detained in connection with June violence to ill-treatment and torture in custody.

Human Rights Watch received information about torture and ill-treatment of more than 60 detainees based on testimony from recently-released victims, photos of their injuries from beatings, testimony from lawyers, family members, and other detainees who saw the victims while they were still in detention.

However, it is possible that this may represent only a fraction of the total number of cases. At least two detainees held in the temporary detention facility of the city police for several days reported seeing dozens of other detainees being brutally beaten in the interrogation room, the corridor, and the inner courtyard. Many victims and their family members were too intimidated to speak about their experiences, fearing further persecution, and as of this writing, no independent observers had access to the temporary detention facilities.

The main methods of ill-treatment appear to be prolonged, severe beatings with rubber truncheons or rifle butts, punching, and kicking. In at least four cases, the victims reported being tortured by suffocation with gas masks or plastic bags put on their heads; one detainee reported being burned with cigarettes, and another reported being strangled with a strap. In all cases, these methods were used in an attempt to coerce the detainees into confessing to crimes committed during the June violence or into implicating others.

The report contains detailed descriptions of five illustrative cases (one involving two victims) of torture and ill-treatment in custody.

Another characteristic feature of the authorities’ handling of the investigation has been harassment of and attacks on lawyers representing clients arrested in relation to the June violence.

Half a dozen independent lawyers—ethnic Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, and Russians—told Human Rights Watch that local law enforcement authorities had actively prevented them from helping their clients or even seeing them. On several occasions, officials had threatened and insulted them for defending Uzbeks, and on at least three occasions, they had either mobilized or threatened to mobilize the relatives of Kyrgyz victims of the June violence to attack them.

Human Rights Watch also found that after the large-scale violence subsided, ethnically-motivated attacks continued in Osh province, while the authorities were either unable or unwilling to prevent and stop them. This pattern became particularly obvious in a series of attacks against ethnic Uzbeks whose relatives had been detained in the course of the investigation into the June violence.

A crowd of ethnic Kyrgyz attacked and brutally beat over a dozen people, primarily women, in front of the Osh City Police Department and the adjacent pretrial detention facility where they had come to visit their detained relatives or bring food parcels for them. Victims and witnesses unanimously told Human Rights Watch that while the crowd attacked, dozens of armed policemen and guards stood around doing nothing to stop the attackers. One law enforcement official indicated to Human Rights Watch that he believed somebody from within the police department or detention facility had been coordinating the attacks.

Response of the Authorities

In the course of its research in Kyrgyzstan, Human Rights Watch raised the issue of arbitrary arrests and torture in detention with the minister of interior, the deputy general prosecutor of Kyrgyzstan in charge of the investigation into the June violence, the senior advisor to President Otunbaeva, the chief military prosecutor, and the military prosecutor for Osh province, the head of Osh city police and another high-level city police official, the prosecutor and deputy prosecutor of Osh, the head of Kara-Suu district police department (ROVD), and the prosecutor of the Kara-Suu region.

Senior government officials in Bishkek seemed to be aware of the situation and have taken both public and, based on the information they shared with Human Rights Watch, private measures to address it. Yet at the same time, law enforcement officials in Osh variously dismissed allegations of abuse and acknowledged that abuse took place. In several cases victims of abuse told Human Rights Watch that officials had threatened them not to speak of what had happened.

Local law enforcement officials explained and justified ill-treatment in custody by saying, for example, that they themselves were not present during the interrogations and could not control what transpired, or by complaining that without such methods, suspects would never confess to their crimes. Prosecutors, in turn, claimed they could not launch investigations into allegations of torture because they had not received complaints from the victims. This latter claim was inaccurate—Human Rights Watch researchers had personally delivered at least two such complaints to some of the same local prosecutors. The refusal to investigate ill-treatment is also a violation of the authorities’ obligations under international law, which requires them to act whenever there are reasonable grounds to believe that an act of torture has been committed, regardless of whether a formal complaint has been filed.

Human Rights Watch was also particularly alarmed by the authorities’ response to the sweep operation in Nariman, where evidence of abuse seemed quite obvious. While the Kyrgyz authorities initially opened an inquiry into the operation to determine the responsibility of the security forces for violations, on July 15, 2010, the chief military prosecutor informed Human Rights Watch that no criminal investigation would be opened into the Nariman events because he found the actions of the law enforcement agencies during the operation—including shooting and severe beatings that caused two deaths—to be “lawful and adequate.”

At the time of writing, Human Rights Watch continued to receive reports of arbitrary arrests and ill-treatment in detention.

International Response and Recommendations

A unified international community quickly condemned the violence and called for law and order to be restored. Key governments and international organizations were much more hesitant, however, to take the necessary measures to protect the civilian population. Despite calls from the Kyrgyz authorities during the violence, no international body proved ready to deploy stabilization forces.

Six weeks after the violence erupted, the member states of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) finally reached an agreement to deploy a modest unarmed international police force to the region in a monitoring and advisory role. The Kyrgyz government has also requested the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly’s special envoy for Central Asia to coordinate the preparation process for an independent international commission of inquiry into the June violence.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Kyrgyz authorities to cooperate fully with the international police force and the international investigation; to investigate and hold to account individuals who incited, organized, committed, or otherwise facilitated the violence, irrespective of ethnicity or affiliation with the authorities; to establish the scope of state liability for the violence and its impacts, including acts of negligence on the part of the officials, and to immediately end the widespread ongoing practice of arbitrary arrest, extortion and use of torture and ill-treatment.

Human Rights Watch also calls on the international community to ensure the effective and speedy deployment of the international police force and to support efforts for an international investigation.

Methodology

This report is based on more than 200 interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers in southern Kyrgyzstan from June 10 to July 25, 2010.

For almost two months since the beginning of the violence, Human Rights Watch has maintained a constant presence on the ground.

Human Rights Watch researchers worked in Osh, Jalal-Abad, Kara-Suu, Bazar-Kurgan, Suzak, Alay, Kara-Kulja, and other towns in the south. We interviewed both Kyrgyz and Uzbek victims and witnesses, lawyers, human rights defenders, and community activists. Human Rights Watch also interviewed local government officials, law enforcement and military personnel, and military and civilian prosecutors.

The interviews were conducted in Russian, with translation from Kyrgyz or Uzbek where necessary, and, in certain cases, in English, with translation into Russian or Kyrgyz or Uzbek.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed photographic, video and documentary evidence handed to us by victims, witnesses and others, in addition to collecting our own photographic and video material. We also reviewed satellite imagery of the area and analysis provided by the United Nations Operational Satellite Applications Programme (UNOSAT).

In several areas, Human Rights Watch researchers examined forensic evidence such as tracks and marks from military vehicles, ammunition and spent cartridges and bullet marks on buildings.

On several occasions in the course of our investigation, we shared preliminary findings with the highest Kyrgyz authorities, including President Roza Otunbaeva and her advisors, Interior Minister Kubatbek Baibolov, and Chief Military Prosecutor Aibek Turganbaev.

Some of the information contained in this report has been earlier publicized by Human Rights Watch in the form of news releases, letters to the government and its international interlocutors, and other statements.

Names of many witnesses in this publication were changed or withheld to ensure the safety of witnesses and their families.

This report focuses on the events of June 10 to 14 and their aftermath, analyzing specifically the liability of government and security forces for the violence. Human Rights Watch is aware of numerous theories about who authored the violence, yet because Human Rights Watch has not been able to find irrefutable evidence to support any of these theories, we do not discuss them in detail in this publication.

Given the large-scale nature of the violence, some facts in the chronology section of the report might be clarified as more evidence comes to light.

This report uses the adjective “Kyrgyz” to refer both to ethnic Kyrgyz and to the authorities of Kyrgyzstan. Osh is both the name of a province of southern Kyrgyzstan and also the city that is the capital of this province. Unless otherwise noted, we use Osh to denote the city.

Background: Old Grievances and Political Upheaval

Past and Current Grievances

Spread across Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan, the Ferghana Valley, which includes Osh and Jalal-Abad provinces, is a cultural and linguistic crossroads. While ethnic Kyrgyz constitute a clear majority—both in Kyrgyzstan as a whole and in southern Kyrgyzstan—the provinces of Osh and Jalal-Abad have a significant Uzbek minority. In some cities and districts, ethnic Uzbeks even form a majority or a near-majority, such as in the cities of Osh (49%) and Uzgen (90%) and in Aravan district (59%).[1]

Historically, Osh, Jalal-Abad, Uzgen, and other settlements were inhabited by sedentary Uzbek traders and farmers, while the nomadic and semi-nomadic Kyrgyz moved between winter camps and summer pastures in the surrounding mountains. Yet border delimitation in the 1920s and forced collectivization in the 1930s disrupted centuries-old economic and social structures, and ethnic Kyrgyz increasingly started to settle in the valley and lowlands, which put pressure on land and water resources in areas already inhabited by ethnic Uzbeks.

The problems became more acute as the population grew. Grievances over land and water distribution increasingly took on an ethnic dimension during the perestroika and glasnost era in the mid-to-late 1980s, as ethnic, linguistic, and cultural identities became stronger.[2]

The 1990 Osh riots

The November 1989 Supreme Court decision to replace Russian with Kyrgyz as the official language of the Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic prompted the Uzbek community in Osh to create the organization Adolat, which also promoted the creation of an Autonomous Osh Province and complained about the underrepresentation of ethnic Uzbeks in government structures and public services.[3]

The Kyrgyz counterpart organization, Osh Aymaghi, created in May 1990, focused on the economic deprivation and land shortage facing ethnic Kyrgyz. Responding to Kyrgyz demands for land, the Kyrgyz-dominated administration of Osh allocated plots of land for housing projects on land owned by an Uzbek-dominated collective farm.

On June 4, 1990, the local police used force to disperse crowds of Kyrgyz and Uzbeks who had gathered on a disputed plot of land at the outskirts of Osh ready to attack each other.[4] The fighting quickly spread to Uzgen and about 30 villages around Osh and ended only after Soviet troops intervened several days later.[5]

According to official sources, more than 300 people were killed, more than 1,000 wounded and over 500 arrested.[6] Several hundred houses were burned and looted. The government declared a state of emergency that was lifted only in November, and incidents of violence continued for more than two months until early August.[7]

The age-old dispute over land distribution between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks resurfaced in January 2010 when the mayor of Osh, Melisbek Myrzakmatov, announced that the development of a general reconstruction plan for Osh would be a main priority in 2010. According to the report presented by the mayor, the city planned to build 12 residential buildings nine to twelve floors high in 2010.[8]

Unequal distribution of economic and political power

Scholars have emphasized grievances about economic and political power as important factors fueling tensions and conflict between ethnic Uzbeks and Kyrgyz in Kyrgyzstan. In 1993, a scholar found that “Kyrgyz relations with the Uzbek was the most frequent subject, second only to the declining economic conditions, which was brought up” by his interviewees.[9]

A study conducted in 2003 found great potential for ethnic conflict in southern Kyrgyzstan:

Interview data suggest continuing animosity between the two communities in this region. The phenomenon is exacerbated by the clear underrepresentation of Uzbeks both in local administrations and at the national level, by continuing tensions between the two governments over border demarcation and border closure, and by the Uzbek government’s mining of border territories, which has caused several civilian fatalities. In short, there has been and there remains a potential for conflict along ethnic lines in this region of Kyrgyzstan.[10]

Observers have also noted similar concerns more recently. For example, the OSCE high commissioner for national minorities noted in his May 2010 statement that under the Bakiyev government:

[E]mployment, particularly in the state sector, was skewed in favour of persons claiming titular identity, notably in the police, judiciary and security forces. Knowledge of the State language was increasingly being set as a prerequisite for state sector employment.… Members of minority communities had few opportunities to realize their potential, except in the business sector. This particular minority niche led to accusations that minorities became wealthy at the expense of the Kyrgyz people.[11]

The closure of Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s borders with Kyrgyzstan after the ousting of the Kyrgyz president in April left thousands of labor migrants, merchants and shuttle traders without an income, severely disrupting the Kyrgyz economy and in turn further fueling ethnic tensions.[12]

Political Violence and Upheaval in April 2010

On April 7, demonstrators ousted President Kurmanbek Bakiyev from power, throwing the country into political turmoil. As before, the battle for political power initially involved mainly ethnic Kyrgyz political leaders and supporters.

Brought to power by the 2005 Tulip Revolution, Bakiyev became increasingly unpopular during his presidency. In October 2007, Bakiyev put forward a new Constitution that consolidated his presidential power and seemed to abandon his agenda for democratic reform. His government also increasingly persecuted influential opposition political leaders, and in 2009, the authorities imprisoned several opposition leaders on dubious criminal offenses.[13]

In response to these arrests and other grievances, including alleged nepotism, mismanagement, increased energy tariffs, growing corruption, and the government’s closure of several media outlets,[14] the opposition took to the streets several times in March 2010 and planned nationwide gatherings for April.

On the eve of the gatherings, however, the authorities detained several opposition leaders, which enraged their supporters. On April 6, a planned gathering in Talas, a city in northwestern Kyrgyzstan, turned violent when authorities detained Bolat Sherniyazov, an opposition leader on his way to the protest. Attempts by security forces to disperse the gathering escalated the situation further, and the crowd raided the local police station and severely beat several police officers, including the then minister of interior.[15]

The next day, violence also erupted in the capital of Bishkek when security forces tried to disperse a peaceful protest against the authorities’ detention of opposition leaders. When demonstrators resisted and started throwing stones, the authorities used tear gas, rubber bullets, and stun grenades, further enraging the crowd. Some demonstrators armed themselves with weapons that they took from the police; others physically attacked police officers, injuring several hundred officers. Thousands of people eventually gathered in front of the White House in Bishkek in a standoff with security forces. As the situation escalated, security forces fired on the demonstrators with live ammunition.[16]

Clashes ended in the early morning hours of April 8, when opposition supporters took control of the White House, forcing Bakiyev to flee his office, and eventually, on April 15, the country, leaving a 14-member interim government of opposition leaders in charge. Eighty-five people were killed and hundreds wounded during the clashes from April 6 to 8.[17]

On April 8, Roza Otunbaeva, head of the interim government, announced the establishment of a commission to investigate the violent events of April 6 to 8. As of this writing the commission has not yet published its final report.[18]

Continued unrest

In the months following the April violence, the situation in Kyrgyzstan remained tense. In some cases, the violence seemed to reflect economic grievances directed at ethnic minorities. For example, on April 9, mobs in Tokmok, in northern Kyrgyzstan, ransacked shops belonging to ethnic Dungans and Uighurs, injuring at least 11 people.[19] Several days later, a café belonging to ethnic Dungans in neighboring Gidrostroitel was torched, and mobs threw stones at firefighters attempting to put out the fire. The flames killed two people.[20]

Larger-scale violence occurred on April 19, when five people died and between 25 and 40 were injured as several hundred ethnic Kyrgyz looters tried to seize the land and homes of ethnic Russian and Meskhetian Turks in the village of Mayevka, near Bishkek. They demanded the redistribution of land, claiming that Kyrgyz land should belong to the Kyrgyz people. The mob reportedly attacked residents with sticks and metal bars and set several houses on fire.[21] The interim government sent troops and armored vehicles to Mayevka and detained more than a hundred people, most of whom were released the next day. Six men were charged with “organizing mass disturbances.”[22]

Growing tensions in southern Kyrgyzstan

Immediately after his ouster on April 7, Bakiyev went to Jalal-Abad, in his home region of southern Kyrgyzstan, where he still enjoyed considerable support. Even though he soon left for Belarus, where he has been since, his brief time in Jalal-Abad shifted the epicenter of the political struggle from Bishkek to southern Kyrgyzstan. In the weeks following his ouster, Bakiyev’s supporters attempted to stage a comeback from the south by interrupting demonstrations in support of the interim government, organizing their own demonstrations, and forcibly taking over government offices.

Adding to the uncertainty were questions about the allegiances of local security forces, some of which were believed to be under the control of Bakiyev’s brother.[23] On April 19, for example, the same day that Bakiyev supporters seized the building of the Jalal-Abad provincial government and installed a pro-Bakiyev governor, around 1,000 policemen in Osh gathered at the main square, demanding that the government increase their salaries and open an investigation into the April 7 events. They also protested against the interim government’s use of police “for political purposes.”[24]

To counter Bakiyev’s strong support in the south, the interim government reached out to the Uzbek population, which traditionally had not been involved in politics. After Bakiyev supporters interrupted a meeting organized by supporters of the interim government in Jalal-Abad on April 14, preventing Uzbek community leaders from speaking, Kadyrjan Batyrov, a former member of parliament and a wealthy Uzbek businessman, gathered 1,500 people at the People’s Friendship University, which he had founded. The participants issued a letter of support to the interim government, which also listed 19 demands, including that the interim government “ensure the safety of all residents of the province, ensure public order, prevent ethnic conflicts, and solve a number of local problems.”[25]

On several occasions, Batyrov’s aid was crucial for the interim government to retain power in the south, such as on May 14, when Batyrov and his supporters helped recapture government buildings that Bakiyev supporters had forcibly taken the day before. [26]

The Uzbeks’ newfound role as power brokers in Kyrgyzstan emboldened the Uzbek community to make political demands. After Batyrov had helped clear the main square in Jalal-Abad of Bakiyev supporters on May 14, he said in an interview that:

[F]rom now on, Uzbeks who live in Kyrgyzstan will not remain in their role as observers … we want to actively participate in the governance of the state, in the political life of Kyrgyzstan … the Uzbeks stood hard on their position and fulfilled their part in fighting the previous regime.[27]

The writing of a new Constitution and plans for a constitutional referendum on June 27 also encouraged ethnic Uzbeks to air their political grievances. In early May, representatives of the Uzbek community met with the interim government to submit their demands for more political and social participation, including proportional representation for ethnic Uzbeks at all levels of government administration and state recognition of the Uzbek language.[28] The draft Constitution, published on May 21, did not reflect these demands.

The increasing involvement of ethnic Uzbeks in the political power struggle in Kyrgyzstan did not sit well with many ethnic Kyrgyz who saw the political domain as their prerogative. After his visit to Kyrgyzstan in May, Knut Vollebaek, the OSCE high commissioner for national minorities, told the OSCE’s Permanent Council:

I was given copies of newspaper articles which, for example, called for the expulsion of ethnic Uzbeks from Kyrgyzstan so that the Kyrgyz poor could take possession of their houses and land. Similar views are said to feature in some broadcasts.[29]

Vollebaek, who expressed “fear that the inter-ethnic situation might deteriorate further,” also raised concerns about statements made by some Kyrgyz officials who said they would dismiss all non-Kyrgyz speakers from the government.

Meanwhile, many Kyrgyz were particularly alarmed by a speech, broadcast on Uzbek-language stations Mezon TV and Osh TV, that Batyrov made on May 15 on the premises of the People’s Friendship University. In this speech, Batyrov said:

[T]he time when the Uzbeks sat still at home and not participate in state-building has passed. We [Uzbeks] actively supported the provisional government and must actively participate in all civil processes … If there were not Uzbeks, the Kyrgyz and members of the provisional government would not be able to resist Bakievs in Jalalabad when he tried to conduct his activity against the provisional government.[30]

The torching of several houses belonging to Bakiyev’s family on May 16 further increased tensions, as Bakiyev supporters accused Batyrov of having provoked the arson.[31]On May 19, several thousand ethnic Kyrgyz gathered at the Hippodrome race track near Jalal-Abad, demanded Batyrov’s arrest, and proceeded first to the offices of the Jalal-Abad provincial administration then to the People’s Friendship University, where they clashed with ethnic Uzbeks who had gathered to defend the university. In a preview of the June violence in Osh, rumors of several dozen deaths mobilized more people to come to the scene, and parts of the university were set on fire.[32]Special forces eventually blocked the roads in and around Jalal-Abad, and by late evening, the crowds dispersed. According to the Ministry of Health, the clashes resulted in two deaths and 62 people injured.[33]

A curfew imposed in Osh and Jalal-Abad on May 19 seemed to prevent the outbreak of new violence for a short period, although the situation remained tense.

Mayhem in Southern Kyrgyzstan June 10-14

Violence erupted again in southern Kyrgyzstan when a large crowd of ethnic Uzbeks gathered in the center of Osh on the evening of June 10 in response to a couple of fights between small groups of Kyrgyz and Uzbek men earlier that day. Kyrgyz and Uzbek crowds clashed throughout the night, with Uzbeks reportedly responsible for many of the initial attacks. For example, a member of a local law enforcement agency moving around the city that night recounted witnessing several attacks on ethnic Kyrgyz at the beginning of the night, and several attacks on ethnic Uzbeks later in the night, but said that they were unable to interfere. [34]

Outraged by the violence, and concerned about relatives in the city, crowds of ethnic Kyrgyz from neighboring villages descended on Osh city. From early in the morning on June 11, crowds of ethnic Kyrgyz from surrounding villages joined locals in Osh in looting and torching Uzbek shops and neighborhoods, and sometimes killing Uzbeks they encountered.

It is still unclear how many people died during the violence. On August 9, 2010, the Ministry of Health of Kyrgyzstan reported that 371 people had died in Osh and the southern provinces during the violence, although the true number is likely higher, as ongoing attacks prevented many families from bringing dead relatives to the morgue or arranging for a proper burial, leaving many casualties unregistered.[35] According to the Office of the Prosecutor General, 62 bodies in the mortuaries in Osh province remain unidentified.[36]

On August 9, prosecutor general’s press office stated that 46 people were still missing.[37]

The authorities have not released casualty numbers by ethnicity. One senior law enforcement official told Human Rights Watch that there were about equal numbers of Kyrgyz and Uzbek casualties, but Human Rights Watch has not been able to independently verify that claim.[38] There has to date also been no information on how many, if any, of the deaths were the result of the use of force by officials, and how many resulted from violence by non-state actors.

While the final numbers and ethnic breakdowns of the casualties are still unclear, information about the destruction of property is more conclusive. According to satellite imagery analyzed by the United Nations Operational Satellite Applications Programme (UNOSAT), more than 2,600 houses were completely destroyed in Osh and Jalal-Abad provinces.[39] Human Rights Watch visited all the areas that were severely affected. The vast majority of the destroyed residential houses and businesses belonged to ethnic Uzbeks. Several Kyrgyz houses and shops were also burned down, but the scale of destruction in Kyrgyz and Uzbek neighborhoods is incomparable, a fact that several high-ranking government and police officials confirmed to Human Rights Watch.

The following chronology of events is based on more than 200 interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers in southern Kyrgyzstan from June 10 to July 25. The account is not exhaustive, and times, locations and other circumstances might be clarified as more information comes to light.

Eruption of Violence and Attacks on Uzbek Neighborhoods in Osh

Eruption of violence June 10-11

The violence in southern Kyrgyzstan was set off by a couple of scuffles between ethnic Kyrgyz and ethnic Uzbeks, including one by a casino near the Alay Hotel, in the center of Osh in the evening on June 10.[40] Even though only a handful of people were involved in the initial incidents, word spread quickly, and a crowd of ethnic Uzbeks began gathering in the street outside the casino around 11 p.m.

According to several witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the crowd eventually grew to several thousand, including some people armed with sticks, stones and iron bars.[41] The group became increasingly aggressive, shouting anti-Kyrgyz slogans, and some people set fire to the casino and a car.

Police arrived on the scene only several hours after the incident by the casino and initially could not disperse the crowd. Eventually, riot police (known by the Russian acronym SOBR) and troops from the Ministry of Internal Affairs dispersed the crowd by moving in with an armored personnel carrier (APC), firing into the air and using smoke grenades.[42] SOBR and internal affairs troops continued to disperse the crowd along several roads leading from the intersection where the standoff was taking place.

As events unfolded near the casino, violent clashes also erupted in other parts of the city. While Human Rights Watch documented attacks against both ethnic Kyrgyz and ethnic Uzbeks, most of the attacks that took place in the night between June 10 and June 11 seem to have been by Uzbeks targeting ethnic Kyrgyz, using fists, knives, sticks and, in some cases, firearms. In a typical case, at around 10 p.m. on June 10, a group of ethnic Uzbeks stopped “Daniyar D.” and “Akjol A.” (not their real names), both 22 years old and ethnic Kyrgyz, as they were driving home to Japalak, a village right outside of Osh. Daniyar told Human Rights Watch:

About 20 or 30 of [the Uzbeks] started beating us mercilessly until we were on the ground and could hardly move. I was begging them to stop, saying that we are all Muslims and can't treat each other like that, but they didn't listen.

They would have killed us, but an older man suddenly intervened and dragged us away from the crowd. He made us sit by the side of the road and said he would shoot us if we tried to flee.

As we were sitting there, we saw the Uzbeks stopping other cars and beating the passengers, while more and more Uzbeks arrived to support them. Eventually, the old man who rescued us led us across the street and told us to escape by foot. We crossed into another neighborhood, and from there a friend gave us a lift home.[43]

A member of a local law enforcement agency who received a mobilization order around 1:30 a.m. recounted several similar incidents, which he witnessed on his way to the provincial administration building in the city center, and later, as he tried to deploy to various parts of the city.[44] The law enforcement official also told Human Rights Watch about several attacks on Uzbeks that he witnessed later that night.[45]

Mobilization of crowds within and beyond Osh

Information—and unsubstantiated rumors—about the violence spread quickly to other parts of the city and to surrounding villages. Twenty-four-year-old “Kanat K.” (not his real name), an ethnic Kyrgyz who lives in the village of Mady, just a few kilometers outside of Osh, told Human Rights Watch that he received a phone call around 2 a.m. on June 11 from a friend who said that the Uzbeks had attacked a dormitory, “slaughtered” several students, and raped a Kyrgyz girl.[46]

Even though many of the rumors, such as that of the killing and rape of students, turned out to be false, they enraged and served to mobilize ethnic Kyrgyz.[47] In the course of the night between June 10 and 11, hundreds of Kyrgyz gathered in several places in and around the city, including by the Zapadniy market, in the village of Japalak, and near the provincial administration building in the center of Osh.[48]

Ethnic Kyrgyz also mobilized in villages outside the city, some of them in districts several hundred kilometers away.[49] Twenty-one year old “Ulan U.” (not his real name) from Gulcha, a town in the Alay district, about 80 kilometers from Osh, told Human Rights Watch that several thousand people from the Alay district went to Osh immediately upon hearing about the violence.[50] His claims were supported by several other people interviewed by Human Rights Watch both in Gulcha and in Osh.[51] People from Kara-Suu, Kara-Kulja and Chong-Alay districts in the Osh province also reportedly went to the city in response to the outbreak of violence.[52]

Several Kyrgyz villagers who descended upon Osh told Human Rights Watch that they initially went there to rescue their relatives or family members. Many had relatives who studied at one of Osh’s universities, and the rumors about horrific acts of violence committed by Uzbeks compelled them to go to Osh to bring their relatives home to safety.[53]

Clashes at barricades

By the time the crowds from the outlying districts reached Osh, Uzbek residents had erected makeshift barricades in the Furkat district on the outskirts of Osh city, blocking one of the main roads leading into the city from the east. As the Kyrgyz approached, they clashed with Uzbeks who were manning the barricades. “Kanat K.” (not his real name), who said that he went to Osh to rescue his sister, told Human Rights Watch:

When we got to Furkat, there were about 1,000 to 1,500 Uzbeks there. They did not let us through. We moved a bit closer to them and we started throwing rocks at each other. At around 10 a.m., however, the Uzbeks opened fire on us. Three people fell right in front of me. I was hit as well, in my hand.[54]

Kanat was transported to the Kyrgyzchek hospital in the Kara-Suu district outside of Osh, which came to serve as a hub for Kyrgyz wounded; the wounded could not be taken to the provincial hospital in Osh because it was located behind the Uzbek barricade at Furkat. A doctor at the hospital in Kyrgyzchek confirmed that the hospital started receiving wounded Kyrgyz just before 10 a.m. on June 11, and that most of them had gunshot wounds. According to hospital records, the hospital received 98 wounded and eight dead that day, including three with burns.[55]

The crowds from the villages attempted several times to break through the Uzbek barricades without success. According to Kyrgyz witnesses, it was only when they started shooting at the Uzbeks using several automatic guns that they took from soldiers who had arrived that the Uzbeks started retreating.[56]

Killings, disappearances, and hostage-taking

Rumors and evidence of brutal killings and hostage-taking rapidly escalated the tense situation. The sight of the charred remains of two Kyrgyz men behind the Uzbek barricades in Furkat, for example, enraged the crowd. The younger Kyrgyz men, in particular, became “uncontrollable” and started to torch Uzbek houses as they moved into the city.[57]

Law enforcement officials also referred to information about the taking of hostages in Uzbek neighborhoods, among other acts, as grounds to remove barricades and disarm the Uzbeks. While it is unclear how widespread the practice was, Human Rights Watch has documented the hostage-taking of both Uzbeks and Kyrgyz.

On June 13, for example, Uzbeks manning a barricade near Jalal-Abad took at least one Kyrgyz captive, demanding that he say on camera that he had been paid to fight against the Uzbeks. He was released the next day.[58] In Cheremushki district, a group of about 30 people in civilian clothes and camouflage uniforms broke into the house of 61-year old “Ulugbek U.” (not his real name), an ethnic Uzbek. When Ulugbek was unable to give them money, they told him that they would then take him and his wife hostage. Their captors took them to several places before dumping them in a basement in Iskhavan district, where, Ulugbek said, there were many other hostages. The next day, their captors took them a place near the airport where 18 Uzbeks were exchanged for 10 Kyrgyz.[59]

Several government officials, including to chief of Osh police confirmed to Human Rights Watch that hostage exchanges were taking place.[60]

Several highly publicized killings, such as the June 13 killing of the head of police, an ethnic Kyrgyz, in the district of Kara-Suu, also served to whip up anti-Uzbek sentiment.[61]

Systematic attacks on Uzbek neighborhoods

For at least three days, starting from early in the morning on June 11, gangs of young Kyrgyz men roamed the city and nearby villages, attacking neighborhoods inhabited predominately by ethnic Uzbeks.

When violence broke out in the night between June 10 and 11, ethnic Uzbeks used cars, trucks, containers, or just sawed-down trees, sandbags and other heavy items to create barricades at the entrances to their neighborhoods. In some areas, the Uzbeks successfully fought off attackers from behind these barricades, at times using firearms, mostly shotguns and hunting rifles. On June 12, for example, residents of Nurdor—a village on the road between Osh and the airport—managed to repel a large crowd of attackers accompanying an APC by blocking the road with a large cargo container and using an automatic weapon to fire upon them.[62]

In other Uzbek neighborhoods, however, armored military vehicles were used to push open a way through the barricades, which allowed crowds to enter and attack. Witnesses in different neighborhoods consistently described to Human Rights Watch a pattern of such attacks. They said that armed men in camouflage uniforms used armored military vehicles, such as a tank or an APC, to break through the barricades at the entrances to Uzbek neighborhoods. Groups of armed men, mostly on foot, followed the military vehicles into the neighborhoods. The men—in some cases dressed in camouflage, and in others in civilian clothes—shot at and sometimes killed or wounded people they found remaining in the neighborhoods, causing the rest to flee.

Witnesses also claimed that gunmen on rooftops of nearby high-rises—or snipers, they called them—shot at and killed people who fought off attacks or who tried to extinguish the fires. A third group of people in civilian clothes then went from house to house, robbing anything of value. The attackers loaded the stolen goods onto civilian trailers, trucks or cars, some of which they took from the local residents, and set fire to the houses, using petrol bombs or other devices, systematically burning several neighborhoods to the ground.[63]

Close to 2,000 buildings were completely destroyed in Osh city during the June violence, the vast majority of them belonging to ethnic Uzbeks.[64] The pattern of attack indicates that the perpetrators targeted Uzbek areas and Uzbek houses. Human Rights Watch observed that many houses in Osh that had the words “Kyrgyz” or “Russian” written on the gates for the most part remained untouched, while houses belonging to ethnic Uzbeks were burned to the ground. Human Rights Watch received contradictory accounts as to whether the houses were marked by the owners or the attackers.

In several areas, the attackers targeted Uzbek houses with precision, indicating local knowledge of the ethnicity of inhabitants of the various houses. On Majerimtal Street close to the old bus station, for example, neighbors showed Human Rights Watch a courtyard in which the attackers had burned down a house that was rented by ethnic Uzbeks, while they had spared the house of the Kyrgyz owner standing right next to it.[65]

Human Rights Watch also documented the beating and killing of Uzbek residents who either were unable to flee or had resolved to stay. These included individuals who tried to prevent the destruction of their homes and to extinguish the fires. For example, at about 1 p.m. on June 11, 14 armed men with guns stormed into the courtyard of 60-year old "Nigora N." in the Shait-Tepe neighborhood of Osh. The men beat Nigora on her legs with a truncheon and burned her skin with a loofah sponge they had set on fire, in an attempt to force her to tell them where her son was. It was unclear to Nigora why the men asked for her son. The bruises and burn marks were still visible when Human Rights Watch talked to Nigora more than a week after the attack. Nigora said:

Some of the men wanted to kill me, but the oldest of them, who was about 30 years old, stopped them. I told them that there was nobody else at home, but they didn't believe me. They went to the building in our courtyard where my son was staying. When they came out, they set fire to the house while my son was still there. They … forced me to watch as the house burned down with my son inside. I don't know why he did not run out. Maybe they killed him when they went in.

Eventually they dragged me out on the street. I was crying and screaming. I watched as they cut the throat of my 56-year old neighbor, set fire to his house, and threw his body into the burning house. I also saw the dead body of our 14-year-old neighbor on the street.[66]

Nigora said she later saw the dead body of her son among the burned ruins of her house.

Human Rights Watch also received credible information about several cases of rape. Sixteen-year-old “Umida U.” (not her real name) told Human Rights Watch that she was raped by the mob that attacked several streets in the Cheremushki neighborhood in the western part of Osh, inhabited predominantly by ethnic Uzbeks. Umida told Human Rights Watch:

The men came and took me to the neighbor's house. There were about 30 women and children there. The Kyrgyz said they would hold us hostage and then exchange us for $4,000 each.

Then I saw that my house was on fire, and minutes later the Kyrgyz men dragged my father out. He was badly beaten, bleeding, and I tried to get out and started screaming at the Kyrgyz who were guarding us to protect him.

Then, two men dragged me out of the house. I was trying to resist, and then a third one hit me hard on the lower back and I was in so much pain I couldn't fight with them any more. The men dragged me to the toilet in the yard of the house, and the two of them raped me. Then another three came and raped me, too. I lost consciousness, and I am not sure how long I stayed there after they left.

I managed to make it back to the house, and then my father and I ran away.[67]

Along with hundreds of other Uzbeks who lost their homes or had to run for their lives, Umida found refuge with wealthy neighbors in an area unaffected by the violence. The neighbors arranged shelter and medical help for her and other victims. A doctor who treated Umida after the rape and confirmed her injuries, told Human Rights Watch that she had treated nine other women and girls, ages 15 to 42, who had been raped.[68] Umida expressed willingness to talk to Human Rights Watch and made an effort to tell her story, but she was visibly in a state of deep shock, hardly speaking to anyone, according to her female relative, and staying in bed at all times, including during the interview.

Yet not everybody was involved in the violence. In the midst of violent inter-ethnic clashes, many ethnic Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and Russians saved the lives of their neighbors of other ethnicities, often at great risk to themselves. For example, Human Rights Watch interviewed several Uzbeks who said that Kyrgyz neighbors saved their lives and houses by either hiding them in their own houses or by telling attackers that Uzbek houses in fact belonged to ethnic Kyrgyz.[69]

Shortly after the violence broke out on June 10, significant parts of the Uzbek population started leaving Osh and surrounding villages. Over the next couple of days several hundred thousand people were displaced, many of whom sought refuge in Uzbekistan or in Uzbek areas close to the border.[70]

Spread of Violence to the Jalal-Abad Province

Violence in Osh eventually also spread to the Jalal-Abad province, located north of Osh, and in particular to the towns of Jalal-Abad and Bazar-Kurgan.

In Bazar-Kurgan, violence erupted on the morning of June 13, after a large crowd of ethnic Uzbeks blocked the road from Bishkek to Osh, presumably to prevent people travelling to Osh from joining the mayhem.[71] The crowd attacked police who arrived to disperse the gathering, injuring the head of the local police station and killing his driver.[72]

Police also tried to disperse a crowd of ethnic Kyrgyz that gathered by the market in response to the blocking of the road, but the crowd outmanned and disarmed the police. The Kyrgyz government’s investigation into the June events also established that during the violence in Bazar-Kurgan, people in at least two civilian cars distributed weapons among the Kyrgyz.[73]

Towards the evening of June 13, crowds started attacking Uzbek neighborhoods, looting and burning Uzbek homes. Twenty-nine-year-old “Navruza N.” (not her real name) recounted to Human Rights Watch what happened when attackers broke into her house on June 13:

There was shooting in the street, but we decided to stay at home. But when they started to break down our gate, we ran through our backyard to our Russian neighbors, who saved us. From there we were able to observe what they were doing. First they took everything that we had. Then we saw how they poured gas on everything and set our house on fire. I was so afraid for our lives and for our small children.[74]

An investigator from the prosecutor’s office told Human Rights Watch on June 20 that the investigation had registered 14 deaths in Bazar-Kurgan, and that 88 injured people had been treated in the hospital, but that the casualty figure might increase because they were still finding dead bodies in the burned-down ruins.[75]

In Jalal-Abad, violence broke out in the afternoon of June 13, when hundreds of ethnic Kyrgyz started moving through the city. According to local residents, the crowd, including at least some people armed with guns, had been gathering by the horse-racing track in town for several days, but that the authorities had done nothing to intervene. Seventy-four- year-old “Khusan K.” (not his real name), who is ethnically Uzbek, told Human Rights Watch:

When we walked out of the mosque on June 13, we saw several hundred Kyrgyz walking by. They were shouting and they had truncheons and hunting weapons. A military vehicle drove ahead of them and there were many people in camouflage uniform as well.

We fled, running along walls, but they opened fire on us and beat us. It lasted for about four to five hours. They went into our houses, took everything we had, and then torched the houses. Phones and electricity were cut off so we could not call anywhere.[76]

Human Rights Watch interviewed two other men also wounded on June 13 as they were leaving the mosque; one of them said that his brother was killed in the same attack.[77] Human Rights Watch observed the wounds of both men, which were consistent with their accounts. One of them also showed Human Rights Watch a bullet that was extracted from the wound in his neck.

Other witnesses described to Human Rights Watch other attacks on Uzbek neighborhoods in Jalal-Abad (on Mumimova and Krasina Streets), during which armed mobs looted houses and set them on fire. In all of the incidents described to Human Rights Watch, witnesses mentioned the presence of military vehicles during the attacks. In at least one incident documented by Human Rights Watch, two women burned to death when the attackers set the house on fire.[78]

The Role of Government Forces in the Attacks

As noted above, dozens of witnesses interviewed independent of each other told Human Rights Watch that individuals in camouflage clothing using armored military vehicles removed barricades blocking entry to ethnic Uzbek neighborhoods, thereby allowing entry to crowds that went on to loot and burn Uzbek houses. Witnesses also reported several cases of men in camouflage beating or killing Uzbeks they found in the neighborhoods. This pattern raises serious concerns that some government forces either actively participated in, or facilitated attacks on, Uzbek neighborhoods by knowingly or unwittingly giving cover to violent mobs.

When Human Rights Watch confronted local law enforcement officials about allegations that people in camouflage using armored military vehicles had participated in the attacks, they either rejected the allegations, saying that no military vehicles were used, or claimed that Kyrgyz mobs had stolen military uniforms, weapons, and vehicles, which were then used in the attacks. In Osh, two high-level officials told Human Rights Watch that mobs of ethnic Kyrgyz commandeered two APCs and stole weapons from a military base, but that the authorities quickly regained control over the vehicles.[79] In Jalal-Abad, a high-level local official told Human Rights Watch that two armored vehicles were taken from two military bases.[80] The officials did not share any details about these incidents with Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch collected independent testimony that in at least one case, mobs commandeered an APC to attack an ethnic Uzbek village. Twenty-two-year-old “Zakir Z.” (not his real name) told Human Rights Watch that on June 13, he was part of a crowd that tried to enter Osh through the Amir Timur district, they were accompanied by an APC. Zakir told Human Rights Watch:

I don’t know when exactly we got hold of it, but it was probably some time in the evening on June 12, because I first saw it at Amir Timur [district] on June 13. They were driving around on it for a couple of hours, but the driver didn’t really know what he was doing, so they quickly got stuck so that nobody could get it out again. Even the military, which arrived later, was not able to get it free again.[81]

Commandeered APCs cannot account for all of the attacks in Osh, however.

Detailed interviews with victims and eyewitnesses indicate that different types of armored military vehicles were used in the attacks. Witnesses distinguished between wheeled vehicles (APC) and tracked infantry fighting vehicles (tanks).[82] Various vehicles were used in several different locations at different times. Human Rights Watch collected testimony about the following incidents:

- Around 11 a.m. on June 11, individuals arriving on an APC removed barricades in the Cheremushki district.[83] One witness saw both an APC and a tank, followed by about forty men who looted and burned houses.[84]

- Around 7 a.m. on June 12, individuals arriving with an armored military vehicle removed barricades at the entrance to Majerimtal Street. A crowd of several hundred people followed, killing at least five and looting and burning more than forty houses.[85]

- Around 8:30 a.m. on June 12, two tanks broke through a barricade at the entrance of the Jidalyk neighborhood. Men in camouflage uniform on the tanks fired from automatic guns and shot to death at least five people as they drove through the neighborhood.[86]

- Around 10 a.m. on June 12, a tank removed barricades in the Tishiktash area in the Shait-Tepe neighborhood. The tank turned around when local residents threatened to set fire to a fuel truck blocking the road. Human Rights Watch photographed marks from the tracks in the asphalt where the tank turned around. All houses in the Tishiktash neighborhood were burned, up to the point where the tank truck had blocked the road.[87]

- On the afternoon of June 12, individuals arriving with an APC removed barricades on Alisher Navoi Street. That day, about 100 to 150 houses were burned to the ground along Alisher Navoi Street.[88]

Law enforcement officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch refused to say what orders had been given to the security forces during the June violence, whether the security forces received any specific orders to remove the barricades in the Uzbek neighborhoods, whether they had specific orders to use armored vehicles to do so, or to what extent orders took into account the danger presented by the Kyrgyz mobs following the APCs into the neighborhoods.

In at least one district, when government forces removed barricades to enter an Uzbek neighborhood, they failed to first disperse mobs that had gathered behind them, thereby facilitating attacks on the neighborhood. “Ruslan R.” (not his real name), a member of a Kyrgyz law enforcement agency, who was patrolling the Cheremushki district on an APC on June 12, told Human Rights Watch that law enforcement services were under intense pressure from the Kyrgyz population, which was angry about Uzbek attacks, to move in on Uzbek neighborhoods and to disarm the ethnic Uzbek residents. Ruslan told Human Rights Watch:

The Uzbeks were shooting from behind the barricades and people were upset, saying that we were just sitting in our APCs, not able to do anything, while the Uzbeks were killing them. People wanted us to enter the Uzbek neighborhoods to take away their weapons. Everybody was angry [about rumors] that the Uzbeks had raped women.[89]

Ruslan told Human Rights Watch that on several occasions, after his unit removed Uzbek barricades, crowds of Kyrgyz followed his unit into the Uzbek neighborhoods:

There were barricades almost everywhere in Cheremushki. When we could, we removed the barricades and drove into the neighborhood. If we were not able to, we just left.

Almost everywhere, the Kyrgyz were running behind us. Especially when we were moving into the Uzbek neighborhoods where they were shooting at us, there were many people running behind us, taking cover behind the APC. We didn’t stay behind in those neighborhoods, but continued on to wherever there were barricades, which we then removed.

There were no concrete orders to remove the barricades, but we had orders to control the situation so that people did not get out of control.[90]

In many cases, witness testimony indicates that the people in camouflage clothing riding on the APCs did not shoot at residents, but only shot into the air—whereas gunmen who followed behind the APCs and the ones positioned on nearby rooftops fired directly on the residents.

In other neighborhoods, witness testimony indicates that individuals riding on the APCs also shot at people using automatic guns. Describing the attack on the Jidalyk neighborhood, “Rustam R.” (not his real name) told Human Rights Watch:

Two tanks broke through the barricade and drove into the neighborhood. The men on the tank started to shoot. They shot my son in the forehead. I could see him lying only three meters away from me, all covered in blood.[91]

The vast majority of Uzbeks interviewed by Human Rights Watch believed that the use of military vehicles proved that government forces had participated in the attacks on their neighborhoods, although some said that it was possible that the people in camouflage clothing using the armored military vehicles were Kyrgyz civilians who had stolen uniforms, weapons and vehicles. The extent to which armored military vehicles used in the attacks on Uzbek neighborhoods, were commandeered by civilian mobs, or under the control of government forces needs to be investigated.

The Kyrgyz authorities had the right to detain and, when relevant, disarm, Uzbeks and Kyrgyz who participated in the violence. However, the authorities also had a duty to protect all residents from attacks on their lives, security and property.[92] Beyond the obligation to investigate the extent of any active participation by security officers in the attacks on civilians, the Kyrgyz government had positive obligations under human rights law to safeguard the rights of citizens to protection from criminal acts by non-state actors.[93]

Insofar as people’s right to life and security is concerned, part of the state’s obligation is met by ensuring that there is adequate law enforcement machinery for the prevention, suppression and punishment of human rights abuses, whether committed by state forces or private individuals. And in appropriate circumstances, it includes an obligation to take preventive operational measures to protect individuals whose security may be at risk. This is the case when the authorities knew or ought to have known of the existence of a real and immediate risk of criminal acts against identified parties, and officials should have taken measures within the scope of their powers that might reasonably have been expected to protect these civilians.[94]

Taking into account enormous challenges faced by the Kyrgyz forces responding to the violence, the investigations should nonetheless examine whether the authorities took all the preventative measures that could be reasonably expected of them to avoid the real and immediate risk to the security of the targeted populations, or whether they were negligent in choosing the course of action they did.[95]

Use of Government Weapons and Equipment in the Attacks

Another issue that raises serious questions about the role of the security forces in the violence is the use of government weapons and military equipment in the attacks on ethnic Uzbeks and their property.

While the crowds of ethnic Kyrgyz started out on the night of June 10-11 largely unarmed, they quickly obtained control over several dozen automatic weapons and, at least for brief periods, armored military vehicles. The ease with which mobs with a clear intention of attacking Uzbeks obtained weapons from the security forces needs to be investigated, not only as a matter of public security and to determine what crimes were committed, but also to determine whether the Kyrgyz military and police bear any liability for failing in their duty to protect civilians from attack.

Ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks each accused the other side of preparing and arming itself for the violence. While Human Rights Watch is not in a position to fully assess the grounds for these accusations, we found no credible evidence that either group used firearms in the initial confrontations. According to witnesses, including a senior riot police officer present at the scene, there were no firearms among the Uzbek crowd that gathered in front of the casino in the evening of June 10.[96] While Human Rights Watch documented the use of firearms in several clashes during the night of June 10 to 11, most of the incidents consisted of beatings and the weapons such as knives, truncheons, and metal rods.

On the morning of June 11, Uzbeks barricading the road to Osh in the Furkat district used firearms to prevent the entry of ethnic Kyrgyz into the city, indicating that the Uzbeks had access to some weapons. According to Kyrgyz villagers, in this incident, the Uzbeks fired from low-caliber weapons and shotguns, not from automatic or semi-automatic weapons.[97]

Several Kyrgyz who tried to enter Osh through Furkat on June 11 in the morning told Human Rights Watch that they were initially unarmed. Several failed attempts to break through the Uzbek barricades by the numerically-superior crowd and significant casualties that morning lend support to that claim.

In several incidents, however, Kyrgyz mobs obtained weapons owned by government forces, which put up only limited resistance. For example, 21-year-old “Ulan U.” (not his real name), who is an ethnic Kyrgyz, told Human Rights Watch that when ethnic Uzbeks stopped the Kyrgyz crowd he was part of in the Furkat district on June 11, the Kyrgyz crowd eventually surrounded two infantry fighting vehicles that arrived and forced the soldiers to hand them their weapons. The man, who directly witnessed the incident, told Human Rights Watch that government forces resisted, but that the crowd quite easily disarmed them without them firing a single shot. He told Human Rights Watch: “Of course they resisted, but they were 13 soldiers and we were thousands. There was a certain difference in numbers.”[98]

Villagers from Gulcha and other witnesses also told Human Rights Watch that several hundred Kyrgyz attacked a Kyrgyz border guard unit in Chong-Alay district, near the Chinese border, obtaining dozens of automatic weapons.[99] In Osh itself, a resident in the Cheremushki district told Human Rights Watch that he witnessed a crowd of between 800 and 1,000 Kyrgyz make several attempts and ultimately succeed in obtaining weapons from a nearby military base.[100]

The chief of police in Jalal-Abad told Human Rights Watch that mobs obtained 59 automatic weapons, two grenade launchers and two military vehicles from two military bases in Jalal-Abad province.[101] When Human Rights Watch asked a high-ranking military officer about the attack on his military base, the officer, who refused to give his name, said that "in order to avoid bloodshed, the troops abandoned the base," but claimed that they had first "broken" the ignition on the military vehicles to avoid them being used by the mob.[102]

Witnesses also observed the distribution of weapons and ammunition by unknown sources to ethnic Kyrgyz. For example, 50-year-old “Akram A.” (not his real name) told Human Rights Watch that he saw men in two civilian cars distributing weapons to a group of young Kyrgyz men near the Kyrgyziya Movie Theater in the Cheremushki district. Akram told Human Rights Watch:

The younger guys did not even know how to shoot or to hold the weapons; they were just waving them around. But afterwards, some older guys came and showed them how to. People on the APCs were throwing bags of ammunition to them.[103]

Another witness said that on two occasions on June 12 or 13, he saw people in cars distributing weapons to the Kyrgyz, both times in the center of Osh.[104]

Government forces faced staggering challenges as they confronted large crowds intent on disarming them. In some cases, they seem to have been significantly outnumbered and might not have had any realistic chance of resisting. However, this does not relieve the authorities of the responsibility to investigate whether government forces failed in their responsibility and handed over weapons and equipment too easily, or whether there were other systemic failings, engaging the liability of the state, that led the crowd to so easily obtain the weapons and equipment.

In interviews with Human Rights Watch, investigative authorities gave no indication as to whether this issue was being examined. The chief military prosecutor of Kyrgyzstan told Human Rights Watch that his office was investigating 22 criminal cases of illegal acquisition of weapons. Judging by his description, however, the cases seemed to focus exclusively on the actions of the perpetrators (none of whom had been arrested at the time), and the goal of returning the weapons to the units; he does not seem to be considering the possibility that there may be liability on the part of the military forces for complicity either in the loss or voluntary handover of weapons and other equipment.[105]

Failure to Prevent and Stop the Violence

With a few exceptions, the authorities failed to contain or stop the violence once it had erupted. They can reasonably claim to have been overwhelmed by the scale of the violence and the size of the mobs, and the security forces had old equipment, poor training, and were demoralized by serious criticism of their use of force in past conflicts.

However, the security forces seemed to respond differently to acts of violence depending on the ethnicity of the perpetrators, raising concerns that capacity was not the only reason for their failure to protect the population. By and large, the security forces seemed to focus resources on disarming the Uzbek population, even after Kyrgyz mobs started to systematically attack Uzbek neighborhoods on June 11 (see above), posing an obvious and imminent danger.

The authorities took several steps to contain the violence once it had erupted. At 2 a.m. on June 11, the government announced a state of emergency in Osh city, Uzgen city, and in the districts of Kara-Suu and Aravan outside of Osh city, and imposed a curfew from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m.,[106] which was later extended to 12 hours, from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m.[107] Curfews were also imposed in the Jalal-Abad region.[108]

In a public address shortly after the violence erupted, Kyrgyz President Otunbaeva said: