Image 2: Judge Anne Kerber (center) stands in a hall of the regional court in Koblenz, Germany on June 4, 2020. © 2020 Thomas Lohnes/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

Image 2: Judge Anne Kerber (center) stands in a hall of the regional court in Koblenz, Germany on June 4, 2020. © 2020 Thomas Lohnes/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

It was a chilly, overcast February day in 2015 when Anwar R. walked into a Berlin police station to file a complaint. An alleged former Syrian military intelligence officer now living in Germany, Anwar R. believed that Syrian government operatives were following him in Berlin, he said. He feared being kidnapped. At the bottom of his written complaint, he signed his name using his military title – “Colonel.”

The police were unable to find evidence he was being followed. But they did carefully note the slivers of information Anwar R. shared about his alleged intelligence career.

Today, Anwar R., 58, is on trial in Koblenz, a small city in western Germany, charged with crimes against humanity allegedly committed before his defection in 2012. The trial began in April 2020. He is charged with 4,000 counts of torture, 58 killings, and for rape and sexual assault committed while he allegedly headed investigations at a military intelligence facility known as “Branch 251” in Damascus. The verdict and sentence are expected in January.

Anwar R. (Germany’s privacy laws require that an accused’s full name be withheld) is the most senior alleged former Syrian government official to be tried in Europe for crimes against humanity committed in Syria.

This trial came about thanks to a combination of individual initiative, dogged group efforts, and innovative technology – as well as sometimes chance encounters and human foibles.

But the stage for the Koblenz trial was set long before Anwar R.’s arrest in 2019. German authorities have been investigating crimes in Syria since the uprising in the country began in 2011. Then, in 2015, large numbers of Syrians from all over the country arrived in Germany. While seeking a fresh start in a new home, their personal histories from war-torn Syria could not be erased. This also meant that previously unavailable victims, witnesses, material evidence – and even some suspects – came within reach of European judicial authorities.

Another essential element: Germany’s laws allow serious crimes to be tried there, even without a German connection to the crimes, a principle known as “universal jurisdiction.” It can feel like sheer chance that this trial took place.

This trial is unique in other ways, too.

Roughly a decade after the war began, fighting in Syria has nearly stopped. President Bashar al-Assad and other government officials have tightened their grip on power and recaptured most of the country. Accordingly, when it comes to criminal responsibility for crimes in Syria, the idea of fair trials within the country is inconceivable. At the same time, attempts to involve the International Criminal Court or ad-hoc international tribunals have been thwarted. With zero accountability, grave abuses by all sides continue unimpeded. Meaningful justice in Syria – for now, at least – is not possible.

So why does a case against an alleged mid-level intelligence operative thousands of miles away from where the atrocities took place even matter?

The Trial

a. The Witness

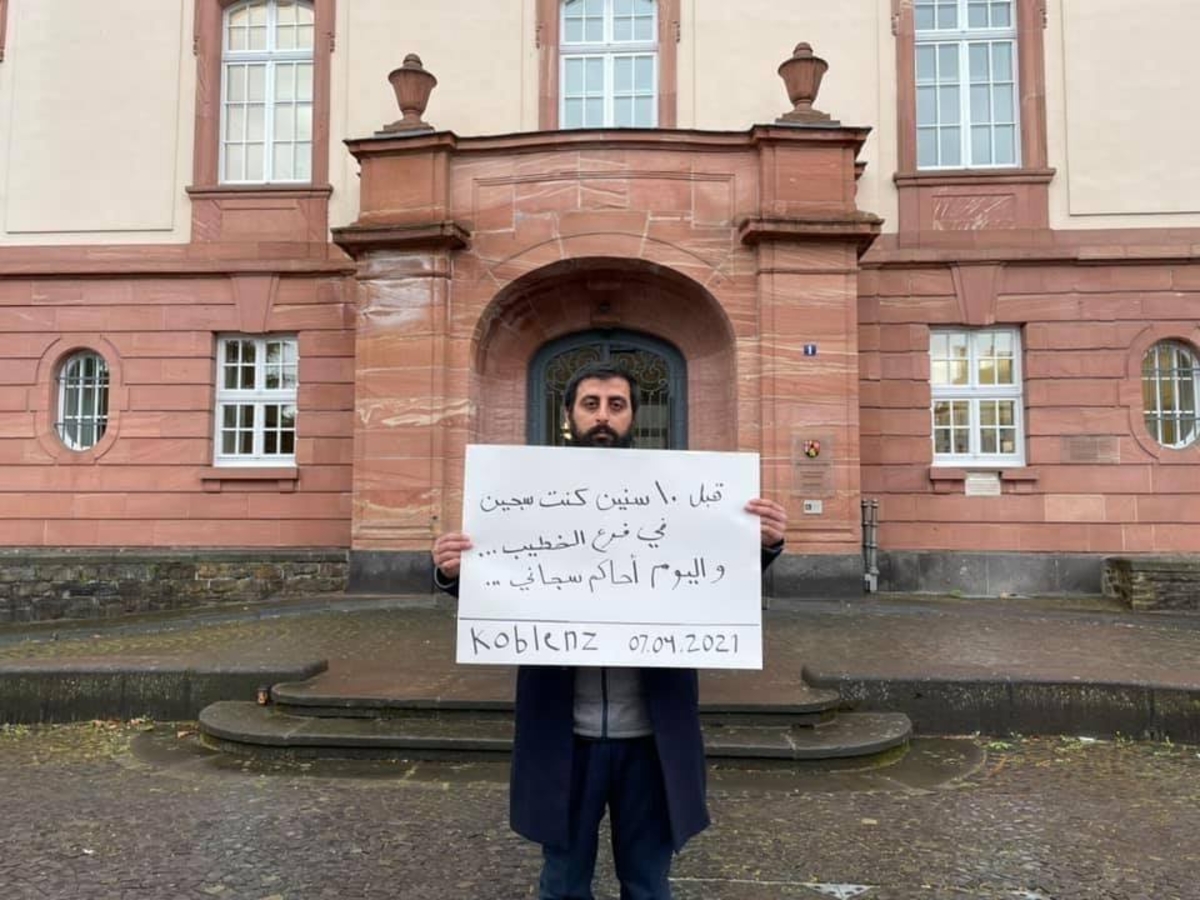

Amer Matar, a Syrian journalist and documentary filmmaker, walked into the courtroom in Koblenz to confront the man who he alleges had tortured him a decade earlier. It was April 7, 2021 – day 67 of the hearings against Anwar R.

Matar, 34 at the time, sat at a table facing the five judges. Anwar R. was to his right at another table.

“I made the conscious choice from the beginning not to direct any of my speech or any of my testimony toward Anwar R.,” Matar told Human Rights Watch in October 2021. He also told us that he had long repressed what he said happened to him at Branch 251. But in court, as he prepared to address the judges, the details of the room – the tall windows, the clear Covid-19 dividers between desks, the wall of books behind the judges – faded. “I was back in jail in the prison cell and Syria,” he said.

Amer Matar — عامر مطر

When antigovernment protests erupted in Damascus, Syria’s capital, in early 2011, Matar threw himself into the fray, he testified in court, reporting on the demonstrations and discussing them on television.

Then, on March 28 that year, security forces raided his home, he told the court. In that moment, Matar thought his life was over, he said. Syrian security forces hit him, insulted him, and searched everything. He was arrested, and his laptop and other equipment were seized and searched, he testified. Then he said he was taken to Branch 251.

On his laptop, the security services found a photo he had taken of Anwar R., Matar testified.

At that point, Matar said he knew Anwar R. by sight, but not by name.

In February 2011, Anwar R. was among the officers who accosted two of Matar’s friends, he said in court. They had planned to protest near Parliament in Damascus, he said. When some of the officers started beating up his friends, Matar said he walked up to Anwar R., who was standing by, and asked him to intervene. Instead, Anwar R. hit him, too, he said.

Not long after this alleged run-in, Matar said he spotted Anwar R. at the funeral of Syrian documentary filmmaker Omar Amiralay, a well-known critic of the Syrian government. Matar took a photograph of Anwar R., he said, saving it to his computer with the caption “the evil one.”

Matar testified that he was afraid and nervous about taking that shot. Simply attending the funeral was a risk, he explained, as filming security agents is not a trivial matter in Syria.

Once the protests began in March 2011, security officers including Anwar R. would show up at demonstrations. Matar suspected they wanted to memorize protesters’ faces, he told Human Rights Watch in 2020.

Matar said that at Branch 251 he was detained in an underground room with no natural light. He told Human Rights Watch that he had been “degraded, blindfolded and handcuffed and beaten by multiple people.”

He compared the experience to being “buried in a tomb” and said, “you’re being tortured without any logic.”

At first, interrogators beat him with a cable, he said in court. Later, they used a whip. He begged them to stop. At one point, he testified that interrogators ordered him to stand up, but he couldn’t.

All the while, he heard the screams of detainees in other interrogation rooms.

Matar was held in several cells at Branch 251, he told the court, some with 20 or 30 people.

There was no space. Sometimes people had to stand up so that others could sleep, Matar testified. Sometimes guards wouldn’t let them fall asleep, which Matar called mental torture. He could see people in other cells handcuffed to bars across the windows, he said, which prevented them from sitting down.

At one point he said he was blindfolded, and an interrogator asked him, “Whose photo is on your laptop?" Matar said he answered, “I don’t know.”

The man took off Matar’s blindfold, called him a “son of a bitch” and hit him in the face. It was Anwar R., Matar explained to the court.

According to Matar, Anwar R. put Matar’s blindfold back on. At that point, Matar said, he feared for his life.

But he survived. After 12 or 13 days in Branch 251, Matar was transferred to another prison, he said. A few days later, he and roughly 100 other detainees were taken to the prison’s courtyard, called traitors and criminals by officials, and then told they were released on an amnesty order from the president. They were transported to buses, Matar told the court, and he went to a friend’s apartment, never returning to his own home again.

He reached Germany in 2012.

Testifying at Anwar R.’s trial was “one of the hardest experiences that I have ever gone through,” he told Human Rights Watch. It forced him “to confront that past all over again.” He had migraines for weeks after testifying, he said.

But the act of testifying is something that Syrians like him who want “truth and reconciliation” simply “have to put ourselves through,” he said.

Background

The war in Syria has killed at least 350,000 people, forced over 12 million to abandon their homes, and left more than 12.3 million Syrians hungry. While parties on all sides to the conflict have committed serious crimes, Syrian government and pro-government forces account for the majority of atrocities committed against civilians.

There is the violence above ground: the bombing of hospitals, markets, and schools, as well as the deadly chemical weapons attacks against civilians, including children. But there is also the violence that is not readily visible: the hidden prisons and torture centers, into which tens of thousands of Syrians have disappeared – sometimes to re-emerge years later, sometimes never to be heard from again.

The court heard about torture and other violations committed in intelligence detention centers. Since the reign of Hafiz al-Assad began in 1971, the state’s intelligence agencies have helped lock in government rule, the judges heard during the trial. Intelligence officers monitored the population, conducting searches, arrests, and interrogations – including violent ones. They tracked the activities of religious groups, universities, and companies. Departments within the intelligence services were identified by their three-digit number.

Branch 251 was one of 27 detention facilities run by Syrian intelligence agencies that Human Rights Watch identified and located in 2011 and 2012, when Anwar R. was in Syria. (This report, as well as another by Human Rights Watch, was referred to in court). Because Branch 251 was located in the inner-city Damascus neighborhood of al-Khatib, people often informally called it the “al-Khatib branch.” According to witnesses in Koblenz, the Branch’s prison and interrogation rooms were located in the basement of a building.

b. The Accused

Anwar R. is accused of playing a role in this clandestine part of Assad’s machinery of war and repression. The court in Koblenz heard that he joined the Syrian secret service in 1993. From 2006 to 2008 he worked in intelligence before being transferred to Branch 251. Judges were told by witnesses that by January 2011, he was the head of interrogation at the detention center.

He fled Syria in 2012 following a massacre in his hometown of Houla, in Homs governorate, and after a grandchild was killed, the court heard. At the time, many countries across the Middle East and North Africa were engulfed in major political upheaval. Protests had toppled the government in Tunisia in early 2011. Soon after, Egypt’s decades-old government had fallen and Libya’s leader, Muammar Gaddafi, had been captured and killed.

He and his family first escaped to Jordan in December 2012, according to court testimony. He joined the opposition and in 2014 he participated in a peace conference in Geneva as an opposition representative, the court heard. That same year, on the recommendation of Syrian opposition leaders, the German Foreign Office granted him a visa.

At his trial, Anwar R. never took the stand. But on May 18, 2020, the fifth day of hearings, his lawyers read a prepared statement to the court. In it, Anwar R. listed nearly 20 people whose accounts prosecutors relied on in building their case. Then he attempted to negate their stories. Reem Ali, a Syrian artist, said Anwar R. had interrogated her, the statement read. Anwar claimed they had a friendly chat over coffee and that she was not interrogated. H. Mahmud said Anwar R. beat him; Anwar said it was not true. An anonymous witness claimed to have been incarcerated for 45 days and had seen a prisoner die every day. Anwar said he was merely in his office.

“I never had anything to do with torture,” Anwar R.’s lawyer read.

Patrick Kroker, a lawyer affiliated with the Berlin-based European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) and who represents a number of Syrians at Anwar R.’s trial, “was surprised” that Anwar R.’s statement was only a “flat denial” of the crimes he is accused of. Still, “It’s his right,” to make such a statement, he told Human Rights Watch.

Patrick Kroker — باتريك كروكر

Anwar R. isn’t the first former alleged government official on trial in Germany. He was tried together with a low-level employee from Branch 251, Eyad A., who on February 24, 2021, was sentenced to 4 years and 6 months for aiding and abetting crimes against humanity for his role in transporting protesters to Branch 251, despite knowing of the systemic torture there.

Eyad A.’s sharing of knowledge of the internal structure of Branch 251 and Anwar R.’s role there was a mitigating factor in his sentencing, since it was valuable evidence that contributed to the indictment of Anwar R., the judges said.

c. The Lawyer

The Syrian activist and lawyer Anwar al-Bunni had his own insider information about torture in Syria’s intelligence facilities, and he says he knew about Anwar R. long before the Koblenz trial, when he testified in court on June 4 and 5, 2020.

In 2006 in Damascus, al-Bunni was arrested. Men pulled him into a van, beating him. Although he never hit al-Bunni, Anwar R. was one of these men, he said in court.

Al-Bunni, born in 1959 to a political family in Hama governorate in Syria, took up the activism mantle early on, he told a Human Rights Watch researcher. His work defending political prisoners made him a target of the Assad government.

After this arrest in 2006, al-Bunni went to prison for five years, until May 2011. He was tortured while in detention, he told Human Rights Watch.

His family fled Syria and al-Bunni arrived in Germany not long after. Shortly thereafter, he and his wife were shopping near the Berlin Marienfelde refugee center where they lived, when al-Bunni spotted someone he thought looked very familiar but couldn’t place, he said.

It was only later, when a friend told him that Anwar R. was also staying in Marienfelde, that al-Bunni made the connection. It was Anwar R., he told Human Rights Watch.

Anwar al-Bunni — أنور البني

Al-Bunni had continued his activism in Germany. He, like other Syrians in Europe, including lawyer Mazen Darwish who testified in Koblenz, continued to strive for justice in Syria. They worked with the ECCHR, he said, collecting accounts of abuse from Syrians to share with German police and prosecutors who investigated serious crimes committed abroad. In 2017, ECCHR submitted a criminal complaint to German authorities on behalf of several Syrians against six high-level Syrian officials, including Ali Mamluk, who, as the head of the National Security Bureau and a personal advisor to al-Assad, allegedly oversaw the country’s intelligence detention facilities.

When asked about seeing Anwar R. in Berlin, al-Bunni said: “This is not a personal issue. It is not about if this person detained me or not, hit me or not. It is about the regime and what it does.”

The Struggle for Justice

What the Syrian government has done is destroy entire neighborhoods, with barrel bombs, and use prohibited chemical weapons against thousands of civilians. In order to regain control of territory, the Syrian government created alliances with Russian and Iranian forces, all of which used horrific and unlawful tactics to take ground. Both Syrian and Russian forces have been accused of serious crimes, as have other parties to the conflict like the Islamic State (ISIS) and al-Qaeda affiliates.

More than 6 million Syrians have been forced to flee the country because of the war. Most live in Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon. Another 6.7 million Syrians are internally displaced – together, more than half of Syria’s total 2010 population. Today, more than 80 percent of the population lives below the poverty line.

There is no sign that the Syrian government will stop the violence or reform, especially with the Assad government increasingly regaining diplomatic recognition. Multiple countries, such as the United Arab Emirates, have thawed their relationship with Assad, while Jordan has re-established contact at the highest level and re-opened its borders with Syria.

Holding a trial like Anwar R.’s in today’s Syria is inconceivable. Other paths to justice have also been blocked. The International Criminal Court in the Hague does not have an automatic mandate, as Syria isn’t a member of the court. The UN Security Council, the body in charge of maintaining peace and security, could give the court jurisdiction, but China and Russia vetoed this action in 2014.

This leaves national trials in foreign countries as the only means for criminal justice at this time.

The case against Anwar R. has been brought in Germany because the country recognizes “universal jurisdiction.” This grants German authorities the power to investigate and prosecute some of the most serious crimes, such as war crimes and crimes against humanity, no matter where they were committed and regardless of the nationality of the suspects and the victims.

Alexander Suttor — ألكسندر ساتور

Germany is one of several countries in the world, like Sweden, the Netherlands, and France, that has laws of this kind.

Germany, of course, has its own history with serious crimes. The Nuremberg trials were a “breakthrough for the modern notion of international criminal law,” said Claus Kress, an international and criminal law professor at the University of Cologne, referring to the 1945-1946 trials that held Germans accountable for crimes committed during World War II.

Claus Kress — كلاوس كريس

The Making of a Trial

The Koblenz courthouse sits on a street near where the Rhine and Mosel Rivers meet, not far from a 19th century Prussian fortress and an easy walk to the medieval old town area. It is the highest court in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. Koblenz is a quieter city, and it feels jarring to “step out into this idyllic scenery after hearing brutal testimony in the courtroom,” said Alexander Suttor, a lawyer at Clifford Chance, a law firm that observed the trial for Human Rights Watch.

Anwar R.’s trial has been built on evidence painstakingly gathered and corroborated, on the fine sifting of facts from leads.

Along with interviewing witnesses, police investigators also needed to establish the context of Anwar R.’s alleged crimes. What was happening in Syria in 2011 and 2012?

Swathes of people have documented Syria’s war: human rights researchers, journalists, UN investigators, police investigators, as well as Syrian nongovernmental organizations like Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Speech, the Syria Legal Center, and the Caesar Files Group.

Since its creation by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011, the UN Commission of Inquiry has compiled troves of material – survivor interviews, forensic reports, videos, and satellite imagery – of war crimes and crimes against humanity in Syria. Two of these reports, one from 2011 and 2012, were read in court in Koblenz.

“You’re trying to do your best to amplify the voices of victims,” said James Rodehaver, a former coordinator with the UN’s Syria Commission of Inquiry, who now works on Myanmar. He and his team documented human rights violations and breaches of the laws of war by interviewing countless witnesses and corroborating their stories. When possible, they also identified the parties responsible for the crimes they documented.

The UN, along with many other groups documenting crimes in Syria, was also using technology in innovative ways. For example, Human Rights Watch, which authored two reports referred to in court, has relied on open-source material and satellite imagery to document what we learned about intelligence prisons, as well as crimes committed in Syria that are not being tried in Koblenz, such as chemical weapons attacks and massacres. We Skyped people who witnessed massacres and used Google Earth – which shows aerial and on-the-ground images of cities – to walk witnesses through what happened.

“I would ask them to show me on the map” where they saw security forces or dead bodies, said Diana Semaan, former Human Rights Watch research assistant, now Syria researcher for Amnesty International. Then the Human Rights Watch team would geolocate the location and have satellite imagery taken of the spot.

Diana Semaan — ديانا سمعان

But how did this evidence help bring a man, who ended up in Germany, to trial for crimes against humanity in Syria?

a. The Police Investigators

It helps when the accused perpetrator brings himself to the attention of German police.

On August 30, 2017, Martin Holsky, a chief inspector of the Baden-Württemberg state police, was interviewing Anwar R. in order to gather evidence against another Syrian suspected of firing on civilians during a demonstration in Hama, Holsky testified in court. Anwar R. told him that in the early days of the uprising, the Syrian Republican Guard had arrested 17,500 people and cycled them through Anwar R.’s department, Holsky said. They were questioned and the majority were released while others were locked up and tortured, Anwar R. had told him.

Holsky testified that when he asked more specifically about torture, Anwar R. replied: “With this many interrogations in one day, you can’t always be polite. With armed groups, you sometimes need to be stricter.”

Anwar R. also told Holsky about the time that more than 700 people, including corpses, were brought to Branch 251. Anwar R. then told Holsky that, as the man in charge of investigations, he had nothing to do with dead bodies.

The information was bumped up to Manuel Deusing of the German federal police, who then opened an investigation into Anwar R.

Deusing contacted the Berlin state police, he testified in court, who told him what they learned about Anwar R. when he suspected Syrian intelligence officers were tailing him in 2015. Deusing also asked the Center for International Justice and Accountability to share with him any documents smuggled out of Syria related to Anwar R. The group sent Deusing notes on prisoner interrogations that Anwar R. had allegedly submitted to the head of his department, Deusing said. The documents also identified Anwar R. as a member of the “Central Interrogation Committee.”

Coordination with other European authorities helped drive the investigation, Deusing said in court. German law enforcement established a joint investigation with French authorities, sharing information and interviewing witnesses in France. Swedish and Norwegian authorities facilitated interviews with witnesses living there.

In all, the German federal police interviewed more than 70 people while investigating Anwar R., Deusing said.

Deusing then tapped Anwar R.’s phone and had his home searched, he said. Police officers confiscated smartphones, a laptop, and CDs. They found a notebook with a small address book containing contact information for high-ranking Syrian officials and copies of his badge from the General Intelligence Directorate.

On February 12, 2019, Anwar R. was arrested together with Eyad A.

b. The School Headmaster

The arrest was more than the result of inspired sleuthing by the German police, it was the culmination of nearly 10 years of painstaking documentation of crimes in Syria. Many involved in this work did so by speaking with thousands of Syrians who told the stories of what happened to them, their friends, and their relatives in villages in cities across the country.

Deusing described in court how his team of investigators had used reports by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch that documented the deaths and disease caused by prison conditions in Syria: the overcrowding, the terrible sanitation, the lack of food and medicine – and the torture.

These reports are comprised of firsthand observation, accounting, and analysis by researchers on the ground – and the work of local Syrians, who understand the area’s political and geographic landscape, and who decided to help researchers and journalists identify survivors to interview in the hope of exposing violations that could lead to change. Without these Syrians, the work of organizations like Human Rights Watch and that of many foreign correspondents would not be possible.

Mahmoud Mosa, a refugee who fled his home in the Syrian state of Idlib for Turkey in 2011, assisted numerous news outlets as well as Human Rights Watch researchers. A former headmaster and English teacher, Mosa helped sneak people safely across the ever-changing crossing points of the Syrian-Turkish border, often relying on agents, some of whom were his former students. For Mosa, it was imperative that the world knew what was happening in Syria, the villages destroyed, the people killed.

Mahmoud Mosa — محمود موسى

He also helped get journalists into Kurdish areas of Syria and even into the city of Aleppo after it was occupied by the Islamic State (ISIS).

In 2011, two Human Rights Watch researchers worked with Mosa in refugee camps in Turkey. They interviewed Syrians who had been held in Assad’s detention centers, including Branch 251, and who had overheard and memorized the names of officers or other people working in the prisons. These interviews fed into Human Rights Watch’s 2012 report documenting Syria’s military prisons, the torture methods used there, and even who ran them.

The report was read in the Koblenz court. It shows what tremendous effort by one man, Mosa, can achieve – even almost ten years after the report was published – and the power of Syrians who are able to tell their stories.

c. The Photographer and His Friend

And then the court considered the “Caesar” photos.

Before the uprising, Caesar (a codename) worked as a photographer for the military police in Damascus and later defected. Not long after the demonstrations started in 2011, he and his team were assigned to photograph the dead bodies of protesters who had been shot by government forces in Daraa, a key city in the anti-Assad uprising, according to Garance Le Caisne, a French journalist who was among the first and few to interview Caesar directly. Over the following months, they were told to photograph bodies of people who had died in detention, Le Caisne told Human Rights Watch.

Caesar wanted to desert, Le Caisne said, but his best friend Sami, who opposed Assad’s government, convinced him to stay put in order to duplicate the photos and document the abuses. Between May 2011 and August 2013, Caesar is thought to have copied some 53,000 shots of corpses. Sami saved them on a hard drive at home. The photos were then smuggled out of Syria.

Garance Le Caisne — غارنس لو كاين

Some of Caesar’s photos, which became public in 2014, were admitted as evidence in the trials of Anwar R. and Eyad A. (In 2015, Human Rights Watch identified 27 of the victims in the photographs, verifying their authenticity). Dr. Markus Rothschild, a forensic expert from the University of Cologne, examined the photos and showed them to the courtroom while explaining his findings.

Rothschild testified that his team had analyzed nearly 27,000 shots of 6,821 people. He estimated that 110 of those people had been detained at Branch 251, based partly on a number that had been written on their foreheads.

Of the 110 dead from Branch 251, he said that many had gone hungry and 7.3 percent had probably starved to death. Fifty-five showed injuries, predominantly from blunt force, from hitting, pushing, or kicking.

Rothschild testified on November 3, 2020. His use of photos in explaining how the detainees presumably died deeply affected people in the courtroom.

The photos’ power even persuaded one of the accused to speak out. On December 9, Eyad A.’s lawyer read a prepared statement by Eyad A. – the only time he addressed the courtroom. “My feelings on the images are this: They broke my heart,” his lawyer read. “During the drive back to the prison, I cried.”

When the presiding judge handed down the sentence against Eyad A. in February, she said about the Caesar photos: “A personal note on this: I will not forget those images.”

“People talk about the Caesar files and people talk about Caesar,” Le Caisne said. “But I’d like to say that there are hundreds of Caesars in Syria, really” – people who stand up to the Syrian government and do whatever possible to document and denounce its crimes.

What the Trial Means to Syrians

Like millions of other Syrians, today Caesar is a refugee living outside of his homeland.

But in recent years, the conversation around Syrian refugees has shifted dangerously. The pressure is building in countries like Denmark, Lebanon, and Turkey, which had previously opened their doors to refugees (however hesitantly), to force them back home to Syria despite the danger.

To these countries, the Syrian conflict is “over.” But the reality is that the underlying causes of the conflict – the repression, the arbitrary abuse, the constant fear for one’s life – is still real. Human Rights Watch and others have documented how refugees from Lebanon and Jordan who returned to Syria have faced enforced disappearances, torture, and even sexual violence at the hands of the Syrian government and affiliated militias.

Last December, Germany’s interior ministry discussed whether it was safe to send Syrians convicted of crimes in Germany back to Syria, despite the dangers they risk on return. These discussions sparked concern among Syrians that German authorities may be seeking to normalize relations with the Syrian government.

For refugees, it’s already “difficult to build an existence,” let alone doing so while knowing the discrepancy between how German politicians “trying to win” elections describe Syria versus the reality there, said Bente Scheller, the head of the Middle East and North Africa division for the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

Bente Scheller — بنت شيلر

Eyad A.’s trial was also tricky for some people. Media reports following Eyad A.’s verdict show that his conviction and sentencing divided Syrians, even though German authorities are under an obligation to prosecute individuals suspected of committing serious crimes. Some Syrians wanted Eyad A. in prison much longer. Others wondered why German authorities even bothered bringing a case against Eyad A. – he was so low-level, and how many people had done as much or worse?

As with Anwar R., a question with Eyad A. for some Syrians was, can you change sides? And if you are guilty of crimes, does changing sides absolve you of this guilt? Some Syrians worried that in prosecuting defectors, other Syrian officials would be afraid of prosecution, meaning they won’t share their inside information of the violations committed. And together with witness testimony, this inside information is what helps build trials.

Syrian refugees are facing another challenge when it comes to the Koblenz trial: There is no Arabic interpretation available. True, Anwar R. and Syrian witnesses all have translators, but that doesn’t help the Syrians sitting in the courtroom’s public gallery. Additionally, the court’s press releases are not translated into Arabic.

“It was really frustrating,” said Ameenah Sawwan, an activist with the Syria Campaign, who despite speaking decent German could not understand the legal courtroom language. However, when Eyad A.’s verdict was read in both German and Arabic – an exception to the rule – it “made a huge difference,” she told Human Rights Watch.

Ameenah Sawwan — أمينة صوان

Until August 2020, proceedings were only translated into Arabic for formal parties to the case. Though the German Constitutional Court in response to a petition issued a temporary order extending translation to pre-accredited Arabic-language journalists, the trial remains inaccessible to non-German speakers in the public gallery. The written verdicts will also only be available in German, and no transcript in any language will emerge once the historic trial concludes.

Alex Dünkelsbühler — أليكس دوينكلسبولير

Still, a number of Syrians have attended the trial, and it is impossible to count how many more followed it. But what does the trial mean to them?

a. The “Disappeared”

When Wafa Mustafa heard about the trial, she realized it could be an opportunity to draw attention to enforced disappearances in Syria.

Mustafa, 30, misses her father. On a sunny July day during Anwar R.’s trial, she sat cross-legged on the sidewalk outside the Koblenz courthouse, holding up a portrait of her father, Ali, who was disappeared in 2013. Mustafa has a presence, drawing people to the scores of framed photos of Syrian loved ones of people she knows or works with. These people have gone missing and have been presumed forcibly disappeared by Syrian forces, if not taken by ISIS or other groups.

Wafa Mustafa — وفاء مصطفى

That July day, Syrians who visited her memorial walked away in tears, according to Alexander Dünkelsbühler from Clifford Chance, observing the proceedings.

An untold number of people have been forcibly disappeared in Syria, most of them into detention centers. Some of the people re-emerge and are reunited with their families. Others do not.

Mustafa’s father took her to her first protest when she was 9 or 10 years old, she told Human Rights Watch. When the protests started in 2011 in Damascus, she went. “It wasn’t a question,” she said.

Shortly after her father was arrested in her hometown, Wafa and her sister were also detained by Syrian officers, but in Damascus, she said. They were quickly released, and shortly afterwards they fled the country. Mustafa separated from her family and came to Germany in 2016.

Mustafa’s father has been missing for a little over 8 years. Every morning, she shares on Twitter the number of days he has been gone. “I’m not sure how healthy that sounds, but everything I do in my life is centered around my dad,” she said.

She is using the media attention created by the trial to remind the world that people are still being forcibly disappeared in Syria, and that a decade on, the international community cannot continue to hear about atrocities in Syria and fail to act. It has a role to play in stopping abuses – including by releasing detainees.

“There are still people who we can save” from death by torture or from contracting Covid-19 in prison, she said. Including, she hopes, her father.

Samaa Mahmoud is also mourning a disappeared relative, her uncle, Hayan. Her father, Hassan Mahmoud, is a represented victim in Anwar R.’s trial and has accused Anwar R. in court of torturing his brother, Hayan, who was forcibly disappeared in 2012. In his testimony, Hassan Mahmoud said he heard secondhand that Hayan was taken to Branch 251 and that he died there.

Samaa Mahmoud — سماء محمود

Samaa Mahmoud fled Syria as a child and arrived in Germany in 2015 where she is now studying social work at a German university. She is proud of her father for fighting for Hayan and for speaking of his own two arrests (he was not detained in Branch 251), she told Human Rights Watch. She reads all the articles on the trial, but she hasn’t gone in person. “I can’t, mentally that is,” she said.

The fact that former detainees are able to face Anwar R. in court, she says, “is truly something worth being optimistic about.” She thinks the trial “is going to change our lives, even if only a little bit, but for the better.”

“The road to Damascus has to be built”

After more than a year-and-a-half of hearings, including testimony from over 60 witnesses, Anwar R.’s trial is set to conclude in January.

Neither the bleakness of the testimony – including firsthand accounts of torture or mass graves – nor the out-of-the-way location of Koblenz stopped some Syrians from coming to the court.

Khaled Rawwas attended 11 sessions of the trial by July 2020. A mechanical engineer, he says he was arrested twice in Syria for protesting (he was never taken to Branch 251), and he fled the country in 2013. He has been in Germany for five years and now works in the shipbuilding industry.

“Once upon a time, I was being held and I was being interrogated in a way that does not resemble the way Anwar R. was being interrogated,” Rawwas told a Human Rights Watch researcher. “To be honest, I had a kind of envy,” watching how Anwar R. was treated in the Koblenz court, how his rights were protected, he said.

Khaled Rawwas — خالد رواس

Rawwas described to us his own time in a courthouse, in Syria: “It was for two minutes. The judge asked me one question.”

For him, a high point of the trial was the German prosecutor’s opening statement, which called the 2011 protests and the ensuing conflict in Syria “a revolution.”

“For me this is something very huge,” Rawwas said. To him, what happened in Syria wasn’t a civil war, it was “a revolution against a corrupt system.”

Rawwas told us that the trial’s being held in Germany rather than Syria was “a sort of heartbreak.”

“But,” he added, “at least it did start something.” For victims of violence or repression, like him, and for others, too.

Mokhtar (not his real name), a Syrian, runs a small restaurant in Germany. It has wooden tables and chairs, and pictures of Syria on the walls. Tomatoes and cucumbers sit behind the counter; falafel fry away, with a loud spitting sound. The menu includes makali sandwich wraps, but also pizza and fries.

Mokhtar is not involved in the Anwar R. trial, nor was he detained in Syria, he told Human Rights Watch. He left after witnessing a massacre, he said. It took two years, but the German government eventually recognized his asylum claim.

James Rodehaver — جيمس رودهفر

At first, the idea to open a restaurant was a “joke” with his friends, he said. After all, he had only €1,000. But he borrowed money from friends, and soon he opened the place. “A year and a half later, I had paid back everyone in full,” he said. Today, he sends 20 percent of his earnings to people in need in Idlib and Damascus.

The UN’s James Rodehaver argues that “the road to Damascus has to be built.” And that road might run through Koblenz. The trial of Anwar R. is, Rodehaver says, “the first paving stone” for rebuilding justice in Syria.

Mokhtar — مختار

When thinking about his hometown of Damascus, Mokhtar, the restaurant owner, says, “I am proud of our revolution, and I am proud of my people that miraculously stood up to a dictator.”

Additionally, the trial sends a message to other officials and agents of the Syrian government. “Even if they go to the end of the world, someone will get them,” he said. “I am very happy about that.”

Human Rights Watch would like to express appreciation to all those who agreed to be interviewed for this piece, and in particular all the Syrians who shared with us their experiences. Human Rights Watch would also like to extend their gratitude to the international law firm Clifford Chance – and in particular the firm’s Frankfurt office who observed the trial in Koblenz for nearly two years. Invaluable assistance was provided by Caroline Kittelmann, Alexander Suttor, and Alexander Dünkelsbühler. Human Rights Watch’s work on universal jurisdiction in Germany is financially supported by the Deutsche Postcode Lotterie, Clifford Chance and Hamburger Stiftung zur Förderung von Wissenschaft und Kultur.

This piece is the result of a collaboration among Human Rights Watch’s International Justice, Middle East and North Africa, and Media teams.