“We Have Lived in Darkness”

A Human Rights Agenda for Guinea’s New Government

Summary

In June and November 2010, the Guinean people went to the polls and for the first time since the country’s independence from France in 1958, elected their president in an atmosphere largely free of intimidation, fear, or manipulation. Many Guineans viewed these hugely significant elections as having the potential to end over 50 years of authoritarianism, human rights abuse, and corruption.

To sustain the momentum generated by the elections and fulfill the expectations of Guineans, Guinea’s new president, Alpha Condé, must take decisive steps to address the profound human rights and governance problems he has inherited. These problems—a culture of impunity, weak rule of law, endemic corruption, and crushing poverty—have blighted the lives and livelihoods of countless Guineans. In the coming months, the new president and his government should implement policies that ensure Guinea’s successful transformation from an abusive state into one that respects the rule of law and guarantees the rights of its people.

Since independence, Guinean presidents Ahmed Sékou Touré (1958-1984), Lansana Conté (1984-2008), and Captain Moussa Dadis Camara (2008-2009) have relied on ruling party militias and security forces to intimidate and violently repress opposition voices. Thousands of Guineans—intellectuals, teachers, civil servants, union officials, religious and community leaders, and businesspeople—who dared to oppose the government have been tortured, starved, beaten to death by state security forces, or were executed in police custody and military barracks. Other Guineans have been abducted from their homes and places of work and worship, or gunned down as they demonstrated for better governance or the chance to freely elect their leaders. Their bodies have been hanged from bridges, stadiums, and trees, strewn across roads and meeting places, or simply disappeared without a trace. Countless Guineans were forced to flee their homeland.

Guinea’s judiciary, which could have mitigated some of the excesses, has been neglected, severely under-resourced, or manipulated, allowing a dangerous culture of impunity to take hold. As perpetrators of all classes of state-sponsored abuses and human rights crimes have rarely been investigated, victims have been left with scant hope for legal redress for even the most serious of crimes. Meanwhile, those who are accused of crimes by the authorities endure grossly inadequate due process guarantees, including chronic extended pre-trial detention and abysmal detention conditions.

A woman casts her vote at a polling station in Conakry on November 7, 2010. © 2010 Issouf Sanogo/AFP/Getty Images

Corruption within both the public and private sectors in Guinea has long been endemic. From the petty corruption and bribe-solicitation perpetrated by frontline civil servants to the extortion, embezzlement and illicit contract negotiations that take place in the shadows, those involved in bribery and various forms of corruption are rarely investigated, much less held accountable. Guinea’s past rulers have also largely mismanaged, embezzled, and squandered the proceeds from the country’s abundant natural resources, thereby denying the majority of the population access to even the most basic health care and education. As a result, Guinea is one of the world’s poorest countries and suffers some of the world’s highest rates of infant and maternal mortality and adult illiteracy, despite its natural resources.

To end Guinea’s history of abuse and impunity, the new administration must adequately support and reform the judiciary as a key institution that can protect basic civil and political freedoms. The administration must also ensure that those responsible for past abuses—most urgently, the security forces responsible for gunning down and raping demonstrators in 2007 and 2009—are brought to justice. The government should establish a truth-telling mechanism to expose less well-known atrocities, notably those committed during the reign of Sékou Touré, and to explore the dynamics that gave rise to and sustained successive repressive regimes, and make recommendations to prevent their recurrence. To promote a culture of respect for human rights, Guinea’s new leadership must also ensure the independence of the national human rights institution it established on March 17, 2011.

Condé’s government must also rein in, professionalize, and reform the security sector, and stop using the security forces for partisan ends, as has been past practice in Guinea. Behaving more as predators than protectors, soldiers have been allowed to get away with abuses ranging from isolated criminal acts to crimes against humanity. Members of the ill-trained and undisciplined police force have also been widely implicated in the torture of criminal suspects and unlawful behavior ranging from extortion to drug trafficking. Officials should adopt a zero-tolerance policy on such abuses, and create, staff, and support disciplinary structures to investigate, prosecute, and punish abusers. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and United Nations have proposed a promising roadmap for reform to reduce the size of the army, bolster its civilian oversight, and reinforce discipline within the ranks. To create a more rights-respecting environment, the new government should implement their pertinent recommendations.

The new government should ensure that Guinea’s population can materially benefit from the country’s abundant natural resources by improving economic governance, establishing an independent anti-corruption commission empowered to investigate, subpoena, and indict those who siphon off public resources, and by providing stringent oversight over the budget and natural resource contracts.

Lastly, in order to ensure oversight of the executive and provide for adequate political representation of the Guinean people, President Condé should formulate, promulgate and adhere to a concrete timetable for legislative elections; ensure they are conducted in a free, fair and transparent manner; and take concrete steps to address the lack of neutrality demonstrated by the security forces during the elections which brought him to power.

The political future of Guinea hangs in the balance. The actions that President Condé and his government take, or fail to take, will either usher in urgently needed human rights improvements for Guinea’s population or reinforce a dangerous and painfully disappointing status quo in which the new government and the people they serve remain trapped in the excesses and abuses that have characterized Guinea’s recent past.

Recommendations

To the New Government of Guinea and President

To Address Accountability for Past Abuses and Create a Culture of Respect for Human Rights

- Prosecute in accordance with international fair trial standards members of the security forces responsible for the killings, rapes, and other serious human rights violations committed against pro-democracy protestors in September 2009, regardless of position or rank—including those liable under command responsibility for their failure to prevent or prosecute these crimes.

- Ensure that Guinean investigating judges and other judicial personnel tasked with adjudicating the September 2009 crimes are adequately resourced, protected, and supported by the Ministry of Justice.

- Seek international assistance if authorities find themselves lacking adequate capacity to carry out justice, involving credible, impartial and independent investigations and prosecutions, for the September 2009 crimes.

- Re-establish the national Independent Commission of Inquiry into the 2007 strike-related violence with a view toward making recommendations on accountability.

- Establish a truth-telling mechanism to expose less well-known atrocities, explore the dynamics that gave rise to and sustained successive authoritarian and abusive regimes, and make recommendations aimed at ensuring better governance and preventing a repetition of past violations.

- Support and guarantee the independence of the national human rights institution mandated by Guinea’s new constitution, promulgated on April 19, 2010 and established by presidential decree on March 17, 2011. The commission should be established in line with the UN Principles relating to the Status of National Institutions (the Paris Principles).

- Formulate, promulgate and adhere to a concrete timetable for free and fair legislative elections.

- Enact legislation to abolish the death penalty, given its inherent cruelty and contradictions with Guinea’s obligations under international law.

- Adopt national implementing legislation for the International Criminal Court’s Rome Statute, ensuring, in particular, the inclusion of crimes against humanity provisions in Guinean law.

- Implement into domestic law the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, ratified by Guinea in 1989.

To Strengthen the Judiciary

- Ensure the Ministry of Justice has sufficient support to address deficiencies in the working conditions of judges and other key staff that severely undermine the dispensation of justice and rights of victims and the accused.

- Improve court and caseload management through the prompt establishment of recordkeeping, court reporting, and information control systems.

- Ensure the prompt establishment and independence from government control and direction of the 17-member Superior Council of Judges (Conseil supérieur de la Magistrature) tasked with the discipline, selection, and promotion of judges.

- Ensure all citizens accused of a crime have access to adequate legal representation of their choosing, regardless of their means.

- Establish a law reform commission to review the Penal Code, Code of Procedure, and Civil Code, among other principal legal instruments, and recommend the repeal or amendment of domestic laws that contradict international and regional human rights standards.

- Conduct regular and thorough reviews of all pre-trial detainees and provide increased resources to manage and prioritize their cases, in accordance with Guinean and international law limiting time allowed in pre-trial detention.

- Improve prison conditions by ensuring adequate nutrition, sanitation, medical care, and educational opportunities.

To Address Indiscipline and Impunity within the Security Forces

- Introduce a zero-tolerance policy on criminal behavior and human rights abuses by the army, police, and gendarmes. Investigate and prosecute, in accordance with international standards, members of the security forces against whom there is evidence of criminal responsibility for abuses.

- Implement without delay a comprehensive reform of the security sector. Begin with the formation of a steering committee on security sector reform and use as a roadmap the recommendations contained in the report by the ECOWAS/UN-led security sector reform initiative.

- Adequately support and resource the military tribunal so that it becomes a functional institution, mandated to try military personnel implicated in military crimes (treason, abuse of authority, desertion, disobedience, and insubordination). Ensure that officers of the court, including prosecutors, and defense counsel are fully independent of the military chain of command and of governmental interference.

- Establish a 24-hour telephone hotline, staffed by both civilians and members of the military police, for victims and witnesses to report acts of indiscipline, intimidation, criminality, corrupt practices, and other abuses committed by members of the security forces.

To Address Endemic Corruption

- Declare a zero-tolerance policy on corruption and the use of state funds for personal enrichment by public officials at all levels.

- Establish a fully independent, well-funded, anti-corruption body empowered to investigate, subpoena, and indict public officials implicated in corrupt practices.

- Establish a 24-hour telephone hotline, staffed by members of the anti-corruption commission, to provide information about corrupt practices committed by public officials.

- Ensure complete transparency in the negotiation of contracts between the Guinean government and foreign and Guinean mining companies by providing public access to information on government revenues, and by eliminating confidentiality clauses from contracts before their ratification.

- Ratify and domesticate the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption and the United Nations Convention against Corruption, which Guinea signed in December 2003 and July 2005, respectively.

- Enact and rigorously implement a procurement legislation that is in line with international standards especially in terms of disclosure and transparency.

- Publish the national budget and issue regular updates that accurately detail expenditures. Information on government revenues and expenditures should be made easily accessible and presented in a form that can be understood by the public.

To the International Contact Group on Guinea

- Maintain pressure on all relevant actors to ensure free, fair and transparent legislative elections, the implementation of a comprehensive security sector reform program, accountability for the September 2009 violence, and the strengthening of crucial rule of law institutions.

To Guinean Civil Society and Human Rights Groups

- Undertake comprehensive campaigns to educate detainees about their due process rights.

- Pressure the government to abolish the death penalty and to implement into national law the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and the Convention against Torture.

To the European Union, the United States, France, China, International Financial Institutions and Other International Partners

- Frequently, consistently, and publicly press the new government to prioritize the fight against impunity, to improve its human rights record, and to ensure accountability for the serious human rights violations committed in 2007 and 2009.

- Improve coordination of efforts for security sector reform in support of the ECOWAS/UN-led initiative.

- Provide financial and technical support for the judiciary, including through the establishment of a case management system, witness protection program, and forensic capability.

- Provide financial and technical support for anti-corruption efforts, including an anti-corruption commission.

To the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

- Continue to press the Guinean government to improve its human rights record.

- Extend the mandate of the ECOWAS special representative for Guinea.

- Push for the arrest and extradition from ECOWAS or AU member states to Guinea of Aboubacar Sidiki Diakité for whom an Interpol Red Notice was issued on January 19, 2011 based on a national arrest warrant issued in Guinea, and any other individual later subject to a warrant for suspected involvement in serious international crimes.

To the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

- Continue to monitor and report on ongoing human rights abuses, and ensure that findings are published.

- Train security service personnel and relevant criminal justice agents on legal interrogation techniques, crowd control, appropriate use of force, and international standards relating to investigations and prosecutions.

- Advise the government on the establishment of an independent national human rights institution that will comply with the Paris Principles and on the drafting of a national action plan for the promotion and protection of human rights.

- Provide technical assistance to enhance the expertise of national authorities, including judges and lawyers in the investigation, prosecution, and defense of crimes under international law.

- Provide technical assistance to the Guinean government for the establishment of a witness protection unit and to develop forensic expertise.

Methodology

This report is based on over 200 interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch in Guinea during February, April, August and October 2009, and June 2010, as well as in Dakar, and Washington DC in August and September 2010. This research has been supplemented with dozens of telephone interviews conducted throughout the period and between October 2010 and April 2011. Human Rights Watch interviewed Guinean lawyers, judges, legal clerks, and Ministry of Justice personnel; victims of, and witnesses to, human rights crimes; remand and convicted prisoners and prison officials; members of the army, gendarmerie, and police force; and Ministry of Finance personnel and businessmen. Human Rights Watch also interviewed national and international humanitarian organizations; members of civil society, victims’ associations, and human rights defenders; political party representatives; security sector analysts; Guinean and Dakar-based diplomats; officials from the United Nations, Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and international financial institutions; and drivers, petty traders, and market sellers, among others.

Names of many of those interviewed have been withheld at their request to protect their identity, privacy, and security. Monetary figures throughout this report are calculated using the rate of 6605 Guinean francs (GF) to the US dollar.[1]

I. Background: Decades of Impunity from Independence to the Fourth Republic

Guinea is a West African country of approximately 10 million people. For over 50 years, successive authoritarian regimes systematically denied Guineans the realization of their basic human rights and allowed a climate of impunity for all classes of violations to flourish.

First Republic: Ahmed Sékou Touré’s Reign of Terror

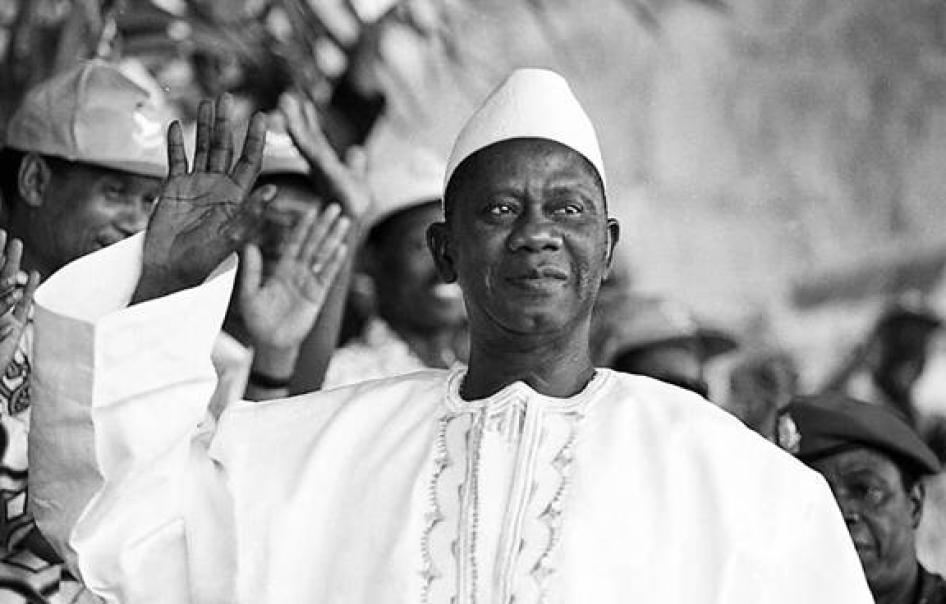

|

Sékou Touré’s 26 year (1958-1984) reign left an indelible mark on Guinea and created a legacy of distrust and fear for those attempting to call their government to account. © 1959 AFP/Getty Images |

Ahmed Sékou Touré, a charismatic labor union leader, ruled Guinea from independence in 1958 until his death in 1984. Touré made Guinea a one-party dictatorship, maintained a stranglehold on all aspects of political and economic life, and used state-sponsored terror ruthlessly to suppress all real and perceived political opponents.[2]

Touré employed a vast network of informants, members of the secret police, party militia from his Democratic Party of Guinea (Parti démocratique de Guinée, PDG), and, to a lesser extent, members of the military to reinforce his authority under which thousands of real and perceived government critics were detained, tortured, and executed in public places, unofficial detention facilities and barracks.[3] The most notorious of these was the Camp Boiro National Guard Barracks in Conakry, Guinea’s Gulag, where hundreds if not thousands are believed to have perished. Oppressed by the atmosphere of paranoia and repression that prevailed in the Touré era, tens of thousands of Guineans fled the country.[4]

The abuses under Touré’s rule were concentrated around the state response to numerous plots—the majority believed to have been contrived—to overthrow his regime.[5] According to academics and historians, Touré used the plots to deflect criticism of his regime and its economic and social policies and eliminate real or perceived opponents.[6] After each reported plot, security forces and government officials carried out a wave of arbitrary detentions, disappearances, show-trials, and, in several cases, public executions. During one particularly bloody plot, the Complot peul, or Fulbe plot of 1976-77, well-respected Peuhl[7] intellectuals, including Boubacar Diallo Telli, the former secretary general of the Organization of African Unity, and countless others, were imprisoned, executed, or died in detention.[8] The violence provoked a mass exodus from Guinea of members of the Peuhl ethnic group and created a painful legacy of mistrust between the Peuhl and Guinea’s second largest ethnic group, the Malinké, to which Touré and many of his key political allies in the PDG belonged.[9]

Committees largely comprising senior PDG officials, and in some cases Touré’s relatives, determined the guilt or innocence of those accused of conspiring against him. The committees forced defendants, who were often tortured, to confess and were not able to appeal death sentences, which were frequently carried out within hours or days.[10] For example, on January 23, 1971, in the aftermath of a real plot,—namely, the military incursion by Portuguese troops based in Guinea-Bissau[11]—the Supreme Revolutionary Tribunal ordered 29 executions, 33 death sentences in absentia, and 68 life sentences of hard labor of Guinean government and military officials alleged to have supported it.[12] On January 25, 1971, following the ruling of the Tribunal, many of the alleged plotters were publicly hanged or executed in military camps, including four high-level government officials who were infamously hanged from an overpass in Conakry.[13]

To date not one individual implicated in the atrocious violations that characterized the 26-year regime of Sékou Touré has been held accountable in a credible judicial proceeding.[14] This impunity set the stage for further abuses, for which Guineans have not yet seen justice done. Mohamed Sampil, who completed his term as President of the Guinean Bar in January 2011, told Human Rights Watch:

Those who committed the [Touré-era] crimes were protected afterwards by the state system. Everyone knows there were many violations of human rights committed during this period, but there was never a trial. Why? Because the crimes were perpetrated for political reasons and with political protections: ‘justice’ was not independent; it was just for the service of the political regime. Continuing impunity set the stage for abuses of power in the following regime and transitional government. Now we must ask whether we will see it continue as before in Guinea’s future. In terms of this tradition of impunity, so far there has not been the political will to change.[15]

Second and Third Republics under Lansana Conté: Entrenching Impunity and Making the Criminal State

Shortly after Touré’s sudden death from heart trouble in March 1984, Army Colonel Lansana Conté took over in a coup d’état the following month. Despite initial promises to ensure better respect for human rights, President Conté presided over another quarter century of state-sponsored abuses and repression, albeit far less extreme than those of his predecessor. From 1984 until his death in office in December 2008, also of natural causes, Conté’s regime was punctuated by excessive use of force against unarmed demonstrators, torture of criminal suspects in police custody, prolonged pre-trial detention, arrests and detentions of opposition leaders and supporters, and harassment and arrests of journalists. While Conté made some initial progress on moving Guinea from a single-party dictatorship to multi-party democracy, these efforts were undermined by deeply flawed and non-transparent presidential polls in 1993, 1998, and 2003, designed to ensure Conté held on to political power. [16]

In response to worsening levels of corruption, poverty, and government abuses, various civil society and professional organizations at various times staged demonstrations across the country, many of which were violently repressed by Conté’s security forces. In June 2006 security forces shot dead at least 13 protestors in Conakry.[17] In January and February 2007 security forces, notably the Presidential Guard, fired directly into crowds of unarmed protestors participating in a nationwide strike against deteriorating economic conditions and bad governance, resulting in at least 137 dead and over 1,700 wounded.[18]

Army Colonel Lansana Conté took over in a coup d’état in 1984. Despite initial promises to ensure better respect for human rights, President Conté presided over another quarter century (1984-2008) of state-sponsored abuses and repression, albeit far less extreme than those of his predecessor. © 2006 Seyllou/AFP/Getty Images

Conté and his government also presided over an increasing criminalization of the state in which members of the ruling party, his family, and security forces engaged in frequent criminal acts ranging from theft and embezzlement to drug trafficking.[19] By the end of Conté’s regime, Guinea had become a major transit hub in West Africa for narcotics being trafficked from South America to Europe.[20]

The latter years of Conté’s regime gave rise to a corrupt patronage network, which siphoned off resources that could have been used to address key economic rights such as basic healthcare and education.[21] The illicit benefits enjoyed by the military’s upper echelons led to a series of revolts by younger army officers, payoffs designed to placate them, and threats of further instability.

Despite symbolic gestures at the behest of Guinean civil society and the diplomatic community, Conté made no meaningful effort to hold those responsible for abuses to account. The gross neglect and politicization of the judicial sector further entrenched the impunity that had taken root under Sékou Touré. Like his predecessor, Conté and his government failed to bring to justice even one member of the security forces credibly implicated in killings and other serious abuses.[22] According to Kpana Emmanuel Bamba, President of the Guinea Chapter of Lawyers Without Borders (Avocats Sans Frontières):

Throughout Guinea’s recent history, the security services have appeared to benefit from total protection. Those who committed abuses have not been sanctioned or judged in accordance with the law. There has been total impunity for the abuses under the Conté regime. His army was well paid, well protected: and not worried about any possibility of accountability measures. In the end, they were right: they were never held accountable.[23]

This concern was reiterated by the United Nations Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on the Prevention of Genocide after a mission to Guinea in March 2010:

“Impunity is the norm; perpetrators of past violence and human rights violations have gone unpunished, including those responsible for massive human rights violations committed during the previous regimes of Sékou Touré and Lansana Conté.”[24]

Fourth Republic: The “Dadis Show”

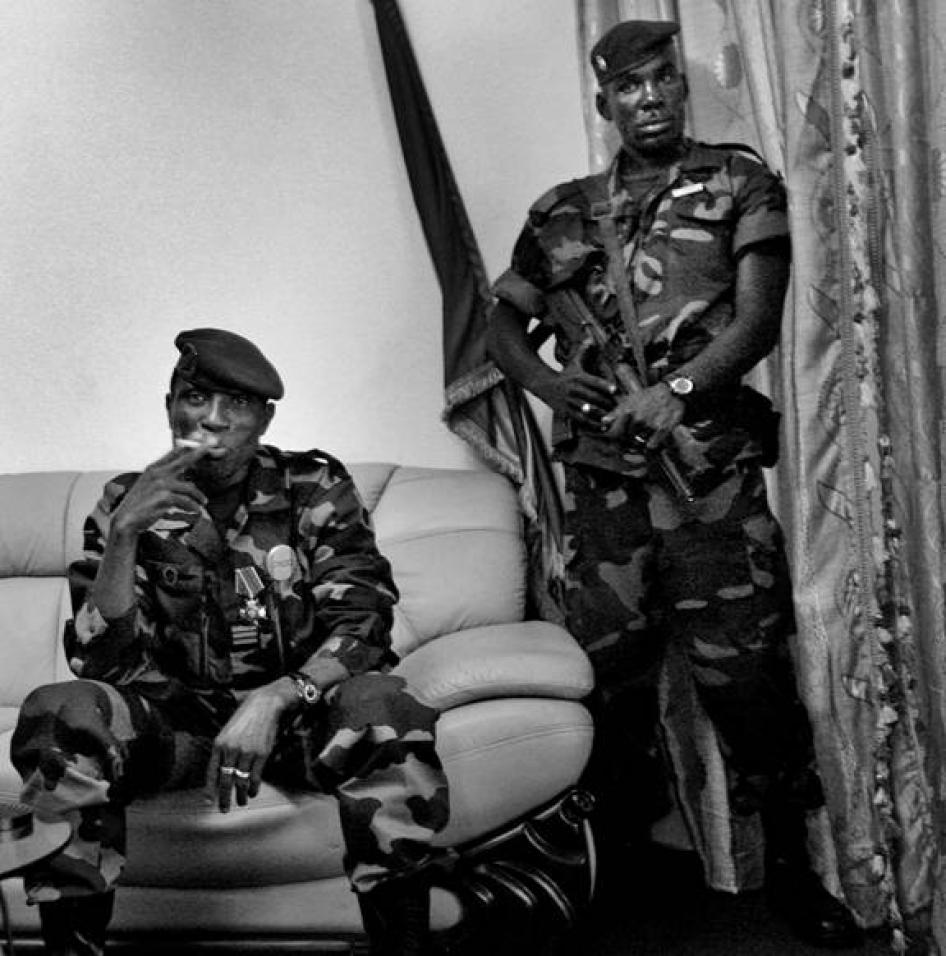

The bloodless coup in the hours after the death of President Conté on December 22, 2008, by a group of military officers calling themselves the National Council for Democracy and Development (Conseil national pour la démocratie et le développement, CNDD) brought hope for improvement in Guinea’s chronic human rights problems. The coup leaders, led by self-proclaimed president Captain Moussa Dadis Camara, pledged to hold elections in 2009 and to root out corruption.[25]

A bloodless coup in the hours after the death of President Conté on December 22, 2008, led by self-proclaimed president Captain Moussa Dadis Camara brought hope for improvement in Guinea’s chronic human rights problems, however his one-year rule was characterized by serious abuses, including the bloody September 2009 massacre of some 150 opposition supporters. © 2009 AP Photo/Jerome Delay

However, this hope was extinguished as the military government consolidated control of the country’s political and economic affairs, embezzled large amounts of state funds, failed to hold free and fair elections as promised, and steadily and violently suppressed the opposition. Throughout its one-year rule, the CNDD presided over a steady crescendo of abuses that culminated in the bloody September 2009 massacre of some 150 people and the public rape of over 100 female pro-democracy protesters.[26]

Throughout the CNDD’s year in power, heavily armed groups of soldiers engaged in widespread acts of theft, extortion, and violence, including raiding and robbing shops, warehouses, medical clinics, and homes in broad daylight and at night. Dadis, as he is commonly known, ruled by decree, undermining and sidelining the national judicial system. The CNDD obliged former government ministers and others accused of embezzling state funds or engaging in drug trafficking to appear in televised confessions, colloquially referred to as the “Dadis Show,” because of the CNDD president’s frequent appearances to conduct interrogations personally.

CNDD officials called for vigilante justice against suspected thieves and, on several occasions, overtly intimidated members of the judiciary in an attempt to influence the outcome of proceedings.[27] The CNDD also set up a parallel judicial system within Camp Alpha Yaya Diallo, a military camp that served as the ad hoc seat of government, where, as part of the “proceedings,” armed soldiers “invited” the accused and witnesses to stand before a panel of military officers. Hundreds of decisions for civil and criminal cases were pronounced and fines and penalties were assessed.[28] Meanwhile, the CNDD failed to investigate or hold accountable soldiers implicated in all classes of abuses.

As opposition parties increased their campaign activities in anticipation of promised elections, the CNDD increasingly restricted freedoms of assembly and expression by imposing bans on political activity, mobile phone text-messaging and political discussions on radio phone-in shows. The CNDD summoned to a military camp and reprimanded opposition leaders who criticized it.[29]

The September 28, 2009 massacre of opposition supporters was both the signature atrocity and defining moment of Dadis Camara’s regime. Responding to what had been a peaceful demonstration by tens of thousands of protestors gathered at the main stadium in the capital to protest continued military rule and Camara’s presumed candidacy in planned elections, members of the Presidential Guard and other security units opened fire on the crowds, leaving about 150 people dead. Many were riddled with bullets and bayonet wounds, while many others died in the ensuing panic.[30] Security forces subjected over 100 women at the rally to brutal forms of violence, including individual and gang rape and sexual assault with sticks, batons, rifle butts, and bayonets. Subsequently, the armed forces systematically attempted to conceal the evidence of the crimes by removing numerous bodies from the stadium and hospital morgues and allegedly burying them in mass graves.[31]

Guinea’s international partners harshly denounced the September 2009 violence. ECOWAS and the European Union (EU) imposed arms embargoes and the EU, United States, and the African Union (AU) imposed travel bans on CNDD members in addition to freezing their assets.[32] Speculation about whether the international condemnation and isolation of the CNDD regime would have forced Dadis Camara to step down was rendered moot by an assassination attempt by another military officer on December 3, 2009 that left Dadis Camara largely incapacitated.[33]

To sustain the momentum generated by the elections and fulfill the expectations of Guineans, Guinea’s new president, Alpha Condé, must take decisive steps to address the profound human rights and governance problems he has inherited. © 2010 Dirk-Jan Visser/Redux

After the medical evacuation of Dadis Camara from Guinea, the more moderate General Sékouba Konaté, then-Vice President and Minister of Defense, assumed power and began to bridge the increasingly volatile cleavages along ethnic, generational, and political lines within the army. Over the next 11 months, Guinean actors—including General Konaté and other members of the military and civil society who were determined to freely and fairly elect their leaders—ushered in, with the support of the international community, the political process leading to the presidential election of November 2010.

While the crisis of political transition set in motion by the CNDD coup has largely been addressed, it remains to be seen how seriously Guinea’s new government will provide redress for the victims of state-sponsored crimes committed in the recent past and how swiftly they will move to ensure that impunity does not find a home in Guinea’s Fifth Republic.

II. Accountability for Past Abuses

If the abuses under the First Republic of Sékou Touré had been dealt with—not through the execution of Touré supporters[34] but through proper trials—history would not have repeated itself during the Second and Third Republics [of Lansana Conté]. The September 28 [2009] violence of Dadis’s Fourth Republic is the direct result of the impunity of those who preceded him. Look at those who killed in September ‘09…they were the same ones who killed in 2007, who learned from those who had killed political opponents years before, who apprenticed and were party militants under Sékou Touré … it happened because they were never stopped. It’s time all this came to an end. —A family member of a victim of the Sékou Touré era[35]

The historical failure by successive regimes to ensure accountability for very serious crimes in large part served to embolden generations of perpetrators responsible for subsequent human rights abuses. Dismantling the architecture of impunity that has characterized Guinea’s violent history since independence and building a society based on the rule of law must be at the top of the agenda for both the new administration and Guinea’s international partners.

Importantly, the new government must bring to justice those responsible for the gross abuses of the past, most urgently the security forces responsible for the killing and raping of demonstrators in September 2009. It must also promptly re-establish and adequately support the national commission of inquiry responsible for investigating the 2007 killing of demonstrators that left some 140 dead.

To this end, Guinea’s international partners, notably the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), which opened a country office in Guinea in July 2010,[36] and the EU, which has taken the lead in reinforcing and reforming the judicial system, should advise and assist the Guinean government in establishing a witness protection unit, developing forensic expertise, and strengthening the independence of judges and prosecutors. Overall, these partners should work to enhance the expertise of national authorities and the domestic legal community in the investigation, prosecution, and defense of crimes in accordance with international standards.

Justice for the Victims of the 2009 Stadium Massacre, Sexual Violence and Other Crimes

Human Rights Watch and the United Nations-led International Commission of Inquiry concluded that the killings, rapes, and other abuses committed by the security forces on and after September 28, 2009, were part of a widespread and systematic attack, and as such they very likely constituted crimes against humanity.[37] The violence appears to have been premeditated and organized by senior officials of the then CNDD government.

As a result of tremendous domestic and international pressure, the government of Guinea committed to investigate and bring to justice the perpetrators of the September 2009 violence. On October 20, 2009, the then-Minister of Foreign Affairs Alexandre Cécé Loua affirmed that the Guinean national judiciary was “able and willing” to render justice for the crimes committed,[38] and in early 2010 appointed three investigating judges to the case.[39]

Pressure to investigate the violence was likely encouraged by the October 14, 2009 confirmation by International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo that the situation in Guinea was under preliminary examination by his Office.[40] In February 2010, the then-head of the Jurisdiction, Complementarity, and Cooperation Division of the Office of the Prosecutor, Béatrice le Fraper du Hellen, declared: “there is no alternative: either they [the government] must prosecute or we will.”[41]

Women at Conakry’s great mosque react as she they look for the bodies of family members and friends that were killed during a rally on September 28, 2009. © 2009 AP Photo

At the time of writing there has been scant information regarding progress on the investigation and no evidence of government efforts to locate the over 100 bodies believed to have been disposed of secretly by the security forces. Unfortunately, the military hierarchy failed to put on administrative leave, pending investigation, soldiers and officers known to have taken part in the September 2009 violence. Human Rights Watch is also concerned about President Condé’s appointment of two individuals implicated in the September 2009 violence into government positions: Lt. Colonel Claude Pivi who is the Minister of Presidential Security (Ministre chargé de la sécurité présidentielle) and Lt. Colonel Moussa Tiégboro Camara who serves as Director of the National Agency against Drugs, Organized Crime, and Terrorism (Directeur de l’Agence nationale à la présidence chargé de la lutte contre la drogue, les crimes organisés et le terrorisme).[42]

|

|

|

From September 28, 2009 video footage given to Human Rights Watch. Top to bottom:(1) Opposition supporters in Guinea demanding a return to civilian rule march on September 28, 2009, toward Conakry’s main stadium. (2) Security forces near the entrance to the September 28 Stadium in Conakry clash with protesters. (3) Survivors of the September 28, 2009 massacre tend to victim's bodies. (4) Guinean security forces beat an opposition supporter taking part in a march and rally. (5) Opposition supporters flee Conakry’s main stadium on September 28, 2009, after security forces stormed and opened fire on rally participants. (6)This image taken immediately following the September 28, 2009 massacre in Guinea shows bodies of victims lying at the entrance to Conakry’s main stadium.

However, officials from the ICC Office of the Prosecutor who visited Guinea in February, May, and November 2010, and March 2011, to assess progress made in national investigations praised both the technical ability of the investigating judges and their demonstrated independence and freedom from government interference. In May 2010, the ICC officials reported that investigating judges had already interviewed 200 individuals and were satisfied with progress made in the investigation.[43] Guinean sources interviewed in June 2010 told Human Rights Watch that as of that time, two individuals had been detained for their alleged involvement in the September 2009 crimes.[44] Since then, a third person has been charged with crimes related to the September 2009 killings and rapes[45] and on January 19, 2011, Interpol issued a Red Notice (red notices allow an already issued domestic warrant to be circulated worldwide with the request that the wanted person be arrested with a view to extradition) for Aboubacar Sidiki Diakité, the then-head of the Presidential Guard, or red beret troops, who Human Rights Watch and the international Commission of Inquiry identified as one of those most directly implicated in the September 2009 crimes.[46]

On April 1, 2011, following a visit to Guinea, Bâ Amady, head of international cooperation in the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor, issued a declaration recognizing the cooperation of the Guinean authorities and the new government’s commitment to bringing perpetrators to justice. However, he urged the government to increase accountability efforts and reiterated the ICC’s responsibility to take action if the government fails to do so promptly and adequately.[47]

A policeman stands next to the bodies of people shot dead by Guinea junta forces on September 28, 2009 in front of the Conakry great mosque. © 2009 Seyllou/AFP/Getty Images

Captain Moussa Dadis Camara, then-chief of the ruling junta, arrives for celebrations commemorating the Republic of Guinea's independence day on October 2, 2009. © 2009 Reuters

There is considerable disagreement among Guinean human rights defenders, victims, and others about whether the Guinean judiciary or the ICC should assume responsibility for investigating and trying those responsible for the September 2009 crimes. Guinea ratified the Rome Statute, the ICC’s founding treaty, on July 14, 2003. As such, the ICC has jurisdiction over war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide possibly committed in Guinea or by nationals of Guinea, including killings of civilians and sexual violence.[48] However, it is a court of last resort; under the principle of complementarity, it intervenes only when national jurisdictions are unwilling or unable to investigate or prosecute such crimes.[49]

Some members of the Guinean judiciary and Guinean Bar Association told Human Rights Watch they were confident in both the political will and the technical ability of the Guinean judiciary to deliver justice for the September 2009 crimes. As noted by a high-level Guinean judicial official familiar with the investigation, “[w]e are capable of ensuring justice is served in this matter. Rest assured we will leave no stones unturned in this investigation; we are looking at everyone—near and far.”[50]

However, this optimism is not shared by many Guinean human rights defenders, victims, and others who firmly believed the ICC should take responsibility for the case. A representative from a group of the September 2009 victims noted that “[t]here are too many things working against a sound and neutral judgment here in Guinea… We have our hopes in the ICC.”[51] Others were more cynical: “The government is neither capable nor willing to try the case. The three judges were appointed to avoid the case going to the ICC until the international community was distracted or lost interest; to make the world believe they’re serious about the case, but they’re not.”[52]

Human Rights Watch believes that the primary obligation to provide accountability for the perpetrators of the September 2009 violence rests with national authorities in Guinea. The ICC’s authority to act only when national authorities are unable or unwilling respects the principal role of national courts and encourages the development of credible and independent domestic judicial systems. Holding trials in Guinea would also provide the communities directly affected by the crimes access to the proceedings and serve as a deterrent to would-be perpetrators. This point was supported by several Guinean judges, lawyers and human rights defenders, one of whom noted that “[s]eeing the military humbled before a court of law would be very important for ordinary Guineans who have thus far seen them get away scot free.”[53] A Guinean judge reiterated this position:

Having the trial here in Guinea would serve as a stark reminder to currently serving military [officers] about what awaits them if they abuse human rights. It would also allow us as a people to regularly reflect on the role the judiciary should play in a proper democracy.[54]

Human Rights Watch has nevertheless identified several key challenges to ensuring that domestic investigations and prosecutions are conducted fairly, impartially, independently, and effectively. These challenges include deep-seated weaknesses within the judicial system, lack of adequate security for judicial personnel, the absence of a witness protection program, existence of the death penalty, and lack of a domestic law within the Guinean criminal code against crimes against humanity and torture. In order to ensure justice for the serious international crimes committed in 2009, the Guinean authorities must promptly and credibly address these challenges. Human Rights Watch believes Guinea and its international partners should push for the simultaneous progression of the investigation and trial of those responsible for the 2009 violence and much-needed improvements in the judicial system and the legislative framework which underpins it.

Weaknesses within the Judiciary

Weaknesses within the Guinean judicial system that could undermine the quality of the investigation and prosecution of those implicated in the September 2009 violence include lack of independence from the executive, inadequate material resources to the judiciary, which renders personnel vulnerable to manipulation and corrupt practices, and inadequate knowledge of international law. These weaknesses are largely the result of a pattern of neglect and manipulation of the judiciary by successive governments and are dealt with in detail in a subsequent section of this report.

Dr. Thierno Maadjou Sow, president of the Guinean Organization of Human Rights (Organisation guinéenne de défense des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, OGDH), described his concerns about the ways in which these problems could undermine efforts to achieve accountability for the September 2009 crimes:

We have serious doubts about the ability of the Guinean judiciary to handle this dossier. The technical ability of our judges to handle international crimes with respect to law and procedure is not there. The perpetrators will have very strong defense lawyers, and the Guinean government needs to be prepared, or else they will lose the case and our efforts to combat impunity would backfire. There are so many things which undermine the independence of our judges including their conditions of service; they are very poorly paid which leaves them open to being bought off.[55]

Judicial personnel interviewed by Human Rights Watch acknowledged these weaknesses but believed they could be addressed through a combination of better funding and management of the judiciary together with technical assistance, training and funding from Guinea’s international partners. Several judicial personnel specifically noted the urgent need for a witness protection program, increased capacity in forensics, notably laboratories and expertise in ballistics and conducting exhumations to identify victims, and training in investigating and adjudicating international crimes.[56] They saw the 2009 case as an opportunity to make much-needed improvements in a judiciary that has suffered for decades from extreme state neglect.

Security of Judicial Personnel and Witnesses

Human Rights Watch is concerned about what appears to be inadequate security provided to judges and witnesses, and urges national authorities to address this problem immediately. The potential threat would likely come from members of the security forces who were either directly implicated in the September 2009 violence or who were opposed to their colleagues being tried. The threat would likely take the form of threats and intimidation, or the destruction of evidence.

Judicial personnel, human rights defenders, and those close to the investigation echoed this concern, highlighting the ways in which the vast majority of officers and soldiers implicated in the September 28, 2009 violence are still members of the army and gendarmerie. A Guinean human rights defender explained:

We know very well the problems with military who can throw around a lot of influence. Do you really think those judges could convoke to testify the likes of Captain X or Major X? Things may seem calmer now, but those boys are still lurking around. We don’t want our people to be double victims – of both the stadium violence and then on account of talking to the judges.[57]

Trials of serious international crimes are extremely sensitive and can generate considerable public emotion, as well as attract interference in the judicial process. These considerations underscore the importance of adequate security, including at the facilities where proceedings are being conducted, for staff working on the proceedings, for accused and defense counsel, and for witnesses.

The Ministry of Justice must adequately resource, protect, and support the three investigating judges, any judges who may conduct trials or other hearings, and other judicial personnel involved in the cases related to the September 2009 violence. Protective measures for judges are particularly vital to preserve their independence and ensure the integrity of the judicial process. Any perception that the judges are at risk may have a potential chilling effect on others who might participate in the proceedings, including victims and witnesses. Inadequate security could thus undermine the effectiveness of proceedings, as well as derail efforts to establish the rule of law in the long term.

The establishment of an effective witness protection program must be a top priority for the government of Guinea. This need has, until the present, been addressed informally by foreign diplomatic missions[58] and humanitarian organizations, which have provided protection, funding, and evacuation to those in need. A formal witness protection program should be implemented through a legal framework that satisfies key criteria including risk assessment, as well as provision of physical and psychological protection outside the court at all points before, during, and after testimony. The legal framework should also facilitate appearance before the court, including protective measures such as the use of pseudonyms and provision of private courtroom sessions to protect both the witnesses and defendants’ right to a fair trial; and measures to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and autonomy of the proceedings.[59]

The Need for Legal Reforms

Ministry of Justice personnel affirmed that those implicated in the September 2009 violence would be tried for the crimes of murder, assassination, rape, and destruction of property, among others.[60] Some judges and lawyers interviewed believed these charges were sufficiently serious to represent the seriousness of the crimes. As noted by one Guinean judge: “Our penal code can pronounce the death penalty for some of the infractions the alleged perpetrators of the September 2009 crimes will be charged with. You ask about gravity of the crime; is this not a reflection of how serious these crimes are? How much more serious can we get?”[61]

The seriousness of these charges highlights the need for legislative reform to address two key issues: the existence of the death penalty and the lack of a domestic law that criminalizes crimes against humanity and torture and establishes liability for the 2009 crimes, among others. Human Rights Watch urges the new government, human rights groups, and Guinea’s international partners to push for these much-needed reforms.

Human Rights Watch opposes the death penalty in all circumstances due to its inherent cruelty. In addition, imposing the death penalty can send the message that the Guinean judiciary is exacting vengeance rather than rendering justice. Moreover, international human rights law, as codified in Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), favors the severe restriction, if not the outright abolition of capital punishment.[62]

Recent state practice recognizing that the death penalty violates basic human rights has fuelled a growing movement around the world to eliminate it.[63] The statutes of various international and hybrid international-national justice bodies, as well as the Rome Statute, do not permit the death penalty. The divergence of these international standards with the Guinean penal code regarding the death penalty could mean that in the case of an ICC investigation in Guinea, those prosecuted as “persons bearing the greatest responsibility” by the ICC would receive less severe sentences than lower-level perpetrators prosecuted at the domestic level.

Lack of Law Criminalizing Crimes against Humanity or Torture

Existing Guinean law does not adequately capture the nature of crimes committed in September 2009. To ensure that charges can be brought that reflect the scope and responsibility of the crimes committed, Guinea should act swiftly to enact legislation implementing the Rome Statute—including its core crimes and modes of liability, such as command responsibility—and codify a specific crime of torture.

As defined under international law, crimes against humanity go beyond multiple criminal acts such as murder and rape and are committed as “part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population.”[64]

Furthermore, the prosecution of such grave international crimes as though they were merely serious ordinary crimes does not sufficiently address the conduct and responsibility of those involved in their commission and would fail, among other things, to expose the criminal structure beneath. Appropriate conceptions of criminal responsibility, for example “command responsibility,” are necessary for accountability at all levels, including for those whose responsibility extends beyond physical commission of the crime. For example, the concept of “command responsibility” enables military commanders and others in positions of authority to be held criminally liable when crimes are committed by forces under their effective command and control, when they should have known about the crimes, and when they fail either to prevent the crimes or prosecute those responsible. Guinea’s current penal codes are not adequately developed with respect to these international and human rights law concepts, presenting an additional judicial challenge for September 2009 accountability trials.

|

Protesters carry the body of a demonstrator who was killed by security forces during a demonstration on January 22, 2007 in which tens of thousands of Guineans in the capital city of Conakry attempted to march to the National Assembly building. The individual pictured here was one of at least 129 killed by security forces during the January and February, 2007 strike violence. © 2007 AFP/Getty Images |

Independent National Commission of Inquiry into the 2007 Violence

The new government should also re-establish the now-defunct Independent National Commission of Inquiry into the 2007 violence. Once this commission has completed its work and drafted its recommendations, those perpetrators deemed most responsible should be held accountable in accordance with international fair trial standards.

During the 2007 violence security forces fired directly into crowds of marching demonstrators protesting against bad governance and deteriorating economic conditions, and at demonstrators gathered near Conakry’s November 8 Bridge. Security forces later ransacked the offices of the trade unions that organized the strike and arbitrarily arrested, beat and threatened to kill journalists, union leaders, and many others. Security forces killed an estimated 130 people and wounded about 1,700 others.

The national commission of inquiry into the 2007 strike-related violence was established by the National Assembly in May 2007, for which 19 commissioners were sworn in. However, according to the commission’s well-respected chair, Mounir Hussein, the Guinean government did not fund it or provide logistical support.[65] The commission’s mandate expired in January 2009. It did not conduct any investigations.

III. Truth-Telling Mechanism

Guineans need to critically evaluate the behavior and abuses committed by each and every regime, and explore why history is repeating itself. A truth commission would help arrest the gangrene; it would help us put to one side what divides us, and reflect on what unites us. We must also take a closer look at the issue of ethnicity, which for decades has been used to control, divide, and sow mistrust and hatred among Guineans. We must also look at the role economic crimes and profiteers, who have operated throughout every regime, have played in benefitting from Guinea’s resources at the expense of the population.—Gadiri Diallo, executive member of the Guinean Human Rights Organization (OGDH)[66]

Human Rights Watch believes the new administration should establish a truth-telling mechanism for several key reasons. First, it could help illuminate under-exposed atrocities committed since independence, notably during the reign of Sékou Touré. Second, this mechanism could explore the dynamics that gave rise to and sustained successive authoritarian and abusive regimes. Third, it could make recommendations aimed at ensuring better governance and preventing a repetition of past violations. Civil society leaders, human rights activists, and ordinary citizens interviewed by Human Rights Watch supported the establishment of a truth-telling mechanism.[67] One civil society leader expressed concern about what he referred to as “Guinea’s memory problem” and how a truth commission could help address it:

No one talks about what happened during the Touré years, or Conté’s killing of all those demonstrators in 2007; I went to an anniversary memorial for the victims of 2007 and hardly anyone showed up; people had already forgotten about it! Even now, no one, not even civil society is actively pushing for justice for the stadium massacre! I used to think there should be a line in the sand between what happened during our painful past and the future, but now I’m convinced we need to talk about, not forget, these things.[68]

The period of history most shrouded in secrecy and which could most stand to benefit from a truth-telling exercise is the regime of Sékou Touré. Although this period ended more than a quarter of a century ago, Sékou Touré’s 26 year reign left an indelible mark on Guinea and created a legacy of distrust and fear for those attempting to call their government to account. One family member of a victim noted how, in the 2007 and 2009 episodes of violence, “the images of demonstrators being gunned down in the streets or stadium flew around the globe via the internet and mobile phone,” whereas the extent of what happened during the Touré years “remains largely hidden.”[69]

Members of the Guinean Camp Boiro Victim’s Association (L’Association Guinéenne des Victimes du Camp Boiro, AGVCB), which represents the victims of the Touré era, noted that “the views and needs of the victims of the atrocities committed during the Sékou Touré years have never been properly considered. There is no monument to the victims; no official recognition, no report. We want recognition of who the perpetrators were, of who the victims were, of where their remains are, and of how they and their families have suffered.”[70]

One man, whose father disappeared during Sékou Touré’s regime, supported the idea of a truth-telling commission, not only to uncover hidden truths, but also to remind younger Guineans of what occurred during the Sékou Touré regime:

Our children are forgetting. They need to know people were hanged from bridges; that two sons of the same mother were killed on the same day; that countless people were tortured to death inside Camp Boiro and elsewhere while others were forced to eat rats, even their own feces, to survive. They need to be reminded so they will never allow history to be repeated.[71]

The era’s persecution of members of the Peuhl ethnic group in particular left a legacy of anger and distrust, which played out with deadly consequences during the presidential elections. As recently as October 2010, ethnic tensions erupted following a report that Malinké supporters of presidential candidate Alpha Condé had been poisoned by Peuhl supporters of opposing candidate Cellou Dallein Diallo. The inter-communal violence, which left several dead, spread to a number of cities and continued into November 2010.

One young woman described why she believes a truth commission could help Guineans address what she characterized as “the banality of violence:”

When I was child in Labé, I recall so well rushing to see the bodies of two men hanged near the stadium. They remained there all day. We as children ran to see them and watched as people whacked them with sticks and swore at them. At the time, I was shocked, but over the years the killing of our people has became less shocking. We wipe our memory of it and accept that it’s just one of those things. Over time the fear is transformed into passivity. As we’ve seen, living without memory is dangerous.[72]

|

Four of the dozens of people that were hanged on January 25, 1971. Pont du 8 Novembre in Conakry, from back to front: Ousmane Baldet (minister of finance); Barry III (secretary of state); Magassouba Moriba (minister); Keita Kara Soufiana (police commissioner). © Camp Boiro Memorial http://www.campboiro.org |

Truth commissions can serve important needs of accountability and reconciliation that are not addressed by prosecutions alone. For example, South Africa’s truth and reconciliation commission has been heralded as a vital aspect of national healing and the country’s successful transition out of apartheid. Sierra Leone’s truth commission was credited with helping identify some of the issues that gave rise to that country’s brutal armed conflict. As such, they are held up as an exemplar of the benefits of restorative and transitional justice mechanisms, which can respond to victim and community needs in ways that punitive justice alone may not. Nonetheless, as a matter of both treaty and customary international law, there is a duty to prosecute serious international crimes and pursue individual criminal responsibility. While truth commissions can be a meaningful complementary process, they are, by themselves, an inadequate response to grave human rights abuses.

IV. Strengthening the Guinean Judiciary

We in the judiciary lack even the most basic things needed to conduct an investigation or manage a case. It is easy to accuse a judge of being corrupt but what is he to do when he needs to buy paper, pens and dossier folders, to photocopy documents, or fuel his vehicle? All this affects the ability of judges to remain impartial; to conduct themselves professionally. –Kpana Emmanuel Bamba, President of the Guinea Chapter of Lawyers Without Borders[73]

The marginalization, neglect, and manipulation of the Guinean judiciary has led to striking deficiencies in the sector and served to fuel the impunity enjoyed by the perpetrators of all classes of abuses and human rights crimes. As observed by a lawyer interviewed by Human Rights Watch, “The Guinean judiciary has very serious problems of legitimacy, accessibility, speed, capacity and impartiality.”[74]

The Guinean judicial system is broadly based on the French civil law system. There are three levels within the hierarchy of courts hearing cases involving crimes (as opposed to lesser offenses equivalent to misdemeanors [contraventions and délits]).[75] A first instance court for crimes is called cour d’assises. Its decisions may be appealed to the cours d’appel (appeals court) and finally to the Cour Suprême (Supreme Court). There are only two cours d’assises and two cours d’appel in Guinea, one each in Kankan and Conakry. The single Supreme Court sits in Conakry and has until now been the Supreme Court for all legal matters, including administrative, financial, and judicial. Guinea’s new constitution further provides for a constitutional council (conseil constitutionnel), audit court (cour des comptes), and judicial supreme court (cour de cassation).[76]

The civil law system’s courtroom consists of a panel of judges (juges du siège), assisted by a jury at the cour d’assises level. The case against an accused is presented by public prosecutors (juges du parquet) acting on behalf of the State and answerable to the Ministry of Justice. Defense attorneys (avocats de la défense) represent the accused. A case is initiated upon completion of either a police investigation or a judicial investigation (information judiciaire) led by investigating judges (juges d’instruction).[77][78]

Based on interviews with members of the Guinean Bar, magistrates, judicial personnel, UN and EU personnel, Human Rights Watch identified the following key problems within the Guinean judicial system. In order to facilitate accountability for past abuses and deter future ones, the new government must take urgent steps to address them.

Insufficient Budget for the Judiciary

According to Ministry of Justice personnel, national budgetary allocations for the judiciary and the corrections sector have, for several years, stood at less than 0.5 percent.[79] The 2010 budgetary allocation was a mere 0.44 percent,[80] with similar allocations in previous years – 1.32 percent, 0.37percent, and 0.23percent, respectively for 2009-2007.[81] According to Ministry of Finance personnel interviewed by Human Rights Watch, as well as an in-depth study of the judiciary by the European Union, the disbursement rate to the Ministry of Justice of this very limited allocation is furthermore very low, with some jurisdictions going years without receiving any budgetary funds.[82]

A regional expert on justice sector reform noted that an acceptable budget allocation to the judiciary should be at least 5 percent, adding, “less than one percent is low, even for this region [West Africa].”[83] As noted by a high-ranking official from the Ministry of Justice, “I think it’s pretty obvious; the Ministry of Justice is the bottom of the ladder in terms of state priorities.”[84]

Several members of the legal profession interviewed by Human Rights Watch believed that the low budgetary allocation to the judiciary was strategic. As noted by Mohamed Sampil, the outgoing president of the Guinean Bar: “Successive governments have shamefully neglected the needs of the MOJ…We don’t believe this chronic underfunding is an accident.”[85] Another lawyer explained why: “The political elite has for years benefitted from a weak judiciary. If judges could resist corrupt payoffs, if the judiciary were strong, it is these people—the ministers and those who benefit from their patronage network—who would be on trial!”[86] A vast array of other problems identified by those interviewed emanated from the insufficient fiscal support of the justice sector.

Inadequate Funds for Operations, Staffing and Infrastructure

In conversations with Human Rights Watch, judges, lawyers, legal clerks, and correction workers complained bitterly of inadequate funds to conduct judicial investigations; adequately staff, supply, and run their offices; and feed, care for, and transport prisoners to court. They said Guinea also needed additional courtrooms, forensic labs, and a legal library.

The dire need to modernize operations, evidenced by the lack of computers, disorganized or non-existent record keeping, and the “archaic” method of court reporting (done by hand) was largely credited with creating huge backlogs and contributing significantly to the high numbers of detainees in extended pre-trial detention. Furthermore, many courthouses throughout the country are in need of repair or renovation after being pillaged, burned, damaged, or destroyed during protests or the 2000-2001 cross-border incursions by armed groups from Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Those interviewed by Human Rights Watch agreed that these chronic deficiencies adversely impact Guineans’ access to justice. According to Kpana Emmanuel Bamba, president of the Guinea Chapter of Lawyers Without Borders:

The court system has become a simple calculation of costs: They don’t have the money to transport the victims and accused to the trial, to pay clerks to take notes of the proceedings, to hire guards for the security of the courtroom, the list goes on and on. Proper organization and performance of the trials requires more expenditure by the State, and the Ministry of Justice doesn’t have enough in its budget allocation to support this. Even the two criminal courts do not have the financial resources to operate functionally. The State thus far apparently feels fair trials aren’t important enough and has been satisfied to keep the accused in prison indefinitely instead.[87]

Mohamed Sampil, the outgoing president of the Guinean Bar, added:

It is fundamentally a financial and logistical problem. The justice sector in Guinea cannot pay for justice! The budget allocated by the government is too low a percentage, so that the courts have become an institution that doesn’t have the infrastructure and logistical support to function properly. For example, there isn’t enough money even to transport the accused to the courthouse. Without dedicated vehicles, judicial personnel are often obliged to bring detainees to trial in a taxi. The Ministry of Justice cannot financially afford to bring the cases awaiting trial, and so people languish in prison. The national budget must be reformulated to carry out justice properly, including the creation of better jurisdictional accessibility—such as more courts sitting for trials closer to those who need them—and free legal counsel for those who cannot pay.[88]

Guinea is also in dire need of a case management system. Humanitarian workers and lawyers said that many cases of extended pre-trial detention occur because of ill-kept records. One man, who was detained, charged with assault, tried in absentia because the prison lacked a vehicle to transmit him to trial, and ultimately acquitted in 2005, nevertheless spent two and a half years in jail after his acquittal because the paper authorizing his release was never transmitted to the prison by the court.[89] Prison clerks demanded bribes from detainees to investigate their complaints. Other prisoners spent extra months or years in detention after having served their sentences due to what one lawyer described as “a combination of poor record keeping, incompetence, indifference, and corruption on the part of court and prison officials.”[90]

Numerous judicial personnel noted that the need for additional courthouses and trained personnel to staff them, was most urgent within the criminal court (cour d’assises), which deals with criminal offenses that carry a maximum sentence exceeding five years.[91] Those interviewed also stressed the need for the existing courts to sit more regularly, as mandated by law. At present, the two cours d’assises—in Conakry and Kankan—often go years without sitting for a session. The resulting extended pre-trial detention and case backlogs represent dire obstacles to access to justice. As Mohamed François Falcone of the anti-corruption commission said:

Each year, the cours d’assises are supposed to have special sessions to judge all crimes committed during a given period of the year. But in practice these sittings are very irregular. The budget allocation to the justice sector is clearly to blame. The irregularity in court sitting clearly translates into irregularity of justice, with procedural delays leading to prolonged detention. When someone has to wait two years to go to trial, it is a clear human rights abuse. The judiciary must better protect detainees. This has to begin with strengthening the judiciary’s capacity to actually hear cases, otherwise no justice is possible for Guinea’s citizens.[92]

While few ministries in Guinea’s government are well resourced, the dire lack of funds for the criminal justice system means that Guinea’s residents are denied the most basic civil and political rights protections, including due process.

Inadequate Remuneration of Judges

Monthly salaries for Guinean judges range from about 300,000 GF (US $45) to 1,000,000 GF (US $151), with the median around 500,000 GF (US $76).[93] The monthly cost of living in Conakry for a family of four is estimated to be about 1,520,000 GF (US $230). In some instances, judges’ salaries are lower than those for equivalent government posts in other sectors, such as the executive or legislature, or even of their technical subordinates, the judicial police.[94] However, in most sectors civil servants have approximately the same salaries, in accordance with their level of training and education. Their salaries are in stark contrast with those of members of the military. According to Mohamed François Falcone of the anti-corruption commission, the highest salaries in Guinea go to the army: “an average salary in the army is about 2,000,000 GF [US $302], meaning they are paid more than twice that of the highest paid judge. Civil servants, including judges, are paid too low to do their job correctly and survive. They turn to corruption instead.”[95]

Judicial sector workers interviewed explained that the lack of adequate compensation for judges both undermined their independence and left them open to the solicitation or taking of bribes.[96] One judge with 36 years of service complained: “…my salary of 1 million GF (US $151) per month is simply not enough to support a man and his family; to pay the electricity, the water, and school fees. If one day a judge’s child is sick, it is not just temptation or weakness of character that makes him engage in unprofessional behavior.”[97]

Kpana Emmanuel Bamba, president of the Guinea Chapter of Lawyers Without Borders, further explained:

Judges are not sufficiently paid. The military, however, is paid well—twice as much as judges—and regularly, including bonuses such as five sacks of rice each month! The salaries of judges are archaic and their offices are in poor conditions because of inadequate finances. It leads to corruption in the justice system, with judges accepting payment for deciding a case a particular way. Judges are not paid enough to pay rent, educate their children, take a car to go to the office, etc. The State is responsible for paying them and if it paid them adequately, they would be able to carry out justice transparently. Corruption is thus not just the judges’ fault but also the State’s. We must make this a priority in Guinea now, otherwise will keep seeing violations of justice and human rights.[98]

The outgoing president of the Guinean Bar Association said:

Judges insufficient salaries are completely derisory and corrupting, because judges feel the only option they have absent a decent salary is to turn to corruption if they want to keep their families alive. This doesn’t justify corruption, of course; the position of judge is guided by oath and virtue, but it is hard to be true to it given the current levels of pay. For the justice system to be fair and functional, judges’ salaries must be increased. The failure to correct this problem leads to endemic corruption and will have enormous implications for good governance.[99]

Lack of Funds for Defense

Insufficient support for the judiciary also impacts the right to defense. There are no criminal defense lawyers affiliated with the Ministry of Justice. Any indigent adult defendant accused of a more serious crime and children accused of any class of crime have a legal right to defense counsel provided by the Guinean Bar, which by law is supposed to be remunerated by the Ministry of Justice. In practice, defense lawyers are rarely made available, largely because the Bar itself is under-resourced, having rarely been allocated funds by the Ministry of Justice.[100] Lawyers are supposed to receive 500,000 GF (US $76) per dossier.[101] However, according to several lawyers interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the sum is far too low for the work they claim is required for the cases, and lawyers are rarely paid. One lawyer noted, “Indeed it’s considered by us to be more like a gratuity.”[102] More typically, defense lawyers are paid only if the client can afford it. Kpana Emmanuel Bamba, president of the Guinea Chapter of Lawyers Without Borders, said the right to defense is often ignored: “The Ministry of Justice has grossly inadequate funds for judicial assistance. The absence of legal representation for indigent citizens is a real problem in Guinea; lawyers are rarely being paid for this function, a safeguard of the people’s rights.”[103]

This impacts directly on the quality of any defense counsel received by a defendant which many human rights defenders characterized as sorely lacking. A lawyer who worked within the Maison Centrale in 2007 cited as an example the case of a man on death row who said he had met his assigned lawyer for the first time at his trial. “His lawyer had never even bothered to meet with or interview him before the trial. At the trial the man was convicted and sentenced to death.”[104] Meanwhile, those tried for less serious crimes at the lower courts (the vast majority of cases) rarely have legal representation.[105]

Independence of the Judiciary

Poor conditions of service and political interference regularly conspire to undermine the independence of the judiciary in both civil and criminal matters. Judges, prosecutors, and other lawyers told Human Rights Watch that during both the Conté and the CNDD regimes, they were regularly subjected, and in many cases, succumbed to pressure on how to act in a given case by members of government, the military, or businessmen.[106] This has contributed to the widely held perception that the powerful are above the law. Judicial personnel refusing to succumb to the pressure have at times been “punished” through transfers to other jurisdictions, often far from their home.[107] One judge explained that: “Under Conté we frequently got calls or they sent someone—at times a member of the army or a minister—to ‘discuss’ a case and let us know of their desired outcome.”[108] A lawyer representing a businessman from a mining company who had won a case against a competitor, said he received threatening phone calls, was followed by the military, and a group of armed soldiers stormed his office and threatened to detain him, his wife and his children unless he stopped representing his client, whose case was on appeal. The military similarly threatened the judge in the case, which occurred during the CNDD administration.[109]

The potential for independence of the judiciary will be increased once the Superior Council of Judges (Conseil supérieur de la Magistrature), responsible for the discipline, selection, and promotion of judges, is established.[110] Human Rights Watch urges the government to constitute this body as quickly as possible.

Insufficient Numbers of Lawyers

The rights of those who have been victim to or are accused of crimes, or who otherwise encounter the Guinean justice system are often left unprotected due to the limited number of lawyers, particularly outside of the capital Conakry. According to the head of the Guinean Bar Association, there were at this writing only 187 members of the bar, all but 10 of whom were based in the capital.[111] Nzérékoré, Guinea’s second largest city with a population of 225,000 has four lawyers, while Kankan, Guinea’s third largest city with a population of 200,000, has only three.